- 1Faculty of Education, Kuwait University, Kuwait City, Kuwait

- 2Laboratory of Applied Psychology, Languages and Philosophy, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Fès-Saïss, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco

Introduction: Universities have long been regarded as the cornerstone of social transformation. This study explores the role of universities in promoting citizenship values and fostering political participation among university students. Specifically, it examines how national loyalty influences Kuwait university students’ political participation at Kuwait University, with an emphasis on the mediating role of university in promoting citizenship values.

Methods: Using a quantitative approach, data were collected from 1,720 students from different programs.

Results: The results revealed that national loyalty has a direct and positive effect on students’ political participation, with a partial mediation effect of universities.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the importance of both nurturing national loyalty and strengthening universities’ roles in civic education to encourage broader community engagement.

Introduction

At its core, Citizenship represents the relationship between individuals and their homeland, which includes values, responsibilities, and rights. It is a manifestation of identity, commitment, and involvement in societal progress (Yasein Salman and Mohammad Harafsheh, 2020). The idea of citizenship is conceptualized as one of the intrinsic ties between members of a society. In a world of globalization and socio-political tensions, national cohesion and resilience depend heavily on the maintenance of a deep sense of citizenship and any lack of that structure necessarily carries extreme risk (Abreu and Velázquez, 2019).

One of the key dimensions of citizenship is participation in civil society, community, and political life. The term active citizenship has become very commonly used when describing forms of participation that are supposed to be fostered so as to ensure a strengthening of democratic values, social cohesion, and a sense of responsibility toward the common good (Hoskins and Mascherini, 2009). It is the political participation that involves individuals in the exercise of their rights and duties. Therefore, the essence of citizenship and its social foundation is involvement in democratic life to defend rights, accountability, secure freedoms, and resist injustice.

These participatory activities, including political participation, form the base of every democratic society and constitute one of the principal means whereby citizens become involved in decision-making. Active participation in politics is important, not only for democracy to function, but also in order for policies to be responsive to the will and interests of the population (Hamilton and Fauri, 2001; Verba and Brady, 1996).

In this regard, it has been found that national loyalty plays a significant role in fostering active citizenship. National loyalty has been defined as an attitude that pre-disposes individuals to respond to their country with actions perceived as supportive of, and/or with feelings that value the continued existence and welfare of the nation. This sense of loyalty manifests in both tangible actions and emotional investments that reinforce a commitment to the nation’s values, stability, and long-term prosperity (Terhune, 1965).

In this perspective, it is important to distinguish national loyalty from loyalty to a particular government or regime. True national loyalty transcends allegiance to any transient administration. In fact, loyalty to the nation can be expressed through critical engagement with the government, holding it accountable and advocating for reform when necessary, an essential element of a healthy democracy. Criticism, therefore, should be seen not as disloyalty but as a form of active citizenship that seeks to uphold and improve the nation’s democratic principles and future stability (Poulsen, 2020).

Precisely, loyal citizens take part in political and social life more effectively, thereby contributing to the growth and stabilization of their country. National loyalty is said to increase the sense of responsibility and participation urge in citizens in national affairs. For university students, whose formative years are often marked by exposure to diverse ideas and political discourse, national loyalty can be an important determinant of how deeply they engage in political processes. Loyal citizens are more likely to participate in voting, advocacy, and other forms of political action, contributing to the stability and advancement of their nation. Loyalty transforms into active participation because people feel a personal responsibility or attachment to improving the wellbeing of their community or nation (Abu El-Haj and Bonet, 2011).

Loyalty, therefore, should not be seen as an innate or natural trait; it is shaped by social influences that build pride and a sense of belonging to our country (Alduwaila, 2017). These influences come through government-run places like schools and the military, where nationalistic ideas are taught. These places are crucial in teaching us about nationalism by integrating patriotic stories into school lessons and employing national symbols and rituals. These elements have a strong impact on how we perceive ourselves as members of a nation. These processes may be explicit (e.g., in education) or more implicit (e.g., through everyday symbols or practices), making nationalism a pervasive and integrated part of daily life (Al-Fadhli and Al-Saleh, 2012; Aldhafiri and Alsaeed, 2024; Leonard and Spyrou, 2011; Scourfield et al., 2006).

Identity is a broad and foundational concept that refers to an individual’s understanding of who they are, often shaped by social, cultural, and group affiliations. Loyalty, in contrast, can be viewed as one potential expression or outcome of identity. When individuals strongly identify with a group or institution, they are more likely to exhibit loyal behaviors, such as sustained commitment, advocacy, or resilience in the face of challenges. As Fletcher (2011) argue, “the basis of loyalty is the historical self,” suggesting that loyalty emerges from a continuity of identity over time, grounded in one’s past experiences and enduring affiliations. Thus, while identity encompasses the internal, cognitive structure of the self, loyalty reflects a behavioral manifestation of that identity in relational and institutional contexts (Connor, 2007; Fletcher, 2011; Marantz, 1993).

In today’s world, every country seeks loyalty from its citizens, viewing the stability, strength, and sustainability of its systems as dependent on their national loyalty. To achieve this, countries implement extensive programs designed to cultivate loyalty to their systems and values. Beyond the family, the education system serves as the second most influential institution in shaping the future of a nation. It plays a pivotal role in fostering a sense of national loyalty among students and strengthening their connection to their country (Fateminia and Rezanezhad, 2023).

Education is important for creating loyalty and citizenship, both in and out of the classroom (Astin and Antonio, 2004; El-Kassar et al., 2019; Leroux, 2019). As Bénéï (2005) emphasizes, loyalty can be nurtured through all sorts of processes in all kinds of contexts, including formal institutions such as schools or universities (Bénéï, 2005). Research supports the link between this type of loyalty or belonging and increased civic engagement and societal contribution (Putnam, 2000). Such connections demonstrate the need for fostering loyalty in educational and societal contexts; people are less likely to see the value in contributing meaningfully to collective goals and democratic processes if they are not tied to an organization or a cause (Morrow and Scorgie-Porter, 2017).

Indeed, Formal education is one of the most consistent and strong predictors of political participation (Nie et al., 1996). The association between education and political participation is among the best documented and most cited in all of political science. If researchers could select one variable to predict behaviors like voting, contacting elected officials, signing petitions, or discussing public issues, the variable would be educational attainment (Willeck and Mendelberg, 2022).

The University as a mediator between loyalty and participation

Education, in all its forms, is the best tool to help individuals understand the modern state in all its dimensions and promote the values of citizenship taking regard of the new historical, social and political realities (Cogan and Derricott, 2014; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022). Sociological and educational theories have extensively discussed the importance of education in developing citizenship. Cogan and Derricott (2014) points out that the curriculum in our schools and universities can be a relevant vehicle for communicating civil values such as respect for the rule of law, participation in democratic practices, knowledge of social rights and duties. Education is more than dispensing knowledge as it seeks to instill moral and civic character of individuals (Isac et al., 2014; Lawton et al., 2004). Dewey (1916) argued that education should empower individuals to critically reflect on their society and its values and would enable individuals to contribute to the public good (Dewey, 1916).

University can help individuals see the importance of the collective identity and national goals through social cohesion and sharing values (Aoun, 2010). As Banks (2004) argues, citizenship education encompasses far more than legal rights and duties; it also involves cultivating empathy, cultural understanding, and respect for diversity. When these values are embedded within the curriculum, they provide a foundation for constructing a national identity that transcends narrower group affiliations—whether ethnic, racial, or religious (Banks and Banks, 2020; Tonyeme, 2021).

There is a broad discussion in literature regarding the association between education and political participation. Both policymakers and educators, as well as researchers, have acknowledged the importance of higher education organizations in encouraging civic engagement in students (Beaumont et al., 2006; Galston, 2001; Pritzker et al., 2012).

There are three theoretical perspectives through which one can understand the effect of education on political engagement. According to mediation theories, education has an indirect effect on political participation, but builds the skills and knowledge as well as attitudes (critical thinking and civic) that mediate participation (Nie et al., 1996). Theories of preadult socialization emphasize that civic norms and democratic growth are promoted through education over the long run, the notion that the actual learning of collective values, actions and behaviors occurs during the formative years of children through experiences, character and culture, significantly shaping civic values, attitudes and behavior of individuals over the long-term (Gutmann, 1999; Highton and Wolfinger, 2001). Finally, proxy theories suggest that education is not an independent determinant of political participation, but rather one factor in the broad set of factors that define socioeconomic status. From this view, income, wealth, and occupational prestige are the real determinants of political participation, while education is just a correlate of those determinants. Collectively, these perspectives provide different lenses through which the complex linkage between education and political engagement may be viewed (Jennings et al., 2009; Nie et al., 1996; Willeck and Mendelberg, 2022).

More specifically, they can assume a crucial mediating role between loyalty and participation by affording students not merely a sense of belonging, but also by instilling citizenship, democracy, rights and duties. Universities can create opportunities for students to engage with their local environment, cultural traditions, and the surrounding community through place-integrated learning, reinforcing opportunities for identity and belonging (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022).

The more emotionally and cognitively students experience their environment, the more loyal they become and the more they engage in civic and societal life. This approach mobilizes their fidelity into action, be it voting, community organizing, advocacy, etc., and allows them to increase their engagement with the world around them. In this sense, the role of the university to act as a mediator is crucial in transferring students from the belonging and commitment stage to actively engaging with civic affairs, thus promoting not only loyalty and commitment, but also democratic involvement and voice (Feezell, 2013; Levinson, 2012). This involvement extends beyond the political aspects of citizenship, encompassing social aspects as well. This involves fostering attributes like a “willingness to volunteer” and a “belief in the agency to change the social environment (Aoun, 2010; Geboers et al., 2013).

This role of universities is most relevant given the age of university students, as this is a critical period when their identities mature and they become more actively engaged in societal matters compared to younger individuals. At this stage students are ready to learn about democratic principles, civic obligations and the responsibilities of an active citizen. These principles require a favorable environment which can be rightfully provided by the congenial and serene university atmosphere where students can think critically and debate on the essence of democracy, rights and duties. Their involvement in university and community initiatives not only defines their identity but also establishes them as informed and engaged citizens. Nevertheless, in certain scenarios, a reverse relation has been identified to exist where education has weaken the connection between national loyalty and participation (Kim and Lee, 2021). Here to say—loyalty to the nation and involvement in social and political life are related in ways that differ according to nations’ unique political and historical context.

Despite growing interest in citizenship education and youth political engagement, there remains a significant gap in the literature concerning the intersection of national loyalty, the university’s role in promoting citizenship values, and the political and social participation of university students. While each of these dimensions has been explored to some extent independently, few studies have examined how they interact within the context of higher education. This gap is particularly evident in the context of Kuwait, where universities play a central role in nation-building and civic development, yet empirical research addressing how they influence students’ loyalty and engagement remains limited (Alduwaila, 2017; Alzaboun and Al-Rayes, 2023). This underpins the urgent necessity for additional research to investigate the links between these three variables with special emphasis on the higher education context in Kuwait.

In line with these perspectives, the current study aims to explore the role of Kuwait University in consolidating citizenship values. The paper will evaluate the level of students’ national loyalty and their involvement in political and social activities, both within the university and in the broader community. Furthermore, the study will investigate how university mediates between students’ national loyalty and their engagement in political life.

Materials and methods

Study design

Through a cross-sectional design, This study examines the role of the university in reinforcing citizenship values among students, measures their sense of national loyalty, and assesses their level of national participation. The research was conducted across different faculties at Kuwait University during the first and second semesters of the 2023/2024 academic year.

Study sample

The total population of students at Kuwait University is 30,692 students, enrolled across 15 faculties, including 6 humanities faculties and 9 faculties for applied and scientific disciplines. For this study, a multi-centric probabilistic sampling method was employed. In the first phase, a sample was drawn from 9 out of the 15 core faculties, ensuring a balanced representation of both the humanities and applied sciences. The selected faculties included Education, Arts, Sharia, Science, Engineering, Social Sciences, Medicine, Pharmacy, and Management.

From the nine selected faculties, which together comprised a total student population of 26,126, a stratified random sampling technique was applied. Proportional representation was ensured based on the number of students in each faculty. The final sample included 512 students for the pilot study and 1,720 students for the main study, representing approximately 6.58% of the total population.

The stratification considered key variables such as gender, faculty type (humanities or applied sciences), and academic year, ensuring the sample reflected the demographic and academic distributions within the university.

Data collection

Previous studies on citizenship and belonging provided the methodological foundation for developing the study tool, which is designed to assess the citizenship of university students. The scale specifically measures three key dimensions: The university’s role in reinforcing citizenship values, students’ participation in political and social activities, and their loyalty to the nation (Carpendale et al., 2019; Dam et al., 2020; Granhenat and Abdullah, 2017; Hamilton and Fauri, 2001; Heydarpour et al., 2022; Hoskins and Mascherini, 2009; Kalaycioglu and Turan, 1981; Kenski and Stroud, 2006).

Each domain is represented by a set of items reflecting the targeted construct. For example, the item “University courses introduce us to the values of rights, freedom, and justice” reflects the educational role of the university in promoting civic values. The item “I take pride in being a citizen and feel satisfied with my national identity” captures the emotional and symbolic dimension of national loyalty. Finally, the item “I participate in parliamentary elections” represents engagement in formal political participation.

To assess the apparent validity of the instrument, the researcher presented it to a panel of faculty members from kwaitian universities. The panel was asked to provide feedback on the relevance of the items to the study domains, their clarity, and the accuracy of the language. Based on the feedback, the researcher selected items that received approval from at least half of the arbitrators, incorporating their comments regarding phrasing, clarity, domain relevance, and proposed changes. As a result, the final version of the instrument included 23 items, distributed across three main sections:

Section 1: University role in reinforcing citizenship, consisting of 10 items.

Section 2: Student perceived national loyalty, consisting of 6 items.

Section 3: Students political participation, consisting of 7 items.

A five-point Likert scale was used to measure the degree of agreement among the study participants regarding their practices for each statement. The response levels were rated as (Very High, High, Medium, Low, Very Low), represented numerically in the order (1-2-3-4-5).

The final version of the questionnaire included questions related to independent variables such as gender, specialization, academic year, college, and geographical provenance.

Pre-testing the instrument

The instrument underwent validation by several faculty members from the College of Education, who provided feedback on its ability to measure the intended objectives, clarity of items, and their alignment with the respective axis. Adjustments were made based on their scientific observations. The instrument was also tested on a sample of 140 students from the College of Education to evaluate its comprehensibility and the time required for completion. Modifications were made accordingly to improve its linguistic and conceptual structure.

Statistical procedures

The study utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and r (RStudio, 2011 ) to analyze data related to the fieldwork aspect, employing various statistical measures to address the research questions.

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and percentages, were calculated to summarize and describe data trends. Cronbach’s alpha measured the reliability of the instrument. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to uncover the underlying structure of the data and identify key factors influencing the variables under investigation.

Following the exploratory phase, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to validate the proposed measurement model and assess its fit to the observed data. Several goodness-of-fit indices were utilized for this purpose, including the chi-squared test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). A good model fit was determined by a CFI value near or above 0.95, SRMR below 0.08, and RMSEA below 0.06, with RMSEA values between 0.06 and 0.08 considered acceptable (Browne and Cudeck, 1992). Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS. Model 4, which tests simple mediation, was selected for this analysis.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were rigorously observed in this study. Approval was obtained from the ethical board, along with administrative permission from the university, prior to initiating the research. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives, and their informed consent was secured. Measures were taken to ensure the anonymity of participants and to maintain the confidentiality of all collected data, adhering to the highest ethical standards throughout the research process.

Results

Instrument validation

Exploratory factor analysis

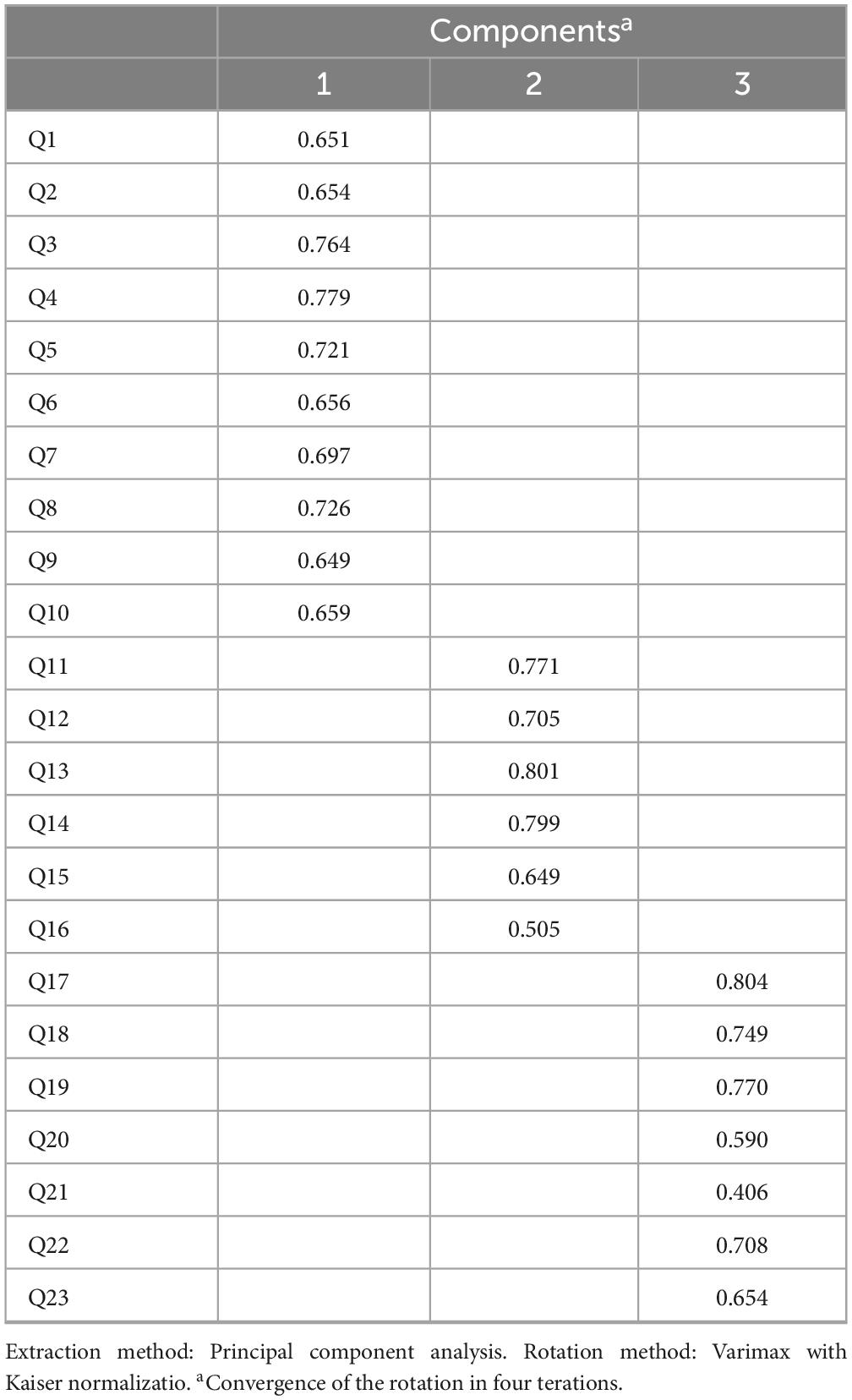

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization. The analysis aimed to identify the underlying structure of the questionnaire items.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.880, which exceeds the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating that the sample was adequate for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant [χ2(253) = 11,850.142, p < 0.001], confirming that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix and suitable for factor analysis.

The total variance explained by the identified factors was 50.288%, which meets the acceptable threshold for social sciences research. Three components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained, as indicated by the explained variance:

1. Component 1: Initial eigenvalue = 5.597, explained 24.334% of the variance.

2. Component 2: Initial eigenvalue = 3.001, explained 13.047% of the variance.

3. Component 3: Initial eigenvalue = 2.968, explained 12.906% of the variance.

After Varimax rotation, the components accounted for 21.593, 15.207, and 13.488% of the variance, respectively, for a cumulative variance explained of 50.288%.

The rotated component matrix revealed clear factor loadings for the items. Items Q1–Q10 loaded highly on Component 1, items Q11–Q16 loaded on Component 2, and items Q17–Q23 loaded on Component 3. This suggests that the questionnaire reliably measures three distinct constructs. The loading values ranged from 0.406 to 0.804, further supporting the validity of the factors (Table 1).

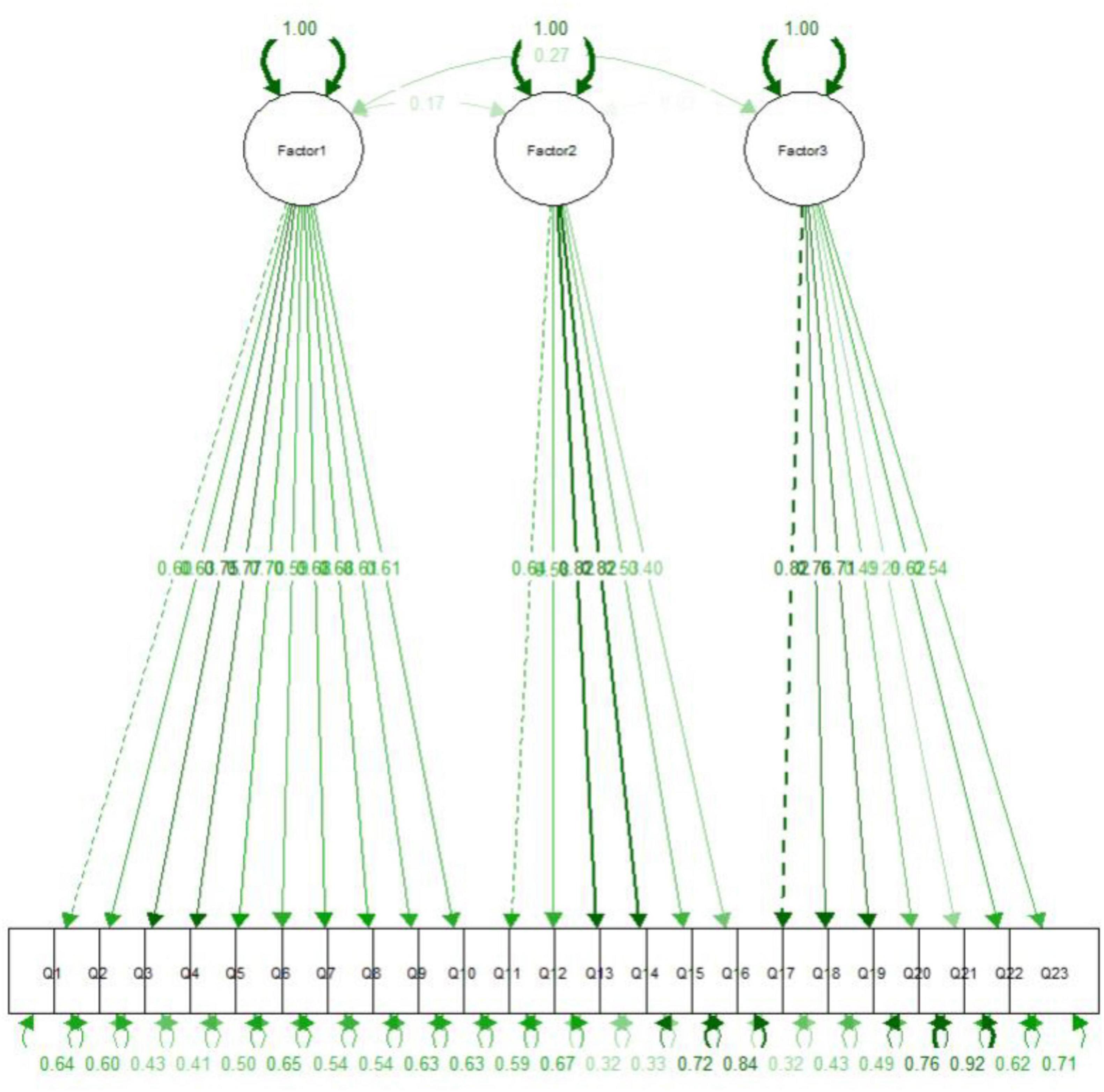

Confirmatory factor analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good model fit for the hypothesized three-factor structure. The model fit indices supported the adequacy of the model: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.888. Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.875. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.064, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.058. all of which are within acceptable ranges for model fit. Parameter estimates for each item were statistically significant, and the latent factors demonstrated adequate reliability with standardized loadings ranging from 0.507 to 0.928 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis model of university citizenship role (Factors 1), national loyalty (Factor2), and political participation (Factor 3).

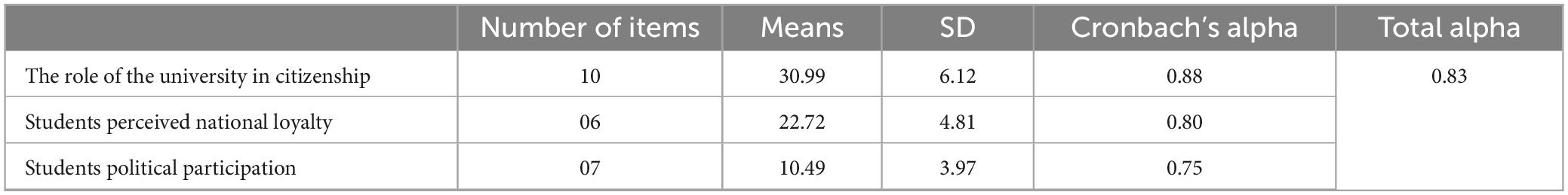

Reliability of the instrument

The Cronbach’s Alpha values for the scale indicate good to excellent internal consistency across the constructs. The role of the university in citizenship has the highest reliability (α = 0.88), reflecting strong cohesion among its 10 items. Similarly, student-perceived national loyalty demonstrates good reliability (α = 0.80), showing that the 6 items effectively measure the construct. Students’ political participation has a slightly lower Alpha (α = 0.75), but it still falls within the acceptable range, indicating sufficient internal consistency for its 7 items. The total Alpha for the scale is 0.83, which confirms the overall reliability of the instrument (Table 2).

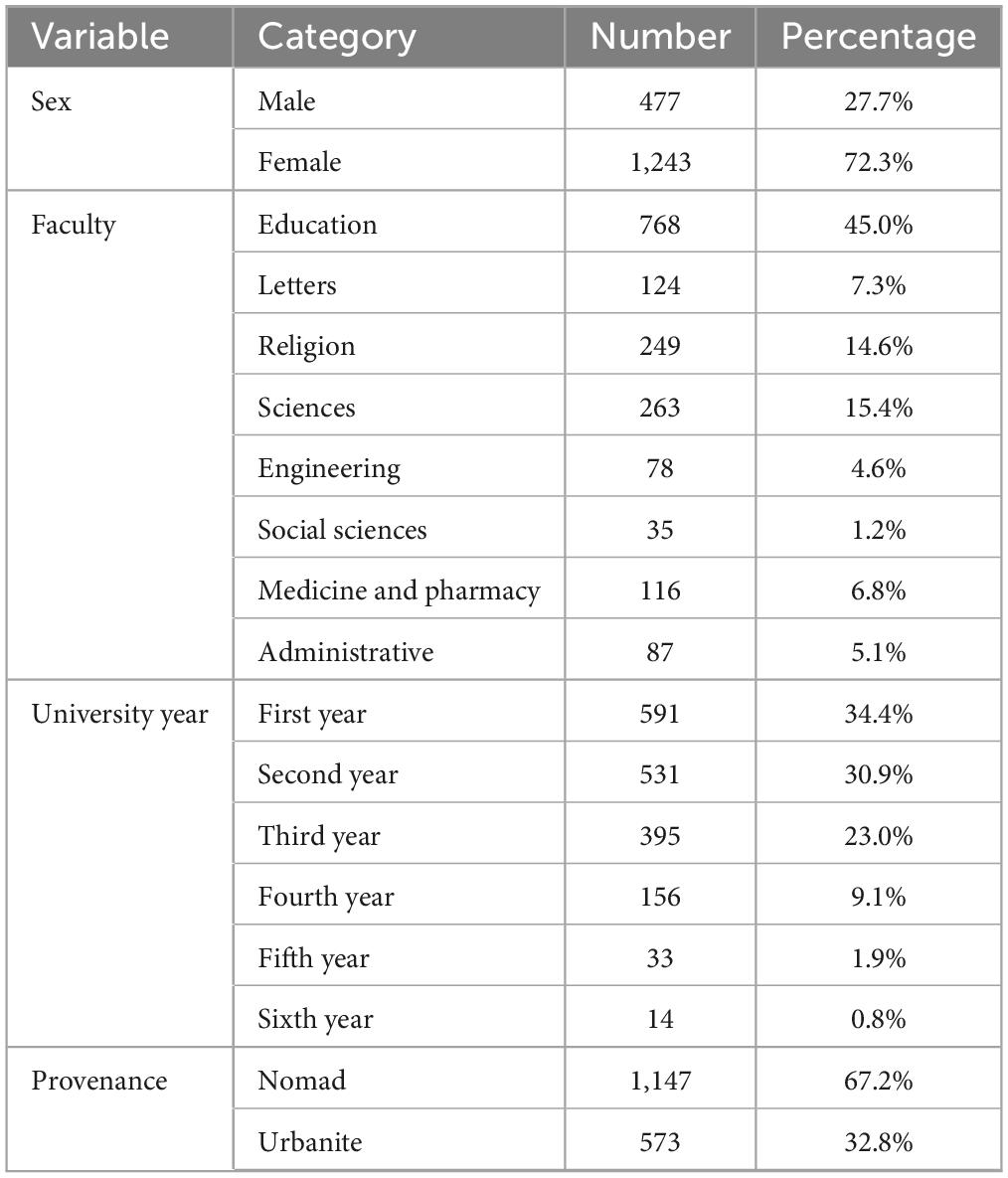

The demographic breakdown of the study participants reveals that a majority of respondents are female (72.3%), with male students making up 27.7% of the total sample. Regarding faculty distribution, the largest group of students belongs to the Faculty of Education (45%), followed by smaller percentages from the Faculties of Letters (7.3%), Religion (14.6%), Sciences (15.4%), and Engineering (4.6%). Other faculties, such as Social Sciences (1.2%), Medicine and Pharmacy (6.8%), and Administrative (5.1%), have even fewer representatives (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and reliability analysis for students’ perceptions of university citizenship role, national loyalty, and political participation.

When considering the academic year of study, most participants are in their first (34.4%) or second year (30.9%), with a significant portion in the third year (23%). Fewer students are in the later years, with only 9.1% in the fourth year, 1.9% in the fifth year, and 0.8% in the sixth year. In terms of geographical origin, a substantial majority of the students come from nomadic backgrounds (67.2%), while 32.8% are urbanites. This distribution suggests a mix of students with varying cultural and geographical backgrounds.

Students’ perspectives on university role in citizenship reinforcement, their national loyalty, and political participation

The mean for role of the university in citizenship is 30.99 with a standard deviation of 6.12, indicating a generally positive view of the university’s contribution in reinforcing students citizenship. For student perceived national loyalty, the mean is 22.72. With a standard deviation of 4.812, showing a very positive perception of national loyalty among students. Finally, students’ political participation has a mean of 10.49 and a standard deviation of 3.97, reflecting lower levels of political engagement with moderate variability among students.

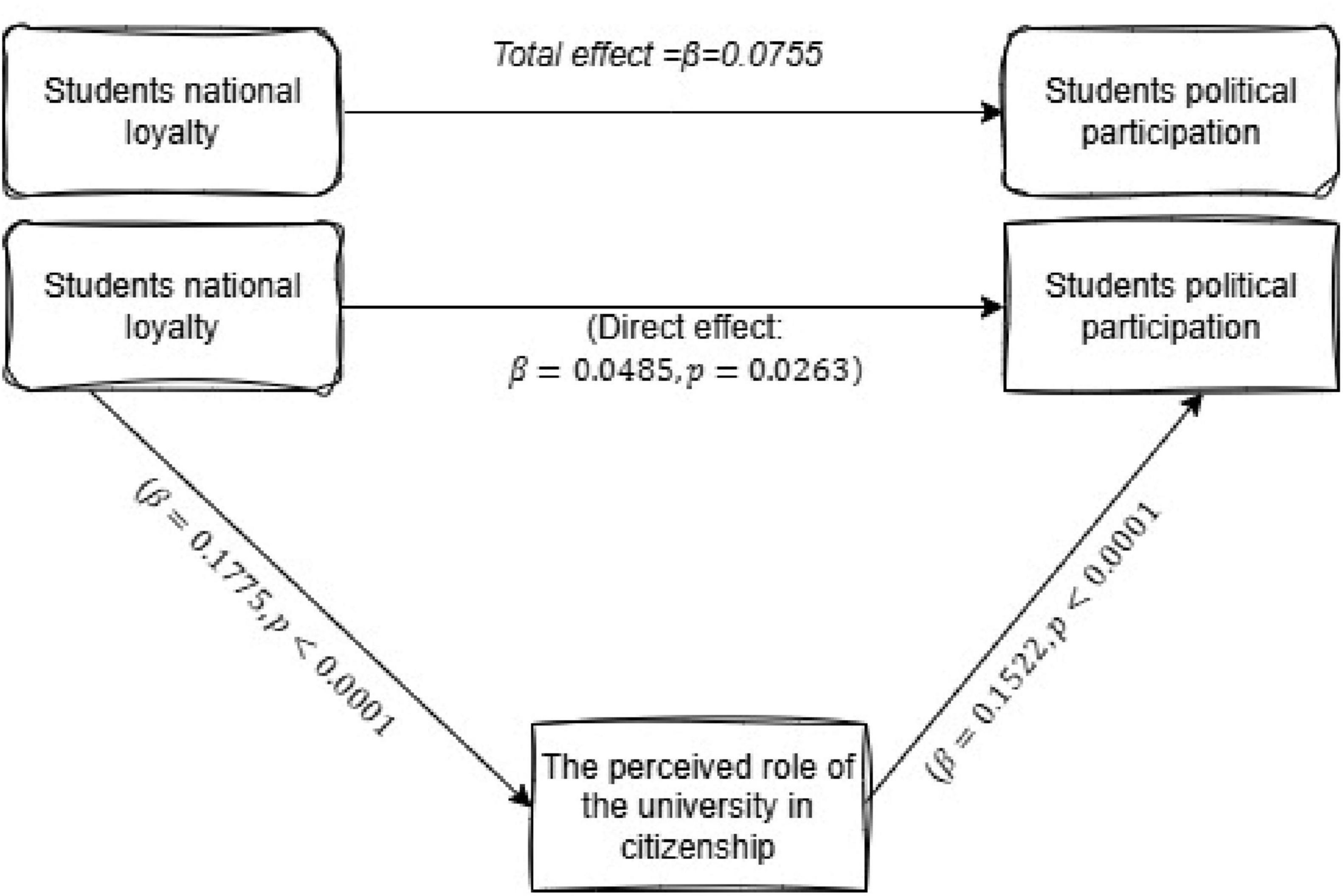

Mediation analysis of the university’s role in citizenship, national loyalty, and political participation

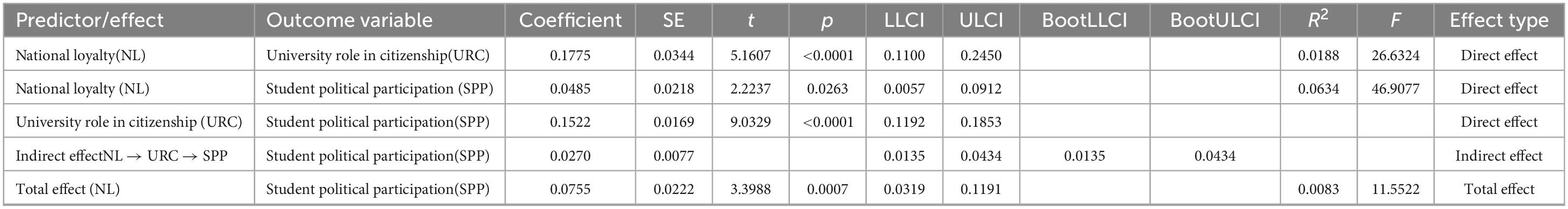

In the mediation analysis, national loyalty was found to significantly predict the university’s role in reinforcing students’ citizenship (β = 0.1775. p < 0.0001). Furthermore, national loyalty had a direct positive effect on political participation (β = 0.0485. p = 0.0263), while the university’s role in reinforcing citizenship also significantly predicted political participation (β = 0.1522. p < 0.0001). Importantly, the analysis showed a significant indirect effect of national loyalty on political participation through the university’s role, with the effect being positive (effect = 0.0270. BootSE = 0.0077. BootLLCI = 0.0137. BootULCI = 0.0435), suggesting that national loyalty enhances political participation by strengthening the perception of the university’s role in promoting citizenship values (Figure 2).

The total effect of national loyalty on community participation was calculated to be β = 0.0755, indicating that national loyalty enhances political participation both directly and indirectly through the university’s role in promoting citizenship values. Overall, the results indicate partial mediation, where both direct and indirect effects contribute to the impact of national loyalty on political participation of students, highlighting the crucial role of universities in fostering civic engagement (Table 4).

Table 4. Direct, indirect, and total effects of national loyalty on political participation through university citizenship promotion.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the important role that universities have in shaping students’ understandings of citizenship and their engagement in political actions. The findings reveal that the students have a positive perception of their university contribution in reinforcing the values of citizenship, that is, they scored high in the mean (30.99). These results underscore that schools are good places for fostering citizenship values. A similar outcome was reported in a previous study conducted at Kuwait University, which also emphasized the positive role of higher education in nurturing active and responsible citizenship (Alzaboun and Al-Rayes, 2023).

Similarly, students had a positive perception of their national loyalty (M = 22.72). It shows that students are connected to and invested in their country, and this is a prerequisite for civic responsibility. However, the results also show that students’ average political participation is surprisingly low, with a mean score of (M = 10.49). While political participation is a vital component of active citizenship, the findings suggest that students may be reletively less engaged in formal political activities compared to other social groups, aligning with trends observed in the literature within the Kuwaiti context (Alduwaila, 2017). Thus, while on the one hand universities might be successful in promoting values of citizenship, on the other, there still some way to go before students are fully prepared to be engaged politically. It is in line with broader patterns observed in the literature. Research has shown that many young people possess limited skills and attitudes necessary for critical engagement in political processes (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022; Sadeli, 2025; Suhariyanto and Rozak, 2025; Weiss, 2020).

In a Nigerian study, the results revealed a notable discrepancy: Although university students generally expressed positive attitudes toward democratic values, they also reported an unwillingness to protest against human rights violations and showed little willingness to actively participate in social and political initiatives (Obiagu et al., 2023).

However, A study conducted in the Chinese context revealed a positive association between political education and political participation. Education was found to enhance individuals’ knowledge, understanding of political processes, and critical thinking skills. This, in turn, can positively influence individuals’ sense of political efficacy by increasing their confidence in their ability to comprehend political issues and engage effectively in political activities (Chen and Madni, 2024).

Importantly, the findings suggest that national loyalty is a critical factor that motivates students’ engagement in political activities. This is consistent with previous research that highlights the positive relationship between national identity and civic engagement (Putnam, 2000). National loyalty appears to foster a sense of responsibility toward one’s country, which, in turn, enhances community involvement. A study conducted in South Korea revealed that national loyalty, as reflected through high levels of national pride, positively influences political participation. Utilizing data from the Korean General Social Survey (2003–2016), the research demonstrated that individuals with greater national attachment were more likely to engage in political activities compared to those with lower levels (Kim and Lee, 2021).

Equally Important, the university’s role in promoting citizenship was found to significantly predict students participation in political activities (β = 0.1522. p < 0.0001). The indirect effect analysis revealed that national loyalty enhances political participation indirectly through the university’s role (effect = 0.0270. BootSE = 0.0077. BootLLCI = 0.0137. BootULCI = 0.0435).

The role of universities in enhancing political participation has been supported by previous studies (Chen and Madni, 2024; Janmaat and Mons, 2023; Yu and Wang, 2025). For instance, a study conducted across nine European countries found that respondents who experienced democratic practices in school or university were more likely to vote and to engage in various forms of political participation (Kiess, 2022).

The findings indicate that national loyalty may influence students’ perceptions of the university’s role in reinforcing citizenship values, which, in turn, motivates them to engage in community activities. Universities have the capacity to translate national loyalty into tangible forms of civic engagement. This mediating mechanism has been explored in other contexts, where educational institutions have been found to play a vital role in transforming personal beliefs into collective actions (Browne and Cudeck, 1992).

From this perspective, the primary goal of citizenship education is to foster greater involvement in democratic society and encourage active participation. This involvement extends beyond the political dimensions of citizenship to encompass social aspects as well. It includes cultivating traits such as a “willingness to volunteer” and a “belief in the ability to make a positive impact on the social environment” (Aoun, 2010; Geboers et al., 2013).

The total effect of national loyalty on students political participation (β = 0.0755) further supports the notion that both direct and indirect pathways contribute to this relationship. The partial mediation observed in this study suggests that while national loyalty directly influences community participation, its impact is amplified when universities contribute to promoting citizenship values. These findings emphasize the dual importance of fostering national loyalty and strengthening universities’ roles in civic education to enhance overall community engagement.

The findings of this research contribute significantly to the ongoing discussion about the evolving role of universities in contemporary societies. A notable shift has been identified: Universities have transitioned from being cultural and civic institutions grounded in a democratic, public-oriented mission to adopting a neoliberal market-driven orientation. Since the economic crisis of the 1970, universities have increasingly prioritized the maximization of economic resources and aligned themselves with business and economic imperatives. This shift has diminished their focus on addressing social needs and fostering a cultural and civic orientation (Andreotti, 2021; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022).

A university’s role extends beyond providing education and technical skills for professional success; it also aims to shape well-rounded individuals who contribute meaningfully to society (El-Kassar et al., 2019). This mission now includes fostering socially responsible generations that embrace sustainable practices and consider the broader community’s interests. As a result, university social responsibility has emerged as a new paradigm in higher education (Altbach, 2008; Giuffré and Ratto, 2014), influencing both internal and external stakeholders. However, students remain the central focus of this shift, as they are directly impacted by the university’s socially responsible actions, which shape their experiences and attitudes (El-Kassar et al., 2019).

Therefore, it is imperative to adopt a university model that extends beyond merely training competent professionals. Such a model should transform internal dynamics to create a democratic space where pressing social and political issues are critically examined. Furthermore, it should prioritize the generation of knowledge, values, and attitudes aimed at fostering meaningful societal improvements and encouraging active political participation as a cornerstone of democratic engagement (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022).

The findings of this study have significant implications for both higher education institutions and policymakers. The positive relationship between national loyalty, the university’s role in promoting citizenship values, and community participation highlights the critical role universities play in fostering social responsibility among students. These findings indicate that universities must look beyond pure academic attainment and development of intellectual ability to an equally important commitment to fostering national loyalty and citizenship values among their students as part of their educational mission. Universities can promote national belonging and echo it through active citizenship in campuses and communities.

For policymakers, the study offers further reasons why civic education and social responsibility should be part of a university’s curricula — creating well-informed citizens who are engaged in their communities. Such elements should be taken into account for the design of the future higher educational strategies and policies focused on maximizing individual and societal contributions of university graduates.

Although this research contributes significantly to understanding the role of universities in promoting citizenship values and the impact of national loyalty on political participation, several limitations should be noted. First, the study relies on self-reported data, which is vulnerable to social desirability or other response biases. Even with attempts to keep respondents anonymous, biases can still pose a threat to the accuracy of responses among such sensitive issues as national loyalty and political activism. Furthermore, although the study examines the direct and indirect impacts of national loyalty and university citizenship roles, it omits potentially significant other variables, such as students’ socio-economic backgrounds, personal values, or previous experiences with civic engagement. Importantly, the sample was pre-dominantly composed of female students from the Education department, which may have influenced the overall trends observed. Further studies can also explore these variables to give a clearer picture of the various factors contributing to community participation. Last, the study has a cross-sectional design that limits the possibility of making causal inferences. Longitudinal and interventional studies would help to evaluate how experiences of national loyalty and university citizenship roles change over time and how they contribute to students’ engagement in community activities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the relationship between national loyalty, citizenship value promoted by universities, and political participation of students. The findings highlight the important role of universities in developing active citizens and narrowing the gap between individual loyalty to nation-building and civic engagement. These findings have important implications for policymakers and educators aiming to design programs that promote national loyalty, civic responsibility and active participation among young people.

To strengthen the promotion of citizenship within higher education, university leaders and educators should consider integrating civic education more explicitly into curricula across all disciplines, not only within education departments. Co-curricular initiatives such as service-learning, community engagement projects, and student-led civic forums can provide practical opportunities for students to connect theory with action. Policies that support inclusive participation—particularly among underrepresented groups—and promote critical discussions around national identity, democratic values, and public service are essential. Additionally, collaboration with civil society organizations and government agencies can help create pathways for sustained civic involvement beyond the university. Prioritizing faculty development in citizenship education and allocating institutional resources to support civic engagement initiatives will also be key to fostering a campus culture that values active, responsible citizenship.

Future research could explore how specific curricular or extracurricular interventions influence students’ civic behaviors over time, and whether these effects differ across cultural or institutional contexts. Longitudinal studies may also provide deeper insights into how university experiences shape political engagement and national identity in the long term.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Department of Applied Psychology of the Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences, fez, Morocco (CEFLSH.02/2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. DA: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abreu, M. A., and Velázquez, D. C. (2019). Neutrosophic model based on the ideal distance to measure the strengthening of values in the students of Puyo university. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 26, 97–104.

Abu El-Haj, T. R., and Bonet, S. W. (2011). Education, citizenship, and the politics of belonging: Youth from muslim transnational communities and the “War on Terror.”. Rev. Res. Educ. 35, 29–59. doi: 10.3102/0091732X10383209

Aldhafiri, A. F. J., and Alsaeed, A. A. S. (2024). The Role of Secondary School Principals in Kuwait in Developing the Values of Loyalty and National Belonging among the Students of Their Schools. 531–547. Available online at: https://www.jaesjo.com/index.php/conf/article/view/763 (accessed May 24, 2025).

Alduwaila, A. E. J. S. (2017). “Influence of family role on political participation intention among university students in the state of kuwait,” in Proceedings of the 25th International Academic Conference, (Paris: OECD).

Al-Fadhli, S., and Al-Saleh, Y. (2012). The impact of facebook on the political engagement in Kuwait. J. Soc. Sci. 40, 11–24.

Altbach, P. (2008). The Complex Roles of Universities in the Period of globalization. London: Palgrave MacMillan

Alzaboun, M., and Al-Rayes, A. A. (2023). The role of Kuwaiti universities in developing awareness of political participation among their students from students’ point of view. Assoc. Arab. Univer. J. Educ. Psychol. 21:6.

Andreotti, V. (2021). Depth education and the possibility of GCE otherwise. Globalisation Soc. Educ. 19, 496–509. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2021.1904214

Aoun, G. (2010). “L’engagement social des étudiants universitaires: Expérience de l’université saint-joseph de beyrouth,” In Proceedings of the Arab Regional Conference on Higher Education (ARCHE 10+), UNESCO, Cairo. Cairo: UNESCO

Astin, H. S., and Antonio, A. L. (2004). The impact of college on character development. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2004, 55–64. doi: 10.1002/IR.109

Banks, J. A. (2004). “Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world,” in the educational forum. Vol. 68. Taylor & Francis Group, 2004.

Banks, J. A., and Banks, C. A. M. (2020). Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives. Available online at: https://books.google.fr/books?hl=ar&lr=&id=ceGyDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR17&dq=%09Banks,+J.+A.+(2004).+Multicultural+education:+Issues+and+perspectives.+John+Wiley+%26+Sons.&ots=TuGB1FlsvE&sig=5aUnd0vrDPAY2Kp0BbWRISiDRnM (accessed May 24, 2025).

Beaumont, E., Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., and Torney-Purta, J. (2006). Promoting political competence and engagement in college students: An empirical study. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 2, 249–270. doi: 10.1080/15512160600840467

Bénéï, V. (2005). Manufacturing Citizenship: Education and Nationalism in Europe, South Asia and China, ed. V. Benei (London: Routledge), doi: 10.4324/9780203015919

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005

Carpendale, J., Delaney, S., Rochette, E., King, C., Cheung, G., Wan, K., et al. (2019). The impact of audience response systems (or clickers), when used in combination with a pedagogical strategy, in a large introductory human physiology course. Mol. Carcinogenesis 8, 1040–1048. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i06.11490

Chen, M., and Madni, G. R. (2024). Unveiling the role of political education for political participation in China. Heliyon 10:e31258. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31258

Cogan, J., and Derricott, R. (2014). Citizenship for the 21st Century: An International Perspective on Education, ed. C. John (London: Routledge), doi: 10.4324/9781315880877

Connor, J. (2007). “National loyalty,” in The Sociology of Loyalty (Boston, MA: Springer), 77–100. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71368-7_5

Dam, G., Ten, Dijkstra, A. B., Van der Veen, I., and Van Goethem, A. (2020). What do adolescents know about citizenship? Measuring student’s knowledge of the social and political aspects of citizenship. Soc. Sci. 9, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/socsci9120234

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York, NY: MacMillan.

El-Kassar, A. N., Makki, D., and Gonzalez-Perez, M. A. (2019). Student–university identification and loyalty through social responsibility: A cross-cultural analysis. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 33, 45–65. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-02-2018-0072

Fateminia, M. A., and Rezanezhad, H. (2023). Sociological explanation of national loyalty among teachers in Tehran. Two Quart. J. Contemp. Sociol. Res. 12, 97–132. doi: 10.22084/CSR.2023.26170.2097

Feezell, J. (2013). Review of making civics count: Citizenship education for a new generation. J Polit. Sci. Educ. 9, 249–250. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2013.771013

Fletcher, G. P. (2011). Loyalty: An Essay on the Morality of Relationships. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195098327.001.0001

Galston, W. A. (2001). Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 4, 217–234. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV.POLISCI.4.1.217

Geboers, E., Geijsel, F., Admiraal, W., and Dam, G. (2013). Review of the effects of citizenship education. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 158–173. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2012.02.001

Giuffré, L., and Ratto, S. E. (2014). A new paradigm in higher education: University social responsibility (USR). J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 3, 2334–2978.

Granhenat, M., and Abdullah, A. N. (2017). Using national identity measure as an indicator of malaysian national identity. J. Nusantara Stud. 2:214. doi: 10.24200/jonus.vol2iss2pp214-223

Gutmann, A. (1999). Democratic Education: Revised Edition - Google Scholar. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hamilton, D., and Fauri, D. (2001). Social workers′ political participation: Strengthening the political confidence of social work students. J. Soc. Work Educ. 37, 321–332. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2001.10779057

Heydarpour, B., Mirzazadeh, F., Beygloo, A., and Hassanifar, A. (2022). Measuring Socio-political participation on political trust in the elections of west Azerbaijan province from 2011 to 2019. Int. J. Polit. Sci. 12, 79–98.

Highton, B., and Wolfinger, R. E. (2001). The first seven years of the political life cycle. Am. J. Polit Sci. 45:202. doi: 10.2307/2669367

Hoskins, B. L., and Mascherini, M. (2009). Measuring active citizenship through the development of a composite indicator. Soc. Indicators Res. 90, 459–488. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9271-2

Isac, M. M., Maslowski, R., Creemers, B., and van der Werf, G. (2014). The contribution of schooling to secondary-school students’ citizenship outcomes across countries. School Effect. School Improvement 25, 29–63. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2012.751035

Janmaat, J. G., and Mons, N. (2023). Tracking and political engagement: An investigation of the mechanisms driving the effect of educational tracking on voting intentions among upper secondary students in France. Res. Papers Educ. 38, 448–471. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2022.2028890

Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., and Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. J. Polit. 71, 782–799. doi: 10.1017/S0022381609090719

Kalaycioglu, E., and Turan, I. (1981). Measuring political participation: A cross-cultural application. Comp. Polit. Stud. 14, 123–135. doi: 10.1177/001041408101400106

Kenski, K., and Stroud, N. J. (2006). Connections between internet use and political efficacy, knowledge, and participation. J. Broadcasting Electronic Media 50, 173–192. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem5002_1

Kiess, J. (2022). Learning by doing: The impact of experiencing democracy in education on political trust and participation. Politics 42, 75–94. doi: 10.1177/0263395721990287

Kim, G., and Lee, J. M. (2021). National pride and political participation: The case of South Korea. Asian Perspect. 45, 809–838. doi: 10.1353/apr.2021.0034

Lawton, D., Cairns, J., and Gardner, R. (2004). Education for Citizenship, (Milton Park: Taylor and Francis), doi: 10.4324/9781315173719-7

Leonard, M., and Spyrou, S. (2011). Children’s educational engagement with nationalism in divided Cyprus. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 31, 531–542. doi: 10.1108/01443331111164124

Leroux, G. (2019). Le défi pluraliste. Éduquer au vivre-ensemble dans un contexte de diversité. Éduc. Francophonie 46, 15–29. doi: 10.7202/1055559ar

Levinson, M. (2012). Prepare students to be citizens. Phi Delta Kappan 93, 66–69. doi: 10.1177/003172171209300716

Marantz, H. (1993). Loyalty and identity: Reflections on and about a theme in fletcher’s loyalty. Crim. Justice Ethics 12, 63–68. doi: 10.1080/0731129X.1993.9991941

Morrow, E., and Scorgie-Porter, L. (2017). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster), doi: 10.4324/9781912282319

Nie, N., Junn, J., and Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=q93-Yf9nzMkC&oi=fnd&pg=PR17&ots=eLqTZU-Kdl&sig=NM2vcciUiw5Ac0gvWQx_udpFObk (accessed April 24, 2025).

Obiagu, A. N., Machie, C. U., and Ndubuisi, N. F. (2023). Students’ attitude towards political participation and democratic values in nigeria: Critical democracy education implications. Can. J. Family Youth 15, 14–32. doi: 10.29173/cjfy29896

Pérez-Rodríguez, N., De-Alba-Fernández, N., and Navarro-Medina, E. (2022). University and challenge of citizenship education. Professors’ conceptions in training. Front. Educ. 7:989482. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.989482

Poulsen, L. N. S. (2020). Loyalty in world politics. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 26, 1156–1177. doi: 10.1177/1354066120905895

Pritzker, S., Springer, M. J., Mcbride, A. M., and Warren, G. (2012). Learning to Vote: Informing Political Participation Among College Students. St. Louis, MO: Washington University.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon Schuster, doi: 10.4324/9781912282319

RStudio (2011). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 0.97.311). J. Wildlife Manag. 75, 1753–1766.

Sadeli, E. H. (2025). Strengthening democracy through campus: The influence of education on student political participation. Qalamuna 17, 99–110. doi: 10.37680/QALAMUNA.V17I1.6762

Scourfield, J., Dicks, B., Drakeford, M., and Davies, A. (2006). Children, Place and Identity: Nation and Locality in Middle Childhood, (London: Routledge), 1–175. doi: 10.4324/9780203696835

Suhariyanto, D., and Rozak, A. (2025). Political participation, civic education, and social media on Generation z’s political engagement. Eastasouth J. Soc. Sci. Human. 2, 161–170. doi: 10.58812/ESSSH.V2I02.455

Terhune, K. W. (1965). Nationalistic aspiration, loyalty, and internationalism. J. Peace Res. 2, 277–287. doi: 10.1177/002234336500200305

Tonyeme, B. (2021). La citoyenneté en contexte démocratique: Quelle autorité de l’éducateur? J. La Recherche Sci. l’Univers. Lomé 23, 137–148.

Verba, S., and Brady, H. E. (1996). Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weiss, J. (2020). What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:535973. doi: 10.3389/FPOS.2020.00001/BIBTEX

Willeck, C., and Mendelberg, T. (2022). Education and political participation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 25, 89–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-014235

Yasein Salman, F., and Mohammad Harafsheh, I. (2020). The role of the faculty members at the hashemite university in strengthening the values of global citizenship from the students’ point of view. Int. J. Innov. Creativity Chnge 7, 18–35. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4494549

Keywords: citizenship, mediation, national loyalty, political participation, university students

Citation: Watfa AA and Ait Ali D (2025) From national loyalty to student political participation: the mediating effect of university citizenship promotion. Front. Educ. 10:1600175. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1600175

Received: 26 March 2025; Accepted: 13 June 2025;

Published: 11 July 2025.

Edited by:

Titus Alexander, Democracy Matters, United KingdomReviewed by:

Elisa Navarro-Medina, University of Seville, SpainAziz Naciri, Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Watfa and Ait Ali. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Driss Ait Ali, ZHJpc3MuYWl0YWxpQHVzbWJhLmFjLm1h

Ali Assad Watfa

Ali Assad Watfa Driss Ait Ali

Driss Ait Ali