- Department of Educational Studies, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

The implementation of self-regulated learning (SRL) in primary and secondary schools is complex and requires a sustainable long-term development of the complete school. To support school leaders and their school team to implement SRL, a two-year school-wide professionalization trajectory was designed in collaboration with an in-service teacher professionalization organization. School leaders participated in a professional learning community (PLC) and were guided by process coaches from the in-service teacher professionalization organization. This study focuses on these coaches and more specific on (1) their roles and responsibilities and (2) the challenges they face in guiding SRL-focused professionalization programs. Bi-monthly focus group discussions with the process coaches were executed to gain more insight in their perspectives. In total, nine focus group discussions were organized, and thematic analysis was used to examine the qualitative data collected during these. Four roles for the process coaches could be identified throughout the two-year professionalization trajectory, namely the roles of a coach, an expert, a coordinator, and a learner. In these roles, the process coaches experienced various challenges and tensions. For example, they faced challenges in defining their role as either a content expert or a facilitator of group learning. Furthermore, the results indicate that challenges were also experienced at other levels, such as within the organization of the PLC, dealing with the diversity among participating school leaders, and involving the school team when implementing SRL school-wide.

1 Introduction

In today's diverse and rapidly changing knowledge society, there is increasing acknowledgment of the pivotal role of self-regulated learning (SRL) as a fundamental competency for both school success and effective lifelong learning (Dent and Koenka, 2016). SRL encompasses a complex, demanding, multifaceted learning process, which involves the combination of a metacognitive (e.g., planning, setting goals, organizing, self-monitoring, and self-evaluating), cognitive (e.g., selection of learning strategies, environmental structuring), motivational (e.g., self-efficacy, task interest, self-attributions) and emotional component (e.g., managing affective states, coping with frustration) (Efklides, 2011; Zimmerman, 2002).

Because self-regulation does not develop automatically, achieving effective SRL skills in students is contingent upon teachers' competencies to foster such skills, and teachers' role in supporting students with SRL appears critical at all school levels (Dignath-van Ewijk, 2016; Donker et al., 2014; Kistner et al., 2010). As SRL involves assigning students increased autonomy and responsibility in their learning, the implementation of SRL in classrooms requires a redefinition of the teacher's role, transforming them into coaches for students' learning processes (Bolhuis and Voeten, 2001; James et al., 2006a,b). While individual teachers play a crucial role, teacher competencies are nurtured through school-wide initiatives promoting SRL, supported by a shared vision and robust leadership. Indeed, research increasingly emphasizes that SRL implementation is a collective responsibility across the entire school community (De Smul et al., 2020; Peeters et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020). A systematic and comprehensive approach with ongoing professional development is crucial for the effective implementation of SRL, positioning the school as a learning organization and highlighting the importance of a systematic approach to professionalizing schools in SRL (James and McCormick, 2009; Muijs et al., 2014; Peeters et al., 2014). It emphasizes the urgent need for educational policies and practices aimed at strengthening the capacity of both teachers and schools to develop an SRL vision and integrate SRL into the curriculum, as well as into everyday classroom and school practices. SRL implementation needs to be encouraged by a supportive school climate (James et al., 2006a,b). In this respect, school leaders can potentially play a positive role in facilitating this climate and in the improvement of teacher performance (Day et al., 2016; De Smul et al., 2020; Duby, 2006). In view of being able to realize this, there is growing acknowledgment that school leaders' practices significantly influence teachers' actions during change processes, highlighting the necessity for targeted professional development at the leadership level (Grissom et al., 2019; Ni et al., 2019).

Effective professionalization initiatives for school leaders must meet various criteria (Daniëls et al., 2019; Goldring et al., 2012). A critical aspect is the significant emphasis on networking and relationship-building with peers (Goldring et al., 2012; Tingle et al., 2019). To facilitate collaborative learning and networking among school leaders, it is essential to form small groups guided by an experienced process coach (Daniëls et al., 2023). However, the role of these coaches in supporting school leaders' professional growth remains underexplored. Given that substantial support and leadership are essential to effect meaningful changes first at the teacher level and subsequently at the student level, further investigation into these areas is imperative. The present study therefore aims to offer an “insider” perspective on process coaches in a professionalization program focusing on the school-wide implementation of SRL and examines how these process coaches can contribute to the effective implementation of SRL across schools.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 School-wide implementation of SRL: an educational innovation

Students differ in their ability to self-regulate and not all are naturally inclined toward self-regulated learning (Boekaerts, 1999). Therefore, it is essential for teachers to foster SRL during classroom practice (Dignath and Büttner, 2008). Meta-analyses have shown that SRL is positively associated with student achievement, motivation, and engagement (Dent and Koenka, 2016; Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Elhusseini et al., 2022). These findings underscore the potential of SRL as a powerful educational approach to improve learning outcomes across diverse student populations. However, despite its proven benefits, research shows that individual teachers' SRL implementation is often limited (Dignath and Büttner, 2018) and that the entire school community must work together to implement SRL (Peeters et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020). Promoting SRL in classrooms involves a substantial shift in teaching practices, requiring teachers to adopt new methods (James et al., 2006a,b). This transition necessitates a supportive school-wide climate that establishes the necessary structures, making SRL a collective mindset and practice rather than an individual responsibility (De Smul et al., 2020; James et al., 2006a,b).

The changes expected of the school can be seen as an educational innovation (James et al., 2006a,b). Successful SRL implementation requires the gradual integration of a shared SRL vision across all grade levels (Hallinger, 2003). This effort requires a significant time investment and the collective commitment from the entire school team (Hilden and Pressley, 2007). Establishing a supportive school climate is essential for fostering the capacity for sustained innovation (Hallinger, 2010; Hopkins et al., 2014; Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008). In this respect, the overall capacity of the school can significantly influence individual teachers' classroom practices (Thoonen et al., 2012).

According to Thoonen et al. (2012), school capacity refers to a school's ability to create a supportive environment for teacher learning and innovation. Regarding the implementation of SRL, little is known about what constitutes such a supportive environment at the school-level (Muijs et al., 2014). Addressing this gap, De Smul et al. (2020) investigated the role of school climate, SRL implementation history, and the role of the school leader in the school-wide adoption of SRL. Their findings suggest that successful SRL implementation is bolstered by a school environment characterized by partnership, communication, collaboration, and participation. Moreover, the study emphasizes the crucial role of a supportive school leader in fostering a positive school climate and driving SRL implementation (De Smul et al., 2020). This aligns with other research on educational innovations, which also emphasizes the importance of strong leadership (Bryk, 2010; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006).

School leaders play a crucial role in fostering an environment that encourages the development of learning skills for both students and teachers. In the context of SRL, they are responsible for creating a supportive environment where teachers can reflect on and implement SRL strategies (James and McCormick, 2009). As the school-wide implementation represents an educational innovation, school leaders become change agents (Acton, 2021). “A change agent is anyone who has the skill and power to stimulate, facilitate, and coordinate the change effort” (Lunenburg, 2010, p.5). Literature frequently highlights that school leaders hold the primary responsibility for the challenging task of continuously implementing school reforms and innovations (Acton, 2021; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006). However, research of Acton (2021) indicates that school leaders often receive minimal formal professional development on effectively managing and influencing change in their schools. There is growing recognition that school leaders need to engage in professional development to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge for effective leadership. Adequate and tailored preparation for school leaders is crucial (Goldring et al., 2012; Grissom et al., 2019; Ni et al., 2019). Despite increased attention to the professionalization of school leaders, research on their professional development remains limited (e.g., Daniëls et al., 2019; Goldring et al., 2012; Grissom et al., 2019).

2.2 Professionalization of schools on SRL via PLC with school leaders

Research on the professionalization of schools has predominantly focused on the professional development of teachers, with less emphasis on the continuous learning of school leaders. In the realm of teacher professionalization, professional learning communities (PLCs) have become a standard practice in schools (Vangrieken et al., 2017). PLCs address the limitations of sporadic and decontextualized professional development initiatives, such as study days and lectures, which are often isolated from practical application (Watson, 2014).

The concept of a PLC is challenging to decipher due to the various interpretations and diverse terminology used in the literature (Lomos et al., 2011). Despite the lack of a universal definition, there is a broad international consensus that a PLC is “a group of people sharing and critically interrogating their practice in an ongoing, reflective, collaborative, inclusive, learning-oriented, growth-promoting way” (Stoll et al., 2006, p. 223). Stoll et al. (2006) distinguish three key characteristics of PLCs: collective responsibility, reflective dialogue, and deprivatised practice (Stoll et al., 2006; Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008). While collective responsibility, a common interpersonal PLC characteristic, refers to the idea that participants in successful PLCs do not consider school improvement, innovation and student learning as a responsibility solely assigned to one school, reflective dialogue and deprivatised practice are more behavioral, interpersonal PLC characteristics (Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008). Reflective dialogue involves participants engaging in deep discussions with colleagues and deprivatised practice refers to participants sharing their methods openly to enhance their effectiveness (Stoll et al., 2006). This may include activities such as observing each other or providing and receiving feedback.

Involving teachers in PLCs within schools can change teachers' perceptions, positively impact their instructional practices, and enhance student learning outcomes (Christensen and Jerrim, 2025; Lomos et al., 2011). However, most literature on PLCs in schools focuses on teacher learning, resulting in a scarcity of research on the collective learning of school leaders and cross-school PLCs involving school leaders (Coenen et al., 2021).

The limited studies that focus on PLCs with school leaders reveal that, despite being time-consuming, school leaders perceive their participation in PLCs as a valuable investment (Coenen et al., 2021). Tanghe and Schelfhout's (2023) research on a longitudinal professionalization program for school leaders via PLCs indicates that the most effective approach combines theoretical frameworks, peer learning, concrete action plans, and school-specific coaching (Tanghe and Schelfhout, 2023). This combination fosters learning-driven actions within schools. This aligns with the three key organizational conditions identified by Coenen et al. (2021): clear and realistic group objectives, effective steering and preparation, and embedding participation logically in participants' daily routines and activities (Coenen et al., 2021). Daniëls et al. (2023) support these findings, emphasizing the importance of reflection in combination with peer learning, peer feedback, and the need for small groups guided by experienced process coaches (Daniëls et al., 2023). Similarly, school leaders in Tanghe and Schelfhout's (2023) study highlighted the crucial role of process coaches in the professionalization program, noting the positive effect and added value they experienced from this support.

2.3 The role of the process coach in PLCs

Previous research underscores the critical role of leadership within PLCs (Coenen et al., 2021; Margalef and Roblin, 2016; Prenger et al., 2019; Tanghe and Schelfhout, 2023). It emphasizes the necessity of having an experienced individual to guide learning processes through feedback, reflection, and providing access to relevant sources while cultivating an open and trusting environment (Daniëls et al., 2023; Margalef and Roblin, 2016). This individual, referred to as the “process coach,” can significantly impact the effectiveness of learning processes, either positively or negatively (Tanghe and Schelfhout, 2023). Poor leadership by the process coach can notably decrease participants' satisfaction with the PLC initiative, as well as their perceived acquisition of knowledge and skills (Honig and Rainey, 2014; Prenger et al., 2017). Despite its importance, the specific responsibilities of a process coach remain inadequately defined in the existing literature. Coenen et al. (2021) and Prenger et al. (2017) distinguish three roles: the process coach as a coach, an expert and a coordinator.

2.3.1 Process coach as a coach

As a coach, it is essential to stimulate reflection and learning among group members (Coenen et al., 2021). The coach acts as a team facilitator, paying attention to group development processes and allowing time for mutual understanding, professional inquiry, and connecting shared stories (Prenger et al., 2017). By doing so, the process coach fosters a critical yet constructive discussion, emphasizing the benefits of diversity, conflict, and failure, as each of these elements serves as a learning opportunity (Schelfhout et al., 2015). In the research of Coenen et al. (2021), the coaching role was most prominent during the PLCs.

2.3.2 Process coach as an expert

As an expert, the coach provides information and answers content-specific questions (Coenen et al., 2021). However, Coenen et al. (2021) found that school leaders often perceived the knowledge of the process coach as inadequate. This finding aligns with the research of Assen and Otting (2022), which indicated that process coaches tend to pay little attention to theory as a source of learning.

For the school-wide implementation of SRL, it is crucial for process coaches to possess both content knowledge about SRL (CK-SRL) and pedagogical content knowledge about SRL (PCK-SRL) (Karlen et al., 2020). CK-SRL encompasses understanding fundamental concepts, such as terminology and theoretical models, as well as the ability to justify various motivational, cognitive, and metacognitive strategies for SRL (Karlen et al., 2020). PCK-SRL involves knowing how to stimulate SRL in the classroom and support students through both direct instruction (e.g., modeling, explaining learning strategies) and indirect instruction (e.g., creating an optimal learning environment) (Barr and Askell-Williams, 2020; Karlen et al., 2020).

2.3.3 Process coach as a coordinator

A third role involves acting as a coordinator. In this role, the process coach structures the meetings according to the groups' predefined goals, allowing space for exchange, discussion, and reflection (Prenger et al., 2017). The coordinator manages logistical arrangements and ensures that the meetings do not stagnate in merely sharing personal anecdotes and/or frustrations, but instead move toward in-depth reflection and actual co-creation (Schelfhout et al., 2015).

3 The present study

Evidence from several meta-analyses indicates that fostering SRL enhances students' academic achievement (Dent and Koenka, 2016; Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Elhusseini et al., 2022). Developing SRL skills in students requires substantial support from teachers (Dignath-van Ewijk, 2016). However, teachers often struggle with SRL implementation (Dignath and Büttner, 2018). Effective SRL implementation necessitates a collective effort from the entire school community (Peeters et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020). Studies highlight the crucial role of supportive school leaders in positively influencing school climate and driving SRL implementation, viewing it as an educational innovation (Bryk, 2010; De Smul et al., 2020; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006). There is increasing recognition of the need for school leaders to engage in tailored professionalization to acquire essential skills and knowledge. However, research on school leaders' professional development remains limited (Daniëls et al., 2019; Goldring et al., 2012; Grissom et al., 2019; Ni et al., 2019). While most research focuses on within-school PLCs on the teacher level (Chapman and Muijs, 2014), the present study focuses on between-school PLCs involving school leaders. The focus on SRL in the PLCs is grounded in meta-analytic evidence showing its positive impact on student learning (Dent and Koenka, 2016; Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Elhusseini et al., 2022). Previous research underscores the critical role of leadership within a PLC (Coenen et al., 2021; Margalef and Roblin, 2016; Prenger et al., 2017). It emphasizes the need for an experienced individual to guide learning processes through feedback, reflection, and providing access to relevant sources, while cultivating an open and trusting environment (Daniëls et al., 2023; Margalef and Roblin, 2016). Given that effective SRL integration hinges on robust leadership and cohesive support systems, these process coaches play a critical role in guiding PLCs. However, their specific responsibilities and impact are underexplored. The present study therefore aims to provide an insider perspective on the role and challenges faced by process coaches in SRL-focused professionalization programs. It examines how they contribute to effective SRL implementation across schools and argues that a deeper understanding of this role is essential for enhancing school leadership and, ultimately, student learning outcomes.

The following research questions are addressed:

(1) Which specific roles and responsibilities of process coaches in SRL-focused professionalization programs come to the fore?

(2) What challenges do process coaches face in guiding SRL-focused professionalization programs, and how do they address these challenges?

4 Materials and method

4.1 Context of the study

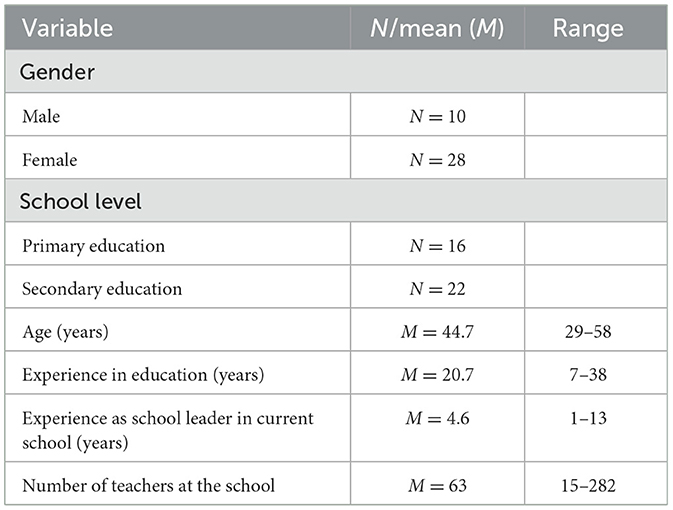

This study follows a qualitative case study approach (Thomas, 2011), aiming to explore the role of process coaches within the specific context of an SRL-focused professional development program (PDP). To gain deeper insights, the researchers collaborated with an in-service teacher professionalization organization that provides pedagogical support and professional development opportunities for school leaders and teachers. As part of their work, they launched the professionalization program “Everyone is a leader of learning,” aimed at supporting school leaders in enhancing their ability to foster effective learning environments in their respective schools, with a particular focus on the implementation of SRL. The program spanned a 2-year professionalization trajectory, engaging 16 primary and 22 secondary school leaders. In Belgium, school leaders typically participate in structured networks. For this professionalization program, groups of school leaders from the same network voluntarily enrolled as cohorts forming PLCs. School leaders varied considerably in terms of leadership experience, school context, and motivation for joining: some joined to collaborate within PLCs, others to focus on SRL, and some because participation was encouraged by their network. Table 1 presents background information on the participating school leaders.

During the first year of the professionalization, the school leaders participated in collaborative learning within PLCs focused on SRL and its implementation. Eight PLCs with five or six school leaders each were set in motion, supported by a process coach. The process coaches are employed by the in-service teacher professionalization organization, where guiding school leaders is part of their job. Throughout this first year, school leaders engaged in various activities within their PLCs, including viewing and discussing knowledge clips on SRL. All 21 SRL skills from Zimmerman's (2002) framework (e.g., goal setting, self-monitoring, help-seeking) were addressed. The PLCs met on average seven times during the first year of the professionalization program. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, most of the meetings were held online.

In the second year, PLCs were able to meet in person, averaging five meetings per group. During this period, school leaders applied insights gained from their PLCs to support their school teams in implementing SRL practices, with personalized guidance from their process coaches. Thus, the process coaches not only facilitated school leader professionalization but also helped foster a supportive, school-wide climate for SRL.

To ensure a certain degree of consistency across the PLCs, the professionalization trajectory was centrally coordinated by a staff member of the in-service teacher professionalization organization. This coordinator, a former academic with specific expertise in SRL, provided both theoretical and practical support to the process coaches. While this coordination fostered alignment between the PLCs, each group retained the flexibility to adapt their meetings to the specific needs of their members.

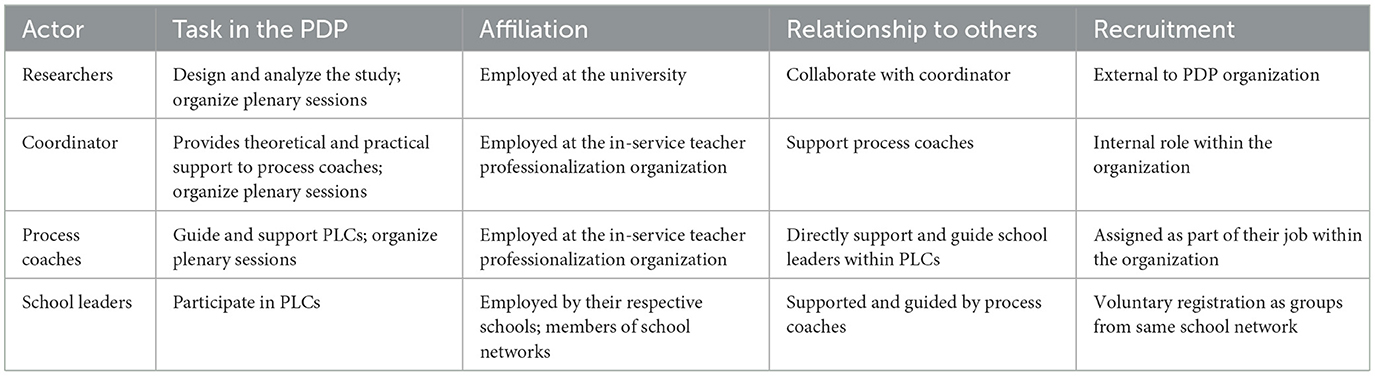

Additionally, the researchers, coordinator, and process coaches jointly organized plenary sessions on leadership, SRL theory, and its classroom and school-level implementation to enhance school leaders' knowledge. Following these sessions, school leaders applied the acquired knowledge in PLC discussions, contextualizing it to their schools. An overview of the key actors involved in this study—including researchers, the coordinator, process coaches, and school leaders—is presented in Table 2.

4.2 Participants

The eight PLCs were each guided by a process coach. The sample included 75% female process coaches. The average age was 49.10 years (SD = 6.58). Coaches' average experience in the in-service teacher professionalization organization was 6.20 years (SD = 4.33), implying that most of them already had some experience in guiding change and innovation processes in schools at the start of the professionalization trajectory. To master SRL theory, the process coaches participated in a train-the-trainer course, offered at no cost and facilitated by the authors of this article. Participation in the training was part of their professional duties within the scope of the professional development program. Additionally, they held regular meetings with the coordinator, who possesses extensive experience in SRL, to ensure consistency and alignment throughout the professionalization trajectory. Moreover, some PLCs experienced changes in their assigned process coach due to illness or employment transitions, and not all participants were able to attend every focus group discussion for similar reasons, such as illness or other work-related obligations.

4.3 Data collection

Focus group discussions with the process coaches were conducted every 2 months to gather information about their experiences, opinions, expectations, questions, and needs concerning the coaching of the school leaders in their respective PLCs. Unlike quantitative research, focus group discussions provide more in-depth information due to the opportunity for asking open-ended questions, probing on provided answers, and observing the interaction between participants (Morgan et al., 1998).

A structured step-by-step protocol guided each focus group to initiate discussion (Morgan et al., 1998). After a brief introduction and a review of the summary from the previous group discussion, participants were invited to individually write down their experiences, opinions, and concerns regarding the PLCs they organized with school leaders, as well as their own knowledge, skills, and professional approaches.

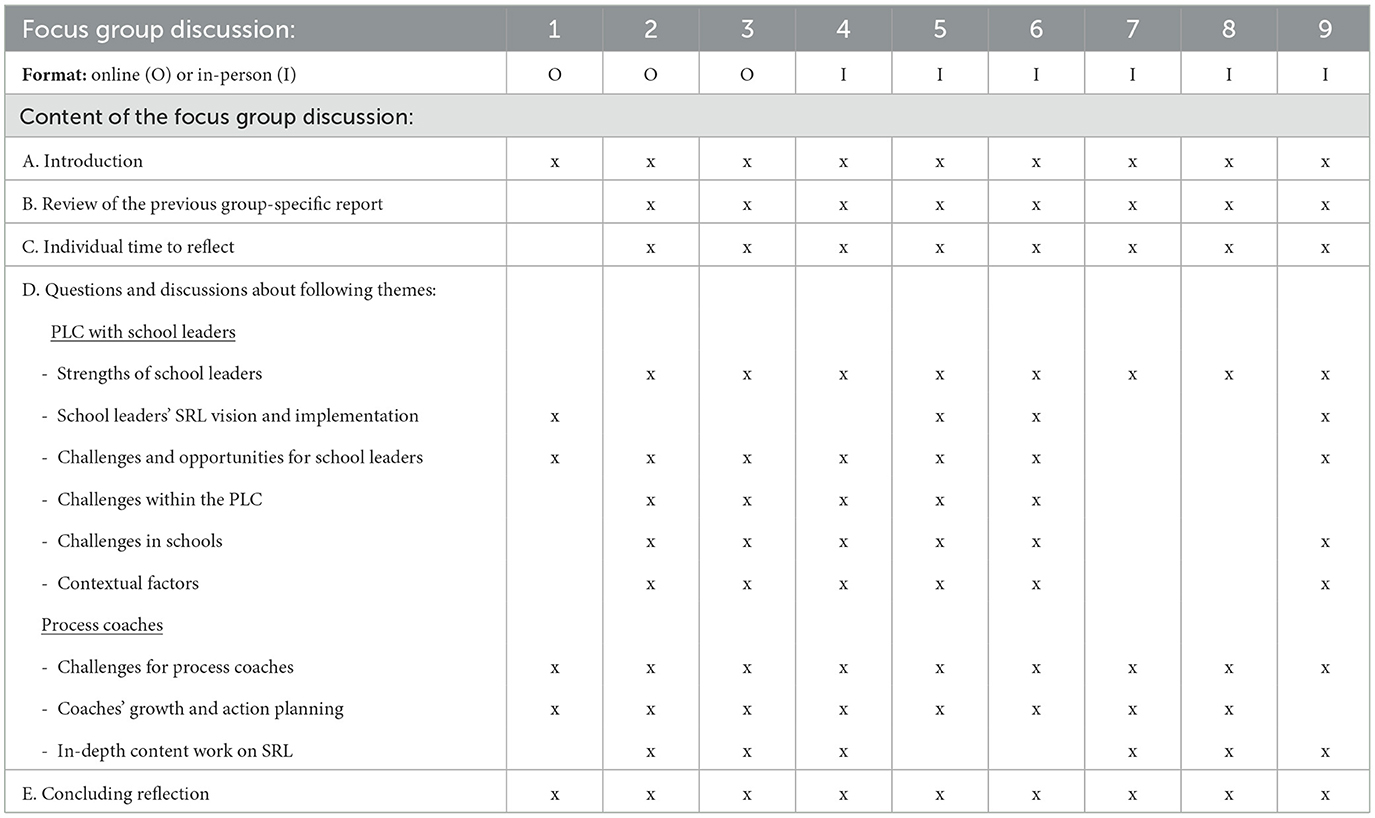

Subsequently, various themes—both personal and related to their experiences with the PLCs—were discussed in depth. Table 3 provides an overview of the main themes that emerged across the focus group discussions.

In total, nine focus group discussions with the process coaches took place, resulting in 987 min of data. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the first three discussions were held online. Each discussion lasted ~2 h on average. All focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed, after obtaining informed consent from the participants.

4.4 Data analysis

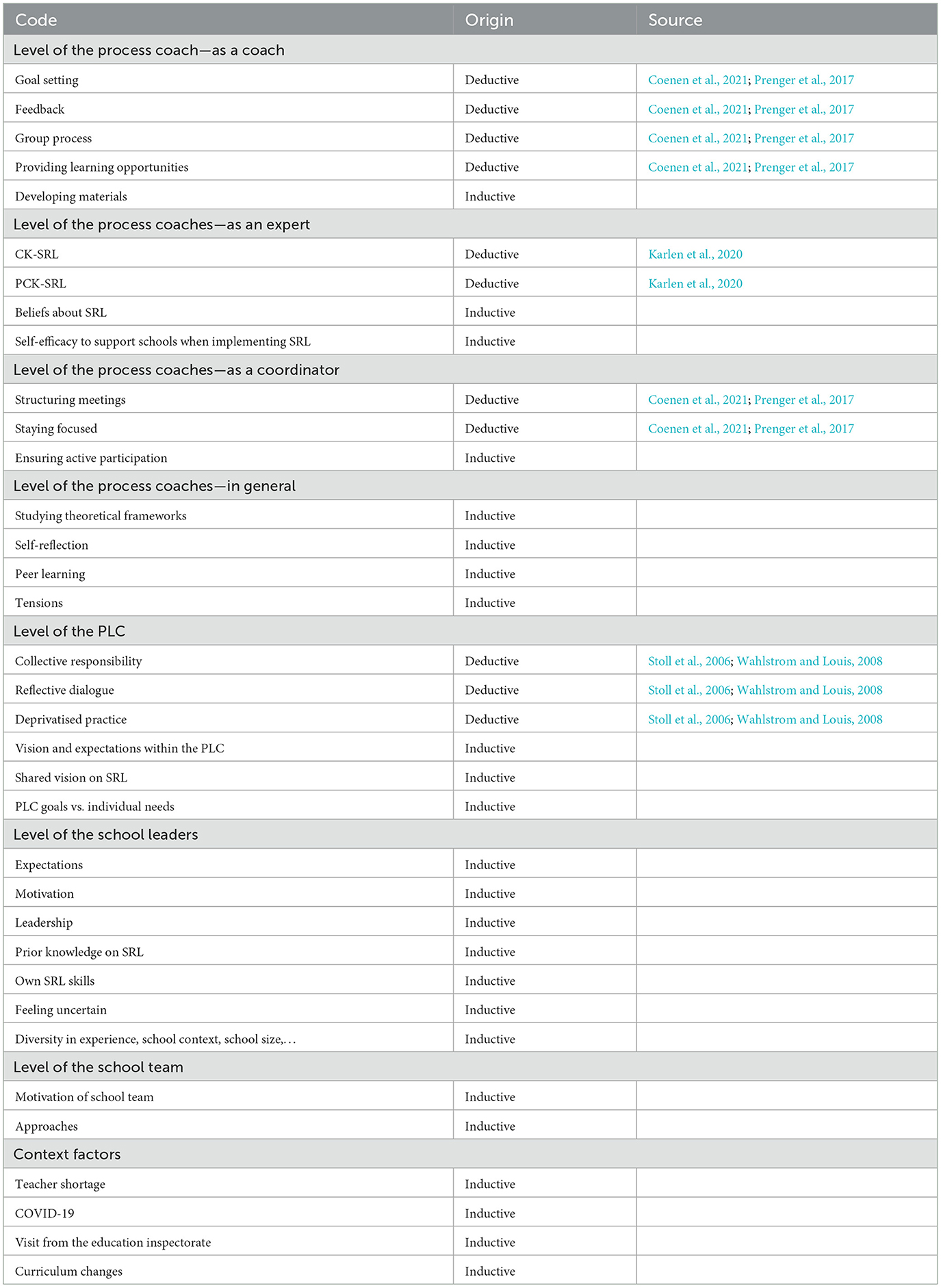

A coding scheme was used to analyse the data thematically in Nvivo. Thematic analysis was chosen because it allows for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data, making it particularly suitable for exploring the complex and nuanced experiences of process coaches (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The coding was performed in three consecutive steps. First, the data from each focus group discussion were summarized in a focus group-specific report (i.e. within-case analyses) (Miles and Huberman, 1994). These summaries guided the construction of themes that aligned with the research questions. Second, in order to ensure the interpretive quality and to minimize potential misinterpretations by the researchers and unclear wording and complexity, all participants in the focus group discussions were asked to review the summary of the previous focus group discussion and reflect on the themes. This resulted in the refinement, removal and consensus-building of items across focus groups. Third, the results of the within-case analyses were integrated in a cross-case analysis. The categories and themes used for the cross-case analysis were informed by both deductive and inductive approaches. Deductively, we drew on existing research on SRL (e.g., Karlen et al., 2020) and literature on process coaches (e.g., Coenen et al., 2021; Prenger et al., 2017) to define a number of a priori codes. At the same time, inductive coding allowed for the identification of new themes and categories that emerged directly from the data, capturing context-specific insights. An overview of the resulting coding categories, along with their theoretical origin (deductive or inductive), is provided in Table 4.

5 Results

5.1 The different roles of the process coaches

For the first research question, which examined the different roles and responsibilities of process coaches in SRL-focused professionalization programs, the thematic analysis identified four distinct roles. Although these roles were not explicitly addressed during the focus group discussions, the analysis revealed their presence, along with some tensions between them.

5.1.1 Process coach as a coach

In this first role, all process coaches prioritize encouraging reflection among the participating school leaders of the PLCs throughout the professionalization trajectory. By focusing on stimulating reflection, process coaches created valuable learning opportunities for the participants. Participant four reflects on the first year of the professionalization program in the fifth focus group discussion as follows:

We consistently initiated discussions with reflective questions, integrating theory to ensure a practical application. This approach was highly valued as it effectively engaged participants; without, their involvement would have been limited. Thus, by continually connecting questions to theory and insights, we fostered meaningful understanding and participation.

To further support this learning process, coaches developed materials that link SRL with existing frameworks already used within the participating schools. This approach aimed to create a shared language among school leaders and teachers, grounded in established theoretical models such as Zimmerman's (2002) framework. By aligning SRL with familiar concepts, coaches sought to make the integration process more accessible and relatable for the participants. In addition, these materials encouraged deeper collective reflection, prompting school leaders to explore concrete ways of embedding SRL practices into daily classroom activities.

In addition to nurturing reflective practices and material development, one coach highlighted the importance of providing targeted feedback. Moreover, all coaches mentioned engaging in goal-setting during the initial PLC discussions, although these goals tended to focus primarily on the objectives of individual schools rather than on the collective aims of the group.

Setting goals collectively presents a challenge, as does maintaining focus on these goals, for both myself and the schools. Schools are currently in an experimental phase, and there is a significant task of integrating these initiatives. Moreover, individual schools have articulated a strong vision, which needs exploration by all participants, particularly in terms of incorporating aspects of SRL. (participant 7, focus group discussion 1)

Despite these important elements that emerged in the role as coach, several challenges also surfaced during the focus group discussions. Some coaches reported difficulties in encouraging reflection when school leaders were eager to shift quickly toward operational issues, which hindered deeper engagement with SRL theory. Others noted that school leaders often needed more time to reflect on SRL principles, which is essential for sustaining progress.

In the domain of goal-setting, the varying motivations of school leaders and the differences in school contexts made it challenging to establish shared, group-level objectives, thereby limiting the focus on collective development processes within the PLCs. Additionally, the infrequent mention of feedback provision suggests potential gaps in the coaches' ability or opportunity to provide appropriate, expert feedback to the school leaders. This gap can also be linked to the coaches' role as an expert, which will be discussed in the following section.

That discrepancy between the role as an expert and the role as a coach requires deep knowledge acquisition. To provide effective feedback and engage with the input of the school leaders, you need to be very familiar with those SRL frameworks yourself. Personally, I still find that aspect challenging. You cannot solely focus on the process because then you cannot provide sufficient feedback on what they bring. This is where your credibility as a coach comes into play, and I find that aspect quite challenging. We have been trained extensively and studied hard in recent months, which has helped us succeed. However, as a coach, you need to study for it, and I cannot emphasize that enough. (participant 4, focus group discussion 4)

5.1.2 Process coach as an expert

Across the focus group discussions, participants mentioned various types of substantive knowledge (e.g., knowledge of PLCs, knowledge of SRL). Given the scope of the study, we focus only on the specific content and pedagogical content knowledge on SRL in the present manuscript. Most coaches recognized the importance of acquiring sufficient content knowledge on SRL (CK-SRL) to effectively guide school leaders in implementing SRL school-wide. They noted that mastering this knowledge is a complex process that demands focused study and commitment.

In addition, grappling with the substance of SRL has consumed considerable time. I needed to create a mind map, engage in study, and pose questions to myself. There is a concern for me about being able to engage in detailed discussions at that level. While I grasp the overarching concept, I find it quite demanding. (participant 2, focus group discussion 1).

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the same coaches frequently referred to CK-SRL throughout the professionalization program, whereas one coach never delved into this topic. This raises questions about whether this coach has adequately mastered the underlying SRL theory herself.

In contrast, PCK-SRL was less explicitly addressed in the discussions. Only one coach demonstrated a clear transition from CK-SRL to PCK-SRL. For instance, participant two identifies in the third focus group discussion the different methods of teaching SRL (direct instruction vs. indirect instruction) when discussing the instructional approach.

Simply gathering what is present in the PLC and linking it to whether it is direct or indirect instruction, that seems to me, at first glance, a safer framework where I increasingly feel comfortable.

Finally, although not explicitly solicited during the discussions, some coaches expressed awareness of their own beliefs regarding SRL, specifically indicating feeling uncertain in their role as experts.

The tools are clear, the theory is clear, and we delve deeper, which I find very challenging. I feel like I am on thin ice because I am somewhat uncertain in this area, which unconsciously causes me to hold back a bit. (participant 2, focus group discussion 4)

5.1.3 Process coach as a coordinator

Throughout the focus group discussions, process coaches assigned the least emphasis to their coordinating role in the PLC. Initially, many coaches invested considerable effort in structuring PLC meetings, including drafting agendas, maintaining portfolios, and managing other organizational aspects. The shift to online meetings due to the COVID-19 pandemic introduced notable challenges in ensuring active participation of all school leaders in the PLC. These challenges went beyond technical difficulties; coaches also struggled to foster spontaneous interaction and to keep participants focused on the PLC tasks. Since participants joined the meetings remotely from their own schools, they were often prone to distractions, which further hindered their engagement and the overall group dynamics. Over time, however, attention to coordination declined, with its importance increasingly taken for granted rather than actively addressed. Only one coach consistently underscored the need to engage and organize school leaders, highlighting the persistent challenges associated with this responsibility.

5.1.4 Process coach as a learner

Beyond the three previously identified roles, we observed that throughout the two-year trajectory, many coaches perceived themselves as learners, highlighting a fourth role for process coaches engaged in providing in-service professionalization.

As SRL experts, the process coaches repeatedly emphasized the need for independent study to master the various theoretical frameworks. In both the initial and final focus group discussions, this ongoing learning was seen as a strength, as it aligned their own learning process with that of the school leaders. However, it also posed challenges in relation to their coaching. More particularly, coaches sought to balance working within the school leaders' zone of proximal development while building enough expertise themselves to effectively guide the PLC.

Self-reflection and peer learning emerged as crucial aspects of this role. Coaches valued sharing experiences, approaches, and materials, as mentioned by participant one in the first focus group discussion:

Also, this focus group is very helpful. It is fascinating to hear how each PLC navigates their path and how each coach approaches it. It makes me reflect on my own journey and facilitates decision-making. A second opportunity that I see: we as coaches are also invited to learn, which fosters connection with the group school leaders. Now, we are truly doing it together!

By the end of the trajectory, some coaches recommended two coaches to facilitate a PLC to reflect and learn from each other in a large group setting (e.g., in the focus groups) but also in pairs shortly after each PLC meeting to collaboratively shape the PLC.

Finally, the role as a learner was strongly related to the roles of expert and coach, shaping how responsibilities were enacted. However, significant differences emerged among the process coaches. Notably, those who emphasized their role as experts also strongly focused on their own learning process. In contrast, coaches who seldom mentioned theoretical frameworks and coaching skills in the focus group discussions tended to see themselves less as learners. Due to the limited mention of the coordination role, no clear connection could be established between it and the role of learner.

5.1.5 Tensions between roles

Tensions between the various roles emerged during the focus group discussions. First, there was a tension between the roles of expert and learner. Some process coaches struggled to balance learning alongside school leaders while maintaining their position as experts with preexisting knowledge and expertise. Second, also related to the expert role, tensions arose between providing theoretical input to school leaders and adopting a coaching stance by encouraging reflection, asking questions and building on existing group knowledge. Participant two struggled with both tensions and formulated her reflections as follows:

It might be that you feel the need to fully master everything before taking the next step with your PLC. Or perhaps not; maybe you are learning by doing. However, what has been emerging for me in recent years, and this relates to the way our organization works, is that our role as process coaches is evolving, along with the associated expectations from the schools. I struggle with this a lot. I constantly question what we are as process coaches. Are we still content experts? Where does our expertise lie?

Finally, uncertainties regarding the coaching role emerged, particularly in the first year of the professionalization trajectory. Two process coaches questioned their position as PLC coaches. Since the school leaders were already collaborating as part of an existing network, with one of the school leaders taking on a coordinating role, these two process coaches observed that this coordinating leader could assume the role of coach within the PLC. However, this was not a uniform pattern across all PLCs and heavily depended on the leadership style of this coordinator and the extent of collaboration prior to the start of this professionalization program.

5.2 Challenges faced by the process coaches

The challenges faced by the process coaches themselves have already been mentioned when discussing their roles. However, for the second research question, challenges and corresponding approaches will be discussed at other levels (i.e., the PLC, individual school leaders and the school team) as well.

5.2.1 Level of PLC

Focusing on the core characteristics of PLCs, namely deprivatised practice, collective responsibility and reflective dialogue, we noticed that the process coaches mainly emphasized the latter. In the first focus group discussion, coaches highlighted many growth opportunities for the participants in the PLC regarding these characteristics. Some groups of school leaders were accustomed to working together but tended to focus solely on exchanging ideas and materials without assuming collective responsibility. They were used to being directed and had no experience with group reflection. During the subsequent focus group discussions the process coaches identified stimulating this group reflection as a key focus of their role. Deprivatised practices and collective responsibility were subsequently seldom mentioned or rarely brought up in the next discussions. This finding prompted a critical assessment of how well the PLCs in this professionalization program met the key criteria. One process coach shared this perspective at the end of the first year. Participant one questioned in the fifth focus group discussion whether she had guided a PLC:

Regarding the PLC, we have reviewed the theory and the prerequisites, but we have not yet implemented it. Our collaboration has not functioned as a PLC this year; the sessions were heavily guided by me, and I introduced the theory on SRL and so on... The school leaders did actively participate, but upon critical examination, it did not constitute a PLC.

Subsequently, a concept linked to collective responsibility is the shared vision on SRL and on what constitutes a PLC. This was discussed during the first focus group sessions, where coaches noted that such a shared vision was often lacking among participants. For example, one process coach explained that several participants viewed the PLC primarily as a space for exchanging practical ideas, rather than for engaging with underlying concepts or theories. When attempts were made to deepen the conversation, some participants became impatient, indicating a preference for quick, concrete outcomes. They addressed this by initiating discussions on the topic. In connection with this shared vision, the coaches perceived the participants' expectations as a challenge. They mentioned that these expectations were not always clear and aligned with the goals of the professionalization program (e.g., the participants expected the coach to be an expert who provides all the content, allowing them to immediately move to operational matters at their school without engaging in reflection). This required time to make these expectations explicit. This issue was not only present at the beginning of the trajectory but also resurfaced at the start of the second year. Coaches emphasized the importance of clearly articulating vision and expectations within the PLC.

Lastly, we observed that many coaches reported a shift in their approach at the start of the second year of the professionalization program. They placed less emphasis on the collective dynamics within the PLC and instead focused more on addressing the individual needs of the school leaders and their respective schools.

5.2.2 Level of individual school leader

At the start of the professionalization program, all process coaches noticed a diversity in the motivations of the school leaders for participation. Some school leaders joined the PLC because it was a requirement from their school network, while others had already been working on SRL at their school for several years and wanted to deepen their understanding. Several process coaches explored these motivations further, aiming to address each one and link it to specific PLC goals.

The diversity also extended to the prior knowledge on SRL of the school leaders, their leadership and their own SRL skills. In the sixth focus group discussion, participant eight noticed the following:

What I have also observed is that a few highly capable school leaders are participating, whereas others have not yet fully developed their own SRL skills to effectively support their teams in the future. The more capable leaders often communicate with each other, exchange ideas, and appreciate each other's strengths. They also openly acknowledge the areas where they still need to improve.

Additionally, substantial differences among school leaders emerged in their experience as a school leader, their tenure at their current school, and the size of the school. Notably, when process coaches in the focus group discussions were asked about the challenges they encountered, these factors were frequently mentioned. One process coach, in particular, highlighted the difficulty of effectively addressing these challenges, emphasizing that the participation of numerous new school leaders in the PLC posed a significant barrier to progress. This coach felt that these leaders needed to prioritize various other school-related matters before fully engaging in the PLC.

Besides diversity, uncertainty among school leaders was another frequently cited challenge. At the start, three process coaches mentioned that some school leaders do not yet see themselves in a coaching role with their teaching staff. They were concerned that implementing SRL on a school-wide basis might be too overwhelming and might take too much time for their team.

Finally, one participant noted that school leaders projected their own uncertainty onto their school team. For example, they may state in the PLC that their team of teachers is not innovation-oriented. However, the process coach suspected that it was, in fact, the school leaders themselves who harbor uncertainties about implementing SRL as a school-wide educational innovation.

5.2.3 Level of the school team

Although the process coaches did not work directly with teaching staff in this professionalization trajectory, many challenges at this level were still discussed in the focus group discussions. These challenges were either mentioned by the school leaders in the PLC or observed by the coaches themselves.

Similar to individual school leaders, considerable diversity was observed among school teams. The challenge of motivating these teams frequently arose, with several process coaches highlighting that school leaders viewed this as their most significant hurdle. In recent years, school teams faced numerous challenges: teacher shortages, the COVID-19 pandemic, visits from the education inspectorate, and curriculum changes. As a result, school leaders worry that their teams will perceive the implementation of SRL as an additional burden. Additionally, in almost all participating schools, SRL implementation is just one of many priorities.

At the start of the second year, several coaches reflected on the emerging disparities between school leaders and their teams. Participation in the PLC had enabled many school leaders to make significant progress and to master a substantial amount of knowledge. As a result, some leaders then expected teachers to quickly implement these changes, which led to a lack of support and more top-down decision-making. Notably, some PLCs used these concerns as a starting point for group reflection, while other process coaches focused only on acknowledging these challenges.

Throughout all the focus group discussions, various approaches were examined, revealing several key insights. School leaders recognized that teachers must also follow a similar learning process, documenting their own challenges to better support their teams. In other PLCs, leaders critically examined the theory of SRL and decided to present it differently to their teams. They started by acknowledging what teachers were already doing in their classroom and briefly connecting it to the theory, helping teachers realize they are already fostering students' SRL skills. These reflections and connections were then collaboratively explored within the PLC, where practical examples were identified and integrated into the discussion.

6 Discussion

In what follows, we elaborate on the results from the focus group discussions with the process coaches. Throughout the discussion, we address the study's limitations, explore potential directions for future research, and present the practical implications of this study for SRL implementation and further professionalization of schools on SRL with process coaches.

6.1 Four roles of a process coach

This study is an added value to prior research studying leadership and roles within a PLC (e.g., Coenen et al., 2021; Margalef and Roblin, 2016) by including between-schools PLCs with school leaders focusing on the school-wide implementation of SRL. While the roles process coaches can assume in this professionalization program were not explicitly questioned in the focus group discussions, three key results regarding these roles emerged.

First, in line with prior research (e.g., Coenen et al., 2021; Prenger et al., 2017), the distinction between the roles of the process coach as a coach, an expert and a coordinator can also be made in this study. Similar to the research of Coenen et al. (2021), the coaching role is most prominent in our study. More specifically, coaches highlight encouraging reflection among school leaders as their main task. Next, goal setting for the PLC occurs only at the beginning of the professionalization trajectory and providing feedback as a coach is rarely addressed. Most coaches recognize their role as an expert and the importance of acquiring sufficient CK-SRL to effectively guide school leaders in implementing SRL school-wide. Acquiring this knowledge requires process coaches to actively study and familiarize themselves with the theoretical frameworks on SRL. This finding contradicts the study by Assen and Otting (2022), which suggests that process coaches often disregard theory as a learning resource. At the same time, it is consistent with the recent study by Vekeman et al. (2023), where participants emphasize the importance of process coaches using their subject matter expertise to provide concrete examples and suggestions tailored to the needs of school leaders. We also observe significant differences among coaches, not only in the importance they attach to CK-SRL but also in the attention they give to PCK-SRL. The latter is mentioned far less frequently, despite Karlen et al. (2020) emphasizing the importance of both types of knowledge. Moreover, differences apparent not only in the knowledge of the process coaches but also their self-efficacy beliefs as experts. Some coaches explicitly reflect on their own feelings of competency and acknowledge their uncertainty in guiding the PLC due to their (limited) knowledge on SRL implementation. Here we observe a parallel with studies on teachers' competencies and more specific teachers' self-efficacy in implementing SRL, which refers to teachers' personal beliefs about their abilities to foster SRL in the classroom (De Smul et al., 2018). It is plausible that similar self-efficacy beliefs among coaches may influence this first phase of SRL implementation, namely the PLCs with the school leaders. Research specifically targeting the general and self-efficacy beliefs of coaches regarding the implementation of SRL is needed in this regard. Lastly, regarding the coordinator role, we observe that process coaches give it less explicit attention. When they do address it, it is mostly at the program's outset, which aligns with the findings of Margalef and Roblin (2016).

Second, we elaborate on the additional, fourth role that became apparent through the data, namely the process coach as a learner. This role influences how coaches assume their responsibilities as both coach and expert. However, significant differences among process coaches are noticed. Notably, those who emphasize their role as experts also strongly focus on their own learning process. Seeing themselves as a learner (e.g., by studying SRL theoretical frameworks, needing reflection time and sharing experiences, approaches, and materials with colleagues) or more specifically as a self-regulated learner could be a strength of this professionalization program. Similar to the research of Karlen et al. (2020), which highlights that teachers are not only agents of SRL but also learners of SRL, this perspective can be extended to actors at the supra-school level, who must first develop their own understanding of SRL before effectively supporting schools and teachers in its implementation. Although the process coaches in this study align their own learning process with that of the school leaders, this contradicts previous research, such as the study by Assen and Otting (2022), where coaches did not view studying theory as a source of learning.

Third, tensions arise between the various roles of the process coaches, particularly between their roles as expert and learner, as some seek to balance learning with school leaders while maintaining their position as knowledgeable experts. Additionally, tension is often felt between their roles as expert and coach. On the one hand, they act as experts, providing theoretical input to school leaders. In this way, they take on a more prominent leadership role, which aligns with previous research that emphasizes the importance of leadership within a PLC (Coenen et al., 2021; Margalef and Roblin, 2016; Tanghe and Schelfhout, 2023). On the other hand, they serve as coaches, fostering reflection, encouraging participation, and building on the group's existing knowledge, which aligns with a core characteristic of PLCs, namely stimulating reflective dialogue (Stoll et al., 2006). Furthermore, some coaches experience tensions regarding their role as coaches during the first year of the professionalization program, especially when a coordinating school leader, also a PLC participant, assumed this role. As mentioned, previous research underscores the critical role of leadership within a PLC (Margalef and Roblin, 2016; Coenen et al., 2021; Prenger et al., 2017; Tanghe and Schelfhout, 2023). However, more research is needed to determine who specifically should take on this role.

In summary, we observed process coaches assuming four roles: coach, learner, expert, and coordinator. However, these roles are not always distinct in practice, and the coaches experience significant tension between them, which impacts their trajectory within the PLC with school leaders.

6.2 Challenges at different levels

In addition to their own role and the challenges experienced by the process coaches, the focus group discussions also address challenges at other levels. Three key levels are discussed below.

At the PLC level, we find, similar to the study by Coenen et al. (2021), that different PLC setups lead to varying process coaching behaviors. In general, process coaches focus primarily on stimulating reflective dialogue, a key characteristic of a PLC (Stoll et al., 2006). However, this is not always straightforward to achieve. Some groups of school leaders are used to working together but mainly exchange ideas and materials, without developing collective responsibility or a shared vision on SRL. As a result, these coaches initially focus more on “collective responsibility” within the PLC, which they find challenging. Moreover, as the PLCs progress, deprivatized practices and shared responsibility are discussed less frequently in the focus groups. This finding raises the question of how well the PLCs in this trajectory align with these fundamental criteria.

At the level of the individual school leader, the process coaches observe a range of motivations among school leaders for participating in the PLC. While some participate out of obligation, others have already been working on SRL for years and are looking for ways to deepen their understanding. This diversity of motivation represents a professional boundary that becomes even more significant for within-school PLCs, where participants come from different school cultures, resulting in varying reasons for participation (Prenger et al., 2019). The variety of motivations in this study is further complicated by variations in prior knowledge of SRL, leadership experience, personal SRL skills and size of the school. Moreover, the uncertainty among school leaders is frequently highlighted as an obstacle by the process coaches. Some school leaders do not perceive themselves as coaches for their staff, fearing that the implementation of SRL would be overwhelming and time-consuming for their teams and indicating that their teams were not innovation-oriented.

Finally, although process coaches do not directly engage with teaching staff in this professionalization trajectory, numerous challenges at this level emerge in the focus group discussions, either are reported by school leaders or are identified by coaches. A common issue is motivating school teams to implement SRL, with several coaches noting that school leaders view this as their main challenge. Some coaches observed a growing gap between school leaders and their teams. As school leaders advanced in the PLC and gained knowledge, some expected rapid changes, raising concerns about limited support and top-down decisions. This challenge underscores the necessity of accommodating different paces of progress when implementing SRL across the entire school. Schools may require tailored approaches that consider the varying levels of readiness, experience, and engagement among team members.

6.3 Practical implications of the study

Firstly, since process coaches perceive themselves as learners and some experience uncertainty, it is essential to provide professional development for those guiding the schools in the school-wide implementation of SRL. Here, a long-term professional development program seems to be more recommended than short-term, standalone initiatives (Prenger et al., 2019). The process coaches need sufficient time to study and to reflect on the challenges they face before and during the collaboration with school leaders. A critical consideration in this regard is the significant time investment required. Since the school-wide implementation of SRL is highly complex, it demands time not only at the school level but also at a broader, meta-level, particularly for the coaches supporting the process. Moreover, the learning process of these coaches is emblematic of the learning that occurs at subsequent levels, including school leaders and teachers.

Secondly, with regard to the challenges faced by process coaches at the level of school leaders, it is crucial to focus on and give attention to their knowledge, as well as their beliefs and self-efficacy, in order to reduce their sense of uncertainty. Similar to teachers, school leaders can be viewed both as agents and as learners of SRL (Karlen et al., 2020). In future PLCs, these aspects can be addressed not only by fostering reflection among participants but also by providing theoretical frameworks, sharing concrete strategies and materials for SRL implementation, and encouraging collaborative learning. Creating a safe and supportive environment where school leaders can openly discuss their uncertainties and exchange experiences is important to strengthen their self-efficacy and enhance their understanding of SRL.

Finally, as the entire school community must work together to implement SRL school-wide (Peeters et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020), there is a need for supportive conditions at all levels, such as adequate time and space for reflection. To achieve changes in students' SRL skills, we must start by supporting process coaches who guide schools, thereby gradually moving toward the implementation of effective classroom practices.

6.4 Limitations and suggestions for future research

We conclude with additional research suggestions in addition to the ones already referred to, while also acknowledging the limits of the current study.

Firstly, although this professionalization trajectory is not a short-term professional development initiative but a long-term trajectory, which allows for deeper and more sustainable growth (Watson, 2014), it also presents a challenge: the inevitable turnover of participants throughout the learning process. This is a limitation, as continuity in guidance is not always guaranteed. Moreover, these changes do not only occur at the school level, affecting school leaders and teachers, but also among the process coaches who support the schools. This turnover highlights a key issue in the broader discourse on education quality: strengthening and professionalizing teachers is difficult when coaches with accumulated experience are replaced, forcing new coaches to start from scratch.

Although this study adopts a two-year longitudinal approach, further research is needed to examine how the process continues beyond this period. Learning at various levels requires time, and therefore, research should also extend over a longer duration. Additionally, as previously mentioned, turnover presents a challenge, causing delays in the process. Turnover at the level of the process coaches is emblematic of similar changes occurring at subsequent levels, including school leaders and the school team. Moreover, although rich longitudinal qualitative data were collected through frequent focus groups with process coaches, the current analysis did not systematically explore changes over time in key constructs such as coaches' expectations, knowledge, beliefs or self-efficacy. Because the focus group protocols evolved to match the coaches' developing needs and each session was analyzed independently, it was not possible to track developmental patterns throughout the program. Future research could use a longitudinal mixed-methods design to better understand how process coaches develop in their role and how this affects coaching outcomes.

Thirdly, although the data were analyzed systematically, one methodological limitation is that the coding process was not double-checked by a second coder. As a result, interrater reliability was not formally assessed, which may affect the dependability of the findings.

Fourthly, this study only considers the perspective of process coaches. While this focus is a key strength, as process coaches play a critical role in guiding school leaders and teams through the stages of SRL implementation, future research should explore how PLC members perceive the coaches' role and how their perspectives align or differ from those of the coaches.

Finally, while this study's exploratory approach offers an in-depth, insider perspective of process coaches in SRL-focused professionalization programs, its findings cannot be broadly generalized. Future research should examine whether the roles, patterns and challenges observed here are also present in other contexts. This could ultimately contribute to the development of a research-based framework for comprehending the coaching processes within PLCs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of Ghent University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HV: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to suggest improvements for clearer and more effective wording of the results and discussion.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acton, K. (2021). School leaders as change agents: do principals have the tools they need? Manag. Educ. 35, 43–51. doi: 10.1177/0892020620927415

Assen, J., and Otting, H. (2022). Teachers' collective learning: To what extent do facilitators stimulate the use of social context, theory, and practice as sources for learning? Teach. Teach. Educ. 114:103831. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103702

Barr, S., and Askell-Williams, H. (2020). Upgrading Professional Learning Communities to Enhance Teachers' Epistemic Reflexivity About Self-regulated Learning. In Teacher Education in Globalised Times. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-4124-7_19

Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-regulated learning: where we are today. Int. J. Educ. Res. 31, 445–457. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00014-2

Bolhuis, S., and Voeten, M. (2001). Toward self-directed learning in secondary schools: What do teachers do? Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 837–855. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00034-8

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bryk, A. S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement. Phi Delta Kappan 91, 23–30. doi: 10.1177/003172171009100705

Chapman, C., and Muijs, D. (2014). Does school school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improve. 25, 351–393. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2013.840319

Christensen, A., and Jerrim, J. (2025). Professional learning communities and teacher outcomes. A cross-national analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 156:104920. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104920

Coenen, L., Schelfhout, W., and Hondeghem, A. (2021). Networked professional learning communities as means to flemish secondary school leaders' professional learning and well-being. Educ. Sci. 11:509. doi: 10.3390/educsci11090509

Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., and Dochy, F. (2019). A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educ. Res. Rev. 27, 110–125. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2019.02.003

Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., and Heystek, J. (2023). Developing school leaders: Responses of school leaders to group reflective learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 49, 135–149. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1766543

Day, C., Gu, Q., and Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: how successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Admin. Q. 52, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15616863

De Smul, M., Heirweg, S., Devos, G., and Van Keer, H. (2020). It's not only about the teacher! A qualitative study into the role of school climate in primary schools' implementation of self-regulated learning. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 31, 381–404. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2019.1672758

De Smul, M., Heirweg, S., Van Keer, H., Devos, G., and Vandevelde, S. (2018). How competent do teachers feel instructing self-regulated learning strategies? Development a validation of the teacher self-efficacy scale to implement self-regulated learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 71, 214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.001

Dent, A., and Koenka, A. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 425–474. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning 3, 231–264. doi: 10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2018). Teachers' direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes – insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacogn. Learn. 13, 127–157. doi: 10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x

Dignath-van Ewijk, C. (2016). Which components of teacher competence determine whether teachers enhance self-regulated learning? Predicting teachers ' self-reported promotion of self-regulated learning by means of teacher beliefs, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Fron. Learn. Res. 4, 83–105. doi: 10.14786/flr.v4i5.247

Donker, A., de Boer, H., Kostons, D., Dignath-van Ewijk, C., and van der Werf, M. (2014). Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: a meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 11, 1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.002

Duby, D. (2006). How Leaders Support Teachers to Facilitate Self-Regulated Learning in Learning Organizations: A Multiple-Case Study.

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educ. Psychol. 46, 6–25. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.538645

Elhusseini, S., Tischner, C., Aspiranti, K., and Fedewa, A. (2022). A quantitative review of the effects of self-regulation interventions on primary and secondary student academic achievement. Metacogn. Learn. 17, 1117–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11409-022-09311-0

Goldring, E., Preston, C., and Huff, J. (2012). Conceptualizing and evaluating professional development for school leaders. Plann. Chang. 43, 223–242.

Grissom, J., Mitani, H., and Woo, D. (2019). Principal preparation programs and principal outcomes. Educ. Admin. Quart. 55, 73–115. doi: 10.1177/0013161X18785865

Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Camb. J. Educ. 33, 329–351. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000122005

Hallinger, P. (2010). Developing Successful Leadership. In Developing Successful Leadership. Newyork: Springer (61–76). doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9106-2_5

Hilden, K., and Pressley, M. (2007). Self-regulation through transactional strategies instruction. Read. Writ. Quart. 23, 51–75. doi: 10.1080/10573560600837651

Honig, M. I., and Rainey, L. R. (2014). Central office leadership in principal professional learning communities: the practice beneath the policy. Teach. Coll. Rec. 116:48.

Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L., and Mackay, T. (2014). School and system improvement: a narrative state-of-the-art review. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 25, 257–281. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

James, M., Black, P., Carmichael, P., Conner, C., Dudley, P., Fox, A., et al. (2006a). Learning how to learn: tools for schools. Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203967171

James, M., Black, P., McCormick, R., Pedder, D., and Wiliam, D. (2006b). Learning how to learn, in classrooms, schools and networks: aims, design and analysis. Res. Papers Educ. 21, 101–118. doi: 10.1080/02671520600615547

James, M., and McCormick, R. (2009). Teachers learning how to learn. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.023

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., and Hirt, C. N. (2020). Teachers' professional competences in self-regulated learning: An approach to integrate teachers' competences as self-regulated learners and as agents of self-regulated learning in a holistic manner. Front. Educ. 5, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00159

Kistner, S., Rakoczy, K., Otto, B., Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Büttner, G., and Klieme, E. (2010). Promotion of self-regulated learning in classrooms: Investigating frequency, quality, and consequences for student performance. Metacogn. Learn. 5, 157–171. doi: 10.1007/s11409-010-9055-3

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 17, 201–227. doi: 10.1080/09243450600565829

Lomos, C., Hofman, R., and Bosker, R. (2011). Professional communities and student achievement - a meta-analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 22, 121–148. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2010.550467

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). Managing change: the role of the change agent. Int. J. Bus. Adm. Manag. Res. 13, 1–6.

Margalef, L., and Roblin, N. (2016). Unpacking the roles of the facilitator in higher education professional learning communities. Educ. Res. Eval. 22, 155–172. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2016.1247722

Miles, B., and Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morgan, D., Krueger, R., and King, J. (1998). The Focus Group Guidbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781483328164

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., and Earl, L. (2014). State of the art - teacher effectiveness and professional learning. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 25, 231–256. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

Ni, Y., Rorrer, A., Pounder, D., Young, M., and Korach, S. (2019). Leadership matters: preparation program quality and learning outcomes. J. Educ. Admin. 57, 185–206. doi: 10.1108/JEA-05-2018-0093

Peeters, J., De Backer, F., Reina, V., Kindekens, A., Buffel, T., and Lombaerts, K. (2014). The role of teachers' self-regulatory capacities in the implementation of self-regulated learning practices. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 116, 1963–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.504

Prenger, R., Poortman, C., and Handelzalts, A. (2017). Factors influencing teachers' professional development in networked professional learning communities. Teach. Teach. Educ. 68, 77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.014

Prenger, R., Poortman, C., and Handelzalts, A. (2019). The effects of networked professional learning communities. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 441–452. doi: 10.1177/0022487117753574

Schelfhout, W., Bruggeman, K., and Bruynickx, M. (2015). Vakdidactische leergemeenschappen, een antwoord op professionaliseringsbehoeften bij leraren voortgezet onderwijs? Tijdschrift Voor Lerarenopleiders 36.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., and Thomas, S. (2006). Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature. J. Educ. Change 7, 221–258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Tanghe, E., and Schelfhout, W. (2023). Professionalization pathways for school leaders examined: the influence of organizational and didactic factors and their interplay on triggering concrete actions in school development. Educ. Sci. 13:614. doi: 10.3390/educsci13060614

Thomas, G. (2011). A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qual. Inq. 17, 511–521. doi: 10.1177/1077800411409884

Thomas, V., Peeters, J., De Backer, F., and Lombaerts, K. (2020). Determinants of self-regulated learning practices in elementary education: a multilevel approach. Educ. Stud. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1745624

Thoonen, E., Sleegers, P., Oort, F., and Peetsma, T. (2012). Building school-wide capacity for improvement: the role of leadership, school organizational conditions, and teacher factors. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 23, 441–460. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2012.678867

Tingle, E., Corrales, A., and Peters, M. (2019). Leadership development programs: investing in school principals. Educ. Stud. 45, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2017.1382332

Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., and Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: a systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.001

Vekeman, E., Devos, G., and Tuytens, M. (2023). Wetenschappelijke opvolging van professionaliseringstrajecten met het oog op het versterken van leiderschap voor herstel en veerkracht in het onderwijs. OandO-opdracht in opdracht van het Departement Onderwijs and Vorming. Onderzoeksgroep BELLON, Universiteit Gent.

Wahlstrom, K., and Louis, K. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: the roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educ. Admin. Quart. 44, 458–495. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321502

Watson, C. (2014). Effective professional learning communities? The possibilities for teachers as agents of change in schools. Br. Educ. Res. J. 40, 18–29. doi: 10.1002/berj.3025

Keywords: self-regulated learning, school-wide implementation, professional learning communities, school leaders, process coaches

Citation: Backers L and Van Keer H (2025) Professionalizing schools on self-regulated learning: roles, responsibilities and challenges of process coaches. Front. Educ. 10:1601822. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1601822

Received: 28 March 2025; Accepted: 10 June 2025;

Published: 08 July 2025.

Edited by:

Slavica Šimić Šašić, University of Zadar, CroatiaReviewed by:

Linda Bol, Old Dominion University, United StatesIzabela Sorić, University of Zadar, Croatia

Copyright © 2025 Backers and Van Keer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lies Backers, bGllcy5iYWNrZXJzQHVnZW50LmJl

Lies Backers

Lies Backers Hilde Van Keer

Hilde Van Keer