- 1Department of Psychology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa

- 2Tara The H Moross Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

In most African societies, particularly among Black people, names are central to people’s identity and are central to how young people develop a sense of self. In the post-colonial-apartheid context of South Africa, which we argue is largely governed by white cultural hegemony, the occurrence of varying subtle forms of racism is inevitable. Name-based microaggressions are one defining feature of the post-colonial-apartheid white cultural hegemonic context, specifically within educational contexts. In this article, we illustrate how white cultural hegemony gives rise to name-based microaggressions, perpetuated towards Black youth in the South African educational context, mostly by educators. We conducted eight (8) semi-structured interviews with Black youths based in a South African university, who had experiences of name-based microaggressions. The interviews were analysed using Thematic Analysis, yielding three (3) themes: name mispronunciations and Black names as an inconvenience, name-based microaggressions in the educational context, and the effects of name-based microaggressions. We conclude by showing how name-based microaggressions can have deleterious effects on the identity development of youths who are victims, affecting the ways in which they view themselves in relation to their culture, as well as the relationship they have with peers and educators. This article highlights the need for inclusive educational environments that honour students’ identities to avoid the perpetuation of racism in the educational context, and the associated effects of the occurrence of name-based microaggressions within the education space.

Introduction

The 2024 election in the United States of America (USA) brought to the fore several issues related to how racism, within a global white cultural hegemony, can manifest in various ways—least of which is what Srinivasan (2019) has termed name-based microaggressions. Name-based microaggressions are subtle, sometimes unconscious, and often disguised as unintentional mispronunciations, kin-enhancing renaming of the racialised other (see Kohli and Solórzano, 2012). In many instances, this racialised Other is the Black object of the (white) colonial gaze (see Musila, 2017). Kamala Harris, who was the presidential candidate in the USA, endured mispronunciations of her name, which was often positioned by the perpetrators as unintentional, but in other instances intentionally done to—as Manganyi (1984) argued of racism—‘make strange’. This mispronunciation of Kamala’s name is not necessarily new within the USA, but it is also not a phenomenon that is particularly unique to that context. By and large, the mispronunciation of Black people’s names is an entrenched practice of colonial misrecognition that exists in most, if not all, places where there has been colonial rule (see Srinivasan, 2019).

The practice of renaming people has a long history, particularly in places where colonisation accompanied by slavery, has existed. For instance, during slavery, many Black slaves who were brought into America were renamed by their white slave owners (Inscoe, 1983). This practice was true across the slave owning world, wherein slaves were renamed to reflect their masters’ culture, or as Hawthorne et al. (2025, p.1) explicated, “[t]he power to name is the power to claim, which is why naming and renaming practices seem central to enslaved people and their descendants.” The renaming practices during slavery do not merely reflect a practice of ease of recognition but rather were driven by an attempt at forced assimilation and indoctrination with Western-colonial culture.

In contemporary times, the practice of renaming has morphed into name-based microaggressions through mispronunciations, nicknaming or through Black people being given Christian—read white—names, which has been historically prevalent in the colonised world (Cakata and Ramose, 2021). In South Africa, there are many examples, perhaps for most South Africans even commonplace, of instances of renaming and mispronunciation of Black names dating back to slavery—see example of Kroata (Conradie, 1997). As is with the example of Kroata, because of the enmeshed relationship between colonial rule and Christianity, the church and missionary schools appear to be central in this practice. Famous examples of racialised renaming include struggle heroes against colonialism and apartheid, who were renamed as they entered the missionary school system, either for the convenience of the white teachers or simply because their names were deemed inadequate (de Klerk and Lagonikos, 2014). The most popular example of being renamed, is the global icon Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (Soudien et al., 2014), who was not named Nelson until he entered missionary school, and Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu, the anti-apartheid and women’s rights activist, who chose the name Albertina from a list of names as she entered school (van Niekerk and Freedman, 2023).

The renaming of Black children and the mispronunciation of Black names is linked to the infra-humanising of African indigenous languages and cultures, which continues to maintain white dominance. This is particularly conspicuous within education, both basic and higher, as Dlamini (2024, 2020) maintained that language remains a central component of how Black people are continuously marginalised within disciplines such as Psychology. In the larger South African context, Cakata and Ramose (2021) maintained that the de-languaging of Africans was perpetuated within “[c]hurch and schools [which] were instrumental in this replacement by demanding that indigenous children should have, what they labelled, Christian names. This took away the right of parents to name their children according to their cultural norms” (p. 488).

In post-colonial societies such as South Africa, where churches, schools, and government cannot demand that a child be given a white Christian name, the remnants of colonial practices persist today. While during colonialism and apartheid the practice was to have a second name, such as Nelson, the present-day practices can be seen in what Cakata and Ramose (2021, p.488) identified as Black names assuming a Christian characteristic “such as Nkosikhona (which is a translation of the name Emmanuel) and Nolufefe (a translation of the name Grace)”. Ngubane and Thabethe (2013) attested that naming practices are heavily influenced by socio-political factors, with changes in personal naming practices often reflecting these macro-structural factors, rather than personal culture. Here, we are not meaning to show the problems of the adoption of Christian names. Rather, what is pertinent to this article is the occurrence of nicknaming, renaming, and mispronunciations of Black names that appear to be commonplace, and their consequential experiences of microaggressions. These forms of name-based microaggressions, appear to be influenced by the intransigence of white cultural hegemony, which Dlamini (2024, p. 5) explained as being when “whiteness is the standard to which Black [people] tacitly consent and through which those who enter the [education system] become integrated. The consent is often cajoled, coerced and at times “freely” given, without regard for whether this has a negative impact in society.” White culturally hegemonic societies resemble in many ways their colonial predecessors in that they, consciously or otherwise, tend ‘other’ culture s that do not fit into the dominant forms of whiteness.

Microaggressions in general are a form of racism, as with more overt forms of racism, often have negative effects on the recipient (Nepton et al., 2025). The cumulative effect of the onslaught of subtle and overt racism may result in trauma for recipients of racism (Canham, 2018; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019; Sue et al., 2007). The experience of racism over time serves an “othering” function by white hegemonic structures in society, communicating that the recipient does not belong (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012). Racism and Name-Based Microaggressions (NBMs), in turn, have a delerious effect on cohesive identity development and self-esteem (Canham, 2018; Kim and Lee, 2011; Nadal et al., 2014a; Nadal et al., 2014b; Srinivasan, 2019; Sue et al., 2007). Furthermore, this may impact self-concept and acceptance of oneself and one’s culture within the social world, further negatively impacting self-esteem and creating feelings of exclusion (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Nadal et al., 2014b; Ponds, 2013).

The experience of racism has been found to have significant negative impacts on physical health, with recipients of racism reported to show higher risk for medical conditions such as hypertension, various cancers, and cardiovascular disease, due to the associated stress of the experience of racism (Moomal et al., 2009; Pieterse and Carter, 2010; Srinivasan, 2019). Higher associations between the experience of racism and substance use disorders have also been found (Nadal et al., 2014a, 2014b; Ponds, 2013; Srinivasan, 2019). Similarly, the experience of racism and microaggressions has been found to increase the risk for psychiatric disorders and symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Canham, 2018; Nadal et al., 2014a, 2014b; Pieterse and Carter, 2010; Srinivasan, 2019). Finally, the experience of racism may result in trauma-related symptoms, which may increase feelings of distress, helplessness, and hopelessness (Ponds, 2013; Srinivasan, 2019).

In this article, we intend to elucidate the relationship between white cultural hegemony and name-based microaggressions within contemporary South African society. We specifically aim to illustrate how the occurrence of name-based microaggressions within educational institutions is a function of white cultural hegemony. We characterise white cultural hegemony within an understanding of an anti-Black world, which Gordon (1995) argued as being a world in which white people are considered superior and therefore whiteness is considered self-justified. That is to say that mispronunciations, nicknaming, and indeed renaming of Black people within hegemonically white education spaces is normalised, regardless of the impact on the person. We primarily focus on how young people who have experienced name-based microaggressions are alienated from themselves and their environment, and the implications of this alienation on their educational and social development.

Name-based microaggressions and white cultural hegemony

The present study is located within the analysis made by Gramsci (1971) on cultural hegemony, in which one group comes to dominate another, not through force but rather through subtle everyday domination, which makes one group normative or standard (Dlamini, 2024). In the context of South Africa—and perhaps other parts of the world—cultural hegemony should be seen in its racialised sense as white cultural hegemony. That is, it is not merely a hegemony of one culture over another/s, but rather it is the systematic dominance of whiteness created through colonialism and apartheid and reinforced in contemporary transformation failures.

These failures to transform South African society, which are fundamentally underscored by rampant corruption at all levels of government (de Man, 2022), have had a detrimental effect on the education sector. Epistemological transformation at the level of the curriculum has been slow, including the adaptation of multilingualism, and other issues inherent in the education sector, such as under-resourced schools and overcrowded classrooms (Mzileni and Mkhize, 2019; Mlachila and Moeletsi, 2019). These issues contribute to the continued white cultural hegemony that leads to former whites-only schools being seen as better (Hiss and Peck, 2020), maintaining the idea of whiteness as an aspirational standard.

White cultural hegemony, as Dlamini (2025, p.127) argued, explains how, in particular, Black people’s “traditions, customs, and the like – are regarded as merely to be tolerated rather than embraced.” This “tolerance” of Black people reinforces the notion that the public domain is reserved for whites, that Black people have an illicit appearance—a denial of the right to appear—that renders their hypervisibility as invisibility (Gordon, 2012). White cultural hegemony can thus be seen in the realm of everyday life, in the interactions of people, rather than only in the major political events that often capture headlines. This way of understanding the operation of whiteness is not unlike the ways in which scholars of Critical Race Theory (CRT) have illustrated the occurrence of racism, which is itself partly based on the work of Gramsci (Stefancic and Delgado, 2011). In this way, white cultural hegemony sits alongside other work that attempts to explicate the ways in which racialised dominance occurs in post-colonial societies. We choose to frame the research within white cultural hegemony, as it offers a way to see the post-colonial world as fundamentally governed through whiteness, or in simpler terms, whiteness is standardised.

The world of white cultural hegemony should then be understood as an anti-Black world. Gordon’s (1995) analysis of Blackness as it exists in an anti-Black world is particularly apt in understanding, first, the persistence of white cultural hegemony and then, second, the occurrence of name-based microaggressions. Taking the first instance of an anti-Black world and white cultural hegemony, the former should be regarded as a world that necessarily considers all things—culture, language, tradition, and indeed physical appearance—that constitute Black lifeworlds as undesirable. An anti-Black world marks the Black lifeworld as something that exists only as a negation of whiteness—white as always necessarily superior and thus can judge what is deemed acceptable (see Fanon, 1967; Ahmed, 2002). During the colonial encounter, this dichotomy between white and Black was pronounced in all areas of life including where people could live (The Natives (Urban Areas) Act No. 21 of 1923, n.d.); who they could marry (The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, Act No. 55 of 1949, n.d.); and where they could go to school (Bantu Education Act No. 47 of 1953, n.d.).

In contemporary post-colonial societies, the markings of white supremacy are often less pronounced, occurring in subtle, taken-for-granted, everyday interactions in society, including educational institutions. Dlamini (2024) illustrated, for example, how in South African higher education, the lingua franca is English even though for the majority of South Africans, English is a second or third language. The status of English within education institutions is not something that occurs by chance but rather is a function of the devaluing of African indigenous languages, as un-evolving and not fit for academic purposes (Nkosi, 2014; Kamwendo, 2010; Segalo and Cakata, 2017). In line with this argument, we contend that the promotion of English as the language of everyday life is due in large part to white cultural hegemony with its historical roots in colonialism and apartheid, which sought to eradicate Black lifeworlds and instil whiteness as standard. We argue that this way of life, marked and defined by white cultural hegemony, in post-colonial societies such as South Africa, is inherently anti-Black and white supremist.

Leading from the relationship between an anti-Black world and white cultural hegemony, the second of our points on the occurrence of name-based microaggressions within South African education is imminent. As Oyěwùmí and Girma (2023, p.3) noted, “[i]t is axiomatic that we all have names […] Names are interwoven with the languages, cultures, histories and religions from which they emanate.” However, it remains that for Black people in the colonised encounter, that is in the interaction with whiteness, they seize to have a culture, a language, a religion, and indeed a name. The assumption of whiteness as it manifests in its hegemonic sense is such that Black people—or the Black children—are invariably objects to be shaped in a lesser image of itself, thus open to be renamed, nicknamed, or mispronounced. The occurrence of name-based microaggressions within educational institutions, between those teachers racialised as white and students racialised as Black, is predicated on this historically constituted assumption.

The South African educational system remains a mirror of the colonial and apartheid systems that underdeveloped education for Black people, while reserving resources for schools designated for white people (Spaull, 2013). The segregationist policies of apartheid created a situation in which many schools in historically Black-only areas have been overcrowded and under-resourced, with many schools in rural—and urban townships—areas struggling with necessities such as water, electricity and sanitation (Mouton et al., 2013). This has meant that for many Black people, who can afford it, to attain the best education for their children, they have had to put their children in what is popularly known as ‘model-c schools’, a term used to describe former whites-only schools (Lombard, 2007).

It is within these historical and contemporary factors that lead to the occurrence of name-based microaggressions. An increased number of Black students have entered former white-only schools, taught by white educators, many of whom do not speak African indigenous languages, thus do not know how to pronounce Black names. The realisation of the so-called rainbow nation has not been attained with both economic inequality (Sulla and Zikhali, 2018) but perhaps it is no more evident than in the ways in which “despite the efforts of building a country that is characterized by unity, and collective understanding of nation-building – aptly called the ‘rainbow nation’ – South Africa’s racialized inequality has reinforced the colonial-apartheid structures” (Dlamini, 2025, p.123). In the latter, what we may be observing is how, for the majority of white South Africans, there is simply no need to learn African indigenous languages, thus African indigenous names. The occurrence of name-based microaggressions is within a context of white cultural hegemony, where consent is manufactured through historical structures and contemporary necessities.

We argue that the occurrence of name-based microaggressions in educational institutions in South Africa signals to those students racialised as Black two fundamental ideas about an anti-Black white culturally hegemonic world. First, name-based microaggressions by their very nature disregard the significance of names, within African cultures, rendering the cultural, tribal, and indeed familial meanings that are often imbued within names as also insignificant. Oyěwùmí and Girma (2023, p.2) concede that the issue with the disregard of names as something that is important to African people can be understood within the white Western notion that “names in and of themselves do not hold much worth or meaning beyond their function as labels to distinguish people, places, or things from one another.” In many African communities, certainly within Black communities in South Africa, naming practices do not simply signify a label but rather speak to significant familial, cultural, tribal, ancestral, and religious meanings (Mkhize and Muthuki, 2019). The importance of names is not only within Black or African cultures but can also be found among Asian communities (Kim and Lee, 2011) as well as among people of Indian descent (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012), illustrating how, for the majority world, names are more than just labels.

Secondly, naming practices often denote belonging. In the main, microaggressions of any kind can serve to communicate to the recipient that they do not belong, whether within corporate environments (Mokoena, 2020) or within educational contexts (Canham, 2018). The mispronunciations, renaming, and nicknaming as manifestations of name-based microaggressions also communicate to the recipient their non-belonging (Emmelhainz, 2012). Inversely, names serve to illustrate familial and tribal belonging, thus serving as an important indicator of the proximal and distal relationships between themselves and others (Mkhize and Muthuki, 2019; Oyěwùmí and Girma, 2023). Names are thus not just symbolic labels that hold meaning to the person or their family, but rather stretch out to society to communicate various things; to be named, is to belong.

We took seriously the everyday interactions within educational institutions to illuminate the experiences and effects of name-based microaggressions of Black youth in South Africa. We place the occurrence of name-based microaggressions within white cultural hegemony because of the historical and contemporary factors in South Africa.

Method

In the study, we aimed to illustrate the occurrence of name-based microaggressions in educational institutions, positing that these occurrences of name-based microaggressions are mainly a function of white cultural hegemony, which positions Black lifeworlds as undesirable. Towards this end, the study employed a qualitative descriptive design, which focuses on ensuring that participants’ descriptions of a real-world experience of an issue are captured as closely as possible (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010). In the current study, the focus was on how participants described their experiences of name-based microaggressions as occurring within the education system in South Africa, taking into consideration the dominant cultural problematic occurrence of whiteness in both education and wider South African society.

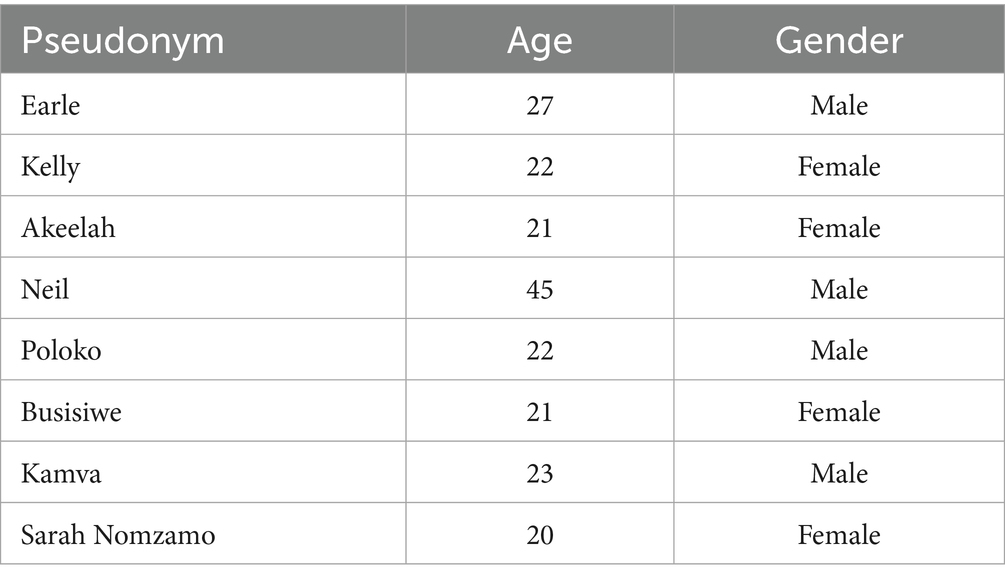

In line with the qualitative design of the study, data were collected with eight (8) Black students at a university in South Africa, who responded to an advertisement on the university’s message board. Those people who responded to the advertisement were required to meet the following criteria: should have been 18 years or older at the time of the interviews, should have experienced name-based microaggressions in a school context, and should identify as Black, as widely defined. Taking into consideration both the importance of maintaining participants’ privacy and confidentiality, as well as not perpetuating name-based microaggressions, the participants were asked to give a pseudonym that can be used in the reporting of the study. The pseudonyms, as well as the gender and ages of the participants, are reported in Table 1.

From the participants, data were collected using a semi-structured interview format. Semi-structured interviews were considered the most appropriate method of data collection as they allowed for deeper exploration of the experiences of name-based microaggressions (see Adams, 2010). Participants were provided with the option to conduct interviews in-person or online on video conferencing platforms. All interviews were conducted online in a private space by the first author, and all participants chose a private venue in which to engage in the online interview. After the interviews were conducted, they were manually transcribed verbatim. Transcribed interviews were de-identified, and participant-chosen pseudonyms were used to protect participant confidentiality.

Data were analysed using Thematic Analysis (TA). TA is a flexible method of qualitative data analysis that systematically identifies, organises, and analyses patterns of meaning or commonalities in data into themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2012). This, in turn, allows for the process of deriving meaning based on the shared experiences of participants. Themes were identified using the steps of TA as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): get acquainted with the data and transcribe the recordings verbatim; create initial codes; sort codes into preliminary themes; review and evaluate themes; define, refine, and name themes; conduct the final analysis; and write the report (Braun and Clarke, 2012).

The study received ethical clearance from the Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee, at the University of Johannesburg, REC-01-071-2021. Participants’ informed consent was obtained through a written information sheet, which was sent to them after responding to the circulated advertisement. To ensure that participants were fully informed about the decision to participate in the study, the information was repeated verbally before the start of the interview. The verbal information provided, as well as the written information sheet, explained that participants could withdraw from participation at any time, that their information would be kept confidential, and that psychological services would be available should they require.

Reflexivity

We offer here the first author’s reflexivity as they initiated the research and had the first encounter with the participants. We offer this reflexivity not to fetishise difference (Malherbe and Dlamini, 2020), but rather to illuminate the ways in which historically shaped encounters can affect the research process. Before proceeding to present the results of the study, it is perhaps important to note an important aspect that affected to some degree the research process. The first author, who was responsible for the data collection, is a white South African female. Who was born in Kwa-Zulu Natal and raised in Johannesburg. Her positionality as a white female means that this research was challenging in a few ways. First, being white means that by association, I am inescapably privileged. I have never been the recipient of racism, and thus I cannot fully understand the subjective reality of what it means to be subjected to overt or covert forms of racism. Second, this meant that I needed to be particularly careful in how I approached the research and the research participants to ensure that my own innate biases, power dynamics, and privilege interfered as little as possible.

There is an argument in the literature on whether white people should engage themselves in research on racism at all. This was a challenge for me as I felt passionate about conducting the research, but I also had, and continue to have, moments of self-doubt about whether conducting this research is an enactment of my whiteness and another form of the colonisation of Black spaces and experiences. Steve Biko argued that white people need to be very careful in their involvement in Black struggles, and instead of directly involving themselves in Black anti-racist struggles, should work within their white society to educate their fellow white counterparts and build awareness of the manifestations of racism (Matthews, 2012).

Taking cognisance of this information, I decided to approach this research from the perspective that I do not intend to speak on behalf of Black people because that would mean taking up a position of power and having the innate belief that Black people cannot speak for themselves. Instead, my research approach aimed to attempt to show, as directly as possible, the everyday experiences of Black research participants in the study using their own direct verbatim quotes. Also took the approach that this research can be used as a means of building awareness within white communities and in predominantly white spaces that I usually inhabit as a white person. Very carefully, I can use critical perspectives to think about the manifestations of race and racism in South African society.

One element of the first author’s whiteness that I think made the research process challenging was navigating how my positionality would affect the comfort of participants in sharing their honest experiences. The presence of a white researcher navigating the topic of race and racism seemed to be an obstacle to complete openness. Although some participants seemed to feel free and comfortable enough to discuss race and racism perpetuated by white people, others appeared to feel uncomfortable with discussing racism, as indicated by one participant asking permission from the researcher to speak about racism. This further conveys the dynamic that the white researcher holds the power in terms of when racism can be spoken about. This also calls to attention the widespread unconscious expectation on the part of white people that Black people are responsible for the management of white feelings. Discussing racism was central to the work of this research, and thus, a lot of care was taken to build rapport with each participant and co-create a safe space for the discussion of potentially sensitive topics such as racism.

Results

Name-based microaggressions are not isolated, harmless mistakes, but are rather complex interactions that must be understood within the broader context of racism through a critical lens. Name-based microaggressions and racialised renaming stem from the tacit belief that white, Anglo, Christian, European or Northern American names are normative, while African, Arabic, Asian, Latin(x) names are inconvenient or unwelcome in white dominated societies (Srinivasan, 2019). White-sounding names are seen to be more desirable in dominant white hegemonic cultures and thus are frequently primed with positive associations.

Racism is deeply ingrained in society that it becomes ordinary and easily overlooked due to its subtle, nuanced, and covert expression (Bock, 2018; Cobb, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 1998; Modiri, 2012; Moorosi, 2020; Pérez Huber and Solorzano, 2015). The white hegemonic structure of society results in white values and expectations being centralised, and Blackness othered, leading to normalisation of whiteness, and by default making anything outside of a white lens seem foreign, different or lesser than (Manganyi, 1984; Liu et al., 2019; Vice, 2010). This notion of whiteness as normative and superior is ever-present in South African society, resulting in Black lifeworlds, including Black names, being viewed as unwanted nuisances (Foster, 1991; Franchi, 2003; Stevens, 1998).

Using Thematic Analysis, the interviews from the participants were analysed, yielding the following themes: name mispronunciations and Black names as an inconvenience, name-based microaggressions in the educational context, and the effects of name-based microaggressions.

Name mispronunciations and black names as an inconvenience

Black/African indigenous names are often positioned as difficult. Earle highlights the challenges of presenting with a perceived ‘difficult’ name at school:

“… it was difficult having the name ‘Earle’, accepting the name was quite difficult… from primary school and whenever teachers would read the register and stuff, kids would laugh at my name and that sort of made it difficult for me to accept it… people are actually surprised at how my name is.” (Earle).

Similarly, another participant recounted an experience whereby her teacher struggled with the pronunciation of her name and resorted to publicly ridiculing her in front of her class. This teacher initially engaged in indirect covert racism, a microaggression, and then moved to more overt racism:

“She was calling everybody with the class list. Then it was my turn to go in and she couldn’t say my name …, “Why does your name have so many [letters] like, I don’t get it.” … “Don’t you have a shorter name?” and I said, “No just say [my name]” and then she pronounced it wrong. But back then, I was unaffected because I got it a lot. I went to like a predominantly white school, so I got that a lot, so I was used to it. But now thinking back … she even made a comment, and she said, “Why do Black people put so many vowels in their name, why do you guys use all the vowels in your name?” And I didn’t have an answer for her back then, ya I didn’t know better.” (Akeelah).

The above accounts elucidate the function of Manganyi’s “making strange,” a process that occurs when whiteness is centralised and normalised in society, and thus elements of Blackness are marginalised and made to be strange (Manganyi, 1984). Consequently, through interactions with dominant white culture, racism and racial microaggressions, Black people are forcibly made aware of their societal position, perpetually navigating and accommodating white hegemonic norms and expectations, a process that renders their own identities ‘strange’ within a white-centric framework. The two extracts from Earle and Akeelah also illustrate that through the process of accommodating elements of the hegemonic white culture whilst allowing for belonging and social survival (Liu et al., 2019), they also have the potential to spawn internalised racism. This may be described as the unconscious acceptance and internalisation of the racial hierarchy of white superiority and Black inferiority, and in turn, an internalisation of the hegemonic values and worldviews of society (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019).

Further analysis of Akeelah’s experience highlights the centralisation of whiteness and the assimilative pressure imposed by white people in positions of authority (i.e., teachers). This is substantiated by Srinivasan (2019), who found that participants experienced that the perpetrator frequently voiced preferences regarding how their own name should be altered, and would assign nicknames or alternative names to participants, assuming it was an acceptable practice as they perceived that it was the participant who had presented with a ‘difficult’ name. In Srinivasan’s study, participants reported that their most difficult interactions regarding their names were with people in positions of authority, such as teachers or employers (Srinivasan, 2019).

While the South African constitution explicitly prohibits discrimination based on race, Modiri (2012) argued that formal institutional changes are not indicative of substantive behavioural changes. Racism may appear different to the nature of offences perpetuated over the last few centuries, but this does not mean that it no longer exists. While racism may be less overt, the work of CRT, and specifically the study of microaggressions, elucidates the reality that racism remains part of the fabric of social interactions (Bock, 2018; Srinivasan, 2019). Over time, as overt racism has been recognised as a social wrong, racially discriminative acts have become more subtle. This is indicated through both systemic racism in societal institutions and through the occurrence of covert racial microaggressions (Bryant-Davis and Ocampo, 2005; Canham, 2018; Jones and Galliher, 2015; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Nadal et al., 2014b; Sue et al., 2007). Covert forms of racism that continually convey a subtle message that Black people do not belong in white dominated spaces are deeply entrenched in societal institutions, making them, at times, unconscious and difficult to identify (Bryant-Davis and Ocampo, 2005; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012).

In her research regarding the occurrence of name-based microaggressions, Srinivasan found that students reported increased feelings of anxiety and dread during new introductions and in roll call in class, and thus often chose to alter the presentation of their name by using a whiter sounding name, nickname, or middle name to avoid presenting as an ‘inconvenience’ or ‘burden’ to others, to avoid possible ridicule, or to feel more comfortable within social interactions (Srinivasan, 2019). Kelly noted that:

“I have two names, so this one and my second name Lebo. Most of the time I don’t even use both of them, any of them. That’s because people tend to mispronounce Kelly or give me nicknames like shorten my name [to my initials] and I don’t like that… they give me reasons cause I’ve asked them ‘why do you not call me my name or give me another name’ they say my name is too long, yes, and has too many syllables and ya it’s too complicated… most of the time it’s non-black people and when it comes to black people it’s other cultures like the Zulus, the Xhosas, so you can say that most people get my name wrong.” (Kelly).

The extract from Kelly, perhaps corroborates the findings of Srinivasan (2019) where Kelly details the account in which nicknaming was used to make it easier for the other person, but in many ways resulted in othering, as reducing someone’s name to a nickname diminishes their identity, stripping away cultural and personal significance in favour of familiarity or convenience (Oyěwùmí and Girma, 2023). Mispronunciation or abbreviations of a name reinforce a sense of otherness and may result in pressuring individuals to alter their name to avoid the burden of correction or the anxiety of exclusion, a notion supported by Srinivasan (2019). This navigation of the role of names in social interactions requires constant negotiation, as Sarah describes having to assess each situation and adapt by choosing which version of their name would be most acceptable for the societal norms of the situation:

“I would use Nomzamo which is a shortened version of my first name. I used it when I was at work earlier this year. I sort of have to suss out which kind of situation, which kind of name or which name I would use in which situation.” (Sarah).

Sarah’s account is reflective of the perpetual, conscious and unconscious awareness of white hegemonic norms and the need to assimilate to these norms in order to allow for belonging. In particular, Sarah’s extract also illustrates the psychological effects of nicknaming, with a heightened sense of awareness that, on some level, mimics anxiety, demonstrating the continued effects of racism on people who are recipients (Pieterse and Carter, 2007).

Name-based microaggressions in the educational context

White dominant norms may be forcibly learned through innocuous or direct observation or even experiences of racism and microaggressions (Liu et al., 2019; Ponds, 2013). It is through the latter, with the occurrence of name-based microaggressions, that children learn early in their educational journeys how to assimilate into the dominant white culture (Liu et al., 2019). These events frequently occur in the educational context and may evoke strong emotional reactions, which cement learning of underlying white-centric norms to ensure social survival. For instance, Akeelah reflected on the pervasiveness of name-based microaggressions in white dominated societal spaces:

“Okay, people find it hard to say my name, so I’ll just shorten it for them and I say ‘Just say Akeelah’, at school, a lot of the time in high school. Even now at varsity actually yeah, school. So usually if it’s white people. I’ll say Akeelah cause they usually pronounce my name wrong or they’ll complain. Cause I’ve had like scenarios where a teacher complained that my name was too long and she couldn’t pronounce it so I just shortened it for her. But then with Black people, they know, they are okay with saying it, they say it properly, they pronounce it properly so ya.” (Akeelah).

Akeelah’s experience highlights the intensity of the pull to conform to white dominant spaces, reflecting the concept of white cultural hegemony (Dlamini, 2024). In this instance, it is perhaps clearer that through self-renaming, there is coercive consent—through the complaining—to white cultural hegemony that is occurring. As such, there is an acceptance, or perhaps a resignation, to the corrosive idea of white supremacy. Therefore, there is pressure to conform to the dominant white culture, ultimately sloughing off elements of Black people’s identity to reinforce the white supremist ideology. In self-renaming as well as its stripping of parts of Blackness can prolong survival for the Black person within the white dominant culture while simultaneously negatively impacting feelings of belonging and psychological wellbeing (Ponds, 2013; Srinivasan, 2019).

Busisiwe, in the below extract, perhaps indicates more clearly that the teachers’ mispronouncing her name, or renaming her at school, solidified the experience of feeling as though she did not belong in her school environment:

“But I sort of kept Themba uh, but then obviously the teachers would just butcher my name. Every time, every time. Uh, and then it was somewhat okay, I was in a Black school and they couldn’t have got it, you know they would try and they would still go with Themba. I think things took a serious turn when I got to a white, well a former white model C high school that had a really good mixture of races, cultures and all those sorts of things. And then there, I realized that firstly, that I wasn’t the only one who constantly struggled with this name thing. That so many other girls at the school had nicknames. Uhm because the teachers just couldn’t, and to certain extents they just weren’t willing. So, they would give you nicknames like for me, usually Busi, Busisiwe they would cut it to that, some would go with Themba, uhm others would – Themba, which is another common female name but that’s not my name, that’s not my name. So ya, you were constantly trying to be convenient, that’s it… It’s a microaggression. It wouldn’t be uhm like a bold statement of “your kind doesn’t belong here” but you sort of sense people’s annoyance. You sort of get the feeling that they are frustrated trying to say your name and things like that, uh where it’s like oh snap. It sometimes makes me feel like maybe I need to shrink my Blackness, why do I have such a bold Black name? Uhm, it feels like I need to assimilate to like I said, a nickname, a more white accommodating or whatever, non-black accommodating name that again I have to say, is more convenient. It does make you feel like you are intruding into a space when it feels like everybody else’s names, including very hard Afrikaans names are pronounced uh quite perfectly and yours is like a struggle. You do feel like sho, I’m not amongst my people.” (Busisiwe).

Educational systems in South Africa are deeply imbued with dominant white ideology, and racial stratification continues to occur within educational institutions today in subtle ways (Canham, 2018; Heleta and Nkala, 2018; Lin, 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Srinivasan, 2019). The school environment is a space where the social hierarchy enforcing white centrality and social norms may be tacitly communicated (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012). South African teachers may unknowingly perpetuate name-based microaggressions within the school context, while others are unwilling to make the effort to learn the correct pronunciation of Black students’ names (Tiwane, 2016). Students in primary, secondary, and tertiary educational institutions frequently experience racial microaggressions by both peers and educators (Canham, 2018; Kim and Lee, 2011; Nadal et al., 2014b). Black students are frequently the recipients of name-based microaggressions by white teachers, administrators, and peers who consciously or unconsciously struggle, or refuse, to correctly pronounce African names (de Klerk and Lagonikos, 2014; Ngubane and Thabethe, 2013), an experience encountered by most of the participants.

Effects of name-based microaggressions

Participants cited being deeply affected by name-based microaggressions, with many feeling that their culture had been undermined and disrespected throughout their schooling careers, which led them to feel that their names and their presence were an inconvenience and a burden (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012). Some people wished for a “common name”—understood as white—to enhance the experience of belonging, as the constant experience of perpetrated acts of racism creates the impression that elements of Black identities, such as one’s name, are undesirable and meaningless (Canham, 2018; Jones and Galliher, 2015; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Pérez Huber and Solorzano, 2015; Srinivasan, 2019). Participants reported feeling alienated, othered, and ashamed of their identity. This is highlighted in both Busisiwe and Akeelah’s experiences. Busisiwe coped by making use of a “more convenient” name, while Akeelah wished for and requested to go by an English translation of her given name:

“…Which led me to me thinking should I just also go with a, a more convenient name or nickname of some sort, because who am I if audit partners are, are still failing to address matters such as a name. Maybe I am being too pedantic, too picky? I should just you know, ya be happy with [my initials] or whatever that person chooses to call me that day you know?” (Busisiwe).

But you know at some point I did wish that, I told, cause I asked my mom, cause my name means Hope, I asked my mom, ‘Can I just change my name to Hope?’ you know, instead of saying Akeelah. Let’s just make it an English name because then everyone will get it right you know…so I don’t have to correct my, so I don’t have to correct people, they don’t have to ask me ‘What does your name mean’ cause everybody asks ‘What does your name mean’, like ‘How do you say your name’, ‘How is it spelled’, it’s a whole process you know (Akeelah).

The accounts by Busisiwe and Akeelah stress how, for many recipients of name-based microaggressions, the main difficulty involves feeling stripped of identity and heritage, as well as feelings of being a burden due to the presentation of their name in white dominated spaces (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019). Additionally, the pervasive nature of microaggressions requires much cognitive energy for the victim of these occurrences, in constantly processing and evaluating situations to which they can be accepted (Canham, 2018; Srinivasan, 2019). This was further stressed by Poloko, who reflected that he used a shortened version of his name in the past because of his experience of teachers struggling with the pronunciation of his name in primary school. He reported that now that he is older, he goes by his given name and likened this to a greater acceptance of his Black identity:

“Cause when I was in primary school some of my teachers called me [A shortened version of my name], you know just shortening me, because I think they had a problem with the [beginning] part and also the fact that it has three vowels in a row. They found a problem pronouncing it… I felt like, why should I compromise or try to Anglicize my name to make you feel better, you know? To make things easier for you? … So why do you have to like shorten it or anglicize it or do whatever it is to make it easier for the next person to say it. To make the next people feel comfortable with your name so they feel like they are not offending you. Whereas the mere essence of them trying to make your name into what it’s not, is offensive in and of itself” (Poloko).

Furthermore, white dominated society leaves Black people with no option other than to become consciously or unconsciously “racially innocuous” to fit in, by behaving in ways that come across as unthreatening. This is achieved by softening or neutralising racial and cultural aspects of their identity to fit into the dominant culture and adapt to the standards of whiteness, which are the invisible norm (Canham, 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Pérez Huber and Solorzano, 2015; Srinivasan, 2019).

Kelly’s experience is perhaps also telling, where she reflected on the difficulty of resorting to assimilation by providing people with an alternative name that is more ‘comfortable’ for them when they struggled with the pronunciation of her name:

“I just prolong telling them, correcting them getting my name wrong like, ‘Okay please don’t call me that, just call me Kelly.’ So now I’ve developed this thing that whenever I introduce myself to people especially if I know that it’s gonna be hard for them to pronounce my name, I just tell them that, ‘Okay I’m Pabi but you can just call me Kelly.’ And that way they are always gonna opt for Kelly.” (Kelly).

In this sense, Kelly discards an element of her Black identity to make social interactions more convenient for the other, instead of the other taking responsibility to learn the correct pronunciation of her given name. Names form an essential part of identity development (Wang et al., 2023), particularly in the South African context, where names have important links to the individual’s history, culture, ethnicity, their relationship to others, their wider socio-cultural, and spiritual context (Emmelhainz, 2012; Herbert, 1997; Kim and Lee, 2011; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Ngubane and Thabethe, 2013; Srinivasan, 2019).

Among many effects, one major implication is acculturative stress. Assimilation becomes challenging in the conflict between adapting to the values and worldviews of the dominant culture while maintaining ties to one’s own culture and heritage (Kim and Lee, 2011; Liu et al., 2019; Srinivasan, 2019; Stevens, 1998). Of necessity, Black people must learn bicultural adaptation to navigate assimilation into the dominant culture without losing ties to elements of their culture and origins (Jones and Galliher, 2015). Busisiwe reflected on the difficulties of navigating between two opposing cultures:

“I’ve gone to a very mixed school so you, firstly which was great cause you get to interact with people from different walks of life. But you also become aware that I am different, right? What happens is, instead of us being, ‘we are all different and let’s all live in our differentness’, we all sort of move in assimilation into a sort of one kind of side and spectrum you know. So, in my very mixed school, literally we were so mixed, I was living a very white-like culture and it was an all-girls school so we were ladies we were posh and quiet and well-spoken and soft and you know, that was our, our culture that we lived there and you didn’t wanna be ‘the loud Black’. You know, so we would keep it very posh. But when I would go home, I have had this experience of what we do at school from seven to like four cause I had extra murals like five days a week. And then you go home to the community where it’s a Black community and now I introduce myself as Busisiwe, ‘I was just talking to my friend and Busisiwe said this… ‘Hmm Busisiwe? Who’s Busisiwe now, why are you being, why are you acting white? You are a coconut.’ Coconut. That’s the term. You are a coconut. So, you constantly have this battle you know at school I’m not white enough I’m too black, at home I’m, I’m sort of too white for a Black girl you know that sort of thing.” (Busisiwe).

Busisiwe’s experience perhaps belies the notion of the rainbow nation, in which multiculturalism is celebrated and embraced by all, but rather it is the ‘white hues’ in which the colours of the rainbow meet that is the focal area (Chikane, 2018). For many, navigating the balance between maintaining their cultural identity and assimilating to the dominant culture becomes a challenge, which can result in acculturative stress due to these challenges in adjustment (Jones and Galliher, 2015; Srinivasan, 2019). Shifting identities between each culture can result in emotional and psychological distress (Liu et al., 2019). This is prevalent in the South African context, where Black people are frequently stereotyped as “Cheese boys/girls” or “Coconuts” for behaving in a way that is seen as too Westernised or white (Bornman et al., 2018). Goodman (2012) argued that the way in which Black people live is in a hybrid ‘in-between’ space, which results in never feeling a full sense of belonging in either space. Inhabiting two spaces by adjusting your identity to fit the norms of each space can be described as a survival strategy; therefore, the ‘Coconut identity’ can be seen as a consciousness that allows for increased chances of survival (Goodman, 2012).

Busisiwe noted the psychological implications of name-based microaggressions on her confidence and reflected on the dissonance that she experiences when a name-based microaggression occurs. Busisiwe questioned whether she was expecting too much from others to pronounce her name correctly, and how these experiences were so impactful that she considered changing to her second name instead of her given name:

“I’ve noticed that it has had a slight impact in my confidence. I have even considered even changing to maybe my second name, which is also a mouthful you know. But I felt like, you know, there’s no funny nickname that anybody can call me on that. I thought you know, maybe am I expecting too much? Should I just let it be and maybe just change to a different nickname.” (Busisiwe).

This experience highlights the frustration that occurs when name-based microaggressions are experienced and the breakdown that leads to the eventual coercive compliance with, and assimilation into the societal norm. The experience of name-based microaggressions can be detrimental to the healthy identity development of Black South African students, as it communicates that their name, and on a wider level, their whole being, does not belong in white dominated spaces (Canham, 2018; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019). For some people, the associated psychological effects of anxiety, shame, sadness, frustration, and resentment regarding the lack of acceptance of their given names lead to the association of their names with discomfort rather than pride (Friedman, 2021; Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019). Name-based microaggressions negatively affect the sense of self and worldview of the person and can undermine positive identification with their own cultural heritage and ethnicity. Recipients of name-based microaggressions may feel psychological distress due to social ostracism and rejection and may thus feel doubtful of their place in the social world (Srinivasan, 2019). This can ultimately lead to internalised racism (Jones and Galliher, 2015; Wang et al., 2023; Srinivasan, 2019).

Akeelah’s experience highlights the occurrence of self-blame that can occur after experiencing a microaggression, such as name-based microaggressions. Microaggressions can occur with such subtlety that recipients are often left in a state of confusion as to the nature and meaning of microaggressive communication. Pressure to alter the presentation of your name has been linked to increased psychological distress (Srinivasan, 2019). In some cases, participants felt irritated with themselves when they felt they had not adequately dealt with the perpetrator of name-based microaggressions. Some struggled to correct perpetrators because they were stationed in positions of authority, especially teachers, and thus participants felt it was difficult to defend against the occurrence of name-based microaggressions:

“Now that I look back, I feel like I made myself inferior in that situation, like I took what they thought about me and I just went along with it instead of correcting them and saying no that’s wrong, that’s not right. I feel like I just kept quiet for the sake of keeping quiet – to not cause a big thing. Now I’m able. I’m able to speak up and say ‘Now, this is the proper way to say it, if you can’t say it this way, then this is how you’ll say it, I’ll give you the shortened name, if you can’t say the shortened name, then I’ll give you my second name.’ Now that I look back, I’m like woah that was racist! I didn’t know what racism was, I didn’t understand the extent to which racism is, right. So, the reason why I didn’t stand up for myself is the excuse was, ‘You’re in an Afrikaans school’ you know, it was always ‘You’re in an Afrikaans school, don’t expect a lot’. You know, ‘You chose to be in an Afrikaans school, you chose this’. So, it was like, ‘Conform or get lost.’” (Akeelah).

The subtle nature of microaggressions means that they require significant cognitive and psychological energy to identify, clarify, and cope with. This creates a baseline of hypervigilance, which some have denoted as “Racial Battle Fatigue” (Bryant-Davis and Ocampo, 2005; Canham, 2018; Srinivasan, 2019). Busisiwe shared her experience at school, whereby teachers struggled to pronounce her name to the point where others would laugh at her when the teacher pronounced her name incorrectly:

“And from an early age I always felt this name was an inconvenience. When I started going to school, I had to go by my official name now, Busisiwe, but the teachers couldn’t pronounce it. Or they would try, but some would get lazy and then they would just call me [a shortened version of my name]. And I wouldn’t have minded except for this one minor detail, at that time, I think it was about 2006, 2007, oh I’m actually getting a little bit emotional. There was a sitcom in, that played on our local TV station. There was a character there named Busisiwe, the name when you cut my name in short. And he played this funky character who was a low-life and uhm basically just lame, that was it. And so, whenever a teacher would call me [a shortened version of my name], that’s what would happen, people would giggle in the class, during breaks now I’m being teased. I was so ashamed.” (Busisiwe).

Overall, participants reflected on the strain of assimilating to dominant white hegemonic norms and what that meant for their identity development and experience of belonging in the social world, particularly in the educational context. The experience of microaggressions and name-based microaggressions over time may lead to compromised physical health and mental wellbeing, the latter manifesting as increased anxiety, depression, grief, and suicidal ideation (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019).

Conclusion

In this study, we intended to elucidate the relationship between white cultural hegemony and name-based microaggressions within contemporary South African society. We specifically aimed to illustrate how the occurrence of name-based microaggressions within educational institutions is a function of white cultural hegemony. Racism in the global white cultural hegemony can manifest in various ways, including in the form of name-based microaggressions, the function of which is to “make strange” from the perspective of the dominant colonial gaze. While racism tended to be communicated in more direct methods in the past, white supremacy is communicated more subtly in contemporary postcolonial society. Therefore, the occurrence of microaggressions generally, and name-based microaggressions more specifically, is more widespread.

Mispronunciation and renaming of Black people’s names are deeply entrenched and commonplace. This serves in the infra-humanisation of African language, culture, and elements of identity. Resultantly, Black life-worlds are subtly communicated as undesirable. The occurrence of name-based microaggressions not only disregards the significance of African names but simultaneously communicates the message that elements of Black identities do not belong. Lived experiences of the participants in this article demonstrated that this message also exists in the educational context, whereby white cultural hegemony extends into the classroom or lecture hall, serving a function of the othering of Black South African students.

To meet the aim of the study, eight semi-structured interviews were conducted investigating the experience of name-based microaggressions by Black South African university students and the associated psychological effects of such microaggressions. After data analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s (2006, 2012) Thematic Analysis (TA), the following themes emerged: name mispronunciations and Black names as an inconvenience; name-based microaggressions in the educational context; and the effects of name-based microaggressions.

Participants communicated about the difficult experience of navigating social environments dominated by white norms. Participants felt that their Black/African names were positioned as difficult or inconvenient within the educational context. Some participants experienced ridicule for the presentation of their names by both peers and teachers. Participants invested psychological energy in the perpetual awareness of white hegemonic norms and the need to assimilate in different spaces. Learning to accommodate the dominant culture was a way to ensure a sense of belonging and survival in the social world. Stripping away elements of Black identities was a way to be more acceptable and convenient at school. By choosing a white name or nickname or altering the presentation of given names to a more white-sounding name, Black students avoided ridicule and felt less burdensome in school environments. In these experiences of name-based microaggressions, the relationship between white cultural hegemony and name-based microaggressions is revealed in the sense that Black names and elements of Black identities are subtly communicated as undesirable and are othered, while elements of whiteness are communicated as normative. The pressure of this communication results in Black students having to accommodate to white norms and strip away parts of the self that are seen as less desirable.

Children learn through direct observation or direct experiencing of racism and microaggressions within their educational journey, the demands of the social environment and ways to assimilate. This perpetual awareness of white hegemonic norms in educational systems is a way to ensure social survival. Dominant white norms are communicated consistently, whether consciously or unconsciously, and Black South African students feel the intensity of the pull to conform to white dominated spaces. Participants in the current study reflected on their experiences of being renamed or having their names mispronounced by teachers.

The occurrence of name-based microaggressions, while commonplace, is not an innocent social exchange. Rather, name-based microaggressions can have deleterious effects on cohesive identity development, which may result in negative impacts on psychological wellbeing. Overall, participants reflected on the strain of assimilating to dominant white hegemonic norms and what that meant for their identity development and experience of belonging in the social world, particularly in the educational context. The experience of microaggressions and name-based microaggressions over time may lead to compromised physical health and mental wellbeing, the latter manifesting as increased anxiety, depression, grief, and suicidal ideation (Kohli and Solórzano, 2012; Srinivasan, 2019).

Participants in the current study reflected that they felt undermined and disrespected at school when name-based microaggressions were communicated towards them. The experience of name-based microaggressions made them feel as though their names were inconvenient and burdensome, which negatively impacted confidence and self-esteem. This often resulted in feelings of shame and alienation, and a wish for a more common or white/English-sounding name, to enhance the experience of belonging. Participants felt the anxiety and pressure to conform to white norms, which resulted in acculturative stress. The experience of name-based microaggressions required much cognitive energy to unpack and respond to due to their subtleness. Some participants expressed that navigating name-based microaggressions resulted in self-blame and questioning whether they were being too pedantic or picky when asserting the correct pronunciation of their name to perpetrators of name-based microaggressions.

While the present study appears to be the first of its nature in South Africa and perhaps raises significant issues as it pertains to race and racism in this context, there are some shortcomings that could be addressed in future studies. First, the study did not directly attempt to delineate experiences of name-based microaggressions by gender; that is, although the participants were asked about their gender and sex, the study did not find any gendered or sexed reporting experiences. This is not to say that there may not be any differences, as Black women may experience intersectional microaggressions (Crenshaw, 2013). Secondly, the study did not include an explicit differentiation across the Black cultural and linguistic groups. It is unclear if such a differentiation would be useful, as the results in this study demonstrated similarities in experience rather than differences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee, University of Johannesburg. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, W. C. (2010) in Conducting semi-structured interviews. Handbook of practical program evaluation. eds. J. S. Wholey, H. P. Hatry, and K. E. Newcomer (Jossy-Bass), 492–505.

Ahmed, S. (2002). “Racialized bodies” in Real bodies: A sociological introduction. eds. M. Evans and E. Lee (New York: Palgrave), 46–63.

Bantu Education Act No. 47 of 1953. Available online at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archivefiles2/leg19531009.028.020.047.pdf

Bock, Z. (2018). Negotiating race in post-apartheid South Africa: Bernadette’s stories. Text Talk 38, 115–136. doi: 10.1515/text-2017-0034

Bornman, E., Alvarez-Mosquera, P., and Seti, V. (2018). Language, urbanisation and identity: young black residents from Pretoria in South Africa. Lang. Matters 49, 25–44. doi: 10.1080/10228195.2018.1440318

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Research designs. ed. H. Cooper, vol. 2 (The American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Bryant-Davis, T., and Ocampo, C. (2005). The trauma of racism: implications for counseling, research and education. Counsel. Psychol. 33, 574–578. doi: 10.1177/0011000005276581

Cakata, Z., and Ramose, M. B. (2021). When ukucelwa ukuzalwa becomes bride price: spiritual meaning lost in translation. African Identities 1-13. doi: 10.1080/14725843.2021.1940091

Canham, T. M. K. (2018). Black ex-model-C school learners’ experiences of racial microaggressions University of Cape Town. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/30494

Chikane, R. (2018). Breaking a rainbow, building a nation: The politics behind# MustFall movements. South Africa: Pan Macmillan.

Cobb, J. (2021). The man behind critical race theory. The New Yorker. Available online at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/20/the-man-behind-critical-racetheory?utm_medium=social&utm_socialtype=owned&utm_source=linkedin&utm_bran=tny

Crenshaw, K. (2013). “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics” in Feminist Legal theories. ed. K. Macheke (New York: Routledge), 23–51.

de Klerk, V., and Lagonikos, I. (2014). First-name changes in South Africa: the swing of the pendulum. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 170, 59–80. doi: 10.1515/ijsl.2004.2004.170.59

de Man, A. (2022). Reconsidering corruption as a violation of the rights to equality and non discrimination based on poverty in South Africa. J. Jurid. Sci. 47:52 76.

Dlamini, S. (2020). Language in professional psychology training: Towards just justice. Psychology in Society, 86–106.

Dlamini, S. (2024). Beyond the pretty white affair: Training Africa-centring psychologists for the future. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

Dlamini, S. (2025). “Interculturality and white cultural hegemony in south African professional psychology” in African perspectives on Interculturality: Decolonialities, epistemologies, and human relations. ed. H. R’oubl (UK: Routledge).

Emmelhainz, C. (2012). Naming a new self: identity elasticity and self-definition in voluntary name changes. Names J. Onom. 60, 169–178. doi: 10.1179/0027773812Z.00000000022

Foster, D. (1991). ‘Race’ and racism in south African psychology. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 21, 203–210. doi: 10.1177/008124639102100402

Franchi, V. (2003). Across or beyond the racialized divide? Current perspectives on ‘race’, racism and ‘intercultural’ relations in ‘post-apartheid’ South Africa. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 27, 125–133. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00090-1

Friedman, B. (2021). Why the mispronunciation of your name… or anyone else’s… matters. Cape Talk 567AM. Available online at: https://www.capetalk.co.za/articles/406872/why-themispronunciation-of-your-name-or-anyone-else-s-matters

Goodman, R. (2012). Kopano Matlwa’s coconut: identity issues in our faces. Curr. Writ. 24, 109–119. doi: 10.1080/1013929X.2012.645365

Gordon, L. R. (2012). Of illicit appearance: The LA riots/rebellion as a portent of things to come : Truth Out. Available online at: https://truthout.org/articles/of-illicit-appearance-the-la-riots-rebellion-as-a-portent-of-things-to-come/

Gramsci, A. (1971). In Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Eds. Q. Hoare, and In G Nowell-Smith. ElecBook.

Hawthorne, W., Roberts, R., Seck, F., and Wall, R. (2025). Introduction: The Politics and Ethics of Naming the Names of Enslaved People in Digital Humanities Projects. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 19.

Heleta, S., and Nkala, T. (2018). Why students reject whiteness. Mail & Guardian. Available online at: https://mg.co.za/article/2018-05-04-00-why-students-reject-whiteness/

Herbert, R. K. (1997). The politics of personal naming in South Africa. Names 45, 3–17. doi: 10.1179/nam.1997.45.1.3

Hiss, A., and Peck, A. (2020). “Good schooling” in a race, gender, and class perspective: the reproduction of inequality at a former model C school in South Africa. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2020, 25–47. doi: 10.1515/ijsl-2020-2092

Inscoe, J. C. (1983). Carolina slave names: An index to acculturation. J. Southern Hist. 49, 527–554.

Jones, M., and Galliher, R. V. (2015). Daily racial microaggressions and ethnic identification among native American young adults. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 21, 1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0037537

Kamwendo, G. H. (2010). Denigrating the local, glorifying the foreign: Malawian language policies in the era of African Renaissance, Int. J. Afr. Renaiss. Stud. 5, 270–282. doi: 10.1080/18186874.2010.534850

Kim, J., and Lee, K. (2011). “What’s your name?”: names, naming practices, and contextualized selves of young Korean American children. J. Res. Childhood Educ. 25, 211–227. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2011.579854

Kohli, R., and Solórzano, D. G. (2012). Teachers, please learn our names!: racial microaggressions and the K-12 classroom. Race Ethn. Educ. 15, 441–462. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.674026

Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 11, 7–24. doi: 10.1080/095183998236863

Lin, M-C. (2018). When you mispronounce someone’s name, you do more than just butcher it. News24. Available online at: https://www.news24.com/w24/SelfCare/Wellness/Mind/when-youmispronounce-someones-name-you-do-more-than-butcher-it-20180118

Liu, W. M., Liu, R. Z., Garrison, Y. L., Kim, J. Y. C., Chan, L., Ho, Y. C. S., et al. (2019). Racial trauma, microaggressions, and becoming racially innocuous: the role of acculturation and white supremacist ideology. Am. Psychol. 74, 143–155. doi: 10.1037/amp0000368

Lombard, B. J. J. (2007). Reasons why educator-parents based at township schools transfer their own children from township schools to former model C schools. Educ. Change 11, 43–57.

Malherbe, N., and Dlamini, S. (2020). Troubling history and diversity: disciplinary decadence in community psychology. Commun. Psychol. Glob. Persp. 6, 144–157.

Manganyi, C. (1984). Making Strange: Race Science and Ethnopsychiatric Discourse : University of the Witwatersrand.

Matthews, S. (2012). White anti-racism in post-apartheid South Africa. Politikon 39, 171–188. doi: 10.1080/02589346.2012.683938

Mkhize, Z., and Muthuki, J. (2019). Zulu names and their impact on gender identity construction of adults raised in polygynous families in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Nomina Africana 33, 89–98. doi: 10.2989/NA.2019.33.2.2.1339

Mlachila, M. M., and Moeletsi, T. (2019). Struggling to make the grade: a review of the causes and consequences of the weak outcomes of South Africa’s education system. Available online at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/03/01/Struggling-to-Make-theGrade-A-Review-of-the-Causes-and-Consequences-of-the-Weak-Outcomes-of-46644

Modiri, J. M. (2012). The colour of law, power and knowledge: introducing critical race theory in (post-) apartheid South Africa. S. Afr. J. Hum. Rights 28, 405–436. doi: 10.1080/19962126.2012.11865054

Mokoena, K. B. (2020). The subtleties of racism in the south African workplace. Int. J. Crit. Divers. 3, 25–36.

Moorosi, P. (2020). Colour-blind educational leadership policy: a critical race theory analysis of school principalship standards in South Africa. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 49, 644–661. doi: 10.1177/1741143220973670

Moomal, H., Jackson, P. B., Stein, D. J., Herman, A., Myer, L., Seedat, S., et al. (2009). Perceived discrimination and mental health disorders: The South African Stress and Health study. South African Medical Journal 99, 383–389.

Mouton, N., Louw, G. P., and Strydom, G. (2013). Critical challenges of the south African school system. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 12:31.

Musila, G. A. (2017). Navigating epistemic disarticulations. Afr. Aff. 116, 692–704. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adx031

Mzileni, P., and Mkhize, N. (2019). Decolonisation as a spatial question: the student accommodation crisis and higher education transformation. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 50, 104–115. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2020.1733649

Nadal, K. L., Griffin, K. E., Wong, Y., Hamit, S., and Rasmus, M. (2014a). The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: counseling implications for clients of color. J. Couns. Dev. 92, 57–66. doi: 10.1002/j.15566676.2014.00130.x

Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Griffin, K. E., Davidoff, K., and Sriken, J. (2014b). The adverse impact of racial microaggressions on college students’ self-esteem. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 55, 461–474. doi: 10.1353/csd.2014.0051

Nepton, A., Farahani, H., Olaoluwa, I. F., Strauss, D., and Williams, M. T. (2025). How racial microaggressions impact the campus experience of students of color. Acad. Mental Health Well-Being 2, 1–13.

Ngubane, S., and Thabethe, N. (2013). Shifts and continuities in Zulu personal naming practices. Liberator 34:a431. doi: 10.4102/lit.v34i1.431

Nkosi, Z. P. (2014). Postgraduate students’ experiences and attitudes towards isiZulu as a medium of instruction at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Curr. Issues Lang. Plann. 15, 245–264. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2014.915456

Oyěwùmí, O., and Girma, H. (2023). Naming Africans: On the epistemic value of names. North Carolina: Springer Nature.

Pérez Huber, L., and Solorzano, D. G. (2015). Visualizing everyday racism: critical race theory, visual microaggressions, and the historical image of Mexican banditry. Qual. Inq. 21, 223–238. doi: 10.1177/1077800414562899

Pieterse, A. L., and Carter, R. T. (2010). An Exploratory Investigation of the Relationship between Racism, Racial Identity, Perceptions of Health, and Health Locus of Control among Black American Women J. Couns. Psychol. 21, 334–348. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0244

Pieterse, A. L., and Carter, R. T. (2007). An examination of the relationship between general life stress, racism-related stress, and psychological health among black men. J. Couns. Psychol. 54, 101–109. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.101

Ponds, K. T. (2013). The trauma of racism: America’s original sin. Reclaim. Child. Youth, 22, 22–24. Available online at: https://reclaimingjournal.com/sites/default/files/journal-articlepdfs/22_2_Ponds.pdf

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 23, 334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 33, 77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362

Segalo, P., and Cakata, Z. (2017). A psychology in our own language: redefining psychology in an African context. Psychol. Soc. 54, 29–41.

Soudien, C., Moodley, K., Adam, K., Brook Napier, D., Abdi, A. A., and Badroodien, A. (2014). Thinking about the significance of Nelson Mandela for education. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 44, 960–987. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2014.959365

Spaull, N. (2013). South Africa’s education crisis: the quality of education in South Africa 1994–2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development and Enterprise, 21, 1–65.

Srinivasan, R. (2019). Experiences of name-based microaggressions within the south Asian American population. New York: Columbia University.

Stefancic, J., and Delgado, R. (2011). “Critical Race Theory: An Introduction” in Chapter 1: Introduction – 1-14 (New York University: Press. Second Edition).