- 1Department of Software Science, Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech), Tallinn, Estonia

- 2LEARN! Research Institute, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Project-based learning is widely recognized as an effective pedagogical approach in software engineering education, fostering real-world problem-solving, collaboration, and the integration of theory and practice. However, its scalability is challenged by the resources demanded for individualized feedback, especially in large classes. This pilot study explored the feasibility of simulated automated formative feedback to support student teams in a project-based software engineering course. Eighty-six students participated over 4 weeks, alternating between receiving simulated automated formative feedback emulated by instructors and standard feedback. Weekly surveys assessed perceptions of usefulness and motivation. No statistically significant differences were found between feedback conditions (Cohen's d = 0.16). Students expressed positive attitudes toward the simulated automated formative feedback: 78% agreed it supported their learning goals, and 74% reported it increased motivation. These findings suggest that automated feedback tools may effectively complement instructor support, offering a scalable solution for enhancing formative feedback in project-based learning environments.

1 Introduction

With the increasing complexity of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) education, personalized learning approaches are becoming essential. ICT curricula now emphasize hands-on, project-based learning, where students work on real-world problems, often in collaboration with industry partners. This approach bridges the gap between theory and practice, ensuring graduates are well-prepared for professional challenges. Engineering education is moving toward student-centered learning for large groups, combining customized off-campus online learning with hands-on, experiential learning on campus. Modern ICT curricula continue to evolve to include personalization, adaptive learning, and real-time feedback to support the diverse needs of students (Graham, 2018).

A software engineering course should provide students with the technical skills essential for software development and help them develop their soft skills. Software engineering courses contain both technical and non-technical topics and can be complex from a teaching perspective (Ceh-Varela et al., 2023). Several studies have demonstrated that the project-based learning methodology is an effective approach for software engineering courses (Adorjan and Solari, 2021; Ceh-Varela et al., 2023; Fioravanti et al., 2018; Luburić et al., 2024; Subramaniam et al., 2017). Under this approach, students develop practical skills along with theoretical knowledge and essential soft skills, such as teamwork, communication, and project management. In software engineering courses, project-based learning covers the complete software development lifecycle from initial planning and requirement analysis to design, implementation, testing, deployment, and maintenance.

Moreover, Adorjan and Solari (2021) and Ceh-Varela et al. (2023) argue that the application of project-based learning to a software engineering course is effective not only with in-person students but also with online students or in a hybrid classroom environment. Although project-based learning provides students with many benefits, it is resource-intensive and can be challenging for students and teachers. A key aspect of the learning outcomes of software engineering courses focuses on developing the ability to manage technology and solve problems. Teachers should support students who need help with technology management or project development. Subramaniam et al. (2017) emphasize the role of formative feedback in helping students revise design choices during iterative development, facilitating reflection on emerging challenges, guiding strategic adjustments to prototypes, and building learners' confidence and competence throughout the software development lifecycle.

According to Subramaniam et al. (2017), formative feedback is essential for sustaining student progress during iterative development. It facilitates reflection on emerging challenges, supports strategic adjustments to prototypes, and strengthens learners' confidence and competence across all stages of the software development lifecycle. However, providing such feedback is challenging for teachers, especially in large classes where multiple student teams work on unique projects. In addition, the feedback should be given quickly enough (Sembey et al., 2024). Usually, students receive feedback once a week at face-to-face meeting sessions. Alternatively, they can contact the teacher by email, and the teacher should respond to the email within 3 days. As a result, students can spend a lot of time waiting for a response.

To cope with this problem, studies (Jia et al., 2022; Langove and Khan, 2024) recommend using automated immediate feedback or other tools to support students and facilitate reflection. Jia et al. (2022) demonstrate that automated systems can support this process by providing timely and structured feedback in project-based courses and reducing the workload of teachers. Managing this complexity requires scalable support mechanisms to ensure that students receive timely and effective practical guidance. Such systems have the potential to reduce instructor workload and support reflection, but their effectiveness depends on careful design and alignment with pedagogical principles. According to the Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988), learners have limited capacity in working memory, so instructional strategies must minimize unnecessary cognitive effort. This is especially pertinent in project-based learning environments, where students encounter open-ended problems and are required to engage in complex, higher-order thinking. Feedback that presents excessive or poorly structured information may increase the cognitive load and overwhelm students.

To support learning without overloading cognitive resources, any automated (or emulated) feedback process should be grounded in the principles of the Cognitive Load Theory. Feedback should be segmented into concise (small and manageable) units, delivered just-in-time, and supported with visual elements to reduce extraneous load. Early scaffolding should guide learners through complex tasks, with support gradually reduced as expertise develops. Tiered feedback progressing from hints to full solutions can accommodate varying levels of learner proficiency. Where feasible, comparisons with peer solutions and adaptation to individual learner models can further enhance relevance and cognitive efficiency. The timing of feedback is equally critical. Immediate feedback is particularly effective for procedural tasks such as tool use or data entry, whereas delayed feedback better supports metacognitive reflection and strategic problem-solving. Conceptual feedback, aimed at deeper understanding, should be provided after task completion to facilitate reflective learning. Automated feedback should be concise, timely, and systematically structured to avoid overloading learners' working memory. Well-designed feedback reduces extraneous load and enhances germane load, supporting schema construction. Early-stage learners benefit most from scaffolding, while more advanced learners require less instructional support (Sweller, 2020).

Another issue is that project-based learning often incorporates elements of informal learning, particularly when students take ownership of their projects, explore topics beyond the curriculum, and engage in self-directed or peer-driven learning. The level of formality depends on how the project is designed and implemented (Rostom, 2019; Ulseth, 2016).

Therefore, we believe that rather than a separate feedback tool, a context-aware system that integrates an automated feedback mechanism is needed in the future. In this study, we emulate such automation using instructors, focusing on its feasibility rather than a fully automated intervention.

The objective of the current pilot feasibility study was to explore how context-aware simulated automated formative feedback affects students during project-based learning in software engineering courses compared to traditional feedback. To achieve this, we conducted an experiment where instructors provided simulated automated formative feedback in team-based programming projects, evaluating its feasibility and impact from the student perspective. This paper examines the role of such simulated automated formative feedback in comparison with traditional feedback and discusses its implications for project-based learning in software engineering curricula.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: in Section2, we clarify the context of our discussion, the terminology used, the methodology and how we designed and conducted the experiment; we present the results in Section 3; Section 4 provides analysis and discussion, addresses the limitations of the study and outlines directions for future work.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Background and motivation

In this section, we clarify the context of our experiment and the terminology used.

2.1.1 Project-based learning in engineering education

A study (Ingale et al., 2024) involving 816 engineering students strongly supports the need for implementing project-based learning in engineering disciplines. Emphasizing practical application, collaborative problem-solving, and real-world relevance, project-based learning could address many of the shortcomings of the traditional approach.

Research (Palmer and Hall, 2011) breaks down project-based learning in engineering education into the following components:

• Students complete a number of educational activities as per the problem or project tasks

• Students work on projects in teams

• The nature of projects is non-trivial, real-world, and often multi-disciplinary

• The projects include the development of a concrete artifact, such as a design, model, thesis, or computer simulation

• At the end of the project, students write a report describing the project methods and the final product and participate in the project defense with an oral presentation

• Project supervisors or instructors take on the roles of advisors or coordinators

Project-based learning enhances the student experience by fostering teamwork, self-motivation, and a sense of ownership of the problem, solution, and learning process. It also promotes self-regulation, problem-solving skills, and engagement with authentic engineering challenges and professional practices. In addition, project-based learning helps students develop and understand the interdisciplinary and systemic nature of engineering problems while improving reflective, written, oral, and other communication skills (Palmer and Hall, 2011).

2.1.2 Project-based learning in the software engineering course

A software engineering course is complex to teach. Previous studies have demonstrated that project-based learning is effective in teaching software engineering education curricula. This approach allows students to apply their knowledge in practice and provides the opportunity to work on real-life projects that are as close as possible to industrial practices and include advanced technologies, boosting motivation significantly (Adorjan and Solari, 2021; Ceh-Varela et al., 2023; Luburić et al., 2024; Subramaniam et al., 2017). Software engineering courses involve computer science's analytical and descriptive tools, algorithms, debugging tools, and modeling and simulation tools, as well as engineering's rigor for software development.

The project-based approach to teaching software engineering courses offers students the opportunity to go through the full software development lifecycle. Throughout this process, students work in teams and develop complex software while applying their theoretical knowledge (Ceh-Varela et al., 2023).

2.1.3 Student support during project-based learning

Project-based learning provides many benefits to students. Despite this, project-based learning also comes with a set of challenges. Researchers (Palmer and Hall, 2011) conducted a project-based study in which they conducted a survey among students. As a result, students confirmed the aspects listed in Section 2.1.2 as positive. As negative aspects, students noted the significant time demands, routine documentary work, idea generation, searching for information and methods for problem-solving, managing teamwork as well as problems with team members who did not complete their tasks. Students also cited the need for guidance and preparation for teamwork as well as guidance in writing design/engineering reports.

One component of the learning objectives of software engineering courses is related to the ability to use technology and solve problems. Students often lack experience and need support in both areas. Teachers typically support students during project-based learning through weekly face-to-face sessions, during which the students report on what they have done, and the teacher gives feedback. Research has shown that students see this support as insufficient. Among the suggestions for improvement, the most common is students' need for support and guidance as well as faster feedback and formative feedback (Jaber et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2022).

2.2 Methods

The experiment is based on four aspects: the participants involved, the instruments used, the procedures carried out, and the results obtained.

2.2.1 Participants

In total, 86 students participated in the experiment. The participants were the first-year bachelor-level students of the Business Information Technology study programme at Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech) who were enrolled in the “Information Systems Development II: Development Techniques and Web Applications” study course in the spring of 2024.

The Business Information Technology study programme at TalTech is a 3-year bachelor's degree programme designed around inductive learning approaches. It includes project-based software development courses where students work on projects in teams, with each team having a unique project. Such project-based courses focus on software engineering and are offered to students starting from the first year of study. The “Information Systems Development II: Development Techniques and Web Applications” course aims to introduce the fundamental concepts of software development in a professional context. The course is focused on software engineering and introduces the quality context: requirements, usability, code quality, and testing. The course is worth 12 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) credits, which, according to the Estonian legislation, corresponds to a total workload of 312 h per student during the semester. The course duration is 16 weeks. The software development project is a part of the course. The theoretical and practical materials of the course were studied from weeks 1–12. Students received project ideas from the instructor and worked on the projects for 4 weeks, from the 13th to the 16th week. All project ideas were based on real-life scenarios, allowing students to apply their knowledge in real-world conditions.

After receiving the project ideas from the instructor, the students had to review the project requirements, form project development teams of two members, and define their roles. Once the teams were formed, each student team had to choose one of the proposed project topics and prepare and present a plan for implementing the project. The instructor provided feedback on the plan. After reaching an agreement with the instructor on the plan and deadlines, the student teams worked independently on their projects. The students presented mid-term progress reports at weekly meetings (once per week). After each presentation, the instructor gave feedback on the students' work. The students then continued to work on the project and prepared for the final presentation and defense.

2.2.2 Experiment design and procedure

The experiment was conducted over 4 weeks (while students were working on the projects). The project period was divided into four milestones/phases (with each phase lasting 1 week):

1) First week: the data model is designed and programmed, data tables are generated for all classes, and all data layer classes are tested with unit tests.

2) Second week: the domain logic layer and repositories are designed and programmed, and all corresponding classes are tested with unit tests.

3) Third week: all presentation layer classes and controllers are designed and programmed, and everything is tested with integration tests.

4) Fourth week: all presentation layer views are designed and programmed, and everything is tested with acceptance tests.

The students were randomly divided into four groups with the condition that students working on the same project (belonging to one development team) always ended up in the same group: Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, and Group 4. For each phase, one group was selected and assigned to the experimental condition (in the first week of the project period, Group 1 was in the experimental condition; in the second week, Group 2, and so on). The remaining students were included in the control condition. Thus, the students in the experimental and control conditions changed weekly. This was necessary to ensure that all students received equal treatment during the course. This approach ensured that each student experienced both feedback conditions, thereby increasing statistical power and mitigating any issues related to incomparability between groups.

All students were informed in advance about the experiment and given the choice to participate voluntarily. Those who opted out were able to complete the course as usual. No personal data were collected, and participants consented to the use of their anonymized survey responses for research purposes. Ethical approval was not required for this study because it was conducted anonymously, with informed consent obtained from all participants, and no personal data were collected. All procedures complied with the institutional and national ethical requirements.

Students in the experimental condition were randomly divided among three teachers (with the same condition as mentioned above: students working on the same project had the same teacher). Additionally, we conducted a comparative analysis of the key characteristics of the students distributed among the teachers to ensure that each teacher received a group of students with an equivalent skill level. The students worked on the project tasks throughout the week. Students in the experimental condition were guided and received simulated automated formative feedback almost in real time throughout the week. In the control condition, which followed business-as-usual practices, students received feedback at the end of the week in which the deadline for submitting work was due. Additionally, students in the control condition could send questions by email, to which the teacher responded within 1–3 days.

The teacher's task was to provide students with formative feedback in an automated-like mode, simulating an automated system. Although referred to as “automated feedback,” the feedback was in fact delivered manually by instructors who emulated automated responses. Some responses were scripted in advance to replicate the behavior of an automated support system. In the future, such feedback will be automated. All questions from students were collected for the future development of automated feedback design.

We conducted a survey at the end of each week to examine how students evaluated the two feedback conditions. Throughout the experiment, each student was asked to complete the survey four times. The questionnaire was available electronically on Moodle. Students answered the survey on a voluntary basis, and there were no penalties for not responding.

2.2.3 Instruments

To study the attitudes of students toward simulated automated formative feedback and support, we conducted a survey inspired by research (Bruck et al., 2012; Gómez et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2015). We utilized an abbreviated version of their questionnaire because not everything queried in it was ready (Supplementary Appendix A).

The questionnaire consists of four categories of questions:

• Learning approach

• Cognitive load

• Acceptance

• Learning influence

Each category contains 3, 6, 8, and 4 questions, respectively. All questions follow a 5-point Likert scale format, where students indicate their level of agreement or disagreement (from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). If a question could not be answered, students selected “0” and the question was excluded from the analysis.

The internal consistency of the measurement instruments was evaluated afterwards. Cronbach's alpha was 0.736 for the learning approach questionnaire, 0.813 for the cognitive load questionnaire, 0.824 for the acceptance scale, and 0.757 for the learning influence scale. For the entire questionnaire, it was 0.925.

Due to the rotating-group design, each student participated in both control and experimental conditions across the 4-week period. This within-subject structure allowed us to provide all students with equal learning conditions, keep the baseline competence constant, and control for individual differences. Accordingly, we did not include pre-intervention performance as a covariate. To account for repeated measures and inter-individual variability, linear mixed-effects models were applied, with random intercepts for students.

3 Results

In this section, we discuss the experimental results across four categories: learning approach, cognitive load imposed by simulated automated formative feedback, acceptance of context-aware simulated automated formative feedback, and learning influence.

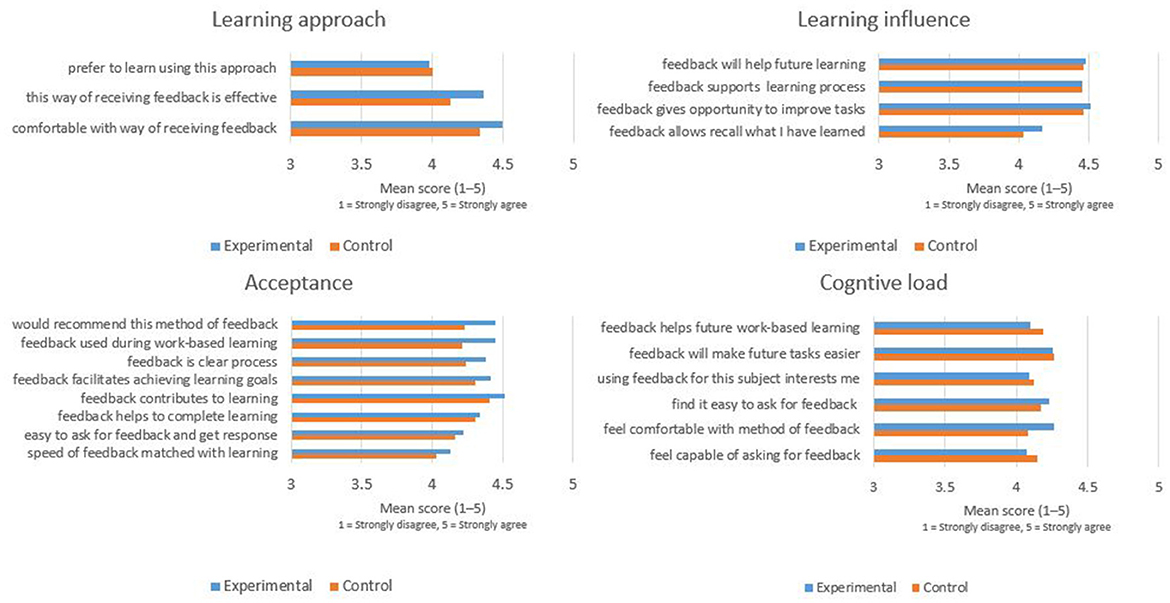

After the first week of the experiment, the total survey response rate was 58% (with 58% from the control group and 57% from the experimental group). In the second week, the overall response rate was 62% (with 66% from the control group and 50% from the experimental group). In the third and fourth weeks, the response rates were 57% (with 58% from the control group and 53% from the experimental group) and 52% (with 56% from the control group and 38% from the experimental group), respectively. In total, we received 43 responses related to simulated automated formative feedback and support (experimental condition) and 151 responses related to the traditional learning approach (control condition). The distribution of responses across four categories is shown for the two conditions in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Student perceptions across four dimensions—learning approach, learning influence, acceptance and cognitive load—for simulated automated formative feedback (blue) and traditional feedback (red). Results are based on a 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire.

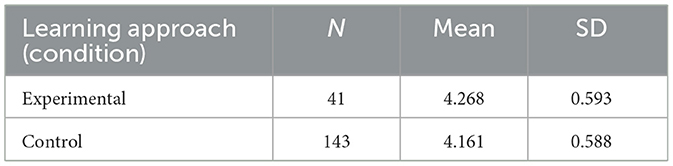

3.1 Learning approach

Students evaluated both learning approaches positively, with mean scores exceeding “4” across the three measured dimensions: comfort, effectiveness, and preference (see Figure 1). The experimental group reported a mean score of 4.27 (SD = 0.59), while the control group scored 4.16 (SD = 0.59), as shown in Table 1. Multilevel linear mixed model analyses with group and participant as random effects were performed to test whether students gave a higher rating for the learning approach in the experimental condition compared to the control condition. This was not the case, with F(1, 34.7) = 1.41, p = 0.243 and a small effect size (Cohen's d = 0.18).

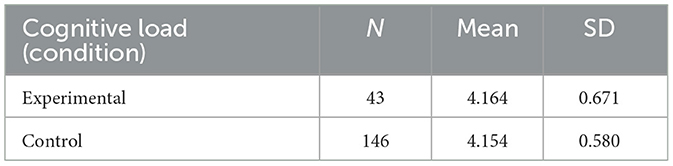

3.2 Cognitive load

The cognitive load scale aimed to assess the cognitive load experienced by the students. The mean score for the experimental condition was 4.16 (SD = 0.67), while the control condition scored a virtually identical 4.15 (SD = 0.58) (see Figure 1 and Table 2). No differences between the two conditions were found using the linear mixed model: F(1, 38.02) = 0.33, p = 0.569. These findings suggest that the simulated automated support and feedback did not impose additional cognitive load on the students in the experimental condition.

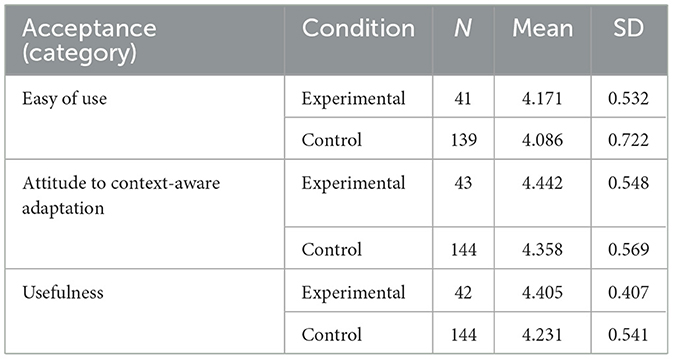

3.3 Acceptance

We analyzed acceptance in three categories: ease of use, attitude toward context-aware adaptation, and usefulness. The mean scores are shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. More specifically, the category “ease of use” consists of two items: one assessing “the response speed of the feedback” and the other evaluating “how easy it is to ask for feedback and receive responses.” Students rated both aspects positively, with an average score of 4.17 (SD = 0.53) on a scale of 5. These mean values indicate that participants found the system easy to use. Students also rated context awareness highly. They found that adapted feedback helped them complete learning activities based on their contextual information. Additionally, they agreed that associating feedback with real content contributed to their learning, with an average rating of 4.44 (SD = 0.55).

A slight difference was observed in the usefulness assessment, with students from the experimental condition giving higher ratings: the average ratings of simulated automated formative feedback and traditional feedback were 4.41 (SD = 0.41) and 4.23 (SD = 0.54), respectively. A linear mixed model analysis showed a significant difference between the experimental and control conditions: F(1, 48.9) = 5.07, p = 0.029. While the effect is small, it may suggest that simulated automated formative feedback (emulated in this study by instructors) is perceived by students as slightly more helpful in supporting their progress toward the learning goals. Students noted that requesting and receiving feedback through the system was a clearer and more structured process, which aided their understanding of both the content and the learning stages.

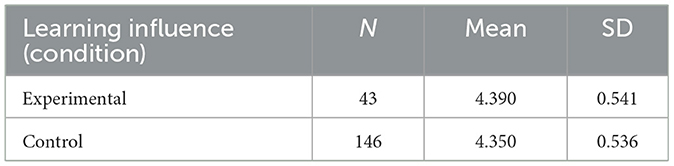

3.4 Learning influence

Analysis of learning influence shows that students perceive simulated automated formative feedback as giving them the opportunity to improve and redo tasks. They find that it helps them recall what they have learned and experienced, and they believe it will be beneficial in their future learning. The scores are shown in Figure 1 and in Table 4. The average ratings of simulated automated formative feedback and traditional feedback were 4.39 (SD = 0.08) and 4.35 (SD = 0.04), respectively. The difference between the experimental and control conditions was not significant: F(1,44.7) = 0.393, p = 0.543.

4 Discussion

The current pilot study explored the application of simulated automated formative feedback, emulated by instructors, on student perceptions and learning experiences in a project-based software engineering course. Survey responses indicated high overall satisfaction with feedback in both conditions. Overall, 93% of students reported that both the simulated automated formative feedback and the traditional feedback provided them with opportunities to improve and redo tasks. Additionally, 93% of students indicated that the simulated automated formative feedback supported their learning process, and 97% said the same of the traditional feedback. Furthermore, in both conditions, 95% of students agreed that the feedback—whether provided automatically or traditionally—would be beneficial for their future learning. These results suggest that students were generally satisfied with the feedback and support received, regardless of the method of delivery.

The only statistically significant difference between the two conditions was that students gave a slightly higher rating to the learning approach for simulated automated formative feedback than for traditional feedback; however, this effect was small. Taken together, these findings indicate the potential of simulated automated formative feedback to support student learning in project-based contexts, while maintaining quality, reducing teachers' workload, and avoiding additional cognitive load. Importantly, these conclusions apply to a simulated setting, and the effects of a fully implemented automated system may differ.

The results of our study can be contextualized within recent empirical research on the application of automated feedback in higher education. For example, Jia et al. (2022) conducted an experimental study on feedback for student software project reports and found that automated feedback significantly improved revision quality and student satisfaction.

4.1 Limitations and considerations

The within-participant design of our study optimizes statistical power and mitigates to some extent the limited sample size. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample was taken from one course at one university, which limits generalizability.

Second, response rates varied throughout the study period and across conditions, ranging from 52 to 62%. However, participation in the experimental group dropped sharply in the final week, reaching a low of just 38%. This decline likely reflects survey fatigue resulting from repeated data collection, raising concerns about potential non-response bias. Specifically, it is plausible that non-respondents were systematically less motivated or less satisfied, which could have skewed the results toward more favorable evaluations (Fass-Holmes, 2022).

As the same students participated in both the control and experimental conditions at different times, the risk of group-level bias was minimized. To mitigate the impact of non-response, linear mixed-effects models were employed, enabling robust estimation from incomplete data (Twisk et al., 2013). Nonetheless, some bias may remain if non-respondents differed systematically in motivation or satisfaction. Future studies should consider measures to increase response rates, such as incentives or mandatory completion protocols.

Third, while the rotating-group design allowed each student to serve as their own control, thus mitigating baseline competence variability, students were not fully randomly assigned due to the need to preserve team integrity in project work. This practical constraint may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of results.

Fourth, the “automated feedback” used in this study was entirely simulated by instructors using pre-defined templates and real-time responses. Although this approach effectively approximated a context-aware system, the lack of full automation limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding implementation scalability or system performance. The future deployment of truly automated feedback systems raises additional risks, such as ethical concerns, algorithmic bias, and data privacy issues—critical considerations when proposing AI-driven solutions in educational contexts. García-López et al. (2025) emphasize the need to develop comprehensive regulatory frameworks and pedagogical strategies to address critical ethical issues such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and educational inequity in the deployment of generative AI in education.

Fifth, instructors were not blind to group assignments due to the logistics of the rotating design. Although standardized feedback templates minimized potential bias, instructor bias cannot be completely ruled out (Wang and Han, 2022). This limitation should be addressed in future experimental designs through instructor blinding or peer-reviewed response protocols.

Furthermore, our study relied primarily on students' perceptions of feedback usefulness and learning influence. No objective indicators of learning effectiveness, such as project quality scores or exam performance, were included. As a result, the findings reflect attitudes rather than demonstrated performance. Future studies should triangulate self-reported data with objective performance outcomes (Gao et al., 2023). Given that most observed effects were small and statistically non-significant, our interpretations should be regarded as preliminary. The findings suggest that simulated automated formative feedback is at least not inferior to traditional feedback, but claims of superiority should be approached with caution.

Finally, the study captured only short-term effects within a single course at a single institution. Broader validation across multiple disciplines, course structures, and institutional contexts is necessary to assess generalizability and long-term impact. Further research involving multiple courses and curricula is required to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the role that AI-generated feedback plays in supporting student learning and academic development.

Despite the potential of AI to enhance educational measurement, researchers and practitioners must carefully consider its limitations, ethical challenges, and practical implications (Bulut et al., 2024). An informed understanding of these factors is crucial to prevent over-reliance, unquestioning trust, or misuse of AI technologies, especially in high-stakes educational settings where errors or biases can have significant consequences (Palumbo et al., 2024). The current study should therefore be interpreted as a pilot investigation that explores feasibility rather than providing definitive evidence of fully automated interventions.

4.2 Future work

The findings align with current educational trends. Students are often provided with project-based learning courses where software development projects should be completed in teams under academic supervision. Projects can be educational projects proposed by a teacher that are as close as possible to real-life conditions, or real projects proposed and implemented with industrial partners. Such projects are challenging for students due to their lack of practical experience, making timely support essential (Magana et al., 2023). They are also challenging for teachers, as providing individualized support to a large number of students requires a substantial time investment, which is often impractical. To meet these challenges, we are developing a context-aware system for learning and teaching that integrates mechanisms for student support and feedback.

In the next phases of our research, we will focus on applying automated feedback to 12–14-week capstone courses and industry-partnered real-world development projects. These longer and more complex assignments will allow us to test automated feedback scalability and adaptability to interdisciplinary requirements, where assessment criteria are often more dynamic and multi-layered.

Additionally, in the longer term, we will pursue several further research directions:

• Learner motivation and engagement analysis to evaluate the impact of automated feedback on learning dynamics

• Automated feedback adaptation for different academic disciplines (e.g., engineering, economics, natural sciences, and maritime studies at Tallinn University of Technology)

• Multilingual support development to assist learners in international and multicultural learning environments

• Longitudinal studies tracking the effects of automated feedback on learners' academic performance and metacognitive awareness over multiple semesters

By bringing together these developments, we aim to provide a comprehensive and well-considered framework that will shape future educational-technology practices and support the broader adoption of effective, ethically responsible AI-based feedback systems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study was conducted anonymously for the participants. All participants were informed that they were part of an experiment. Each participant had the option to withdraw from the experiment. The presented results do not include any personal data of the participants. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because the study was conducted anonymously for the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OS: Writing – review & editing. K-EK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JV: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. GP: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1621644/full#supplementary-material

References

Adorjan, A., and Solari, M. (2021). “Software engineering project-based learning in an up-to-date technological context,” in 2021 IEEE URUCON (Montevideo), 486–491. doi: 10.1109/URUCON53396.2021.9647348

Bruck, P. A., Motiwalla, L., and Foerster, F. (2012). “Mobile learning with microcontent: a framework and evaluation,” in BLED 2012 Proceedings (Bled: Association for Information Systems Electronic Library).

Bulut, O., Beiting-Parrish, M., Casabianca, J. M., Slater, S. C., Jiao, H., Song, D., et al. (2024). The rise of artificial intelligence in educational measurement: opportunities and ethical challenges. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv2406.18900. doi: 10.59863/MIQL7785

Ceh-Varela, E., Canto-Bonilla, C., and Duni, D. (2023). Application of project-based learning to a software engineering course in a hybrid class environment. Inf. Softw. Technol. 158:107189. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2023.107189

Fass-Holmes, B. (2022). Survey fatigue: what is its role in undergraduates' survey participation and response rates? J. Interdiscip. Stud. Educ. 11, 56–73.

Fioravanti, M. L., Sena, B., Paschoal, L. N., Silva, L. R., Allian, A. P., et al. (2018). “Integrating project based learning and project management for software engineering teaching: an experience report,” in Proceedings of the 49th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (New York, NY), 806–811. doi: 10.1145/3159450.3159599

Gao, N., Ananthan, S., Yu, C., Wang, Y., and Salim, F. D. (2023). Critiquing self-report practices for human mental and wellbeing computing at ubicomp. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv2311.15496. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2311.15496

García-López, I. M., Trujillo-Liñán, L., Joshua, M., and Tan, T. (2025). Ethical and regulatory challenges of Generative AI in education: a systematic review. Front. Educ. 10:1565938. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1565938

Gómez, S., Zervas, P., Sampson, D. G., and Fabregat, R. (2014). Context-aware adaptive and personalized mobile learning delivery supported by UoLmP. J. King Saud Univ. Inf. Sci. 26, 47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2013.10.008

Graham, R. (2018). The Global State of the Art in Engineering Education. Technical Report, Massachusetts Institute, Cambridge, MA, United States.

Ingale, S., Kulkarni, V., Patil, A., and Vibhute, S. (2024). Assessing the need for project-based learning: student engagement and outcomes in engineering disciplines. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 12, 4763–4771.

Jaber, A., Lechasseur, K., Mottakin, K., and Song, Z. (2023). “‘A study report in the web technologies course: what makes feedback effective for project-based learning?” in 2023 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition (Baltimore).

Jia, Q., Young, M., Xiao, Y., Cui, J., Liu, C., Rashid, P., et al. (2022). Automated feedback generation for student project reports: a data-driven approach. J. Educ. Data Min. 14, 132–161. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7304954

Langove, S.A., and Khan, A. (2024). Automated grading and feedback systems: reducing teacher workload and improving student performance. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 13, 202–212. doi: 10.62345/jads.2024.13.4.16

Luburić, N., Slivka, J., Dorić, L., Prokić, S., and Kovačević, A. (2024). A framework for designing software engineering project-based learning experiences based on the 4 C/ID model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 30, 1947–1977. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12882-x

Magana, A. J., Amuah, T., Aggrawal, S., and Patel, D. A. (2023). Teamwork dynamics in the context of large-size software development courses. Int. J. STEM Educ. 10, 57. doi: 10.1186/s40594-023-00451-6

Palmer, S., and Hall, W. (2011). An evaluation of a project-based learning initiative in engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 36, 357–365. doi: 10.1080/03043797.2011.593095

Palumbo, G., Carneiro, D., Alves, V., Wang, Z., Han, F., Bulut, O., et al. (2024). The rise of artificial intelligence in educational measurement: opportunities and ethical challenges. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 13, 1–21.

Rostom, M. (2019). Fostering students' autonomy: project-based learning as an instructional strategy. Int. E-J. Adv. Educ. 5, 194–199. doi: 10.18768/ijaedu.593503

Sembey, R., Hoda, R., and Grundy, J. (2024). Emerging technologies in higher education assessment and feedback practices: a systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 211:111988. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2024.111988

Subramaniam, S., Chua, F.-F., and Chan, G.-Y. (2017). Project-based learning for software engineering-an implementation framework. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. 9, 81–85.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 12, 257–285. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Sweller, J. (2020). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09701-3

Twisk, J., de Boer, M., de Vente, W., and Heymans, M. (2013). Multiple imputation of missing values was not necessary before performing a longitudinal mixed-model analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 66, 1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.017

Ulseth, R. R. (2016). “Development of pbl students as self-directed learners,” in 2016 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition (New Orleans, LO).

Wang, Z., and Han, F. (2022). The effects of teacher feedback and automated feedback on cognitive and psychological aspects of foreign language writing: a mixed-methods research. Front. Psychol. 13:909802. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.909802

Wu, P.-H., Hwang, G.-J., Su, L.-H., and Huang, Y.-M. (2012). A context-aware mobile learning system for supporting cognitive apprenticeships in nursing skills training. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 15, 223–236.

Keywords: project-based learning, context-aware learning system, teaching, higher education, feedback

Citation: Murtazin K, Shvets O, Karu K-E, Puusep V, Vendelin J, Meeter M and Piho G (2025) Student support during project-based learning using simulated automated formative feedback: an experimental evaluation. Front. Educ. 10:1621644. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1621644

Received: 01 May 2025; Revised: 01 November 2025;

Accepted: 18 November 2025; Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Anatoliy Markiv, King's College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mandeep Gill Sagoo, King's College London, United KingdomSyarifa Rafiqa, University of Borneo Tarakan, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Murtazin, Shvets, Karu, Puusep, Vendelin, Meeter and Piho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristina Murtazin, a3Jpc3RpbmEubXVydGF6aW5AdGFsdGVjaC5lZQ==

Kristina Murtazin

Kristina Murtazin Oleg Shvets

Oleg Shvets Karl-Erik Karu

Karl-Erik Karu Viljam Puusep

Viljam Puusep Jelena Vendelin

Jelena Vendelin Martijn Meeter

Martijn Meeter Gunnar Piho

Gunnar Piho