- 1Faculty of Education, Institute of Special and Inclusive Education, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

- 2Department of Education with a focus on Emotional and Social Development, Institute for Special Education, Europa-Universität Flensburg, Flensburg, Germany

- 3Department of Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

School attendance problems (SAPs) are a growing concern worldwide, particularly among students with social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties (SEBD), who are at elevated risk of school-related stress and disengagement. While much research has focused on the factors contributing to SAPs, effectively addressing these challenges requires insights into the viewpoints of those most affected and involved in school. This qualitative study explores commonalities and differences in the perspectives of students and school-based professionals regarding prevention-focused supports and interventions for SAPs related to SEBD across levels of support. Data were collected through focus groups with school-based professionals and individual interviews with students aged 15-16 in alternative and special education settings in Saxony (Germany). Qualitative content analysis was used to identify key support strategies and elements, which were then mapped across the levels of the Multi-Dimensional Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MD-MTSS) framework. The findings reveal that trust-based relationships, coordinated school-based care, flexible learning pathways, and clear communication were central strategies identified by both groups. At the same time, differences emerged at the level of intensive interventions. Professionals emphasized legal and procedural responses, while students stressed the need for emotionally responsive environments, reduced academic pressure, and having a voice in shaping their own reintegration process. The study underscores the value of participatory, context-sensitive approaches that integrate learning and mental health support to strengthen well-being and promote school attendance, especially among students with SEBD.

1 Introduction

School attendance problems (SAPs) represent a pervasive challenge across education systems worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have intensified this trend, with rising numbers of students experiencing attendance difficulties linked to both disrupted learning (Alejo et al., 2023; Dee, 2024) and heightened emotional distress (Benninger et al., 2022; Haddad and van Schalkwyk, 2021). Beyond individual consequences, SAPs pose risks for long-term educational and societal outcomes. Research links chronic absenteeism to lower academic achievement, reduced educational attainment, heightened psychosocial vulnerabilities, and increased dropout rates (Ansari and Pianta, 2019; Rogers et al., 2024; Yahaya et al., 2010).

The school environment plays a central role in children’s development, acting as both a source of support, and, at times, a source of stress (Bilz, 2023), influencing whether school attendance is promoted or hindered. Students with emotional difficulties – typically associated with internalizing behaviors – are particularly vulnerable to experiencing school as stressful, increasing the likelihood of developing SAPs (Hamilton, 2024; Lawrence et al., 2019; Lereya et al., 2022). A large body of literature has identified emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depressive disorders, as significant contributors to school absenteeism. Associated risk factors include bullying, punitive disciplinary approaches, strained teacher–student-relationships, academic difficulties, and family-related stressors (e.g., Egger et al., 2003; Finning and Dubicka, 2022; Gubbels et al., 2019; Havik et al., 2015; Tekin and Aydın, 2022). Emotional, social and behavioral difficulties are intertwined, compromising a person’s ability to cope and appropriately respond to situations, which in turn may undermine attendance through symptoms such as fatigue, concentration problems, or avoidance behaviors (O’Hagan et al., 2024; Panayiotou et al., 2021). In contrast, positive social-emotional experiences in school are associated with lower rates of absenteeism and fewer symptoms of anxiety, depression, and oppositional behavior among youth with attendance difficulties (Allison and Attisha, 2019; Hascher and Hagenauer, 2020; Hendron and Kearney, 2016; Korpershoek et al., 2020). It remains important to understand which supports are effective in improving student attendance, wellbeing, and a positive connection with education for this vulnerable group (Heyne et al., 2022, 2024). Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches have been demonstrated to reduce absenteeism and associated symptoms (e.g., Pina et al., 2009; Strömbeck et al., 2021). However, much of the current research centers on the effectiveness of intervention programs, with less attention paid to the lived experiences of students and professionals within everyday school contexts (Pérez-Marco et al., 2025).

Relatively little is known about student and school staff views regarding effective supports for improving school attendance. Qualitative inquiry into these perspectives can reveal both barriers and enabling factors related to addressing SAPs, thereby complementing the predominantly quantitative focus of existing research. For instance, youth perspectives stress the importance addressing the root causes of truancy and involving students in co-developing solutions (Gase et al., 2014), whereas educational practitioners tend to emphasize resource constraints and concentrate more on individual and family-related factors than on school-level contributors (Chian et al., 2024; Finning et al., 2018). Such divergent opinions can pose challenges for implementing collaborative, multi-faceted support systems. Input from key actors in the school environment is essential to developing of sustainable solutions to address SAPs (Heyne and Brouwer-Borghuis, 2022). Giving equal importance to the perspectives of school-based stakeholders helps reveal common facilitators to support attendance, while differences in their views can point to specific needs or obstacles to successful support. These insights are critical for informing the collaborative design of inclusive approaches to SAPs by bridging perspectives and fostering mutual understanding (Heyne, 2024).

The present research responds to this call by giving equal weight to the perspectives of both school-based professionals and students. The article presents findings from a qualitative study conducted in an alternative and a special school setting in Saxony (Germany). The study aimed to identify support strategies for the prevention and intervention of SAPs at multiple levels, based on the perspectives of students experiencing SAPs associated with social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties (SEBD) and the professionals who support them.

2 Theoretical foundations for understanding and addressing school attendance problems

2.1 Conceptualizing school attendance problems and social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties

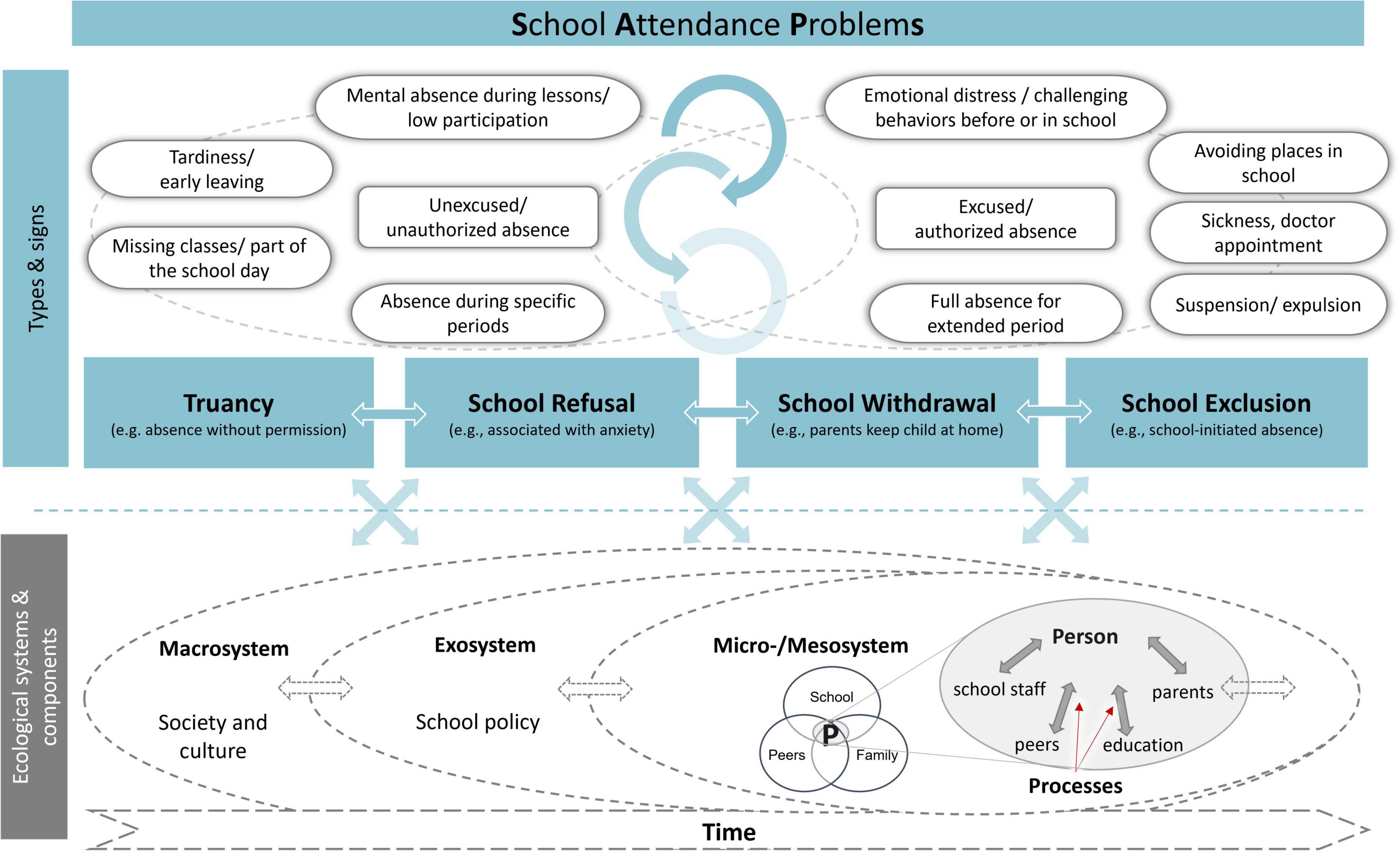

Concurrent concepts and definitions inform the present understanding of SAPs. This may be reflected in how professionals and students perceive the interplay of factors and supports they consider appropriate for promoting attendance. In line with the conceptual understanding of the International Network for School Attendance (Heyne et al., 2019a), this study uses SAPs as working term to describe a range of patterns and challenges that manifest in multiple forms, typically associated with difficulties in attending school or with absences that are considered problematic due to their frequency, duration, or underlying issues that interfere with learning and emotional or behavioral functioning (Kearney, 2021). In terms of broader categories, attendance policies and school laws often distinguish between unexcused absences (non-attendance without permission) and excused absences (valid reason, e.g., medical certificate) (Gottfried, 2009). Heyne et al. (2019b) provide an internationally recognized differentiation of SAPs, describing four prominent types: school refusal, truancy, school withdrawal, and school exclusion. This differentiation is made on the grounds of empirically substantiated primary causes and associated characteristics, e.g., school refusal mainly related to emotions like anxiety (Ricking, 2014). The concept behind SAPs shifts the focus from absence rooted in individual deficits to the problems experienced by students and their environment (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2020). Following, we advocate for an expanded, dimensional understanding that emphasizes fluid boundaries between the traditional categories as well as the flowing transition of patterns and signs of SAPs on a continuum: beginning with full attendance, emotional distress before and/or during school, tardiness through to hourly or complete absences (Kearney et al., 2019; Kearney and Gonzálvez, 2022; Kearney, 2021). These signs may indicate that a student experiences SAPs.

Along these lines, SAPs are understood as systemic, multidimensional phenomenon, influenced by the dynamic interplay of proximal and distal risk and protective factors across ecological systems (Gren Landell, 2021; Melvin et al., 2019). These factors can exert both an initiating and a maintaining effect, and they are not unidirectionally related to specific types or signs. Rather, they interact in a compounding, multidirectional manner, thereby increasing the risk of SAPs (Kearney, 2021). Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) bioecological theory offers a valuable framework for describing these complex interrelations between system levels, encompassing the Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model. It outlines four fundamental components that influence a child’s individual development: the person engages in (proximal) processes (e.g., typically occurring everyday activities and interpersonal interactions with people, symbols, and objects) within its immediate environment (e.g., microsystem school) in interaction with other contexts (meso-, exo-, and macrosystems) over time (also known as the chronosystem) (Rosa and Tudge, 2013; Tong and An, 2024; Tudge, 2008).

Figure 1 reflects the four types (Heyne et al., 2019b) and manifestations or signs (e.g., observable behaviors/patterns) (Kearney, 2016; Kearney et al., 2019; Ricking, 2014) alongside the interrelated ecological systems and PPCT components (Melvin et al., 2019; Tong and An, 2024; Tudge, 2008) as underlying mechanisms in the development of SAPs over time. The outwarded arrows symbolize the multidirectional and multifactorial interplay of factors in the emergence and persistence of SAPs.

Figure 1. Types, signs, ecological systems, and components in relation to SAPs, self-created figure – guided by Heyne et al. (2019b); Kearney (2016) 2021, Ricking (2014); Melvin et al. (2019), Tong and An (2024), and Tudge (2008). Translated from German, published in adapted version in Enderle (2025a), in print.

In this research, the term social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties (SEBD) is adopted to describe the multifaceted social, emotional, and behavioral mental health needs that act as barriers to young learners’ personal, social, cognitive, and emotional development in various social contexts, including the classroom and school (de Leeuw et al., 2018; Müller, 2021). In the literature, labels such as Emotionally Based School Avoidance (EBSA) (West Sussex Guidance, 2020) or school refusal are frequently used to describe situations in which emotional distress or heightened anxiety are connected to absence (Shilvock, 2010). Subsequently, we consider SAPs related to SEBD as contexts and/or situations in which young learners experience distress and challenges that disrupt their relationship with education and impact their ability to attend school. These challenges are rooted in dynamic person–environment interactions and are typically accompanied by, or expressed through, observable emotional and behavioral symptoms. Such symptoms may manifest as internalizing behaviors, such as anxiety and depression, which are often associated with school refusal (Egger et al., 2003; Tekin and Aydın, 2022), and/or externalizing behaviors, including disinterest, boredom, hyperactivity, or disruptive behaviors, commonly linked to truancy (Havik and Ingul, 2021). From this interactionist standpoint, the overt manifestations of all SAPs types can be understood as stress responses influenced by a combination of internal and external factors that onset or maintain difficulties (Peeters et al., 2025).

2.2 The multi-dimensional multi-tiered system of supports as a central framework for supporting school attendance

The multi-dimensional multi-tiered system of supports (MD-MTSS) framework is known as integrated, tiered approach to organizing supports for SAPs at levels of intensity, depending on students’ complex and evolving needs (Kearney and Graczyk, 2014, 2020). The framework is rooted in a whole-child (Goldberg et al., 2019) and ecological systems perspective, thereby connecting well with the multi-systemic and interactionist perspective outlined above for addressing SAPs in the context of SEBD. In this study, the MD-MTSS serves as central theoretical framework to explore attendance-related support strategies and elements, as identified by both students experiencing SAPs and the professionals who support them.

The MD-MTSS structures supports in three basic tiers (Kearney, 2016; Kearney and Graczyk, 2022; Kearney and Graczyk, 2020). Tier 1 (universal) focuses on school-wide supports designed to promote the functioning and positive conditions for school attendance for all students. These strategies are implemented proactively to support the whole school community. Tier 2 (targeted) focuses on students who exhibit emerging signs of attendance issues or other risk factors for SAPs. The goal of strategies at this level is to reduce absence and address emerging SAPs in a more reactive manner. Tier 3 (intensive) comprises intensified interventions for students experiencing severe or chronic absence (e.g., high proportion of absence relative to attendance) and/or complex social, emotional, and behavioral needs with the goal to manage underlying causes of their SAPs through coordinated, individualized support (Heyne, 2024).

The three-dimensional or pyramidal structure facilitates the simultaneous addressing of multiple domains, including the academic, behavioral, social, emotional, and contextual dimensions of school attendance. This is achieved through a tiered continuum of supports that are responsive and tailored to students’ varying levels of need (Graczyk and Kearney, 2023; Kearney and Graczyk, 2020; White, 2022). The MD-MTSS model recognizes that students’ SAPs occur along a continuum (e.g., severity) and differ from student to student (e.g., types of attendance problems) (Kearney, 2016). Furthermore, the framework addresses systems as well as student groups alongside individual students (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020).

Overall, the MTSS-based model of school attendance can be blended and complemented with similar MTSS-approaches and interventions, for example, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Social Emotional Learning (SEL) (Cook et al., 2015; Horner et al., 2010). Systemic resilience-based practices are compatible as well with the aim of enhancing students’ ability and fostering positive conditions for school attendance (Enderle et al., 2024). The Protective Processes and Promotive Factors model by Ungar and Theron (2020), for example, offers aspects and practices from resilience research that focus on factors to promote positive outcomes among psychosocially vulnerable youths. Integrating components from resilience frameworks to school attendance may enhance the overall impact and outcome of tiered interventions for school attendance (Dray et al., 2017; Ungar et al., 2019).

One of the guiding principles of a multi-tiered prevention framework is the use of evidence-based, practices to reduce the likelihood of difficulties and to enhance positive outcomes in various domains of student achievement, social and emotional learning, positive behaviors or engagement (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 2014; Stoiber and Gettinger, 2016). This is achieved through data-driven decision making to match support to students at specific levels of need. Accordingly, monitoring of attendance data is central to the MD-MTSS framework, extended to the assessment of contextual variables and data in multiple domains of functioning (Kearney and Graczyk, 2022; Kearney and Graczyk, 2020; Ricking, 2014).

Finally, the MD-MTSS provides a flexible and theoretically grounded framework for delineating practices and supports that are critical to the prevention and intervention of SAPs from the perspectives of students and professionals that can be leveraged to inform the implementation of an integrated approach into existing school structures.

3 Earlier research on student and professional perspectives

Capturing the voices of multiple stakeholders is essential to gain a comprehensive understanding into the complex dynamics of SAPs related to SEBD as well as the effectiveness of prevention and intervention measures targeting these challenges. Overall, some reviews have provided a more comprehensive overview of studies focusing on different actors’ views concerning SAPs. A recent qualitative synthesis identified a body of literature in the Nordic countries that includes 11 studies exploring the perspectives of children and adolescents and 8 studies examining the views of school staff (Hejl et al., 2024). Corcoran and Kelly (2023) provide a meta-review on lived experiences of school non-attenders in the United Kingdom. Another systematic review highlights professionals’ attitudes toward SAPs from international quantitative and qualitative research (Hamadi et al., 2024). Existing research shows that both youth and school professionals recognize the multifaceted origins of SAPs, including individual, social, and contextual factors (e.g., Hejl et al., 2024; O’Toole and Æiriæ, 2024), and express the need for systemic, tailored interventions that involve families, schools, and mental health professionals (e.g., Chian et al., 2024; Finning et al., 2018; Gase et al., 2014). Predominantly, the themes emerging from qualitative studies focus on perceptions surrounding the determinants of SAPs and/or barriers to addressing them (e.g., Melander et al., 2022; Oehme, 2007; Richards and Clark-Howard, 2023). Comparatively less attention is given to the working elements that underpin successful returns or improvement of school attendance (e.g., Halligan and Cryer, 2022; Heyne and Brouwer-Borghuis, 2022). Despite this, some reviews and qualitative studies focus on the experiences of stakeholders in alternative education settings or intervention programs to investigate successful support practices and protective elements in these contexts (Halligan and Cryer, 2022; Heckner, 2013; Heyne and Brouwer-Borghuis, 2022; McKay-Brown and Birioukov-Brant, 2021; Sundelin et al., 2023; Walther-Hansen et al., 2024).

Previous qualitative studies conducted on student perspectives offer important insights into attendance-enabling elements at the student- and context-levels. These include individual supports (Halligan and Cryer, 2022; Hejl et al., 2024; Flynn et al., 2024), positive class climate, supportive relationships with peers and teachers, structured, safe, or adapted learning environments (Chian et al., 2024; Corcoran and Kelly, 2023; Enderle et al., 2024; Gase et al., 2014; Heyne et al., 2021; Sundelin et al., 2023; Walther-Hansen et al., 2024), alongside family involvement and individual factors, such as motivation and hope (Enderle et al., 2024; Heckner, 2013; Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Walther-Hansen et al., 2024).

In studies focused on professional perspectives, systemic and organizational aspects, such as team-based approaches, resource allocation, and interdisciplinary collaboration are frequently highlighted (Dennis, 2020; Finning et al., 2018; Melander et al., 2022; Nuttall and Woods, 2013; O’Toole and Æiriæ, 2024). In addition, relational and pedagogical approaches include supporting positive relationships and wellbeing, home-school collaboration and flexible, adjusted teaching (Devenney and O’Toole, 2021; Finning et al., 2018; Halligan and Cryer, 2022; Hejl et al., 2024; Martin et al., 2020; McDonald et al., 2023; Nuttall and Woods, 2013, 2013; O’Toole and Æiriæ, 2024).

However, much of the existing qualitative research on SAPs focuses on single-informant approaches and interventions (e.g., Keppens and Spruyt, 2020), with few studies considering the perspectives of multiple groups, such as students and school staff, simultaneously (Chian et al., 2024). Furthermore, while prior research highlights barriers and facilitators in the management of SAPs, there is a need to explore the experiences of these groups regarding supportive factors and effective strategies for prevention and intervention, with a focus on the interplay between mental health and attendance.

4 Aim and research questions

This article responds to the outlined gaps in concurrent research, particularly the limited amount of qualitative research on supports and protective factors for SAPs related to SEBD from multiple perspectives in the German context. The aim of the present study is to explore the perspectives of (a) students with SEBD and (b) school-based professionals on support practices and elements they consider effective and appropriate in the prevention and intervention of SAPs. The following research questions guide the study:

- RQ1: What do students and school-based professionals perceive as effective supports for the prevention and intervention of SAPs associated with SEBD?

- RQ2: How can key support strategies and elements be filtered and mapped in relation to the levels of the MTSS framework?

- RQ3: What commonalities and differences emerge in the supports identified by both groups for the prevention and intervention of SAPs?

In addressing these questions, we aim to focus on commonalities and differences between both groups, considering the support levels (universal, targeted, or intensive). This inclusive approach enables a deeper understanding of shared attendance-enablers and working elements across levels (Peeters et al., 2025), while also identifying points of divergence that reveal unmet needs or gaps that require more nuanced, collaborative solutions in these specific contexts. Ultimately, this approach can inform the translation of qualitative insights into practical applications and policy development.

5 Materials and methods

5.1 Context of study

This study is part of a larger international research project SAPIC (International Comparative Perspectives on School Attendance Problems: Analysis of statistics, risk groups and prevention in four countries) (Kreitz-Sandberg et al., 2021) based on quantitative large-scale data and qualitative studies across Sweden, the UK, Germany and Japan (Fredriksson et al., 2023, 2024; Kreitz-Sandberg et al., 2022). In the qualitative part, interviews were conducted with school leaders, teachers, and other support professionals as well as youths to understand their views on support systems related to SAPs in these countries. This article specifically draws on focus group interviews with teachers and support professionals and individual interviews with students at secondary school level aged 15–16 in rural and urban areas of Saxony, Germany. Subsequently, we generally refer to these groups as (school-based) professionals and students.

5.2 Ethical considerations

The data collection was approved by the Saxony State Office for School and Education (Landesamt für Schule und Bildung, LaSuB) on October 17, 2023. (R15-6490t6t220-20231135214) before conducting the study. The data were handled in accordance with the GDPR (DSGVO) and the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority has approved the project design of SAPIC (Dnr 2020-05441, Linköping department, Decision 24.11. 2020). To ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of both the schools and the participants involved in this study, the exact locations and setting of data collection cannot be disclosed.

5.3 Study design and procedure

Focusing on the qualitative case study, interviews with 11 school-based professionals in three focus groups and 11 individual student interviews were conducted in an alternative and a special education setting in Saxony, Germany, as a follow-up to the case study conducted in Hamburg (Enderle et al., 2024).

The focus group interviews involved special and mainstream education teachers, career changers to teaching and social workers from a special education center and a Productive Learning (PL) program. The student participants were of compulsory schooling age, with some enrolled in an alternative learning setting (referred to as PL program) where students have made progress in terms of attendance at the time of the study. The intention was to apply a strength-based perspective for the purpose of understanding what support measures and elements were perceived as effective by students in overcoming SAPs.

In the recruitment, the research team used a snow-balling strategy (Friebertshäuser et al., 2013) by contacting several secondary schools, a special education center and an organization serving young learners with SAPs and their families via email in the urban and rural areas of Saxony. The majority of schools contacted were secondary schools, with two of them offering the PL program as part of their school profile. For schools expressing interest in participating, further details were clarified via phone calls or email exchanges. Additionally, study information and consent forms were distributed in simplified language versions to enhance accessibility and understanding for students. Within the recruitment process, the study relied on responses from schools. The scope of the collected material was dependent on the voluntary participation and consent of the individuals involved. In the case where schools confirmed their participation, teaching staff was asked to identify potential students in the age range of 15–17, who have experienced SAPs in the mainstream school setting. The schools were provided with the information letter, informed consent form, and several interview appointments options. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the guardians of students, who were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary, their data would be kept confidential, and they could stop participating in the study at any time without any negative consequences. The students were interviewed individually in separate rooms at school to capture their personal experiences and perspectives on overcoming SAPs.

The study used a semi-structured interview guide for individual and focus group interviews which has been tested in an earlier qualitative case study (Enderle et al., 2024). The thematic focus in students’ interviews was directed toward their previous experiences and facilitating or hindering factors to their SAPs (e.g., what challenges have you experienced related to school attendance?). Furthermore, the students were asked to provide advice to schools, parents, or guardians regarding what they perceived as helpful support measures. To ensure suitability, minor modifications were made to some questions to improve their relevance in the specific context of PL. Further, the interview guide developed for the focus groups involved questions about what support systems are implemented to promote regular school attendance and address issues related to SAPs as well as barriers and opportunities within existing support systems. The interviews were conducted in German from April to June 2024. Before commencing the interviews, the researchers explained the aim and background of the study. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and pseudonymized (Dresing and Pehl, 2018). The individual student interviews took approximately 16–32 min. The focus group interviews lasted between 50 and 68 min. The first author (female, doctoral researcher) and two student assistants (Masters level, special education teacher program) from the project team conducted the interviews.

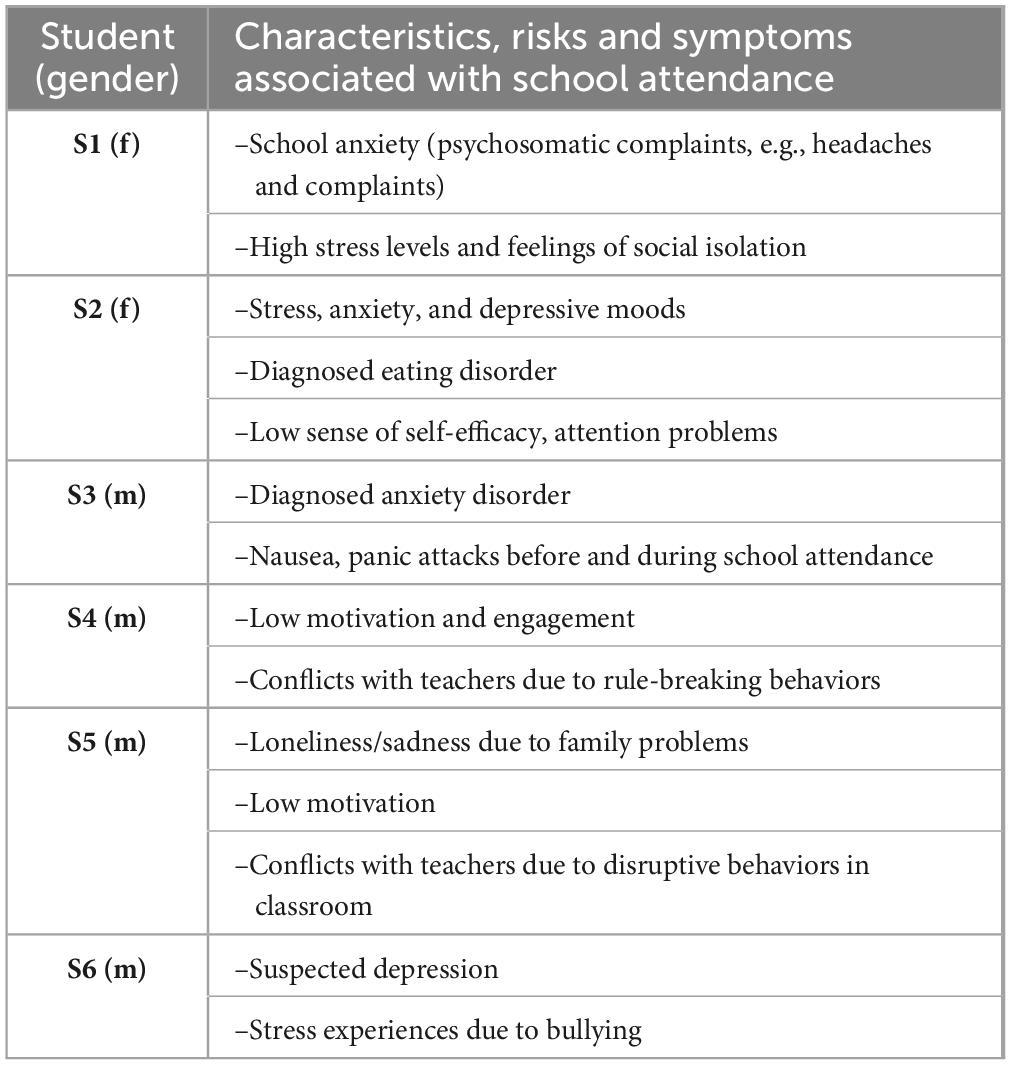

5.4 Participants

Initially, our aim was to include all 11 student interviews in the analysis, but related to the article’s objective, students who reported having SEBD were selected. One student had special educational needs in emotional and social development. Throughout an initial review of the data, a final sample of n = 6 was deemed sufficient for data saturation to illustrate diverse student perspectives according to their reported SEBD and school experience (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022). Four youths attended the PL program and two youths attended different secondary schools (Oberschule) in an urban area. Two students identified as female. All students showed an improvement in attendance at the time of the study. Table 1 displays the students’ characteristics in terms of reported SEBD, particularly internalizing and/or externalizing behaviors (Enderle, 2025a). Central risk factors and challenges are also reflected that either led to the onset or maintenance of students’ SAPs (Enderle, 2025b). This allows for a better understanding of students’ perspectives in the context of SEBD.

Table 1. Student participants’ characteristics, reported risks, and symptoms associated with school attendance.

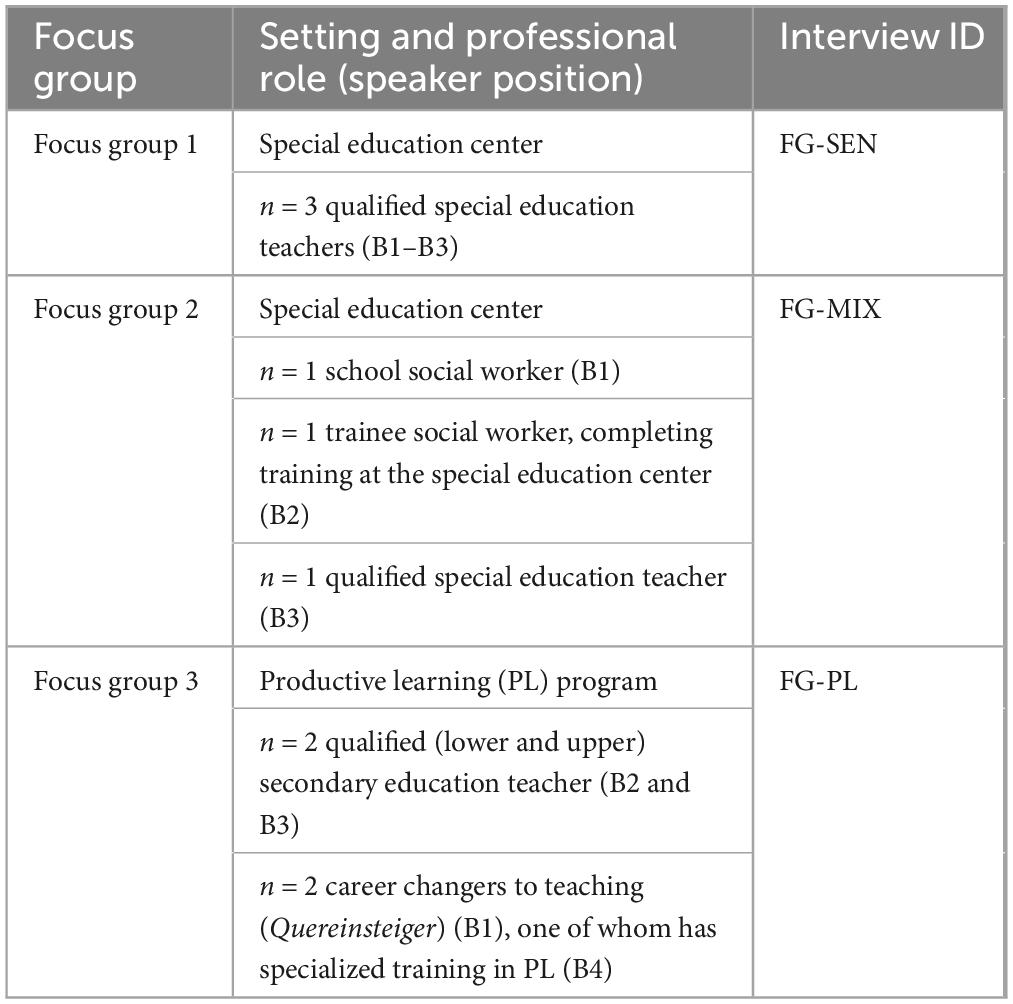

The final sample of school-based professionals includes n = 10 individuals – employed as teachers or other support professionals – who were interviewed in three focus groups. The first two focus groups took place in a special education center for students with emotional and behavioral needs (Grades 1–6). The school is situated in a rural area in Saxony. The third interview was conducted in the building of the PL program. The setting and professional roles of focus group participants are summarized in Table 2. The interview IDs used in the table and quotations are fictitious.

5.5 The educational context – Saxony in Germany

To better understand the educational environment and its influence on the participants’ experiences, it is essential to consider the educational context in Saxony (Germany). This context provides the structural and systemic background for the alternative school settings and special schools involved in the study. In Germany, compulsory education requires all children from the age of six to attend a public or state-approved school for 12 years: this often includes 9 years of full-time schooling at general education schools plus 3 years at a full-time general school or part-time at a vocational upper secondary school (Eurydice, 2025).

The education system in Saxony encompasses a wide range of school types and institutions, such as primary school (Grundschule), secondary school (Oberschule), grammar school (Gymnasium), vocational schools (Berufsbildende Schule), and adult education centers offering second-chance qualifications for general education degrees (Schulen des zweiten Bildungswegs). Saxony has one of the highest rates of students attending special schools (KMK [Standing Conference for the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs], 2024). Students with disabilities, including emotional and behavioral problems, are supported in special needs schools (Förderschule) through targeted support and individualized adjustments. Special schools focused on supporting emotional and social development usually encompass years 1–4, after which the students usually continue their education at mainstream schools. The region supports the special education offer, called Productive Learning (PL). It provides flexible and practice-oriented curricula to a tailored target group of students in grades 8 and 9 within the lower secondary school track. It is aimed at supporting students who struggle in mainstream settings of compulsory school to acquire the lowest school-leaving qualification with entrance qualification to a vocational school and/or become prepared for specific career and educational pathways at the end of year 9 (SMK, 2020). Additionally, interested students have to apply for the program and undergo an admission process. The program involves a modified timetable, linking practical experience with school-based education. Students spend 13 h per week learning in school (core subjects and interdisciplinary topics) and 20 h at a practical learning site (e.g., business, government agency, and cultural or social organization). Teachers working in the PL setting participate in a 3-year professional development program offered by the Institute for PL in Europe (IPLE e. V.) (IPLE, 2025). The PL has many common organizational features with special schools: individual learning plans, adjustment/adapted instruction, small teaching groups and high density of school staff.

These settings play a critical role in accommodating students at risk of academic disengagement, including those who participated in this study. By situating the research in specialized educational contexts, it can capture supportive strategies designed for students who are at higher risk of SAPs in terms of understanding protective factors in these settings.

5.6 Data analysis

In line with the scope of this article, we applied qualitative content analysis following Kuckartz’s methodology (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2022). This method enables a detailed exploration and comparative analysis of aspects perceived and expressed by the participants as supportive in addressing SAPs.

The data were coded individually by student assistants, then peer-checked, and reviewed by the lead researcher in consensus discussions. In an explorative step of the coding process, relevant text passages in the transcriptions were identified in which students or school-based professionals refer to supports, aimed at promoting attendance, preventing and reducing SAPs. Both statements about elements of (school-based) support as well as rather implicit perceptions of support and engaging factors that counteracted the development of SAPs were included. These meaning-carry units were condensed, abstracted into codes and organized into topics. The sorted codes served as the basis for developing thematic main and subcategories. The analysis primarily follows an inductive approach, meaning that categories are developed from the material. Kuckartz and Rädiker (2022) emphasize that the inductive process is inherently linked to an active, reflective engagement with the material and the researcher’s prior knowledge. Using a deductive approach, the coded units were further examined in connection with theory and literature to organize supports into prevention (Tier 1) and interventions (Tier 2 and 3) (Kearney and Graczyk, 2022), thereby minimizing potential bias. As such, supports aimed at preventing SAPs or social-emotional difficulties as well as proactively promoting attendance were categorized as prevention-focused support. The efforts focused on reducing SAPs or other risk factors fall under the category of interventions. Sufficient saturation was considered as no new codes emerged. The identified main categories with corresponding subcategories were organized in hierarchical order. The category system provides a framework for systematically organizing the content, allowing for conclusions to be drawn or comparisons to be made (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2022). The material was revisited by applying the category system which resulted in minor modifications of coded units. Subsequently, two different sets of category matrices emerged for each respondent group and the focus of supports, one with prevention-focused support and one with focus on interventions. The members of the coding team were involved in thorough discussions and reflections to further refine the categories. This included a documentation of the codes and critical dialogues around the specific terminology of categories until consensus was reached.

As a final step in addressing RQ2 and RQ3, the analysis focused on identifying pedagogically relevant strategies and elements from the categories on prevention-focused supports and interventions. The coded sections in the respective categories were scanned to filter concrete actions and elements that reflect different levels of pedagogical response. The identified key support strategies and elements were then systematically organized within the multi-tiered framework: elements filtered from the prevention-focused categories were assigned to Tier 1 (universal). In the filtering of interventions, strategies designed to support students showing early signs of SAPs and/or SEBD were mapped as Tier 2 (targeted), while actions addressing chronic absenteeism or more severe challenges were classified under Tier 3 (intensive).

For the preparation and processing of the interview data, the computer-assisted software MAXQDA 2024 was used (VERBI Software, 2024). The study was conducted in line with the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007; see Supplementary Material 1). The student interviews have been previously analyzed and presented independently, using a different methodological approach and research focus.

6 Findings

The findings for RQ1 are first presented separately for the group of students and professionals, distinguishing between prevention-focused supports and interventions. The extracted key support strategies and elements for RQ2 are then presented across the tiers of the MTSS framework.

For clarity, only the main categories are presented. Direct excerpts and paraphrased quotes are used to illustrate the subcategories and support the main categories. The exemplary quotations have been translated from German using a language translation tool, and the translations were reviewed by the authors for accuracy. The original excerpts, in their numerical order of appearance, can be found in Supplementary Material 2.

6.1 Student perspectives

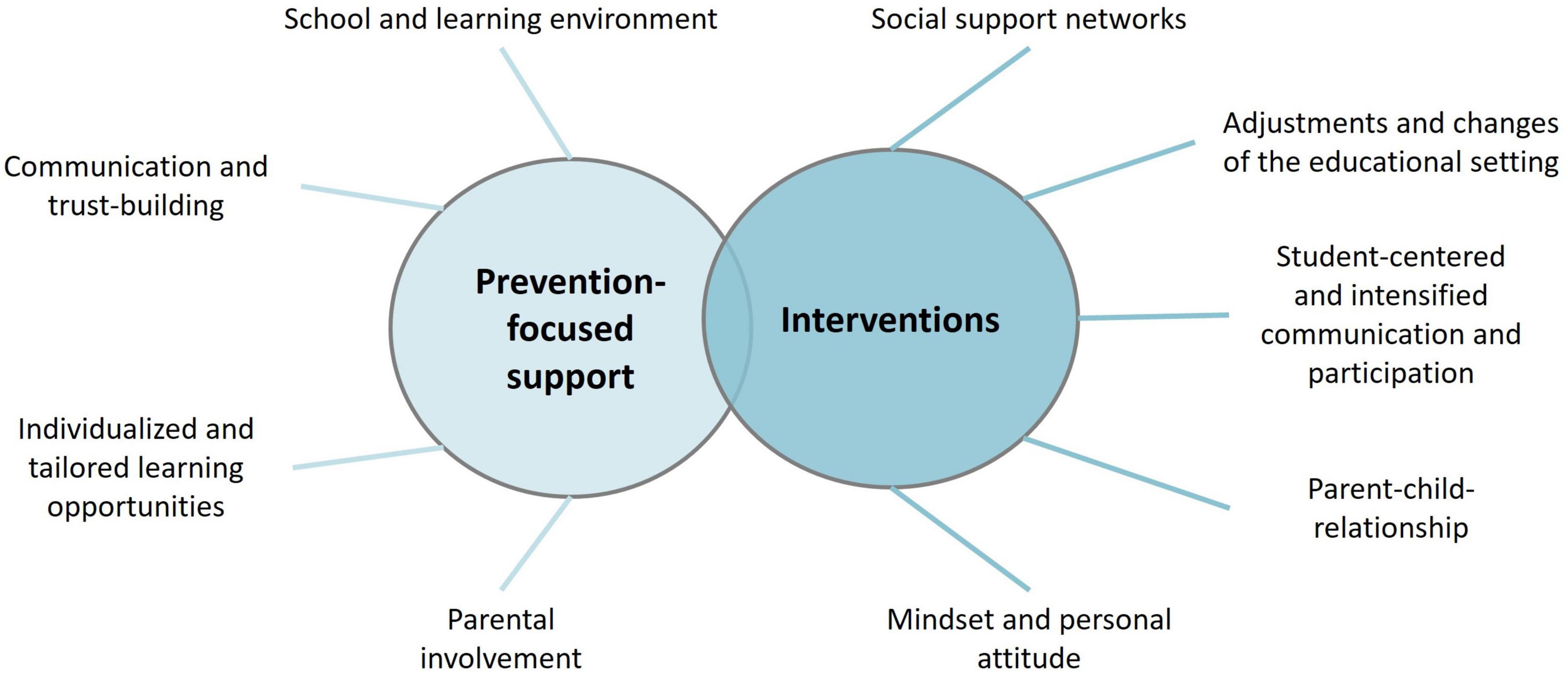

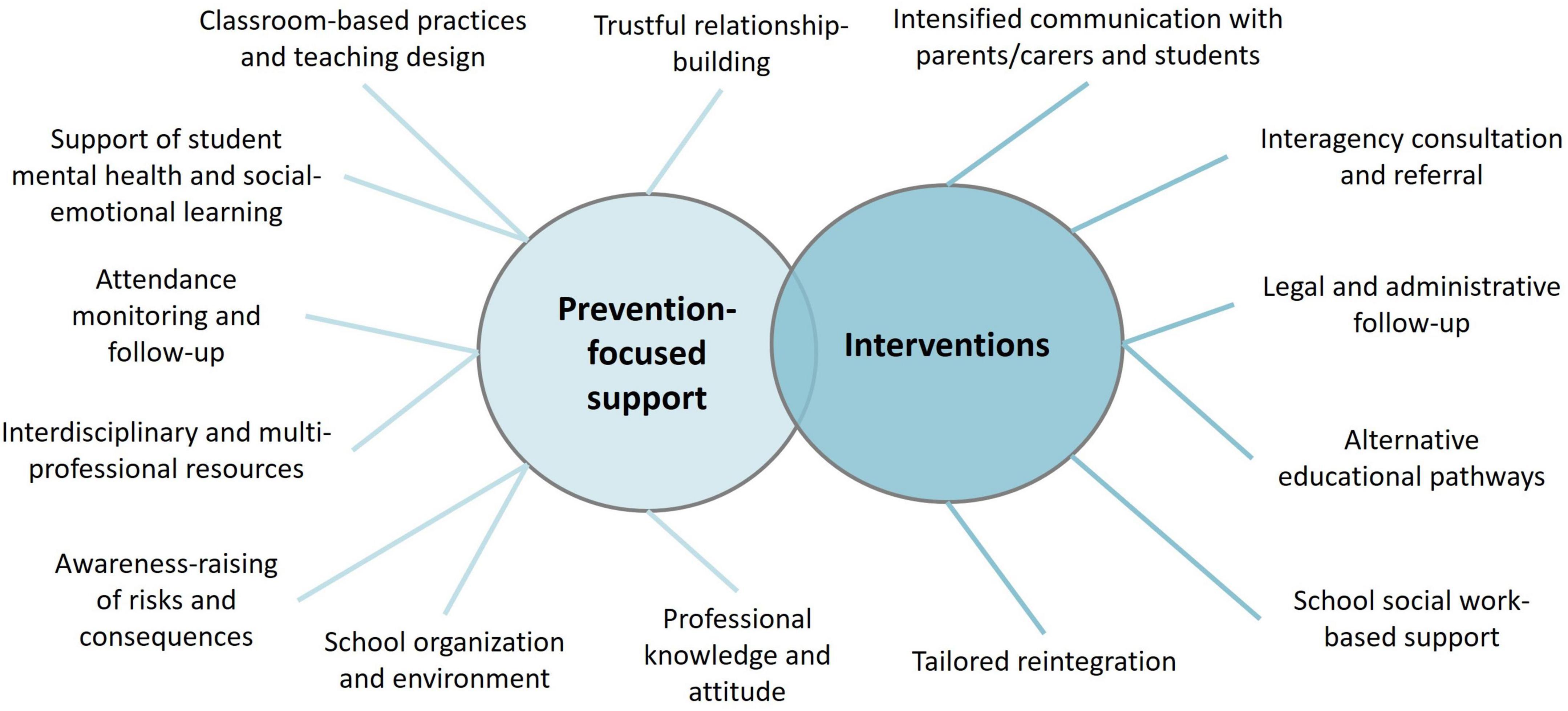

Students identified several strategies they found effective in preventing SAPs and supporting re-engagement during emotional distress or after extended absences. The categories for the respondent group of students are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Overview of categories of prevention-focused supports and interventions for the respondent group of students.

6.1.1 Prevention-focused supports

Students highlighted the importance of an engaging, flexible and structured school and learning environment to support their emotional wellbeing. The students talked about the role of learning content and subjects.

“The war in Ukraine or what’s going on in Gaza” (S5).

“That small subjects like art (…) that are more practical subjects (…), should be given more attention” (S4).

These preferences reflect a desire for a meaningful, varied, and joyful school experiences. At the same time, the lack of supportive structures was also mentioned as a stressor: As one student put it:

“I would say that students tend to get overlooked there and that some (…) [as a result] feel overwhelmed (…) and then you cannot really respond to their needs [as a professional]” (S3).

Communication and trust-building was seen as a foundational element for preventing SAPs. This included open and respectful dialogue, addressing problems early, and building trust-based relationships between students, teachers, and parents. One student reflected on the consequences of poor communication:

“The very first advice I would give for everyone – for students, teachers, and parents – is that communication is actually the most important thing. I realized that for myself. There was a serious lack of communication” (S3).

Another echoed the value of connection for school belonging:

“I don’t think anyone wants to go somewhere where there is no [social] cohesion or trust.” (S1).

Under the category individualized and tailored learning opportunities, students valued, for example, support that provided space for conversations.

“There should be one-to-one conversations with the students, (…) so you can respond to the student and see what might be going wrong at school or in the classroom” (S3).

This quote illustrates a desire for individual recognition of difficulties early on and responsive adults who identify issues early and adjust learning arrangements accordingly before they escalate.

Students perceived parental involvement in school life as a resource to prevent SAPs and support them holistically. As one student noted:

“Parents should be more involved. (…) It also helps because, of course, a student doesn’t always have a full overview of everything [that is going on]” (S3).

6.1.2 Interventions

With regard to interventions, students referred to social support networks, emphasizing the value of feeling understood and supported by people whom they trust—peers, teachers, family members, therapists. Social support within and beyond the school setting was perceived as meaningful in navigating emotionally difficult phases and reducing feelings of isolation. One student mentioned the peer group as a shared space of support:

“My group helped me a lot too (…). We were all kind of in the same boat and had relatively similar problems, and hearing each other’s perspectives really helped” (S3).

The group context seemed to offer recognition and shared experience, which appeared to ease emotional strain and promote re-engagement. In addition to informal networks, students highlighted the value of professional psychological support that played a different and complementary role, particularly in addressing persistent emotional problems:

“I mean, talking to friends, family, and people you trust is great, and you can also get advice. But it’s still different when you talk to professionals” (S3).

In parallel, some students described the need for a reflective, responsive and gentle approach from school professionals in encouraging attendance — a balance between understanding and confrontation.

“I think I might have needed a little push when I wasn’t showing up that often at the beginning. Something a bit stricter and not just ‘Ah well, that’s okay’, because I think that brought me a bit into the cycle, thinking it was fine to just stay home.” (S1).

Students spoke about adjustments and changes in their schooling that made it easier for them to return or stay engaged. These included shifting to smaller learning groups, lower academic expectations and/or pressure, or entering programs like PL. The altered setting often brought relief from pressure and led to more positive learning experiences. Several students referenced the importance of practice-based learning formats and informal connections with staff, suggesting that the learning environment felt different from their prior experiences.

“Here, we do things in a practical format, and I like that better. (…) I like learning in a playful way – doing things differently, instead of just listening and writing” (S4).

“When I had a good day [at my internship], it boosted my self-confidence a little, and that made it easier for me to go [to school] (…). Yes, it just gave me a little energy boost” (S4).

Some students also mentioned clinic schools or reintegration programs that supported their return:

“We had breakfast together (…), and it felt more like (…) being part of a second family, which definitely made it easier to go there regularly” (S6).

These programs appeared to create emotionally safe, low-pressure environments where students could re-establish routines and rebuild confidence.

Students pointed to student-centered and intensified communication and participation as something that shaped their ability to reconnect with school, especially when it included direct conversations between them, staff, and family. While communication was sometimes described as lacking, moments of contact were remembered and described in detail. This highlights how even small, consistent interactions can have a meaningful emotional impact. One student stated:

“Well, I did have some hope when my teacher talked to me” (S2).

Another student reflected on the need for more direct involvement, rather than being spoken about:

“Definitely talk to me too (…). I missed that a bit at my last school. It’s frustrating when I have to tell [my mum] everything and then she passes it on to others – I could just join [the conversation] because it’s also about me” (S1).

Students appreciated when they were given a say in planning their re-entry and educational goals:

“They actually asked me, well, ‘how do you imagine it?’ and really talked with me about my goals, how they could plan it out, and how they could help me achieve them. I think that helped a lot.” (S1).

These comments highlight how students experienced communication — both its presence and absence — as something that mattered in their return to school when struggling with SAPs and/or SEBD.

In their accounts, students also described parent–child relationship dynamics, particularly around how their parents responded to school-related struggles. They mentioned situations where understanding and calm dialogue made a difference, especially when students are encouraged to achieve long-term goals. One student recommends:

“Talk to the children about how they can earn their school-leaving certificate [by attending school], and [explain] that they cannot accomplish much without it. So, keep reminding them and encourage them to go to school so they can graduate” (S5).

Finally, students reflected on their own mindset and personal attitude. The self-awareness of one’s own efficacy and role in making choices and putting in motivational effort toward one’s goal was mentioned: one student reflected on his current situation in the PL setting:

“I’m here now and I actually want to graduate, so I’m making an effort” (S5).

Students talk about their open attitude, something that was key for changing behavior, accepting help, and reconnecting with school. One student described:

“Well, for example, if you’ve spoken to the school and they’ve made a suggestion [for an alternative pathway] That you look at what it’s like there […] just be open and don’t say no [to the proposal right away]” (S6).

6.2 Professional perspectives

School-based professionals described a broad set of prevention-focused strategies, along with intervention strategies to support re-engagement and respond to more severe cases. The categories are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Overview of categories of prevention-focused supports and interventions for the respondent group of school-based professionals.

6.2.1 Prevention-focused supports

Trustful relationship building with students was one of the most frequently mentioned preventive elements among professionals. These relationships were described as central to creating an open atmosphere where students feel seen and supported. A special education teacher characterizes an important function of relationships as follows:

“This personal connection or warmth (…) with which you approach the children [so that students do not] develop an oppositional attitude [toward school]” (B3, FG-MIX).

Moreover, relationships were seen as a bridge to understanding what students might not express openly by addressing problematic aspects that happen outside of school (FG-MIX).

At classroom level, classroom-based practices and teaching design were named, for example, implementing rules, positive behavior supports, and classroom climate as elements of classroom management. In line with this, a curriculum relevant to students’ lives and links to practical or work-related experiences were considered effective (FG-SEN). Moreover, individualized learning conditions were seen as facilitator to respond to students’ emotional needs. One special education teacher explained:

“Here, we […] have small groups. In a class with ten or at most twelve children, and sometimes even fewer – you can, of course, work with the children individually in a completely different way compared to a class with 25 or more [students]” (B3, FG-MIX).

Support of student mental health and social-emotional learning was another key area of focus. Professionals described encouraging students to engage in extra-curricular activities as a strategy to strengthen their wellbeing outside of academic settings.

“We always recommend leisure activities, such as joining a club or a sports group in a community organization.” (B3, FG-MIX).

In classroom contexts, one teacher used self-reflection activities focused on social interactions and emotional experiences. This involved asking students to “reflect on their behavior and how they interact with each other” (B3, FG-MIX) and “work on building their resilience” (B1, FG-MIX). The importance of coping strategies and resilience was underlined by other participants, particularly in relation to challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic (FG-MIX).

Considering strategies at school level, attendance monitoring and follow-up was described as a routine by teachers. It involved daily attendance lists and systematic outreach through communication in cases of unexplained absence. A teacher described this process as follows:

“The regular procedure is that the school office reports all excused students in the morning, and if any students are absent without an excuse, this is reported back to the office, and an attempt is made to contact the parents” (B3, FG-MIX).

In instances where families were unresponsive, school staff reported resorting to police contact (FG-SEN).

With regard to interdisciplinary and multi-professional resources, participants describe the value of collaboration with school psychologists, social workers, and other external partners that offer extracurricular activities (FG-SEN). A key benefit was the flexible use of support systems in daily school life, for example, the availability of multiple school-based staff that could be used informally and on short-notice (FG-MIX, FG-PL). One teacher from the PL setting reflected on the importance of this flexibility as follows:

“We have other support systems that we can activate either at short notice, in a planned way or very, very flexibly, depending on the need” (B2, FG-PL).

In contrast, teachers in the special education setting criticized the lack of professional resources, which limited their ability to spontaneously access such resources:

“We are not trained to handle very serious personal problems, and it would be nice to have someone nearby in situations like that” (B1, FG-SEN).

Prevention-based school projects – focused on violence, addiction, abuse, or sexual health – were seen as important ways of awareness-raising of risks and consequences. One participant mentioned the overarching educational purpose of these preventive projects which is to inform students about risks, protective strategies, and the consequences of harmful behaviors (FG-SEN).

“Preventive projects are largely about raising awareness […] about what different addictions can do to a person and the downward spiral they can cause. Or violence prevention, which again is about education, maybe, how do you protect yourself? What actions can you take?” (B1, FG-MIX).

In relation to the consequences of school absence, one special education teacher stated: “We also explain this to the students. Also, the sums [of the fines], which are issued.” (B3, FG-SEN). From the professionals’ perspective, this refers to a potential preventive strategy where transparent communication with students about the conditions and consequences of non-attendance in the German school system are used as a measure to encourage students to attend regularly.

With regard to structures, professionals emphasized how the school organization and environment could play a preventive role for SAPs, particularly for students lacking stability at home (FG-SEN).

“Designing an appealing school day (…) that conveys the idea that school is not just an obligation (…) but can also be something enjoyable” (B3, FG-MIX).

Another professional referred to the purpose of the full-day school program:

“To avoid situations where the parents or the home environment cannot provide adequate safety, to ensure that children are supported through a variety of full-day offers instead of being left on their own” (B1, FG-MIX).

The category professional knowledge and attitude refers to the participants’ personal stance and professional mindset that shaped their responses to SAPs:

“Sensitivity to the children’s problems” (B3, FG-SEN).

“[recognition of] a reluctance to attend school or school refusal” (B2, FG-SEN).

“The attitude you bring when working with the children” (B3, FG-MIX).

6.2.2 Interventions

As central element of intervention efforts, the professionals offered insights on successful and intensified communication with parents/carers and students. One teacher described this communication as follows:

“We keep trying to reach out to students and get in touch with them” (B4, FG-PL).

The contact with caregivers was especially important in cases where information was missing or assumptions about absences differed:

“We also had a case where the parents firmly believed that their child had left home. It did leave home but never arrived at school. Clear communication is very important, and it’s also helpful when the parents are available” (B1, FG-MIX).

As element of collaboration, professionals mentioned interagency consultation and referral in student cases that required more support than schools could provide alone. This involved both external and school-based actors. For example, the participants name school mentors that support individual children in class (FG-SEN and FG-MIX). Family and child social welfare services are contacted to bridge the contact between school and family. Staff from clinical schools is involved for consultation in procedures to provide or refer to intensive psychosocial interventions (FG-SEN and FG-MIX). One professional addressed the school’s required responsibility to establish measures and projects supporting school attendance, reflecting both the school’s resourcefulness and its limits when external structures are needed:

“I think schools often have to find their own ways and look for or even start projects themselves. But it’s probably not really their job; it would be actually better if external organizations took care of that (…) if there were more opportunities and points of contact. But out of necessity, schools are probably just tinkering and putting projects together on their own” (B1, FG-SEN).

Several professionals described the legal and administrative follow-up, tied to compulsory school attendance (Schulpflicht). The participants comment on how they follow procedures in which they may request medical certificates for longer absences or a review by a public health officer (Amtsarzt). If absences are unauthorized and exceed 5 days, schools will report the case to the local authority (FG-SEN). As one teacher stated:

“If it becomes extremely frequent – then at a certain point – disciplinary measures, fines, or something similar have to be initiated” (B2, FG-SEN).

Alternative educational pathways, including special education and PL were described as supportive spaces for a certain group of students. A social worker explained:

“[These are students] who don’t see themselves fitting into the school system, who are more hands-on learners, and other approaches are used to stimulate their intrinsic motivation” (B1, FG-MIX).

The professionals in special education mentioned that they often encounter students who have earlier experienced SAPs. Alternative education projects were especially relevant for older students experiencing long-term absence. These alternatives were perceived as better suited to the needs and interests of certain learners. Professionals in the PL sector described a specific educational conception focused on core subjects like mathematics or language learning, “so that [the students] do not feel overwhelmed at school.” (B2, FG-PL). Additionally, school-based and employment-based learning is linked by implementing interest-based internships for the students. Besides, autonomous learning of students was pointed out by professionals whereas the practical approach supports the student’s self-determination:

“The [students] can suddenly participate without constantly needing retraining or repeated explanations. This builds a sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy, which then can have a positive effect on the students” (B1, FG-PL).

Furthermore, professionals understand their role more as pedagogical guides than instructors, highlighting their accompanying role in the student’s learning process. One professional stated:

“That’s why we are deliberately called pedagogues, not just teachers or teaching staff. Our role is broad and pedagogically diverse, so to speak” (B2, FG-PL).

On another account, the role of school-based social work is mentioned, particularly in relation to sensitive cases and risks that require legal actions with the duty to protect against the endangerment of child’s welfare (paragraph § 8a). The need for joint solution-oriented approaches between social workers and youth is named. One social worker, for example, recalled:

“If they [students] say ‘it would help me if you sat by my side for half an hour. We drink a cup of tea, and then I’ll try to go into the classroom’ (…). Then I believe, depending on what the students say would help them, I think that’s what actually works.” (B1, FG-MIX).

Finally, professionals describe tailored reintegration measures for students returning after extended absences. School professionals pay attention to needs-based and graduated procedures, including adjusted timetables or the involvement of clinical staff to support the transition (FG-SEN). In addition, attention to the welcoming and warm culture upon the students’ return to school attendance is pointed out by one professional:

“And to say ‘yes, you were missed here too’. The [students] are happy when they return, (…) and also the classmates make it clear. ‘Nice to have you back.”’ (B3, FG-PL).

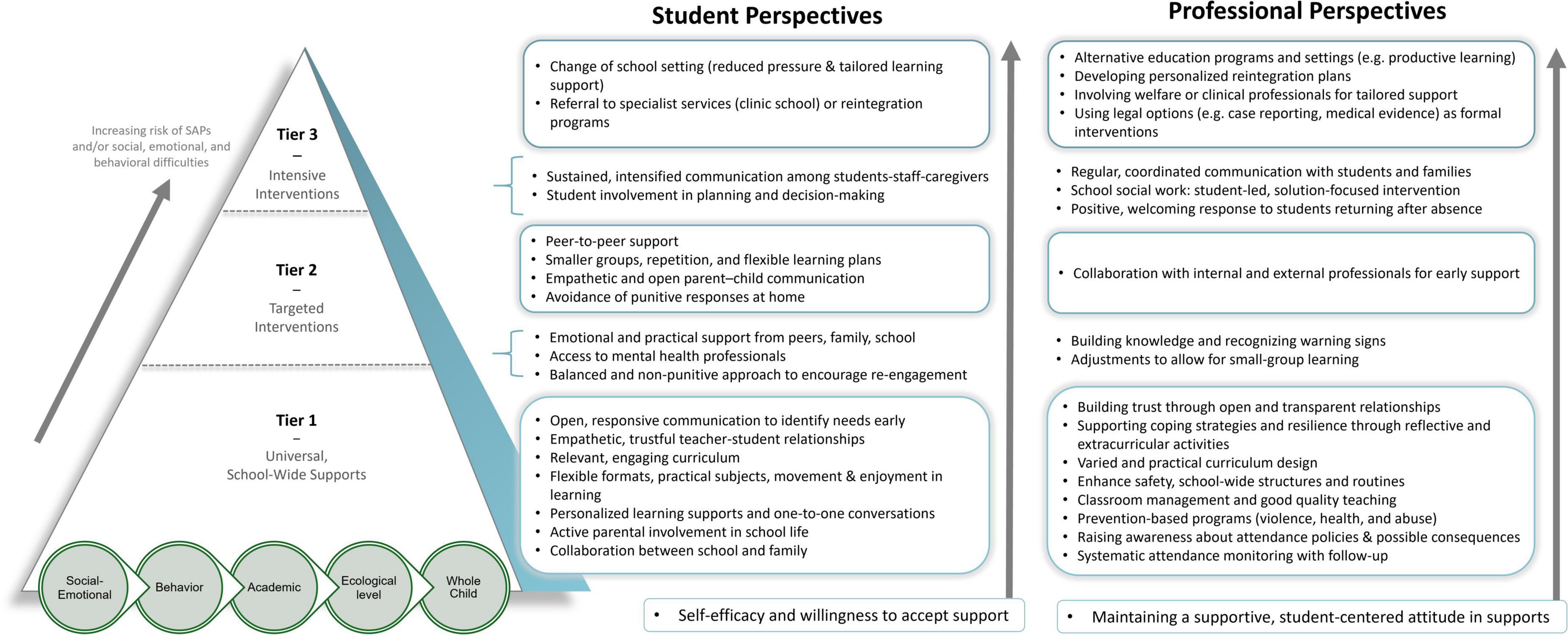

6.3 Mapping – model of multi-tiered system of supports for attendance

Building on the categories presented, key support strategies and elements were filtered from the categories on prevention-focused supports and interventions, and systematically mapped onto the levels of support defined within the MD-MTSS framework for school attendance. The full list of strategies and elements can be found in Supplementary Material 3. They are visually displayed in Figure 4 (shortened version). In accordance with the principles of MTSS, the universal strategies and elements mapped at Tier 1 can be reflected – as continuum – in Tier 2 and 3 interventions, designed to be more targeted and intensified toward specific groups of students. The following discussion addresses the commonalities and differences between the supports identified by both groups for the prevention and intervention of SAPs associated with SEBD.

Figure 4. Mapping of key support strategies and elements for the prevention and intervention of SAPs the MD-MTSS framework – based on students’ and school-based professionals’ views.

7 Discussion

7.1 Integration – commonalities and differences

Both students and school-based professionals identified a broad range of support strategies and elements for preventing and addressing SAPs associated with SEBD. When mapped across the tiers of the MD-MTSS framework (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020), the results show substantial overlap at the universal level (Tier 1), as well as nuanced differences in the interpretation and implementation of targeted (Tier 2) and intensive (Tier 3) interventions.

With respect to Tier 1 supports, both groups emphasized the importance of meaningful teacher–student relationships and proactive communication. Communication was viewed not only as a relational element in social support networks but also as a channel for identifying emerging difficulties. Students emphasized respectful, and empathetic interactions as protective, and as a means to voice and address problems before disengagement escalates. Similarly, professionals described trust-building through transparency and consistency as essential for early identification of emotional challenges. With regard to teaching, students expressed a strong need for pathways that accommodate their diverse learning and emotional needs, with access to varied structures and one-to-one guidance or learning support. Students particularly highlighted relevant, engaging teaching content that reflects their lived realities as fundamental to feeling engaged. Professionals similarly referred to good classroom management and a variety in didactic methods, instruction and pedagogy as preventive classroom-based practices that are aimed at all students.

Furthermore, both groups alike pointed to the benefit of family-school collaboration. Students described the need for active parental involvement in day-to-day school life to help them navigate school demands and emotional challenges, whereas professionals stressed clear communication with caregivers around attendance expectations and consequences.

Professionals placed stronger emphasis on school-wide structures and routines. For instance, they describe social-emotional prevention programs, placing an emphasis on coping and resilience, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, to prevent disengagement and problem behaviors. Professionals’ perspectives appear grounded in an awareness of students’ broader life contexts, including experiences of trauma, social-emotional difficulties, and complex family dynamics. This reflects a more systemic informed understanding of Tier 1 support, where non-attendance is seen not solely as a behavioral issue, but as a symptom of deeper psychosocial challenges. While professionals’ actions may follow procedural protocols (e.g., monitoring and follow-up of absence), their discourse reveals underlying pedagogical knowledge of the association between mental health and school attendance, as widely established in literature (e.g., Finning et al., 2019; Lereya et al., 2019). Students, in contrast, are more likely to center their experiences of support around relational and motivational elements that are conveyed through teaching practices, positive adult and peer behaviors, and trustful conversations.

At the person level, students reflect on the importance of their mindsets, particularly their beliefs in one’s capacity to overcome attendance difficulties – a sign of self-efficacy as important motivational construct and property of agency that affects effort, persistence, and choices (Bandura, (1997); Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2021). These beliefs may enable youth to achieve their goals and reconnect, further playing a role in their willingness and readiness to accept guidance and engage with provided support resources. This, in turn, makes these beliefs a mediating mechanism across all tiers of support. Professionals’ student-centered and positive attitude can be considered as an enabling mechanism that guides the implementation of support strategies at all levels of support. For instance, this is partly reflected in a teacher’s welcoming and non-judgmental response to students returning after periods of absence as an approach that can rebuild trust and facilitate reintegration into the school environment (Mills et al., 2019).

At Tier 2, characterized as targeted intervention (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020), both groups highlighted the need for personalized supports, especially in situations when students begin to show early signs of disengagement. The suggested key strategies include smaller groups, flexible scheduling and individual learning support plans. These elements are characteristic of teaching practices in special education and PL as well as inclusive pedagogy (Spratt and Florian, 2015). Both groups acknowledge the value of peer support. While students emphasized emotional connection and understanding from peers, professionals leaned toward structured peer activities in class – a subtle divergence. Social workers, in particular, described their special role in intervention, working closely with students through informal yet purposeful routines. A noteworthy observation is that students differentiate between the significance and the purpose of connections with support-providing adults. In addition to support from school, peers, and family, students mention the need for access to neutral professionals, such as mental health staff or school psychologists, who are not part of daily school life and can provide both universal and targeted support. This element is corroborated by the views of professionals, who refer to the essential function of collaborating with professionals or experts from other disciplines. The emphasis is placed on support systems that involve external actors (e.g., mental health professionals) in the context of targeted interventions to promptly address emerging issues.

In the context of targeted and intensified interventions, communication emerged again as a central topic. In these contexts, the emphasis shifted from general relationship-building to the coordination of support across school, family, and student systems, especially during periods of reintegration after extended absence. Professionals highlighted the importance of maintaining structured lines of communication with parents and external services. Students expressed a wish for encouraging messages at home that convey emotional understanding and gently remind about consequences, as opposed to the use of pressure or punishment. Interestingly, both groups convey that families should be treated as partners, not problems, in the planning of supports which aligns with Boaler and Bond’s (2023) findings on regular and coordinated communication between school staff, students, and caregivers in school-based interventions.

Tier 3 interventions revealed the clearest divergence in perspectives. Students emphasized the need for student-centered support, and alternative school settings such as PL. Professionals echoed this with descriptions of clinical referrals, tailored reintegration plans, and interdisciplinary support teams, suggesting a broader awareness of formal structures and regulatory mechanisms available to address chronic or complex SAPs. Students stressed the value and interest of being actively involved in the conversations surrounding the design of interventions. However, the explicit positioning of students as co-designers in intervention and reintegration was largely absent from the professional narratives, pointing to a gap between student expectations and institutional practices. On the contrary, professionals describe a reliance on formal, procedural tools when SAPs escalate. Legal measures, including the request of medical evidence, case reporting systems, and fines, were mentioned as standard tools. Yet, they were not questioned for their effectiveness in addressing root causes of SAPs (Heyne et al., 2024). Similarly, professionals in the special education setting posit that conversations surrounding fines are primarily used to educate students about the consequences of non-attendance. In this regard, absenteeism is framed as unfavorable, even oppositional behavior that should be averted. However, for some students this may be perceived as a threat, reinforcing a sense of punishment rather than support. This points to a system that remains oriented toward compliance with punitive, reactive procedures among professionals, particularly guided by legal interventions in compliance with German policy documents on school absenteeism (Enderle et al., 2023). In contrast, the participating students in this study made no reference to these legal measures. Instead, the students call for a responsive and adaptive environment with a focus on adjusting and reducing academic demands, as well as emotional support to meet their needs, all of which were provided in alternative settings. While the value of alternative settings (Halligan and Cryer, 2022; Sundelin et al., 2023), flexible structures as well as engaging curricula is echoed in previous studies on students’ perspectives (Gase et al., 2016; Richards and Clark-Howard, 2023), this study also illustrates the overlap with teaching professionals’ understanding of interest-based curricula, alternative provisions, and adapted teaching practices that match individual needs.

7.2 Summary of the integration and mapping

Overall, the mapping reveals a strong alignment between student and professional perspectives at the universal (Tier 1) level, with increasing divergence at targeted and intensive levels. The findings corroborate existing literature on student and professional views that emphasizes the centrality of belonging and relationships in promoting school attendance (Corcoran and Kelly, 2023; Enderle et al., 2024; Hejl et al., 2024), particularly for students experiencing emotional difficulties (Chian et al., 2024; Halligan and Cryer, 2022). Subtle differences in how support is conceptualized and enacted likely stem from variations in roles, resources, and lived experiences within the school context. Notably, the two groups use distinct forms of language: students tend to describe supports in less explicit, experience-based terms, while professionals rely on more conceptual language informed by training, professional knowledge, and theoretical frameworks. Special educators and social workers refer to customized interventions and high-quality teaching paired with emotional support, reflecting their commitment to vulnerable student populations. Both groups nonetheless show signs of perspective-taking: students reflect on systemic limitations or gaps. Teacher professionals view themselves not merely as instructors but as supportive partners in students’ learning process and lives. This focus can be interpreted as a reflection of compassion and relational awareness that are critical preconditions for creating emotional safety and trust-based relationships in school settings (O’Toole and Æiriæ, 2024).

The findings extend previous research by showing that professionals and students in this study conceptualize SAPs, particularly non-attendance related to SEBD, as complex challenges that require supportive and adaptive responses rather than corrective practices. This perspective reinforces the relevance of the MTSS framework as holistic, flexible structure, in which strengths-based, relational practices can be embedded to accommodate diverse student needs, while promoting wellbeing, engagement, and enjoyable learning experiences across all tiers. Despite some differences in perspective, both groups underscore the importance of shared responsibility and strengthened collaboration across systems. This perspective reinforces the need for a coordinated school-based care model, in which responsibility is not outsourced to external agencies but embedded within the school through readily accessible (“easy-to-reach”), multi-professional support structures. Such an approach aligns with research highlighting the critical role of interagency collaboration, team-oriented strategies, and resource allocation within a whole-school framework (Dennis, 2020; Finning et al., 2018; Hejl et al., 2024; Melander et al., 2022; Nuttall and Woods, 2013; O’Toole and Æiriæ, 2024).

Unlike previous studies, this study draws explicit connections between the practices described by school-based stakeholders and the MD-MTSS framework, using it as a guiding structure to organize and interpret findings. A key contribution of this study is the equal positioning of students and school-based professionals as informants and agents of change (Gillett-Swan and Baroutsis, 2024). Rather than treating professional and student perspectives in isolation, the study integrates these viewpoints to highlight areas of overlap and divergence. On the one hand, the equal consideration of multiple viewpoints holds the potential to inform more collaborative and balanced actions toward effective, holistic multi-tiered approaches to school attendance. On the other hand, contrasting perspectives help uncover potential disconnects that may explain ineffective practices (Eklund et al., 2022). Bridging these insights provides a pathway to re-evaluate dominant approaches to school attendance and validate the effectiveness of school-based interventions (Boaler and Bond, 2023) informed by students’ lived experiences, professional views, and the realities of implemented practices.

7.3 Implications for practice and policy

A recurring challenge in educational research and implementation is determining how integrated frameworks such as the MD-MTSS can be effectively incorporated into everyday school practice (Kearney and Graczyk, 2020). The current study offers practical insights into how school-and classroom-based support can look like within the MTSS structure when informed by the lived experiences of students and the school-based professionals working with them. Rather than proposing one-size-fits-all solutions, the findings encourage reflection on positive conditions for school attendance and adaptable practice elements that align with evidence-based strategies or programs (Farmer et al., 2021).

The overlap between professionals’ attitude and students’ emphasis on school-based universal practices underscores the value of models that center positive, meaningful relationships as a foundation for “attendance, engagement and wellbeing at all levels of intervention” (Boaler and Bond, 2023, p. 450). Some of the identified support strategies and elements within the MTSS structure can be delivered in evidence-based systemic approaches, for example, Positive Behavior Supports, school climate and bullying prevention programs, or trauma-informed practices (Johnson et al., 2025; Stratford et al., 2020). At the universal level, high-quality instruction and classroom management are required to strengthen positive conditions for engagement (e.g., Angus and Nelson, 2021; Leidig and Hennemann, 2023; Ricking, 2023; Simonsen et al., 2008) in addition to flexible arrangements, choice making opportunities or differentiated instruction (e.g., Lane et al., 2015; McLeskey et al., 2019; Melvin et al., 2025). An impactful form of peer-to-peer support can be found in mentoring programs, such as Check and Connect (Guryan et al., 2021; Heppen et al., 2018). Practices described by professionals, such as reflection activities, may help cultivate students’ sense of self-efficacy and self-awareness, both of which are essential skills for wellbeing (Schnell et al., 2025). Strategies at targeted and intensive levels support the potential effectiveness of school-based support teams [e.g., school counseling and social work (Boaler and Bond, 2023)], multi-disciplinary, individualized psychosocial interventions [e.g., CBT and mental health services (Johnsen et al., 2021; Pérez-Marco et al., 2025; Pina et al., 2009)], and family-school partnerships (e.g., Lindstrom Johnson et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2020). Likewise, elements from the PL format and alternative education programs, linked to personalized re-entry plans (Brouwer-Borghuis et al., 2019) and work-based or occupational learning, can increase students’ autonomy and support their self-efficacy upon return. These practices could be meaningfully adapted within mainstream settings to benefit all students at the universal level.

Importantly, students voiced a strong desire to be involved in decision-making processes affecting their education. This reflects a profound sense of agency and willingness to make choices that calls for the development of more participatory, rights-based intervention models as central component of democratic processes in school (Kenner and Lange, 2019) where students are not merely passive recipients and feedback providers but active contributors to the design and evaluation of attendance-related supports. Given that professionals in this study did not explicitly reference student participation, this presents a clear opportunity for system-level improvement.

The professionals’ attitudes in recognizing risks early and maintaining a student-centered lens represents a strengths-based mindset that should be improved. It likely influences the classroom atmosphere and a positive, relational approach where professionals respond authentically to students’ needs for recognition (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). This relational approach is mirrored by how students in this study valued balanced adult responses that encourage their re-engagement without pressure, while also signaling that their presence matters and that they are not being left to withdraw entirely (Hejl et al., 2024). This type of curious, committed encounter can, for example, be complemented with positive greetings at the door (e.g., Cook et al., 2018). While teacher professionals’ views often seem to center on instruction delivery (Dennis, 2020; Hejl et al., 2024), the findings reinforce the need to embed relational and social-emotional learning practices as part of universal teaching, not just within targeted interventions. Conceptually, this can be done through a school-wide approach to social and emotional learning (SEL) as foundation for mental health, academic achievement, and attendance. The mapped support strategies and elements represent indicators and opportunities for improvement, such as SEL integrated with instruction and curriculum, a caring classroom environment, authentic family partnerships, enhancing social-emotional competence of adults, youth voice, systems for continuous improvement, etc. (e.g., Bear et al., 2015; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Leidig and Hennemann, 2023; Mahoney et al., 2021).

Moreover, the student and professional group in this study point to the importance of early identification and follow-up procedures. In the German context, this aligns with calls for comprehensive monitoring systems to address SAPs (Sälzer et al., 2024). Such systems can be improved to function as holistic – multi-dimensional and context-sensitive – early warning tools by incorporating emotional, academic, and behavioral indicators alongside attendance data. Integrating this kind of nuanced data allows for timely and suitable responses while aligning well with the MD-MTSS framework (Graczyk and Kearney, 2023) and the multifaceted types and manifestations of SAPs (see Figure 1).