- Faculty of Health and Education, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom

Introduction: Considerable research has established that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased mental health and wellbeing challenges amongst university students in the UK. This empirical research investigates frontline staff perspectives of the pandemic to establish the main pressures experienced post-pandemic.

Methods: Participants from central service teams and academic staff (n = 23) provided qualitative insights via interviews and focus groups.

Results: The results were thematically analysed and suggest that marketisation and neoliberal practices are increasing pressure on academic staff, affecting their ability to implement relational pedagogical practices due to increasing duties and time pressures. Staff working frontline with students who are presenting with higher levels of mental health and wellbeing contribute to significant challenges post-pandemic.

Discussion: Recommendations are that the role of frontline staff is reviewed/restructured to reduce pressure to mitigate staff burnout, and to reduce over reliance on staff emotional labour. Staff wellbeing and training post-pandemic needs to be reviewed by Higher Education Institutes (HEI). These original insights into the pressures experienced by staff in the post-pandemic context will be of interest to staff, management, human resources, and HEIs as they discuss candidly the unavoidable truths of the challenges faced post-pandemic.

1 Introduction

A considerable body of research has established that the Covid-19 pandemic and the global crisis it precipitated have resulted in increased mental health and wellbeing problems among university students in the UK and internationally (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Jones and Bell, 2024). Understandably, much of the research so far has focused on the experience of students rather than staff; the primary aim of this study is to widen our understanding and knowledge of the impact of the pandemic in Higher Education (HE) and its ongoing consequences by exploring the experiences of academic and central services staff, and by investigating the main pressures on staff currently delivering HE education in the post-pandemic era.

More recently, it has been reported that working conditions in HE can lead to university staff feeling varying levels of “disillusionment, dissatisfaction, exhaustion, fatigue, stress and burnout” (Troiani and Dutson, 2021, p. 17) post-pandemic, particularly in developed countries. According to McKendrick-Calder and Choate (2024, p. 180) the negative impact of the pandemic on university students’ mental health and wellbeing is being felt internationally as this demographic presents with higher levels of “psychological distress and associated poorer mental health” than other age groups across society. They studied the lived experiences of teachers supporting the mental health of university students and found that this aspect of teachers’ work contributed further to personal and professional burdens (ibid). However, they also found that over time teachers found ways to minimise those burdens by adapting their practice with an element of compartmentalisation and via relational pedagogical practices. According to Su and Wood (2023, p. 230), “… relational pedagogy is an important area worthy of academic developers’ attention and institutional backing.” Relational pedagogy is centred on developing the connections between teachers and students to build trust via nurturing relationships that are grounded in reciprocity with benefits gained concerning student sense of belonging and educational outcomes (Gravett et al., 2021).

In addition, Wray and Kinman (2021, p. 34) research on staff wellbeing in UK HE found that, “respondents who reported higher levels of mental health problems and burnout were more likely to indicate that stress was heavily stigmatised in their organisation.” According to Troiani and Dutson (2021, p. 17):

“The rise of a burnout culture, in physical and mental well-being, broadly and in the UK Higher Education sector, is linked to the consumption and exhaustion of the labor workforce as a resource.”

Emotional labour is a term associated with the ideology of the burnout culture, specifically referring to staff regulation of emotions connected to their job (Nyanjom and Naylor, 2021). With increasing neoliberal duties of performance data, and student mental health and wellbeing, it is sensible to assume that emotional labour is a contributing factor to the rise of the burnout culture in HE post-pandemic (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Jones and Bell, 2024).

A recent international study by Whitsed et al. (2024, p. 1) of academics’ work during the pandemic and against the backdrop of challenging political and economic contexts like those in the UK, recognises the restrictions of the negative workplace conditions where “agency and voice are constrained” and endured by those working in academia. Their research focused on the decline of academic workplace happiness and recommended further support to improve healthy working conditions to aid academics to encounter increased exuberance in their roles. They assert that.

“The integration of neoliberal policies and employment practices across the higher education sector have profoundly changed what it is like for academic staff to work in a university and experience joy in their work” (Whitsed et al., 2024, p. 1).

Over the last 35 years, the evolution of HE has reflected the impact of economic marketisation models and neoliberal principles in education (Brown and Hillman, 2023). Martini and Robertson (2022, p. 1) assert that HE policies in the UK have increasingly “shifted towards a neoliberal meritocratic paradigm” establishing and legitimising cultures of new capitalism. Troiani and Dutson (2021, p. 5) attribute this shift to “…become more competitive to survive in a global HE sector.” Archer (2008 cited in Tight, 2019, p. 144) argues that “the contemporary neoliberal context, with its emphasis on performativity, mitigates against the achievement of secure and stable academic identities.” In addition, more than a third of UK universities are currently facing financial difficulties, and 66 universities are looking at cutting jobs and courses (Griffiths and Wheeler, 2024). These harmful outcomes of politically-driven changes in HE are not themselves new, but Covid-19 clearly added an additional layer of pressure on universities internationally. However, the effects of this on academic staff had not yet been fully explored.

A key element of the move to neoliberalism in UK HE has been the increased importance given to performance data such as that provided by the National Student Survey (NSS) (Office for Students, 2024), the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) (Office for Students, 2023), and the Destination of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) (HESA, 2024; McCabe and Bhardwa, 2023). Much of this is driven by the Higher Education and Research Act (2017) which underlies marketisation in the UK (del Cerro Santamaria, 2020; Manville et al., 2021). These metrics propel competition between and inside HEIs and reinforce the positioning of students as consumers (Brooks et al., 2021). Silverio et al. (2021) examine this notion with the concept of the “commodified” academic, asserting the impact of marketisation in HE.

It appears that much of the literature recognises that university staff across developing countries are under increasing pressure in complex and intersecting ways in the post-pandemic era. The purpose of our research was to examine the pressures that university staff are experiencing in the post-pandemic context, with consideration of the rise in student mental health and wellbeing challenges post-pandemic (Jones and Bell, 2024; CQC, 2024) in an era where neoliberalism is the dominant paradigm in HE. We therefore focused on one broad research question: what are the main pressures on staff currently delivering HE education in the post-pandemic era? This article presents an analysis of findings that explore these issues in more detail based on one large HEI in the UK.

2 Methods and methodology

The aim was to carry out an empirical study based on phenomenology, interpretivist, qualitative research, with data collected via semi-structured interviews and focus groups with the wider university central services staff and academic staff. This research took place in a large, urban post-92 HEI in England with a student population of 40,000+. Many similar “new universities” have larger numbers of students from “non-traditional” backgrounds such as widening participation, commuter, first generation students, ethnic minorities, working class (in the sense that they support themselves with paid work), and other underrepresented groups. Jones and Nangah (2020) demonstrate that some students from these demographics are potentially at a higher risk of being exposed to traumatic emotional experiences prior to attending university.

2.1 Data collection

Participants from student support teams “central services” (n = 13) and academic staff (n = 10) were recruited; the former work across the institution, which enabled us to gain a broader picture, and the latter were all from one faculty, which provided us with more detailed insight (Blaikie, 2014). The inclusion criteria to participate in the study was purely to be an employee at the university in either an academic role or a central service role and to have had experience of the pandemic while in role. Participants were recruited via dissemination of information packs including consent forms and through staff events where details of the study were delivered to encourage participation.

We used convenience and snowball sampling (Cohen et al., 2011) to identify potential participants as both groups had knowledge and experience of Covid-19, pre, mid and post in HE. Initially, we planned for convenience sampling due to the proximity of the researchers and the potential participants, but we quickly realized that participants could lead us to others; we asked participants if they could think of anyone else that we should speak to. Recruitment of participants among staff proved to be easier than we had anticipated, confirming our feeling that staff were keen to speak about their experiences and to share their experiences and knowledge.

We quickly found that there was an appetite to take part demonstrating the strength of feeling around the topics explored. Interviews and focus groups took place either online or in person depending on the participants’ preference (Braun and Clarke, 2013). It was found that the wider student support teams felt more comfortable and indeed found it more convenient to take part in focus groups, whereas the academics all opted for individual one-to-one interviews either online or in-person. Interviews took approximately 40–60 min depending on whether they were individual or focus group. There was scope to interview more staff, but we preferred narrow and intense data over wide and surface. Tight (2019) suggests a sample size of between 20–30 participants for a phenomenological study to be viable and practicable and our study comfortably met this criteria. This was also used as a guide for data saturation in conjunction with the constraints of the time limitation of the study and manageability of the data set for the research investigators.

Academics were able to provide richness of data in terms of their individual experiences while the support service teams were able to provide anecdotal insight into student issues bringing further expertise. The semi-structured interview was piloted prior to the main data collection to check for understanding, accuracy, flow, and fluency, and “…to reduce ambiguity and identify questions that produce the most useful spread of information…” (Somekh and Lewin, 2011, p. 62). Interview protocols were adapted to meet the differing expertise of the two participant groups (academics and central services staff). Using semi-structured interview protocols aided the coherence of the interview responses aligned to the research intention (Daniel and Harland, 2018).

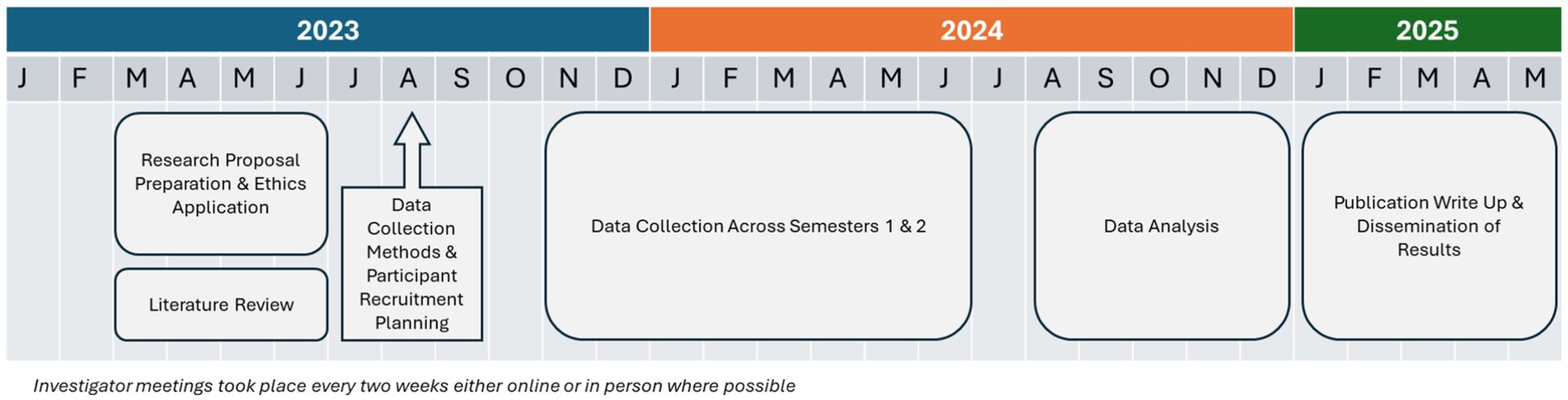

Two investigators, one senior academic and one support member of staff from differing programmes were responsible for collecting the data and they balanced this around their workloads across the academic year of 2023–24, following a research schedule that was established at the outset, which took into account the need for contingency time around assessment and marking times. This research schedule also aided the development of a planned audit trail of the research and subsequent documentation (Braun and Clarke, 2013). The two investigators had not worked together prior to this study which further adds to the authenticity, validity, and transparency of the research processes adopted as we continually questioned our methods and processes and thus the results (see Figure 1).

Our data were transcribed verbatim using transcription software and then read closely by both research investigators. Thereafter the data went through a series of successive refinement and coding techniques based on qualitative content analysis (Flick, 2018). This led to the final set of themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006) for further analysis and discussion. These themes emerged during the iterative data analysis process and were driven by participant responses leading to the four themes reported on in the results section. Using this technique provided a robust structure for handling large amounts of data. While time consuming, these techniques proved valuable in the reporting and, we believe, contributes to transparency in the data collection and analysis process strengthening the validity and credibility of the analysis (Hennink et al., 2020). Each transcript was analysed independently by each investigator to minimise potential bias and to affirm key themes and to identify significant threading themes.

2.2 Ethics statement

Full ethical approval was obtained for the study (no. ID55391V4) which complied with the Data Protection Act (2018) and BERA (2024) and the study took place across the academic year 2023–24 (see Figure 1). To support this a detailed timetabled plan was also included in the ethics application, with extra time factored in for capturing interviews across the academic year and time to analyse data (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Participants were presented with an information sheet, which detailed the study and a consent form prior and additionally at the start of each interview participants were asked again if they had any questions about these two documents and their contents (Cohen et al., 2011), with any queries answered individually before proceeding. Participants were anonymised by being given a code and identifying names were removed from transcripts and digital folders where possible. Access to the digital folders was only available to the two investigators and documents were secured safely in accordance with GDPR and the Data Protection Act (2018) and institutional digital requirements. No personal data was transferred digitally or otherwise during the data collection, and data analysis processes. In addition, social characteristics of participants are not reported in this paper specifically to further maintain anonymity (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Furthermore, the job roles of those who took part have also been removed to prevent participant identification. To protect the participants’ anonymity, findings or quotations are attributed simply to either CSS (central support services) or FAS (faculty academic staff).

3 Results

Following our thematic analysis of the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Flick, 2018), the following four broad themes were identified and are presented in order of participant response significance:

1. Neoliberalism.

2. Relational pedagogy.

3. Time and workload.

4. Staff health, exhaustion, and burnout.

FAS refers to faculty academic staff, and CSS to central services staff.

3.1 Neoliberalism

Faculty academic staff (FAS) communicated intensely and powerfully about the effects of marketisation and neoliberal policies in HE, which they felt have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

It [the problem] is the funding and the expectation. It feels like I have to be a ‘jazz hands’ lecturer, engage with student voice, check that [students] are happy all the time, show progression, ensure [students] get a good job at the other end and take care of [students’] mental health throughout that, plus doing world class research. (FAS).

Academic staff felt that the Covid-19 era had increased the pressure on HE, leading to an intensification of the effects of neoliberal practices (Manville et al., 2021). An example is performance monitoring through measurement tools such as NSS and TEF (O’Leary et al., 2019): A participant described these as the “growing menace around…being constantly monitored.” Others description of life in the neoliberal university echoed Troiani and Dutson’s (2021) concept of the “edufactory”:

[It] feels like we are on a bit of a conveyor belt in a factory or something like that rather than in privileged academic positions where again, from our point of view as teachers, we should be really enjoying the material, you know, researching actively without feeling we have not got the hours. (FAS).

This reflects Troiani and Dutson’s (2021) assertion that neoliberal practices need to be resisted and rethought to reclaim the liberal spaces and protect university values as a space of learning, thinking, and working and it would appear our participants would agree. Similarly, Leach (2019 cited in Bell, 2022, p. 492) “argues that HE should be about enabling people to become empowered, rounded citizens with self-confidence, self-worth, enhanced social capital and agency.” Instead, as our participant above points out, “the soul of academic labour is becoming lost in performativity” (Sutton, 2017, p. 625). Participants also commented on the tension produced by the “tangible pressure” of often competing aims:

It is something there in the background lurking all the time and is felt across the staff team as a tangible pressure. For example, what is it you are doing? What is your main focus? Is it research, is it teaching? Even in the PDR [Personal Development Review], there is constant pressure to align to the uni[versity]‘s values and mission statements. There is a conformity pressure, but that could be quite different to what that member of staff is about. And if you resist it you are fighting against a tide, so I suspect a lot of staff just go along with it. (FAS).

This comment on the ways in which academics feel unable to effectively juggle the many growing tasks that fall under their remit reflects the notion that academic identity is being systematically “unbundled” (Skea, 2021, p. 401) and provides anecdotal support for the idea that “neoliberal ideologies and management practices […] have profoundly altered the academic work environment” (Whitsed et al., 2024, p. 2). We argue that these work practices are also having a serious impact on the mental health, motivation, engagement and wellbeing of staff (Whitsed et al., 2024; Boncori et al., 2020; McIntosh et al., 2022).

Academic staff were clear about the importance of relationship-building in supporting students and encouraging engagement, particularly for students with mental health and wellbeing difficulties (Bell, 2022; Snijders et al., 2020). But they were also clear that it affected their own job satisfaction; academic staff put student relationships at the forefront as they find it especially rewarding supporting students to grow throughout their programmes of study (Whitsed et al., 2024). One participant explained:

Relationships are fundamental to engagement, but the continuing pressure to get more students in, and to manage with fewer staff wherever possible, affects this. I think this [the pandemic] has exacerbated the situation, along with the whole performance thing and asking students the same questions constantly, and senior managers being surprised when answers from students are not always so pleasing. (FAS).

Our data highlights the significant impact neoliberal and marketisation practices are having on academic staff who are juggling multiple and increasing roles.

3.2 Relational pedagogy

Relational pedagogy can be defined as “an intentional practice whereby classroom learning builds connections and positive relationships for learning purposes” (Su and Wood, 2023, p. 231), and stresses the “importance of relationships, of connections and of care, within learning and teaching” (Gravett et al., 2021, p. 388). Relational pedagogies are curiously positioned in that they can be thought of as a kind of antidote to the student-as-consumer culture of neoliberalism, but they are also increasingly being used as a tool to achieve the neoliberal-derived end of “customer satisfaction.” Relational pedagogies are considered central to the approach to learning and teaching at many universities.

Our academic participants discussed the pressures they feel in relation to making sure that students are having a positive university experience (Boncori et al., 2020), and mention that the weight of that expectation has become more intense since Covid-19. Many academic staff clearly feel pressure to “go above and beyond to make sure that they [students] are having a good learning experience” (FAS) when they might not have done previously because of the Covid-19 interruptions. They also reported the pressures of having higher levels of empathy towards students post-Covid, by.

account[ing] for the different things that go on in students’ lives post-pandemic, such as caring responsibilities and their own health needs or vulnerabilities. (FAS).

Another participant noted additional unknowns in dealing with students which might affect relationship building, such as “mak[ing] up for the student’s negative experiences from either school or college or previous to university.” (FAS).

However, the challenge for academic staff in attempting to provide enhanced support for students has risen over time (Boncori et al., 2020). Our participants talked about wanting to meet with student’s face-to-face despite, for example, difficulties of getting a room booked or finding a confidential space in which to meet (Whitsed et al., 2024, p. 1). They also reported feeling uncomfortable with inviting students in for a face-to-face meeting outside of their timetabled seminars/lectures, because they recognise that students are increasingly time-poor. They feel that the bigger changes within HE resulting from Covid-19 have made meeting students more regularly for personal tutoring or pastoral support more difficult (Boncori et al., 2020). They also reported feeling that more personal tutor time should be timetabled to develop relational pedagogy and early intervention support strategies (Whitsed et al., 2024, p. 1) especially for those students who are “feeling more anxious about talking in class or participating as they are not as confident post pandemic” (FAS).

Our academic participants recognise that meeting online, while convenient, is not conducive to building trust and relational pedagogy (Jones, 2021). They felt strongly that the relational gains provided by face-to-face personal tutoring is beneficial, in agreement with Jones (2021, p. 163), who highlights that “regular academic and personal tutorials, face-to-face feedback sessions are beneficial when supporting students from widening participation backgrounds and those students exposed to traumatic experiences.” Academic staff highlighted the difficulty of “knowing that face to face support is really, really important but I’m not sure how this fits now. (FAS).

Furthermore, academic staff felt relationship building with students is crucial for teaching, student engagement, attendance, and early intervention (Bell, 2022; Bovill, 2020). Snijders et al. (2020) found that positive relationships between staff and students can lead to improvements in student retention, academic performance, and sense of belonging (Leach, 2016). Whitsed et al. (2024, p. 9) report that the academic/student dynamic can bring “great joy” to staff, demonstrating the reciprocal benefits of relationship building for both staff and student. Our participants agreed:

Relationships are key to teaching. If [students] get on with you then they will attend your sessions and any issues get flagged up earlier and can be addressed sooner. This is what works quite well. (FAS).

Participants from central student services (CSS) acknowledge the importance of the role of the personal tutor that is usually undertaken by the academics embedded within the programme, and also appeared aware that good quality relationships required adequate resources: “academics need time and commitment and understanding about what the [personal tutor] role is” (CSS).

In addition, academic staff talked about engaging with students both professionally and academically, but also communally and interpersonally (Snijders et al., 2020; Whitsed et al., 2024). They mentioned the importance of the incidental conversations with students that can happen when they see them around the building for example. They acknowledged that time pressure generally reduced their ability to invest, implement and maintain relational pedagogy (Bell, 2022; Bovill, 2020).

I just seem to be flying from one thing to the next without the time to stop and talk to students, to get to know them, to build trust and to understand their needs better. Time for relational pedagogy would make such a difference especially to those who fall through the cracks because they are quiet, do not reach out or become disconnected. (FAS).

One participant commented pertinently on the nature of “trust,” and the difficulty of developing truly trusting relationships given the pressures of time:

I think a lot of tutors think that they are approachable and kind of like, hey, anyone can ask me questions, but no. …[T]here’s trust and there’s like trust. So you know, you can trust someone not to single you out and humiliate you just for the sake of it, like people would at school, that’s one level of trust, but there is also another kind of trust level where you just do not know how people are going to react. You cannot enforce trust, this is owned by two people. I do not have time to build trust with every single student, I cannot do that. It’s not realistic, even if I wanted to – that’s the reality of it. (FAS).

Academic participants stressed the importance of relationship building with students to help progression (Bell, 2022; Bovill, 2020; Whitsed et al., 2024). However, some felt that since Covid-19 they are unsure of when to “push” or “stretch” students in the classroom, or about what expectations might be reasonable: one mentioned feeling as if “I’m in a period of treading quite carefully about assessments, about classroom dynamics” (FAS). However, this appears to depend somewhat on pre-existing relationships: the same academic colleague talked about feeling more confident with those students who they went through Covid-19 with, and less sure about students who have arrived at university post-pandemic. Participants from central services added that work needed to be done to ensure that academics.

‘understand what they can do in terms of pastoral support and signposting. If academics aren’t well equipped, that’s where it [early intervention/relationship building] fails’ (CSS).

These findings confirm that academics need help and support to equip them with the skills to manage complex student situations and to reduce the pressure that students (and the staff themselves) are encountering post-pandemic.

3.3 Workloads and time

Several academic participants reported the limitations of large group teaching (Bell, 2022; Bovill, 2020). They explained that having smaller group sizes helps the development of good conversations with teaching staff and classroom peers. They also felt that large group sizes are impacting on student’s enjoyment of their degree (Bovill, 2020), adding that students are “fazed being part of such big groups [and] not as likely to speak up or have conversations, interrupting relationship building” (FAS). Staff members discussed the knock-on effect of teaching large groups in terms of increased marking expectations and how this has become overwhelming.

The marking is also a huge problem especially if you have large groups, this leads to large marking sets, which means less time to really focus on bespoke support for students that they find helpful. Previously, I have had more time to send follow up emails or check-in emails, but not this year. Group sizes are huge and when staff leave, they do not appear to be being replaced. (FAS).

Participants from central services talked about how to compassionately and effectively support students with increased mental health and wellbeing needs post-pandemic (Jones and Bell, 2024). Several wanted to see a much more integrated personal tutoring model implemented between personal tutors, academics, and wider student support services. One drew a picture of the complex reasons why intended outcomes can fail to appear:

If you are asking me [whether] I think we are supporting our students, no I do not, because of that disconnect […] We’re not getting to the academics who do not think it’s their job, who do not have the time, and the model is not there. Academics see our students [at] every stage of their progress or lack of progress, and they are absolutely at that frontline. They [students] have to go through an academic most often in order to get to student services. (CSS).

This powerfully demonstrates the importance of the role of the academic in wider university systems and student support, particularly relational pedagogy. This amounts to a considerable increase in pressure on academics in terms of their required skills and their expanding duties because of the increase in the number of students with higher levels of mental health and wellbeing difficulties (Jones and Bell, 2024).

3.4 Staff: health, exhaustion, and burnout

Staff across both participant groups talked about the effects of the pandemic on their health because of the increased pressure in their jobs during and post-pandemic. Several participants made it clear that this additional pressure is due to the rise in student mental health and wellbeing needs and neoliberal working practices. Academia is known as “a high-stress occupation resulting in significant levels of ill health” (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021, p. 1179), one in which “excessive workloads and workload models which frequently under-count time necessary for fulfilling tasks, and many tasks prove invisible to the workload assessors” are a contributing factor (Morrish, 2019, p. 9). This was also evident in contributions from staff providing cross-university support: one noted that they had “never worked so hard in my entire life as I worked during Covid-19 and the year after… We were all on our knees, everybody was, but nobody talks about it” (CSS), “I do not know how [name] is still standing. We do not talk about this in the sense of reliving the trauma cause all of us have gone through it.” (CSS).

Certainly, during Covid-19 staff found it quite difficult to manage their own needs when having to respond to the effects of the pandemic, learn new teaching methods and try to maintain student engagement and satisfaction (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021; Heffernan and Smithers, 2024). Both CSS and FAS groups reported that some of their own needs were not taken fully into account by the university at the time, particularly when returning to campus following lockdown and coping with safety measures (e.g., masks, social distancing) which were not always fully enforced or enforceable. Some staff found this negatively affected their own anxiety levels quite severely (Bodenheimer and Shuster, 2019).

Other members of staff talked about the trauma of the pandemic and the emotional burdens placed on staff during this period (Rickett and Morris, 2021; Nyanjom and Naylor, 2021; Morrish, 2019). One commented explicitly on the load of “unseen labour,” noting that “some staff [take on] more emotional labour than others… I know that I do [more] and […] doing it exhausts me” (FAS). The emotional labour has not ceased post-pandemic, as staff deal with ongoing after-effects.

I am staggered by how many students have really serious anxiety difficulties, to the point where they find they are unable to leave their rooms. Some have explained that they want to come in, they aim to come in, and some […] cannot make it past the doors. I have supported several students with these issues over the last few years, something I had not encountered pre-pandemic. These issues must affect ongoing progress and I see students withdrawing or deferring more often than pre-pandemic. (FAS).

Academic staff explained how this additional emotional labour affects their own work-life balance as they work long into the evenings or at weekends to support students (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021; Rickett and Morris, 2021; Nyanjom and Naylor, 2021), often without workloaded time for this extra effort (Morrish, 2019; Heffernan and Smithers, 2024).

A student might turn up and tell a story that it’s really difficult for staff to hear. They’re not counsellors [and] they have maybe got their own issues. It’s very difficult to deal with a student who’s telling you, you know everything, all these awful things that that they tell [you]. And staff are feeling that they need to respond to students who are in a mess when, quite frankly, the staff are still probably struggling. (FAS).

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the unpredictable scale of the Covid-19 outbreak, the sheer scale of this extra work does not appear to have been catered for within workloads (Rickett and Morris, 2021; Nyanjom and Naylor, 2021; Heffernan and Smithers, 2024). Emotional labour was a feature of academic life before the pandemic but inevitably increased significantly during and after it (McKendrick-Calder and Choate, 2024). The responsibilities that fall on academics who are not trained counsellors, but who feel an overriding sense of responsibility to support students, is likely to increase the chance of staff burnout (Bodenheimer and Shuster, 2019; Troiani and Dutson, 2021).

4 Discussion and summary

Our data highlights the interaction between the impact of neoliberalism and the effects of the pandemic on university staff who are juggling multiple roles and ever-expanding duties (Morrish, 2019). This reduces staff motivation, satisfaction, and wellbeing, and can lead to burnout (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021). The data reveals that academic staff are feeling the weight of emotional labour post-pandemic, mostly because of their responsibility for ensuring students are having a positive experience. This pressure directly and negatively affects their own emotional responses and wellbeing. The likelihood is that these findings are felt similarly across developing countries who have also adopted neoliberal working practices, particularly post-Covid.

The data also confirms anecdotally that an academic’s duties are expanding, and that many academic staff now feel they have to be “all jazz hands” (AS) in a number of crucial and demanding areas of academic life. The pandemic in effect has increased the pressure of neoliberalism policies in HE, with the traditional academic role at least partially “lost” (Sutton, 2017, p. 1) amidst a host of new tasks such as performance monitoring (Whitsed et al., 2024). Furthermore, the data highlights that academics need to be trained, equipped, and supported with pastoral/personal tutor duties as they are often the first point of contact for students. Yet staff did not always perceive that their own health during and after the pandemic was prioritised, and the emotional burdens of supporting students with highly complex needs during the pandemic and the growing pandemic duties are taking its toll.

Academic staff reported wanting to build good relationships with students, recognising that relational pedagogy is extremely important in a number of ways (Bell, 2022; Snijders et al., 2020): good relationships with students aids engagement and sense of belonging, and assists in early intervention (Whitsed et al., 2024). Yet on increasing class sizes and intensified workloads work against the development of such good relationships. Trust is a key factor when relationship building but trust takes time and is precarious and is based on a two-way exchange (Whitsed et al., 2024; Jones and Nangah, 2020; Jones, 2021).

The key problem is that under neoliberal constraints and imperatives, universities are increasingly “running hot,” running a machine (or an organisation) constantly at its limits so it overheats and eventually stops working (Thomas et al., 2020). Applied to universities, our data suggests that “running hot” means that staff are being enjoined to do more with less, to work harder and smarter, to improve performance in all the ways that are valued by virtue of being measurable; the “lumbering beast” (Ball, 2003, p. 1050; Heffernan and Smithers, 2024) is always behind us, looking over our shoulder to ensure that we improve performance and meet or exceed targets. Troiani and Dutson (2021, p. 5), report that the “neoliberal university has taken hold in many developed countries” with the focus on research and teaching being driven by competitive marketized industry business models.

Neoliberal innovations may of course be propelled by necessity, and they are not in themselves inherently bad. But overlook the essential elements of time, relationships, and trust. Where academic staff are under immense pressure to perform in an increasing variety of roles, what time is available for the casual and unstructured conversations that build trust (Jones and Nangah, 2020)? We suggest that the familiar procedural tools of university systems; digital platforms, guidance documents, measurable outcomes – are unsuited to the purpose of building true relationships founded in confidence and trust. Instead, such systems are likely to have the unintended consequence of leaving academic staff drained and less confident in their ability to do their role well, with less emotional energy for empathy and authenticity with students. In the name of quantifying achievements and tracking KPIs (key performance indicators), such measures could also contribute to the increase of poor mental health among academic staff who are on the frontline battle to help students with their mental health problems (McKendrick-Calder and Choate, 2024). This is not likely to be helpful to the staff, the students, or ultimately the HE sector as a whole.

Much of the day-to-day responsibility for helping students with mental health issues falls on academic staff because they meet students most often and are usually the first point of contact for students in distress, and because students are more likely to have an existing relationship with academic staff, which makes revealing the mental health issue easier. Although students with acute mental health crises, those perceived to be in serious danger, are rightly prioritised by both the NHS and university counselling services, many students are suffering from less serious problems which are nonetheless real and distressing and which affect their ability to do well at university. Providing support for these students is only one of many elements of the work of academic staff, but it appears to be a significant element of their work, and it is not necessarily an area in which academic staff are trained or experienced. Providing support for students with mental health problems, therefore, amounts to a considerable additional workload for academic staff at a time when those staff are themselves under huge pressure and commonly experiencing “exhaustion, fatigue, stress and burnout” (Troiani and Dutson, 2021 p17). While our academic participants reliably reported wanting to help students, it is difficult to see this renewed push for emotional labour as other than an additional drain in a time of considerable resource scarcity and competing time pressures.

One of the strategies that universities are using is to encourage the development of stronger relationships between students and academics in general, and with personal tutors in particular. The aims are to give students a better sense of belonging, to provide students with a more accessible place where their concerns can be heard, and to enable staff to signpost students to other sources of support. Personal tutor relationships are seen as relational in the sense that they aim to provide empathetic, proactive, inclusive, collaborative, student-centred, authentic support that helps students navigate their own aspirations and pathways towards autonomy and success (Calcagno et al., 2017).

In the wake of particularly tragic outcomes such as the Abrahart vs. Bristol University case (Courts and Tribunal Judiciary, 2024; Equality Human Rights Commission, 2024), there have been calls during a recent debate in Parliament (House of Commons, 2024) for both renewed legal attention to the precise nature of the duty of care universities owe their students suggesting a “student support excellence framework” in line with the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) and the Research Excellence Framework (HC Deb, 2023). We fully support better support for students and it is clear that we need legal clarification on the law (duty of care), but we would argue that adequate, workload hours, training and guidance must be put in place for any changes to have the desired effect.

5 Recommendations

The data provided in this article supports a possible consequence of the pandemic being the increased devolvement to academic staff of responsibility for students’ mental health leading to worsening stress and anxiety for academic staff (Hall and Bowles, 2016). We propose the following recommendations, these need to be reviewed in the context of two key factors.

The first of these is that the mental health crisis facing the UK university sector is large. Bolton (2024) reported the proportion of 18-year-olds entering HE to be 35% in 2023, a figure which does not include mature students or international students. This means that despite the well-known financial problems currently besetting the sector (Griffiths and Wheeler, 2024), its income is large and its staff numerous; however, it also means that the number of students and staff with mental health issues is proportionally large (Morrish, 2019), and this number has grown since the pandemic. Moreover, at least two issues mean that the scale of the problem is probably under-reported: the acknowledged difficulties of admitting to mental health problems caused by misinformation, stigma, and discrimination (Thornicroft et al., 2022), and the difficulties in obtaining formal recognition of mental health issues.

The second factor is that currently there is no reason to believe that the university sector is generally well placed to deal with mental health problems among its student body or staff. The primary function of a university is educational rather than medical, and supporting mental health is always likely to come second in allocation of resources.

So, short of a revolution in the prevailing economic and political paradigm, what can be done? We suggest that the following steps could be taken within the current framework, in the best interests of students but also of the university sector itself.

1. Academics and other student-facing staff need adequate time allocated within workloads to focus on relational pedagogy to aid teaching and learning, along with building trusting relationships based on authentic interactions. This in turn will aid student engagement and sense of belonging, and thus in the end the universities’ own yardsticks of success. The type of attention required to identify and assist students with mental health issues is almost certainly unsustainable where colleagues are working with large groups of students, so class sizes may need to be reduced or staff numbers increased to support this.

2. If the role of personal tutor is intended to be the key link between distressed students and central services such as counselling, then personal tutors need support to develop expertise in this role: with training, counselling, management support and time allocation when providing these frontline duties. Central HE staff with roles that focus on mental help support (e.g., counselling services) are an important supplement but a substantial burden is likely to continue to fall on the shoulders of general academic staff, if for no other reason than that they are more numerous, are better placed to see students frequently, and have a better view of students’ usual behaviour in context.

3. The role of the academic needs to be reassessed against the shift from liberal to neoliberal practices and a review of duties needs to be undertaken with a view to reducing pressures from overwhelming “role creep” to decrease potential effects on staff burnout. During the pandemic, precautions against transmission were promoted at least in part to protect staff operating the NHS, which might otherwise have been overwhelmed (Yano, 2020, p. 132), and for the same reasons staff wellbeing needs to be at the forefront of HEI practices moving forwards.

6 Conclusion

The main limitation of this study is that the data has been collected from one HEI, in the UK, albeit a large institution with high population of non-traditional students. It is likely, that these demographics may well align with international institutions who share similarities. That said, the diversity of participant in terms of role e.g., Central services and academic provide depth and breadth of data which has aided the validity of the study by bringing differing perspectives to the key issues. This study could be replicated at other institutions nationally or internationally and perhaps that would be the sensible direction of travel to add further “evidence” to the key points debated.

While we acknowledge that universities cannot solve the wider societal pressures that appear to engender the type of mental health issues we are seeing in HE students and staff, especially given that HE as currently conceived is itself embedded in and a product of the system which produces those pressures. If those pressures continue, as seems likely, HEIs in the UK and further afield are in a double bind; to not act, or to act inadequately, risks making even worse mental health of students and staff. This ultimately affects the metrics directly linked to university performance (e.g., progression and completion rates); but to act requires both purposeful planning, reorganisation and a substantial investment in staff and time.

Our view, resulting from the data analysed and the auxiliary literature is that supporting staff and student mental health should be treated like campus buildings and virtual learning environments: they are not core elements of teaching and research, but despite the huge costs involved they are essential if those core activities are to be carried out effectively. We urge HEI’s and policy makers to utilise the “evidence” base provided in these results to drive changes across the sector for both student and staff.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethics and consent restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Manchester Metropolitan University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., and Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: a global perspective. Sustain. For. 12:8438. doi: 10.3390/su12208438

Ashencaen Crabtree, S., Esteves, L., and Hemingway, A. (2021). A ‘new (ab)normal’?: Scrutinising the work-life balance of academics under lockdown. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 1177–1191. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1853687

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Bell, K. (2022). Increasing undergraduate student satisfaction in higher education: the importance of relational pedagogy. J. Further High. Educ. 46, 490–503. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2021.1985980

BERA (2024). Ethical guidelines for educational research, fifth edition. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024 (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Bodenheimer, G., and Shuster, S. M. (2019). Emotional labour, teaching and burnout: investigating complex relationships. Educ. Res. 62, 63–76. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2019.1705868

Bolton, P. (2024). Higher education student numbers. (UK Parliament: House of Commons Library research report 7857). Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7857/

Boncori, I., Bizjak, D., and Sicca, L. M. (2020). Workload allocation models in academia: a panoptican of neoliberal control or tools for resistance? J. Critical Org. Inquiry 18, 51–69. doi: 10.7206/tamara.1532-5555.8

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creating learning and teaching: Towards relational pedagogy in higher education. England: Critical Publishing.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Brooks, R., Gupta, A., Jayadeva, S., and Lainio, A. (2021). Students in marketised higher education landscapes. An introduction. Sociol. Res. Online 26, 125–129. doi: 10.1177/1360780420971651

Brown, R., and Hillman, N. (2023). Neoliberal or not? English higher education. HEPI debate paper 34. Available online at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Neoliberal-or-not-English-higher-education.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Calcagno, L., Walker, D., and Grey, D. (2017). Building relationships: a personal tutoring framework to enhance student transition and attainment. Stu. Engagement Higher Educ. J. 1, 88–99. Avaialble at: https://sehej.raise-network.com/raise/article/view/calcagno

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. 7th Edn. Abingdon: Routledge.

Courts and Tribunal Judiciary (2024). The University of Bristol -v- Dr Robert Abrahart. Available online at: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/The-University-of-Bristol-v-Dr-Robert-Abrahart.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2025).

CQC (2024). CQC warns that long waits, inappropriate accommodation, and lack of local support mean children and young people are being failed by mental health services. Available online at: https://www.cqc.org.uk/press-release/cqc-warns-long-waits-inappropriate-accommodation-and-lack-local-support-mean-children (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Daniel, B. K., and Harland, T. (2018). Higher education research methodology: A step by step guide to the research process. Oxon: Routledge.

Data Protection Act (2018). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted (Accessed January 8, 2025).

del Cerro Santamaria, G. (2020). Challenges and drawbacks in the marketisation of higher education within neoliberalism. Rev. Eur. Stu. 12, 22–38. doi: 10.5539/res.v12n1p22

Equality Human Rights Commission (2024). Advice note for the higher education sector from the legal case of University of Bristol vs Abrahart. Available online at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/guidance/advice-note-higher-education-sector-legal-case-university-bristol-vs-abrahart (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Gravett, K., Taylor, C. A., and Fairchild, N. (2021). Pedagogies of mattering: re-conceptualising relational pedagogies in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 29:388. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1989580

Griffiths, S., and Wheeler, C. (2024) Universities facing a cash ‘catastrophe’. The Sunday Times, Issue No 10,427. Available online at: https://www.thetimes.com/uk/politics/article/universities-face-cash-catastrophe-with-threat-of-mergers-and-course-cuts-rwg9s2s6g (accessed July 21, 2024).

Hall, R., and Bowles, K. (2016). Re-engineering higher education: the subsumption of academic labour and the exploitation of anxiety. Work 28, 30–47. doi: 10.14288/workplace.v0i28.186211

HC Deb. (2023). Higher Education Students: Statutory Duty of Care - Hansard - UK Parliament. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-06-05/debates/9BA59E93-4342-4AD6-BA94-379DCA6A24E0/HigherEducationStudentsStatutoryDutyOfCare

Heffernan, T., and Smithers, K. (2024). Working at the level above: university promotion policies as a tool for wage theft and underpayment. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 44:2412656. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2024.2412656

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., and Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative research methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Higher Education and Research Act. (2017). c.64 to 67. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/29/contents/enacted (Accessed January 8, 2025).

House of Commons (2024). Student mental health in England: statistics, policy, and guidance. (HC 2024 CBP-8593). London: House of Commons.

Jones, C. S. (2021). An investigation into barriers to student engagement in higher education: evidence supporting ‘the psychosocial and academic trust alienation theory’. Adv. Educ. Res. Eval. 2, 153–165. doi: 10.25082/AERE.2021.02.002

Jones, C. S., and Bell, H. (2024). Under increasing pressure in the wake of Covid-19: a systematic literature review of the factors affecting UK undergraduates with consideration of engagement, belonging, alienation, and resilience. Perspect. Policy Pract. High. Educ. 28:2317316. doi: 10.1080/13603108.2024.2317316

Jones, C. S., and Nangah, Z. (2020). Higher education students: barriers to engagement; psychological alienation theory, trauma and trust; a systematic review. Perspect. Policy Pract. High. Educ. 25:1792572. doi: 10.1080/13603108.2020.1792572

Leach, L. (2016). Enhancing student engagement in one institution. J. Furth. High. Educ. 40, 23–47. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2013.869565

Manville, C., d’Angelo, C., Culora, A., Ryen Gloinson, E., Stevenson, C., Weinstein, N., et al. (2021). Understanding perceptions of the research excellence framework among UK researchers: The real-time REF review. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Martini, M., and Robertson, S. L. (2022). UK higher education, neoliberal meritocracy, and the culture of the new capitalism: a computational-linguistics analysis. Sociol. Compass 16:e13020. doi: 10.1111/soc4.13020

McCabe, G., and Bhardwa, S. (2023). What is the TEF? Results of the teaching excellence framework 2023. The Times Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/tef-2023-results (Accessed January 8, 2025).

McIntosh, S., McKinley, J., Milligan, L. O., and Mikolajewska, A. (2022). Issues of (in)visibility and compromise in academic work in UK universities. Stud. High. Educ. 47, 1057–1068. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1637846

McKendrick-Calder, L., and Choate, J. (2024). Educators’ lived experiences of encountering and supporting the mental wellness of university students. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 43, 180–195. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2023.2218810

Morrish, L. (2019). Pressure vessels: the epidemic of poor mental health among higher education staff. Oxford: Higher Educational Policy Institute.

Nyanjom, J., and Naylor, D. (2021). Performing emotional labour while teaching online. Educ. Res. 63, 147–163. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1836989

O’Leary, M., Cui, V., and French, A. (2019). Understanding, recognising and rewarding teaching quality in higher education: an exploration of the impact and implications of the teaching excellence framework. London: University and College Union.

Office for Students. (2023) About the teaching excellence framework. Available online at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/the-tef/about-the-tef/ (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Office for Students. (2024) National Student Survey – NSS. Available online at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/ (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Rickett, B., and Morris, A. (2021). Mopping up tears in the academy’ – working-class academics, belonging, and the necessity for emotional labour in UK academia. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 42, 87–101. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2020.1834952

Silverio, S. A., Wilkinson, C., and Wilkinson, S. (2021). The powerful student consumer and the commodified academic: a depiction of the marketised UK higher education system through a textual analysis of the ITV drama cheat. Sociol. Res. Online 26, 147–165. doi: 10.1177/1360780420970202

Skea, C. (2021). Emerging neoliberal academic identities: looking beyond Homo economicus. Stud. Philos. Educ. 40, 399–414. doi: 10.1007/s11217-021-09768-7

Snijders, I., Wijnia, L., Rikers, M., and Lovens, S. M. M. (2020). Building bridges in higher education: student-faculty relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. Int. J. Educ. Res. 100:101538. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101538

Somekh, B., and Lewin, C. (2011). Theory and methods in social research. 2nd Edn. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Su, F., and Wood, M. (2023). Relational pedagogy in higher education: what might it look like in practice and how do we develop it? Int. J. Acad. Dev. 28, 230–233. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2023.2164859

Sutton, P. (2017). Lost souls? The demoralization of academic labour in the measured university. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 36, 625–636. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1289365

Thomas, P., McArdle, L., and Saundry, R. (2020). Introduction to the special issue: the enactment of neoliberalism in the workplace: the degradation of the employment relationship. Compet. Change 24, 105–113. doi: 10.1177/1024529419882281

Thornicroft, G., Sunkel, C., Alikhon Aliev, A., Baker, S., Brohan, E., El Chammay, R., et al. (2022). The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. London, England: Lancet. 400, 1438–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2

Tight, M. (2019). Higher education research, the developing field. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Troiani, I., and Dutson, C. (2021). The neoliberal university as a space to learn/think/work in higher education. Archit. Cult. 9, 5–23. doi: 10.1080/20507828.2021.1898836

Whitsed, C., Girardi, A., Williams, J. P., and Fitzgerald, S. (2024). Where has the joy gone? A qualitative exploration of academic university work during crisis and change. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 43:2339836. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2024.2339836

Wray, S., and Kinman, G. (2021). Supporting staff wellbeing in higher education. Project report. Education Support, London, UK. Available online at: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/47038/1/FINALES%20Supporting%20Staff%20Wellbeing%20in%20HE%20Report.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2025).

Keywords: higher education, staff, pressure, COVID-19, neoliberalism, students, mental health

Citation: Jones CS and Bell H (2025) Post-pandemic pressures in UK higher education: a qualitative study of neoliberal impacts on academic staff and the unavoidable truths. Front. Educ. 10:1627959. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1627959

Edited by:

María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera, Universidad de las Américas, ChileReviewed by:

Amanda Nuttall, Leeds Trinity University, United KingdomAlejandro Hernández Chávez, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Jones and Bell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caroline Sarah Jones, Yy5qb25lc0BtbXUuYWMudWs=

Caroline Sarah Jones

Caroline Sarah Jones Huw Bell

Huw Bell