- Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla, Thailand

Building on prior research that applies Conversation Analysis (CA) insights to teaching conversation in Thai EFL contexts, this study proposes and evaluates the Conversation Analysis-informed Teaching (CA-T) Model, a novel pedagogical approach to developing EFL learners' conversation skills. A quasi-experimental study was conducted with 12 conveniently sampled Thai EFL teachers (Grade 6: n = 3; Grade 9: n = 5; Grade 12: n = 3; undergraduate: n = 1) and their students across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in southern Thailand. Teachers received structured training in the CA-T approach before implementing semester-long unit plans with specially developed instructional materials. Students' overall English proficiency and conversational abilities were assessed through pre- and post-instruction direct and indirect tests. Statistical analyses revealed significant improvements across all educational levels (p < 0.01), further supported by positive qualitative feedback from teacher and student group interviews. Teachers expressed a strong intention to continue using the CA-T model in their classrooms, while students reported satisfaction with their conversational achievements. These encouraging results support a systematic national integration of CA insights into EFL speaking curriculum design, empowering learners at all levels to strengthen conversational skills and effectively leverage abundant online recorded talk resources. The findings further suggest that integrating CA principles into English conversation instruction can enhance learners' interactional competence, motivation, and ability to engage with naturalistic spoken English, supporting the potential for broader application of CA-informed pedagogy in EFL contexts through authentic, naturally occurring materials and scaffolded, action-oriented instruction.

1 Introduction

English language proficiency has long been a priority in foreign language curricula globally, including in Thailand. Yet a persistent question remains: how can these curricula be implemented to effectively develop learners' real-world English communication skills, particularly in speaking? In response to UNESCO's call for education that prepares global citizens for 21st-century challenges, including effective navigation of the digital, borderless world [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2014], Thai national policy has actively promoted global citizenship education, placing strong emphasis on communicative competence. Concurrently, the pursuit of international recognition has become a major impetus for institutional internationalization efforts. In this environment, it is therefore an especially opportune time for educators and policymakers to critically assess what has been accomplished and to consider what further steps are needed to better equip Thai youth with the English language skills necessary for global engagement.

Rather than dwelling on recurring reports of Thailand's consistently low performance on English proficiency indices (EF English Proficiency Index, 2022; Sunil, 2022), it is more productive to examine the persistent classroom realities contributing to this issue. This particularly applies to the teaching of foundational skills like English conversation, where exploring strategies for meaningful improvement is crucial. In fact, numerous challenges related to the development of Thai learners' speaking skills have been identified in prior studies of English language education in Thailand, which warrant serious attention. These include a shortage of qualified English teachers, inadequate teacher training and ongoing support, excessive school-related workloads, limited access to teaching and learning resources, and a prevailing emphasis on exam-oriented language instruction (Baker and Jarunthawatchai, 2017; Chanaroke and Niemprapan, 2020; Sinwongsuwat et al., 2018). Additionally, Thai students have been reported to struggle with speaking and understanding English, lack opportunities to practice the language outside the classroom, and often assume passive, dependent roles in the learning process (Bruner et al., 2015; Sanitchai and Thomas, 2018; Ulla et al., 2022).

To address these challenges, particularly the insufficient training and support for teachers, coupled with the absence of research-based, up-to-date instructional models and resources for teaching English conversation, this study draws on insights from Conversation Analysis (CA) to develop a pedagogical approach tailored to Thai EFL teachers and learners. Originating in sociology in the 1960s through the seminal work of Harvey Sacks and his collaborators (Heritage, 1984; Jefferson, 1992; Sacks, 1995; Sacks et al., 1974; Schegloff, 2013), CA offers a powerful analytic toolkit for uncovering the methodical, systematic organization of all forms of talk-in-interaction, beyond just ordinary conversation. These insights are applicable across a wide range of professions, including language education. Subsequently, CA has been increasingly applied beyond its sociological roots, influencing fields such as linguistics, psychology, anthropology, cognitive science, and communication studies. Notably, in the early 2000s, interactional linguistics emerged as a CA-informed discipline, prompting efforts to integrate CA into applied domains such as second language (L2) acquisition and language pedagogy (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting, 2001; Kasper and Wagner, 2014).

With its methods, principles, and empirical findings on the systematic nature of talk-in-interaction, CA has profoundly influenced various areas of applied linguistics, especially the study of L2 acquisition, language use, and education. Within L2 education, CA offers valuable resources for teachers to closely examine classroom interaction dynamics, enabling them to assess learner participation, identify learning opportunities, and critically reflect on their own instructional practices (Hale et al., 2018). By revealing the sequential organization of talk and the reflexive relationship between pedagogy and interaction, CA facilitates a more nuanced evaluation of how curriculum is enacted in real-time and how it can be improved (Koshik et al., 2002; Pourhaji and Alavi, 2015; Sert and Seedhouse, 2011). Moreover, CA insights have informed the development of teacher training programs and instructional materials that support more effective teaching of conversational competence in EFL contexts (Wong and Waring, 2010a). These contributions position CA as a powerful theoretical and practical resource for addressing enduring challenges in English language classrooms, particularly in settings like Thailand where communicative competence remains a key educational priority.

This study, therefore, aims to propose and evaluate the CA-T Model, a Conversation Analysis-informed teaching model that evolved from the author's previous classroom-based research on teaching English conversation skills in Thailand. Designed for implementation by local teachers, the model incorporates structured scaffolding, authentic materials, and action-oriented learning. Specifically, the study addresses two key questions: (1) How effective is the CA-T Model in improving Thai EFL learners' conversational skills? and (2) What are teachers' and learners' perceptions of the CA-T pedagogical approach? To investigate these questions, a quasi-experimental study was conducted involving Thai EFL teachers and learners at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in southern Thailand.

This paper is structured as follows: First, an overview of CA-informed English conversation instruction in Thai contexts is provided, followed by a detailed description of the CA-T Model. The methodology section then outlines the training of teacher participants and the implementation of CA-T materials in their English conversation lessons. The subsequent section presents the results of the model's implementation, followed by a discussion of how CA-T materials can be further optimized for classroom use. The paper concludes with practical recommendations and directions for future research.

2 Conversation Analysis (CA)-informed approaches to EFL conversation teaching

Over the past decade, there has been growing scholarly and pedagogical interest in applying Conversation Analysis (CA) findings to L2 teaching. This has prompted a shift toward the explicit instruction of conversation and language in interaction (Barraja-Rohan, 2011; Kasper, 2017; Kassaye, 2021; Lin and Lo, 2016; Siegel and Seedhouse, 2019; Sinwongsuwat et al., 2018; Wong and Waring, 2010a), alongside the increased incorporation of authentic materials into L2 classroom instruction (Tran, 2022). The use of CA-informed transcription in conversation lessons enables learners not only to notice spoken language features such as pauses, stress, rhythm, and intonation, but also to recognize the interactional practices that structure real-time talk. These practices include turn-taking, sequencing, overall conversation organization, overlap, and repair, all essential for helping learners navigate conversational challenges and participate more effectively in the target language.

Beyond its benefits for learners, CA also offers teachers a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying the challenges students face during classroom interaction. CA practitioners have long emphasized its value in examining various aspects of classroom discourse, particularly the dynamic, moment-by-moment unfolding of interactional micro-events (Sert and Seedhouse, 2011). CA can be used to uncover and explain the specific difficulties learners encounter as they navigate different interactional scenarios on their path to becoming more proficient L2 speakers (Bowles, 2006). As noted by Barraja-Rohan (2011) and Fujii (2012), CA is useful not only useful for analyzing learner talk-in-interaction but also for assessing it and diagnosing the underlying causes of interactional breakdowns. Moreover, CA equips learners to reflect on their own interactional practices, including problematic exchanges, thereby enhancing their self-awareness and ability to improve over time (Clifton, 2011).

While CA-informed pedagogy has become increasingly influential in Western contexts since the foundational work of Seedhouse (2004, 2005), a steadily growing body of applied CA research has also emerged in Asian and other Eastern educational settings. Scholars have examined how teachers and learners utilize resources such as repair and turn-taking to accomplish pedagogical and communicative goals (Akmaliyah, 2014; Matsui, 2014; Van Canh and Renandya, 2017), and how interaction is shaped by sociocultural and linguistic contexts (Li and Norton, 2019; Wong and Waring, 2010b). In Thailand, the application of CA in EFL teaching remains relatively new, with early efforts emerging in the 2010s. Notably, Teng and Sinwongsuwat (2015a,b) were among the first to advocate the systematic incorporation of CA insights into Thai EFL instruction. Their studies highlighted the value of making the features of naturally occurring talk, particularly everyday conversation, visible to learners, and using this knowledge to develop awareness of interactional practices. Non-scripted role-plays were especially encouraged, as they provide learners with more authentic opportunities to engage in dynamic, co-constructed interaction that more closely resembles real-life conversation (Naksevee and Sinwongsuwat, 2014). Subsequent studies confirmed that university students who received explicit CA-informed instruction demonstrated greater conversational competence, heightened sensitivity to interactional norms, and increased confidence in speaking English compared to their peers taught through conventional approaches (Sinwongsuwat et al., 2018; Sitthikoson and Sinwongsuwat, 2017).

Compared to more widely adopted approaches such as Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) and Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), CA offers a more empirically grounded and interactionally precise framework for teaching conversation. While CLT and TBLT emphasize fluency and meaning-focused tasks, they often overlook the fine-grained mechanisms of interaction that underpin effective real-world communication. In contrast, CA draws on naturally occurring conversational data to inform instruction, enabling learners to develop turn-by-turn sensitivity and a clearer understanding of how social actions are constructed and interpreted in talk.

The present study builds on this expanding body of CA-informed research, extending its application beyond tertiary settings. Drawing from earlier classroom-based studies conducted by Sinwongsuwat and her research team (see, e.g., Dema and Sinwongsuwat, 2021; Sinwongsuwat and Nicoletti, 2020; Tantiwich and Sinwongsuwat, 2021), this study translated these insights into a more comprehensive and scalable instructional framework. Through a series of professional development workshops with local schoolteachers, findings from earlier pilot work were refined into a structured, teachable approach: the CA-T Model. The CA-T Model operationalizes CA principles in ways that are both pedagogically accessible and contextually adaptable to Thai EFL classrooms at multiple educational levels.

The following section outlines the theoretical foundations and pedagogical components of the CA-T Model, followed by its implementation and evaluation across primary, secondary, and tertiary classrooms.

3 The CA-T Model

The CA-T Model is a curriculum framework grounded in a Conversation Analysis (CA)-informed approach to enhancing Thai EFL learners' English conversation skills. It is based on a set of interrelated beliefs concerning the nature of language and language learning, the needs of EFL learners, and the role of EFL teachers.

3.1 Language and language learning

Language is viewed as a resource for performing social action, and language learning occurs as learners use, or attempt to use, that resource to achieve goals within situated interactional contexts. In this view, everyday conversation serves as the primary habitat of both language use and language learning (Ford et al., 2003; Hall, 2004; Schegloff, 1995; Seedhouse, 2004; Walsh, 2006). Accordingly, conversation lessons should be driven by interactional goals and organized around accomplishing particular social actions, using a range of linguistic and interactional resources that learners can apply in real-time communication.

3.2 EFL learners

EFL learners, particularly those with limited exposure to the target language outside the classroom, require instructional environments that:

1. Provide regular direct or indirect exposure to naturally occurring or near-natural L2 conversation in class;

2. Raise awareness of the differences between written and spoken language, and the interactional practices characteristic of conversation;

3. Make explicit what learners are expected to do in functionally meaningful contexts at each stage of learning;

4. Encourage learners to reflect on and talk about what they are learning;

5. Offer sufficient scaffolding to support the gradual development of natural language use in real-world interactional settings; and

6. Promote learner autonomy through structured self-study activities (e.g., language-in-talk logs).

3.3 EFL teachers

Despite the considerable challenges in teaching productive skills such as EFL speaking, advancements in digital technology have made natural language input and research-based insights more accessible than ever. This creates new opportunities to empower EFL teachers. By engaging teachers in curriculum design, providing targeted training on what and how to teach, and offering continuous expert coaching and peer support, the CA-T Model enables teachers to deliver effective conversation instruction with increased confidence.

3.4 Key features of the CA-T Model

The CA-T Model is characterized by the following key pedagogical features: regular exposure to natural or near-natural conversational input; explicit awareness-raising of the structure and mechanisms of conversation and language-in-interaction; interactional-context-based teaching of vocabulary and grammar; lessons organized around interactional goals and social actions; explicit instruction of conversation; a structured sequence of scripted conversation practice followed by non-scripted role-play; authentic performance assessment aligned with CA-informed criteria; monitored self-study tasks such as language-in-talk logs; and continuous professional support through expert coaching and teacher collaboration.

By establishing a coherent and accessible framework for conversation instruction, the CA-T Model addresses the needs expressed by Thai EFL teachers in the author's pilot project. Teachers are supported through fully developed CA-informed materials, including flexible video clips of model conversations and a practical assessment rubric, designed to promote successful implementation across diverse classroom contexts.

4 Methodology

Supported by the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), this quasi-experimental study aimed to enable EFL teachers, particularly those in the southern border provinces of Thailand, most of whom are Thai nationals, to recognize and understand the authentic nature of conversation and the language they are expected to teach. The intervention also sought to build teacher confidence in organizing conversation lessons for students with limited exposure to English outside the classroom, using a peer-support system. In addition to improving instructional practice, the study aimed to develop teachers' ability to collect performance data and diagnose learner problems in English conversation more effectively. It was anticipated that the CA-informed approach would yield broader benefits for Thai EFL teachers and learners, contributing to the development of more critical learning skills and stronger interactional competence among Thai students.

The study specifically aims to determine the effectiveness of the proposed CA-T instruction model in improving Thai EFL learners' English conversation skills; examine obstacles to the model implementation; explore teacher and student satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the teaching and learning process; and evaluate the usefulness of the CA-informed educational materials developed.

4.1 Participants and setting

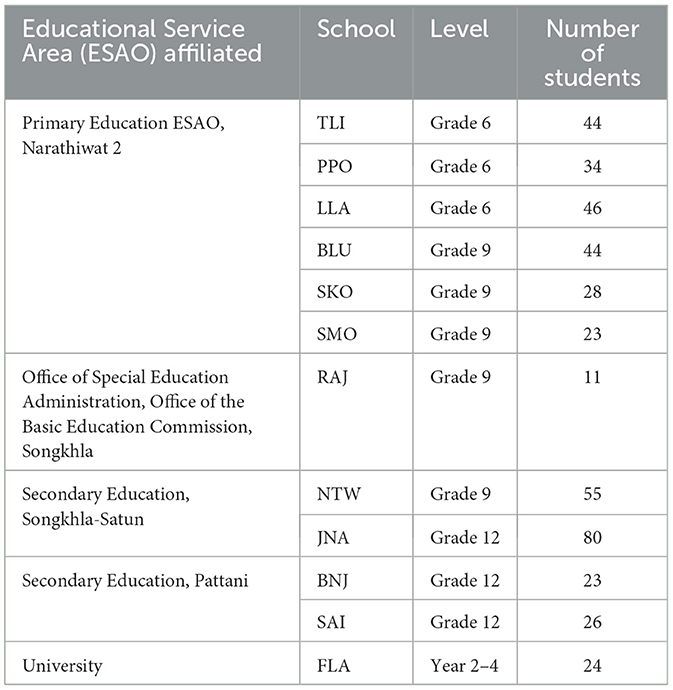

The target population for this study comprised Thai EFL teachers and learners across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in Thailand's southern border provinces of Songkhla, Pattani, and Narathiwat. Student participants were specifically drawn from Grade 6, Grade 9, Grade 12, and undergraduate English conversation classes. These particular grade levels were chosen for two key reasons: they aligned with a prior pilot project conducted by the author, which involved teachers at these stages, and selecting learners in their final year of each educational tier provided optimal opportunities to elicit more substantial conversational performance and to support their transition to the next academic level.

A total of 12 teachers and their respective student cohorts were conveniently sampled from various schools. The participating teachers held bachelor's and master's degrees, bringing diverse experience with teaching durations ranging from 2 to 27 years. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary. While convenience sampling limited the generalizability of findings, it allowed access to real-world classrooms where the CA-T model had practical relevance.

All teacher participants completed a 15-h CA-T Model training workshop series on using insights from CA and CA-informed instructional materials to develop learners' conversational competence, with a minimum attendance requirement of 80%. Prior to implementation, a pre-treatment readiness survey was administered to evaluate teachers' preparedness to deliver CA-informed instruction and to collect initial feedback on the model and accompanying materials. Survey results indicated that at least 90% of participating teachers expressed strong to moderately strong agreement (i.e., ratings of 3–5 on a 5-point Likert scale) that they would:

• implement CA-T lessons organized around interactional goals and social actions;

• use natural or near-natural English talk and its CA-informed representations;

• teach vocabulary and grammar in context with a focus on functional language use;

• emphasize non-scripted role-play practice;

• apply the CA-informed rubric for assessing student performance;

• integrate recommended self-study tasks and conversation corpora, and

• seek support from the established network of CA-T coaches and peers as needed.

Teachers also confirmed that their schools were equipped with adequate infrastructure to support implementation throughout the semester. They reported that their students were ready to participate in both online and offline lessons, though most preferred face-to-face instruction for greater classroom engagement. Teachers expected the CA-T Model to enhance students' motivation and encourage more active English use. Regarding CA-informed transcription symbols, most acknowledged their pedagogical value but expressed concern that students might initially struggle with unfamiliar conventions. To address this, teachers were encouraged to introduce the symbols early in the semester and reinforce them throughout the course.

To ensure consistency in the delivery of the CA-T pedagogical model across educational sites, the study incorporated structured mechanisms for monitoring implementation fidelity. All participating teachers joined a Line group where they could ask questions or raise concerns about CA-informed training and materials. During the semester, regular check-ins were conducted by the project team to assess adherence to the teaching model and provide formative feedback. Additionally, mid-semester developmental workshops were organized to facilitate collaborative reflection, troubleshoot implementation challenges, and reinforce shared instructional goals. These measures helped ensure that variation in learner outcomes could be more confidently attributed to the CA-T intervention rather than inconsistencies in instructional delivery.

Students were required to complete an online English proficiency test hosted by Cambridge Assessment English (https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/test-your-english/) both before and after the CA-T intervention. Grade 6 and Grade 9 learners took the Young Learners version, while Grade 12 and undergraduate students completed the General English version. These assessments provided CEFR-aligned baseline and post-instruction data on learners' overall proficiency.

Due to the real-world classroom constraints and ethical considerations related to withholding potentially beneficial instruction, a control group was not used. This is acknowledged as a limitation in the study's design and is discussed in the concluding sections.

Table 1 presents the distribution of participating Thai EFL teachers and their students across the four educational levels and school sites involved in the CA-T intervention study.

4.2 Research design, materials, and assessment

4.2.1 Design overview

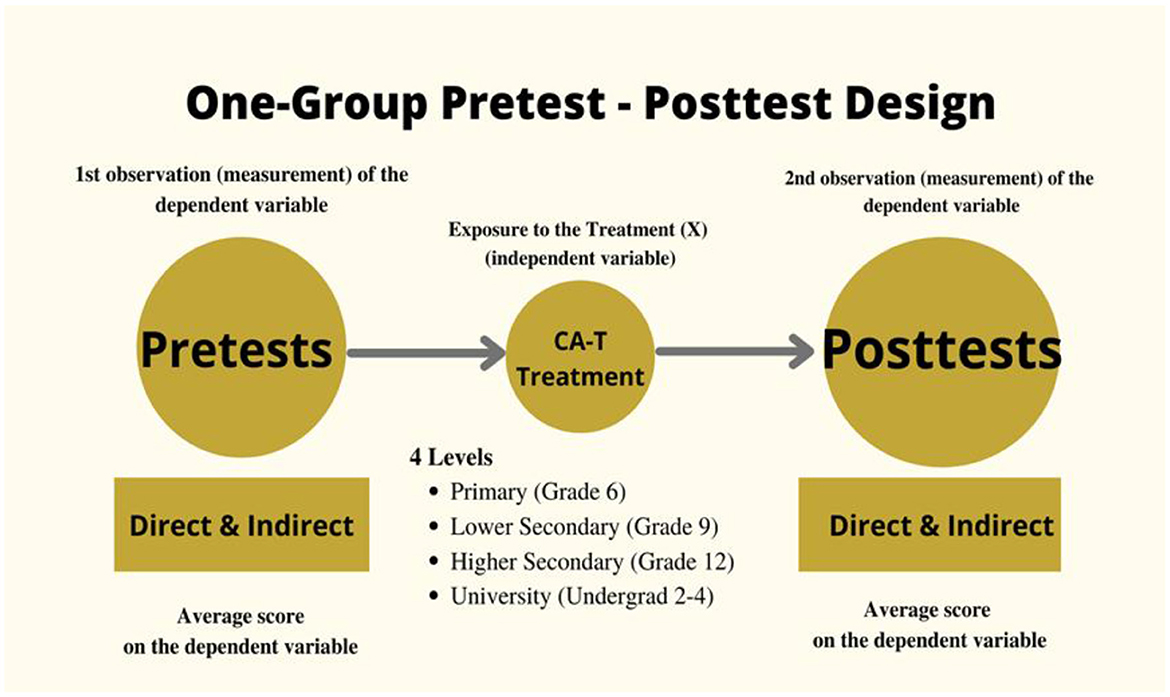

As illustrated in Figure 1, a quasi-experimental design with pre- and post-testing was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the CA-T pedagogical intervention. The primary focus was on measuring students' development in English conversation skills following instruction using the English in Interaction 1-4 CA-informed materials.

4.2.2 Educational materials: English in Interaction series

In alignment with the previously proposed CA-informed approach to teaching English conversation (CA-T), the English in Interaction series comprises CA-informed English conversation lessons organized around everyday social actions and communicative activities. It was specifically designed for Thai EFL learners at key transition points across the educational spectrum; namely, Primary 6 (Grade 6), Lower Secondary 3 (Grade 9), Higher Secondary (Grade 12), and University (Undergraduate Years 2–4).

Available online at https://ca-t.psu.ac.th/, the series covers essential social actions commonly performed in everyday interactions. These include greetings, introducing oneself and others, making small talk, leave-taking, inviting, making requests, expressing and returning gratitude, offering, sharing news and information, complimenting, giving suggestions and advice, dis/agreeing, and news sharing. To ensure accessibility, printed copies of the materials were also distributed to all participating teachers and students.

CA-T lessons were implemented following the administration of both direct and indirect pre-instructional conversation tests, which are described in a later section.

4.2.3 7Cs teaching procedures

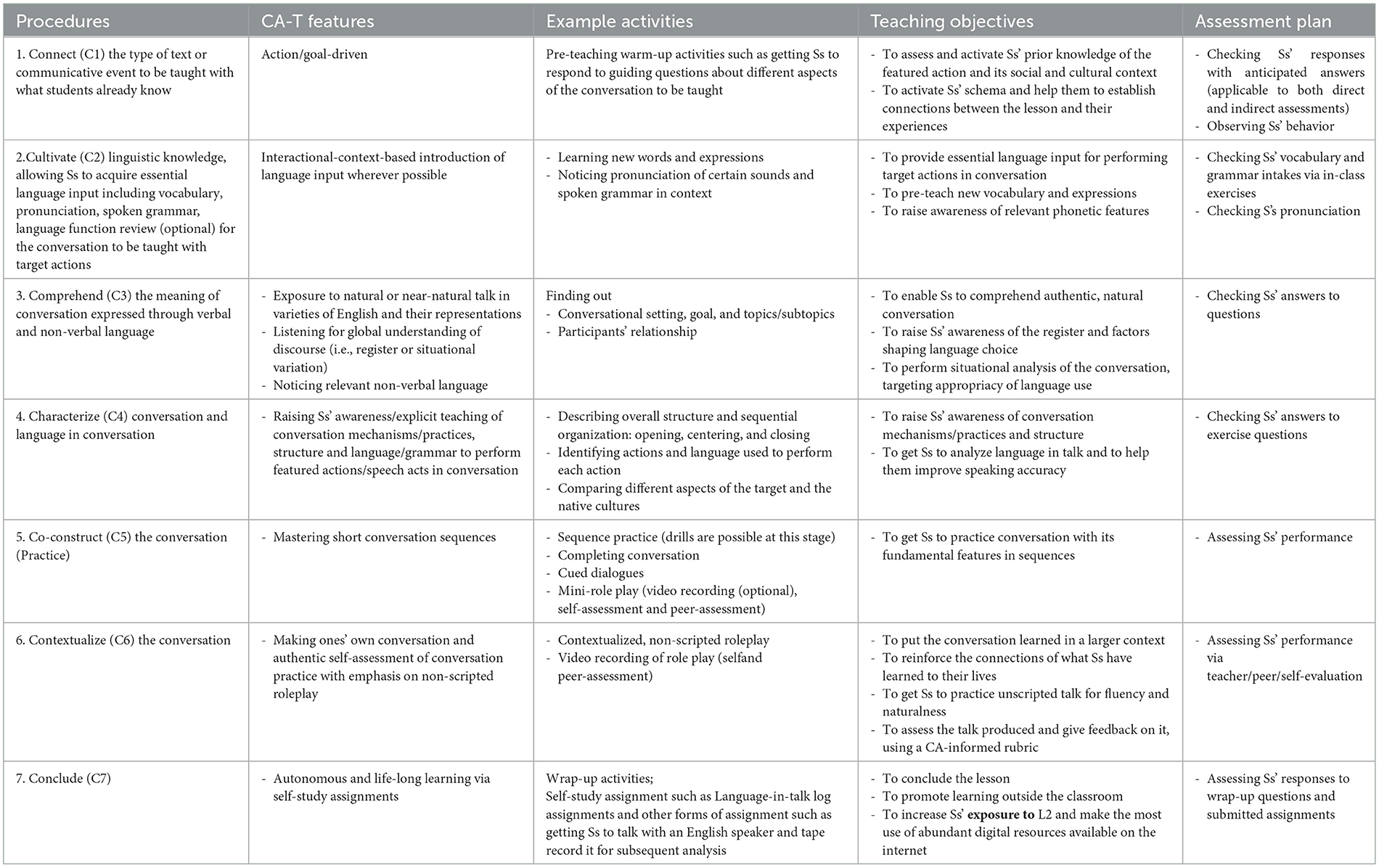

Each CA-T unit is organized around a set of 7Cs teaching procedures, as outlined in Table 2. These procedures are designed to progressively scaffold students' learning, enabling them to ultimately engage in their own English conversations through a non-scripted roleplay task centered on the unit's target actions. Accordingly, they may be referred to as task-oriented 7Cs scaffolding techniques.

Each C of the unit plan can be explained in more detail below:

C1 (Connect) is aimed at activating learners' schema with discussion questions related to social activities or situational contexts involved in the undertaking of the featured actions of the unit. The questions used can be broad or made more specific to the video clip of the conversation to be presented in the following stage. In that case, teachers are recommended to contextualize the questions within the settings of the unit conversation.

C2 (Cultivate) not only helps learners increase new words and grammar but improves their existing vocabulary and grammar knowledge. Taken primarily from the model conversation provided, choices are made primarily on the salience of the words and grammar constructions in performing target actions, their frequency in use, and challenges experienced by learners in using them. Teachers need to make sure the vocabulary choice is not far beyond the target vocabulary level learners are expected to reach especially in terms of their pronunciation and use.

C3 (Comprehend) is designed to help learners' reach the global understanding of the model conversation they are going to watch or listen to. At this stage, they are made especially aware of such factors shaping the conversation as its setting, main goal, relationship between speakers, and social actions involved.

C4 (Characterize) is a very important step in the CA-T process as learners are taught how to examine conversation and language to organize social actions in the conversation with CA insights.

C5 (Co-construct) gets learners to gradually construct the target conversation together, making sure they master one small, manageable sequence at a time via primarily scripted practice.

C6 (Contextualize) puts the learners in free conversation practice as they are engaged in non-scripted talk contextualized in the local conversation context they can associate with.

C7 (Conclude) engages both teacher and learners in reflecting on what has been learned from the entire unit, especially to make sure the learners not only understand what is expected of them in their own self-study practice but also can actually achieve the target learning outcomes of the unit.

4.2.4 CA-T assessment and data analysis

This section describes the instruments used for data collection, including surveys, interviews, and performance assessments, as well as the methods employed for data analysis.

4.2.4.1 Data collection instruments

Pre-treatment surveys were administered to teachers to gauge their readiness to implement CA-informed instruction and to collect their initial views on the CA-T model and its associated materials. This survey assessed participants' familiarity with key features of the CA-T approach, such as interactional goal-driven instruction, contextualized grammar and vocabulary teaching, the use of naturalistic conversation data, CA-informed assessment rubrics, and self-study tools (e.g., language-in-talk logs). It also included items on perceived school readiness and student preparedness for implementing CA-informed lessons.

Following implementation, post-treatment surveys were conducted with both teachers and students, complemented by group interviews. These instruments were used to explore participants' perspectives on the CA-T model's implementation and the use of CA-informed educational materials.

The post-treatment student questionnaire, administered at the conclusion of the CA-T instruction, comprised five sections using a five-point Likert scale. These sections measured (1) students' motivation and engagement, (2) their understanding and perceived usefulness of CA transcription symbols, (3) their evaluations of the seven scaffolded stages of CA-T lessons (7Cs), (4) overall satisfaction with the CA-informed course, and (5) qualitative reflections elicited through open-ended prompts. The items were designed to assess students' perceived learning gains in conversation, their awareness of spoken language features, and confidence in speaking English.

Post-treatment teacher surveys and semi-structured group interviews with both teachers and students further explored participants' experiences with the CA-T model, implementation challenges, and suggestions for improvement.

To evaluate student learning outcomes and the effectiveness of the CA-T Model, both direct and indirect conversation assessments were administered before, during, and after instruction. These assessments were designed to measure improvements in students' conversation skills and broader English proficiency. Prior to and following the intervention, three forms of assessment were employed:

1. An online CEFR-aligned English proficiency test (as previously described) to assess students' overall language development.

2. An indirect conversation test, a paper-based multiple-choice test modeled after the Ordinary National Educational Test (ONET), required at Grades 6, 9, and 12 under the Basic Education Core Curriculum, B.E. 2551. Each version of this ONET-substitute test included 30 items requiring students to select the most pragmatically appropriate conversational responses.

3. A direct conversation test, implemented through a role-play task, designed to assess students' interactional performance before and after CA-T instruction. Performance was evaluated using a CA-informed rubric developed by the research team (see Appendix). The role-play task served as the summative performance-based assessment of conversational competence.

During the course of instruction, formative assessment was integrated into each lesson. This included teacher observation of students' participation in class activities such as question-answer tasks, dialogue completions, pair work, and scaffolded role-play practices. These formative checkpoints were used to monitor learners' incremental development and to inform teaching.

4.2.4.2 Data analysis

Quantitative data from the surveys and assessments were analyzed using descriptive statistics. To determine the impact of the CA-T intervention, pre- and post-test scores from both the indirect and direct assessments were compared using a paired-sample t-test. On the other hand, qualitative data, including responses to open-ended survey questions and interview transcripts, were examined using content analysis to identify recurring themes related to implementation feasibility, learner engagement, and perceived instructional value. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and subjected to this analysis. Although a qualitative micro-analytic comparison of selected pre- and post-instruction student role-play samples was also conducted using CA transcription and analysis techniques to support triangulation, the results of this analysis are not presented in the current paper and will be reported in future publications.

5 Results

This section presents the results of the study, which aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed CA-T Model in enhancing English conversational skills of Thai EFL learners across all educational levels. It also explores potential barriers to the model's implementation, as well as teacher and student satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the CA-informed instructional materials used. The findings are organized into four thematic areas: quantitative performance outcomes, teacher implementation and perceptions, learner engagement and feedback, and recommendations for enhancing the CA-T model's implementation.

5.1 Quantitative performance outcomes: learners' conversation skill improvement

To evaluate the effectiveness of the CA-T pedagogical model in enhancing Thai EFL learners' conversational performance, students were assessed using both indirect and direct conversation tests administered before and after instruction. Quantitative analysis revealed statistically significant improvements across all educational levels—Grades 6, 9, 12, and undergraduate. Two assessment types were employed. The indirect test, modeled after Thailand's Ordinary National Educational Test (ONET), consisted of 30 multiple-choice items targeting pragmatic appropriateness and conversation completion. The direct test involved a role-play task, evaluated using a CA-informed analytic rubric adapted from Dema and Sinwongsuwat (2021) and Youn (2020) (see Appendix). The rubric assessed three key dimensions of interactional competence: (1) language use in turn construction (e.g., pronunciation, intonation, vocabulary, grammatical accuracy, and non-verbal behavior); (2) turn delivery and allocation (e.g., fluency, timing, and turn transition strategies); and (3) sequential organization and discourse structure (e.g., adjacency pair completion, coherence, and content engagement). Each criterion was rated on a 3-point scale.

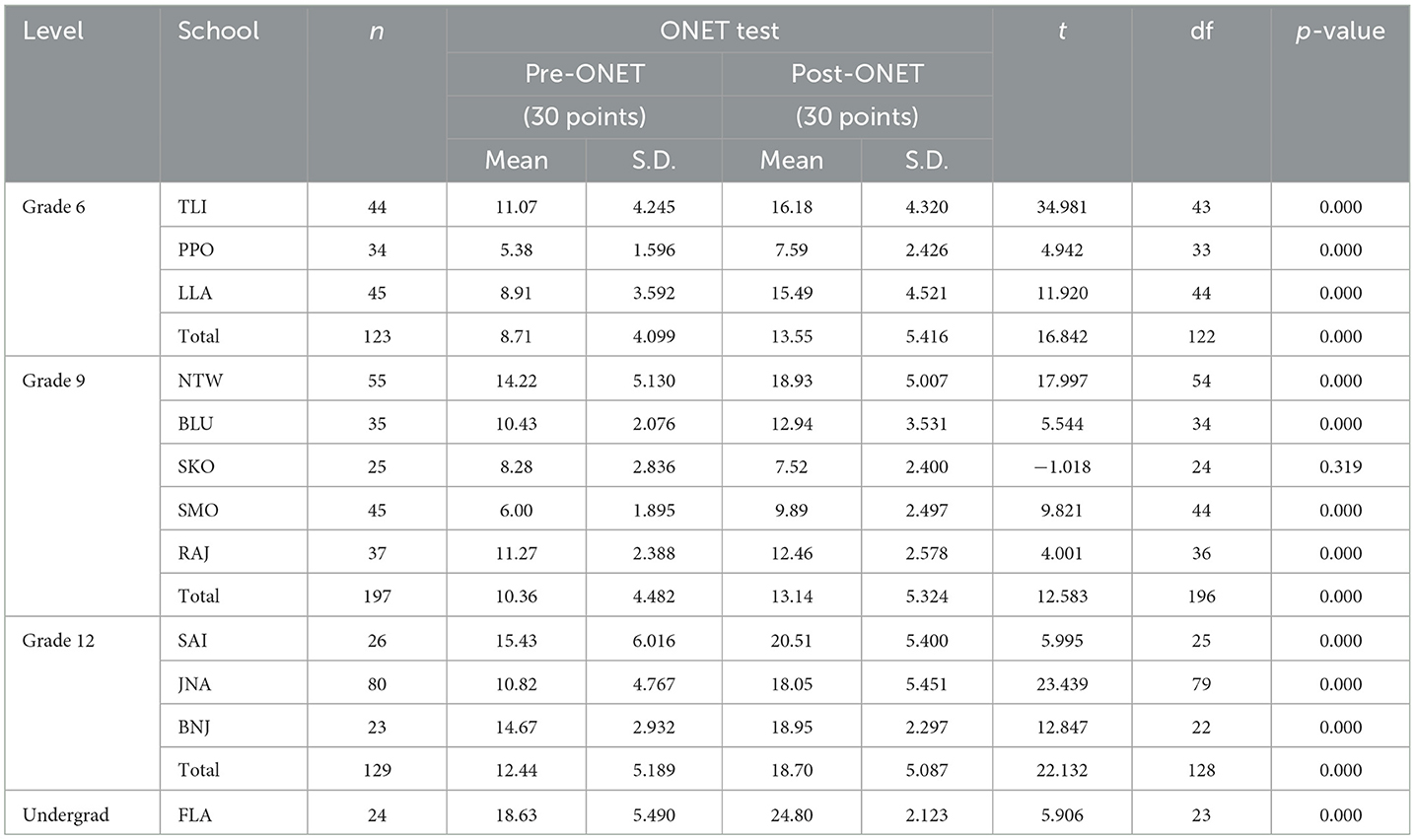

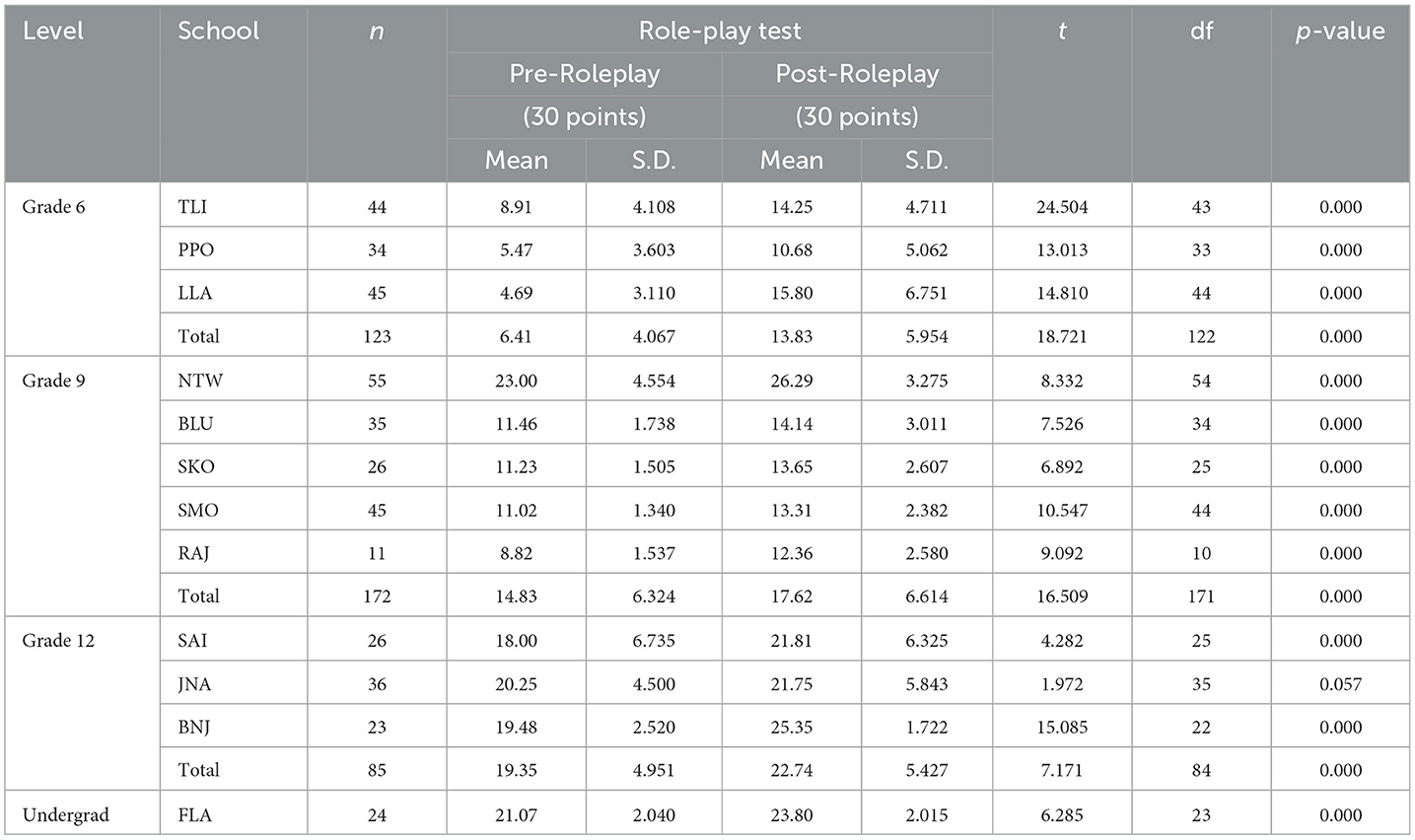

A comparison of pre- and post-test scores showed consistent improvement across all levels. Paired-sample t-tests confirmed that these gains were statistically significant (p < 0.01), providing robust evidence for the instructional impact of the CA-T intervention. Results of the ONET-substitute test are presented in Table 3.

In the indirect test, which assessed students' ability to produce pragmatically appropriate responses within conversational contexts, post-test results indicated statistically significant improvements across all participant groups (p < 0.01). Similarly, in the direct role-play test, students demonstrated enhanced ability to manage turn-taking, initiate and respond to adjacency-pair sequences, perform repair, and maintain conversational coherence, core components of interactional competence as defined in Conversation Analysis.

Despite these overall positive outcomes, notable discrepancies emerged at two school sites. Students at SKO School showed significant gains in the direct test but not in the indirect one, while students at JNA School improved only in the indirect test. Follow-up interviews with the teachers suggested that these inconsistencies were likely the result of external constraints on instructional time. The SKO teacher reported limited opportunity to prepare students for the indirect post-test due to overlapping school activities, whereas the JNA teacher described difficulty maintaining consistent role-play practice, as students were frequently occupied with extracurricular commitments.

Overall, comparisons of pre- and post-test scores on the ONET-substitute test revealed statistically significant gains (p < 0.01) at all educational levels following the semester-long CA-T intervention. A similar pattern of improvement was observed in the direct role-play test, as presented in Table 4.

These positive student outcomes attest to the successful implementation of the CA-T pedagogical model in English conversation teaching across the participating sites. This success was further supported by teachers' reaffirmation of their initial readiness to adopt the model, as evidenced in post-teaching surveys and group interviews. With the exception of a single school located in a remote valley in the deep South, where unstable internet connectivity posed challenges, teachers confirmed the practicality and applicability of the CA-T lessons across all implementation domains.

However, a closer inspection of the test score data revealed some variability at the school level. While all groups improved overall, students at SKO School demonstrated statistically significant gains only on the direct conversation test, whereas students at JNA School improved significantly only on the indirect test. Time constraints appeared to be a contributing factor in both cases. The SKO teacher reported insufficient time to prepare Grade 9 students for the indirect post-test due to overlapping school activities. Similarly, the JNA teacher explained that her Grade 12 students had limited exposure to role-play practice throughout the semester, as they were frequently involved in extracurricular commitments, including city-sponsored events and sports tournaments, which disrupted the instructional sequence.

These contextual challenges likely explain the uneven gains observed at those schools. Nonetheless, the statistically significant differences between pre- and post-test scores, alongside qualitative evidence from student role-play performances and group interviews, strongly reaffirm the positive outcomes reported in earlier studies (e.g., Teng and Sinwongsuwat, 2015b; Sinwongsuwat et al., 2018). Taken together, the findings support the value of systematically integrating CA insights into EFL speaking curriculum design across educational levels.

5.2 Teacher implementation and perceptions

Teacher surveys and interviews provided additional insights into the implementation of the CA-T model. Pre-treatment survey data indicated strong initial readiness, with over 90% of participating teachers agreeing or strongly agreeing (on a 5-point Likert scale) that they felt prepared to implement CA-informed instruction. They reported confidence in their ability to deliver action-oriented lessons, integrate CA transcription conventions, and apply the CA-informed rubric to assess student performance. Post-instruction feedback reinforced these findings. In group interviews, teachers affirmed the pedagogical value of the CA-T model and its materials, including the English in Interaction series. Many expressed interest in expanding the model's use to additional grade levels, citing increased student engagement and motivation in conversation lessons. Teachers also emphasized the effectiveness of the 7Cs framework in scaffolding lesson delivery and facilitating interactional learning.

While the model was found to be generally adaptable across classroom contexts, some implementation challenges were noted. In particular, one school located in a remote area reported unstable internet access, which hindered the use of online CA-T materials. Nevertheless, all participating teachers successfully implemented the full sequence of CA-T lessons. Several voiced intentions to adapt the materials to better reflect culturally relevant content and to design new tasks aligned with CA-T principles.

During group interviews, teachers enthusiastically shared their plans to:

• Develop materials using the CA-T model for additional student levels not currently covered;

• Create supplementary worksheets featuring diverse speaking scenarios for practicing expressions learned in class;

• Design more innovative, student-centered activities to foster active learning of English conversation both in and out of the classroom; and

• Use authentic settings to enhance the realism of role-play activities—an idea also encouraged by one school director.

Additionally, some teachers expressed aspirations to advance their professional development through the creation of original CA-T-informed teaching resources. Notably, one participant suggested that the CA-T pedagogical approach could also be applied to teaching other foreign languages, such as Arabic.

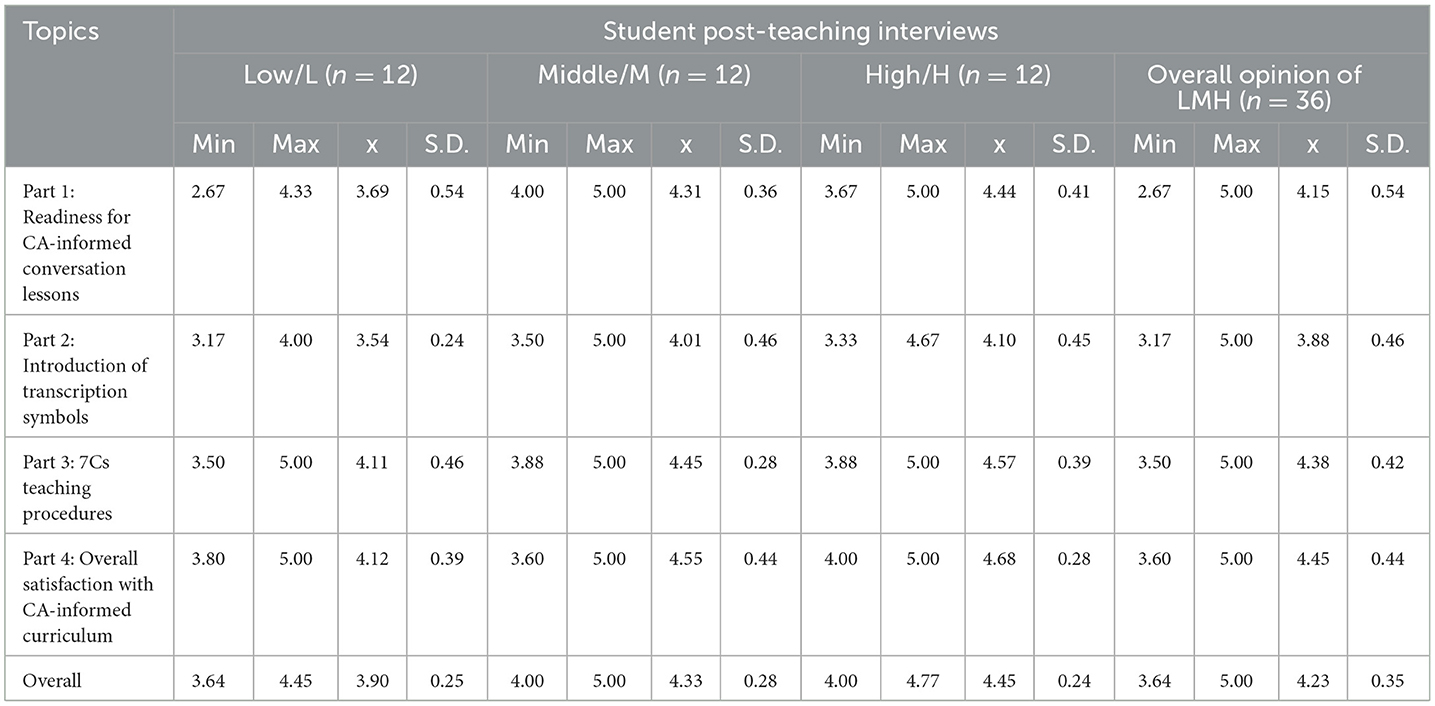

5.3 Student engagement and learning experience

To evaluate learners' perspectives on the CA-T instruction, group interviews were conducted in conjunction with a verification Likert-scale survey administered to selected students. As shown in Table 5, students across all educational levels and performance bands (Low, Mid/Intermediate, and High) responded positively to the CA-T lessons. The overall mean satisfaction score was 4.23, which corresponds to a “strong” level of agreement (cf. 3.50–4.49), indicating that learners found the CA-T instruction engaging, accessible, and effective.

Specifically, students reported feeling motivated to speak English, confident in reading the conversation materials, and active participants in classroom interactions—yielding an overall mean of 4.15 for these core engagement indicators. Qualitative data from group interviews reinforced these quantitative findings. Students expressed that the use of CA-informed transcription symbols significantly supported their understanding of spoken English, particularly in identifying features such as stress, rhythm, and intonation, and in recognizing the differences between written and spoken language. Most students reported little difficulty understanding the symbols and did not confuse them with punctuation used in writing. However, the mean score for this component was slightly lower at 3.88, suggesting that while the transcription symbols were generally well-received, they introduced new conceptual demands that may require further scaffolding and repetition in future instruction.

Regarding the 7Cs scaffolding framework, students reported substantial benefits, with an overall mean score of 4.38. They described each stage of the 7Cs as contributing to their development of English conversation skills. Activities in C1 (Connect) effectively activated prior knowledge and prepared them for new content. C2 (Cultivate) introduced essential vocabulary, pronunciation features, and grammatical structures necessary for carrying out target actions. C3 (Comprehend) helped deepen their understanding of model conversations, particularly through the video clips, which were highlighted as both meaningful and enjoyable.

Through C4 (Characterize), students gained insight into the structural organization of conversation and the functional use of language in interaction. C5 (Co-construct) offered opportunities to rehearse short sequences of conversation in manageable chunks, while C6 (Contextualize) encouraged learners to apply their knowledge in realistic scenarios, building their confidence to use English outside the classroom. Students also appreciated the wrap-up phase of C7 (Conclude), where lessons were effectively summarized and consolidated by their teachers.

Students in the high-performance group appeared to benefit most from the structured 7Cs pedagogy, reporting the highest satisfaction with a mean of 4.57 for the lesson framework and 4.68 for the overall curriculum. Across all groups, the mean satisfaction rating with the CA-T conversation course stood at 4.45, indicating strong approval. Students agreed that the CA-T lessons enhanced their conversational abilities and speaking confidence, provided more authentic speaking opportunities than prior English courses, and helped them learn useful English expressions for real-life communication.

Notably, students reported that the CA-T course had a motivational effect, increasing their willingness to speak English with teachers, peers, and even family members. One memorable instance came from a group of Grade 9 students, who proudly shared that they were able to initiate conversations with foreigners during a field trip to Bangkok—applying expressions they had practiced in class.

5.4 Recommendations for enhancing CA-T Model implementation

While the implementation of the CA-T pedagogical model yielded encouraging results in improving Thai EFL learners' English conversation skills, focus group interviews with participating teachers offered practical suggestions for enhancing its effectiveness across the seven instructional stages. These refinements can help tailor the CA-T lessons to better suit learners at different proficiency levels.

5.4.1 C1 (connect)

At the beginning of each unit, open-ended discussion questions designed to activate learners' background knowledge related to the target social activity should be supplemented with culturally comparative prompts. Encouraging students to reflect on similarities and differences between the target culture and their own promotes intercultural awareness and deeper schema activation, a key factor in the language learning process (Hu, 2012). Teachers should ensure that questions are age-appropriate and engaging, and that the use of the learners' L1, especially at lower levels such as Grades 6 and 9, is allowed to facilitate comprehension and participation.

5.4.2 C2 (cultivate)

This stage should prioritize vocabulary and expressions necessary for understanding the model conversation. These items should be introduced within spoken contexts to support learners' listening comprehension. For younger learners, additional time should be allocated for phonetic awareness training, including decoding IPA symbols that accompany essential words and expressions from various English varieties. Teachers may also need support in phonetic instruction, especially those without a formal background in linguistics. Preview activities are especially beneficial here, as they not only raise student engagement but also prepare learners to recognize key lexical and grammatical features during upcoming tasks (Harmer, 2015; Nation, 2009). Incorporating culturally relevant vocabulary at this stage can further enhance learner engagement.

5.4.3 C3 (comprehend)

To make this stage more dynamic, comprehension exercises should go beyond open-ended questions and incorporate interactive, culturally oriented tasks (Goh, 2015). Younger learners, especially those with literacy challenges, may require multiple listenings, teacher-guided walkthroughs, and additional out-of-class practice to reinforce understanding. Teachers are encouraged to show only the transcribed excerpt of the model conversation, rather than the full video, to reduce download time and avoid cognitive overload.

5.4.4 C4 (characterize)

This phase, often enjoyed by students, helps them recognize the prosodic contours of English speech. Teachers, however, must be prepared to clarify spoken language features represented by CA-informed transcription symbols. More advanced learners may benefit from producing their own transcripts and critically analyzing how symbol placement affects meaning. Providing modified transcripts—with either omitted or repositioned symbols—can further foster critical thinking and deepen learners' interactional awareness (Lee, 2023).

5.4.5 C5 (co-construct)

Learners should begin by practicing short scripted sequences before progressing to unscripted role-plays. Such stepwise practice aligns with Ellis's (2008) principle of manageable task progression, which fosters learner confidence and consolidation. Teachers may introduce alternative ways to perform target actions and expand vocabulary options. At upper levels (e.g., Grade 12 and university), students should receive explicit instruction on conversation sequencing (opening, centering, and closing) as well as on essential interactional practices like turn-taking and repair. Incorporating both metalinguistic and meta-interactional knowledge helps learners grasp interactional norms and better navigate diverse communicative contexts (Lightbown and Spada, 2021).

5.4.6 C6 (contextualize)

Advanced learners should be given more autonomy to create and perform role-plays based on situational prompts of their own design (Piscitelli, 2020), provided they include the target social actions. Younger students, by contrast, tend to prefer illustrated scenarios rather than text-based descriptions, and benefit from teacher guidance in framing the context.

5.4.7 C7 (conclude)

In addition to reflective wrap-up discussions, advanced learners may be assigned post-lesson tasks to reinforce learning. For example, they could be asked to transcribe and analyze an excerpt of natural conversation from movies, YouTube videos, or real-life recordings using CA-informed conventions, identifying the target social actions and contextual features that shape them. Peer performance analysis can also enhance learning. Younger learners, meanwhile, may need more structured review activities and targeted practice identifying turns that accomplish the unit's focal actions.

6 Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of the Conversation Analysis-informed Teaching (CA-T) Model in enhancing Thai EFL learners' conversation skills across primary, secondary, and tertiary educational levels. Drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data, the findings reveal statistically significant improvements in learners' conversational performance, alongside increased classroom engagement and positive perceptions among both teachers and students. These results make a compelling theoretical and practical case for integrating CA into EFL instruction, particularly in contexts where authentic interactional input is limited, and offer a replicable pedagogical model addressing a critical gap in systematic pragmatics instruction. These findings are further discussed in the following subsections, exploring their theoretical implications and pedagogical significance.

6.1 Interpreting learning gains through CA principles

The significant improvements observed in learners' performance on both the indirect conversation test and the direct role-play assessment strongly underscore the pedagogical value of a Conversation Analysis-informed framework for L2 instruction. These findings affirm CA's foundational claim that interaction is not random but methodically organized through recurrent practices such as turn-taking, sequencing, overall structuring, and repair (Sacks et al., 1974; Seedhouse, 2004). By providing systematic exposure to these interactional practices, through both authentic conversation models and guided analysis, the CA-T Model demonstrably enabled learners to more effectively recognize, interpret, and co-construct turns-at-talk. This outcome resonates with previous research indicating that explicit awareness of conversational sequential structure facilitates the development of interactional competence (Barraja-Rohan, 2011; Wong and Waring, 2010a,b). Learners in this study showed improved abilities to initiate, sustain, and close conversations, demonstrating greater control over turn construction and more sophisticated use of linguistic and prosodic resources. By foregrounding clear interactional goals and practices rather than decontextualized language forms, the CA-T Model effectively addresses the insufficient systematic instruction in real-world communication pragmatics, which is a critical gap in Thai EFL education.

6.2 The role of 7Cs scaffolding in developing interactional competence

The observed learning gains are also directly attributable to the structured scaffolding procedures embedded within the CA-T Model, particularly the 7Cs framework. These procedures, ranging from schema activation Connect to reflective wrap-up Conclude, are well-aligned with socio-cognitive and usage-based theories of language learning (Ford et al., 2003; Hall, 2004). By progressively guiding learners from receptive to productive tasks, the 7Cs facilitate learners' internalization of how language is used to accomplish social actions in real-time conversation. Specifically, the progression from scripted to unscripted practice echoes Ellis's (2008) emphasis on meaningful task progression. For Thai EFL learners, who often have limited opportunities for authentic English use outside the classroom, this staged support proved essential for building fluency and confidence in goal-oriented talk.

6.3 Teachers as facilitators of CA-informed instruction

The success of the CA-T Model can also be attributed to the active role played by trained teachers in facilitating learners' interactional development. Beyond delivering CA-T lessons, these teachers supported students in understanding key conversational features, particularly prosodic cues and transcription symbols, while also adapting materials to suit local needs. This supports Hale et al.'s (2018) argument that teacher engagement with CA can empower teachers to systematically analyze classroom talk, identify learner difficulties in interaction, and make principled pedagogical decisions. In this study, teacher familiarity with CA principles and transcription conventions appeared to strengthen their ability to scaffold both interactional understanding and productive language use.

This is consistent with findings from other CA-informed teacher development efforts. Sert (2015) emphasizes the value of interactional awareness in helping teachers notice, interpret, and respond to classroom contingencies in real time. Similarly, Waring and Hruska (2011) found that when teachers are trained to attend to the sequential organization of classroom discourse, they become more effective at promoting learner participation and interactional space. The CA-T project adds to this line of research by demonstrating that even teachers without prior academic training in applied linguistics or discourse analysis can become proficient users of CA-informed methods through sustained professional development and coaching.

Post-implementation interviews with teachers confirmed the model's practicality and adaptability. Several expressed interest in extending its use to other grade levels, adapting materials to include culturally relevant content, and experimenting with new classroom activities grounded in the CA-T framework. One teacher even suggested that a CA-informed approach could benefit the teaching of other foreign languages such as Arabic. These responses suggest that CA-based pedagogy not only enhances learners' interactional competence but also cultivates teacher agency and curriculum innovation, aligning with broader goals of sustainable professional growth in EFL contexts.

Practically, this study offers a replicable model supported by instructional materials, teacher training protocols, and assessment tools, which can be adapted to other under-resourced EFL contexts. The online availability of the English in Interaction series and associated CA-informed tools further increases the model's scalability and accessibility.

6.4 Limitations and directions for future research

While the findings are promising, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The study employed a quasi-experimental design without a control group, which restricts claims of causal attribution. Convenience sampling and geographic specificity (southern Thailand) also limit the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, the long-term durability of learning gains was not assessed. Therefore, future research should examine the sustained development of learners' interactional competence through longitudinal classroom recordings and detailed CA of learner talk; conduct comparative studies involving other pedagogical models (e.g., CLT, TBLT) to clarify the unique contributions of CA-informed instruction; explore adaptations of CA transcription conventions for younger learners; and evaluate the CA-T Model's impacts on other dimensions of oral proficiency, such as fluency, intelligibility, and prosody.

7 Conclusion

This study has successfully demonstrated how English conversation instruction can be meaningfully informed by Conversation Analysis to benefit both teachers and students in EFL contexts. The CA-T Model, developed through prior research and refined in collaboration with Thai EFL teachers, has shown significant promise in fostering learners' interactional awareness, boosting their confidence, and enhancing teachers' instructional capacity, even in environments with limited English exposure. This is notably achieved by engaging lessons that raise explicit awareness of distinct linguistic and interactional resources involved in conversation construction, using authentic or semi-authentic talk excerpts from popular online sources like YouTube. By emphasizing social actions, natural conversation structures, and structured scaffolding through action-oriented tasks, CA-T lessons effectively help learners recognize the interactional underpinnings of spoken English and develop the skills needed to participate meaningfully in real-world communication.

While the current study did not encompass learners from all levels of formal education, its positive findings underscore the feasibility and benefits of systematically embedding CA principles in speaking curricula. Future research should further validate these outcomes through detailed comparative Conversation Analysis of pre- and post-instruction student talk, verifying how various groups of learners' conversational practices improve via CA-informed pedagogy. The development of annotated spoken corpora of action-driven model conversations would also greatly facilitate teachers' lesson planning and students' independent learning, further supporting wider adoption. Additionally, careful examination of classroom interaction is needed to identify how CA-informed pedagogy might be made even more effective.

Ultimately, the advancement of CA-informed pedagogy and the creation of more fulfilling teaching and learning experiences depend on ongoing collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and learners. Sustained dialogue, iterative refinement, and shared reflection will be essential for enhancing the CA-T Model and other approaches aimed at cultivating learners' interactional competence in real-world English communication.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study involving human participants was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Prince of Songkla University (approval No. HSc-HREC-65-010-1-1). The study was conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was granted Fundamental Fund of 2022 by National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) and Prince of Songkla University (Grant No: LIA6505185S).

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the CA-T advisory team and research collaborators whose insights and support were invaluable to the project. Appreciation is also extended to the many teachers, students, and participants who engaged with and supported the research in various capacities. Sincere thanks are due to all who provided encouragement, constructive feedback, and thoughtful guidance throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Portions of this manuscript were refined with the assistance of OpenAI's ChatGPT and Gemini to enhance clarity, coherence, and academic style. All content was meticulously reviewed and verified by the author to ensure accuracy and integrity.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1627966/full#supplementary-material

References

Akmaliyah, N. (2014). Classroom related talks: Conversation analysis of Asian EFL learners. Englisia 2, 1–19. doi: 10.22373/ej.v2i1.323

Baker, W., and Jarunthawatchai, W. (2017). English language policy in Thailand. Eur. J. Lang. Policy, 9, 27-44. doi: 10.3828/ejlp.2017.3

Barraja-Rohan, A. M. (2011). Using conversation analysis in the second language classroom to teach interactional competence. Lang. Teach. Res. 15, 479–507. doi: 10.1177/1362168811412878

Bowles, H. (2006). Bridging the gap between conversation analysis and ESP: an applied study of the opening sequences of NS and NNS service telephone calls. Engl. Specif. Purposes 25, 332–357. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2005.03.003

Bruner, D. A., Sinwongsuwat, K., and Radić-Bojanić, B. (2015). EFL oral communication teaching practices: a close look at university teachers' and A2 students' perspectives in Thailand and a critical eye from Serbia. Engl. Lang. Teach. 8, 11–20. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n1p11

Chanaroke, U., and Niemprapan, L. (2020). The current issues of teaching English in Thai Context. EAU Herit. J. Soc. Sci. Human. 10, 34–45. Available online at: https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/EAUHJSocSci/article/view/243257

Clifton, J. (2011). Combining conversation analysis and reflective practice in the ESP classroom: putting transcripts of business simulations under the microscope. J. Clifton Scripta Manent 6, 25–34. Available online at: https://scriptamanent.sdutsj.edus.si/ScriptaManent/article/view/82/68

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Selting, M., (eds.). (2001). “Introducing interactional linguistics,” in Interactional Linguistics (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 1–22. doi: 10.1075/sidag.10.02cou

Dema, C., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2021). Harnessing conversation analysis-(CA) informed language-in-talk log assignments to improve conversation skills of EFL learners. Lang. Relat. Res. 12, 111–142. doi: 10.52547/lrr.12.5.6

EF English Proficiency Index. (2022). The World's Largest Ranking of Countries and Regions by English Skills, 22nd Edn. Available online at: https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/ (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Ford, C. E., Fox, B. A., and Thompson, S. A. (2003). Social interaction and grammar. New Psychol. Lang. 2, 119–143.

Fujii, Y. (2012). Raising awareness of interactional practices in L2 conversations: Insights from conversation analysis. Int. J. Lang. Stud. 6, 99–126. Available online at: https://books.google.co.th/books?hl=en&lr=&id=NGICBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA99&ots=5r1M8sIgVL&sig=e9_IPmLSX2nONlNZTiA8C8ny0N4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Goh, C. C. M. (2015). Teaching Listening in the Language Classroom. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Hale, C. C., Nanni, A., and Hooper, D. (2018). Conversation analysis in language teacher education: an approach for reflection through action research. Hacettepe Univ. J. Educ. 33, 54–71. doi: 10.16986/HUJE.2018038796

Hall, J. K. (2004). Language learning as an interactional achievement. Modern Lang. J. 88, 607–612. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3588591

Hu, X. (2012). The application of schema theory in college English listening teaching. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2:282. doi: 10.4304/tpls.2.2.282-288

Kasper, G. (2017). “Teaching interactional competence: a conversation-analytic perspective,” in The Oxford Handbook of Language and Social Psychology, ed. T. Holtgraves (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 450–463.

Kasper, G., and Wagner, J. (2014). Conversation analysis in applied linguistics. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 34, 171–212. doi: 10.1017/S0267190514000014

Kassaye, L. (2021). The role of conversation analysis-informed instruction to enhance EFL learners' conversational skills: repair strategies in focus–Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. PASAA J. Lang. Teach. Learn. Thailand 62, 92–118. doi: 10.58837/CHULA.PASAA.62.1.4

Koshik, I., Jacoby, S., Olsher, D., and Schegloff, E. A. (2002). Conversation analysis and applied linguistics. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 22, 3–31. doi: 10.1017/S0267190502000016

Lee, Y.-A. (2023). Language moments in second language interaction: Relevance of understanding to learning. English Teach. 78, 145–168. doi: 10.15858/engtea.78.1.202303.145

Li, L., and Norton, B. (2019). Silence and engagement in the Chinese EFL classroom. J. Pragmat. 146, 98–109.

Lightbown, P. M., and Spada, N. (2021). How Languages Are Learned, 5th Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lin, A. M. Y., and Lo, Y. Y. (2016). Conversation Analysis and Second Language Pedagogy: A Guide for ESL/EFL Teachers. New York, NY: Routledge.

Matsui, E. (2014). Having their opinion: using CA (conversation analysis) to explore student-teacher interaction. Bull. St. Margarets 46, 19–31. Available online at: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/stmlib/46/0/46_KJ00009654879/_article

Naksevee, N., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2014). Non-scripted role-play: a better practice for Thai EFL college students' speaking skills. TFLTA J. 5, 80–91. Available online at: https://www.twlta.org/uploads/1/0/6/9/10696220/tfltajournal5.pdf

Nation, I. S. P. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203891704

Piscitelli, A. (2020). Effective classroom techniques for engaging students in role-playing. Teach. Innov. Projects 9, 1–8. doi: 10.5206/tips.v9i1.10320

Pourhaji, M., and Alavi, S. M. (2015). Identification and distribution of interactional contexts in EFL classes: the effect of two contextual factors. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 7, 93–123. Available online at: https://elt.tabrizu.ac.ir/article_17252.html

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., and Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50, 696–735. doi: 10.1353/lan.1974.0010

Sanitchai, P., and Thomas, D. (2018). The relationship of active learning and academic achievement among provincial university students in Thailand. APHEIT Int. J. 7, 47–61. Available online at: https://apheit.bu.ac.th/jounal/Inter-vol7-1/04_%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%88%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%A2_pimolporn,darrin.pdf (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Schegloff, E. A. (1995). Discourse as an interactional achievement III: the omnirelevance of action. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 28, 185–211. doi: 10.1207/s15327973rlsi2803_2

Schegloff, E. A. (2013). Harvey Sacks Lectures 1964–1965. Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The Interactional Architecture of Language Classroom: A Conversation Analysis Perspective. Oxford: Blackwell.

Seedhouse, P. (2005). Conversation analysis and language learning. Lang. Teach. 38, 165–187. doi: 10.1017/S0261444805003010

Sert, O. (2015). Social Interaction and L2 Classroom Discourse. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780748692651

Sert, O., and Seedhouse, P. (2011). Introduction: conversation analysis in applied linguistics. Novitas-R. 5, 1–14. Available online at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/novroy/issue/10815/130376

Siegel, A., and Seedhouse, P. (2019). Conversation analysis and classroom interaction. Ency. Appl. Linguist. 259–264. Available online at: https://rb.gy/04f2u8

Sinwongsuwat, K., and Nicoletti, K. (2020). Implementing CA-T model lessons in schools: a preliminary study in southern border provinces of Thailand. Engl. Lang. Teach. 13, 15–29. doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n11p15

Sinwongsuwat, K., Nicoletti, K., and Teng, B. (2018). CA-informed conversation teaching: helping Thai students unpack English conversation to become conversationally competent. J. Asia TEFL 15, 700–720. doi: 10.18823/asiatefl.2018.15.3.9.700

Sitthikoson, A., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2017). Effectiveness of explicit CA-informed telephone conversation instruction in enhancing conversation abilities of Thai learners of English. Veridian E-J. Silpakorn Univ. 10, 63–85.

Sunil, P. (2022). Asian Countries With the Highest English Proficiency: Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia and More. Available online at: https://www.humanresourcesonline.net/asian-countries-with-the-highest-english-proficiency-singapore-the-philippines-malaysia-more-2021 (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Tantiwich, K., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2021). Thai university students' problems of language use in English conversation. LEARN J. 14, 598-626. Available online at: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/LEARN/article/view/253282

Teng, B., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2015a). Teaching and learning English in Thailand and the integration of conversation analysis (CA) into the classroom. Engl. Lang. Teach. 8, 13–23. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n3p13

Teng, B., and Sinwongsuwat, K. (2015b). Improving English conversation skill through explicit CA-informed instruction: a study of Thai university students. PASAA Paritat J. 30, 65–104. Available online at: https://www.culi.chula.ac.th/Images/asset/pasaa_paritat_journal/file-10-99-iokf5s624691.pdf

Tran, N. (2022). Enhancing Student Engagement Through Incorporating Primary Sources in ESL Classes (Unpublished Diploma Thesis). Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic.

Ulla, M. B., Bucol, J. L., and Dechatiwongse Na Ayuthaya, P. (2022). English language curriculum reform strategies: the impact of EMI on students' language proficiency. Ampersand 9, 1–8 doi: 10.1016/j.amper.2022.100101

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).. (2014). Global citizenship education: preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. UNESCO. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227729 (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Van Canh, L., and Renandya, W. A. (2017). Teachers' English proficiency and classroom language use: a conversation analysis study. RELC J. 48, 67–81. doi: 10.1177/0033688217690935

Waring, H. Z., and Hruska, B. L. (2011). Getting and keeping Nora on board: a novice elementary ESOL student teacher's practices for lesson engagement. Ling. Educ. 22, 441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2011.02.009

Wong, J., and Waring, H. Z. (2010a). Conversation Analysis and Second Language Pedagogy. London: Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9780203852347

Wong, J., and Waring, H. Z. (2010b). “Conversation analysis and teacher expertise,” in Language Teacher Research in Asia, eds. H. Waring and J. Takaki (London: Continuum), 55–71.

Keywords: CA-T Model, Conversation Analysis (CA)-informed pedagogy, conversation skills, EFL learners, English language teaching in Thailand, teaching English conversation

Citation: Sinwongsuwat K (2025) Enhancing Thai EFL learners' conversation skills through the CA-T Model: a conversation analysis-informed approach. Front. Educ. 10:1627966. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1627966

Received: 13 May 2025; Accepted: 16 July 2025;

Published: 20 August 2025.

Edited by:

Sri Suryanti, Surabaya State University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Pitambar Paudel, Tribhuvan University, NepalAnik Nunuk Wulyani, State University of Malang, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Sinwongsuwat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kemtong Sinwongsuwat, a3NpbndvbmdAZ21haWwuY29t

Kemtong Sinwongsuwat

Kemtong Sinwongsuwat