- Department of Humanities Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

This article considers how the use of multiple languages and the incorporation of arts-based methods in the Foundation Phase (Grades 1 to 3) classroom led to the creation of a third space, which is characterised by openness and creativity. A third space is transformative in nature, as it facilitates the process of cultural exchange among traditions that creates new identities, values, and practices. By facilitating ‘new’ learning, parents, teachers, and learners share their cultural artefacts, co-construct knowledge, and connect home and school literacies. The study took on an interventionist approach which incorporated the theories of third space, arts-based enquiry and multimodality to create a space that incorporated innovative pedagogies. The findings indicate that by allowing learners to create meaning through multilingualism, multimodalities and arts-based methods improved their language skills. Participating learners’ understanding of reading passages improved when they were allowed to express their cognition through a combination of drawings, multilingual discussions and writing, as opposed to answering in writing only. In the South African context, many people are able to speak more than two languages. Therefore, both multilingualism and arts-based methods can be used to create innovative pedagogical practices in the classroom to enhance literacy development.

Introduction

South Africa is known for the presence of diverse ethnic groupings, religious convictions, and cultural backgrounds. Being so diverse, the country was nicknamed the ‘rainbow nation’. The diversity of its people is reflected in its 12 official languages (Ngubane and Makua, 2021). This diverse landscape is also present in classrooms. The diversity of languages in South Africa was created when people migrated from other regions of Africa to southern Africa. Therefore, it is necessary to consider multilingualism in South Africa for the purposes of economic and community development (US AID, 2020). Many people in South Africa speak three languages and do not draw any distinction between the first or additional language (Fawole and Pillay, 2019). This makes the development and implementation of language policies complex, especially in education, where non-indigenous languages such as English and Afrikaans still play an important role (Pretorius and Klapwijk, 2016). The PIRLS 2021 results showed that learners’ literacy performance in South Africa is low. Many learners are below the required grade level for reading and writing and they have not developed adequate comprehension skills by the end of Grade 3 (Roux et al., 2023). As they reach the end of Grade 4, their reading fluency is still below the grade level, and they are not able to engage with the content in the curriculum (Roux et al., 2023). As many learners do not grasp the basic levels of reading, they fail to make the transition in reading to learn from Grade 4; this challenge is attributed to the language imposition that multilingual learners face (Makalela, 2015; Mgijima and Makalela, 2016).

Allowing the use of learners’ home languages in the classroom creates a classroom environment that develops a sense of security which enables them to engage more cognitively with learning content, as they are able to draw links between the home language and language of instruction (Neokleous and Karpava, 2023). This also affects how the learning of additional languages is understood and interpreted, especially in an environment where multiple languages are used (Wildsmith-Cromarty and Balfour, 2019). Thus, there is a need for the implementation of innovative pedagogical practices that incorporate multiple languages and allow learners to use their preferred mode for meaning making. Innovative pedagogical practices adapt to the needs of diverse learners in the classroom and emphasise an interactive and engaging learning environment (Okolie et al., 2022). The use of multiple languages in the classroom and the incorporation of arts-based methods are viewed as innovative pedagogical practices. Another practice that has a positive impact on language learning in multilingual environments is translanguaging, which is the interchangeable use of multiple languages in the classroom for meaning making (Nurjanah, 2024).

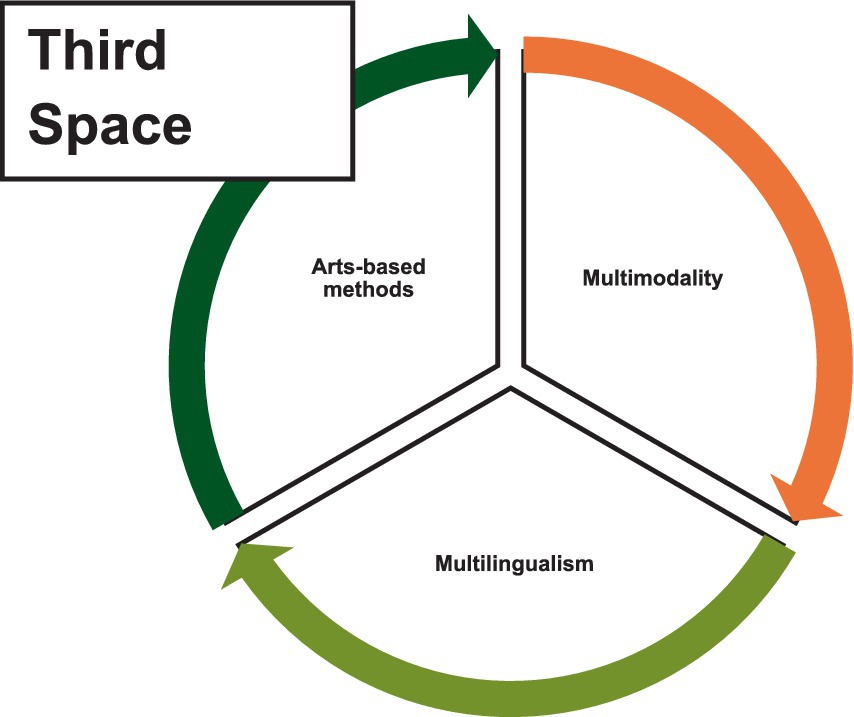

In this article, I consider how the use of translanguaging, arts-based methods and multimodality created a ‘third space’ in the classroom, which was characterised by openness and creativity. Therefore, the study incorporated third space, multimodality and arts-based methods to develop an innovative pedagogy to increase learner participation in learning content.

The study proposes the following research question:

1. How are learners able to show understanding of a comprehension passage through their drawings?

Third spaces

There are various ‘spaces’ that together make up educational systems where teaching and learning take place. Dutton and Rushton (2021) conceptualise three spaces.

The first is the space of everyday routine and practice by learners and teachers in the school. These include class organisation, seating plans, subject content covered in the curriculum, assessment tasks as well as the relationships between teachers and their learners, and between teachers and teachers.

The second space is the representation of the ‘ideal’. These spaces emerge from historical educational artefacts, educational policies and curriculum documents, teaching accreditation protocols, and long-held societal views about the nature of education and professional standards. These inform first-space practices with the intention of aligning the everyday first-space practices with the ideal practices conceived by the dominant voices in education.

The third space creates new imaginings and possibilities (Ferrari et al., 2021). Multilingual practices such as translanguaging are seen as a third space because they challenge prevailing school practices. In some schools, multilingual practices are viewed as a third-space practice that is characterised by openness and creativity. A third space is transformative in nature, in that the process of cultural translation between different traditions takes place and different identities, values, and practices are combined to create new identities, values, and practices (Veliz and Veliz-Campos, 2025). Another aspect of this third space, as proposed by Engelbrecht and Genis (2019), is a space for ‘new’ learning to occur. In this space, parents, teachers, and learners share their cultural artefacts, learn from one another, and co-construct knowledge. This third space connects home and school literacies (Ferrari et al., 2021). Allowing learners to create meaning through multilingualism, multimodalities and arts-based methods can improve learners’ understanding of reading passages.

Translanguaging as a third space practice can improve reading skills, where learners are able to summarise main events in a story, draw conclusions from a story and also show appreciation for a story as a deeper understanding of content is developed (Moses and Torrejon Capurro, 2024). Translanguaging as a multilingual practice is seen as a transformative space, as the process of cultural translation between different traditions takes place and different identities, values, and practices are combined to create new identities, values, and practices (Dutton and Rushton, 2022). Translanguaging as practice also emphasises how multilingual users use language for meaning making rather than as something to be assessed formally (Donley, 2022). In this space, parents, teachers, and learners share their cultural artefacts, learn from one another, and co-construct knowledge. It connects home and school literacies in a transformative space where language users display the best of their creativity and criticality (Veliz and Veliz-Campos, 2025). Third spaces are also viewed as the reimagining of everyday realities, where new forms of knowledge acquisition are developed (Wedin, 2021). Here, teachers can re-make undervalued practices and beliefs, which in this study is the promotion of multilingualism, multimodality and arts-based methods (Ferrari et al., 2021). This study implemented translanguaging and arts-based practices to create a ‘third space’ of innovative pedagogies to improve learners’ understanding of a comprehension passage. Knowledge can be generated in the creation of spaces, or more specifically translanguaging spaces, whenever learners share their ‘socio-cultural, emotive histories and communicative repertoires’ (Wei and Lin, 2019).

Arts-based enquiry

Arts-based enquiry is defined as the systematic use of the artistic process or artistic expression to understanding a participant’s views or experiences in a particular study (McNiff, 2007). This type of research inquiry analyses not only the verbal or written text but also the drawings of participants to gain an understanding of a phenomenon (O'Neil et al., 2022). When learners actively draw their understanding, beneficial cognitive processes activate prior knowledge, increased attention, and better subsequent recall as new information is integrated into long-term memory (Ainsworth and Scheiter, 2021). Research consistently shows that drawing as a means of investigating what children know challenges the dominant view that verbal and written modes are the primary modes of representation (Peterson and Friedrich, 2023). Using the arts as part of inquiry is empowering for participants as it allows them to construct their own individual stories, where new forms of knowledge are also produced (Pentassuglia, 2017). During this research approach, participants co-create knowledge with researchers and are also active participants (O'Neil et al., 2022). The different art modalities such as text, audio, visual, and performance unleash participant creativity and provide opportunities for reflections that may not have been otherwise possible (Pentassuglia, 2017). In the current study, the researcher allowed learners to reflect on their understanding of a comprehension passage through their drawings. A multilingual and multimodal space was created for the learners to use their home language, alongside art for meaning making.

Few scholars have investigated how children’s drawings represent their prior knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, such as reading and acquisition of an additional language (Bartoszeck and Tunnicliffe, 2017; Bland, 2012; Kendrick and McKay, 2002; Peterson and Friedrich, 2023). What is consistently shown in research is that learners’ drawings display what they know (prior learning) or learn (new knowledge) about a particular topic (Peterson and Friedrich, 2023). Drawings also advance knowledge of the role that visual memory (the ability to recall what the eye has seen) plays in human understanding of the world. Learners’ drawings reveal how they access their personal experiences when learning to read and write (Bartoszeck and Tunnicliffe, 2017). Standardised forms of assessments usually involve reading textbooks and answering questions, filling in worksheets, report writing, or oral responses. Unlike these standardised methods, drawings indicate how children develop cognitive concepts naturally, which is a view of literacy that is not recognised by standardised methods of assessment (Bland, 2012). This study’s definition of literacy goes beyond school-based literacies by including home literacies and considering various forms of representation, including visual images (drawings).

The researcher chose an arts-based method as it comes naturally for young children to draw, they do so willingly, and it is the responsibility of adults to create opportunities for young children to express their views or understanding through their drawings (Aluri et al., 2023). This often means that research methods can be adapted to the learner’s interest level, their level of understanding and their preferred way of communication. Drawings also provide insight for teachers and parents into the world of children and how they make sense of the complex world of learning both inside and outside school (Dutton and Rushton, 2021). Creative arts-based methods can easily be adapted to a level of understanding for learners (Blaisdell et al., 2019). Arts-based methods include drawing, painting, collage design, experimental writing forms, poems, dance, drama, musical composition, sculpture, photography, and filmmaking (Blaisdell et al., 2019). However, according to Cahnmann-Taylor (2013), there are risks involved in arts-based research, as it is often viewed as a non-scientific approach, which is based on subjective interpretation. There is also little to no training on how researchers can implement arts-based inquiry. The current study endeavours to indicate how arts-based inquiry can be objectively used in research. It focuses on drawings; learners were provided with LTSMs (learning and teaching support materials) to produce their own drawings.

Multimodality

Multimodality holds that meaning is not only conveyed through what we say, but also through a variety of communicational and representational resources (Jewitt, 2009). From a multimodal perspective, sound, movement, sight, and other means of communication through the five senses (touch, hearing, taste, smell, and sight) are referred to as modes (Eisenmann and Meyer, 2018). In multimodality, space, actions, pictures, sounds, objects, tactile movement, and facial expressions are held as key semiotic resources (Cloonan, 2008). It is seen as implementing new and multiple communicative practices for literacy learning (Chan et al., 2017; Magnusson and Godhe, 2019; Newfield, 2024).

One of the most frequently overlooked modes of semiotic resources is space. In multimodality, space is a key mode of semiotic resources, similar to actions, pictures, sounds, objects, tactile movement, and facial expressions (Cloonan, 2008). Those involved in decision-making, policies, and the implementation of curricula have failed to include different modes of communication as they are steeped in a monomodal perspective of learning. Multimodality presents a way of implementing new and multiple communicative practices for literacy learning (Chan et al., 2017; Magnusson and Godhe, 2019; Newfield, 2024). Multiple modes (including but not limited to pictures, hearing, signalling, dance, and text) are processed during communication (Chan et al., 2017; Figure 1).

Methodology

Participants

This article is based on a larger interventionist convergent mixed-methods study titled: Designing a translanguaging space within a remedial reading programme at Quintile 1 primary schools’ in which Grade 3 learners participated.1 It was conducted at two Quintile 1 primary schools in Eersterust, which is a Coloured2 township situated west of Mamelodi in the Tshwane South District, Gauteng, South Africa. Parents from the neighbouring townships of Mamelodi and Nellmapius send their children to schools in Eersterust as they believe that they will learn English better here. The quintile indicates that the schools are located in an area with marked socio-economic challenges, and, subsequently, receive more financial support from the government (Aung, 2025). The schools are dual medium with both English-and Afrikaans-speaking learners. Each grade (Grade 1 to 7) consisted of three English Home Language classes and one Afrikaans Home Language class. Therefore, Grade 3 teachers from both schools taught two groups of learners; the learners from Eersterust were accommodated in English First Additional Language (EFAL) classes, and those from Mamelodi and Nellmapius were allocated to English Home Language classes. The participants were between the ages of 8–10 years old. Of the 63 participating learners, 46% were male and 54% were female. They represented two ethnic backgrounds, 60% were Coloured learners and 40% were Black African learners.

Interventions

A translanguaging and multimodal intervention took place during school hours. Sixty-four learners participated, with 32 learners selected from each of the two participating schools. This paper focuses on the intervention session where a multilingual space was created through arts-based research. The researcher wanted to determine if learners were able to reveal their understanding of a classroom discussion on a comprehension passage through their drawings.

For the intervention, EGRA reading comprehensions were administered during four sessions for each participating class. The sessions took place during school hours in class. The experimental or ‘treatment’ sessions followed a translanguaging and multimodal approach. This included oral responses, drawings, gestures, and writing activities that formed the components of the EGRA comprehension passages. Data collection methods for this paper consist of drawings and written products produced by Grade 3 learners. The researcher and learners participated in shared reading of the comprehension passage, and questions were asked during and after reading, allowing learners to make predictions of the texts’ meanings. Learners then visualised the content read though their drawings. The intervention were also planned in alignment with the South African Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS) (2010):

Learning outcomes:

• collect, analyse, organise and critically evaluate information

• communicate effectively using visual, symbolic and/or language skills in various modes

• work effectively as individuals and with others as members of a team

Alignment with CAPS:

• Listening, speaking, reading and writing

• Shared reading

• Language use

Findings

Creating a translanguaging reading space through drawing

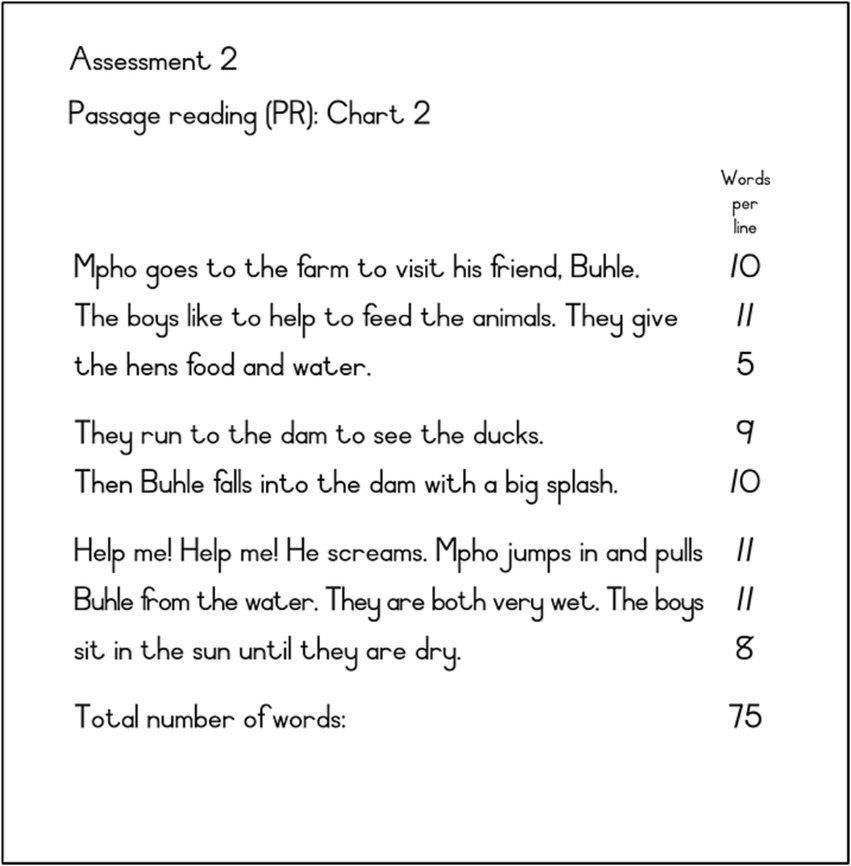

The teacher and participating learners read the passage ‘Mpho Goes to the Farm’ aloud (see Figure 2). It illustrates translanguaging through drawing. Learners had to draw their understanding of the comprehension passage. The findings indicate that even though the learner’s ability to write was below Grade 3 level, they could still mirror their understanding through their drawings.

After the passage was read together, a classroom discussion took place during which the learners had to discuss what the key points of the story were. Here, the teacher assessed their comprehension skills of sequencing and summarising. The learners were allowed to answer in their home language and make use of gestures to construct meaning. Because knowledge is often transferred from the home language to the LoLT, the teacher allowed the learners to express their knowledge and ideas in their home language, in this case, Afrikaans. This, in turn, allowed the learners to create links between the two languages. Since the learners’ proficiency in writing and speaking English was low, according to pre-test results, the classroom discussion allowed them to respond to what they had just read. The teacher asked the learners what a farm was, if any of them had recently visited a farm, and what they did during their visit. The teacher also asked questions related to the comprehension passage, such as why Buhle fell into the dam. This was to assess the learners’ understanding of what was read. After the passage was read, a classroom discussion took place. The majority of learners could answer questions about the passage and understood what it was about. Most had visited a farm before and were familiar with the different types of farm animals.

Activity 1 was a translanguaging and multimodal activity, which included the learners’ drawings (pictures) of what they had understood about the reading passage—a farm visit. The learners were told they could also draw their own experiences about a visit to a farm, and they were allowed to write a short paragraph if they wanted to. This was done to assess the learners’ writing abilities in English and their ability to express meaning multimodally through drawing and writing. Most of the learners chose to draw their understanding of the comprehension passage. From the drawings (presented below), we see that the learners were able to express their understanding of the reading through their drawings. Some also drew from their own life experiences and presented that in their drawings. According to Phatudi (2015), one method to encourage mastery of a second language is to allow learners to express what they know by drawing pictures. Drawing, as a means of investigating what learners know, challenges the dominant view that verbal and written modes are the primary modes of representation. Translanguaging as a multimodal practice takes into consideration how the visual plays a significant role in the construction of knowledge and content.

The comprehension passages chosen for the study included stories that were culturally relevant to the learners. The names of the characters Jabu, Mpho, and Lebo (from the previous texts) are names that you would typically find in South Africa, in classrooms and of friends. By choosing these passages which were relevant to the learners’ context, the teacher was able to get relevant responses from them when questions were asked (Figure 3).

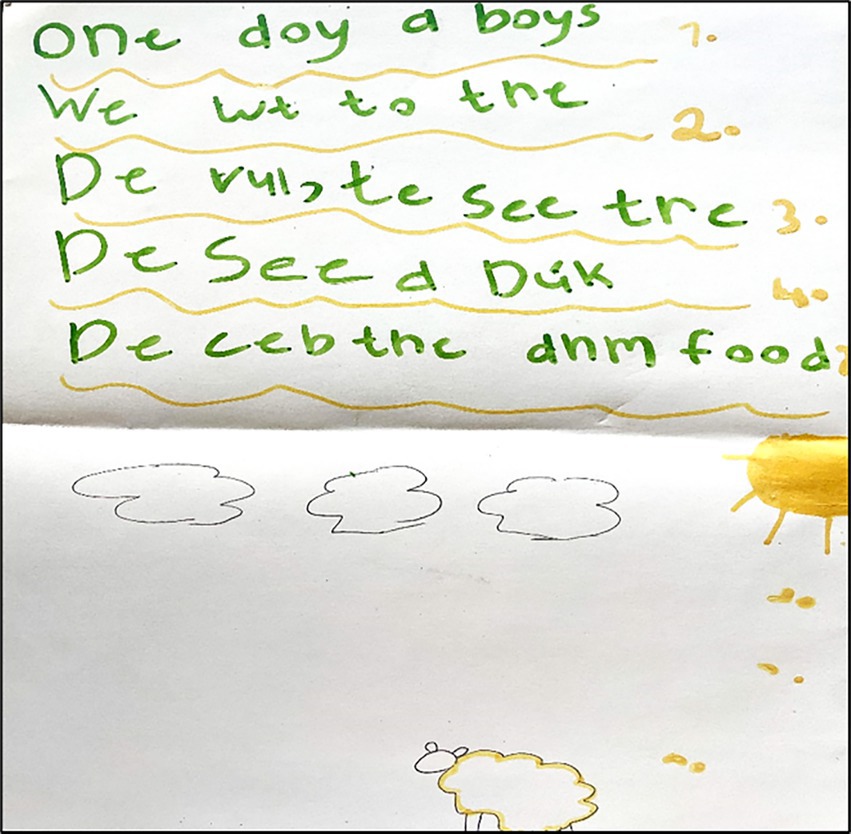

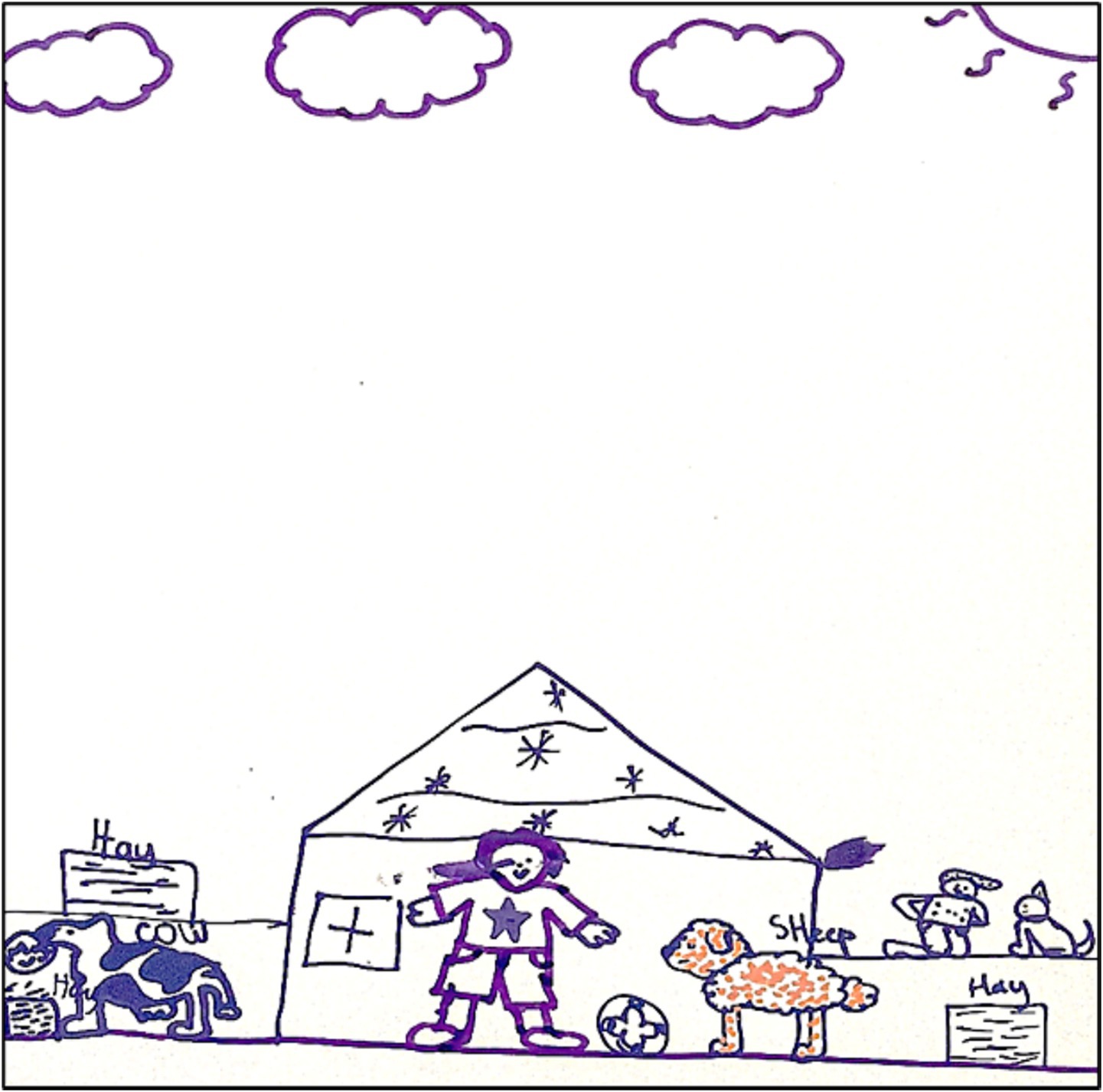

Nomsa’s drawing illustrates her attempt at writing a short paragraph and at drawing her understanding of the story. Her proficiency in English was low. She could, however, express her understanding of the comprehension passage through her drawing of a sheep on a farm. This shows the importance of the visual/artistic mode as it assists learners in expressing meaning more clearly visually than linguistically. When learners actively draw, potentially beneficial cognitive processes activate prior knowledge, increased attention, and better subsequent recall as new information is integrated into long-term memory (Ainsworth and Scheiter, 2021). Although there was no mention of a sheep in the passage, sheep count as farm animals. This expressed her understanding that the comprehension piece was about a farm and showed that she could draw from her personal lifeworld and activation of prior knowledge to make sense of the passage.

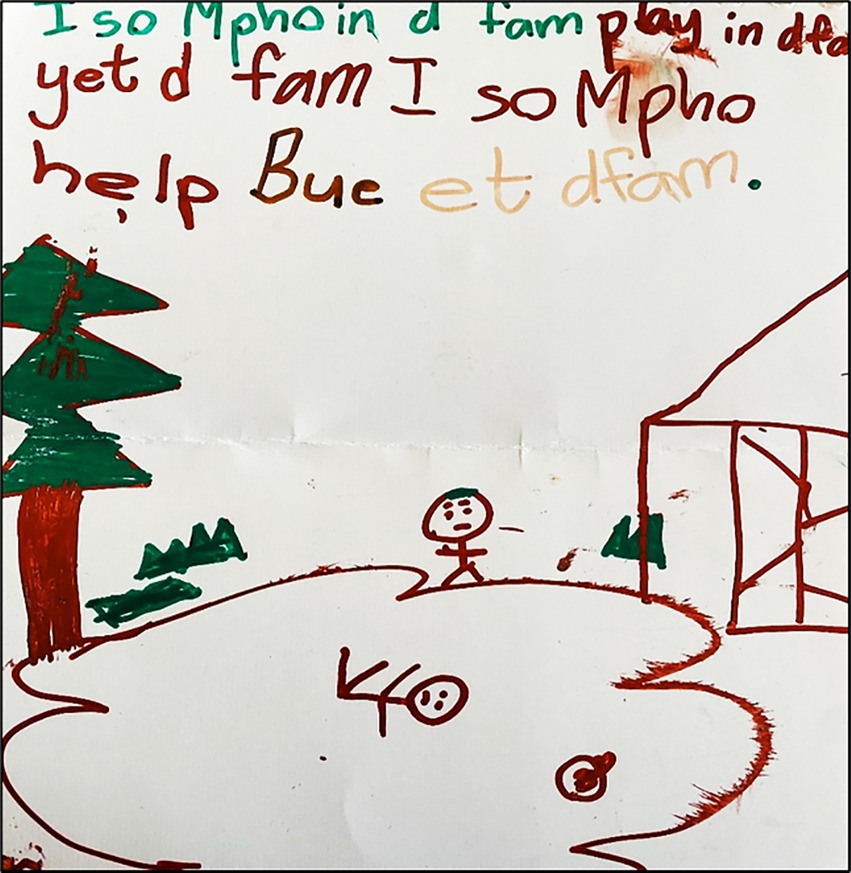

Figure 4 indicates that Thabo was also more successful in expressing meaning through his drawing than in writing. He was not able to express his understanding of the comprehension passage through his writing, but could verbally do so in class during the discussion, and visually through his drawing to conceptualise the story. It is evident that Thabo’s writing skills in English were limited. His drawing, however, includes someone drowning in what seems to be a pond. This illustrates his understanding of the plot of the passage. Through his drawing, Thabo was also able to explain the main events from the story. He was able to draw information explicitly stated in the text and explain the main ideas, which included that someone was drowning when they visited a farm.

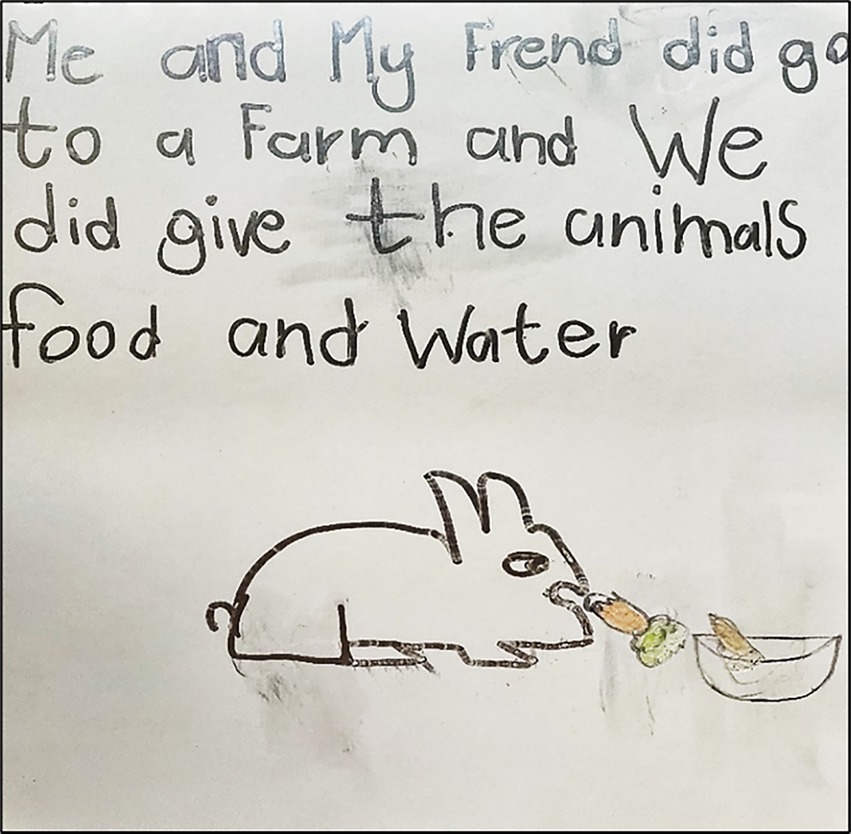

John’s writing ability in English (Figure 5) was more advanced than that of his classmates. He was able to write a short sentence related to his drawing of the visit to the farm. In his writing, he indicated that they went to the farm to feed animals. The animal that he and his friend fed was a rabbit, which he represented in a drawing of a rabbit being fed carrots. Even though a rabbit was not mentioned in the story, the learner understood that rabbits are farm animals and drew on his own life experience of visiting a farm and feeding rabbits.

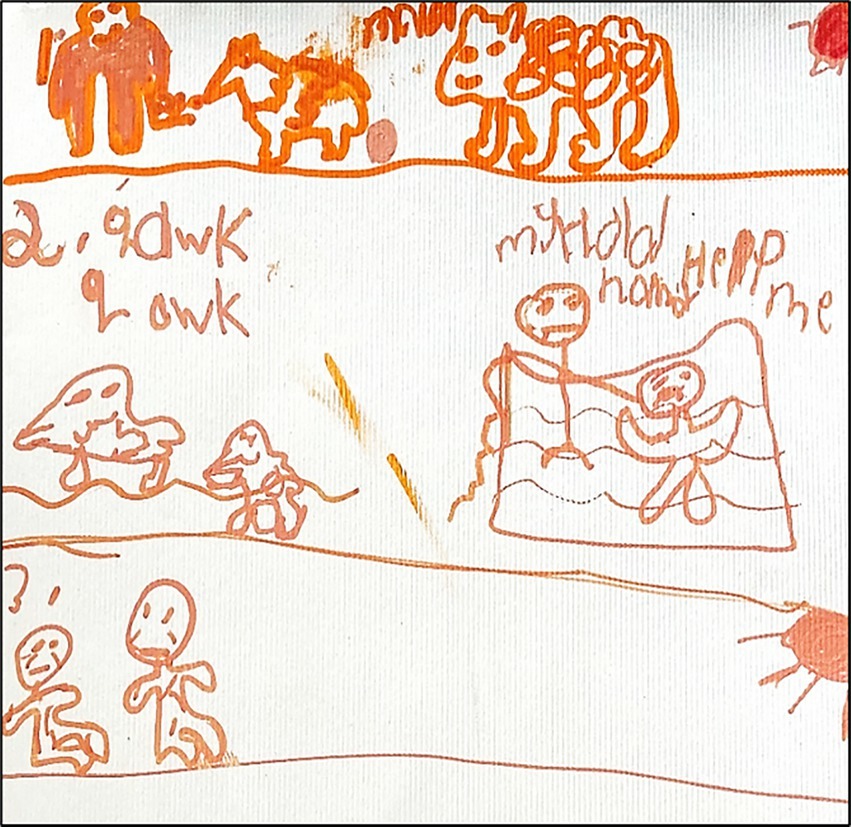

Tshepo could also not write a coherent sentence (Figure 6), which shows his lack of proficiency in writing English. He divided his drawing into three different sections. In the first section, he included animals and a boy feeding ducks. The middle section of his drawing illustrates ducks and the word ‘qawk’. Therefore, he understood that Mpho and Buhle went to the dam to see the ducks, as revealed in the duck pictures and sounds. His drawing also illustrates Buhle falling into the dam with the accompanying words ‘hold my hand’ and ‘help me’.

In Figure 6, Tshepo’s short phrases and words supported his drawings of the ducks and the sounds they make, and of Buhle almost drowning and needing assistance. The bottom section includes the image of the two boys drying themselves in the sun. The drawing reveals a creative understanding of the comprehension passage and the learner’s ability to recount how each event took place in the correct sequence. The learner was able to grasp the reading skills of summarising main points and the sequence in which they took place. Tshepo displayed the benefits of translanguaging practices during the reading of comprehension passages.

Jason drew his understanding of the comprehension passage (Figure 7). He illustrates Buhle drowning after falling into the dam; Mpho is about to dive into the water to save Buhle. Here Jason clearly expresses his understanding of the passage through his drawing, as he also includes ducks in the water and a hen laying eggs in a barn.

The images reveal his understanding of the reading passage as taking place on a farm and Buhle falling into the dam. Through his artistic expression, Jason was able to visualise what the reading passage was about. Jason’s drawing provides insight into what he knows and understands about the reading comprehension passage.

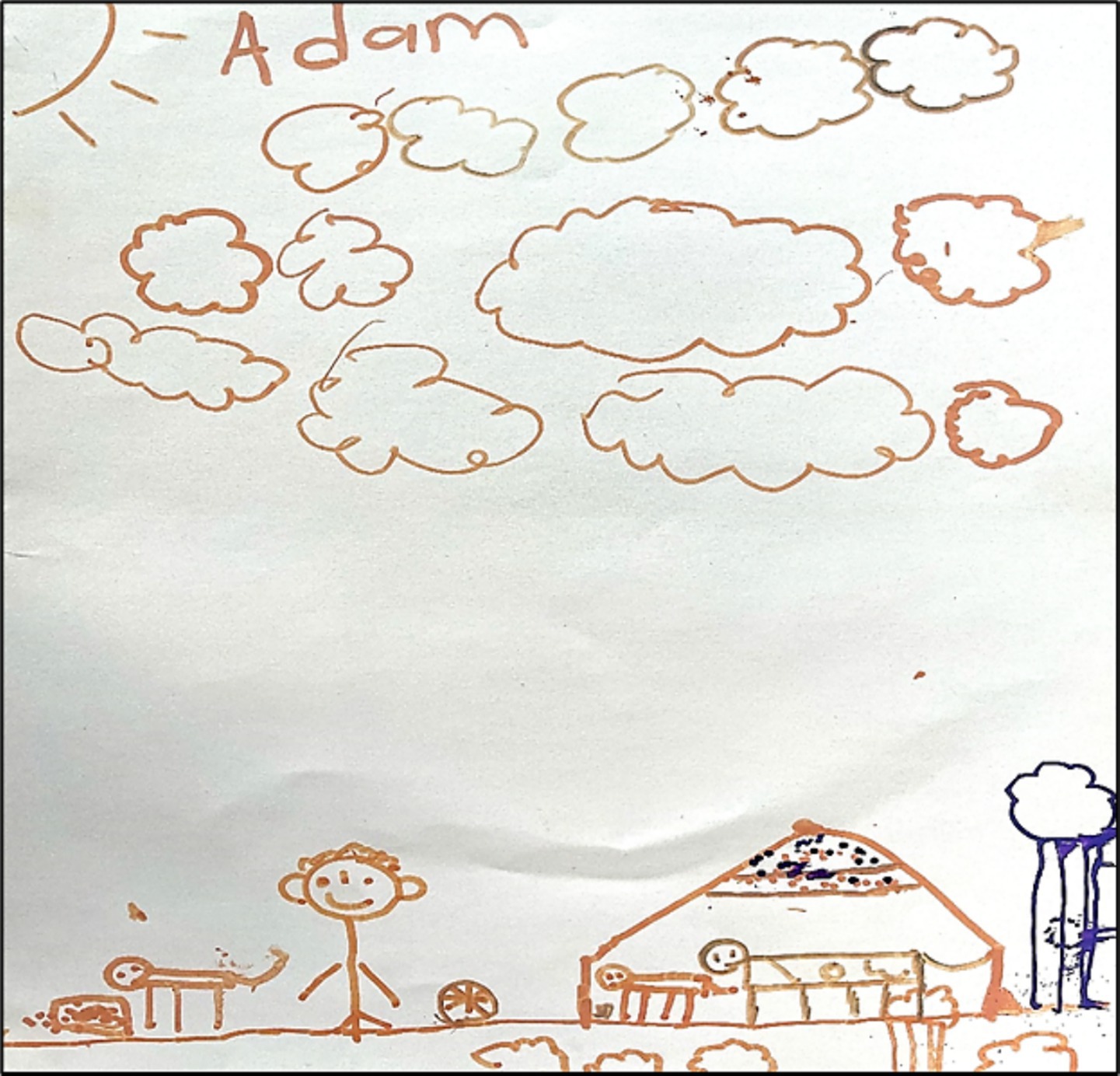

Adam and Kyle, who were sitting next to one another during this classroom activity, drew similar pictures. Both drew a barn, haystacks, animals, such as cows and sheep, and boys smiling. Both drawings also included boys playing with a ball. These two learners were able to scaffold each other’s comprehension of what took place on the farm and identified farm animals. The soccer balls indicate what they enjoyed doing on a farm. Cows, sheep, and soccer balls were not mentioned in the reading passage. These additions indicate that both learners were able to draw from real-life experiences, and from what they enjoyed doing, when they visited a farm. Translanguaging as a practice encourages learning to take place from a multimodal perspective; a learner’s understanding of a text is not only assessed through the written mode but also through drawings and gesturing.

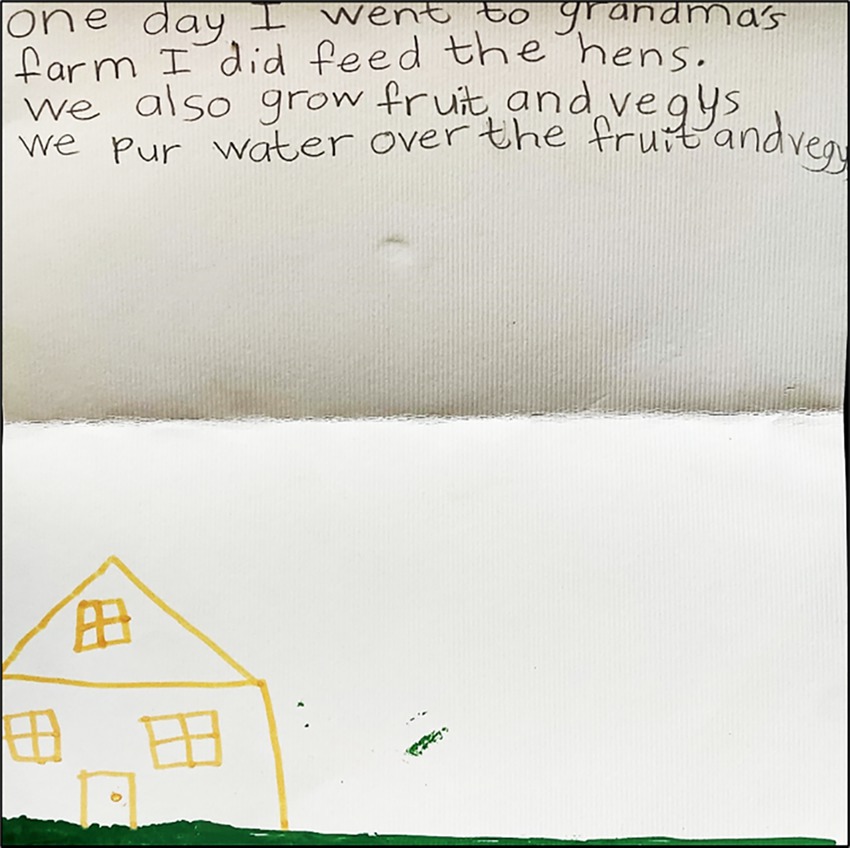

Jaden (Figure 8) decided to write a short story on his visit to his grandmother’s farm. He described how, on the farm, they fed hens and grew fruits and vegetables that they watered. Jaden merged his own experience with his written product of visiting his grandmother on her farm. In the story, there is no mention of growing and watering vegetables. Jaden drew on his own lifeworld in completing the activity in that fruits and vegetables are usually grown on farms. Jaden was able to make the link between home literacies and classroom literacies.

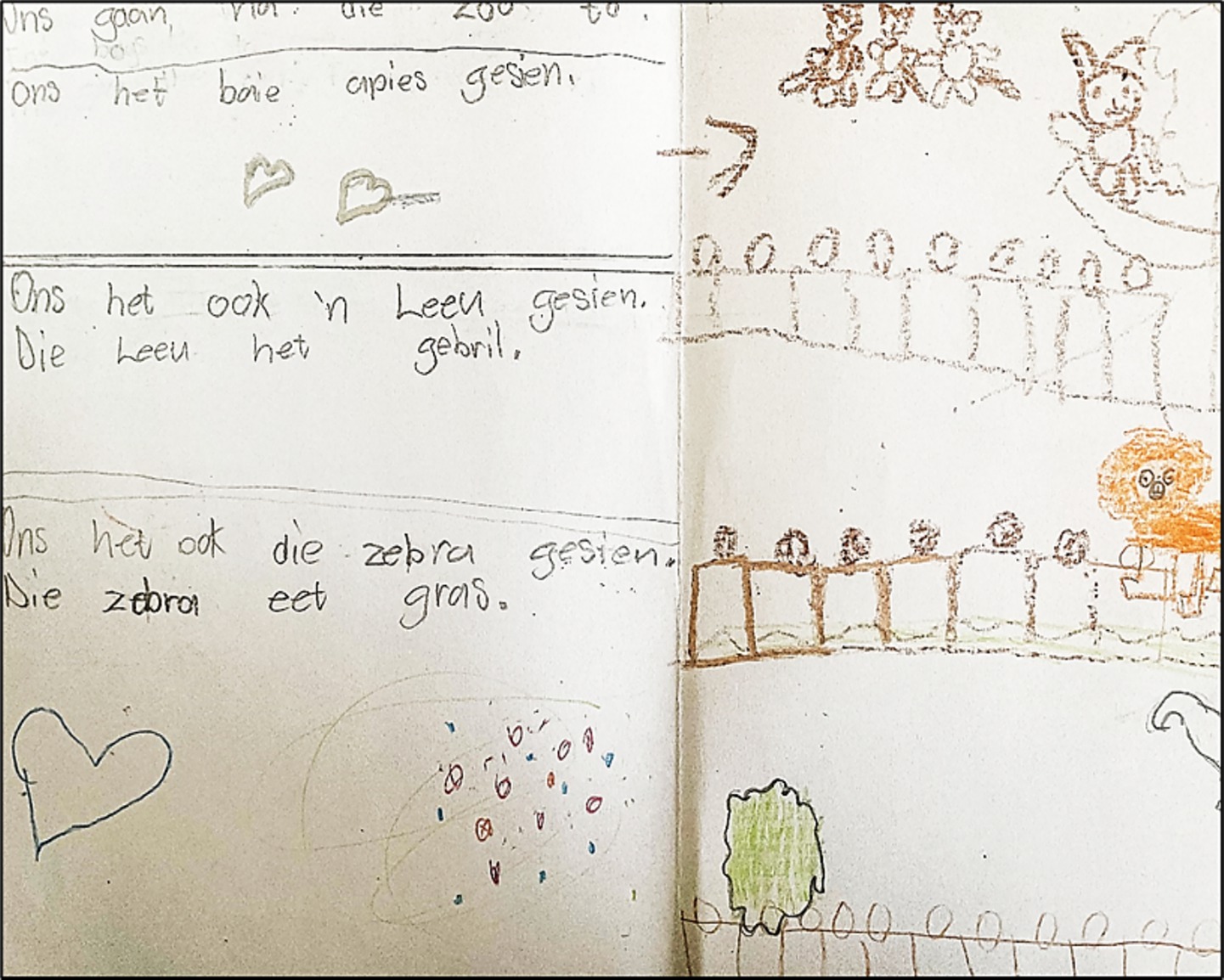

Jacob decided to write about and draw his visit to the zoo (Figure 9) even though the comprehension passage was about a visit to a farm. When the learners were asked if any of them had visited a farm and fed the animals, many of them put their hands up and related their experiences of farm visits and of visiting their grandparents on the farm. Jacob, however, told of his experience at the zoo and how he saw similar animals at school. He asked if he could rather write about and draw his visit to the zoo, and if he could write his story in Afrikaans. He wrote, ‘Ons gaan na die zoe to, ons het baie apies gesien’ (we are going to the zoo, we saw many monkeys). In the second section, he also wrote that he saw a lion and heard the lion roar (ons het a leeu gesien, die leeu het gebril). Lastly, he saw a zebra eating grass (ons het ook die zebra gesien, die zebra eet gras). Jacob drew on his personal experience of visiting the zoo and relayed it to the story of a visit to a farm. He made a link between the farm and zoo and how animals are found in both places.

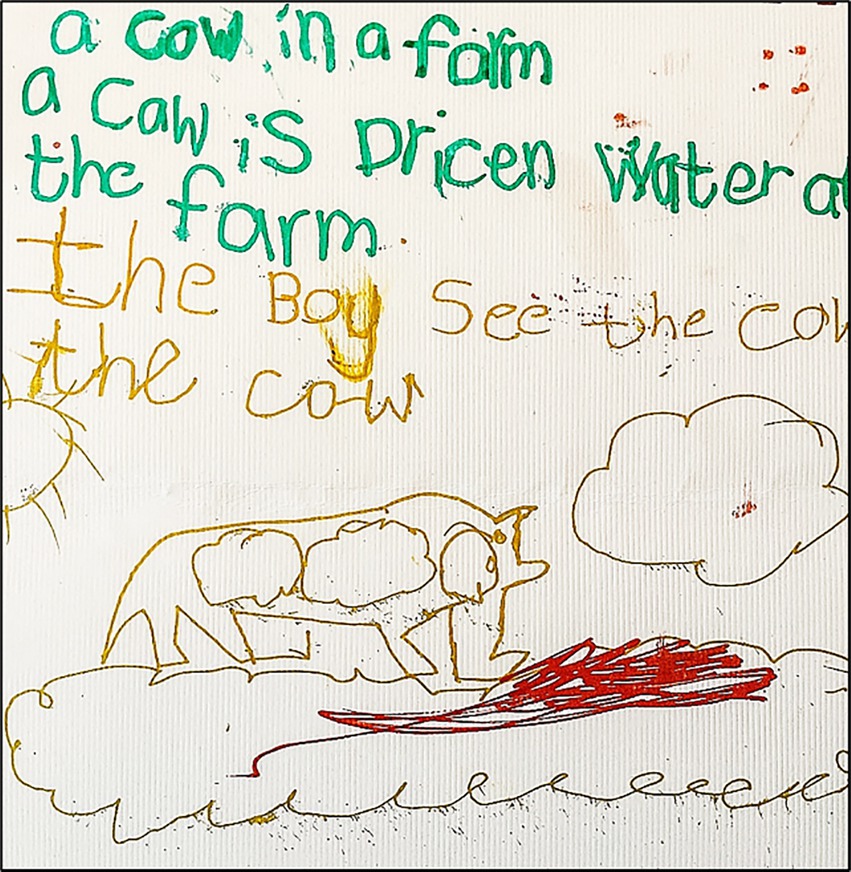

Wayne (Figure 10) chose to draw and write his understanding of the comprehension passage. He drew a cow and wrote ‘a cow in a farm’, though there was no mention of a cow in the comprehension passage. Wayne drew on his background knowledge that cows are farm animals. His writing is below the required level for Grade 3 with many spelling and grammatical errors. He writes, ‘a cow is dricen water at the farm’ and draws a cow drinking water at a pond on the farm. Even though Wayne’s writing does not make much sense, he was still able to participate in this exercise and drew his understanding of a farm animal in the form of a cow. Wayne’s design stemmed from the classroom discussion about farm visits, when learners were asked if any of them had recently visited a farm and what animals they had seen on their visit to the farm.

Observation of intervention session one (passage, Mpho goes to the farm)

From my observation of the first intervention session as a researcher and practitioner, the learners from both the participating schools were more engaged when they could draw, write and discus rather than to only write. The learners also responded to the questions in both English and Afrikaans. The learners were also excited when cardboard papers and paint pens were presented to them to create their own drawings. This emphasises the importance of classroom activities taking a multimodal approach in which drawings, writings, and discussions are all incorporated, and not just formal methods of teaching. The materials of the cardboard and paint pens also supported the lesson, and made the activity enjoyable for the learners, thereby increasing their creativity.

Discussion

The aim of this intervention session was to determine the learners’ understanding of a comprehension passage (Mpho Goes to the Farm) through the drawings they had produced. This intervention session took place after the pre-test. After each line of the passage was read, the researcher asked the learners what their understanding of the passage was; the learners were allowed to answer in Afrikaans, and some chose to do so, as they were more confident communicating in Afrikaans. What was also evident during the observation of this intervention session was the multiple modes, such as gesturing, image, and text, that the learners made use of to communicate. The learners also responded to questions through facial expressions and hand gestures. Innovative pedagogical practices entail that teachers create an interactive and engaging classroom environment.

Translanguaging as a practice emphasises how multilingual users use language for meaning making rather than as something to be only formally assessed (Donley, 2022). During discussions of comprehension passages, learners were engaged and enthusiastic; they were not passive recipients of knowledge. In the classroom, the translanguaging approach drew on all the linguistic and semiotic (gestures, images, and objects) resources of the learner to maximise understanding and achievement (Perera, 2018). The participating learners mirrored their understanding through gesturing and engagement during classroom discussions and through their drawing products more so than through their writing.

According to Peterson and Friedrich (2023), language learning should focus on the strengths of the individual learner and the style of representation they prefer, which in this study was to draw. The learners’ drawings showed how they developed concepts mentally after the comprehension passage was read; this view of literacy and understanding is not recognised by standardised methods of assessment (Bland, 2012). Phatudi (2015) states that one method to encourage the sound mastery of a second language is to allow learners to express what they know by drawing pictures, as language acquisition and meaning making can take place across different modes (Eisenmann and Meyer, 2018; Magnusson and Godhe, 2019). Young children enjoy drawing and do it willingly. Therefore, drawing was well suited for this age group, that is, the participating Grade 3 learners. Drawing and writing are also related ways of communicating, as the participating learners drew a picture and also wrote a short passage of what they understood about the reading passage. Drawing comes naturally for young children, they do it willingly, and it is the responsibility of adults to create opportunities for young children to express their views or understanding through their drawings (Aluri et al., 2023). Using arts-based methods was empowering for learners as drawings allowed them to construct their own understanding of the comprehension passage, and new forms of knowledge were also produced (Pentassuglia, 2017). What was evident from the majority of the participating learners’ writing, however, was that their ability to write was below the required level for Grade 3.

Crucially, all the drawings produced by the learners mirrored their understanding of the comprehension passages. These artefacts indicate the benefits of translanguaging in improving reading skills, where learners are able to summarise main events in a story, draw conclusions from a story and also show appreciation for a deeper understanding of content (Moses and Torrejon Capurro, 2024). They were able to articulate the main plot of a story through their drawings, for instance, where one boy was drowning, and the other had to save him (Thabo, Figure 4; Tshepo, Figure 6; and Jason, Figure 7). The learners also drew from their life experiences of visiting a farm (John, Figure 5; Adam and Kyle, Figures 11, 12; and Jaden, Figure 8) and incorporated that into their drawings. One learner drew on his experience of visiting a zoo (Jacob, Figure 9). Learners were active participants during the intervention session and co-created knowledge with the researcher (O'Neil et al., 2022). Using the arts as part of inquiry was empowering for participating learners, as drawing allowed them to construct their own individual stories, where new forms of knowledge were produced (Pentassuglia, 2017).

Through their drawings, the learners were able to reorganise information that was explicitly stated in the text, which showed literacy development. Learners were able to summarise the main points of the story in their drawings (Thabo, Tshepo and Jason). Another learner’s reorganisation skill was the ability to summarise the main events in the correct sequence in which they took place. In Figure 6, Tshepo was able to do this creatively; he divided his drawing into three sections, where each section represented the introduction, body, and conclusion of the story. Therefore, learners were able to display creativity and criticality. These examples indicate that translanguaging assisted learners in developing reading strategies such as summarising and reorganisation through their drawings (Moses and Torrejon Capurro, 2024).

Unlike standardised methods of assessments, drawings combined with translanguaging, and multimodality provide insight for teachers and parents into the world of children and how they make sense of the complex world of learning, both inside and outside school (Dutton and Rushton, 2022). Translanguaging and multimodalities can help change the view that some teachers have about emergent bilingual learners. They can embrace their learners’ cultural and linguistic diversities by allowing them to merge their personal experiences and life worlds with the act of learning. The participating learners expressed meaning through another mode, their drawings, and not just through the favoured verbal or written mode. Therefore, a translanguaging space is a multimodal space characterised by openness and creativity.

Limitations and recommendations for further research

One of the limitations to the study is the difficulty in assessing arts-based methods. More research needs to be conducted in the area of how arts-based enquiry leads to an improvement that is not just acquired subjectively, but through purposeful development that the teachers engage in with learners. A recommendation is for more mixed-methods and interventionist approach studies to be conducted through a longitudinal design to investigate improvement in learner results. Furthermore, more arts-based educational researchers should share techniques and methods used to train other researchers to understand, critique, and further develop arts-based approaches in scholarship (Cahnmann-Taylor, 2013).

Conclusion

This article focused on how arts-based methods assisted learners to display understanding of a comprehension passage. The findings from this intervention session indicate that designing a translanguaging space led to increased engagement and understanding of reading texts amongst Grade 3 learners. The learners were able to represent their understanding more clearly through their drawings than in their writing. Importantly, they displayed creativity and criticality in their drawings, with some learners demonstrating the reading strategies of summarising and organisation. The creation of translanguaging spaces allowed participating learners to activate their cultural backgrounds and personal histories during the act of learning.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://repository.up.ac.za/items/1e42d696-63f6-48f1-855f-793e0a87ae04.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria’s Ethics Committee (EDU 184/22) before the commencement of this study. The participants gave their full consent for participating in the study. Pseudonyms were used for the participants.

Author contributions

SA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This article is based on a doctoral study carried out by Shine Aung under supervision of Gerhard Genis; see Aung (2025).

2. ^Coloured refers to the cultural community in South Africa, who descend from the ancient KhoiSan people.

References

Ainsworth, S. E., and Scheiter, K. (2021). Learning by drawing visual representations: potential, purposes, and practical implications. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 30, 61–67. doi: 10.1177/0963721420979582

Aluri, J., Ker, J., Marr, B., Kagan, H., Stouffer, K., Yenawine, P., et al. (2023). The role of arts-based curricula in professional identity formation: results of a qualitative analysis of learner’s written reflections. Med. Educ. Online 28, 1–7.

Aung, S. (2025). Designing a translanguaging space within a remedial reading programme at Quintile 1 primary schools. PhD thesis.: University of Pretoria.

Bartoszeck, A. B., and Tunnicliffe, S. D. (2017). “Development of biological literacy through drawing organisms” in Drawing for science education: An international perspective. (Rotterdam: SensePublishers), 55–65.

Blaisdell, C., Arnott, L., Wall, K., and Robinson, C. (2019). Look who’s talking: using creative, playful arts-based methods in research with young children. J. Early Child. Res. 17, 14–31. doi: 10.1177/1476718X18808816

Bland, D. (2012). Analysing children’s drawings: applied imagination. International Journal of Research & Method in Education. 35, 235–242.

Cahnmann-Taylor, M. (2013). “Arts-based research: histories and new directions” in Arts-based research in education (New York: Routledge), 21–33.

Chan, C., Chia, A., and Choo, S. (2017). Understanding multiliteracies and assessing multimodal texts in the English curriculum. English Teach. 46, 1–15.

Cloonan, A. (2008). Multimodality pedagogies: a multiliteracies approach. Int. J. Learn. Ann. Rev. 15, 159–168. doi: 10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v15i09/45952

Donley, K. (2022). Translanguaging as a theory, pedagogy, and qualitative research methodology. NABE Journal of Research and Practice. 12, 105–120.

Dutton, J., and Rushton, K. (2021). Using the translanguaging space to facilitate poetic representation of language and identity. Lang. Teach. Res. 25, 105–133. doi: 10.1177/1362168820951215

Dutton, J., and Rushton, K. (2022). Drama pedagogy: subverting and remaking learning in the thirdspace. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 45, 159–181. doi: 10.1007/s44020-022-00010-6

Eisenmann, M., and Meyer, M. (2018). Introduction: multimodality and multiliteracies Special issue of. Anglistik 29, 5–23.

Engelbrecht, A., and Genis, G. (Eds.) (2019). Multiliteracies in education: South African perspectives. Van Schaik.

Fawole, A., and Pillay, P. (2019). Introducing the English language to learners in a multilingual environment: a dilemma that must be resolved. Gend. Behav. 17, 12583–12596.

Ferrari, S., Triacca, S., and Braga, G. (2021). Design for learning in the third space: opportunities and challenges. Res. Educ. Media 13, 1–10. doi: 10.2478/rem-2021-0006

Kendrick, M., and McKay, R. (2002). Uncovering Literacy Narratives through Children’s Drawings. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de l’éducation. 27, 45–60.

Magnusson, P., and Godhe, A. L. (2019). Multimodality in language education: implications for teaching. Designs Learn. 11, 127–137. doi: 10.16993/dfl.127

Makalela, L. (2015). Moving out of linguistic boxes: the effects of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classrooms. Lang. Educ. 29, 200–217. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2014.994524

McNiff, S. (2007). Empathy with the shadow: Engaging and transforming difficulties through art. Journal of humanistic psychology. 47, 392–399.

Mgijima, V. D., and Makalela, L. (2016). The effects of translanguaging on the bi-literate inferencing strategies of fourth grade learners. Perspect. Educ. 34, 86–93. doi: 10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34i3.7

Moses, L., and Torrejon Capurro, C. (2024). Literacy-based play with young emergent bilinguals: Explorations in vocabulary, translanguaging, and identity work. Tesol Quarterly. 58, 423–450.

Neokleous, G., and Karpava, S. (2023). Comparing pre-service teacher attitudes toward the use of students’ home language (s) in linguistically diverse English as an additional language classroom in Norway and Cyprus. Front. Educ. 8:1254025. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1254025

Newfield, D. (2024). Educators’ uptake of Kress’s ideas on meaning-making and literacy: a case study from South Africa. Text Talk. 44, 547–565.

Ngubane, N. I., and Makua, M. (2021). Intersection of Ubuntu pedagogy and social justice: transforming south African higher education. Transform. High. Educ. 6:113. doi: 10.4102/the.v6i0.113

Nurjanah, A. (2024). Bridging languages: Translanguaging and vocabulary development in English Language education. Hawalah: Kajian Ilmu Ekonomi Syariah 3, 82–88. doi: 10.57096/hawalah.v3i2.63

Okolie, U. C., Igwe, P. A., Mong, I. K., Nwosu, H. E., Kanu, C., and Ojemuyide, C. C. (2022). Enhancing students’ critical thinking skills through engagement with innovative pedagogical practices in global south. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 1184–1198. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1896482

O'Neil, P., Kteily-Hawa, R., and Le Ber, M. J. (2022). Social portraiture: decolonizing ways of knowing in education through arts-based participatory action research. Can. J. Action Res. 22, 32–44. doi: 10.33524/cjar.v22i3.589

Pentassuglia, M. (2017). “The art (ist) is present”: arts-based research perspective in educational research. Cogent Educ. 4:1301011. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1301011

Perera, N. (2018). “7. Gesture and Translanguaging at the Tamil Temple,” in Making Signs, Translanguaging Ethnographies: Exploring Urban, Rural and Educational Spaces. Eds. A. Sherris and E. Adami (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 112–132.

Peterson, S. S., and Friedrich, N. (2023). Viewing young children’s drawing, talking, and writing through a ‘language as context’ lens: implications for literacy assessment. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 30, 106–121.

Phatudi, N. (2015). Introducing English as first additional language in the early years. South Africa: Pearson.

Pretorius, E. J., and Klapwijk, N. M. (2016). Reading comprehension in South African schools: Are teachers getting it, and getting it right? Per Linguam. A Journal of Language Learning= Per Linguam: Tydskrif vir Taalaanleer. 32, 1–20.

Roux, K., Van Staden, S., and Tshele, M. (2023). Progress in international Reading literacy study 2021: South African main report. Department of Basic Education.

South African Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS). (2010). This is the year the curriculum was developed.

US AID. (2020). South Africa: Language of instruction country profile. Washington, DC. Available online at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00X9JQ.pdf (Accessed October 2, 2024).

Veliz, L., and Véliz-Campos, M. (2025). Multimodality as a “third space” for English as an additional language or dialect teaching: early career teachers’ use and integration of technology in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms. Educational Review. 77, 1140–1154.

Wedin, Å. (2021). Schoolscaping in the third space. Apples-Journal of Applied Language Studies. 27, 54–74.

Wei, L., and Lin, A. M. (2019). Translanguaging classroom discourse: Pushing limits, breaking boundaries. Classroom Discourse. 10, 209–215.

Keywords: multilingualism, arts-based, third space, innovative pedagogies, foundation phase classrooms

Citation: Aung S (2025) Creating multilingual spaces through arts-based methods in foundation phase classrooms. Front. Educ. 10:1628614. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1628614

Edited by:

Martin Njoroge, United States International University—Africa, KenyaReviewed by:

M. Dolores Ramirez, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainEverlyn Oluoch, United State International University, Kenya

Copyright © 2025 Aung. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shine Aung, c2hpbmUubWFAdXAuYWMuemE=

Shine Aung

Shine Aung