- 1School of Education, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2School of Education, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

Purpose: Education districts are critical to providing and sustaining quality teaching and learning. This paper examines the nature of support provided by district officials in two education districts in South Africa (SA) and the challenges encountered in improving quality teaching and learning.

Methodology: Underpinned by the interpretive paradigm and a qualitative research approach, this study employed purposive sampling to select the two districts, with further input from District Directors in identifying additional participants, including Circuit Managers and Curriculum Support officials. Semi-structured interviews served as the data generation technique, and the data were thematically analysed.

Findings: The findings show that while organisational structures are crucial for enhancing efficiency in delivering on mandates, the work of the District Offices in this study did not align with expectations. It is evident that a culture of working in silos and a failure to coordinate activities within districts persisted, thus undermining the noble intentions of policy regulations governing the work of district offices and supporting effective teaching and learning in schools. The participants viewed leadership strategies that neglected lower grades and prioritised Grade 12 as a leadership challenge. Drawing from the findings, we can conclude that the district’s implementation of adequate support for schools remains a challenge.

Unique contribution to theory, policy and practice: This research has brought to the fore a discourse and recognition in the South African context of the need to move away from a compliance-driven accountability paradigm to a support-focused model, and that such a move is a feasible and viable proposition. Therefore, we contribute to the emerging research on district leadership in South Africa by suggesting that enhanced district support could lead to a more inclusive and coherent approach within the district and across schools.

1 Introduction

Over the past two decades, international scholarship highlights the critical role of education districts in improving student achievement and fostering equitable educational outcomes (Boyce and Bowers, 2018; Honig and Rainey, 2020; Fullan, 2015). Districts are no longer viewed merely as bureaucratic intermediaries but as institutional actors capable of orchestrating large-scale instructional reform (Rorrer et al., 2008). In high-performing systems, district leadership is associated with aligning resources, building instructional capacity, and reducing disparities across schools.

In the South African context, national policy, most notably the Policy on the Organisation, Roles and Responsibilities of Education Districts (Republic of South Africa, 2013), positions the district as a key site for educational support and reform. Yet, empirical research continues to depict districts as structurally fragmented and functionally limited, operating in silos and reinforcing a culture of compliance rather than fostering sustainable instructional leadership (Bantwini and Moorosi, 2018; Twalo, 2017). In particular, districts tend to focus disproportionately on accountability measures tied to Grade 12 outcomes, often to the neglect of foundational learning in the General Education and Training (GET) phase. GET Phase consists of Grade R to Grade 9 learners (their age ranges from 4 or 5-years old to 14 years old). The Further Education and Training (FET) Phase comprises learners in Grades 10 to 12 (14- to 18-year-olds), and this is an exit phase (South African Schools Act, as Amended, 1996). This narrow focus exacerbates existing inequalities, particularly in under-resourced schools serving historically marginalised communities.

While international research has focused on district-led improvement efforts in developed countries (e.g., Cobb et al., 2020; Childress et al., 2020), research in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) is scarce. South Africa, despite its robust policy infrastructure, lacks comprehensive studies that capture the complex interplay between district strategies and school-level instructional needs, particularly from the dual perspectives of district officials and school principals. This study addresses that gap by exploring how two education districts in South Africa conceptualise and enact leadership strategies to support teaching and learning, and how such strategies are constrained or enabled by systemic factors.

This study adopts Rorrer et al.’s (2008) framework, which positions districts as institutional actors responsible for instructional guidance, policy coherence, organisational reorientation, and equity. The study interrogates how district offices function as middle-tier actors in promoting both excellence and equity in education. This theoretical lens is especially valuable in the South African context, where persistent inequality continues to undermine efforts to improve learner outcomes in rural and disadvantaged settings (Spaull and Taylor, 2022; Fleisch, 2018). The central research question that frames this study is: What are the district leadership strategies and challenges in supporting teaching and learning in selected districts in South Africa?

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature by theorising district leadership in a low- and middle-income context as a systemic and equity-driven practice. While global frameworks have emerged to articulate the transformative potential of district leadership (Rorrer et al., 2008; Honig and Rainey, 2020), such models have not been adequately applied, tested, or extended within the complex realities of developing education systems. Moreover, few studies in South Africa have examined district leadership from the perspectives of district officials and principals, thereby limiting the conceptual understanding of leadership as a shared and contested space of influence.

This study refers to the district as situated between schools and the provincial and national education departments (Asim et al., 2023; Childress et al., 2020). District leaders are district officials, including those with instructional leadership responsibilities, who directly interface with school staff to improve teaching and learning (Bantwini, 2019; Fullan, 2015; McLennan et al., 2018; Naicker and Mestry, 2015). For this study, these include the district director, circuit managers and curriculum support specialists.

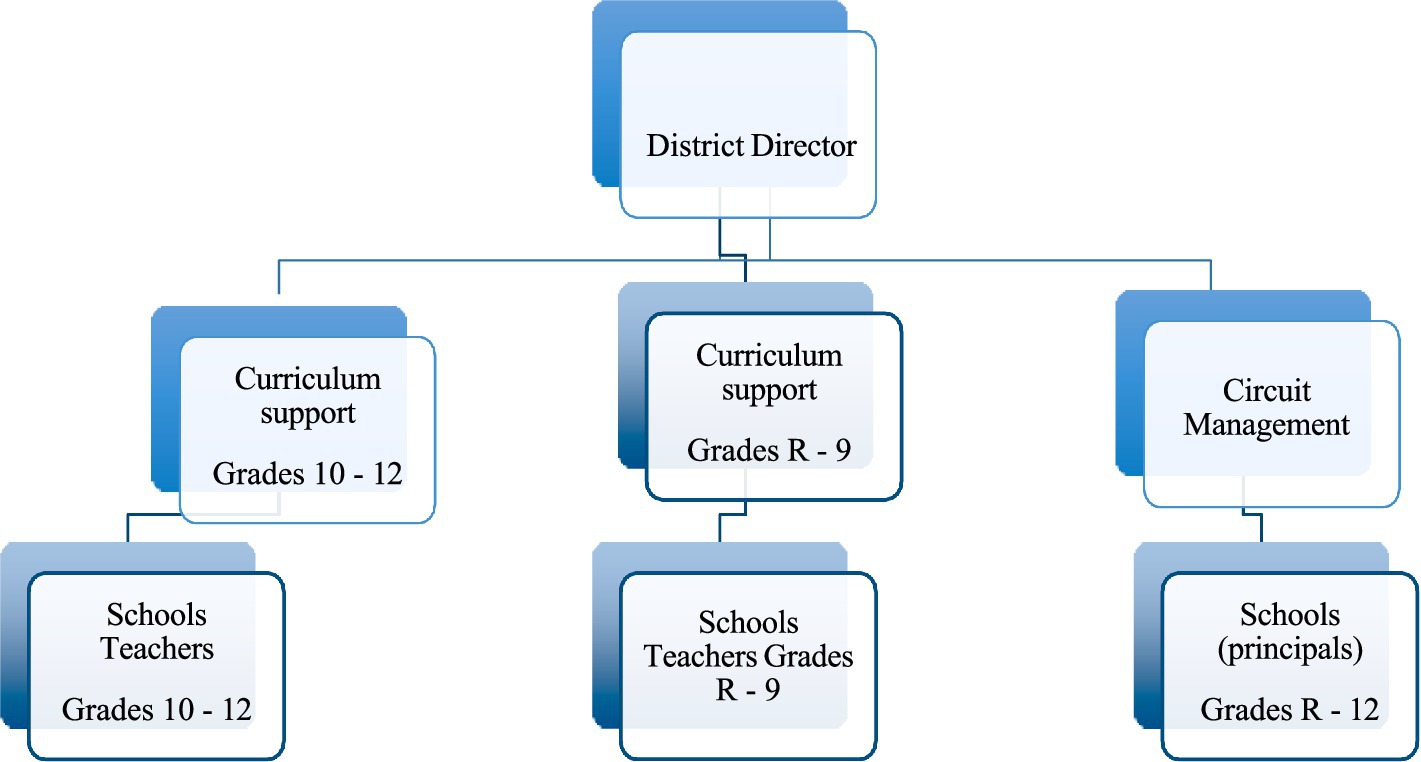

In SA, the term ‘district’ is more commonly used, including circuits as substructures of the district. Figure 1 depicts the structure of the district in relation to DOs that directly support teaching and learning in schools (Republic of South Africa, 2013). The Curriculum Support sub-directorate (section) primarily supports teachers and departmental heads on curriculum-related matters. In contrast, circuit management includes circuit managers, who mainly support principals in curriculum and instructional leadership, among other school principal functions. The district director has an oversight function and is accountable for all schools in the district (Republic of South Africa, 2013). Circuit managers oversee district sub-structure circuits and serve as principal supervisors of the schools within their circuits. Curriculum Support division comprises two sections, namely, General Education and Training [GET] (Grades R–9) and Further Education and Training [FET] (Grades 10–12). District officials, including subject advisors, play a vital role in supporting and developing school principals and staff. They oversee school supervision and support in areas like curriculum management, helping schools navigate complex issues and make informed decisions (Myende et al., 2022; Republic of South Africa, 2013). They facilitate networking and collaboration among principals and teachers, creating opportunities for them to share experiences, exchange ideas, and learn from one another (Republic of South Africa, 2013).

According to Chapter A of the Personnel Administration Measures (PAM), curriculum support and delivery in South African education districts is driven by a coordinated team of officials with distinct yet interrelated roles (Department of Basic Education, 2024). The District Director leads overall education operations by implementing national and provincial policies, supervising school leadership, managing resources, and addressing systemic challenges to improve learning outcomes. At the circuit level, the Circuit Managers supervise principals, support curriculum implementation, facilitate school improvement planning, and ensure alignment with departmental goals (Department of Basic Education, 2024; Republic of South Africa, 2013). The Chief Education Specialist (CES) provides strategic direction for curriculum delivery by managing curriculum support sub-directorate/section, and leading innovation and professional development initiatives. Supporting this role, the Deputy Chief Education Specialist (DCES) coordinates subject support teams, conducts school visits, promotes ICT integration, and organises educator training to address curriculum delivery needs. Finally, the Senior Education Specialist (SES), commonly referred to as a Subject Advisor, works directly with teachers to guide curriculum implementation, moderate assessments, monitor curriculum coverage, and facilitate subject-specific training and enrichment activities. Collectively, these roles ensure the effective delivery of curriculum and continuous improvement in teaching and learning across schools (Department of Basic Education, 2024; Republic of South Africa, 2013).

While district officials are entrusted with the responsibilities of supporting schools and principals, Myende et al. (2022) emphasise the view that they face challenges posed by various deprivations. These debates suggest that the role of district leaders in SA is fairly contentious. Therefore, it is crucial that we elicit insights about the nature of support that DOs, as district leaders, provide to schools in order to improve their academic performance. Similarly, it is important to understand school principals’ perceptions as recipients of support from DOs. This paper’s research question is, “What are the district leadership strategies and challenges in supporting teaching and learning in schools in the selected districts?”

The two key stakeholders that interact within this teaching and learning space are the district officials and school principals. Drawing on a synthesis of international and local perspectives, this study examines the phenomenon of district leadership. It explores the role of districts in supporting curriculum delivery in schools, drawing on a synthesis of international and local perspectives. The theoretical underpinnings and research methodology utilised to generate the data are then outlined, followed by the presentation and discussion of the study’s key findings.

1.1 Problematising district leadership

The literature reviewed, both locally and internationally, suggests that for visible system-wide change to occur, education districts are crucial (Bantwini, 2019; Bantwini and Moorosi, 2018; Boyce and Bowers, 2018; Cobb et al., 2020; Honig and Rainey, 2020; Mthembu et al., 2024; Myende et al., 2022). A particular consideration is whether education districts operate in ways that fulfil such a crucial role. It is also unclear whether education districts’ structural arrangements facilitate their instructional leadership support mandate. What appears to be visible in SA and elsewhere is that education districts face difficulties in providing effective teaching and learning support to schools, despite policy provisions (Bantwini, 2019; Fleisch, 2018; Honig and Rainey, 2020). For instance, a culture of working in silos appears to prevail; consequently, internal communication for the purpose of coordinated support to schools seems to be lacking (Mavuso, 2013). Hence, this paper shares the views of district officials on their leadership strategies for supporting teaching and learning. They also provided insights into the challenges of supporting schools in their efforts to enhance teaching and learning. Although this paper focuses on selected DOs, we believe principals’ perspectives are important in narrating our story.

1.2 The role of education districts in supporting effective teaching and learning in schools

There has been an ongoing interest in the critical role that education district officials (globally and locally) can play in improving teaching and learning and maintaining high-quality education (Bantwini, 2019; Bantwini and Moorosi, 2018; Cobb et al., 2020; Honig and Rainey, 2020). The focus is more evident in the developed countries. However, the same cannot be said about developing countries that have evident neglect of this topic. This phenomenon of neglect persists, despite education policies increasingly envisioning improvements to the quality of education, as reflected in Chapter 9 of the National Development Plan 2030 (National Planning Commission, 2012; Department of Basic Education, 2024). The decline in quality education provision is evident in reports and research on numeracy and literacy, which suggests that learners struggle to attain literacy and numeracy skills and remain unaccounted for as a result of education systems failing to provide quality education (Asim et al., 2023; Childress et al., 2020; Spaull and Taylor, 2022). Crucially, district leaders‘beliefs about student needs serve as powerful catalysts for change, making their support essential for advancing proactive, inclusive teaching and learning practices in schools.

Even if policies that support district leadership are developed, their implementation is often dismal due to the rhetorical nature of such policies (Bantwini and Moorosi, 2017; Bantwini, 2019). A case in point is the Policy on the Organisations, Roles, and Responsibilities of Education Districts in SA, which specifies the roles and responsibilities of education districts. This policy was developed in 2013; however, there is little evidence to suggest any successful implementation to date.

Fullan and Quinn (2015) suggest that an overwhelming number of initiatives led to overload and disconnection between them, causing fragmentation. Moreover, teachers in rural schools lacked the capacity when compared to their counterparts in advantaged communities (Ehren et al., 2020). Consequently, most learners are unable to read for meaning by the end of Grade 4 (Fleisch, 2018; Spaull, 2015). Therefore, a shift is necessary to recognise the importance of district-level support and coordination across schools for educational improvement initiatives (Fleisch, 2018). This new wave emphasised systemic approaches, with a focus on recognising the DOs’ role in sustaining school improvement (Bantwini, 2019; Mthembu et al., 2020; Myende et al., 2022). We do not insinuate that this is the only solution, as challenges in SA education are complex.

Similarly, the international scholarly literature has also explored the comprehensive roles of district officials, rather than perceiving them as solely responsible for carrying out government programmes at the school level or enforcing accountability (Honig and Rainey, 2015, 2020). Scholars recognised that districts not only facilitate teaching reforms but also play crucial oversight roles over instruction at schools (Ford et al., 2020). However, due to the historical lack of attention at the district level, resources were channelled to schools, and glaring neglect was visible in the district offices. Chinsamy (2013) attributes the failure of the education system to improve teaching and learning to the lack of proper structures in district offices necessary to implement policies. Fullan and Quinn (2015) highlight the significance of internal accountability (school leaders) over external accountability, advocating for self and collective responsibility supported by external mechanisms (district leaders) rather than being solely determined by them. They further assert that many incoherent interventions are prevalent in schools because the system leaders focus on accountability-driven and compliance-based requirements (Elmore, 2004).

1.3 Theoretical framework

Rorrer et al. (2008) propose a framework that conceptualises school districts as institutional actors in systemic educational reform, emphasising their critical role in improving student achievement and advancing equity. The framework identifies four interdependent roles that districts play: providing instructional leadership, reorienting the organisation, establishing policy coherence, and maintaining an equity focus. Instructional leadership involves generating the will for reform and building the capacity to sustain improvements in teaching and learning, with leadership responsibilities extending beyond superintendents to include central office administrators and school principals.

Reorienting the organisation requires refining and aligning structures, processes, and culture to support instructional goals, including decentralisation and increased autonomy at the school level (Rorrer et al., 2008). Establishing policy coherence entails districts acting as mediators between federal, state, and local policies to ensure alignment with local needs, creating a coherent and strategic reform agenda while buffering against abrupt policy shifts (Elmore, 2004). Maintaining an equity focus necessitates that districts acknowledge past inequities and implement systemic changes to ensure equitable access to resources, transparent data use, and targeted interventions to support historically marginalised students (Rorrer et al., 2008). By integrating these roles into a cohesive model, the framework challenges the traditional view that schools alone drive reform, instead positioning districts as key agents of sustained and systemic educational improvement (Rorrer et al., 2008).

Although Rorrer et al. (2008) provide a robust theoretical framework for conceptualising the districts as institutional actors in educational improvement, this model remains under-applied in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as South Africa. Existing research on South African education districts tends to document dysfunctions and structural limitations (e.g., siloed operations, compliance enforcement, and Grade 12-focused accountability). Yet, it fails to critically engage with how district offices might perform these four interdependent roles in complex, resource-constrained environments.

Most notably, while the framework positions districts as mediators of policy coherence, this role is often absent in practice due to fragmented leadership structures and the prioritisation of bureaucratic mandates over instructional support. Similarly, the equity dimension, central to the framework, is largely neglected in district-level strategies that continue to under-serve the General Education and Training (GET) phase. The reorientation of district organisations, through collaborative practices and coherence-building mechanisms, is theoretically acknowledged but practically unfulfilled. Furthermore, instructional leadership, as defined by Rorrer et al., remains narrowly interpreted in many South African districts as performance monitoring rather than the capacity-building, relationship-driven practice envisioned by the framework.

This study addresses this conceptual gap by exploring how two education districts in South Africa navigate these four roles, particularly how they struggle with, reinterpret, or potentially extend the Rorrer et al. model in a context marked by inequality, limited capacity, and high policy pressure. In doing so, the study contributes to the contextual refinement of the framework and generates theoretical insights into how district leadership can be reimagined to support equity-focused, systemic school improvement in LMICs.

This framework serves as a valuable lens for district leadership strategies, offering a systemic and comprehensive approach to understanding the district’s role in educational reform. By identifying four essential, interdependent roles, this framework illuminates the district’s complexities in improving teaching and learning while addressing systemic inequities. Unlike other approaches focusing primarily on school-level reforms, this framework emphasises the district as a strategic actor, ensuring that change occurs at scale rather than in isolated schools (Rorrer et al., 2008).

2 Methodology

We adopted a qualitative case study for this research as it allowed for an in-depth exploration of complex social issues, such as district leadership, where the perspectives and experiences of participants are central to understanding the topic (Cohen et al., 2018; Rule and John, 2011). In this study, the bounded system, as defined by Merriam and Tisdell (2016), was the work of district leadership within two selected South African education districts. The boundaries were set by time, place, and scope: the research was conducted during a specific period, focused on two distinct geographic and administrative districts, and examined only leadership strategies and challenges in supporting teaching and learning. These parameters provided a clear focus for an in-depth, contextual investigation of the phenomenon (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016; Rule and John, 2011).

2.1 Sampling strategy

A purposive sampling strategy was used to select the two participating education districts, including the particiapnts (Cohen et al., 2018). The selection was made in consultation with the Provincial Education Department and aimed to enable an in-depth exploration of district leadership practices in contrasting contexts. One was predominantly rural and under-resourced, and the other served a more mixed socio-economic community. This allowed the study to capture variations in leadership strategies, challenges, and support practices across different settings. The sample included the District Director, Circuit Managers, and Chief Education Specialists (CES) for Curriculum Support, as defined in the Policy on the Organisation, Roles and Responsibilities of Education Districts (Republic of South Africa, 2013). The District Director, as head of the district office, provides strategic leadership, manages resources, oversees all district functions, and ensures that schools receive the necessary support to improve teaching and learning. Circuit Managers act as the direct link between the district and schools, supervising principals, supporting and monitoring teaching, and working to strengthen curriculum delivery, enhance quality, and address performance gaps. The CES (Curriculum Support) heads the Curriculum Support section, comprising Deputy CES and Subject Advisors, and is responsible for leading curriculum planning, implementation, and monitoring; providing subject-specific guidance; coordinating teacher development; and designing interventions to improve learner outcomes. Collectively, these roles are pivotal in translating district strategies into school-level practice, making their perspectives essential for examining district leadership in supporting teaching and learning.

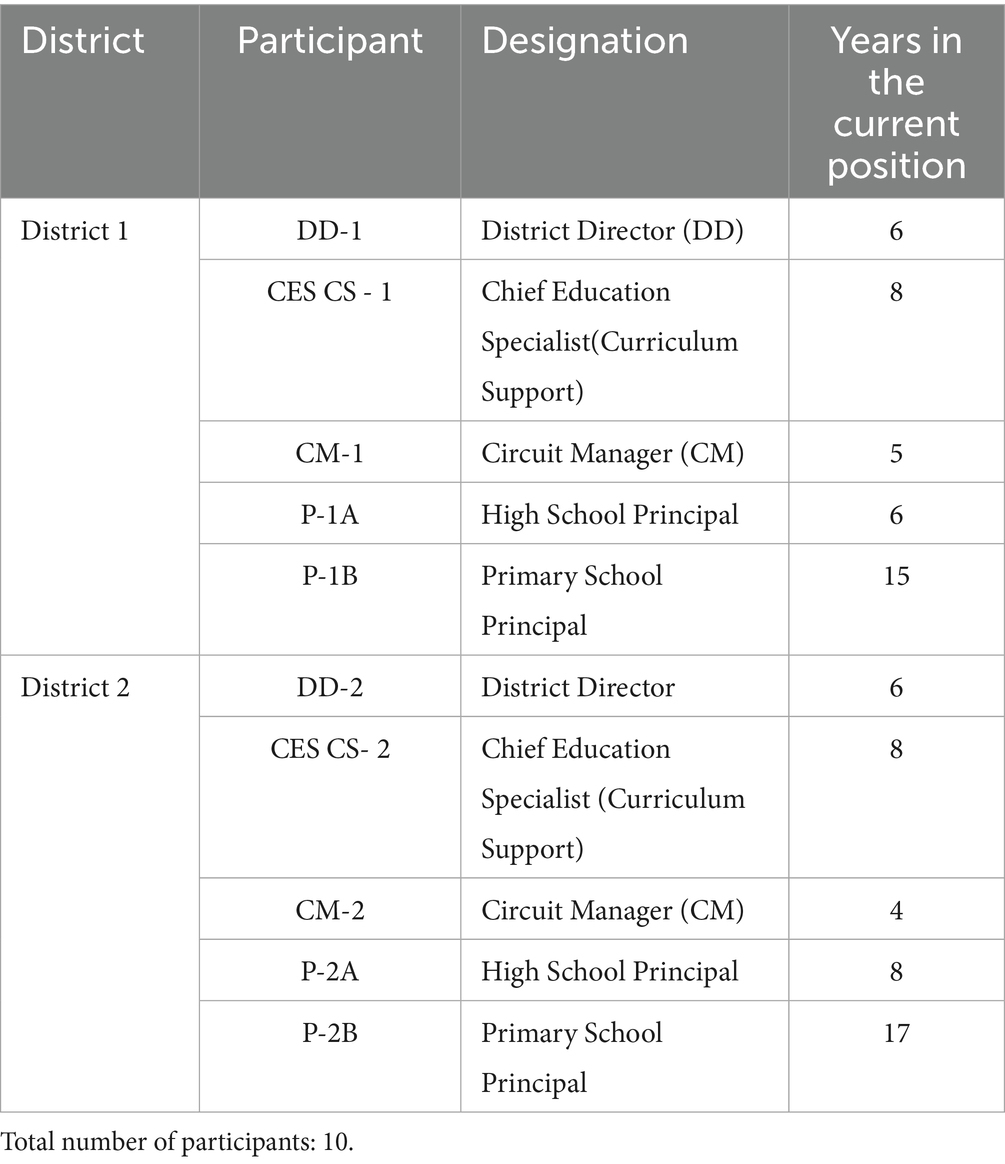

The principals were identified through recommendations from district officials, ensuring that they met the selection criteria: holding substantive leadership roles, having at least 3 years of experience as a principal, and working in schools directly supported by the participating district officials. The principals represented both primary and secondary schools, one primary school and one secondary school. This composition was intentional, allowing the study to compare leadership perspectives across phases. The total number of participants was 10 (six district-based and four school-based).

2.2 Data generation

Semi-structured interviews, lasting between 60 and 90 min, were conducted to allow for in-depth probing of participants’ experiences while maintaining flexibility in the conversation. We allowed participants to pause or reschedule if required. All interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent, using a digital voice recorder. Interviews with district officials were conducted at district offices, while those with school principals took place at their respective schools. To protect teaching time, interviews with principals were scheduled outside of classroom hours after school, based on each principal’s availability. These arrangements ensured minimal disruption to school operations while creating a comfortable environment for open and focused discussions.

2.3 Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted manually using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis framework. The first step involved transcribing all interviews verbatim from the audio recordings, a process undertaken by the authors to ensure accuracy. Listening repeatedly to the recordings allowed us to capture every detail and immerse ourselves in the data. We then familiarised ourselves with the transcripts by reading and re-reading them to gain a deep understanding of participants’ accounts. Initial codes were generated inductively by systematically highlighting significant words, phrases, and ideas linked to the research questions. These codes were organised into preliminary categories, which were refined through constant comparison across participants and groups (district officials and principals). Themes were developed by clustering related categories to reflect key patterns in the data. Each theme was reviewed, refined, and named to ensure it accurately represented participants’ perspectives. Credibility was strengthened through member checking, where selected participants reviewed interview summaries to confirm the accuracy of our interpretations, and by maintaining an audit trail documenting coding decisions and theme development (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

2.4 Ethical matters

Throughout the study, we observed all protocols. These included obtaining ethical clearance from the first author’s university, securing permission from the provincial education department to conduct the study, and ensuring that all participants participated voluntarily. One key ethical consideration was the principle of non-maleficence (Cohen et al., 2018; Rule and John, 2011). To protect participants from harm, their identities were concealed using assigned codes.

3 Findings

Thematic analysis generated three themes, and these are as follows: (a) Supporting teaching and learning through accountability sessions; (b) School capacity development; (c) Lack of synergising collaborative efforts; (d) Challenges around the Instructional Leadership role of the Education Districts. These themes are discussed next. The table below indicates the participants’ profiles and the codes we assigned to conceal their identities (Table 1).

3.1 Supporting teaching and learning through accountability sessions

We have highlighted that the primary task of the DOs, regardless of their portfolios, is to support teaching and learning in schools, thereby maintaining the quality of education. The findings suggest that one way to achieve this is through accountability sessions that DOs hold regularly with principals and SMT members. These accountability sessions are scheduled once every term. At the beginning of the year, the first sessions focus on the National Senior Certificate (NSC) [Grade 12] results from the previous year. During these sessions, schools are requested to evaluate the NSC examinations. From the perspective of the DOs, accountability sessions served as a measure to strengthen teaching and learning support mechanisms. Hence, it can be argued that accountability sessions were one-dimensional in the sense that they were only meant for schools to account for their performance in the NSC examinations. Hence, this interaction can be expanded upon. DD-2 explained that the focus was on syllabus completion, school-based assessments, and other assessment-related issues. DD-2 offered that:

We hold sessions for accounting in terms of performance. Deputies in schools account for curricula syllabus completion, school-based assessments, and any other assessments that are taking place. Principals also account at the same level.

In addition to monitoring performance through ensuring the completion of the syllabus and school-based assessment, identifying barriers to effective curriculum delivery is also highlighted. CM-1 indicated that accountability sessions were also used as platforms for principals to communicate with the DOs regarding the kind of support they required. CM-1 noted:

…after each and every term, we have what we call the accounting sessions with the principals, wherein the principals come and account for their results for the term. They also discuss their challenges, so that any problems we encounter can be identified, and then we can devise effective intervention strategies.

The above extract suggests that such discussions extend beyond principals’ accounting for their schools’ performance to also identify the challenges encountered. However, accountability appeared to be one way, with no mutual accountability from the DOs.

3.2 School capacity development

To function effectively, districts must ensure their staff have the necessary capabilities to fulfil their roles, as skill deficiencies undermine work quality. Given the need for efficient human capital, district officials are expected to support effective teaching and learning in schools through their work. This includes developing the capacity of school leaders and teachers. However, while DOs recognise the importance of building principals’ capacity, this has not materialised as anticipated. The providers and recipients of capacity-building initiatives experience the process differently, as illustrated by the perspectives detailed in the following paragraphs. DOs emphasised the critical need for capacity building of teachers, school management teams, and principals to improve learner performance, and therefore adopted a multi-pronged approach to professional development. They reasoned that it was essential for the DOs themselves to be properly capacitated to develop school-based educators. To that end, DD-1 noted: We have a strategy to develop internal staff. We believe that we cannot send people out there without knowing what to do. So, we are focusing on staff and developing our own people within the district office.

The other District Director shared a similar view and indicated that among district-based officials, only Subject Advisors urgently required capacity building: We must build capacity for subject advisors. Because we do not want to throw our people into the deep end, we have to capacitate them first (DD-2).

The above excerpts highlight the importance of human capacity development in bringing about district efficiency. While the DOs pride themselves on providing leadership support to school principals, the principals in the study presented the opposite experience altogether. In particular, P-1A decried the serious lack of knowledge about some policies and the capacity to lead effectively.

We really need training on curriculum management, understanding the policies, admission policies, and how to support the school management. Instead of the district coming to schools and expecting principals to provide information, at times, similar information (P-1A).

Echoing similar sentiments, another experienced school principal added that the challenge of deficient/inadequate capacity-building measures indicated that no induction programmes were organised for early-career principals and no mentorship programmes existed. She stated:

As principals, it is about whether you swim or sink. There is no proper induction and mentoring for the newly appointed. Instead, you are allocated another experienced principal as a mentor. That principal is very busy and does not have time to offer guidance and support (P-2B).

Participating principals argued that ordinary meetings were sometimes used merely to pass on information from senior officials in the education department. In short, district officials expect principals to convey information rather than utilise their time to effectively support their teaching staff and facilitate engagement. In particular, P-1A noted that the teachers received proper training. Moreover, P-2B decried the under-utilisation of effective time management as these interaction sessions have the potential to engage more deeply with the DOs. Within a one-directional approach, principals lose interest in the proceedings and become passive listeners.

They call the teachers and capacitate them, but if principals are not at the centre of such activities, it is a huge problem. I am the one who should be leading (P-1A).

We are called to meetings where we sit and listen to a lengthy agenda. If the meetings could change to a form of engagement, we must be free to share our views. We are the ones who are on the coalface, if they could listen to us. Most of the time, we just keep quiet and listen to things that are not related to the business of teaching and learning, especially in primary schools (P-2B).

The above quotes suggest the need for capacity development, both for district staff and school leaders, and to tailor interactions between the DOs and principals to be collaborative.

3.3 Challenges around the instructional leadership role of the education districts

The findings have shown that DOs utilised some strategies aimed at improving learner academic outcomes, but some challenges were encountered. The findings presented under this theme are divided into three sub-themes, namely, (a) Lack of aligning collaborative efforts, (b) Lack of Synergy in the District Office resulting in a Lack of Trust by Principals and (c) The focus on Grade 12, neglecting GET.

3.3.1 Lack of aligning collaborative efforts

In the background section of this paper, we indicated that districts are, by design, theoretically earmarked to provide support to the schools, and in so doing, they are expected to operate as a unit. In other words, it is expected that the activities of different sections/units should not compete with one another; rather, they should complement one another. However, this study revealed that there are overlaps between different sections/units, and such practices did not provide a unified, integrated programme. Therefore, there are missing synergies in the way the two districts operate. This results in misalignment of collaborative efforts and coordination. Such a lack of coordination contributes to the principals’ wasteful usage of time. One principal said:

District officials need to work together and not confuse schools; curriculum support and examination departments do not correspond. For example, the Natural Science exam is on the 14th of October, but the Annual Teaching Plan (ATP) says it will finish on the 19th of October (P- 1B).

This district official confirms the lack of synergising planning endeavour:

It is difficult for these principals because we often call them out of school. Different sub-directorates want them: teacher development, FET, LTSM, and many more, Circuit Manager. We will find that the circuit manager is interested in the curriculum. In that case, we find that two messages have been communicated to one teacher, creating problems (CES CS-1).

The extract above suggests serious issues of the lack of role clarity. We note with interest that district officials are aware of their operational deficiencies and inadequacies, where collaboration is not focused upon. They acknowledge the fact that such deficiencies result in disjointed interventions that are not informed by insights about the realities experienced in Schools A district officials suggested that such fragmentations should be addressed:

We wish that, as the curriculum support division for Grades 10 to 12, we could have a collaborative relationship with the lower grades’ curriculum division. At times, there are issues that we identify at higher grades that could be addressed at lower grades. We really need to develop the relationship (CES CS-2).

This excerpt suggests minimal collaboration between the General Education and Training Phase (lower grades) and the FET Phase (senior grades). In addition, being aware of these challenges and deficiencies, the district officials even proposed solutions for the lack of synergies. One district official recommended:

There is a need to have a synergy between circuit management and Curriculum support…we need times when circuit management and curriculum sub-directorate come together, and we say these are the challenges that we experience. Can you work together to close these gaps? (CES CS-2)

The proposed solutions are geared towards the focus on effectively supporting efficient and collaborative curriculum delivery. One of the major challenges highlighted in the preceding theme is the lack of alignment of the DOs’ collaborative efforts and coordination. Evidently, the district does not seriously consider itself a provider of instructional leadership, and school-based stakeholders do not receive the support they deserve.

3.3.2 Lack of synergy in the district office resulting in lack of trust by principals

The above quote amplifies the repercussions of the lack of coordination and synergy in the work of the education districts, which sometimes. Principals bore the brunt of this as they were frequently called for meetings by different units because of the coordination challenges in the district offices. Two principals shared their frustrations:

There is no communication among them like the curriculum department calls principals for a meeting, then the labour sub-directorate, and then the circuit manager (P- 1B).

You see, this week we had meetings. Is it worth it? At the same time, I have classes to teach. They are time-consuming and sometimes do not have direction. Principals cannot be out of school frequently because, in the end, we need to be accountable (P-2A).

Quite telling from the above quotes is that the planning and coordination in the district studied was dismal, resulting in principals’ frustration as the numerous meetings hindered them from their core duties in the schools. Instructional leaders are expected to understand the school context and be acquainted with the difficulties (if any) that schools experience.

3.3.3 The focus on grade 12, neglecting GET

While DOs aspired to improve teaching and learning in the districts, their focus gravitated towards Grade 12. Data revealed concerns regarding the main focus on Grade 12 at the expense of the lower grades, which appear neglected. Principals believed that they were held accountable for Grade 12 results. This is what they said:

I end up focusing on Grade 12 because if I do not, I will be in trouble if the learner performance at Grade 12 declines (P-2A).

We sometimes find ourselves having to push all resources to Grade 12, which is unfortunate. We cannot expect to get good results in Grade 12 if the lower grades are not supported (P-1A)

DOs shared similar sentiments:

Unfortunately, we are measured by your Grade 12 results, disregarding lower grades. That is why you will see most of the focus is on Grade 12, which I feel is wrong …our results are consistently above 80% in Grade 12, but now go to Grade 9, it is a dismal performance (CES CS-1)

Quite telling from the above quotes is the neglect of lower grades. Even though the district officials prided themselves on supporting all grades, findings reveal that principals felt not supported, especially primary school principals. Resources and interventions focus on high schools, precisely Grade 12.

4 Discussion of findings

The key question of this study explores how district officials (DOs), as district leaders and principals, perceive leadership strategies for supporting teaching and learning in schools and the significant challenges they encounter. Findings suggest that district officials were cognisant of their central role within the education system. However, their attempts to lead from the middle were largely ineffective due to varied understandings among stakeholders. The research underscores that high-performing districts foster a culture of shared responsibility for student outcomes, enabling effective principal leadership (Honig and Rainey, 2020; Myende et al., 2022). In such districts, DOs and school leaders should collaborate and support each other to achieve mutual educational success. Accountability sessions should be reciprocal, not solely demanding accountability from schools. DOs must also be held accountable for the support they provide to schools. This balanced and reciprocal accountability framework has been acknowledged by various scholars (Ehren et al., 2020; Smith and Benavot, 2019; White, 2020) for promoting maximum accountability.

Despite the expectation that districts provide tailored support to schools, research has consistently found that such support remains inadequate (Bantwini, 2019). This aligns with the current study’s findings, where DOs failed to engage principals meaningfully, depriving districts of the opportunity to understand the school-level lived realities. Furthermore, the absence of such engagement prevents school principals from sharing their views, experiences, and frustrations, creating a disconnect between district-level initiatives and school-level implementation. This lack of alignment contributes to poor organisational management within district offices, resulting in a loss of trust between principals and district officials.

Empirical studies suggest that fostering social connections between school leaders and district administrators enhances innovation and system coherence (Bantwini, 2019; Ehren et al., 2020; Fullan and Quinn, 2015). However, this study found that divergent perceptions among these groups hinder the development of strong professional relationships (Daly et al., 2015). Additionally, research highlights persistent challenges, such as siloed operations, a lack of coordination, and inadequate support structures, that hinder the realisation of these objectives (Honig and Rainey, 2020). Rorrer et al. (2008) position districts as institutional actors in systemic educational reform, ensuring equity-driven and sustainable reforms across schools. However, findings indicate that district offices struggle to align their vision with actual practice, leading to disparities in support and outcomes across schools (Bantwini, 2019).

One of the challenges this study identified is the misalignment between what school leaders feel they are accountable for and district priorities. Principals perceive their primary accountability as improving matric (high school exit exam) results, which leads them to focus on Grade 12 performance rather than enhancing the overall quality of teaching and learning. Research corroborates these findings, revealing that conflicting agendas and accountability pressures influence instructional decisions (Cobb et al., 2020). Additionally, concerns regarding the neglect of the General Education and Training (GET) phase persist despite research emphasising primary education as the foundation for future academic success (Spaull and Taylor, 2022). The study findings suggest that a narrow national accountability framework centred on Grade 12 pass rates constrains DOs’ ability to define a comprehensive vision for high-quality education. This tunnel-vision approach results in disproportionate support for Grade 12 at the expense of lower grades.

The findings align with those of Rorrer et al. (2008), who emphasise the importance of instructional leadership in building capacity for sustained improvements in teaching and learning, thereby ensuring alignment between instructional goals, curricula, and professional development initiatives. However, this study reveals that district instructional leadership remains minimal, focusing predominantly on compliance rather than meaningful instructional support. Literature suggests that instructional leadership remains underdeveloped, as compliance-driven approaches often overshadow efforts to enhance instructional quality (Akomodi, 2025; Bantwini and Moorosi, 2018; Lindfors et al., 2025). This is particularly evident in prioritising Grade 12 results over lower grades, exacerbating the learning gaps in lower grades (Spaull and Taylor, 2022).

Another critical finding pertains to data-driven decision-making, which is essential for monitoring student performance, identifying areas for improvement, and guiding instructional and leadership choices (Honig and Rainey, 2020). However, data use is primarily reactive in the findings, with a narrow focus on matric results. This approach neglects early interventions in lower grades, contradicting Rorrer et al. (2008), who emphasise that data-driven strategies should align with district-wide instructional priorities to sustain improvement in teaching and learning. Consequently, district leaders prioritise accountability measures over proactive instructional enhancement.

Collaboration and shared leadership are fundamental to fostering teamwork among educators, administrators, and stakeholders, promoting best practices and strengthening community engagement (Mthembu et al., 2020). Rorrer et al. (2008) highlight that districts should act as institutional agents facilitating collaboration across all schools. However, while collaboration is encouraged, systemic barriers such as a top-down approach and misaligned priorities hinder its effectiveness. This study’s findings corroborated Bantwini’s (2019) findings that the lack of synergy between different divisions in the district results in duplicated efforts and inefficient use of resources.

Another significant issue is the absence of regular, structured, and coordinated communication channels, resulting in fragmented district operations. This misalignment leads to duplicated efforts and conflicting initiatives. Without the coordination, different divisions, such as circuit managers and subject advisors, operate in silos, often unaware of each other’s activities and priorities. Rorrer et al. (2008) emphasise the need for districts to reorient their organisations by improving cross-departmental collaboration and breaking down bureaucratic silos. Successful district offices, in contrast, employ coordinated strategies to organise themselves and provide adequate support for teaching and learning (Cobb et al., 2020; Honig and Rainey, 2020; Mthembu et al., 2024).

Lastly, principals in the study reported a lack of professional development opportunities despite the Policy on the Organisations, Roles, and Responsibilities of Education Districts in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, 2013) mandating DOs to focus on professional development. Effective professional development should be responsive to the specific needs of school principals. However, the study reveals that such initiatives are often imposed rather than tailored, leading to ineffective outcomes. DOs, particularly District Directors and Circuit Managers, demonstrated a limited understanding of designing development programs that align with schools’ needs. The primary challenge appears to be the inability to harmonise individual capacities with organisational resources, thereby hindering efficiency and effectiveness.

5 Conclusion

Overall, the findings highlight significant structural and operational challenges within district leadership. While DOs recognise their systemic role, persistent issues such as inadequate instructional leadership, reactive data use, a fragmented support system, and a narrow focus on Grade 12 outcomes impede meaningful educational improvement. Addressing these challenges requires a shift towards a more cohesive, collaborative, and instructional-support-driven approach to district leadership that aligns policy mandates with practical implementation to foster sustainable school improvement.

Theoretically, the study highlights the need for education districts to shift from a compliance-driven approach to one that emphasises proactive instructional leadership and collaboration throughout the district. Thus, framing instructional leadership as a cohesive, district-wide effort aligns with Rorrer et al.’s (2008) organisational reorientation construct, advocating for dismantling ineffective hierarchies and fostering adaptive, learning-focused systems. Overall, this study broadens Rorrer et al.’s framework, advocating for a strategic, action-oriented, and collaborative approach to district leadership as a catalyst for transformative educational change. The practical implication is the critical need to establish structured communication frameworks and shift from a compliance-centric accountability paradigm to a support-focused model that emphasises professional development and data-informed interventions across all schools.

The framework positions districts as mediators of policy coherence, but this role is often absent in practice due to fragmented leadership and prioritisation of bureaucratic mandates over instructional support. The equity dimension is also largely neglected in district-level strategies that under-serve the General Education and Training phase. While the reorientation of district organisations through collaborative practices is theoretically acknowledged, it remains unfulfilled in practice. Further, instructional leadership is narrowly interpreted as performance monitoring rather than the capacity-building, relationship-driven practice envisioned by the framework. The study’s findings necessitate a significant change in district leadership, advocating for collaborative instructional support over compliance-focused oversight, thereby transforming districts into facilitators of school improvement. To achieve this, enhancing cross-functional coordination among curriculum, circuit management, and assessment units is crucial, ensuring synergised support through integrated planning and mechanisms. Furthermore, the GET phase requires immediate attention, with resources and interventions targeted towards early grade learning. Moreover, professional development should be responsive and needs-based, particularly through structured induction and mentorship for new school leaders. Accountability systems should foster reciprocal engagement, empowering principals to co-shape district interventions. The study also recommends a shift from narrow, summative data use to formative, system-wide practices that inform instructional decisions across all grades, collectively reinforcing the district’s strategic role in fostering equitable and sustainable educational improvement.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the growing body of research on district leadership in South Africa, suggesting that enhanced district support could lead to a more inclusive and coherent approach across the district and its schools. The key principle that emerges from the findings is the need for coherent and collaborative instructional leadership strategies across the school district. This principle underscores the need for district officials to move beyond fragmented, compliance-driven practices towards a unified, supportive approach that centres on collaboration, coherence, and capacity building. It calls for systemic alignment across all district units, such as circuit management and curriculum support, so that their efforts complement rather than contradict one another. Effective district leadership must foster reciprocal accountability, where both schools and district officials are mutually responsible for learner outcomes. It also emphasises the need for equitable attention to all grades, including the often-neglected GET Phase, and for meaningful engagement with school principals to understand their contextual realities. By promoting trust, shared decision-making, and targeted professional development, this principle positions districts not as bureaucratic overseers, but as institutional actors that enable sustained improvement in teaching and learning across the system.

However, this study had methodological limitations, including small sample size, reliance on potentially subjective qualitative interviews, and exclusion of key stakeholders beyond district leaders and school leaders. Nevertheless, in-depth interviews, analysis strategy and trustworthiness measures ensured a nuanced, context-specific understanding of the selected districts’ leadership. Future research should expand the scope, use mixed methods, and incorporate a broader range of perspectives to address these limitations. Addressing these gaps will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of district leadership’s role in promoting educational improvements in South Africa.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Witwatersrand Ethics Review Board and The University of KwaZulu-Natal Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. TB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by NRF funding grants HSD210311589722 and CSUR23032887839.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammarly was used for language editing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akomodi, J. O. (2025). In-Depth Analysis: The Importance of Instructional Leadership in Education. Open Journal of Leadership 14, 177–193. doi: 10.4236/ojl.2025.142008

Asim, M., Mundy, K., Manion, C., and Tahir, I. (2023). The ‘missing middle’ of education service delivery in low-and middle-income countries. Comp. Educ. Rev. 67, 353–378. doi: 10.1086/724280

Bantwini, B. D. (2019). District officials’ perspectives regarding factors that impede the attainment of quality basic education in a province in South Africa. Education 3–13 47, 717–729. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2018.1526200

Bantwini, B. D., and Moorosi, P. (2017). School district support to schools: voices and perspectives of school principals in a province in South Africa. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 20, 757–770. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2017.1394496

Bantwini, B. D., and Moorosi, P. (2018). The circuit managers as the weakest link in the school district leadership chain! Perspectives from a province in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 38, 1–9. doi: 10.15700/saje.v38n3a1577

Boyce, J., and Bowers, A. J. (2018). Different levels of leadership for learning: investigating differences between teachers individually and collectively using multilevel factor analysis of 2011–2012 schools and staffing survey. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 21, 197–225. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2016.1139187

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Childress, D., Chimier, C., Jones, C., Page, E., and Tournier, B. (2020). Change agents: Emerging evidence on instructional leadership at the middle tier. Education Development Trust.

Chinsamy, B. (2013). “Improving learning and learner achievement in South Africa through the district office: the case of the district development support programme” in The search for quality education in post-apartheid South Africa: Interventions to improve teaching and learning. eds. S. Sayed, A. Kanjee, and M. Nkomo (Pretoria: HSRC Press).

Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Henrick, E., and Smith, T. M. (2020). Systems for instructional improvement: Creating coherence from the classroom to the district office. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn. London: Routledge.

Daly, A. J., Moolenaar, N. M., Liou, Y. H., Tuytens, M., and del Fresno, M. (2015). Why so difficult? Exploring negative relationships between educational leaders: the role of trust, climate, and efficacy. Am. J. Educ. 122, 1–38. doi: 10.1086/683288

Department of Basic Education (2024). Annual performance plan 2014–2015. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education.

Ehren, M., Paterson, A., and Baxter, J. (2020). Accountability and trust: two sides of the same coin? J. Educ. Change 21, 183–213. doi: 10.1007/s10833-019-09352-4

Elmore, R. F. (2004). School reform from the inside out: Policy, practice, and performance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fleisch, B. (2018). The education triple cocktail: System-wide instructional reform in South Africa. Cape Town: Juta.

Ford, T. G., Lavigne, A. L., Fiegener, A. M., and Si, S. (2020). Understanding district support for leader development and success in the accountability era: a review of the literature using social-cognitive theories of motivation. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 264–307. doi: 10.3102/0034654319899723

Fullan, M., and Quinn, J. (2015). Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Honig, M. I., and Rainey, L. R. (2015). “How school districts can support deeper learning: the need for performance alignment” in Students at the Center: Deeper learning research series. ed. M. I. Honig (Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future).

Honig, M. I., and Rainey, L. R. (2020). Supervising principals for instructional leadership: A teaching and learning approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Lindfors, T., Ahtiainen, R., Heikonen, L., and Toom, A. (2025). Leading cooperative professional development in educational reform at school, local and regional levels. Research Papers in Education, 1–26.

Mavuso, M. P. (2013). Education district support for teaching and learning in schools: The case of two districts in the eastern cape. South Africa: University of Fort Hare.

McLennan, A., Muller, M., Orkin, M., and Robertson, H. (2018). “District support for curriculum management change in schools” in Learning about sustainable change in education in South Africa. eds. S. Berkhout and I. Wasserman (Johannesburg: Saide), 225–251.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. 4th Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mthembu, P. E., Bhengu, T. T., and Chikoko, V. (2020). Leading from the middle for improving teaching and learning outcomes: perspectives from two education districts in South Africa. PONTE International Journal of Science and Research, No. 76.

Mthembu, P. E., Blose, S. B., and Mkhize, B. N. (2024). The influence of circuit managers on learner performance in a thriving rural district. J. Educ. Stud. 23, 107–124. doi: 10.59915/jes.2024.23.3.7

Myende, P. E., Ncwane, S. H., and Bhengu, T. T. (2022). Leadership for learning at district level: lessons from circuit managers working in deprived school contexts. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 50, 99–120. doi: 10.1177/1741143220933905

Naicker, S. R., and Mestry, R. (2015). Developing educational leaders: a partnership between two universities to bring about system-wide change. S. Afr. J. Educ. 35, 1–11. doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n2a1085

National Planning Commission (2012). National Development Plan 2030: Our future–make it work. Pretoria: Sherino Printers.

Republic of South Africa (2013). Policy on the organisation, roles and responsibilities of education districts. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa.

Rorrer, A. K., Skrla, L., and Scheurich, J. (2008). Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 307–357. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08318962

Smith, W. C., and Benavot, A. (2019). Improving accountability in education: the importance of structured democratic voice. Asia Pacific Review, 20, 193–205.

Spaull, N. (2015). Schooling in South Africa: how low-quality education becomes a poverty trap. S. Afr. Child Gauge 12, 34–41.

Spaull, N., and Taylor, S. (2022). Early grade Reading and mathematics interventions in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Twalo, T. (2017). Improving the probability of policy acceptance and implementation: Lessons from the Gauteng Department of Education. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

Keywords: district leadership, supporting teaching and learning, district leadership challenges, South African school districts, district leadership strategies

Citation: Mthembu PE and Bhengu TT (2025) District leadership strategies and its challenges in supporting teaching and learning: perspectives of two districts in South Africa. Front. Educ. 10:1629153. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1629153

Edited by:

Gladys Merma Molina, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Jimmy Nebrida, Bahrain Polytechnic, BahrainTshepo T. Tapala, North-West University, South Africa

Michael Mahome, University of the Free State, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Mthembu and Bhengu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pinkie Euginia Mthembu, cGlua2llLm10aGVtYnVAd2l0cy5hYy56YQ==

Pinkie Euginia Mthembu

Pinkie Euginia Mthembu Thamsanqa Thulani Bhengu

Thamsanqa Thulani Bhengu