Abstract

Mental health remains a pressing and persistent concern within educational discourse, influencing the decisions of policymakers, practitioners, and school communities alike. A growing number of children and young people are presenting with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and behavioral difficulties within school settings. Despite the implementation of various wellbeing initiatives, access to appropriate mental health support services across England remains inconsistent and often inadequate. As a result, teachers are frequently left to manage complex mental health needs without sufficient training or resources. While interventions such as mindfulness programmes aim to foster mental wellbeing, they are not always rigorously evaluated or effectively integrated into broader approaches that consider the holistic relationship between body and mind. This paper investigates the multifaceted and interconnected nature of wellbeing, with a particular focus on the dynamic interplay between physical and mental health. It further explores the role of mindfulness practices in educational contexts, considering how such initiatives might extend their impact beyond emotional regulation and metacognitive development. The analysis aims to identify opportunities for developing holistic, inclusive, and sustainable strategies that empower young learners to make healthier, more informed life choices. Ultimately, this paper poses critical questions about prevailing research priorities and the methodological approaches used to define and assess the effectiveness of school-based interventions designed to support and enhance children's wellbeing.

Introduction

Recent data highlights a continued rise in mental health issues among children and young people, especially since the pandemic. According to NHS Digital (2023), around 20% of those aged 8–25 are likely to have a mental health condition. Globally, UNICEF (2025) reports a steady decline in child wellbeing across high-income nations. Using data from OECD (2024), UNICEF assesses wellbeing through six indicators: mental health (life satisfaction and youth suicide rates), physical health (child mortality and obesity), and skills (academic and social competencies). Among 36 OECD and EU countries, the UK ranks 27th in mental health, 22nd in physical health, and 15th in skills, highlighting the urgent need for stronger national efforts to support young people's wellbeing. Although mental health is increasingly acknowledged in policy and educational discourse, this article brings together recent research on mental health provision, physical activity, and mindfulness. Grounded in the first-hand experience of a former teacher, it anchors the discussion in the day-to-day realities of classroom life. The aim is to explore how schools can move beyond narrow, outcome-focused mental health initiatives toward more integrated, holistic strategies that genuinely nurture pupil wellbeing.

The following review of literature employed a systematic approach to identify, evaluate, and synthesize research and policy related to school-based mental health interventions primarily within the UK. Comprehensive searches were conducted across ERIC, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Google Scholar using a combination of keywords, including mental health, wellbeing, school interventions, mindfulness, physical activity, children and adolescents. Key data including research objectives, methodologies and findings, were extracted and thematically analyzed to identify recurring patterns and trends. Although all studies underwent quality appraisal, inclusion criteria merits further reflection to ensure transparency and rigor.

My positionality, shaped by 25 years of experience as a primary school teacher, informed the lens through which this review was conducted. With a background in leading Physical Education, PSHE (Personal, Social and Health Education), and initiating whole-school wellbeing strategies, I bring a perspective that values the integration of theory, classroom practice and implementation within school settings. Priority was given to peer-reviewed empirical studies, systematic reviews, and policy documents employing diverse methodological approaches however practitioner-led research and gray literature were also included to offer valuable insights into lived experiences and challenges. This inclusive strategy aimed to balance academic rigor with practical relevance, supporting a nuanced and contextually informed synthesis of the evidence. This article critically examines school-based mental health and wellbeing initiatives, with a particular focus on their inclusivity, effectiveness, and long-term sustainability. Although centered on the English education system, the findings may offer broader insights, aligning with global efforts to enhance the wellbeing of children and young people (World Health Organisation, 2018).

Critical considerations for supporting mental health and wellbeing in schools

While mental health services are fundamentally designed to prevent, manage, and support mental health challenges (Norwich et al., 2022), they remain inadequate for many children and young people in England (Lowry et al., 2022). Children's Commissioner (2025) reports that the NHS in England can only meet the needs of around one-third of diagnosed children, with regional inequalities in access, funding, and waiting times further compounding the problem. Teachers, alongside GPs and social workers, are responsible for early identification and referral however limited specialist care has led to growing reliance on educators to support a wide range of needs (Lowry et al., 2022). While NHS England (2023) emphasizes the importance of early support for emotional distress, even in the absence of a formal diagnosis, teachers' daily interactions with pupils uniquely position them to identify and respond to emerging concerns (Lowry et al., 2022). Research also links strong pupil-teacher relationships to improved long-term health outcomes (Kim, 2021). Consequently, educators must be equipped not only to address mental health challenges but also to actively foster wellbeing through a comprehensive, whole-school approach (The Association for Child Adolescent Mental Health, 2024).

The Whole School Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing (Public Health England, 2021) is a widely utilized model (Mentally Healthy Schools, 2025) actively endorsed by the UK government. The approach outlines key factors including identification of need, targeted support, and appropriate referral pathways. Additional priorities highlight the role of active leadership, staff development for personal and pupil wellbeing, meaningful engagement with parents and carers, pupil voice in decision-making, and the cultivation of an inclusive school culture that values diversity. The final dimension relates to teaching and learning, specifically the promotion of resilience and social and emotional learning. In this context, mental health is framed through the lens of emotional wellbeing, with an emphasis on prevention, early identification, timely support, and access to specialist services. While schools are increasingly called upon to support pupils' mental health, this expanded role should not overshadow their core educational mission to integrate academic learning with the development of skills and dispositions necessary to lead flourishing, meaningful lives (Norwich et al., 2022). The following model serves as a valuable guide in this regard.

Concepts of holistic wellbeing for supporting both body and mind

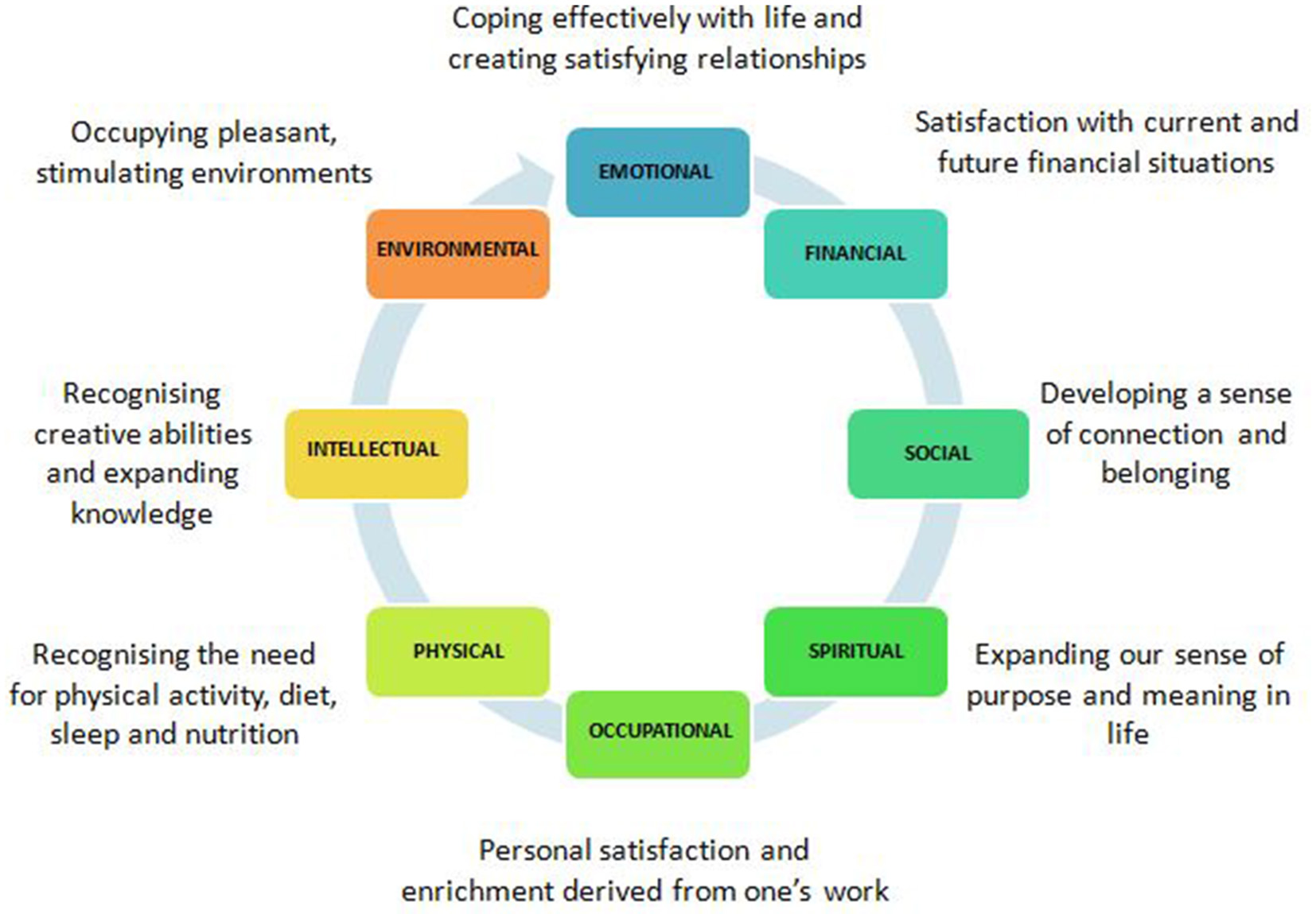

Swarbrick's (2013) Wellness Model (Figure 1) illustrates eight interrelated dimensions of wellbeing. While some aspects naturally progress as a child grows, and others may be significantly shaped by external factors, each dimension is meant to be recognized, cultivated, and developed over time. When used as a guiding framework, this model illustrates how many components of a broad, balanced and creative school curriculum can nurture holistic wellbeing.

Figure 1

Dimensions of wellbeing (adapted from Swarbrick, 2013).

Literature emphasizes the interconnectedness of wellbeing, particularly the relationship between mental and physical health. NHS England (2022) identifies five key actions to promote wellbeing: connecting with others, being physically active, learning new skills, giving to others, and practicing mindfulness, the latter discussed in more detail below. These actions align with UNICEF's (2025) three core domains of wellbeing: mental, physical, and cognitive/social. Mind (2025) highlights the positive impact of physical activity on mental health, advocating for inclusive, non-competitive approaches tailored to individual preferences. Wolf et al. (2021) demonstrate that regular exercise can reduce anxiety and depression, improve sleep, and enhance both cognitive and emotional functioning. Reflecting on Swarbrick's (2013) model, physical activity can also contribute to social connection, a sense of belonging, creativity, and learning, reinforcing the multi-faceted nature of wellbeing.

Although regular physical activity is widely linked to positive health outcomes (World Health Organisation, 2019), sedentary behaviors are on the rise (Guthold et al., 2018). While adult-focused interventions often show limited long-term success (Macali et al., 2025), school-based programmes targeting children tend to yield more promising results (World Health Organisation, 2021). Despite clear guidelines, over 80% of school-aged children globally fall short of the recommended 60 min of daily moderate-to-vigorous activity (World Health Organisation, 2022). Contributing factors include reduced outdoor play, increased screen time (Palmer, 2015), and barriers such as low confidence, peer pressure, and body image concerns (Youth Sport Trust and University of Manchester, 2025). Although students recognize the benefits of physical activity, persistent digital distractions and self-esteem issues hinder participation. The report calls for more curriculum time, funding, and staff training. Complementary strategies like mindfulness may help boost motivation, confidence, and long-term engagement in healthy behaviors.

Mindfulness, often referred to as present-moment awareness, is identified as one of the five key actions for enhancing wellbeing (NHS England, 2022). While gaining significant prominence across scientific, educational, and public domains, conceptual clarity remains limited, with understandings often appearing vague or inconsistent (Roychowdhury, 2021). Originating in ancient Eastern spiritual traditions and cultivated through disciplined practice, mindfulness has more recently been critiqued for its commodification, superficial application and portrayal as a universal solution to a wide range of issues (Purser, 2019). These tensions remain the subject of ongoing debate (Konishi et al., 2024) and will be explored in more depth later in this article. Nevertheless, mindfulness programmes are increasingly being adopted in educational settings worldwide, supported by a growing body of evidence (Mindfulness in Schools Project, 2024a). A widely accepted definition describes mindfulness as “the awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgementally” (Kabat-Zinn, 2005, p. 45). This framing highlights the intentional and reflective dimensions of mindfulness, aligning closely with educational aims to foster self-awareness, emotional regulation, and metacognitive development in learners. A more nuanced understanding may suggest that intentional living, cultivated through self-awareness and self-regulation, has the potential to enhance all dimensions of wellbeing.

Recent initiatives and reported evidence of effectiveness

The UK government expects schools to select, implement, and evaluate mental health interventions based on robust evidence, ensuring they are effective and contextually appropriate (Department for Education, 2021). This guidance promotes a whole-school approach and recommends appointing a designated mental health lead. Although the government has committed to providing Mental Health Support Teams in all schools by 2030 (Department for Education, 2025a), training funding is currently paused. While resource hubs and toolkits are available, they can be overwhelming and time-consuming to navigate, especially for busy staff, making it difficult to identify tools tailored to specific school needs. Additionally, questions remain around what constitutes a valid evidence base.

Two major quantitative studies currently shape the UK's understanding of mindfulness in education. The MYRIAD project (Kuyken et al., 2022) was an eight-year study that implemented a 10-lesson mindfulness curriculum in secondary schools, delivered by classroom teachers using structured instructional manuals. The results found negligible benefits compared to standard social and emotional learning. Weare and Ormston (2022) critique these findings heavily, highlighting that the teachers involved were not adequately trained. More recently, a large-scale evaluation by the UK Government Social Research team (Department for Education, 2025b) examined mindfulness interventions across primary and secondary schools. While some small positive effects were observed in secondary settings, the overall impact on pupils' mental health and wellbeing was not statistically significant or consistent. Weare and Bethune (2024) highlight numerous qualitative research projects that illustrate contrasting perspectives in both detail and results.

Considering the interrelated dimensions of physical and mental wellbeing, Weare and Bethune (2024) emphasize that while mindfulness is often framed as a mental discipline, its core practices are rooted in bodily and sensory awareness. Techniques such as breath-focused attention, body scans, mindful eating, and walking cultivate a deeper connection to physical sensations, highlighting the embodied nature of mindfulness. An expanding body of research supports the role of regular mindfulness practice in fostering healthier behaviors (Howarth et al., 2019; Allen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Present-moment awareness helps individuals pause before reacting to impulses, such as cravings or avoidance of activity, enabling more intentional choices. Enhanced bodily awareness also improves recognition of internal cues like hunger, fatigue, or tension, promoting healthier responses. Given the strong link between chronic stress and unhealthy behaviors, mindfulness may reduce stress, improve sleep, and support emotional regulation. Fully engaging in activities like eating, resting, or exercising can also increase enjoyment and motivation, encouraging sustained participation in health-promoting behaviors. Further studies link higher mindfulness levels with increased physical activity (Sala et al., 2019), healthier eating (Murphy et al., 2012), better sleep (Bogusch et al., 2016), and greater self-efficacy for behavior change (Gilbert and Waltz, 2010). However, the majority of existing research focuses on adult populations. Within school settings, mindfulness studies have primarily examined emotional and mental health outcomes although systematic reviews are beginning to explore mindfulness interventions for children with physical health conditions (Hughes et al., 2023).

Mindfulness developments in school—Connecting mind and body

The Mindfulness in Schools Project (2024b) offers a range of training programmes for educators to deliver mindfulness curricula to children and young people aged 3–18. Alongside pupil-focused content, there are courses designed to support staff wellbeing. Classroom modules typically span 6–12 h and combine PowerPoint presentations, video clips, discussions, and experiential practices. Activities include mindful movement such as stretching and walking, body scans, and sensory exercises like mindful eating, all aimed at enhancing bodily awareness. A growing body of research in both secondary (Sanger and Dorjee, 2016; Wilde et al., 2018; Volanen et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2022) and primary schools (Thomas and Atkinson, 2017; Wimmer and Dorjee, 2020; Calcutt, 2021; Crompton et al., 2024) highlights a range of benefits associated with these programmes. Delivery by trained facilitators is recommended, with the long-term goal of embedding mindfulness into school culture. However, challenges such as limited funding and inconsistent staff engagement may hinder sustainable implementation. When successfully introduced, mindfulness can be integrated throughout the school day. Simple yoga poses can support flexibility, balance, and focus, while practices like Tai Chi or mindful walking help children connect breath with movement (Fabian and Davila, 2023). In physical education, mindful breathing and body scans can enhance awareness and readiness for activity (Rohan, 2025). Once foundational principles are established, schools can explore creative ways to embed mindfulness into daily routines.

Embodied mindfulness: integrity and impact

The core principles of mindfulness require thoughtful consideration, particularly when applied in educational settings. Within the context of the Whole School Approach (Public Health England, 2021), large-scale quantitative studies may frame mindfulness as a mental health intervention. This framing underscores the importance of critically examining how wellbeing is both defined and assessed. Rather than treating wellbeing as a static or uniform state, it should be recognized as dynamic and context-sensitive, with variations across different domains. Relying solely on single-point, quantitative assessments overlook this complexity and fail to capture the evolving, lived experiences of pupils.

As previously discussed, ongoing tensions persist around the application of mindfulness in education (Konishi et al., 2024). Both secular-therapeutic and religious-spiritual interpretations present distinct challenges (Calcutt, 2021). The therapeutic model, which dominates current school-based programmes, often relies heavily on quantitative metrics and frames mindfulness primarily as a tool for building resilience. However, when stripped of its ethical and philosophical foundations, secular mindfulness risks becoming a transmission-based teaching model, vulnerable to appropriation by neoliberal agendas (Forbes, 2019). As Ergas (2019) notes, scientific discourse has redefined mindfulness in terms that align with market-driven priorities, eschewing traditional Buddhist language in favor of economically palatable narratives that fit within constrained educational timeframes.

Flor Rotne and Flor Rotne (2013) and Gilbert (2017), conceptualize mindfulness in education as a holistic way of being; one that nurtures both individual growth and collective transformation within school communities. This perspective aligns with McCaw's (2019) advocacy for a more relational, culturally responsive, and transformative approach to mindfulness. However, Nhất Hạnh et al. (2017) emphasize that meaningful mindfulness must begin with educators themselves. Their personal embodiment of mindfulness not only supports personal wellbeing (Emerson et al., 2017) but also serves as the ethical and relational foundation from which it can evolve into a pedagogical stance, characterized by noticing, reflecting, and responding calmly and effectively with present moment awareness. Dispositional mindfulness, also referred to as trait mindfulness, describes a sustained form of awareness or consciousness that extends beyond formal practice (Tomasulo, 2020; Rau and Williams, 2016). In this view, mindfulness is not merely a temporary state achieved during practice, but a consistent quality of being. It involves recognizing and expanding the space between perception and response, a space that becomes more accessible once acknowledged. Cultivating dispositional mindfulness in everyday life invites individuals to notice and widen this gap, fostering greater intentionality in thought and action.

In educational settings, this approach aligns with Cotton's (2013) emphasis on deliberate teacher behaviors, such as modeling empathy, attributing positive traits to pupils, and articulating alternative perspectives along with their possible outcomes. Similarly, Dix (2017) advocates for a calm and consistent teacher presence, encouraging practices like active listening, restorative dialogue, and problem-solving conversations throughout the school day. These behaviors reflect a mindful stance that supports both teacher wellbeing and the social-emotional development of pupils.

Conclusion

The mental health of children and young people continues to be a global concern, with wellbeing levels in the UK notably lower than in many other countries. This article offers recommendations for schools, researchers and policy makers. As access to specialist services remains limited, schools are increasingly expected to identify and support pupils experiencing emotional distress. However, a broader, more proactive approach to wellbeing is needed, one that moves beyond reactive interventions. Although the terms mental health and wellbeing are often used interchangeably, their relationship is rarely defined (Ereaut and Whiting, 2008). If schools recognize wellbeing as a multifaceted concept, this understanding should meaningfully influence both curriculum design and school culture.

Mindfulness, as a voluntary and intentional practice, requires thoughtful integration into the daily life of a school. When aligned with a school's culture and ethos, as outlined in the Whole School Framework (Public Health England, 2021), it becomes a gradual process of exploring and understanding emotions, thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors to support personal development and human flourishing (Konishi et al., 2024). However, for mindfulness to be fully embedded, it must be explicitly taught and consistently practiced, helping children develop healthier, more integrated relationships between body and mind. While initial resistance may be encountered within school communities, programmes such as the Jigsaw PSHE scheme (Wolstenholme et al., 2016), and Mindfulness in Schools curricula (Thomas and Atkinson, 2017; Calcutt, 2021) receive positive feedback for including mindfulness within a broader framework of social and emotional learning. This integration enhances both conceptual understanding and practical application, potentially marking the beginning of a school's journey toward authentic and sustainable practice.

Given the time and resource constraints faced by schools, the use of evidence-based strategies is essential to ensure both impact and efficiency. Although some large-scale quantitative studies have questioned the effectiveness of school-based mindfulness, a growing body of research presents a more nuanced view, highlighting a range of potential benefits. This underscores the need for researchers to reflect on how wellbeing is defined and measured. Rather than being seen as a fixed state, wellbeing should be understood as dynamic and context-dependent, fluctuating across different domains. Single-point assessments, particularly in quantitative research, can fail to capture this complexity. To fully understand the impact of mindfulness in education it is crucial to incorporate and synthesize qualitative research that explores pupils' lived experiences across multiple dimensions of wellbeing. Such insights can provide policymakers with a richer, more holistic understanding of how mindfulness supports children's emotional, social and physical development within real-world school contexts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Allen J. G. Romate J. Rajkumar E. (2021). Mindfulness-based positive psychology interventions: a systematic review. BMC Psychol.9:116. 10.1186/s40359-021-00618-2

2

Bogusch L. M. Fekete E. M. Skinta M. D. (2016). Anxiety and depressive symptoms as mediators of trait mindfulness and sleep quality in emerging adults. Mindfulness7, 962–970. 10.1007/s12671-016-0535-7

3

Calcutt J. (2021). An evaluation of a mindfulness programme in a primary school (thesis). Open Research Online. Available online at: https://oro.open.ac.uk/76129/ (Accessed July 22, 2025).

4

Children's Commissioner . (2025). Children's Commissioner: Children's Mental Health Services 2023-24 (May 2025) Report, Available online at: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/resource/childrens-mental-health-services-2023-24/; https://www.pslhub.org/learn/patient-safety-in-health-and-care/mental-health/children-young-people-and-families/childrens-commissioner-children%E2%80%99s-mental-health-services-2023-24-may-2025-r13171/ (Accessed May 26, 2025).

5

Cotton K. (2013). Developing Empathy in Children and Youth. Available online at: https://www.antelopespringscounseling.com/documents/articles/EmpathyChildrenYouth.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2019).

6

Crompton K. Kaklamanou D. Fasulo A. Somogyi E. (2024). The effects of a school-based Mindfulness Programme (paws B) on empathy and prosocial behaviour: a randomised controlled trial. Mindfulness15, 1080–1094. 10.1007/s12671-024-02345-2

7

Department for Education (2021). Promoting and Supporting Mental Health and Wellbeing in Schools and Colleges, GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mental-health-and-wellbeing-support-in-schools-and-colleges (Accessed May 29, 2025).

8

Department for Education (2025a). Almost Million More Pupils Get Access to Mental Health Support, GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/almost-million-more-pupils-get-access-to-mental-health-support (Accessed May 27, 2025).

9

Department for Education (2025b). Effectiveness of School Mental Health and Wellbeing- Universal Approaches in English Primary and Secondary Schools, Research and Analysis- Education for Wellbeing Programme Findings. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/680f531f11d566056bcae925/Effectiveness_of_school_mental_health_and_wellbeing_promotion.pdf (Accessed May 29, 2025).

10

Dix P. (2017). When the Adults Change, Everything Changes: Seismic Shifts in School Behaviour. Solon: Crown House Publishing Limited.

11

Emerson L.-M. Leyland A. Hudson K. Rowse G. Hanley P. Hugh-Jones S. (2017). Teaching mindfulness to teachers: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Mindfulness8, 1136–1149. 10.1007/s12671-017-0691-4

12

Ereaut G. Whiting R. (2008). What Do We Mean by ‘Wellbeing'? and Why Might It Matter?, Linguistic Landscapes Research Report DCSF-RW073. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/8572/1/dcsf-rw073%20v2.pdf (Accessed May 28, 2025).

13

Ergas O. (2019). Three roles of mindfulness in education. J. Philos. Educ.53, 340–358. 10.1111/1467-9752.12349

14

Fabian Davila L.-M. (2023). 15 Engaging Mindfulness Activities in the Classroom, Zaided. Available online at: https://zaided.com/mindfulness-activities-in-the-classroom/ (Accessed May 30, 2025).

15

Flor Rotne N. Flor Rotne D. (2013). Everybody Present: Mindfulness in Education. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

16

Forbes D. (2019). Mindfulness and Its Discontents: Education, Self, and Social Transformation. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

17

Gilbert D. Waltz J. (2010). Mindfulness and health behaviors. Mindfulness1, 227–234. 10.1007/s12671-010-0032-3

18

Gilbert F. (2017). The Mindful English Teacher: A Toolkit for Learning and Well-being. London: FGI Publishing.

19

Guthold R. Stevens G. A. Riley L. M. Bull F. C. (2018). Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health6, e1077–e1086. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

20

Howarth A. Smith J. G. Perkins-Porras L. Ussher M. (2019). Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Mindfulness10, 1957–1968. 10.1007/s12671-019-01163-1

21

Hughes O. Shelton K. H. Penny H. Thomson A. R. (2023). Living with physical health conditions: a systematic review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Children, adolescents, and their parents. J. Pediatr. Psychol.48, 396–413. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsad003

22

Kabat-Zinn J. (2005). Coming to Our Senses.New York, NY: Hyperion.

23

Kennedy M. Mohamed A. Z. Schwenn P. Beaudequin D. Shan Z. Hermens D. F. et al . (2022). The effect of mindfulness training on resting-state networks in pre-adolescent children with sub-clinical anxiety related attention impairments. Brain Imaging Behav.16, 1902–1913. 10.1007/s11682-022-00673-2

24

Kim J. (2021). The quality of social relationships in schools and adult health: differential effects of student–student versus student–teacher relationships. Schl. Psychol.36, 6–16. 10.1037/spq0000373

25

Konishi C. Chowdhury F. Tesolin J. Strouf K. (2024). Our responsibilities for future generations from a social-emotional learning perspective: revisiting mindfulness. Front. Educ.9:1359200. 10.3389/feduc.2024.1359200

26

Kuyken W. Ball S. Crane C. Ganguli P. Jones B. Montero-Marin J. et al . (2022). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Universal School-based mindfulness training compared with Normal School provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: the myriad cluster randomised controlled trial. Evid. Based Mental Health25, 99–109. 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300396

27

Lowry C. Leonard-Kane R. Gibbs B. Muller L.-M. Peacock A. (2022). Teachers: the forgotten health workforce. J. R. Soc. Med.115, 133–137. 10.1177/01410768221085692

28

Macali I. C. Dale M. Smith L. Lind E. (2025). Influences of motivation and personality on physical activity behavior: a systematic review. J. Sports Sci.43, 623–635. 10.1080/02640414.2025.2468998

29

McCaw C. T. (2019). Mindfulness “thick” and “thin”— a critical review of the uses of mindfulness in education. Oxford Rev. Educ.46, 257–278. 10.1080/03054985.2019.1667759

30

Mentally Healthy Schools (2025). Whole-school approach : Mentally healthy schools, Heads Together Mentally Healthy Schools. Available online at: https://www.mentallyhealthyschools.org.uk/whole-school-approach/ (Accessed May 30, 2025).

31

Mind (2025). Safe and Effective Practice | Sport and Mental Health, Mind. Available online at: https://www.mind.org.uk/about-us/our-policy-work/sport-physical-activity-and-mental-health/resources/safe-and-effective-practice (Accessed May 28, 2025).

32

Mindfulness in Schools Project (2024a). Evidence and Outcomes: Education-Based Mindfulness, Mindfulness in Schools Project. Available online at: https://mindfulnessinschools.org/the-evidence-base/ (Accessed May 29, 2025).

33

Mindfulness in Schools Project (2024b). Mindfulness in Schools Project (MISP) - Bringing Mindfulness to Schools, Mindfulness in Schools Project. Available online at: https://mindfulnessinschools.org/ (Accessed May 29, 2025).

34

Murphy M. J. Mermelstein L. C. Edwards K. M. Gidycz C. A. (2012). The benefits of dispositional mindfulness in Physical Health: a Longitudinal Study of Female College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health60, 341–348. 10.1080/07448481.2011.629260

35

Nhất Hạnh T. Weare K. Kabat-Zinn J. (2017). Happy Teachers Change the World: A Guide for Cultivating Mindfulness in Education. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

36

NHS Digital (2023). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023: Wave 4 Follow Up to the 2017 Survey Available online at: http://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2023-wave-follow-up/part-1-mental-health/(Accessed 25. 2025).

37

NHS England (2022). 5 Steps to Mental Wellbeing, NHS Choices. Available online at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/self-help/guides-tools-and-activities/five-steps-to-mental-wellbeing/ (Accessed May 27, 2025).

38

NHS England (2023). Children and Young People's Mental Health Services, NHS Choices. Available online at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/children-and-young-adults/mental-health-support/mental-health-services/(Accessed May 30, 2025).

39

Norwich B. Moore D. Stentiford L. Hall D. (2022). A critical consideration of “Mental Health and Wellbeing” in education: thinking about school aims in terms of wellbeing. Br. Educ. Res. J.48, 803–820. 10.1002/berj.3795

40

OECD (2024). PISA 2022 Technical Report. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-technical-report_01820d6d-en.html (Accessed July 22, 2025).

41

Palmer S. (2015). Toxic Childhood: How the Modern World Is Damaging Our Children and What We Can Do About It. London: Orion.

42

Public Health England . (2021). Promoting Children and Young People's Mental Health and Wellbeing A Whole School or College Approach, GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/promoting-children-and-young-peoples-emotional-health-and-wellbeing (Accessed May 27, 2025).

43

Purser R. (2019). Mcmindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality. London: Repeater Books.

44

Rau H. K. Williams P. G. (2016). Dispositional mindfulness: a critical review of construct validation research. Pers. Indiv. Diff.93, 32–43. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.035

45

Rohan (2025). 18 Amazing Mindfulness Activities for the Classroom, Teachers Aide Courses. Available online at: https://teacheraidecourseonline.com.au/2021/06/04/18-amazing-mindfulness-activities-for-the-classroom/ (Accessed May 30, 2025).

46

Roychowdhury D. (2021). Moving mindfully: the role of mindfulness practice in physical activity and health behaviours. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol.6:19. 10.3390/jfmk6010019

47

Sala M. Rochefort C. Lui P. P. Baldwin A. S. (2019). Trait mindfulness and health behaviours: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev.14, 345–393. 10.1080/17437199.2019.1650290

48

Sanger K. L. Dorjee D. (2016). Mindfulness training with adolescents enhances metacognition and the inhibition of irrelevant stimuli: evidence from event-related brain potentials. Trends Neurosci. Educ.5, 1–11. 10.1016/j.tine.2016.01.001

49

Swarbrick M. A. (2013). Integrated care: wellness-oriented peer approaches: a key ingredient for integrated care. Psychiatr. Serv.64, 723–726. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300144

50

The Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health . (2024). CAMHS - Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. ACAMH. Available online at: https://www.acamh.org/topic/camhs/ (Accessed May 26, 2025).

51

Thomas G. Atkinson C. (2017). Perspectives on a whole class mindfulness programme. Educ. Psychol. Pract.33, 231–248. 10.1080/02667363.2017.1292396

52

Tomasulo D. (2020). Dispositional Mindfulness: Noticing What You Notice, World of Psychology. Available online at: https://psychcentral.com/blog/dispositional-mindfulness-noticing-what-you-notice/ (Accessed February 27, 2020).

53

UNICEF (2025). Child Well-being in an Unpredictable World. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/11111/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Report-Card-19-Child-Wellbeing-Unpredictable-World-2025.pdf (Accessed May 25, 2025).

54

Volanen S.-M. Lassander M. Hankonen N. Santalahti P. Hintsanen M. Simonsen N. et al . (2020). Healthy learning mind – effectiveness of a mindfulness program on mental health compared to a relaxation program and teaching as usual in schools: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord.260, 660–669. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.087

55

Weare K. Bethune A. (2024). Implementing Mindfulness in Schools: An Evidence-based Guide. The Mindfulness Initiative. Available online at: https://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org/implementing-mindfulness-in-schools-an-evidence-based-guide (Accessed May 29, 2025).

56

Weare K. Ormston R. (2022). Initial Reflections on the Myriad Study. The Mindfulness Initiative. Available online at: https://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org/myriad-response (Accessed May 29, 2025).

57

Wilde S. Sonley A. Crane C. Ford T. Raja A. Robson J. et al . (2018). Mindfulness training in UK secondary schools: a multiple case study approach to identification of cornerstones of implementation. Mindfulness10, 376–389. 10.1007/s12671-018-0982-4

58

Wimmer L. Dorjee D. (2020). Toward determinants and effects of long-term mindfulness training in pre-adolescence: a cross-sectional study using event-related potentials. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol.19, 65–83. 10.1891/JCEP-D-19-00029

59

Wolf S. Seiffer B. Zeibig J. M. Welkerling J. Brokmeier L. Atrott B. et al . (2021). Is physical activity associated with less depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic? A rapid systematic review. Sports Med.51, 1771–1783. 10.1007/s40279-021-01468-z

60

Wolstenholme C. Willis B. Culliney M. (2016). Evaluation of the Impact of Jigsaw the Mindful Approach to PSHE on Primary Schools. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive. Available online at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/13692/ (Accessed February 27, 2020).

61

World Health Organisation . (2018). Mental Health Atlas 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization.

62

World Health Organisation . (2019). Motion for Your Mind: Physical Activity for Mental Health Promotion, Protection and Care. World Health Organisation Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/346405 (Accessed May 28, 2025).

63

World Health Organisation . (2021). Promoting Physical Activity Through Schools: A Toolkit. Geneva: World Health Organization.

64

World Health Organisation . (2022). Promoting Physical Activity Through Schools: Policy Brief . Geneva: World Health Organization.

65

Youth Sport Trust and University of Manchester (2025). The Role of PE, School Sport and Physical Activity in Supporting Young People's Mental Wellbeing: Summary Report. [PDF] Youth Sport Trust. Available online at: https://www.youthsporttrust.org/media/1u5lua0q/yst-uom-role-of-pesspa-summary.pdf (Accessed July 22, 2025).

66

Zhang D. Lee E. K. P. Mak E. C. W. Ho C. Y. Wong S. Y. S. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br. Med. Bull.138, 41–57. 10.1093/bmb/ldab005

Summary

Keywords

holistic wellbeing, mental health, physical activity, mindfulness, inclusion, promotion

Citation

Calcutt J (2025) Mindful inclusion: strategies for holistic wellbeing in schools. Front. Educ. 10:1638482. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1638482

Received

30 May 2025

Accepted

15 July 2025

Published

30 July 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Michelle Jayman, University of Roehampton London, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Francis Gilbert, Goldsmiths University of London, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Calcutt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jane Calcutt jane.calcutt@edgehill.ac.uk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.