- 1Department of English and Modern Languages, International University of Business Agriculture and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2Kathmandu University School of Education, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 3Department of English, United International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 4Kathmandu University School of Education, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 5Department of English, World University of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

The correlation between classroom activity kinds and the duration of student speaking time is essential for enhancing fluency in spoken English. This study investigates the effect of activity types and talk time on developing fluency in spoken English among Bangladeshi tertiary-level students. It used a comparative methodology, looking at two classes: a class that was taught using interactive activities (e.g., role-plays, group discussions) with 30 h of spoken practice and a class that focused on monologic activities (e.g., presentations, storytelling) with 20 h of spoken practice. Fluency improvements were evaluated via pre-tests and post-tests, while classroom observations, surveys, and interviews provided a deeper look at the attitudes of students and teachers. The quantitative analysis revealed that Class A, with interactive tasks and more speaking hours, made significantly greater progress with fluency than Class B, and qualitative results also supported the value of interactive tasks in promoting engagement and confidence. It was also found that combining grouped activities and long speaking hours improved fluency. Practical matters include adding more interactive activities to new course offerings and giving them ample time to speak. Such a study will contribute to the current knowledge of English language teaching and learning in a bilingual context with clear pedagogical implications and practices for teachers in Bangladesh and similar contexts.

1 Introduction

Speaking proficiency in English profoundly influences career progression chances within Bangladesh’s professional sector as a vital predictor of employment and economic prosperity (Roshid and Kankaanranta, 2025). Given that English has emerged as the preeminent language in global commerce and communication, graduates possessing robust oral communication skills are more favorably situated to obtain employment, pursue advanced education, and participate in international business networks (Barat and Talukder, 2023; Kayum and Ahamed, 2024). The notion of linguistic capital emphasizes that English competence yields economic advantages, bolstering employment security and status (Islam et al., 2022). Disparities in language education and socioeconomic circumstances impede many graduates, restricting their access to chances and preserving inequities (Islam et al., 2022). Accordingly, enhancing English language proficiency is crucial for individual and national progress, which requires focused ways to elevate language instruction among various social groups (Islam et al., 2022; Kayum and Ahamed, 2024).

Students in Bangladesh encounter several problems in achieving proficiency in spoken English, primarily due to insufficient instructional methods and restricted language exposure (Mridula and Ahsan, 2025). Studies demonstrate that conventional, examination-focused education prioritizes rote memory at the expense of communicative proficiency, leading pupils to have fundamental grammatical knowledge; even after that, they face difficulties in conversational abilities (Mridula and Ahsan, 2025; Rana, 2024). Moreover, socioeconomic obstacles hinder access to high-quality English education and resources, intensifying the fluency disparity (Chowdhury, 2024; Mridula and Ahsan, 2025). Educators frequently lack adequate training to proficiently instruct speaking skills, resulting in a teacher-centered classroom atmosphere that disregards participatory learning (Chowdhury, 2024; Hasan et al., 2024). Cultural attitudes about English and inadequate focus on speaking and listening in the curriculum impede students’ confidence and opportunity for practice (Kayum and Ahamed, 2024; Rana, 2024). It is imperative to tackle these complex difficulties through curriculum reforms, improved teacher training, and greater exposure to spoken English to boost student fluency in Bangladesh (Rana, 2024).

Classroom activities and speaking sessions are essential for language acquisition since they promote interactive and engaging learning environments (Hossain, 2022). Research shows that activity-based teaching strategies improve English language proficiency by fostering student engagement and confidence through speaking, listening, reading, and writing exercises (Samar et al., 2025). Furthermore, intentionally incorporating listening and speaking activities is crucial for enhancing fluency and accuracy, which are sometimes neglected in EFL classes (Asmae and Sana, 2024). Interactive activities, such as role plays and group discussions, markedly enhance speaking fluency whilst extracurricular activities like social media engagement further consolidate these skills (Zuo, 2024). Collaborative learning strategies ordering social interactions are essential for effective language acquisition as they foster supportive contexts for practicing language skills (Mohanapriya and Jaisre, 2024). Furthermore, integrating technological and cultural components into classes might augment engagement and retention, rendering the learning experience more dynamic (Suhirman et al., 2023).

Prior research (Han et al., 2023; Mridha and Muniruzzaman, 2020; Nagmoti, 2020) on interactive activities and speaking durations among tertiary students in Bangladesh indicates notable deficiencies in classroom participation and language utilization. Despite the endorsement of interactive methodologies to improve learning, numerous classrooms continue to lack adequate opportunities for active engagement and substantive communication, which is essential for addressing linguistic obstacles (Hasan, 2021). Research demonstrates that the application of task-based language teaching (TBLT) can enhance speaking proficiency; however, its efficacy is frequently impeded by instructors’ disparate levels of comprehension and execution of these methodologies (Oluwajana et al., 2019). Moreover, pair work has been recognized as an advantageous method for promoting student autonomy and improving speaking skills. However, there is a continued necessity for additional organized speaking chances within the curriculum (Azam, 2024). The findings highlight the need for enhanced interactivity and targeted speaking methods to elevate educational achievements in Bangladeshi higher education institutions (Oluwajana et al., 2019).

2 Problem statement

The current study challenge focuses on the insufficient empirical information concerning the ideal quantity of speaking hours and types of classroom activities necessary for attaining spoken English fluency, especially within the framework of Bangladeshi higher education. Students in Bangladesh face a tremendous lack of communication in the classroom and academic arena, and they also face rejection in the job market due to a lack of fluency in English and mastery (Islam and Stapa, 2021). Although proficiency in spoken English is essential for academic and professional achievement, there is a paucity of research regarding the influence of various activity types, such as interactive activities (e.g., role-plays, group discussions) versus monologic tasks (e.g., presentations, storytelling) on fluency development. The correlation between the duration of speaking practice and improvements in fluency is inadequately examined in monolingual contexts, such as Bangladesh, where learners frequently encounter distinct linguistic and cultural obstacles. The deficiency of research obstructs the advancement of evidence-based pedagogical practices, resulting in a lack of definitive commands for educators in formulating actual spoken English curricula (Arefin et al., 2024). Addressing these difficulties is essential for enhancing language education results and preparing students with the communication skills necessary for global competitiveness. Current research addresses both the activity types and hours of speaking to achieve mastery in English speaking fluency and thereby tries to solve communication issues in the classroom and rejection in job interviews.

3 Research objectives

1. Compare the effectiveness of two different sets of spoken English classroom activities.

2. Determine the impact of varying speaking hours on fluency development.

3. Identify the promising but preliminary combination of activities and speaking hours for fluency.

4 Literature review

The imperative for Bangladeshi tertiary students to develop robust spoken English skills is linked to both global integration and national economic advancement. Mastery of the English language is acknowledged as crucial for effective communication across various sectors, allowing students to participate in global discussions and obtain essential information (Sukmojati and Rahmat, 2024). Furthermore, developing spoken English skills among Bangladeshi students is essential for closing the communication gap with international professionals and significantly improving their job prospects (Akter, 2022; Cismas, 2016). However, the pathway to this mastery is fraught with significant pedagogical and systemic challenges within Bangladesh’s higher education system. This review argues that a dual-focused intervention—integrating a structured framework of activity-based pedagogy with a committed increase in allocated speaking-time practice—is critical to overcoming these obstacles. By synthesizing global research on effective language acquisition with the specific contextual realities of Bangladeshi public universities, this reorganization proposes an actionable model for developing the communicative competence so highly valued by employers (Sadasivan et al., 2021).

4.1 The Bangladeshi tertiary context

The status of spoken English in Bangladesh, particularly within its public university system, presents a paradox. Despite English being a compulsory subject for over a decade of schooling, graduates frequently find themselves unable to communicate effectively during job interviews, a failure that drastically reduces their employability prospects (Marzia and Ananna, 2017). This skills gap stems from a confluence of factors deeply embedded in the educational culture.

The predominant pedagogical model often prioritizes rote memorization of grammatical rules and literary analysis over communicative competence. This results in students with a passive knowledge of English but acute anxiety and limited active vocabulary that impede their speaking skills when required to produce the language spontaneously (Sadasivan et al., 2021; Mridula and Ahsan, 2025). The influence of the native language (L1) and a general lack of environments that encourage authentic English use further exacerbate these issues, fostering feelings of shyness and a profound fear of making errors (Akter, 2022). Compounding the problem is the frequent overlooking of explicit spoken English instruction in public universities, creating a vacuum in structured oral practice (Marzia and Ananna, 2017). Consequently, the urgency for educational programs to prioritize communicative competence—emphasizing the socio-linguistic and discourse skills esteemed by employers—has never been greater (Sadasivan et al., 2021).

4.2 Activity-based pedagogy

International research demonstrates that the enhancement of spoken language skills in adults is notably affected by diverse forms of interaction and practice (Lopez et al., 2021; Marzuki, 2023; Shanks, 2021). Activity-based pedagogy moves beyond traditional, teacher-centric monologic models to create a dynamic learning environment where students are active participants in their language acquisition journey. These activities can be categorized by their structure and the type of interaction they foster.

4.2.1 Interactive classroom activities

Interactive classroom activities, such as role-plays, debates, and structured group discussions, are proven to enhance student engagement, motivation, and speaking skills in diverse educational settings (Andreas et al., 2023). The efficacy of these approaches lies in promoting active participation, which is essential for moving knowledge from passive understanding to active production. For instance, a study in Nigeria indicated that students’ speaking skills improved significantly following participation in interactive activities, with post-test scores markedly higher than pre-test scores (Bularafa et al., 2024). Similarly, role-play has been shown to be effective in contexts as varied as rural Indonesia, enhancing speaking skills while boosting student interest and motivation. Findings consistently indicate that both in-class and out-of-class interactive activities are essential for improving language proficiency (Zuo, 2024). These activities create a low-stakes environment where students can experiment with language, receive immediate peer feedback, and build confidence—a crucial antidote to the anxiety prevalent among Bangladeshi students.

4.2.2 The strategic role of monologic activities

While interactive activities are crucial, monologic activities still hold a valuable, if more nuanced, place in the pedagogy spectrum. In tertiary education, monologic tasks significantly influence language proficiency and communication skills (Ma et al., 2024). When used strategically, teacher monologes can facilitate knowledge construction by creating semantic waves that help students navigate abstract concepts and concrete examples, enhancing academic English proficiency (Xie, 2021). Furthermore, monologic speaking tasks—such as prepared speeches or presentations—can effectively scaffold language development when integrated with peer interaction and assessment (Karpovich et al., 2021). However, a critical limitation is that monologic assessments may inadequately reflect the interactional competence required for real-world, two-way communication (Roever and Ikeda, 2022). Therefore, the goal is not to eliminate monologic practice but to balance it with interactive tasks, ensuring it serves as a building block toward more authentic communication rather than an endpoint.

4.2.3 Technology-assisted activities

Technology-assisted activities, including TED Talks, language apps like Memrise, and online speaking platforms, represent a powerful tool for enhancing speaking skills by fostering engagement and providing rich, interactive learning environments beyond the temporal and spatial limits of the classroom (López-Carril et al., 2024; Mahmood et al., 2023). Meta-analyses reveal that integrating TED Talks into language instruction can positively affect speaking competencies across various national contexts (Patty, 2024). Mobile applications boost student motivation and participation, facilitating independent and collaborative speaking practice at the learner’s own pace (Rizqa Putri et al., 2024).

However, the integration of this technology in the Bangladeshi context reveals significant gaps and challenges. Effectiveness is not automatic and is mediated by variables such as student motivation, instructor preparedness, and equitable access to technological resources (Hoa, 2023). The positive effects of tools like TED Talks are not uniform across all contexts (Patty, 2024). Therefore, successful implementation requires more than just providing technology; it necessitates pedagogical training for teachers to integrate these tools effectively and strategies to ensure digital equity.

4.3 The critical variable: allocating and utilizing speaking time

Pedagogical methods are only one half of the equation. The duration and quality of speaking practice are fundamentally correlated with fluency development. Research emphatically underscores that the quantity of practice is a profound influencer of fluency in tertiary non-native students (Hasan and Shabdin, 2017; López-Carril et al., 2024; Zuo, 2024).

4.3.1 The relationship between practice and fluency

A substantial correlation exists between the hours dedicated to speaking practice and gains in fluency, highlighting the necessity of systematic practice methods and genuine output (Baldwin et al., 2022; Yenkimaleki and van Heuven, 2025). Techniques like the 4/3/2 strategy (which involves repeated speaking with decreasing time limits) have been shown to improve fluency more effectively than conventional methods by pushing learners to process language more efficiently (Coutinho dos Santos, 2022). Similarly, authentic oral production tasks like vlogging enhance fluency by compelling learners to engage with the language independently, leading to increased confidence and self-awareness (Lopez et al., 2021). Fluency is a dynamic construct shaped by cognitive processes that improve with consistent practice; longitudinal studies confirm that regular practice enhances both speech fluency (the product) and cognitive fluency (the underlying processing efficiency) over time (de Jong, 2023; Kahng, 2024).

4.3.2 The speaking-time challenge in Bangladeshi classrooms

Despite the clear evidence, allocating sufficient speaking hours in Bangladeshi tertiary classrooms poses a formidable challenge. The obstacles are systemic: restricted classroom time, elevated student-to-teacher ratios, and an overcrowded curriculum that prioritizes content coverage over skill development (Akbaraliyevna, 2023). In such an environment, oral activities are often the first to be sacrificed. Instructors find it logistically difficult to monitor speaking tasks and provide the personalized feedback that is essential for growth (Shanks, 2021). Furthermore, the existing student anxieties—fear of making mistakes, feelings of inadequacy, and social pressure—are amplified in large classes, leading to further hesitancy to participate (Raihan Utami and Amalia, 2024; Akter, 2022). The traditional lecture format, still prevalent, does not promote the interactive conversations necessary for developing spoken proficiency (Nagmoti, 2020).

4.4 An integrated proposal for the Bangladeshi context

Addressing the spoken English deficit in Bangladesh requires a holistic strategy that synergizes activity-based pedagogy with a deliberate expansion of speaking-time opportunities. First, curriculum reform is non-negotiable. Syllabi must explicitly mandate communicative objectives and allocate a minimum percentage of class time to structured speaking activities. This moves oral practice from an optional add-on to a core component of assessment. Second, teacher training is pivotal. Instructors need professional development in managing interactive activities in large classes, providing effective feedback, and integrating technology not as a novelty but as a purposeful tool for language practice. Third, a blended learning model can help overcome the time barrier. Technology-assisted activities (e.g., using Flipgrid for video journals or Memrise for vocabulary building) can extend practice outside the classroom, freeing up in-person time for more complex, interactive, teacher-guided tasks. This hybrid approach maximizes the value of both physical and virtual learning spaces. Finally, creating a supportive classroom culture is essential to mitigating anxiety. This involves normalizing mistakes as part of learning, using formative assessment rather than solely high-stakes testing, and designing activities that are genuinely engaging and relevant to students’ academic and professional futures, such as simulations of job interviews or professional presentations.

The challenge of developing spoken English proficiency among Bangladeshi tertiary students is significant, rooted in deep-seated pedagogical and structural issues. However, the solution lies in a concerted shift toward a more dynamic, student-centered approach to language teaching. By strategically implementing a diverse repertoire of interactive, monologic, and technology-assisted activities within a framework that consciously prioritizes and expands opportunities for speaking practice, educators can create a powerful engine for language acquisition. For Bangladesh, closing the communication gap is more than an educational objective; it is an economic necessity. Embracing this integrated approach is imperative to empower its graduates with the voice and confidence needed to compete and succeed on the global stage.

4.5 Gaps in research on activity-based learning and speaking hours

Neglecting research on activity-based learning and speaking hours significantly undermines language education in Bangladesh, leading to persistent deficiencies in students’ English-speaking skills (Subash and C, 2024). Despite over a decade of implementing Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), many students still struggle to construct coherent sentences, indicating a failure to practice speaking and listening in classrooms effectively (Roshid and Kankaanranta, 2025). Public universities often lack dedicated spoken English courses, exacerbating graduates’ communication challenges in the job market (Marzia and Ananna, 2017). Furthermore, psychological barriers, such as shyness and reliance on translating from Bangla, hinder learners’ ability to engage in English conversation (Hamid and Baldauf, 2008). The absence of targeted research limits the development of effective pedagogical strategies, perpetuating a cycle of inadequate language proficiency and diminishing employability for graduates (Chowdhury, 2024). Thus, addressing these gaps is crucial for enhancing overall language education and improving students’ communicative competence in Bangladesh (Mridula and Ahsan, 2025).

5 Theoretical framework

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) is a pedagogical approach that prioritizes interaction and communication in language learning, emphasizing the development of communicative proficiency over the mere mastery of linguistic structures. Key principles of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) include using authentic materials, active learning, and interaction facilitated by activities such as information gap, information transfer, and problem-solving tasks (Bai, 2024). CLT promotes student engagement in meaningful communication, necessitating comprehension and the appropriate use of linguistic forms, meanings, and functions within social contexts (Pemberton, 2024). In Communicative Language Teaching, teachers serve as facilitators who create contexts that enhance communication and guide students in negotiating meaning, thereby promoting a student-centered learning environment (Yang, 2024). This approach enhances students’ communicative competence and alleviates language anxiety, demonstrating its efficacy in fostering fluency, accuracy, and authentic communication (Fatima, 2024). CLT encounters challenges, including the absence of a comprehensive language learning theory and implementation difficulties, especially in environments dominated by traditional grammar-focused methods (Bai, 2024; Pemberton, 2024). Despite these challenges, Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) continues to exert significant influence in language instruction, providing practical guidance for educators seeking to improve learners’ communicative skills (Yang, 2024).

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) promotes interactive speaking activities and enhances speaking time by centring students in the learning process, thus creating an environment that supports active participation and communication. Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) prioritizes authentic communication situations, thereby improving students’ confidence and speaking proficiency, as evidenced in ESL contexts in Indonesia and EFL environments in Bangladesh (Aswad et al., 2024; Nisha, 2024). The participatory nature of CLT engages students in structured communication exercises, fostering collaboration and practical language use, essential for enhancing speaking skills (Aswad et al., 2024). In Bangladesh, CLT has significantly enhanced fluency and complexity in students’ speaking performance, with learners reporting favorable perceptions of its effectiveness (Nisha, 2024). Moreover, the emphasis of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) on student engagement and interaction is apparent in Arabic language acquisition, resulting in an 85% participation rate in discussions and conversations (Ariani and Karim, 2024). Challenges, including limited student interaction, concentration issues, and time constraints, have been identified. Teachers have implemented strategies such as discussions and homework to address these concerns (Nurdayani et al., 2024). Despite these challenges, the implementation of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) in various educational contexts, including private schools in Indonesia and Bangladesh, demonstrates its effectiveness in enhancing speaking skills through interactive activities. However, integrating technology and innovative methods, such as games, remains underutilized (Daar and Ndorang, 2020). CLT’s focus on communication and interaction enhances speaking opportunities and elevates language proficiency in various learning contexts.

6 Research questions

Based on the literature review, research gap, and theoretical framework, the following research questions have been formulated for this study.

1. Is there any significant difference between the impact of two different sets of spoken English classroom activities?

2. How does the variation in speaking hours affect the development of fluency in language learners?

3. What is the optimal combination of speaking activities and hours that maximizes fluency development?

7 Research method

This study employed a mixed-methods research design that encompassed an experimental research design to investigate the impact of activity types and speaking hours on the spoken English fluency of Bangladeshi tertiary students. Two distinct classes were analyzed: Class A, which engaged in interactive activities, such as role-plays and group discussions with 30 h of structured speaking practice, and Class B, which focused on monologic tasks, like presentations and storytelling with 20 h of speaking practice. This design was selected to isolate the effects of activity type (interactive vs. monologic) and speaking time (30 vs. 20 h) while controlling for extraneous variables, such as initial proficiency levels, instructional materials, and classroom environment. Both classes followed a 12-week intervention, integrating speaking sessions into their regular English curriculum.

The study was done using a quasi-experimental design using intact classes. This has some methodological limitations. Participants were not randomly divided into two groups, and the two groups simultaneously differed between interactive vs. monologic and practice duration (30 h. vs. 20 h). In this situation, activity type could contribute significantly to the results, but the practice duration and students’ interaction could be other variables associated with the findings.

7.1 Participants

The current study’s participants comprised 100 Bangladeshi tertiary students from two intact classes, matched for English proficiency, educational background, and socioeconomic status. A proficiency test aligned with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) determined proficiency levels, which were B2. Ethical considerations, including informed consent and confidentiality, were prioritized, and the study received approval from the institutional review board. To reduce variability associated with teaching, both classes were instructed by the same teacher trained in delivering both types of activities.

7.2 Data collection procedure

The data gathering utilized a mixed-methods strategy to ensure triangulation and enhance the dependability of the findings (Creswell and Clark, 2018). Fluency, accuracy, and pronunciation were evaluated by pre- and post-tests utilizing a standardized rubric modified from the IELTS speaking band descriptions (Dashti and Razmjoo, 2020). Two separate raters performed scoring, resulting in a high degree of inter-rater reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.89), deemed excellent (Creswell and Clark, 2018), signifying consistent scoring among raters. Furthermore, weekly classroom observations were conducted utilizing a validated engagement and interaction checklist to guarantee consistency in data documentation. Field notes from these meetings were examined to develop theme patterns that adhered to accepted qualitative coding methodologies (Daar and Ndorang, 2020). Additionally, surveys featuring Likert-scale items and semi-structured interviews with 10 randomly chosen students and instructors provided comprehensive insights into the perceived advantages and obstacles of the activities. The integration of standardized instruments, qualified evaluators, and methodological triangulation enhanced the overall reliability and trustworthiness of the study’s results.

7.3 Instruments

The independent variables were activity type (interactive/monologic) and speaking hours (30/20), while the dependent variable, spoken fluency, was operationalized through composite scores from the post-tests. Control variables included prior proficiency, teacher influence, and classroom dynamics. Quantitative data were analyzed using the Independent Samples T-test to compare post-intervention outcomes, with pre-test scores as covariates. Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.80, which indicates that the instruments’ reliability was at an acceptable level. This multi-faceted approach strengthened the validity and depth of the findings, ensuring a robust exploration of how pedagogical strategies and practice duration shape fluency development. Table 1 was the tool used in the study.

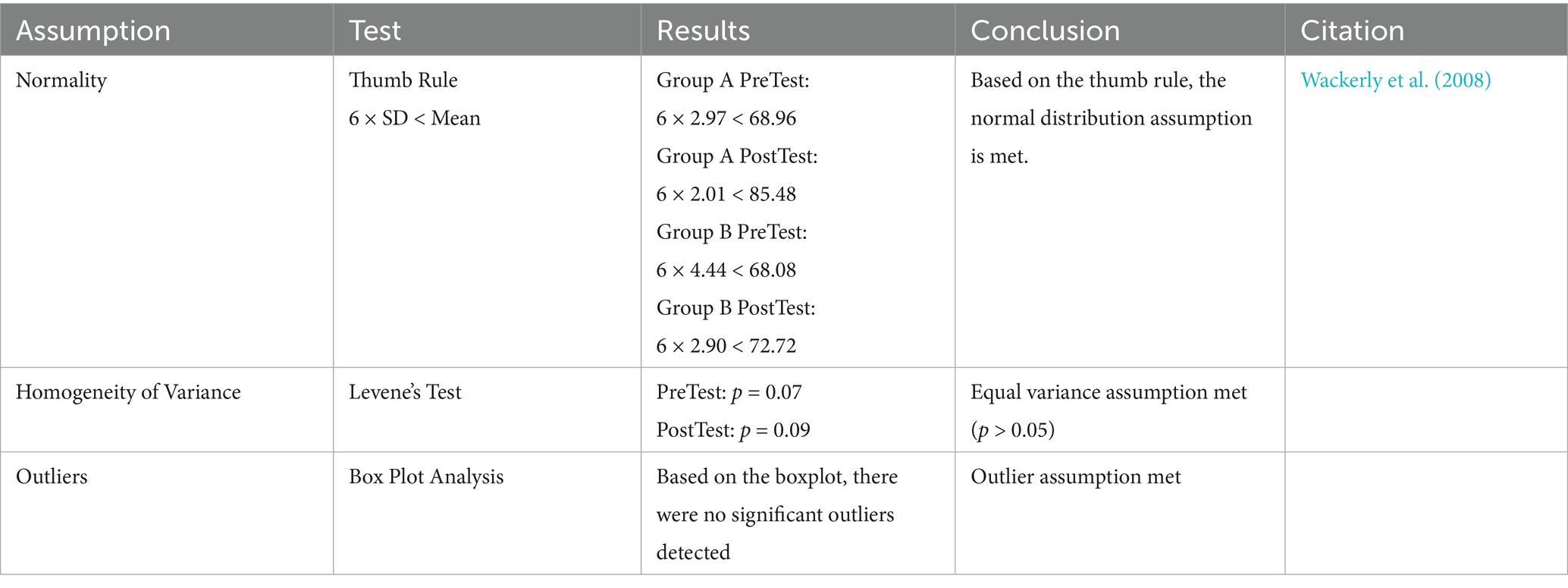

The above table demonstrates the construct-wise reliability values for the study. The values are higher than 0.75, representing a high level of internal consistency in the items of each construct. This also ensures the construct validity and content validity for the questionnaire used, as the questionnaire was reviewed and finalized under the supervision of 3 experts in the same field.

To establish construct validity and confirm that students distinguish between different aspects of speaking instruction, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted. The data with a sample size of 100 and an item ratio (16 items/100 = 1:6.25) provided sufficient evidence for factor analysis. The KMO test of sampling adequacy was found to be 0.819, and Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001), indicating the sample was adequate and variables are sufficiently correlated to meet the assumptions for factor analysis. The four factors were extracted, and the factors explained 55.79% of the total variance. The factor loadings with variance explained by the factors are presented below in Table 2.

The factor analysis with sufficient evidence of factor loadings in four factors demonstrated adequate contrast validity. The extracted four factors were: Core speaking development and confidence (with strong loadings from 0.609 to 0.825), activity-specific learning benefits, real-world application and engagement, and external practice and preferences. Cross-loadings were also present, but they are lower than primary loadings, suggesting acceptable discriminant validity.

7.4 Data analysis and results

At the beginning of the class, a pre-test or proficiency test was conducted to measure the proficiency level of both groups. The test result is presented below.

8 Findings and results

The study’s findings have been divided into two parts: quantitative and qualitative. Both findings are discussed below.

Research Question 1. Is there any significant difference between the impact of two different sets of spoken English classroom activities?

8.1 Pre-test or proficiency test

At the outset of the classes, a proficiency test was conducted to measure the proficiency level of both groups. The test results are analyzed below. Table 3 shows the group statistics of the proficiency test.

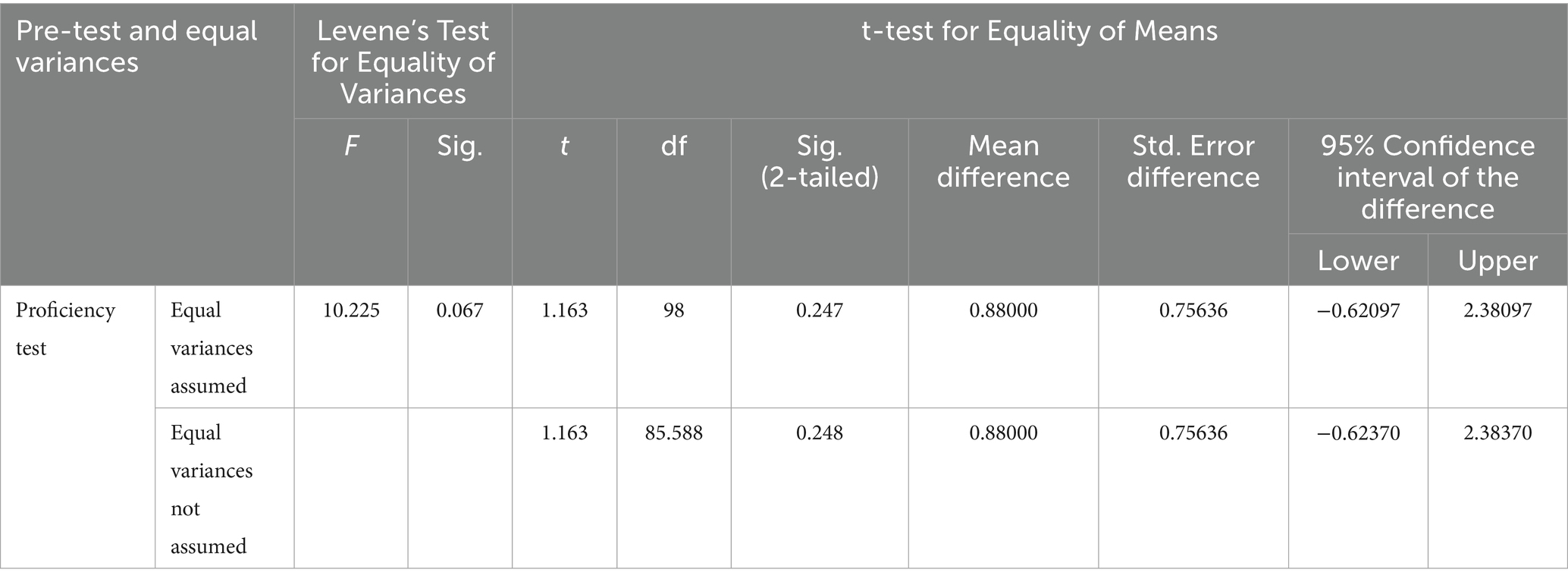

The data in Table 3 reveal similar proficiency levels for Group A and Group B, with no significant difference in their average scores. Group A (N = 50) exhibited a mean proficiency score of 68.96 (SD = 2.98), whereas Group B (N = 50) presented a mean score of 68.08 (SD 2.44). While Group A showed a marginally higher average proficiency, the mean difference of 0.88 points is minimal in practical terms, especially considering the overlapping variability indicated by the standard deviations and standard error values (Group A: SE = 0.42; Group B: SE = 0.63). The alignment in central tendency measures, along with the minimal effect size indicated by the mean difference in the variability, implies that the two groups exhibit statistical comparability in proficiency. The results highlight the group performance uniformity, suggesting that any noted differences are unlikely to indicate a significant variation in their proficiency levels. Additional inferential analyses, such as independent samples t-tests, would be necessary to validate the lack of statistically significant differences; however, the descriptive data alone do not substantiate a claim of divergence between the groups. Table 4 shows the scores of the independent samples test of the pre-test. This table represents research question one, which indicates the significant differences between the groups’ performances.

The independent samples t-test results demonstrate no statistically significant difference in proficiency levels between Group A and Group B, as the analyses did not reject the null hypothesis. The homogeneity of variances was not violated with p > 0.067. Both the equal variances (t(98) = 1.163, p = 0.247) and unequal variances (t(85.59) = 1.163, p = 0.248) analyses produced non-significant p-values that surpassed the conventional alpha threshold of 0.05. The mean difference of 0.88 points (95% CI: −0.62 to 2.38) supports this conclusion as the confidence interval encompasses zero, suggesting that the observed differences may result from random variation rather than a genuine effect. The minimal effect size, relative to the pooled variability (SE = 0.76), further supports the lack of practical significance. The findings indicate that the numerical differences in proficiency scores between the groups lack statistical importance, supporting the conclusion that Group A and Group B demonstrate similar proficiency levels. These findings answer Research Question 1.

8.2 Post-test

By the end of the semester, a post-test was conducted after interactive classroom activities, like debating, group discussion, TEDx talks, and showing other videos on speeches, motivation, and self-confidence. The test aimed to measure the development and improvement of speaking skills. Table 5 shows the group statistics of the post-test.

Table 5 also answers Research Question 1. The group statistics reveal a significant disparity in post-test performance between Group A and Group B. Group A attained a mean score of 85.48 (SD = 2.01), which is significantly higher than Group B’s mean score of 72.72 (SD = 2.91), resulting in a mean difference of 12.76 points. The low standard error values for both groups (Group A: 0.28, Group B: 0.41) indicate a precise estimation of the mean scores. The significant disparity indicates that Group A surpassed Group B in the post-test, suggesting a notable difference in proficiency levels between the groups. Table 6 shows the scores of the independent samples test of the post-test.

The independent samples t-test results indicated a statistically significant difference in spoken English proficiency levels between the two groups. The t-test results in t(87.20) = 25.52, (p < 0.001) indicated a significant mean difference of 12.76 (95% CI [11.77, 13.75]), with the experimental group exceeding the control group substantially. The null hypothesis, which posits no difference in proficiency levels, was rejected with high statistical significance (p < 0.001), suggesting that the observed disparity is improbable to have arisen by chance. The narrow confidence interval, excluding zero, strengthens the validity of this finding. This rejection indicates that the intervention or group characteristics under examination (such as debating, group discussion, TEDx talks, and showing other videos on speeches, motivation, and self-confidence) significantly influenced spoken English proficiency. The effect size, derived from the magnitude of the mean difference and its stability within the confidence interval, highlights the practical significance of this finding in real-world language acquisition scenarios (Tables 7, 8).

So, the previous findings show that, though initially, both groups had no significant difference in their proficiency level, after the implementation of interactive classroom activities and an increase in the speaking time, the experimental group’s performance was promising. It was found that the activity types and speaking can create notable differences in the speaking fluency of the groups. This can be explained by the following tests of Mix-Design ANOVA.

This mixed-design ANOVA found a significant result and main effect for Time with F(1, 98) = 489.285, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.833, and Group F(1, 98) = 255.173, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.723. This indicates that there was a substantial improvement in English fluency scores in the posttest from the pre-test of the students. Moreover, the Time × Group Interaction is significant as we have F(1,98) = 154.228, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.611, representing that the two groups are significantly different in the score pattern changes over time. Group A significantly demonstrated greater improvement in fluency scores as compared to group B. There is a high gain score and large effect size with Cohen’s d = 4.783, 95% CI [−3.00, −1.95]. This demonstrates that the change pattern is large.

Research Question 2. How does the variation in speaking hours affect the development of fluency in language learners?

This was divided into two parts, one from the students’ points of view, collecting the data through a questionnaire, and findings from both students and teachers from their interviews. Findings from the students who participated in the classroom activities also took part in the questionnaire to give their opinions. The questionnaire was divided into four parts: demographic information, perceived fluency development in speaking, the effectiveness of interactive versus monolithic classroom activities, speaking hours and practices, and overall engagement. So, the questionnaire was analyzed into four parts, which are presented below.

8.3 Demographic information

Information about the participants is given below. Table 9 demonstrates demographic profile information of the participants.

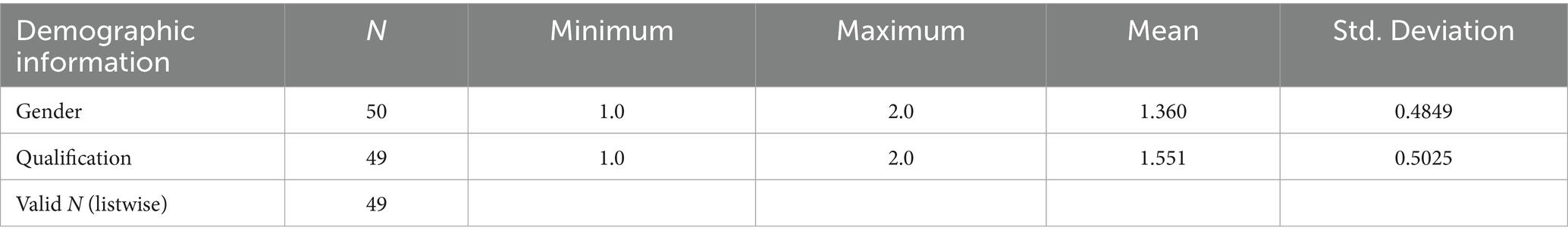

The demographic data includes 50 participants for gender and 49 individuals for qualifications. Gender was assigned a value of 1 for males and 2 for females, yielding a mean of 1.36 (SD = 0.4849), suggesting that most participants were male. Qualification was assigned a value of 1 for the intermediate level and 2 for the tertiary level, yielding a mean of 1.551 (SD = 0.5025), indicating a predominance of university-level qualifications. The total number of valid cases for listwise analysis was 49, due to missing data.

8.3.1 Perceived fluency development in speaking

The descriptive statistics illustrate students’ perceived enhancements in spoken English fluency after classroom activities. Table 10 shows the students’ perceived enhancements in spoken English fluency.

Table 10 represent the answer to Research Question 2. The statement, “The activities in class improved my confidence in speaking English,” received a mean score of 1.460 (SD = 0.5425), suggesting that most respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that classroom activities effectively enhanced their confidence in speaking English. This indicates a notable positive effect of the activities on students’ self-confidence. The statement, “I feel more comfortable participating in English conversations now,” yielded a mean score of 1.740 (SD = 0.6328), indicating that most students concurred with feeling more at ease in English conversations. This shows a general rise in comfort levels, probably resulting from the practice and support offered during classroom activities.

The statement, “My vocabulary and grammar have improved through speaking practice,” produced a mean of 1.660 (SD = 0.5928), suggesting that speaking practice in class positively impacts vocabulary and grammar development. Most respondents concurred that their language skills in these areas had enhanced due to the activities.

The mean score for the statement “My pronunciation has become clearer and more natural” was 1.880 (SD = 0.9179). This indicates that most students acknowledged improved pronunciation; however, the broader range of responses suggests variability in individual progress. In conclusion, “I can speak for more extended periods without frequent pauses “yielded a mean score of 2.040 (SD = 0.8562). This suggests that many students could speak for extended periods without frequent interruptions, although opinions varied, potentially indicating differing levels of comfort or fluency in speaking. The findings indicate that classroom activities significantly enhanced students’ confidence, comfort, vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and speaking duration. The variation in responses, especially in pronunciation and extended speaking, suggests that the impact may differ based on individual factors like experience and confidence.

8.3.2 Interactive versus monolithic activities

The descriptive statistics allow for an analysis of interactive effectiveness compared to monologic classroom activities. Table 11 shows descriptive statistics of interactive vs. monolithic classroom activities.

8.3.3 Effectiveness of interactive and monologic activities

As shown in Table 11, the findings indicate that students perceived interactive classroom activities (M = 1.56, SD = 0.6115) and encouraging activities (M = 1.62, SD = 0.6354) as somewhat beneficial as their mean scores are situated near the lower end of the Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). This indicates that students did not express significant disagreement regarding their effectiveness.

In contrast, monologic classroom activities achieved a higher mean score (M = 3.14, SD = 1.3554), suggesting a more neutral or slightly positive perception. This indicates that although students did not wholly dismiss monologic methods, they perceived them as less effective than interactive activities.

8.3.4 Anxiety and stress levels

As shown in Table 11, students exhibited moderate levels of anxiety or stress during activities (M = 2.76, SD = 1.1704). As this item is reverse-coded, elevated scores reflect increased anxiety levels. This indicates that students likely experienced greater pressure during monologic activities, such as presentations and storytelling, than during interactive activities.

8.3.5 Real-world communication and feedback

As shown in Table 11, interactive activities demonstrated greater effectiveness in reflecting real-life communication (M = 1.78, SD = 0.5817), suggesting that students perceived them as more relevant to real-world contexts. Furthermore, feedback proved beneficial (M = 1.76, SD = 0.5555), underscoring the significance of peer and instructor support in interactive environments.

Interactive activities demonstrate greater effectiveness than monologic activities as evidenced by lower mean scores, indicating higher agreement with positive statements. Students exhibited increased engagement, perceived that those activities reflected real-life communication, and gained advantages from feedback. Monologic activities retained some value, though they were associated with heightened anxiety and stress levels.

Research Question 3. What is the optimal combination of speaking activities and hours that maximizes fluency development?

8.4 Speaking hours and practice

The descriptive statistics indicate that speaking hours’ influence on speaking skills can be assessed using the measured variables’ mean values and standard deviations. Table 12 shows descriptive statistics of speaking hours and participants’ activities.

In response to research question 3, in Table 12, the average number of speaking hours was 2.000 (SD = 0.7559) on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This indicates that, on average, participants were marginally indifferent to or in agreement with the duration of their speaking hours. Likewise, the mean for further speaking practice was 1.600 (SD = 0.5345), suggesting a general disagreement or weak agreement for supplementary speaking opportunities. On the other hand, the impact of activities on speaking skills was assessed marginally higher, with a mean of 2.260 (SD = 0.8526), indicating that participants recognized a modest, nevertheless favorable influence of diverse activities on their speaking proficiency.

The data indicate that speaking hours and supplementary speaking practice were not significantly utilized, possibly constraining the overall advancement of speaking skills. The scale’s maximum of 5 indicates that the comparatively low averages suggest participants did not firmly concur that they had adequate speaking practice or that the activities substantially impacted their speaking abilities. The moderate standard deviations suggest reaction variability, indicating that individual experiences may have varied. More scheduled speaking hours and supplementary practice sessions should be implemented to enhance speaking skills. Augmenting the impact of programs via interactive and immersive techniques may further enhance participants’ speaking skills. So, all these discussions represent Research Question 3.

8.4.1 Overall engagement

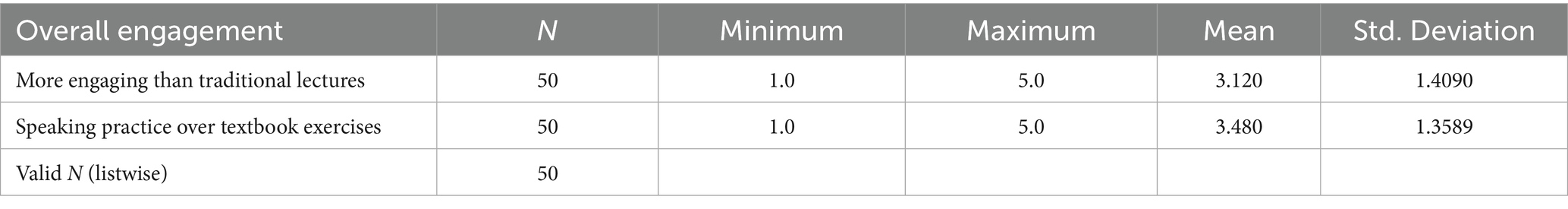

The descriptive data indicate moderate participation in interactive activities. Table 13 shows the statistics of the overall engagement of the participants.

Table 13 also represents Research Question 3. The assertion “more engaging than traditional lectures” yielded a mean score of 3.12 (SD = 1.409), whilst “speaking practice over textbook exercises” attained a marginally superior mean of 3.48 (SD = 1.3589). According to the Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), the results reveal that students, on average, tended toward agreement, implying that they perceived the activities as engaging. The elevated standard deviations indicate variety in responses, suggesting that while some students perceived the activities as enjoyable, others had contrasting views. The data suggest that numerous students regarded interactive methods, especially speaking practice, as advantageous compared to textbook exercises. The overall findings are that interactive activities in the classroom and an increase in speaking hours have a tremendous impact on the fluency of the students. These activities provide them with confidence and motivation that lead to the individual student’s ultimate performance.

8.5 Perception of students about the activity types and their effectiveness

The findings below also answer Research Question 3. According to the students, as it was found from their interviews, Tasks like role-plays, group discussions, TEDx talks, debates, and presentations played a crucial role in helping them overcome the fear of speaking English and increasing their eagerness to communicate well. Practicing these tasks in class boosted their confidence and enabled them to communicate their thoughts more efficiently. When they present and incorporate personal experiences, not only do they become more fluent, but they also automatically develop a good word flow. These assist in improving their communication skills, allowing them to become more confident and comfortable with English. These types of exercises help them a lot in developing their speaking. They help them identify different words, strengthen their vocabulary, and learn how to express their thoughts fluently. These activities boosted their confidence, improved their expression, and made communicating in English more natural and enjoyable.

The students also identified the sharp differences. They feel more confident when they give a presentation because they have practiced and know what to say next. They could speak more smoothly because they had prepared their words before. However, in a discussion, they had to think and respond quickly; it sometimes made them pause or struggle to find the right words, so they might not speak as smoothly as they do in a presentation. Overall, they feel more comfortable when they rehearse, but discussions help them improve their ability to think and speak instantly. Presentations or discussions also improve our fluency in English. Explaining a point to someone or expressing their point of view in front of someone helped them speak more fluently. Presentations help them overcome their fear of speaking. Some opined that presentations were more straightforward because they could prepare, but discussions were more challenging since they had to think and talk quickly. This is how they found the sharp differences between interactive and monolithic activities. They also opined that their teacher emphasized preparing the lecture slides from the prescribed books and internet sources. Everyone had to present a topic related to the public speaking course pertaining to the rules, regulations, tips, and tricks of public speaking. This compelled them to read the books and, at the same time, get them ready for public speaking. The teacher knew very well that reading books regarding public speaking while practicing in class would not produce fruitful results. Some also said that motivational videos helped them speak confidently as confidence was the key to overcoming their English phobia.

Another student expressed her observation and experience that she noticed a difference in his fluency between rehearsed tasks, such as presentations, and spontaneous interactions, like discussions. In rehearsed tasks, he had time to prepare, organize her thoughts, and practice her delivery, which made her speech more structured and confident. However, she had to think and respond quickly in spontaneous interactions, sometimes leading to pauses or minor mistakes. Despite this, engaging in discussions helped her develop her ability to think on his feet and express herself more naturally over time. Both types of tasks played a crucial role in improving her fluency in English. The students provided the subsequent observations concerning the allocation of time: The duration of speaking time influences advancement. Extended time facilitates greater expression, whereas limited time compels precision and conciseness in communication. They deemed the speaking time generally adequate, as it facilitated practice and enhanced their fluency; however, more frequent practice would further bolster their confidence. Consistent practice is beneficial, and it was recommended that a minimum of 30–40 min every day would be advantageous. “Speaking time helped me a lot,” one student stated, “If time was short, I could not practice much or feel confident. But when I had enough time, I could speak more, fix my mistakes, and get better. Sometimes it felt long, but it was good for learning.” Adequate and balanced speaking time facilitated his gradual enhancement of English proficiency.

Regarding challenges and overcoming those, they found that sometimes they could not find the right words to express themselves, which made it hard to speak. However, they have learned to talk instantly without long pauses by participating in everyday class activities. Day by day, these activities helped them become more fluent speakers and express themselves better. One of them said the most challenging part was finding proper words between the speeches. Then, he tried calming down and thinking, which helped him recall words. Also, sometimes, he felt blank whenever he tried to talk in front of so many people. That time, he just closed his eyes and tried to think that there was no one else except him, which immensely helped him. They faced challenges like nervousness and finding the right words quickly. However, they overcame them by practicing more, listening to others, and staying confident. They found that they stuck a lot, so they kept listening and practicing. During the activities, they faced several challenges, such as nervousness, difficulty finding the right words, and fear of making mistakes. In spontaneous discussions, they sometimes struggled to organize my thoughts quickly. Maintaining fluency and confidence in front of an audience in debates and presentations was challenging. To overcome these, they practiced regularly, expanded their vocabulary, and engaged in more conversations to build confidence. They also learned to embrace mistakes as part of the learning process, which helped them improve gradually. Seeking feedback from peers and instructors further enhanced their speaking skills.

Concerning the peer activities, they asserted that peer interactions significantly benefited them. For instance, addressing their peers’ inquiries and elucidating concepts enhanced their confidence. “When I elucidated a topic to my friend and observed his comprehension, I felt as though I possessed significant knowledge,” one pupil conveyed. “It instilled a sense of pride in me and bolstered my confidence to participate more actively in class.” These contacts facilitated his comfort, enabling him to surmount his anxiety of public speaking progressively. Peer interactions during activities are constructive because they help to make the speech more engaging, dynamic, and effective. For example, when they engage with the audience, they stay connected to others, and it is also the easiest way to keep their concentration on the activities. This helps both the speaker and the audience as the audience understands the speech, and the speaker’s confidence level also increases. Talking and working with peers can boost confidence. For example, sharing ideas in group discussions or working together on projects makes you feel more capable. Positive feedback from peers also helps them feel more confident. They said peer interactions significantly boosted their confidence regarding role-playing and other interactive activities. Group discussions and debates allowed them to express their thoughts freely while receiving constructive feedback from their peers. For example, during role-plays, their partners encouraged them when they hesitated, making them feel more comfortable speaking English. Their classmates’ supportive nods and positive feedback motivated them to communicate more confidently in presentations. These interactions created a friendly and encouraging environment, helping them overcome their fear of making mistakes and improving their fluency.

8.6 Perception of teachers about the activity types and their effectiveness

Students also said that group activities like role plays, group discussions, TEDx talks, debates, and presentations were of prime importance in helping students overcome their fear of speaking in English. These activities gave students confidence, fluency, and capital in expressing their thoughts. Moreover, their words’ flow and natural expression were improved by adding a personal feel to their presentations. Educators reported that those exercises gave students practice using new vocabulary and increased fluency. Teachers recognized the contrast between practice-based presentations and flourishing conversations. Organizing presentations beforehand gave students the time to prepare, making them perform more confidently. But spontaneous discussions put them on the spot to think on their feet and answer on the spot, sometimes causing them to hesitate. Whereas prepared speeches made students comfortable at the podium, as several teachers argued, discussions were critical for learning how to communicate in the real world.

Teachers employed a balanced methodology, requiring students to engage with a diverse array of contemporary prescribed texts and online materials while also practicing verbal communication. Students were invited to suggest subjects related to public speaking, encompassing rules, procedures, and strategies. They believed that merely reading about public speaking was insufficient; genuine improvement resulted from consistent speaking practice in class. “I have observed reticent students gradually emerge from their shells,” another teacher remarked. “Regular communication in a supportive environment visibly enhances their confidence, facilitating genuine learning.” They also incorporated motivational movies to enhance pupils’ self-esteem and alleviate their anxiety. Teachers noticed that the more they spoke, the less fluent and confident their students were. They advised 20–30 min of speaking practice daily, a mixture of prepared talks and free conversation. Not enough practice hindered improvement, and too much speaking time would overwhelm students. The routine and adequate speaking practice allowed learners to sharpen their skills, correct errors, and build confidence gradually. Educators acknowledged students’ everyday challenges, such as not always finding the right words, anxiety, and fear of making mistakes. They added that students improved gradually through practice and exposure to conversations in real time and through a supportive class environment. Teachers advised students to stay calm when they could not remember a word and to regard mistakes as a way to learn. Their advances were further augmented by feedback from both instructors and their peers.

The teachers must still believe in the value of peer activity in language. They observed that students’ confidence was higher when engaging in discussions, debates, and group projects with peers. Peering into others’ answers, explaining ideas, and confirming their results created a collegial environment. Such strategies as role-plays and group activities allowed students to speak in a low-risk setting, making public speaking more comfortable and fun. In general, teachers noted that a mix of presentations, structured and spontaneous, interactions with peers, and practice speaking time was crucial for helping improve students’ fluency in English. Their motto was that an uplifting and engaging classroom enhanced their students’ confidence and communication skills.

9 Discussion

This study suggests that various forms of spoken English classroom activities have differing effects on fluency development, with communicative and task-based activities demonstrating significantly more efficacy than controlled, form-focused exercises. Augmented speaking hours significantly affect fluency, especially when the practice is engaging, meaning-oriented, and consistently spaced throughout time. Investigations into the correlation among activity categories, speaking hours, and spoken English fluency in Bangladeshi tertiary education expose numerous discrepancies and limitations (Akanda and Marzan, 2023). A significant paradox exists in the focus on fluency as either a static or dynamic construct. Traditional research often assesses fluency using static metrics such as syllables per minute; however, current studies advocate for a dynamic perspective, proposing that fluency be regarded as a potential variable construct affected by multiple elements throughout task execution (de Jong, 2023). This dynamic perspective is not commonly embraced in Bangladeshi contexts, where fluency is frequently evaluated by static measures, resulting in possible misinterpretations of proficiency levels (Mridula and Ahsan, 2025). The insufficient focus on speaking and listening skills within the curriculum, evidenced by their disregard in classroom practices despite being present in textbooks, exacerbates the challenge of achieving fluency (Uddin and Reza, 2024). Socio-economic and cultural factors were promising to influence fluency development among students, since discrepancies in resource access and exposure to English outside the classroom produce unequal possibilities (Rana, 2024). Furthermore, the classroom setting imposes constraints, since professors frequently dominate verbal exchanges and utilize the native language, thereby limiting students’ possibilities to engage in speaking practice (Islam and Stapa, 2021). The interplay of these elements, along with inadequate educational practices and insufficient teacher preparation, obstructs the realization of fluency in practical contexts (Islam et al., 2022). The meta-analysis of fluency-proficiency relationships complicates the situation by demonstrating that distinct dimensions of fluency, such as speed and breakdown, possess differing predictive capabilities for proficiency, which are not consistently acknowledged in Bangladeshi educational contexts (Yan et al., 2025). These contradictions and restrictions underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding of fluency that incorporates dynamic evaluation techniques, refined instructional strategies, and equitable access to language learning resources.

The investigation into ideal combinations of speaking activities and durations to enhance fluency development reveals both complementary and potentially conflicting results across the examined studies. The research by Shang-En Huang and Yeu Ting Liu highlights the effectiveness of soliloquizing, especially under escalating time pressures, in improving EFL learners’ speaking fluency and attitudes (Huang and Liu, 2023). This indicates that a systematic, self-guided methodology may be advantageous. Xinyu Zuo emphasizes the considerable influence of interactive, activity-oriented pedagogical methods, including role-playing and group discussions, in both classroom and extracurricular contexts, promoting a more social and collaborative learning atmosphere to enhance speaking skills (Zuo, 2024). Karen Lichtman’s study reveals that implicit instruction can enhance fluency more effectively than explicit instruction, especially when learning an artificial mini language, suggesting that the type of instruction (implicit versus explicit) has a significant influence on fluency development (Lichtman, 2021). Feisal Aziez et al. examine the reduction of silent pauses as an indicator of fluency enhancement, asserting that structured speaking exercises can significantly increase fluency, but they observe negligible alteration in the utilization of pause fillers (Aziez et al., 2024). The findings indicate that structured, self-directed activities such as soliloquizing and implicit instruction can improve fluency, while interactive and cooperative activities are also essential, suggesting the necessity for a balanced approach that integrates both individual and social learning experiences to maximize fluency development.

10 Conclusion

According to the data obtained from both students and teachers, interactive speaking activities (like role plays, discussions, presentations, and debates) play a critical role in building students’ confidence, fluency, and overall communication ability in English. Organized presentations enable students to prepare and speak confidently, whereas impromptu discussions challenge them to think quickly, improving their skills to reply instantly. Both teachers and students acknowledge that regular practice, enough speaking time, and peer interactions create a supportive and engaging learning environment.

11 Limitations of the study

The study’s limitations are that some students may still have difficulty with nervousness while speaking, retrieving vocabulary during spontaneous speaking, and with fluency. Limitations include sample size and duration of study, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies to explore long-term effects. The comfort zone that prepared presentations need to be out of the picture and does not always help in verbalizing ideas in real-time conversations. Moreover, differences in individual learning paces mean that some students may take longer to learn new information and need more structured guidance and personalized feedback than others. Classroom constraints often make it challenging to pursue such practice in depth. Future studies may investigate the long-term effects of these activities and find more individualized solutions to support students who find spoken English challenging to engage with. After all, interaction and a supportive learning environment have a lasting impact on students’ speaking ability.

Due to our research design limitations such as quasi experimental design with non-random sample selection and simultaneous variation of activity type and practice hours, while the results showed a strong association between the combined intervention (interactive activities extended practice) and fluency improvement, there is a need for further research studies with control designs, such as 2 × 2 factorial design. The substantial effect sizes (ηp2 = 0.611 for the interaction) suggest meaningful practical differences, but the confounding necessitates cautious interpretation regarding the specific mechanisms driving these improvements.

12 Pedagogical implications

The results have many implications for teaching and learning—Scaffold with both prepared and impromptu speaking tasks for structured speech and quick spoken composition. We share the power of constructive feedback and motivational resources and encourage peer collaboration to help students build confidence. Schools or institutions should provide enough time for people to practice speaking gradually. The study could be crucial as it offers evidence-based recommendations for designing spoken English curricula and implications for curriculum consideration and modification, ensuring that teaching approaches are specifically targeted to promote fluency efficiently. The study analyzes the impact of various activity types and speaking hours on students’ spoken English competency, providing actionable recommendations for enhancing language instruction in Bangladeshi higher education. Moreover, its findings enhance the broader domain of English language instruction, especially in circumstances akin to Bangladesh, where English is taught as a foreign language. This research tackles local educational obstacles and offers a framework adaptable to other places with similar linguistic and pedagogical issues, thus enhancing global comprehension of effective spoken English teaching practices.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MHaq: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MHas: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NM: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Partial publication grant was received from the Institute for Advanced Research Publication Grant of United International University, for the publication of this article. Ref. No.: IAR-2025-Pub-086.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akanda, F., and Marzan, L. A. (2023). Extra-linguistic factors affecting learner’s English speaking at the tertiary level in Bangladesh. IUBAT Rev. 6, 92–105. doi: 10.3329/iubatr.v6i2.71310

Akbaraliyevna, A. S. (2023). Studies on fluency and interaction in developing the students’ speaking skill. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Educ. 2, 06–09. doi: 10.22161/ijtle.2.1.3

Akter, A. (2022). Approaches to speaking: challenges in organizing classroom discussion and possible solutions. Green Univ. Rev. Soc. Sci. 7, 155–164. doi: 10.3329/gurss.v7i1-2.62691

Andreas, A., Urai, S., and Iwan, S. (2023). Improving students’ ability in speaking through role play technique. J. Sci. Res. Educ. Technol. (JSRET) 2, 1009–1015. doi: 10.58526/jsret.v2i3.188

Arefin, S., Khan, M. B., Rahman, M. M., Uddin, M. J., Emon, A. I., and Ahmed, M. K. (2024). Obstacles in instructing English at village elementary schools in Bangladesh: a study and proposals. Int. J. Linguist. Lit. Transl. 7, 129–136. doi: 10.32996/ijllt.2024.7.11.14

Ariani, A., and Karim, P. (2024). Analysis of student activity in the learning process using the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) method. J. Pedagogi 1, 89–98.

Asmae, A., and Sana, S. (2024). The importance of listening and speaking in a successful English language acquisition in classrooms: Moroccan EFL classrooms as a case study. J. English Lang. Teach. Appl. Ling. 6, 01–05. doi: 10.32996/jeltal.2024.6.3.1

Aswad, M., Putri, A. M. J., and Sudewi, P. W. (2024). Enhancing student learning outcomes through the communicative language teaching approach. Al-Ishlah J. Pendidik. 16, 5313–5324. doi: 10.35445/alishlah.v16i4.5204

Azam, A. S. M. (2024). The role of pairwork in enhancing speaking skills and learner autonomy among Bangladeshi tertiary level students. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Stud. 6, 61–69. doi: 10.32996/ijels.2024.6.3.9

Aziez, F., Nita, A., Istikharoh, L., and Sotlikova, R. (2024). Analyzing the development of university English students’ speaking fluency. Journal of English and Education (JEE) 10, 111–136. doi: 10.20885/jee.v10i2.36345

Bai, J. (2024). The discussion of communicative language teaching in language classrooms. Front. Sustain. Dev. 4, 1–4. doi: 10.54691/jckqrt49

Baldwin, J., Manning, J., Powell, N., and Martinez, P. (2022). Efficacy of unguided conversation on fluency and speaking confidence: a case study in South Korea. Modern J. Stud. English Lang. Teach. Lit. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.56498/41202241

Barat, M. I., and Talukder, M. J. (2023). Exploring the impact of English language proficiency on business communication effectiveness: a comprehensive research analysis. Int. J. Multidis. Res. 5, 1–11. doi: 10.36948/ijfmr.2023.v05i06.8809

Bularafa, M. W., Mustapha, M. A., Saidu, Z., and Shehu, M. (2024). Effect of interactive approach on students speaking skill in English language in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno state of Nigeria. NIU J. Human. 9, 123–128. doi: 10.58709/niujhu.v9i4.2057

Chowdhury, K. (2024). Impediments of speaking English in EFL classroom: a case study on undergraduate level in Bangladesh. Int. J. English Lang. Teach. 12, 66–81. doi: 10.37745/ijelt.13/vol12n26681

Cismas, S. C. (2016). Education catering for professionals’ communication needs on the global labour market. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, 202–207. doi: 10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.26

Coutinho dos Santos, J. (2022). Improving speaking fluency through 4/3/2 technique and self-assessment. Teach. English Second Foreign Lang. TESL-EJ 26, 1–14. doi: 10.55593/ej.26102a1

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Daar, G. F., and Ndorang, T. A. (2020). Analysis the implementation of communicative language teaching and classroom interaction in the effort to increase learners’ speaking skills. Int. J. Educ. Voc. Stud. 2, 969–978. doi: 10.29103/ijevs.v2i12.2969

Dashti, L., and Razmjoo, S. A. (2020). An examination of IELTS candidates’ performances at different band scores of the speaking test: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Cogent Educ. 7. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1770936

de Jong, H. N. (2023). Fluency in speaking as a dynamic construct. Lang. Teach. Res. Q. 37, 179–187. doi: 10.32038/ltrq.2023.37.09

Fatima, D. N. (2024). Role of communicative language teaching approaches in strengthening English language speaking skills in ESL learners. Migr. Lett. 21, 1336–1346. doi: 10.59670/ml.v21iS8.10276

Hamid, M. O., and Baldauf, R. B. (2008). Will CLT bail out the bogged down ELT in Bangladesh? Engl. Today 24, 16–24. doi: 10.1017/S0266078408000254

Han, H., Islam, M. H., and Ferdiyanto, F. (2023). An analysis of student’s difficulties in English speaking, a descriptive study. EDUTEC J. Educ. Technol. 6, 497–503. doi: 10.29062/edu.v6i4.579

Hasan, M. J. (2021). Role of classroom interaction in English language learning: a study on tertiary level teachers and students in Dhaka Md. Jahid Hasan. J. Inst. Modern Lang. 32, 221–257. doi: 10.59191/JIMLV32A8

Hasan, M. J., Miah, M. J., and Hoque, M. T. (2024). Exploring English speaking problems of secondary school students in Bangladesh. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 72–93. doi: 10.37745/ijelt.13/vol12n57293

Hasan, M. K., and Shabdin, A. A. (2017). The relationship of sub-components of manifold dimensions of vocabulary depth knowledge and academic reading comprehension among English as a foreign language learners at tertiary level. J. Pan-Pac. Assoc. Appl. Linguist. 21, 85–114.

Hoa, M. A. L. T. (2023). A study on the effect of technology in enhancing spoken language proficiency. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Human Res. 6, 6691–6698. doi: 10.47191/ijsshr/v6-i11-15

Hossain, M. M. (2022). Exploring students’ problems to interact in English language in the classroom at tertiary level education in rural areas of Bangladesh. Int. J. Lang. Lit. Transl. 5, 12–27. doi: 10.36777/ijollt2022.5.2.055

Huang, S.-E., and Liu, Y.-T. (2023). How to talk to myself: optimal implementation for developing fluency in EFL speaking through soliloquizing. Engl. Teach. Learn. 47, 145–169. doi: 10.1007/s42321-022-00110-z

Islam, M. T., Ramalingam, S., and Hoque, K. E. (2022). English language proficiency hegemony in career building among diverse groups of Bangladeshi graduates. Shanlax Int. J. English 11, –12. doi: 10.34293/english.v11i1.5791

Islam, M. S., and Stapa, M. B. (2021). Students’ low proficiency in spoken English in private universities in Bangladesh: reasons and remedies. Lang. Test. Asia 11:22. doi: 10.1186/s40468-021-00139-0

Kahng, J. (2024). Longitudinal development of second language utterance fluency, cognitive fluency, and their relationship. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 46, 535–549. doi: 10.1017/S0272263123000591

Karpovich, I., Sheredekina, O., Krepkaia, T., and Voronova, L. (2021). The use of monologue speaking tasks to improve first-year students’ English-speaking skills. Educ. Sci. 11:298. doi: 10.3390/educsci11060298

Kayum, M. A., and Ahamed, F. (2024). Developing oral communication skill in Bangladesh. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 13, 3153–3159. doi: 10.30574/ijsra.2024.13.1.2027

Lichtman, K. (2021). What about fluency? Implicit vs. explicit training affects artificial mini-language production. Appl. Linguist. 42, 668–691. doi: 10.1093/applin/amaa054

Lopez, J. I., Becerra, A. P., and Ramirez-Avila, M. R. (2021). EFL speaking fluency through authentic oral production. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Learn. 6, 37–55. doi: 10.18196/ftl.v6i1.10175

López-Carril, S., Rodríguez-García, M., and Mas-Tur, A. (2024). TED talks and entrepreneurial intention in higher education: a fsQCA approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 22:100980. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2024.100980

Ma, Q., Mei, F., and Qian, B. (2024). Exploring EFL students’ pronunciation learning supported by corpus-based language pedagogy. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn., 1–27. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2024.2432965

Mahmood, I., Memon, S. S., and Qureshi, S. (2023). An action research to improve speaking skills of English language learners through technology mediated language learning. Acad. Educ. Soc. Sci. Rev. 3, 429–439. doi: 10.48112/aessr.v3i4.633

Marzia, R., and Ananna, D. (2017). Graduates’ employability and importance of communication skills. DIU J. Bus. Entrepr. 11, 102–108. doi: 10.36481/diujbe.v011i1.r1zan105

Marzuki, D. (2023). The development of EFL students’ speech fluency. AILA Rev. 36, 112–133. doi: 10.1075/aila.22027.mar

Mohanapriya,, and Jaisre, V. (2024). The role of classroom interactions in enhancing speaking skills in English. Integr. J. Res. Arts Human. 4, 201–204. doi: 10.55544/ijrah.4.6.19

Mridha, M. M., and Muniruzzaman, M. S. (2020). Developing English speaking skills: barriers faced by the Bangladeshi EFL learners. Englisia J. Lang. Educ. Human. 7:118. doi: 10.22373/ej.v7i2.6257

Mridula, K. A., and Ahsan, W. (2025). Bridging the English proficiency gap: the higher education challenges of Bangla-medium students in Bangladesh. Userhub J. doi: 10.58947/journal.svfz89

Nagmoti, J. (2020). “Communication in large classrooms: issues, challenges, and solutions” in Effective medical communication (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 111–122.

Nisha, P. R. (2024). Communicative language teaching (CLT) in improving speaking skills of tertiary level EFL students of Bangladesh. FOSTER J. English Lang. Teach. 5, 120–130. doi: 10.24256/foster-jelt.v5i2.174

Nurdayani, A., Sakina, R., and Syaepul Uyun, A. (2024). Use of communicative language teaching (CLT) approach in teaching speaking skill. Biormatika: Jurnal Ilmiah Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu Pendidikan 10, 43–58. doi: 10.35569/biormatika.v10i1.1809