- 1Department of Pedagogy and Psychology, Alikhan Bokeikhan University, Semey, Kazakhstan

- 2Department of Pedagogy, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, Kazakhstan

- 3Department of Art, Shakarim University of Semey, Semey, Kazakhstan

- 4Department of Chemistry and Biology, Shakarim University of Semey, Semey, Kazakhstan

Background: While the interplay between teacher self-efficacy and resilience is established, this study probes the nuanced influence of specific demographic factors – gender, teaching experience, and familial ties to teaching – on this dynamic within inclusive education contexts. Existing research presents equivocal evidence regarding gender’s role and sparse insight into the impact of familial connections to teaching on these constructs. This investigation replicates and extends prior inquiry by Yada et al. (2021) in a distinct socio-cultural setting, utilizing a larger cohort of pre-service teachers (n = 283 vs. 150 in the original study) and incorporating qualitative insights to enrich quantitative finding. This replication is crucial as it examines how demographic predictors, which have shown context-dependent effects in prior research, operate within a system characterized by differing teacher education pathways and social perceptions of the profession.

Methods: A mixed-methods design was employed, combining quantitative survey data (demographics, self-efficacy, resilience scales) with qualitative interviews. Quantitative data analysis used structural equation modeling and mediation analysis. Inductive thematic analysis was applied to the qualitative data gathered from interviews.

Results: Teaching experience strongly and significantly predicted both inclusive self-efficacy and resilience, with self-efficacy also mediating the experience-resilience link. In a key divergence from prior research, familial ties to teaching showed a negligible impact on self-efficacy and a marginal, non-significant influence on resilience. Moreover, gender did not differentiate self-efficacy or resilience, contrasting with previous findings that observed gender-based differences. Qualitative data revealed a multifaceted picture of challenges, coping strategies, and training needs. Diverse conceptualizations of inclusion emerged alongside variable confidence levels in implementing inclusive practices. Self-efficacy was domain-specific and heavily influenced by mastery experiences. Barriers included time constraints and personal limitations, while support networks and mentorship enhanced both self-efficacy and resilience.

Conclusion: The findings underscore a learning trajectory driven by experiential learning, practical challenges, and emotional processes. Addressing identified barriers and leveraging support networks are crucial for fostering effective inclusive education practices. The study’s replication in a new context highlights that the influence of demographic factors on teacher development is not universal and is instead shaped by the specific national education system and socio-cultural environment.

1 Introduction

The education system worldwide is grappling with a fundamental challenge: translating the ideals of inclusive education into everyday classroom realities. At its core, inclusive education is about creating learning environments where all students, regardless of their abilities, needs, or backgrounds, have equal access to opportunities and resources (Carmel et al., 2025; Kamran and Siddiqui, 2024; Schwab et al., 2024). This vision of inclusivity extends beyond physical integration, envisioning a regular classroom teacher – not a specialist – who can effectively teach students with diverse aptitudes and achievement histories (Auhl and Bain, 2025).

The push for inclusive education gained significant momentum with the 1994 UNESCO Salamanca Statement, which called on nations to make education accessible to all children, particularly those with disabilities and those marginalized by social barriers like poverty (Yusuf and Fajari, 2025). Since then, an array of education systems has introduced policies and programs aimed at serving all students, including those with special educational needs (Adams et al., 2025). However, the gap between policy intentions and on-the-ground practices remains stubbornly wide (Mosia and Kotelo, 2024). Schools often fall short of fostering a truly inclusive spirit, partly because the responsibility for inclusion has been thrust upon teachers without adequate support (Walton, 2023). This expectation mismatch is particularly acute in initial teacher preparation programs, where theoretical knowledge often fails to translate into practical skills for managing diverse classrooms (Arnaiz-Sánchez et al., 2023). Unsurprisingly, many novice teachers feel ill-equipped to teach students with varied learning needs (Graham et al., 2025), and entrenched beliefs about disability continue to erect barriers in the classroom (Benson and Alborno, 2025).

The problem is multifaceted. Despite progressive policies, educators often lack clear guidance on implementing inclusive practices (Sharma et al., 2024). The increasing diversity of student populations imposes a perplexity, especially for student-teachers who need substantial support to recognize and address individual learning needs (Obrovská et al., 2024). Teaching in heterogeneous classrooms can be daunting, and navigating this complex landscape requires pre-service teachers to possess not only pedagogical knowledge but also sufficient psychological resilience and self-efficacy (Pov and Kawai, 2025). However, the pathway to developing these psychological assets is not fully understood, revealing critical gaps in the existing literature. While the positive relationship between self-efficacy and resilience is established (Mieres-Chacaltana et al., 2025), several nuances remain underexplored. First, there is a lack of clarity on how specific demographic variables shape this relationship. Second, the underlying mechanisms are not well-defined; for instance, it is unclear whether factors like teaching experience influence resilience directly or indirectly by first bolstering self-efficacy. Finally, quantitative findings often fail to capture the subjective experiences of pre-service teachers, leaving a gap in our understanding of the “why” and “how” behind their reported feelings and strategies.

To address these gaps, this study examines three specific demographic predictors: gender, prior teaching experience, and familial ties to teaching. The rationale for these variables is rooted in their potential to shape a student-teacher’s developing professional identity and beliefs as explained in the following section. Furthermore, this study employs a mixed-methods mediation design to provide a comprehensive analysis. The quantitative component allows for the testing of a structural model to clarify the predictive pathways between demographics, self-efficacy, and resilience, while the qualitative component enriches these findings by exploring the lived experiences, challenges, and support systems that give rise to these psychological constructs. By integrating these approaches, this study seeks to build a more holistic and contextually grounded understanding of pre-service teacher preparedness for inclusive education (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2025).

2 Literature review

Resilience, defined as the ability to sustain psychological well-being and professional commitment amid the chronic stressors of teaching (Fehérvári and Varga, 2023; Gilar-Corbi et al., 2024). In inclusive settings, resilience enables teachers to navigate emotional demands, behavioral complexities, and systemic pressures while maintaining instructional quality (Graziano et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2024; Pozo-Rico et al., 2023). A key factor underpinning teacher resilience is teacher self-efficacy, i.e., the belief in one’s capacity to execute instructional strategies, manage classrooms, and engage students (Emiru and Gedifew, 2024; Wang D. et al., 2024; Wang X. et al., 2024). Recent evidence underscores a symbiotic relationship between these constructs: teachers with robust self-efficacy tend to exhibit greater resilience, which in turn boosts their capacity to thrive in inclusive environments (Mu et al., 2024; Salvo-Garrido et al., 2025). Educators with high self-efficacy are more likely to deploy adaptive teaching strategies (e.g., output = input or flexible grouping), foster student autonomy, and persist through instructional challenges (Vieira et al., 2024; Yang and Wang, 2025; Zee and Koomen, 2016). A strong sense of self-efficacy is reportedly a reliable predictor of successful inclusive practices (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021). Conversely, low self-efficacy often correlates with avoidance of inclusive strategies, overreliance on rigid pedagogies, and heightened stress when holding heterogenous classrooms (Woodcock et al., 2022). Specifically, self-efficacy for inclusion – the confidence in teaching diverse learners in mainstream classrooms – is linked to teachers’ intentions to create inclusive environments (Selenius and Hau, 2024).

While the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and resilience is well-documented (Mu et al., 2024), less is known about how specific demographic factors – such as gender, teaching experience, and having relatives in the teaching profession – influence this dynamic, particularly in the context of inclusive education. The impact of familial ties to teaching on self-efficacy and resilience remains underexplored, and findings on the role of gender are mixed (Alnahdi and Schwab, 2021; Woodcock et al., 2022). Previous teaching experience, however, appears to shape self-efficacy beliefs significantly (Franzen et al., 2024; Symes et al., 2023). The theoretical underpinnings for the influence of these demographic factors can be drawn from Bandura’s (1991). Social Cognitive Theory, which posits that self-efficacy beliefs are built through four main sources. Prior teaching experience directly relates to “mastery experiences” – the most powerful source – where successful performance in challenging situations builds a robust sense of efficacy. Familial ties to teaching can provide “vicarious experiences” (observing family members navigate the profession) and “social persuasion” (receiving encouragement or advice), both of which can shape an aspiring teacher’s confidence. While gender is not a direct source of efficacy, it operates within the social environment, potentially influencing self-perceptions and resilience through cultural norms and role expectations (Mayor-Silva et al., 2025). The scarcity of research on these variables is striking, given that most studies focus on general teacher self-efficacy and resilience rather than the specific context of inclusive teaching. A notable exception is the study by Yada et al. (2021), which found that Finnish pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive practices was positively influenced by having relatives (beyond parents) in the teaching profession and prior teaching experience; in turn, self-efficacy strongly predicted their resilience in delivering inclusive education, which was also reciprocally affected by gender.

This study builds directly on Yada et al.’s (2021) work, aiming to replicate their investigation in a different socio-cultural context with two key enhancements. First, to address the original study’s limitation of a relatively small sample (105 students from one university), this research targets a significantly larger cohort – 283 pre-service teachers across eight universities – thereby increasing the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Moreover, deliberate efforts were made to mirror the original study’s 21% male respondent ratio (by ensuring at least 21% male participation) to maintain demographic comparability. This is not merely a geographical replication but a step toward cross-national validation of the relationships between self-efficacy, resilience, and demographic predictors in inclusive education. Second, and crucially, this study responds to Yada et al.’s call for qualitative insights to complement quantitative data; to this end, interviews were conducted that allowed for the exploration of how self-efficacy and resilience are experienced by those with practical classroom background. By addressing these gaps, this study aims to advance understanding of how demographic factors shape pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy and resilience for inclusive teaching through a mixed-methods approach. Specifically, four research questions guide this inquiry:

RQ1. Does student-teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive teaching predict their inclusion-related resilience?

RQ2. Do student-teachers’ demographic variables (gender, having a relative in the teaching profession, and prior teaching experience) predict their resilience or self-efficacy?

RQ3. Does self-efficacy mediate the effect of demographic variables on resilience?

RQ4. How do student-teachers interpret their resilience and self-efficacy for delivering inclusionary learning, and what barriers do they identify?

By bridging quantitative and qualitative lenses, the present exploration can advance the understanding of how pre-service teachers’ beliefs and experiences coalesce to shape their readiness for inclusive education. This is a step toward ultimately accumulating and enriching the evidence on the topic.

3 Materials and methods

Using a convergent parallel design, chosen to enable simultaneous collection and independent analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data while maintaining the distinct value of each data type, this non-experimental study combined correlational predictive research with a qualitative survey. The research examined possible statistically significant interactions between selected measurable variables, while concurrently collecting and separately analyzing interview data. Approval of the research project was obtained from the ethics committee at the first author’s institution.

3.1 Sample

The respondent sample comprised 283 students enrolled in Baccalaureate and Master teacher programs at eight public universities in Kazakhstan. The researchers, located in three different cities, employed a purposive convenience sampling approach to maximize diversity across different regions while ensuring practical feasibility. After initial contact with the deans of their home institutions, snowball requests were extended to additional universities in the same cities, yielding eight institutions that agreed to distribute the survey link via their internal social-media groups and other digital communication channels. The link led to an electronic questionnaire beginning with a cover letter that outlined several key aspects: the study’s goal, assurances of data confidentiality, voluntarism of participation, and respondents’ right to drop out at any time without penalties. The online survey completion itself served as implicit consent from all participants. The demographic breakdown showed a predominantly female sample, with 217 women (76.7%) and 66 men (23.3%). The age distribution ranged from 17 to 29 years, with participants averaging 22.2 years old.

3.2 Data sources

The questionnaire was structured to collect demographic information along with two Likert-scale measurement instruments. They were translated from English to the target language, then back-translated and juxtaposed to the original inventories to ensure that the resulting statements matched the English-language ones.

3.2.1 Perceived resilience

This variable was estimated using the nine-item questionnaire devised by Yada et al. (2021). The items such as “It is likely that I will stay in the teaching profession for a long time” are scored from 1 to 6, with higher value indicating greater resilience. The scale developers reported its good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). The present survey yielded acceptable reliability of the instrument as well (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

3.2.2 Self-efficacy beliefs

This indicator was gauged via the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practice (TEIP) scale (Sharma et al., 2012). The measurement tool entails 18 items (such as “I am confident in my ability to get parents involved in school activities of their children with disabilities”) rated on a 6-point scale and equally spread over three factors: efficacy in instruction, efficacy in collaboration, and efficacy in managing behaviors. The TEIP had Cronbach’s α above.90 across Chinese, Saudi, Czech, and Japanese demographics (Pivarč, 2025; Wang D. et al., 2024; Wang X. et al., 2024; Yada and Alnahdi, 2024). In this study, the TEIP showed adequate reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.72).

3.2.3 Demographic variables

This subset of variables comprised: (a) previous teaching experience (yes/no); (b) gender (female/male); and (c) having a relative in the teaching profession (yes/no). None of the respondents reported both father and mother being teachers. Hence, the variable from the source paper (Yada et al., 2021) concerning both biological parents as teachers was eliminated from the structural model. The two items in the original survey that demarcated having either a parent or some other relative in the teaching profession were herein merged into one item inquiring whether the person has any relative as a teacher.

3.2.4 Qualitative data

Unstructured interviews were held with 27 participants who had specifically reported prior teaching experience in the survey. Out of 36 such individuals identified, 27 agreed to be interviewed. The interviews followed an unstructured protocol designed to allow participants to freely express their experiences and perspectives without predetermined questions. This approach enabled natural conversation flow while ensuring that key areas of inquiry were covered through responsive follow-up questions. Each interview began with broad prompts asking participants to describe their experiences with inclusive teaching during their practical placements, followed by probes that emerged organically from their responses. The communications were either in person or via video conference, depending on participant preference and logistical constraints, with all sessions audio-recorded for transcription. The interviews lasted approximately 15–20 min each and explored participants’ interpretations of their self-efficacy and resilience for inclusive teaching. Key areas of inquiry included their conceptualization of inclusive education, specific challenges encountered during practical experiences, coping strategies employed, and perceived gaps in their university training.

3.3 Statistics

To address RQ1 and RQ2, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was run using SEMinR software package in R, with 5,000 bootstraps. A priori sample size calculation using semPower R package (power = 0.90, p = 0.05, F0 = 0.25) suggested a target sample size of 268 participants required to compute SEM. Hence, the here reported sample (n = 283) is adequate for the analysis. How well the collected data fit the model was tested through common criteria: the ratio of chi-squared to the degree of freedom (χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). To answer RQ3, a mediation analysis was performed. Since the mediator variables were binary in nature, the diagonally weighted least square estimation was employed (Jia et al., 2023). The interviews (RQ4) were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and machine-coded using NVivo software. The data was then subjected to an inductive thematic analysis by two trained coders. To ensure reliability, both coders independently analyzed about 20% of the transcripts to establish initial codes. After achieving an inter-rater agreement of Cohen’s Kappa = 0.80, the remaining transcripts were divided between the raters and coded. The inductive approach was employed via the constant comparative method where the coders first performed open coding line-by-line to identify provisional labels, proceeded to axial coding to cluster related codes into categories, and finally used selective coding to distil overarching themes and their sub-categories (Korseberg and Stalheim, 2025). This systematic approach allowed for the emergence of insights directly from the data without imposing pre-existing frameworks.

4 Results

4.1 Path analysis

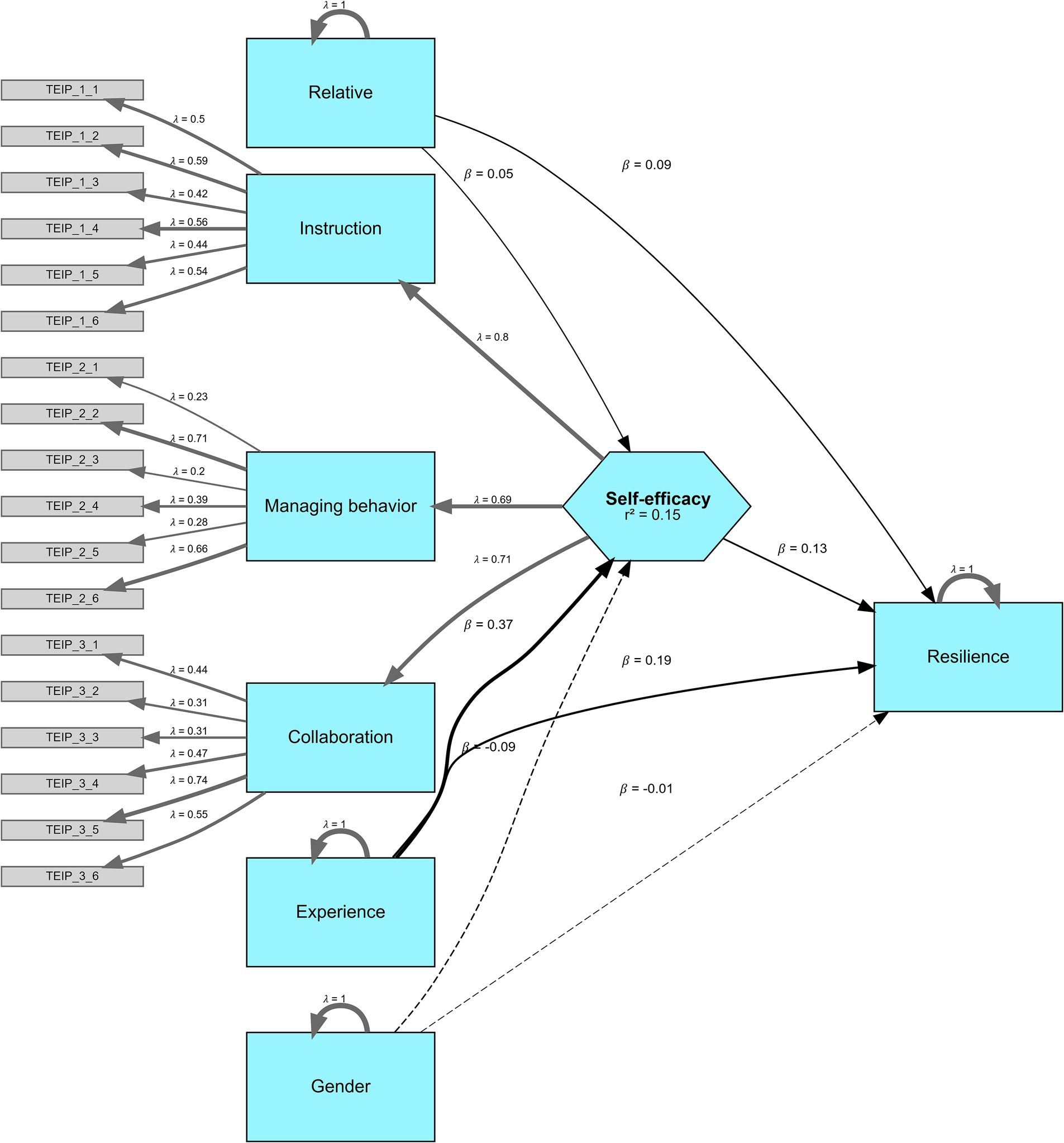

The PLS-SEM analysis revealed a nuanced pattern of relationships among the variables under investigation. The structural path model had an acceptable fit to the data (χ2/df = 0.859, p = 0.926; CFI = 0.944; TLI = 0.961; SRMR = 0.045; RMSEA = 0.013). The TEIP items loaded onto the three corresponding dimensions adequately. Starting with the influence of familial relational models on teacher identity, a reported relative as a teacher did not emerge as a significant predictor of inclusion self-efficacy (β = 0.066, 95% confidence interval [CI] [−0.029, 0.137], p = 0.422) (hereon, except Figure 1, bootstrapped betas and confidence intervals are reported). In other words, having a relative who is a teacher in one’s family background neither substantially bolstered nor undermined student-teachers’ confidence in their ability to inclusively teach diverse students. However, this familial influence hovered just outside the conventional threshold of statistical significance in predicting resilience, suggesting a marginal, albeit non-significant, positive trend (β = 0.080, 95% CI [0.012, 0.170], p = 0.066); thus, it can be tentatively posited that having teacher relatives in the family might have a weak, favorable effect on student-teachers’ capacity to withstand challenges in the classroom. The standardized (but not bootstrapped) effects for all variables are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structural model. Solid line: positive path. Dotted line: negative path. Line thickness/boldness: magnitude of the coefficient. λ: regression coefficient relating latent and observable variables. All coefficients are standardized.

In stark contrast, teaching experience proved to be a robust and significant antecedent of both inclusion self-efficacy (β = 0.382, 95% CI [0.330, 0.442], p = 0.001) and resilience (β = 0.197, 95% CI [0.097, 0.271], p = 0.001). This finding underscores the paramount importance of hands-on teaching experience in shaping student-teachers’ beliefs in their ability to teach inclusively and to bounce back from setbacks. The more extensive their practical experience in classrooms, the more pronounced their self-efficacy in inclusion and their resilience became, with the effect on inclusion self-efficacy being particularly pronounced. This lends strong support to the notion that actual teaching practice is a critical crucible for the development of these essential teacher competencies.

Furthermore, a key psychological mechanism linking these constructs became apparent: inclusion self-efficacy itself acted as a significant facilitator of resilience (β = 0.159, 95% CI [0.060, 0.245], p = 0.044). This result implies that student-teachers who felt more confident in their capacity to teach diverse learners effectively were also more likely to exhibit higher levels of resilience in the face of challenges. In essence, believing in one’s ability to foster inclusive learning environments appears to be an important inner resource that helps teachers endure the inevitable stresses and difficulties of the profession.

On the other hand, gender did not significantly influence either of the two focal outcomes. Specifically, it neither substantially impacted inclusion self-efficacy (β = −0.111, 95% CI [−0.214, 0.017], p = 0.306) nor resilience (β = −0.002, 95% CI [−0.114, 0.070], p = 0.895). These non-findings suggest that, in the context of this study, male and female student-teachers were essentially on a par regarding both their confidence in teaching inclusively and their ability to cope with adversity. The extremely weak and non-significant effect sizes here indicate that gender, by itself, is not a meaningful differentiator of these critical teacher attributes.

4.2 Mediation analysis

Given the negligible predictive power of gender, it was ruled out from the mediation analysis. The latter detected a statistically observable indirect effect of inclusion-related self-efficacy on resilience through teaching experience (unstandardized β = 0.581, standard error = 0.280, z = 2.074, p = 0.038, 95% CI [0.032, 1.131]). This finding suggests that pre-service teachers with higher self-efficacy tend to demonstrate greater resilience, and this relationship is partially explained by their past experience in teaching roles. Conversely, the analysis did not support a significant mediating role of having a relative working as a teacher between inclusion self-efficacy and resilience (unstandardized β = 0.384, standard error = 0.318, z = 1.207, p = 0.228, 95% CI [−0.240, 1.007]). These results highlight the importance of experience, rather than family connections to the profession, in explaining how self-efficacy for inclusive practices contributes to resilience among student-teachers.

4.3 Qualitative evidence

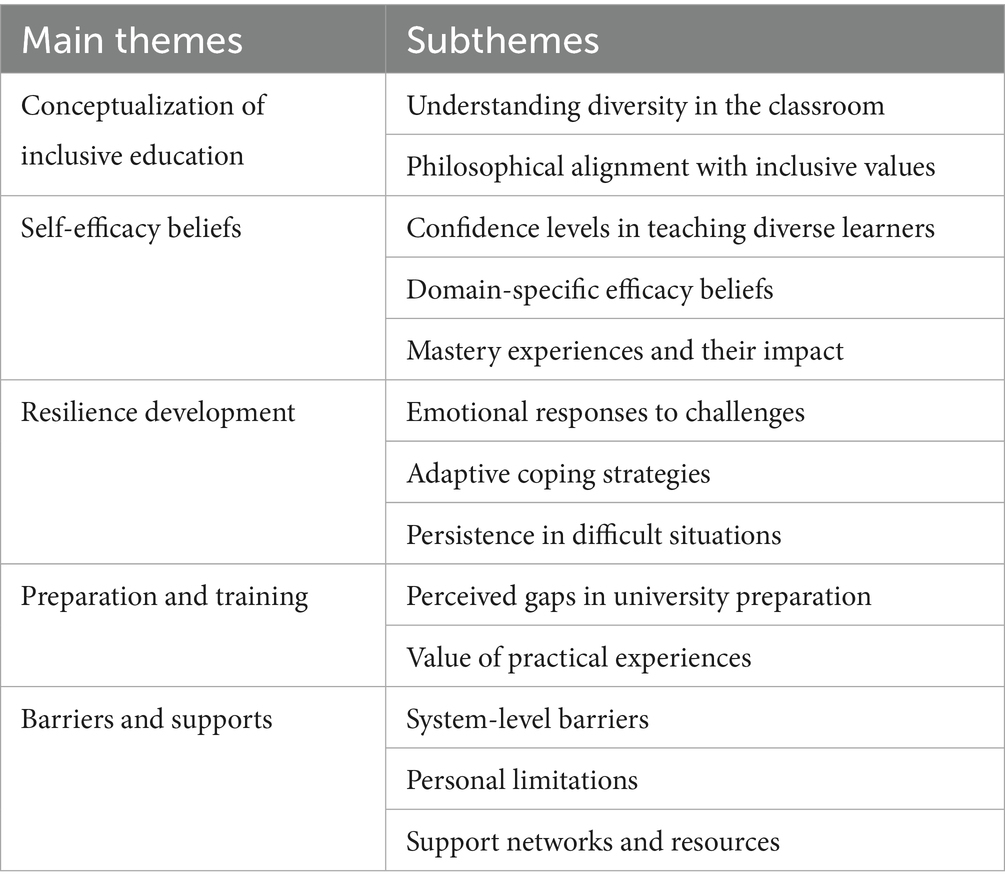

The qualitative analysis, based on interviews with 27 pre-service teachers who had prior teaching experience, illuminated the complex interplay of self-efficacy and resilience in the context of inclusive education. Five key themes emerged, offering a cohesive narrative of how these teachers develop the confidence and resilience needed to teach diverse learners. Table 1 summarizes the main themes and subthemes derived from the interviews. Overall, pre-service teachers reported varied levels of self-efficacy and resilience when considering their capacity to implement inclusive teaching practices. Participants reflected on their experiences with diverse learners during teaching placements, highlighting personal strengths, challenges, and coping mechanisms.

Table 1. Summary of participants’ perceptions of self-efficacy and resilience for inclusive teaching.

4.3.1 Theme one: Conceptualization of inclusive education

Participants’ understanding of inclusive education evolved through their teaching experiences, shifting from a focus on students with disabilities to a broader appreciation of diverse classroom needs. This evolution aligns with the quantitative finding that teaching experience significantly predicts self-efficacy for inclusive practices. For instance, one participant noted how their perspective widened during a placement: “Before my placement, I thought inclusion was just about kids with diagnosed conditions. But after being in that Year 6 class, I realized it’s so much more: gifted students who finish everything in five minutes, kids dealing with family stuff… it is literally every single student needing something different. It was eye-opening” (P3).

Many expressed a strong philosophical commitment to inclusion, yet acknowledged the practical challenges of implementation. Another respondent shared, “In theory, I am all for inclusion… But then you are actually in there with 28 kids, trying to differentiate for everyone, and it is like… the ideology crashes into reality. I still believe in it, but I am way more realistic now about how freaking hard it is to do well” (P9). One more interviewee recalled, “I had this moment during my placement where this kid with pretty severe learning difficulties answered a question in class discussion. It was not completely right, but you could see his reasoning. The whole class just waited, no one laughed or anything. That is when I got it – inclusion is not just about different worksheets, it is about creating this culture where everyone belongs. That kid felt safe to speak up, and that is huge” (P24). These reflections suggest that a broader conceptualization may enhance teachers’ confidence in creating inclusive environments, while a narrower focus could hinder their ability to address diverse needs, underscoring the role of experience in building self-efficacy.

4.3.2 Theme two: Self-efficacy beliefs

Participants displayed varied confidence levels in teaching diverse learners, often tied to specific domains and bolstered by practical successes. This domain-specific self-efficacy aligns with the quantitative result that teaching experience strongly predicts self-efficacy, with mastery experiences serving as a key mechanism. For example, one student-teacher described a mix of optimism and uncertainty: “On a scale of 1–10? I would say I am like a 6 with inclusion. I get the basic idea, I have got some strategies, but there are moments when I’m totally winging it. Like that kid with selective mutism – I had no clue how to include her in group work. I tried partner work instead, and things moved on from the dead point, which made me feel like maybe I can figure this out after all” (P11).

Confidence was higher in areas like behavior management than in curriculum modification, as one respondent explained: “I am pretty good at the behavioral stuff. Like, I can handle the kid who is acting out or not paying attention. But when it comes to actually modifying curriculum content for different ability levels? That is where I freeze up. I just do not know how far to simplify without making it too easy or insulting their intelligence” (P8).

Successful experiences significantly boosted confidence, with a participant recalling: “I’m recalling a student with dyslexia in my class… I was terrified of teaching him because I did not know how to help. But I tried using colored overlays and audio support, and he actually completed the whole assignment. His mom emailed my mentor saying it was the first time he had not given up in frustration. That one success changed everything for me – I realized I actually could do this” (P5). These accounts highlight how experience-driven confidence in specific domains supports the quantitative finding that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between experience and resilience.

4.3.3 Theme three: Resilience development

The emotional challenges of inclusive teaching tested participants’ resilience, yet these difficulties fostered adaptive coping strategies and persistence. Participants often described initial struggles with self-doubt. For instance, one recounted, “There was a kid with really challenging behavior, and nothing I tried seemed to work. I took it so personally, like I was failing him. My mentor kept saying ‘It is not about you,’ but it felt like it was. That was the hardest part – separating my worth as a teacher from whether this one student was having a good day” (P1).

However, practical strategies emerged to sustain their commitment, such as maintaining a “win jar” to record small successes, which helped one participant stay motivated on tough days (P7). Persistence grew from facing setbacks, as another interviewee admitted: “My big turning point was when I stopped trying to do everything perfectly for every kid. I was killing myself trying to be the perfect inclusive teacher, and my mentor pulled me aside and said, ‘You are going to burn out in your first year if you keep this up.’ Now I focus on doing a few things really well each day rather than doing everything offhand” (P15). These findings illustrate how resilience develops through experience, complementing the quantitative link between self-efficacy and resilience, and suggesting that emotional support is critical in teacher preparation.

4.3.4 Theme four: Preparation and training

Participants frequently contrasted the inadequacy of university training with the transformative value of practical experience. Many felt that theoretical preparation left them unprepared for real classrooms. One student remarked, “We had exactly one course on inclusive education, and it was all theory like Vygotsky… Well, I am aware of the zone of proximal development, but that does not tell me what to do when a non-verbal student needs to participate in a class debate. The disconnect between the textbook and the classroom is massive” (P4). Another teacher-in-training lamented: “No one ever talked about the emotional side of inclusive teaching. Like, how to not take it personally when your carefully planned accommodations do not work. Or how to keep going when you feel completely out of your depth. I think they are afraid if they told us how hard it really is, no one would become teachers” (P13).

In contrast, hands-on experience was seen as essential, with a respondent noting: “Everything I know about inclusion I learned in the classroom, not from textbooks. Watching my mentor differentiate on the fly, seeing what works and what bombs, making mistakes and having to fix them in real-time – that is what actually prepared me. You cannot learn that from a lecture” (P16). This emphasis on experiential learning reinforces the quantitative finding that teaching experience enhances self-efficacy and resilience, highlighting a need for teacher education to prioritize practical training.

4.3.5 Theme five: Barriers and supports

Systemic and personal barriers challenged participants’ ability to implement inclusive practices, yet support networks mitigated these obstacles. Time constraints were a common system-level barrier, as one pre-service teacher expressed: “The biggest barrier is just time. To do inclusion properly, you need time to plan, craft content, consult mentors, etc. But in reality, you are lucky if you get five minutes to scarf down lunch” (P23).

Personal limitations, such as biases, also emerged, with an interviewee reflecting: “I realized I have these unconscious biases about what kids can achieve. There was an autistic student, and I was so impressed when he completed this basic task that I probably over-praised him. Then my mentor pointed out that I had lower expectations for him than the other students. That was a real wake-up call about my own prejudices” (P12).

Support from mentors and peers, however, bolstered both self-efficacy and resilience. A different respondent noted, “What really built my resilience was my mentor’s honesty. She did not pretend inclusion was easy or that she had all the answers. She would openly say, ‘I have been teaching 15 years and I still struggle with this.’ Seeing an experienced teacher still finding it challenging but persevering anyway. That showed me it is okay to find this hard as long as you do not give up” (P8). These insights suggest that while barriers are significant, supportive environments can boost teachers’ capacity to overcome them, aligning with the quantitative emphasis on experience as a predictor of resilience.

5 Discussion

This investigation set out to examine the interplay between self-efficacy for inclusive practices and resilience among pre-service teachers within a novel socio-cultural setting, building upon the foundational work of Yada et al. (2021). The study sought to determine if self-efficacy predicts resilience, whether specific demographic factors (gender, having teaching relatives, prior experience) influence these constructs, the potential mediating role of self-efficacy, and how student-teachers themselves articulate their experiences with self-efficacy, resilience, and barriers in inclusive education. The quantitative analysis affirmed that higher self-efficacy in inclusive teaching significantly corresponds with greater resilience. Furthermore, prior teaching experience emerged as a potent predictor for both heightened self-efficacy and enhanced resilience, whereas familial connections to the teaching profession showed only a marginal, non-significant link to resilience, and gender demonstrated no discernible impact on either outcome. Qualitative insights echoed these findings, illustrating the complex tapestry of pre-service teachers’ conceptualizations of inclusion, their fluctuating confidence levels shaped by practical encounters, the emotional labor involved, and the perceived inadequacies in formal preparation contrasted with the high value placed on experiential learning.

Interpreting the quantitative results unveils a compelling narrative about the development of essential teacher attributes for inclusive settings. The robust positive relationship between prior teaching experience and both self-efficacy and resilience underscores the irreplaceable value of hands-on practice. Engaging directly with diverse learners in real classroom environments appears to be a critical forge for building confidence (self-efficacy) in managing inclusive demands and cultivating the psychological fortitude (resilience) needed to persist through challenges. This finding suggests that pedagogical knowledge, while necessary, is insufficient without the experiential crucible where theoretical concepts are tested and refined. Moreover, the significant pathway from self-efficacy to resilience indicates that a pre-service teacher’s belief in their capability to implement inclusive strategies functions as an internal resource, bolstering their capacity to navigate the stresses inherent in the profession. The non-significant findings for gender and the marginal effect of having teacher relatives suggest these factors may be less universally impactful than direct experience, at least within this specific sample and context.

Comparing these findings with the seminal work of Yada et al. (2021) reveals both convergences and divergences. Consistent with the Finnish study, this investigation confirmed a potent positive association between pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive practices and their self-rated resilience, reinforcing this link as a potentially fundamental aspect of teacher development for inclusion. However, divergences emerged regarding demographic predictors. First, the absence of gender differences in the present sample contrasts with the Finnish finding that women reported higher resilience, aligning with the contradictory literature Yada et al. themselves acknowledged.

While this study was not designed to test this specific socio-cultural question, one possible post-hoc interpretation relates to the differing status of the teaching profession. It could be hypothesized that in the current study country, where teaching is an overwhelmingly feminized, low-paid profession with limited social prestige, any potential gender-specific effects on resilience may be overshadowed by shared concerns about economic precarity and professional status; that is, both male and female student-teachers may perceive the profession through a lens of economic vulnerability and low status, thereby dampening any gender-specific boost to self-efficacy or resilience that might otherwise arise from role congruence. This contrasts with Finland, where teaching is also feminized (Räsänen et al., 2024), but it enjoys high social prestige (Hansen and Jóhannesson, 2024), potentially amplifying gendered role congruence effects that bolster women’s resilience.

Whereas Yada et al. found an influence of having relatives (other than parents) in the profession on self-efficacy, this study observed no significant impact of having any relative teacher on self-efficacy, and only a near-significant trend toward resilience. This may be rooted in contrasting teacher-education pathways. Finnish programs integrate extended, highly mentored practicum periods from the first year (Mankki et al., 2025; Varis et al., 2023), reducing the relative influence of family socialization. Conversely, the local system front-loads theoretical coursework and offers shorter, less standardized placements, making prior informal exposure via relatives less impactful. Additionally, this quantitative finding is indirectly explained by the qualitative data. The interviews pointed to the primacy of direct, hands-on mastery experiences as a critical factor in building confidence and resilience (Themes 2 and 4). This emphasis on personal practice suggests that more passive sources of self-efficacy, such as the vicarious experiences that might be gained from relatives, play a comparatively minor role in this context.

Importantly, while both studies recognized the role of experience, the present analysis explicitly demonstrated its strong direct predictive power for both self-efficacy and resilience, and further identified self-efficacy as mediating the experience-resilience relationship, adding a layer of explanatory depth. The larger, multi-university sample and the mixed-methods design of this study address specific limitations noted by Yada et al., enhancing the robustness of these comparative points.

The qualitative data richly complemented and extended the quantitative results, offering a granular view into the lived experiences of pre-service teachers grappling with inclusive education. Participants’ varied conceptualizations, often caught between aspirational ideals and practical complexities (Theme 1), highlight an ongoing process of sense-making. Their self-efficacy (Theme 2) appeared dynamic and domain-specific – stronger perhaps in classroom management than intricate curriculum adaptation – and profoundly shaped by mastery experiences, where both successes and navigated failures proved formative. This aligns with Bandura’s social cognitive theory, emphasizing the power of enactive attainment in shaping efficacy beliefs. The narratives surrounding resilience development (Theme 3) painted a picture of significant emotional challenge met with emerging adaptive coping strategies, such as cognitive reframing (“win jar,” focusing on achievable goals) and sheer persistence, illustrating resilience not as a fixed trait but a developed capacity. These accounts provide experiential validation for the quantitative pathway showing self-efficacy as a significant predictor of resilience (β = 0.159, p = 0.044), as participants described how confidence built through successful experiences directly contributed to their ability to persist through challenges. Critically, the qualitative findings underscored a perceived disconnect between theoretical university preparation and the demands of real classrooms (Theme 4), while simultaneously affirming the paramount importance of practical placements for skill development and confidence building. Identified barriers, spanning systemic constraints like time pressure to personal limitations like fear and bias (Theme 5), alongside vital supports like peer networks and candid mentorship, provide tangible targets for intervention.

The connection between these qualitative themes and the broader literature is clear. For instance, the systemic barrier of time pressure reported by our participants (Theme 5) is a well-documented source of teacher stress (Zagni et al., 2025) that can erode both self-efficacy and resilience (Floress et al., 2024; Gilar-Corbi et al., 2024). Conversely, the crucial role of mentor and peer support networks aligns with research identifying strong social connections as a key protective factor that fosters teacher resilience (Smala et al., 2025; Versfeld et al., 2025). The qualitative data suggest that resilience is cultivated through a combination of cognitive reappraisal (changing how challenges are viewed), emotional regulation (managing distress), seeking social support (drawing on peers and mentors), and problem-solving (adapting strategies), reflecting established models of stress and coping. The gap between theory and practice reported by participants points toward a potential lack of situated learning opportunities within university coursework, making practicum experiences disproportionately influential.

5.1 Theoretical contributions and practical implications

This study contributes meaningfully to both research and practice. For research, it provides a valuable cross-national replication and extension of Yada et al.’s (2021) findings, increasing the generalizability of the core self-efficacy-resilience relationship while also highlighting context-dependent variations in demographic predictors. By incorporating qualitative data, it answers the call for better understanding and offers insights into the processes behind the quantitative correlations, particularly regarding how experience shapes beliefs and coping mechanisms. Methodologically, it demonstrates the utility of mixed-methods designs and SEM in exploring complex educational phenomena.

In practical terms, the findings illuminate several pathways for enhancing pre-service teacher preparation. First, the dominant role of prior teaching experience underscores the need for structured, scaffolded field placements that maximize opportunities for mastery in inclusive settings. To bridge the theory-practice divide, teacher education programs could adopt models like the Partner School Program implemented in Austria (Resch et al., 2024), which pairs universities with schools to provide student-teachers with sustained, mentored experiences. While the Austrian program itself does not focus on inclusive instruction, it could be customized locally to embrace inclusive education. For example, partnerships could prioritize placements in schools serving diverse learners, with mentors trained to guide pre-service teachers in adapting curricula and fostering resilience through reflective practice.

Second, the emotional challenges reported by participants highlight the need for teacher education programs to explicitly address resilience-building. Mentorship programs could train mentors to model resilient behaviors, such as openly discussing setbacks and normalizing the emotional labor of inclusive teaching (Diab and Green, 2024). Incorporating explicit resilience-building modules focused on emotional regulation, coping strategies (like those identified qualitatively), and accessing support networks could better equip pre-service teachers for the affective demands of inclusion.

In sum, the here reported exploration captured evidence from practice for the critical nexus between hands-on experience, self-efficacy, and resilience in the preparation of teachers for inclusive education. The investigation confirmed that robust self-efficacy beliefs are significantly linked to greater resilience, and that prior teaching experience serves as a powerful catalyst for both. While familial ties to teaching showed marginal relevance and gender differences were non-significant in this context, the qualitative narratives vividly portrayed the journey of developing inclusive competence as one marked by practical challenges, emotional hurdles, essential coping strategies, and a learning curve heavily reliant on experiential wisdom. This study stands among the first to replicate and substantially extend the work of Yada et al. (2021) in a different national context using a larger sample and integrating qualitative findings. It corroborates the imperative for teacher education to move beyond theoretical exposition and actively cultivate the practical confidence and psychological stamina that enable educators not just to survive, but to thrive, in the dynamic and demanding landscape of inclusive classrooms.

5.2 Limitations and directions for future research

While this study advances understanding, certain design nuances warrant acknowledgment. First, the qualitative component, while insightful, focused exclusively on participants reporting prior teaching experience; this purposive sampling means the perspectives of novices without such experience regarding their initial self-efficacy, resilience, and perceived training gaps might be underrepresented. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data collection limits the ability to draw definitive causal conclusions, even with SEM indicating directional paths.

Future research should explore the impact of the quality and nature (e.g., level of support, diversity of learners encountered) of prior teaching experiences, rather than just its presence or absence. Moreover, exploring how pre-service teachers without prior experience develop self-efficacy and resilience presents another important research direction. Ultimately, fostering such well-prepared, efficacious, and resilient teachers is fundamental to realizing the promise of equitable education for all learners.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee at Alikhan Bokeikhan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. BO: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. KK: Data curation, Writing – original draft. RO: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. AN: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, D., Moosa, V., Shareefa, M., Mohamed, A., and Tan, K. L. (2025). Assessing inclusive school leadership practices in Malaysia: instrument adaptation and validation. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 72, 263–281. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2024.2354895

Alnahdi, G. H., and Schwab, S. (2021). Special education major or attitudes to predict teachers’ self-efficacy for teaching in inclusive education. Front. Psychol. 12:680909. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680909

Arnaiz-Sánchez, P., De Haro-Rodríguez, R., Caballero, C. M., and Martínez-Abellán, R. (2023). Barriers to educational inclusion in initial teacher training. Societies 13:31. doi: 10.3390/soc13020031

Auhl, G., and Bain, A. (2025). Do pre-service teachers build capacity for inclusive classroom teaching during their teacher education program? Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2024.2362325

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 248–287. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

Benson, S. K., and Alborno, N. (2025). Inclusive teaching online: lessons learned. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 72, 803–821. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2024.2358841

Carmel, J. M., Chapman, S., and Wright, P. (2025). Disability justice: the challenges of inclusion in everyday life. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2025.2456288

Diab, A., and Green, E. (2024). Cultivating resilience and success: support systems for novice teachers in diverse contexts. Educ. Sci. 14:711. doi: 10.3390/educsci14070711

Emiru, E. K., and Gedifew, M. T. (2024). The effect of teacher self-efficacy on learning engagement of secondary school students. Cogent Educ. 11:2308432. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2308432

Fehérvári, A., and Varga, A. (2023). Resilience and inclusion. Evaluation of an educational support programme. Educ. Stud. 49, 147–165. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1835614

Floress, M. T., Jenkins, L. N., Caldwell, S., and Hampton, K. (2024). Teacher stress and self-efficacy relative to managing student behavior. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 28, 257–269. doi: 10.1007/s40688-022-00439-z

Franzen, K., Moschner, B., and Hellmich, F. (2024). Predictors of primary school teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for inclusive education. Front. Educ. 9:1437839. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1437839

Gilar-Corbi, R., Perez-Soto, N., Izquierdo, A., Castejón, J., and Pozo-Rico, T. (2024). Emotional factors and self-efficacy in the psychological well-being of trainee teachers. Front. Psychol. 15:1434250. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1434250

Graham, A., MacDougall, L., Robson, D., and Mtika, P. (2025). Newly qualified teachers’ experiences of implementing an inclusive pedagogy in schools located in high poverty environments. J. Educ. Teach. 51, 308–322. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2025.2468634

Graziano, F., Mastrokoukou, S., Monchietto, A., Marchisio, C., and Calandri, E. (2024). The moderating role of emotional self-efficacy and gender in teacher empathy and inclusive education. Sci. Rep. 14:22587. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70836-2

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., and Vantieghem, W. (2021). Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices about two inclusive frameworks: universal design for learning and differentiated instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103503. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503

Hansen, P., and Jóhannesson, I. Á. (2024). Contrasting Nordic education policymakers’ reflections on the future across time and space. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 68, 677–688. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2023.2175249

Jia, F., Wu, W., and Chen, P.-Y. (2023). Testing indirect effect with a complete or incomplete dichotomous mediator. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 76, 539–558. doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12313

Kamran, M., and Siddiqui, S. (2024). Roots of resilience: uncovering the secrets behind 25+ years of inclusive education sustainability. Sustainability 16:4364. doi: 10.3390/su16114364

Korseberg, L., and Stalheim, O. R. (2025). The role of digital technology in facilitating epistemic fluency in professional education. Prof. Dev. Educ. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2024.2421489

Lu, J., Chen, J., Li, Z., and Li, X. (2024). A systematic review of teacher resilience: a perspective of the job demands and resources model. Teach. Teach. Educ. 151:104742. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104742

Mankki, V., Koski, J., Stenberg, K., and Poikkeus, A. M. (2025). Teaching practicum research in Finland: a scoping review. Educ. Rev. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2025.2506794

Mayor-Silva, L. I., Moreno, G., Meneses-Monroy, A., Martín-Casas, P., Hernández-Martín, M. M., Moreno-Pimentel, A. G., et al. (2025). Influence of gender role on resilience and positive affect in female nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Healthcare 13:336. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13030336

Mieres-Chacaltana, M., Salvo-Garrido, S., and Dominguez-Lara, S. (2025). Modeling the effects of teacher resilience and self-efficacy on prosocialness: implications for sustainable education. Sustainability 17:3874. doi: 10.3390/su17093874

Mosia, P. A., and Kotelo, T. T. (2024). Teacher training for inclusive education in Lesotho: assessing factors that influence teacher attitudes towards supporting LSEN in mainstream schools. Cogent Educ. 11:2380167. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2380167

Mu, G. M., Gordon, D., Liang, J., Zhao, L., Alonso, R. A., Juri, M. Z., et al. (2024). A meta-analysis of the correlation between teacher self-efficacy and teacher resilience: concerted growth and contextual variance. Educ. Res. Rev. 45:100645. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2024.100645

Obrovská, J., Svojanovský, P., Kratochvílová, J., Lojdová, K., Tůma, F., and Vlčková, K. (2024). Promises and challenges of differentiated instruction as pre-service teachers learn to address pupil diversity. J. Educ. Teach. 50, 403–420. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2023.2247356

Pivarč, J. (2025). The Czech version of the teacher efficacy for inclusive practice (TEIP) scale: validation and psychometric analysis of the instrument with primary school teachers. Int. J. Incl. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2024.2371873

Pov, S., and Kawai, N. (2025). Pre-service teachers’ preparation for inclusive practices in Cambodia: experience, self-efficacy and concerns about inclusion. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 25, 118–131. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12715

Pozo-Rico, T., Poveda, R., Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R., Castejón, J. L., and Gilar-Corbi, R. (2023). Revamping teacher training for challenging times: teachers’ well-being, resilience, emotional intelligence, and innovative methodologies as key teaching competencies. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 1–18. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S382572

Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Väisänen, P., Pyhältö, K., and Soini, T. (2024). Experienced burnout and teacher–working environment fit: a comparison of teacher cohorts with or without persistent turnover intentions. Res. Pap. Educ. 39, 277–300. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2022.2125054

Resch, K., Schrittesser, I., and Knapp, M. (2024). Overcoming the theory-practice divide in teacher education with the ‘partner school programme’. A conceptual mapping. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 47, 564–580. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2022.2058928

Salvo-Garrido, S., Cisternas-Salcedo, P., and Polanco-Levicán, K. (2025). Understanding teacher resilience: keys to well-being and performance in Chilean elementary education. Behav. Sci. 15:292. doi: 10.3390/bs15030292

Sánchez-Jiménez, M., Maravé-Vivas, M., Gil-Gómez, J., and Salvador-Garcia, C. (2025). Building pre-service teachers’ resilience through service-learning: an explanatory sequential mixed methods study. Front. Psychol. 16:1568476. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1568476

Schwab, S., Resch, K., and Alnahdi, G. (2024). Inclusion does not solely apply to students with disabilities: pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive schooling of all students. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 28, 214–230. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1938712

Selenius, H., and Hau, H. G. (2024). A scoping review on the psychometric properties of the teacher efficacy for inclusive practices (TEIP) scale. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 68, 792–802. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2023.2185811

Sharma, U., Loreman, T., and Forlin, C. (2012). Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 12, 12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x

Sharma, U., Loreman, T., May, F., Romano, A., Lozano, C. S., Avramidis, E., et al. (2024). Measuring collective efficacy for inclusion in a global context. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 167–184. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2195075

Smala, S., McLay, K., and Gillies, R. M. (2025). Teacher relationships and social connectedness. Teach. Teach. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2025.2494036

Symes, W., Lazarides, R., and Hußner, I. (2023). The development of student teachers’ teacher self-efficacy before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach. Teach. Educ. 122:103941. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103941

Varis, S., Heikkilä, M., Metsäpelto, R., and Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. (2023). Finnish pre-service teachers’ identity development after a year of initial teacher education: adding, transforming, and defending. Teach. Teach. Educ. 135:104354. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104354

Versfeld, J., Ebersöhn, L., Ferreira, R., and Graham, M. A. (2025). Social connectedness as a pathway to teacher resilience in challenged contexts. Int. J. Educ. Res. 131:102601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2025.102601

Vieira, L., Rohmer, O., Jury, M., Desombre, C., Delaval, M., Doignon-Camus, N., et al. (2024). Attitudes and self-efficacy as buffers against burnout in inclusive settings: impact of a training programme in pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 144:104569. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104569

Walton, E. (2023). Why inclusive education falters: a Bernsteinian analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2023.2241045

Wang, X., Gao, Y., Wang, Q., and Zhang, P. (2024). Relationships between self-efficacy and teachers’ well-being in middle school English teachers: the mediating role of teaching satisfaction and resilience. Behav. Sci. 14:629. doi: 10.3390/bs14080629

Wang, D., Huang, L., Huang, X., Deng, M., and Zhang, W. (2024). Enhancing inclusive teaching in China: examining the effects of principal transformational leadership, teachers’ inclusive role identity, and efficacy. Behav. Sci. 14:175. doi: 10.3390/bs14030175

Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., Subban, P., and Hitches, E. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 117:103802. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103802

Yada, A., and Alnahdi, G. H. (2024). A comparative study on Saudi and Japanese in-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education and self-efficacy in inclusive practices. Educ. Stud. 50, 539–557. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2021.1969646

Yada, A., Björn, P. M., Savolainen, P., Kyttälä, M., Aro, M., and Savolainen, H. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy in implementing inclusive practices and resilience in Finland. Teach. Teach. Educ. 105:103398. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103398

Yang, X., and Wang, Y. (2025). The relation between teaching self-efficacy and behavior of experimental design teaching in Chinese science teachers. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 43, 125–144. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2023.2248022

Yusuf, F. A., and Fajari, L. E. W. (2025). Empowering inclusive education: management practices in pilot elementary schools for inclusion. Educ. Process Int. J. 15:e2025098. doi: 10.22521/edupij.2025.15.98

Zagni, B., Pellegrino, G., Ianes, D., and Scrimin, S. (2025). Unraveling teacher stress: a cumulative model of risks and protective factors in Italian schools. Int. J. Educ. Res. 131:102603. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2025.102603

Keywords: cross-sectional study, inclusive education, initial teacher education, psychological resilience, teacher self-efficacy

Citation: Shuakbayeva Z, Ospanova B, Kalkeyeva K, Orazaliyeva R and Nurekenova A (2025) Replicating the pathways to resilience: demographic predictors, self-efficacy, and inclusive teaching among pre-service teachers. Front. Educ. 10:1640288. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1640288

Edited by:

Israel Kibirige, University of Limpopo, South AfricaReviewed by:

Ioannis Dimakos, University of Patras, GreeceYanhua He, Fudan University, China

Sigamoney Naicker, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

Panpan Zhang, Xi'an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2025 Shuakbayeva, Ospanova, Kalkeyeva, Orazaliyeva and Nurekenova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhulduz Shuakbayeva, emh1bGR1ei5zaHVha2JheWV2YUBtYWlsLnJ1

Zhulduz Shuakbayeva

Zhulduz Shuakbayeva Bibigul Ospanova1

Bibigul Ospanova1