- Learning Research and Development Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Adaptive expertise is central to teachers’ ability to facilitate ambitious, “student-centered” instruction in K-12 classrooms. Teachers are supported to develop adaptive expertise when they are provided opportunities to build their pedagogical knowledge and reasoning skills in authentic, “practice-based” professional learning contexts. In this article, we illustrate in depth how one empirically supported routine, Mental Simulations for Teacher Reflection (MSTR), can facilitate this learning in a video-based instructional coaching context. Using case study analytic techniques, we specifically identify the finer-grain subcomponents involved in an expert-facilitated MSTR routine and show how they are orchestrated using an illustrative vignette of a post-lesson reflective coaching conversation. We also provide a detailed description of the theoretical and empirical foundations of MSTR as a routine for developing adaptive teaching expertise. By elucidating and unpacking the detailed processes that underlie robust enactment of MSTR, we contribute insights that can help advance more consistent and high-quality teacher learning in similar kinds of reflection-based learning contexts.

Introduction

Pre-service and in-service teacher education programs increasingly emphasize teachers’ learning of ambitious, “student-centered” forms of teaching. Such teaching practices promote active student engagement in inquiry-focused classroom activities, which growing research suggests are critical for meeting ambitious “21st century” student learning goals (Resnick et al., 2018; Resnitskaya and Gregory, 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2015). Teachers play a critical role in facilitating such activities by eliciting and guiding students’ critical thinking and reasoning in ways that build toward deeper conceptual understandings.

Developing student-centered teaching skills is both a goal and a challenge for pre-service, novice, and experienced teachers (Von Esch and Kavanagh, 2018; Sedova et al., 2016). At the core of this challenge is the fact that such teaching requires adaptive expertise to identify and interpret significant indicators of student learning, recognize pedagogical problems or challenges as they arise, and flexibly reason through and enact teaching moves contingent on students’ emerging learning needs and targeted goals (Bransford et al., 2005; Ghousseini et al., 2015). Professional learning that pairs teachers’ conceptual knowledge development with opportunities to apply this knowledge to resolve authentic problems is widely seen as critical for developing adaptive teaching expertise (Kavanagh et al., 2020). This research highlights the importance of developing teachers’ pedagogical reasoning skills, i.e., how they notice, interpret, and make decisions as they navigate dynamic classroom interactions. In this vein, many researchers have emphasized the role of professional learning facilitators for eliciting and scaffolding teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in ways that align with student-centered goals and principles (Horn and Little, 2010). Guidance on effective professional learning conversations, for example, emphasizes orienting teachers to notice and interpret evidence of student thinking as they reflect on classroom video and other artifacts (Sherin and Van Es, 2009) and supporting teachers to engage in rehearsals and thought experiments around the impacts of alternative teaching decisions (Munson et al., 2021).

Though researchers widely agree that engaging teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in professional learning is a core driver of adaptive expertise (Lefstein et al., 2020b), research on the specific nature of these processes and how they can be consistently supported in teacher education and professional learning is relatively nascent. More specifically, there is a lack of detailed guidance on how those who design and facilitate teacher learning (e.g., teacher educators, mentor teachers, and instructional coaches) can scaffold teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in ways that advance specific goals and competencies needed for student-centered teaching (Kennedy, 2016; van der Linden et al., 2022). Such a lack of clarity and specificity has contributed to long-standing problems in the field, including high variation in the effectiveness of professional learning both within and across program designs and instantiations (Garrett et al., 2019; Kraft et al., 2018; Major and Watson, 2018).

This article aims to contribute insight into this issue by describing in depth one professional learning routine for developing adaptive teaching expertise, termed Mental Simulations for Teacher Reflection (MSTR). Prior mixed-methods research revealed MSTR to be a key factor distinguishing between the work of highly effective instructional coaches and coaches whose teachers showed very low levels of growth in instructional quality (Walsh et al., 2023). The present study builds on this work by exploring in greater depth the aspects of MSTR that make it an effective routine for developing adaptive teaching expertise. Specifically, we elucidate in detail how a ‘high-quality’ MSTR routine unfolds in practice—i.e., in a way that engages and scaffolds critical processes for advancing adaptive teaching expertise.

Our aim is to provide insights that have the potential to inform the work of teacher learning facilitators as they utilize reflective dialogue to develop teachers’ adaptive expertise in practice-based learning contexts. While the present study explores aspects of a high-quality MSTR routine in the context of an instructional coaching program for in-service teachers, we see MSTR as applicable to other contexts including pre-service and novice teacher mentoring (Caven et al., 2021; Nagro, 2022; Orland-Barak and Wang, 2021), video clubs and lesson study (Sherin and Van Es, 2009; Bakker et al., 2022); rehearsal and debrief discussions (Baldinger and Munson, 2020; Kazemi et al., 2016), and simulation-based learning environments (Codreanu et al., 2020; Eldred-Evans et al., 2013; Dieker et al., 2014).

Research background

Integrating theory and practice in teacher learning: the role of adaptive expertise

Teachers often struggle to make effective use of pedagogical theories and frameworks (Resnick et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2025). This issue reflects the long-standing problem of finding an appropriate balance between theory and practice in teacher learning, also known as the “knowing-doing gap” (Kennedy, 2016). On the one hand, the movement towards “practice-based” approaches has aimed to “move teacher education closer to the work of teaching” in response to a perceived lack of practical guidance for novice teachers once they enter the classroom (Zeichner, 2012, p. 377). On the other hand, this renewed focus on practice has spurred fresh concerns about an under-emphasis on the “theory” aspect of teaching, resulting in a de-complexification of teaching into discrete sets of classroom routines and procedures (Kennedy, 2016; Philip et al., 2019; Zeichner, 2012).

The challenge, then, is to figure out how to help teachers iterate between theory and practice in the development and application of their pedagogical knowledge. This challenge is further amplified by ambitious teaching approaches that center students—their voices, ideas, and reasoning—at the heart of classroom activity. Such student-centered approaches subvert traditional expectations for teacher learning that primarily involve the mastery and efficient execution of classroom routines. Rather, they require a different way of organizing and applying pedagogical knowledge to achieve a balance between innovation and efficiency in teaching practice—a collection of competencies known as adaptive teaching expertise (Bransford et al., 2005).

At the core of adaptive teaching expertise is what Philip et al. (2019) terms “principled improvisation”—i.e., the ability to identify critical instructional details, interpret those details through the lens of relevant pedagogical concepts and principles, and make flexible judgments based on these insights and problem conditionalities (Bransford et al., 2005; Lefstein et al., 2020b; Philip et al., 2019). Adaptive teaching experts develop their knowledge of “the how”—i.e., the various teaching moves, routines, and techniques for achieving specific learning goals—in tandem with the conceptual knowledge—i.e., pedagogical frameworks and principles—that inform the “when” and “why” of their use (Hatano and Inagaki, 1986). Through deliberate practice (Ericsson, 2008), this knowledge becomes increasingly elaborated and integrated into a network of conceptual resources that is both expansive and finely differentiated (Bransford et al., 2005). Similarly, in applying this knowledge, adaptive experts exhibit cognitive flexibility to consider multiple alternative interpretations of what a problem case or scenario represents and formulate and test alternative hypotheses for resolving it (Crawford et al., 2005).

Developing adaptive teaching expertise is a steep challenge. Teachers are often unprepared to organize and facilitate their instruction around student-centered principles because their own school experiences, training, and contexts in which they work tend to be shaped by more traditional forms of teaching (Fives and Buehl, 2016). Moreover, developing the kind of deliberative and flexible reasoning and problem-solving skills needed for adaptive teaching expertise requires considerable time and effort. Absent skilled guidance, teachers are unlikely to effectively develop these competencies in a timely and efficient manner. Particularly for pre-service and novice teachers, it is extremely difficult to engage in these high-level cognitive processes while simultaneously learning how to manage all of the complicated tasks and dynamics within their new classrooms. Similarly, for in-service teachers, it is often the case that they do not receive adequate high-quality professional learning that is sustained over time and squarely focused on supporting their instructional growth (as opposed to, e.g., administrative tasks or other logistics). In both cases, teachers need to be supported to develop their pedagogical reasoning skills to apply student-centered pedagogical principles in practice.

Practice-based reflection as a context for developing teachers’ adaptive reasoning and problem solving

Practice-based professional development in which teachers try out new teaching methods, reflect on artifacts of their instruction (e.g., videoed lessons and student work), and use what they learn to refine their practice is one key approach for making student-centered theoretical frameworks more useful to teachers in practice (Ball and Cohen, 1999; Borko et al., 2008; Greeno et al., 1996). As noted above, adaptive expertise requires an integrated approach to developing conceptual and procedural knowledge. Eliciting and scaffolding teachers’ pedagogical reasoning as they make sense of the purposes, impacts, and effectiveness of their teaching moves on student learning is widely seen as a key bridge for this learning (Horn and Kane, 2015; Kavanagh et al., 2020; Meneses et al., 2023; Grossman et al., 2009b). Pedagogical reasoning develops adaptive expertise when teachers make connections between the specifics of their instructional interactions (e.g., teaching moves; student responses and learning goals) and more generalized principles and patterns that persist across lessons (e.g., supporting students’ active learning; addressing student misconceptions) (Walsh and Schunn, 2025; Correnti et al., 2021; Horn and Little, 2010).

Reflection has long been considered a key driver for developing teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, reasoning, and practice (Rodgers, 2002). In line with Dewey’s (1933) foundational work, we conceptualize reflection as a form of “disciplined inquiry” comprised of purposeful and rigorous thought processes. Reflection is purposeful in that it is done with the intention of acquiring a deeper understanding of the nature of a situation or phenomenon and how one should (inter)act within it—i.e., there is a recognized gap between one’s “current state” (i.e., an incomplete understanding or uncertainty) and “desired state” (i.e., greater clarity and insight). Reflection is rigorous in that it follows a methodical trajectory in moving from the “current” to the “desired” state. This trajectory resembles hallmarks of the scientific method, including naming the problem or question that arises from an experience, generating potential explanations, and forming and exploring alternative hypotheses (Dewey, 1933; Rodgers, 2002).

Schön (1983) built on Dewey’s work to further articulate the relationship between teacher reflection and practice in terms of past (“reflection-on-action”) and future (“reflection-for-action”) interactions. Reflection-on-action involves retrospective inquiry into prior teaching interactions: what happened, why, and why was it significant for student learning? Reflection-for-action involves prospective inquiry into future teaching interactions. Such inquiry is often focused on lesson planning, e.g., evaluating a teacher’s plan for implementing and sequencing tasks for an upcoming lesson. Another version of reflection-for practice, one that is especially relevant for the present study, involves applying insights from reflection on past events to (re)consider alternative teaching moves, think counterfactually about potential outcomes, and weigh the merits of alternative scenarios (van der Linden and McKenney, 2020; Keller et al., 2022).

Importantly, teachers do not automatically learn from reflection on their teaching. Facilitators and other resources (e.g., protocols, learning guides) play a critical role in scaffolding productive teacher reflection around their instruction. Much research has shown that teachers often struggle to notice and interpret student thinking during reflection and tend to make quick judgments about their teaching rather than reason in-depth about the impact of their choices (Sherin and Van Es, 2009; Sun and Van Es, 2015; Tekkumru-Kisa and Stein, 2014). Research on professional development programs centered around videoed lessons, for example, highlights the key role facilitators play in orienting teachers’ attention to evidence of student thinking and encouraging critical inquiry into the effectiveness of their teaching choices (Walsh et al., 2020; Walsh and Matsumura, 2025; Sedova et al., 2016; van Es et al., 2014; van der Linden et al., 2022). Studies of teacher education programs similarly emphasize the critical role of teacher mentors (sometimes referred to as field supervisors) for supporting pre-service teachers to reflect on their teaching choices relative to core pedagogical theories and concepts taught in their teacher education programs (Leko et al., 2023; Nagro, 2022). The critical point is that, similar to ambitious student learning, teacher learning facilitators play a central role in scaffolding teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in ways that support robust rather than superficial change in their conceptual understandings and teaching practices.

Theoretical framework: mental simulations for teacher reflection (MSTR)

In our prior research (described in the following section), we identified a key discursive pattern of highly expert mathematics and literacy coaches termed Mental Simulations for Teacher Reflection (MSTR). Rooted in cognitive research, mental simulations are a particular kind of “what if” reasoning that aims to build knowledge and predictive ability through data-driven forward reasoning (Christensen and Schunn, 2009; Landriscina, 2015). Mental simulations involve many markers of adaptive expert reasoning and problem solving, including establishing an informed representation of a problem scenario, hypothesizing the possible or likely outcomes given alternative conditions or actions, and using these insights to consider the viability and merits of alternative strategies (Christensen and Schunn, 2009; Price et al., 2021; Trickett and Trafton, 2007). In teacher learning, a growing line of research has focused on comparable activities such as thought experiments and rehearsals that similarly emphasize adaptive reasoning processes such as exploring alternative pathways and projecting student needs and responses (Lampert et al., 2013; Munson et al., 2021; Baldinger and Munson, 2020). Notably, there is a strong overlap between these activities (i.e., mental simulations, thought experiments, and rehearsals) and the core principles of “representation, decomposition, reflection, and preparation to enact” (Grossman et al., 2009a) that are widely promoted in the literature on practice-based pedagogies (Kavanagh et al., 2020).

Situated within this research space, MSTR is comprised of three components that embed and sequence adaptive expert reasoning and problem-solving processes within a teacher learning routine to identify the nature of the pedagogical issue or problem (i.e., “Establishing Ambiguities”) and generate and reason through alternative pedagogical moves for clarifying and/or resolving it (i.e., “Proposing Alternative Moves” and “Weighing Alternative Moves”). As we highlight in the following sections, each MSTR component incorporates critical aspects of adaptive expert reasoning and problem solving that collectively build upon and iterate between one another. Thus, as we have argued in our prior work (Walsh et al., 2023), mental simulations can only be realized (or identified as such) when all three components are present in a professional learning conversation. Finally, we note that although our below descriptions of MSTR are situated in a one-to-one instructional coaching context, we do envision these components and processes as more broadly applicable to other professional learning designs that feature facilitated reflection in one-to-many formats (e.g., video clubs or other kinds of collaborative teacher learning groups).

MSTR component 1: establishing ambiguities

For the first MSTR component, Establishing Ambiguities, the coach and teacher iteratively discuss and refine a shared understanding of the pedagogical “problem space,” or the specific way in which a pedagogical issue or problem is identified and interpreted in reflective discussion, including which situational details are highlighted (or conversely, obscured) and their perceived significance (Babichenko et al., 2021; Coburn, 2006). This component involves explicitly problematizing an aspect of teaching in which there is a degree of uncertainty related to whether a student learning goal was achieved (or likely to be achieved) and how to achieve that goal. Problematizing in this context involves drawing attention to important situational details and raising questions about their meaning relative to broader pedagogical issues and principles. For student-centered teaching, these details should involve evidence related to advancing students’ conceptual learning goals, e.g., how a teacher’s questions shaped students’ opportunities to explain their reasoning (Sherin and Van Es, 2009). Similarly, interpretations of their significance should be rooted in a constructivist learning framework to be useful for developing adaptive teaching expertise. For example, a teacher could frame evidence of student misconceptions in terms of an opportunity for students to challenge each other’s claims with text evidence. By contrast, this same situation could be framed in ways not likely to support adaptive expertise, e.g., as a problem to be quickly corrected or as a reflection of students’ innate ability or “smartness” (Babichenko et al., 2021; Walsh and Schunn, 2025).

We note that our use of the term “ambiguity” applies to two kinds of situations that are central to teachers’ learning of student-centered instruction. The first refers more broadly to situations that involve high levels of subjectivity, i.e., when there are multiple possible interpretations or action possibilities that could reasonably apply (Ko and Yang, 2014). This kind of ambiguity reflects the complex and dynamic nature of student-centered teaching: in any one interaction, there are multiple decision points to be negotiated contingent on students’ extemporaneous ideas, developing thinking, and varied learning needs (Loughran, 2019; Lefstein et al., 2020b). The second kind of ambiguity refers more narrowly to situations where there is a specific instructional problem—e.g., when there is a discrepancy between an intended student learning goal and observed or anticipated outcomes—and there is some uncertainty related to the nature of the problem itself and/or effective strategies for resolving it (Trickett et al., 2009).

We distinguish between these two kinds of ambiguous situations to highlight two important, interrelated aspects of developing adaptive expertise in this context. Specifically, the fundamental uncertainty involved in student-centered teaching calls for teachers to consider multiple alternative possibilities rather than assume only one interpretation of a situation or means of responding is the “correct” choice (Loughran, 2013). Similarly, adaptive problem solving requires teachers to effectively identify discrepancies between learning goals and outcomes and interpret them in a way conducive to improving practice (Lampert, 2010). These skills also align with adaptive expert learning and problem-solving processes more broadly: Adaptive experts regularly question and revise their existing assumptions (Bransford et al., 2005) and adapt how they apply their disciplinary knowledge in light of different problem conditionalities (Crawford et al., 2005; Mosier et al., 2018).

In the early stages of a coaching conference, a coach might launch this discussion by offering an initial interpretation of the broader pedagogical issue represented by a particular lesson scenario, either planned (in the case of a pre-lesson conference) or actualized (in the case of a post-lesson conference). Importantly, though this initial “ambiguity statement” provides the context for launching the ensuing mental simulation discussion, it may evolve or shift over time as other issues and understandings are raised (a point we will return to in the Results section involving Excerpt 4).

MSTR component 2: proposing alternative moves

The second MSTR component, Proposing Alternative Moves, involves the coach and teacher considering a range of potential alternative teaching moves for addressing an established ambiguity. Proposed alternatives can draw on a range of possibilities in terms of topic (e.g., posing questions or selecting instructional tasks), specificity (e.g., specific question phrasings vs. question “types”), and temporality (e.g., planning moves for an upcoming lesson or hypothesizing alternatives based past events).

To support adaptive expertise, it is important to engage teachers’ thinking about specific actions that can be instantiated in future lessons, e.g., how they will phrase a particular question or detailed steps for implementing a task. Such specificity is especially important for the efficiency aspect of adaptive expertise. That is, teachers need to be equipped with specific and actionable (as opposed to general or vague) potential teaching moves that can be readily deployed in practice (Walsh and Schunn, 2025). Moreover, having a variety of proposed alternative moves, or having a proposed alternative move articulated in a variety of ways, is important for building teachers’ repertoire of moves they can draw upon in case a specific move does not work. Such variety is especially important for the flexibility aspect of adaptive expertise—i.e., an instructional move does not become rigidly linked to a learning or problem situation and vice-versa (Walsh and Schunn, 2025). In a coaching conference, this component might be initiated by the coach prompting the teacher to generate specific ideas for how to approach an established ambiguity that they then jointly weigh in the third MSTR Component, Weighing Alternative Moves.

MSTR component 3: weighing alternative moves

For the third MSTR component, Weighing Alternative Moves, the coach and teacher systematically consider the relative merits of the proposed alternative moves, including discussing how outcomes might vary based on differing student learning needs and goals. This phase of the discussion involves engaging teachers’ reasoning about: (1) which alternatives are more or less viable or valuable given a particular lesson context; (2) reasons why (or for non-selected alternatives, why not) proposed alternatives are useful for advancing student learning goals; and (3) how selected alternatives will be specifically enacted and utilized in subsequent lessons. A coach could use a variety of strategies, such as role play and rehearsal, to elicit, scaffold, and model these reasoning processes in reflective dialogue.

This MSTR component builds on expertise research that suggests reasoning through the hypothetical impacts of alternative decisions and using these insights to make selections is a core mechanism for developing adaptive expertise (Ericsson, 2006). Specifically, adaptive experts tend to have well-elaborated and finely differentiated (i.e., contextualized) understandings of core disciplinary concepts, issues, and their variations in situ, which in turn supports more flexible and precise reasoning and problem solving in practice (Bransford et al., 2005; Feltovich et al., 1997). Applied to teacher learning, the goal of this component is therefore to build teachers’ knowledge and reasoning skills that enables them to identify what is needed (and conversely, what is not needed) in a particular situation and make an informed choice in response to contextual demands—i.e., the conditionalities of a specific problem scenario or case.

Weighing builds on and extends the conceptual work of the first two MSTR components in two key ways. First, weighing involves iterating across all MSTR components—i.e., revisiting and potentially revising the established ambiguity and potential alternative moves in addition to weighing their relative merits. Specifically, the weighing process involves making explicit the reasons and assumptions that drive a teacher’s pedagogical decision-making, which can in turn lead to new insights about the nature of the problem itself (e.g., what led to a particular outcome or its significance for student learning) and therefore the kinds of alternative moves needed to address it. This iterative process is also more generally important for maintaining coherence among a teacher’s understanding of the problem, what possibilities are available, and how to make that choice.

Second, the process of weighing alternative moves in a professional learning discussion is not just about solving one particular problem; rather, it is about building the kind of knowledge and reasoning skills that will help teachers resolve future problems. As noted previously, adaptive teaching expertise relies on developing an integrated base of conceptual and procedural knowledge to support effective problem solving in complex circumstances (Schwartz et al., 2005). The Weighing component of MSTR supports this learning by enabling teachers to make iterative connections across different levels of generalizations (i.e., specific teaching moves, problem scenarios, and principles) and problem conditionalities (i.e., emergent student learning needs and lesson goals). By systematically weighing alternative teaching moves in connection to the varying teaching principles and conditionalities that guide their use, teachers can build knowledge of the “what” (declarative) the “why” (conceptual) the “how” (procedural), and the “when” (conditional)—precisely the kind of knowledge organization and development needed for adaptive expertise (Carbonell et al., 2014; Hiebert et al., 2007; Munson et al., 2021). In other words, by further developing teachers’ contextualized knowledge of how different teaching moves would apply in different kinds of situations, teachers’ declarative knowledge of the teaching moves themselves are elaborated—i.e., building details and variations within the repertoire of moves they can deploy in any given situation (Walsh and Schunn, 2025). In a coaching conference, this discussion might be initiated by the coach prompting the teacher to explain how different alternative talk moves might result in a different student response or outcome, followed by a systematic analysis of their relative merits.

Overview of prior MSTR research

MSTR grew out of a larger research project to conceptualize, study, and embed robust teacher learning mechanisms within two math and literacy coaching programs developed at the Institute for Learning at the University of Pittsburgh. These coaching programs featured a content-focused-coaching approach to support teachers’ implementation of ambitious student-centered practices in their upper elementary and middle school math and literacy classrooms (see Correnti et al., 2021; Matsumura et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2023 for more details). Empirical research on MSTR thus far has pointed to two key takeaways that motivate the purpose and aims of the present study. First, MSTR appears to be a pervasive, embedded practice of highly effective coaches. Results from analyses of the math coaching program, for example, showed that high-growth1 coaches spent significantly more time engaged in mental simulations (about 35% of the total discussion across four coaching cycles) compared to low-growth coaches (about 13% of the total discussion across four coaching cycles). In other words, the coaches whose teachers showed the highest instructional quality growth2 curve over the course of the intervention were far more likely to incorporate mental simulations in their conversations with teachers compared to their low-growth counterparts. Second, there is emerging evidence that the quality of the conversation related to each MSTR component can vary significantly. Supplemental qualitative analyses from the same study, for example, indicated that even when the low-growth coaches implemented all MSTR components, the quality of their execution was significantly lower compared to the high-growth coaches (Walsh et al., 2023).

Importantly, the training provided to coaches did not explicitly incorporate the MSTR framework or mental simulations, suggesting that MSTR captured an implicit component of highly effective coaches that needs more explicit attention for all coaches to implement more consistently. Moreover, MSTR was observed across phases of the coaching cycle—i.e., in lesson planning and post-lesson reflection—and in the context of both video reflection and debrief discussions, indicating its pervasiveness across time (i.e., prospectively and retrospectively) and reflection formats. Thus, while not constituting all of what highly effective coaches do, MSTR captures a primary aspect of their reflective discussions with teachers, making it particularly important to specify in detail how MSTR components work and what constitutes effective forms.

Present study overview and research questions

In summary, prior empirical work indicated that MSTR comprised a significant portion of what expert coaches do in their conversations with teachers. However, more qualitative work is needed to decompose expert enactments of MSTR to provide guidance on how the routine can be effectively applied in professional learning settings. To this end, the aim of the present study is to provide greater detail and clarity around how MSTR supports developing adaptive teaching expertise by identifying the detailed subcomponents involved in each MSTR component and illustrating how they come together in an expert-facilitated enactment of MSTR. We are specifically guided by the following research questions:

1a) What are the subcomponents of Establishing Ambiguities?

1b) How are Establishing Ambiguities subcomponents implemented in expert practice?

2a) What are the subcomponents of Proposing Alternatives?

2b) How are Proposing Alternatives subcomponents implemented in expert practice?

3a) What are the subcomponents of Weighing Alternatives?

3b) How are Weighing Alternatives subcomponents implemented in expert practice?

Methods

Study context: coaching model overview

Data for the present study were drawn from a larger 3-year video-based literacy coaching intervention to implement a model for student-centered text discussions in 4th and 5th-grade teachers’ reading comprehension lessons. For this intervention, teachers completed a six-week online workshop taken in the fall (October–November), followed by cycles of coaching around teachers’ videoed text discussions (January–May). The workshop aimed to provide teachers with a conceptual foundation for classroom text discussions based on Questioning the Author (Beck et al., 2021) and Accountable Talk (Michaels et al., 2008). Questioning the Author draws on cognitive science research that characterizes reading comprehension as an active process of building a mental representation of text (e.g., Kintsch and vanDijk, 1978). Such discussion is supported by teachers posing open-ended questions and segmenting text read-alouds strategically to allow students to grapple with complex or potentially confusing information. Accountable Talk draws on sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1986) and research in the learning sciences (Bransford et al., 1999) with a focus on teachers holding students “accountable” to rigorous and collaborative reasoning processes as they share and explore ideas. Teachers facilitate these processes through a variety of talk moves including marking and exploring differing interpretations, encouraging students to explain their reasoning with evidence, and supporting students to link their ideas to other students’ contributions and to larger text themes (Resnick et al., 2015). During the workshop, teachers would study the theories underlying these approaches through various activities including analyzing video exemplars and participating in reflection board conversations (see Correnti et al., 2021 for more details). Upon completion of the workshop, teachers were provided with a document that summarized the key dimensions of the instructional model and their associated talk moves. This document was intended to support the coaching process by providing a shared language and framework for joint goal setting and reflection.

For the coaching phase, teachers engaged in multiple cycles of lesson planning (pre-lesson conference), implementing and videoing their lessons, asynchronous written reflection (online) and synchronous reflective dialogue (post-lesson conference) with one expert coach. For the pre-lesson conference, the coach and teacher would discuss a plan for an upcoming lesson through the lens of the instructional model dimensions the teacher had chosen to focus on for that cycle (e.g., Accountability to Rigorous Thinking; posing open-ended questions). After the teacher recorded and submitted the lesson video, the coach would then select three video clips (approx. 2–3 min long each) keyed to the teacher’s learning goals. During this process, the coach aimed to select one clip showing a successful interaction relative to a learning goal (i.e., “segment of achievement”) and two clips that highlighted opportunities for improvement (i.e., “segment of approximation”). The coach would then upload the clips to an online server, along with an open-ended reflective prompt for teachers to provide written responses to for each clip. These written reflections were then used as a basis for the final phase of the cycle, the post-lesson conference, during which the coach and teacher jointly watched and discussed each clip remotely on their computers. The goal of the post-lesson conference (approx. 45 min-to-one hour long) was to support teachers to notice and interpret the link between their discussion choices and students’ thinking opportunities as evidenced in the video, assess these interactions relative to learning goals and principles, and consider how alternative talk moves might be used to achieve better outcomes in similar future situations. Based on a cognitive apprenticeship approach (Collins et al., 1991), the coach would encourage teachers to construct their own interpretations of video and provide appropriate scaffolds (e.g., eliciting teacher ideas, modeling evidence-based reasoning) to assist teachers as needed (see Correnti et al., 2021; Walsh and Matsumura, 2025 for more details).

Data sources

For the present study, we focused our analysis on transcripts of teachers’ post-lesson coaching conferences from the second year of the study. The coaching was facilitated by one expert coach who co-developed the coaching model. The coach had over 30 years of experience in public education as a teacher, literacy coach, and designer of professional development experiences for school practitioners. Teachers in this sample (N = 6) each completed at least three coaching cycles in the winter and spring of 2018, worked in one of two Northeastern U.S. school districts that served primarily low-income students (respectively, 98 and 71% of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch), had an average of 17.5 years of teaching experience overall, and 8.4 years teaching at either the 4th or 5th grade level. Notably, prior analyses indicated that these teachers had all improved in their pedagogical reasoning and classroom text discussion quality over the course of the coaching (Walsh et al., 2020; Correnti et al., 2021).

Data analysis

In efforts to better understand how the coach supported this previously documented growth, preliminary analyses had identified mental simulations as a primary component of these coaching sessions (Walsh, 2021). We then engaged in formal coding of all post-lesson conference transcripts in this sample (n = 18 total transcripts). We began by the first author dividing all post-lesson conference transcripts according to areas where the conversation focused on segments of achievement vs. segments of approximation. This resulted in a relatively clean division of each transcript, as the coach would typically begin with a discussion around one segment of achievement before moving on to the two segments of approximation. Subsequent analysis focused only on portions of transcripts related to segments of approximation, which comprised the large majority of the conversation in most cases. We made this choice because these conversations were where MSTR was most applicable—i.e., there was an identified discrepancy or uncertainty regarding what happened in the video and the desired outcome relative to a dimension of the instructional model.

To identify MSTR components within these segments, we used the MSTR coding framework that had been previously validated and applied in the math coaching study (see Walsh et al., 2023). Specifically, the first three authors jointly read through a subset of these transcripts to identify whether and where each MSTR component was present in discussions around each segment of approximation. This process was again relatively straightforward, as the coach followed a semi-structured routine that broadly aligned with each MSTR component (as noted above, the initial conceptualization of MSTR grew out of analyses of this coach’s approach and process, see Walsh, 2021). The first author then coded the remainder of the transcripts to identify MSTR components within each segment of approximation. All of the segments of approximation contained all three MSTR components.

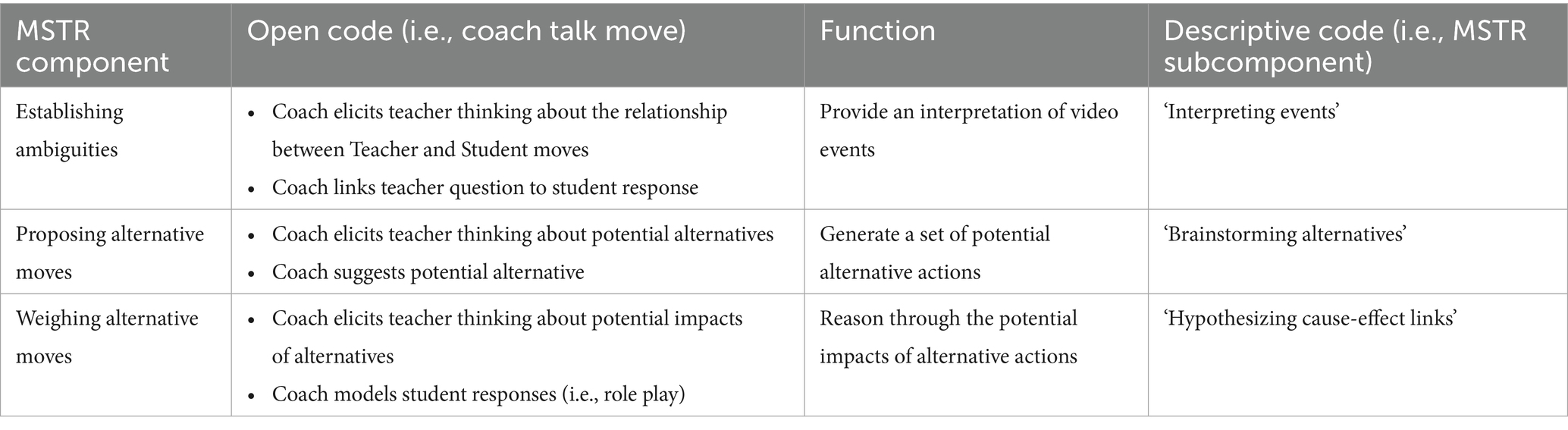

Identifying the finer-grain MSTR subcomponents and their functions, the primary focus of the present study involved several phases of coding analysis. For research questions related to identifying subcomponents (i.e., RQs 1a, 2a, 3a), the first three authors began by jointly analyzing a subset of the sample that included transcripts from different teachers and cycles. The first phase of this analysis involved a combination of open and descriptive coding (Miles and Huberman, 1994) around each transcript segment identified as representing one of the three MSTR components. Specifically, we used open coding to characterize the coach’s talk moves within these segments (e.g., recapping video events; eliciting teacher thinking). We took a holistic approach to determining what counts as a talk move, meaning that talk moves could span from a few words to several lines of text. Because we were only interested in talk moves related to identifying and resolving a pedagogical ambiguity or problem, we excluded talk that was focused on other topics (e.g., logistical issues, unrelated classroom management, or personal matters).

The second phase of analysis involved assigning descriptive codes to each coach talk move based on our assessment of their function within the context of that MSTR component. This involved creating analytic memos to document perceived connections between each subcomponent and their functions related to either problem identification (in the case of Establishing Ambiguities) or resolution (in the case of Proposing and Weighing Alternative Moves). For example, talk moves for “eliciting teacher thinking” could be used for the purpose of “interpreting video events” in the context of Establishing Ambiguities or for the purpose of “hypothesizing cause-effect links” in the case of Weighing Alternative Moves. Notably, these talk moves could range from a bid to evoke or guide a teacher’s response (e.g., eliciting teachers’ thinking about how a discussion question shaped student responses in a video) or take the form of a coach’s direct contribution or suggestion (e.g., the coach explicitly links a student response to a teacher question in video). In this case, the same descriptive code would apply (i.e., “interpreting events”) based on their shared function within that specific MSTR component (see Table 1 for a sample codebook).

To generate our final set of MSTR subcomponents, we then compared segments for each MSTR component to identify co-occurring descriptive codes across transcripts (Miles and Huberman, 1994). We considered descriptive codes to have met the criteria for subcomponent classification if they: (1) consistently linked a family of coach talk moves to a specific function within each MSTR component; and (2) were present in at least one of the two segments of approximation in every transcript. Through our joint analysis, we identified 10 total subcomponents (see Results section), which the first author then assessed in the remaining transcripts. We found that all 10 subcomponents were either highly consistent (i.e., present in both segments of approximation across all transcripts) or very consistent (i.e., present in at least one segment of approximation across all transcripts).

For research questions related to expert enactment of MSTR subcomponents (i.e., RQs 1b, 2b, and 3b), we used an illustrative case study approach (Yin, 2000) to select excerpts that highlighted in detail each of the identified MSTR subcomponents and thus provided a “thick description” of MSTR as a socially-mediated context for learning (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In addition to meeting this criterion, we also sought to select excerpts embedded within a continuous line of discussion (i.e., a vignette) to cleanly show how each came together as part of the broader MSTR routine. Throughout all phases, the coach served as a critical “member check” (Miles and Huberman, 1994). As such, the team would frequently meet to share and discuss their independent coding with the coach and elicit her feedback. Moreover, she significantly guided the vignette selection process and helped refine the narrative analysis around each vignette excerpt.

Results: high-quality implementation of MSTR

In what follows, we begin with an overview of the context for the illustrative vignette. We then present our results in three sections organized around the three main components of MSTR (Establishing Ambiguities, Proposing Alternative Moves, and Weighing Alternative Moves). Specifically, for each respective MSTR component, we begin with a brief description of the subcomponents involved in expert enactment of that MSTR component (RQs 1a, 2a, 5and 3a) followed by a presentation and discussion of the portion of the illustrative vignette that details how they come together for that MSTR component in a coaching conference (RQs 1b, 2b, and 3b).

Overview of the illustrative vignette

The context for the selected vignette excerpts is a post-lesson conference in which the coach (C) and teacher (T) synchronously watched and discussed a video clip from the teacher’s previous lesson. In the video clip, the teacher had posed an open-ended question (“What’s going on here?”) to students during a discussion of the novel “A Long Walk to Water” by Linda Sue Park. In the preceding portion of the text, multiple pivotal events had been discussed, including a predicament in which one of the main characters (Nya) and her family must decide between two potentially perilous options to save the life of her sister (Akeer). In response, students had offered an array of ideas beyond the scope of this specific dilemma that were subsequently overlooked by the teacher, who had wanted to hone students’ focus more narrowly on Nya’s situation. In some of these student responses, there was also evidence of potentially key misconceptions related to larger text themes and events, including apparent confusion related to multiple storylines that centered on the conflict between various ethnic groups and governing factions in South Sudan.

For the online written reflection before the post-lesson conference, the coach had asked the teacher to consider how dialogic talk moves (e.g., pressing for reasoning, inviting students to link ideas) may have been used to respond more productively to students’ ideas and address potential misconceptions. As part of her reflective prompt, the coach had also described some of her observations, including offering some initial inferences about the teachers’ goals and decision-making processes based on what happened in the video clip. To launch the post-lesson conference, the coach reiterates these observations and inferences before re-watching the video with the teacher (as shown in Excerpt 1).

MSTR component 1: establishing ambiguities

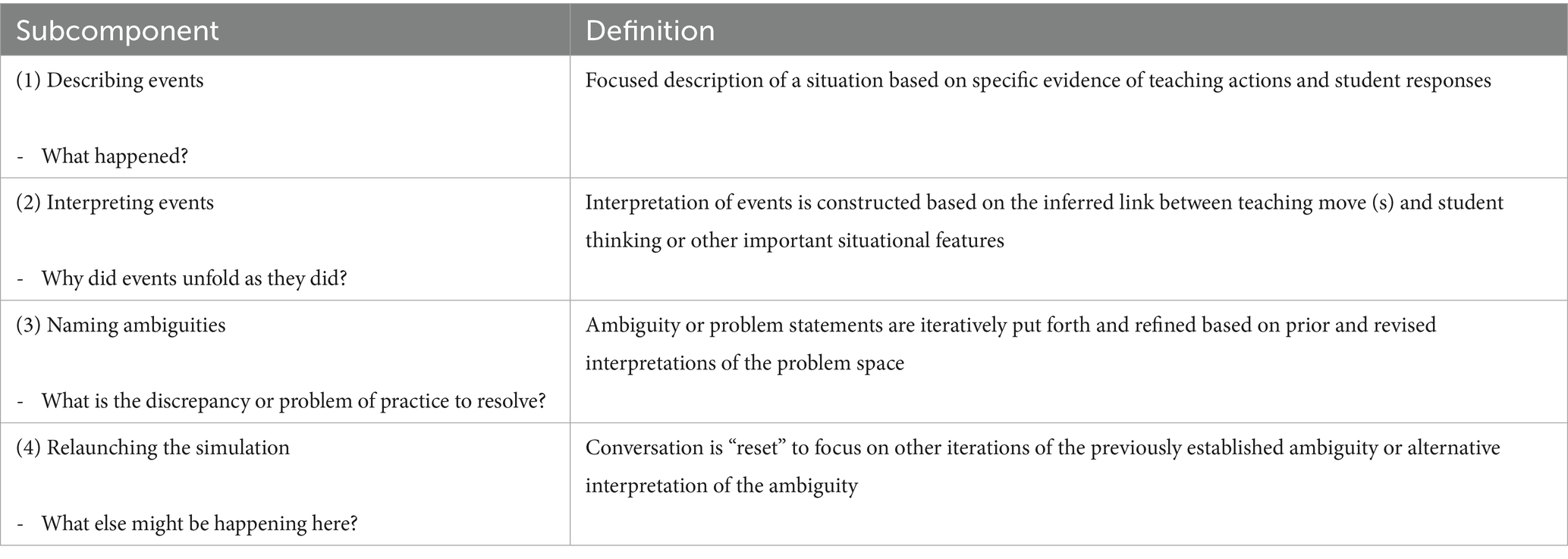

We identified four subcomponents involved in an expert-facilitated enactment of the Establishing Ambiguities component of MSTR (see Table 2 for definitions). The first subcomponent, Describing events, establishes a specific set of situational details to serve as the basis for further reflection and discussion. The second subcomponent, Interpreting events, involves linking these events to a student learning goal through the lens of cause and effect. The third subcomponent, Naming ambiguities, involves connecting this initial interpretation to a broader pedagogical problem or principle that serves as a “launch point” for the ensuing discussion. The final subcomponent, Relaunching the simulation, involves re-initiating the Establishing Ambiguities component where there is a need to “reset” the simulation in light of evolved understandings (e.g., shifts in understanding of the prevailing ambiguity) or to focus on other instructional details and moves that might be relevant to an established ambiguity (see Excerpt 4 at the end of this section).

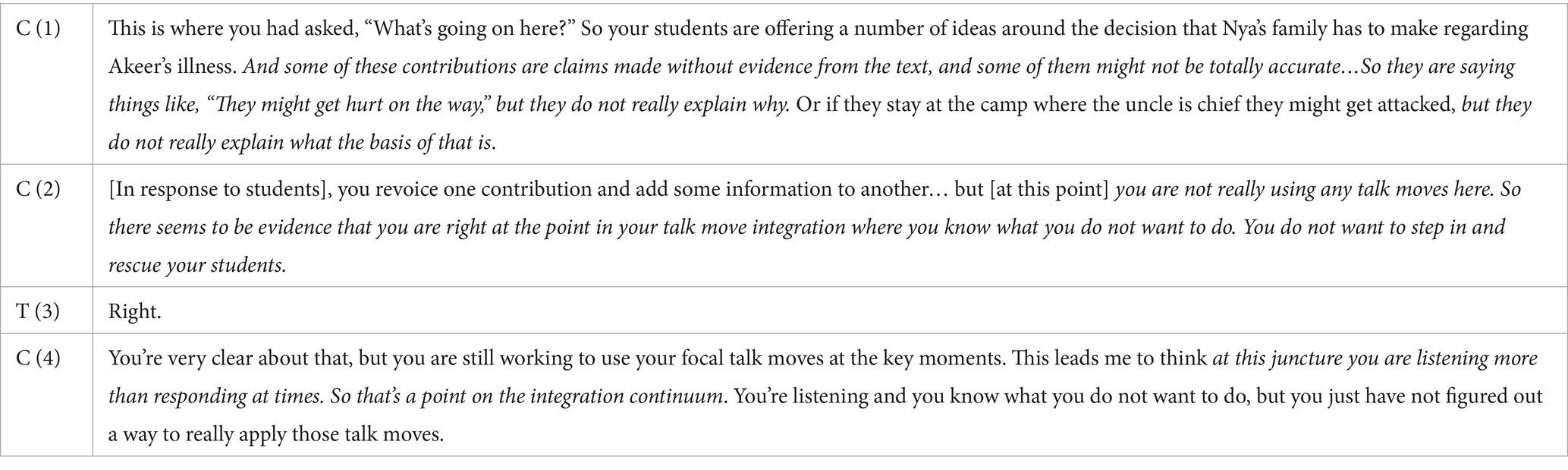

Excerpt 1 illustrates how the coach facilitates each of these Establishing Ambiguities subcomponents to establish a productive problem space for subsequent hypothesizing and simulating of potential alternative talk moves. The topic of the ambiguity is: How to expand on student ideas and address potential misconceptions without constraining student thinking? Note that, in the excerpts, the first column indicates the speaker (C = coach; T = teacher) and the turn number, and italics indicate points of analytic emphasis that will be discussed in the text following the excerpt.

As shown in Excerpt 1, the coach initiates the discussion by Describing the situation using specific video evidence and verbatim statements rather than vague descriptions or recollections (T1: This is where you had asked, “What’s going on here?” So your students are offering a number of ideas…). The coach then Interprets the situation based on established evidence (T2: So there seems to be evidence…you do not want to step in and rescue your students.) Importantly, the coach frames her interpretation in terms of connecting to the teacher’s goals and in-the-moment thinking—abstracting from the specifics of the situation (i.e., the teacher’s non-responsiveness to students) to what they represent as a class of moves that serve a purpose (i.e., maintaining cognitive demand by not ‘rescuing’ students). Finally, the coach Names an initial ambiguity that locates the teacher on a larger continuum of learning—i.e., where she is listening more to students but struggling to respond with talk moves to grow their thinking (T4: This leads me to think at this juncture you are listening more than responding at times…). It’s worth noting that at this juncture, the “Naming ambiguities” subcomponent is not meant to offer a fully-fleshed diagnosis or remedy to the problem at hand—rather, the goal is to offer a first attempt to problematize the situation and set up for the next stage of the simulation.

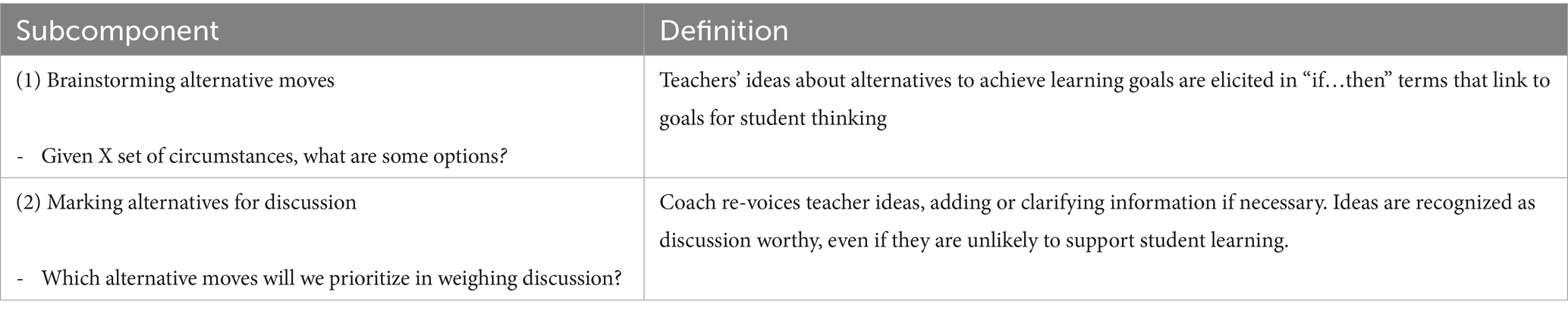

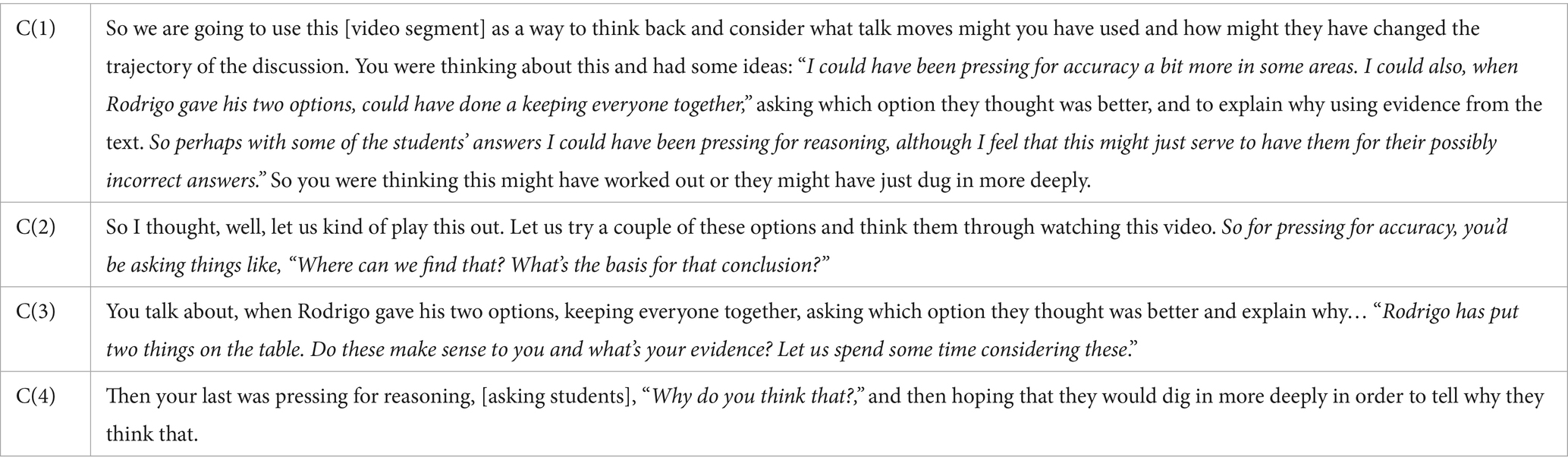

MSTR component 2: proposing alternative moves

There are two subcomponents involved in Proposing Alternative Moves (see Table 3). The first subcomponent, Brainstorming alternative moves, involves generating a set of specific, actionable teaching moves that can be connected to the established ambiguity and targeted pedagogical principle. The second subcomponent, Marking alternatives for discussion, involves reiterating the teachers’ ideas for alternative moves, raising each up to explore in depth.

Excerpt 2 illustrates these subcomponents, picking up from where the previous excerpt for Establishing Ambiguities (Excerpt 1) left off.

In this Excerpt, the coach elicits and revoices the teacher’s initial thinking about potential moves using “if…then” terms anchored in a shared language about specific kinds of teacher moves and student learning goals (T1: [quoting the teacher]… “I could have been pressing for accuracy a bit more in some areas”… So you were thinking this might have worked out or they might have just dug in more deeply.) [Brainstorming]. The coach raises up each teacher suggestion for consideration—e.g., inviting students to weigh ideas (T3: [quoting the teacher]: … “Rodrigo has put two things on the table… Let us spend some time considering these”) and pressing for student reasoning (T4: [quoting the teacher]… “Why do you think that?”…and then [you were] hoping that they would dig in more deeply…) [Marking]. Importantly, the coach raises up these ideas even though, as we illustrate in the following section, the teacher’s initial suggested alternatives (that focused on Rodrigo’s comments) are not ideal relative to the teacher’s broader learning goals and the nature of the other student contributions offered. However, raising up ideas that are not viable or strongly linked to student-centered instructional goals (in addition to ones that are more closely aligned) provides a valuable learning opportunity in the next MSTR component—i.e., Weighing Alternative Moves—where the goal is to support teachers to arrive at their own understanding of whether and why a particular alternative move is valuable (or not) for advancing students’ thinking opportunities.

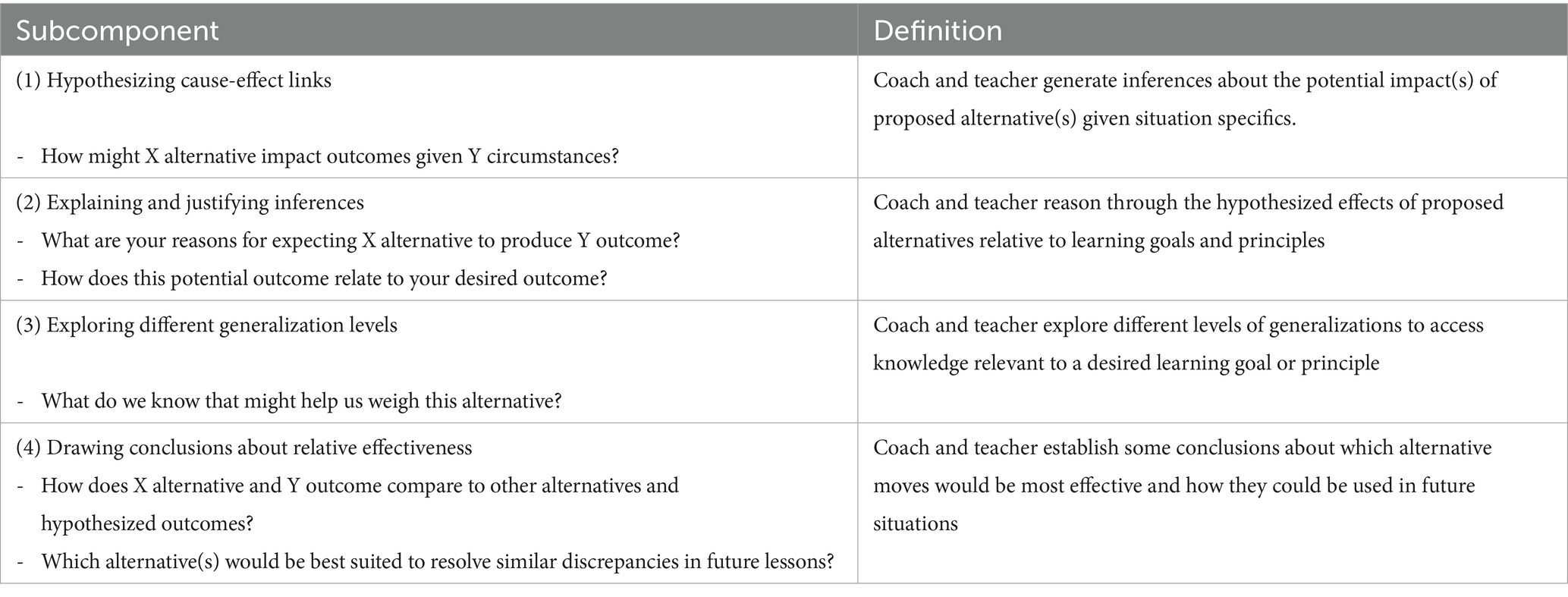

MSTR component 3: weighing alternative moves

As illustrated in Table 4, we identified four subcomponents involved in the expert coach’s enactment of Weighing Alternative Moves. The first subcomponent, Hypothesizing cause-effect links, involves reasoning through selected alternatives to jointly elaborate on a previously established ambiguity. For subcomponent 2, Explaining and justifying inferences, hypothesized impacts of each proposed alternative move are considered relative to targeted learning goals and principles. In this phase, the coach and teacher jointly offer reasons for/against different alternative moves. For subcomponent 3, Exploring different generalization levels, different alternative moves are connected to different kinds of pedagogical problem situations and principles at varying levels of abstraction. For the final subcomponent, Drawing conclusions about relative effectiveness, some conclusions are established about which alternative moves would be most effective for addressing the established ambiguity and advancing learning goals, including specifying how they might be implemented in future lessons.

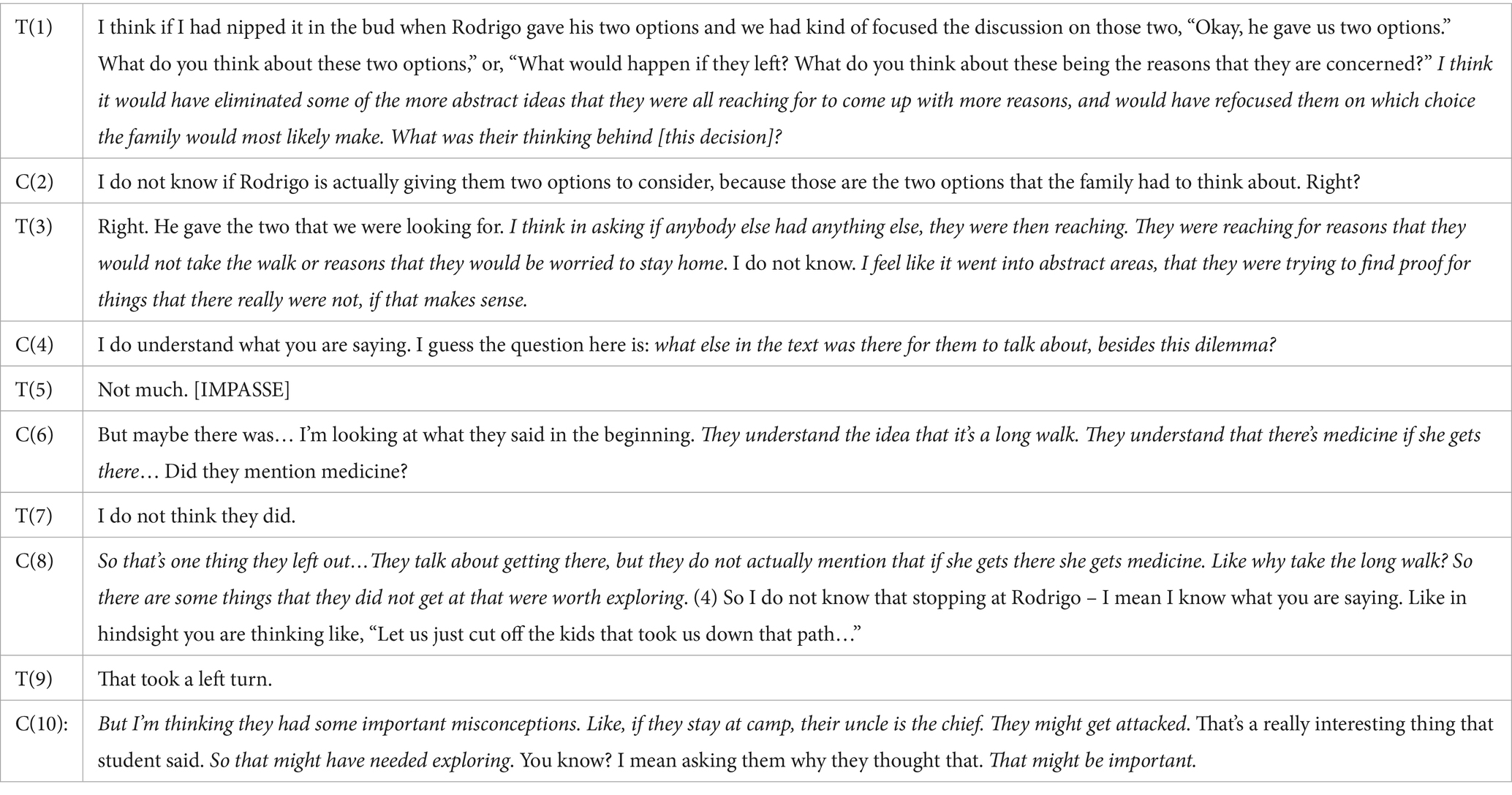

Excerpt 3 begins immediately after the coach and teacher synchronously re-watched the video clip, where the coach had raised up one of the alternatives suggested by the teacher (inviting students to consider Rodrigo’s comments about Nya’s dilemma) to weigh relative to evidence of students’ thinking and her goals for advancing both rigor and accuracy in student discussion.

As shown in Excerpt 3, the teacher began with a well-reasoned inference about the potential impact of proposed alternative move (T1: “Okay, he gave us two options… What do you think about these two options?” I think it would have eliminated some of the more abstract ideas that they were all reaching for to come up with…) [Hypothesizing]. The coach responds with a challenge to the teacher’s initial interpretation—i.e., that Rodrigo had not really generated this idea as those are the two available options stated in text (T2: I do not know if Rodrigo is actually giving them two options to consider…). The teacher then further elaborates her rationale for that choice (T3: He gave the two that we were looking for…I think in asking if anyone had anything else…[students] were trying to find things that really were not…) [Explaining/justifying]. However, as will become clear later in the discussion, this reasoning is based on a premise that is not supported by video evidence (i.e., that students were offering unrelated ideas that would lead the discussion into unproductive territory).

The coach responds by re-orienting the teacher’s thinking (T4: I guess the question here is, what else in the text was there for [students] to talk about, besides this dilemma?) acknowledging the teachers’ reasoning (T4: I do understand what you are saying…) and encouraging her to think about the situation from a different perspective—i.e., that there may be more to talk about than just Nya’s two options, which represents a relatively constrained discussion space [Exploring generalizations]. Importantly, these aspects of how the coach problematizes the teacher’s initial interpretation opens up space for further discussion (rather than, e.g., correcting the teacher or telling her that her thinking is flawed).

However, the teacher’s next response (T5: Not much.) indicates an “impasse” where she does not initially connect with the new line of inquiry put forth by the coach. The coach responds by offering an alternative perspective (T6: But maybe there was… I’m looking at what they said in the beginning. They understand the idea that it’s a long walk…Did they mention medicine?). She continues to elaborate on this idea (e.g., T8: So there are some things that they did not get at that were worth exploring…) and used other facilitation moves such as modeling pedagogical reasoning to call out and interpret other important evidence (T10: But I’m thinking they had some important misconceptions. Like, that if [Nya and her family] stay at the camp, their uncle is the chief [and] they might get attacked…that might have needed exploring. You know?) while also continuing to acknowledge the teachers’ initial thinking (T8: I mean I know what you are saying…) [Justifying/Explaining].

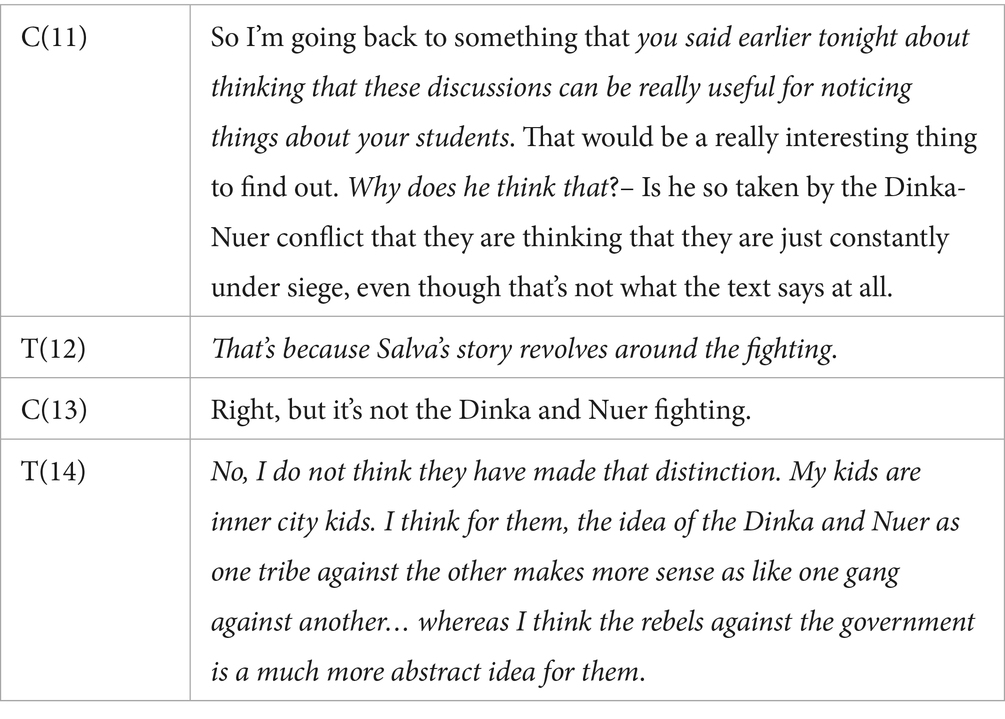

From here, the coach and teacher continue the conversation about student misconceptions, including one student contribution (that had been ignored by the teacher in the video) where the student appeared to be applying an unrelated text storyline about warfare between the Dinka and Nuer tribes in their interpretation of events surrounding another main character, Salva, who was embroiled in a conflict between governing and rebel groups. The ensuing conversation between the coach and teacher is highlighted in Excerpt 4, which immediately followed Excerpt 3.

As shown in Excerpt 4, the coach explicitly connects this specific misconception up to the teacher’s previously stated goals for her teaching (T11: So I’m going back to something that you said earlier… about [how] these discussions can be really useful for noticing things about your students), thereby framing this student’s contribution not just as a misconception that needs to be addressed, but as an opportunity for the teacher to learn about her students [Exploring generalizations]. The teacher then generates an inference about the potential source of the misconception (T12: …because Salva’s story revolves around the fighting…) and re-frames the problem by linking students’ specific textual thinking to a broader issue (i.e., how students’ prior experiences may have primed them to misinterpret Salva’s situation) (T14: No, I do not think they have made that distinction… I think the rebels against the government is a much more abstract idea for them.) [Exploring generalizations]. This reflection in turn sets the stage for a relaunch of the simulation, illustrated in the final vignette excerpt (Excerpt 5).

Relaunching the simulation

As noted previously, at times there is a need to return (or “reset”) the focus of the discussion when initial understandings of the pedagogical problem space have significantly evolved over the course of the MSTR discussion. In these cases, the coach will initiate the final Establishing Ambiguities subcomponent, Relaunching the simulation (see Table 2). Here, Relaunching is appropriate because the joint interpretation of the instructional ambiguity has significantly shifted—i.e., from the teacher’s initial aim to refocus student discussion on Rodrigo’s comments to the exploration of other student ideas and potential misconceptions. Excerpt 5 highlights how the coach relaunches the discussion to support the teacher to explicitly make connections between selected alternative moves and broader principles, challenges, and situations that span beyond any particular lesson or learning goal.

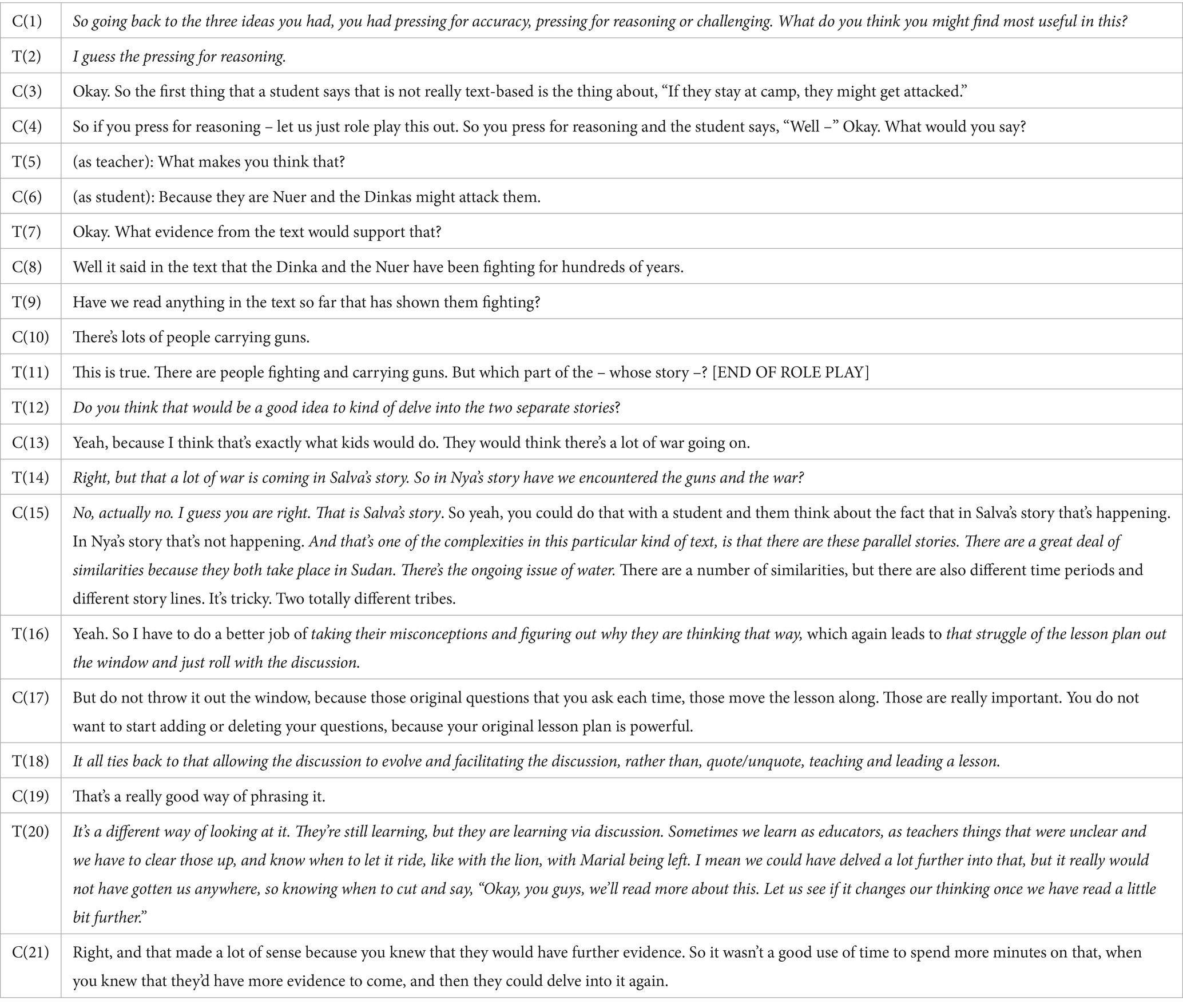

In this excerpt, the coach begins by circling back to the specific proposed alternative moves, digging into the lesson specifics and student dynamics in the proceeding excerpt (T1: So going back to the three ideas you had…What do you think you might find most useful in this [situation]?) [Brainstorming]. Notably, the teacher offers in response an alternative that is non-specific and unelaborated (T2: I guess the pressing for reasoning). In response, the coach initiates a ‘role play’ to encourage the teacher to instantiate her learning goals in concrete action—i.e., specific question phrasings rather than just general question ‘types’—and to weigh the proposed alternative relative to students’ thinking (T4: … let us just role play this out. So if you press for reasoning and the student says, “Well…” Okay. What would you say?) [Marking]. As illustrated in Ts 5–11 of the excerpt, the ensuing role play conversation engages the teacher’s thinking about her specific questions and rejoinders and their impacts from the perspective of how a student might infer and think about text [Hypothesizing]. Notably, this conversation leads the teacher to inquire about an aspect of the text she had not before considered (T11: This is true. There are people fighting and carrying guns. But which part of the – whose story –?” [Teacher stops role play and queries the coach]: Do you think that would be a good idea to kind of delve into the two separate stories?). This question in turn prompts a productive new line of inquiry that includes rich insight and a challenge to the coach’s initial interpretation (T14: Right, but that a lot of war is coming in Salva’s story. So in Nya’s story have we encountered the guns and the war?). The coach then acknowledges the teacher’s point (T15: No, actually no. I guess you are right. That is Salva’s story…) and, notably, takes up the teacher’s line of inquiry by connecting it up to a larger disciplinary concept—i.e., parallel storylines as a component of rich texts—that applies across lessons (T15: …And that’s one of the complexities of this particular kind of text…) [Exploring generalizations]. The teacher then makes a connection between this particular situation—i.e., a student confusing multiple character storylines and sources of conflict—to another pedagogical problem and principle—i.e., using student misconceptions as a tool for growing their learning (T16: Yeah. So I have to do a better job of taking their misconceptions and figuring out why they are thinking that way…) and adapting lesson plans in light of students’ discussion trajectory (T16: …which again leads to that struggle of the lesson plan out the window and just roll with the discussion…) [Exploring generalizations + Drawing conclusions3].

The discussion proceeds with the coach once again leveraging and extending the teacher’s comment, offering a slight pushback to her assertion (T17: But do not throw [your lesson plan] out the window…) in a way that also affirms the teacher’s initial ideas (T17: You do not want to start adding or deleting your questions, because your original lesson plan is powerful). This, in turn, prompts the teacher to refine her initial interpretation, offering a more sophisticated reframing of the issue in terms of a key learning principle (T18: It all ties back to that allowing the discussion to evolve and facilitating the discussion, rather than, quote/unquote, teaching and leading a lesson.) [Exploring generalizations]. Finally, the discussion concludes with the teacher offering a rich summative statement that links together alternative teaching moves, goals, and content across levels of generalization (T20: It’s a different way of looking at it. They’re still learning, but they are learning via discussion. Sometimes we learn as educators…we have to [know when to] clear those up, and know when to let it ride, like with the lion, with Marial being left. I mean we could have delved a lot further into that, but it really would not have gotten us anywhere, so knowing when to cut and say, “Okay, you guys, we’ll read more about this. Let us see if it changes our thinking once we have read a little bit further.”) [Exploring generalizations + Drawing conclusions].

Figure 1 summarizes the overall trajectory of how coach and teacher constructed increasingly sophisticated understandings of the pedagogical problem space across MSTR components.

General discussion

In this article, we presented the detailed components and subcomponents of Mental Simulations for Teacher Reflection (MSTR) as a framework for conceptualizing and implementing an effective routine for developing adaptive teaching expertise. Specifically, we describe in detail the pedagogical reasoning processes that support adaptive teaching expertise within each MSTR component, identified the finer-grain subcomponents that help elicit and facilitate their engagement, and presented an illustrative vignette that exemplifies their instantiation in a coach-teacher professional learning conversation. By describing and illustrating in-depth the conceptual and practical dimensions of one well-supported learning mechanism (i.e., mental simulations) in a teacher learning context, our aim is to contribute insight into the long-standing problem of the ‘black box’ of effective teacher learning processes (Correnti and Rowan, 2007; Jacob and McGovern, 2015; Osborne et al., 2019).

We see our framework as distinctive in both its flexibility and specificity. First, while MSTR was developed in the particular context of in-service math and literacy teacher coaching, the theoretical principles and mechanisms that inform the framework are applicable to multiple other teacher education settings that foreground teacher reasoning and reflection processes. We see our framework as especially useful for guiding video-based reflection, a practice that is increasingly emphasized in pre- and in-service teacher learning as key to developing teachers’ pedagogical reasoning and integration of formal principles with classroom interactions (Walsh et al., 2020; Nagro, 2022; Leko et al., 2023; Orland-Barak and Wang, 2021; Sherin and Van Es, 2009).

Of course, the particular learning goals and levels of support in a MSTR routine would likely need to be adapted to teachers’ distinctive learning needs. It is reasonable to expect, for example that novice teachers or teachers with little familiarity with an instructional model would need more scaffolding for participating in MSTR (Janssen et al., 2015). In these cases, a coach might need to play a more active role in orienting teachers’ attention to key cause-effect relationships evidence in classroom video (e.g., how their phrasing of a question limited a student’s opportunity to voice their thinking). Similarly when generating and reasoning through potential alternative moves, the coach may need to make more explicit suggestions for what kinds of instructional moves might work and how they might be implemented. Regardless of where teachers are at in their learning trajectory, however, it is important that they are provided the opportunity to engage socially with the complexities involved in identifying and reasoning through context-specific applications of student-centered teaching moves and principles. Our framework is uniquely suited to this purpose.

Second, we highlight the value of our framework for elaborating what an effective mental simulation teacher learning routine “looks like” at multiple levels of context-specificity. Simulation and model-based learning represent a broad area of research (see Seel, 2017 for a review). In cognitive psychology, this research often focuses on theorizing, clarifying, and explicating the cognitive processes of mental simulation as a tool for solving specific problems or tasks (e.g., solving a particular engineering or design issue, Christensen and Schunn, 2009). By contrast, there has been considerably less focus on mental simulation as a mechanism for learning—i.e., as a means to develop the transferable knowledge and skills that comprise a particular domain of expertise. Our framework represents a significant step in elucidating these processes within the domain of student-centered instructional practices which is essential to the design, evaluation and scaling of productive teacher learning environments. When frameworks lack specificity in seeking to be broadly applicable, they provide no actionable guidance. Consider, for example, the context of teacher reflection. Nearly every professional development framework emphasizes the importance of reflection or has as a goal that teachers become reflective practitioners. Still, what it means to be “reflective” often lacks conceptual clarity, which fails to be useful to design (what should teachers be reflecting upon?), scaling (‘how do we train facilitators to support reflection?) or rigorous empirical investigation (what would count as not being reflective?) (Beauchamp, 2015; Gaudin and Chaliès, 2015; Lefstein et al., 2020a).

Lacking specificity is problematic because it can lead to missing important teacher learning processes in reflection, and/or surface-level implementation. For example, attending to evidence of student thinking has been widely promoted in pre-and in-service teacher reflection (Santagata et al., 2021). The importance of linking evidence to pedagogical principles is less commonly understood. Indeed, we have found that coaches are readily able to point out specific moments in a lesson that are problematic (a teacher posing a series of closed questions in response to a “wrong” student answer), but less frequently connect problematic interactions with dialogic principles (why leading students to answers undermines the dialogic principle of students doing the cognitive work in a discussion) (Li et al., 2024). Missing this subcomponent of reflection reduces teachers’ opportunities to form the kinds of “mindful abstractions” that promote knowledge transfer (Walsh and Schunn, 2025; Salomon and Perkins, 1989). Specificity also helps ameliorate surface-level implementation. For example, while the concept of generating and thinking through alternatives is widely cited as important for adaptive teaching expertise (Keller et al., 2022; Munson et al., 2021), these processes can be conducted in surface-level ways. These include, for example, coaches eliciting a single alternative from a teacher and then jumping straight to advice giving rather than encouraging teachers to reason through the merits of multiple alternatives (Walsh et al., 2023) or accepting generic alternative choices. For example, if the coach in our study had not pressed the teacher to go beyond identifying the label of a talk move (i.e., “pressing for reasoning”), the teacher would not have had the opportunity to connect this broader category of student-centered teaching practices to the specific language she would use when responding to student thinking in the moment. In other words, the teacher’s opportunity to develop the integrated knowledge base underlying adaptive expertise would be significantly reduced.

By showing these decision points and unpacking the coach’s reasoning behind them (i.e., in response to the teacher’s thinking and learning goals), we see the illustrative vignette as having particular value for helping facilitators envision and plan how they could conduct a MSTR conversation with teachers. Specifically, because we not only identified important MSTR subcomponents but showed how they came together and were sequenced by an expert coach, the present study could provide a useful “road map” for high-quality enactment. For example, the vignette excerpts for Establishing Ambiguities highlight how the coach’s moves to describe and interpret what happened in the video provided an important basis for connecting to a broader pedagogical problem (i.e., Naming ambiguities). Likewise for Weighing Alternative Moves, the excerpts show a clear progression of reasoning through how a proposed alternative would have impacted a learning outcome (Hypothesizing cause-effect links) in order to make an informed judgment about its potential effectiveness (Explaining and justifying inferences).

To this point, if we conceptualize teacher learning facilitation as its own kind of adaptive expertise, then improving the quality of facilitator training will require going beyond building their knowledge of specific facilitation moves associated with better teacher learning outcomes. Rather, their ability to leverage these facilitation moves effectively will likely be contingent upon having a strong conceptual knowledge of how they function in pursuit of broader learning goals and principles. A strong understanding of the conceptual links that enjoin teacher learning theory and practice—i.e., developing adaptive expertise for teacher learning—is therefore an essential requisite for being a highly effective and responsive facilitator of any teacher learning routine, including MSTR. We argue that our careful description of the theoretical basis for MSTR together with our identification and illustration of the finer-grain subcomponents could serve as a robust tool for building facilitators’ knowledge of teacher learning processes and effective reflection practices.

Finally, we believe the level of specification in our framework is useful for guiding research that provides insights into the quality of teachers’ learning opportunities. Considerable advances have been made in identifying features of effective professional learning programs and activities (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Lefstein et al., 2020b; Powell et al., 2010). Despite these advancements, however, the quality and implementation of teacher education at all points of their career remain stubbornly inconsistent (Caven et al., 2021). For example, research has shown that a significant amount of variation in teacher learning outcomes is explained by coach assignment in some large-scale programs (see, e.g., Walsh et al., 2023; Downer et al., 2009), indicating that even when coaches receive similar training and supports, there is still a wide range of variability in terms of their efficacy working with teachers. Similarly, though high-quality mentorship is widely recognized as essential for supporting new teachers, the field lacks robust theoretical and empirical guidance for how to consistently develop and support strong mentorship practices (Clarke et al., 2014; Kavanagh et al., 2023). The uneven outcomes observed within and across teacher learning contexts often remains under-examined or theorized, leaving unanswered important questions about how and why some facilitators are effective for substantively improving teaching practice and others are not (LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2016). The present study’s detailed explication of an expert-facilitated MSTR routine provides a window into key quality dimensions of professional learning conversations that could be fruitful sites for exploring sources of this variation.

Limitations and future directions

Of course, there are several caveats to consider in the present study. We have presented a detailed qualitative analysis of how MSTR comes together in an expert-facilitated learning conversation with strong grounding in theory for developing adaptive teaching expertise. However, additional empirical work is needed to substantiate these claims further and test them. It might be the case, for example, that some of our identified MSTR subcomponents are more critical than others for developing adaptive teaching expertise, especially as applied to other teacher reflection contexts. Moreover, because MSTR was developed with the goal of supporting teachers’ learning of student-centered teaching practices, our framework and analysis was strongly influenced by theory and research on adaptive expertise. However, other professional learning facilitators might have other strategies, grounded in different frameworks, that could also be successful. Similarly, it may be that MSTR is less suited for teacher learning contexts that promote other kinds of instructional paradigms not focused on student-centered teaching goals and practices or for advancing teachers’ learning of more basic teaching skills and procedures.

Finally, future work is needed to better understand the interactional dynamics and contextual features that facilitate productive MSTR conversations in different learning settings. In this sense, the high level of expertise of our collaborating expert coach, though beneficial for the goals of this study, raises questions about how effectively MSTR could be leveraged more broadly. An important next would involve explicitly training coaches to implement MSTR components and subcomponents to better understand how generalizable and feasible it is to replicate the expert-enacted MSTR practices detailed in this study and what adaptations might be needed. Future investigations are therefore needed to provide insight into: the kinds of conceptual understandings, strategies, and supporting tools necessary to support consistently productive MSTR conversations; the relational dynamics that undergird such conversations; and how MSTR could function as a component of a larger system of norms and practices all of which collectively influence the quality of teachers’ learning across their career.

Data availability statement

The annotated coaching transcripts that formed the basis of this article can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DZ-H: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation (Grant number: 220020525).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^“High-growth” refers to coaches whose teachers showed the strongest improvement; “low-growth” refers to coaches whose teachers showed the least amount of improvement (i.e., their levels of growth scored in the top and bottom third of the sample, respectively).

2. ^Based on IQA (Instructional Quality Assessment) measures of maintenance of cognitive demand and public display of student thinking (see Stein and Kaufman, 2010andRussell et al., 2020for more details).

3. ^Note that ‘Drawing conclusions’ would likely have occurred in the previous segment had a relaunch not been needed.

References

Babichenko, M., Segal, A., and Asterhan, C. S. (2021). Associations between problem framing and teacher agency in school-based workgroup discussions of problems of practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 105:103417. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103417