- 1Department of Educational Psychology, Marburg University, Marburg, Germany

- 2Department of Developmental Psychology, Marburg University, Marburg, Germany

Social status influences various outcomes in the higher education context, such as students’ cognitive and affective well-being. Yet, it is not fully understood to date how it translates into such psychological outcomes. Motivational conflicts arise when two colliding activities compete for resources and cannot be realized at the same time. Students frequently experience such conflicts, which compromise well-being. Since action opportunities depend on social status, the present study examines whether students experience motivational conflicts differently depending on social status and whether this explains impaired well-being of students with comparatively lower social status. While research suggests that different characteristics of students with lower social status are related to aspects of conflict experience, social status has never been assessed as an influential individual factor in motivational conflicts before. In two studies, German speaking university students reported their social status, conflict frequency, conflict reactivity, and well-being in online questionnaires. Structural equation modelling revealed that students with lower social status reported lower academic well-being and partly showed different conflict experiences. However, no mediating effects for well-being could be shown. Implications and the transnational generalizability of findings on social status differences in higher education as well as their applicability at different educational levels are discussed.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, barriers for enrolment in higher educational institutions such as universities have decreased, leading to a more diverse student population in terms of social status (Janke et al., 2024). However, students with lower social status remain underrepresented (Geißler, 2014; Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission e.V, 2017; Bauer, 2022). To describe a person’s social status in society, different approaches prevail: Goudeau et al. (2024) define one’s standing in social hierarchy in terms of access to financial, cultural, and social resources. While some studies use objectifiable indicators of social status, such as a person’s or family’s educational level, occupation and income (Reynolds and Cruise, 2020), subjective social status depicts the “perceived social standing relative to a given social group” (Loeb and Hurd, 2019, p. 153). Both the objective and subjectively perceived position in social hierarchy influence individual’s experiences, behavior, and life paths, which is particularly visible in educational paths (Ostrove and Cole, 2003; Manstead, 2018).

The disadvantage due to students’ social background usually does not end with their access to higher education. Students with lower social status struggle more financially than their higher social status peers and have to work more hours alongside their studies (Rubin et al., 2019). They also tend to take over caring responsibilities for their family members (Covarrubias et al., 2019) and live with their parents longer than their higher social status peers—consequently, they often are less socially integrated at university (Rubin et al., 2019). Furthermore, students with lower social status are at risk for higher stress rates, worse mental health, doubts about their academic abilities and reduced sense of belonging to the academic environment as well as for lower academic and life satisfaction (Granfield, 1991; Allan et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2016; Easterbrook et al., 2022; Wondra and McCrea, 2022; Janke et al., 2024). These negative experiences depending on social status may result from different mismatch experiences between student’s status related socialization and prevailing norms and expectations in academic contexts (Goudeau et al., 2024). Such mismatch experiences may provoke both short-term and long-term negative experiences and self-evaluations, explaining lower well-being in students with lower social status (Stephens et al., 2012; Manstead, 2018; Goudeau et al., 2024). Simultaneously, the occurrence of perceived mismatches and the severity of effects on well-being and other outcomes may vary depending on contextual moderators, such as the national or educational context (Goudeau et al., 2024). Thus, it is important to examine to which extent these propositions translate to a national level and specific educational institutions and levels.

Although the German higher education system represents a typical western higher education system in many ways (Janke et al., 2017), it also shows certain characteristics like its high selectivity in the school system, but an absence of tuition fees (Janke et al., 2017; Schindler and Bittmann, 2021). With every educational degree, the distribution of social status among students becomes more uneven (Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e.V, 2020). In Germany, for example, out of 100 children with non-academic parents, 46 visit a school enabling access to higher education, while 80 out of 100 children from academic parents do so (Kracke et al., 2024). Out of 100 children of non-academic parents, 25 enrol at universities in contrast to 78 out of 100 children from academic households (Kracke et al., 2024). With some exceptions (see, e.g., Goudeau and Croizet, 2017; Janke et al., 2017; Janke et al., 2024) most research on the experience and behavior of students with lower social status in higher education was conducted in the U.S. However, findings from one educational and social context may not readily be applicable in other countries and contexts as the consequences of social inequality might differ in general but also in terms of severity, given the national context (Sommet and Elliot, 2023; Goudeau et al., 2024). Thus, it remains an open question to which degree differences in well-being suggested by previous research and theory (Goudeau et al., 2024) generalize to the German context.

In order to understand how social status translates into psychological variables like well-being, it is important to consider mediating mechanisms which explain how negative experiences emerge depending on social status. One such mediator could be the experience of motivational action conflicts. Motivational conflicts are characterized by (at least) two possible activities a student is motivated to carry out which cannot be realized at the same time and therefore force individuals to set priorities (Hofer et al., 2005, 2017; Capelle et al., 2022). Conflicting activities can be characterized by different aspects, namely assigned valences and related costs as well as underlying goals (Brassler et al., 2016; Capelle et al., 2022). The consideration which activity should be chosen builds upon how rewarding they appear but also how costly a decision against them might be (Dietz et al., 2005; Fries et al., 2007). For example, working on a paper might be more rewarding in the long term than going out for dinner with friends. In the moment however, the cost of missing out on socializing might feel too big to continue with the paper. Hence, motivational conflicts arise when different options for activities come up, each of which is in some way attractive and costly when denied. Typically, conflicts within the leisure domain (e.g., meeting friends or going on a walk), within the study domain (e.g., writing an essay or preparing a presentation) or in between those (e.g., going shopping or studying for an exam) are examined (Hofer et al., 2017). However, motivational conflicts arise between more than those categories, such as study and work, daily obligations and chores, family and partnership, friends and acquaintances, recreation and hobbies as well as self and development (Grund et al., 2014). Depending on conflict content, conflicts can further be characterized as either want- or should-conflicts (Dietz et al., 2005). Want conflicts arise when a person decides against an activity that he or she wants to do, should conflicts on the other hand refer to situations when a person decides against an activity that he or she should do (Dietz et al., 2005).

Experiencing motivational conflicts represents a typical challenge in the everyday life of students (Dietz et al., 2005; Grund et al., 2015a; Capelle et al., 2020) and negatively impacts well-being as visible in more negative and less positive affect during conflicts and poorer life satisfaction (Ratelle et al., 2005; Riediger and Freund, 2008; Kuhnle et al., 2010). The more frequently individuals experience motivational conflicts, the stronger the negative consequences on well-being (Kuhnle et al., 2010; Grund and Fries, 2014). Beyond the mere frequency of motivational conflicts, well-being depends on conflict reactivity (Grund et al., 2021). Conflict reactivity refers to “cognitive-affective reactions” (Grund et al., 2021, p. 410) toward the experience of motivational conflicts. Motivational conflict situations can be evaluated as results from deficiencies and incompetencies like a lack of self-determination. This self-critical rumination results in lower well-being, making the evaluation of and the reaction to the conflict situation more detrimental for well-being than the conflict itself.

The experience of motivational conflicts depends on students’ life realities and opportunities (Hofer et al., 2017). However, it has not been investigated yet whether students’ experience of motivational conflicts is related to their social status. Given that the latter strongly influences several aspects of student’s experiences and behavior in the academic context (Langhout et al., 2009; Goudeau et al., 2024), it may also influence the experience of motivational conflicts in several ways. We hypothesize that motivational conflicts occur more often for students with lower as compared to higher social status and that they have a stronger negative impact on their academic well-being. First, since motivational conflicts occur due to limited resources like time, with a rising number of possible activities, the frequency of conflict experiences increases as well. Students with lower social status work more hours than their higher social status peers to cope with less financial resources (Mcloyd et al., 2015; Reynolds and Cruise, 2020), take over more caring responsibilities and are more strongly bound to their families than students with higher social status (Covarrubias et al., 2019). Students with lower social status develop a new identity as university students which comes with academic obligations while still identifying with their lower social status backgrounds in which strong familiar bonds and resulting responsibilities and duties are nurtured (Mcloyd et al., 2015; Covarrubias et al., 2019; Goudeau et al., 2024). This way, time as a resource becomes even more scarce, giving rise to motivational conflicts in everyday life.

The comparative lack of social capital that accompanies students with lower social status may enhance conflict experiences: Cultural capital describes a combination of useful knowledge and skills which is valued and respected in academic contexts and also helps meeting its challenges (Jenkins et al., 2013; Ditton et al., 2019). Since students with higher social status are mostly continuing generation students, their parents were able to transmit their own cultural capital in form of interests, language, and behavioral strategies on to their children (Gaddis, 2013; Jury et al., 2015; Ditton et al., 2019). It is likely that parents who went to university are more easily able to pass on experience, knowledge and strategies about how to organize and prioritize everyday life to avoid motivational conflicts. Similarly, Collier and Morgan (2008) showed that first-generation students struggled with time management and setting priorities as well as a lack of “outside resources to help them deal with these demands” (p. 436). These mechanisms make the occurrence of motivational conflicts more likely for students with lower social status and may thus lead to more frequent conflict experiences.

Further, students with lower social status may react stronger to conflict experiences than their peers with higher social status, that is, show a higher conflict reactivity (Grund et al., 2021). Since students with lower social status tend to experience more doubt about their abilities and more strongly worry about their fit within university (Easterbrook et al., 2022; Wondra and McCrea, 2022), this context related insecurity might translate into a stronger conflict reactivity. Research on cognitive processes behind the discrimination of minority university students points out that many show heightened vigilance or rumination and anticipation stress while navigating through academic contexts (Hicken et al., 2014; Ortiz et al., 2021). A heightened anticipation of discrimination may lead to a stronger reaction to motivational conflicts since these experiences feed into existing performance related stereotypes for students with lower social status (Wondra and McCrea, 2022; Bauer et al., 2023). In the academic context, lower social status is associated with less academic abilities (Jury et al., 2015; Bauer et al., 2023)—a stigma which lower social students are aware of and which impairs their well-being and performance (Johnson et al., 2011). Thus, they may feel they have more at stake in a challenging situation like motivational conflicts compared to peers with higher social status. We therefore expect that students with lower (compared to higher) social status experience higher conflict reactivity.

Additionally, we expect that motivational conflicts have a stronger negative impact on well-being in students with lower (compared to higher) social status. Since life satisfaction is diminished when experiencing motivational conflicts, we expect an impairment of study satisfaction as a function of conflict frequency and reactivity as well. Academic well-being is conceptualized through general well-being and study satisfaction. First, students with lower social status show higher levels of stress and worse mental well-being in the first place (Rubin et al., 2016; House et al., 2020). Due to the experience of classism in higher education, students with lower socials status also experience less life satisfaction and academic satisfaction (Allan et al., 2016, 2023). Hence, the experience of motivational conflicts might have a stronger negative impact on academic well-being for students with lower social status than for students with higher social status due to a worse state to begin with. Furthermore, negative experiences in the academic context may lead to impaired well-being of students with lower social status because they might attribute those to inherent deficiencies (Goudeau et al., 2024). Based on this, we expect that the experience of motivational conflicts is more strongly negatively related to academic well-being for students with lower social status than for their higher social status peers.

2 The present studies

To reduce adverse effects of social status differences in higher education (Sirin, 2005; Langhout et al., 2009; Janke et al., 2017; Rubin et al., 2019), it is important to understand how an individual’s social status translates into academic well-being and if existing findings generalize to different national and educational contexts. The following two studies, both of which received ethical approval by the university’s institutional review board (2024-86k), examine whether the experience of motivational conflicts, a common and negative experience for many students (Ratelle et al., 2005; Riediger and Freund, 2008; Kuhnle et al., 2010) differs depending on students’ social status in terms of frequency, reactivity and impact on academic well-being, which has not been examined to date. The first study tests the basic theoretical assumptions using well-established, prototypical motivational conflict situations to assess the frequency of motivational conflicts, general well-being, and study satisfaction. The second study includes a more individualistic approach of measuring conflict experiences. It also provides more detail on the assumed relations, assessing conflict reactivity in addition to mere frequency, an in-the-moment measure of affect, and study satisfaction. Furthermore, the second study provides more insights on the life realities of the participants which, as discussed, are expected to influence conflict experience. Should these hypotheses be supported, another piece could be added to the puzzle of how social status and disparities in higher education are related and possible approaches for targeted support could be provided. Further, the generalizability of adverse effects of social status on the well-being of students across nations and educational levels could be confirmed. Lastly, the theory of motivational action conflicts (Hofer et al., 2017) would be enriched by another individual characteristic of students which influences conflict experiences.

3 Study 1

In the first study,1 we focussed on testing whether the frequency of motivational conflicts differs between students depending on their social status and whether this potential difference predicts lower general well-being and study satisfaction among lower status students. We expected that lower social status is related to lower academic well-being (Hypothesis 1). This association was hypothesized to be mediated by the frequency of motivational conflicts (Hypothesis 2), which we expected to be higher the lower the social status (Hypothesis 3). Additionally, it was expected that more frequently experiencing motivational conflicts is associated with lower general well-being and study satisfaction (Hypothesis 4). Figure 1 displays the respective theoretical model.

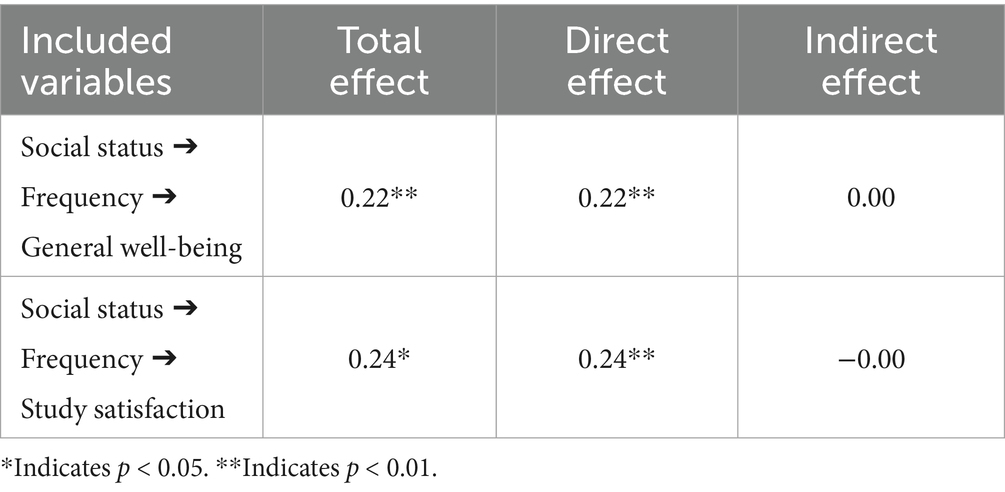

Figure 1. Statistical model with standardized estimates study 1. *Indicates p < 0.05. **Indicates p < 0.01.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Data collection

Cross-sectional data was collected between December 2023 and February 2024 at German universities in the form of an anonymous online survey on the platform Sosci Survey (Leiner, 2023). Participants were recruited via various student networks and mailing lists, as well as a snowball system in social networks. They could take part in a gift voucher lottery as an incentive for participation. In addition, participating psychology students were able to obtain course credit for participation. Out of originally 355 completed participations, one case was excluded due to response patterns. Another 16 cases aborted the survey before answering any study variable, and 11 cases aborted the survey after only answering one out of three questions which were later integrated into one variable (see conflict frequencies). These cases were excluded, too. To avoid potential stereotype threat effects on the measured variables (see, e.g., Inzlicht et al., 2006; Beilock et al., 2007; Inzlicht and Kang, 2010), participants were in the beginning of the questionnaire only informed about the research topic of motivational conflict. At the end of the survey, participants received full information about the study’s interest in social status and had the opportunity to withdraw their consent after being educated about the research interest, leading to the exclusion of another three cases. The final sample consisted of N = 324 German speaking university students, of whom 78.4% were women, 17.3% men, and 1.9% diverse students, who were M = 22.27 years old on average (SD = 4.08, min. 18 years, max. 71 years). 54.9% were Psychology students (please see Supplementary Table 1 for a detailed list of disciplines). The sample consisted of 66.05% so called continuing generation students (CGS) and 31.48% first-generation students (FGS). FGS are the first members of their families to visit university, while CGS’ parents either both or partly obtained a university degree (House et al., 2020). In comparison to representative student samples from Germany, the current sample has proportionally more women, and slightly more continuing-generation students, and was on average slightly younger: 50.6% of German students identify as women, 48.4% as men, and 1% as diverse. They are on average 23.5 years old and 58% come from academic households (Kerst et al., 2024).

3.1.2 Procedure an Instruments

After at first only informing the participants about motivational conflicts as the research aim of the study as well as their rights and the data protection policy, the students were shown a brief explanation of the concept of motivational conflicts and were instructed to vividly imagine themselves in situations like the ones which would be presented subsequently. They were then shown vignettes representing different conflict scenarios (study–study, leisure–study, leisure–leisure) and asked how often they typically experience each type of conflict. Afterwards, participants filled out scales assessing their general well-being, their study satisfaction, demographic data and their social status in this order. The following instruments were used (please see Supplementary Table 2 for information on the scales). By the end of the study, participants received full closure about the research interest in social status and were able to withdraw their consent for data analysis.

3.1.2.1 Motivational conflicts

In the past, the use of vignettes, asking participants to imagine themselves in typical everyday conflict situations has been implemented as a prominent method to operationalize motivational conflicts (see, e.g., Dietz et al., 2005; Grund and Fries, 2012). Following this approach, three different conflict categories (study–study, leisure–study, leisure–leisure) were introduced via short vignettes. The German version of the study–leisure vignette was used successfully in the past by, e.g., Dietz et al. (2005) or Grund and Fries (2012). We additionally created similar vignettes for study–study and leisure–leisure conflicts. This leaves us with scenarios from both domains (leisure and study) while simultaneously portraying want- (leisure–study, leisure–leisure) as well as should-conflicts (study–study).

You are sitting at your desk in the afternoon and want to read a text that you need to prepare for one of your seminars. At that moment, a notification pops up on your phone. Your calendar reminds you that you have to give a presentation in another seminar soon that you have not yet prepared. You only have time to read the text for one seminar or prepare the presentation for the other seminar now. (Study–study).

You are sitting at your desk in the afternoon and want to read a text that you need to prepare for one of your seminars. At that moment, a message appears on your cell phone. Your friends ask you if you would like to do something together. Your friends want to come by right away to pick you up. (Leisure–study).

You are getting ready to leave your home in the afternoon because you want to do something with your friends. At that moment, a notification pops up on your cell phone. Your calendar reminds you that your weekly hobby is coming up. This appointment is about to start. (Leisure–leisure).

Participants were asked to imagine themselves in each scenario and think of a similar conflict situation they have experienced before. After each vignette, they answered questions about the frequency with which they experience the respective conflict type on a Likert scale from 1 = “very rarely” to 5 = “very often.” The mean of the indicated frequencies of the three conflict categories was then taken to create an index for conflict frequency. This procedure has been implemented similarly by, e.g., Kuhnle et al. (2010) and in our case showed an internal consistency of α = 0.60. This relatively low internal consistency likely results from averaging three different facets of the same phenomenon. We decided to keep the index since we were interested in conflict frequencies in general while adding explorative analyses of the model for each conflict scenario separately (please see Supplementary Tables 3–5).

3.1.2.2 General well-being

For measuring well-being, we included the BIT, the brief version of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving by Su et al. (2014). While the CIT consists of 54 items, assessing 18 facets of positive functioning, forming seven dimensions of psychological well-being, the short version assesses 10 of those facets with one item each, representing six of the seven dimensions (Relationship, Engagement, Mastery, Meaning, Optimism, Subjective Well-Being). Participants were presented with ten items measuring different aspects of thriving on a 5-point scale (1 = “completely disagree,” 5 = “completely agree”), e.g., “My life has a clear sense of purpose.” The brief version of the inventory makes it highly economical to use in rather extensive surveys and has been validated and applied successfully in the past (Wiese et al., 2018). The scale showed a high internal consistency of α = 0.83, ω = 0.87.

3.1.2.3 Study satisfaction

Study satisfaction was measured by the FB-SZ-K, a short version of a German questionnaire on study satisfaction by Westermann and Heise (2018). The questionnaire contains three subscales, namely satisfaction with the study contents (e.g., “I find my studies really interesting”), with the study conditions (e.g., “I wish the study conditions at the university were better”), and with coping with the study demands (e.g., “I often feel tired and exhausted from studying”) by three items each. Participants were asked to indicate their answer on a 5-point scale from 1 = “does not apply at all” to 5 = “fully applies.” Reliability turned out high at α = 0.80, ω = 0.89.

3.1.2.4 Social status

Social status was measured by the Comprehensive Social Class Scale (CSCS; Evans et al., 2022). This comparative score combines different assessments that are traditionally used for measuring social status and also pays attention to objective as well as subjective perspectives (Evans et al., 2022). The first included indicator for social status in the CSCS is parental education. Participants are asked to choose from a list of possible educational levels for both of their parents. Then, students’ subjective perception of parental occupational prestige is measured by a 11-point scale ranging from “extremely low status and prestige” (1) to “extremely high status and prestige” (10) for both parents. Childhood wealth is assessed by three items which participants could agree to on a 5-point scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5) (e.g., “My family usually had enough money to buy things when I was growing up”). Participants were then asked to indicate their parent’s as well as their own social class, choosing from “working-class,” “lower middle-class,” “middle-class,” “upper middle-class,” and “upper-class.” An additional subjective measure for social status included in the CSCS is the MacArthur Scale (see, e.g., Demakakos et al., 2008): Participants are presented with the drawing of a ladder with ten rungs as well as the description that the top rung resembles the most wealthy and successful people of society and the lowest rung the least wealthy and successful ones. Participants are then asked to pick the rung that best represents their family’s social position. In total, the CSCS consists of eleven items. All items of the CSCS were z-standardized for statistical analyses as proposed by the authors (Evans et al., 2022).

The CSCS so far only existed in English. For integrating it in the German survey, we translated the scales comparing and integrating different translations by ourselves, DeepL (DeepL SE, 2024), and ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2024). Its internal consistency was high, α = 0.88, ω = 0.91.

3.1.3 Statistical analysis

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses for the latent variables to evaluate their structure before integrating them into the measurement model of the structural equation model for hypotheses testing. For evaluating model fits, the following criteria were used: χ2/df-ratios between 2 and 3 indicated good or acceptable model fits (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003), a CFI > 0.97 indicated good fit (Eid et al., 2017), and 0.97 > CFI > 0.95 an acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999). MacCallum et al. (1996) specified a RMSEA of 0.01 as excellent, 0.05 as good and 0.08 as mediocre model fit. Also, an SRMR value close to 0 indicates good model fit (Eid et al., 2017), while values > 0.08 indicate substantial differences between model and data (Hu and Bentler, 1999). After the exclusion of cases as described, 10 remaining cases contained missing data. To correct for those, the models were estimated with full information maximum likelihood. Several exploratory analyses were run.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Relations between social status, conflict frequency, and academic well-being

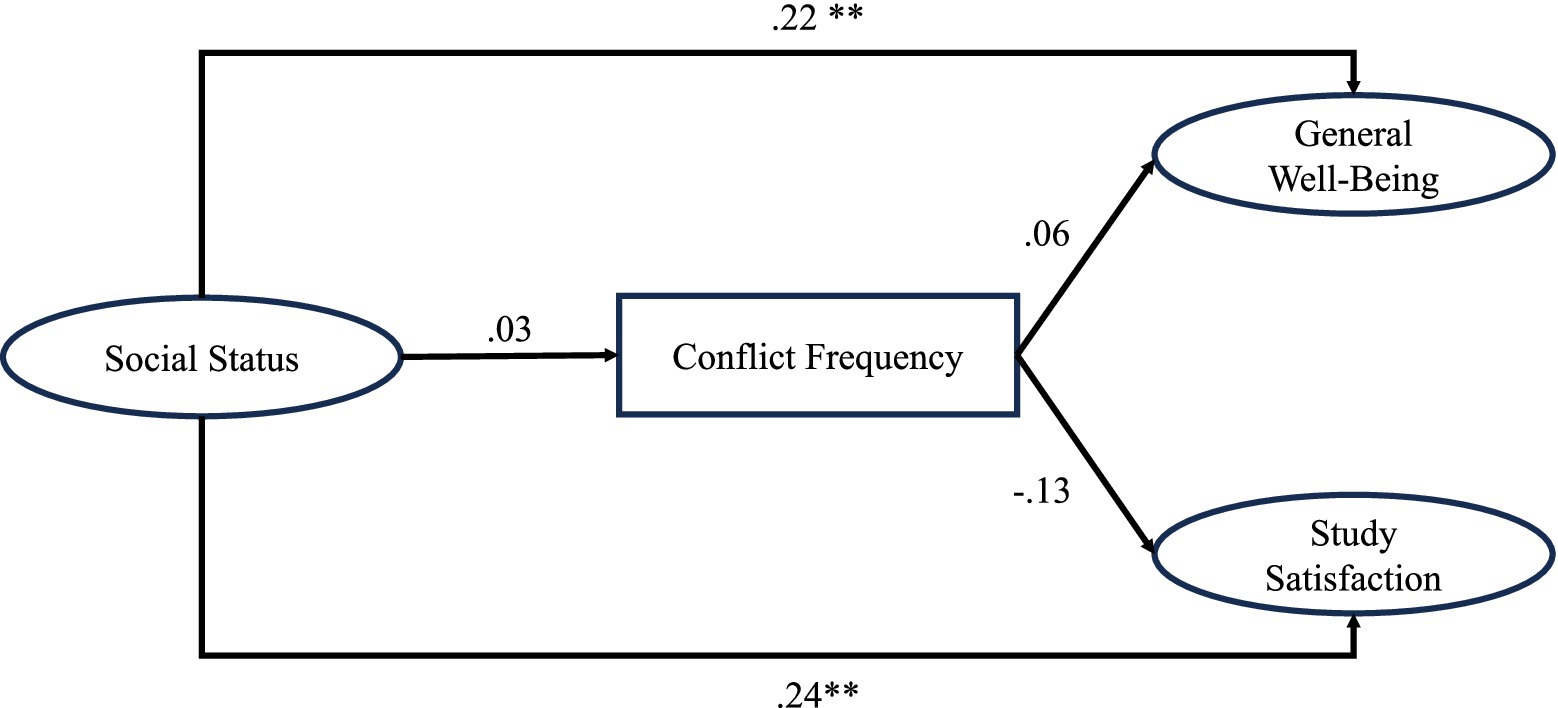

The measurement model contained respecifications resulting from confirmatory factor analyses of the measurement instruments (see Supplementary Table 6). Conflict frequency was integrated as a manifest variable (please see Figure 1 for the statistical model). The model fit indices were = 1.73, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05 and SRMR 0.06, showing a good fit with the exception of the CFI. The fit indices for the full SEM were good, except for the CFI, = 1.48, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06. Table 1 lists the standardized regression coefficients for the mediation effects.

In line with our hypotheses, higher social status was related to better general well-being (β = 0.22, p < 0.01) and higher study satisfaction (β = 0.24, p < 0.01). However, conflict frequency was associated neither with lower general well-being nor lower study satisfaction. The indirect effects between social status, conflict frequency and general well-being, as well as study satisfaction were also non-significant. Hence, our mediation hypothesis could not be supported either.

3.2.2 Exploratory analyses

The variable conflict frequency was computed by averaging the mean of the frequency of conflicts within the leisure domain, within the study domain and between the two of them. We conducted additional structural equation models for each of the three conflict scenarios and compared the results to check for possible implications of the contents of the conflicts. We also derived five subscales from the CSCS, namely parental occupational prestige, parental education, childhood wealth, parental social class and family social class. We conducted further SEM with each of the scales as predictors to check for possible differences in the results depending on the certain aspect of social status that is integrated. In none of the additional SEM, social status was related to conflict frequency.

3.3 Discussion

The goal of the first study was to examine whether a more frequent experience of motivational conflicts is related to the well-being of students, and whether social status plays a role in this. Based on cross-sectional survey data, structural equation modeling provided evidence that, in line with previous findings (Granfield, 1991; Rubin et al., 2016, 2019), students with higher social status in fact reported better general well-being and higher study satisfaction (Hypothesis 1). However, other than expected, the social status did not predict how frequently students experience motivational conflicts (Hypothesis 3) and the mediating mechanism of motivational conflicts was not detected (Hypothesis 2).

Potentially, the frequently used prototypical conflict scenarios were not sensitive enough to the students’ different life realities since they only focus on university related and leisure related activities. An additional job, taking over responsibilities within the family or caring for own children are not included. The second study therefore uses actual conflict experiences of the participants by letting them recall them, leaving room for social status specific experiences. The second study also explicitly collects data on caring responsibilities and working hours to examine actual differences in life realities.

Interestingly, the well-established link between motivational conflicts and adverse consequences, such as lowered well-being, was not found in the present study (Ratelle et al., 2005; Riediger and Freund, 2008; Kuhnle et al., 2010). The lack of significant findings for the association of conflict frequency and general well-being might have resulted from the broadness of the BIT assessing well-being in comparison to the relatively narrow focus of the conflict scenarios leading to a mismatch in criterion and predictor specificity (Baranik et al., 2010). Therefore, the second study examines momentary affect in the reported conflict scenarios instead of broad and general well-being. Further, the BIT assesses various aspects of well-being: Support, belonging, engagement, accomplishment, self-efficacy, self-worth, meaning and purpose, optimism, life satisfaction and positive feelings (Su et al., 2014). Certain aspects of the sub-scales did in fact show significant correlations with conflict frequency (see Supplementary Tables 3–5). A sense of relatedness and belonging was positively related to general conflict frequency and frequencies of conflicts within the leisure domain or between the leisure and study domain. Subjective well-being (e.g., “My life is going well”) was negatively related to conflict frequency within the study domain and positively related to conflict frequency within the leisure domain.

Also contrasting the hypotheses, the relation of conflict frequency and study satisfaction as one facet of academic well-being was non-significant as well. This also possibly resulted from the operationalisation of motivational conflicts. Hence, methodological reasons might have led to a lack of significant findings in the first study while the experience of motivational conflicts indeed mediates the relation between social status and academic well-being of students as hypothesized. The second aimed at addressing these very issues.

4 Study 2

The second study2 expected that social status remains negatively related to academic well-being (Hypothesis 1). Further, the correlation between students’ social status and the frequency of motivational conflicts (Hypothesis 2) as well as a mediation effect on academic well-being (Hypothesis 3) not found in study 1 was expected to appear due to improved assessment methods. To better reflect potential differences in the experience of motivational conflicts due to different life realities causing them, this study used a more individualistic measure for conflict experiences. Further, the second study included conflict reactivity as another mediating variable to examine whether cognitive and affective evaluation of conflict experiences beyond their frequency impact well-being (Grund et al., 2021). If a highly self-critical rumination about the situation and one’s part in it takes place afterwards, well-being declines. Because of the existing insecurities concerning competence and academic fit among students with lower social status (Easterbrook et al., 2022; Wondra and McCrea, 2022), we expect a direct link between social status and conflict reactivity (Hypothesis 4) and conflict reactivity to mediate the relation between social status and academic well-being (Hypothesis 5). We also specifically assessed working hours and caring responsibilities for family members, expecting students with lower social status to work more hours and take over more caring responsibilities (Kroher et al., 2021).

4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Data collection

Similar to study 1, cross-sectional data was collected between November 2024 and January 2025 at German universities in an anonymous online survey on the platform Sosci Survey (Leiner, 2023). Participants were recruited and rewarded the same way as for the first study. In addition, we particularly reached out to different faculties and universities of applied sciences across Germany which, according to Müller and Pollak (2016) count an especially high number of FGS for participants.

In total, N = 470 persons filled out the survey, of which seven cases were excluded due to response patterns, three due to data withdrawal after receiving full disclosure about the study’s aims at its end, and 16 due to aborting the survey before answering any study variable. The final sample consists of N = 460 university students, including 75.7% women, 19.8% men, and 3.9% diverse students who were M = 23.01 years old (SD = 4.92, min. 18 years, max. 58 years). On average, they were in their sixth semester at university (M = 5.54, SD = 4.87). 40.4% were psychology students (please see Supplementary Table 8 for a detailed list of disciplines). 36.6% FGS and 63.4% CGS were represented [for comparison, 50.6% of German students identify as female, 48.4% as male, and 1% as diverse. They are on average 23.5 years old and 58% come from academic households (Kerst et al., 2024)]. Participants worked 6.89 h per week alongside their studies on average (SD = 9.79, min. 0, max 43). 3.04% reported caring for children and 2.83% caring responsibilities for relatives.

4.1.2 Procedure and Instruments

The procedure was similar to study 1, while some measurement instruments changed. After recalling motivational conflict experiences and answering questions about their frequency, the experienced conflict reactivity, as well as momentary affect, the same scales assessing study satisfaction (α. = 84, ω = 0.92), and social status (α. = 0.90, ω = 0.92) as in study 1 as well as further demographical questions were presented (see Supplementary Tables 9–14).

4.1.2.1 Motivational conflicts

To enable a more realistic portrayal of motivational conflicts, participants were asked to recall motivational want- and should conflicts they have actually experienced (for a similar procedure, please see Grund et al., 2014). First, we asked them to envision a should conflict which is typical for their everyday life:

Imagine you are doing something that is typical of your everyday life and that you enjoy doing. At that moment, it occurs to you that you should actually be doing something else at the same time that you do not like doing as much. However, you cannot do both at the same time and stick to what you like doing.

Participants listed the enjoyable activity they decided to continue and the obligational activity they decided against to strengthen their situational recall. They next reported how often they experienced such conflicts in their everyday life on a Likert scale from 1 = “very rarely” to 5 = “very often.” Afterwards, participants were asked to recall a want conflict in the same manner and once again to answer the question about its frequency. To indicate general conflict frequency, we conducted the mean across both conflict type’s frequencies (r = 0.32). Before starting the data collection, cognitive pretests were conducted by presenting the material and asking participants to answer the questions thinking out loud. After slight adaptions in the wording of some instructions, we were left with satisfactory feedback, making sure the instructions were well understood.

4.1.2.2 Momentary affect

To assess momentary affect as the affective counterpart to the cognitive evaluation of study satisfaction in academic well-being, and to reduce possible predictor-criterion incongruence of general well-being in the first study, the PANAS [German version by Watson et al. (1988) and Krohne et al. (1996)] was used. The PANAS asks participants to rate how they felt in that particular situation of motivational conflict on 20 items including positive and negative affect words (10 items each, e.g., “interested” and “nervous”) on a scale from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “very much.” The measures for momentary positive and negative affect were then aggregated over both conflict situations, conducting their mean (e.g., Grund et al., 2015b). The scales showed satisfying reliabilities of α = 0.87, ω = 0.91 (positive affect) and α = 0.90, ω = 0.92 (negative affect).

4.1.2.3 Conflict reactivity

We measured conflict reactivity for want and should conflicts with the conflict reactivity scale (Grund et al., 2021). It contains seven items asking for different aspects of conflict reactivity after both conflict scenarios (e.g., “I was annoyed about what I was currently doing, because I wanted to do/should be doing something else”) which were answered on a scale from 1 = “does not apply at all” to 5 = “fully applies.” We presented this scale, just as the PANAS once after each of the two conflict scenarios and conducted the mean of both. It showed a satisfying reliability of α = 0.84, ω = 0.89.

4.1.2.4 Additional information and demographics

In addition to the demographics already implemented in the first study, we asked participants to indicate how many hours a week they work alongside their studies, and whether they have caring responsibilities for children or relatives.

4.1.3 Statistical analysis

As in study one, we estimated the proposed model through SEM after testing the factorial structure of all measurement instruments in confirmatory factor analyses as in study 1. To handle missing data, full information maximum likelihood estimation was used. We also conducted models for both want and should conflicts separately. As in study 1, we assessed different subscales of social status and study satisfaction in form of separate models for want and should conflicts each. We also included semester number as a covariate and used linear regression to assess the relation of social status and working hours per week as well as binary logistic regressions for its relation with caring responsibilities. Since several variables were not normally distributed, all estimations were conducted using MLR.

Identically to study 1, we conducted separate exploratory SEM, for different indicators of social status assessed by the CSCS (Evans et al., 2022). We further conducted SEM for each subscale of study satisfaction as dependent variables (satisfaction with content, conditions, and coping).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Preliminary analyses of measurement models

Unlike preregistered, we did not compute a model averaged across motivational conflicts as in previous studies (e.g., Grund et al., 2021) since confirmatory factor analyses for reactivity, positive, and negative affect showed an inadequate model fit if averaged across conflict types. Therefore, all of the respective variables were analyzed in conflict-specific models separately. Identically to study 1, study satisfaction was included with one second and three first order factors (see Supplementary Table 15 for fit indices and adaptations made based on the confirmatory factor analyses).

4.2.2 SEM

The SEM for want conflicts including all adaptions made during the CFAs showed good fit, except for CFI (= 2.06, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06). Like in the first study, this may result from a high model complexity. The measurement model for should conflicts revealed a similar fit (= 1.82, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.05).

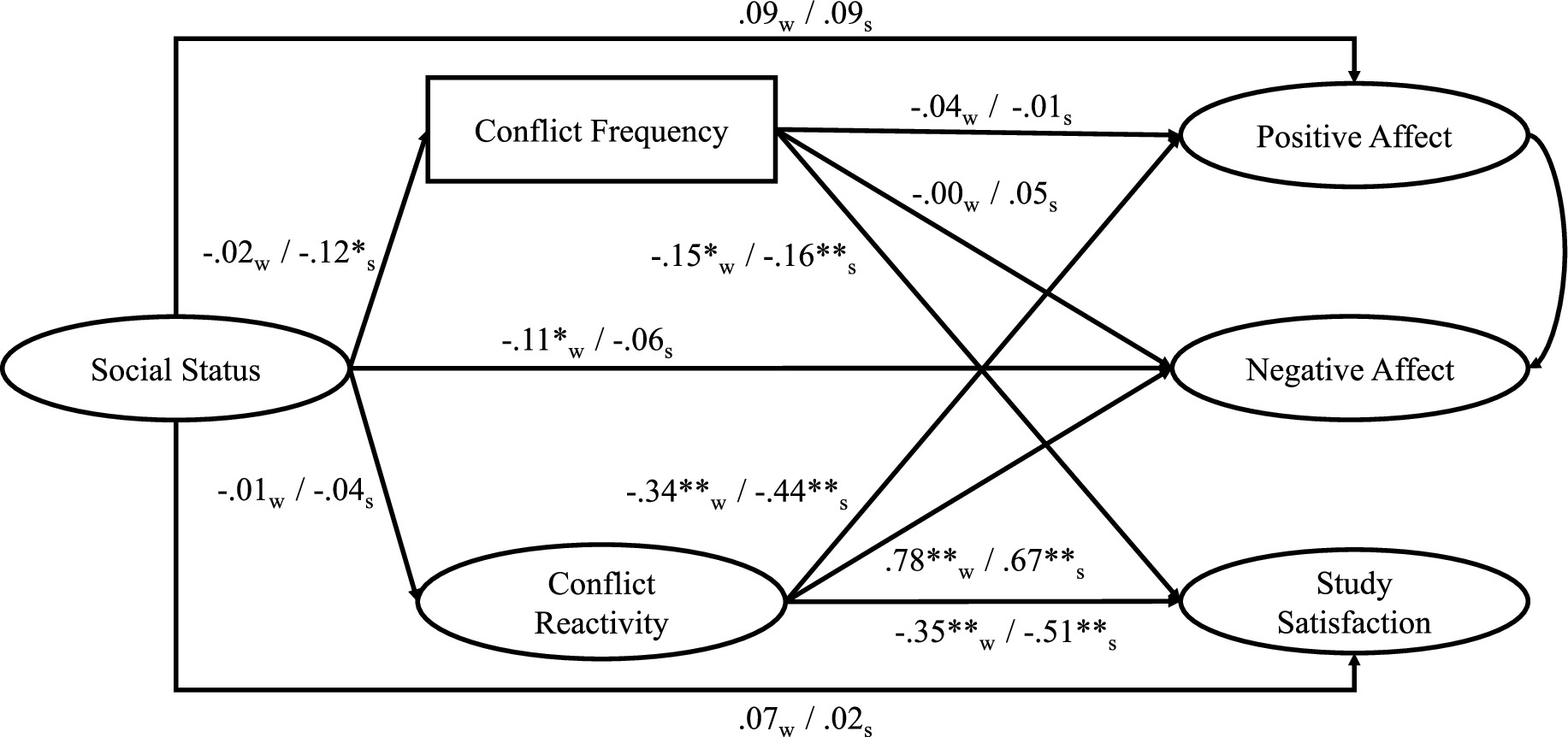

Supporting our hypotheses, social status was negatively related to negative affect in want conflicts (β = −0.11, p < 0.05) and to conflict frequency in should conflicts (β = −0.12, p < 0.05). Accordingly, the lower the social status of students the stronger they experience negative affect during want conflicts. Also, the lower the social status of students, the more often they experience should conflicts. All other hypotheses concerning the relations of social status including the mediation hypotheses could not be supported. However, other than in study 1, conflict frequency was related to study satisfaction in want (β = −0.15, p < 0.05) and should conflicts (β = −0.16, p < 0.01), but not to positive or negative affect. Conflict reactivity on the other hand was related to all three outcome variables in want and should conflicts as expected (please see Figure 2 for the statistical model).

Figure 2. Statistical model with standardized estimates study 1. Results for want (w) and should (s) conflicts. *Indicates p < 0.05. **Indicates p < 0.01.

4.2.3 Additional exploratory analyses

Identically to study 1, we conducted separate SEM for different indicators of social status assessed by the CSCS (Evans et al., 2022): Parental occupational prestige, parental education, childhood wealth, parental social class, and family social class for want and should conflicts each. The inspection of the SEM containing different indicators of social status and study satisfaction (satisfaction with study content, conditions, and coping with requirements) revealed a tendency of negative relations of social status and negative affect in want conflicts (in accordance with the overall model) and a positive relation with positive affect in should conflicts (other than in the overall model) (please see Supplementary Table 16).

Furthermore, parental occupational prestige (β = −0.12, p < 0.05), parental social class (β = −0.11, p < 0.05), and family social class (β = −0.15, p < 0.01) were positively related to the frequency of should conflicts but not to the frequency of want conflicts, just like the overall indicator for social status. Hence, the positive association of social status and the frequency of should conflicts likely goes back to the parental occupational prestige, parental social class, and family social class of students, more than to their parent’s education or childhood wealth.

While social status showed no relation with the overall indicator for study satisfaction, it was related to satisfaction with study content in both want (β = 0.11, p < 0.05) and should conflicts (β = 0.12, p < 0.05), meaning that the higher the social status the more satisfied students are with the content of their studies. Satisfaction with study conditions as well as satisfaction with coping with study requirements were however not related to social status. In none of the SEM, results supported our mediation hypotheses or the proposed relation of social status and conflict reactivity. However, in every SEM, reactivity was related to positive and negative affect as well as study satisfaction. Conflict frequency showed no relations with positive and negative affect, but with satisfaction with study conditions and coping with study requirements.

4.2.4 Covariate analysis

University semester was integrated as further independent variable, interacting with social status and predicting affect and study satisfaction. For want conflicts, there was no significant interaction of social status and number of semesters. For should conflicts, the interaction was significant for negative affect (β = −0.160, p < 0.05). However, the relation of social status and negative affect itself remained non-significant.

4.2.5 Life realities

Lastly, regression analyses showed that in line with our hypothesis, hours that students worked alongside their studies decreased significantly with higher social status (β = −0.14, p < 0.05) while caring responsibilities for children [OR = 2.15 (1.05;4.42)] as well as for family members [OR = 4.08 (1.92;9.31)] became significantly less as well.

4.3 Discussion

The goal of study 2 was to address methodological limitations of the first study to examine whether social status is related to the frequency of and reactivity after motivational conflicts and associated academic well-being in the academic context. We assessed biographical want and should conflict scenarios, momentary affect in these conflict situations, conflict reactivity as well as different aspects of students’ life realities.

4.3.1 Social status and well-being (Hypothesis 1)

Relations between social status and momentary affect differed between conflict scenarios: In want conflicts, students’ social status was related to negative, but not to positive affect. That is, if students with lower social status do something that they should do while simultaneously wanting to do something else, it comes along with stronger negative affect than for students with higher social status. This could be taken as a hint that students with lower social status suffer more from tasks that they should do if they conflict with attractive activities than their higher social status peers. A feeling of missing out on attractive activities that might include socializing with other students likely strengthens the feeling of alienation and not being socially integrated (House et al., 2020; Easterbrook et al., 2022). In should conflicts, no significant relation of social status with either affect was found.

Study satisfaction was not predicted by social status as opposed to previous findings in study 1 and previous research (Allan et al., 2016, 2023). Only regarding the content of studies (one of three subscales), students with higher social status reported more satisfaction than peers with lower social status. Students with lower social status tend to name the goal of improving their financial prospects and occupational prestige in the future as a drive for studying (Ayala and Striplen, 2002; Irlbeck et al., 2014). This can be described an externally motivated behavior since it is aligned with attaining a certain reward or avoiding unpleasant consequences which is the most strongly controlled quality of emotion (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Intrinsic motivation on the other hand is considered the most autonomous quality of motivation and drives behavior completely based on interests and without the expectation of resulting consequences other than the satisfaction of the needs for autonomy and competence (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Since interest in the study predicts satisfaction with its content (Wach et al., 2016), a rather extrinsic motivation of students with lower social status might explain this finding. However, it remains questionable why the other aspects of study satisfaction were no longer related to social status.

4.3.2 Social status and motivational conflicts

The frequency of motivational conflicts was predicted by social status in should conflicts, partly supporting our Hypothesis 2. Students with lower social status more often feel like they should do something else while doing something they want to do than their higher social status peers. This difference is likely related to additional tasks students with lower social status must face during everyday academic life: As literature suggests and our findings support, students with lower social status must juggle more responsibilities and duties during their studies since they work more hours and take care of family members more often (Mcloyd et al., 2015; Covarrubias et al., 2019; Reynolds and Cruise, 2020).

In this study, students with higher and lower social status did not differ concerning the cognitive and affective evaluation of conflict scenarios (conflict reactivity, Hypothesis 4). This lack of findings might be due to a methodological issue: Grund et al. (2021) presented the scale for reactivity several times during an event sampling period. This way, participants related it directly to different conflict situations. Assessing only two prototypical conflict situations might not have been sufficient to portray possible motivational conflict differences due to social status because some conflict situations might relate stronger to it than others.

Taken together, significant relations of social status were found with negative affect in want conflicts and with frequency of should conflicts in study 2. Affect and study satisfaction were, however, mainly predicted by reactivity, not by frequency, which in turn was not related to social status. Thus, social status was not related to cognitive and affective well-being through the experience of motivational conflicts the way we expected (Hypotheses 3 and 5).

5 General discussion

Students with lower social status are underrepresented in higher education (Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission e.V, 2017) and have previously reported to struggle with persistence at university and well-being (Sirin, 2005; Rubin et al., 2019; Reynolds and Cruise, 2020). Several mismatches between the social upbringing of students with lower social status and requirements of the academic context may be responsible for this (Goudeau et al., 2024). Students with lower social status may explain negative experiences and behaviors resulting from such mismatches through inherent deficiencies, resulting in lowered well-being among students with lower social status (Goudeau et al., 2024). The current studies investigated whether motivational conflicts, a common phenomenon among students known to compromise well-being (Ratelle et al., 2005; Grund et al., 2021), are experienced differently depending on students’ social status. To date, the relation of students’ social status and their experience of motivational conflict has never been examined on an individual level before. Also, most research on effects of social status in education has been conducted in the U.S. The main goal of these studies was to examine whether a more frequent experience of and a stronger cognitive and affective reaction to motivational conflicts explains impaired well-being of students with lower social status compared to students with higher social status. Two cross-sectional studies were conducted in samples of German university students. Neither could support our mediation hypotheses. Yet, some hypotheses regarding the correlates of social status were supported which deserves further attention.

5.1 Social status dependent life realities and well-being

Both studies showed relations between social status and academic well-being. While in the first study, students with lower social status reported significantly lower general well-being and study satisfaction, students with lower social status in the second study reported lower satisfaction with their study’s content, but not other facets of study satisfaction, nor affect. These results partly support existing findings about the impaired well-being of this group of students in international (Allan et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2019; Allan et al., 2023) as well as in German samples (Janke et al., 2017; Reitegger et al., 2023). In line with existing findings, the current samples demonstrate that students with lower social status work more alongside their studies and take over more caring responsibilities (Reynolds and Cruise, 2020). These additional duties are likely to enhance stress and hinder a comparably pleasant university experience with less responsibilities. A concept for more flexible time management and individual shaping of schedules might allow students with lower social status to coordinate inner- and outer university requirements better and this way improve affective and cognitive well-being (Skidis and Earnest, 2024).

5.2 Motivational conflicts as an explanatory mechanism for well-being-related consequences of social status

Across studies, there was little no evidence for motivational conflicts as a mediating mechanism between students’ social status and their well-being. This may be due to methodological issues in sampling and operationalization, but also due to theoretical aspects which warrant further investigation.

Regarding methodological explanations for these null findings, a first issue pertains to the use of a measure investigating subjectively perceived relative social status, which mainly tapped into parental social status, but also students’ own relative status (Evans et al., 2022). Measures assessing students’ own current social status (e.g., their relative financial situation and support structures) should be investigated as indicators of social status as opposed to focusing on their family background.

A second issue was that although both samples showed variance in relative social status, this variance was still restricted with students with a low absolute social status being less represented. Several academic challenges arising in everyday academic life with a lack of material and social resources may not have been represented adequately in both samples. Future studies should therefore also assess absolute social status and ensure a stronger sampling of this underrepresented group at German universities.

The third methodological issue pertains to the operationalization of motivational action conflicts. Despite two different operationalizations frequently used in previous research, no relations were found. Yet, they may not have sufficiently captured the content dimensions in which students’ conflict experiences may differ.

There may also be theoretical arguments supporting a null relationship between students’ social status and motivational conflict experiences. Although the type of potential activities may differ depending on the amount of resources one has or relatively experiences, the amount of action alternatives does not necessarily vary, thus producing the same amount of motivational action conflicts—merely between different activities. Regarding the intensity of experiencing motivational conflicts, not only students with lower social status may feel they have more at stake in conflict situations—students with higher social status may feel the same via choking on expectations others may have due to their privileges.

While in study 1 hypotheses concerning the relations of social status and motivational conflict were not confirmed, study 2 showed interesting dynamics in line with our hypotheses: students with lower social status more often reported feeling like they should be doing something else while they were doing something they wanted to do (experiencing should conflicts) than students with higher social status. If they, however, did something they had to do while they simultaneously preferred doing something else, they report stronger negative affect than students with higher social status in a similar situation. Other than expected, and other than the literature suggests, reactivity appeared to be unrelated to social status. Even though the expected mediating mechanism of frequency of and reactivity after motivational conflicts for explaining academic well-being did not show in either of the studies, study 2 hinted at different conflict experiences in relation to students’ social status.

This finding carefully opens an opportunity for support of students with lower social status at university. Apparently, it is not the cognitive and affective (self-) evaluation in consequence of conflict experiences that calls for improvement but the acknowledgement of additional tasks and responsibilities that likely increase the frequency of should conflicts for students with lower social status. Future research could focus on further examining these conflicts with particular work-life conflict scales (for a review, please see Alameddine et al., 2023) or collecting daily diary data as seen in, e.g., Haar et al. (2018). If enjoyable activities and leisure time cannot be fully savoured as such because duties call constantly, this can lead to an enhanced stress level (Stone and O’Shea, 2013). It is therefore important to offer flexible opportunities for individualizing schedules and to provide resources that help organizing and prioritizing tasks so that leisure activities can be enjoyed without interference. This way, the overall well-being of students might improve, especially for students with lower social status.

To gain more knowledge about the role of social status in the experience of motivational conflicts, future research needs to examine further mediating psychological mechanisms. One such mechanism could be the quality of motivation that underlies students’ conflicting activities which has been found to influence the intensity of internal conflict that is experienced (Grund, 2013): Students with autonomous learning motivation tended to experience less internal conflict during a learning activity when confronted with an alternative social activity than students with controlled learning motivations (Grund, 2013). As discussed, research has shown that the quality of emotion can differ between students with lower and with higher social status (Irlbeck et al., 2014). This again could enhance differences in the experience of motivational conflicts.

These studies were the first to examine relations of social status, the experience of motivational conflicts and academic well-being in higher education. While some findings regarding students’ well-being depending on their social status were supported, others were not although literature suggested otherwise. This raises the question if findings concerning the correlates of social status can be generalized across different nations and across different levels within the same educational system.

5.3 Social status in higher education across contexts

Most findings regarding the impact of social status on the experience of university students come from the U.S., some of the literature in Goudeau et al. (2024) from France. Goudeau et al. (2024) themselves brought up concerns regarding the transnational generalizability of their model and existing findings. The fact that we mostly did not find relations between social status and well-being as expected highlights this issue. Even though in Western cultures educational systems are similar in some regards, each nation has its own characteristics (Janke et al., 2017). The German educational system is highly ability tracked, leading to different educational paths and career opportunities (Schindler and Bittmann, 2021). Although there are different possibilities to reach university and efforts have been taken to reduce inequality, the distribution of students with higher and lower social status remains unequal (Kracke et al., 2024). Students with lower social status who reach university have already overcome several hurdles and may already have built for themselves strategies and resources compensating for a lack of cultural capital or differing values, norms and identities passed on through families (Müller and Pollak, 2016). The selectivity of the German educational system might therefore minimize the effects of social status at university, while findings in schools are likely to be more profound.

Future research should hence carefully consider processes and mechanisms that explain effects of social status and how those can be compared or generalized among different countries and levels within the same educational systems. For Germany, Janke et al. (2024) as well as Marksteiner et al. (2019) showed that FGS report a lower sense of belonging to university, supporting international findings (Ostrove and Long, 2007). Other propositions of the Social Class–Academic Contexts Mismatch Model remain unreplicated in different countries and deserve further attention (Goudeau et al., 2024).

5.4 Limitations

Both studies followed an observational cross-sectional design. The findings therefore do not allow causal interpretations. In future research, experimental or cross-lagged designs assessing social status and the relevant outcomes over time may allow testing and comparing relations across the measurement period, offering stronger evidence for a causal direction. This would also allow assessing different want and should conflict experiences instead of using vignettes (study 1) or a single biographical experience (study 2). Possibly, relations between social status and motivational conflicts become more relevant if more different aspects and conflicts of everyday life are portrayed.

This study did not explicitly test interventions to improve students’ well-being dependent on their social background. Rather, it investigated motivational action conflicts as one possible mechanism which may explain differences in well-being depending on students’ social background. Since this assumption did not hold, it does not provide a starting point for suggestions to improve general well-being among students with different social status. Yet, our data provided some tentative ideas concerning helpful initiatives for the future beyond motivational action conflicts, which are discussed above.

Social status was assessed by the CSCS (Evans et al., 2022), a relative measure of social status, which does not offer information on absolute social status. While this relative measure allows testing our hypotheses regarding the relations of social status and motivational conflict and well-being, information on the objective social status of our participants is lacking, nonetheless. Both samples contained a substantial number of FGS, however, they descriptively did not portray the ratio of FGS and CGS at German universities (Kerst et al., 2024). This potential variance restriction might also have added to the in part weak relations of social status. Yet, the CSCS was used as opposed to objective indicators both due to its subjective nature and to root estimations on knowledge and evaluations of family background the students have (Evans et al., 2022). For traditional objective measures, such as parental income, knowledge is required which students may not have (Jetten et al., 2008). Yet, future research including more objective indicators of social status and alternative sources of information (e.g., parents) may be useful in addition to subjective perception of social status. In sum, results on relations between social status and motivational and well-being related consequences were not fully consistent. Thus, further replication studies using larger and potentially more representative samples, additional absolute measures for social status, comparing further suggested mechanisms explaining differences in well-being dependent on social status, and comparing educational contexts are warranted (Goudeau et al., 2024).

6 Conclusion

In line with previous studies, students with lower social status reported lower general well-being and study satisfaction. Thus, despite efforts undertaken to reduce the impact of socioeconomic background on academic success, well-being still seems somewhat lower for students with lower social status. Even though previous studies and theory suggest otherwise, we could not show that a differing frequency of or reactivity after motivational conflicts explain this impediment. Different (status related) life realities, however, might lead to different conflict frequencies and affective reactions as hypothesized. Acknowledging the persisting social inequality in higher education and aiming to uncover psychological mechanisms that reinforce this disproportion remains an important goal of future research. This study also cautions against the transnational generalizability of effects of social status in higher education.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Marburg university’s institutional review board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MSw: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MSc: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this study received funding for open access publishing by the Open Access Fund of Marburg University. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1644584/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Preregistered at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BV9PF

2. ^Preregistered at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DZV3J

References

Alameddine, M., Al-Yateem, N., Bou-Karroum, K., Hijazi, H., Al Marzouqi, A., and Al-Adawi, S. (2023). Measurement of work-life balance: a scoping review with a focus on the health sector. J. Nurs. Manag. 1:3666224. doi: 10.1155/2023/3666224

Allan, B. A., Garriott, P. O., and Keene, C. N. (2016). Outcomes of social class and classism in first- and continuing-generation college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 63, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/cou0000160

Allan, B. A., Garriott, P., Ko, S. –. J., Sterling, H. M., and Case, A. S. (2023). Classism, work volition, life satisfaction, and academic satisfaction in college students: a longitudinal study. J. Divers. High. Educ. 16, 66–75. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000221

Ayala, C., and Striplen, A. (2002) A career introduction model for first-generation college Freshman students. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED469996 (Accessed January 23, 2025).

Baranik, L. E., Barron, K. E., and Finney, S. J. (2010). Examining specific versus general measures of achievement goals. Hum. Perform. 23, 155–172. doi: 10.1080/08959281003622180

Bauer, V. (2022). Eine Frage der Messung sozialer Herkunft? Kulturelle Passung als Erklärung für soziale Disparitäten der Studienintention. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

Bauer, C. A., Job, V., and Hannover, B. (2023). Who gets to see themselves as talented? Biased self-concepts contribute to first-generation students' disadvantage in talent-focused environments. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 108:104501. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104501

Beilock, S. L., Ryell, R. J., and McConnell, A. R. (2007). Stereotype threat and working memory: mechanisms, alleviation, and spillover. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 136, 256–276. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.2.256

Brassler, N. K., Grund, A., Hilckmann, K., and Fries, S. (2016). Impairments in learning due to motivational conflict: situation really matters. Educ. Psychol. 36, 1323–1336. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2015.1113235

Capelle, J. D., Grunschel, C., Bachmann, O., Knappe, M., and Fries, S. (2022). Multiple action options in the context of time: when exams approach, students study more and experience fewer motivational conflicts. Motiv. Emot. 46, 16–37. doi: 10.1007/s11031-021-09912-3

Capelle, J. D., Grunschel, C., and Fries, S. (2020) Selbstregulation im Alltag von Studierenden (SriAS) – Teil 2. Studienmotivation : Karlsruher Institut für Technologie. Available online at: https://publikationen.bibliothek.kit.edu/1000125784

Collier, P. J., and Morgan, D. L. (2008). ‘“Is that paper really due today?”: differences in first-generation and traditional college students’ understandings of faculty expectations’. High. Educ. 55, 425–446. doi: 10.1007/s10734-007-9065-5

Covarrubias, R., et al. (2019). “You never become fully independent”: family roles and Independence in first-generation college students. J. Adolesc. Res. 34, 381–410. doi: 10.1177/0743558418788402

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

DeepL SE (2024) DeepL. Available online at: https://www.deepl.com/de/translator (Accessed November 17, 2023).

Demakakos, P., Nazroo, J., Breeze, E., and Marmot, M. (2008). Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038

Dietz, F., Schmid, S., and Fries, S. (2005). Lernen oder Freunde treffen? Lernmotivation unter den Bedingungen multipler Handlungsoptionen. Z. Pädagog. Psychol. 19, 173–189. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652.19.3.173

Ditton, H., Bayer, M., and Wohlkinger, F. (2019). Structural and motivational mechanisms of academic achievement: a mediation model of social-background effects on academic achievement. Br. J. Sociol. 70, 1276–1296. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12506

Easterbrook, M. J., Nieuwenhuis, M., Fox, K. J., Harris, P. R., and Banerjee, R. (2022). People like me don’t do well at school’: the roles of identity compatibility and school context in explaining the socioeconomic attainment gap.’. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 1178–1195. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12494

Eid, M., Gollwitzer, M., and Schmitt, M. (2017). Statistik und Forschungsmethoden. 5th Edn. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag.

Evans, O., McGuffog, R., Gendi, M., and Rubin, M. (2022). A first class measure: evidence for a comprehensive social class scale in higher education populations. Res. High. Educ. 63, 1427–1452. doi: 10.1007/s11162-022-09693-9

Fries, S., Schmid, S., and Hofer, M. (2007). On the relationship between value orientation, valences, and academic achievement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 22, 201–216. doi: 10.1007/BF03173522

Gaddis, S. M. (2013). The influence of habitus in the relationship between cultural capital and academic achievement. Soc. Sci. Res. 42, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.002

Geißler, R.. (2014) Bildungsexpansion und Bildungschancen. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/izpb/198031/bildungsexpansion-und-bildungschancen/?p=all (Accessed October 4, 2023).

Goudeau, S., and Croizet, J.-C. (2017). Hidden advantages and disadvantages of social class. Psychol. Sci. 28, 162–170. doi: 10.1177/0956797616676600

Goudeau, S., Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., Darnon, C., Croizet, J. C., and Cimpian, A. (2024). What causes social class disparities in education? The role of the mismatches between academic contexts and working-class socialization contexts and how the effects of these mismatches are explained. Psychol. Rev. 132, 380–403. doi: 10.1037/rev0000473

Granfield, R. (1991). Making it by faking it: working-class students in an elite academic environment. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 20, 331–351. doi: 10.1177/089124191020003005

Grund, A. (2013). Motivational profiles in study–leisure conflicts: Quality and quantity of motivation matter. Learn. Individ. Diffe. 26, 201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.009

Grund, A., Brassler, N. K., and Fries, S. (2014). ‘Torn between study and leisure: how motivational conflicts relate to students’ academic and social adaptation. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 242–257. doi: 10.1037/a0034400

Grund, A., and Fries, S. (2012). Motivational interference in study–leisure conflicts: how opportunity costs affect the self-regulation of university students. Educ. Psychol. 32, 589–612. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2012.674005

Grund, A., and Fries, S. (2014). ‘Study and leisure interference as mediators between students’ self-control capacities and their domain-specific functioning and general well-being.’. Learn. Instr. 31, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.12.005

Grund, A., Schmid, S., and Fries, S. (2015a). Studying against your will: motivational interference in action. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 41, 209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.003

Grund, A., Grunschel, C., Bruhn, D., and Fries, S. (2015b). Torn between want and should: an experience-sampling study on motivational conflict, well-being, self-control, and mindfulness. Motiv. Emot. 39, 506–520. doi: 10.1007/s11031-015-9476-z

Grund, A., Senker, K., Dietrich, J., Fries, S., and Galla, B. M. (2021). The comprehensive mindfulness experience: a typological approach to the potential benefits of mindfulness for dealing with motivational conflicts. Motiv. Sci. 7, 410–423. doi: 10.1037/mot0000239

Haar, J. M., Roche, M., and Brummelhuis, L. (2018). A daily diary study of work-life balance in managers: utilizing a daily process model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 29, 2659–2681. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1314311

Hicken, M. T., Lee, H., Morenoff, J., House, J. S., and Williams, D. R. (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: reconsidering the role of chronic stress. Am. J. Public Health 104, 117–123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301395

Hofer, M., Fries, S., and Grund, A. (2017). Multiple Ziele und Lernmotivation: Das Forschungsprogramm “Theorie motivationaler Handlungskonflikte”. Z. Pädagog. Psychol. 31, 69–85. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000197

Hofer, M., Reinders, H., Fries, S., Clausen, M., Schmid, S., and Dietz, F. (2005). Die Theorie motivationaler Handlungskonflikte. Ein differenzieller Ansatz zum Zusammenhang zwischen Werten und schulischer Lernmotivation. Z. Pädagog. 51, 326–341. doi: 10.25656/01:4758

House, L. A., Neal, C., and Kolb, J. (2020). Supporting the mental health needs of first generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 34, 157–167. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2019.1578940

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Inzlicht, M., and Kang, S. K. (2010). Stereotype threat spillover: how coping with threats to social identity affects aggression, eating, decision making, and attention. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 467–481. doi: 10.1037/a0018951

Inzlicht, M., McKay, L., and Aronson, J. (2006). Stigma as ego depletion: how being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychol. Sci. 17, 262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x

Irlbeck, E., Adams, S., Akers, C., Burris, S., and Jones, S. (2014). First generation college students: motivations and support systems. J. Agric. Educ. 55, 154–166. doi: 10.5032/jae.2014.02154

Janke, S., Messerer, L. A. S., Merkle, B., and Rudert, S. C. (2024). Why do minority students feel they don’t fit in? Migration background and parental education differentially predict social ostracism and belongingness. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 27, 278–299. doi: 10.1177/13684302221142781