- 1Department of English Language and Literature, University of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo

- 2School of Education, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, United States

Partnering with students to co-construct curriculum is an initiative that is gaining considerable attention due to its potential to transform higher education. The aim of this longitudinal research was to explore the experiences of five MA students who were empowered to challenge the conventional pedagogy of their institution by engaging in a student-faculty partnership to reform the curriculum. As part of this novel shift, students investigated the department's pedagogical issues, seizing the chance to voice their concerns, recommend solutions, and contribute to the curriculum co-construction. This study employed a qualitative research design using semi-structured interviews obtained at two distinct timeframes, paired with instructors' reflective journals which were analyzed thematically. The findings indicate that the trajectory of such an initiative was affected by the entrenched norms of the institution such as fear of retaliation, and students' perceived lack of self-efficacy to influence change in the curriculum. Also, the unprecedented experience of questioning authority changed power dynamics, evoking a sense of discomfort for students. Nevertheless, the benefits of this partnership outweighed the obstacles. This study demonstrates that involvement in such initiatives cultivated a sense of agency and ownership, empowering students not only to make immediate adjustments to their study program but create a legacy for positive change in the academic experiences of successive generations. These results carry implications on the potential impact inclusive and collaborative pedagogies can have on breaking entrenched educational practices to progressively transform education.

1 Introduction

1.1 Student voices

In an increasingly competitive globalized economic and political environment, it has become crucial for universities to adapt their curricula and pedagogy in order to better equip their students to succeed in their careers and further education (Brooman et al., 2015; O'Neill, 2015; Zajda, 2023). Furthermore, in this environment universities are competing with each other to attract international students who demand modern curricula, modern pedagogy, and modern ways of enhancing their active engagement in their education and university experience. Higher education in many countries has taken on a business model, with students as “consumers” and programs of study being “products” to be “sold” to student consumers (Naylor et al., 2021). As a result of this changing environment, universities must adopt more aspects of democratic curricula and classrooms that offer greater opportunities for student voices to be heard and student-faculty partnerships to be fostered if they hope to remain relevant and attractive to students. However, in education systems marked by adversity, political instability and conflict, the adoption of democratic co-created curricula remains a pressing challenge. Sharing power in co-creating curricula can be viewed as unprecedented in entrenched teacher-centered traditions, as is the case of Kosovo. The current education system of Kosovo continues to echo the legacy of the 1990′s underground schooling, a decade characterized by global pedagogical isolation, limited teaching resources and adherence to reproduction of knowledge. The armed conflict that followed further disrupted not only the physical infrastructure but also the stability of the education system. Although reforms have been introduced since the end of the 1999 conflict to modernize teaching and encourage student-centered practices, the progress has been slow. Many teachers and former students of the University of Prishtina (the oldest and only public university at the time in Kosovo) molded by the underground system, who lack exposure to professional growth beyond this context, and currently hold key positions in teaching and decision-making within the university, continue to shape the present by inhibiting the system's capacities to embrace innovation and transformation. On the other hand, students within this setting are accustomed to expect traditional hierarchical classroom dynamics, hence being invited to co-create curricula with teachers can be overwhelming and unfamiliar.

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of MA-level students who participated in a class project in which they collected the ideas of students throughout the department and recommended improvements to the curricula of the English Language and Literature Department of the University of Prishtina, as part of a student-teacher partnership initiative. This represents the first time any such project, in which students were co-constructing an entire curriculum and collaborating with faculty members, had been undertaken in any department in this university. This study explores students' perspectives and understandings of this curriculum co-construction project as they sought to inform changes in this department. While the curriculum revisions were the outcome of this initiative, this study does not evaluate the changes; rather, it examines the significance of the process itself—how students understood their agency, interpreted the meaning of their contributions, and developed a stronger sense of ownership and empowerment. To contextualize students' experiences, Table 1 highlights the major projects that have influenced the ongoing curriculum modifications.

This article responds to the following research questions:

• What were the experiences and perspectives of the students who participated in this class project?

• What supported their voices?

• What suppressed their voices?

2 Literature review

2.1 Student voice

The concept of student voice is central to any discussion of student participation in student/staff partnerships and curriculum development projects. Student voice extends the concepts of agency and elected student government into areas of teaching and learning, and includes means through which students are involved with “analyzing teaching and learning such that their voices and perspectives inform classroom practices” (Cook-Sather, 2020, p. 183). (Matthews and Dollinger 2023) describe situations in which “students share responsibility for learning, teaching, and educational endeavors with teachers/staff/administrators and each other” (p. 561).

This article defines student voice as one in which students partner with faculty in deciding what and how learning will occur in their classrooms; that students have a role in designing and delivering the curriculum. This article extends student voice beyond the typical end-of-course evaluations that are widely used in higher education but rarely result in any meaningful change or improvements in teaching or learning (Blair and Valdez Noel, 2014; Carey, 2013; Eckhaus and Davidovitch, 2023).

2.2 Student involvement in curriculum design

Although many articles address student involvement in curriculum design from a conceptual and theoretical perspective (Bron and Veugelers, 2014; Dollinger et al., 2018) peer-reviewed research on this topic is scant. Several studies report on redesign of a single class (Bell et al., 2019; Chilvers et al., 2021; Nixon and Williams, 2014). Although some of these studies found that students were relegated to an informant role voicing complaints (Carey, 2013), other students found the process to be transformative in re-evaluating roles and responsibilities, as the redesign transcended mere content and assignments and included student ideas about assignments, assessment, and ways in which learning would occur (Bergmark and Westman, 2016).

The benefits of student voice and partnerships cannot be denied, and range from enhanced engagement (Bovill et al., 2016; Jagersma, 2010) and enhanced student learning and grades (Brooman et al., 2015; Jagersma, 2010). (Marquis et al. 2016, p. 9) found that collaborations between faculty and students “resulted in work that was better than it might have been in absence of partnership” due to inclusion of multiple perspectives. (Dollinger and Lodge 2020) found that partnerships that promoted student voice and choice enhanced engagement, enthusiasm, and relationships on the parts of both students and staff. Benefits also include embracing the rights of students to be heard and advancing democratic values in the classroom (Bergmark and Westman, 2016).

2.3 Barriers to student voice in curriculum design

Despite the advantages of including student voice in curriculum design, multiple factors silence student voice, from both the student perspective and the faculty/staff/administration perspective. Students silence themselves for fear of retaliation (Bolkan and Goodboy, 2013) and because they do not see selves as legitimate contributors (Bolkan and Goodboy, 2013; Tuhkala et al., 2021). Students often see faculty as unapproachable or intimidating (Bolkan and Goodboy, 2013), and often lack time and resources (Bell et al., 2019; Bovill et al., 2016; Chilvers et al., 2021), especially if they believe that nothing will change (Bolkan and Goodboy, 2013; Tuhkala et al., 2021). Faculty also feel that students are not legitimate contributors (Martens et al., 2020; Tuhkala et al., 2021) and that the institution lacks flexibility in enacting change (Bell et al., 2019; Bovill et al., 2016). Many articles discussed the reluctance of faculty to relinquish control over instruction, that including student voice in curriculum design challenged traditional roles of instructor and students alike and required a change in institutional culture (Bergmark and Westman, 2016; Bovill et al., 2009, 2016; Carey, 2013; Chilvers et al., 2021; Marquis et al., 2016; Martens et al., 2020; Nixon and Williams, 2014). Faculty reluctance to the change in roles was also discussed in several articles (Price and Regehr, 2022; Tuhkala et al., 2021).

This study transcends the restructuring of a single class (Bell et al., 2019; Chilvers et al., 2021; Nixon and Williams, 2014) to encompass the entire curriculum. Unlike other studies included in this literature review, students took the lead rather than being closely supervised by a faculty member. Further, no studies outside of the US could be located. This study fills these gaps.

3 Methods

3.1 Course context

The “Working in English” course was designed to connect academia with the labor market i.e., students were foreseen to individually engage in authentic research in their workplace. This apprenticeship-style model was part of a recently condensed Integrated MA Program in Linguistics that aimed at creating opportunities for students to combine academic training with on-the-job skills. However, due to challenges in establishing official partnerships with the labor market in due time, a decision to use the English Language and Literature Department as the site to conduct research was jointly taken by the course instructors and students. This decision was driven by familiarity with the context and easy access to potential participants, making the research process more manageable. In addition, it was part of a consultative approach used throughout the course where every decision, including deadlines and workflows were taken collaboratively between students and the instructors. These course actions were a result of assigned readings on “voice and choice” and critical discussion conducted in the classroom. Also, in alignment with the principles of co-creation, this approach aimed at promoting not only a collaborative and inclusive learning environment but also a shared sense of accountability, disrupting thus the conventional pedagogical norms of the education system, deeply affected by political unrest and repercussion of an armed conflict, which silence student agency, express skepticism toward innovation and resist change.

Moreover, with the transition of the BA program from three to four years, the MA program was reduced from a two-year into a one-year program. This abrupt compression resulted in condensed syllabi, intensifying the workload for both students and faculty members, and placing an unexpected pressure for all stakeholders to comply with changes. In particular, students found themselves in a difficult position of adjustment- navigating the rapid changes caused widespread confusion and frustration.

In light of these challenges, students proposed to address the confusion and frustration they were experiencing to inform improvements to the program for future cohorts and staff. Despite the instructors' caution against this focus, the approval was granted under the framework of student-teacher partnership. In addition, students extended their inquiry to the BA program in order to enhance the curricula in both levels through student lenses. This approach was in alignment with the original plan of conducting research that would benefit an institution- in this case, presenting research findings and recommendations to faculty members would benefit directly the English Language and Literature Department.

The semester-long course was co-taught by two instructors: Instructor 1, officially listed as the person handling all course-related matters and grading, was responsible for delivering lectures and laying the foundation for learning. Instructor 2 supported the course by delivering practical classes during which students practiced the theoretical concepts covered in lectures and received feedback while working on their projects.

3.2 Research design

This study employed a qualitative research design with the aim of exploring the process in which students were involved in the course and “hear their voices” (Creswell and Poth, 2018, p. 45). It used semi-structured interviews as primary data (Dörnyei, 2007) and reflective journals kept by course instructors as secondary data (Creswell and Creswell, 2018), which show the contemplation of course instructors over the process that took place in the classroom (Denzin and Lincoln, 2017). The interviews were conducted with study participants at two points in time: during participation in research projects, and after a year the projects were completed. This longitudinal approach aimed at exploring the participants' evolving experiences with the novel pedagogical approach of “voice and choice” (Brooman et al., 2015). It also ensured that no power relation could influence the data.

Reflective journals kept independently by both course instructors were used to shed more light on the experiences of participants with the “voice and choice” approach. To prevent any bias and cross-contamination of data, the instructors refrained from sharing their journal entries until the data analysis process began.

3.3 Participants

To select participants for the study and give each student an equal opportunity to participate and contribute to the study, an email was sent to all twelve students who attended the ‘Working in English' course. The email outlined the aim of the study, the nature of the research, and the ethical considerations including confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntary participation. Interested individuals responded to the email and interview schedules were set. Prior to the interview, a consent form was sent to each participant via email and written consent was obtained. Also, to ensure that participants understood their rights, the researchers invited discussion to clarify any concerns or questions.

In the first round of interviews, five MA students participated in the study, four females and a male. By the second round of the interview, one of the participants had already withdrawn from the program and was therefore unreachable. The second interviews were conducted with the remaining four participants. All interviews were conducted via Zoom. To protect participants' personal information, the researchers assigned codes to each of them.

3.4 Data collection

Data was collected from two rounds of interviews conducted by an American researcher: at the beginning of the project and again after one year, upon the students' anticipated graduation. She was well-acquainted with the participants because as a visiting scholar, she had previously taught them a course. The decision to include her in the study was motivated by the fact that she was no longer part of the institution, hence she was free of any potential power dynamics. Moreover, her involvement in the process and her expertise would bring an external perspective and contribute to maintaining scientific rigor.

Both sets of interviews were conducted via Zoom. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The first set of interviews was conducted mid-way through the course. The aim was to capture participants' initial experiences with the ‘voice and choice' approach, including the benefits and challenges they faced in taking charge of their learning. The second set of interviews was conducted a year after the course and grading was completed. The aim was to capture the overall experience after having given the participants some time to reflect on the entire journey.

Reflective journals, kept by both instructors throughout the course, were shared with the American researcher to complement the findings from the interviews and enhance the depth of analysis. The journals were kept independently by both instructors; the documented observations, thoughts and feelings, were first handwritten and later transcribed into Word documents to be shared for data analysis.

3.5 Data analysis

Data analysis included a collaborative effort between the three researchers. Initially, interview transcripts had been coded and re-coded by the American researcher. Her neutral role in the study enhanced objectivity and unbiased analysis of the data. Through the systematic readings of the transcriptions, she conducted a thematic analysis of the interview transcripts. She identified the emerging themes and completed the first draft of data analysis. The two instructors were then invited to give their input and elaborate on the findings drawing on their insights of the context and their involvement in delivering the course. This collaborative approach of reviewing interview transcripts and reflective journals ultimately enhanced data validation and reliability, allowing for a more comprehensive and nuanced analysis.

3.6 Ethical issues

Informed consent was obtained from the interviewees prior to the beginning of the interviews. All interviewees agreed to be videotaped; one chose to turn off their camera for privacy reasons. Interviewees were informed how their data would be used, that their confidentiality would be protected and respected, that the topic is related to their involvement in the class project, and that they could decline to respond to any question. Interviewees were also told they could withdraw from the study at any time. As the University of Prishtina did not have an Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at the time of research, prior approval could not be obtained. However, following the later establishment of Scientific Research Ethics Commission (SREC), the researchers submitted a request to review the ethical aspects of the procedures used in the study. Upon the study procedure review, while SREC could not grant ethical approval retrospectively, it issued a confirmation letter acknowledging that the study aligned with recognized standards of ethical conduct.

Moreover, all three researchers are well-versed in research ethics; the two researchers from the University of Prishtina have PhDs from Western universities, and the US researcher has up-to-date CITI certification. The research project aligns with the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. Throughout this article, pseudonyms have been used, and all identifying information has been removed; this includes the use of gender-neutral pronouns.

4 Findings

4.1 Empowerment and ownership

One of the key benefits of the project was the feelings of confidence and empowerment that the process of conducting research helped them build. While involved in research, students were able to grasp how the process functions, to face the challenges that occur in the process, and how to overcome them. This made them aware of the necessity to address the challenges through informed and practical solutions. Students' insights into “… what actually works …” (S3, I/2) are vital; hence, their involvement in the project is crucial. Their first-hand experience and understanding of educational demands makes students key contributors to the development and improvement of curricula in the modern education setting.

Considering the gap between the students' and faculty members' experiences, it is important to incorporate students' perspective. Despite their knowledge and experience, faculty frequently seem to fail to fully comply their teaching practice with the needs and challenges that students have, as one of the interviewees mentioned:

getting the perspective of students it is a crucial, a very crucial factor, because we, you cannot expect teachers to constantly know everything that is going on in the current in the current in the current period that we are living in … There is a gap between what students are experiencing and what teachers do have experience in the past (S3, I/2).

Therefore, students' contribution is seen as a “power to change” (S1, I/2) and is essential to the effectiveness and relevance of the educational programs.

The process of data collection with BA and MA students revealed that students can have the power to change the teaching process through active participation. In spite of numerous struggles and benefits, each student cohort reported to have experienced improvements in the learning environment, thus showing that the English department takes into consideration student feedback:

I could see that there that there were more benefits than there were challenges. So if that is the still the kind of the the improvement that that all generations are actually experiencing. Then I think that at this stage the UP, the UP, the Department of English is doing better than before” (S3, I/2).

This suggests that the improvements that took place in each generation highlight the positive aspect of the collaboration between students and faculty, thus fostering the shared responsibility and progress. In addition, a more dynamic and effective learning environment is created as a result of this collaboration.

4.2 Changes in their own study program – giving feedback

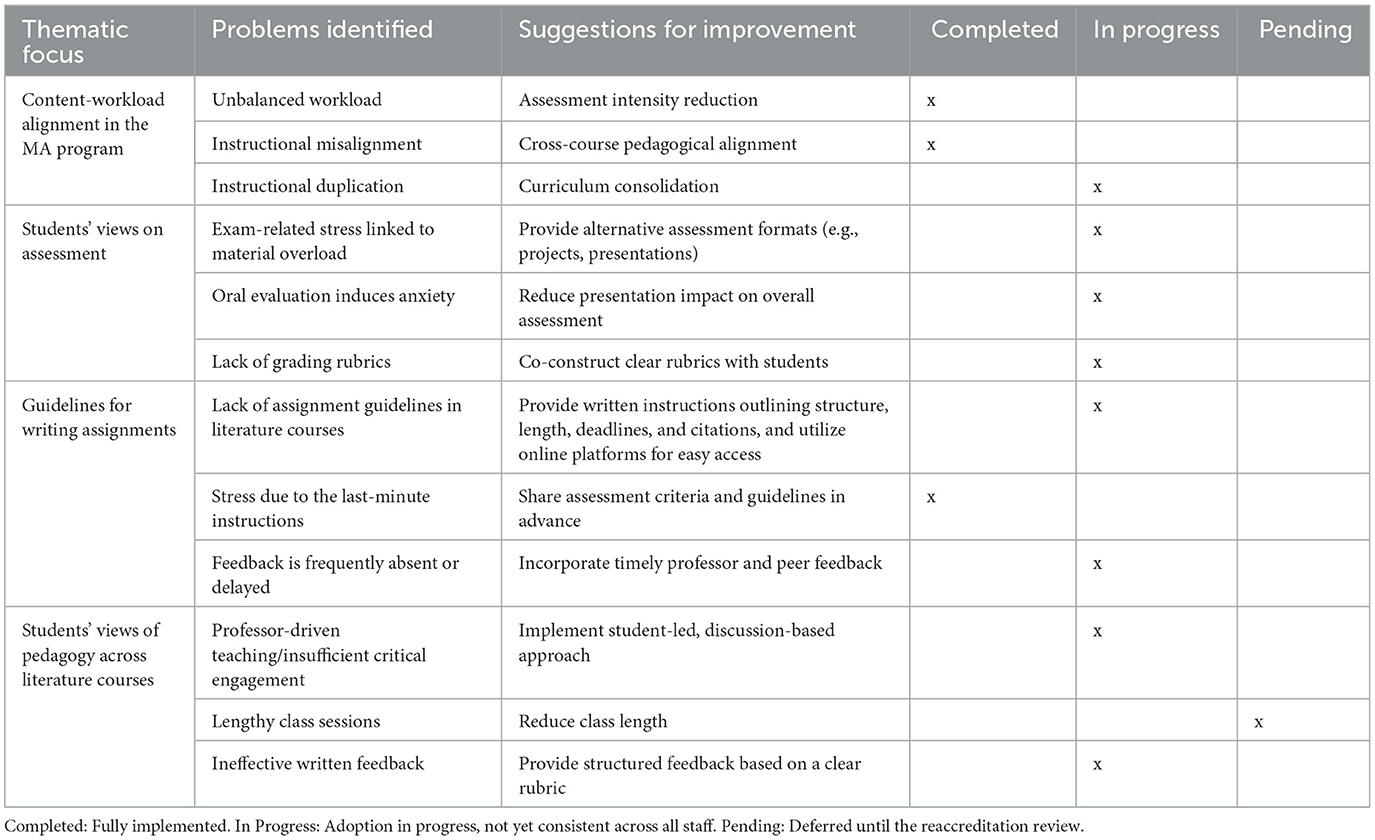

As summarized in Table 1, the student group feedback centered on course workload, assessment, guidelines for writing assignments, and pedagogy. The feedback encompassed a wide range of suggestions for improvements to the program to enhance student success. These suggestions included utilizing alternative assessments to replace exams, providing clear guidelines for assignments, implementing student-led, discussion-based pedagogical approaches in the classroom, and curriculum consolidation. In addition to highlighting the diversity of perspectives, Table 1 leads into deeper exploration of individual student perspectives presented in the following analysis.

Participation in the research project empowered the participants to make changes in their own study program. An example is the removal of the final exam in one of the courses, which resulted from the negotiation process with a faculty member. This shows that students' influence can be substantial in making a difference in the study program, when they are given a chance, hence making the study program more suited to their needs. As one of the interviewees pointed out, “we actually got to get rid of the final exam when we talked to the Professor, because it was a lot of workload” (S2, I/2).

This experience demonstrates that by empowering students, one recognizes the power that students' voices can have in the modern educational system, which means that students are capable of enacting changes and contributing to the enhancement of academic curricula. Further, student engagement in the improvement in the learning environment may impact their feeling of ownership and responsibility. A study participant noted that a peer in an interview “had quite a knowledge to share” and was “very engaged” (S3, I/2) in providing information and opinions. The motivation to share information comes from feeling heard, valued, and safe to discuss things with their peers compared to faculty who is viewed as more authoritarian. These kinds of opportunities will engage students in a more open and honest dialogue, increasing their contribution. As one student stated: “I think that if that is done more often students will be more open to give feedback …” (S4, I/2).

According to most participants, they were motivated to make improvements, i.e., they were “looking forward to making this situation better for other students” (S4, I/1)…even though they were nearing graduation and hence would not witness the changes, i.e., “maybe we won't experience it” (S1, I/1). They were also aware that they would not benefit directly from the changes that might occur. Driven by the desire to leave a positive legacy behind, students demonstrate a sense of responsibility for the community, and as a result, they become more engaged in the process.

4.3 Ownership from presenting findings

Students' sense of ownership is further boosted by the opportunity to present the findings of their research to the faculty. This process enables students to discuss with individuals in positions of authority and influence, which could result in their concerns being taken more seriously. As one of the participants mentioned, “it feels good to be able to show, to tell, and give our voice to the professors” (S4, I/1), even though it is unclear if the faculty will be appreciative of the feedback.

However, participants' responses suggest that the learning environment in the department is characterized by a setting in which resistance and openness to change cohabit. According to them, most of the faculty is open to feedback, care about students' perspectives and is willing to enhance the learning environment. The discussions with these faculty members could offer the students the opportunity to feel encouraged to share their opinions and to negotiate with them. On the other hand, due to their long-established teaching methodology, a small number of faculty is viewed as resistant to altering their practice, as one of the participants stated “I strongly believe that if I approach one professor they might not change. They are used to that method of teaching” (S1, I/2). Consequently, the students' impression of their rigidity makes the process of presenting findings to these faculty as discouraging, as they do not believe that their feedback will be taken into consideration and will have any positive impact.

Nevertheless, this shows that student engagement in presenting their research findings to the faculty members can motivate them, as it can result in improvements in the curriculum. In this way, students are allowed to advocate for themselves and to enable future student cohorts to be part of an enhanced academic environment.

Furthermore, this research project focused on the need to find and suggest solutions. This aspect of the project was seen as crucial in developing their problem-solving approach, which they can apply in their future settings. This can be illustrated by the following statement:

One of the greatest yeah points in the background, this in this research that's actually what working in English is we are finding an issue and we are trying to provide students or the university with a solution (S3, I/1).

By being given voice and choice, students felt motivated to contribute to the improvement of the academic setting in the department. Active participation in the process and collaboration with the faculty led toward an effective learning environment and growth of self-efficacy in conducting qualitative research, thus strengthening their sense of ownership and responsibility toward the community.

4.4 The interplay of power dynamics and collaboration

4.4.1 Navigating collaborative strides

During the first interviews, two participants reported that working in groups to conduct research was going well. One of them said that “until now I'm loving the group work” (S3, I/1), acknowledging many disagreements in the process that were worked out by “communicating our ideas, and we we had, we were very comfortable in sharing, even if we had disagreements.” (S3, I/2). The other student said that “the three of us are interested to make this work, so I am quite hopeful that it's going to go well”, emphasizing the benefits of multiple perspectives “that you yourself might not have thought so” (S4, I/2).

A less favorable experience with group work was reported by the other three students, who worked together in the same group, but whose journey was characterized by uncertainty, tension, and anxiety. From the onset, the divergent viewpoints on the organization of group work created challenges that required the instructors' intervention.

it's also stressful in the sense that that there is not very good teamwork within the group. Okay, and we cannot come to an agreement for almost everything and sometimes the professors have to get involved to help us (S2, I/1).

In the first interview, this student expressed significant stress about the project, using the word stress nine times during the interview. This student and another student in the same group shared similar viewpoints and worked well with each other because they “would discuss [things]” (S2, I/2) and were “open to feedback and change” (S1, I/2). The third member of the group, however, expressed concerns regarding the work that the other two members were employing and doubted their capabilities (S5, I/1). This student was particularly worried about the quality and ownership of the writing, dismayed that the other two students had edited one's writing and “basically just paraphrased what I had written even in the worst manner” (S5, I/1). Both instructors noticed the conflict in this group, one saying that the “reliance on external input indicates poor teamwork within the group” (I2). Ultimately, a joint decision was made to separate the third member from the other two so the project could proceed. The student who expressed so much stress and anxiety in the first interview expressed no stress whatsoever in the second interview, suggesting that group dynamics can impact students in multiple ways.

4.4.2 The ripple effect: from excitement to mistrust

From the first interviews, participants expressed enthusiasm about presenting research findings to faculty members. For example, two students were eager to display the findings in front of an audience: “I would very much like it to make it as a presentation” (S1, I/1) and, “I think it will be interesting to actually if we have all of them [faculty members] in one in one place and present present our results to them” (S3, I/1).

However, two of the participants questioned whether sharing findings would have any meaningful impact given the existing student-faculty dynamic. As one participant remarked, “with the rest of professors we cannot discuss things openly” (S5, I/1), while the other one stated “we don't know how much we are protected when we are doing this type of research in terms of will we be reprimanded for this research?” (S2, I/1).

As this approach was not customary practice at the institution, one of the students perceived the experience of addressing the MA program's shortcomings as exploitation of students, commenting that “… instead of studying and learning, we are doing their [faculties] work” (S5, I/1). This student further commented that one doubts students' role in addressing deficiencies of the program since the student-faculty partnership framework is not part of the institutional culture:

…but I'm not sure the students are here to fix you know, especially when student voice in our university is not that, you know students are normally not perceived as part of this process (S5, I/1).

Instructor 1 observed that the perceived lack of clarity with the initiative resulted in varying interpretations and struggles:

I am aware that students are not accustomed to have a voice and choice in their courses. Suddenly they found themselves in the driver's seat and they had to make numerous decision that impacted the direction of their learning. It is understandable that with autonomy they had more responsibilities. They have been used to structured learning environments throughout their education, thus I strongly believe that they consider this journey as chaotic and overwhelming because they had to make informed decisions, which in the past were made exclusively by the teachers.

During the second interview, the ripple effect is reported to have taken place. Students collectively decided to withdraw from presenting findings to the faculty members. The fear of reprisal harbored by one of the groups impacted the decision of the entire cohort:

The other students' topics were very like there was some constructive criticism for the professors, so they felt a bit unsure to share them in front of the professors, and that's why I think this whole idea was kind of annulled with our request (S4, I/2).

The hesitancy across the cohort grew as students discussed concerns over the lack of open-mindedness among some of the faculty members:

I think that that there are also other other professors that might kind of feel reluctant to change their way of teaching or giving guidelines because they think that they or that their method is the right method. So I'm not sure exactly what kind of reaction would we get (S3, I/2).

Although the students consented to share their research findings to staff via written reports, due to one group's discomfort in revealing their identities, the entire cohort, in light of “voice and choice” principles, decided to share their reports anonymously with staff. Subsequently, the course instructors shared the findings with the staff and facilitated discussion that aimed at making changes based on student recommendations.

4.4.3 Fear of reprisal and institutional distrust as barriers to full participation

In interviews, most participants expressed concern that their recommendations would be poorly received by the faculty. They specifically mentioned fear of reprisals or retribution from faculty if the recommendations were perceived as critical or unfavorable. One participant remarked:

I, the students were afraid that the professors were not going to accept that criticism, that well, plus we were still, this is very important, we were still students within the university. So there was that kind of fear that you know I mean, it's not that there it was gonna happen, but some students might have been afraid that the the professors could have gotten revenge (S4, I/2).

Also, both course instructors noticed a change in students' behavior and approach toward the initiative. It became evident to them that students felt insecure:

When asked why the sudden change of heart one [the student representative] replied that they are afraid of retaliation (I1).

They are worried about how professors might react to criticism or suggestions, fearing negative penalties (I2).

Given the context, Instructor 1 deliberated further: “I feel them….” However, in analyzing the situation further, she contended that this might be an overreaction as the majority of faculty members were unlikely to resort to retaliation. She further delved into the underlying factors that could have influenced the decision by making the following remarks:

…it does not seem that there was a reason for concern, except for the group who was doing the MA program research topic. Does this mean that the rest of the class has been influenced by this group? …On the other hand, we did not force them to come up with any of the topics. We guided them but the choice was theirs.

On the other hand, one participant remarked that they were at the end of their program, which provided a certain amount of safety, independence, and objectivity in offering recommendations for curricular improvements, saying

I mean, it is the last semester of our studies so we're not that worried because we won't we won't have consequences. If we had other semesters I think we would be more worried, but since (this is) the last semester I we won't you know, deal with them anymore (S4, I/1).

4.4.4 Lack of self-efficacy in making recommendations

Two of the participants expressed self-doubt about their ability to make recommendations to their professors about teaching and learning because, as one student stated, “we are not qualified… and they are people with doctorate degrees and they have thought of these courses far more than us”. This student added that one of the reasons why one did not feel comfortable sharing their findings to faculty for curricular improvements was that it felt they were “putting up a fight against the professors” (S2, I/2).

The other student reported that one felt that the entire cohort did not have the required experience to make recommendations because “you need to have competence to be able to recommend ideas, recommend things about the curriculum” (S4, I/2). To disguise the lack of competence, together with one's group members they resorted to the participants' input because this approach “made it easier” (S4, I/2).

4.4.5 Perceived impact and belief in change

Despite uncertainties regarding their qualifications to suggest changes in the curriculum and concerns about potential repercussions, participants expressed a strong belief that their recommendations would be given serious consideration and changes would eventually occur in the curriculum. This belief was supported by active faculty involvement during the co-construction, but also by early indications that changes were underway. As pointed out by one of the participants who was in contact with MA students from the subsequent cohort, their recommendations had been taken into account. In one's words, “I've noticed in a way that the professors actually took notes from what, at least what our interviewees mentioned in their interviews. So, I do believe they started to quite modify and change the program” (S1, I/2). Another participant (S3, I/2) conveyed assurance that their suggestions were impactful, noting that some faculty “actually cared, you know, to see some changes in the department” and also were sincerely invested “to put this idea forward so that the department gets improved”. On the same note, S4, I/2 pointed out that by witnessing the genuine enthusiasm of faculty members and observable signs of progress “I could see the interest of professors to to actually improve the improve the entire department so I think that now it has changed a bit”. Participants conveyed a shared conviction that their contribution would lead toward meaningful changes in the curriculum, shaping hence the learning experiences of future cohorts in the department, “even though it's not directly benefiting us” (S4, I/1).

5 Data analysis and recommendations

The findings show how significant student empowerment and ownership can be to the process of teaching and learning. Student participation in the project appears to be a transformative process in which students shift from passive beneficiaries into active contributors in the curriculum improvement (Ngussa and Makewa, 2014), thus becoming “agents of change” (Bergmark and Westman, 2016, p. 2). Substantial engagement of students in shaping their educational experiences and decision-making processes contributes to the enhancement of the quality of education (Ngussa and Makewa, 2014). Being empowered through the given “voice and choice” (Brooman et al., 2015), students are provided with the opportunity to express their opinions and the power to make changes in the educational setting. Their impact on the decision-making processes results in increased ownership of the learning process and greater motivation to contribute to the academic setting.

Student voice was always a driving force in this project, and the ways in which students who participated in this project found and expressed their voices permeated all of the interviews. In the given context, students had limited to no experience in assuming responsibilities as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula (Bovill et al., 2011), leading their experience to be marked by a high degree of uncertainty. One of their major concerns was the shift in power dynamics, which disrupted students' comfort due to “the hidden power of teachers embedded in institutional structures and cultures” (Ahmadi, 2021, p. 9). Students hesitated to fully participate in the initiative: their distrust in the system, which was also influenced by rumors about perceived retaliation by a few antagonistic faculty members, which would “threaten their performance” (Carey, 2013, p. 255), did not allow them to benefit fully from collaborative initiative to co-design curricula and improve teaching and learning. While participation in the project supported and enhanced their voices, the shift in power dynamics suppressed their voices to the point where they did not want to present the findings to the faculty, opting to convey them through written, but anonymous submissions. This highlights the complexities involved in introducing an innovative approach in an educational landscape deeply rooted in traditional pedagogies. What started as a collaborative effort to improve teaching and learning in the Department, soon altered its course of action as students could not withstand the pressure of external factors, such as fear of retaliation, which undermined their collective confidence. Instructors' commitment to equitable treatment, was not perceived to mirror the institutional culture: when trust in the institutions is undermined, it is not uncommon for certain individuals, as it was the case in this study, to sway their peers from the collective decision, highlighting the power of peers in influencing group dynamics.

The findings show that for faculty-student partnerships to be effective it is crucial to establish a foundation of trust: at an institutional level, mechanisms to safeguard students from any abuse of power should be in place, and/or the existing policies and protocols should be adhered to. At the departmental level, faculty members should be actively recruited to attend training and workshops on student learning and teaching. In addition, departmental meetings should serve as a forum for staff to express their views, experiences, opportunities, and challenges related to co-designing. Small-scale pilot projects should be encouraged, and support should be provided to staff willing to try out the approach in one of their courses. As a result, they can be the best advocates that co-construction is achievable and impactful, and in the long run, they can serve as mentors to others who embrace co-construction. Moreover, conducting a study that includes faculty members' views and experiences on the impact the co-designing of the curriculum has on teaching practice could deepen the understanding of student contribution in changing institutional practices and/or policies.

At the classroom level, faculty members should create classroom climates that encourage inclusive and open communication. This can include transparent discussions over how students' input will influence decisions and showcase examples of voice and choice that led toward successful outcomes. This will reassure students that collaboration initiatives are genuine. Students need to believe that they have the power to make changes in teaching and learning without fear of retribution (Bolkan and Goodboy, 2013). When possible, inviting students from previous cohorts to share their experiences could shed light on the co-designing process and its outcome, reassuring peers that change is possible. Moreover, continuous encouragement to share ideas and acknowledgment, even if they are not immediately implementable, can enhance students' confidence and inspire participation, which over time could foster trust in the institution. In addition, establishing support mechanisms such as peer mentoring networks, could eliminate discouraging narratives and strengthen collective efforts.

The findings also show that with an encouraging environment from a few faculty members, students embrace the opportunity to partner with faculty and recognize the power their contribution can have in improving teaching and learning. Rather than withdrawing from initiatives under the excuse that there might be negative consequences, students can take a more proactive stance in addressing cases of power abuse through formal channels, share their concerns with peers and faculty, and provide concrete examples of improvement. As (Carey 2013, p. 258) points out, there is a need to “shift from a complaints culture … and encourage students to offer solutions to problems.” Moreover, follow-up studies on the impact of curriculum co-creation should be conducted: this will enable researchers to identify similarities and differences in students' experiences across different cohorts and evaluate the effectiveness of curriculum co-creation reform.

As suggested by the findings, students have been conditioned to their submissive roles within entrenched structures. The invitation to assume an equal role in the partnership was an unconventional practice, hence the expressed uncertainties and self-doubt. The findings show that, not surprisingly, students hesitated to question the authority of faculty members and the established practices. Students' perceived lack of self-efficacy is deeply embedded in their belief that they lack the competency and credibility to impact decision-making at the institutional level. Furthermore, students have had limited or no opportunities to engage in non-hierarchical discussions with faculty members. They were rarely encouraged to voice their concerns, and they had no experience to show that their input was valued, and improvements had been made.

However, once the opportunity was created for them and adequate guidance and support were provided, students began to exhibit a growing sense of empowerment and transformation. In line with other studies on student-teacher partnership (Dollinger and Lodge, 2020; Marquis et al., 2016), this emerging sense of agency was supported by initial curriculum changes drawing on student input and faculty readiness to embrace feedback The findings reveal that transformation is an evolving process, one that cannot solely rely on immediate curriculum modifications, which are often bound by accreditation regulations and procedures, but rather on the steady growth of student empowerment (Bergmark and Westman, 2016). In other words, students could take ownership of their learning as proactive participants once they recognize their capacity to influence decisions in educational processes, including curriculum change. This shift marks a departure from the traditional passive roles assigned to students. In their roles as co-creators, students can foster a meaningful and gradual transformation of the curriculum, shaping, therefore, not only their educational experiences but also paving the way for lasting changes toward a more inclusive and responsive curriculum reform (Bergmark and Westman, 2016).

To create a culture where students feel empowered to engage in dialogue with more experienced faculty members, more opportunities for collaboration should be created such that this becomes the norm rather than the exception. To foster a sense of partnership, faculty can involve students in research projects and/or invite them to join committees concerning teaching and learning. In addition, faculty members willing to embrace the co-design approach should start with more manageable initiatives such as inviting students to set classroom norms and deadlines, offering them options to choose assignments and/or assessment tools, collecting data anonymously from students, and, when possible, acting upon their suggestions. The gradual exposure would not only create an opportunity for students to engage in collaboration and decision-making processes, but it would be less threatening compared to asking them to suggest changes in the curriculum. Progressively, it could help them gain confidence and establish trust in the institution.

5.1 Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, although there were four groups of students in the class, with each group comprised of three students, only five students, representing two groups, volunteered to be interviewed for this study. Of the two groups represented by the five students, one became so dysfunctional that one member of the group had to be separated from the other two so the project could move forward. The other group represented by the interviewees was particularly cohesive and worked well together. These two groups represented two extremes and may have impacted the findings and interpretation.

The small sample size of five participants could be considered another limitation of this study. However, considering the total number of MA students (twelve students) that were involved in the class project, the number of five study participants can be regarded as representative of the whole group as it reflects a diversity of perspectives and insights. Consequently, the findings of this study are specific to this program and may not be generalized beyond this context.

5.2 Impact statement

The project is of interest to several different stakeholders. The first is to the administration of the university, which will benefit by receiving new ideas from students, who represent a more diverse group than themselves. These new ideas can support the university's transformation to a more modern university that can attract more international students and bring prestige to the country as a whole as well as better prepare students to compete in a global economy. The second group of stakeholders is the faculty, who will benefit from an infusion of new ideas that will enhance and energize their teaching. The third group is the future students who will benefit from a better quality program of study that better prepares them for their future careers.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Scientific Research Ethics Commission University of Prishtina. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmadi, R. (2021). Student voice, culture, and teacher power in curriculum co-design within higher education: an action-based research study. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 28, 177–189. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2021.1923502

Bell, T., Vat, L. E., McGavin, C., Keller, M., Getchell, L., Rychtera, A., et al. (2019). Co-building a patient-oriented research curriculum in Canada. Res. Involv. Engage 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40900-019-0141-7

Bergmark, U., and Westman, S. (2016). Co-creating curriculum in higher education: Promoting democratic values and a multidimensional view on learning. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 21, 28–40. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2015.1120734

Blair, E., and Valdez Noel, K. (2014). Improving higher education practice through student evaluation systems: is the student voice being heard? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 879–894. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.875984

Bolkan, S., and Goodboy, A. K. (2013). No complain, no gain: Students organizational, relational, and personal reasons for withholding rhetorical dissent from their college instructors. Commun. Educ. 62, 278–300. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2013.788198

Bovill, C., Cook Sather, A., and Felten, P. (2011). Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: Implications for academic developers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 16, 133–145. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2011.568690

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Millard, L., and Moore-Cherry, N. (2016). Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: Overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. High. Educ. 71, 195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4

Bovill, C., Morss, K., and Bulley, C. (2009). Should students participate in curriculum design? Discussion arising from a first year curriculum design project and a literature review. Pedagog. Res. Max. Edu. 3, 17–25.

Bron, J., and Veugelers, W. (2014). Why we need to involve our students in curriculum design: Five arguments for student voice. Curriculum and teaching dialogue, 16, 125.

Brooman, S., Darwent, S., and Pimor, A. (2015). The student voice in higher education curriculum design: is there value in listening? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 52, 663–674. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2014.910128

Carey, P. (2013). Student as co-producer in a marketised higher education system: a case study of students' experience of participation in curriculum design. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 50, 250–260. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2013.796714

Chilvers, L., Fox, A., and Bennett, S. (2021). A student–staff partnership approach to course enhancement: Principles for enabling dialogue through repurposing subject-specific materials and metaphors. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 58, 14–24. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2019.1675530

Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Student voice across contexts: Fostering student agency in today's schools. Theory Pract. 59, 182–191. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2019.1705091

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design - qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th Edn.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design – Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th Edn.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2017). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Dollinger, M., and Lodge, J. (2020). Understanding value in the student experience through student–staff partnerships. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 39, 940–952. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1695751

Dollinger, M., Lodge, J., and Coates, H. (2018). Co-creation in higher education: Towards a conceptual model. J. Market. High. Educ. 28, 210–231. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2018.1466756

Eckhaus, E., and Davidovitch, N. (2023). What do academic faculty members think of performance measures of academic teaching? a case study from a 10-year perspective. SAGE Open 13:21582440231181569. doi: 10.1177/21582440231181569

Jagersma, J. (2010). Empowering Students as Active Participants in Curriculum Design and Implementation. Online Submission. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED514196 (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Marquis, E., Puri, V., Wan, S., Ahmad, A., Goff, L., Knorr, K., et al. (2016). Navigating the threshold of student–staff partnerships: A case study from an Ontario teaching and learning institute. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 21, 4–15. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2015.1113538

Martens, S. E., Wolfhagen, I. H., Whittingham, J. R., and Dolmans, D. H. M. (2020). Mind the gap: teachers' conceptions of student-staff partnership and its potential to enhance educational quality. Medical teacher, 42, 529–535. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1708874

Matthews, K. E., and Dollinger, M. (2023). Student voice in higher education: the importance of distinguishing student representation and student partnership. High. Educ. 85, 555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00851-7

Naylor, R., Dollinger, M., Mahat, M., and Khawaja, M. (2021). Students as customers versus as active agents: Conceptualising the student role in governance and quality assurance. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 40, 1026–1039. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1792850

Ngussa, B. M., and Makewa, L. N. (2014). Student voice in curriculum change: A theoretical reasoning. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progres. Educ. Dev. 3, 23–37. doi: 10.6007/IJARPED/v3-i3/949

Nixon, S., and Williams, L. (2014). Increasing student engagement through curriculum redesign: deconstructing the “Apprentice” style of delivery. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 51, 26–33. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2013.845535

O'Neill, G. (2015). Curriculum design in higher education: Theory to practice, Dublin: UCD Teaching & Learning. ISBN 9781905254989 Available online at: http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/UCDTLP0068.pdf (Accessed January 10, 2024).

Price, I., and Regehr, G. (2022). Barriers or costs? Understanding faculty resistance to instructional changes associated with curricular reform. Canad. Med. Educ. J. 13:113. doi: 10.36834/cmej.74041

Tuhkala, A., Ekonoja, A., and Hämäläinen, R. (2021). Tensions of student voice in higher education: Involving students in degree programme curricula design. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 58, 451–461. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2020.1763189

Keywords: student-faculty partnership, curriculum co-construction, empowerment, ownership, student agency

Citation: Mustafa B, Gruda Z and Sarris J (2025) From spectators to decision-makers: redefining student roles as co-designers of curriculum. Front. Educ. 10:1645916. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1645916

Received: 12 June 2025; Accepted: 25 August 2025;

Published: 23 September 2025.

Edited by:

Rolando Salazar Hernandez, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, MexicoReviewed by:

Sheila S. Jaswal, Amherst College, United StatesLaura MacDonald, Hendrix College, United States

Copyright © 2025 Mustafa, Gruda and Sarris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zinaide Gruda, emluYWlkZS5ncnVkYUB1bmktcHIuZWR1

Blerta Mustafa

Blerta Mustafa Zinaide Gruda

Zinaide Gruda Julia Sarris

Julia Sarris