Abstract

Introduction:

Young people are experiencing an escalating global mental health crisis, intensified by the effects of COVID-19, cultural disconnection, and the limited fit of conventional clinical models with diverse populations. While biomedical and psychological models remain essential, they often underplay the symbolic, sensory, and relational dimensions of emotional life. This review explores how young people interpret and regulate their mental health through expressive, symbolic, and sonic practices. It proposes that the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework can complement existing approaches by offering a more integrated understanding of how cultural participation supports wellbeing.

Methods:

A narrative review informed by the CAP framework, which extends the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model, was conducted to evaluate how participatory cultural practices function as affective technologies. Literature published between 2010 and 2025 was systematically identified from five databases and screened using PRISMA-informed protocols. Data were analyzed thematically with CAP and CAI constructs. Two case studies–Whānau Ora (New Zealand) and Giving Emotions Meaning through Arts and Health (GEMAH) (Pakistan and Australia)–were selected to illustrate how CAP explains mechanisms through which cultural participation supports emotional wellbeing.

Results:

Participatory arts such as music, storytelling, and ritual were found to serve as cultural technologies that foster emotional regulation, identity coherence, and social connection. Sonic and symbolic practices created co-regulatory fields of belonging, effects often absent in conventional clinical models. CAP aligned with these findings by offering a theoretical lens to explain why such practices work, reframing them as structured culture as affective technologies rather than incidental engagement.

Discussion:

Culture-as-Practice provides more than an alternative to biomedical models. It offers an explanatory framework for why participatory, culturally grounded practices support youth mental health and wellbeing. By positioning emotional regulation as relationally and symbolically scaffolded, CAP highlights opportunities for integrating creative and communal practices into trauma-informed, culturally resonant interventions across schools, communities, and clinical settings.

1 Introduction

The mental health of young people is undergoing a profound global crisis, with significant increases in anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation reported across diverse cultural and socioeconomic settings (Racine et al., 2021; McGorry et al., 2024; World Economic Forum (WEF)., 2024; Young Lives., 2022). The global youth mental health crisis has intensified in the wake of COVID-19, with widespread evidence of escalating depression, anxiety, and social disruption among adolescents (Frentzen et al., 2025). Research shows that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges by disrupting the developmental structures such as schools, peer networks, and family routines that typically scaffold emotional growth and regulation (Aagaard, 2021; Huebner and Schulkin, 2022). In its aftermath, young people now face intensifying pressures, including digitally saturated environments, cultural disconnection, and persistent stigma surrounding mental health (Marciano et al., 2022). These global challenges highlight the necessity of exploring interventions that address not only individual pathology but also the cultural, social, and emotional contexts of youth mental health–an approach exemplified by participatory arts practices.

Medical education literature also highlights the persistent neglect of arts and humanities in preparing clinicians to respond empathetically to such challenges (Bitonte and De Santo, 2014). These converging stressors have fragmented emotional life in ways that conventional mental health responses struggle to address, particularly among culturally diverse and marginalized youth. As traditional models struggled to respond effectively, their limitations became increasingly visible, particularly their failure to resonate with culturally diverse or systemically excluded youth (Fomina et al., 2023). It is within this fractured terrain that culture reemerges not as a secondary variable, but as a core determinant of how emotional life is structured, experienced, and addressed (Bennett et al., 2023).

Youth mental health, as a dependent variable, encompasses a wide range of indicators: emotional regulation, self-concept clarity, social connection, and the ability to navigate life stressors. Mental health systems around the world face mounting challenges in delivering accessible, culturally appropriate services (Kirmayer and Jarvis, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2025; McGorry et al., 2025). Many young people report difficulty in identifying, articulating, or seeking help for emotional concerns, particularly when dominant models demand linguistic fluency, diagnostic agreement, or therapeutic engagement on clinical terms (Nguyen et al., 2025; Kirmayer and Jarvis, 2019). These systemic mismatches contribute to underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, and disengagement–especially for youth whose emotional lives unfold in collective, aesthetic, or non-verbal registers (World Economic Forum (WEF)., 2024). As a result, a more inclusive, adaptive, and culturally literate approach to care is urgently required.

The independent variable at the heart of this review–cultural framings–refers to the symbolic systems, practices, and narrative structures that mediate how emotion is felt, interpreted, and regulated. The Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model posits that these framings are not passive reflections of heritage, but dynamic, participatory environments that scaffold affective life. Emotional coherence, within this model, arises not simply from internal processing but from interaction with culturally resonant “scaffolds” songs, rituals, images, and movements that enable individuals to metabolize feeling and construct meaning. Cultural framings thus shape not only emotional expression but also the neurobiological regulation of stress and resilience, positioning affect as both socially produced and socially remedied (Weinrabe and Murphy, forthcoming). Cultural framings thus shape not only emotional expression but also the neurobiological regulation of stress and resilience (Koelsch, 2009, 2014; Porges, 2011; Van Lith and Ettenberger, 2023). Whether through ritual chanting, visual storytelling, improvisational performance, or traditional dance, participatory arts operate as culturally adaptive technologies of care (Durkheim, 1955; Malchiodi, 2012a, 2012b, 2015; Stuckey and Nobel, 2010; de Witte et al., 2021; Hommel and Kaimal, 2024). Recent evidence highlights the importance of arts-based neurocultural methods in trauma recovery for young people, demonstrating the potential of embodied interventions in mental health (Barnett and Vasiu, 2024). Artistic engagement bypasses cognitive and linguistic constraints, enabling young people to access, explore, and restructure emotional experience in ways that clinical talk therapy may not accommodate (Kaimal et al., 2016; Czamanski-Cohen and Weihs, 2023).

The interaction between cultural framings and youth mental health outcomes is foundational to this review. Cultural practices do not merely shape emotional norms; they co-create the scaffolding through which regulation, resilience, and recovery become possible (Porges, 2011; Koelsch, 2014; Van Lith and Ettenberger, 2023). Rhythmic, sonic, and non-verbal forms such as communal singing, silence, or laughter function not only as expressions of mood but also as generative environments that foster synchrony and shared emotional attunement (Weinrabe and Asoulin, 2026). The erosion of these practices during pandemic lockdowns, combined with the isolating effects of digital life, has left many young people disconnected from vital modes of embodied interaction. Although a growing body of evidence demonstrates the therapeutic potential of such forms (Fancourt et al., 2019), few studies directly center youth perspectives in articulating how cultural framings–especially symbolic ones–shape their experiences of mental distress and recovery (Shukla et al., 2022; Fancourt and Finn, 2019). Longitudinal evidence reinforces this claim: Zhang et al. (2024) show that symbolic participation significantly predicts improved youth mental health outcomes over time. This gap in youth-centered research highlights the urgent need for approaches that critically engage with how young people interpret and navigate their mental health experiences through cultural participation.

This survey of the literature aims to fill that gap by investigating how young people interpret and navigate their emotional lives through culturally embedded practices–particularly those that are participatory, symbolic, and sonic in nature. Grounded in the theoretical insights of the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model, the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework offers a methodology for understanding emotion as relationally constructed and rhythmically mediated (Weinrabe and Murphy, forthcoming; Pavarini, 2021). Creative practices such as music, movement, and storytelling are understood here as affective technologies, tools through which emotional coherence can be scaffolded and restored. This review has two overarching aims: first, to articulate the theoretical foundations of CAP and its lineage from CAI, and second, to evaluate its implementation and potential as a scalable, context-sensitive model of youth mental health care. These aims are elaborated in Section “1.2 Objectives and hypotheses” as three specific objectives

1.1 Rationale and conceptual framing

Youth mental health has undergone significant challenges globally, with increasing rates of anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation observed across diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts (Racine et al., 2021; Knight et al., 2025). Conventional clinical models, which often rely on diagnostic categories and verbal cognitive processing, have been criticized for failing to resonate with many young people, particularly those from culturally diverse or marginalized backgrounds (Watters, 2010; Kirmayer and Gómez-Carrillo, 2019). Increasingly, evidence points to the importance of participatory, culturally embedded practices such as music, storytelling, ritual, and visual art in shaping emotional regulation, identity coherence, and psychosocial resilience (Fancourt and Finn, 2019; Koelsch, 2010). Clarifying who is encompassed by the term “youth” is essential for interpreting these findings, yet the literature reveals inconsistencies in how this group is defined.

Weinrabe and Hickie (2023) suggest that the term “youth” broadly encompasses individuals in the developmental stage spanning from early adolescence (around 12 years old) to young adulthood (up to approximately 24 years old). They argue that this wide age range reflects the ongoing maturation of brain regions involved in emotional regulation and decision-making, which continues into the mid-20s. However, they note that the literature often misconstrues or inconsistently applies age boundaries, sometimes equating “youth” strictly with teenagers or early adolescents. This inconsistency can lead to misinterpretation of research studies, as it overlooks the significant neurodevelopmental changes that occur during late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Such definitional ambiguities highlight the need for theoretical frameworks that move beyond narrow biological or age-based classifications, prompting a closer examination of how health and emotional well-being are conceptualized within different philosophical traditions.

Murphy (2015, 2025): Murphy et al. (2020) stresses that the concept of health is not just about physiological functioning but involves normative judgments based on context. And although physiological functioning is vital to mental health, it is in turn adapted to the mix of social, material and cultural environments that enable humans to flourish in mentally healthy ways (Murphy, 2023). The Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework aligns with this orientation, acknowledging that cultural and relational scaffolding play a central role in emotional health, but it extends beyond previous philosophical critiques by framing participatory cultural practices in action as affective technologies that actively co-regulate emotional life.

The decision to begin this review in 2010 reflects a pivotal shift in youth mental health research. From 2010 onward, there was a marked increase in studies adopting participatory, arts-based, and culturally grounded approaches, coinciding with broader recognition of the social determinants of mental health and the influence of cultural and relational “scaffolding” on emotional well-being (Seah and Coifman, 2024; Basu and Banerjee, 2020). Before this period, most literature was dominated by individualized, pathology-focused frameworks with limited relevance to the CAP framework (Watters, 2010).

This paper also responds directly to the journal’s special edition focus on post-COVID mental health. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the cultural, social, and relational infrastructures that support youth mental health, producing what some scholars have termed a “crisis of affective scaffolding” (Zhang-James et al., 2025). Emerging research demonstrates that participatory arts, collective rituals, and other culturally embedded practices were central to rebuilding resilience and restoring emotional coherence during and after the pandemic (Stevenson and Alzyood, 2025; People’s Palace Projects., 2022). By applying the CAP framework to this evidence base, the review aims to advance a neurocultural understanding of youth mental health that highlights participatory cultural practices not as peripheral, but as central regulatory technologies in both pre- and post-pandemic contexts.

1.2 Objectives and hypotheses

The primary objective of this paper is to critically examine how young people frame, interpret, and regulate their mental health experiences through culturally embedded, participatory practices. Rather than treating these practices as ancillary or recreational, we conceptualize these as affective technologies or structured cultural forms that actively shape and enable emotional life, identity, coherence, and resilience. Grounded in the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework, our analysis positions cultural engagement not as a peripheral adjunct to clinical care, but as a central infrastructure for youth mental health. Specifically, our research aims to clarify the theoretical foundations of CAP by extending the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model, offering a neurocultural and relational account of how participatory practices such as music-making, storytelling, ritual, and visual art scaffold a person’s emotional regulation.

The secondary objective is to evaluate how participatory practices function as embodied regulatory environments, bypassing cognitive-linguistic barriers and enabling emotional recalibration in ways often inaccessible to conventional talk-based or diagnostic approaches. Particular attention is given to the sonic and symbolic modalities that facilitate co-regulation, social attunement, and nervous system synchrony. As Ross (2023) argues, affect and symbol are inseparable in the making of mental health, a claim that underpins our framing of participatory arts as affective technologies. Thirdly, we assess CAP’s potential as a context-sensitive and scalable model of youth mental health care, especially in settings where formal clinical services are inaccessible, culturally incongruent, or under-resourced (Ranjbar et al., 2020). This includes identifying how CAP principles can inform trauma-informed, community-based interventions and complement existing mental health infrastructures.

The results from this research suggest two core hypotheses: First, participatory cultural practices, particularly those involving rhythm, repetition, symbolic patterning, and collective meaning-making, seem to act as affective technologies that regulate emotional states by engaging embodied, non-verbal, and relational mechanisms, as demonstrated in neuroscience research on music-induced dopamine release (Salimpoor et al., 2011) and on neural plasticity through music training (Thompson and Schlaug, 2015). Such practices exemplify what Slaby (2016) describes as “situated affectivity,” where external cultural forms and environments scaffold and modulate emotional states, making them more resonant and accessible for youth than conventional interventions requiring verbal processing or diagnostic agreement.

Second, emotional distress among youth frequently reflects ruptures in cultural, aesthetic, and relational infrastructures rather than solely internal psychopathology, suggesting that mental health challenges should be understood as ecological consequences of disrupted cultural participation, with recovery also dependent on restoring symbolic and communal support.

Collectively, these objectives and hypotheses contribute to a growing paradigm shift in youth mental health care–one that recognizes culture not as an optional enhancement to therapy, but as the foundation through which emotional life is regulated, restored, and shared.

1.3 Related works

The global youth mental health crisis has led to a notable rise in research exploring participatory arts-based interventions as culturally responsive alternatives to traditional clinical models. These interventions–including music, storytelling, visual arts, and ritual–are increasingly recognized for their potential to foster emotional regulation, identity coherence, and psychosocial resilience among youth, consistent with research showing that cultural frameworks of selfhood shape cognition, emotion, and motivation (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). However, their effectiveness varies according to sociodemographic factors such as gender, socioeconomic status, and cultural background, prompting several scholars to call for periodic, context-sensitive reviews (Golden et al., 2024; Williams R. et al., 2023). In this vein, Hugh-Jones and Munford (2025) provide an international review of youth participatory arts in post-pandemic contexts, demonstrating how creative practices contribute to recovery and resilience in ways that complement biomedical and psychosocial approaches. More recently, Williams E. et al. (2023) provide a mixed-methods meta-review demonstrating how youth participatory arts facilitate collective healing, reinforcing the evidence base for their role as culturally responsive alternatives to traditional models.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as India, participatory arts have been shown to support youth in addressing depression and anxiety, providing culturally relevant and accessible pathways for emotional expression (Bux and Van Schalkwyk, 2022). In Bangladesh, social and academic pressures, family dynamics, and financial instability intersect with youth mental health, underscoring the need for contextually adapted interventions (Khan et al., 2025). Similarly, Tan et al. (2020) demonstrate the application of art therapy in humanitarian crises, highlighting its capacity to provide culturally responsive, non-verbal pathways for emotional expression and recovery in settings of acute social disruption. Sub-Saharan African contexts have also seen the use of participatory arts to reduce stigma and foster community-based mental health engagement, reinforcing the potential of culturally embedded approaches (Mendelsohn et al., 2022).

By contrast, studies in high-income countries like the United Kingdom and the United States demonstrate the promise of participatory arts as complementary to established mental health services. In the United Kingdom, arts-based programs have shown improvements in youth well- being, though gaps remain in measuring outcomes across different population groups (Williams R. et al., 2023). In the United States, Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) is gaining ground as a model that centers the lived experiences of youth while empowering them to co-create mental health solutions (Anyon et al., 2018). A comparative view reveals both convergence and divergence. While participatory arts are effective in both Global South and North contexts, implementation methods differ significantly due to disparities in infrastructure, resources, and cultural dynamics. For example, while digital platforms and formal evaluations are common in the North, community-driven, oral, and embodied approaches are more prevalent in the South. Gender norms, socio-economic conditions, and historical-cultural legacies influence how and whether youth engage with artistic practices across contexts (Pavarini, 2021; Fancourt and Finn, 2019).

The reviewed literature presents a shared global recognition of the potential of cultural framings in youth mental health but also highlights the need for tailored intersectional strategies. i.e., programs must consider sociodemographic and cultural nuances to ensure equitable access and meaningful impact. This research therefore aims to fill critical gaps by investigating not only the effectiveness of participatory arts-based approaches but also their differential reception and resonance across diverse global contexts.

Over the past decade, there has been a growing recognition of the role that participatory arts and cultural practices play in supporting youth mental health. These approaches are increasingly viewed not merely as supplementary to clinical interventions but as integral to fostering emotional regulation, resilience, and social connection among young people. A comprehensive global review by Golden et al. (2024) highlights the potential of arts-based strategies to address youth mental health challenges. The study highlights the accessibility and cultural adaptability of such interventions, emphasizing their capacity to engage youth in meaningful ways that resonate with their lived experiences. Similarly, Williams R. et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review revealing that participatory arts-based programs significantly contribute to various aspects of children’s and young people’s mental health and well-being, including reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms.

In the Australian context, the “Creating Well-being” report by Creative Australia. (2023) provides insights into public engagement with arts and health initiatives. The findings indicate a strong public interest in integrating arts into health strategies, with many viewing arts engagement as beneficial to mental well-being. This aligns with the principles of the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework, which posits that cultural practices are foundational to emotional life.

Further supporting this perspective, Pavarini (2021) discuss the ethical considerations in participatory arts methods for young people with adverse childhood experiences. Their work emphasizes the importance of co-creating interventions with youth, ensuring that their voices and cultural contexts are central to the development of mental health strategies. Moreover, the integration of digital platforms in arts-based interventions has shown promise. Kumar et al. (2025) explored the design and evaluation of “CUBE” an arts-based digital platform aimed at assisting trauma-impacted youth. The study found that such platforms could provide accessible avenues for youth to express and process their experiences creatively.

Collectively, these studies generate a paradigm shift toward embracing culturally grounded, participatory approaches in youth mental health. They highlight the efficacy of integrating arts and cultural practices into mental health interventions, resonating with the CAP framework’s emphasis on the co-construction of emotional well-being through cultural engagement.

2 Materials and methods

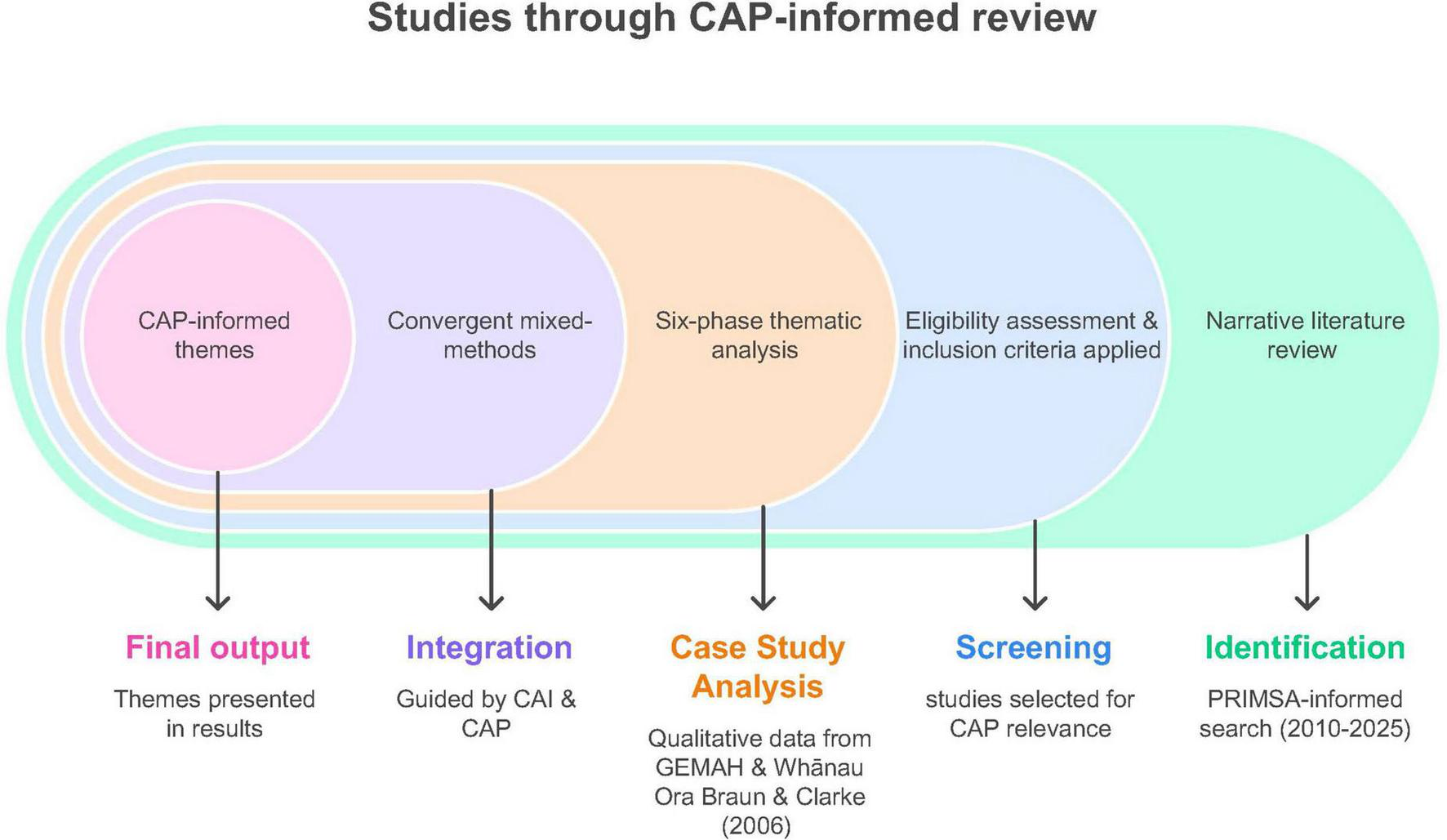

This study adopted a mixed-methods, narrative review design informed by the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework, which extends the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model. The central objective was to examine how young people interpret and regulate their mental health experiences through participatory, symbolic, and sonic practices. Two complementary stages of analysis were undertaken. The first was a narrative synthesis of peer-reviewed literature published between 2010 and 2025, conducted in line with PRISMA-informed guidelines to ensure transparency and replicability. The second was a qualitative analysis of two case studies–Whānau Ora in Aotearoa New Zealand and GEMAH in Pakistan and Australia–which provided depth and cultural specificity in illustrating how CAP principles are enacted in practice. Together, these approaches ensured both breadth and depth: the review established scope and patterns across the field, while the case studies provided insight into mechanisms and lived realities (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Design and analysis roadmap.

2.1 Participants/object of the study

The object of study in this project was not individual participants but defined sets of materials and programmes. In the narrative review (Group 1), the object of study was a body of peer-reviewed publications addressing youth mental health, participatory or arts-based practices, and cultural or symbolic approaches to wellbeing. From an initial pool of 650 records retrieved through database searches, 30 documents met the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. Studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on biomedical interventions, lacked sufficient methodological detail, or were unavailable in English.

In the qualitative strand (Group 2), the object of study consisted of two purposively selected programmes: Whānau Ora in Aotearoa New Zealand and GEMAH in Pakistan and Australia. These programmes were chosen because of their explicit alignment with Culture-as-Practice principles and the availability of both qualitative and quantitative data. Importantly, we did not conduct primary data collection; instead, we analyzed the data as presented by the programme teams, which included interviews, workshops, ethnographic observation, and reported quantitative measures. Youth involved in these programmes ranged from 12 to 25 years in Whānau Ora and from 18 to 25 years in GEMAH, an age span characterized by neuroplasticity, identity formation, and heightened sensitivity to socio-cultural influences.

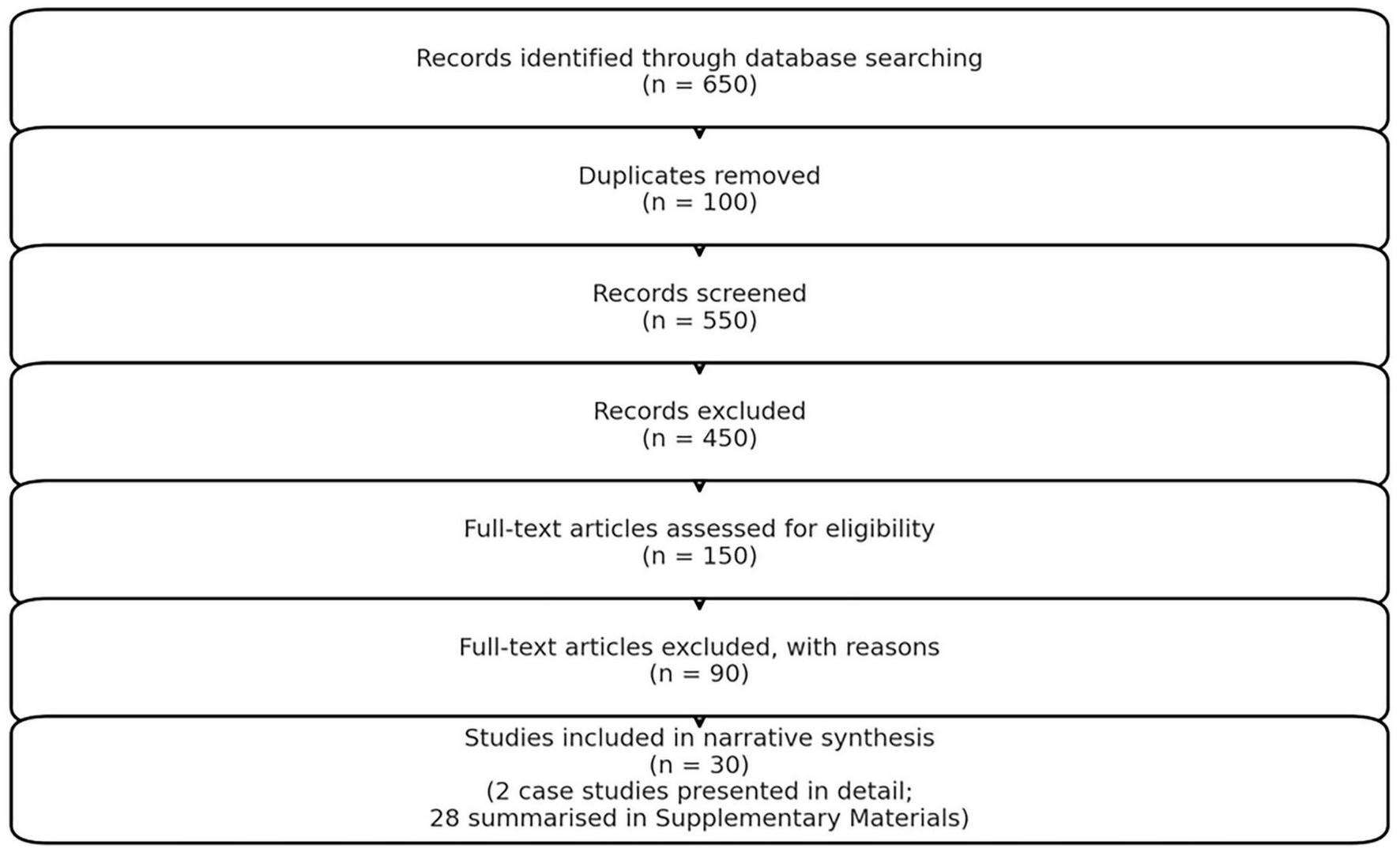

2.2 Instruments

The instruments used were tailored to the two strands of the study. For the narrative review, literature searches were conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Google Scholar, and JSTOR using Boolean combinations of terms relating to youth, mental health, culture, and participatory or arts practices. Screening and selection followed PRISMA-informed protocols to ensure replicability, with the process illustrated in Figure 2. This systematic approach enabled transparent reporting of inclusion and exclusion decisions and produced a final set of 30 studies. While two programmes are examined in detail in the main text, a summary of findings from the remaining 28 studies is provided in the Supplementary Material to maintain focus and coherence.

FIGURE 2

PRISMA flow diagram.

For the case studies, data collection involved semi-structured interviews, participatory arts-based workshops, and ethnographic observation. These methods enabled in-depth exploration of how cultural and symbolic practices support youth wellbeing. Analysis drew on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase reflexive thematic framework. Deductive coding was guided by constructs from the CAP and CAI models (such as “plumbing” and “scaffolding”), while inductive coding allowed themes to emerge directly from participants’ accounts. The analytic process was iterative and supported by reflexive journaling and memo writing to ensure rigor. Together, these instruments addressed the study’s objectives by combining the systematic scope of PRISMA with the interpretive depth of qualitative thematic analysis.

2.3 Procedure

The research unfolded in a series of steps. First, a systematic literature search was conducted across five databases for publications from 2010 to 2025. After removing duplicates and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 30 studies were retained for synthesis. In parallel, two case programmes–Whānau Ora and GEMAH–were purposively selected for detailed analysis. These programmes were chosen because they exemplify Culture-as-Practice principles in contrasting cultural and geopolitical contexts and provide both rich qualitative and quantitative data. Data collection in these programmes involved interviews, workshops, and observation in Pakistan, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand. The resulting material was subjected to both deductive and inductive thematic coding. Finally, findings from the review and case studies were integrated using a convergent mixed-methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018), allowing insights from both strands to be displayed in a joint analytic roadmap.

2.4 Data analysis

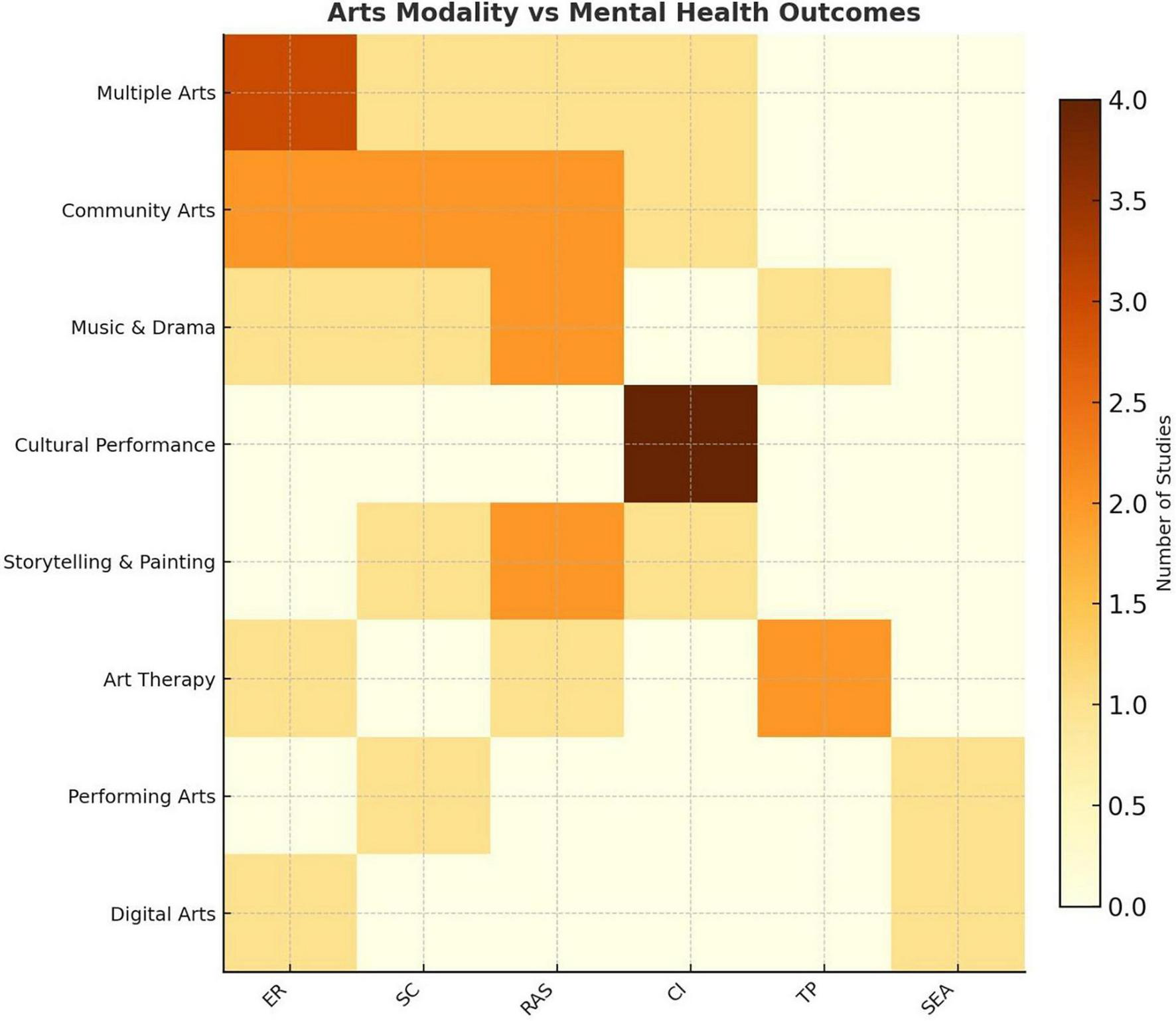

Data analysis was adapted to each strand. In the narrative review, studies were coded by arts modality (y-axis) and mental health outcome (x-axis), then summarized in a cross-tabulation matrix and visualized as heatmaps and network graphs (Figure 3). Modalities included multiple arts, community arts, music and drama, cultural performance, storytelling and painting, art therapy, performing arts, and digital arts. Outcomes included emotional regulation, social connection, reduced anxiety and stress, cultural identity, trauma processing, and self-esteem/agency. This visualization enabled the distribution of modalities across outcomes to be interpreted at a glance and highlighted patterns across the evidence base.

FIGURE 3

Arts modalities vs. mental health outcomes across 30 studies.

For the case studies, we interpreted the data presented by the programmes, which included their interviews, workshops, and ethnographic observations, as well as reported quantitative measures analyzed with STATA using paired t-tests to examine pre- and post-intervention changes in emotional expression, self-efficacy, social connectedness, and anxiety symptoms. The qualitative materials were analyzed thematically, guided by Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) trustworthiness criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability.

Integration followed a convergent mixed-methods design in which the narrative review provided deductive frameworks, while the case studies generated inductive, culturally grounded insights.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This project was conducted in line with recognized ethical standards for literature reviews and qualitative synthesis. As it analyzed previously published studies and secondary data, no new human subjects were recruited, and formal ethics approval was not required. Ethical responsibility therefore focused on ensuring transparency, accountability, and cultural respect in how evidence was interpreted and presented.

Records were managed systematically, with a clear audit trail of inclusion and exclusion decisions to minimize bias. Data from reviewed studies and case descriptions were reported accurately and with sensitivity to cultural and contextual meaning. Reflexivity was embedded throughout: the research team maintained positionality notes, documented analytic decisions, and discussed assumptions regularly to ensure interpretive accountability.

In keeping with best practice for review-based research (Committee on Publication Ethics (Cope)., 2017), the emphasis was on accurate synthesis, avoidance of misrepresentation, and acknowledgment of limitations. These measures ensured compliance with standards of integrity and transparency while distinguishing our methodological responsibilities from those of the original study teams.

3 Results

The findings presented in this section focus on two case studies: Whānau Ora (Aotearoa New Zealand) and GEMAH (Pakistan and Australia), selected as exemplars from a larger pool of 30 studies identified through the narrative review. These cases were chosen because they provide rich empirical evidence, explicitly align with CAP principles, and illustrate how participatory, culturally embedded practices can support youth mental health in contrasting cultural and geopolitical contexts.

The sections that follow are organized according to the mixed-methods design: Firstly, findings from the narrative review provide the theoretical grounding (Section “3.1 Theoretical outcomes: Culture-as-Interaction”). Table 1 provides an overview of the reviewed studies, grouped by thematic category aligned with the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework. Several studies contributed to more than one thematic category, reflecting the interconnected nature of embodied emotional coherence, collective symbolic scaffolding, and cultural ritual as affective scaffolding in youth mental health.

TABLE 1

| Thematic category | No. of articles reviewed | Key references |

| Embodied emotional coherence (plumbing) | 10 | Koelsch, 2010; Fancourt and Finn, 2019; Shukla et al., 2022; Block et al., 2022 |

| Collective symbolic scaffolding (scaffolding) | 15 | Williams R. et al., 2023; Golden et al., 2024; Restrepo et al., 2022; GEM Ltd and Karachi Biennale Trust., 2021 |

| Cultural ritual and identity as affective scaffolding (symbolic participation) | 12 | Levy, 2020; Te Puni Kōkiri., 2024; Mental Health, and Foundation, 2022; GEM Ltd and City of Sydney., 2023 |

Summary of reviewed articles.

Secondly, qualitative case studies (GEMAH and Whānau Ora) illustrate how these theoretical constructs operate in practice, with themes generated through Braun and Clarke’s (2006) reflexive thematic analysis (Sections “3.2 Findings: cultural scaffolding and emotional regulation”–“3.4 CAP’s empirical outcomes”).

3.1 Theoretical outcomes: Culture-as-Interaction

We synthesized the key theoretical outcomes relevant to the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) framework, streamlining the conceptual background to foreground findings that directly connect to the case study outcomes presented in Section “3.2 Findings: cultural scaffolding and emotional regulation.” These outcomes suggest that CAI reframes youth mental health not as an individualized, pathology-based construct but as an emergent property of relational, cultural, and symbolic interactions. Central to CAI is the premise that affective regulation arises through participation in shared cultural forms, where identity, belonging, and meaning are co-constructed.

The findings align with this theoretical position, revealing that emotional suffering can be interpreted as a rupture in relational and symbolic infrastructures, consistent with Kirmayer and Gómez-Carrillo’s (2019) notion of cultural affordances for coherence. Participants described regaining a sense of “being held” or “finding rhythm with others” during participatory practices, echoing CAI’s argument that psychosocial recovery is scaffolded through collective cultural engagement. Our analysis extends CAI by integrating empirical examples where relational scaffolding translated into tangible shifts in emotional regulation. Recent work in the foundations of psychology has stressed the role of scaffolding in enabling cognitive processing (Sterelny, 2010), but we draw attention to the way in which emotional life is also regulated and enabled by the environments in which we are embedded, and the importance of therapeutic regimes that work with the grain of those environments. Participants consistently highlighted the importance of cultural rituals, shared rhythm, and symbolic practices, findings that establish CAI not merely as a theoretical construct but as an observable process in youth mental health contexts. These outcomes provided the foundation for the CAP framework, which is elaborated in the following section.

3.2 Findings: cultural scaffolding and emotional regulation

The analysis revealed two key themes with four sub-themes that explain how cultural scaffolding supports emotional regulation. These findings demonstrate that emotional regulation emerged not as an isolated internal process but through embodied, aesthetic co-regulation and culturally grounded practices. A detailed summary of themes and sub-themes, including illustrative quotes, is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Theme 1: Collective Symbolic Scaffolding

Artistic and symbolic practices acted as affective technologies for emotional regulation and social connection. Participants described experiencing validation and recognition through non-verbal practices (Sub-theme 1.1: Non-verbal symbolic connection). A GEMAH Programme participant explained, “I just paint, but I feel seen when I do,” illustrating how non-verbal artistic engagement fostered belonging and recognition without requiring verbal disclosure. Shared rhythmic practices, such as group singing, movement, and drawing, helped regulate emotional states and created a sense of bodily grounding (Sub-theme 1.2: Ritualized rhythmic co-regulation). Participants described “releasing tension through rhythm” and “breathing differently when drawing or moving,” reflecting the embodied and co-regulated nature of emotional care.

Theme 2: Identity-Driven Cultural Grounds

Cultural identity functioned as a central scaffold for emotional and relational well-being. Whānau Ora participants emphasized that connection to ancestry and community provided emotional grounding (Sub-theme 2.1: Cultural identity as emotional scaffold). One navigator stated, “I draw on whakapapa and mana to guide whānau through their wellness plan.” Participants also reported subtle, pre-verbal shifts in emotional states expressed through symbolic and ritual practices (Sub-theme 2.2: Ineffability and symbolic enactment), describing “feeling something shift” or “being held in the rhythm of others.” These findings highlight the somatically felt and symbolically enacted dimensions of emotional regulation, which often elude linguistic articulation.

These two themes illustrate CAP’s core proposition: emotional regulation emerges through cultural, relational, and symbolic scaffolding. Artistic, ritual, and identity-based practices provided embodied pathways for emotional recalibration, positioning CAP as a functional and culturally resonant framework for youth mental health care.

3.3 Findings: CAP as a culturally embedded alternative

Cross-case analysis revealed that CAP operates as a culturally embedded alternative to dominant biomedical and therapeutic art models. The following themes and sub-themes highlight how participants and programme data contrasted CAP-based practices with more individualized models of care. These findings are based on patterns identified across GEMAH and Whānau Ora and demonstrate how emotional regulation and well-being were supported through collective, culturally grounded approaches. Thus, we found this as a third theme that arose, i.e., CAP offers a culturally embedded alternative: participants and programme outcomes highlighted that emotional regulation was socially distributed rather than individualized. The following sub-themes outline the specificity:

(i) Socially distributed emotional regulation

Participants consistently described care as arising through collective cultural practices rather than through individualized talk-based therapy. In both cases, group singing, storytelling, and shared ritual created co-regulated emotional states.

(ii) Resonance with cultural lifeworlds

CAP-aligned approaches were viewed as meaningful and accessible because they reflected participants’ cultural values, traditions, and aesthetic practices. A Whānau Ora navigator noted, “Whānau trust this because it’s our way, not someone else’s model.” This resonance increased participation and perceived relevance, contrasting sharply with clinical approaches described as “distant” or “not for us.”

These findings demonstrate that CAP does not function merely as a theoretical alternative but as a practical, culturally resonant model of care. Rather than centering on symptom reduction through individual talk-based methods, CAP facilitated emotional regulation by embedding support within culturally meaningful, relational, and symbolic practices. A summary of these cross-case contrasts with biomedical and therapeutic art models is provided in Table 2. Further detail on how CAP differs from conventional therapeutic art practices, including a comparative analysis, is provided in the Supplementary material.

TABLE 2

| Dimension | Traditional models | CAP framework (culture-as-practice) |

| Modality | Talk-based, cognitive, clinical | Embodied, symbolic, arts-based |

| Cultural grounding | Often absent or secondary | Central and constitutive |

| Mechanism of change | Cognitive insight, behavior modification | Emotional co-regulation via cultural and aesthetic practice |

| Delivery setting | Clinical institutions, digital platforms | Community, schools, grassroots, cultural spaces and digital platforms |

| Practitioner role | Mental health specialist, therapist | Cultural facilitator, artist-educator |

| COVID adaptability | Limited access and engagement, digital disparities exposed | High adaptability in- person and online through localized, relational practices |

| Epistemological stance | Individualized, pathologizing | Relational, collective, culturally resonant |

Comparison of traditional clinical models and the CAP framework for youth mental health care.

3.4 CAP’s empirical outcomes

3.4.1 Participatory arts as emotional scaffolding in New Zealand

The analysis of Whānau Ora data revealed two key themes with four sub-themes demonstrating how emotional well-being was supported through cultural, relational, and symbolic scaffolding. These findings show how CAP principles were enacted through ritual, ancestral connection, and participatory cultural practices. While Whānau Ora incorporates such cultural practices, it is formally recognized by The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [RANZCP]. (2024) as a whole-of-whānau, strengths-based commissioning framework. Beyond ritual and cultural grounding, it incorporates whānau-led decision-making, equity, and systemic accountability, in alignment with Te Tiriti o Waitangi (New Zealand’s founding document; Orange, 2015).

A summary of themes, sub-themes, and illustrative quotes is provided in Table 3. Full contextual details, including Whānau Ora’s policy background, neurocultural explanations, and supporting literature, are provided in the Supplementary Material.

TABLE 3

| Theme | Sub-theme | Description | Illustrative quote |

| Ritual and ancestral continuity as emotional scaffolding | Ancestral storytelling and whakapapa | Whakapapa (genealogical storytelling) provided intergenerational grounding, mitigating trauma-related fragmentation. | “I feel held by my ancestors.” |

| Ritual and ancestral continuity as emotional scaffolding | Ritual performance and collective co-regulation | Karakia (prayer), pōwhiri (welcoming ceremonies), mihi (formal greetings), and shared kai (meals) regulated emotional states and strengthened communal belonging. | “When we start with karakia, we are all together–my body settles.” |

| Participatory arts as emotional scaffolding | Creative wānanga as ritual practice | Kapa haka (performance), whakairo (carving), and raranga (weaving) were experienced as collective rituals shifting emotional states. | “When we perform haka, we are strong together–our feelings move with the rhythm.” |

| Participatory arts as emotional scaffolding | Cultural grounding through shared aesthetic practices | Shared artistic and aesthetic practices reinforced cultural identity and relational grounding. | “I feel part of something bigger, strong in who we are.” |

Themes and sub-themes: ritual and ancestral continuity in Whānau Ora.

3.4.2 Participatory arts as emotional scaffolding in Pakistan and Australia

Building on the qualitative findings from Whānau Ora, which illustrated how emotional regulation is scaffolded through ritual and cultural continuity, GEMAH provides complementary evidence demonstrating the same principles in a Global South and urban Australian context. While Whānau Ora highlighted the show of cultural scaffolding, GEMAH enables us to examine its outcomes quantitatively, offering measurable evidence of CAP’s effects on emotional regulation and social connection. This pivot to quantitative results provides an important cross-validation of CAP’s mechanisms across culturally distinct settings.

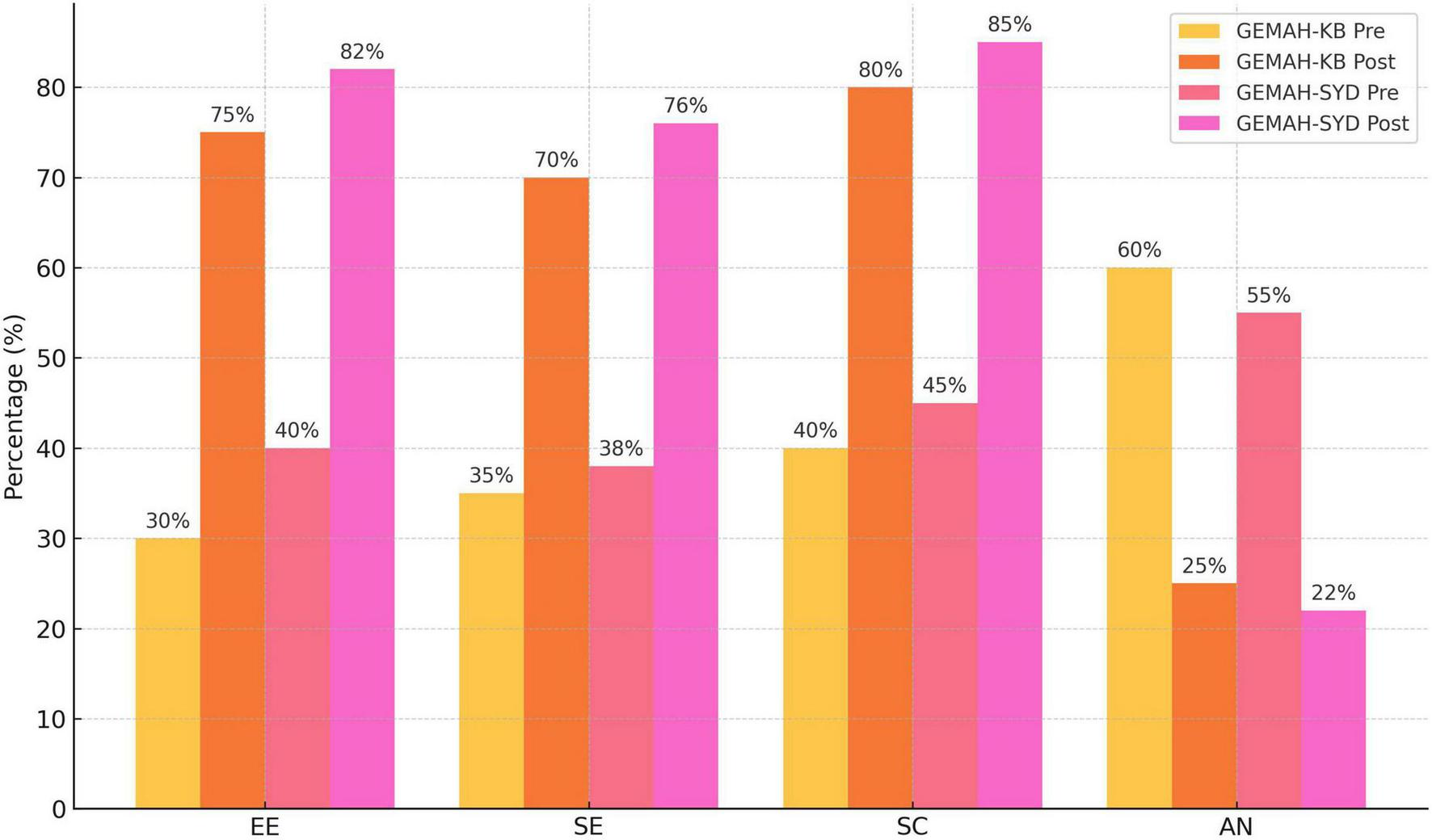

Quantitative analyses were conducted to evaluate psychosocial outcomes of GEMAH interventions in both Pakistan (GEMAH-KB, 2020–2024) and Australia (GEMAH-SYD, 2021–2023). Across both contexts, significant improvements were observed in emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and social connectedness, with reductions in anxiety symptoms.

For GEMAH-KB (Pakistan) in total, the bi-annual programme serviced N = 120 young adults aged 18–25 years, 92% of whom identified as female, with 40% of the participants from underserved urban communities recruited through schools, the others recruited through universities and social media platforms. Pre- to post-program measures revealed increases in emotional expression (30%–75%), self-efficacy (35%–70%), and social connectedness (40%–80%), with a reduction in anxiety symptoms (60%–25%). These changes were statistically significant (paired-samples t = 6.06, df = 119, p = 0.0018), suggesting CAP’s assertion that emotional recalibration can occur through symbolic and rhythmically structured practices rather than through verbal processing alone.

For GEMAH-SYD (Australia), the arts component adapted programme finished with N = 40 participants aged between 18–25 years recruited from culturally and linguistically diverse urban communities via social media platforms. Emotional articulation increased (40%–82%), self-efficacy rose (38%–76%), and social connectedness improved (45%–85%), while anxiety symptoms declined (55%–22%). Statistical significance was confirmed via paired t-test (t = 5.82, df = 39, p < 0.002). Additional validated outcomes, as reported in STATA analyses, included significant improvements in Presence, Meaning, Positive Affect, and Life Satisfaction (all p ≤ 0.05), reinforcing the robustness of these findings.

Figure 4 displays pre- and post-intervention outcomes for GEMAH-KB (Pakistan) and GEMAH-SYD (Australia). Both programmes demonstrated substantial post-intervention improvements across all domains, with notable increases in emotional expression (EE), self-efficacy (SE), and social connectedness (SC), and a marked reduction in anxiety symptoms (AN). These results highlight the effectiveness of CAP-aligned participatory practices across culturally distinct settings.

FIGURE 4

Comparative outcomes of GEMAH programmes per region.

3.5 Comparative analysis

However, Whānau Ora is not solely a youth mental health programme, but a government-supported commissioning approach spanning health, housing, education, and cultural identity. Its effectiveness is evaluated through whānau-led outcomes frameworks. Both created affectively charged, rhythmically structured environments that facilitated emotional recalibration. Practices such as Māori kapa haka, karakia, and whakapapa, alongside GEMAH’s storytelling and group art, enabled participants to regulate emotions, strengthen social connection, and restore a sense of belonging. Participants described feeling “held” by collective rhythm, with emotional shifts occurring without the need for verbal introspection or diagnostic framing.

The effectiveness of these programmes lies not in generic “artmaking” but in ritualized, embodied aesthetic engagement. By mobilizing sound, rhythm, and symbolic participation, both models established co-regulatory spaces where nervous systems synchronized, and identities cohered. Emotional well-being was reframed as a relational, culturally embedded process rather than an individual pathology.

Quantitative outcomes confirmed these effects. Whānau Ora participants consistently reported increased psychological safety and relational grounding, while GEMAH showed significant improvements in emotional expression, self-efficacy, and social connectedness across Pakistan and Sydney cohorts. Anxiety symptoms declined markedly in both contexts.

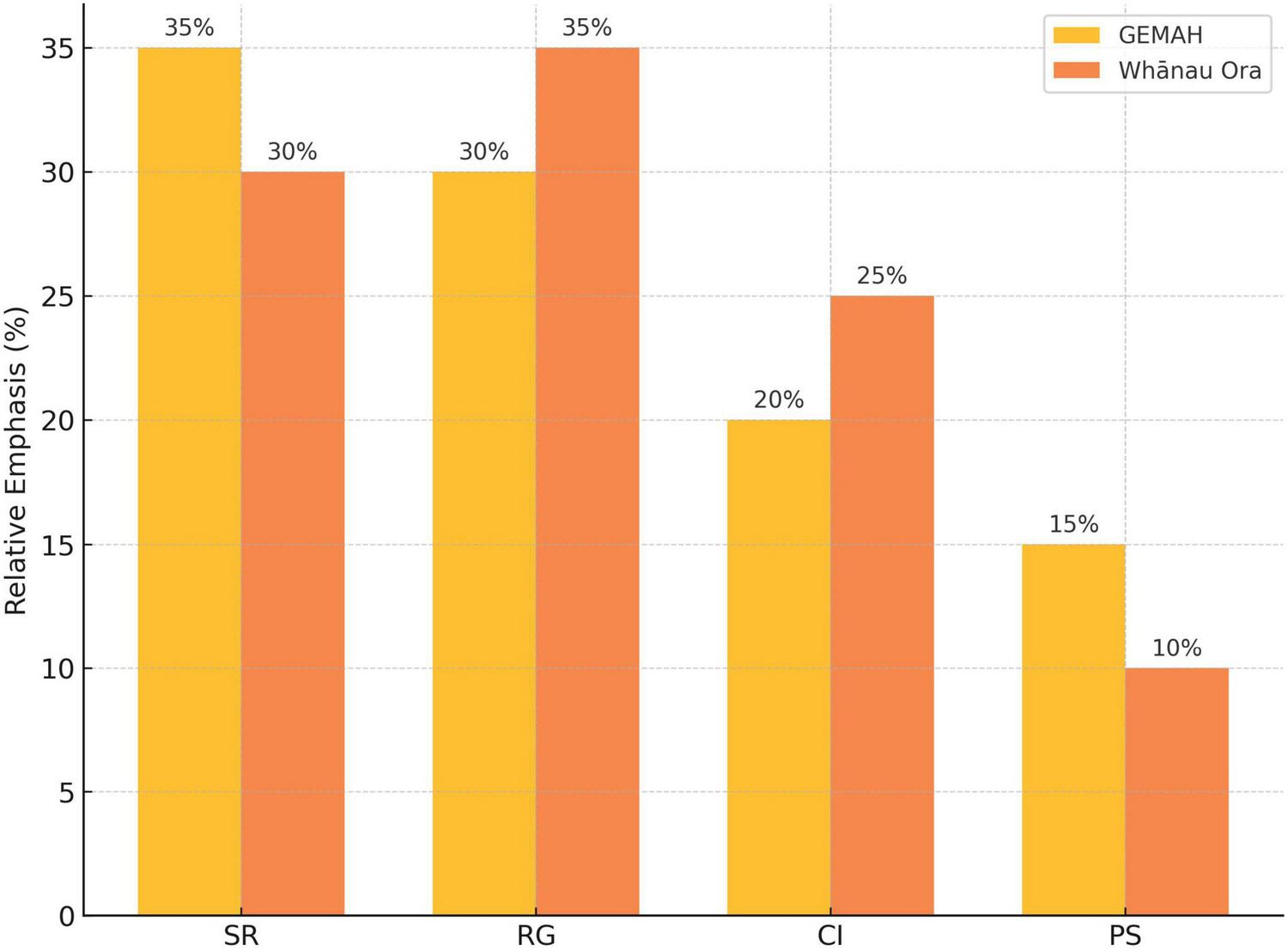

Figure 5 displays a grouped bar chart illustrating the relative emphasis of CAP-aligned outcome domains across GEMAH and Whānau Ora programmes. GEMAH showed greater emphasis on symbolic and ritual emotional regulation (SR) and psychological safety (PS), while Whānau Ora prioritized relational grounding and belonging (RG) and cultural identity reinforcement (CI), reflecting their respective cultural contexts. SR = Symbolic/Ritual Emotional Regulation; RG = Relational Grounding and Belonging; CI = Cultural Identity Reinforcement; PS = Psychological Safety.

FIGURE 5

Comparative CAP-aligned outcomes.

These findings are consistent with RANZCP’s assessment of Whānau Ora as an evidence-based, culturally safe model that embeds Te Ao Māori values in service delivery and whānau-led outcomes.

Culture-as-Practice’s adaptability across diverse settings are clearly defined through integrated health approaches that utilize participatory arts. Whether grounded in Māori cosmology or adapted to postcolonial urban realities using Arts-based education, both models steer clear of diagnostic reductionism in favor of culturally resonant, non-clinical tools. Their success illustrates that symbolic and embodied practices function as effective technologies of care, offering scalable, community-led alternatives to conventional mental health approaches in post-pandemic contexts.

4 Discussion

This review demonstrates that the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework offers a culturally grounded and theoretically robust alternative to conventional biomedical models of youth mental health care. Evidence from Whānau Ora (Aotearoa New Zealand) and GEMAH (Pakistan and Australia) indicates that CAP-aligned practices foster measurable improvements in emotional regulation, self-efficacy, social connection, and cultural identity. These findings are especially salient in the post-pandemic context, where youth face heightened emotional fragmentation due to disrupted community life, digital saturation, and cultural disconnection. By positioning healing as a collective, embodied, and symbolically mediated process, CAP addresses gaps left by dominant clinical paradigms and offers a scalable approach aligned with global mental health priorities (Health Foundation., 2023).

Conventional biomedical and clinical frameworks conceptualize youth mental health as an individual pathology, relying on diagnosis, verbal articulation, and cognitive insight. While effective in some cases, these approaches often fail to resonate with young people whose emotional lives are embedded in symbolic, relational, and aesthetic forms of meaning-making (Kirmayer and Gómez-Carrillo, 2019; Watters, 2010). For culturally diverse or marginalized youth, these models can feel alienating, particularly when they demand verbal disclosure or impose diagnostic categories that do not align with lived experience (Lavallée and Gagné-Julien, 2024). Reports on global health inequities bring to our attention the disproportionate impact of these systemic failures (Burnet Institute., 2023). The CAP framework, extending insights from the Culture-as-Interaction (CAI) model (Weinrabe and Murphy, forthcoming), directly challenges this pathology-focused orientation by reframing emotional distress as a rupture in cultural, relational, and symbolic infrastructures (Coninx and Stephan, 2021; Coninx, 2023). Healing, in this framework, emerges not through individualized therapeutic insight but through restored rhythm, belonging, and shared symbolic participation. This perspective resonates with Kirmayer and Gómez-Carrillo’s (2019) concept of cultural affordances for coherence but extends it by offering a practical methodology grounded in participatory arts and cultural practices.

A key innovation of CAI that is often overlooked in clinical discourse is its engagement with sound practices as relational scaffolding (see Weinrabe and Asoulin, 2026). CAI highlights that non-linguistic vocalizations–sighs, tone, laughter, rhythmic movement–shape emotional presence long before language develops. Regulation, in this sense, is felt before it is spoken. CAP builds directly on this insight, offering structured cultural environments in which embodied synchrony and emotional attunement precede and often replace verbal processing. For youth alienated by talk-based therapies, this orientation is critical.

Therefore, one of CAP’s most distinctive contributions is its emphasis on sonic and rhythmic participation as generative mechanisms of regulation rather than as expressive by-products. Drawing on affective neuroscience, CAP frames music, rhythm, and ritual not as decorative or symbolic metaphors but as physiological interventions. Research shows that rhythmic participation modulates the autonomic nervous system, enhances vagal tone, stimulates oxytocin release, and fosters interpersonal trust and co-regulation (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Koelsch, 2009; Porges, 2011; Kreutz, 2014; Thaut et al., 2014). Group singing, drumming, and improvisation activate the amygdala, insula, and brainstem, producing synchrony across participants and creating shared emotional safety (Du et al., 2020; Koelsch, 2014). This perspective resonates strongly with Burnet Institute.’s 2023, 2008, 2017) claims that musical interactions partially constitute emotional regulation, on both an individual and collective level. Cochrane argues that emotional coherence is not reducible to internal mechanisms but emerges through shared intentionality, embodied resonance, and environmental feedback loops. CAP operationalizes this theory in applied settings: group-based aesthetic forms function as “emotional technologies,” actively shaping affective experience across bodies and environments. Youth participating in Whānau Ora and GEMAH frequently described CAP activities as “safe,” “calming,” or “a place where my feelings don’t need words,” affirming that symbolic expression can substitute for symptom description and that collective rhythm can stabilize states of distress without verbal disclosure.

In CAI’s terms, these practices interface with both the “plumbing” of bodily affective systems and the “scaffolding” of external symbolic structures (Weinrabe and Murphy, forthcoming). Participants often reported “feeling more grounded” or “getting back into my body” during shared artistic or ritual practices. These experiences demonstrate how external symbolic forms restructure internal rhythms, creating a neurocultural feedback loop where aesthetic participation reorganizes bodily states.

Another key contribution of CAI, and by extension CAP, is its conceptualization of culture as enacted participation rather than inherited tradition. This distinction is particularly important for youth navigating diasporic, colonized, or hybrid identities, for whom pre-existing cultural narratives may feel inaccessible or fragmented (Haslanger, 1995; Sherwood, 2013). CAP allows coherence to emerge not through static cultural scripts but through doing, making, and being-with–principles long embedded in experiential and arts-based pedagogies (Heyes, 2018). For youth in postcolonial or hybrid settings, CAP’s participatory focus provides flexible, adaptive entry points for cultural grounding. Whānau Ora’s kapa haka and GEMAH’s group artmaking demonstrate how even fragmented cultural forms can become living infrastructures of care when enacted collectively. In these contexts, identity formation and emotional regulation are mutually reinforcing as youth reconnect with collective rhythm and shared narrative, they reconstruct a sense of belonging that supports well-being.

Culture-as-Practice’s principles align closely with global mental health priorities, particularly the World Health Organization (WHO).’s (2005) call for “less reliance on specialist psychiatric services and greater investment in culturally responsive, community-based models of care” (World Health Organization (WHO)., 2005, p. 42). In the same report, WHO also issued “an urgent call to develop innovative mental ill-health prevention programs,” asserting that “prevention of mental disorders is a public health priority” (World Health Organization (WHO)., 2005, p. 15). Several policy-relevant implications emerge. CAP is low-cost and scalable, requiring no specialized clinical infrastructure; community facilitators, artists, and educators can deliver CAP-aligned practices in schools, community centers, and grassroots organizations (Appleby, 2025; World Health Organization (WHO)., 2021). Because CAP embeds care within familiar cultural forms, it is perceived as culturally legitimate and non-stigmatizing, encouraging engagement from youth who might otherwise reject clinical services. Sustaining CAP, however, requires investment in training facilitators with both artistic expertise and trauma-informed relational competencies. Importantly, CAP is not positioned as a replacement for clinical models but as a complementary first-line approach, reducing demand on overstretched clinical systems by providing preventive and early-intervention care. This integrative positioning reflects broader calls for interdisciplinary approaches to youth mental health (Bie et al., 2024).

Culture-as-Practice contributes to an emerging paradigm shift from individualized, diagnosis-driven models to relational, culturally embedded approaches. It reframes emotional suffering not as internal dysfunction but as a rupture in shared symbolic infrastructure, a rupture that can be repaired through participatory, aesthetic reconnection. This theoretical move rejects pathology as a deficit, instead positioning cultural participation as a generative resource for resilience and recovery. The Global South is at the forefront of this shift. Initiatives such as Whānau Ora and GEMAH are not merely filling gaps in care but redefining mental health systems from the ground up, demonstrating that community-led, culturally embedded care can be both empirically robust and scalable. By establishing feedback loops between symbolic form and biological synchrony, CAP provides a framework in which culture is not peripheral to care, it is care itself. This perspective resonates with Vygotsky’s (1984) classic insight that art as a whole functions as a cultural form of emotional regulation, shaping collective meaning rather than serving as a peripheral aesthetic activity.

5 Limitations

While the Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework offers a compelling reorientation of youth mental health care, several limitations warrant reflection. First, CAP’s effectiveness is deeply contingent on the presence of vibrant cultural practices and embedded facilitators. In contexts where cultural infrastructure has been disrupted–through colonization, displacement, or the erosion of intergenerational knowledge–additional investment is needed to support cultural revitalization and train facilitators with both artistic and relational competencies. Without this approach, CAP risks becoming performative rather than transformative.

Second, CAP’s resistance to standardization and diagnostic framing poses challenges within institutional systems that prioritize replicable, evidence-based models. While CAP’s strength lies in its cultural specificity and symbolic richness, this same flexibility complicates evaluation through conventional metrics. Developing alternative forms of assessment that capture affective, relational, and embodied outcomes remains a critical area for further research and practice.

Third, although CAP has gained traction through community organizations, events and NGOs, its broader impact depends on systemic integration. To be truly scalable, CAP must enter the mainstream–not simply as a set of participatory practices, but as a legitimate model of emotional regulation. This requires institutional actors in education, public health, and policy to engage with CAP’s epistemological foundations, rather than appropriating its forms while stripping away their cultural and symbolic meaning. The challenge is to embed CAP within existing systems without rendering it reductive or generic.

6 Conclusion

The Culture-as-Practice (CAP) framework repositions culture not as a backdrop to care, but as care itself–a living infrastructure through which emotional life is regulated, shared, and restructured. By centering symbolic participation, embodied resonance, and collective meaning-making, CAP offers a fundamental departure from dominant models of youth mental health, which often rely on diagnosis, individualization, and clinical intervention. In the wake of COVID-19, with its widespread disruptions to social and emotional life, CAP provides a timely and necessary alternative: a framework that is scalable, adaptive, and grounded in the cultural logics of the communities it serves.

We argue that the Global South is already leading this shift–driven by necessity, cultural continuity, and creative resilience. Models emerging from Aotearoa New Zealand, Pakistan, and other postcolonial contexts are not simply filling gaps in care; they are generating integrative, community-based systems that align with WHO’s mental health priorities and anticipate decolonized approaches to well- being. These initiatives do not merely use culture as an engagement strategy–they recognize culture as the foundation of emotional regulation itself.

Culture-as-Practice exemplifies this movement. It reframes youth mental health not as the fixing of individual disorder, but as the renewal of meaning, rhythm, and relational coherence. Whānau Ora and GEMAH show that CAP-based approaches can generate measurable improvements in emotional well- being, identity, and connection–particularly for youth navigating systemic marginalization and post-pandemic dislocation.

While challenges remain in scaling, evaluation, and institutional adoption, CAP offers a pluralistic, low-cost, and culturally resonant path forward. It calls for systems of care that are not only more inclusive, but more attuned to the symbolic, aesthetic, and collective dimensions of emotional life. The Global South is not only responding to the crisis–it is actively reimagining the future of mental health care.

Statements

Author contributions

AW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We thank the Australian Research Council (ARC) for the award of Discovery Project (DP) DP170103855 on “Culture, Cognition, and Mental Illness” to Dominic Murphy, The University of Sydney.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. OPEN AI was used to typographically edit and reference check the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1647419/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aagaard J. (2021). Postdigital youth: A sociomaterial perspective on learning, technology, and development.Cham: Springer.

2

Anyon Y. Bender K. Kennedy H. Dechants J. (2018). A systematic review of youth participatory action research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, youth outcomes, and future directions.Health Educ. Behav.45865–878. 10.1177/1090198118769357

3

Appleby J. (2025). Trauma-Informed mental health: Supporting young people involved with child protection services.Aus. Soc. Work78458–470. 10.1080/0312407X.2025.2526205

4

Barnett L. Vasiu M. (2024). Embodied approaches to youth trauma recovery: Arts-based neurocultural interventions.Child Adolesc. Mental Health Rev.2945–61. 10.3389/fnbeh.2024.1422361

5

Basu S. Banerjee B. (2020). Impact of environmental factors on mental health of children and adolescents: A systematic review.Child. Youth Serv. Rev.119:105515. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105515

6

Bennett T. Clarke E. Sayers J. (2023). Cultural determinants of youth mental health: A global perspective.Glob. Mental Health J.10:e14. 10.1017/gmh.2023.14

7

Bie F. Yan X. Xing J. Wang L. Xu Y. Wang G. et al (2024). Rising global burden of anxiety disorders among adolescents and young adults: Trends, risk factors, and the impact of socioeconomic disparities and COVID-19 from 1990 to 2021.Front. Psychiatry15:1489427. 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1489427

8

Boardsworth K. Barlow R. Wilson B. J. Wilson Uluinayau T. Signal N. (2024). Toward culturally responsive qualitative research methods in the design of health technologies: Learnings in applying an Indigenous Mâori-Centred approach.Int. J. Qual. Methods23:16094069241226530. 10.1177/160940692412265

9

Bitonte R. A. De Santo M. (2014). Art therapy: An underutilized, yet effective tool.Mental Illness6:5354. 10.4081/mi.2014.5354

10

Block V. J. Haller E. Villanueva J. Meyer A. Benoy C. Walter M. et al (2022). Meaningful relationships in community and clinical samples: Their importance for mental health.Front. Psychol.13:832520. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.832520

11

Blood A. J. Zatorre R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.9811818–11823. 10.1073/pnas.191355898

12

Braun V. Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology.Qual. Res. Psychol.377–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

13

Burnet Institute. (2023). Youth mental health in the post-COVID landscape: Emerging evidence and policy directions.Melbourne: Burnet Institute.

14

Bux D. B. Van Schalkwyk I. (2022). Creative arts interventions to enhance adolescent well-being in low-income communities: An integrative literature review.J. Child Adoles. Mental Health341–29. 10.2989/17280583.2023.2277775

15

Cochrane T. (2008). Expression and extended cognition.J. Aesthetics Art Criticism66329–340. 10.1111/j.1540-6245.2008.00314.x

16

Cochrane T. (2017). “Group flow,” in The Routledge companion to embodied music interaction, edsLesaffreM.MaesP. J.LemanM. (London: Routledge), 133–140.

17

Cochrane T. (2018). The emotional mind: A control theory of affective states.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

18

Committee on Publication Ethics (Cope). (2017). COPE ethical guidelines for peer reviewers.Eastleigh: Committee on Publication Ethics.

19

Coninx S. (2023). Affect, regulation and the relational body: Theoretical approaches and applications.London: Routledge.

20

Coninx S. Stephan A. (2021). Emotion and culture: Empirical and conceptual perspectives.Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci.20747–764. 10.1163/24689300-bja10019

21

Creative Australia. (2023). Creating well-being: Public engagement with arts and health.Canberra: Creative Australia.

22

Creswell J. W. Plano Clark V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

23

Czamanski-Cohen J. Weihs K. L. (2023). The role of the arts in healing trauma.Front. Psychol.14:1123450. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1208901

24

de Witte M. Spruit A. van Hooren S. Moonen X. Stams G. J. (2021). Effects of arts-based interventions on depression, anxiety, and quality of life in adults: A meta-analysis.Arts Psychother.72:101746. 10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897

25

del Río, Diéguez M. Peral Jiménez C. Sanz-Aránguez, Ávila B. Bayón Pérez C. (2024). Art therapy as a therapeutic resource integrated into mental health programmes: Components, effects and integration pathways.Arts Psychotherapy91:102215. 10.1016/j.aip.2024.102215

26

Du S. Jiang W. Yu Y. Wu C. (2020). Neural mechanisms of music therapy in depression: A systematic review.Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.118482–495. 10.1038/s41561-019-0530-4

27

Durkheim E. (1955). The elementary forms of religious life.New York: Free Press.

28

Fancourt D. Finn S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?.Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

29

Fancourt D. Warran K. Aughterson H. (2019). Evidence on the relationship between the arts and health.BMJ367:l6377. 10.1136/bmj.l6377

30

Fomina A. Lee R. Chang P. (2023). Barriers to culturally congruent youth mental health services: A systematic review.Community Mental Health J.5977–92.

31

Frentzen E. Fegert J. M. Martin A. et al (2025). Child and adolescent mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: An overview of key findings from a thematic series.Child Adoles. Psychiatry Mental Health19:57. 10.1186/s13034-025-00910-8

32

GEM Ltd and City of Sydney. (2023). GEMAH-SYD Programme Evaluation Report: Creative Mental Health Interventions for Urban Youth Post-COVID.Sydney: GEM Ltd.

33

GEM Ltd and Karachi Biennale Trust. (2021). GEMAH Programme Pakistan: Emotional Wellbeing Through Arts-Based Interventions During COVID-19.Karachi: GEM Ltd.

34

Golden S. Yip T. Reeve K. (2024). Global youth mental health and the arts: A systematic review.Youth Mental Health Rev.121–27. 10.1186/s12916-023-03226-6

35

Haslanger S. (1995). Ontology and social construction.Philos. Topics2395–125. 10.5840/philtopics19952324

36

Health Foundation. (2023). Understanding the crisis in young people’s mental health.Available online at: https://www.health.org.uk/ (accessed September 4, 2025).

37

Heyes C. J. (2018). Cognitive gadgets: The cultural evolution of thinking.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

38

Hommel S. Kaimal G. (2024). Arts-Based approaches to promote mental health and well-being.United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group.

39

Huebner B. Schulkin J. (2022). Emotional habits: Synaptic scripts and the biology of feeling.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

40

Hugh-Jones S. Munford R. (2025). Youth participatory arts for post-pandemic recovery: An international review.Int. J. Art Therapy3015–32. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.118343

41

Kaimal G. Ray K. Muniz J. (2016). Reduction of cortisol levels and participants’ responses following art making.Art Therapy3374–80. 10.1080/07421656.2016.1166832

42

Khan R. Akter F. Rahman M. Amin N. Rahman M. Winch P. J. (2025). Socio-demographic factors associated with mental health disorders among rural women in Mymensingh. Bangladesh.Front. Psychiatry16:1446473. 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1446473

43

Kirmayer L. J. Gómez-Carrillo A. (2019). Agency, embodiment and enactment in psychosomatic theory and practice.Med. Human.45169–182. 10.1136/medhum-2018-011618

44

Kirmayer L. J. Jarvis G. E. (2019). Culturally responsive services as a path to equity in mental healthcare.HealthcarePapers1811–23. 10.12927/hcpap.2019.25925

45

Knight R. C. Dunning D. L. Cotton J. Franckel G. Ahmed S. P. Blakemore S. J. et al (2025). Investigation of the mental health and cognitive correlates of psychological decentering in adolescence.Cogn. Emot.39465–475. 10.1080/02699931.2024.2402947

46

Koelsch S. (2009). A neuroscientific perspective on music therapy.Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1169374–384. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04592.x

47

Koelsch S. (2010). Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions.Trends Cogn. Sci.14131–137. 10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.002

48

Koelsch S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions.Nat. Rev. Neurosci.15170–180. 10.1038/nrn3666

49

Kreutz G. (2014). Does singing facilitate social bonding?Music Med.651–60. 10.1177/1943862114528596

50

Kumar I. K. Shen J. Ferguson C. Picard R. W. (2025). Connecting through comics: Design and evaluation of cube, an arts-based digital platform for trauma-impacted youth.Proc. ACM Human-Comp. Interact.91–22. 10.1145/3710949

51

Lavallée Z. Gagné-Julien A.-M. (2024). Affective injustice, sanism and psychiatry.Synthese2041–23. 10.1007/s11229-024-04731-8

52

Levy M. (2020). Culturally responsive therapeutic models for Māori.N. Zealand J. Psychol.49102–110.

53

Lincoln Y. S. Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry.Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

54

Malchiodi C. A. (2012a). Handbook of art therapy, 2nd Edn. New York: Guilford Press.

55

Malchiodi C. A. (2012b). “Art therapy and the brain,” in Handbook of art therapy, 2nd Edn, ed.MalchiodiC. A. (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 17–26.

56

Malchiodi C. A. (2015). “Neurobiology, creative interventions, and childhood trauma,” in Creative interventions with traumatized children, 2nd Edn, ed.MalchiodiC. A. (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 3–23.

57

Marciano L. Ostroumova M. Schulz P. J. Camerini A. L. (2022). Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Front. Public Health9:793868. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.793868

58

Markus H. R. Kitayama S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation.Psychol. Rev.98224–253. 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

59

McGorry P. D. Hickie I. B. Kotov R. Schmaal L. Wood S. J. Allan S. M. et al (2025). New diagnosis in psychiatry: Beyond heuristics.Psychol. Med.55:e26. 10.1017/S003329172400223X

60

McGorry P. D. Mei C. Dalal N. Alvarez-Jimenez M. Blakemore S. Browne V. et al (2024). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on youth mental health.Lancet Psychiatry11731–774. 10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00163-9

61

Mendelsohn J. B. Fournier B. Caron-Roy S. et al (2022). Reducing HIV-related stigma among young people attending school in Northern Uganda: Study protocol for a participatory arts-based population health intervention and stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial.Trials23:1043. 10.1186/s13063-022-06643-9

62

Mental Health, and Foundation, N. (2022). Creative Wānanga Evaluation Report.Auckland: MHFNZ.

63

Murphy D. (2015). “Deviant deviance”: Cultural diversity in DSM-5,” in In The DSM-5 in perspective: Philosophical reflections on the psychiatric Babel, (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 97–110.

64

Murphy D. (2023). “Concepts of disease and health,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2023 Edn, edsZaltaE. N.NodelmanU. (Stanford: Stanford University).

65

Murphy D. (2025). “Nature and construction in psychiatry,” in Oxford Handbook of the Philosophy of Medicine, ed.BroadbentA. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

66

Murphy D. Donovan C. Smart G. L. (2020). “Mental health and well-being in philosophy,” in Explaining health across the sciences, edsShollJ.RattanS. (Cham: Springer), 97–114.

67

Nguyen A. T. P. Ski C. F. Thompson D. R. Abbey S. E. Kloiber S. Sheikhan N. Y. et al (2025). Health and social service provider perspectives on challenges, approaches, and recommendations for treating long COVID: A qualitative study of Canadian provider experiences.BMC Health Services Res.25:509. 10.1186/s12913-025-12590-3

68

Orange C. (2015). The Treaty of Waitangi, 2nd Edn. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

69

Pavarini G. Smith L. M. Shaughnessy N. Mankee-Williams A. Thirumalai J. K. Russell N. et al (2021). Ethical issues in participatory arts methods for young people with adverse childhood experiences.Health Expect.241557–1569. 10.1111/hex.13314

70

People’s Palace Projects. (2022). Arts, care and post-pandemic recovery: A global overview.London: Queen Mary University of London.

71

Porges S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, self-regulation.New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

72

Racine N. McArthur B. Cooke J. Eirich R. Zhu J. Madigan S. et al (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis.JAMA Pediatrics1751142–1150. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

73

Ranjbar N. Erb M. Mohammad O. Moreno F. A. (2020). Trauma-Informed care and cultural humility in the mental health care of people from minoritized communities.Focus188–15. 10.1176/appi.focus.20190027

74

Restrepo C. Godoy N. Ortiz-Hernández N. Bird V. Acosta M. Uribe J. M. et al (2022). Role of the arts in the life and mental health of young people that participate in artistic organizations in Colombia: A qualitative study.BMC Psychiatry22:757. 10.1186/s12888-022-04396-y

75

Ross H. (2023). Emotional ecologies: Affect, symbol, and the making of mental health.London: Routledge.

76

Salimpoor V. N. Benovoy M. Larcher K. Dagher A. Zatore R. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music.Nat. Neurosci.14257–262. 10.1038/nn.2726

77

Seah T. H. S. Coifman K. G. (2024). Effects of scaffolding emotion language use on emotion differentiation and psychological health: An experience-sampling study.Cogn. Emot.10.1080/02699931.2024.2382334[Epub ahead of print].

78