- School of Humanities, Social Sciences and Law, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

Introduction: Internationally, there has been a drive toward developing an inclusive and equitable educational system which promotes lifelong learning for all. This is reflected in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 and its associated targets. The current study focuses on some of the challenges and tensions associated with inclusive practice in non-formal education settings for children and young people with a disability, specifically sensory loss, from the perspective of parents/carers and professionals/volunteers.

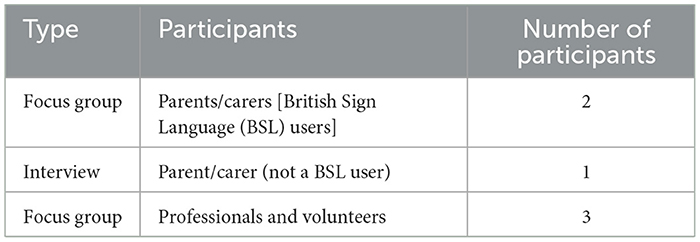

Methods: A commissioned project, conducted in one local authority in Scotland in 2022, investigated the experiences of children and young people with sensory loss (deaf and/or visual impairment) of participating in activities, in school and in the community, with children with and without sensory loss; the opportunities and challenges associated with engaging in these activities; and the perceived benefits. As part of a larger study which gathered the views of children and young people with sensory loss, a virtual focus group was conducted with two parents/carers who are British Sign Language (BSL) users and a semi-structured interview with a parent who is not a BSL user. Furthermore, a virtual focus group was undertaken with three professionals/volunteers working with children and young people with sensory loss (deaf and/or visual impairment).

Results: Findings from the study highlight some of the tensions associated with inclusion in non-formal education settings.

Discussion: There are implications for practice, such as awareness raising for peers and adults; offering more opportunities for children and young people to mix socially with their peers in accessible and well-resourced environments outside school; the importance of seeking children's views about the non-formal activities they like to participate in; and the importance of raising awareness of the benefits for children and young people with sensory loss of being with others with sensory loss. Although the research was conducted in one locality in Scotland, the insights are relevant to an international audience.

Introduction

Internationally, there appears to be limited research that has focused on the inclusion of children and young people (CYP) with a sensory loss in out of school activities, offering both non-formal and informal learning opportunities. Hannah (2023) identified five studies over the period 2013–2023 which covered a range of types of sensory loss including visual impairment (De Schipper et al., 2017; Ghanbari et al., 2016; Perkins et al., 2013), visual impairment and hearing impairment (Engel-Yeger and Hamed-Daher, 2013), and deafblindness (Štěrbová and Kudláček, 2014). Since 2023, the author identified three studies investigating the participation of students with sensory loss in non-formal education including deaf or hard of hearing (Ferreira et al., 2023; García-Terceño et al., 2023) and partially or totally blind (Papadopoulou and Vasilaki, 2024). This highlights the need to undertake further research in this field.

For the purposes of this study, the term “sensory loss” was used as an umbrella term to cover a range of sensory impairments, including visual impairment, deafness, and deafblindness. Sensory loss (or sensory impairment) is a term used by third sector organizations (e.g., Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland), and local authorities (e.g., South Lanarkshire Council, Lancashire County Council). Typically, this term encapsulates deafness and hearing impairment, blindness and visual impairment, and the dual impairment of deafblindness. In scholarly literature, when referring to sensory loss, Crowe and Dammeyer (2021) acknowledge the wide range of subgroups of children with vision and/or hearing loss and distinguish between congential and acquired hearing loss in the context of language development, communication and social interaction. They also highlight the importance of the severity of sensory loss; whether it is total or profound or whether there is residual hearing and/or vision. Finally, they highlight the significance of the sensory loss being associated with other disabilities. Similarly, McKittrick (2022), in a study involving adult participants from the US and Canada which investigated the benefits of teaching self-determination skills to students with sensory loss, used the term sensory loss to encapsulate students who are deaf or hard of hearing or who have a visual impairment.

CYP with sensory loss face a range of challenges which can impact on their ability to participate in activities with peers. These include language development and communication (Crowe and Dammeyer, 2021; Manford et al., 2024) although different types of sensory loss impact on language development in different ways (Crowe and Dammeyer, 2021). Other aspects include the accessibility of environments (Hannah, 2023); accessing information due to visual and/or hearing loss, and difficulties in social interaction with adults and peers (Cheng et al., 2025). Given the identified benefits for children with disabilities of participating in leisure activities, including their physical and mental wellbeing, and overall development (Mogo et al., 2020; Powrie et al., 2020; Vänskä et al., 2020), it is important that there is a better understanding of available opportunities and of perceived barriers and facilitators to taking part in out of school activities.

This paper reports on a study which aimed to investigate the perceived challenges and tensions associated with inclusive practice in non-formal education settings for CYP with sensory loss from the perspective of parents/carers and professionals/volunteers working with CYP with sensory loss (deaf and/or visual impairment). Although conducted in one locality in Scotland it is anticipated that the findings, conclusions and recommendations will be of interest and relevance to a wider audience.

Literature review

International policy context

Several international treaties have reinforced the rights of children to education. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (UNICEF, 1989) incorporated 54 articles including Article 28 (1) which stipulates that “States Parties recognize the right of the child to education, and with a view to achieving this right progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity” (p. 11) and Article 23 (1) which specifies that “States Parties recognize that a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child's active participation in the community” (p. 9). In line with the UNCRC, the Salamanca Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994) provided a commitment to include all children with additional needs in mainstream schools and to adapt the educational provision to meet their needs. Furthermore, the right to education and the promotion of inclusion is a cornerstone of The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (United Nations, 2006) with Article 24 advocating “the right of persons with disabilities to education ….” and that “States Parties shall ensure an inclusive education system at all levels and lifelong learning” (section 1). More recently, Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), one of 17 goals of the United Nations 2030 agenda for sustainable development (United Nations, 2015) aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (p. 14).

Changing perspectives on inclusion

Inclusion is about creating an environment where all individuals, whatever their background (race, culture etc.), and individual characteristics (gender, age, abilities etc.) are valued and respected (Lekh, n.d.). In the context of education, definitions of inclusion have developed in recent years. In relation to children with disabilities, there has been a shift from an expectation that students will attend educational provision without substantial changes to the environment and/or approaches to teaching and learning, an approach referred to as integration (Hausstätter and Jahnukainen, 2014). In contrast, inclusion is viewed as a way of adapting the educational environment to meet the diverse needs of students in a way that respects them as individuals (Hausstätter and Jahnukainen, 2014). A more recent development has been a shift from viewing educational inclusion as pertaining to students with disabilities to one which is viewed as pertaining to all students (Ainscow, 2016).

In the Scottish context, where the current study took place, this shift in conceptualization is reflected in national legislation, such as the Additional Support for Learning (ASL) Act 2004 (amended in 2007 and 2016). This Act acknowledged that all children may have additional support needs at some stage in their education, which could be temporary or long-term in nature. A strong position on inclusion for children and young people (CYP) is also reflected in Scottish policy documentation such as the National Improvement Framework (Scottish Government, 2023). Recently, as part of a national discussion on the future of Scottish education, the vision statement included a statement which reflects the national position of viewing educational inclusion as pertaining to all students “All learners are supported in inclusive learning environments which are safe, welcoming, caring, and proactively address any barriers to learning and inequities that exist or arise. Education in Scotland nurtures the unique talents of all learners ensuring their achievement, progress, and wellbeing” (Campbell and Harris, 2023, p. 15).

Types of learning

It is interesting that cited international treaties do not stipulate the type of education being referred to. In the context of this paper, it is helpful to consider how the terms “formal”, “non-formal” and “informal” are defined in extant literature. In a literature review, Johnson and Majewska (2022) set out to define “formal,” “non-formal” and “informal” learning as well as the perceived advantages and disadvantages of these different forms of learning. In relation to definition of terms, they concluded that formal learning is distinguished by the learning taking place in an institution (e.g., school, university); there are individuals (e.g., teachers, lecturers) planning and running the activities; there are structured learning goals organized in a linear fashion as part of a formal curriculum; and there is a system of grading which may result in certification. In contrast, non-formal learning takes place outside of compulsory educational provision and in any setting. This type of learning is viewed as having a greater focus on learners' needs and interests; there tends to be more choice on the part of learners; more self-directed learning; less reliance on formal qualifications; more focus on practical knowledge and skills rather than cognition; and a greater emphasis on experiential learning. Johnson and Majewska (2022) highlight several examples of non-formal learning identified in research literature such as learning in youth centers, music learning in community groups, and activities taking place out of school, which may be associated with the formal educational curriculum, such as visits to museums and after school sports clubs. Johnson and Majewska (2022) highlight difficulties in defining informal learning e.g., some people use the terms non-formal and informal interchangeably. Despite these acknowledged difficulties, the authors highlight several features of informal learning, including the lack of structure; the range of settings where informal learning can occur; the lack of recognition through qualifications; the role of intrinsic motivation; and the absence of a formal curriculum. Other researchers concur with Johnson and Majewska (2022) that formal learning tends to take place in an institution such as a school (e.g., Benkova et al., 2020) whereas non-formal learning takes place outside a formal educational context (e.g., Juan-Morera et al., 2022). Formal learning, in contrast with non-formal learning is evaluated and certified (e.g., Benkova et al., 2020), and non-formal learning is voluntary in nature (e.g., Juan-Morera et al., 2022). In relation to informal learning, researchers agree that the activities can take place in a range of settings in everyday life (e.g., Juan-Morera et al., 2022).

The position adopted by the author in this study is that formal education takes place in school and that non-formal and informal education take place in the community and/or at home with friends and/or family members. As the research focus was the participation of CYP with sensory loss in out of school activities, potentially this could encapsulate both non-formal and informal learning opportunities. However, for the purpose of this study, the author was interested in non-formal activities, such as Brownies (for girls aged 7–10 years and part of the Girlguiding movement in the UK), youth camps, gymnastics and dancing clubs, rather than informal activities with friends and/or family members, such as going out on dog walks or visits to the local park.

Literature on non-formal education

There is a substantial and growing body of research into inclusion in formal education settings such as schools, colleges and universities (e.g., Filippou et al., 2025; Nesterova, 2023). In comparison, there has been less emphasis on non-formal learning, although it is acknowledged that there has been important research in this area highlighting and advancing a human rights agenda (e.g., Sandell, 2016).

In relation to non-formal educational settings, several studies were identified which focussed on issues of inclusion for students with disabilities and other vulnerable groups e.g., poorer communities. The studies adopted a range of methodologies, including qualitative (Brestovanský et al., 2018; Zakaria, 2023), quantitative (Ullah et al., 2021), and mixed methods (Benkova et al., 2020). A fifth study took the form of a systematic literature review (Juan-Morera et al., 2022). A range of foci, i.e. types of non-formal learning, were found in the four empirical studies, including museums (Zakaria, 2023), non formal basic education schools (Ullah et al., 2021), and youth centers and youth organizations (Benkova et al., 2020; Brestovanský et al., 2018). Findings indicate a positive impact of museums on students' learning and social interaction although several barriers to inclusivity were identified, including accessibility, adequate services and staff training (Zakaria, 2023); highlight the flexibility offered by non formal basic education schools and the inclusivity of approaches to learning to meet the needs of children, including those with disabilities (Ullah et al., 2021); and that youth centers utilizing inclusive practices are effective in achieving social inclusion for the targeted vulnerable groups (Benkova et al., 2020). Adopting a different focus, Brestovanský et al. (2018) set out to examine the conceptual understanding of youth workers and youth (aged 15–25 years) in relation to inclusion, diversity, and equality (IDE), as well as their lived experiences of inclusive approaches. Findings indicate that youth workers and youth differed in their understanding of IDE principles. The implementation of IDE approaches appeared to happen in a spontaneous fashion rather than being embedded in formal policies and training, practices which appeared to be accepted by the youth workers. In contrast, young people appeared to have an implicit understanding of IDE in a holistic sense i.e., not separating out the terms.

In their systematic literature review, with no time restriction, Juan-Morera et al. (2022) investigated the role of inclusive musical practices in promoting equality and social justice. The researchers concluded that over the last 5 years there was evidence of increasing interest in inclusive musical practices. Furthermore, they found that the most studied population groups were individuals with disabilities and those at risk of exclusion and the most studied age ranges were young people followed by children.

There were several strengths and limitations identified in the aforementioned empirical studies. A strength of Zakaria's (2023), study was providing a space for five students with disabilities to air their views, in addition to garnering the views of museum professionals. This approach aligns with Article 12 of UNCRC (UNICEF, 1989). Limitations in the studies include a potential lack of representativeness of study participants (Brestovanský et al., 2018; Zakaria, 2023); the study being limited to one department in Punjab (Ullah et al., 2021); the representativeness of the selected museums (Zakaria, 2023); and the potential bias of museum professionals (Zakaria, 2023).

From this review of extant literature, there is a clear need for further research focusing on issues of inclusion for CYP with disabilities and other vulnerable groups in relation to non-formal education. A specific focus on CYP with sensory loss is considered in the next section.

Participation of students with sensory loss in non-formal or informal education

There appears to be limited literature focusing on the participation of students with sensory loss in non-formal or informal education. Hannah (2023) found only five studies, over the period 2013-2023, which investigated the participation of children and young people with sensory loss (visual impairment and/or deaf) in leisure activities. It is argued that most leisure activities could be defined as either non-formal or informal education with the former referring to structured activities such as sports clubs, gymnastics clubs and dancing classes, and the latter referring to less structured activities undertaken with friends and/or family, such as going on walks with the family dog. Since 2023, the author identified three studies in the category of non-formal education (Ferreira et al., 2023; García-Terceño et al., 2023; Papadopoulou and Vasilaki, 2024) one of which used a mixed methods approach (Ferreira et al., 2023) and the other qualitative methodology (García-Terceño et al., 2023). Interestingly, two studies had a science focus with one investigating approaches to teaching and learning to support the participation of children, aged 6–16 years, who are deaf or hard of hearing in a scientific activity outside the school context (García-Terceño et al., 2023) and the other investigating the deployment of an accessibility strategy, specifically videos guides in Brazilian Sign Language, to support deaf people visiting traveling science centers in Brazil (Ferreira et al., 2023). The third study by Papadopoulou and Vasilaki (2024) investigated the design of a museum educational programme, described as a type of informal learning linked to the teaching of history and geography in formal education settings, for a group of students including those who are partially or totally blind. Unfortunately, the paper does not evaluate the implementation of the programme, so it is not possible to comment on its effectiveness. Both the empirical studies offered interesting insights into how to provide inclusive learning spaces for children of school age who are deaf or hard of hearing. Nevertheless, there are identified limitations, including the wide age range of the study sample (Ferreira et al., 2023; García-Terceño et al., 2023); the absence of questions which would have provided more information on the participants (Ferreira et al., 2023); and inability to measure the prior knowledge of participants (Ferreira et al., 2023). Through gathering the views of parents/carers of children and young people (CYP) with sensory loss and professionals/volunteers working with this group about opportunities and experiences of participating in non-formal learning activities, this study aims to contribute to the limited body of knowledge in this area.

Sensory loss: definition, global and local context

In terms of definition, although sensory loss could affect one or more of the senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell, etc.) and could range from a mild impairment to a complete loss of a sense, the term “sensory loss” as adopted in this study refers to children with a loss to sight and/or hearing. In their report, which provides a strategic framework for meeting the needs of people with a sensory impairment in Scotland, the Scottish Government (2013) use the term “sensory impairment” to capture a range of impairments including “people with varying degrees of hearing loss, sight loss and also with loss of both senses” (p. 2).

Globally, the levels of sensory loss are significant. The World Health Organisation (2021) reported that more than 1.5 billion people experience some degree of hearing loss. In the context of this study, it is interesting that they report that the highest incidence of hearing loss is in children under the age of 5 years, with ear infections being a common cause of hearing loss in childhood. In relation to visual impairment, the World Health Organisation (2019) report that globally there are at least 2.2 billion people with a vision impairment. The report states that “Vision impairment occurs when an eye condition affects the visual system and one or more of its vision functions” (p. 10). It is worth noting that the 2.2 billion figure is thought to include at least 1 billion people with a vision impairment that could have been prevented. Furthermore, the figure is thought to be an underestimate as information on the prevalence and causes of vision impairment in children is limited.

In Scotland, where this study took place, 34,492 (0.75%) people (all age groups) are registered blind or partially sighted (Scottish Government, 2010). However, it is important to note that these figures are likely to be an underestimate due to the voluntary nature of registration. In relation to children of school age with a visual impairment, in Scotland there were 4,930 (percentage not reported) according to the Scottish Government's Pupil Census 2021 (Scottish Government, 2021). Unlike visual impairment, there is no central register of deafness in Scotland. Action on Hearing Loss estimates that there are 850,000 (16.7%) people with hearing loss in Scotland (NHS Education for Scotland, n.d.). In relation to deafblindness, it is estimated that there are 5,000 (0.09%) deafblind people in Scotland, which includes children and adults, with a large proportion being over the age of 65 years (NHS Education for Scotland, n.d.). The Consortium for Research in Deaf Education (CRIDE) reported in their 2024 survey findings that there were 3,558 (percentage not reported) deaf children in Scotland (Consortium for Research in Deaf Education, 2024).

Methodology

Focus, aim and objectives of study

Given the paucity of research investigating the participation of students with sensory loss in non-formal or informal education, the current study aims to explore the challenges and tensions associated with inclusive practice in non-formal education settings for CYP with sensory loss. The study was commissioned by a third sector organization in February 2022 with the overall aim of scoping out and identifying the feasibility of developing a young people's sensory service in one locality in Scotland. The aim of the sensory service would be to help the CYP people grow and develop as individuals (including their confidence, self-esteem, and interpersonal skills).

The specific objectives of the research were to:

• Explore opportunities to engage in out of school activities with other children/young people.

• Explore opportunities to engage in out of school activities with other children/young people who have sensory loss.

• Explore perspectives on being with other children/young people who have sensory loss.

• Explore perspectives on taking part in activities with other children/young people who have sensory loss.

The data which forms the basis for this paper was gathered as part of a wider study which adopted a mixed methods research paradigm (Chatterji, 2004) underpinned by critical realism (Scott, 2005).

Three participant groups were involved in the wider study (children/young people, parents/carers, professionals/volunteers). Findings from the CYP data were reported in a previous paper (Hannah, 2023). This paper focuses on the views of parents/carers of CYP with sensory loss and professionals/volunteers working with CYP with sensory loss from a specific geographical location in Scotland.

Although the data was collected in June/July 2022, participants were able to comment on provision prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, during the period of restrictions, and in the period of recovery following the pandemic.

Establishment of reference group

A Reference Group was established to ensure that stakeholders with relevant experience, either personally or as professionals/volunteers, were involved from the outset to advise the researcher and shape the direction of the project. This approach aligned with the researcher's adoption of a co-production methodology (Arribas Lozano, 2018). Members of the Reference group included young people with sensory loss; parents/carers of CYP with sensory loss; individuals working for statutory services and third sector organizations for CYP with sensory loss; individuals working for the third sector organization which had commissioned the research; and individuals involved in the Young People's Sensory Service (YPSS) in another geographical area in Scotland. Thus, stakeholders with experiential knowledge participated at different phases of the project.

The Reference Group was involved at different stages of the planning and implementation process. In the early stages of the project, members provided feedback on draft versions of questionnaires, focus group/interview questions, participant information sheets and consent forms, prior to the researcher applying to her institution for ethical approval. This participation ensured that issues such as language and terminology, assent/consent of participants, and accessibility were discussed at an early stage. During the implementation phase, members of the Reference Group were able to support the recruitment process and were kept informed of progress. In the final stage of the project, members were able to give feedback on the draft research report, including interpretation of the findings and recommendations. Although the researcher had some professional experience of working with CYP with sensory loss in educational settings, the support of members of the Reference Group proved invaluable.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from University of Dundee in May 2022. Throughout the study, participants were assured of their rights, including the voluntary nature of their involvement and anonymity in reporting of findings.

Participants

As part of the wider study, virtual focus groups were used with three groups of individuals:

1. Children and young people with sensory loss

2. Parents/carers of children and young people with sensory loss

3. Professionals and volunteers working with children and young people with sensory loss

This paper focuses on groups 2 and 3. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure that the participants' selection was based on specific characteristics or criteria relevant to the research objectives (Cohen et al., 2018). It was not intended to generalize the findings but to gain insights into the phenomenon of interest which may be transferable to other populations or settings (Polit and Beck, 2010). In this study, the phenomenon of interest was the participation of CYP with sensory loss in non-formal learning activities. The inclusion criteria were that parents/carers should have a child of nursery or school age with sensory loss who is educated and lives in the target locality for the research. Recruitment to the parents/carers and professionals/volunteers focus groups was facilitated by members of the Reference Group who had established contacts and relationships.

Focus groups and interview

The two focus groups and the interview were conducted in June/July 2022. One focus group was conducted remotely using Microsoft Teams with two parents/carers who were British Sign Language (BSL) users (see Table 1). The researcher was the main facilitator although two other adults were present, including a BSL interpreter. Both parents/carers were female. One parent had two male children, one of whom was deaf. That child was of pre-school age and attended a childminder. He had been taught to use sign language but could also use oral language. The other parent had three children (two girls and one boy) who were all deaf. They were aged 16, 10 and 3 years. The eldest child was at secondary school; the middle child was at a mainstream primary school and the youngest child was at nursery. All three children were able to use sign language. One of the parents was in the same room as the BSL interpreter and the other adult. The other parent joined remotely from abroad as she was on holiday. Children were present during the session, but they did not contribute to the conversation. The focus group was 43 min duration.

A virtual focus group method was chosen for pragmatic reasons due to cost and time savings. Another reason was that individuals had become more familiar and confident with conducting remote meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lobe et al., 2020). The researcher checked in advance that the participants had suitable technology (internet access, hardware and software). At the beginning of the session, the researcher checked that everything was working effectively (audio, video and transcription software). Limitations in the use of online focus groups are acknowledged such as difficulties identifying non-verbal and visual cues (Lobe et al., 2022). To mitigate this, Lobe et al. (2022) suggest reducing the size of the focus group to 3–5 participants, a recommendation adopted in this study.

For pragmatic reasons, namely availability, a third parent was interviewed on her own using Microsoft Teams (see Table 1). This parent was not a BSL user. She had one child (female, aged 9 years) who was deaf, had hearing aids, and had other additional needs and health issues. She attended a mainstream primary school. There were no other adults present. The interview was 22 min duration.

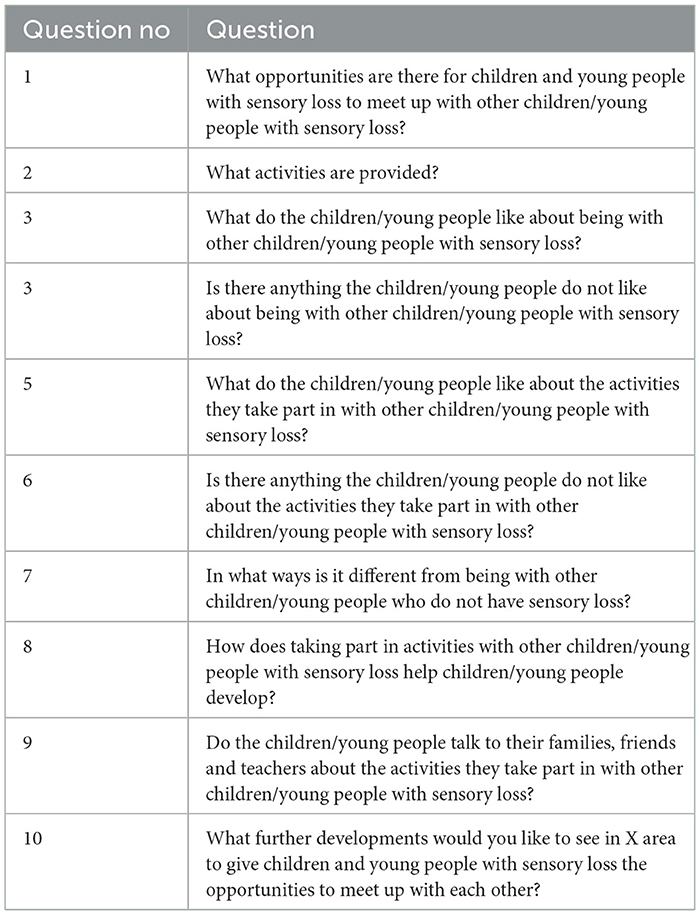

There was one focus group, comprising three participants, for professionals and volunteers (see Table 1). Two of the participants worked for third sector organizations supporting children/young people with sensory loss and the third person worked for a statutory organization. The focus group was 41 min duration.

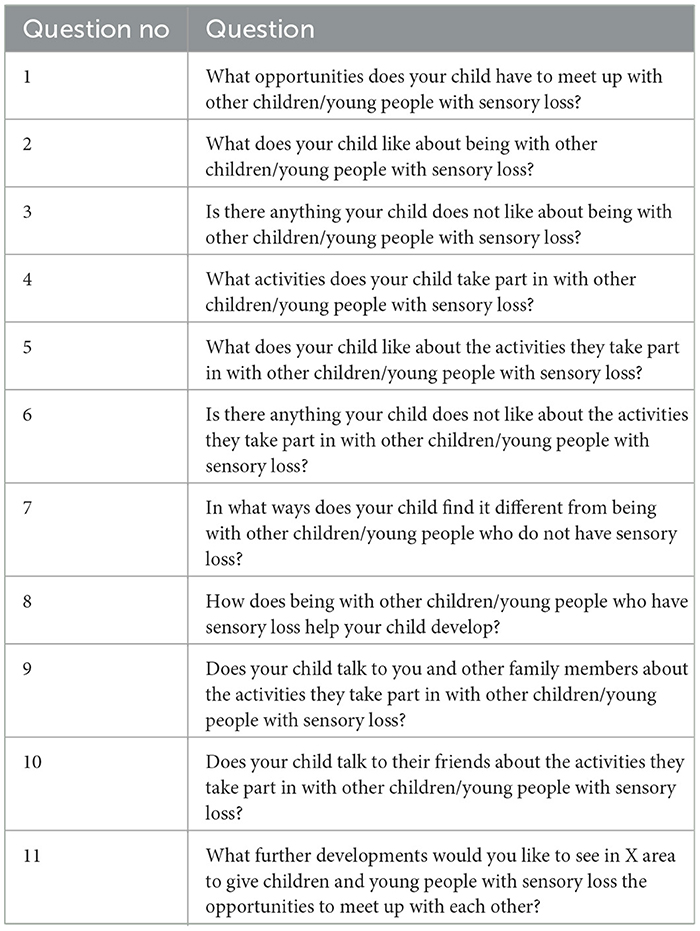

The focus group and interview questions were linked to the objectives of the study (see Tables 2, 3). As such, they were designed to explore the participants' views of different aspects of CYP's experiences of being with other CYP with sensory loss. The questions were shared in advance with members of the Reference group so feedback was provided prior to implementation.

Both focus groups and interview were conducted remotely and recorded using Microsoft Teams. Transcriptions of the recordings were checked for accuracy and anonymised by the researcher by cross-reference to the recordings. This process also enabled the researcher to become immersed in the data.

Data analysis

The researcher utilized a form of qualitative content analysis (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004) to analyse the qualitative focus group and semi-structured interview data. The unit of analysis was the focus group or interview text for a particular category of participants (parents/carers; professionals/volunteers). There were three stages to the process. Stage 1 involved the abstraction of condensed meaning units; defined by Graneheim and Lundman (2004) as “words, sentences or paragraphs containing aspects related to each other through their content and context” (p. 106). Stage 2 involved the collation of the condensed meaning units, viewed as a whole, and identification of sub-themes using an inductive approach given the paucity of research in this area. During this process there was ongoing cross-reference to the original text. Stage 3 involved the development of themes from the sub-themes, with ongoing reference to the original text. An acknowledged limitation is that data analysis was conducted by a sole researcher as this may result in increased bias and subjectivity (Cohen et al., 2018). The researcher considered member checking of transcripts but decided against it for pragmatic reasons, namely the time lag between data collection (June/early July) and completion of the transcriptions/data analysis and the timing (school holidays in Scotland in July/August) and the additional time and resources from the researcher and participants (Motulsky, 2021) which were not possible given the timeline for the commissioned project. Furthermore, the researcher was cognizant of the debate around member checking improving the quality of qualitative research (e.g., Thomas, 2017).

Results

Views of parents/carers of children and young people with sensory loss

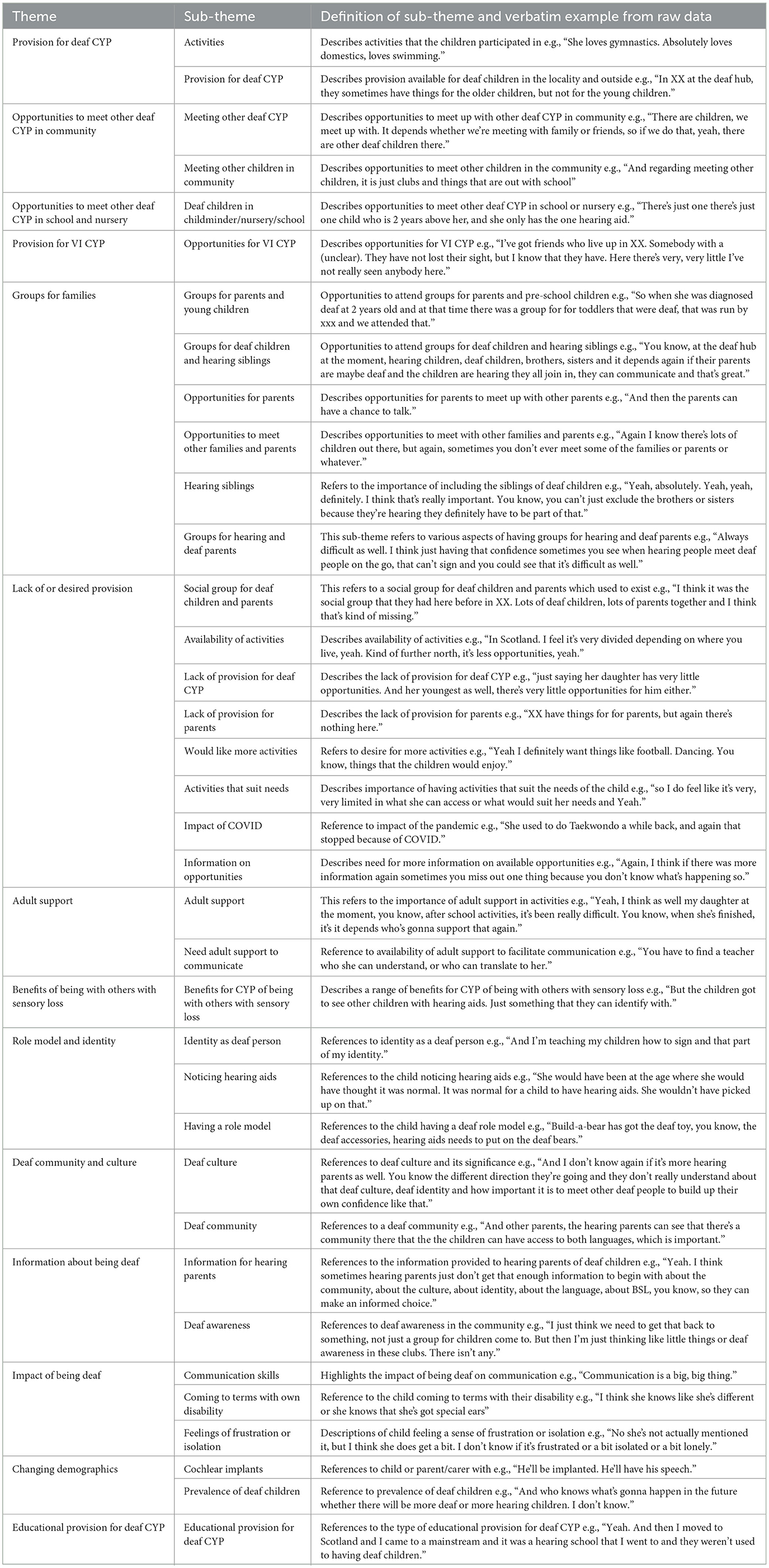

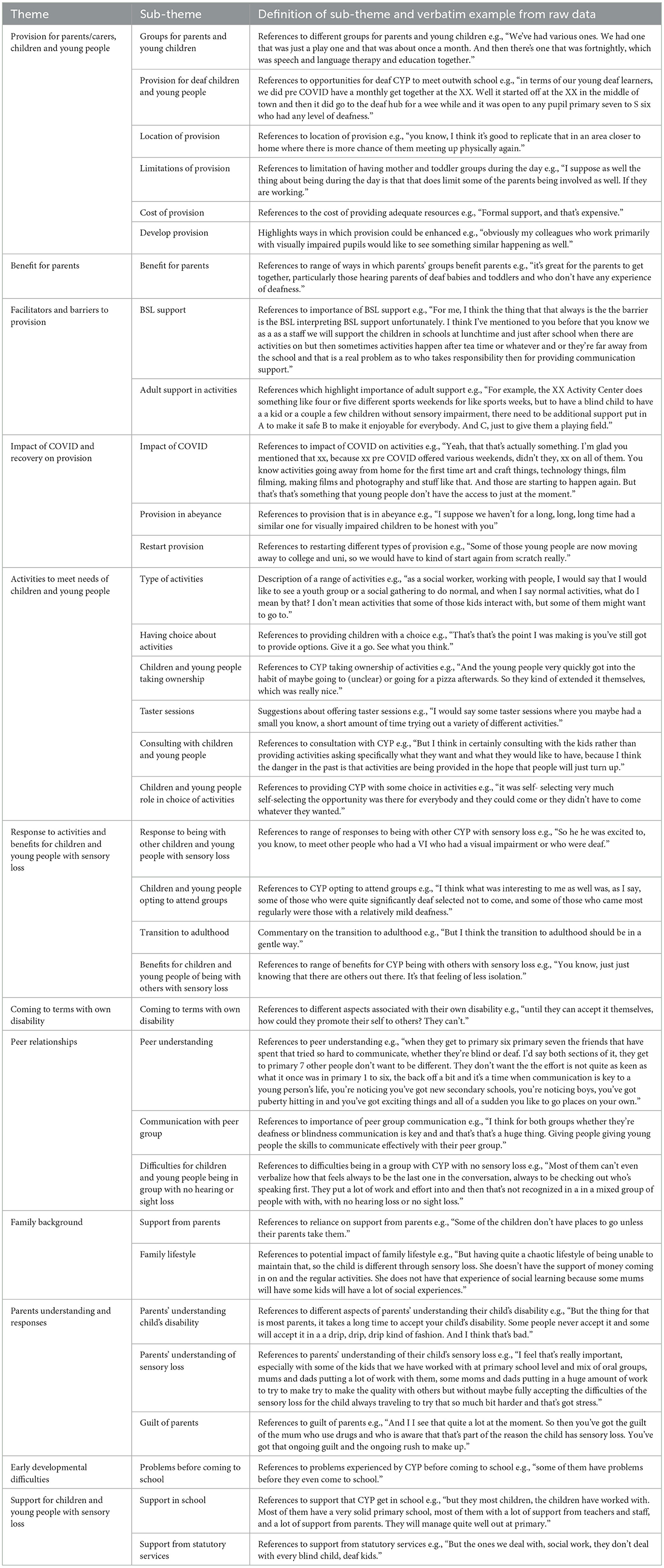

Thirty-six sub-themes were generated, and these were grouped into 14 themes as illustrated in Table 4.

The theme “Provision for deaf CYP” comprised two sub-themes “Activities” and “Provision for deaf CYP.” The parent in the semi-structured interview mentioned activities that her daughter enjoys, namely gymnastics and swimming. In the focus group with two parents, there was reference to provision for deaf children and young people in other areas of Scotland. In XX area, it was noted that the Deaf Hub has activities for older children but not young children.

The theme “Opportunities to meet other deaf CYP in community” encapsulated the sub-themes “Meeting other deaf CYP” and “Meeting other children in community.” It was apparent that the children had opportunities to meet other children in the community through the parents' networks. There was the sense that parents would welcome more opportunities as their children were not meeting up with other deaf children in these settings.

Captured by the theme “Provision for VI CYP,” there was a brief reference to opportunities for children and young people with a visual impairment to meet up. Participants were not aware of provision in the local area but referred to activities for people who are visually impaired in another area in Scotland.

The theme “Groups for families” encapsulated six sub-themes which shared the need to consider the wider family context. Sub-themes were “groups for parents and young children”; “opportunities to meet other families and parents”; “groups for deaf children and hearing siblings”; activities for “hearing siblings”; “opportunities for parents”; and “groups for hearing and deaf parents.”

Parents thought it was important to include the hearing siblings of deaf children in activities.

A strong theme which emerged was the “Lack of or desired provision.” This theme encapsulated eight sub-themes. There was a perceived need for more provision for deaf children and young people in the geographical area. Sometimes, there were activities, but they were too far away from the locality. As one parent commented “…like that my daughter loves dancing. In primary school they had the dancing club and then when she moved to high school there was like. That was it. There was no dancing. There was no opportunities or there was, but it was too far.” The sub-theme “Information on opportunities” reflected comments on the need for better communication about available opportunities.

The theme “adult support” reflected the perceived need to offer support to help children and young people access activities. This was particularly pertinent in out of school activities. The importance of having an adult interpreter in activities was highlighted.

The theme “Benefits of being with others with sensory loss” captured the perceived benefits for children of being with other children with sensory loss. Parents in the semi-structured interview and focus group commented on different benefits. This included deaf children being understanding; being able to identify with other children with hearing aids; feeling more comfortable being with other deaf children; improving confidence; and developing friendships. An illustrative quote: “Personally, when I see him with deaf children, I see he's more. You know, he's definitely more comfortable and more confident when he's mixing with his deaf peers.”

A related theme was “Role model and identity” which comprised three sub-themes: “Identity as deaf person” “Noticing hearing aids” and “Having a role model.” Parents in the focus group and semi-structured interview referred to the importance of having a role model and identity as a deaf person. One parent talked about the impact for her child of having role models in the form of toys, characters in books and TV programmes.

Her child's response to seeing the bear in Build-a-bear store: “That's like me. Or she's like me” …. “Or that bear is me. She kind of puts herself in the shoes of that character or that toy.” Learning sign language was seen as an important element of deaf identity.

A related theme was “Deaf community and culture” which comprised the two sub-themes of “deaf culture” and “deaf community.” This theme emerged from comments made by deaf parents. This appeared to relate to a sense of belonging and being part of a deaf community with its own culture.

In the theme “Information about being deaf” parents in both the semi-structured interview and focus group were of the view that it was important to raise “deaf awareness” and/or provide “information for hearing parents.” The former sub-theme emerged from one parent's comments about raising deaf awareness with the public. The latter sub-theme emerged from comments about the need to provide more information to parents when their child is diagnosed about the deaf community, deaf culture, identity and BSL. One parent commented: “Yeah, I think hearing parents should maybe more information on BSL and identity and the whole culture and community. I don't think it's just enough.”

A theme which emerged was the “Impact of being deaf” which comprised three sub-themes “Communication skills,” “Coming to terms with own disability” and “Feelings of frustration or isolation.” Captured by this theme were parents' comments about their child feeling different; feelings of frustration; feeling isolated; and problems of communication with hearing peers and the resultant impact on social interaction.

In terms of context, the theme “Changing demographics” captured the impact of medical developments such as “Cochlear implants.” Parents in the BSL focus group thought this could result in less signing as individuals will be able to develop oral communication skills.

The final theme “Educational provision for deaf CYP” reflected comments made by parents in the BSL focus groups. This captured changes in educational provision in various parts of Scotland and comparison with other parts of the UK. There appeared to be a negative view about the move towards deaf children being in mainstream schools.

Views of professionals/volunteers working with children or young people with sensory loss

Thirty-four sub-themes were generated, and these were grouped into 12 themes as illustrated in Table 5.

Subsumed within the theme “Provision for parents/carers, children and young people” were six sub-themes where participants highlighted a range of provision for children and young people with sensory loss and their parents/carers. Some of these activities had been previously provided and others were currently available. Provision included groups for parents and young children (babies and toddlers) run by education services and speech and language services in X locality.

The theme “Benefit for parents” incorporated participants' comments on the perceived benefits to parents of being involved in parents' groups. Other activities mentioned included monthly get togethers after school for secondary aged pupils; the annual X day event; and a deaf football club for pupils in P4 up to S6 and above established by XX Social Club. It was acknowledged that there were some limitations in having groups for parents/carers and young children during the day as the parents/carers may be working.

The theme “Provision for parents/carers, children and young people” encapsulated the sub-theme “cost of provision” highlighting the costs associated with providing support for children and young people with sensory loss to participate in activities. The support referred to various aspects associated with the organization of activities/events, undertaking risk assessments, and provision of resources (people and equipment). On a positive note, one of the participants offered a recent example of an organization who had provided their services for free. The “location of provision” was another sub-theme. Some organizations, such as the National Deaf Children's Society, offered activities but these did not necessarily take place in X locality. Participants commented on positive aspects of these activities e.g., children and young people can link up with others. However, they also noted that it may be difficult to maintain relationships even with the support of technology. So, on balance, it was felt that it would be important to have activities nearer to the home locality.

The theme “Facilitators and barriers to provision” incorporated of the sub-themes “BSL support” and “Adult support in activities.” BSL support was a significant factor for deaf children participating in activities in the community at evenings or weekends. For example, there is a cost associated with having a BSL interpreter which is not always factored into community activities. There was a view that this leads to inequity in terms of the individual's experience. The sub-theme “Adult support in activities” captured the perceived need to provide additional support for activities so that they are safe, enjoyable and provide a level playing field with children who do not have sensory loss.

The theme “Impact of COVID and Recovery on Provision” captured that some provision was in abeyance due to the pandemic and there was a desire to restart some of these activities. One example was a mother and toddler group for children with visual impairment. One participant stated “I'm not sure whether there would be an opportunity for our VI parents or parents of children with a visual impairment to have a similar experience, but it is quite limited.” Indeed, there were examples of a wish to extend activities e.g., plans to extend the deaf football club to provide an opportunity for parents to get together.

The theme “Activities to meet needs of children and young people” incorporated of six sub-themes. The importance of seeking children's views in relation to the range of activities was noted. In addition, the provision of taster sessions was considered important as it gives children the chance to try out activities they may not have considered.

The theme “Response to activities and benefits for children and young people with sensory loss” comprised four sub-themes. Two of the sub-themes related to how the children responded to being with other children and young people with sensory loss. There were examples of children responding positively e.g., children enjoying the deaf football club. However, there were examples of mixed responses e.g., being in the secondary group for deaf young people. So, it appears to be an individual response and this can change with age as reflected in one participant's comment: “But I always think that people that say no. no, no at 12 and 13 want it later on in life. They want to come back at 17 and 18 when they want to talk about it, so it's all about time and what they are, where they are at that time.” One of the sub-themes focused on the “Benefits for children and young people of being with others with sensory loss.” Where a child is in mainstream educational provision then they may be the only child with sensory loss in the school and may be unaware that there are other children like them who have a visual impairment or who are deaf. As one participant stated “And actually one of the focus groups we had, I think it was the primary one to three focus group that we had, there was a young lad who was picked up first by one of my colleagues and taken in a car to another school to pick up somebody else. And he was, you know, she was explaining to him again what was going to be happening at the focus group. And he was actually amazed that there were other children with a visual impairment elsewhere in XX, he had no concept of that whatsoever.” Knowing that there are other children like them leads to a reduction in feelings of isolation. Activities provide them with an opportunity to be with peers going through similar experiences. Being with other children who are deaf or have a visual impairment helps develop a stronger sense of identity. As one participant stated:

“I think it gives them a stronger sense of identity in terms of to being able to accept that they're not the only one that's got hearing loss and not the only one that's got a visual impairment.”

Another theme which emerged was around “Coming to terms with own disability.” This was seen as an important factor in children's personal development and that by accepting their disability children would be able to grow and develop as individuals. One participant commented “There's got to be some kind of acceptance of the disability they have because it's part of them. They can't change it.”

“Peer relationships” was another theme. It was acknowledged that there were difficulties for children and young people being in a group of peers with no hearing or sight loss. One participant highlighted the difficulty for a child to verbalize the effort required being part of group with no hearing or sight loss. It was deemed important to give young people, whether blind or deaf, the skills to communicate effectively with their peer group. However, it was also important to develop peer understanding.

The role of parents/carers and the family was captured in the two themes of “Family background” and “Parents' understanding and responses.” In relation to the former theme, parents could offer support through taking their children to activities outwith school. However, it was acknowledged that not all children have the same opportunities due to sociodemographic factors and family lifestyle. In relation to the latter theme, the importance of parents'/carers' understanding of sensory loss and their child's disability was highlighted. It was noted that some parents/carers have difficulty accepting their child's disability and the implications for their development. One of the participants commented on the guilt of mothers who use drugs and are aware that has caused the sensory loss.

One of the participants commented that some deaf and blind children have problems even before they come to school. This was captured within the theme “Early developmental difficulties.”

There were a few comments captured within the overarching theme “Support for children and young people with sensory loss.” These referred to the support offered in school and the support offered by social work services.

Discussion

This discussion compares data from parents/carers with that from professionals/volunteers.

Opportunities and challenges in participating in non-formal learning with other CYP

Findings pertaining to the first two objectives have been combined to explore the opportunities that CYP experience to participate in out of school activities, considered to be non-formal learning, with other CYP (with and without sensory loss). Parents/carers described a range of activities including gymnastics and swimming, arts and crafts, dancing, the Deaf Hub in the local area, albeit with age restrictions, and a dancing club located in a local primary school. Professionals/volunteers reported a wide range of opportunities including groups for parents and young children (babies and toddlers) run by local education services and speech and language services; monthly get togethers after school for secondary aged pupils; the annual X day event; a deaf football club for pupils in primary 4 up to secondary 6 and above, established by XX Social Club; and sports weekends and sports weeks. Extant research has identified a range of non-formal learning for students with disabilities and other vulnerable groups, including museums (Zakaria, 2023), non formal basic education schools (Ullah et al., 2021), and youth centers and youth organizations (Benkova et al., 2020; Brestovanský et al., 2018). For CYP with sensory loss, studies have focused on a scientific activity outside the school context (García-Terceño et al., 2023), traveling science centers in Brazil (Ferreira et al., 2023) and a museum educational programme (Papadopoulou and Vasilaki, 2024). This highlights the limited range of non-formal learning settings captured in previous research. An original contribution of the present study is that it has extended the range of non-formal education settings experienced by CYP with sensory loss. Furthermore, given the timing of the study (2022), the findings have captured information on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision for CYP with sensory loss, specifically in the Scottish context.

Both sets of participants highlighted challenges accessing non-formal learning activities. Parents/carers emphasized the importance of adult support, including BSL adult interpreters, to help CYP access such provision; and highlighted the paucity of provision in the local area. In a similar vein, professionals/volunteers commented that some organizations, such as the National Deaf Children's Society, offered activities but these did not necessarily take place in the local area. They highlighted the difficulties CYP with sensory loss experience being with a group of peers with no sensory loss illuminating the need to develop peer understanding. Furthermore, they noted that children do not have equal opportunities to take part in activities outside of school due to sociodemographic factors and family lifestyle. In addition, participants acknowledged limitations in having groups for parents/carers and young children during the day as parents/carers may be working. Professionals/volunteers highlighted a range of challenges including the costs associated with providing appropriate support to facilitate children and young people with sensory loss participating in activities. This support included risk assessments; provision of equipment resources; adult support so that children are safe, have an enjoyable experience and there is a level playing field with children who do not have sensory loss; and BSL support for deaf children participating in activities in the community at evenings or weekends.

The findings from this study confirm previous research. For example, this study highlighted the need for adult support resources and BSL interpreters, to facilitate the accessibility of provision. This aligns with Zakaria (2023) who noted several barriers to inclusivity including accessibility, and the provision of adequate services, and Ullah et al. (2021) who identified a lack of resources as a barrier to educational access in Pakistan. Furthermore, Brestovanský et al. (2018) identified economic obstacles in their study due to the cost of some provision. In the current study, sociodemographic factors impacted on equality of access for some children, and participants highlighted the costs associated with providing appropriate support.

The current study offers additional insights into perceived barriers to inclusion in non-formal education settings. Specifically, it highlighted challenges such as the paucity of provision in the local area; provision by third sector organizations which was geographical unsuitable; the need to educate peers without a sensory loss; and accommodating the availability of working parents/carers. However, it is acknowledged that findings reflect the unique location in Scotland where this study took place. For example, third sector organizations, such as the National Deaf Children's Society, did not offer activities in the area and this provision was difficult for families to access.

Experiences of CYP with sensory loss participating in non-formal learning with other CYP

Findings pertaining to the last two objectives have been combined to explore the experiences of CYP with sensory loss taking part in activities with other CYP (with and without sensory loss). Parents/carers commented on a range of benefits arising from being with other children with sensory loss, such as deaf children being understanding; being able to identify with other children with hearing aids; feeling more comfortable being with other deaf children; the importance of having a role model and identity as a deaf person; opportunities to develop friendships; and a positive impact on their confidence. In contrast, professionals/volunteers offered a more mixed picture. They highlighted perceived benefits of being with other children with sensory loss, e.g., knowing that there are other children like them leads to a reduction in feelings of isolation and helps develop a stronger sense of identity. In addition to providing specific examples of positive experiences, they offered examples of mixed responses e.g., being in the secondary group for deaf young people. It appeared to be an individual response, which can change with age. The professionals/volunteers made some helpful suggestions for future practice such as consulting with CYP about their preferred activities; and the provision of taster sessions to give CYP the chance to try out activities they may not have considered.

The benefits of participation of CYP with sensory loss in non-formal learning activities on social interaction has been identified in previous research. Identified benefits in extant research include providing life structure, better physical health and fitness, and improved wellbeing (Štěrbová and Kudláček, 2014); developing a health lifestyle and improved confidence levels (Perkins et al., 2013); and improved physical self-concept (De Schipper et al., 2017). This study has offered additional insights into the experiences of CYP with sensory loss in a specific locality in Scotland and the benefits of interacting with other children with sensory loss. Original insights include identification with other children with a sensory loss; social benefits such as developing friendships; and reduced feelings of isolation. The importance of role models and the impact on identity formation is particularly illuminative given its importance to an individual's development (Forber-Pratt et al., 2017).

Limitations

This study has contributed to the limited research base which has investigated the participation of CYP with sensory loss in non-formal education settings. It has provided additional insights into perceived barriers to inclusion in non-formal education settings; the benefits of interacting with other children with sensory loss; and has extended the range of non-formal education settings. Additional originality is offered given the unique setting of the study in one locality in Scotland with its distinctive provision; and the timing of the study (2022) capturing information on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision for CYP with sensory loss.

Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that there are several limitations. The first limitation is the small sample size. There were six participants, three parents/carers and three professionals/volunteers. It could be argued that this limits the generalisability of the findings although there was no intention to generalize the findings to a wider population. It is worth highlighting that a small sample size is not atypical in empirical studies involving CYP with sensory loss (e.g., six children with a visual impairment in De Schipper et al., 2017; 15 children who were deaf and hard of hearing in García-Terceño et al., 2023; five mothers of children with deafblindness in Štěrbová and Kudláček, 2014). The second limitation was that all the parents/carers were parents of deaf children, and it could be argued that this could have resulted in a bias toward the views of parents/carers of deaf children. This is reflected in the findings where parents/carers mainly focus on non-formal education for deaf children. To mitigate this, the professionals/volunteers worked with children/young people with a range of sensory loss (deaf and/or visually impaired). The findings from that data reflect provision for children who are deaf and/or visually impaired. The third limitation is the virtual nature of the focus groups and semi-structured interview which could have impacted on the researcher's ability to pick up on non-verbal cues. Finally, the study took place in one geographical area so the findings may not be representative of other areas.

Conclusion

There appears to be a paucity of research investigating the involvement of CYP with sensory loss in non-formal education settings. To contribute to the limited body of knowledge in this area, and to inform future research and practice, the current study explored some of the challenges and tensions associated with inclusive practice in these settings for CYP with sensory loss. This paper focuses on a subset of data from a commissioned study undertaken in 2022, namely the perspectives of parents/carers of CYP with sensory loss and of professionals/volunteers working with this group about opportunities and experiences of participating in non-formal learning activities.

The research findings have highlighted the limited opportunities for CYP with sensory loss of taking part in activities in non-formal education settings and the perceived challenges associated with this participation. A number of benefits for CYP with sensory loss of interacting with other CYP with sensory loss were indicated by both groups of participants. However, some examples of mixed responses were also offered.

There are several implications for practice from an inclusion perspective including awareness raising for adults and CYP without sensory loss; providing more opportunities for CYP with sensory loss to mix with their peers (with and without sensory loss) in accessible and well-resourced environments outside school; consulting with CYP with sensory loss about their preferred activities; and offering taster sessions to CYP.

In terms of future research, it is recommended that research exploring the inclusion of CYP with sensory loss in non-formal education settings should incorporate larger samples, and should be expanded to other areas in Scotland and other countries.

Whilst acknowledging limitations with the current study, including that it was conducted in one locality in Scotland, it is argued that the findings further our understanding of the benefits for CYP with sensory loss of participating in non-formal education. It has provided evidence of a clear and pressing need to provide more opportunities of this nature in community settings and to ensure that any provision is well-resourced and inclusive in nature. The findings should be used to inform policy and practice both in Scotland and internationally.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not available as permissions were not sought from those providing informed consent. Queries regarding the data should be directed to the author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Education & Social Work Research Ethics Committee, University of Dundee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EH: Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project received funding from a third sector organization.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of the parents/carers who participated in the focus group interviews, the parent who took part in the semi-structured interview and the professionals/volunteers who participated in the focus group interviews.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ainscow, M. (2016). Diversity and equity: a global education challenge. New Zealand J. Educ. Stud. 51, 143–155. doi: 10.1007/s40841-016-0056-x

Arribas Lozano, A. (2018). Knowledge co-production with social movement networks. Redefining grassroots politics, rethinking research. Soc. Move. Stud. 17, 451–463. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1457521

Benkova, K., Mareva, V., Vlaeva, N., and Georgieva, S. (2020). Non-formal educational practices as a tool for achieving social inclusion. J. Soc. Work Educ. Pract. 5, 5–45.

Brestovanský, M., Gubricová, J., Liberčanová, K., Bizová, N., and Geršicová, Z. (2018). Inclusion, diversity, equality in non-formal education through the optic of youth and youth workers. Acta Educ. Gen. 8, 94–108. doi: 10.2478/atd-2018-0019

Campbell, C., and Harris, A. (2023). All learners in Scotland matter: The national discussion on education final report. The Scottish Government.

Chatterji, M. (2004). Evidence on “what works”: an argument for extended-term mixed-method (ETMM) evaluation designs. Educ. Res. 33, 3–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033009003

Cheng, Y., Wang, S., Pavlopoulou, G., Hayton, J., and Sideropoulos, V. (2025). Mental health and quality of life in children and young people with vision impairment: a systematic review. Neurodiversity 3:27546330251346835. doi: 10.1177/27546330251346835

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education. 8th New York: Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9781315456539

Consortium for Research in Deaf Education (2024). 2024 report for Scotland. Available online at: https://www.ndcs.org.uk/advice-and-support/all-advice-and-support-topics/research-and-data-childhood-deafness/education-support-research/consortium-research-deaf-education-cride-reports (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Crowe, K., and Dammeyer, J. (2021). “Sensory loss,” in Handbook of pragmatic language disorders: Complex and underserved populations (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 215–246. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-74985-9_9

De Schipper, T., Lieberman, L. J., and Moody, B. (2017). “Kids like me, we go lightly on the head”: Experiences of children with a visual impairment on the physical self-concept. Br. J. Visual Impair. 35, 55–68. doi: 10.1177/0264619616678651

Engel-Yeger, B., and Hamed-Daher, S. (2013). Comparing participation in out of school activities between children with visual impairments, children with hearing impairments and typical peers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 3124–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.049

Ferreira, A. T. S., Alves, G. H. V. S., Vasconcelos, I. A. H., Souza, T. V. D. A., and Fragel-Madeira, L. (2023). Analysis of an accessibility strategy for deaf people: videos on a traveling science center. Front. Educ. 8:1084635. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1084635

Filippou, K., Acquah, E. O., and Bengs, A. (2025). Inclusive policies and practices in higher education: a systematic literature review. Rev. Educ. 13:e70034. doi: 10.1002/rev3.70034

Forber-Pratt, A. J., Lyew, D. A., Mueller, C., and Samples, L. B. (2017). Disability identity development: a systematic review of the literature. Rehabil. Psychol. 62, 198–207. doi: 10.1037/rep0000134

García-Terceño, E. M., Greca, I. M., Santa Olalla-Mariscal, G., and Diez-Ojeda, M. (2023). The participation of deaf and hard of hearing children in non-formal science activities. Front. Educ. 8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1084373

Ghanbari, S., Ghasemi, F., Evazzadeh, A., Tohidi, R., Jamali, A., and Shayanpour, F. (2016). Comparison of participation in life habits in 5–11-year-old blind and typical children. J. Rehab. Sci. Res. 3, 67–71.

Graneheim, U. H., and Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 24, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Hannah, E. F. S. (2023). Perspectives of children and young people with a sensory loss: opportunities and experiences of engagement in leisure activities. Front. Educ. 8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1248823

Hausstätter, R. S., and Jahnukainen, M. (2014). “From integration to inclusion and the role of special education,” in Inclusive education twenty years after Salamanca, eds. K. Florian, S. H. Rune (New York: Peter Lang), 199–131.

Johnson, M., and Majewska, D. (2022). Formal, non-Formal, and informal Learning: What are they, and how can we research them? Research report. Cambridge University Press and Assessment.

Juan-Morera, B., Nadal-García, I., and López-Casanova, B. (2022). Systematic review of inclusive musical practices in non-formal educational contexts. Educ. Sci. 13:5. doi: 10.3390/educsci13010005

Lekh, V. (n.d.). What is Inclusion and How Do we Implement It? Available online at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professional-development/teachers/inclusive-practices/articles/what-inclusion-and-how-do-we#: :text=Inclusion%20is%20a%20basic%20right,all%20barriers%2C%20discrimination%20and%20intolerance

Lobe, B., Morgan, D., and Hoffman, K. A. (2020). Qualitative data collection in an era of social distancing. Int. J. Qual. Met. 19:1609406920937875. doi: 10.1177/1609406920937875

Lobe, B., Morgan, D. L., and Hoffman, K. (2022). A systematic comparison of in-person and video-based online interviewing. Int. J. Qual. Met. 21:16094069221127068. doi: 10.1177/16094069221127068

Manford, C., Rajasingam, S., Allen, P. M., and Beukes, E. (2024). The barriers to and facilitators of academic and social success for deafblind children and young people: a scoping review. Br. J. Special Educ. 51, 332–346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12537

McKittrick, L. L. (2022). The benefits of teaching self-determination skills to very young students with sensory loss. Online Submission.

Mogo, E., Badillo, I., Majnemer, A., Duckworth, K., Kennedy, S., Symington, V., and Shikako-Thomas, K. (2020). Using a rapid review process to engage stakeholders, inform policy and set priorities for promoting physical activity and leisure participation for children with disabilities in British Columbia. Leisure/Loisir 44, 225–253. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2020.1760121

Motulsky, S. L. (2021). Is member checking the gold standard of quality in qualitative research?. Qual. Psychol. 8, 389–406. doi: 10.1037/qup0000215

Nesterova, Y. (2023). “Towards social justice and inclusion in education systems,” in Handbook of Education Policy. Series: Elgar handbooks in education (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing), 301–313. doi: 10.4337/9781800375062.00028

NHS Education for Scotland (n.d). Basic Sensory Impairment Awareness. Available online at: https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/25703/person-centred-care-zone/person-centred-resources/basic-sensory-impairment-awareness (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Papadopoulou, M., and Vasilaki, A. (2024). Designing an inclusive educational landscape through the conjunction of formal and informal educational settings. Cult. J. Cult. Tour. Art Educ. 4.

Perkins, K., Columna, L., Lieberman, L., and Bailey, J. (2013). Parents' perceptions of physical activity for their children with visual impairments. J. Visual Impair. Blind. 107, 131–142. doi: 10.1177/0145482X1310700206

Polit, D. F., and Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 47, 1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004

Powrie, B., Copley, J., Turpin, M., Ziviani, J., and Kolehmainen, N. (2020). The meaning of leisure to children and young people with significant physical disabilities: implications for optimising participation. Br. J. Occupat. Therapy 83, 67–77. doi: 10.1177/0308022619879077

Sandell, R. (2016). Museums, moralities and human rights. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315312095

Scott, D. (2005). Critical realism and empirical research methods in education. J. Phil. Educ. 39, 633–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2005.00460.x

Scottish Government (2010). Registered blind and partially sighted persons, Scotland 2010. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/registered-blind-partially-sighted-persons-scotland-2010/ (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Scottish Government (2013). See Hear: A strategic framework for meeting the needs of people with a sensory impairment in Scotland. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/see-hear-strategic-framework-meeting-needs-people-sensory-impairment-scotland/pages/3/ (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Scottish Government (2021). Pupil census 2021. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/ (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Scottish Government (2023). Achieving Excellence and Equity. 2023 National Improvement Framework and Improvement Plan. Scottish Government. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/achieving-excellence-equity-2023-national-improvement-framework-improvement-plan/ (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Štěrbová, D., and Kudláček, M. (2014). Deaf-blindness: Voices of mothers concerning leisure-time physical activity and coping with disability. Acta Gymnica 44, 193–201. doi: 10.5507/ag.2014.020

Thomas, D. R. (2017). Feedback from research participants: are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qual. Res. Psychol. 14, 23–41. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2016.1219435

Ullah, S., Hassan, F. U., and Muhammad, T. (2021). The role and strategies of non formal education for education access to marginalized community. Rev. Educ. Administ. Law 4, 563–573. doi: 10.47067/real.v4i3.172

UNESCO (1994). Salamanca Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (Accessed October 4, 2025).

UNICEF (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (Accessed October 4, 2025).

United Nations (2006). United Nationsconvention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Available online at: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd (Accessed October 4, 2025).

United Nations (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Vänskä, N., Sipari, S., and Haataja, L. (2020). What makes participation meaningful? Using photo-elicitation to interview children with disabilities. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 40, 595–609. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2020.1736234

World Health Organisation (2019). World report on vision. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-vision (Accessed October 4, 2025).

World Health Organisation (2021). World report on hearing. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/highlighting-priorities-for-ear-and-hearing-care (Accessed October 4, 2025).

Keywords: sensory loss, non-formal education, inclusive practice, children and young people, parents/carers, professionals/volunteers, deafness, visual impairment

Citation: Hannah EFS (2025) Inclusion of children with sensory loss in non-formal education settings: understanding and addressing some of the challenges and tensions in one local authority in Scotland. Front. Educ. 10:1655269. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1655269

Received: 27 June 2025; Accepted: 25 September 2025;

Published: 20 October 2025.

Edited by:

Jessica Norberto Rocha, Fundação CECIERJ, BrazilReviewed by:

Nevine Nizar Zakaria, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg, GermanyClaire Manford, Anglia Ruskin University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Hannah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah, ZS5oYW5uYWhAZHVuZGVlLmFjLnVr

Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah

Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah