- 1Pailan College of Education, Kolkata, India

- 2Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Institute of Education, Kolkata, India

- 3Postgraduate Department of Education, Saint Xavier's College, Kolkata, India

This study examined Indian school educators' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward augmented reality applications (ARA), focusing on their interrelationships and the factors influencing these variables at the school level. Employing a descriptive mixed-methods approach, data were randomly collected from 730 teachers across all 28 states and 8 union territories of India using standardized, self-developed questionnaires. Quantitative analysis included percentages, chi-square, t-tests, ANOVA, multiple correlations, and coding techniques. The findings revealed that teachers exhibited low to moderate levels of perception, attitude, and behavior toward ARAs, with female teachers scoring significantly higher than their male counterparts. Notable differences were observed across school category, stream, qualification, and designation, though attitudes showed no significant variation. In contrast, age, location, and teaching experience had little to no impact. Strong positive correlations were identified among the three variables—perception and attitude, perception and behavior, and attitude and behavior—underscoring their interdependence. Qualitative insights further highlighted key barriers, including limited awareness, low motivation, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficient training. Despite these challenges, teachers demonstrated resilience by adopting adaptive strategies. The study suggests that effective integration of AR in schools requires robust administrative support, adequate funding, targeted professional development, collaborative practices, and the development of culturally relevant, discipline-specific content.

1 Introduction

Technology has become our constant companion, like a shadow that never leaves us. It is becoming almost impossible to separate it from our lives. Just as we can't imagine doing anything without it, we can't even think beyond it anymore. In fact, there is hardly any aspect of our day-to-day life where we can move forward without relying on technology. In the field of education, technology truly serves as a powerful catalyst for enhancing it in a variety of ways, providing unique opportunities for individuals to learn and collaborate. It is essential for teachers to harness their technological capabilities to improve classroom teaching and learning processes (Alam and Mohanty, 2023).

In today's world, smartphones, mobile gadgets, and other digital devices have become increasingly popular among students. The integration of these technologies into education can be traced back to the late 1950s. One of the earliest examples is the Sensorama (2024), a simulator developed by Morton Heilig in 1957. In 1966, Ivan Sutherland created the first augmented reality (AR) headset, known as the “Sword of Damocles,” which was designed to assist helicopter pilots with night landings by allowing cameras to track head movements (The Sword of Damocles (virtual reality), 2024). Later, in 1999, Hirokazu Kato of the Nara Institute of Science and Technology developed ARToolKit (Best 3 ARToolKit Alternatives for 2024, 2024), the first cross-platform open-source library for augmented reality (Arena et al., 2022). As the use of electronic devices continues to grow among students and educators, it becomes increasingly important for teachers to be innovative in their teaching methods. By integrating technology into their teaching strategies, educators can create a more engaging and enjoyable learning experience for their students (Panakaje et al., 2024). Incorporating technology into education is not a novel concept, especially within the context of 21st-century teaching and learning.

Augmented reality (AR) is one such technological innovation that is currently being used to enhance the learning and teaching process, thereby strengthening concept formation and understanding. AR enriches real-world settings by overlaying virtual objects or information such as audio, video, graphics, or simulations created by computer-based technologies (Dunleavy et al., 2009; Thangavel et al., 2025). Essentially, AR enhances perceptions of reality by integrating two- and three-dimensional digital content into real-world environments (Cepeda-Galvis et al., 2017; Crogman et al., 2025). AR can engage multiple sensory modalities, including visual, auditory, haptic, somatosensory, and olfactory experiences. This multi-sensory approach effectively complements traditional teaching methods, fostering critical thinking and enhancing student engagement and perception (Cipresso et al., 2011; Syahputri, 2019; Toyama and Hori, 2025).

According to Paladini (2018) and Singh (2025), there are currently three main types of AR used in education: marker-based AR, which requires target images or markers to annotate objects in a given space, using phone camera feeds to place 3D digital content within the user's visual field; marker-less AR, which does not require object tracking systems but instead uses advancements in cameras, algorithms, sensors, and processors to detect and map the real world; and location-based AR, which merges virtual 3D objects into the user's physical location, overlaying information based on geographical data. These AR technologies are increasingly employed in educational and training settings to facilitate interaction with both virtual and real-time applications (Zuo et al., 2024). They offer dynamic representations of complex concepts across various disciplines, such as arts, science, social science, and mathematics, thereby enhancing students' understanding.

However, the application of AR extends across multiple subjects, including English language education, foreign languages, science, social studies, history, mathematics, special education, and vocational training. AR is also utilized in higher education research, creating realistic simulations that allow students to practice skills and concepts in safe, controlled environments (Egunjobi and Adeyeye, 2024). Recent technological advancements have significantly altered the educational landscape, integrating innovative tools like AR into traditional learning environments. AR blends virtual elements with real-world settings, primarily through mobile devices, tablets, and other appropriate tools, offering immersive educational opportunities that encourage interaction with virtual counterparts of physical environments (Pasalidou et al., 2023). These advancements play a significant role in increasing students' motivation and engagement (Khan et al., 2019; Zuo et al., 2025). AR, which not only incorporates digital information into live footage of a user's real-life environment, provides several potential benefits as well, such as enhancing understanding of our surroundings, building contextual awareness, and scaffolding learners' live experiences (Wu et al., 2013).

The benefits of AR in education are numerous, including improved access to learning materials, the availability of virtual equipment, higher student engagement, faster and more authentic learning experiences, safer practice environments, increased motivation and attention in classes, the development of imagination, creativity, and abstract thinking, and the ability to teach complex concepts that are challenging to present in a traditional classroom setting. Despite these potential benefits, the successful integration of AR into schools depends largely on the actions and behaviors of teachers. Educators play a crucial role in applying new technologies in classrooms, which directly influence students' engagement and learning outcomes. Therefore, understanding teachers' attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors toward AR applications in educational practices is essential.

A positive attitude, perception, and behavior toward AR are influenced by factors such as perceived enjoyment, perceived ease of use, and the relative merit of AR over traditional teaching methods. Teachers with a positive attitude toward AR are more likely to experiment with and integrate it into their pedagogical practices. Research has shown that AR technology can enhance teaching and learning outcomes in areas such as achievement, attitude, confidence, motivation, interest, engagement, and overall student satisfaction (Akcayır and Akcayır, 2017; Weng et al., 2020). The relationship among perception, attitude, and behavior is cyclical: perception influences attitude, which in turn impacts behavior. For example, if teachers perceive AR as user-friendly and pedagogically valuable, they are likely to develop a positive attitude, leading to increased use of AR in their teaching. This behavior can reinforce positive perceptions and attitudes, creating a feedback loop that promotes the continued use of AR in education. In this context, research revealed that teachers can be compared to expedition leaders, guiding students on a journey of discovery that expands their understanding of the world and prepares them to become knowledgeable, curious, and empathetic global citizens (AlGerafi et al., 2023). AR facilitates discovery and self-exploratory learning, making the educational experience both engaging and enjoyable.

1.1 Review of literature

Research on teachers' perceptions of mobile augmented reality (MAR) consistently highlights generally positive attitudes and a readiness to integrate this technology into educational practices. Studies indicate that educational mobile AR apps can significantly enhance teaching performance, effectiveness, and productivity (Pasalidou and Fachantidis, 2021). Teachers, particularly those in biology and language education, view MAR as a tool that makes their teaching more engaging and interesting (Ashley-Welbeck and Vlachopoulos, 2020; Schmidthaler et al., 2023). This positive perception extends to various applications, including interactive, experiential, and authentic learning, as well as the visualization of complex concepts (Perifanou et al., 2023). However, challenges such as technological errors, global positioning system (GPS) issues, software lags, and students' unfamiliarity with AR can hinder its effective use (Mundy et al., 2019; Youm et al., 2024). Despite these challenges, teachers generally feel knowledgeable about AR technology and are willing to learn more to better integrate it into their classrooms (Dsouza and Hemmige, 2023; Mohamad and Husnin, 2023).

Factors such as perceived usefulness, attitude, and behavioral intention significantly influence AR adoption, while perceived ease of use plays a moderate role (Ibili et al., 2019; Salmee and Majid, 2022). Notably, gender and geographical disparities exist, with female and urban teachers displaying more positive attitudes toward AR compared to their male and rural counterparts (Castaño-Calle et al., 2022; Putiorn et al., 2018). Teachers also express concerns about institutional support, teacher training, and the availability of AR educational applications, yet remain hopeful about the technology's potential to bridge gaps between learners and educators and enhance student motivation (Manna, 2023). Overall, teachers are enthusiastic about AR's potential, particularly with adequate training and resources, and are eager to implement it in their curricula (Alkhabra et al., 2023; Jamrus and Razali, 2021).

The assessment of teachers' attitudes toward MAR applications at the school level reveals diverse findings across various studies. A strong positive correlation between ease of use and positive attitudes toward AR in teaching at different educational stages was observed (Asiri and El-aasar, 2022; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2019b), although no such correlation was found between attitudes toward AR and science and technology (Kececi et al., 2021). Meanwhile, Wyss and Bäuerlein (2024) demonstrated that teachers had high motivation and a strong link between positive attitudes toward AR and technology acceptance. Future teachers, particularly those in pre-service education, developed favorable attitudes toward AR, contributing to deeper learning (Hervás-Gómez et al., 2017; Meccawy, 2023). In higher education, faculty members generally displayed positive attitudes toward AR, influenced by factors like crisis response (Alqahtani, 2023; Kamarudin et al., 2023). The impact of teaching experience on AR attitudes varied, with some studies showing positive effects (Amores-Valencia et al., 2023; Banerjee and Walunj, 2019; Koutromanos and Jimoyiannis, 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Rahmat et al., 2023; Romano et al., 2020), while others found no significant impact (Al-Shahrani and Asiri, 2023b; Mundy et al., 2019). Both teachers and students exhibited high positive attitudes toward using AR in biology lessons, leading to enhanced attitudes toward science (Berame et al., 2022; Lham et al., 2020).

However, despite moderate readiness, teachers with limited IT experience showed low attitudes toward AR in teaching Arabic (Asbulah et al., 2022). Positive correlations between attitudes and acceptance were also noted in chemistry teaching (Ripsam and Nerdel, 2024), though the influence of interface style and ease of use on enjoyment was weak (Wojciechowski and Cellary, 2013). Student attitudes toward AR were generally positive, particularly in science and technology subjects (Al-Anazi and Khalaf, 2023; Alqarni, 2021; Kamarainen et al., 2013; Sahin and Yilmaz, 2020; Sirakaya and Cakmak, 2018; Stojsic et al., 2022), although some studies reported negative attitudes at the university level and no significant impact on laboratory skills (Akçayir et al., 2016; Cao and Yu, 2023). Overall, AR applications were found to improve students' academic achievement, motivation, spatial thinking, creativity, and attitudes toward science lessons (Cetin, 2022; Ibáñez et al., 2020; Sökmen et al., 2024).

Correspondingly, the exploration of teachers' behavior toward MAR applications at the school level reveals a wide range of insights across several studies. Research has consistently shown that MAR significantly impacts knowledge acquisition and behavioral changes among teachers (Chang et al., 2014; Do et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2013). Several studies have also highlighted that factors such as attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral control play a critical role in influencing the use of MAR in both research and higher secondary education (Buchner et al., 2022; Cheon et al., 2012; Marín-Marín et al., 2023; Vaida and Pongracz, 2022). Abdelmagid et al. (2021) found that both teachers and students acknowledged the purposefulness and potential of AR in education. Additionally, Georgiou and Kyza (2017) demonstrated that AR not only enhances cognitive processes such as information collection, but it also works on problem-solving.

However, Wijnen et al. (2023) pointed out challenges in identifying the specific effects of MAR on teachers' higher-order thought processes. Ozdamli and Hursen (2017) noted that while AR applications might encounter barriers due to international connections, both teachers and students were generally satisfied with AR-guided teaching. Further research has established that AR applications can significantly improve the learning of challenging topics, foster exploitative behavior, and enhance perceived utility and positive attitudes, providing valuable insights for policymakers (Alalwan et al., 2020; Alzahrani, 2020; Mena et al., 2023).

The study of the relationship among perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward MAR applications offers varied insights from numerous studies. Prospective teachers generally had positive perceptions of AR technology, with their acceptance of this technology significantly increasing after hands-on experience (Jiang et al., 2025; Jung and tom-Dieck, 2018; Karthick and Shanmugam, 2024; Okumuş and Savaş, 2024). However, no significant difference or correlation was found in their self-efficacy, attitudes, or performance when using AR technology (Elford et al., 2022). Other studies (Cai et al., 2013; Giard and Guitton, 2016; Milad and Fayez, 2025) highlighted differing attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions among students and teachers regarding mobile device usage, with AR tools serving as complementary learning aids, proving effective across a range of student performance levels.

The comparison between male and female school teachers' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward MAR applications shows largely positive attitudes across both groups. Studies (Kudale and Buktar, 2022; Tiede et al., 2022) indicate that most teachers are favorable toward using AR in the teaching–learning process, with only a few expressing negative views. Nikou (2024) found that teachers' perceptions of educational AR apps were strongly linked to their views on the apps' usefulness, with perceived usefulness and ease of use being key factors influencing the intention to adopt MAR (Papakostas et al., 2022). Ghobadi et al. (2023) reported no significant differences between male and female teachers, as both groups exhibited positive attitudes and behaviors toward AR. Kazakou and Koutromanos (2022), and McNair and Green (2016) highlighted that teachers had positive perceptions of AR, especially in online and distance learning settings. In science education, smartphone applications and marker-based content were the most popular AR tools among both genders (Arici et al., 2021; Atalay, 2022). However, Dirin et al. (2019) observed that female teachers had a more favorable perception of AR, noting its role in enhancing enjoyment and memorability in the classroom.

1.2 Rationale of the study

The integration of augmented reality (AR) technology into educational practices offers transformative potential in enhancing the teaching–learning process. In the context of Indian education, where traditional methods still dominate, the adoption of innovative technologies like mobile augmented reality (MAR) presents both opportunities and challenges (Kumari and Polke, 2019; Mirza et al., 2025; Thangavel et al., 2025). The present study is motivated by the need to understand how Indian school teachers perceive, approach, and behave toward AR applications within the classroom setting. Previous studies have highlighted the generally positive attitudes of teachers worldwide toward augmented reality applications (ARA), recognizing its ability to make learning more engaging, interactive, and effective. However, they have also uncovered challenges such as technological limitations, lack of familiarity, level of interest, and the need for institutional support, which can hinder the full adoption of AR.

In India, the government through the National Institute of Electronics and Information Technology (NIELIT) under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, has initiated programs to build capacity in AR technologies. These initiatives focus primarily on skill development rather than mandating AR integration in schools. Similarly according to Government of India, Ministry of Education (2020) the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 highlights the integration of technology in education, explicitly acknowledging the role of AR/VR and other immersive technologies in promoting innovative, engaging, and experiential learning. However, despite these references, no comprehensive legislation exists that requires the use of AR across all schools in the country. India's educational landscape is marked by considerable diversity arising from socio-economic disparities, the urban–rural divide, differences between government and private institutions, variations across states, multiple curriculum boards and mediums of instruction, unequal technological infrastructure, and inconsistent opportunities for teacher training and professional development (Shivani and Chander, 2023). These contextual factors directly shape teachers' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward adopting AR applications in different school subjects, making them highly relevant to the present study. Accordingly, the rationale for this research lies in addressing the existing gap in the literature by examining how Indian educators, particularly at the secondary and higher secondary levels, perceive and engage with AR technology, and what factors influence their readiness for its integration into school education.

As India continues to push for digital transformation in education, it is essential to assess whether teachers, the key facilitators of learning, are ready to embrace this change. Consequently, this study seeks to explore how Indian teachers perceive the usefulness, ease of use, and overall impact of AR applications on their teaching practices and students' learning experiences. By examining attitudes, the study seeks to determine the level of enthusiasm or resistance among teachers toward incorporating AR in their curricula (Palada et al., 2024). Understanding teachers' behaviors toward AR—whether they are actively using it, reluctant to adopt it, or somewhere in between—will provide insights into the practical challenges they face and the support they require. Similarly, a critical aspect of this research is the comparison between male and female teachers' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward AR applications. Gender disparities in the adoption of educational technologies have been noted in various studies, and this research contributes to understanding whether such differences exist in the Indian context and what factors might influence them. Additionally, the study explores the relationship among teachers' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward AR, offering a comprehensive view of how these elements interact and shape teachers' willingness to integrate AR into their teaching. By investigating these factors, the study aims to identify the key enablers and barriers to AR adoption in Indian schools. Finally, the research will examine the broader factors influencing teachers' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors, including technological readiness, professional development opportunities, and institutional support.

The novelty of this study lies not only in its distinction from existing research but also in its emphasis on the contextual uniqueness of AR within the Indian school education system. It captures the realities shaped by the diverse socio-economic backgrounds of teachers and learners, persistent digital infrastructure gaps, policy-driven initiatives such as NEP 2020, and varied teaching practices—factors that global studies often fail to address in depth. Furthermore, the study highlights a teacher-centric perspective, focusing on educators' readiness, acceptance, and willingness to integrate AR into their pedagogy. By exploring their perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors, this research fills a critical gap between the technological potential of AR and its practical implementation in classroom realities. The findings from this study would not only provide valuable insights into the current state of AR adoption in Indian schools but also offer recommendations for policymakers, educational leaders, and technology developers on how to better support teachers in embracing AR. This research is timely and significant as it addresses the need for evidence-based strategies to enhance the integration of innovative technologies in Indian education, ultimately contributing to improved educational outcomes and a more future-ready learning environment.

1.3 Statement of the study

The study titled “Exploring Indian Educators' Perception, Attitude, and Behavior Regarding augmented reality Applications in School Settings: A Comprehensive Mixed-Methods Study” aims to investigate the research problem. The goal of this research is to comprehend Indian educators' attitudes, behaviors, and thoughts on the use of augmented reality (AR) in the classroom. Utilizing gadgets like smartphones or AR glasses, augmented reality technology incorporates digital components, such as sounds or images, into the physical world. The study examines key issues, such as instructors' opinions of augmented reality. Do they think it is helpful or not? What do they think of implementing augmented reality in the classroom? Are they apprehensive, intrigued, or perhaps thrilled? In what ways do they employ augmented reality in their teaching? Are they using it frequently, infrequently, or never? The study also looks at whether male and female instructors have different ideas, emotions, and behaviors in this regard, as well as what aspects of the school may have an impact on how they use AR. A variety of techniques are used in the research to obtain a complete picture of the circumstances.

1.4 Objectives

1. To study Indian teachers' perceptions of augmented reality applications at the school level.

2. To assess Indian teachers' attitudes toward augmented reality applications at the school level.

3. To investigate Indian teachers' overall behavior toward augmented reality applications at the school level.

4. To explore the relationship among perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of Indian school teachers toward augmented reality applications.

5. To examine the factors influencing the perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of Indian school teachers toward augmented reality applications at the school level.

1.5 Hypotheses

H1: There would be a significant level of perception among teachers on augmented reality applications at the school level.

H2: A significant level of attitudes would be observed among teachers on augmented reality applications at the school level.

H3: There would be a significant level of practices in terms of behavior among educators toward augmented reality applications at the school level.

H4: A significant level of relationship among perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors would be found among educators toward augmented reality applications.

H5: Multiple factors would be observed affecting the perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of Indian school teachers toward augmented reality applications at the school level.

1.6 Research questions

1. What are the key factors that influence Indian school teachers' perceptions of augmented reality applications in educational settings?

2. How do various demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, and teaching experience) influence teachers' attitudes toward the use of augmented reality in schools?

3. In what ways do school-level factors (e.g., availability of resources, administrative support, and training opportunities) affect teachers' behaviors in implementing augmented reality in their teaching practices?

4. Are there any external factors (e.g., curriculum requirements, peer influence, and student engagement) that significantly impact the adoption of augmented reality by Indian school teachers?

2 Methodology

2.1 Design

Researchers used a descriptive mixed-methods strategy for this investigation. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the study subject, this approach integrates qualitative and quantitative research approaches. With regard to this hybrid methodology, the study aims to emphasize the benefits of qualitative and quantitative data by offering a more thorough and nuanced perspective than could be acquired from either technique alone. The quantitative component involves gathering and analyzing numerical data to identify patterns, trends, and correlations. This information provides a thorough summary of the research issue and enables the extrapolation of research findings to a larger population (Creswell and Clark, 2023; Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). The qualitative component, on the other hand, focuses on gathering detailed narrative data that sheds light on the underlying attitudes, beliefs, and intentions that underlie the observed trends. Closed-ended surveys and interview methods that enable a detailed analysis of participants' experiences and points of view are used to achieve this. The integration of these two approaches into a descriptive mixed-methods design facilitates data triangulation, hence enhancing the validity and coherence of the study's findings (Creswell and Clark, 2017; Dejonckheere et al., 2019). According to Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004), this type of design provides a thorough, complex, and varied understanding that informs recommendations and findings, ensuring that the study covers the full breadth and depth of the research topic.

2.2 Sample

In this study, a comprehensive multi-stage sampling process was employed to include teachers from both urban and rural schools across India (Figure 1). The procedure began with random sampling to capture geographical diversity, ensuring participation from all 28 states and 8 union territories. This was followed by the selection of 10% of districts within each region through stratified sampling, which secured a balanced representation of both larger and smaller regions and minimized the risk of over- or under-representation (Makwana et al., 2023; Tipton, 2013). Within the selected districts, schools were chosen using simple random sampling, a method that reduced selection bias and allowed for the inclusion of institutions of varying sizes, resources, and management types. By incorporating randomization at each stage, bias in participant selection was effectively controlled. As a result of this process, 531 urban school teachers participated in the study, contributing through both online platforms (email, WhatsApp) and offline methods (pen-and-paper surveys). In addition, 199 rural school teachers participated primarily through pen-and-paper surveys, with some responses collected online via social media texts. This brought the total sample size to 730 teachers. To complement the survey data, 88 semi-structured interviews were conducted in both online and offline modes, involving 31 male and 57 female teachers. Conducting interviews according to the participants' convenience ensured inclusivity and enriched the study with diverse perspectives from educators across urban and rural contexts.

2.3 Tools

In this research, we developed standardized, self-designed questionnaires to gather data, comprising 60 closed-ended items (20 per variable) and four open-ended items. These instruments were designed to assess educators' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors concerning the use of augmented reality (AR) applications in school settings. The perception assessment included 20 multiple-choice questions, each with four response options, awarding 5 marks for correct answers and 0 marks for incorrect ones (Scharf and Baldwin, 2007; Yaneva et al., 2022). To identify the most significant attitudes and behaviors toward AR applications, two sets of 20 statements were used, based on a five-point Likert scale. The first set ranged from Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Undecided (UD), Disagree (D), to Strongly Disagree (SD), while the second set ranged from Always (A), Often (OF), Occasionally (OC), Rarely (R), to Never (N). Educators selected their responses by circling one of the five options. For positive statements, the responses were scored as 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively, while for negative statements, the scoring was reversed: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (Alhassn et al., 2022; Joshi et al., 2015; Tanujaya et al., 2022).

Additionally, four open-ended interview questions were designed to delve deeper into educators' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors regarding AR applications. These questions were intended to encourage participants to express their views freely, providing richer and more detailed responses that go beyond surface-level opinions. In this connection, the interviews were conducted with 2 to 3 participants from each of the 28 states and 8 union territories, either online or offline, at their convenience. Each session lasted between 20 and 30 min.

A total of 60 min was allotted to administer all three sets of questionnaires, each consisting of 20 items, making 60 items in total, and this was clearly stated in the instructions. The total scores for perceptions ranged from 0 to 100, while the scores for attitudes and behaviors ranged from 20 to 100. These were categorized into five levels—very high, high, moderate, low, and very low—each approximately divided into equal intervals using the stratification method employed by Ascher-Svanum et al. (2013) and Naveau et al. (2016).

To gain insights into the research questions, various open-ended questions were posed to teachers through semi-structured interviews. The primary emphasis was placed on four key questions that aligned with the core objectives of the study. Both in-person and online interview methods were employed to ensure wider participation, covering all 28 states and 8 Union Territories of India, with a minimum of two to three participants from each region. A total of 88 teachers participated in the interviews, consisting of 31 males and 57 females. The participants were selected based on their willingness to contribute and represented diverse academic streams, geographic locations, and types of schools. While some interviews were conducted face-to-face, others were facilitated online through invitations sent via email. Each interview, whether conducted in person or virtually, lasted between 20 and 30 min.

To standardize the questionnaires, a thorough validation process was undertaken, emphasizing content and face validity, with the involvement of nine field experts. Beyond content and face validity, the instrument was subjected to a test–retest procedure to establish its reliability. For this purpose, the questionnaires were administered twice to a sample of 30 participants to assess the consistency of responses over time. The Kuder-Richardson reliability coefficient for perceptions was calculated at 0.79, appropriate due to the dichotomous nature of the responses, where each question had only two possible answers: either correct or incorrect, scored as 0 and 5, respectively. Similarly, Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the reliability for attitudes and behaviors, yielding coefficients of 0.78 and 0.84, respectively, reflecting the internal consistency of responses on a standardized 1 to 5 scale (Garratt et al., 2011; Wadkar et al., 2016).

2.4 Procedure of data collection

The data collection process for this study involved distributing survey questionnaires to educators from various private and government (public) schools across India, regardless of age, gender, qualifications, or the educational boards of their institutions. These schools and institutes were situated in rural and urban areas of India. To ensure a diverse and representative sample of teachers, we employed both physical and digital communication methods. For the physical distribution, we conducted one-on-one sessions with participants, followed by sending the survey questionnaires via email and WhatsApp. This approach ensured efficient and widespread distribution of the survey tools. Before administering the questionnaires, we provided detailed information to all potential participants regarding the survey's nature, the study's purpose, and the time required to complete the questionnaire. This information was crucial to ensure that participants were well-informed and could make an informed decision about their participation. For online data collection, we utilized Google Forms, a convenient platform for gathering and organizing responses (Bhalerao, 2015; Hsu and Wang, 2017). Similarly, participants were given clear instructions and a timeline for submission, which helped facilitate timely and accurate data collection (Belisario et al., 2015; Rayhan et al., 2013). By the conclusion of the data collection period, we had received a total of 730 responses: 237 from male and 493 from female participants, with 531 responses from urban areas and 199 from rural areas. To explore the research questions, semi-structured interviews with open-ended items were conducted both in-person and online, involving 88 teachers (31 males, 57 females) from diverse regions, schools, and academic streams across India. Each 20–30 min session ensured broad representation and meaningful insights aligned with the study's objectives.

In analyzing the responses, we identified a noticeable gap based on gender and location, possibly influenced by the combination of online and offline data collection methods (Contreras et al., 2024; Sethuraman et al., 2005). Throughout the process, we placed significant emphasis on obtaining informed consent from all participants, reflecting our ethical commitment. Instead of seeking formal ethical approval from an institutional review board, we focused on securing explicit consent from each participant. This ensured that all participants voluntarily agreed to participate, fully understanding their rights and the nature of their involvement. This approach underscored the researchers' dedication to maintaining ethical standards and respecting participants' autonomy.

The collected dataset comprises both categorical and continuous variables. To assess the normality of the continuous data, the Shapiro–Wilk Test was employed. The Shapiro–Wilk test showed a significant departure from normality, W(730) = 0.97, p < 0.001. Although the result indicated that the data were not normally distributed, a combination of statistical tests was applied to analyze the dataset appropriately.

Given the mixed nature of the variables, chi-square (χ2) tests were used for categorical data analysis, while t-tests and F-tests were employed to compare means across groups. Additionally, correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among continuous variables (Bandla et al., 2024; Lee and Lee, 2022; Shapiro and Wilk, 1965). Similarly, the open-ended responses were analyzed using a qualitative research method known as thematic analysis, which helped in identifying and interpreting key themes across the data (Turhan et al., 2022).

3 Result and analysis

3.1 Hypothesis 1

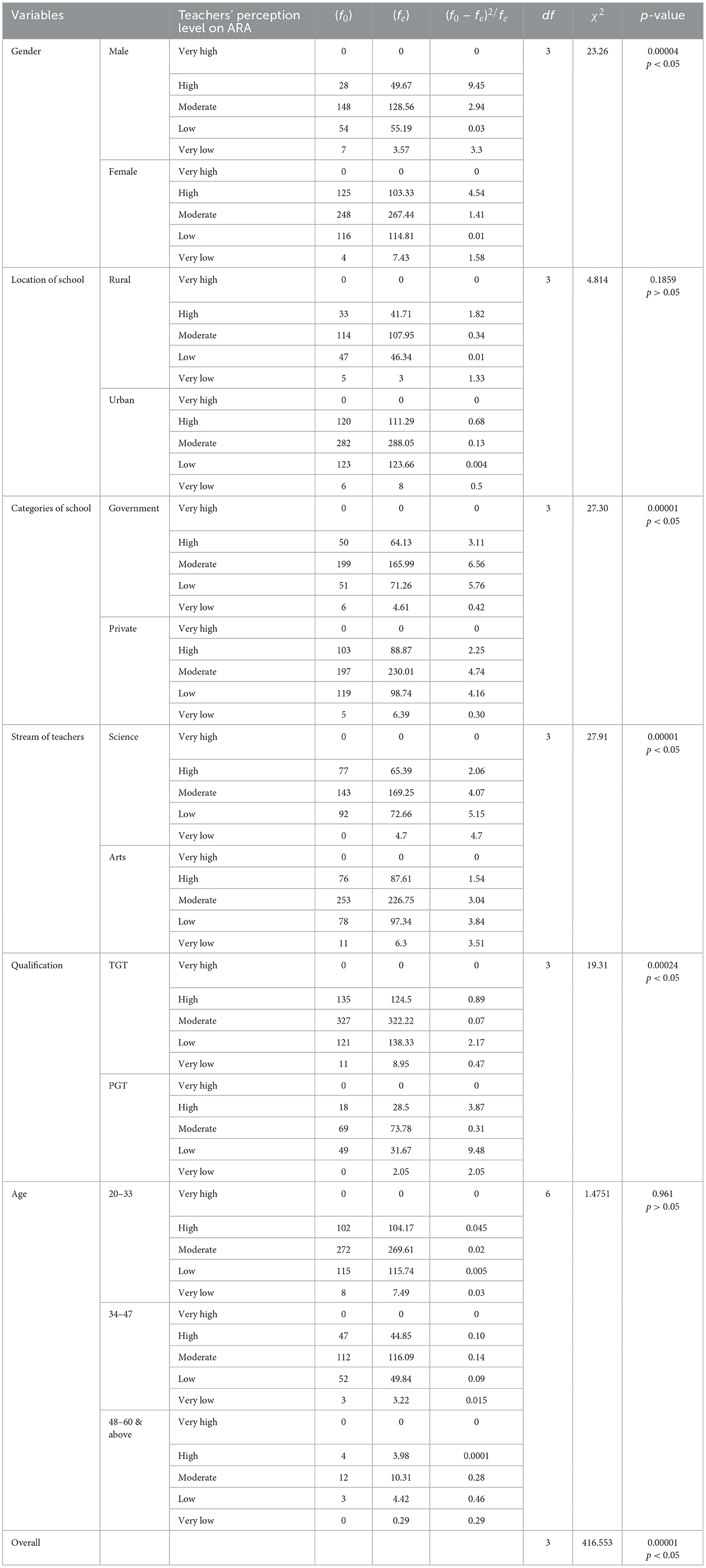

The result of Hypothesis 1 examined the significance of teachers' perceptions of augmented reality applications (ARA) at the school level. This was done by analyzing the range, frequencies, and percentages of respondents based on their gain scores. Additionally, the hypothesis examined the significant differences in the levels of perception and the variables associated with teachers' views on augmented reality applications. These differences were analyzed using the chi-square test and t-test, based on the respondents' gain scores.

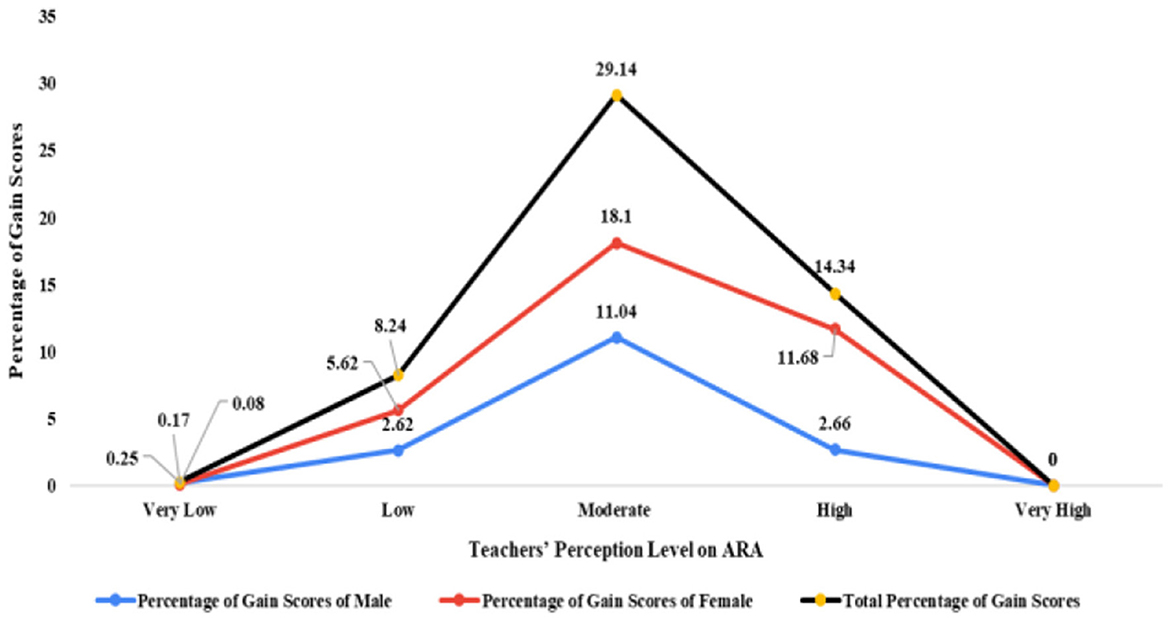

Table 1 represents the distribution of teachers' perception scores regarding the use of augmented reality applications (ARA) at the school level. The findings indicate that the majority of teachers fall within the moderate perception category. Specifically, 248 female and 148 male teachers scored between 41 and 60, resulting in gain scores of 8,055 and 13,215, respectively. This category accounts for a combined total of 29.14% of the overall gain scores. Additionally, 14.34% of teachers are categorized as having a high level of perception, with scores ranging from 61 to 80, including 125 female and 28 male teachers. Their corresponding gain scores are 1,940 and 8,525, respectively (Dirin et al., 2019; Habig, 2020). In contrast, a smaller proportion of teachers fall into the low category, contributing 8.24% to the total gain scores, with 116 females and 54 males scoring within the 21 to 40 range. Notably, a negligible number of teachers, just 0.25%, are found in the very low category, with scores ranging between 0 and 20. Importantly, no teachers scored within the very high category (scores ranging from 81 to 100), indicating the absence of exceptionally high perceptions. Overall, the data suggest that while a moderate to high level of perception toward the use of ARA exists among teachers, there remains significant scope for improvement. Efforts should focus on enhancing teachers' knowledge, awareness, and understanding of ARA to elevate perceptions into the higher categories and promote more effective integration of these technologies in educational settings (Alkhabra et al., 2023; Di-Fuccio et al., 2024).

The line graph (Figure 2) illustrates the percentage of gain scores of male and female teachers across five perception levels (very high, high, moderate, low, and very low) regarding augmented reality applications.

The results of the chi-square (χ2) tests are shown in Table 2, which shows significant differences in teachers' perceptions of ARA across different demographic variables, such as gender, school location, school category, teaching stream, qualification, and age group. In this analysis, the degrees of freedom for the chi-square test are reported as 3 instead of 4 because categories with zero frequency counts are excluded. In a contingency table, a row or column that contains all zero values contributes no variability to the dataset and is therefore excluded from the degrees of freedom calculation. Including such categories can distort the statistical result and result in incorrect conclusions. This approach is consistent with normal statistical standards, as endorsed by Bock et al. (2010) and Finkler (2010), who underlined the necessity of using only legitimate, non-zero data in chi-square computations.

Table 2. Significant differences regarding the level of perception on augmented reality applications (ARA) among the teachers, including observed frequency (f0), expected frequency (fe), difference (f0 − fe), difference Sq. (f0 − fe)2, Diff. Sq./Exp Fr. (f0 − fe)2/fe, degrees of freedom (df), chi-square (χ2), and p-value of gain scores regarding the level of perception of respondents on augmented reality applications.

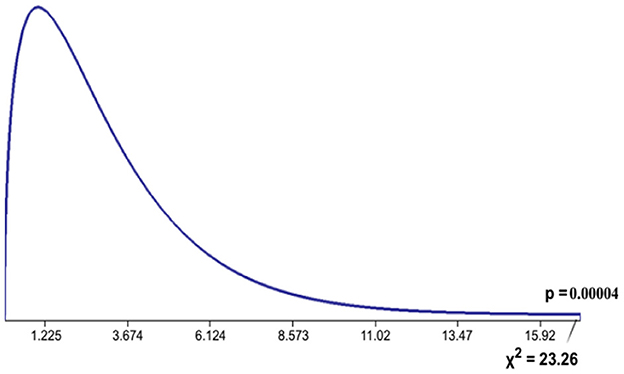

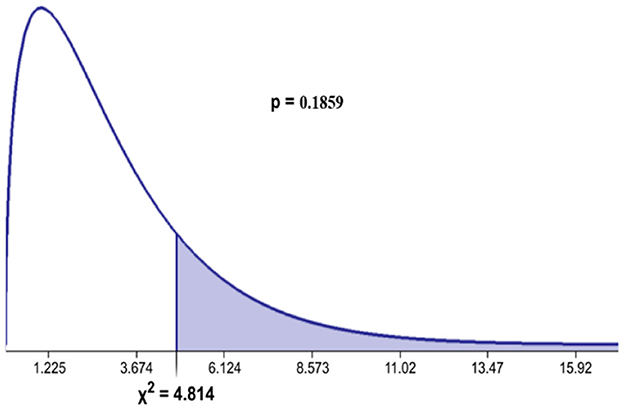

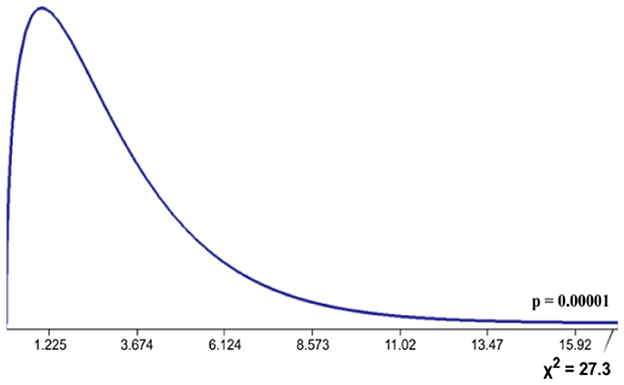

However, the chi-square test results not only indicate teachers' perception levels of augmented reality applications (ARA) vary significantly across most demographic variables, rather it also shows with that, the exception of school location and age, no significant differences are observed. For gender, a significant association is found (χ2 = 23.26, p < 0.05) with an effect size of Cramer's V = 0.25. The 95% confidence interval (0.16 to 0.33) indicates a small-to-moderate effect. This suggests that male and female teachers differ in their perception levels, with female teachers more likely to report “high” and “moderate” perceptions compared to their male counterparts. Similarly, for the categories of school (χ2 = 27.30, p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.11–0.25), a small yet significant association is observed. Government school teachers are more concentrated at the “moderate” level, whereas private school teachers display a wider distribution across the “high” and “low” categories. This indicates that the type of school plays a role in shaping teachers' perception levels, though the effect remains modest. In terms of the stream of teachers (χ2 = 27.91, p < 0.05), a significant difference is found between science and arts teachers. Science teachers are less represented in the “very low” and “high” categories, whereas arts teachers are more concentrated in the “moderate” and “very low” levels. The effect size (Cramer's V = 0.19) with 95% confidence intervals of 0.12–0.26 indicates a small-to-moderate effect, suggesting that the subject stream influences teachers' perception levels, though the strength of the association is modest. Likewise, qualification shows a significant association (χ2 = 19.31, p < 0.05). TGTs are predominantly concentrated in the “Moderate” category, while PGTs display greater variation, particularly with higher representation in the “low” perception level. The effect size (Cramer's V = 0.16) with 95% confidence intervals of 0.09–0.23 suggests a small but statistically meaningful effect, indicating that teachers' qualifications play a modest role in shaping their perception levels. In contrast, the location of the school (χ2 = 4.814, p > 0.05, effect size = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.00–0.14) and age groups (χ2 = 1.4751, p > 0.05, effect size = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.00–0.07) do not show significant differences, implying that teachers' perceptions of ARA remain fairly consistent irrespective of their school setting (rural/urban) or age group. The overall chi-square value (χ2 = 416.553, p < 0.05) along with a moderate effect size of 0.29 at 95% confidence intervals (0.26–0.34) reflects a robust association across categories. Hence, it confirms that, collectively, teachers' demographic variables significantly influence their perception levels toward ARA, with qualification, stream, type of school, and gender being the most decisive factors. Since the analysis reveals that teachers' perception of ARA is uneven across demographics, whereas age and location do not influence attitudes, factors like gender, qualification, school category, and stream significantly affect how teachers perceive ARA. Therefore, it clearly highlights the need for targeted interventions to ensure equitable adoption and integration of ARA in schools.

There is a gender-based variation that shows (Table 2 and Figure 3) a statistically significant difference in the level of perception (χ2 = 23.26, df = 3, p = 0.00004). Overall, male teachers exhibit marginally lower levels of perception compared to their female counterparts, particularly in terms of the number of instructors reporting high or extremely high perceptions. Higher and intermediate levels of perception are more commonly observed among female teachers. This suggests that perceptions of ARA are influenced by gender, with female teachers generally holding a more favorable view (Abdusselam and Karal, 2020; Uderbayeva et al., 2025).

The calculated result of teachers' perception levels on ARA across different school locations (rural vs. urban) reveals no statistically significant difference (χ2 = 4.814, df = 3, p = 0.1859), as the p-value exceeds the threshold of 0.05 (Table 2 and Figure 4). In rural schools, the observed frequencies for perception levels are slightly different from the expected values: 33 teachers describe high perceptions (expected = 41.71), 114 describe moderate (expected = 107.95), 47 state low (expected = 46.34), and 5 convey very low (expected = 3), while none describe very high perceptions. In urban schools, 120 teachers indicate high perception levels (expected = 111.29), 282 moderate (expected = 288.05), 123 low (expected = 123.66), and 6 very low (expected = 8); again, no teachers report very high perceptions. These minor deviations between observed and expected frequencies contribute to a relatively low chi-square value, indicating that the location of the school does not significantly influence teachers' perceptions of ARA (Al-Shahrani and Asiri, 2023a).

Teachers' perceptions of ARA are statistically significant (χ2 = 27.30, df = 3, p < 0.00001) according to the chi-square test, which examines the relationship between school category (private vs. government) and teachers' perceptions (Table 2 and Figure 5). There are no teachers who report extremely high perceptions among the teachers in government schools; 50 report high perceptions (anticipated = 64.13), 199 moderate (expected = 165.99), 51 low (expected = 71.26), and 6 very low (expected = 4.61). None of the instructors in private schools have very high perceptions, while 103 report high perceptions (expected = 88.87), 197 moderate perceptions (expected = 230.01), 119 low perceptions (expected = 98.74), and 5 very low perceptions (expected = 6.39). For both school types, there are notable differences, especially in the moderate and low categories. These findings imply that there are notable differences in the perceptions of ARA between government and private school teachers, with the former exhibiting comparatively higher views in some categories. This could be due to variations in exposure, resources, or institutional support for integrating technology (Akinradewo et al., 2025; Liao et al., 2024).

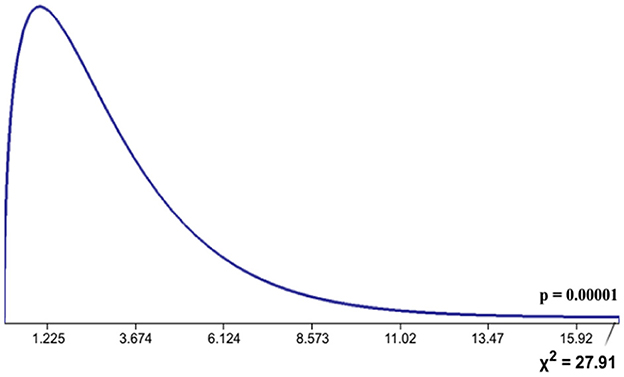

The chi-square test examines the relationship between teachers' perceptions of ARA and their academic streams, such as science and arts. It finds a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 27.91, df = 3, p < 0.00001), suggesting that perception is significantly influenced by the teaching stream (Table 2 and Figure 6). None of the teachers in the science stream indicate very high or very low perceptions (anticipated = 4.7), while 77 report high perceptions (expected = 65.39), 143 moderate perceptions (expected = 169.25), and 92 low perceptions (expected = 72.66). However, no teachers in the Arts stream indicate extremely high opinions; instead, they express 76 high (anticipated = 87.61), 253 intermediate (expected = 226.75), 78 low (expected = 97.34), and 11 very poor (expected = 6.3) perceptions. The overall chi-square value was influenced by significant deviations from expected frequencies, especially in the moderate and low categories (Ibáñez et al., 2020; Nikou et al., 2024a). According to these findings, teachers of the arts and sciences have different perspectives on ARA. These discrepancies may result from exposure to digital technologies in their various fields of education, subject-specific pedagogical techniques, or disparities in technological familiarity (Meng et al., 2024; Ventrella and Cotnam-Kappel, 2024).

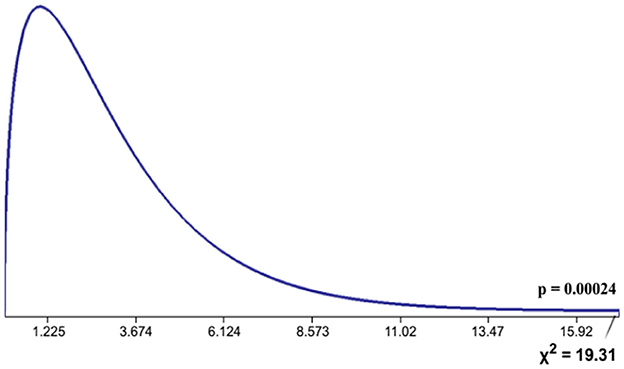

The chi-square test reveals a statistically significant result (χ2 = 19.31, df = 3, p = 0.00024), indicating that teachers' qualifications, such as trained graduate teachers (TGT) and postgraduate teachers (PGT), have a meaningful influence on their perception levels of ARA (Table 2 and Figure 7). Among TGTs, 135 report high perceptions (anticipated = 124.5), 327 moderate (expected = 322.22), 121 low (expected = 138.33), and 11 very low (expected = 8.95), while none express very high impressions. Among PGTs, 18 have high perceptions (expected = 28.5), 69 have moderate perceptions (anticipated = 73.78), 49 have low perceptions (expected = 31.67), and none have very high or very low perceptions (expected = 2.05). The most noticeable variances are found in the low perception group, where PGTs are overrepresented, and the high category, where TGTs outperform expectations. These data imply that TGTs typically have more positive impressions of ARA than PGTs, which could be due to differences in training emphasis, classroom responsibilities, or comfort with integrating modern technology (Alalwan et al., 2020; Uygur et al., 2018).

Teachers' perceptions of ARA and their age groups are compared using chi-square analysis. The results show no statistically significant difference (χ2 = 1.4751, df = 6, p = 0.961), since the p-value is significantly higher than the 0.05 threshold (Table 2 and Figure 8). The three age groups for teachers are 20–33, 34–47, and 48–60 years old and older. None of the age groups attest to a very high degree of perception. Within the 20–33 age range, there are only minor departures from expected frequencies: 102 instructors express high perceptions (expected = 104.17), 272 moderate (expected = 269.61), 115 low (expected = 115.74), and 8 extremely low (expected = 7.49). Similar trends are seen in the 34–47 and 48–60+ groups, with no significant differences between observed and expected counts across all perceptual levels. These data demonstrate that age has no significant influence on teachers' perceptions of ARA, indicating a reasonably consistent attitude regarding the use of augmented reality in education throughout age groups (Cyril et al., 2022; Nikou et al., 2024b; Schlomann et al., 2022), but it differed from the study of Castaño-Calle et al. (2022) due to the reasons of versatility, adaptability, and positive perception of AR.

Overall, according to conventional statistical criteria, the difference is highly significant (χ2 = 416.553, df = 3, p = 0.00001), indicating (Figure 9) a marked variation in teachers' perceptions of augmented reality (AR) applications at the school level, and the result is indeed similar to the study conducted by Sahin and Yilmaz (2020).

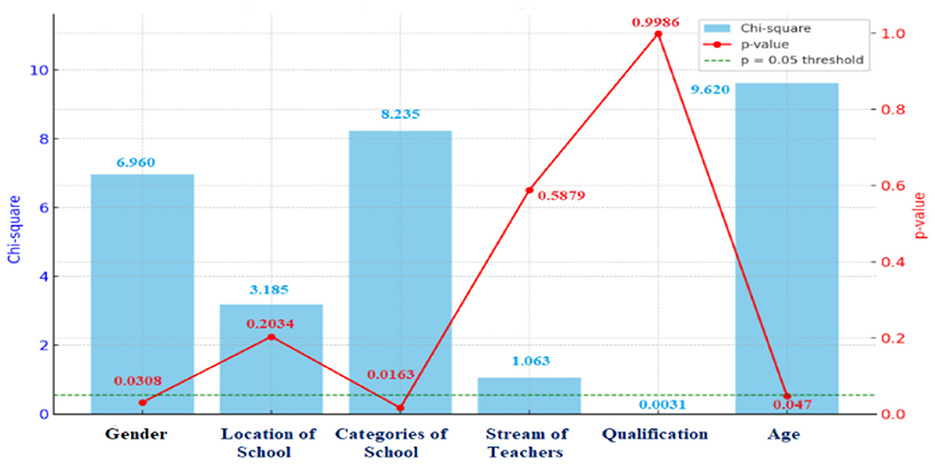

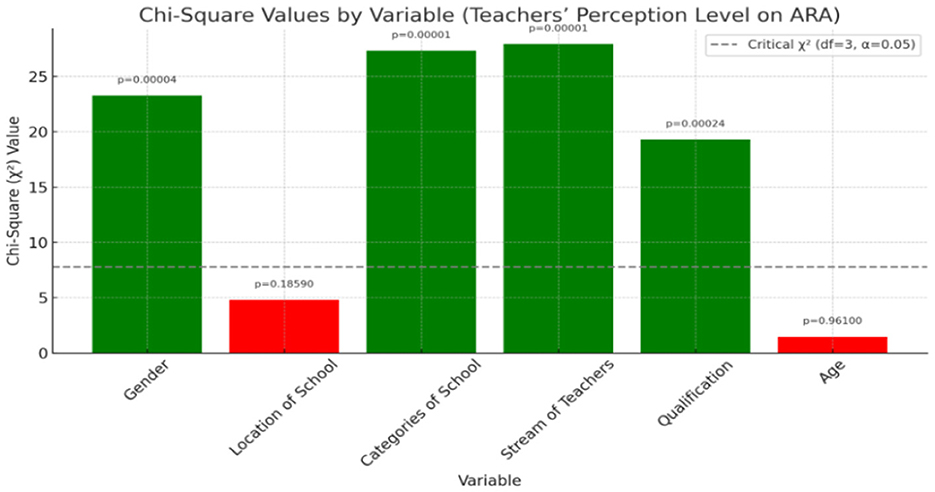

So far as Figure 10 is concerned, significant differences in perception are clearly observed based on individual variables such as gender, type of school, teaching stream, and academic qualifications, and these types of findings were also supported by Faqih and Jaradat (2021). In contrast, factors like geographical location and, particularly, age did not show a significant impact (Turan et al., 2018). These findings suggest that professional background and institutional context play a more influential role in shaping teachers' perceptions and engagement with AR in education than demographic factors like age or school location (Dahri et al., 2024).

Figure 10. Chi-square test of teachers' perception level on ARA across different demographic variables.

Table 3 demonstrates whether there are any significant changes in teachers' impressions of ARA depending on various background characteristics using t-tests. Here is a straightforward explanation for each variable along with graphs:

Table 3. Significant differences regarding the perception of teachers on augmented reality applications (ARA) in which t-tests were used to calculate the significant difference between the two groups (variables).

The sample consists of 237 male and 493 female teachers (Table 3). The mean perception score for male educators is 50.76 (SD1 = 12.67, SEM1 = 0.82), whereas female teachers have a slightly higher score of 52.54 (SD2 = 12.86, SEM2 = 0.58). The standard error of the difference (SED) is 1.012, with 728 degrees of freedom (df). The effect size is 0.14, and the 95% confidence interval ranges from 0.02 to 0.30, indicating a small effect. The computed t-value is 1.755, with a matching p-value of 0.079 (p > 0.05). Although female teachers have a slightly higher mean perception score, the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant at the traditional 0.05 level (Figure 11), demonstrating that gender has no meaningful influence on teachers' perceptions of ARA, and it does not play a major role in shaping perceptions of augmented reality in educational contexts (Nikou et al., 2024a; Qirom and Sukma, 2024).

There is a contrast in how rural and urban teachers see ARA (Table 3 and Figure 12). The average score for rural teachers is 51.18, while urban instructors score somewhat better at 52.25. However, the effect size (0.08) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.08 to 0.24 indicates only a marginal difference between the two groups, which is not statistically significant (t = 1.004, df = 728, p = 0.315, p > 0.05). This means that whether a teacher is from a rural or urban area does not make a meaningful difference in how they perceive the use of augmented reality in education (Salmee and Majid, 2022).

The test measures teachers' perceptions toward ARA in both government and private schools (Table 3 and Figure 13). Government school teachers have an average score of 52.24, but private school teachers have a slightly lower average of 51.76. However, this minor difference is not statistically significant (t = 0.501, df = 728, p > 0.05). The negligible effect size (0.04) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.12 to 0.20 further suggests that the type of organization, whether government or private, has no meaningful influence on teachers' attitudes toward the use of augmented reality in education (Bhattacharya et al., 2025; Wyss et al., 2022).

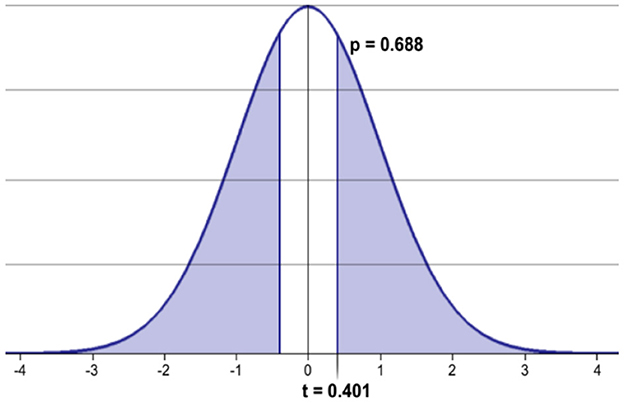

Teachers in the arts and science streams' opinions of ARA are displayed in Table 3. The average score for science educators is slightly higher (52.18) than that of art teachers (51.79). At t = 0.401, df = 728, p > 0.05, the observed difference is negligible, with an effect size of 0.03 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.13 to 0.19, indicating no statistical significance (Figure 14). This indicates that a teacher's perception of the employment of augmented reality in the classroom is not much influenced by their academic background, whether it be in the arts or sciences (Almaleki, 2022; Grinshkun et al., 2021).

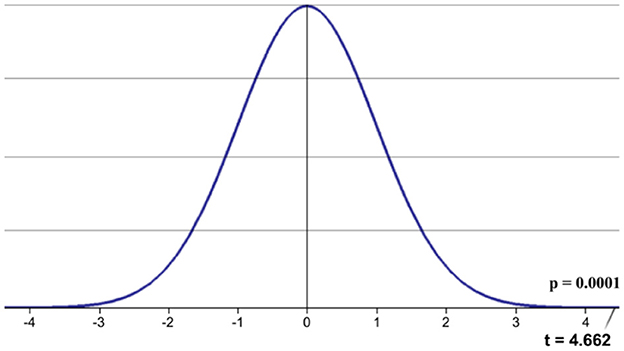

Table 3 indicates that trained graduate teachers' (TGTs') and postgraduate teachers' (PGTs') perceptions of ARA differ significantly. With an average score of 52.93, PGTs scored higher than TGTs, who had a lower average score of 47.07. The effect size of 0.52 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.30 to 0.73 indicates a moderate effect. This difference is statistically significant (t = 4.662, df = 728, p = 0.0001, p < 0.05, 0.01), making it highly unlikely to have occurred by chance (Figure 15). Therefore, designation plays an important role, with PGTs demonstrating noticeably more favorable perceptions of augmented reality in the classroom compared to TGTs (Al-Akloby, 2023).

The perspectives of teachers with varying degrees of experience about ARA are validated in Table 3. The mean score for teachers with more experience (41–60 years and beyond) is 54.02, whereas the mean score for teachers with less experience (20–40 years) is 51.66. This suggests that teachers with greater experience tend to hold more favorable perceptions of ARA. However, the effect size (0.20) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.04 to 0.44, though indicative of a small effect, is not statistically significant (t = 1.653, df = 728, p = 0.098, p > 0.05, 0.01; Figure 16). This means that the variation in perception based on years of experience is not strong enough to draw a firm conclusion, and experience level does not significantly influence teachers' views on the use of augmented reality in education (Bangga-Modesto, 2024; Nikou et al., 2024a).

3.2 Hypothesis 2

The result of Hypothesis 2 assessed the significance of teachers' attitudes toward augmented reality applications (ARA) in schools. This analysis involved examining the range, frequencies, and percentages of respondents according to their gain scores. Furthermore, the hypothesis explored significant differences in attitude levels and the variables related to teachers' attitudes toward ARA. These differences were identified through chi-square and t-tests, based on the respondents' gain scores.

Table 4 shows the distribution of teachers' attitudes toward augmented reality applications (ARA) across five categories: very high, high, moderate, low, and very low, according to their scores. Most male and female educators displayed a high attitude level, with 204 males and 387 females scoring between 61 and 80, resulting in gain scores of 14,840 and 27,970, respectively, making up 20.33% and 38.32% of the overall gain scores. A lesser number of respondents exhibited a very high attitude (score range 81–100), consisting of 24 males and 66 females, leading to gain scores of 1,975 and 5,437, which account for 2.71% and 7.45%, respectively. Only a small number of educators (9 men and 40 women) are classified in the moderate range (scores 41–60), while no one is noted in the low or very low categories, signifying a generally favorable attitude toward ARA. In total, male and female educators contribute 23.67% and 48.86% to the overall percentage of gain scores, providing a combined total of 72.52%, which emphasizes a largely positive perception of ARA among the participants (Dahri et al., 2024).

The line graph (Figure 17) shows the percentage of gain scores of male and female teachers across five attitude levels (very high, high, moderate, low, and very low) regarding augmented reality applications.

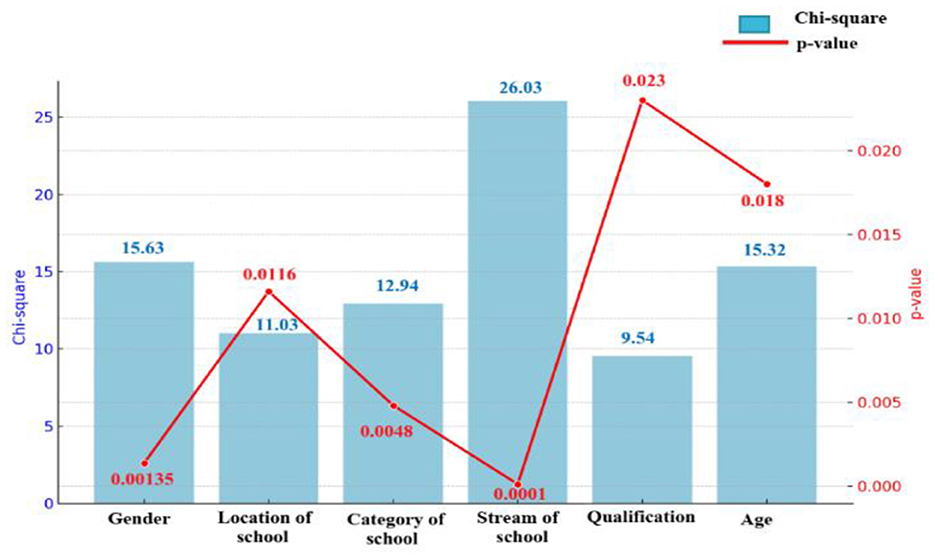

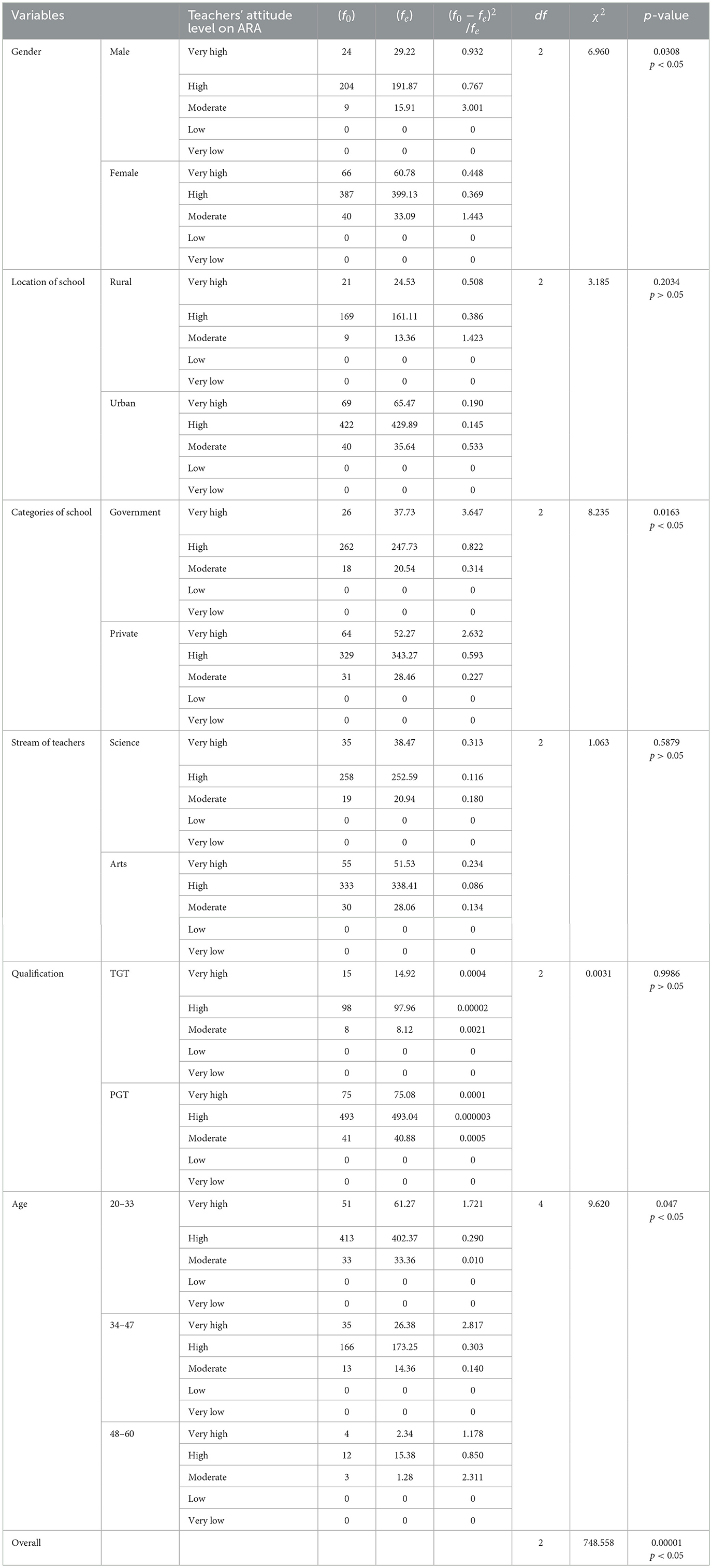

The results of the chi-square test, which explores the consequences of different demographic factors on teachers' attitudes toward the use of augmented reality applications (ARA) in schools, including gender, school location, school category, teacher stream, qualification, and age, are shown in Table 5. However, in this table, the low and very low categories were excluded from the test since all values are zero. At the classroom level, the chi-square (χ2) test examines gender variations in teachers' attitudes about ARA. With two degrees of freedom, the calculated chi-square value of 6.960 is higher than the critical value at the 5% significance level (5.99) but lower than the critical value at the 1% level (9.21). At the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) with a small effect size (0.10) and a confidence interval ranging from 0.02 to 0.17, the p-value of 0.0308 indicates statistical significance. However, at the stricter 99% confidence level (p > 0.01), this result is not statistically significant. According to the results, male teachers are overrepresented in the moderate attitude group and marginally underrepresented in the very high and high attitude categories. In contrast, female teachers show a slightly higher-than-expected presence in both the very high and moderate categories. Notably, no male or female respondents reported low or very low attitudes toward ARA. These results suggest that gender has a statistically significant, albeit moderate, influence on teachers' attitudes toward the use of augmented reality in educational settings (Ewais and Troyer, 2019; Suhaimi et al., 2022).

Table 5. Significant differences in teachers' attitudes toward augmented reality applications (ARA) were examined using various statistical measures, including observed frequency (f0), expected frequency (fe), the difference (f0 − fe), the square of the difference (f0 − fe)2, the ratio of the squared difference to the expected frequency (f0 − fe)2/fe, degrees of freedom (df), the chi-square (χ2), and the p-value based on respondents' gain scores.

On the other hand, the location of the school (rural vs. urban) shows no significant difference in attitude levels (χ2 = 3.185, p = 0.2034, effect size = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.00–0.13), suggesting that the geographical context does not significantly influence teachers' perceptions of ARA (Li et al., 2023; Sánchez-Obando and Duque-Méndez, 2023).

However, the table also presents a chi-square (χ2) test assessing whether teachers' attitudes toward ARA differ significantly based on school category (government vs. private). The observed frequencies (f0) and expected frequencies (fe) for attitude levels (very high to very low) have been compared, and the chi-square statistic has been calculated by summing the squared differences between f0 and fe, divided by fe, for each category. The calculated chi-square value is 8.235 with 2 degrees of freedom. According to the chi-square distribution table, the critical values are 5.991 at the 5% level and 9.210 at the 1% level. Since the chi-square value of 8.235 exceeds the critical value of 5.991 but not 9.210, and given the small effect size (0.10) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.03–0.17, the result is statistically significant at the 5% level (p = 0.0163 < 0.05), though not at the more stringent 1% level. This indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in teachers' attitudes toward ARA between government and private schools, meaning school category does have an influence on teachers' attitudes (Tzima et al., 2019).

The chi-square analysis examining the association between teachers' academic stream (science vs. arts) and their attitudes toward ARA in schools reveals no statistically significant difference. The computed chi-square value of 1.063 with 2 degrees of freedom, along with a small effect size (0.04) and a 95% confidence interval of 0.00–0.10, yields a p-value of 0.5879, which exceeds the 0.05 threshold (p > 0.05). This indicates that the difference in attitudes between science and arts stream teachers is not statistically significant. Both groups showed similar distributions across the very high, high, and moderate attitude levels, with no responses falling into the low or very low categories. These results suggest that a teacher's academic background, whether in science or arts, does not significantly influence their attitude toward adopting ARA in the school setting (Mohamad and Husnin, 2023).

The chi-square investigation of the link between teachers' qualifications (TGT vs. PGT) and attitudes toward ARA found no statistically significant association. The computed chi-square value of 0.0031 with 2 degrees of freedom, a very small effect size (0.002), and a 95% confidence interval of 0.00–0.05 produced a p-value of 0.9986, which is far above the 0.05 significance threshold (p > 0.05), indicating no meaningful difference. This implies that trained graduate teachers (TGT) and postgraduate teachers (PGT) have virtually equal views regarding ARA, with observed frequencies closely matching expected values across the very high, high, and moderate categories. Neither group expressed low or very low attitudes. As a result, the data suggest that teachers' qualifications have no substantial influence on their attitudes toward the use of augmented reality in the classroom (Salleh et al., 2023).

Interestingly, at the end of the table, a chi-square test shows the relationship between teachers' age groups and their attitudes toward ARA. The observed and expected frequencies have been compared across three age categories (20–33, 34–47, and 48–60) and three attitude levels (very high, high, and moderate), with low and very low categories excluded due to zero values. The calculated chi-square value is 9.62 with 4 degrees of freedom, accompanied by a very small effect size (0.08) and a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.00 to 0.14. When compared to the chi-square distribution table, this value slightly exceeds the critical value of 9.488 at the 5% significance level but remains below the 1% critical value of 13.277. The associated p-value is 0.047, which is less than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant association at the 5% level. Thus, the alternative hypothesis is accepted, suggesting that teachers' age has a meaningful influence on their attitudes toward ARA, although the result is not significant at the more rigorous 1% level (Antonioli et al., 2014).

Overall, the findings advocate that gender, category of school, and age are significant factors influencing teachers' attitudes toward the adoption of augmented reality in educational settings alike (Giasiranis and Sofos, 2016; Habig, 2020), while location, academic stream, and qualification level are not (Radosavljevic et al., 2020; Tzima et al., 2019). However, the overall chi-square value of 748.558 with a p-value of 0.00001 (p < 0.05), together with a moderate-to-large effect size (0.40) and a 95% confidence interval of approximately 0.36–0.44, confirms the presence of significant differences among the various demographic groups in their attitudes toward the implementation of augmented reality in school education.

The graph in Figure 18 shows both the chi-square (χ2) values and corresponding p-values for each variable. A green dashed line at p = 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

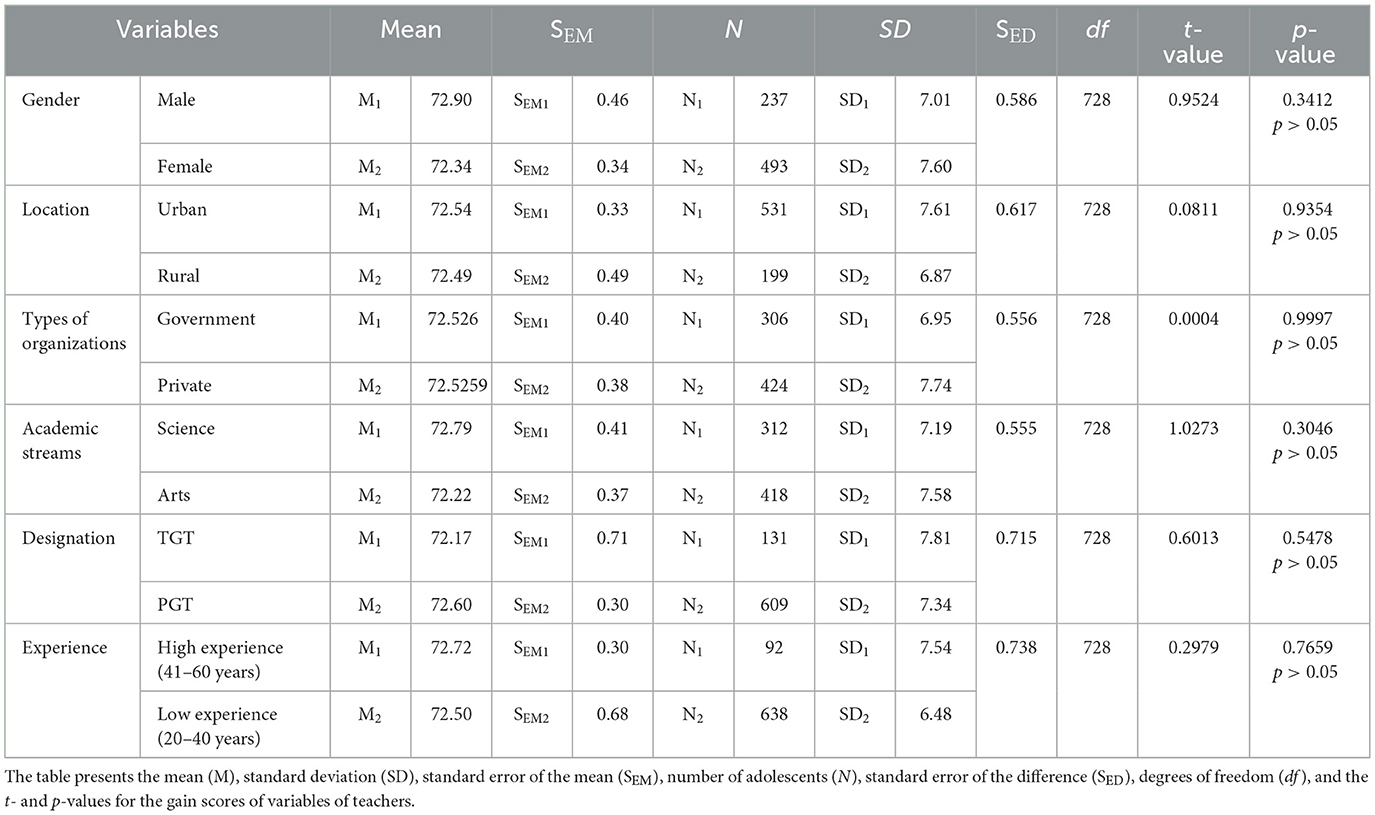

The t-test results are presented in Table 6, highlighting the comparison of teachers' attitudes toward augmented reality applications (ARA) across various demographic variables. The aim of this analysis is to determine whether there are statistically significant differences in attitude scores among different groups of educators.

Table 6. Significant difference regarding the attitudes of teachers on augmented reality applications (ARA), in which t-tests were used to calculate the significant difference between the two groups (variables).

The data presents the attitudes toward ARA between male and female teachers. The mean attitude score for male teachers is 72.90, with a standard deviation (SD1) of 7.01 and a standard error of the mean (SEM1) of 0.46, based on a sample size of 237. The mean attitude score for female teachers is 72.34, with a standard deviation (SD2) of 7.60 and a standard error of the mean of 0.34, based on a larger sample size of 493. The t-value for the difference between male and female teachers is 0.9524, with a corresponding p-value of 0.3412, which exceeds the 0.05 threshold. The effect size is negligible (0.08) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.09 to 0.25, indicating that there is no statistically significant difference in the attitudes of male and female teachers toward Augmented Reality in education. The p-value suggests that the observed difference in means (0.56) could be due to random variation, and we fail to accept the alternative hypothesis. Therefore, gender does not seem to have a significant impact on teachers' attitudes toward the use of augmented reality applications in this sample, although this finding is not consistent with the results reported by Tondeur et al. (2016). The table also shows that urban teachers have a mean score of 72.54 (SEM1 = 0.33, N1 = 531, SD1 = 7.61), while rural teachers have a mean score of 72.49 (SEM2 = 0.49, N2 = 199, SD2 = 6.87). The t-test (t = 0.0811, p = 0.9354, df = 728) and extremely small effect size (0.01), with 95% CI (0.15, 0.17), show no significant difference (p > 0.05), suggesting that location (urban vs. rural) does not significantly affect teachers' attitudes (Heintz et al., 2021).

On the other hand, the government school teachers (M1 = 72.526, SEM1 = 0.40, N1 = 306, SD1 = 6.95) and private school teachers (M2 = 72.5259, SEM2 = 0.38, N2 = 424, SD2 = 7.74) have nearly identical mean scores. The t-test (t = 0.0004, df = 728, p = 0.9997), along with a virtually zero effect size and a 95% confidence interval (0.16, 0.16), confirms the absence of any statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). This indicates that the type of school, whether government or private, has no influence on the measured variable. Similarly, the science teachers had a slightly higher mean score (M1 = 72.79, SEM1 = 0.41, N1 = 312, SD1 = 7.19) compared to arts teachers (M2 = 72.22, SEM2 = 0.37, N2 = 418, SD2 = 7.58). The t-test (t = 1.0273, df = 728, p = 0.3046), together with a small effect size (0.08) and a 95% confidence interval (0.07, 0.23), shows no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). This suggests that subject specialization, whether in science or arts, does not play a major role in influencing the outcome.

Likewise, the trained graduate teachers (TGT) have a mean score of 72.17 (SEM1 = 0.71, N1 = 131, SD1 = 7.81), while postgraduate teachers (PGT) have a mean of 72.60 (SEM2 = 0.30, N2 = 609, SD2 = 7.34). The t-test (t = 0.6013, df = 728, p = 0.5478), along with a negligible effect size (0.06) and a 95% confidence interval (0.13, 0.25), indicates no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). This suggests that the teaching level, whether TGT or PGT, does not have a meaningful impact on the results. Table also shows that the teachers with high experience (41–60 years) have a mean score of 72.72 (SEM1 = 0.30, N1 = 92, SD1 = 7.54), while those with low experience (20–40 years) have a mean of 72.50 (SEM2 = 0.68, N2 = 638, SD2 = 6.48). The t-test (t = 0.2979, df = 728, p = 0.7659), together with a very small effect size (0.03) and a 95% confidence interval (0.15, 0.21), shows no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). This indicates that years of teaching experience do not have a meaningful effect on the measured variable (Salleh et al., 2023).

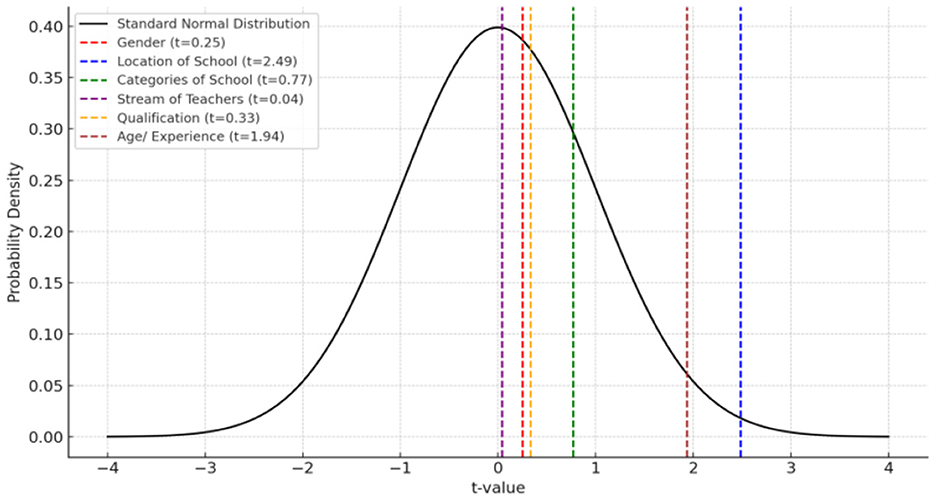

However, the teachers' attitudes about augmented reality applications do not differ statistically significantly across all demographic characteristics (gender, locality, institution type, topic background, teaching position, and experience level), which is similar to the studies of Al-Shahrani (2021) and Bangga-Modesto (2024). This implies that ARA are perceived universally positively or neutrally across varied educator profiles, implying that any future training or implementation of AR-based solutions can be implemented generally and without regard for specific demographic groupings (Mena et al., 2023; Oliveira et al., 2021; Zhu and Chen, 2022).

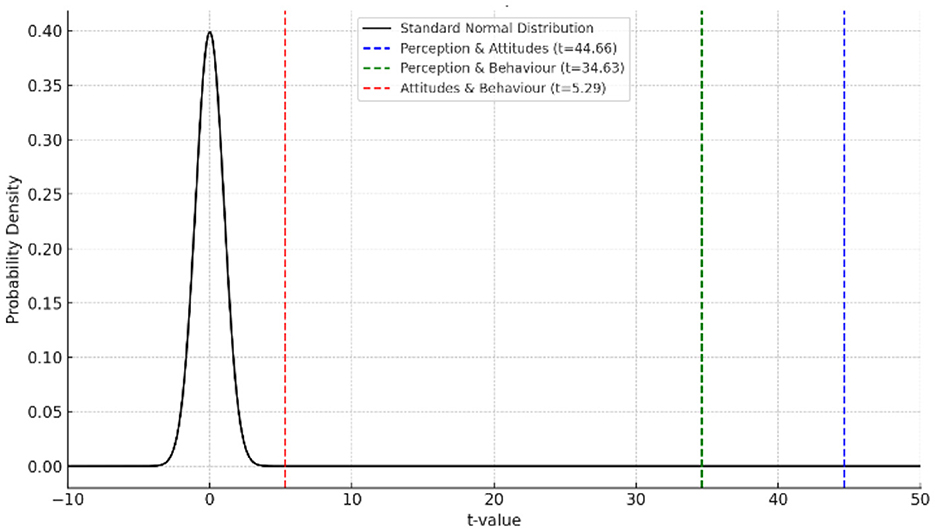

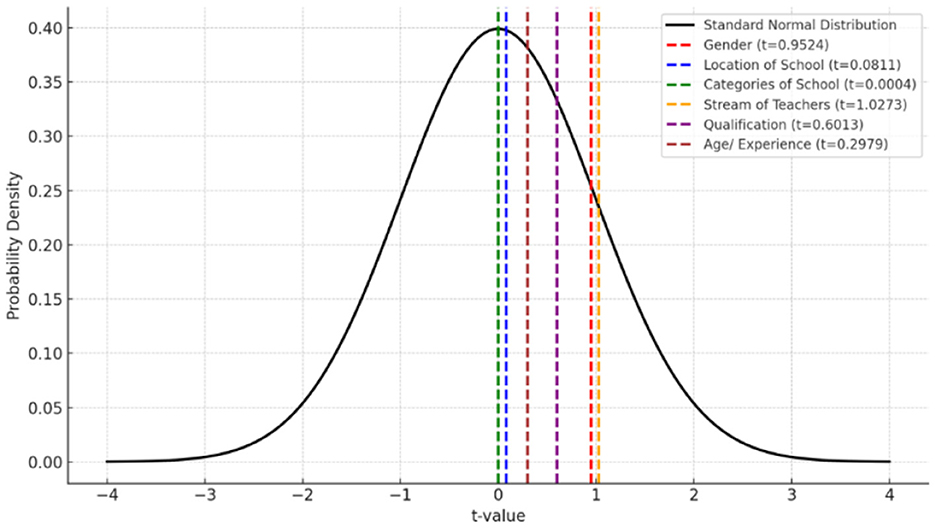

The bell-shaped normal distribution curve with vertical dashed lines, as shown in Figure 19, represents the t-values for each variable, each in a different color. This graph clearly illustrates how far the t-values of each variable deviate from the mean of the standard normal distribution in which closer to the center indicates weaker statistical significance.

Figure 19. Teachers' attitudes on ARA through t-tests across gender, location of schools, categories of school, streams of school, qualifications, and experience.

3.3 Hypothesis 3

The results of Hypothesis 3 evaluated the significance of teachers' behavior in terms of practices toward augmented reality applications (ARA) in schools. This evaluation included an analysis of the range, frequencies, and percentages of respondents based on their gain scores. Additionally, the hypothesis investigated significant differences in behavior levels and the factors associated with teachers' behavior toward ARA. These differences were determined using chi-square and t-tests, derived from the respondents' gain scores.

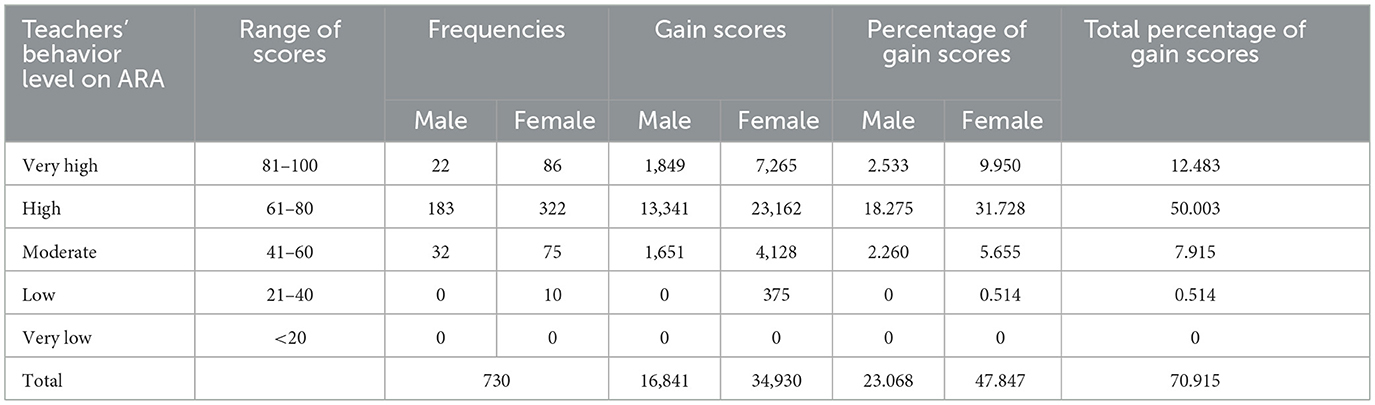

Table 7 illustrates the levels of practice reflected in the behavior of both male and female teachers toward augmented reality applications (ARA), categorized by score ranges corresponding to five behavioral levels: very high, high, moderate, low, and very low. Each level is defined by a specific range of scores: very high (81–100), high (61–80), moderate (41–60), low (21–40), and very low (<20). The table lists the number of male and female teachers within each category, along with their respective gain scores and percentages of total gain scores.

Table 7. Level of practices in terms of behavior of teachers toward augmented reality applications (ARA).

In the very high behavior category, 22 male and 86 female teachers are recorded, contributing gain scores of 1,849 and 7,265, respectively. This corresponds to 2.533% for males and 9.950% for females, totaling 12.483% of the overall gain score. The high category has the largest number of participants, with 183 males and 322 females, contributing the highest gain scores: 13,341 and 23,162, making up 18.275% and 31.728%, respectively, totaling a significant 50.003%. This indicates that a majority of teachers, especially females, exhibit high-level behavioral engagement with ARA. In the moderate behavior range, 32 male and 75 female teachers account for gain scores of 1,651 and 4,128, which represent 2.260% and 5.655%, respectively, totaling 7.915%. The low behavior level has no male participants and only 10 females, with a collective gain score of 375, representing just 0.514%. Notably, no teacher, either male or female, fell into the very low behavior category, indicating a baseline level of positive engagement with ARA across the board.

Overall, the total percentage of gain scores across all behavior levels is 70.915%, with females contributing a higher share (47.847%) compared to males (23.068%). This suggests that female teachers, in general, show more active and positive behavioral engagement with ARA than their male counterparts (Aboudahr et al., 2023). The data highlights a strong inclination toward higher levels of behavioral adoption of ARA, especially among female educators, and provides valuable insight into gender-based engagement trends in educational technology practices (Nizar et al., 2020; Peikos and Sofianidis, 2024).

The line graph (Figure 20) shows the percentage of gain scores of male and female teachers across five behavioral levels (very high, high, moderate, low, and very low) regarding augmented reality applications.

Table 8 contains a detailed analysis of teachers' behavioral practices in using augmented reality applications (ARA) by means of the chi-square test (using multiple demographic and institutional variables: gender, school location, educational categories, teachers' streams, education qualifications, age). The variable very low has been excluded from the statistical analysis due to its zero frequency across all subgroups, which would result in computational distortion in the chi-square test.

Table 8. The significant difference in teachers' behavioral practices regarding augmented reality applications (ARA) was analyzed using various statistical methods.

The table presents the associations between gender and teachers' behavioral levels in relation to ARA. The observed frequencies (fo) are compared with the predicted frequencies (fe) for each level of behavior: very high, high, moderate, and low. Male teachers have significantly lower counts of students with a very high behavioral level (22) than predicted (37.57%), and high-frequency behavior (183) is reported more frequently than the predicted (163.97%), while low-frequency behavior has been reported rarely (with an expected count of 3.25%). These differences contribute to the chi-square statistic for males and individual components such as 4.87 (for very high) and 3.25 (for low) indicate their substantial deviation. However, results from females are similar, with more participants than expected reporting very high behavior (386 vs. 72.93), and slightly fewer participants than expected engaging in the high category (322 vs. 341.03).

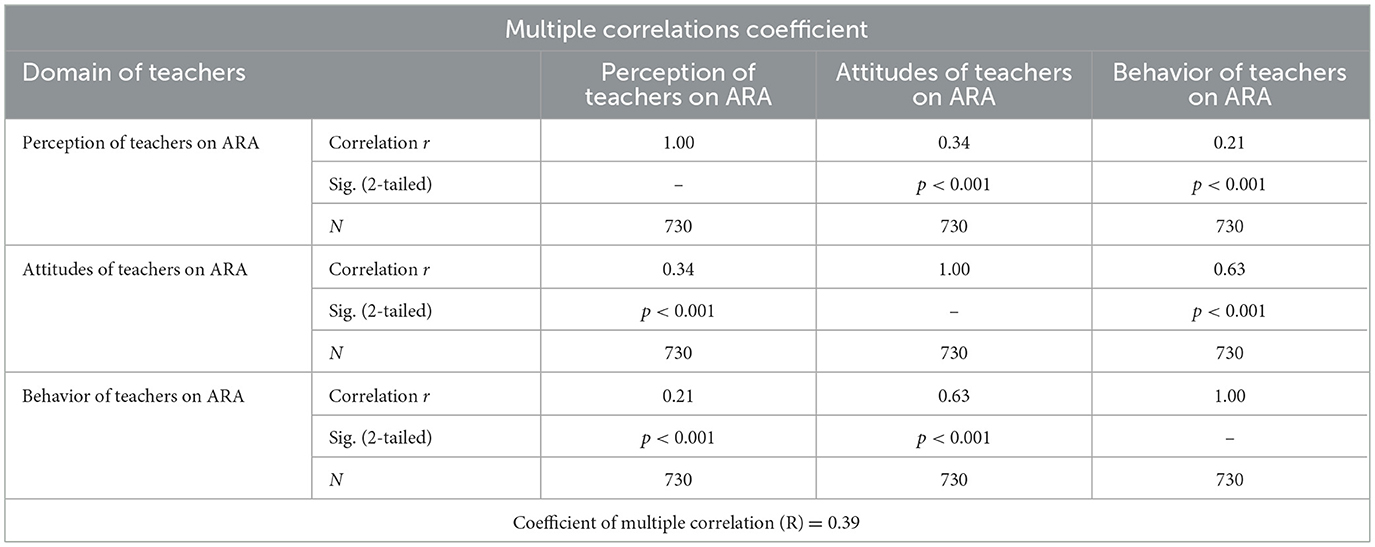

The cumulative chi-square value is 15.63, calculated with 3 degrees of freedom. This is significantly higher than the critical values at the 0.05 level (7.015) and the 0.01 level (11.334). The p-value of 0.00135, together with a small effect size (0.18) and a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.08 to 0.22, confirms that the result is statistically significant (Ghobadi et al., 2023). Similarly, the table also provides information on the association between school location (rural vs. urban) and teacher behavioral levels in relation to the use of ARA. The chi-square value of 11.03 with 3 degrees of freedom and a p-value of 0.0116, along with a small effect size (0.12) and a 95% confidence interval of 0.05–0.19, indicates that the result is statistically significant at the 0.05 level (critical value = 7.815). However, it falls just short of the stricter 0.01 significance level (critical value = 11.345), but slightly below the statistical significance threshold at the 0.01 level (critical value = 11.345). This indicates that there is a significant association between school location and teacher behavioral levels in relation to the use of ARA, and those rural and urban teachers have significantly different approaches and behavioral practices with respect to augmented reality in classrooms (Suhaimi et al., 2022).