- 1Seymour Fox School of Education, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

- 2Télécom Paris ‑ Department SES, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, France

- 3Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

An analytical framework for observing ethical learning in schoolchildren during social interaction has been recently developed. It comprises two tools for appraising ethical thinking and behaviour: dialogue on ethics (DoE) and ethics of dialogue (EoD). Studying the effectiveness of a project aimed at promoting ethical learning of socially-oriented values—empathy, inclusion, and tolerance—within the context of dialogic education, has appeared as providing a complex picture: the relation between children’s DoE and their EoD was positive where the topic posed for discussion presented a dilemma. In contrast, it was negative when the discussion was conceptual, and the teacher was dominant. In the present paper, we describe a case study to illustrate and explain these results. The DoE/EoD analytical framework was adopted to observe when and why ethical thinking and conduct could be coordinated. The case study shows that ethical learning in its epistemological and behavioural dimensions can be promoted or inhibited in contexts of dialogic education, depending on design principles.

Did you say ‘values’? Whose?

In today’s world, full of political and technological upheavals, it is impossible to avoid the problem of good versus bad conducts or judgments as people from different communities encounter each other on social media. Thus, for example, Facebook employs a strike system: a list of penalties imposed on users who violate its community standards. Modern democratic countries comprise people of different beliefs, cultures, and ideologies with common rights, as well as places where they can meet: schools, universities, associations, and, recently, social networks. According to the law, people sharing a community have duties; but these duties cannot be mechanical instructions to be followed in order to live together. With the demise of religious beliefs, people nevertheless feel the urge to share something on a global level. Many psychologists in moral development hold a relative position: the fact that morality heavily depends on cultures and conventions. Some psychologists who have distinguished between the moral and the conventional create space for sharing. The distinction at issue is between (a) acts that are judged to be wrong only because of a contingent convention or because they go against the dictates of some relevant authority, and (b) those that are judged to be wrong quite independently of these things, characterized by a certain seriousness, and justified by appeal to the notions of harm, rights, or justice. Elliot Turiel emphasized this distinction, and drew attention to the danger, if overlooked, of lumping together moral rules with non-moral “conventions that further the coordination of social interactions within social systems” (Turiel, 2002, pp. 109–111). Specifically, according to Turiel’s theory of domains of social development, moral judgments (based on concepts of welfare, justice, and rights) differ from understandings of the conventions and customs of societies, as well as from arenas of personal jurisdiction. He has applied the theoretical approach to the study of the relations of morality and culture. Turiel’s theory provides a framework in which morality is beyond cultures. Can declarations such as Les Droits de l’Homme (The Rights of Man), emanating from the French Revolution, and, more recently, the United Nations’ “values and behaviours” Framework (United Nations, 1999) — inclusion, integrity, humility, humanity — credibly claim universality that is globally accepted? Where is the standpoint outside all standpoints from which such claims can be justified?

Although Turiel’s theory of personal development is contested, mainstream research is based on the legacy of the temporally remote Aristotelian philosophy. Aristotle was interested in the good and the bad, not through values to be shared in our reasoning and actions, but as “virtues”: traits of people that practice actions defined as contributing to the common good. According to Aristotle’s teacher, Plato (The Republic), the list of these actions is provided by the philosopher-king. As a philosopher, Aristotle saw in the virtues cultivated by iterated actions entities to be reflected on; but the good for him originated primarily from actions. Developmental psychologists have adopted a somewhat Aristotelian view of moral conduct and judgment as general traits and disposition partly cultivated by action (Killen and Smetana, 2014), which lead individuals to develop a moral identity. Grit (enthusiasm and perseverance towards goal achievement), for example, has been associated with moral competence. How can such a direction, based on such an individualistic model of moral development, be related to values and morality widely shared by society?

Modern democracies invite democratic participation as well as public justification. These are general actions taken in the public sphere that help sustain strong democracies. Therefore, handling the particular versus universal values in a Trumpian world, in which each group has its own ‘truth’ and values, by opting for particularism as a reaction against so-called universalism of values, is dangerous for the maintenance of democracies, not only as structures that help people function together, but as systems in which togetherness is lived out. Instead of facilitating democratic processes, social media weaken democracies as they lead their users to mistrust policies, public institutions, and the world of politics. Social media enables the creation of echo-chambers: places where groups of like-minded people meet and polarize their views in relation to other groups.

In this paper, we will describe a case study to exemplify that democratic practices can provide opportunities to foster a new kind of morality, which combines thinking and action. We capitalize on the fact that important agencies in the world are interested in providing shared values, not inculcating them into young citizens. As claimed by many philosophers, deliberations and especially dialogues are ways to strengthen democracy (e.g., Dewey, 1916; Arendt, 1998/1958). The case study we will describe is taken from a large study that involved children from several countries across Europe, who dialogize about values. The values were not imposed but suggested through sources that allude to them. The students in the case study participated in a program in which a dialogic pedagogy was implemented. This pedagogy aimed to invite interactions that fit the values fostered in the program. This is a middle-term program, and as such, it invites the iteration of interactions through dialogues about those values. The case study describes the intertwining of actions and thinking about values. To some extent, the story is utopic: its setting (the resources, the dialogic rules that govern deliberations, etc.) delineates the limits of a democratic game. But the game in our case was long, involved many countries, and was supported by a substantial budget from the European Union. Our utopic case study thus describes a serious game.

An EU project: dialogue and argumentation for cultural literacy learning in schools (DIALLS)

A major goal of the European Union is to achieve cohesion between the member states, in both societal terms (rules, standards, laws) and economic terms (free circulation of goods and people, budgetary rules, etc.). For a long time now, education has been viewed as a long-term panacea for this: educating future citizens to become Europeans, with shared values. But what are or should be those “European values”?

For anyone who follows the news, this would seem to be an insurmountable problem. There are conflicts in values, enshrined in laws, within EU countries and across them. Of course, there is, for a large number of countries, a shared history, with respect to the Roman Empire and the adoption of Christianity as a state religion. But, today, appeal to the history of religions simply fails ‘to cut it’. As we argue above, many European societies grow more and more secular; and if people do adhere to religions, they are now multiple, in increasingly multicultural societies.

So, what are European values? This definition is necessary for the design and implementation of education for young Europeans. Despite the multiple voices that can be heard, the European Union provides normative answers, to be found in its Charter of Fundamental Rights.1 These rights include values such as human dignity, freedom, equality and human rights (a circular definition?). More specifically, the European Commission states that “The EU values are common to the EU countries in a society in which inclusion, tolerance, justice, solidarity and non-discrimination prevail. These values are an integral part of our European way of life”.2 These are the rules, whether people and states agree or not.

The EU funds research projects in every area of science and technology, including education. At the beginning of the second decade of the twenty-first century, we participated in a three-year-long project funded by the EU called “DIALLS”3, an acronym which stands for “Dialogue and Argumentation for Cultural Literacy Learning in Schools.” The project took up the normative definition of European values — how could it do otherwise? — having the basic aim of teaching children to be tolerant, empathetic, and inclusive through talking together. It could be argued that other values should have been taught (such as “social justice”), but these were the ones on which the project focused.

Teaching these values by simply presenting students with their definitions and a few case studies would not have been appropriate to the inherently dialogical or debatable nature of values, their essence, and their role in guiding actions and judgments. Therefore, as we said, the chosen pedagogical approach was that students would learn by talking together. This approach draws on the now considerable research literature on cooperative/collaborative learning (e.g., Mercer and Littleton, 2007) and, more specifically, on an approach called “dialogic education” (Alexander, 2005; Michaels et al., 2008; Wegerif et al., 2019), the general idea of which is that the teacher should strive to maintain an open ‘space of dialogue’ in the classroom, within which the children will be encouraged to voice the diversity of their views on a question, and co-construct a common understanding with respect to answers to this question. But how can this be achieved when any European project on education involves dialogue across different cultures and languages?

DIALLS adopted an original approach, which was to base children’s dialogues on “wordless texts”: picture books and videos comprising narrative sequences of images alone. The texts were specifically chosen given their propensities to stimulate discussion on the chosen EU values. For example, the picture book “Vacio” (Empty), authored/illustrated by Catarina Sobral (2014), explores the themes of loneliness, isolation, and the need for love and compassion, through the tale of an “empty” man who finds love and becomes (ful)filled. The target European value for the children’s discussions around this picture book was that of empathy. Another example is the short (wordless) video “Papa’s boy” (see https://dialls2020.eu/cllp-papas-boy-ks2/), featuring a boy mouse who wears a skirt in order to engage in his passion, ballet dancing, while the Papa mouse, who is interested in boxing, wants his son to follow in his footsteps. The boy mouse saves his father from a cat by dancing in front of it, leading the father to accept his son. Clearly (at least from the point of view of the researchers), here the value of tolerance is at stake.

To some extent, the wordless texts implicitly conveyed ethical lessons to be learned that designers wanted to promote—for example, in “Papa’s boy,” the idea that parents should tolerate their children’s tendencies, when they are not widely accepted by the society. However, students did not necessarily reach such conclusions, in spite of the intended design. This freedom resembles the freedom given to students provided with texts for discussion in the program P4C (Philosophy for Children) that led to impressive interpretations, even when these interpretations were not anticipated by their designers (Lipman, 2003).

A very scrupulous pedagogical design was produced, that specified the alternation of individual wordless reading, small-group and whole-class discussions, with or without teacher guidance (specific teacher “prompts” were specified). This design was meant to be applied in an identical manner in each of the countries that participated in the project: Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom (coordinator), and Israel, on which we partly focus below. EU projects allow and encourage (self-funded) participation from a restricted list of non-EU countries, e.g., Norway, Switzerland, and Israel. The Israeli team at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was responsible for developing an online platform dedicated to the project’s needs, as well as for providing a set of schools in which the DIALLS pedagogical approach was implemented.

The Israeli case study begins with the negotiations that took place towards the implementation of the sessions in 12 schools. The leaders of the Israeli team (and among them one of the Ministry of Education superintendents for Language Arts) presented the program to principals and teachers. While the latter were impressed by the quality of the resources (the wordless texts), and by the scrupulous design of the successive sessions in three grade levels (the Cultural Learning Literacy Programme (CLLP) described above), they had several serious reservations. The first one was essential. We presented the DIALLS program as promoting European values. The principals and teachers were surprised to hear that empathy, tolerance, and inclusion are presented as European values. They explained that such values are important in their daily teaching, and in general in the Israeli society. We explained to them that the term “European values” points at the intention of all European countries to instill these values in the educational system, and that we are invited to join this common effort. The principals and teachers were not convinced by this explanation, arguing that these values belong to the Jewish heritage no less than to the European one. They viewed empathy, tolerance, and inclusion as values that belong to a Judeo-Christian heritage. The Israeli team decided to share with the DIALLS project directors this reservation. The primary definition of European values was thus changed in the official site of the DIALLS project into the following:

[The project] focuses on certain values seen as universal—or at least, European—values (tolerance, empathy, inclusion). … Perceiving certain values as universal might present a problem as values, in many cases, are culture-bound (i.e. justice, rights). We would like to maintain that in speaking of universality, we do not mean universality of the nature of the values. We see the core values of DIALLS as universal; nonetheless, we do not expect their expression/interpretation to be identical within different cultures. The participating countries (UK, Germany, Lithuania, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Israel) are not geographically far apart, and could be defined as ‘western’, yet they are quite dissimilar from each other culture-wise.

This formulation did not refer to religion. The Israeli team shared this decision, and endorsed the formulation, which did not impose on one culture values that allegedly belong to another.

The second reservation concerned the design of the sessions—the CLLP program. The detailed instructions given to teachers in each of the sessions seemed to the Israeli principals and teachers inspiring but constraining. The teachers asked whether the instructions were mandatory or merely suggested. This situation led the Israeli team to take an internal decision to give the teachers some freedom in the implementation of the CLLP program.

The third reservation concerned the use of a new platform in order to mediate dialogues. Teachers felt that animating discussions around wordless texts according to a dialogic pedagogy was highly demanding, and that the use of dedicated technologies to mediate these dialogues constituted an additional burden. We proposed to invite the teachers to a workshop at the Hebrew University, in which some instructors of the Center for Dialogic Education would model the use of the dedicated platform in animating educational dialogues with their students. We consequently invited the students and the teachers to a two-day-long workshop at the Computer Center of the Hebrew University (see Baker et al., 2023). We now unfold the story of what transpired in different classrooms in several schools across Israel, in face-to-face and online discussions involving the adapted DIALLS project pedagogical approach.

This is the context of our case study. It involves groups of children commenting on the wordless book Papa’s Boy. In research on moral/ethical development/learning, methodological approaches that trace interactions are often missing. True, general methodologies tracing the emergence of learning processes in dialogic contexts have been elaborated, such as the scheme for educational dialogue analysis (SEDA; Hennessy et al., 2016), whose micro-level codes—open questions, extended contributions, reasoning with evidence, etc.—help to trace guided reasoning in classroom talk. Other methods were used for focusing on the study of the learning of concepts in unguided group interaction though moves of deliberative argumentation (e.g., Asterhan and Schwarz, 2009). However, although Dialogic Education is rooted in philosophical ideas that favour the social, the epistemological, and the ethical, research on learning in Dialogic Education focuses on the social and the epistemological only, and has so far excluded the ethical. We present a methodology that traces learning of ethical thinking and conduct in discussions among children that was adapted in the case study.

Methodology tracing the learning of ethical thinking and conduct in discussions among children

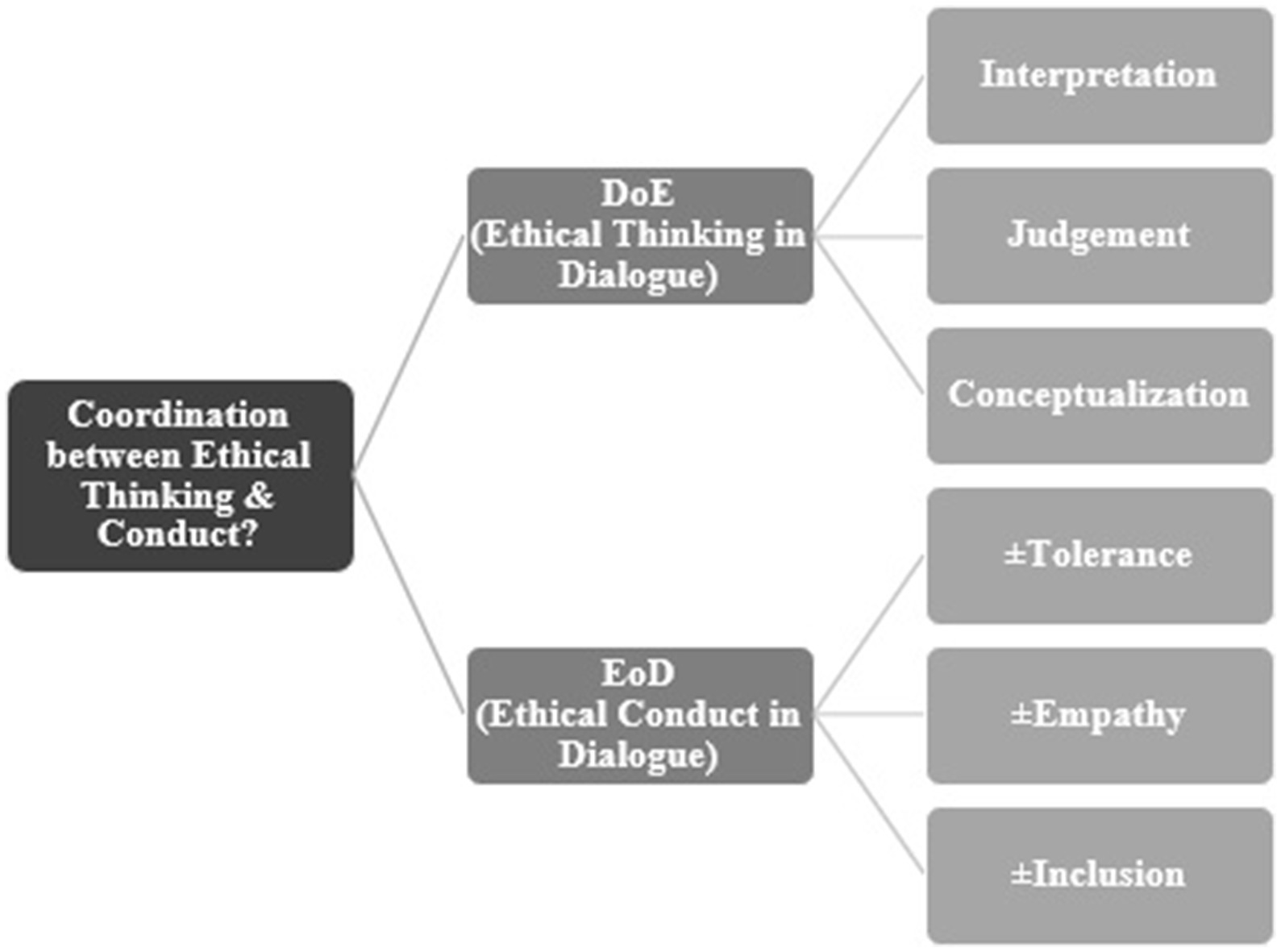

Asterhan and Schwarz (2009) developed a new methodology inspired by Interaction Analysis (Bakeman and Gottman, 1997). This methodology has two dimensions: Dialogue on Ethics (DoE) and Ethics of Dialogue (EoD). The DoE dimension bears on the processes by which student-participants co-construct understandings, in relation to the three values under focus: tolerance, inclusion, and empathy. This dimension is defined in relation to research on the way in which students engage with literary texts in educational situations, focusing on the ethical aspects of the texts (Rouviere, 2018). Baker et al. (2023) have suggested that the processes by which students engage with these texts when co-constructing the “moral of the story” can be described in terms of interpretation, judgment, and conceptualization. The EoD dimension bears on the ethical conduct of students in their deliberations. We restricted the EoD dimension of analysis to the consideration of the same three values: tolerance, inclusion, and empathy, but with respect to the interpersonal relations between students, in their hic et nunc dialogue on them.

The DoE and EoD dimensions enable us to simultaneously measure ethical thinking and behaviour using the same methodology (i.e., that of Interaction Analysis) while concentrating on the same values in both ethical dimensions. This methodological innovation thus facilitates the investigation of the object of the study: how ethical thinking and conduct can coordinate.

Brandel et al. (2024) transcribed and translated into English a part of a multilingual database (Rapanta et al., 2021). Readers interested in inter-coder reliability may consult the paper. Figure 1 sketches the methodology according to the aspects found in the discussions.

Figure 1. The different aspects comprising the two main dimensions indicating ethical learning—DoE and EoD.

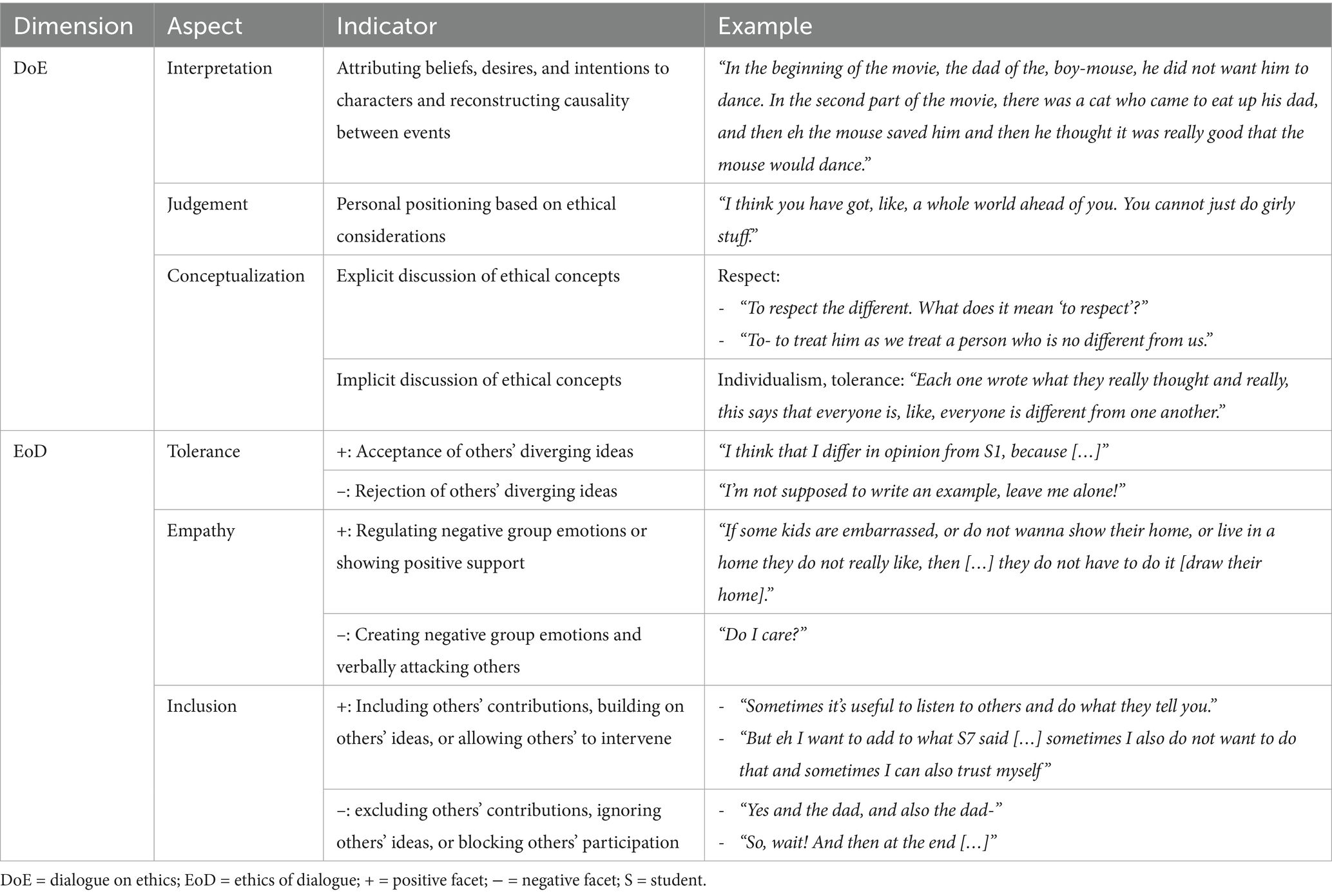

Table 1 provides a code summary of dimensions, aspects, and indicators comprising the coding scheme.

The DoE and EoD dimensions enable us to simultaneously analyse ethical thinking and behaviour using the same methodology (i.e., that of Interaction Analysis) and concentrating on the same values in both ethical dimensions. This methodological innovation thus facilitates the investigation of the object of our study: the ways in which ethical thinking and conduct can coordinate.

Brandel et al. (2024) relied on session 3 in the program to show that the more students discussed ethical issues (higher DoE rates), the more ethically they behaved (higher +EoD rates and lower –EoD rates). In session 8, the more students discussed ethical issues (higher DoE rates), the fewer manifestations of ethical behaviour they made (lower +EoD rates). These findings pertain to ethical learning, showing that in certain conditions ethical thinking and conduct correlate, and suggesting that the program based on dialogic pedagogy promoted coordination between ethical thinking and conduct.

The reverse trend observed in session 8 can be attributed to the heavier moderation of the teacher in this session, as indicated by the fact that teacher turns constituted a significantly-larger volume of class dialogue in session 8, compared to session 3, and by the negative correlation between teacher involvement and students’ manifestations of +EoD, unearthed only in session 8. An additional factor that could have contributed to the negative correlation between DoE and +EoD in session 8 concerns the topic posed for discussion. While session 3 revolved around an ethical dilemma presented as a question juxtaposing two stances — following social stereotypes versus staying true to oneself —, session 8 concerned the conceptualisation of home/belonging. The former seems likelier to provide opportunities for more natural interaction than the latter, as was indeed the case.

The correlations (both positive and negative) found between ethical thinking and conduct in the two sessions contrast with the lack of correlation previously reported between moral reasoning and action (Blasi, 1983; Talwar, 2011). These findings confirm some insights derived from a case study conducted on one of the discussions, in which Baker et al. (2023) showed how students are led to discuss and understand ethical implications of a particular narrative, and how this relates to the quality of their collaboration. Brandel et al. (2024) based their interpretation of the findings on inferential statistics, conducting the analysis at the class level, without directly analyzing the deployment of dialogues and their precise characteristics, or recognizing the specific students that manifested DoE, EoD, or both. Such analyses are the focus of the present case study.

The case study

The story we will tell comprises three episodes from teacher-mediated discussions (either in whole-class or small-group discussions) held in two sessions. The episodes revolve around wordless videos (Papa’s Boy and Baboon on the Moon).

First episode: students talk well about ethics and behave ethically in a teacher-led whole-class discussion

The first episode centers on the wordless video “Papa’s Boy.” Seventh-grade students discuss the acceptance and tolerance of the behaviour and identity of the boy mouse character in the video.

“Papa’s Boy” was explicitly intended by its designers to raise issues relating to tolerance of different ways in which gender roles may be played out. As the name suggests, it involves a boy mouse who nevertheless wants to be a ballet dancer, wearing a girls’ ballet tutu dress. His behaviour contrasts markedly with the aspirations of his father, a boxer, who wants his son to follow in his footsteps. In the story, the father mouse is attacked by a cat, and the boy mouse saves him by ballet dancing around the cat, thereby gaining his father’s acceptance, or even approval. As we shall see, the story stimulates the students to ask several questions with moral implications, such as whether it is acceptable for boys to engage in “girly” activities, and vice-versa; or the question as to whether children are obliged to live up to their parents’ expectations.

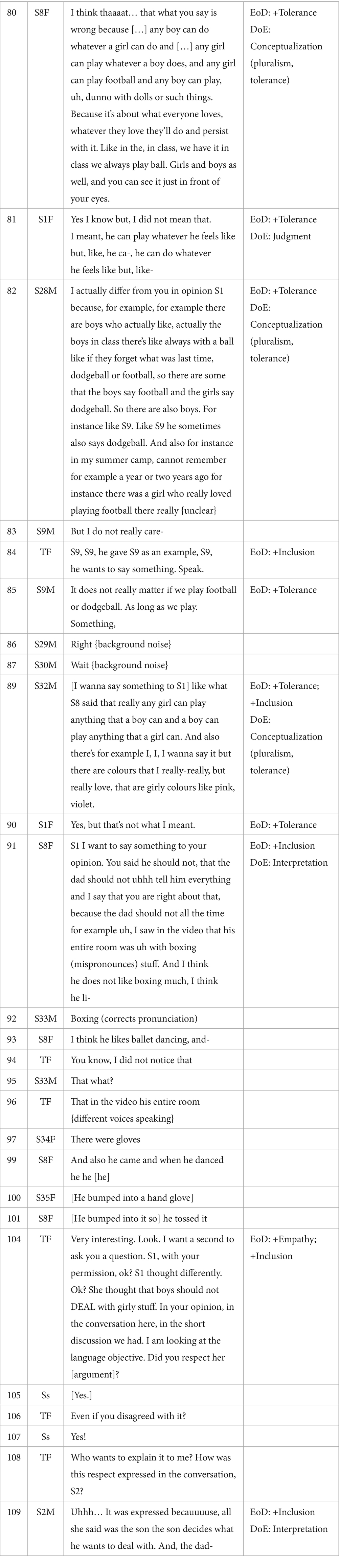

We will see that the discussion on those values coincides with more inclusive and tolerant behaviour on the part of the students towards a fellow student (S1) holding a different opinion than her classmates. The utterances marked in bold stress the parts in the excerpts that serve the purpose of the episode—students talking well about ethics while behaving ethically as they do so:

The above excerpt illustrates the presence of a large concentration of +EoD manifestations in a discussion revolving around DoE. The students illustrate +EoD and no –EoD whatsoever, as they express much +tolerance (utterances 80, 81, 82, 85, 89, 90), as well as some +inclusion (utterances 89, 91, 109) towards S1. Their ethical behaviour (EoD) towards S1 is evident in the manner in which they conduct their discussion, expressing their disagreement with her in a respectful way and bringing evidence from the video and from their daily lives in order to support their opinion. None of the other students belittles S1 or disrespectfully dismisses her opinion, though it is quite evident that none of the others agrees with her. They are being tolerant and inclusive to a minority among them.

Moreover, the students’ ethical thinking (DoE) can be observed in their interpretation of the characters’ desires in the video, in their judgment towards those characters, and in their conceptualization of values emanating from the video. The students illustrate DoE by conceptualizing ‘pluralism’ and ‘tolerance’ (utterances 80, 82, 89), expressing judgment (utterance 81), and interpreting the characters’ mental state (utterances 91, 109).

Utterances 80, 82, and 89 show that the illustration of tolerance in the students’ EoD (in practice) often co-occurs with their conceptualization of tolerance and pluralism (in theory).

The protocol shows that the teacher creates an atmosphere where +EoD is prominent. In utterance 104, she is not only empathetic (“Very interesting”) and inclusive (“I want a second to ask you a question. S1, with your permission, ok?”). She also translates DoE into EoD (“Did you respect her [argument]?”), thus modeling for the students how to combine the two and give rise to a respectful discussion. This combination of critique/challenge with openness and respect makes for a potentially productive learning interaction. In the present protocol, students were perhaps not friends, but they are made friends by the norms the teacher instills. And the translation of dialogue on ethics to ethics of dialogues explains the concurrent manifestations of DoE and +EoD on the part of the students.

Second episode: students talk well about ethics without behaving ethically in their dialogue

The second episode also occurs in a whole-class discussion orchestrated by a teacher. The video in question is “Baboon on the Moon,” showing a baboon who lives manifestly alone on the moon and whose job is to light up the moon at night. When the baboon stares at his home on planet Earth, tears well up in his eyes and he plays a mournful trumpet solo. Although the video is speechless, it clearly conveys the longing of the baboon to his home on earth.

From the pedagogical designers’ point of view, the video stimulates discussion between the students on two main topics or issues. Firstly, there is the question of empathy for the manifestly very sad baboon, who misses his home. Secondly, what is the meaning of ‘home’?

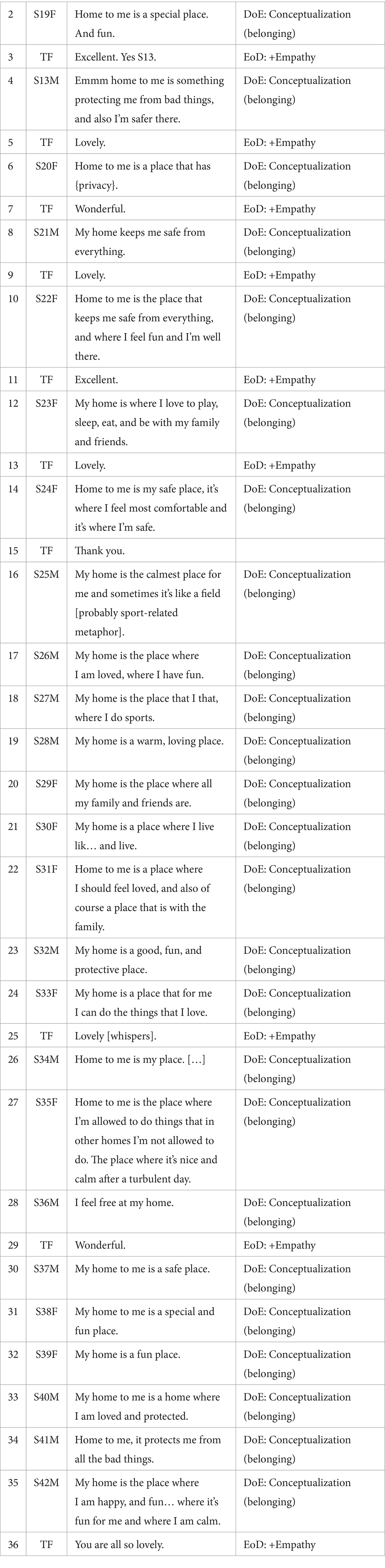

The following discussion occurred in session 8. After watching the video, the teacher invites seventh-grade students to engage in a discussion revolving around the question ‘What is home to me?’. The video vicariously deals with the question of ‘house’ versus ‘home’. As with the first episode, the utterances that illustrate the fact that the students talk well about ethics (although they do not behave ethically) are stressed in bold.

In the above episode we witness a very interesting disassociation between DoE and EoD on the part of the students, as they only illustrate DoE, expressed solely by conceptualizing ‘belonging’ according to the instruction they received. This conceptualization of ‘belonging’ is manifest in 25 utterances (appearing in bold in the table).

The absence of EoD manifestations on the part of the students demonstrates the lack of inter-student interaction: Each speaker gives a short response and does not relate to others’ responses. Although it is technically a whole-class discussion, in fact there is no true interaction between the speakers: The teacher goes from one student to the other, asking for their statement (all statements are quite similar), giving positive reinforcement to most students without going into the content of their statements at all, and moving on to the next student. This consecutive alternation between EoD on the part of the teacher and DoE on the part of the students—witnessed in different classes following the same lesson plan—is uncharacteristic of a natural discussion. The students’ participation, thus, proceeds without any form of active listening to other students.

In this protocol, the teacher indeed creates an atmosphere where students can feel comfortable to express their opinions, but she does not induce them to integrate these opinions into a fruitful discussion. As mentioned before, the task was designed to navigate the discussion towards a conceptual distinction between ‘house’ and ‘home’. This focus on conceptualisation resulted with the absence of dialogue. It appears that most of the teachers implemented the lesson plan of session 8 through a centralised discussion, and this explains the finding that in this session the less students discussed ethical concepts, the more ethical their behaviour was. In session 8, discussing ethical concepts meant interacting with the teacher, while the students’ ethical behaviour towards their peers was rendered irrelevant.

A posteriori, one might have expected this kind of interaction in which the teacher is at the centre. However, this paper adheres to the analysis of the deployment of educational dialogues, and in itself, the present example illustrated the fact that when the teacher is at the center, EoD is low.

The two episodes show that the relation between children’s DoE and their EoD was positive where the topic posed for discussion presented a dilemma and students’ interaction proceeded under moderate teacher guidance. In contrast, it was negative when the discussion was conceptual, and the teacher was dominant. Therefore, ethical learning, in its epistemological and behavioural dimensions, can be boosted or inhibited in context of dialogic educations, depending on design principles.

Third episode: students comply with the ethical behaviour of the teacher in their dialogue

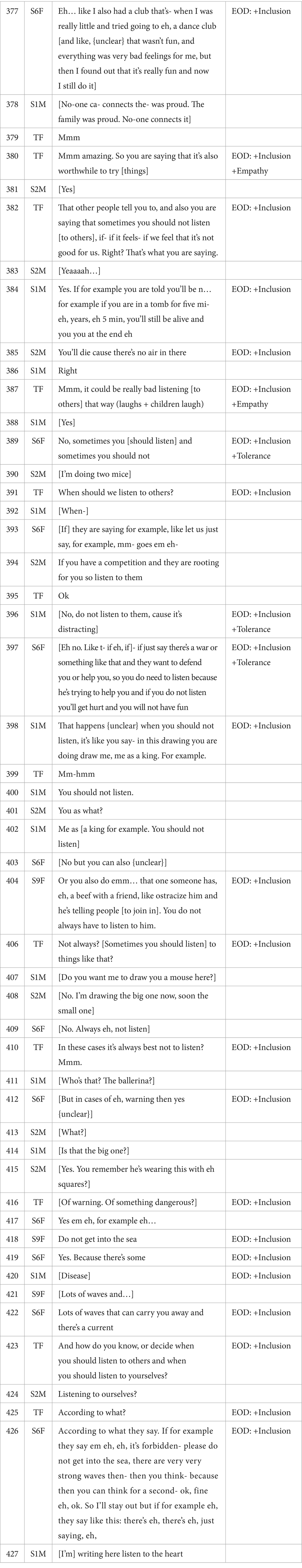

The third episode depicts a setting in which a teacher guides a small group of students (two boys and two girls) that discuss the video they watched earlier. As we will see, this episode shows manifestations of +EoD on the part of both teacher and students.

In the above excerpt both students and teacher manifest many utterances coded as +EoD, mainly +inclusion. The distribution between teacher’s + EoD and students’ + EoD is quite balanced. The teacher expresses 11 manifestations of +EoD in 9 different utterances, all of which demonstrate +inclusion and 2 of which demonstrate +empathy as well. The students express 17 manifestations of +EoD in 14 utterances, all of which demonstrate +inclusion and 3 of which also demonstrate +tolerance.

This episode illustrates the finding that the more ethically the moderator behaved, the more ethical was her students’ behaviour. A detailed analysis of the protocol shows an interesting mechanism in the relation between the behaviours of the teacher and the students. First, the students did not imitate the teacher. Rather, the discussion changed direction from the behaviour of the characters in the wordless video into the behaviour of the students in different real-life situations requiring ethical thinking. The teacher engages the students into translating a discussion about DoE into a discussion about ethical behaviour in general, thus exceeding the scope of EoD (e.g., “So you are saying that it’s also worthwhile to try [things]… That other people tell you to, and also you are saying that sometimes you should not listen [to others], if- if it feels- if we feel that it’s not good for us. Right? That’s what you are saying,” in utterances 380 and 382). The video helps in the development of EoD. Secondly, the distribution of EoD categories is not the same for the teacher and for the students. The teacher is empathetic and inclusive, while the students are inclusive and tolerant.

Discussion

How should we conclude this case study: what is the moral of our story? In the society of our times, we do not like morals of stories. However, nothing in our story was crystal clear and predetermined. Let us begin with the resources—the wordless picture books and videos. Did the creators of these resources have a crystal-clear message to convey? Not necessarily. In the DIALLS project, perhaps some of the designers, those who led the Cultural Learning Literacy Programme (CLLP), had definite lessons in mind. In their defense, we should say that they brought the wonderful collection of wordless texts to classes in all participating countries. Their design was extremely detailed and while this was appreciated by many teachers, the Israeli teachers resisted this meticulousness. The latter preferred a looser design in which they had some freedom in their way to trigger discussions around those texts. As Baker et al. (2023) argue, the issues the students discussed were not necessarily the issues the designers thought about. But is it not the nature of wordless texts? Mendelssohn’ Songs without Words, or Verlaine’s Romances sans paroles are artistic creations that convey the ambiguous, that aim for the fuzzy. Verlaine’s poems appear at the dawn of impressionism and invite the readers to figure out moods and feelings beyond words. And like Mendelssohn’s Songs without words, and Verlaine’s Romances sans paroles, the wordless texts used in our case study were beautiful. The aesthetic leaves its impression on readers/observers and does not leave them indifferent. This is one of the morals of our story: the fact that the interactions among children, or between the children and their teacher, were mostly fruitful. The dialogic context contributed to the expressive moments that developed.

In the three episodes of our story, the ideas were on their high point. As for the coordination between ethical thinking and conduct, it depended on the task, as well as on the teacher. In the second episode, there was a gap between speaking about ethics and behaving ethically, between understanding what is right to do and actually doing it. For the teacher, the problem is whether to hold on to their control, or leave space for the students to discuss and behave ethically towards each other. The dilemma format in the first episode helped students behave ethically, while the didactic format seen in the second episode worked to the detriment of their ethical behaviour. Most interestingly, the teacher’s ethical behaviour in the third episode led the students to interact ethically, although they did not imitate her behaviour. The complexity of the relation between ethical thinking and behaviour is then the second moral of our story, and it stresses the difficult role of the teacher in coordinating them.

As aforementioned, in session 3, the more students discussed ethical issues [higher Dialogue on Ethics (DoE) rates], the more ethically they behaved [higher +Ethics of Dialogue (+EoD) rates and lower –Ethics of Dialogue (–EoD) rates]. In session 8, the more students discussed ethical issues (higher DoE rates), the fewer manifestations of ethical behaviour they made (lower +EoD rates). These findings show that in certain conditions ethical thinking and conduct correlate, and suggest that dialogic pedagogy promoted coordination between ethical thinking and conduct.

The reverse trend observed in session 8 can be attributed to the heavier moderation of the teacher, as indicated by the fact that teacher turns constituted a significantly-larger volume of class dialogue in session 8, compared to session 3, and by the negative relationship between teacher involvement and students’ manifestations of +EoD, unearthed only in session 8. An additional factor that could have contributed to a negative relationship between DoE and +EoD in session 8 concerns the topic posed for discussion. While session 3 revolved around an ethical dilemma presented as a question, juxtaposing two stances (following social stereotypes versus staying true to oneself), session 8 concerned the conceptualisation of home/belonging. The former seems likelier to provide opportunities for more natural interaction than the latter, as was indeed the case.

Thus, the non-dilemmic topic posed for discussion in session 8 and its presentation, alongside the heavier involvement of the teacher, appear to have rendered inter-student interaction less natural, consequently decreasing instantiations of (+)EoD. The unnatural interaction, in turn, seems to necessitate heavier teacher involvement, which renders inter-student interaction even less natural. The nature of the interaction thus appears to hinge upon the topic posed for discussion, its presentation, and the extent of the teacher’s involvement in the discussion. This stresses the importance of true inter-student interaction when designing learning environments meant to induce students’ ethical thinking and behaviour.

The bonds (both positive and negative) found between ethical thinking and conduct in the two sessions contrast with the lack of correlation found between moral reasoning and action (Blasi, 1983; Talwar, 2011). Educational dialogues thus provide a suitable context for coordinating ethical thinking and action. Finallly, as far as ethical behaviour is concerned, teacher involvement should be limited for natural interaction to arise and for ethical learning to occur. The present case study nevertheless points at the potential of Dialogic Education in favouring a positive relation between students’ ethical thinking and behaviour, which is a new venue contrasting with the aforementioned lack of research on relations between them. The case study shows how values such as tolerance, inclusion and empathy can stem from interactions between students in the ideational as well as the behavioural realm. As such, it exemplifies the role of dialogic education in planting the seeds for democracy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Committee of Ethics in research at the Hebrew University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

BS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration. MB: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Methodology. NB: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by DIALLS project (Dialogue and Argumentation for cultural literacy learning in schools) funded in the framework of the Horizon 2020 Program, grant number 770045.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:12012P/TXT

2. ^https://ec.europa.eu/component-library/eu/about/eu-values/

3. ^Information can be found on the project website, at: https://dialls2020.eu/. A book has been published on the core research of the project, freely available on the Internet (see Maine and Vrikki, 2021a, 2021b).

References

Asterhan, C. S. C., and Schwarz, B. B. (2009). Transformation of robust misconceptions through peer argumentation. In Guided Transformation of Knowledge in Classrooms. (Eds.) B. B. Schwarz, T. Dreyfus, and R. Hershkowitz, (Routledge, Advances in Learning & Instruction series), pp. 159–172.

Brandel, N., Schwarz, B. B., Cedar, T., Baker, M. J., Bietti, L., Pallares, G., et al. (2024). Dialogue on ethics and ethics of dialogue: an exploratory study. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 2619–2654. doi: 10.1007/s10212-024-00856-z

Bakeman, R., and Gottman, J. M. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis. 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, M. J., Pallarès, G., Cedar, T., Brandel, N., Bietti, L., Schwarz, B., et al. (2023). Understanding the moral of the story: collaborative interpretation of visual narratives. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 39:100700. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2023.100700

Blasi, A. (1983). Moral cognition and moral action: a theoretical perspective. Dev. Rev. 3, 178–210. doi: 10.1016/0273-2297(83)90029-1

Hennessy, S., Rojas-Drummond, S., Higham, R., Marquez, A. M., Maine, F., Rios, R. M., et al. (2016). Developing a coding scheme for analysing classroom dialogue across educational contexts. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 9, 16–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.12.001

Killen, M., and Smetana, J. G. (2014). Handbook of moral development. 2nd Edn. New York: Psychology Press.

Maine, F., and Vrikki, M. (2021a). Dialogue for intercultural understanding: Placing cultural literacy at the heart of learning. Cham: Springer Nature.

Maine, F., and Vrikki, M. (2021b). “An introduction to dialogue for intercultural understanding: placing cultural literacy at the heart of learning” in Dialogue for intercultural understanding: Placing cultural literacy in the heart of learning. eds. F. Maine and M. Vrikki (Switzerland: Springer), 105–118.

Mercer, N., and Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. London: Routledge.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, C., and Resnick, L. (2008). Deliberative discourse idealized and realized: accountable talk in the classroom and in civic life. Stud. Philos. Educ. 27, 283–297. doi: 10.1007/s11217-007-9071-1

Rapanta, C., Cascalheira, D., Gil, B., Gonçalves, C., D’Jamila, G., Morais, R., et al. (2021). Dialogue and argumentation for cultural literacy learning in schools: multilingual data corpus (version 2) [dataset]. Zenodo.

Rouviere, N. (2018). Les composantes de la lecture axiologique [The components of axiological reading]. Reperes 58, 31–47. doi: 10.4000/reperes.1692

Talwar, V. (2011). “Moral behavior” in Encyclopedia of child behavior and development. eds. S. Goldstein and J. A. Naglieri (New York: Springer).

Turiel, E. (2002). The culture of morality: Social development, context, and conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

United Nations (1999). “Values and behaviours” framework. Available online at: https://hr.un.org/page/un-values-and-behaviours-framework-0 (Accessed April, 2025).

Keywords: dialogic education, ethical learning, classroom talk, democratic education, educational dialogue analysis

Citation: Schwarz BB, Baker M and Brandel N (2025) Seeds for democracy: understanding European values in educational dialogues. Front. Educ. 10:1662663. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1662663

Edited by:

Antonio Bova, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Susan Gardner, Capilano University, CanadaMarie-Christine Deyrich, Université Montesquieu, France

Copyright © 2025 Schwarz, Baker and Brandel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baruch B. Schwarz, YmFydWNoLnNjaHdhcnpAbWFpbC5odWppLmFjLmls

Baruch B. Schwarz

Baruch B. Schwarz Michael Baker

Michael Baker Noa Brandel

Noa Brandel