- 1Department of Economics and Sustainable Development, Harokopio University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 2Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 3Department of Education, School of Pedagogical and Technological Education, Athens, Greece

Background: Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) possess a unique range of strengths and challenges that can impact their employment opportunities and their vocational outcomes. Career counselors' role in helping individuals with ASD to their transition to employment has not been fully understood.

Objective: The aim of the current study was threefold: (a) to explore career counselors' views and attitudes toward employability skills in transition aged individuals with ASD in Greece; (b) to investigate the counselors' perception of the challenges they face when working with this population; and (c) to highlight career counselors' judgment of the suitability of professions for autistic individuals. For the first and second aim, we used an exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis.

Methods: An original 28-item survey was developed and disseminated to career counselors. A total of 92 professionals (62 women) took part in the study. All of them have been working as career counselors in the public or private sector. The factor structure of the survey's items was examined using quantitative data analysis, namely, an exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses factor method.

Results: According to the results of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, as well as descriptive statistics, we found that counselors agreed that social competence and high self-esteem can promote positive professional development in people with ASD, and that technology can have positive effects in their career. Over half of the counselors surveyed think there are professions particularly well-suited to individuals with ASD and they expressed a strong desire for ASD-specific training to be better prepared to meet the needs of their clients.

Conclusion: The results of the study represent the first step toward key variables in vocational guidance for individuals with ASD in Greece that can guide future research.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) represent a special category of developmental disabilities that share many similar characteristics. Specifically, individuals with an ASD have difficulties with social interaction and interpersonal communication, and may demonstrate unusual or repetitive patterns of behaviors and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The term ASD refers to a range of symptoms which can occur in any combination and can vary from very mild to quite severe (Sturm et al., 2004).

According to the DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), significant changes have been adopted in the diagnostic criteria of ASD. The neurodevelopmental disorders previously incorporated under the umbrella term of ASD (i.e., autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and childhood disintegrative disorders), have been eliminated. Also, the severity of the symptoms has been divided into three subcategories: Level 3 – “Requires very substantial support” due to severe social and behavioral challenges; Level 2 – “Requires substantial support” with notable difficulties; Level 1 – “Requires support” with mild difficulties (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Furthermore, difficulties in social contact and communication have been unified into a group currently termed as problems in social communication (Esler and Ruble, 2015). The aforementioned changes produced much public concern about the number of individuals qualifying for an ASD diagnosis. This is because psychologists, clinicians and other professionals in the field of ASD have found that rigid application of such criteria in practice does not meet their prognostic and treatment needs. The difficulties with the reliability of criteria for diagnosis have led clinicians continue to use the Asperger's diagnostic category, even informally, in their everyday practice (e.g., Huang et al., 2024; Jones et al., 2023; Motlani et al., 2022).

According to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), individuals with Asperger Syndrome have no intellectual disability or language delay. Their intelligence falls within the normal range and they exhibit greater adaptive functioning and social skills than other categories of ASD (Peristeri et al., 2017; Soulières et al., 2011). Also, the profile of a person with Asperger's syndrome is less likely to include motor mannerisms, which is a prominent feature in ASD, but he/she can have one or more circumscribed interests that consume a great deal of their time amassing information and facts (Attwood, 1997). Despite having intellectual and adaptive functioning strengths, autistic youth with Asperger Syndrome experience poor outcomes in adulthood (Barnhill, 2007; Howlin, 2003). Two significant transition “cliffs”, which current research identifies for youth with Asperger Syndrome, have been postsecondary and higher education. Autistic youth transitioning to the workforce has difficulty finding employment, particularly employment matched to their skills, interests and level of education.

Career counselors are professionals who collaborate with individuals at different points in their career paths—students deciding on a profession, adults looking to switch jobs, or professionals aiming to progress their career direction. The profession of career counselor/vocational guidance in Greece can be practiced at different levels of hierarchy and in various sectors (education, training, employment, social inclusion) (Vlachaki et al., 2024). Career counselors can play a pivotal role in supporting students with ASD to make the transition from education to employment. Studies which focus directly on how counselors perceive autistic people's strengths and employability are rare. (Bölte 2021) editorial as well as Nicholas et al.'s (2015) study stand out as the most relevant evidence of career counselors' perceptions. (Bölte 2021) suggests that career counseling catered to the needs of individuals with ASD can improve post-secondary outcomes by encouraging self-awareness, job preparation, and workplace flexibility. Despite efforts to develop services and supports available to youth with ASD before leaving high school, their transition to the work field creates unique challenges because of limited or non-existent career planning and preparation services in many countries (Hendricks, 2010; Howlin and Moss, 2012; Shattuck et al., 2012; Taylor and Seltzer, 2011). Even when access to career counseling is secured for autistic youth and their families, barriers to providing transition-related support are framed as stemming from deficit ideologies, such as professionals' own lack of knowledge of the strengths and needs of autistic individuals (Halder et al., 2024). These barriers may deprive individuals with ASD of the opportunity to improve their quality of life, social opportunities, and financial stability through competitive integrated employment (Jahoda et al., 2009). According to (Nicholas et al. 2015), successful career counselors for students with ASD take a person-centered approach, stressing customized planning that takes into account the student's strengths and weaknesses. Career counselors can act as advocates and mentors who help close the gap between school and employment by providing individualized support, interview preparation, and evidence-based skill-building strategies. Based on these findings, and given the absence of relevant research in the Geek context, we decided to focus on career counselors' perspectives and views instead of capturing perceptions of instructors or employers.

Career counseling services for autistic individuals

Employment is a socially normative activity critical to an individual's autonomy and quality of life, as it enhances social status and financial independence (Saleh and Bruyère, 2018; Shattuck and Roux, 2014; Walsh et al., 2014). Yet, employment rates for adults with ASD remain below 20% despite concerted policy, advocacy, and funding initiatives (Chen et al., 2015). Effective career counseling is among the most robust predictors of future employment for individuals with ASD (Wehman et al., 2014). Supported employment, including matching individual profiles to vocational environments, and ongoing support, like job coaching, can address this challenge, increasing employment rates and retention in paid employment (Hendricks, 2010). In a review of vocational interventions for youth and adults with ASD, (Lee and Carter 2012) stress that the employment outcomes of individuals with ASD can be substantially improved by planned interventions implemented by career counselors who will locate appropriate job options in the community, learn the skills needed for the job, and provide education to coworkers about ASD and any special needs of the person on the spectrum. Especially, early career coaching experiences can help autistic students clarify their professional interests for future job preparation, while individuals not engaged in job counseling early in adolescence are unlikely to transition to independent employment or an appropriate educational placement later in early adulthood (Lee and Carter, 2012; Migliore et al., 2014; Schaller and Yang, 2005).

Though career counseling has been shown to act as a crucial facilitator in assisting autistic individuals overcome personal and work-related barriers (e.g., accessing job accommodations, modifying tasks, developing compensatory strategies, delivering behavioral interventions, skills training), there is a noticeable gap about practitioners' perceptions of the vocational skills of individuals with ASD or/and of their own efficacy in identifying and/or resolving individual and vocational factors that impact the stability of employment of individuals with ASD over time. More specifically, there is research (Brock et al., 2014; Murza, 2016) noting that transition teachers and adult service providers feel poorly prepared to meet the career development needs of individuals with ASD. While job counselors in Murza's (2016) multisite study in the USA has reported interpersonal skills impairments as the most important barrier to successful employment in ASD, career counselors were overwhelmingly interested in receiving additional training and resources, while they also highlighted that community resources are insufficient.

(Bölte 2021) notices that there is very little research examining the matching of autistic characteristics to specific job requirements and/or associated risks on wellbeing. Throughout the existing literature, employment research has focused on individual and social characteristics in individuals with ASD that influence job-seeking processes (e.g., McMahon et al., 2008; Zalewska et al., 2016), without, however, empirically investigating the resources that may support autistic job seekers in locating fulfilling work opportunities, including efficient job counseling. Bölte et al.'s (2025) recent scoping review about career guidance with neurodivergent individuals underscores that matching between autistic individuals' unique skills and job demands, as well as collaborating with other support systems and professions (e.g., school health team) to uncover attributes of the neurodivergent individual are the core concerns of job counselors working with people with ASD.

The overall evidence shows that there is not much research serving as a good backbone for developing vocational understanding and career guidance for people with ASD. This is especially true for the Greek society where it remains unclear how vocational counselors provide support to individuals with ASD transitioning to adulthood, as well as how vocational rehabilitation counselors perceive working with clients with ASD. Transition to employment or/and barriers to employment for individuals with ASD have not been yet identified as a priority research area in Greece, although the prevalence of ASD in Greek-speaking children aged 10 and 11 years in 2019 was 1.2% (Thomaidis et al., 2020), and the youth unemployment rate at the same period was 43.2%, namely almost the triple comparing to the EU one (Dimian et al., 2018). (Kossyvaki 2021) underscores that Greek practitioners in the field of ASD still hold a number of misconceptions about weaknesses and strengths in autism, and stress the need for more training and coaching to promote the life skills and professional wellbeing of individuals on the spectrum. In 2023, an employment integration program for people on the autism spectrum was administered for the first time to highlight the unique skills of people with ASD, and to train potential employers overcome their hesitancy and provide practical support to autistic individuals within the work environment (https://www.latsis-foundation.org/eng/grants/jobslink-employment-integration-programme-for-people-on-the-autism-spectrum). However, the outcomes of this program in the Greek society are still unknown.

Aims of the study

The extant literature reviewed so far identifies that, though career counselors' view of autistic clients' abilities and job readiness is crucial for developing more inclusive career services and employment success for these individuals, the lack of empirical evidence on how career counselors perceive their role and self-efficacy when providing guidance to autistic young people creates a subsequent gap in improving career counseling services to these individuals.

The aim of the current study is threefold: (a) identify career counselors' perceptions of vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD in their transition to employment in the Greek context; (b) highlight career counselors' perceptions of self-efficacy when providing services to autistic individuals; and (c) explore career counselors' views of suitability of professions for people with ASD. Data was collected through a questionnaire survey, and exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were tested to evaluate the factor structure of the questionnaire in a cohort of 92 career counselors in Greece.

Method

Participants

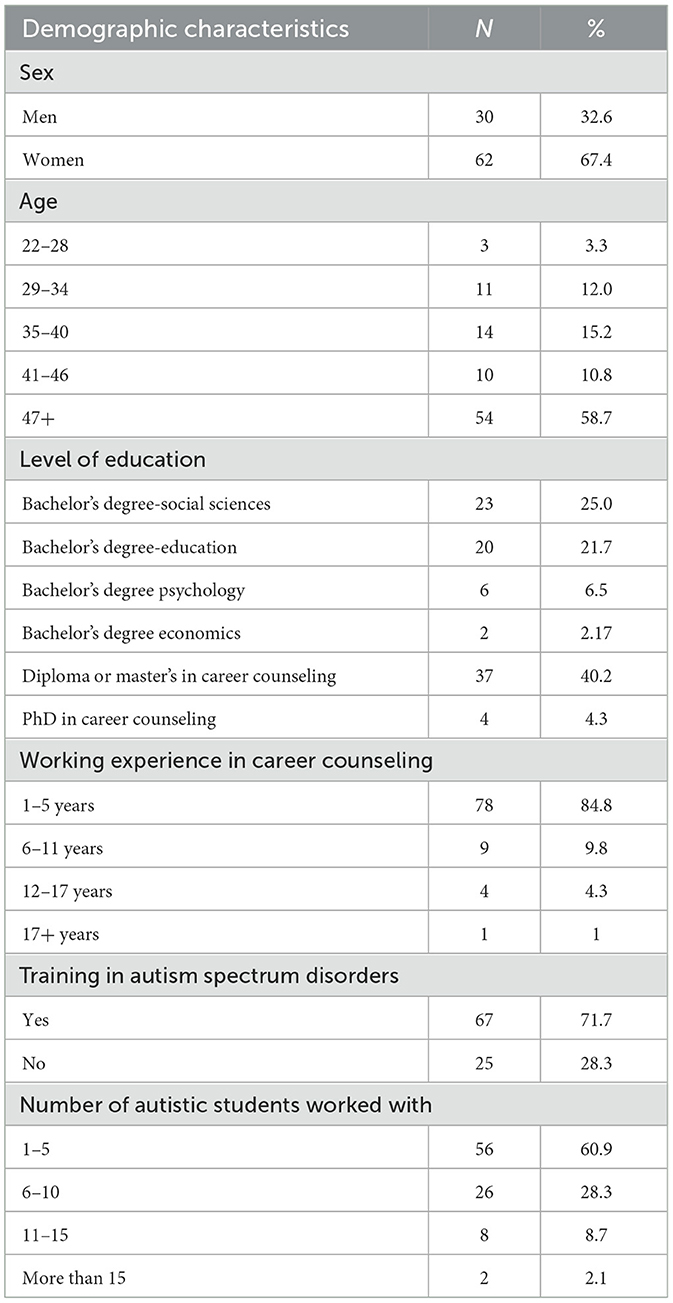

The study included 92 professionals (62 women) who have been working as career counselors in the public or private sector in Athens, Greece. Fifty-one participants (55.4%) had a Bachelor degree in a relevant discipline (education, social sciences, psychology and economics). The rest of the participants (N = 41) (44.5%) had pursued postgraduate studies (either master's or PhD degree) in vocational guidance. Participants were invited to participate in the study by the official Association of Vocational Guidance and Counseling in Greece, which has been established by the Greek Ministry of Education in 2008, or were informed about the research by the social media. All career counselors reported having offered counseling services to autistic students at the time of testing. Participants' demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Instrument

A questionnaire survey was chosen as a suitable research method to collect information on current views and practices of career (vocational) counselors with youth with ASD. The questionnaire was created with the intent of exploring career counselors' perceptions of vocational and interpersonal skills, job specific characteristics, obstacles to employment and types of transition support for individuals with ASD. In order to address these domains, the questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part (part A:7 items) collected background information on the career counselor participating in the study, such as age, gender, and educational status. The second part (part B:13 items) explored participants' perceptions of the vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD. Sample items included: “People's self-esteem can affect their adaptation to the workplace” (item 16), “It is unfair to other workers that people with ASD have special support in the workplace” (item 19). The third part (part C:8 items) referred to counselors' beliefs about the challenges they face when working with individuals with ASD. Sample items included: “I feel effective in designing a transition program for students with ASD” (item 28), “I can cope with psychological or other adaptation problems of individuals with ASD” (item 31). Respondents' answers were given on a five-point Likert scale (1-Strongly disagree; 2-Disagree; 3-Undecided; 3-Agree; 5-Strongly agree). Finally, the questionnaire also included two individual Yes/No questions asking career counselors to judge whether professions exist that are more suitable or inappropriate for people with ASD, and also cite examples of professions that were considered highly appropriate and prohibitively difficult for these individuals, respectively.

Pilot testing/feedback

The questionnaire was originally developed by the researchers in line with the specific cultural and contextual characteristics of the Greek context that may not be sufficiently represented by tools that have been previously developed. A draft version of the questionnaire survey was shared with five counselors-members of the Greek Association of Vocational Guidance and Counseling, and with five mothers of adolescents with ASD to review it in terms of content, wording, and layout. After analyzing the pilot study responses, we adjusted wording in three items for better clarity, and reduced the sentence length to two items. The final version was then assessed by calculating Cronbach's a index (0.72) for Part B and C of the questionnaire. Part A is demographic so the Cronbach a cannot be calculated. The Cronbach's a index was satisfactory, given the small size sample of the pilot study (n = 10). This was due to practical factors such as ease of access to the sample, and it can be taken as a limitation.

Procedure

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and ethics committee of the Greek Association of Vocational Guidance and Counseling. After approval, an information leaflet outlining the study was initially sent to the association to recruit participants. The link to the survey was distributed through postings on social media and mailing lists. Respondents received no incentive to participate. Information on the total number of people who were reached through the association and social media is not available. The anonymity of the participants and the possibility to withdraw from the research at any time were guaranteed. The research spanned 3 months, beginning in early March and concluding at the end of May 2024. The first 2 weeks were dedicated to piloting the survey instrument. This was followed by the main phase of data collection, which lasted 8 weeks. The final phase (2 weeks) focused on ensuring data completeness and setting the analysis plan. While collecting the data, 95 survey responses were submitted. Of those responses, three were omitted from the analysis because no questions were answered on the survey. The remaining 92 responses were included in the analysis.

Data analysis

Through the use of exploratory factor analysis, we evaluated the construct validity of the questionnaire and the extraction of independent variables by using scores obtained from a sample of 92 career counselors who had working experience with autistic individuals in Greece. The questionnaire was purported to measure the construct of career counselors' views of working with autistic individuals through the following dimensions: perceptions of general skills in ASD, perceptions of professional skills in ASD, perceptions of support for individuals with ASD in the workplace, and beliefs about the challenges career counselors face when working with individuals with ASD. We examined the theoretical assumptions underlying the development of the questionnaire in exploratory factor analyses, using the Varimax method of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the extraction of the axes (Loukaidis, 2012), which revealed a three-factor solution for Part B, and a single overall factor for Part C. Varimax rotation reduced the number of the questionnaire's items that loaded on multiple factors (Wood et al., 1996), and the final solution represented uncorrelated components. We should underline the fact that the sample size of the current study (n = 92 career counselors) is small for factor analytic work, making drawing conclusions from these analyses tenuous; however, factor analyses based on smaller or equally-sized groups in previous research using questionnaires in ASD (e.g., Brinkley et al., 2007; Chou et al., 2017; Pandolfi et al., 2009) have been shown to be interpretable. Quantitative data was next summarized and averaged for parts B and C of the questionnaire. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0). Finally, the percentages of career counselors' positive answers in the categorical yes/no format of the questionnaire, i.e., the two questions about professions that are considered to be (in)appropriate for people with ASD, were also computed. In addition, the occupations obtained from the above two questions are provided in a list format in the Results.

Results

First aim of the study: identifying Greek career counselors' perceptions of vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD

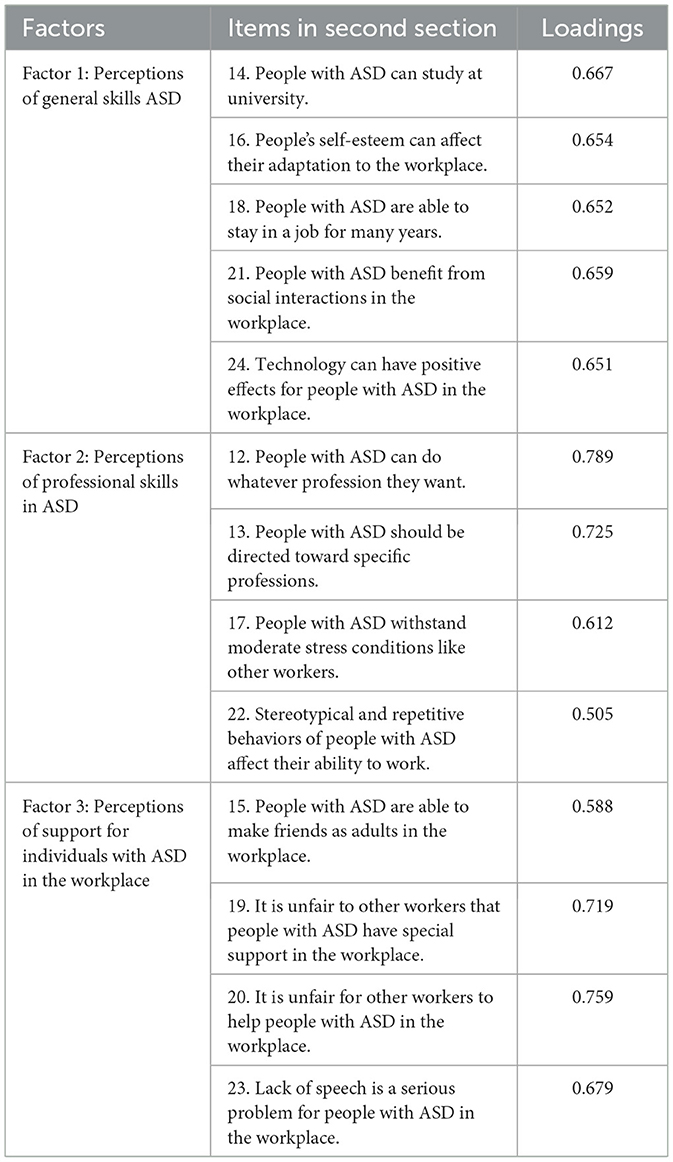

To address the first aim of the study, our first set of analyses has used as input the items of Part B in the questionnaire that explored participants' perceptions of the vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy of 0.847 and Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 = 297.721, p < 0.001) indicated that the exploratory factor analysis was possible. In examining the results of Table 2, the items were clearly grouped under three factors, namely, perceptions of general skills in ASD, perceptions of professional skills in ASD, and perceptions of support for individuals with ASD in the workplace. The three factors accounted for about 48% of the variance.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analyses of the 13 items of the questionnaire's Part B on Greek career counselors' perceptions of the vocational and interpersonal skills in ASD.

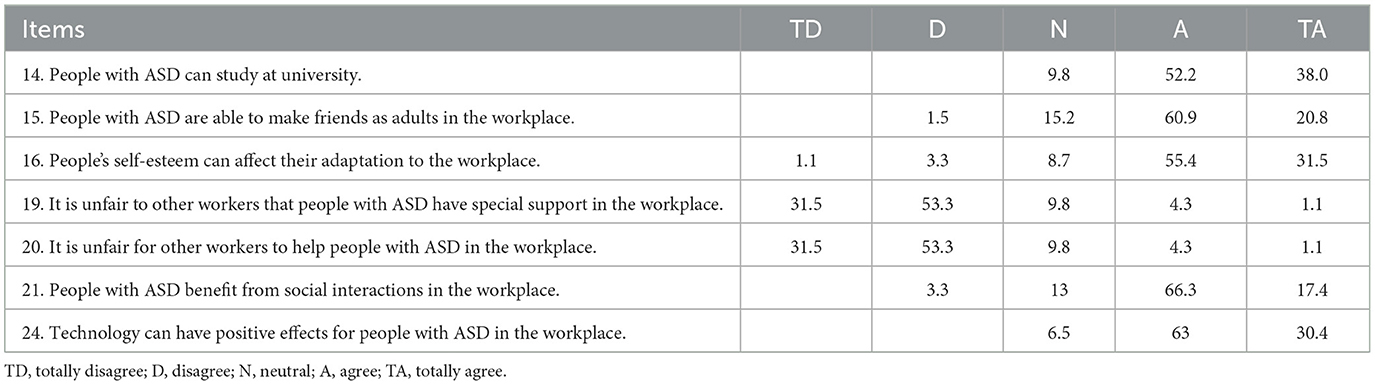

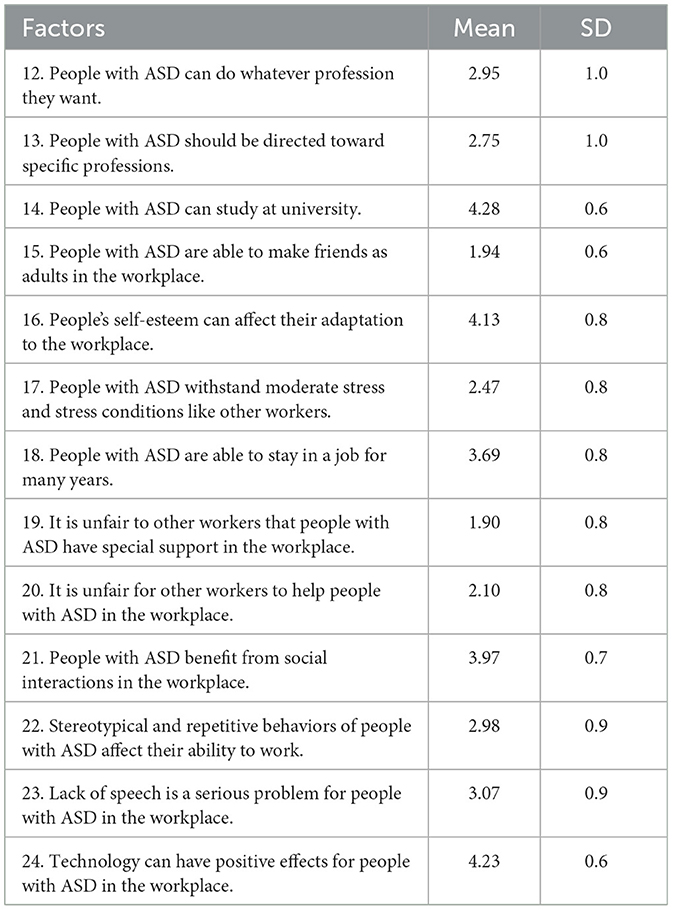

We next provide descriptive statistics summarizing career counselors' response rates based on the answers given in Part B of the questionnaire that focused on their perceptions of the vocational and interpersonal skills of autistic individuals (Table 3). Respondents seemed to agree that people with ASD can study at the university (M = 4.28, SD = 0.6) (item 14), and that technology can have positive effects on people with ASD in the workplace (M = 4.23, SD = 0.6) (item 24). The perception that self-esteem can affect their adjustment in the workplace also had a high agreement rate (Mean = 4.13, SD = 0.8) (item 16). Career counselors expressed low confidence in the notion that providing special support to workers with ASD is unfair to other employees (M = 1.9, SD = 0.8) (item 19) and that people with ASD are able to make friends (M = 1.94, SD = 0.6) (item 15). The perception that it is unfair for other employees to help people with ASD in the workplace had a relatively low agreement rate (M = 2.10, SD = 0.8) (item 20). Career counselors expressed relatively high confidence in the idea that workplace social interactions are beneficial for people with ASD (M = 3.97, SD = 0.9 (item 21).

Table 3. Descriptive measures (means and standard deviations) of career counselors' perceptions of the vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD (Part B of the questionnaire).

Table 4 below presents response distribution for selected items of Table 3, focusing on the vocational and interpersonal skills of individuals with ASD.

Second aim of the study: identifying Greek career counselors' perceptions of self-efficacy when providing services to autistic individuals

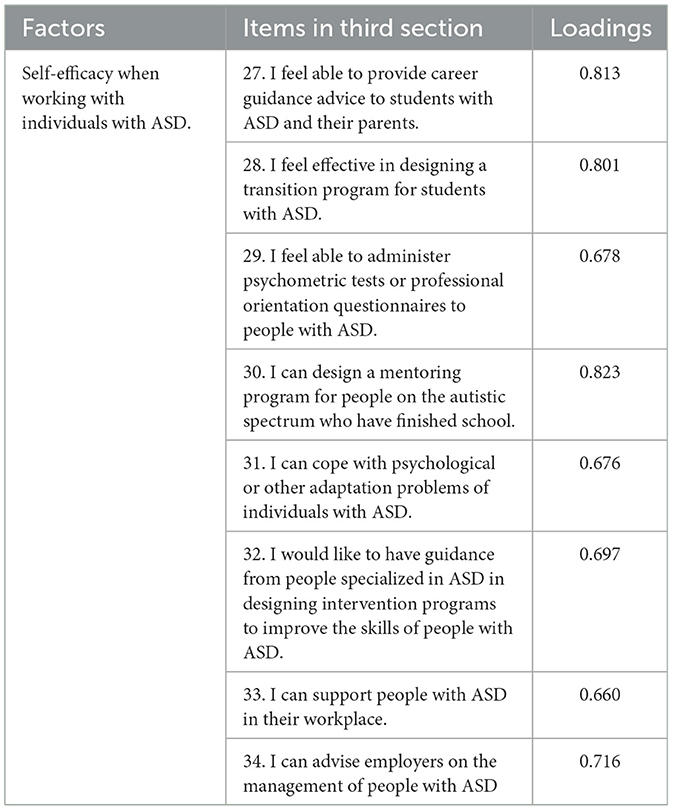

To address the second aim of the study, our analyses have focused on Part C of the questionnaire, which referred to career counselors' beliefs about the challenges they face when working with individuals with ASD. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was high (0.854), while Bartlett's test of sphericity showed significant correlations between the variables (χ2 = 301.088, p < 0.001). The exploratory factor analysis yielded a single overall factor that accounted for about 64 % of total variance (χ2/df = 2.02; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.072; SRMR = 0.061). Table 5 below presents the items included under the single factor that centered on career counselors' self-efficacy when working with individuals with ASD. The Cronbach's a was calculated (a = 0.800).

Table 5. Exploratory factor analyses of the 8 items of the questionnaire's Part C on Greek career counselors' attitudes beliefs about challenges they meet when working with individuals with ASD.

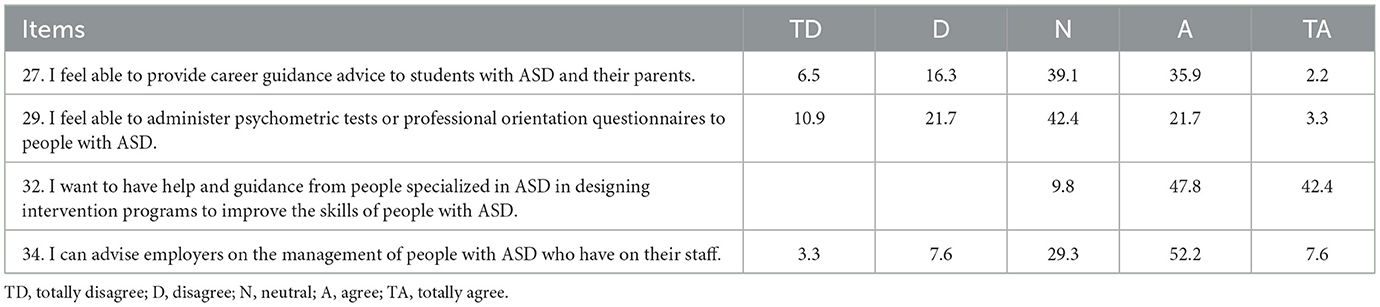

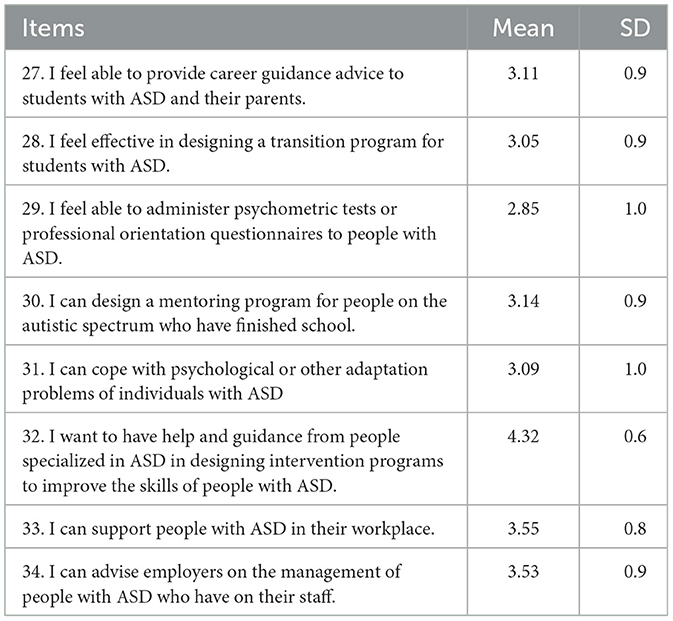

We next provide descriptive statistics summarizing response rates based on answers that focused on the career counselors‘ beliefs about their self-efficacy when working with individuals with ASD, and how prepared they felt to support them (see Table 6). Respondents expressed low confidence in administering psychometric tools (M = 2.85, SD = 1.0) (item 29), but a strong desire for ASD-specific training (M = 4.32, SD = 0.6) (item 32). Overall, it seems that career counselors' self-perceived readiness to offer support services to people on the spectrum received rather moderate agreement rates (items 27, 28, 33, and 34).

Table 6. Descriptive measures (means and standard deviations) of career counselors' self-efficacy when working with individuals with ASD (Part C of the questionnaire).

Table 7 below presents response distribution for selected items of Part C of the questionnaire focusing on the career counselors' beliefs about their self-efficacy.

Third aim of the study: exploring career counselors' views of suitability of professions for people with ASD

To address the third aim of the study, we computed career counselors' positive and negative response rates in the Yes/No questions of the questionnaire. The positive answer rate for the existence of professions that were more suitable than others for people with ASD was 53.8%. Examples of jobs that were considered appropriate are cited below in order of preference: information technology, sciences, mathematics, engineering, and music, and, secondarily, those that follow a repetitive routine or are more practical: gardener, chef, librarian, storekeeper, museum employee, and accountant. On the other hand, the positive answer rate for professions that were judged to be inappropriate for people with ASD was 46.2%. The jobs that have been characterized as being inappropriate for people with ASD were mostly professions that require social skills or/and human contact, including those of lawyer, doctor, teacher, pilot, diplomat, psychologist, as well as hazardous jobs, such military, fire worker and policeman. The ranking has been based on the participants‘ responses.

Discussion

The present study has focused on career counselors' views about general and professional skills of individuals with ASD, as well as their beliefs about the challenges they face when working with these individuals in the Greek context. Notably, the current research is the first to offer insights into career counselors' working experiences with autistic individuals in the Greek context. According to the study's findings, high rates were obtained on career counselors' awareness of autistic individuals' potential to pursue studies at a tertiary institution, as well as of the risk factors, like low self-esteem or weak social connections that may hinder their personal and employment skill development. The analysis of the data also indicated several challenges for career counselors' self-efficacy, such as the lack of resources and training programs to incorporate opportunities for expanding their knowledge and practical experience with individuals with ASD. Another theme that has emerged from career counselors' responses to the questionnaire of the current study was their misconception of how cognitive traits in the spectrum match professional fields, and the fact that the counselors' view of the suitability of professions for people with ASD tend to cluster around certain characteristics that individuals with ASD possess, while neglecting others. These insights may provide useful illustrations for understanding the challenges that career counselors face when working with individuals with ASD, as well as for highlighting the need to implement training programs to improve career guidance use.

More specifically, the first aim of the study targeted counselors' views of the general skills possessed by people with ASD, such as being able to study at a tertiary institution, the need for jobs to be tailored-made to the cognitive and social profile of these individuals, as well as the contribution of their aptitude in technology to the enhancement of their integration into the workplace and professional development, in general. Career counselors seem to believe that social competence and high self-esteem can promote positive developmental cascades for professional development in people with ASD, and that technology can have positive effects in their career (see Cederlund et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2015 for similar results).

Another dimension that has emerged regarding career counselors perceived knowledge of autistic individuals' vocational skills is the importance of supporting people with ASD in the workplace. Response rates indicated that the assistance given by both employers and employees to people with ASD, as well as the creation of ASD-friendly workplaces, is significant to the employment achievements of individuals with ASD. Relevant literature suggests that supported employment and planned vocational interventions have positive effects on the employability of individuals with ASD (Lee and Carter, 2012; Migliore et al., 2014). Employees with ASD who find themselves in supportive work environments and are socially connected to their employer and colleagues will consequently present work motivation which is self-determined and volitional (Scott et al., 2019; Solomon, 2020). On the other hand, negative societal attitudes toward ASD, as well as employers' concerns about supervision, productivity or/and the ongoing assistance seem to have negative effects on employment rates, motivation and subsequently productivity for people with ASD (Gerhardt et al., 2014).

The second objective of the study was to pinpoint domains that career counselors perceived as being barriers to their self-efficacy in vocationally guiding autistic individuals in the Greek context. Importantly, one of the major challenges identified by career counselors working with people with ASD in Greece relates to the lack of adequate training on supporting the vocational guidance for the specific neurodivergent population. Career counselors in Greece seem to experience formidable challenges supporting autistic individuals' transition to the workforce, due to lack of training and lack of access to resources. Specifically, one of these challenges is the limited understanding and familiarization with psychometric tools that would enable to them to gain fine-grained knowledge of the individual profiles of the persons with ASD. Many counselors feel unprepared to address the specific needs and challenges associated with ASD, leading to feelings of uncertainty. Low readiness to offer specialized vocational support services to these individuals does not manifest uniquely in the Greek context.

An effective model in the field of career guidance is the use of blended learning modules that combine self-paced content with one-on-one sessions to reinforce concepts like workplace communication, social skills development, and job-specific expectations for ASD people. Additionally, coordinated partnerships between counselors and employers can align vocational goals with workplace realities. Counselors should also receive ongoing supervision and ASD-specific training, including mentorship from neurodiversity-informed professionals. For practitioners, programs like “Ambitious about Autism: understanding Autism for Careers and Employability Professionals” offer short, autism-informed training. Career counselors need to be trained in autism adaptations and soft-skills capacity to work successfully with their clients. A co-production model including employers, staff, counselors and young autistic people to create inclusive work environments is a good practice which aligns with the autistic community's call for greater involvement in employment-related initiatives (Murza, 2016).

The final aim of the study explored career counselors' views of the suitability of professions individuals with ASD. We found that the counselors seemed to be hesitant about whether some professions may be particularly demanding for people with ASD, yet, they tended to recognize that it is difficult for them to keep a job for a long period. Notably, career counselors' views of desirable workplaces for individuals with ASD seem to lump this diverse population into a homogeneous sample of individuals characterized by specific cognitive traits. According to the counselors' responses, people with ASD are fitted to specific professions that seem to align with ASD-specific traits, like rrestricted interests and stereotypes, which is further corroborated by the examples of jobs regarded as optimal for people with ASD, such as information technology, gardener, chef, librarian and accountant. There is a common assertion that people with ASD are more fitted for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) sectors (e.g., Bury et al., 2020; Spek and Velderman, 2013), due to preference for detail-oriented tasks or a tendency toward systemizing (Baron-Cohen et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2009). However, the specific approach could inadvertently reinforce stereotypes. Recent literature suggests that ASD is a highly heterogeneous condition (Peristeri and Andreou, 2024; Peristeri et al., 2022). The unique cognitive characteristics of individuals with ASD indicate that a uniform method for education or job placements is probably not effective, highlighting the need for tailored support (Bölte, 2021). Greek counselors' tendency to associate ASD with certain job types may stem from lack of exposure to neurodiverse employment success stories. There is research showing that job interests of people with ASD expand to human and social sciences and creative fields (Kirchner et al., 2016). The specific studies offer an in-depth understanding of employment experiences of autistic professionals in performing arts (Buckley et al., 2022) and teaching (Wood and Happé, 2023), further suggesting that broad participation of employees with ASD in various job-market sectors is feasible.

The overall results of the study show that career counselors working with individuals with ASD transitioning to the workforce face a number of unique challenges that may serve as intervention targets to increase the likelihood that individuals with ASD engage in vocational activities. Career counselors have identified their need for more training and resources to boost their efficiency to support this specific population. The findings also inform the implementation of evidence-based practices in vocational rehabilitation services that will support the soft skills difficulties (e.g., social competence, emotion regulation, self-esteem) that are associated with poor employment outcomes for individuals with ASD. Work-related supports should thus target at helping individuals with ASD become familiar with the workplace, its routines and expectancies, as well as improving employment prospects through pre-employment training. The results of the current study represent the first step toward key variables in vocational guidance for individuals with ASD in Greece that can guide future research, as well as inform systemic policy and practices.

Limitations and conclusions

Our study has several strengths and limitations. To our knowledge, this is the first study that assesses career counselors' perceptions and beliefs about ASD people's opportunities to find and maintain a job in Greece. The role of career counseling in supporting persons with ASD is still evolving in Greece, where several reports outline the limited employment opportunities for people with ASD (Dimian et al., 2018; Center for European Constitutional Law, 2014). If career counselors recognize and combat their misconceptions about the capabilities of autistic people, they may implement evidence-based practices to support them on progressing their career directions. Furthermore, on the societal level, the findings of the study can impact public policy by offering an evidence base to bridge the gap between research and vocational services for individuals with ASD in Greece, raising awareness among employers and counselors. On the other hand, this study is not without limitations. An important limitation is the small sample size (N = 95) that calls for cautiousness in interpreting the findings. Furthermore, the sample only included participants from one area of Greece (i.e., Athens), which limits group diversity and its representativeness. This could therefore potentially affect the feasibility to generalize the results to the whole populations of career counselors working with individuals with ASD. Future directions include a national survey that may develop educational materials that will dispel myths about ASD by highlighting the potentials of autistic individuals, and translate the findings of large-scale reports into national policy. This study also provides a starting point for further research conceptualizing career as a lifelong journey and keeping in mind that work contributes to the improvement of the quality of life of individuals, as it strengthens their autonomy and social integration.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Association of Vocational Guidance and Counseling in Greece. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AS: Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. EP: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Data curation, Methodology. RK: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 5th edn. Text revision. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Attwood, A. (1997). Asperger's Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals. London; Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Barnhill, A. C. (2007). At Home in the Land of Oz: Autism, My Sister, and Me. London; Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Ashwin, C., Tavassoli, T., and Chakrabarti, B. (2009). Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. Biol. Sci. 364, 1377–1383. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0337

Bölte, S. (2021). We believe in good jobs, fair jobs, dignifying jobs that give you a good sense of identity: career and job guidance counseling in autism. Autism 25, 857–861. doi: 10.1177/1362361321990325

Bölte, S., Carpini, J. A., Black, M. H., Toomingas, A., Jansson, F., Marschik, P. B., et al. (2025). Career guidance and employment issues for neurodivergent individuals: a scoping review and stakeholder consultation. Hum. Resour. Manage. 64, 201–227. doi: 10.1002/hrm.22259

Brinkley, J., Nations, L., Abramson, R. K., Hall, A., Wright, H. H., Gabriels, R., et al. (2007). Factor analysis of the aberrant behavior checklist in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 1949–1959. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0327-3

Brock, M. E., Huber, H. B., Carter, E. W., Juarez, A. P., and Warren, Z. E. (2014). Statewide assessment of professional development needs related to educating students with autism spectrum disorder. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabilities 29, 67–79. doi: 10.1177/1088357614522290

Buckley, E., Pellicano, E., and Remington, A. (2022). “Knowing That I'm Not Necessarily Alone in My Struggles”: UK autistic performing arts professionals' Experiences of a mentoring programme. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 5451–5470. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05394-x

Bury, S. M., Hedley, D., Uljarević, M., and Gal, E. (2020). The autism advantage at work: a critical and systematic review of current evidence. Res. Dev. Disabilities 105:103750. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103750

Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., and Gillberg, C. (2010). Asperger syndrome in adolescent and young adult males. Interview, self-and parent assessment of social, emotional, and cognitive problems. Res. Dev. Disabilities 31, 287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.09.006

Center for European Constitutional Law (2014). Discrimination and Obstacles to the Professional Rehabilitation of Disabled University Graduates. (Action 1). Athens: Center for European Constitutional Law[in Greek].

Chen, J. L., Leader, G., Sung, C., and Leahy, M. (2015). Trends in employment for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a review of the research literature. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2, 115–127. doi: 10.1007/s40489-014-0041-6

Chou, Y. C., Wehmeyer, M. L., Shogren, K. A., Palmer, S. B., and Lee, J. (2017). Autism and self-determination: factor analysis of two measures of self-determination. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabilities 32, 163–175. doi: 10.1177/1088357615611391

Dimian, G. C., Aceleanu, M. I., Ileanu, B. V., and Şerban, A. C. (2018). Unemployment and sectoral competitiveness in Southern European Union countries. Facts and policy implications. J. Bus. Econ. Manage. 19, 474–499. doi: 10.3846/jbem.2018.6581

Esler, A. N., and Ruble, L. A. (2015). DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder with implications for school psychologists. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 3, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2014.890148

Gerhardt, P. F., Cicero, F., and Mayville, E. (2014). “Employment and related services for adults with autism spectrum disorders,” in Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders (New York, NY: Springer New York), 105–119. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0506-5_6

Halder, S., Bruyere, S. M., and Gower, W. S. (2024). Understanding strengths and challenges of people with autism: insights from parents and practitioners. Int. J. Dev. Disabilities 70, 74–88. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2022.2058781

Hendricks, D. (2010). Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorders: challenges and strategies for success. J. Vocational Rehabil. 32, 125–134. doi: 10.3233/JVR-2010-0502

Howlin, P. (2003). Outcome in high-functioning adults with autism with and without early language delays: implications for the differentiation between autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 33, 3–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1022270118899

Howlin, P., and Moss, P. (2012). Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Can. J. Psychiatry 57, 275–283. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700502

Huang, Y., Arnold, S. R. C., Foley, K. R., and Trollor, J. N. (2024). Experiences of support following autism diagnosis in adulthood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 54, 518–531. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05811-9

Jahoda, A., Selkirk, M., Trower, P., Pert, C., Kroese, B. S., Dagnan, D., et al. (2009). The balance of power in therapeutic interactions with individuals who have intellectual disabilities. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 48, 63–77. doi: 10.1348/014466508X360746

Jones, A., Rogers, K., Sullivan, K., and Viljoen, N. (2023). An evaluation of the diagnostic validity of the structured questionnaires of the adult Asperger's assessment. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 2636–2646. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05544-9

Kirchner, J., Ruch, W., and Dziobek, I. (2016). Brief report: character strengths in adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual impairment. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 3330–3337. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2865-7

Kossyvaki, L. (2021). Autism education in Greece at the beginning of the 21st century: reviewing the literature. Support Learn. 36, 183–203. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12350

Lee, G. K., and Carter, E. W. (2012). Preparing transition-age students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders for meaningful work. Psychol. Sch. 49, 988–1000. doi: 10.1002/pits.21651

Loukaidis, K. (2012). Statistical Data Processing Using IBM SPSS Statistics 19. Nicosia: Epifaniou Editions [in Greek].

McMahon, B. T., Roessler, R., Rumrill, P. D., Hurley, J. E., West, S. L., Chan, F., et al. (2008). Hiring discrimination against people with disabilities under the ADA: characteristics of charging parties. J. Occup. Rehabil. 18, 122–132. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9133-4

Migliore, A., Butterworth, J., and Zalewska, A. (2014). Trends in vocational rehabilitation services and outcomes of youth with autism: 2006–2010. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 57, 80–89. doi: 10.1177/0034355213493930

Motlani, V., Motlani, G., Thool, A., and Thool, A. R. (2022). Asperger syndrome (AS): a review article. Cureus 14:e31395. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31395

Murza, K. A. (2016). Vocational rehabilitation counselors' experiences with clients diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: results of a national survey. J. Vocational Rehabil. 45, 301–313. doi: 10.3233/JVR-160831

Nicholas, D. B., Attridge, M., Zwaigenbaum, L., and Clarke, M. (2015). Vocational support approaches in autism spectrum disorder: a synthesis review of the literature. Autism 19, 235–245. doi: 10.1177/1362361313516548

Pandolfi, V., Magyar, C. I., and Dill, C. A. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis of the child behavior checklist 1.5–5 in a sample of children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 986–995. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0716-5

Peristeri, E., and Andreou, M. (2024). Intellectual development in young children with autism spectrum disorders: a longitudinal study. Autism Res. 17, 543–554. doi: 10.1002/aur.3089

Peristeri, E., Andreou, M., and Tsimpli, I. M. (2017). Syntactic and story structure complexity in the narratives of high-and low-language ability children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 8:02027. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02027

Peristeri, E., Silleresi, S., and Tsimpli, I. M. (2022). Bilingualism effects on cognition in autistic children are not all-or-nothing: the role of socioeconomic status in intellectual skills in bilingual autistic children. Autism 26, 2084–2097. doi: 10.1177/13623613221075097

Saleh, M., and Bruyère, S. M. (2018). Leveraging employer practices in global regulatory frameworks to improve employment outcomes for people with disabilities. Soc. Inclusion 6, 18–28. doi: 10.17645/si.v6i1.1201

Schaller, J., and Yang, N. K. (2005). Competitive employment for people with autism: correlates of successful closure in competitive and supported employment. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 49, 4–16. doi: 10.1177/00343552050490010201

Scott, M., Milbourn, B., Falkmer, M., Black, M., Bölte, S., Halladay, A., et al. (2019). Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Autism 23, 869–901. doi: 10.1177/1362361318787789

Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P. R., Wagner, M., Taylor, J. L., et al. (2012). Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 129, 1042–1049. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2864

Shattuck, P. T., and Roux, A. M. (2014). Autism: moving toward an innovation and investment mindset. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 698–699. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.585

Simmons, D. R., Robertson, A. E., McKay, L. S., Toal, E., McAleer, P., Pollick, F. E., et al. (2009). Vision in autism spectrum disorders. Vision Res. 49, 2705–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.08.005

Solomon, C. (2020). Autism and employment: implications for employers and adults with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 4209–4217. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04537-w

Soulières, I., Mottron, L., Giguère, G., and Larochelle, S. (2011). Category induction in autism: slower, perhaps different, but certainly possible. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 64, 311–327. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2010.492994

Spek, A. A., and Velderman, E. (2013). Examining the relationship between autism spectrum disorders and technical professions in high functioning adults. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 606–612. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.002

Sturm, H., Fernell, E., and Gillberg, C. (2004). Autism spectrum disorders in children with normal intellectual levels: associated impairments and subgroups. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 46, 444–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00503.x

Taylor, J. L., and Seltzer, M. M. (2011). Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 566–574. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3

Thomaidis, L., Mavroeidi, N., Richardson, C., Choleva, A., Damianos, G., Bolias, K., et al. (2020). Autism spectrum disorders in Greece: nationwide prevalence in 10–11 year-old children and regional disparities. J. Clin. Med. 9:2163. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072163

Vlachaki, F., Varvitsioti, R., and Theodoridi, E. (2024). Professional Profile-Career Counselor-Vocational Guidance. Athens: E.O.P.P.E.P.

Walsh, J. A., Vida, M. D., and Rutherford, M. D. (2014). Strategies for perceiving facial expressions in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 1018–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1953-1

Wehman, P., Schall, C., Carr, S., Targett, P., West, M., Cifu, G., et al. (2014). Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorder: what we know and what we need to know. J. Disability Policy Stud. 25, 30–40. doi: 10.1177/1044207313518071

Wood, J. M., Tataryn, D. J., and Gorsuch, R. L. (1996). Effects of under-and overextraction on principal axis factor analysis with varimax rotation. Psychol. Methods 1:354. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.4.354

Wood, R., and Happé, F. (2023). What are the views and experiences of autistic teachers? Findings from an online survey in the UK. Disability Soc. 38, 47–72. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2021.1916888

Zalewska, A., Migliore, A., and Butterworth, J. (2016). Self-determination, social skills, job search, and transportation: is there a relationship with employment of young adults with autism? J. Vocational Rehabil. 45, 225–239. doi: 10.3233/JVR-160825

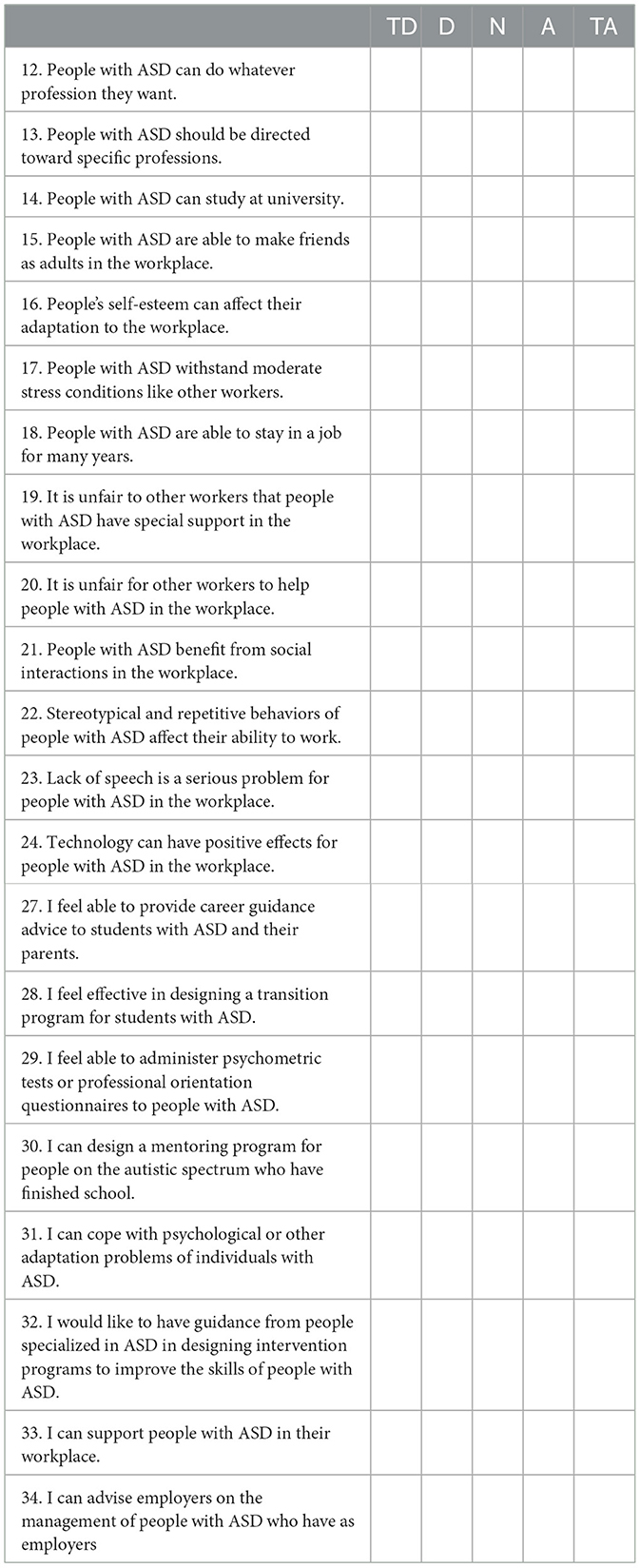

Appendix

Questionnaire

PART I

Gender: Male □ Female □

Age: 22-28 □ 29-34 □ 35-40 □ 41-46 □ 47 and above □

Marital status: Single □ Married □ Divorced □ Widowed □

Qualification [graduate]:..........................................................................

Bachelor's degree □ (please specify specialty) Diploma or Master's

degree in Career Counseling □ Ph.D □

Years of working as a Career Guidance Counselor: 1-5 □ 6-11 □

12-17 □ 18-23

Have you been trained or retrained in autism□

Yes □ No □

How many students with autism have you offered SEP services to□

1-5 □ 6-10 □ 11-15 □ More than 15□

PART B

Read the following sentences and answer according to your perceptions. The proposals refer to people with high-functioning autism. The options are: DK: Totally Disagree, D: I disagree, N: I'm Neutral, A: Agree, TA: Totally Agree

25. Do you think there are professions more suitable for people with ASD□

YES □ NO □

If yes, please specify (at least 3):..............................................................

26. Do you believe that there are professions that are inappropriate/prohibitive for people with ASD□ YES □ NO □

If yes, please specify (at least 3):..............................................................

PART C

The items refer to people with high-functioning ASD. The options are: TD: Totally Disagree, D: I disagree, N: I'm Neutral, A: Agree, TA: Totally Agree

Keywords: career counselors, autism and employment, career counselors' attitudes, autistic individuals, employment skills and autism

Citation: Stampoltzis A, Peristeri E and Kalouri R (2025) Career counselors' attitudes about employment-related skills of individuals with autism spectrum disorders in Greece. Front. Educ. 10:1662929. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1662929

Received: 09 July 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 18 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jaeyoung Kim, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kyriaki Sarri, University of Macedonia, GreeceEsra Orum Çattik, Eskisehir Osmangazi Universitesi, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Stampoltzis, Peristeri and Kalouri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aglaia Stampoltzis, bHN0YW1wQGh1YS5ncg==

Aglaia Stampoltzis

Aglaia Stampoltzis Eleni Peristeri

Eleni Peristeri Rany Kalouri3

Rany Kalouri3