- 1Faculty of Education, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kajang, Malaysia

- 2Faculty of Health Science, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kajang, Malaysia

Introduction: Effective teaching plays an important role in improving students’ learning outcomes. Unfortunately, research on factors influencing special education teachers’ effective teaching remains lacking. This study aimed to examine the extent to which perceived personal and school-related contextual factors influence effective teaching practices.

Methods: The study utilized data from a survey involving 311 special education teachers in Malaysian secondary schools to construct structural equation models of the interplay between the teachers’ personal factors, contextual factors, and teaching effectiveness. Data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). This study also validated the mediation testing by utilizing a resampling procedure known as a bootstrapping method.

Results: The findings indicated that contextual factors significantly influence the teachers’ beliefs, knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitudes. Specifically, beliefs and knowledge were also found to significantly and directly influence effective teaching practices, as well as serve as full mediators between contextual factors and effective teaching practices.

Discussion: Hence, this study highlights the need for professional development programs emphasizing teachers’ beliefs and knowledge, particularly to improve effective teaching practices among special education teachers.

1 Introduction

Teachers play a crucial role in achieving the teaching goals for students with Special Educational Needs (SEN) to support Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4. The achievement of such goals depends on their competence and training in implementing appropriate strategies. While considering the implications of students’ disabilities, teachers must understand the needs and potential of SEN, which may be influenced by environmental factors resulting from family, community, and school (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020). Therefore, effective teaching should begin from the basic level of students’ skills or knowledge (Alesech and Nayar, 2021; Klang et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2020). Effective teaching practices of special education teachers involve setting clear objectives, delivering lessons explicitly, providing scaffolded guided practice, and adjusting the teaching pace according to students’ abilities. Teachers also need to create opportunities for interaction, monitor understanding with immediate feedback, and flexibly adapt strategies. This approach supports effective learning based on the principles of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al., 1956) and explicit instruction (Johnson et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, prior studies revealed that many special education teachers lack confidence or are unaware of suitable strategies that meet the needs of SEN (Abramczyk and Jurkowski, 2020; Cornelius et al., 2020). Additionally, they face a higher risk of stress and burnout compared to mainstream teachers (Park and Shin, 2020). Consequently, the critical shortage of special education teachers has been a persistent issue since the 1980s (Boe and Cook, 2006; Kvande et al., 2019), including in developed countries. This issue has also been highlighted in the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013–2025 and in the study conducted by Alshoura (2021). According to Mason-Williams et al. (2020), efforts to address shortages of special education teachers by recruiting candidates without a teaching background may result in negative economic impacts due to unproductive training and education costs.

Previous studies identified various factors leading to the shortage of quality special education teachers, including contextual factors, knowledge, efficacy, and beliefs. Barriers such as insufficient support from the school (Park and Shin, 2020; Rizvi Jafree et al., 2023), inadequate infrastructure (Mason-Williams et al., 2020; Mihat, 2019; Starks and Reich, 2023), and the neglect of special education policies (Finlay et al., 2022) negatively affect teachers’ well-being and teaching quality and hinders the achievement of SDG4. Additionally, teaching strategies, beliefs (Maag, 2020; Taresh et al., 2020), and teachers’ self-efficacy (Mastrothanasis et al., 2021) are impacted by limited special education pedagogical knowledge and workload burdens. Nevertheless, no existing comprehensive studies examined the integrated effects of knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy on effective teaching in Malaysia. To address this gap, the present study investigates direct and indirect influence of contextual and personal factors on teachers’ teaching practices. The present study’s purpose is to fill the highlighted gap by providing an understanding of the direct and indirect links between the variables mentioned and identifying the most influential personal factors as mediators. The quality of special education teachers’ teaching practices is expected to improve with the help of the study’s findings.

2 Literature review

2.1 The impact of contextual factors on the personal factors of special education teachers

Past and present environmental cues, which individuals perceive consciously or unconsciously, are contextual factors (Cook et al., 2023). Based on Kozma’s Model (2003), contextual factors in this study comprise three levels, namely micro (classroom infrastructure), meso (organizational support), and macro (professional teaching training experience). On the other hand, intrinsic individual traits, particularly pedagogical knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy, reflect personal factors (Grotkamp et al., 2012). Analyzing past research revealed that most studies about how contextual factors affect those four personal factors have been mostly undertaken with teachers in inclusive programs. For instance, Aas (2022) and Dignath et al. (2022) explored how contextual factors shape teachers’ beliefs and teaching programs. Other researchers, such as Perrin et al. (2021), Saloviita (2020), Braksiek (2022), and Moberg et al. (2020), studied how contextual factors affect teachers’ attitudes. Some recent studies (Park and Shin, 2020; Antoniou et al., 2023; Benigno et al., 2024) have connected contextual factors, teachers’ self-efficacy, and burnout, specifically among special education teachers. Furthermore factors such as poor communication can hinder access to contextual resources and negatively impact teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, making effective teaching support more difficult (Alexander and Byrd, 2020). Teaching support, administrative support, recognition, and professional development opportunities are recognized as critical resources influencing the development of teachers’ personal factors. Nevertheless, previous research is limited as the exploration of the relationship between contextual factors and special education teachers’ four personal factors (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and efficacy) remains limited. Accordingly, the present study involved three levels of contextual factors (micro, meso, and macro) and four personal factors to offer an understanding of and assist in decision-making in special education programs.

2.2 The impact of personal factors on the teaching practices of special education teachers

While contextual factors provide an external environment for teachers, personal factors are equally important in shaping teaching practices. This study investigated how the four personal factors, namely knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy, directly influence special education teachers’ teaching practices. Personal factors can sometimes pose difficulty in achieving teaching success (Basckin et al., 2021). Additionally, teachers’ knowledge can be a strong foundation for active learning (Billingsley et al., 2020; Alsolami, 2022). However, teachers may focus on school directives rather than effective teaching strategies. This approach can limit how teachers apply their pedagogical knowledge (Basckin et al., 2021). Thus, clearly understanding the relationship between teachers’ knowledge, beliefs, and their actual teaching practices is crucial, as it underscores the importance of the present study. Prior studies have not paid enough attention to how attitudes and self-efficacy affect teaching practices (Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020). The studies focused on related areas such as teaching intentions (Börnert-Ringleb et al., 2021; Mathews and Myers, 2022), teacher preparation (Binammar et al., 2023), and teacher stress (Park and Shin, 2020). Unfortunately, none directly address teaching practices. Contrarily, most studies concentrated on teachers in inclusive classrooms (Heyder et al., 2020; Moberg et al., 2020; Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020; Saloviita, 2020; Braksiek, 2022).

In light of these limitations, existing research has yet to specifically explore how these four personal factors (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and efficacy) influence effective teaching practices among special education teachers. Therefore, this gap makes a significant contribution to the present study by investigating the relationship between personal factors and teaching practices among special education teachers, thereby strengthening the underlying theoretical framework.

2.3 Personal factors as mediators in the relationship between contextual factors and teaching practices of special education teachers

Beyond their direct impact on teaching practices, personal factors may also play a mediating role in the relationship between contextual factors and teachers’ effectiveness. Personal factors in this study are based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory. The theory identifies personal determinants as indexed by self-belief (beliefs and efficacy), analytical thinking quality (knowledge), and affective traits (attitudes) (Bandura, 1999). Recent studies also associate personal factors with professional identity, comprising knowledge, beliefs, values, and ethics (Fitzgerald, 2020; Lan, 2024). The emphasis of the theory on the individual as both a product and a producer of their environment highlights the interrelation between contextual factors, personal factors, and behavior.

For example, the influence of the support from school leadership on effective teaching is mediated by teachers’ personal traits such as efficacy and motivation. Without these personal factors, strong contextual support cannot translate into better teaching effectiveness. Nonetheless, analyzing prior research revealed a gap in the literature in relation to the four personal factors as mediators between contextual factors and special education teachers’ effective teaching practices.

The gap identified in this study is addressed by examining the complex internal structure in the relationship that exists between school environments and teacher characteristics, which has been highlighted by Toropova et al. (2021). The effort seeks to identify special education teachers’ quality and retention. Specifically, this study investigated whether the four personal factors (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy) mediate the relationship between contextual factors and special education teachers’ effective teaching practices. While previous studies (Werner et al., 2021; Cansoy et al., 2022; Lera et al., 2023) explored teacher self-efficacy as a mediator and attitudes as partial mediators (Corso-de-Zúñiga et al., 2020), none explored special education teachers (Hazan-Liran and Karni-Vizer, 2024).

Other studies investigating the role of personal factors as mediators involving special education teachers include those by Fu et al. (2021), Zhang et al. (2020), and Chen et al. (2020). Nevertheless, these studies did not include all four personal factor variables examined in this study. Therefore, the present study provides a comprehensive contribution by linking Bandura’s social cognitive theory to special education. This study’s findings are expected to strengthen the theoretical framework and contribute additional value to the existing body of knowledge regarding the role of personal factors among special education teachers.

2.4 Conceptual framework and research questions

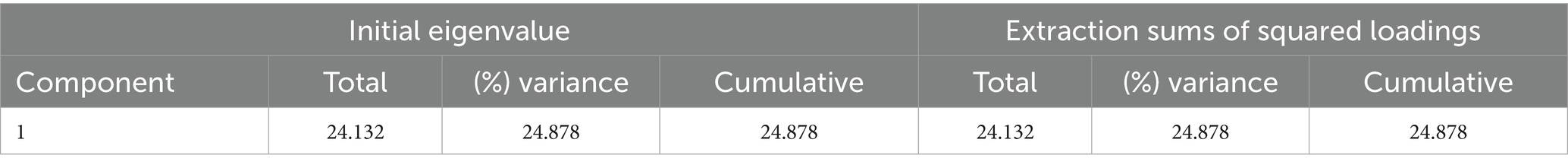

This study’s conceptual framework integrates Bandura’s social cognitive theory. The theory emphasizes the dynamic interaction between personal factors, behavior, and the environment. The study’s environmental context is based on Kozma’s (2003) conceptual model. This approach aims to understand how personal factors (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy) mediate the relationship between contextual factors and special education teachers’ effective teaching practices. Personal factors, as components of Bandura’s social cognitive theory, influence and are influenced by behavior and contextual factors. The contextual factors adapted from Kozma’s model are divided into three levels:

i. Micro: Teachers’ perceptions of classroom infrastructure.

ii. Meso: Teachers’ perceptions of organizational support within schools.

iii. Macro: Teachers’ perceptions of policies related to professional teacher training.

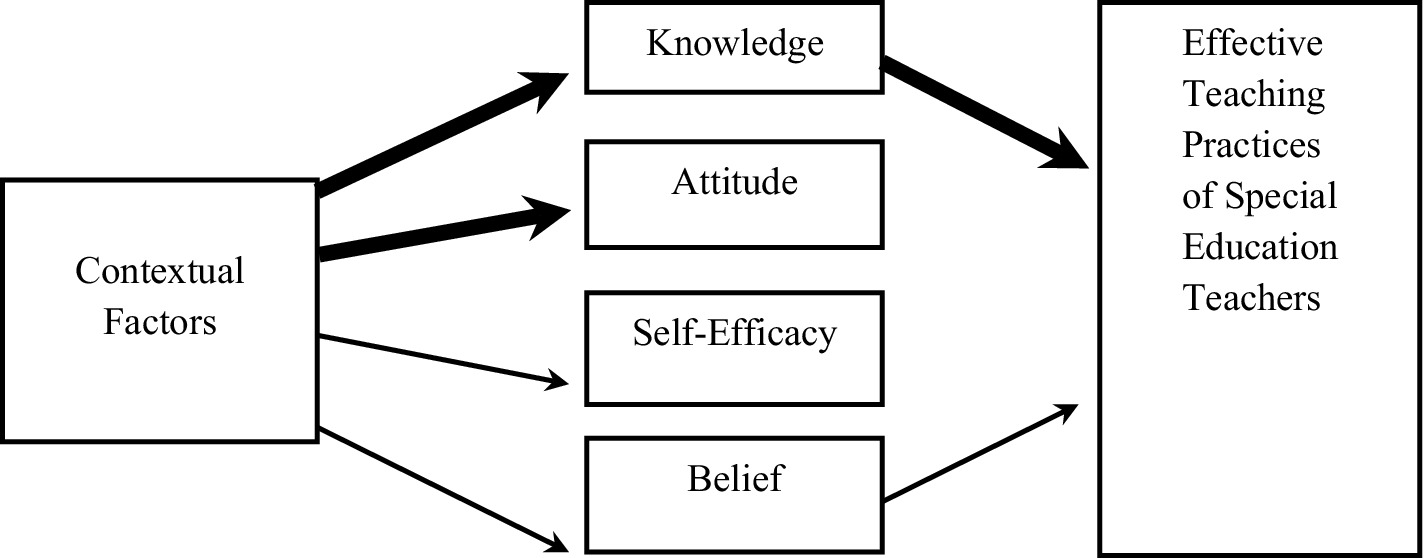

The conceptual framework proposes that contextual factors (Kozma, 2003) directly influence personal factors. In turn, personal factors act as mediators, translating the impact of contextual factors into effective teaching practices. This holistic framework identifies the mechanisms through which contextual factors affect behavior through personal factors. The framework is expected to provide guidance for future studies examining the systemic environmental impacts on special education. The direct and indirect influences of the variables are illustrated in Figure 1. The study is guided by the following three research questions:

1. How do contextual factors influence special education teachers’ personal factors?

2. How do special education teachers’ personal factors influence perceived effective teaching practices?

Figure 1. Conceptual framework model of the influence of contextual and personal factors on the effective teaching practices of special education teachers.

Do personal factors act as mediators between contextual factors and effective teaching practices of special education teachers?

3. Methods

3.1 Samplings

This study’s participants comprised secondary special education teachers, who were selected through Stratified Random Sampling from one state in each of Malaysia’s five zones. The selected state from each zone was determined based on the number of secondary integrated schools and secondary special education students in the particular zone (Bahagian Pendidikan Khas, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia, 2023). A total of 109 respondents participated in the pilot study phase, while another 202 respondents were involved in the main study. Each respondent completed the administered survey questionnaire anonymously, without indicating their names or schools. The information related to the districts they work was obtained from the Ministry of Education Malaysia. The information was used to determine the respondent ratio for each zone and state (Bahagian Pendidikan Khas, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia, 2023).

Information related to their work district was collected to determine the respondent ratio for each zone and state. Additionally, participants were requested to provide demographic details, including gender, age, academic qualifications, background in special education, and teaching experience in the field of special education.

3.2 Measurements

This study involved six variables with 171 initial items during face validity testing. After the elimination of irrelevant items through content validity analysis, the items were reduced to 117. Subsequently, the total number of items was further reduced to 103 following item removal based on the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) conducted during the pilot study. After item removal during the EFA, the reliability of the instrument was analyzed. The findings revealed high reliability for all constructs: contextual factors (α = 0.957), belief (α = 0.811), effective teaching practices (α = 0.935), knowledge level (α = 0.950), self-efficacy (α = 0.877), and attitude (α = 0.927). The instruments demonstrated strong consistency when tested multiple times.

3.3 Contextual factors questionnaire

Based on Kozma’s (2003) model in Fulmer et al. (2015), this study’s contextual factors involved a combination of three adapted instruments to assess three sub-constructs: teachers’ perceptions of classroom infrastructure, school support, and the implications of professional teacher training on their roles. As a strategy to measure contextual factors, this study employed the contextual scale developed by Abduh et al. (2025). The scale integrates three instruments to measure the subconstructs of infrastructure, organizational support, and teachers’ professional training. With a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.952, the scale demonstrated a very high level of reliability.

• In order to measure teachers’ perceptions of special education classroom infrastructure, items were adapted from Lera et al. (2023) and Corso-de-Zúñiga et al. (2020).

• The second instrument used to measure teachers’ perceptions of school support was adapted from the Perceived Organizational Support instrument by Hazan-Liran and Karni-Vizer (2024), which included ten high-factor-weighted items.

• The third instrument measured teachers’ perceptions of their professional training history using the Perception of Your Initial Teacher Training Survey developed by Fu et al. (2021), involving 30 items (reduced from the original 34).

Reported reliability values for the second and third instruments were 0.97 and 0.89, respectively. In contrast, no reliability values were available for the infrastructure perception instrument. A seven-pointLikert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was used, with higher scores indicating a better contextual environment.

3.4 Pedagogical knowledge questionnaire

Sonmark et al. (2017) Teacher Knowledge Survey on pedagogical knowledge was adapted before being utilized in this study. The original instrument’s reliability met the minimum requirement of 0.60 for pilot studies. The reliability was reported to be between 0.40 and 0.70 (Straub et al., 2004). By using a Likert scale (Taherdoost, 2016; Whitley et al., 2013), the reliability was reassessed and improved. A seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), which shows the respondents’ agreement with items to measure pedagogical knowledge, replaced the original binary scale.

3.5 Belief questionnaire

With the help of an adapted version of Glenn (2018) Beliefs about Learning and Teaching Questionnaire, teachers’ beliefs on special education teaching were also measured. The original instrument assessed teachers’ beliefs about special education students and their teaching practices. The instrument had four sub-constructs and 20 items. The adapted items showed a reliability of 0.81. A seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was utilized instead of the original six-point scale. With the seven-point scale, the respondents highlighted their beliefs on the roles of special education teachers and their students.

3.6 Effective teaching practices questionnaire

The current study applied the Recognizing Effective Special Education Teachers (RESET) instrument by Johnson and Semmelroth (2012) in determining how special education teachers effectively taught at the secondary level. The instrument was employed to assess effective teaching practices in special education. It identifies student needs and the employment of evidence-based teaching methods, showing student progress. This instrument has proved to have strong internal consistency with a reliability of 0.74. Some of the items included in the RESET instrument were adapted with permission from the original authors. The modification followed the indications given by Stewart et al. (2012) by using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Several methods were used to ensure the questionnaires’ validity on contextual factors, pedagogical knowledge, beliefs, and effective teaching practices, such as Lawshe (1975) method, back-translation techniques, expert reviews, and pretesting (Brislin, 1970). These items were further refined based on the experts’ feedback. According to Awang et al. (2018), pilot testing was an evaluative measure for the factor weights, item components, and internal consistency. Pilot data were run for EFA to establish the underlying structure of the variables. Details about validity, reliability, and EFA can be provided upon request via email.

3.7 Special education teachers’ attitude questionnaire

Subsequently, to examine special education teachers’ attitudes toward their profession, Küçüközyiğit et al. (2017) Attitude Scale towards Special Education as a Teaching Profession was used. This scale was chosen due to its focus on the examined area. The pilot study demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

3.8 Self-efficacy questionnaire

As the next step to measure special education teachers’ self-efficacy, the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) was used. This scale was chosen for its relevance. The TSES includes three sub-scales: Instruction, Management, and Engagement. Each sub-construct demonstrated high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.91, 0.90, and 0.87, respectively. For attitude and self-efficacy questionnaires, instruments previously adapted by Lim (2021) in a study with special education preschool teachers in Malaysia were utilized. While the original scales used five-point and nine-point response options based on expert recommendations, the researchers adjusted them to a seven-point scale.

3.9 Study procedure

The researchers obtained permission from the Ministry of Education and the respective State Education Departments to conduct this study. Data was collected through an online survey distributed via Google Forms. Department heads in each state shared the survey link with all special education teachers in their respective states. Additionally, to ensure a representative sample, states from each of the five zones (North, East, Central, South, and Borneo) were selected based on the number of students with special needs (MBPK) and schools in each state. This selection was justified by the distribution of national education budget allocations, which is largely based on the number of schools in each state (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2013).

3.10 Data analysis

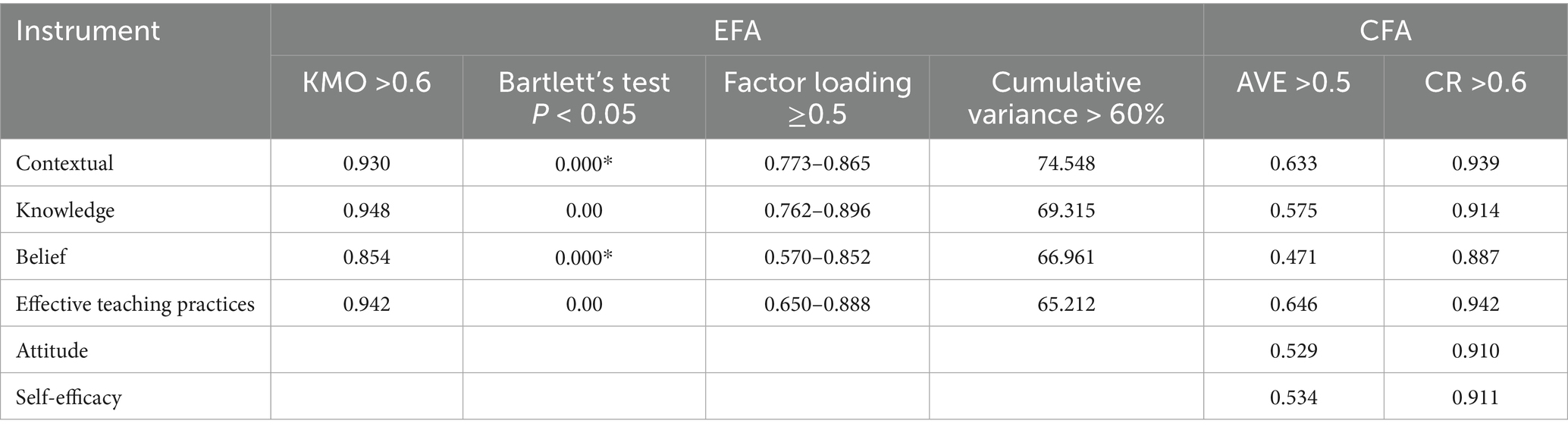

A pilot study was also carried out to confirm the questionnaire’s effectiveness and its suitability for the study. EFA was used to determine groups of items that are related to one another (Watkins, 2021). EFA was also conducted to determine the adequacy of the sample size based on the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value and Bartlett’s Test. When KMO > 0.5 and Bartlett’s Test is significant [p < 0.05), the sample size is considered adequate (Field, 2017)]. In the pilot study involving 109 respondents, the KMO value was 0.913 and Bartlett’s Test was significant at 0.00 (p < 0.05), indicating that a sample size of 200 or more would be appropriate for the main study. The factor loading values for the contextual, knowledge, belief, attitude, and self-efficacy constructs ranged from 0.570 to 0.896, indicating that all the variables tested contributed from moderate to strong levels to their respective factors. Meanwhile, the cumulative variance percentage of the four constructs ranged from 65 to 74%, suggesting that the extracted factors successfully explained most of the total data variability (Table 1). Literature sources support that a factor loading of ≥ 0.5 is considered significant and valid, while a cumulative variance value of > 60% is regarded as the effective threshold for explaining data in factor analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019).

Thereafter, structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to examine associations between contextual factors, personal factors, and teaching approaches, with possible mediation of personal factors (Moshagen and Bader, 2024). These integrated analytical methods provided a foundation for the proposed model. In this model, there is an integrated understanding of how context and personal factors may influence effective teaching practices. By using AMOS software, the measurement model was evaluated through CFA within the SEM framework. Validity checks were conducted multiple times. Convergent Validity was established by examining the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct, with all AVE values exceeding the required threshold of 0.45. Additionally, Composite Reliability (CR) values for all constructs were above the minimum standard of 0.60 (Table 1). These findings suggest that both convergent validity and composite reliability are acceptable for all constructs (Awang et al., 2023).

Normality testing showed skewness values ranging from 0.145 to −0.807, which falls within the acceptable limits of −1.5 to 1.5, as suggested by Awang et al. (2023). A pooled CFA was then conducted to address any potential multicollinearity issues during the structural modeling phase (Awang et al., 2018). The analysis of the structural model included direct effects, which were evaluated through regression coefficients, and indirect effects, which were explored through multiple mediation analyses. Bootstrapping techniques, utilizing the estimand function in AMOS software, were employed during the multiple mediation analysis (Collier, 2020).

4 Result

4.1 Measurement model

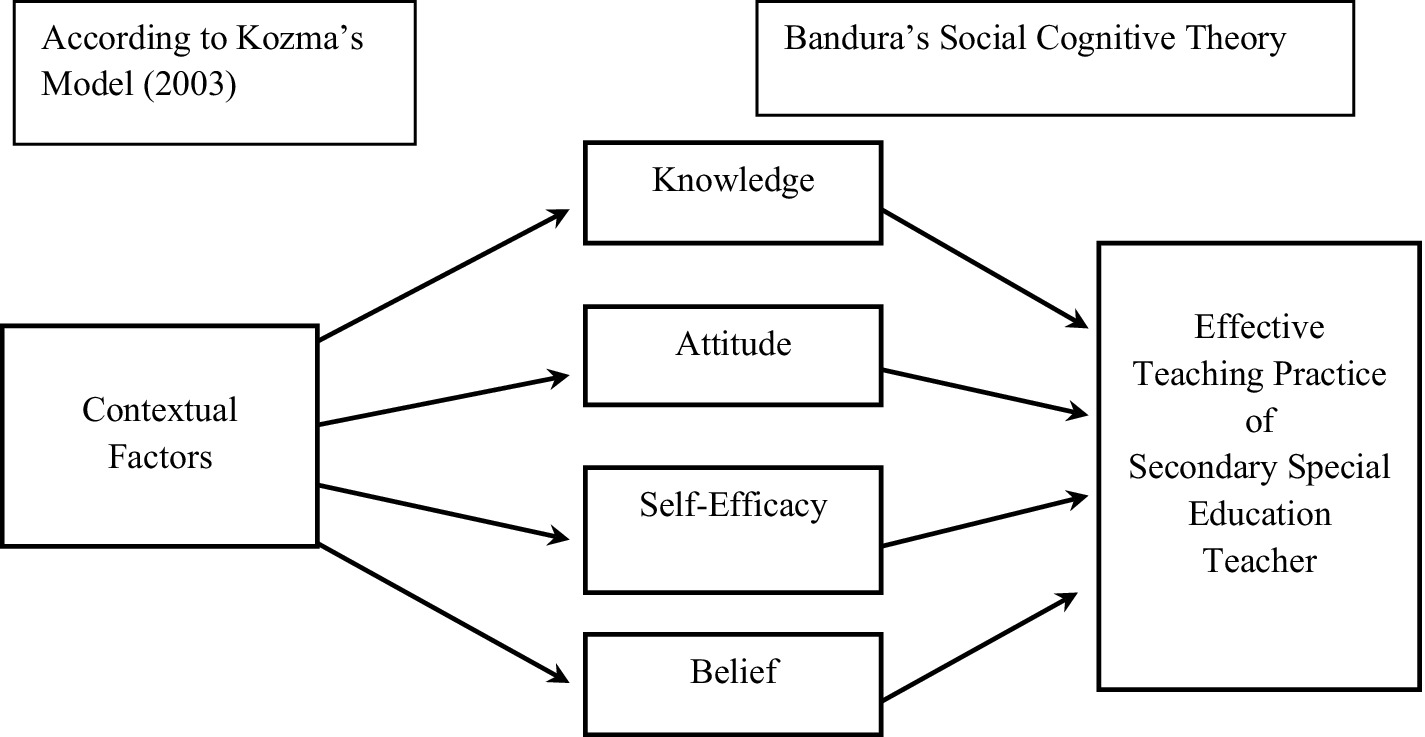

This study involved a complex measurement model featuring six constructs. Two constructs, namely contextual factors and beliefs, were second-order constructs. A parceling procedure was implemented to minimize the impact of disturbance factors when modeling the influence of latent variables (Little et al., 2002), simplify the model with a smaller covariance matrix of indicators, and improve model fit (Williams and O’Boyle, 2008).

For the second-order constructs, all items for each sub-construct were bundled together. The average value for each sub-construct was calculated to form the first-order construct model. Subsequently, each construct of self-efficacy, knowledge, attitudes, and effective teaching practices has more than ten items. Thus, item parceling was conducted using the second method, the factorial algorithm, as suggested by Williams and O’Boyle (2008). Figure 2 illustrates the measurement model of this study after the item parceling process was applied.

Figure 2. Combined measurement model (pooled CFA) of contextual factors, knowledge, belief, attitudes, self-efficacy, and effective teaching practices of secondary special education teachers after parceling.

Based on Figure 2, model fit was achieved with an RMSEA value of 0.053, which is below the recommended threshold of 0.08 suggested by Awang et al. (2023). The CFI value of 0.965 and TLI value of 0.957 also meet the ideal threshold, exceeding 0.90 (Awang et al., 2023). The values also surpassed 0.95 for a sample size of fewer than 250 respondents, as recommended by Hair et al. (2010). The Chi sq./df ratio of 1.561 meets the ideal criterion of being less than 3.0, as proposed by Awang et al. (2023). Figure 2 also demonstrates that all correlation coefficients between constructs are below 0.85, indicating the absence of multicollinearity among the study’s constructs.

Common method variance (CMV) analysis was conducted using Harman’s One-Factor Solution with SPSS version 25 to identify systematic error variance commonly found in behavioral studies (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Table 1 presents the result of the CMV analysis.

Table 2 shows that the total variance for the first component was 24.878%, which is less than the 50% threshold. Therefore, CMV is not present in the structural model, as per Awang et al. (2023). Thus, the researchers proceeded with structural model analysis.

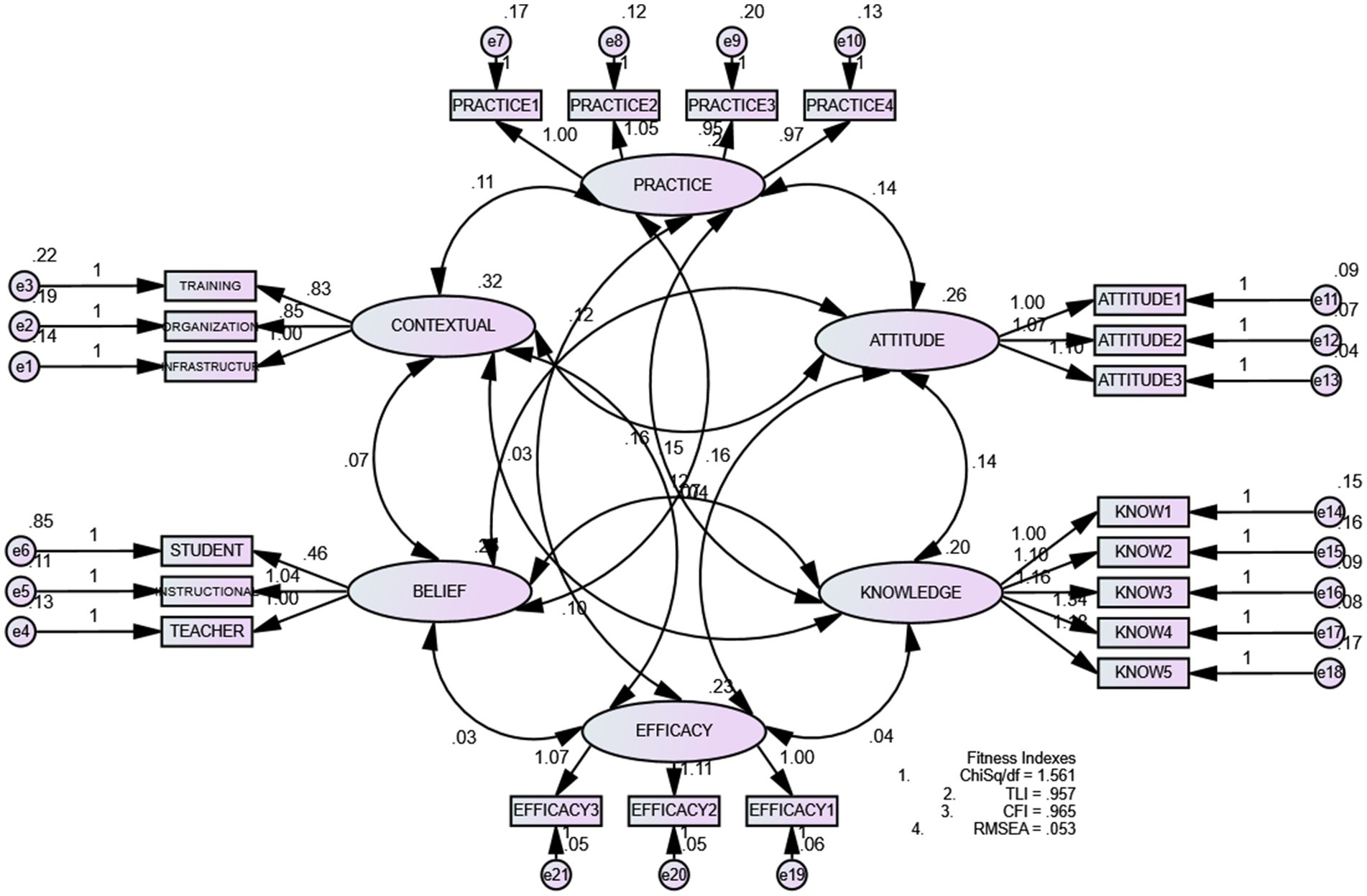

4.2 Structural model (direct influence)

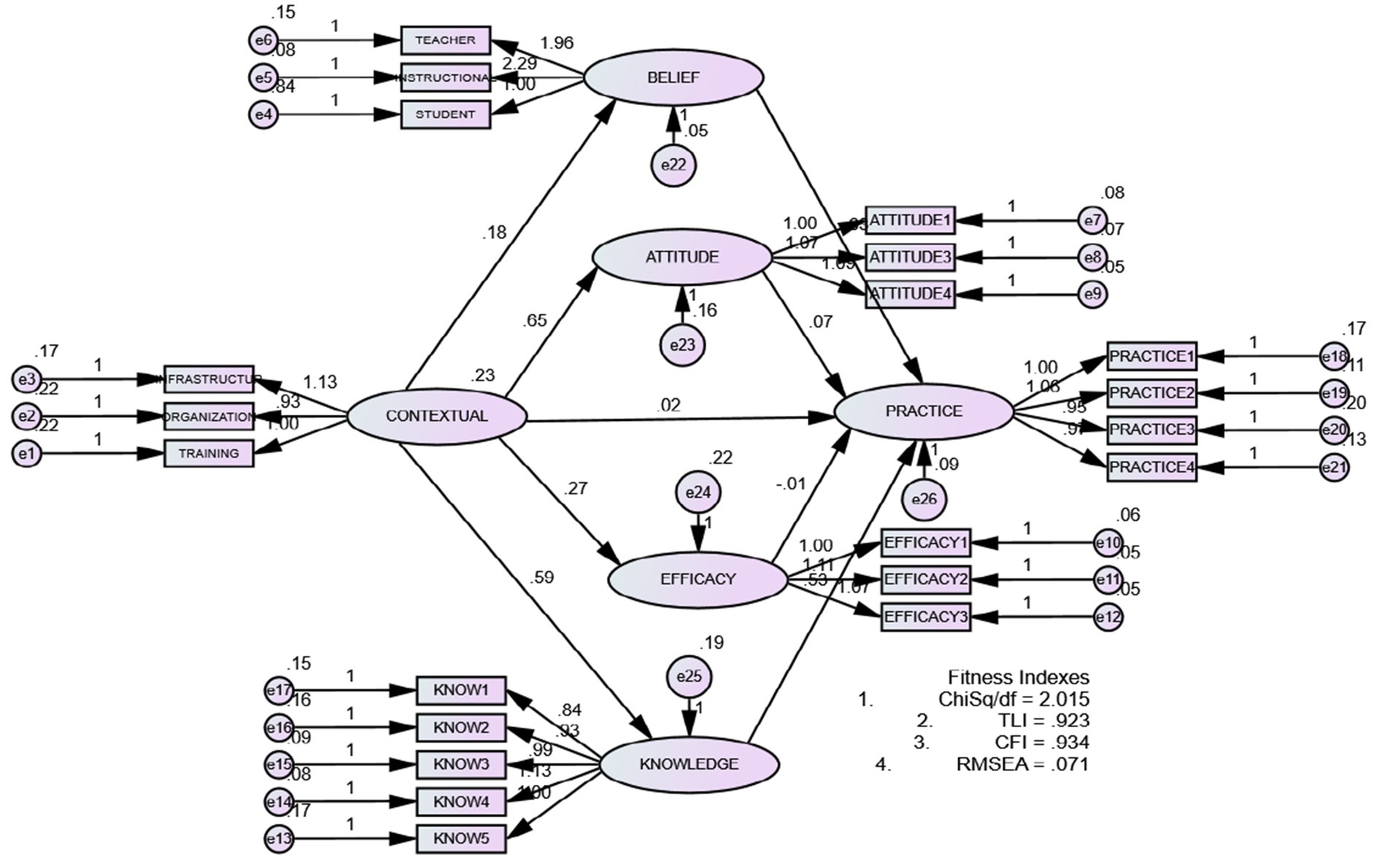

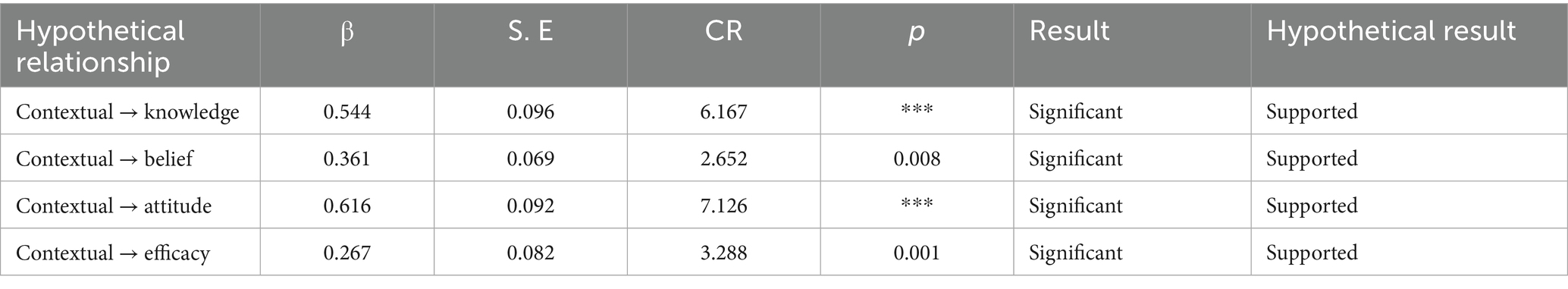

Figure 3 illustrates the structural model. The four hypotheses represent direct influences to be tested using regression coefficients (beta values) to determine the impact of contextual factors on personal factors (belief, attitudes, self-efficacy, and knowledge). Additionally, Figure 3 also depicts four other hypotheses involving the direct influence of the four personal factors on effective teaching practices, which were also tested.

Figure 3. Regression coefficients and hypotheses for the direct influence of contextual factors on personal factors and direct influence of personal factors on effective teaching practices.

Tables 3, 4 present the regression coefficients and their significance values based on p < 0.05. The results of the hypotheses testing in relation to the direct influence of contextual factors, personal factors, and effective teaching practices of special education teachers are also presented in both tables.

Table 3. Regression coefficients and significance values for hypotheses on the influence of contextual factors on personal factors.

Table 4. Regression coefficients and significance values for hypotheses on the influence of personal factors on effective teaching practices of special education teachers.

The result in Table 3 shows that contextual factors impact knowledge (β = 0.544, CR = 6.167, p = 0.001), belief (β = 0.361, CR = 2.652, p = 0.008), attitudes (β = 0.616, CR = 7.126, p = 0.001), and secondary special education teachers’ self-efficacy (β = 0.267, CR = 3.288, p = 0.001). These findings indicate that changes in contextual factors positively influence personal factors (knowledge, belief, attitudes, and self-efficacy). The greatest influence was observed on attitudes compared to the other personal factors.

The results in Table 4 reveal that attitudes (β = 0.075, CR = 0.934, p = 0.350) and secondary special education teachers’ self-efficacy (β = −0.005, CR = −0.090, p = 0.928) do not influence their effective teaching practices. These findings indicate that changes in personal factors (attitudes and self-efficacy) do not affect secondary special education teachers’ teaching practices.

Conversely, secondary special education teachers’ knowledge (β = 0.591, CR = 6.674, p = 0.001) and belief (β = 0.330, CR = 2.790, p = 0.005) significantly influence their effective teaching practices. The positive regression weights indicate that effective teaching practices are positively influenced by knowledge and belief. As shown in the table, knowledge has a stronger influence (0.591) on effective teaching practices compared to belief (0.330). Structural Model (Indirect Influence).

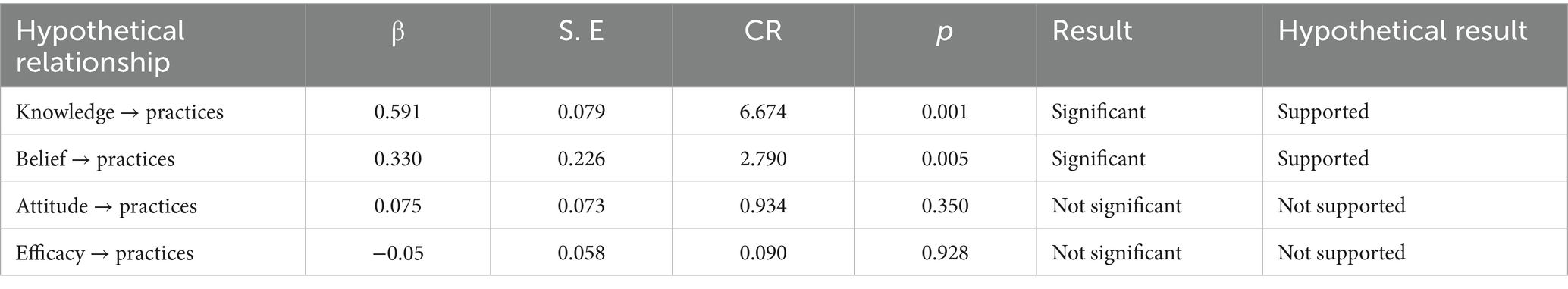

Table 5 presents the findings of the bootstrap analysis undertaken to validate the role of four mediators that may influence the relationship between contextual factors and special education teachers’ effective teaching practices.

Table 5. Structural path analysis of contextual factors and effective teaching practices through four personal factors.

Based on Table 5, testing knowledge and belief as mediators reveals that the indirect effect is significant, while the direct path is not significant. The regression coefficient for the indirect effect is higher than the regression coefficient for the direct effect. The results indicate that belief and knowledge fully mediate the influence of contextual factors on the special education teachers’ effective teaching practices, as the direct effect of contextual factors on teaching practices was not statistically significant (Awang et al., 2023). According to the criteria set by Collier (2020), the bootstrapping test indicated that belief and knowledge serve as mediators for the direct effect of contextual factors. However, bootstrapping tests could not be conducted for attitudes and self-efficacy as mediators. Only one indirect path showed statistical significance. As a result, the mediation testing criteria established by Collier (2020) were not satisfied. The results suggest that the indirect impact of contextual factors on the effective teaching practices of special education teachers is not entirely accounted for by attitudes and self-efficacy.

5 Discussion

5.1 Influence of contextual factors on n personal factors

The study’s findings indicate that contextual factors positively impact the personal factors of special education teachers. Enhancements in classroom infrastructure, organizational support, school leadership, and the quality of special education programs can lead to advancements in teachers’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and self-efficacy, which are elements of personal factors. This finding extends previous studies, particularly those reported in Smale-Jacobse et al. (2023) study. The study examined contextual factors but did not address beliefs and self-efficacy. In line with the findings of Parey (2019) and Breyer and Gasteiger-Klicpera (2024), this study found the significant effect of contextual factors on teachers’ attitudes. This result is particularly important in view of the strong relationship between teachers’ attitudes, pre-service training (Breyer and Gasteiger-Klicpera, 2024), their interactions with students (Kunz et al., 2021), and the quality of school leadership (Pardosi and Utari, 2022).

The in-depth analysis suggests that the influence on self-efficacy remains weak while contextual improvements enhance pedagogical knowledge and positive attitudes. This finding could be attributed to the high workload and limited resources that often characterize special education settings. Hence, the weak self-efficacy may offset the benefits of supportive environments. For instance, although teachers may gain knowledge through professional training, the absence of an adequate human workforce or excessive administrative demands can undermine their confidence in applying such knowledge effectively. This finding aligns with those of Granger et al. (2024). The authors demonstrated that self-efficacy, although developed through experience, can be diminished by environmental pressures. In the Malaysian context, where special education classes often have a larger student-teacher ratio than recommended, the gap between contextual support and practical classroom realities may help explain this weaker relationship.

Nevertheless, the findings reinforce the theoretical perspective of Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which emphasizes the role of environmental factors in shaping beliefs and knowledge. Nonetheless, this study suggests that environmental demands may act as both enablers and inhibitors simultaneously, a nuance not typically highlighted in past literature. This dual effect warrants further theoretical consideration, particularly in explaining the reason contextual factors may strengthen knowledge and attitudes but fail to enhance self-efficacy consistently.

Acknowledging potential biases in this study is also important. First, most participating teachers were from urban schools where infrastructure and leadership support may be relatively stronger than in rural areas. Thus, the positive association between contextual factors and personal factors could be potentially inflated. Second, self-reported measures of attitudes and beliefs may have been influenced by social desirability bias, leading teachers to present themselves more positively. Third, the weak effects observed could be partially explained by the use of general instruments, which may not have captured the unique aspects of self-efficacy in special education.

Practical implications include the need for systemic improvements in school infrastructure and leadership training, as well as stronger organizational support structures such as mentoring and counseling services. Nevertheless, the findings also carry theoretical implications beyond practical steps. The findings suggest that models linking contextual factors to teachers’ development should account for the possibility of uneven effects across personal factors, particularly when self-efficacy is involved. Therefore, future research should explore moderating variables, such as workload, class size, and administrative policies, which may explain the conditions for contextual factors to translate into stronger or weaker self-efficacy outcomes.

5.2 Influence of personal factors on the effective teaching practices of special education teachers

The study found that personal factors, particularly beliefs and pedagogical knowledge, strongly influence the effective teaching practices implemented by special education teachers. In contrast, attitudes and self-efficacy did not have a significant effect. These findings support social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and Sabarwal et al.’s (2022) view that teachers’ beliefs are central to improving educational quality. The findings also add value to prior inconsistent findings regarding the role of belief, as discussed by Billingsley et al. (2020) and Basckin et al. (2021).

A deeper reflection indicates that while beliefs and knowledge consistently translate into effective practices, attitudes and self-efficacy may be weaker predictors. One plausible explanation is that teachers’ daily practices are more strongly driven by pedagogical reasoning and expectations of student outcomes than by their general attitudes. As Eiser (1986) and Trafimow et al. (2004) argued, attitudes are inconsistent behavioral predictors. Similarly, the insignificant role of self-efficacy could be linked to contextual realities, as teachers may feel confident in principle yet remain constrained by systemic challenges such as large class sizes, limited support, and rigid curricula. This observation is consistent with Granger et al. (2024) and Lazarides and Warner (2020), who found weak links between self-efficacy and teaching practices, particularly when contextual barriers remain unresolved.

From a theoretical standpoint, these findings suggest a need to refine models related to teacher effectiveness by emphasizing belief and knowledge as stronger predictors of practice. Bandura’s social cognitive theory explains the mediating role of cognition and belief in shaping behavior. Nevertheless, the present study highlights that self-efficacy does not necessarily translate directly into practice. Instead, its influence may be contingent on structural support, indicating a more complex interplay between personal and contextual elements.

Potential biases must also be acknowledged. Self-reported data may reduce teachers’ perceived knowledge and belief levels. In addition, the lack of longitudinal measurement limits understanding of how these personal factors evolve over time. Additionally, cultural norms in Malaysia, which expect teachers to present themselves as competent, may amplify the reported role of belief while underreporting doubts or negative attitudes.

The practical implications are twofold. First, teacher education programs should prioritize developing strong pedagogical knowledge and reinforcing positive beliefs about students’ learning potential through experiential learning, simulation, and reflective practice. Second, by addressing contextual barriers, professional development should be designed to bridge the gap between confidence and actual classroom application. Beyond practice, the study also contributes theoretically by clarifying the differential impact of personal factors, showing that beliefs and knowledge appear to be core drivers. In contrast, attitudes and self-efficacy may play more indirect roles. This finding invites future research into possible moderators, such as organizational culture, workload, and policy pressures, which determine when attitudes and self-efficacy influence practice meaningfully.

5.3 Personal factors as mediators in the relationship between contextual factors and effective teaching practices of special education teachers

The analysis showed that contextual factors such as infrastructure, organizational support, and professional training did not impact effective teaching practices directly but influenced them through personal factors indirectly, specifically beliefs and knowledge. Knowledge emerged as a stronger mediating factor, consistent with the Malaysian Teacher Standards (SGM) and the Job Description of Education Service Officers (DTPPP), which stress the role of professional training and knowledge in teacher competency.

The mediating role of beliefs supports the findings of Pajares (1992), who emphasized that beliefs are shaped by evaluation and experience. The findings also corroborate Bandura (1977) assertion that beliefs guide behavior. This study adds nuance by demonstrating how beliefs are molded by contextual support such as leadership and professional training. However, unlike knowledge and beliefs, attitudes and self-efficacy did not significantly mediate the relationship. This finding may be due to unstable attitudes and self-efficacy, potentially requiring sustained mastery experiences to manifest in observable practice. Nonetheless, prior studies (Chen et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2021; Fu et al., 2021; Massé et al., 2022) suggest that both factors influence belief formation indirectly, which may, in turn, shape teaching practices.

Critically, the results suggest that theoretical models of teacher development should be adjusted to reflect the differential mediating strength of personal factors. While most literature assumes self-efficacy is a key mediator, this study indicates that knowledge and beliefs may serve as more immediate conduits between contextual support and practice in special education. This finding highlights the importance of distinguishing between potential mediators (self-efficacy, attitude) and effective mediators (knowledge, beliefs).

Possible biases must also be considered. The use of a cross-sectional design prevented the study from fully capturing the temporal sequence of how contextual factors shape personal factors and subsequently influence teaching practices. Self-reporting may also have limited the strength of knowledge as a mediator since teachers tend to equate attendance to training with actual competency. Additionally, as most participants were trained under the same teacher education system, the homogeneity of professional standards could have limited variability in responses, making knowledge appear more influential.

The implications are significant for both policy development and theoretical application. Practically, training should emphasize not only technical knowledge but also reflective practices, case studies, and mentorship to reinforce beliefs that support effective teaching. By providing mastery experiences and vicarious modeling, organizational support systems such as Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) and mentoring can strengthen these mediating pathways. Theoretically, the findings suggest refining social cognitive theory applications in education by recognizing the uneven mediating role of different personal factors. Future studies should use longitudinal or mixed method designs to explore how these mediators evolve and whether interventions can strengthen weaker pathways, such as self-efficacy, to complement knowledge and belief in shaping practice.

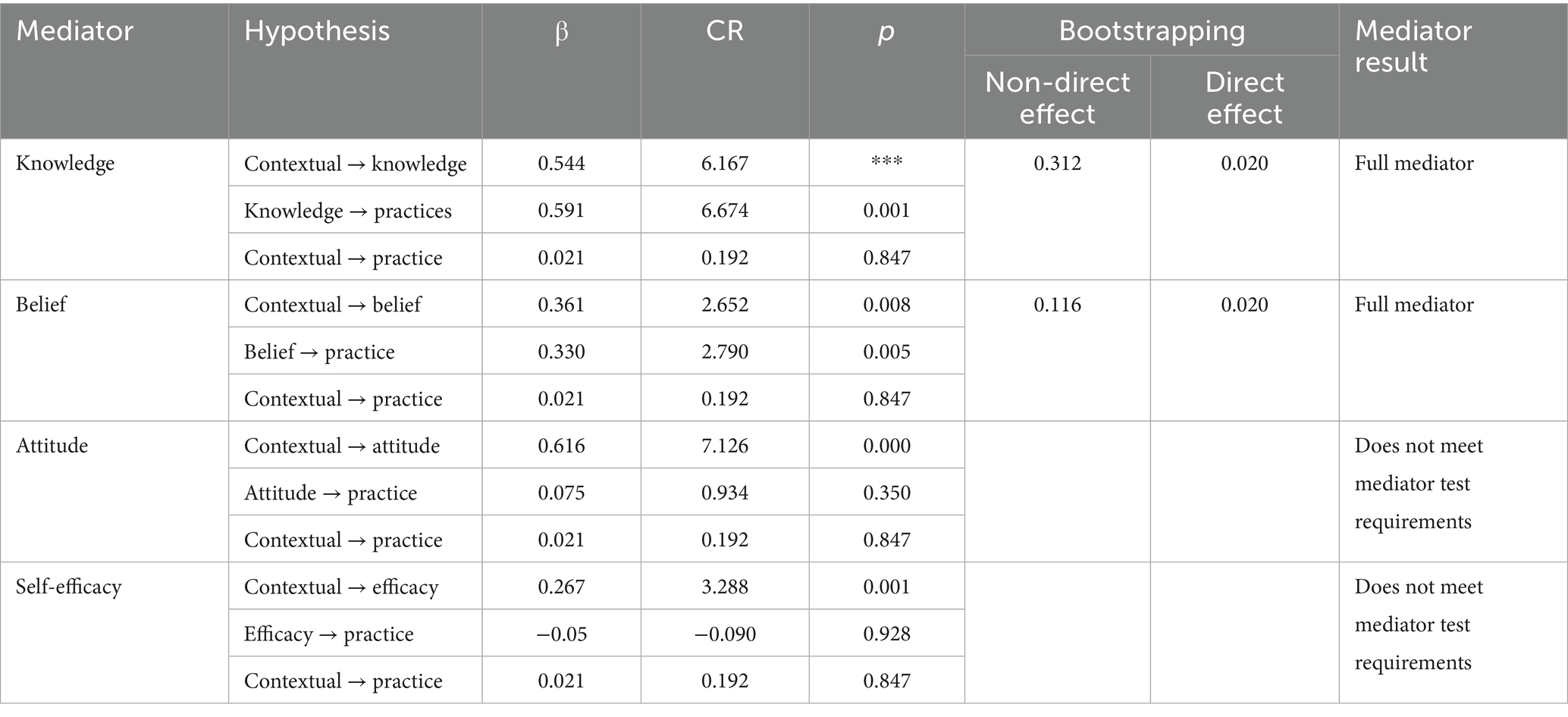

5.4 Implications for theory

Theoretical implications involve developing existing theories by considering personal factors as mediators in the indirect influence of contextual factors on effective teaching practices. This study presents a different perspective from previous studies. Prior studies often focused on the direct relationships between one or two factors. These studies also failed to address the question of the effectiveness of variations in special education teachers’ teaching practices. In this regard, the current study’s findings on the role of beliefs and pedagogical knowledge as mediators strengthen Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which conceptually states that humans are not passive objects shaped by their environment. The effective teaching model for special education teachers, as illustrated in Figure 4, exhibits both direct and indirect influences for each variable involved. This model highlights the dominant role of knowledge as a mediator and the strong direct influence of contextual factors on attitudes.

Figure 4. Model of effective teaching practices for secondary special education teachers. : Big influence;

: small influence.

The study’s findings have provided a clearer explanation of the role of personal factors as a more proactive agent in determining the dual choices in special education teachers’ lives to achieve their desired outcomes. Practically, this study has implications for empowering teachers’ knowledge and beliefs, which should be prioritized in teacher training programs and school administrators’ professional development programs. This approach is crucial for ensuring that special education programs and related initiatives receive the necessary support for development and emerge as programs that contribute pride to schools.

5.5 Limitations and suggestions for future research

Despite undertaking a comprehensive investigation and employing necessary measures, this study is subject to several limitations. First, a quantitative approach based on self-assessment was used in this study. Such techniques tend to yield socially desirable responses, where the respondents may present themselves more favorably than their actual practices. This approach may limit the accuracy of the findings. Thus, to minimize this issue in future research, it is recommended to adopt mixed methods approaches, such as incorporating classroom observations, interviews, and data triangulation, potentially resulting in richer insights and validating self-reported data.

Second, this study did not consider the influence of contextual factors within families or communities outside of school, which play an important role in student development. Therefore, future research should expand the study’s scope to examine these factors, as this approach would enrich educational policy planning and foster stronger collaboration across various fields of expertise. Third, this study focused only on special education teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. Further investigations should explore additional domains, such as legal knowledge and related theoretical frameworks, since their connections to teaching practices remain underexplored.

Fourth, although stratified random sampling was employed, the study was limited to one state from each of the five zones. Consequently, the representativeness and generalizability of the findings were restricted. Future studies are encouraged to increase the number of participating states and respondents to ensure broader inclusion of special education teachers across all zones. Stratified sampling could also be extended to underrepresented areas to capture more diverse perspectives. Additionally, respondents can be assigned unique identification codes to maintain confidentiality while enabling detailed analysis. Finally, the criteria for respondents in this study were relatively specific. Future research should consider broadening the scope by including primary special education teachers and administrators, thereby capturing a more comprehensive perspective of teaching practices in special education. By addressing these limitations, subsequent studies can generate more valid, representative, and impactful findings contributing to policy development and practice.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical and confidentiality considerations. Requests to access the data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UKM Research Ethics Committee (Human). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KK: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia under Grant TAP-K020059 and GG-2024-051.

Acknowledgments

We express our heartfelt gratitude to all the officers from the Department of Education and District Education Offices and the special education teachers in schools who were directly and indirectly involved in the data collection process. We would like to thank the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for supporting the publication of this article under GG-2024-063 grant and the Tabung Agihan Penyelidikan grant.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aas, H. K. (2022). Teachers talk on student needs: exploring how teacher beliefs challenge inclusive education in a Norwegian context. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 495–509. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1698065

Abduh, B., Khairuddin, K. F., Tahar, M. M., and Zainal, M. S. (2025). Special educational teacher contextual scale (SETCS): adaptation and psychometric testing. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 40, 199–209. doi: 10.52291/ijse.2025.40.16

Abramczyk, A., and Jurkowski, S. (2020). Cooperative learning as an evidence-based teaching strategy: what teachers know, believe and how they use it. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 296–308. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1733402

Alesech, J., and Nayar, S. (2021). Teacher strategies for promoting acceptance and belonging in the classroom: a New Zealand study. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 1140–1156. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1623323

Alexander, M., and Byrd, D. R. (2020). Investigating special education teachers’ knowledge and skills: preparing general teacher preparation for professional development. J. Pedagog. Res. 4, 72–82. doi: 10.33902/JPR.2020059790

Alshoura, H. (2021). Critical review of special needs education provision in Malaysia: discussing significant issues and challenges faced. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 70, 869–884. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2021.1913718,

Alsolami, A. S. (2022). Teachers of special education and assistive technology: teachers’ perceptions of knowledge, competencies, and professional development. SAGE Open 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/21582440221079900

Antoniou, A. S., Efthymiou, V., Polychroni, F., and Kofa, O. (2023). Occupational stress in mainstream and special needs primary school teachers and its relationship with self-efficacy. Educ. Stud. 49, 200–217. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1837080

Awang, Z., Lim, S. H., and Zainudin, N. F. S. (2018). Pendekatan mudah SEM: Structural equation modelling. Bandar Baru Bangi: MPWS.

Awang, Z., Wan Afthanorhan, W. M., Lim, S. H., and Zainudin, N. F. S. (2023). SEM made simple 2.0: a gentle approach of structural equation modelling. Bandar Baru Bangi: Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin.

Bahagian Pendidikan Khas, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia (2023) Data pendidikan khas tahun 2023 Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia. Putrajaya.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191,

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1999). “A social cognitive theory of personality” in Handbook of personality. eds. L. Pervin and O. John. 2nd ed (New York: Guilford Publications), 154–196.

Basckin, C., Strnadová, I., and Cumming, T. M. (2021). Teacher beliefs about evidence-based practice: a systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 106:101727. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101727

Benigno, V., Usai, F., Mutta, E. D., Ferlino, L., and Passarelli, M. (2024). Burnout among special education teachers: exploring the interplay between individual and contextual factors. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 40, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2024.2351702

Billingsley, B., Bettini, E., Mathews, H. M., and McLeskey, J. (2020). Improving working conditions to support special educators’ effectiveness: a call for leadership. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 43, 7–27. doi: 10.1177/0888406419880353

Binammar, S., Alqahtani, A., and Alnahdi, G. H. (2023). Factors influencing special education teachers’ self-efficacy to provide transitional services for students with disabilities. Front. Psychol. 14, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1140566,

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. New York: David McKay Company.

Boe, E. K., and Cook, L. H. (2006). The chronic and increasing shortage of fully certified teachers in special and general education. Except. Child. 72, 443–460. doi: 10.1177/001440290607200404

Börnert-Ringleb, M., Casale, G., and Hillenbrand, C. (2021). What predicts teachers’ use of digital learning in Germany? Examining the obstacles and conditions of digital learning in special education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 80–97. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872847

Braksiek, M. (2022). Pre-service physical education teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive physical education: subject specificity and measurement invariance. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12662-021-00755-1

Breyer, C., and Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (2024). The relative significance of contextual, process and individual factors in the impact of learning and support assistants on the inclusion of students with SEN. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 28:510. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2023.2184510

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Cansoy, R., Parlar, H., and Polatcan, M. (2022). Collective teacher efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between instructional leadership and teacher commitment. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 25, 900–918. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1708470

Chen, X., Zhong, J., Luo, M., and Lu, M. (2020). Academic self-efficacy, social support, and professional identity among preservice special education teachers in China. Front. Psychol. 11:374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00374,

Cook, C. E., Bailliard, A., Bent, J. A., Bialosky, J. E., Carlino, E., Colloca, L., et al. (2023). An international consensus definition for contextual factors: findings from a nominal group technique. Front. Psychol. 14:1178560. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1178560,

Cornelius, K. E., Rosenberg, M. S., and Sandmel, K. N. (2020). Examining the impact of professional development and coaching on mentoring of novice special educators. Action Teach. Educ. 42, 253–270. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2019.1638847

Corso-de-Zúñiga, S., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Garrosa, E., Blanco-Donoso, L. M., and Carmona-Cobo, I. (2020). Personal resources and personal vulnerability factors at work: an application of the job demands-resources model among teachers at private schools in Peru. Curr. Psychol. 39, 325–336. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9766-6

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., and Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 97–140. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

Dignath, C., Rimm-Kaufman, S., van Ewijk, R., and Kunter, M. (2022). Teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education and insights on what contributes to those beliefs: a meta-analytical study. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2609–2660. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09695-0,

Eiser, J. R. (1986). Social psychology: Attitudes, cognition and social behaviour. 2nd Edn. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Finlay, C., Kinsella, W., and Prendeville, P. (2022). The professional development needs of primary teachers in special classes for children with autism in the Republic of Ireland. Prof. Dev. Educ. 48, 233–253. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1696879

Fitzgerald, A. (2020). Professional identity: a concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 55, 447–472. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12450,

Fu, W., Tang, W., Xue, E., Li, J., and Shan, C. (2021). The mediation effect of self-esteem on job burnout and self-efficacy of special education teachers in Western China. Int. J. Dev. Disabilit. 67, 273–282. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2019.1662204,

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers’ assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Glenn, C. V. (2018). The measurement of teacher’s beliefs about ability: development of the beliefs about learning and teaching questionnaire. Excep. Educ. Int. 28, 51–66. doi: 10.5206/eei.v28i3.7771,

Granger, K. L., Chow, J. C., Broda, M. D., Pandey, T., and Sutherland, K. S. (2024). A preliminary investigation of the role of classroom contextual effects on teaching efficacy and classroom quality. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 68, 103–112. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2022.2161457

Grotkamp, S. L., Cibis, W. M., Nüchtern, E. A. M., von Mittelstaedt, G., and Seger, W. K. F. (2012). Personal factors in the international classification of functioning, disability and health: prospective evidence. Aust. J. Rehabil. Couns. 18, 1–24. doi: 10.1017/jrc.2012.4

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Limited.

Hazan-Liran, B., and Karni-Vizer, N. (2024). Psychological capital as a mediator of job satisfaction and burnout among teachers in special and standard education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 337–351. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2215009

Heyder, A., Südkamp, A., and Steinmayr, R. (2020). How are teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion related to the social-emotional school experiences of students with and without special educational needs? Learn. Individ. Differ. 77:101776. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101776

Johnson, E. S., Crawford, A. R., Moylan, L. A., and Zheng, Y. (2017) Explicit instruction rubric manual: Table of contents [Manual] Boise State University. Available online at: https://idahotc.com/Portals/0/Resources/911/Explicit%20Instruction%20Rubric%20Manual.pdf (Accessed July, 2021).

Johnson, E., and Semmelroth, C. (2012). Examining interrater agreement analyses of a pilot special education observation tool. J. Spec. Educ. Apprenticesh. 1:9. doi: 10.58729/2167-3454.1014

Klang, N., Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Nilholm, C., Hansson, S., and Bengtsson, K. (2020). Instructional practices for pupils with an intellectual disability in mainstream and special educational settings. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 67, 151–166. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2019.1679724

Kozma, R. B. (2003). ICT and educational change: A global phenomenon. Dlm. Kozma, R.B. (pnyt). Technology, innovation, and educational change: A global perspective hlm. 1–18. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Küçüközyiğit, M. S., Könez, N. A., and Yilmaz, B. (2017). Developing an attitude scale towards special education as a teaching profession: a test study. J. Int. Soc. Teach. Educ. 21, 27–40.

Kunz, A., Luder, R., and Kassis, W. (2021). Beliefs and attitudes toward inclusion of student teachers and their contact with people with disabilities. Front. Educ. 6:650236. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.650236

Kvande, M. N., Bjørklund, O., Lydersen, S., Belsky, J., and Wichstrøm, L. (2019). Effects of special education on academic achievement and task motivation: a propensity-score and fixed-effects approach. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 409–423. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1533095

Lan, Y. (2024). Through tensions to identity-based motivations: exploring teacher professional identity in artificial intelligence-enhanced teacher training. Teach. Teach. Educ. 151:104736. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104736

Lazarides, R., and Warner, L. M. (2020). “Teacher self-efficacy” in Oxford research encyclopedia of education. ed. G. W. Noblit (New York: Oxford University Press), 1–22.

Lera, M. J., Leon-Perez, J. M., and Ruiz-Zorrilla, P. (2023). Effective educational practices and students’ well-being: the mediating role of students’ self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 42, 22137–22147. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03266-w

Lim, C. Y. (2021) The Relationship between teachers’ attitude, self-efficacy, character strength towards pedagogy of love for special education preschool teachers in Malaysia (Tesis kedoktoran tidak diterbitkan). Bandar Baru Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Maag, J. W. (2020). The improbable challenge of managing students’ challenging behaviors in schools: professional reflections from a 30-year career. Adv. Educ. Res. Eval. 2, 93–100. doi: 10.25082/AERE.2020.01.004

Mason-Williams, L., Bettini, E., Peyton, D., Harvey, A., Rosenberg, M., and Sindelar, P. T. (2020). Rethinking shortages in special education: making good on the promise of an equal opportunity for students with disabilities. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 43, 45–62. doi: 10.1177/0888406419880352

Massé, L., Nadeau, M. F., Gaudreau, N., Nadeau, S., Gauthier, C., and Lessard, A. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward students with behavioral difficulties: associations with individual and education program characteristics. Front. Educ. 7:846223. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.846223

Mastrothanasis, K., Zervoudakis, K., and Xafakos, E. (2021). Secondary special education teachers’ beliefs towards their teaching self-efficacy. Preschool Prim. Educ. 9:28. doi: 10.12681/ppej.24646

Mathews, H. M., and Myers, A. M. (2022). The role of teacher self-efficacy in special education teacher candidates’ sensemaking: a mixed-methods investigation. Remedial Spec. Educ. 44, 209–224. doi: 10.1177/07419325221101812,

Mihat, N. (2019). Teachers’ views on classroom infrastructure facilities in special education integration program in primary school. J. ICSAR 3, 54–57. doi: 10.17977/um005v3i12019p054

Moberg, S., Etsuko, M., Korenaga, K., Kuorelahti, M., and Savolainen, H. (2020). Struggling for inclusive education in Japan and Finland: teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 1–24.

Moshagen, M., and Bader, M. (2024). semPower: general power analysis for structural equation models. Behav. Res. Methods 56, 2901–2922. doi: 10.3758/s13428-023-02254-7,

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332. doi: 10.3102/00346543062003307

Pardosi, J., and Utari, T. I. (2022). Effective principal leadership behaviors to improve the teacher performance and the student achievement. F1000Res 10:51549. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.51549.2,

Parey, B. (2019). Understanding teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with disabilities in inclusive schools using mixed methods: the case of Trinidad. Teach. Teach. Educ. 83, 199–211. doi: 10.1016/J.TATE.2019.04.007

Park, E. Y., and Shin, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of special education teachers’ burnout. SAGE Open 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2158244020918297

Perrin, A. L., Jury, M., and Desombre, C. (2021). Are teachers’ personal values related to their attitudes toward inclusive education? A correlational study. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 1085–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09646-7

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879,

Rizvi Jafree, S., Burhan, S. K., and Mahmood, Q. K. (2023). Predictors for stress in special education teachers: policy lessons for teacher support and special needs education development during the COVID pandemic and beyond. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 33, 615–632. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2022.2077498

Sabarwal, S., Abu-Jawdeh, M., and Kapoor, R. (2022). Teacher beliefs: why they matter and what they are. World Bank Res. Obs. 37, 73–106. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkab008

Saloviita, T. (2020). Attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education in Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 64, 270–282. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2018.1541819

Schwab, S., and Alnahdi, G. H. (2020). Do they practise what they preach? Factors associated with teachers’ use of inclusive teaching practices among in-service teachers. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 20, 321–330. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12492

Smale-Jacobse, A., Moorer, P., Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Fernández-García, C. M., Inda-Caro, M., et al. (2023). “Exploring how teachers’ personal characteristics, teaching behaviors, and contextual factors are related to differentiated instruction in the classroom: a cross-national perspective” in Effective teaching around the world: Theoretical, empirical, methodological and practical insights. eds. R. M. Klassen, M. L. Niessen, and S. A. Burns (London: Springer), 509–540.

Sonmark, K., Révai, N., Gottschalk, F., Deligiannidi, K., and Burns, T. (2017). Understanding teachers’ pedagogical knowledge: Report on an international pilot study (OECD education working papers no. 159). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Starks, A. C., and Reich, S. M. (2023). “What about special ed?”: barriers and enablers for teaching with technology in special education. Comput. Educ. 193:104665. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104665

Stewart, A. L., Thrasher, A. D., Goldberg, J., and Shea, J. A. (2012). A framework for understanding modifications to measures for diverse populations. J. Aging Health 24, 992–1017. doi: 10.1177/0898264312440321,

Straub, D., Gefen, D., and Boudreau, M.-C. (2004). Validation guidelines for IS positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 13, 380–427. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01324

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics. 7th Edn. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson.

Taherdoost, H. (2016). Validity and reliability of the research instrument: how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 5, 28–36. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3205040

Taresh, S., Ahmad, N. A., Roslan, S., and Ma’rof, A. M. (2020). Preschool teachers’ knowledge, belief, identification skills, and self-efficacy in identifying autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a conceptual framework to identify children with ASD. Brain Sci. 10:165. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10030165,

Toropova, A., Myrberg, E., and Johansson, S. (2021). Teacher job satisfaction: the importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educ. Rev. 73, 71–97. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2019.1705247

Trafimow, D., Sheeran, P., Lombardo, B., Finlay, K. A., Brown, J., and Armitage, C. J. (2004). Affective and cognitive control of persons and behaviours. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 207–224. doi: 10.1348/0144666041501642,

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Watkins, M. W. (2021). A step-by-step guide to exploratory factor analysis with R and RStudio. New York: Routledge.

Werner, S., Gumpel, T. P., Koller, J., Wiesenthal, V., and Weintraub, N. (2021). Can self-efficacy mediate between knowledge of policy, school support and teacher attitudes towards inclusive education? PLoS One 16:e0257657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257657,

Whitley, B. E., Kite, M. E., and Adams, H. L. (2013). Principles of research in behavioral science. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Williams, L. J., and O’Boyle, E. H. Jr. (2008). Measurement models for linking latent variables and indicators: a review of human resource management research using parcels. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 18, 233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.07.002

Yeh, C., Ellis, M., and Mahmood, D. (2020). From the margin to the center: a framework for rehumanizing mathematics education for students with dis/abilities. J. Math. Behav. 58:100758. doi: 10.1016/j.jmathb.2020.100758

Keywords: effective teaching practices, special education teachers, contextual factors, teachers’ beliefs, teachers’ knowledge, structural equation modelling

Citation: Abduh B, Khairuddin KF and Zainal MS (2026) An effective teaching model for special education teachers in Malaysia: the mediating role of personal factors between contextual factors and teaching practices. Front. Educ. 10:1663380. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1663380

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Elena Olmos-Raya, University of La Laguna, SpainAnthea Gara Santos Álvarez, University of La Laguna, Spain

Copyright © 2026 Abduh, Khairuddin and Zainal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Khairul Farhah Khairuddin, a2ZrQHVrbS5lZHUubXk=

Bungawali Abduh

Bungawali Abduh Khairul Farhah Khairuddin

Khairul Farhah Khairuddin Mohd Syazwan Zainal

Mohd Syazwan Zainal