- 1School of International Education, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 2Ocean College, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan, Zhejiang, China

- 3Institute of Technology Transfer, Zhejiang University, Ningbo, China

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers a powerful approach to analyze teaching and learning data, which has brought the promising field of AI in education (AIEd) and, particularly, opened new opportunities, potentials and challenges for higher education. The capability of AI has made AIEd widely sought-after as an accurate and efficient approach to predict learning performance while designing teaching strategy. However, it remains challengeable to obtain customized higher education to fit specific requirements of students and satisfy their personalized needs. Recent development in AI algorithms has made it possible to realize automatic update of students' learning performance information, i.e., performance-informed AI (PI-AI). Here, this study first overviews the debut and recent development of AI in higher education, highlighting the PI-AI strategy to maximize teaching and learning performance. Next, we specifically develop a learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP) model to showcase the application of PI-AI in a case study of a higher ocean engineering course, building on the experimental results of our study, which demonstrated that the LEI-GP model's accuracy in predicting student performance is reasonable, with a maximum Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 5%. The emerging LEI-GP model is updated with the physiological data of students in learning, which is connected to a high-performance chip system to address the learning data in a real-time wireless manner. Eventually, we provide insights into the PI-AI in propelling real-life customized higher ocean engineering education. PI-AI is an emerging scientific direction in AIEd, which is expected to balance the dilemma between the generalized and customized learning in higher engineering education and address the concern on the design and optimization of its instructional design and teaching strategy.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), referring to intelligent machines that attempt to mimic human cognition, has been extensively used as a complementary paradigm to address the complex problems that are difficult, if not impossible, to solve using the conventional approaches (Segal, 2019). AI in education (AIEd) has been a prospect field due to the rapid development of computing and information processing techniques, which has led to the debuts of adaptive learning systems, intelligent tutoring systems, human-computer interactions and teaching robots in recent years (Ouyang and Jiao, 2021). AI plays a key role in facilitating new paradigms for instructional design, technological development and education research as it is a powerful tool to analyze teaching and learning data in a real-time manner (Chen et al., 2020a,b; Ouyang et al., 2022a). AIEd has opened new opportunities, potentials and challenges for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education (Ouyang et al., 2022b), which has undergone the paradigmatic shifts from the initial AI-directed learner-as-recipient, to later AI-supported learner-as-collaborator, and currently AI-empowered learner-as-leader (Ouyang and Jiao, 2021; Starčič, 2019; Riedl, 2019; Hwang et al., 2020). In this latter paradigm, AI enables learners to take on a more autonomous and proactive role in their education, where they are not only recipients of knowledge but also actively guide their learning process and make personalized decisions based on real-time feedback and data analysis (Hwang et al., 2020). The AI-directed and AI-supported models have been reported as accurate and efficient approaches to predict learning performance while designing teaching strategy (Ouyang et al., 2023). For example, a genetic programming (GP) model was developed to predict the teaching effectiveness and learning performance of the college students in ocean engineering (Jiao et al., 2022). AI tool was reported to analyze the discussion patterns, perceptions, and preferences of students in a massive open online course (MOOC; Ouyang et al., 2020). However, offering precise, personalized learning pathways and support for each student in engineering education remains challenging. Traditional AI in education refers to systems that operate based on fixed rules or logic to make decisions (Tang et al., 2021; Luckin and Holmes, 2016). These systems rely on a few static input variables (e.g., key learning indicators such as student background, classroom participation, and assignment scores) to predict individual learning performance, but this approach fails to effectively utilize real-time physiological and behavioral data during the learning process, neglecting individual differences among students and leading to suboptimal personalized learning outcomes (Ouyang and Jiao, 2021; Wang et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2021).

Performance-informed AI (PI-AI) is a personalized AI system designed to continuously update students' learning performance in real-time by integrating physiological data, such as biosensor readings (Antoniou et al., 2020; McNeal et al., 2020), with advanced AI models (Chen et al., 2022; Deeva et al., 2021). The emerging PI-AI strategy is designed with a variety of biosensors to collect physiological data of students in learning (Giannakos et al., 2019), a high-performance chip system to address the learning data in a real-time wireless manner (Mountrakis and Triantakonstantis, 2012), and an AI model that can be updated with respect to the learning data (Jiao et al., 2022). This approach ensures that each student's progress is closely tracked and adjusted in real-time, offering more tailored and effective learning than traditional systems relying on static inputs. PI-AI is envisioned as an emerging scientific direction in AIEd, which can balance the dilemma between the inaccuracy of generalized learning and the low efficiency of customized learning. In addition, PI-AI can address the concern on the design and optimization of instructional design and teaching strategy in higher engineering education. However, few studies have systematically examined to discuss this emerging research direction, neither has PI-AI strategy been reported to showcase its outcome and advantage in higher engineering education.

Here, this study first discusses the main characteristics of AI in higher engineering education, and then overviews the debut and recent development of PI-AI while summarizing its application paradigms to maximize teaching and learning performance. PI-AI systems are particularly discussed in the contexts of integrating with various biosensors, developing wireless chips to real-time analyze monitoring data, and automatically updating AI models by the learning data to conduct customized teaching. To showcase the application of PI-AI in higher engineering education, we develop the learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP) system for Smart Marine Metastructures—a higher ocean engineering course that the author offered at one of the top universities in China, aiming to examine how effectively the LEI-GP model can predict student performance in real-time learning environments using biometric and behavioral data. Most existing AI models in education are often static and fail to utilize real-time physiological and behavioral data fully. In contrast, the emerging LEI-GP model integrates learning effectiveness with genetic programming to update in real-time using physiological data collected from students during learning, connecting to a high-performance chip system that enables wireless processing of this data, thus allowing for more personalized, accurate predictions of learning outcomes. Eventually, we provide insights into the PI-AI strategy in propelling real-life customized higher engineering education.

Artificial intelligence in higher education from an engineering perspective

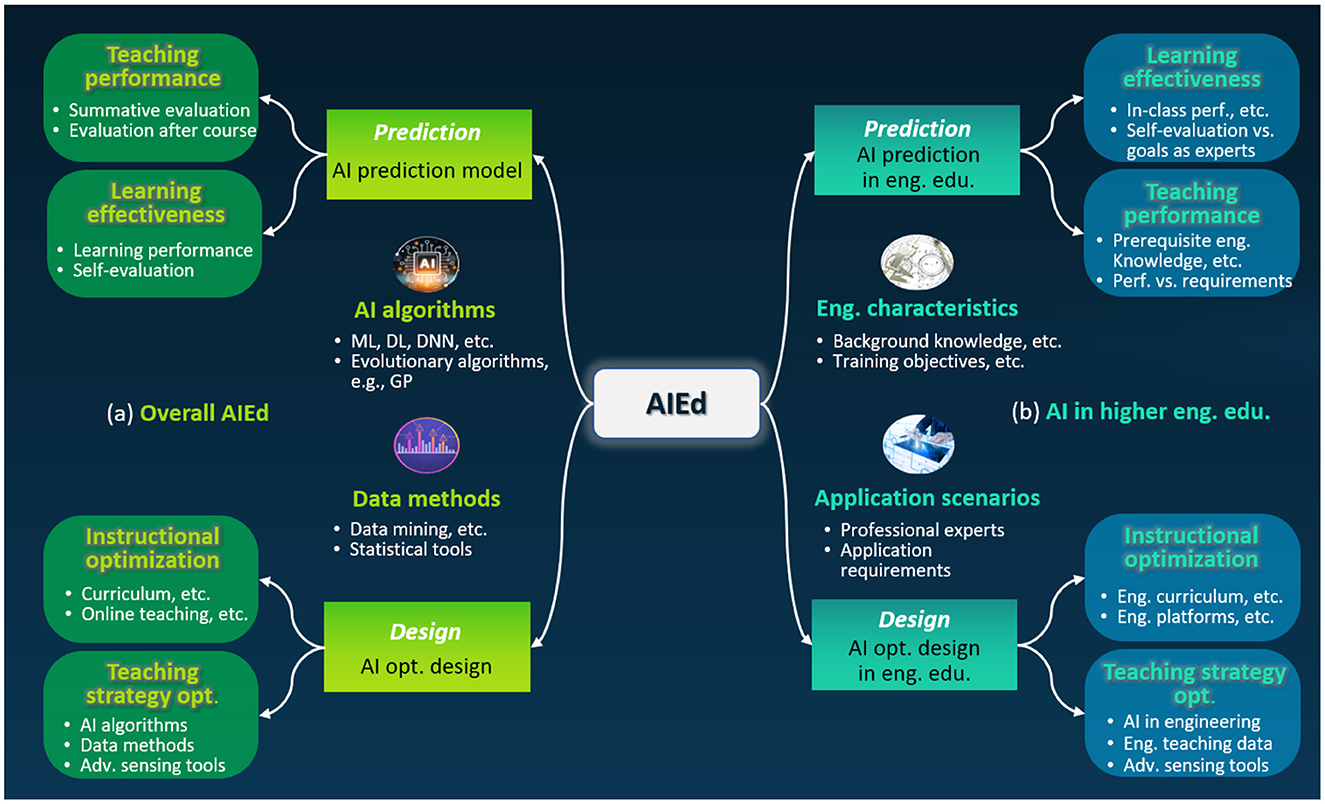

After AI demonstrated its power in data processing and analysis, AIEd has debuted as a powerful tool nearly three decades ago, expanding to achieve new paradigms in higher engineering education such as instructional design, technological development and education research (Chen et al., 2020b; Baker, 2000). Figure 1 demonstrates the current progress of AIEd. Figure 1a summarizes the overall AIEd that is generalized for all subjects. Performance prediction and education design are two major directions of recent AIEd, including teaching performance and learning effectiveness predictions for the former, and instructional and teaching strategy optimizations for the latter. Data methods and AI algorithms are two main foundations for the development and applications of AIEd. Until now, various AI algorithms have been used to create intelligent teaching and learning environments for performance prediction, behavior detection or learning recommendation, such as natural language processing (NLP; Litman, 2016), machine learning (ML; Alenezi and Faisal, 2020), deep learning (DL; Perrotta and Selwyn, 2019), artificial neural networks (ANNs; Okewu et al., 2021), etc. For example, a GP model was developed to predict the learning effectiveness of graduate students in a higher ocean engineering course (Jiao et al., 2022). The authors obtained a quantitative relationship between the key input variables in learning and the output variable of learning effectiveness. An AI evaluation model was developed for sports teaching using the NN algorithms for data training and analysis (Zhang, 2021). The author particularly introduced a new decoder to perform data processing and a simplified gated NN internal structure diagram to build the internal structure of the model.

Figure 1. Current progress of AIEd. Four aspects of teaching performance, learning effectiveness, instructional optimization and teaching strategy optimization in (a) overall AIEd that is generalized for all subjects, and (b) AI in higher engineering education that is specialized for the characteristics and application scenarios of engineering courses.

Comparing with the AIEd models in other fields, AI in higher engineering education exhibits the uniqueness mainly due to its engineering-related characteristics and application scenarios. Figure 1b demonstrates the current development of AI in higher engineering education from the two aspects of prediction and design as well. However, the engineering applications leads to the fact that AI needs to focus on the specific prerequisite knowledge, training objects, application requirements, etc. As a consequence, AI in higher engineering education requires personalized learning, weakening the role of instructors, and depending on data-based and -driven educational hardware systems (Bajaj and Sharma, 2018), which is expected to provide higher engineering education with new opportunities, potentials and challenges (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019; Popenici and Kerr, 2017; Hinojo-Lucena et al., 2019). However, the application of AI in higher engineering education is still at the early stage, which results in the issues of understanding how to integrate AI with the advanced sensing technologies and to what extent the use of AI technologies influence learning and instruction (Ouyang and Jiao, 2021; Kabra and Bichkar, 2011; Khan and Ghosh, 2021).

AI in higher engineering education faces the challenges in customizing the data-driven technology, such as answering the questions of how to clarify and meet learners' needs, what to provide to learners, when and how to empower learners' capability of own learning, etc. (Sekeroglu et al., 2019). Although AI significantly empowers advanced information processing and computing technologies, good educational outcomes and high-quality learning do not necessarily come along (Albreiki et al., 2021). This is because higher engineering education typically requires time-dependently individual monitoring and analysis, rather than simply applying the existing AI tools (Ouyang, 2023). To this end, we propose PI-AI and particularly develop the LEI-GP model as a case study in a higher ocean course, demonstrating the practice, research and development of the next-generation AI system in higher engineering education.

Emerging performance-informed artificial intelligence (PI-AI)

Improving traditional instructor-dominated classrooms, AIEd has successfully established the new learner-centralized paradigms in higher engineering education. However, AIEd has been facing the crucial challenges in updating student performance with time, customizing the unique needs of individuals, accurately identifying the key factors (i.e., input variables) in teaching, and requiring a large amount of raw data. Current physics-informed AI models have mainly been reported in engineering or management-related research fields (Karniadakis et al., 2021; Raabe et al., 2023, 2019). For example, the physics-informed NN model was developed to solve complex nonlinearly partial differential equations in heat transfer (Zobeiry and Humfeld, 2021). The informed AI (IAI) was reported by integrating human domain knowledge into AI to develop effective and reliable data labeling and modeling processes for social media datasets (Johnson et al., 2022). However, lack of study has been carried out on physics-informed AI in education. To address such research gap, here we present PI-AI to enable customized higher ocean engineering education. Taking advantage of predefined instructions between input and output variables, PI-AI is the prediction and design strategy that can be automatically updated for each student in every class hour, improve the accuracy and efficiency while reducing the need for large amount of raw data.

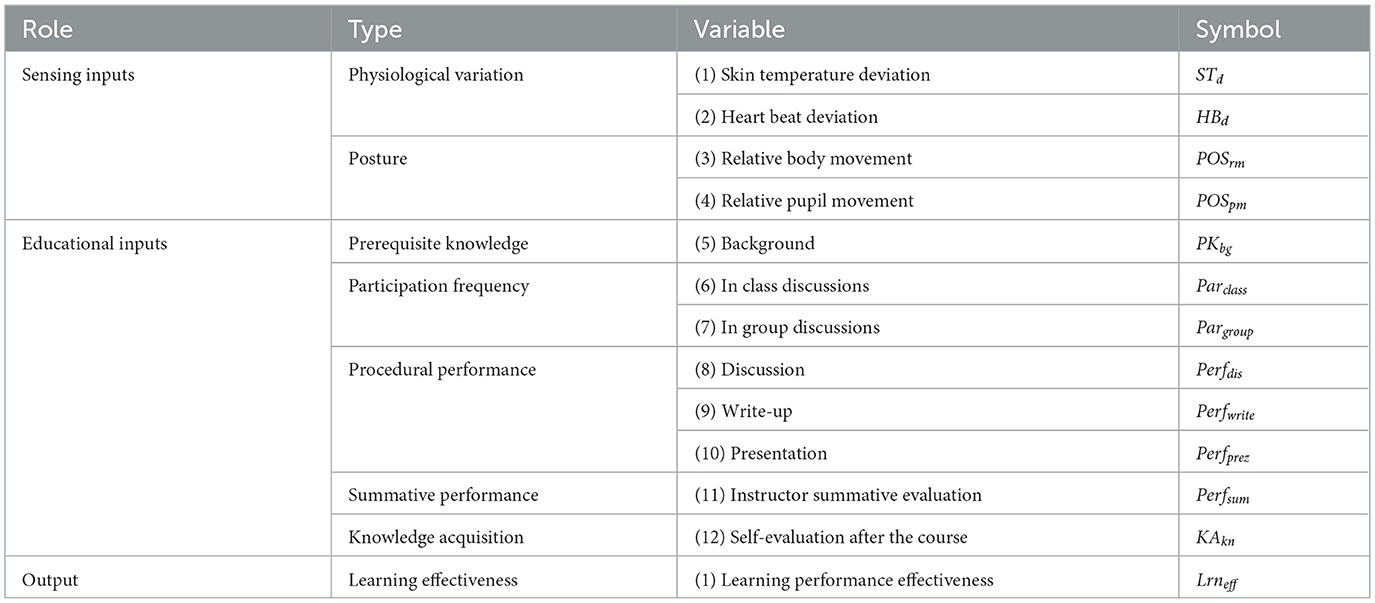

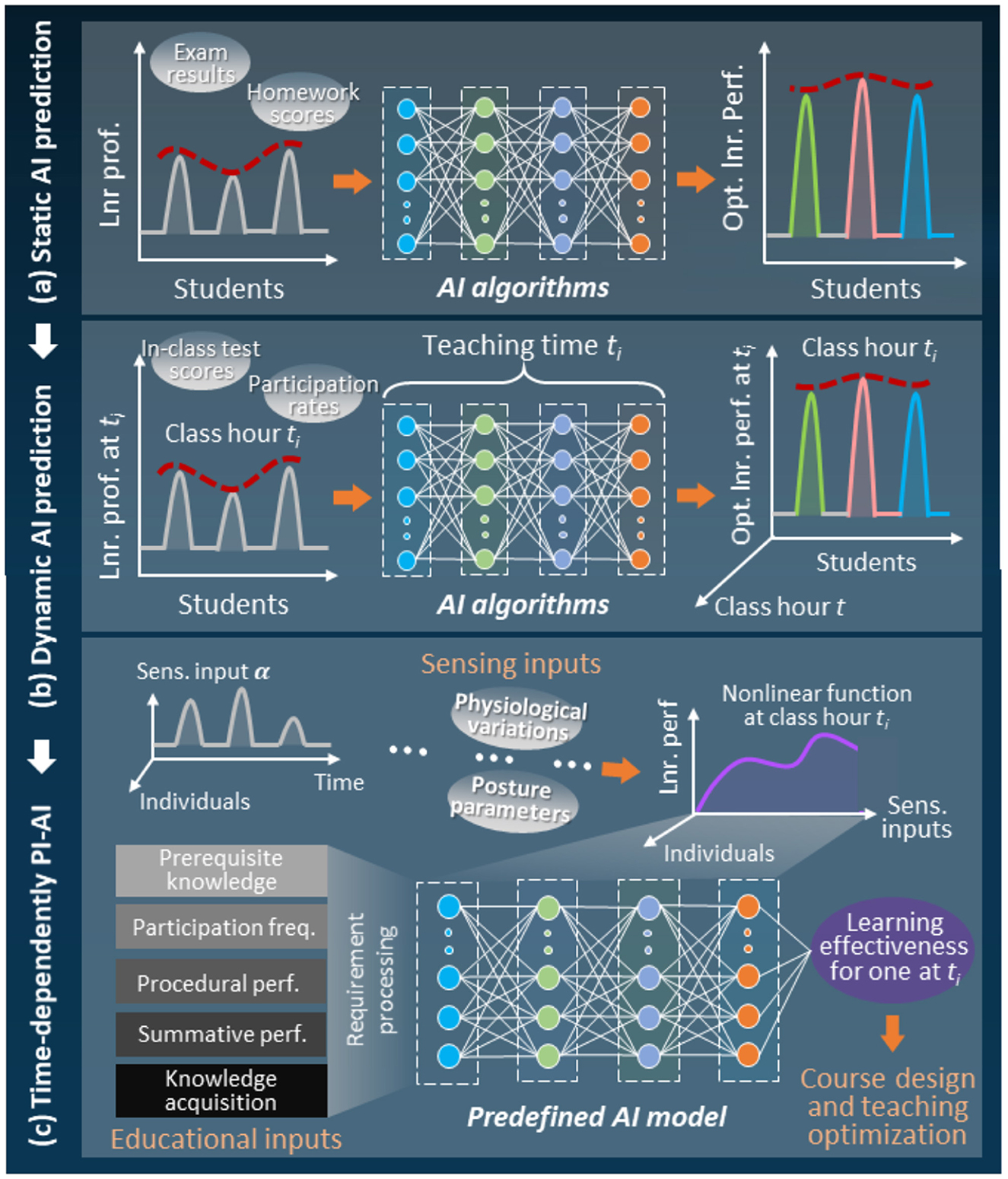

Figure 2 systematically demonstrates the evolutionary shifting of AI strategies for learning performance prediction in higher engineering education. The trajectory starts with the initial static AI prediction models: these models rely solely on fixed historical learning data (such as past semester exam results and overall homework scores) and cannot be updated with the dynamic changes of students' learning processes. This limitation leads to a gradual decline in prediction accuracy as the teaching process progresses, failing to meet the needs of real-time teaching adjustment. Subsequently, the recent dynamic AI prediction models introduce class hour-based correction mechanisms. They integrate cumulative learning data from each class hour (e.g., in-class test scores, group discussion participation rates) to adjust prediction results. However, these models ignore the individual differences in students' learning rhythms and real-time status, thus unable to achieve personalized learning support. The emerging time-dependently individual PI-AI models represent a breakthrough in addressing the customization challenge of higher engineering education. PI-AI realizes automatic update of students' learning performance information by sensing key individual performance indicators in different class hours. The key sensing inputs include physiological variations (skin temperature, heart beat deviations) and posture parameters (relative body movements, pupil fluctuations; see Table 1 for specific parameter ranges and measurement methods). These real-time data are transmitted to a high-performance chip system for wireless real-time processing, ensuring that the PI-AI model can dynamically adjust its prediction logic based on each student's instant learning status. In practical application, the PI-AI model expands the function of existing AI prediction models by incorporating real-time sensing data. For example, in higher ocean engineering courses, it can accurately predict each student's learning effectiveness at every class hour, with a prediction deviation controlled within a reasonable range. This accurate prediction further supports the optimization of course design—such as adjusting the difficulty of knowledge points in subsequent classes according to students' real-time mastery—and the customization of teaching strategies, such as providing targeted guidance for students with low real-time performance. Compared with static and traditional dynamic AI models, PI-AI effectively balances the dilemma between generalized and customized learning in higher engineering education, making it a core technical support for the development of AIEd in higher engineering fields.

Figure 2. Strategy shifting of AI models for learning performance prediction in higher engineering education. It illustrates the evolutionary trajectory of AI-based strategies for predicting student learning performance and supporting teaching optimization in higher engineering education, spanning three key developmental stages: (a) initial static AI prediction models: These models lack the capability of temporal update, relying on fixed historical learning data for one-time prediction. (b) Recent dynamic AI prediction models: compared with static models, these models introduce class hour-based correction mechanisms. (c) Emerging time-dependently individual Performance-Informed AI (PI-AI) models: these models achieve real-time adaptive updates by sensing key individual performance indicators across different class hours.

Learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP): a case study from higher ocean engineering course

To showcase the application of PI-AI in higher engineering education, here we develop a learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP) model to showcase the customized prediction (i.e., updated with students and class hours) in a higher ocean engineering course. The time-dependently individual LEI-GP model is developed based on Smart Marine Metastructures—a course offered by the author in Spring semester (32 h 2 credits in 8 weeks) at Zhejiang University, China. In particular, the course was offered as online-and-offline hybrid, where the online classroom was built on the DingTalk (Zoom-like platform in China) and the blackboard online platform (XueZaiZheDa http://course.zju.edu.cn/). The participants included 35 full-time master and PhD candidates in the Ocean College at the university, who were all Chinese aged from 22 to 27 years old with the gender distribution of male-to-female as 24:11. The key performance of the students is characterized into the two groups of sensing and educational inputs. The former is further classified into five categories (i.e., the prerequisite, participation, procedural performance, summative performance and knowledge acquisition) and the latter is classified into the skin temperature and heart beat deviations in physiological variations and relative body and pupil movements in postures. The output variable is defined as the learning effectiveness Lrneff of the graduate students in the course, as listed in Table 1. Previous study reported the GP prediction model to define the relationship between the educational inputs and learning effectiveness as (Jiao et al., 2022),

where fedu represents the highly nonlinear objective function between the inputs and output. As a branch of the evolution algorithms that has high model transparency and knowledge extraction, GP can establish quantitatively nonlinear relationships for complex phenomena. Comparing with other “black box” algorithms such as ML, DL, DNN, etc., GP provides the quantitative relationships that can be further expanded or updated for different purposes. The detailed comparisons between the LEI-GP model and other models, as well as the detailed individual gene expressions, are provided in Sections 1 and 2 of Appendix A (Experiments and Methods), respectively. The simplified GP model was eventually given as (Jiao et al., 2022),

however, Equation 2 is a static relationship as the input variables are constant over the entire class (i.e., the inputs cannot be easily updated over time).

To address this issue, we develop the LEI-GP model by expanding the existing GP model with the real-time data collected by various biosensors (i.e., the sensing inputs in Table 1). The experimental reproducibility and scalability are provided in Sections 3 and 4 of Appendix A (Experiments and Methods). Using Equation 2 as the predefined learning effectiveness, the time-dependently individual LEI-GP model is obtained by updating with the sensing inputs of individual students in the physiological variation and posture. In particular, the LEI-GP model extends the existing GP model by incorporating sensing inputs (i.e., STd, HBd, POSrm, POSpm), which are automatically updated over class hours t. As a consequence, the LEI-GP model takes into account of the behavior of student in each class as:

where m = 32 is the class hour, are automatically updated with class hours t.

Taking class hour 1 as an example, the LEI-GP model was constructed. Initially, students' static data were collected via questionnaires as educational inputs. Subsequently, dynamic physiological data during class hour 1 were extracted. All data were then input into the GP model for real-time iterative updates. Therefore, the prediction model of class hour 2 is given as:

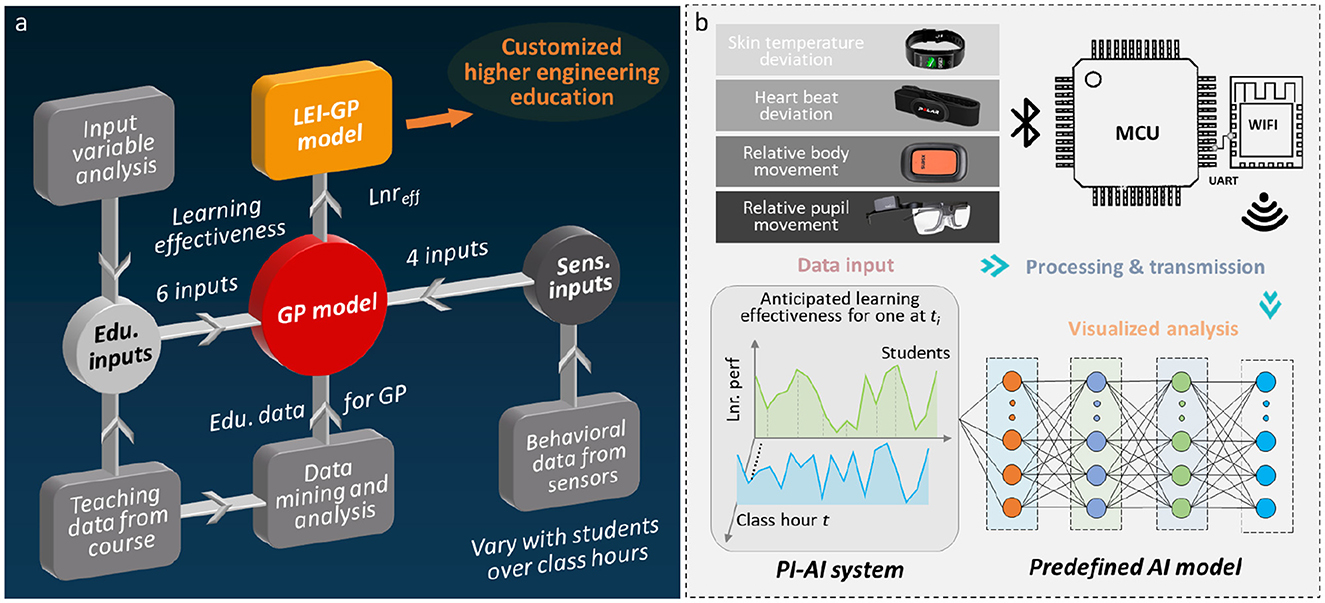

Figure 3a presents the development procedures of the LEI-GP model, which extends the existing GP model to customized higher engineering education by incorporating sensing inputs (i.e., STd, HBd, POSrm, POSpm) that are automatically updated over class hours t. Figure 3b depicts how the PI-AI system collects real-time behavioral data from students through various sensors. The wearable biosensors include a wireless transmission module interfacing with the chip system, which transmits physiological data—such as heart rate and posture—via a cloud interface for immediate analysis. Based on this data, the AI model continuously updates to deliver personalized instructional interventions and customized learning support.

Figure 3. Development procedures of the time-dependently LEI-GP model for PI-AI system. (a) The existing GP model is extended to customized higher engineering education by incorporating sensing inputs (i.e., STd, HBd, POSrm, POSpm) that are automatically updated over class hours t. (b) The operational workflow and anticipated learning outcomes of the PI-AI system.

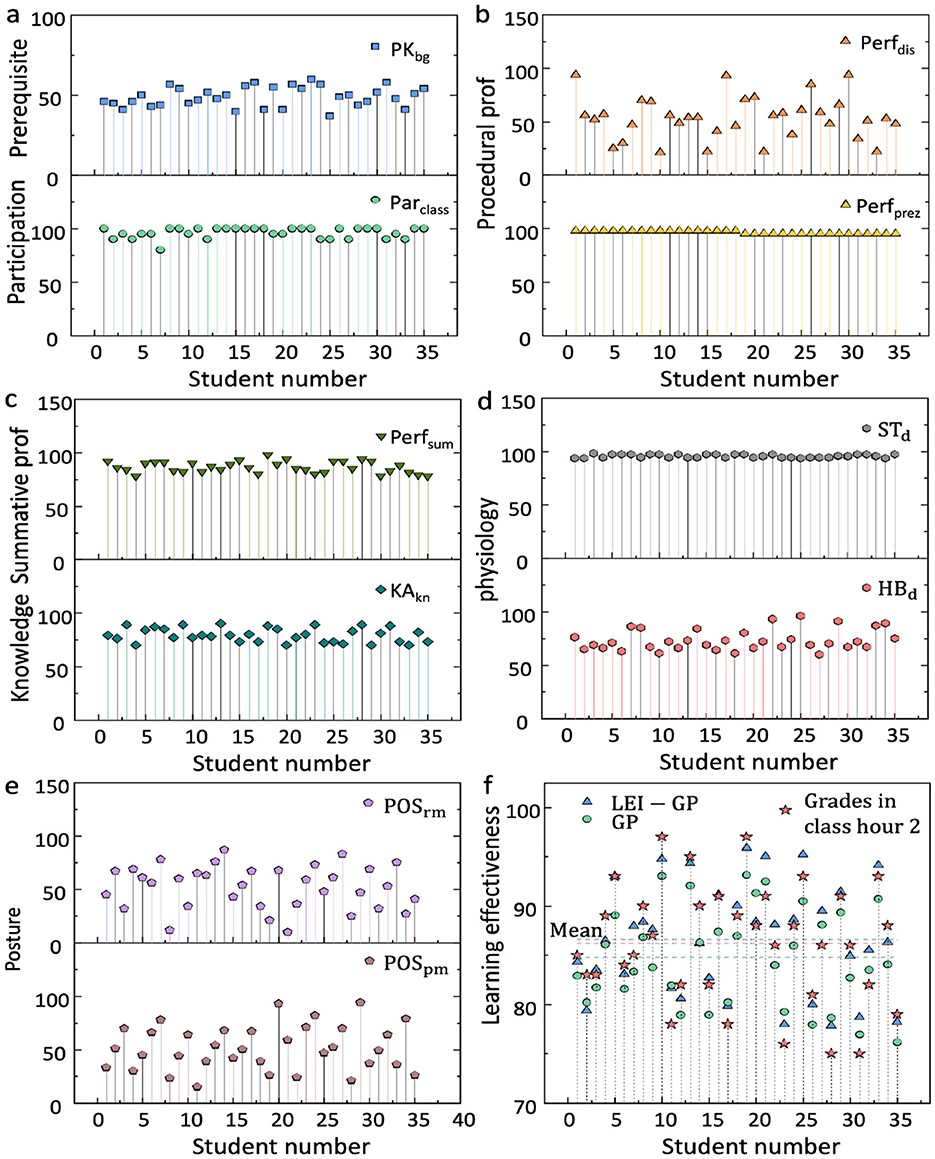

Figures 4a–e illustrate the input data used to predict student learning effectiveness during class hour 2, comprising eight educational inputs and four sensing inputs. Note that Pargroup and Perfwrite are omitted due to their similarity in the learning data. All input scores were normalized to a maximum of 100 points to ensure that the effects of certain variables were not diminished. Additionally, Figure 4f presents a comparison of the predicted student learning effectiveness for the class hour 2 generated by the LEI-GP and GP models, as well as the actual student scores obtained during the class hour 2. Compared with the GP model, the time-dependent LEI-GP model demonstrates higher prediction accuracy in learning effectiveness, as it incorporates updates based on performance data from the previous class hour.

Figure 4. The input data and prediction outcomes of the time-dependently LEI-GP model during class hour 2. (a–e) The input data used to predict student learning effectiveness during class hour 2, comprising eight educational inputs and four sensing inputs. (f) Comparison of the predicted student learning effectiveness for the class hour 2 generated by the LEI-GP and GP models, as well as the actual student scores obtained during the class hour 2.

Roadmap and future trends for PI-AI

Physics-informed AI has been applied in a variety of research directions in engineering and materials science (Karniadakis et al., 2021; Raabe et al., 2023); however, PI-AI in higher engineering education has just debuted and an obvious gap exists between the algorithms and education theories. This leads to the development direction of combining PI-AI with these theories. For example, the LEI-GP model in Equations 3, 4 expands the GP prediction model in Equation 2 by considering the in-class behavior of every student in each class. The output learning effectiveness is a time-dependently individual value, which need to be analyzed based on educational theories in the field of engineering (Ouyang and Jiao, 2021). Therefore, addressing the higher engineering education issues by PI-AI not only requires the development of sensing devices to collect teaching and learning data and AI algorithms to identify the quantitative relationships behind those data, but also the integration of the technologies with educational principles and theories (Chen et al., 2020b). It is essential to examine the suitability of AI algorithms in higher engineering education, while, more importantly, adjusting AI based on the existing educational and learning theories. As a consequence, AI needs to be tightly connected with those theories to achieve customized instructional design and technological development with higher accuracy (Pinkwart, 2016). Comparing with the massive applications of the existing AI algorithms in higher engineering education; however, inadequate studies have been conducted to explore the personalized functionality, improve the accuracy and efficiency, and expand the applicability.

The role of students in learning is another perspective that need to be considered in the PI-AI strategy. Previous study indicated that the development trends of AI in high engineering education has been shifted from Paradigm 1 AI-directed, learner-as-recipient to Paradigm 2 AI-supported, learner-as-collaborator, which leads to Paradigm 3 AI-empowered, learner-as-leader that deeply integrates human and AI2. Multidimensional attributors, multimodal data collection and real-time modeling are essential to facilitate PI-AI toward paradigm three. In particular, multidimensional attributors enrich the prediction and evaluation accuracy of learning effectiveness. Multimodal data collection enables the richness and complexity of human learning to be better interpreted, evidenced and supported. It is worthwhile to note that applying advanced sensing techniques and AI algorithms can improve the prediction accuracy of students' learning effectiveness; however, it does not necessarily guarantee the improvement of learning effectiveness in higher engineering education. Instead, educational theories are needed to conduct the role shifting of students from Paradigm 1 to Paradigm 3. If the traditional paradigm of education remains, students will not be empowered to take agency for their own learning, e.g., students are not informed with how their data are used and for what purpose or their needs and learning goals are not considered.

Engineering characteristics of the course need to be considered in the PI-AI model. For example, the difference between courses may lead to certain difference in the GP model. To this end, it is necessary to improve PI-AI algorithms and, more importantly, bring the characteristics of various courses into PI-AI. It is crucial to emphasize the integration of the pedagogical, social, cultural and economic dimensions in the application processes of PI-AI, rather than a simple implementation of AI technology. Expanding the existing educational theories, researchers can derive new interpretations or ideas can be derived on the pedagogy and learning sciences of PI-AI in higher engineering education. Comparing with its AI peers, PI-AI has potential to further stimulate and advance instructional and learning sciences, which, in turn, would offer performance-informed opportunities to improve learning effectiveness. The future development of PI-AI must lead to the iterative development of the learner-centered, data-driven, personalized learning in the current knowledge age. Overall, the next-generation PI-AI will be benefited from the deep integration of human and machine intelligence, i.e., taking advantage of technological advances of AI while fully integrating human cognition, thinking and reflective judgments.

In recent years, the rise of large language models (LLMs), including ChatGPT, has led to their increasing application in education. LLMs are transforming traditional teaching and assessment models by providing instant feedback and generating teaching materials (Khodadad, 2025). In this context, Performance-Informed AI (PI-AI), as an emerging educational technology, can predict learning outcomes through the real-time collection and analysis of students' physiological data. The impact of LLMs on teaching is profound. They not only function as virtual tutors providing instant Q&A support, but also help students better understand complex academic concepts. Furthermore, LLMs enhance student motivation and engagement, particularly in remote learning and online education environments. However, despite their numerous advantages, there are some inherent risks (Nikolic et al., 2023). For example, LLMs may generate false or inaccurate information, potentially leading students to rely on incorrect data unknowingly. Additionally, the use of LLMs could raise academic integrity concerns, such as students using LLMs to complete assignments or exams. To address these issues, we recommend strengthening the management of LLM usage, establishing appropriate policies, and implementing monitoring mechanisms. Regarding the integration of PI-AI and LLMs, PI-AI systems can dynamically sense students' physiological data (e.g., heart rate, eye movement, body temperature) and adjust learning content and teaching strategies accordingly, thereby enabling highly personalized learning experiences (Seibert et al., 2025). In contrast, LLMs provide students with instant feedback, tutoring, and problem-solving assistance. The synergy between PI-AI and LLMs holds the potential to significantly enhance teaching effectiveness and learning outcomes. By combining PI-AI with LLMs, education can provide more personalized and dynamic support, further advancing the development of engineering education.

Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed performance-informed artificial intelligence (PI-AI) for class design and learning effectiveness prediction in higher engineering education. We discussed the debut and recent development of AIEd, summarizing the current achievements of AI in higher engineering education, and highlighting the PI-AI strategy to maximize teaching and learning performance. To showcase the application of PI-AI, we developed the learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP) model to predict the learning effectiveness Lnreff of Smart Marine Metastructures—a graduate-level course offered by the author in a Chinese top university. The time-dependent LEI-GP model was updated by the physiological data of students in learning in a real-time wireless manner, while taking into account of the individual uniqueness of those students. Eventually, we provided insights into the PI-AI strategy in propelling real-life customized higher engineering education. The reported PI-AI is an emerging scientific direction in AIEd, which is expected to balance the dilemma between the generalized and customized learning in STEM education and address the concern on the design and optimization of its instructional design and teaching strategy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Zhejiang University Ethics Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. HZ: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. CM: Writing – review & editing. HK: Writing – review & editing. RZ: Writing – review & editing. PJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported in part by China Association of Higher Education 2023 Higher Education Scientific Research Planning Project (23LH0426) and Zhejiang University 2025 Int'l Student Education Research Project (2025-GJXSJYYJ-A-002).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1664069/full#supplementary-material

References

Albreiki, B., Zaki, N., and Alashwal, H. (2021). A systematic literature review of student performance prediction using machine learning techniques. Educ. Sci. 11:552. doi: 10.3390/educsci11090552

Alenezi, H. S., and Faisal, M. H. (2020). Utilizing crowdsourcing and machine learning in education: literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 2971–2986. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10102-w

Antoniou, P. E., Arfaras, G., Pandria, N., Athanasiou, A., Ntakakis, G., Babatsikos, E., and Bamidis, P. (2020). Biosensor real-time affective analytics in virtual and mixed reality medical education serious games: Cohort study. JMIR Ser. Games 8:e17823. doi: 10.2196/17823

Bajaj, R., and Sharma, V. (2018). Smart education with artificial intelligence-based determination of learning styles. Procedia Comput. Sci. 132, 834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.05.095

Baker, M. J. (2000). The roles of models in artificial intelligence and education research: a prospective view. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 11, 122–143. Available online at: https://telearn.hal.science/hal-00190395/document (Accessed December 8, 2025).

Chen, S., Ouyang, F., and Jiao, P. (2022). Promoting student engagement in online collaborative writing through a student-facing social learning analytics tool. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 38, 192–208. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12604

Chen, X., Xie, H., and Hwang, G.-J. (2020a). A multi-perspective study on artificial intelligence in education: grants, conferences, journals, software tools, institutions, and researchers. Comput. Educ. 1:100005. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100005

Chen, X., Xie, H., Zou, D., and Hwang, G.-J. (2020b). Application and theory gaps during the rise of artificial intelligence in education. Comput. Educ. 1:100002. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100002

Deeva, G., Bogdanova, D., Serral, E., Snoeck, M., and De Weerdt, J. (2021). A review of automated feedback systems for learners: classification framework, challenges and opportunities. Comput. Educ. 162:104094. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104094

Giannakos, M. N., Sharma, K., Pappas, I. O., Kostakos, V., and Velloso, E. (2019). Multimodal data as a means to understand the learning experience. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 48, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.02.003

Hinojo-Lucena, F. J., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., and Romero-Rodríguez, J. M. (2019). Artificial intelligence in higher education: a bibliometric study on its impact in the scientific literature. Educ. Sci. 9::51. doi: 10.3390/educsci9010051

Hwang, G.-J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., and Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of artificial intelligence in education. Comput. Educ. 1:100001. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Jiao, P., Ouyang, F., Zhang, Q., and Alavi, A. H. (2022). Artificial intelligence-enabled prediction model of student academic performance in online engineering education. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 6321–6344. doi: 10.1007/s10462-022-10155-y

Johnson, M., Albizri, A., Harfouche, A., and Fosso-Wamba, S. (2022). Integrating human knowledge into artificial intelligence for complex and ill-structured problems: informed artificial intelligence. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 64:102479. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102479

Kabra, R. R., and Bichkar, R. S. (2011). Performance prediction of engineering students using decision trees. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 36, 8–12. doi: 10.5120/4532-6414

Karniadakis, G. E., Kevrekidis, I. G., Lu, L., Perdikaris, P., Wang, S., and Yang, L. (2021). Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440. doi: 10.1038/s42254-021-00314-5

Khan, A., and Ghosh, S. K. (2021). Student performance analysis and prediction in classroom learning: a review of educational data mining studies. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 205–240. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10230-3

Khodadad, D. (2025). ChatGPT in engineering education: a breakthrough or a challenge? Phys. Educ. 60:045006. doi: 10.1088/1361-6552/add073

Litman, D. (2016). “Natural language processing for enhancing teaching and learning,” in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference On Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 30). doi: 10.1609/aaai.v30i1.9879

Luckin, R., and Holmes, W. (2016). Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education. London: Pearson.

McNeal, K. S., Zhong, M., Soltis, N. A., Doukopoulos, L., Johnson, E. T., Courtney, S., et al. (2020). Biosensors show promise as a measure of student engagement in a large introductory biology course. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 19:ar50. doi: 10.1187/cbe.19-08-0158

Mountrakis, G., and Triantakonstantis, D. (2012). Inquiry-based learning in remote sensing: a space balloon educational experiment. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 36, 385–401. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2011.638707

Nikolic, S., Daniel, S., Haque, R., Belkina, M,., Ghulam, M. H., Grundy, S., et al. (2023). ChatGPT versus engineering education assessment: a multidisciplinary and multi-institutional benchmarking and analysis of this generative artificial intelligence tool to investigate assessment integrity. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 48, 559–614. doi: 10.1080/03043797.2023.2213169

Okewu, E., Adewole, P., Misra, S., Maskeliunas, R., and Damasevicius, R. (2021). Artificial neural networks for educational data mining in higher education: a systematic literature review. Appl. Artif. Intell. 35, 983–1021. doi: 10.1080/08839514.2021.1922847

Ouyang, F. (2023). Fostering the instructor–student collaborative partnership in China's higher education: a three-iterative action research. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 62, 58–72. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2023.2276236

Ouyang, F., and Jiao, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education: the three paradigms. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2:100020. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100020

Ouyang, F., Jiao, P., McLaren, B. M., and Alavi, A. H. (2022a). Artificial Intelligence in STEM Education: The Paradigmatic Shifts in Research, Education and Technology. Abingdon: CRC Press.

Ouyang, F., Li, X., Sun, D., Jiao, P., and Yao, J. (2020). Learners' discussion patterns, perceptions, and preferences in a Chinese massive open online course (MOOC). Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 21, 264–100284. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4771

Ouyang, F., Wu, M., Zheng, L., Zhang, L., and Jiao, P. (2023). Integration of artificial intelligence performance prediction and learning analytics to improve student learning in online engineering course. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 20:4. doi: 10.1186/s41239-022-00372-4

Ouyang, F., Zheng, L., and Jiao, P. (2022b). Artificial intelligence in online higher education: a systematic review of empirical research from 2011 to 2020. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 7893–7925. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-10925-9

Perrotta, C., and Selwyn, N. (2019). Deep learning goes to school: toward a relational understanding of AI in education. Learn. Media Technol. 45, 251–269. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/48t7e

Pinkwart, N. (2016). Another 25 years of AIED? Challenges and opportunities for intelligent educational technologies of the future. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 26, 771–783. doi: 10.1007/s40593-016-0099-7

Popenici, S. A. D., and Kerr, S. (2017). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 12:22. doi: 10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8

Raabe, D., Mianroodi, J. R., and Neugebauer, J. (2023). Accelerating the design of compositionally complex materials via physics-informed artificial intelligence. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 198–209. doi: 10.1038/s43588-023-00412-7

Raabe, D., Tasan, C. C., and Olivetti, E. A. (2019). Strategies for improving the sustainability of structural metals. Nature 575, 64–74. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1702-5

Riedl, M. O. (2019). Human-centered artificial intelligence and machine learning. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Tech. 1, 33–36. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.117

Segal, M. (2019). A more human approach to artificial intelligence. Nature 571:S18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02213-3

Seibert, V., Geger, T., and Rausch, A. (2025). “Leveraging Chat-GPT to generate educational assessment materials for software engineering,” in World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering and Applied Computing. Berlin: Springer, pp. 137–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-85930-4_13

Sekeroglu, B., Dimililer, K., and Tuncal, K. (2019). “Student performance prediction and classification using machine learning algorithms,” in Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Educational and Information Technology (pp. 7–11). doi: 10.1145/3318396.3318419

Starčič, A. I. (2019). Human learning and learning analytics in the age of artificial intelligence. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 2974–2976. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12879

Tang, K. Y., Chang, C. Y., and Hwang, G. J. (2021). Trends in artificial intelligence-supported e-learning: a systematic review and co-citation network analysis (1998–2019). Interact. Learn. Environ. 31:2134. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2021.1875001

Wang, S., Wang, F., Zhu, Z., Wang, J., Tran, T., and Du, Z. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: a systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 252:124167. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124167

Yang, S. J., Ogata, H., Matsui, T., and Chen, N. S. (2021). Human-centered artificial intelligence in education: seeing the invisible through the visible. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2:100008. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100008

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., and Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 16:39. doi: 10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Zhang, Y. (2021). An AI-based design of student performance prediction and evaluation system in college physical education. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 40, 3271–3279. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-189367

Keywords: customized higher education, performance-informed artificial intelligence (PI-AI), learning effectiveness-informed genetic programming (LEI-GP), teaching and learning performance, AI in education (AIEd)

Citation: Lv Y, Zhang H, Ma C, Kang H, Zhu R and Jiao P (2025) Performance-informed learning effectiveness prediction for customized higher education: an engineering perspective. Front. Educ. 10:1664069. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1664069

Received: 11 August 2025; Revised: 23 November 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025;

Published: 15 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sergio Ruiz-Viruel, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Davood Khodadad, Umeå University, SwedenYang Yang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

Copyright © 2025 Lv, Zhang, Ma, Kang, Zhu and Jiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pengcheng Jiao, cGppYW9Aemp1LmVkdS5jbg==; Ronghua Zhu, emh1LnJpY2hhcmRAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yanxing Lv1†

Yanxing Lv1† Hao Zhang

Hao Zhang Pengcheng Jiao

Pengcheng Jiao