- Kathmandu University School of Education, Patan, Nepal

This article shows how the paradigm of dialectical pluralism can be applied for a deeper understanding of a research issue by abstracting insights from post-positivist and constructivist paradigms and bringing their interaction for additional meaning-making. As an example, a mixed methods study on ethical leadership is presented. On the study, the qualitative and quantitative strands had similar findings that ethical leadership was rooted in schools in the form of care, justice, and critique. However, contradictions were observed to their extent, which were answered by dialoguing between the strands, and the process of dialogue generated additional meaning. This article contributes to the mixed methods research in education by presenting evidence that dialectical pluralism provides additional meaning in the process of integrating the strands.

Introduction

There are numerous advantages of using the paradigm of dialectical pluralism, as it uses the strengths of both the post-positivist and constructivist paradigms. Importantly, it can interplay with the strengths gained in the process of integration. This article provides some major advantages of the paradigm of dialectical pluralism. In illustrating the advantages, an example of exploring ethical leadership by using the paradigm is presented. Before I present the example, I explain the paradigms in mixed research and their discourse in general and dialectical pluralism in particular.

Paradigms in mixed methods research

Paradigms are often discussed as a worldview that includes or provides a frame of reference to look at something (Barker, 2003; Bennett, 2023). Guba and Lincoln (1994) and Bennett (2023) believe that the paradigm provides a set of beliefs that guide the actions of the researchers. For the authors, there are three major philosophical paradigms: positivism, critical theory, and interpretivism. These paradigms were primarily brought forward to connect them to the quantitative and qualitative research methods in the earlier days. Paradigm, these days, has become one of the most talked about terms in Mixed Methods Research (MMR). Several authors are engaged in the discourse and advocate various paradigmatic positions in Mixed Methods Research. The most important paradigmatic positions that are brought into the discourse of MMR incorporate pragmatism, dialectism or dialectical pluralism, transformative, critical realism, and performative. Among them, pragmatism has been advocated (e.g., Allemang et al., 2022; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011; Morgan, 2014; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009; Yardley and Bishop, 2008) for its importance to move into the subject of research by setting aside the issues of ontology and epistemology (Bryman, 2007). Its strengths are often advocated in many ways. For example, Morgan (2007) says that it draws methodologists’ attention. For Feilzer (2010), it has application in both inductive and deductive reasoning. Harrits (2011) believes that it allows many research paradigms to be compared. Another paradigm, dialectical pluralism, that this article advocates, has been explained in the next section of this article. The other paradigm, called transformative or emancipatory, was introduced by Mertens (2007). While adding her one into discourse, she argues that there are three paradigms: dialectical pluralism, pragmatism, and the transformative. The philosophical assumptions of the transformative paradigm provide an ethical lens to examine societal injustice (Mertens, 2012). Creamer (2018) acknowledges its reflection and highlights its role in research for social change. Unlike the transformative paradigm, critical realism has a positioning that there is an objective world (Maxwell, 2012; Maxwell and Mittapalli, 2010). Maxwell (2012) believes that it has an ontological position that the truth exists independently of our perceptions, theories, and constructions.

Schoonenboom (2019) proposes the performative paradigm with a focus on research actions remaining on the ontological position of relativism. She claims that with her one, there are four paradigms, including the dialectic stance, critical realism, pragmatism, and performative. Besides, some other scholars have proposed other ways of presenting a paradigm. For example, Fetters and Molina-Azorin (2019) introduced Asian perspectives of mixed research with the yin-yang philosophy.

Dialectical pluralism for additional insights

All the paradigms are equally useful in their own context and space. Therefore, I do agree with the view of Shannon-Baker (2016) who advocates that mixed research should be concerned with the legitimation and operationalization of the paradigm chosen in their research rather than finding out the single best paradigm. At the same time, I also advocate that dialectical pluralism is useful for optimum use of both the post-positivist and constructivist paradigms, and to get additional insights into the process of comparison of the two paradigms. In dialectical pluralism, the post-positivist knowledge building helps to discover or examine truths by testing theories and performing empirical validation with a larger representation. Constructivist knowledge claim with the paradigm does not go with wider generalizability but goes into the depth of the issue/concern to understand the research problem. After the researchers engage in distinct paradigms, they combine the findings in the process of integration (Bazeley, 2012; Fetters et al., 2013). In integration, I echo with Schoonenboom (2019) as she suggests that integration is a tricky problem in the dialectic-stance paradigm. However, I disagree with her in the sense that in the process of integration, researchers with a dialectical stance get an opportunity to examine why and how there are diverse findings. Finding the answer to such concerns brings the researchers to the next level of a knowledge claim. Even though there are similar findings obtained from each methodological strand, it helps to triangulate our knowledge claims, and thus, the process yields credible study.

This shows that by positioning in the paradigm of “dialectical pluralism” (Greene, 2015; Johnson, 2017), one can choose the type of knowledge that is grounded in one sense, and that is perceived differently by different people according to their experience, context, and event in the other sense. Both the generalized form of knowledge claims and subjective experiences of the people are equally important to exploring the realities. Besides, Johnson (2008) argues that the dialectic approach allows interaction between the contrasting paradigms in this “meta-paradigm” (Johnson, 2017). Greene (2007, 2015) also thinks that dialecticalism brings the dialogue between the constructivist that assumes multiple realities and the post-positivist view that assumes a single reality and combines them together for additional meaning-making. In this context, I present my research on ethical leadership undertaken standing on dialectical pluralism. The purpose is to demonstrate that the paradigm of dialectical pluralism can be useful to get the optimum benefits of both post-positivism and constructivism in their individual application and to draw the next level of knowledge claim in the process of their integration.

In presenting the study, a brief introduction and review of the literature on dimensions of ethical leadership are provided first. Next, the convergent mixed research design of this study is explained. The subsequent section provides an overview of data collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative phases. Then the results of both the strands are displayed, and the contradictions are explained. The final section consists of the discussion of limitations, implications, and conclusions of the study.

Study on ethical leadership

The issue of ethics and anticorruption concerned me even during my graduate studies. This continuous curiosity about the issues inspired me to explore them further. Consequently, I carried out research in the same area during my higher studies. I have been exploring and working in the area since then. Through this engagement, I have realized that maintaining ethical values in decision-making is a complex process (Muktan and Bhattarai, 2023; Neupane et al., 2022; Schwartz, 2016) that requires ongoing critical reflection and continuous examination of the literature.

Ethical leadership in a school setting remains within three ethical paradigms: care, justice, and critique (e.g., Begley, 2006; Langlois, 2011; Starratt, 2012; Vogel, 2012). These wider paradigms are complementary. However, for the effective function of these three ethical leadership paradigms, Langlois (2011) believes that there is a need for ethical sensitivity in the principals by which they can examine the ethical situation of their schools and reflect on their practices. Action research by Langlois and LaPointe (2010) shows that activation of ethical sensitivity promotes ethical leadership in an individual.

Langlois and LaPointe (2010) developed a “typology of ethical competency” to examine the level of ethical leadership. The typology consists of five ethical competencies: traces, emergence, presence, consolidation, and optimization. Out of them, “traces” represents the lowest competency in which principals simply tend their attitude toward ethical leadership. At the next level of “emergence,” principals’ ethical leadership becomes visible and then develops further to demonstrate ethical sensitivity in the “presence” stage. The ethical leadership is actualized and reflected in behavior and practices in the “consolidation” stage, and it is demonstrated to its maximum extent at the “optimization” stage.

Several reasons have been proposed to elucidate why ethical leadership with a specific focus on care, justice, and critique is a central concern of schools (Kayastha, 2024). The members of a school essentially need to possess a sense of ethical leadership and bring their ethical expertise into practice to ensure continuous growth and development of the school (Campbell, 2004; Starratt, 2004). Ethical expertise is particularly required when controversies and confusion arise in the ethical handling practices of schools. When there are such repeated controversies and confusions in the handling practices of schools, principals are often criticized for unethical practices. And thus, they often feel the challenge to deal with these controversies and confusions. Consequently, the ethical environment of these schools is in question. Therefore, to build ethical environments at schools, these complexities need to be explored, analyzed, and resolved. This concern of the study is also imperative in the schools of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) sector in Nepal (Bhattarai, 2019; Bhattarai, 2021). Langlois et al. (2014) also indicates that such studies are very necessary for the cultural context of different countries.

This demands exploration of ethical leadership among the principals. However, the complexity of ethical leadership is hard to examine by a single paradigm. Therefore, a mixed research study was proposed to examine complexity within a strand, but without interaction between strands till interpretation. The objective of merging strands at interpretation was to get the benefits of both the strands of post-positivist and constructivist paradigms, as well as from the insights gained in the process of integration.

The research questions of the study included: How was ethical leadership perceived by the principals of TVET schools? And what was its level?

Literature on ethical leadership

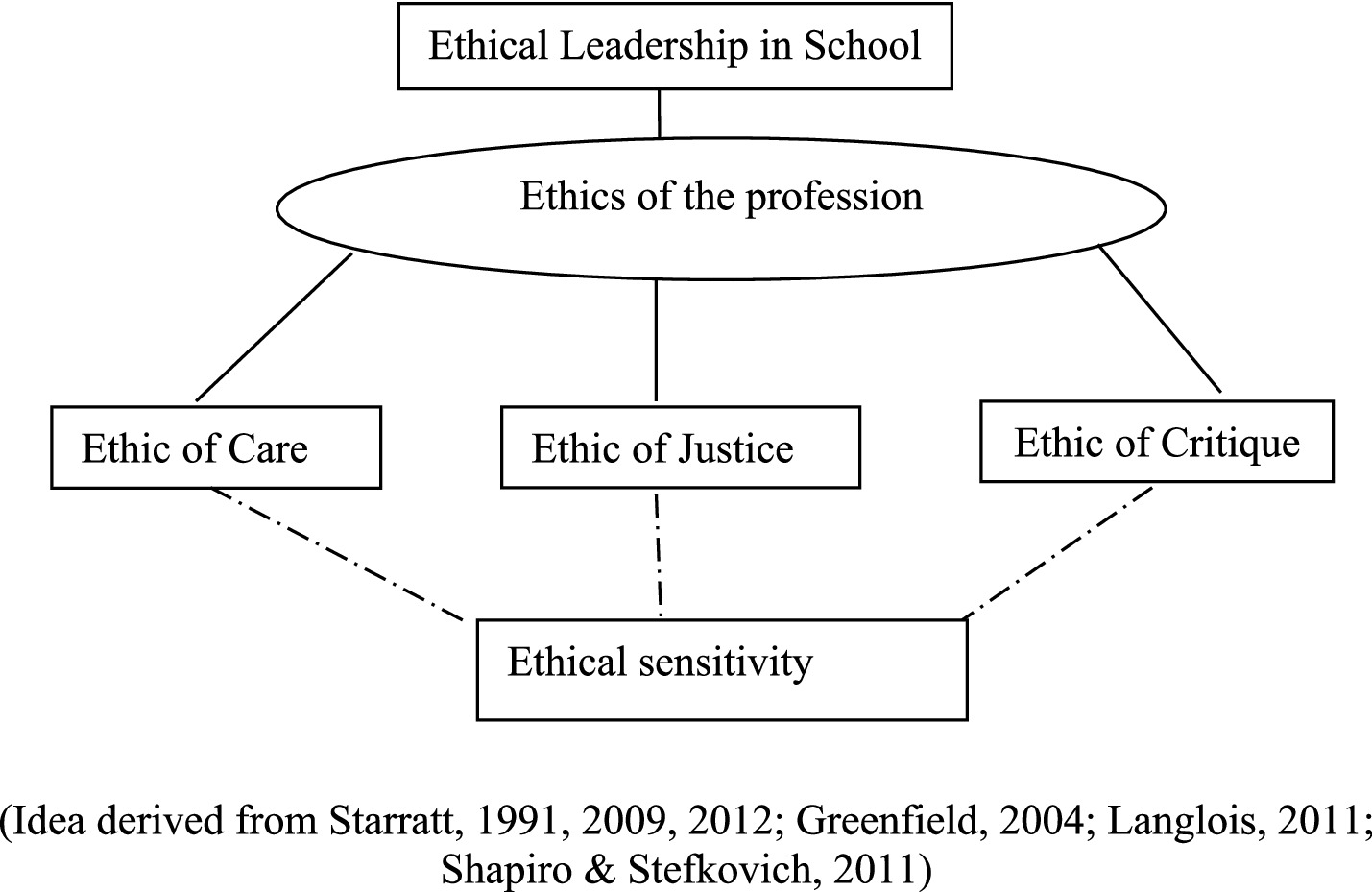

Ethical leadership has been examined in several studies and theories. Out of all, Starratt’s (1991) articulation of ethical leadership and its indicators were widely cited in the community of educational leadership. He believes that ethical leadership consists of paradigms such as care, justice, and critique. The three paradigms are useful to examine the everyday functions of the head of an educational institution and help in the process of making ethical decisions in schools.

Among the three paradigms, the ethics of care has been derived from the theory of relational ethics. For Gilligan (1982), the ethic of care includes concepts of being there, listening, understanding, sharing responsibility for another’s welfare, strengthening and maintaining relationships, attachment, and abandonment of relationships. She wrote about the differences by which men and women approach moral issues. She clarified that women acknowledge the human relationship and show care to them, those they feel responsible for, but men bring rules into their thinking and behavior.

Ethics of justice mostly focuses on the rightness and wrongness connected to the intentions of the doers, and it provides a basis for the legal aspects of being a principal. Within justice, individuals get opportunities to raise questions about fairness, equity, and justice. The concern of ethics of justice revolves around rightness and wrongness and their legal aspect. Shapiro and Stefkovich (2005) believe that the ethics of justice examine the situation to know whether related laws, rights, or policies are in place. If there are associated policies, the concern can be to see whether they are (or can be) implemented. The rules, however, are defined by the individuals. Therefore, there is a need for a critical examination of the regulations and their implementation practice.

The ethics of critique is firmly rooted in critical theory. Within it, questions are posed to the rooted status quo. The deprived and minority sections of the population are given a voice. In giving voice, the roles of acts and principles are taken into consideration (Robinson and Garratt, 2004, p. 128). Here, one might raise questions with lawmakers and others related to laws and the judiciary. Langlois (2011) raised four concerns underlying the relations of power: (i) the beneficiaries of the situation, (ii) the dominant group, (iii) individuals who define the structure, and (iv) what is valued or undervalued.

Shapiro and Stefkovich (2005) presented a fourth ethical framework, the “paradigm of professional ethics.” Explaining its importance, they said that the paradigm of professional ethics raises queries related to professional and communal expectations from a school leader (Shapiro and Stefkovich, 2021). Thus, this paradigm provides a basis for professionalism for school leaders (Ahmad et al., 2023).

Ethical sensitivity is considered one of the essential dimensions of ethical leadership by which the principals show their competence in how and to what extent their behavior and conduct affect their fellows and the other school stakeholders. Such ethical awareness requires knowledge of ethics (Andersson et al., 2022). Langlois et al. (2014) also suggest that knowledge is key to a person’s ethical sensitivity. For Tuana (2007), ethical sensitivity can help examine the moral values in every situation when ethics becomes a concern. This idea has also been established through action research, which suggested that promoting ethical sensitivity in the workplace builds ethical leadership (Langlois and LaPointe, 2010). This may explain why ethical awareness is also emphasized in non-educational studies, such as Ghorbani et al. (2023). In this sense, the Nepali TVET sector leadership at schools requires examining ethical sensitivity, care, justice, and critique for its effective operation. The theoretical framework has been presented in Figure 1.

Although research has examined ethical leadership, most studies have utilized a single method. However, the complexity of ethical leadership is difficult to capture through a single paradigm. In addition, only a limited number of studies have explored ethical leadership among TVET principals.

Application of convergent mixed research

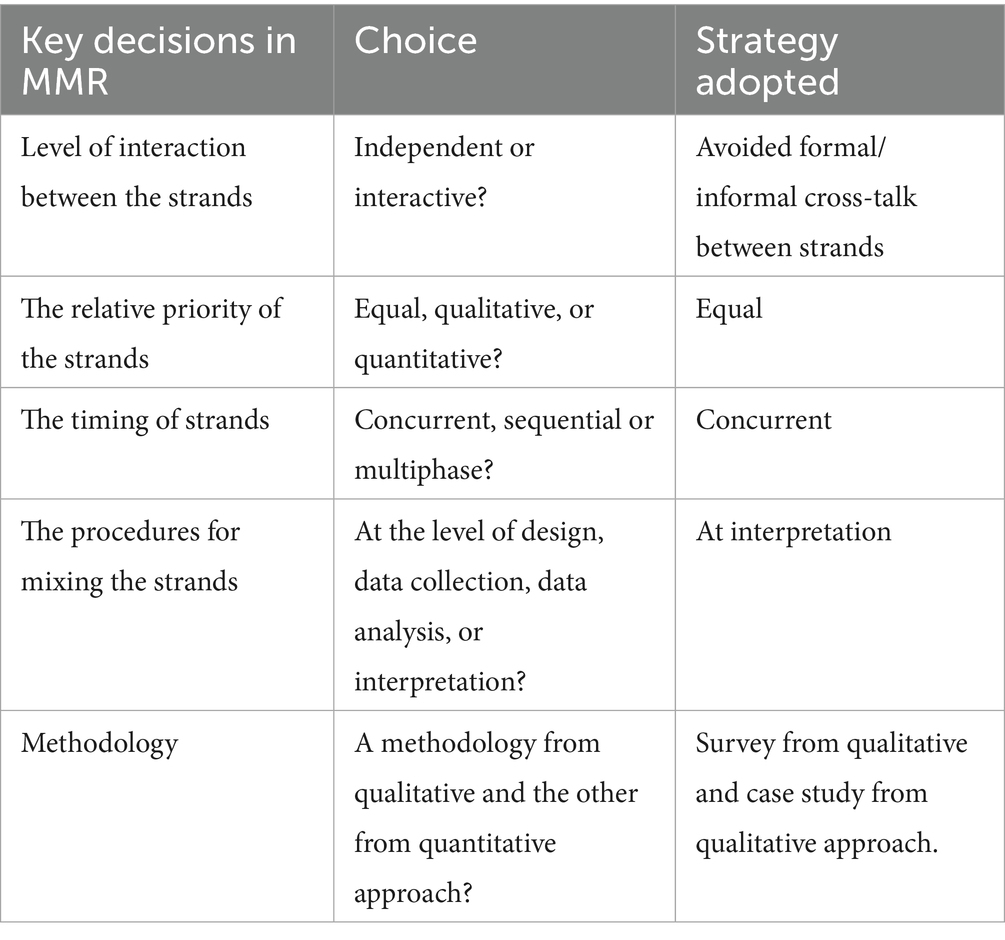

Mixed research was used in this study since the combination of post-positivism and constructivism complements each other and allows for additional meaning-making (Green et al., 1989; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998). In the mixed research, “four key decisions (level of interaction between the strands, the relative priority of the strands, the timing of strands, and the procedures for mixing the strands) in choosing an appropriate mixed research design are used” (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011, p. 64).

Out of these four decisions (Table 1), the level of interaction between the strands was the first. In this study, I mixed the two strands after I had drawn the findings from those strands. I was aware that there could be possible interaction or “cross-talk” (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009, p. 266) in the process of data collection and analysis. Therefore, I went to the field to generate my qualitative data as soon as I sent my questionnaire to the field. In the process of data analysis too, I analyzed my qualitative data and drew meanings out of them before I started to work on the quantitative data. If I had analyzed the quantitative data first, the outcome would have influenced my qualitative findings. Here, I avoided “informal cross-talk between strands” (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009), which could occur during analysis. This avoiding interaction is necessary to optimize the strengths of both methods since the results of both strands become visible after certain stages. If there was cross-talk, the findings of the survey could influence my case study findings, and thus, the rigor of the case study could be in question.

The second decision, as discussed above, was the relative priority of the strand. In the context of this study, both quantitative and qualitative approaches were employed to explore ethical leadership and its extent with equal priority. The third decision in this connection is the timing of the qualitative and quantitative strands. In this study, I used concurrent timing since one approach could be influenced by the other in a sequential or multiphase design. In fact, I wanted to be independent in each method to the end of this study. I sent the questionnaire to all TVET schools in the country through a courier service and visited three districts to generate qualitative data. Therefore, when I was in the field of qualitative data, I did not pay any attention to quantitative data. This also helped me to focus on qualitative data collection.

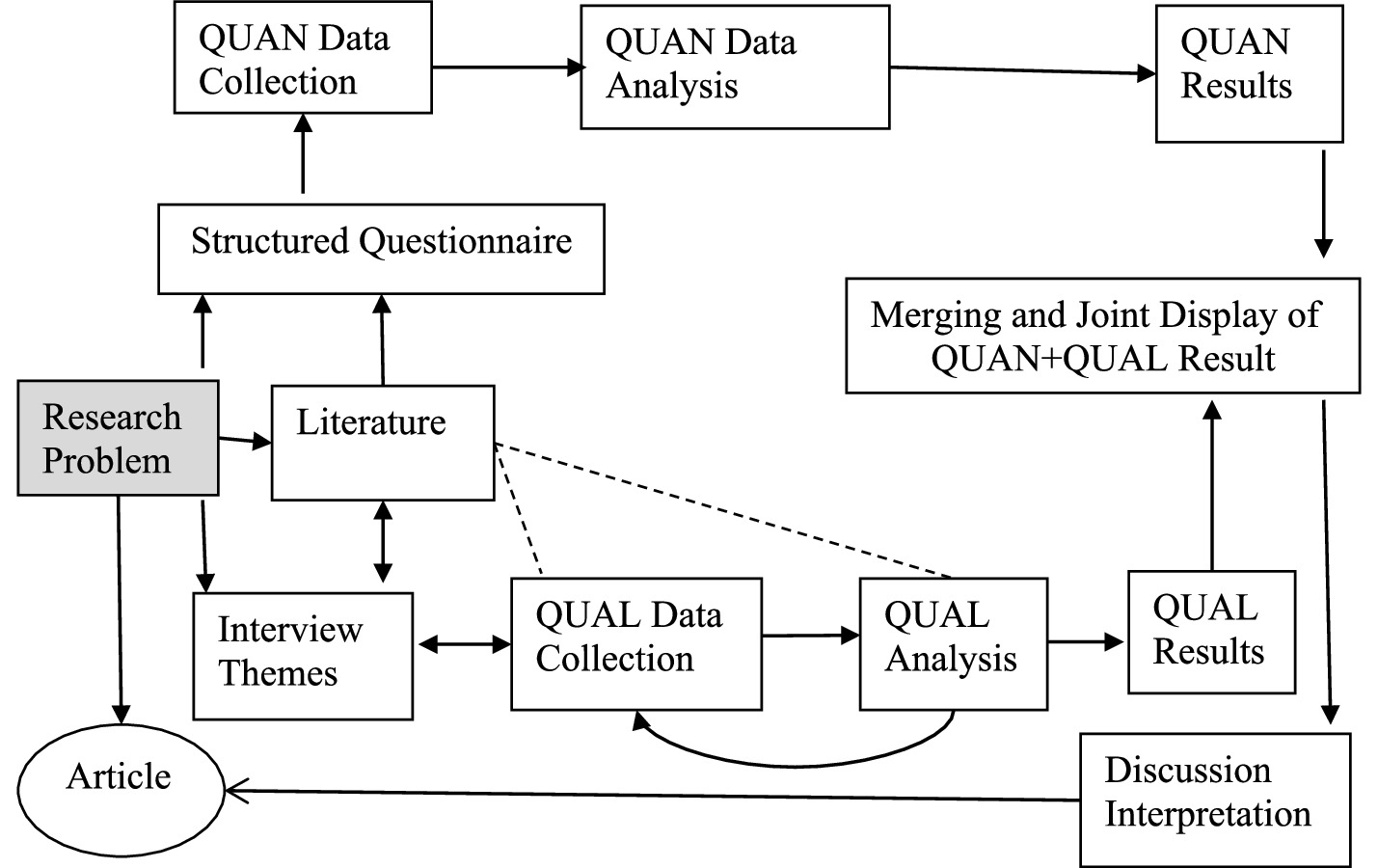

The fourth decision is about the procedure for mixing the strands. Four possible mixing strategies are proposed in this aspect at the level of design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation. In this study, I analyzed the qualitative data first and drew the findings. The findings were then merged during interpretation. Therefore, the strands were entirely separate until I merged the findings to interpret the result (Figure 2).

After being clear about the four key decisions, I realized that I had missed considering the “methodology” (Harrison et al., 2017; Mills, 2014) of case study and survey research within the key decisions that were much necessary to guide my qualitative and quantitative strands. The decision of research methodology, particularly in convergent mixed research, which requires merging of both qualitative and quantitative strands at the time of interpretation, was also necessary since it connects both research strategies to their paradigms (Dooley, 2007; Johnson et al., 2007).

Phase I: survey

Target population and sampling in the QUAN strand

Council of Technical Education and Vocation Training (CTEVT) is the apex body providing TVET education in Nepal. The performance of the TVET sector in general, and TVET schools in particular, can be questioned because there is a gap between employers’ assessments of employees’ skills and employees’ own perceptions of their abilities (Bhattarai et al., 2025). The performance of TVET graduates in Nepal is not satisfactory, given the investment made by the government (Bhurtel, 2016). Several other concerns in TVET are hindering the growth of the TVET sector in Nepal (Renold and Caves, 2017). Thus, a leadership role with ethical sensitivity is necessary in TVET to improve the results. All 377 school principals listed in Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training (CTEVT), (2012) were the population chosen for the study. Out of them, 10 schools were used to pilot the tools, which were not used for the final survey. The remaining 367 school principals were the actual population for the study. To explore ethical leadership, I realized that the view of the instructors was also necessary, and the two questionnaires for the instructors, along with the self-stamped mailing envelopes for each respondent, were included in the package of the big envelope prepared for each school. Then, the questionnaires were sent to each school by postal service to receive responses after the stipulated three-month duration. Ultimately, 217 principals (59.1%) and 372 instructors (50.7%) sent back the questionnaire themselves through post offices in envelopes that were provided to them. The number was more than 50% of the population for both principals and instructors. As highlighted by Ahmed (2024), expanding the sample size reduces the margin of error, which improves the accuracy of the estimated results.

Tools and techniques of data collection

As explained earlier, this study consisted of two major methodologies: survey and case study. Therefore, the study consisted of two different ways of data collection tools and techniques. In the study, the quantitative data were also gathered via the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS) developed by Langlois. She and her colleagues, Houme and LaPointe, presented a paper titled, From Qualitative Data to a Gender-Friendly Quantitative Instrument: The Making of the Ethical Leadership Questionnaire at the AERA conference in Denver, Colorado, in October 2010. I also needed a questionnaire to explore what instructors perceived about their school principals. Therefore, I converted Langlois’s ELS in such a way that it would measure the perceptions of the instructors about the ethical leadership of their principals. Then, the questionnaires were translated into the Nepali language, and a language expert was asked to check them. Nepali questionnaires were again translated back into English to verify that the sense had been intact in the translation. I also checked the reliability of the questionnaire. Then, for the final study, the questionnaire was sent to 367 TVET principals and 734 instructors in Nepal by using the postal service to receive them back within 3 months. Those respondents from pilot testing were not included in the final study.

Data analysis and interpretation

The study consisted of data from the survey and the case study. Obviously, the data collected through these two methods were numeric and textual, respectively. Therefore, the analysis with each method was different. In the following section, I have first discussed how the data analysis of the survey was performed. This section has been followed by a description of the data analysis technique used for case study.

In the survey method, the data were first entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.2. Descriptive statistics were computed, and the analysis consisted of frequency and percentage calculations. Descriptive statistics consisting of means and standard deviation were also applied to measure care, justice, and critique. An independent t-test was employed to show a significant difference in the views of principals and instructors about ethical leadership.

Reliability and validity

Calculation of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was the test used in the QUAN phase. This was seen to be appropriate because it required only a single test administration and provided a unique quantitative estimate of reliability for the given administration. For this, the questionnaires were pre-tested with 10 principals of three districts. In the real study, these respondents were not included since they could be aware of what they wrote. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated. The reliability of each section was tested separately since each section measured a separate and single one-dimensional construct. The coefficients of care, justice, critique, and ethical sensitivity were obtained as 0.764, 0.82, 0.82, and 0.71, respectively.

Content validity was considered using the tool constructed by well-known Professor Lyse Langlois from Laval University, who has long working experience in ethical leadership, in the primary concept of Professor Robert Starratt (the most cited scholar in ethical leadership literature) from Boston College, the content of ethical leadership is widely covered. Besides, the questionnaire was contextualized in the Nepali context. The result of this study was compared with similar studies of other countries, irrespective of culture and group. Also, my comparison of the results from the qualitative and quantitative studies was a way of maintaining criterion-related validity. In this process, inconsistencies in the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies were examined.

Phase II: case study

Case selection in QUAL strand

I had two distinct philosophical foundations of case study literature. More specifically, I recognized that out of the three distinct scholars (Yin, Stake, & Merriam) mostly cited in case study literature, Stake (1995) and Merriam (1998) prefer to use a flexible design. In contrast, there is not much flexibility in research design in the approach of Yin (2014). Therefore, some critics have suggested that Yin’s research has been situated within a post-positivist paradigm, whereas Merriam’s and Stake’s have been non-positivist (Boblin et al., 2013; Brown, 2008). I preferred to use the design of Merriam (1998) and Stake (2005) since, as explained above, I used a survey design in this study for a post-positivist knowledge claim. If I had used Yin’s case study, it would have been another post-positivist way of claiming knowledge. In fact, I did not intend to use two methodologies, which used post-positivist knowledge claims, and thus, I preferred using Merriam (1998) and Stake (2005) in my study. This does not mean that I did not use Yin (2014) in my study. I got several guidelines from Yin’s case study methods, although I used the Merriam (1998) and Stake (1995, 2005) approach.

The districts were selected so that the diversity of the principals from three ecological belts (plain, hill, and mountain) could be captured. However, my interest in selecting these three ecological belts was not to find the differences between the principals concerning their geographical territory, but to capture their diversity of views. Three schools from each of the districts, altogether nine, were selected for the study. The principals of nine schools and two instructors of each school were the participants of the study. To explore participants who could contribute to my study, I drew on Yin (2014), who emphasizes that each case should be carefully selected to either predict similar outcomes or contrasting ones, with anticipated reasons in mind. Nonetheless, I found it challenging to identify cases that would yield both similar and contrasting results. To address this, I examined population characteristics, noting the diversity of principals in terms of age, gender, and qualifications. My aim was to capture this diversity among participants.

Additionally, I conducted focus group discussions with five students from each school to include their perspectives on their principal’s ethical leadership. This approach helped me grasp the students’ views and experiences regarding their principals. For ethical considerations, the names of participants, schools, and districts have been replaced with pseudonyms.

Tools and techniques of data collection

I was also engaged in the qualitative case study by using a protocol (Yin, 2014). Being a researcher following constructivist paradigms at this stage, I critically adopted the concept of the case study protocol in this study. I developed themes from literature and my brainstorming.

The purpose of the theme generation was to get some guidelines for my discussion with my research participants. In the process of developing a protocol, I got help from “A Guide to Developing a Multidimensional Ethical Consciousness” (Langlois, 2011, pp. 105–109). It consists of the themes of ethical leadership within the three dimensions of care, justice, and critique. I was very aware that themes developed before my field data generation could be a hindrance to seeking the meaning out of them. Therefore, in the process of implementation of the case study protocol, I, in many cases, did not consider the themes of the data protocol and discussed beyond the themes. Anyway, the primary themes were principals’ attentive listening, nurturing relationships, ensuring post-conflict wellbeing, sustaining harmony, meeting needs, granting second chances, maintaining communication, forgiving, enforcing fair discipline, applying rules impartially, following procedures, ensuring equal opportunities, promoting participation, consulting, allocating resources fairly, addressing injustices and biases, raising awareness of power dynamics, fostering consensus, and simplifying language for informed decisions.

To initiate an interview, I employed the first informal conversation with the participants. I provided the background information about my research. I also assured ethical norms I would follow. During the interview, I gave adequate opportunities for my research participants to express their opinions, and each time I made attempts to be an empathic listener (Yin, 2011) and probed on some occasions. Along with the interviews and observation, I also carried out a Focused Group Discussion (FGD) of the students studying in the TVET schools. My objective of those FGDs was to explore the views of the students toward the ethical leadership of their principals. For this, I requested the instructors of each school to select a group of approximately 6–12 persons. I wanted a small group since it might involve an intensive discussion. These FGDs were very helpful to me in exploring the views of students toward the ethical leadership of their principals. To explore the reality within the context, I did not prepare separate FGD guidelines but selected some themes from my interview protocol. This helped me not to be too structured in the process.

Data analysis and interpretation of case study

Along with the analysis of the survey data, I also had to analyze the case study data. For the analysis purpose, I transcribed all the data generated from my field participants. The transcribed data were then edited with the original record, and the data were coded. The coded data were categorized to develop themes. Three wider themes: (a) caring, (b) duties and codes, (c) transparency and empowerment emerged in the process of data analysis.

Credibility

I made the best efforts to maintain credibility at every stage of the qualitative strand by three ways: (a) consideration of possible credibility violations, (b) consideration of my implementation strategy (c) critical and reflexive role.

Mixing strategies of survey and case study findings

I used a side-by-side comparison for merged data analysis in merging. In this option, I presented the qualitative along quantitative results. Then I sought similarities and dissimilarities within the findings. While doing so, I followed Creswell and Plano Clark’s (2011) merging data analysis and assessed whether the results from the two databases were congruent or divergent, and, if they were divergent, I analyzed the data further to explain the divergent findings. The obtained result was then discussed with the support of literature, theories, and my reflection.

I was also aware of the risks, as explained by Onwuegbuzie and Johnson (2006) and Creswell and Plano Clark (2011), that may come in the process of merging results and thus developed possible strategies to overcome those threats. Out of all those strategies, my primary concern was to state the result of my research question. In the section of the joint display, I presented the findings of each strand before the result was merged. In the process, some contradictions were observed in the sense that qualitative and quantitative results did not match (Bustamante, 2019; Johnson et al., 2019). In such cases, those unmatched results were discussed further, and the reasons were sought from the data and literature. In the process, I did not favor any strand but appreciated the result of each strand. I also avoided forceful comparison of data and made maximum utilization of the results from both strands.

Likewise, I also cared about the quality of merging. Teddlie and Tashakkori (2009) believe that a mixed researcher must employ three sets of standards accessing the quality of the interferences: (a) evaluating the inferences derived from the analysis of QUAN data using QUAN standards, (b) evaluating the inference made based on QUAL data using QUAL “standards,” and (c) assessing the degree to which the meta inferences made based on these two sets of inferences are credible. Considering their concern about quality, specific strategies were applied in each phase, as discussed above. The joint display (Bustamante, 2019; Johnson et al., 2019; Peroff et al., 2020; Fetters and Guetterman, 2021) was applied for ensuring credibility of mixing.

Results of the study

Result: QUAL strand

Based on the interview and FGD of my research participants, three major themes emerged when I analyzed the data of my research participants’ perceptions regarding their ethical leadership. The themes were: (a) caring, (b) duties and codes, (c) transparency and empowerment.

Caring

The data analysis of this study indicated that care in the context of school goes together with students’ loving and nurturing needs. To address the needs, the participants held ample and strong evidence on how and why the school leaders (principals) under this study adopted “care” as a part of their ethical leadership.

The importance of administrative care was emphasized to ensure that leadership in the school was welcoming and responsive to the students. Therefore, a nurturing environment in this context is the approach to communicate care in which students (disregarding their class, caste, gender, religion, etc.) may uncover their individual potential under the kindness, considerations, and positive emotions of the school leaders. In the context of this study, I aimed at exploring how the principals of technical schools under this study use care as a psychosocial tool as a part of their ethical leadership. In this regard I asked one of the principals about the way he communicates care and love to the students studying in his school. In reply, he said, “Care needs to be communicated through language, actions and behaviors.”

The principal’s caring attitude and behaviors help the students revitalize their emotional regulation, which, in turn, encourages them to move toward academic success vigorously. This new dimension encouraged me to explore the role of care in fostering other dimensions. While enquiring, one of the principals (male and aged 51), one of the principals, said, “Principals’ care lessens the anxiety of the students.” While describing the anxiety of the students, the principal noted:

The students come to school from different family backgrounds. They are often anxious about the new environment of the school. They are also worried about social relationships, academic performance, and the challenges ahead, which are unknown to them. My role in this context is to help them identify their challenges, the course of action, and the way to deal with the new school atmosphere in which they are supposed to perform.

The above quotation shows that there needs to be a congenial environment for students in a school where they can find easy access to their principals. The more amicable the principal becomes, the easier the students share their emotions. The parent-like counseling delivered by the principal plays a therapeutic role in redirecting the students’ emotions and in building up their confidence. The students need sound official (administrative) care to tie up their psychosocial and academic performances. This care helps them keep their fear and anxiety away.

Duties and codes

My study participants discussed a series of events and their leadership practices, which vividly ascribe duties and codes as part of their ethical leadership. During data analysis, I realized that the existing laws, rules, or policies are important tools to deliver ethical leadership in school. Therefore, one of the principals was interviewed about how the existing policy helped him maintain integrity in this organization. He replied that laws and rules (standard codes of conduct) are very helpful while recruiting new staff in the school. He also emphasized the importance of laws and rules in the daily functioning of the school. Similarly, conducting annual examinations, setting criteria for publishing results, certifying the students’ performance, and fixing the facilities for the school staff are some important aspects of the school where the policy helps the principals in making just decisions. In this context, Brahma Sharma said:

We often develop codes of conduct and rules in our school contextually. The codes are up to date for principals, teachers, students, and even for hostel in-charges. Additionally, in every meeting, we write minutes, which also provide us guidance for ethical practices. However, these rules are mostly dysfunctional since we do not have a wider policy document that makes these codes functional. Without such policy guidance, even though the rules are followed, they will not be followed for long.

Codes and rules were considered essential to ensure the rights of each group in society. The practice of inclusion, equality, and equity in the technical schools under this study was reported to be one of the major ways to claim just leadership. Such practices of enjoying and utilizing the opportunities and resources available in the school, particularly through scholarship and classroom activities, do not only maintain the rights but also promote the feeling of justice and equality among those students who hardly ever sense the same in the discriminatory environment in the wider society that possibly lies beyond the school.

One way of ensuring rules in the context of school is to follow the national codes of conducts, policies and rules. But there are many contexts, due to the diversities in human socio-cultural life, where laws remain insufficient to maintain the rule of law in schools. I found most of the principals of technical schools in dilemma as there are not any policies to guide the practices of the school. Therefore, principals affirmed a number of ways out to address their ethical dilemmas created by the state of lawlessness. One of the principals said, “I use my personal conscience in certain situations, particularly when the laws do not articulate the solution for existing problems at the school context.” However, for another principal, personal conscience for ethical decisions of the school principal sometimes turns out to be inappropriate to the context, particularly when his decision senses the over imposition of his personal values. In the multi-cultural context, the value-laden decision by the school leader often tends to create conflict within the respective dimension of schools, particularly when the decision does not address their needs. In this regard, the principal further said, “It is very difficult to make room for multiple needs of stakeholders within a single decision in which the stakeholders’ sense that the decision is not just and, hence, there is a possibility of dispute within the school.”

Transparency and empowerment

The above discussion helped me to think that the recipients of ethical leadership in the schools under this study are not empowered. This means that they are not able to cultivate their needs, demands, aspirations, and wellbeing as a whole to question discrimination against them. In this sense, the care and justice provided to them remain (faulty) under some concerns. Some of the concerns are that it cannot be real justice for the target people without empowering them to cultivate the knowledge of issues for which the justice is provided to them; it is hard to determine the right care by the care receivers without giving them a learning space for cultivating the needs for care.

After I realized the above dimension, I primarily assessed the ethical leadership of the technical schools in this study in terms of transparency and empowerment. In data analysis, themes emerged in that way. Out of the above concerns, I inquired with Rajan Thapa about his view on the importance of transparency in school. His response was as follows:

Transparency in the school system provides the stakeholders with a clear window through which the practice of ethical leadership is judged by examining the behaviors and the course of action of the school principal. Under the practice of transparency, the school activities related to the ethical leadership of the principal are kept transparent so that the stakeholders can be acquainted with these activities and can make a constructive comment on the ethical decision of the principal to make the decision more meaningful and to ensure that the decision is in favor of the extensive well-being of the school.

It shows that transparency in administrative procedures provides the stakeholders with an opportunity to judge whether the decisions made or the activities performed in the schools are fair and progressive. According to the principal, transparency helps school leaders in multiple ways. First, it contributes to building up consensus on complex administrative issues such as admission procedures and recruitment of instructors in the schools. Second, it makes room for critical and constructive comments from the concerned stakeholders, like parents, students, and civil society at the local level. According to the principal, their comments pave further way to decide some key action agendas for school improvement. In the case of the above data, participatory and collaborative effort in performing the entrance examination is an example of the action agenda. Third, transparency, in a sense, is the practice of decentralization of opportunity and power to perform jobs and responsibilities where the participants agree, disagree, challenge, and support one another’s ideas, and make an effort to find a common consensus on addressing the issues.

Besides, empowerment (or disempowerment) was the other concern identified in the study (Tchida and Stout, 2023). The principal, in this respect, requires providing the stakeholders in general and students in particular with opportunities for appropriate lessons. During the discussion, I came to know that some principals of TVET facilitate the students with “expert-lecture” by calling experts from the community outside. Bal Krishna Shrestha, aged 48, a principal of TVET, claimed that he personally gives a lecture on ethics, rights, and responsibilities to be performed in the schools. According to the principal, while giving classroom lectures, he often connects his ethical issues and also the rights and responsibilities of the students within the prevailing socio-cultural and economic contexts.

I further explored empowering practices in the school, particularly under the ethical leadership of the principal. The central question I raised in this regard was: How does the ethical leadership of the principal ensure practices of empowerment? In response, one principal remarked: “In my opinion, empowering students ends when the school authority imposes rules and regulations developed by someone else rather than by the stakeholders themselves. To cultivate empowerment, I therefore create a fair environment in which stakeholders can openly discuss and collectively decide on matters concerning their well-being.” The principal emphasized that collective decision-making and its implementation matter in several ways. First, this approach convinces stakeholders that they hold an important position within the school’s overall structure. This recognition reinforces their belief that they have the power to make decisions, a power safeguarded by law. Second, because the rules are self-developed, stakeholders accept them as part of their own responsibility. In this sense, self-constructed codes free them from the feeling that external authority is being imposed upon them.

Dynamics with care, duties, transparency, and empowerment

As I went into the depths, I realized that for the principal, care and justice could be authenticated through the proper implementation of the school procedures, policies, rules, and regulations, which are developed for ensuring the maximum benefits of the stakeholders; however, empowering students to think and act critically may lead the learning environment to distortion. Such views of the principal led me to probe in the FGD with the students, in which I found them submissive toward the school leadership. One of the students, named Ranjana Dahal of the nursing program, asserted, “Our principal is the right person to guide us. What she does for us is for our welfare.” I then realized that such passive acceptance of the students about their school leadership is the product of their principal’s approach against empowering students.

However, some technical school principals under this study did not favor student empowerment. For them, the empowerment of the students often remains on the verge of being misused. One of the participants, Rishi Baniya, said, “I do not normally disclose this information to anyone, but it is a fact. It is not good to instruct students about their rights. If we inform them, they may agitate against us, which can be hard to manage.” According to the Principal, informing the students about their rights and encouraging them to activate it hampers the personal interests of the teachers and the school administrators. Some principals in my study site emphasized that administrative performances could be ensured without taking the concern of the students into account, and, hence, students’ empowerment in such cases is redundant. This shows that transparency and empowerment play an instrumental role in ensuring care and justice. However, they appeared comparatively weak components as there are fewer opportunities for the students to learn them, and there is still fear among some principals that empowering their children may destroy school practices.

Result: Quan Strand

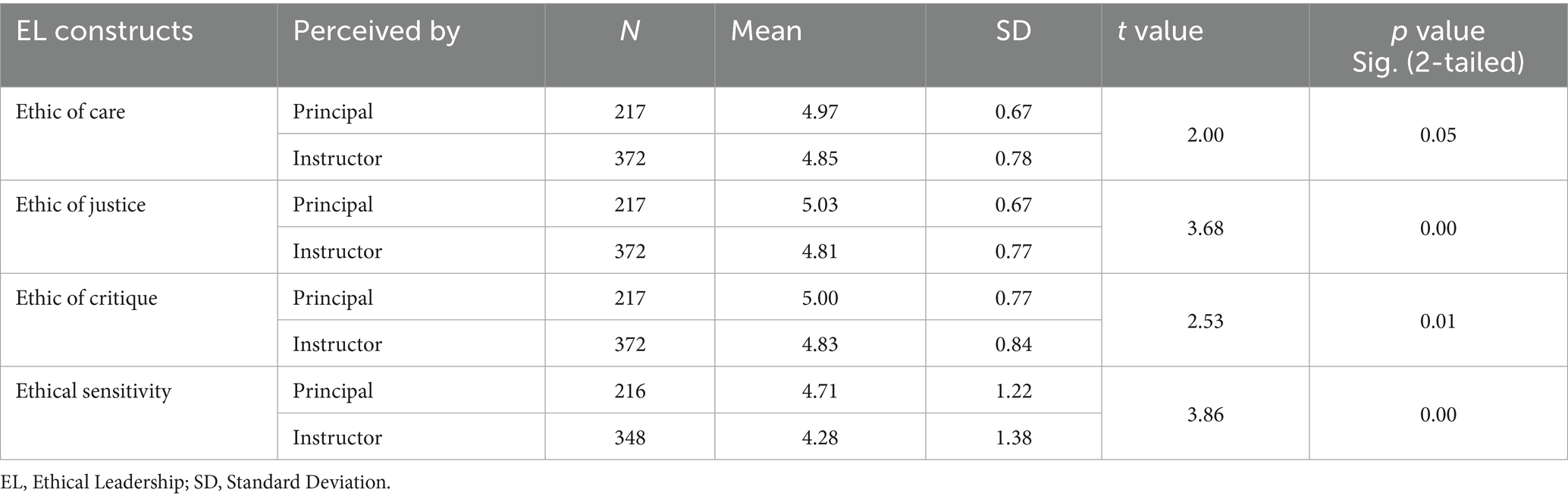

The purpose of this strand was to identify the level of principals’ ethical leadership in technical and vocational schools, as perceived by principals themselves and their fellow trainers. There were two types of respondents for this study: principals (n = 217) and instructors (n = 372). Ethical leadership has been presented as the indicators of care, justice, critique, and sensitivity. The basis of analysis was the mean and standard deviation. Further t-test was also applied to know the significant difference in the ethical leadership if viewed by the instructors differently from that of the principals. The result has been presented in Table 2.

The mean value of Table 2 indicates that principals believe their ethical leadership is better than what instructors perceive ethical leadership of the principals to be. Out of four constructs of ethical leadership of care, justice, critique, and ethical sensitivity, the mean value of justice is higher than the others. The value of mean in the justice dimension (5.03) seems to indicate that the principals show due respect and implement the duties and codes of conduct very well, although there is room to improve. However, the instructors’ mean value in justice (4.81) indicates that the instructors’ way of perceiving justice of their principals was not in line with how the principals view their own justice dimension of leadership. The result (t = 3.68, p = 0.00) shows that there is a statistical difference in the view of the principals and the instructors on ethical leadership of the principals of TVET schools. The value of critique (mean = 5.00) indicates that the principals view their way of transparency and empowering their stakeholders as better, although there is some room to improve. However, instructors did not agree (mean = 4.83) exactly to the extent of critique perceived by the principals, and there was a significant difference between the view of principals and instructors in their view of critique (t = 2.53, p = 0.01).

Regarding the ethical dimension of care, the mean value (4.97) implied that principals show a high degree of love, compassion, and empathy for the school system. However, instructors (mean = 4.85) do not share the view of the extent of care with the principals’ view (mean = 4.97). There are statistically significant differences between the perceptions of the principals and instructors (t = 2.00, p = 0.05). This kind of mean difference was also observed in ethical sensitivity. The mean value of principals regarding their view on ethical sensitivity (4.71) was higher than that of the instructors (4.28). Nonetheless, the mean value of this ethical sensitivity indicated that the principals needed to work further to enrich their ethical knowledge. The t-value and p-value (3.86 and 0.00) indicated that there are statistically significant differences in the perceptions of the principals and instructors in care. Therefore, the ethical sensitivity as perceived by the principals is statistically different from the perceptions of the instructors in the CTEVT schools.

The difference in their ethical leadership is visible when the mean scores of principals and instructors are compared with the “typology of ethical competency” (Langlois and LaPointe, 2010) presented in Table 1. For these authors, the score from 1.0 to 3.5 indicates the “traces” competency in which the leaders show their tendency toward ethical leadership. Similarly, the scores from 3.6 to 4.4, 4.5–4.8, 4.9–5.5, and 5.6–6.0 indicate the competencies of “emergence,” “presence,” “consolidation,” and “optimization,” respectively. Out of these competencies, in the “emergence” category, ethical dimensions (care, justice, and critique) first emerge; in the “presence” category, leaders can perceive ethical challenges when facing ethical dilemmas; in the “consolidation” category, ethical dimensions are actualized in both the reflection and day-to-day professional practice. In the “optimization” category, leaders demonstrate optimal ethical leadership, and thus they fully exercise their professional judgment.

When the above “typology of the ethical leadership” was compared with the ethical leadership of the principals, the differences in the view of both the principals and the instructors were visible. In the dimensions of care, justice, and critique, the principals located their ethical leadership in the “consolidation” category. Therefore, for the principals, the ethical dimensions were being consolidated within them, and these dimensions were actualized in both their reflections and their day-to-day professional behaviors and practices. Contrary to the point of view of the principals, instructors assessed their principals as being in the category of ‘presence’ and thus their care, justice, and critique were not yet actualized in both their reflections and professional practices. Concerning the ethical dimension of sensitivity, both principals and instructors viewed sensitivity as weaker than the ethics of care, justice, and critique. However, there were differences in the views of both the principals and the instructors. While the former located their ethical sensitivity in the “presence” category, the latter positioned them in the “emergence” category. This suggests that the principals’ ethical awareness still needs to emerge.

Displaying results and merging

The findings from qualitative data analysis revealed that principals’ ethical leadership consisted of (a) caring, (b) duties and codes, (c) transparency and empowerment. These themes explored from the qualitative study were similar to the dimensions of the scale used in the QUAN strand, i.e., of the Ethical Leadership Questionnaire (ELQ), since the ELQ also consists of four dimensions of ethical leadership: care, justice, critique, and ethical sensitivity (Langlois, 2011). Ethical sensitivity was the additional dimension for Langlois (2011) and is gained through knowledge of care, justice, and critique. This dimension of sensitivity, i.e., ethical knowledge, was not intended to be explored during the qualitative study because the focus of the case study was to explore the perceptions on ethical leadership (care, justice, and critique).

Through the case study, it has also been identified that care appeared comparatively stronger since it had its roots in the family and culture. The duties and codes appeared to be fair since the national legal policies and guidelines were mostly dysfunctional in the local context. Transparency and empowerment were weak among the principals owing to the domination of traditional values in deeply rooted thoughts and perceptions. This inference from the case study was supported by the inference from the survey research.

The survey research showed that in the view of the principals, the ethical dimensions (care, justice, and critique) were being consolidated within them, and these were actualized in both their reflections and their day-to-day professional behavior and practice (Langlois and LaPointe, 2010). In the view of instructors, their principals were able to perceive ethical challenges, but they had to work further to consolidate their ethical dimensions (care, justice, and critique) and to actualize those dimensions in both their reflections and practices.

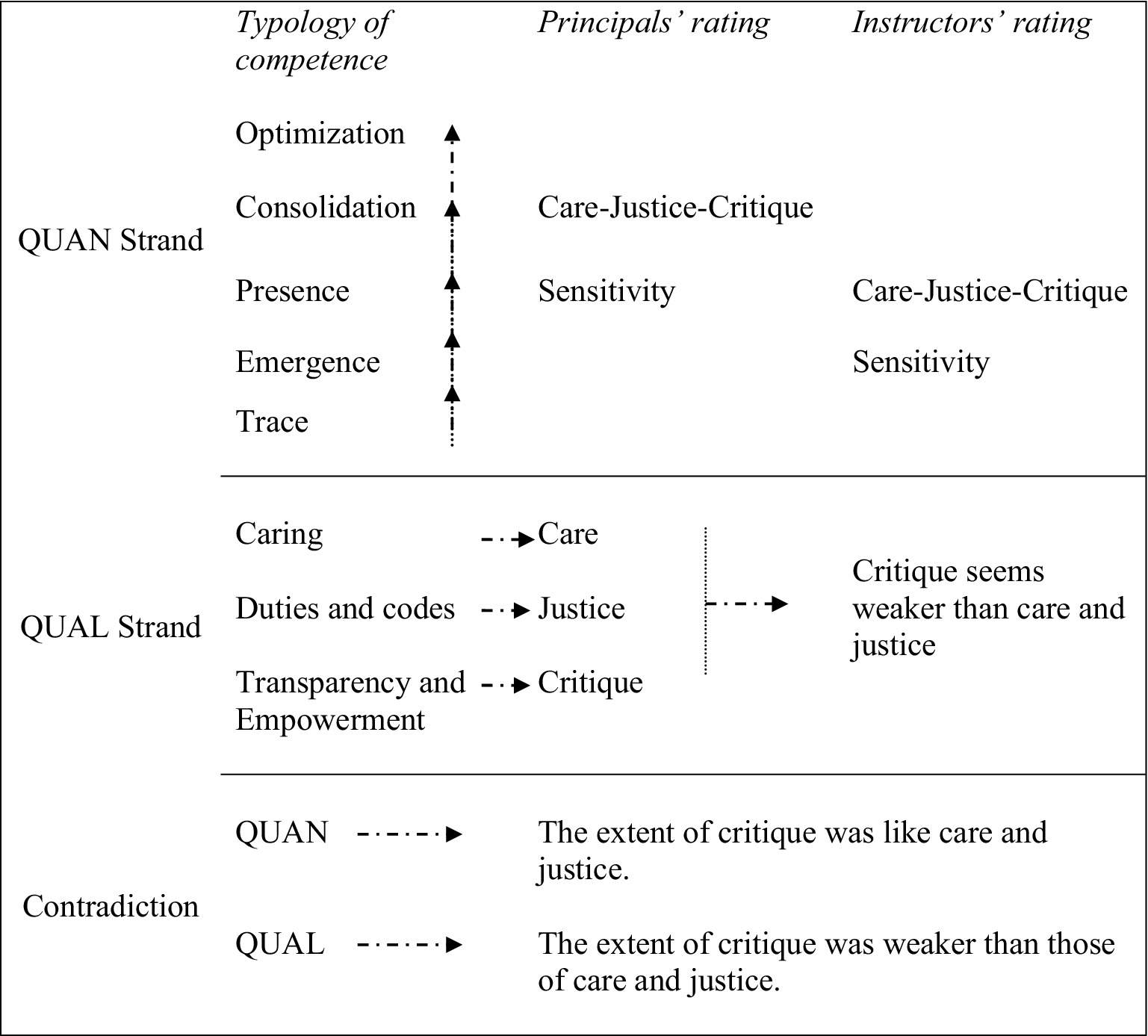

Both qualitative and quantitative inferences indicated that in the case of care and justice, principals had to work further. In the case of ethics of critique, the qualitative study showed that it was weaker than those of justice and care. The quantitative study did not support the same but signaled that the extent of critique was similar to the extent of care and justice (Figure 3). By this, a contradiction in the findings of the QUAN and QUAL strands was obtained.

Discussion of results: contradictions explained

The merging of findings showed that principals of TVET schools practice ethical leadership in the form of care, justice, and critique. Among them, the findings of qualitative inquiry show that care and justice become functional and effective only when the recipients internalize the issues and cultivate knowledge for practicing care and justice. However, it requires their rigorous empowerment to make an appropriate choice for care and justice. They also need to possess an analytical understanding of the given situation to fix the type or form of care and justice that would ensure their wellbeing.

The above explanation shows that the concept of ethical leadership within TVET has been woven under three themes of care, justice, and critique (Berges Puyo, 2022; Bhattarai and Maharjan, 2016; Starratt, 1991). Their combination is useful to examine several un/ethical situations in schools (Starratt, 2012). The findings of this study also coincide with the model developed by Robert Starrat in 1990 and further elaborated in 2012, and Berges Puyo (2022), Kayastha (2024), and Sherchan et al. (2024) also suggested for integration of care, justice, and critique for ethical leadership in educational institutions. Additionally, Langlois (2011) added one more component named ethical sensitivity. For Langlois (2011), one can acquire ethical sensitivity by internalizing the ethics of care, justice, and critique. This dimension of ethical sensitivity is also captured in the QUAN strand of study since this study used the tool developed by Langlois and her team. For example, Stefkovich and Begley (2007) mention that principals’ ability to understand their own values and ethical awareness helps them to be more ethical. However, in the context of this study, ethical sensitivity, as shown by QUAN strand, was explored as weaker in comparison to care, justice, and critique. It was so weak that it was not even consolidated by the principals to harness its benefits to contribute to ethical leadership. By weak sensitivity, the study further revealed that care, justice, and critique were not actualized in the reflections and day-to-day professional behavior and practice of the principal. Langlois and LaPointe (2010) have also found that activation of ethical sensitivity promotes ethical leadership in schools. With limited ethical sensitivity, the principals lack their ability to examine moral values in a particular ethical situation (Tuana, 2007). With the weaker ethical sensitivity, principals are not capable in these dimensions as expected, which obviously hinders ethical leadership practices of schools.

Above all, with the weaker position of ethical sensitivity, the principals are weaker in the ethics of critique. Langlois et al. (2014) have also found that the ethics of care and justice are hardly associated with ethical sensitivity, but the ethics of critique is much correlated with the sensitivity. The findings of the QUAL strand of this study also indicated that principals’ ethics of critique were weaker in comparison to the ethics of care and justice. The weak ethics of critique were identified by the results of the QUAL strand of the study. The QUAN result showed that ethical sensitivity was weaker as compared to the ethics of care, justice, and critique. With their weaker position of ethical sensitivity, they were not able to examine the ethics of critique, and it seemed higher in the survey. Langlois et al. (2014) have also shown that the principals are required to give importance to the ethics of critique as it helps for the promotion of ethical awareness and justice in schools. This shows that the ethics of critique is a major area to intervene in the context of schools, which can be enhanced by bringing awareness to school stakeholders with the learning of their rights and responsibilities (Langlois, 2011). Critique in the TVET sector is important in the sense that it induces the stakeholders to raise voices against oppression, discrimination, and exclusion from consuming privileges in the school system.

Limitations

The results of the study have to be examined with the following limitations. First, the scale to measure ethical leadership was taken from the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS), constructed by Langlois, Houme, and LaPointe in Laval, Canada. The scale constructed in the Western world was contextualized while piloting in the local culture of Nepal. However, the contextualization in piloting could not revisit the dimensions of ethical leadership. A scale could have been constructed in the local context to capture the essence of ethical leadership rooted in the local culture and values. Second, the sample was taken from a population of 377 TVET schools, listed in CTEVT (2012). The number of TVET schools has increased significantly since the time of data collection, and the context has evolved; therefore, the findings related to TVET schools may not be fully generalizable. Third, in consideration of the sample size of the instructors, two of them from each school were selected. Depending on their number, their sample size could have been increased. Fourth, the envelope containing the questionnaire for all respondents was sent to each principal of the schools, and the principals filled up the questionnaires themselves and handed over two additional questionnaires to the instructors. In this connection, the principals’ choice concerning the selection of the instructors might not support the view of all instructors of the school. Fifth, although nine schools were visited for qualitative data collection, the researcher could not pay equal attention to each school, but rigor was maintained through engagement in certain cases of interest.

Implications of the study

The findings from this study have implications for both the research topic and methods. The findings of the study showed principals’ care in schools is visible through love and compassion; justice through the fair implementation of the codes of conduct and rules; and critique through transparency and empowerment. However, in practice, the principals do not demonstrate optimal care and justice to fully exercise their professional judgment. The contribution of the critical role is perceived to facilitate and legitimize ethics of care and justice, but the critical role is dominated by the cultural values of obedience and silence. In such situations of the weak extent of critique, ethical sensitivity or awareness is necessary so that the principals can understand the contribution of a critical role in ethical decision-making.

Before reaching the above implication, the findings of both QUAN and QUAL strands were merged, and the merger helped to produce credible results. Both strands had a similar result that ethical leadership was rooted in schools in the form of care, justice, and critique. However, some contradictions were observed in the triangulation. The QUAN strand had a result that care, justice, and critique were equally consolidated within the principals, and these were actualized in both their reflections and their day-to-day professional behavior and practice. However, in the case of ethics of critique, QUAL showed that it was weaker than those of justice and care, as the principals of the schools were largely guided by the traditional practices. The contradiction was answered by the QUAN strand again. The QUAN strand had a finding that ethical sensitivity or awareness was weaker in comparison to care, justice, and critique in the views of both principals and instructors. With weak ethical awareness, both principals and instructors did not reflect the ethics of critique in their professional lives. The idea was further supported by the literature that clearly outlines that the ethics of critique is largely related to ethical sensitivity rather than that of care and justice. Therefore, the interaction between strands is very useful to overcome contradictions obtained from post-positivists and constructivists and to use the strengths of both paradigms.

This article contributes to Mixed Methods Research by presenting an example that applying the paradigm of dialectical pluralism is essential not only to get the benefits of both post-positivist and constructivist paradigms but to reach the next level of insights in the process of answering the contradictions of the result.

Conclusion

To navigate and reconcile differing perspectives, the paradigm of dialectical pluralism can be useful. This approach facilitates synthesizing insights drawn from contrasting paradigms, such as post-positivism and constructivism, thereby enriching the overall understanding of the research agenda. This insight has been drawn from the study on ethical leadership of the principals that began with an assumption that ethical leadership has some universal meanings and is contextual as well. Everyone perceives and explains ethical leadership differently; however, there are some well-agreed ideas concerning ethical leadership in educational institutions. Considering the same, the methodologies were largely guided by the paradigms of post-positivism and constructivism. To capture the essence of the post-positivist paradigm, numeric data on ethical leadership of the principals were collected by using survey methodology. The case study methodology was used to collect narrative data with taking into consideration of constructivist paradigm. There were two parallel strands of data collection and analysis by using survey and case study methodologies, respectively. The results from both methodologies were interacted after the findings were drawn. By synthesizing these two methods, insights were developed, and contradictions were observed. In the study, the next level of knowledge building would not be possible without answering the contradictions. Therefore, the paradigm of dialectical pluralism helps to get the maximum benefits of two contrasting paradigms of post-positivism and constructionism, particularly in studying ethical leadership in schools.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Software, Project administration, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The author gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance provided by the UGC.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, R., Majeed, S., and Ullah, S. (2023). Exploration of ethical leadership in teachers in government high schools of Lahore. Pak. Lang. Human. Rev. 7, 388–402. doi: 10.47205/plhr.2023(7-III)34

Ahmed, S. K. (2024). How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: a simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 12:100662. doi: 10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662

Allemang, B., Sitter, K., and Dimitropoulos, G. (2022). Pragmatism as a paradigm for patient-oriented research. Health Expect. 25, 38–47. doi: 10.1111/hex.13384

Andersson, H., Svensson, A., Frank, C., Rantala, A., Holmberg, M., and Bremer, A. (2022). Ethics education to support ethical competence learning in healthcare: an integrative systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 23:29. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00766-z

Barker, M. (2003). Assessing the “quality” in qualitative research: the case of text audience relations. Eur. J. Commun. 18, 315–335. doi: 10.1177/02673231030183002

Bazeley, P. (2012). Integrative analysis strategies for mixed data sources. Am. Behav. Sci. 56, 814–828. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426330

Begley, P. T. (2006). Self-knowledge, capacity and sensitivity: prerequisites to authentic leadership by school principals. J. Educ. Adm. 44, 570–589. doi: 10.1108/09578230610704792

Bennett, M. J. (2023). Paradigmatic assumptions and a developmental approach to intercultural learning. In M. Vande Berg, R. M. Paige, K. H. Lou (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it. 90–114. doi: 10.4324/9781003447184-6

Berges Puyo, J. (2022). Ethical leadership in education: a uniting view through ethics of care, justice, critique, and heartful education. J. Cult. Values Educ. 5, 140–151. doi: 10.46303/jcve.2022.24

Bhattarai, P. C. (2019). Ethics of care among TVET schools’ principals: is it reflected? J. Train. Dev. 4, 24–33. doi: 10.3126/jtd.v4i0.26832

Bhattarai, P. C. (2021). Reforming technical and vocational education and training (TVET) sector: what next? Int. J. Multidiscip. Perspect. High. Educ. 5, 106–112. doi: 10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2505

Bhattarai, P. C., and Maharjan, J. (2016). “Ethical decision making among women education leaders: a case of Nepal” in Racially and ethnically diverse women leading education: a worldview (West Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 219–233.

Bhattarai, P. C., Parajuli, M. N., Gautam, S., Paudel, P. K., Bhurtel, A., and Sharma, A. (2025). Education–work transition: skill gaps in the construction industry. Front. Built Environ. 11:1623609. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1623609

Bhurtel, A. (2016). Curriculum issues in Nepal: a study on graduates’ perception. J. Train. Dev. 2, 57–68. doi: 10.3126/jtd.v2i0.15439

Boblin, S. L., Ireland, S., Kirkpatrick, H., and Robertson, K. (2013). Using Stake's qualitative case study approach to explore implementation of evidence-based. Qual. Health Res. 23, 1267–1275. doi: 10.1177/1049732313502128

Brown, P. A. (2008). A review of the literature on case study research. Can. J. New Scholars Educ. 1, 1–13. Available online at: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjnse/article/view/30395

Bryman, A. (2007). Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 8–22. doi: 10.1177/2345678906290531

Bustamante, C. (2019). TPACK and teachers of Spanish: development of a theory-based joint display in a mixed methods research case study. J. Mixed Methods Res. 13, 163–178. doi: 10.1177/1558689817712119

Campbell, M. A. (2004). What to do? An exploration of ethical issues for principals and school counsellors. Principia J. Queensland Second. Principals' Assoc. 1, 7–9. Available online at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/4336/

Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training (CTEVT). (2012). List of institutions and programs under CTEVT. Bhaktapur, Nepal: Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training.

Creamer, E. G. (2018). An introduction to fully integrated mixed method research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Feilzer, M. Y. (2010). Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. J. Mixed Methods Res. 4, 6–16. doi: 10.1177/1558689809349691

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., and Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs: principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 48, 2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Fetters, M. D., and Guetterman, T. C. (2021). “Development of a joint display as a mixed analysis” in The Routledge reviewer’s guide to mixed methods analysis (New York: Routledge), 259–276.

Fetters, M. D., and Molina-Azorin, J. F. (2019). A call for expanding philosophical perspectives to create a more “worldly” field of mixed methods: the example of yinyang philosophy. J. Mixed Methods Res. 13, 15–18. doi: 10.1177/1558689818816886

Ghorbani, Z., Esmaeili, S., Hosseinimoghadam, M., Jamshidi, Z., Moqaddam, S. F. M., and Rostami, K. (2023). The mediating role of ethical leadership on professional commitment and moral sensitivity in the control of blood pressure by intensive care unit (ICU) nurses. Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertension 18, 322–329. Available online at: https://revhipertension.com/rlh_7_2023/6_the_mediating_role_of_ethical_leadership_on.pdf

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Green, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., and Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 11, 255–274. doi: 10.3102/01623737011003255

Greene, J. C. (2015). “Preserving distinctions within the multimethod and mixed methods research merger” in The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. eds. S. Hesse-Biber and R. B. Johnson (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 606–615.

Guba, E. G., and Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). “Competing paradigms in qualitative research” in Handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 163–194.

Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., and Mills, J. (2017). Case study research: foundations and methodological orientations. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 18. doi: 10.17169/fqs-18.1.2655

Harrits, G. S. (2011). More than method? A discussion of paradigm differences within mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 5, 150–166. doi: 10.1177/1558689811402506

Johnson, R. B. (2008). Living with tensions: the dialectic approach. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2, 203–207. doi: 10.1177/1558689808318043

Johnson, R. B. (2017). Dialectical pluralism: a metaparadigm whose time has come. J. Mixed Methods Res. 11, 156–173. doi: 10.1177/1558689815607692

Johnson, R. E., Grove, A. L., and Clarke, A. (2019). Pillar integration process: a joint display technique to integrate data in mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 13, 301–320. doi: 10.1177/1558689817743108

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed method research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 112–132. doi: 10.1177/1558689806298224

Kayastha, C. (2024). Ethical leadership and its influence on teachers’ engagement: a post positivist research at public schools in Bhaktapur, Nepal, (Unpublished MPhil dissertation). Lalitpur, Nepal: Kathmandu University School of Education.

Langlois, L. (2011). The anatomy of ethical leadership: to lead our organizations in a conscientious and authentic manner. Laval, Canada: University of Laval.

Langlois, L., and LaPointe, C. (2010). Can ethics be learned? Results from a three-year action-research project. J. Educ. Adm. 48, 147–163. doi: 10.1108/09578231011027824

Langlois, L., Lapointe, C., Valois, P., and Leeuw, A. (2014). Development and validity of the ethical leadership questionnaire. J. Educ. Adm. 52, 310–331. doi: 10.1108/JEA-10-2012-0110

Maxwell, J. A., and Mittapalli, K. (2010). “Realism as a stance for mixed methods research” in Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie. 2nd ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 145–167.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Mertens, D. M. (2007). Transformative paradigm: mixed methods and social justice. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 212–225. doi: 10.1177/1558689807302811

Mertens, D. M. (2012). What comes first? The paradigm or the approach? J. Mixed Methods Res. 6, 255–257. doi: 10.1177/1558689812461574

Mills, J. (2014). “Methodology and methods” in Qualitative methodology: a practical guide. eds. J. Mills and M. Birks (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 31–47.

Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 48–76. doi: 10.1177/2345678906292462

Morgan, D. L. (2014). Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qual. Inq. 20, 1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/1077800413513733

Muktan, R., and Bhattarai, P. C. (2023). Addressing ethical dilemmas: a case of community schools’ head-teachers in Nepal. Int. J. Educ. Organ. Leadersh. 30, 77–88. doi: 10.18848/2329-1656/CGP/v30i01/77-88

Neupane, Y., Chandra,, Bhattarai, P. C., and Lowery, C. L. (2022). Prospect of ethical decision-making practices in community schools. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2022.2120632

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Johnson, R. B. (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Res. Sch. 13, 48–63. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228340166_The_Validity_Issues_in_Mixed_Research

Peroff, D. M., Morais, D. B., Seekamp, E., Sills, E., and Wallace, T. (2020). Assessing residents’ place attachment to the Guatemalan Maya landscape through mixed methods photo elicitation. J. Mixed Methods Res. 14, 379–402. doi: 10.1177/1558689819845800

Renold, U., and Caves, K. (2017). Constitutional reform and its impact on TVET governance in Nepal: a report in support of developing understanding and finding the way forward for federalizing the TVET sector in Nepal (KOF studies no. 89). Zurich: ETH Zurich, KOF Swiss Economic Institute.

Schoonenboom, J. (2019). A performative paradigm for mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 13, 284–300. doi: 10.1177/1558689817722889

Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Ethical decision-making theory: an integrated approach. J. Bus. Ethics 139, 755–776. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2886-8

Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 10, 319–334. doi: 10.1177/1558689815575861

Shapiro, J. P., and Stefkovich, J. A. (2005). Ethical leadership and decision making in education: appling theoretical perspectives to complex dilemmas. 2nd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Shapiro, J. P., and Stefkovich, J. A. (2021). “Viewing ethical dilemmas through multiple paradigms” in Ethical leadership and decision making in education (New York, NY: Routledge), 11–35.

Sherchan, B., Baskota, P., and Saud, M. S. (2024). Ethics as a transformational strength in education: an ethical leadership perspective. Adv. Qual. Res. 2, 31–40. doi: 10.31098/aqr.v2i1.1956

Stake, R. E. (2005). “Qualitative case studies” in The Sage handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. 3rd ed (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 443–466.

Starratt, R. J. (1991). Building an ethical school: a theory for practice in educational leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2, 185–202.

Stefkovich, J., and Begley, P. T. (2007). Integrating values and ethics into post- secondary teaching for leadership development principles, concepts, and strategies. J. Educ. Adm. 45, 398–412. doi: 10.1108/09578230710762427

Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches (applied social research methods series, 46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tchida, C. V., and Stout, M. (2023). Disempowerment versus empowerment: analyzing power dynamics in professional community development. Community Dev. 55, 386–406. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2023.2247470