- 1Institute of Educational Psychology, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Brunswick, Germany

- 2Department of Didactics of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Student teachers’ enthusiasm can be understood as the anticipated enjoyment, excitement, and pleasure they experience in their professional activities. However, it is unclear whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is identical to general enthusiasm for teaching or to interest in ICT (Information and Communications Technology) and which variables, if applicable, predict it. This cross-sectional online study with N = 143 students shows that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is a distinct construct from general enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT. Multiple regression analysis using model averaging within the information-theoretic approach shows that the most important predictors of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media are perceived utility value of digital media, interest in ICT, teachers’ self-efficacy and self-efficacy regarding media use. Media-related predictors—particularly perceived utility of digital media and interest in ICT—found be to the most influential. Furthermore, perceived utility value of digital media and general teachers’ self-efficacy consistently emerge as the significant predictors with moderate effects across the top five models, which strongly aligns with situated expectancy-value theory. These findings underscore the importance of conceptualizing enthusiasm in a context-specific way and highlight the need to strengthen students’ perceived utility value of digital media in teaching and their self-efficacy for the future teaching profession through diverse practice-oriented learning opportunities to enhance enthusiasm for teaching with digital media.

1 Introduction

Enthusiasm can be understood as a self-determined motivation that positively influences a variety of outcomes, particularly teaching quality and teachers’ well-being (Burić and Moè, 2020; Kunter et al., 2011; Lazarides et al., 2021; Praetorius et al., 2017; Shao, 2023). Therefore, enthusiasm is a highly sought-after trait among student teachers (Keller et al., 2013). However, motivation always relates to specific activities in specific contexts (Ryan and Deci, 2018). Digital transformation and artificial intelligence impact teaching and learning processes (European Commission, 2020). COVID-19 in particular has brought the dynamics of teaching with digital media into sharp focus (Beardsley et al., 2021; Chen and Hou, 2025; Özdemir, 2025; Schubatzky et al., 2023). Teachers and student teachers therefore need to equip themselves not only with specific knowledge and digital skills but also with the motivation to use digital media in teaching (Backfisch et al., 2020; Hecht et al., 2021; Wijaya et al., 2025). Yet, while most teachers in Germany believe that digital media enhance teaching if used appropriately, only a minority use them for a variety of teaching purposes, despite their high self-assessed computer and information-related skills (Drossel et al., 2019, 2024). This gap underlines the need for a closer examination of student teachers’ motivation, particularly for their enthusiasm (Stieler-Hunt and Jones, 2015). Although some studies have investigated the antecedents of enthusiasm (Burić and Moè, 2020; Chen et al., 2024; Keller et al., 2014; Kouhsari et al., 2024), most of them have addressed teachers’ enthusiasm in a general teaching context. To date, there is a notable gap in our knowledge of how student teachers’ enthusiasm in the context of teaching with digital is influenced by their motivational characteristics (Bock et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). The present study therefore examines whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is identical to enthusiasm for teaching (as an activity-related intrinsic orientation) or interest in ICT (Information and Communications Technology; as a topic-related intrinsic value). When applicable the study further examines which variables predict enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, embedded in situational expectancy-value theory (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020).

2 Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media

Enthusiasm is a form of motivation in which teachers experience positive emotions and high levels of meaningfulness in their professional activities (Kunter and Holzberger, 2014). Intrinsic motivation is present when an action itself is perceived as joyful and rewarding, while perceived meaningfulness is connected to identified and integrated regulation (Ryan and Deci, 2018). Enthusiasm is thus very closely related to self-determined motivation (autonomous motivation) and interest as the enduring cognitive and affective disposition of a person to engage themselves with an object (Renninger and Hidi, 2016). Accordingly, studies show a distinction between enthusiasm for the subject and enthusiasm for teaching (Kunter et al., 2011). Enthusiasm for the subject contributes very little to explaining the quality of teaching, the students’ motivational development in mathematics, or their learning performance, but enthusiasm for teaching does (Kunter et al., 2008; Kunter, 2013).

Enthusiasm is therefore regarded as an important representation of teachers’ motivational orientation, which constitutes a central aspect of the psychological functioning underlying teaching-related actions (Baumert and Kunter, 2006). Enthusiasm is not innate, but rather can be acquired and fostered through learning (Ginsberg and Wlodkowski, 2019; Kunter et al., 2013). Recent research highlights its relevance even in the pre-service stage. Holzberger et al. (2016) showed that more enthusiastic teacher candidates invest greater effort, benefit more from teaching-related learning opportunities, and display more cognitively demanding instructional practices. Similarly, Bock et al. (2021) found that enthusiasm for teaching is also an important predictor in the earliest stages of teachers’ careers, which is significantly associated with academic self-concept, intrinsic career choice motives and occupational commitment.

Student teachers’ anticipated enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can be understood as an intrinsic orientation toward using digital media in teaching (cf. Kunter et al., 2008). It reflects the prospective activity-related positive emotions (enjoyment, excitement, and pleasure) and the sense of meaningfulness associated with using digital media in teaching, potentially shaping future behaviors (Öngel and Tabancali, 2022). In line with this definition, student teachers who are enthusiastic about teaching with digital media are motivated by the anticipated positive affective experiences, and therefore look forward to use digital media in their teaching activities (cf. Bock et al., 2021). Since motivation relates to specific activities and highly depends on the context, it is unclear whether general enthusiasm for teaching encompasses enthusiasm for teaching with digital media or whether they should be distinguished.

2.1 Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and its relation to general enthusiasm for teaching

If enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching are one uniform construct, student teachers who are genuinely enthusiastic about teaching would enjoy teaching with digital media as well. Similarly, student teachers who are excited about using digital media in teaching must love teaching a great deal. In light of self-determination theory, however, one can assume that enthusiasm varies depending on the specific characteristics of the activity and the context, e.g., when the basic psychological need to experience competence is satisfied or frustrated (Ryan and Deci, 2018; Burić and Moè, 2020). And indeed, distinct objects of enthusiasm contribute to the variability of enthusiasm across different teaching contexts (Chen et al., 2024; Kouhsari et al., 2024; Kunter et al., 2011). If digital media are used, the teaching context and the prospective emotions (Beardsley et al., 2021) change accordingly. It is therefore conceivable that general enthusiasm for teaching and enthusiasm for teaching with digital media are distinct but correlated constructs.

2.2 Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and its relation to interest in ICT

Teaching with digital media involves not only teaching as an activity, but also information and communication technologies (ICT) as an object. Individual interest can be defined as the enduring cognitive and affective disposition to engage with an object (Renninger and Hidi, 2016). Accordingly, interest in ICT is defined as an individual’s long-term preference for dealing with topics, tasks, or activities related to ICT (Goldhammer et al., 2016, p. 341). Interest in ICT thus spans various technology-related activities such as creating multimedia applications including texts, graphs, and videos, as well as using applications in a digital format. The interest in ICT and enthusiasm for teaching with digital media therefore have the enjoyment and personal relevance of working with ICT in common. Yet, they differ in their focus and scope. Interest is conceptually closer to enjoyment in engaging in a taught subject, which is not only feeling-related but also value-related (Kunter et al., 2011; Schiefele et al., 2013). Studies on enthusiasm on the other hand emphasize the affective experience of the respective activities (Kunter et al., 2008). Furthermore, the object of interest in ICT encompasses the use of technologies and the production of content in a digital format, whereas the object of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media refers to teaching activities supported by digital media. Student teachers who are interested in using digital media in daily life are thus not necessarily enthusiastic about integrating digital media into future teaching, if they do not feel enthusiastic about teaching (Andersson, 2006). Nevertheless, it is an open question whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can be differentiated from interest in ICT.

3 Antecedents of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media

Teaching with digital media involves both teaching-related and media-related activities, and it is more than simply using digital media alongside the non-digital lessons. Integrating digital media in teaching needs to be triggered by media-related motivation. Conversely, creating multimedia learning materials to enhance a deeper understanding requires teachers to search for digital resources, modify and present them, and also integrate them into learner-centered approaches—this requires an additional amount of teaching-related motivation. Therefore, one can assume that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is influenced by both teaching- and media-related motivational variables. Possible relevant predictors can be derived from the situational expectancy-value theory (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). This theory assumes that the motivation to perform an activity is influenced by the individual’s perceptions of the value of the activity and the probability of success. Therefore, the following variables seem to be plausible predictors of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media: enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT (intrinsic value)—if they are distinct constructs from enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, perceived benefits of digital media (utility value), as well as teachers’ specific self-efficacy (individuals’ beliefs). In the following section, a brief introduction for each construct and a theoretical and empirical rationale for why they might be predictors for enthusiasm for teaching with digital media are presented.

3.1 Intrinsic values regarding teaching and digital media

Intrinsic value is the interest and enjoyment in performing the activities (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). In the context of teaching with digital media, it is therefore reasonable to distinguish between the intrinsic value associated with teaching itself and that associated with using digital media.

General enthusiasm for teaching is closely related to anticipated positive emotions (e.g., joy, excitement and pleasure) in teaching, reflecting an intrinsic value of teaching. This intrinsic value can extend to or transfer to related domains, such as teaching with digital media (cf. Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). According to the generalized internal/external frame of reference model (I/E model, Möller et al., 2016), individuals evaluate the value of their tasks and their motivation in different domains by comparing them with each other, namely the internal dimensional comparison process. Whereas external, social comparisons (e.g., “How good am I at teaching with digital media compared to my peers?”) use others as a reference standard, internal, dimensional comparisons draw on information about different attributes of oneself (e.g., “How good am I at using digital media in teaching compared to teaching without it?”). In this process, it is the individual’s own view of the distance between the tasks that determines whether they are close or distant comparisons (Möller, 2024; Wigfield et al., 2020). When digital media is perceived as a means to support good teaching, rather than as a separate or unrelated task, internal dimensional comparisons between the two may occur. Enthusiasm for teaching has positive effects on teaching practices, such as motivating (student) teachers to invest more effort in preparing learning materials, which includes proactively searching for digital media and making good use of digital media to improve teaching quality (cf. Bock et al., 2021). A general enthusiasm for teaching can naturally extend to excitement about using digital media in teaching processes if digital media are considered as “natural” elements of teaching practice. If the use of digital media and traditional classroom teaching without digital media are perceived as distant domains, opportunities for internal comparison between them are limited. This would imply that variability in enthusiasm for teaching with digital media occurs primarily between individuals, even among those with similar levels of general enthusiasm for teaching. Following the call of educational researchers and policy frameworks emphasizing the importance of digitalization in education (European Commission, 2020), the present study assumes that general enthusiasm for teaching is positively associated with enthusiasm for teaching with digital media.

Similarly, the intrinsic value of using digital media can be operationalized as ones’ interest in ICT, a value-related motivational construct (Kunter et al., 2011; Schiefele et al., 2013) representing the enjoyment attributed to teach with digital media. This domain-specific interest is frequently regarded as an expression of intrinsic value within a given activity (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). Since the use of digital media is a precondition for teaching with digital media, interest in ICT might play an important role in whether or not one is enthusiastic about teaching with digital media. For individuals with a strong interest in ICT, teaching with digital media is an interest-based activity connected with enjoyment and a sense of involvement (Goldhammer et al., 2016). Individuals with a strong interest in ICT show a greater willingness to acquire new information on digital media and to use their ICT-related skills in teaching situations (Krapp, 2007). Interest in ICT may therefore influence on whether or not an individual is enthusiastic about teaching with digital media.

3.2 Utility value of digital media

Whereas attainment value is related to an individual’s sense of self-identity, utility value refers to the perceived benefits of achieving goals (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020); for instance, using digital media can be perceived as helpful for attaining desired outcomes in teaching (e.g., motivated students). The perceived utility value also relates to an individual’s internalization process by transferring the attitudes and the goals from the outside to the inside (Deci and Ryan, 1993; Ryan and Deci, 2018). In self-determination theory, Deci and Ryan (1993) extended the intrinsic-extrinsic dichotomy of motivation into four levels of internalization of individuals—external, introjected, identified and integrated level. Perceived utility value corresponds different levels of internalization up to the identified level which emphasizes an internal regulation based on the utility of the behavior. Even though this level is not fully intrinsic, it expresses a higher internalized level compared to the extrinsic motivation as well as the external and introjected level of internalization. It is therefore reasonable to assume an association between perceived utility value and enthusiasm. Thus the construct perceived utility value of digital media is assumed to be a representative construct of utility value in the context of teaching with digital media. Within the technology acceptance model, Davis (1986) proposes that the perceived utility reflects the extent to which an individual believes that using digital media would yield positive outcomes, including emotional experiences during these activities (Beardsley et al., 2021; Davis et al., 1992). The more closely activities match one’s own beliefs and values, the more autonomous and self-determined the action is carried out, even if the action is motivated by the outcome (Ryan and Deci, 2018). Enthusiastic teaching with digital media may thus also occur when (student) teachers are extrinsically motivated (Kunter et al., 2008). This is consistent with the notion that utility value influences subsequent motivation, particularly in terms of intrinsic valuing (Hulleman and Harackiewicz, 2009; Wigfield et al., 2020).

3.3 Expectancy-related reasons: self-efficacy

Expectancy beliefs of success are understood as individuals’ beliefs about how well they will perform an activity in the future (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020), which is analogous to self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). The latter focuses on an individuals’ belief in their ability to cope with even challenging situations in the future (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 2002). Self-efficacy is defined as the domain- and situation-specific belief that one can successfully perform an action to reach specific goals even against resistance. It influences perceptions, emotions, motivation, and actual performance (Bandura, 1997) and is therefore seen as a personal resource (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 2002). Self-efficacy relates to specific actions in a specific context. The more specifically self-efficacy is measured, the better it can predict experience, behavior and performance (Bandura, 1997).

Teachers’ self-efficacy refers to teachers’ judgement of their own ability to foster students’ learning processes and learning motivation successfully, even when students are unmotivated or experiencing challenges (Bandura, 1997). It contributes to active self-regulation even in stressful situations and leads to various desirable outcomes, especially to higher levels of enjoyment and enthusiasm for teaching (Bleck, 2019; Burić and Moè, 2020; Kouhsari et al., 2024; Lazarides et al., 2021; Taxer and Frenzel, 2018).

Self-efficacy regarding media use on the other hand is seen as a personal belief about the general use of media, which may influence the individual’s readiness to deal with digital media or to handle new digitally supported learning settings in daily life (Pumptow, 2020). The fact that self-efficacy is context-specific entails that teachers with a high level of self-efficacy in teaching and teachers with high self-efficacy in media use do not automatically have high self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching. Teaching with digital media is a complex process with a variety of challenges due to the dynamic interactions between teachers, students, learning content, and digital media.

Self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching can therefore be defined as the belief that one can successfully use digital media to promote students’ learning, motivation, and personal development in instructional settings (cf. Bandura, 1997). It influences the individual’s willingness to use digital media for teaching (Dinse de Salas, 2019) and positive emotions, particularly the feeling of joy (Burić and Moè, 2020).

Seeing oneself as being capable of handling tough situations, might increase an individual’s enthusiasm (cf. Ryan and Deci, 2018). In addition, student teachers with high levels of self-efficacy may be more likely to seek out and engage in professional development opportunities, such as the innovative use of digital media to support teaching and learning, and feel confident in doing so. This sense of accomplishment may have a positive impact on their enthusiasm. Overall, it is thus assumed that teachers’ enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is influenced by their sense of self-efficacy, particularly the self-efficacy for teaching with digital media due to context specificity (Bandura, 1997). Nevertheless, most of the research evidence is drawn from teachers. As student teachers and in-service teachers cannot be conflated, the impact of self-efficacy on enthusiasm has not been sufficiently explored in relation to student teachers (Wijaya et al., 2025).

4 The present study

The present study addresses two research questions: (RQ1) Is enthusiasm for teaching with digital media a distinct construct from both general enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT? (RQ2) And if so, which of the aforementioned variables can predict enthusiasm for teaching with digital media?

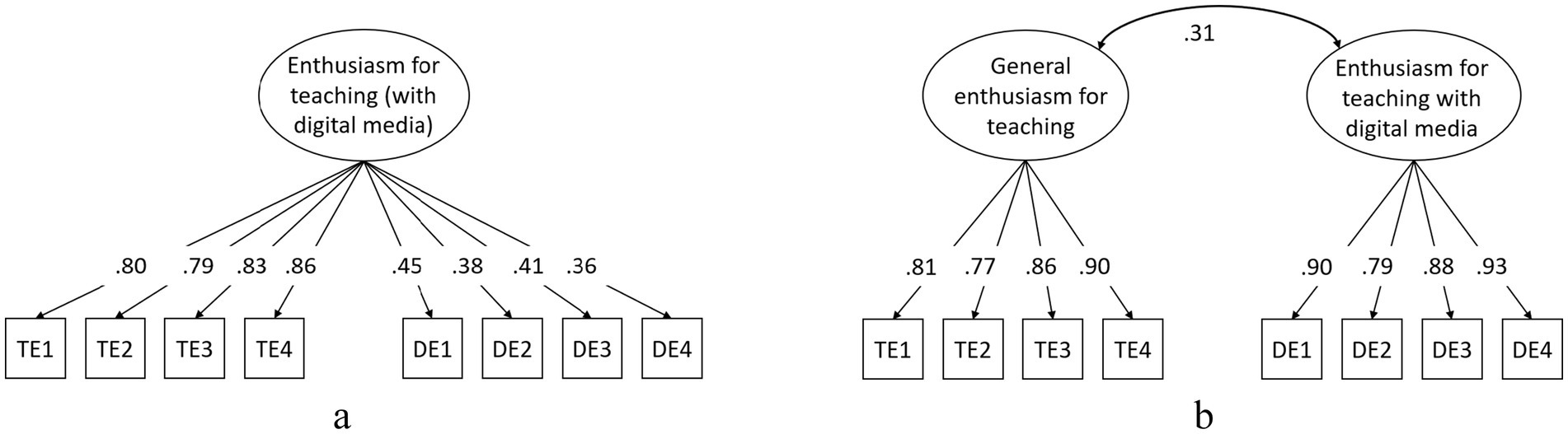

As a first step, the study thus investigates whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is a unique construct that is distinct from both general enthusiasm for teaching (H1.1) and interest in ICT (H1.2). Figure 1 shows the two corresponding models for examining the empirical distinction between teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching as an example.

Figure 1. (a) One-dimensional model. (b) Two-dimensional model. TE, General enthusiasm for teaching; DE, Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media.

The second research question focuses on exploring the extent to which the motivational factors explain the variability in enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. If enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is distinct from general enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT, multiple regression analysis will be conducted, including the following possible predictors: general enthusiasm for teaching, interest in ICT, perceived utility value of digital media, teachers’ self-efficacy, self-efficacy regarding media use, and self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching. According to expectancy-value theory, the variability in enthusiasm for teaching with digital media may be best explained when intrinsic value and (at least) one of the self-efficacy-related constructs are included in regression models simultaneously. Nonetheless, there has been only limited research using setups where different motivational factors are conjoint in regression models, and this restricts our ability to draw valid inferences or hypotheses due to the lack of available knowledge. Therefore, an exploratory approach is used in order to gain insight into the most important variables.

To answer the research questions, a cross-sectional online study was conducted with students of a German university.

5 Materials and methods

5.1 Procedures and participants

This study draws on data from a larger research project on digitalization in teacher education. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty 2 of the TU Braunschweig (identification number D_2021-09). Participants were recruited from various teacher education programs, including lectures and seminars that covered topics such as an introduction to teaching and learning, the opportunities and challenges of digital teaching, and others. The participants voluntarily took part in assessments of their digital teaching skills which lasted up to 50 min. They were compensated with €10 for their participation. All participants completed the same online questionnaire without randomization of constructs. A total of 143 students participated in the study: 70.6% were female, and 77% were under 25 years old. Most were enrolled in a bachelor’s program (87.3%). The majority were student teachers (88.1%), while 11.9% were educational science students.1 Teaching experience was generally limited, as indicated by combining internship office records with semester data of the participants. At the university under investigation, the first internship for student teachers, which is primarily observational, takes place in the second semester, while the internship involving active teaching occurs at the end of the third semester. In this study, 54.8% of student teachers were in their first semester and 24.6% were at the start of their second or third, meaning that 79.4% had not yet begun a practice-oriented practicum. Similarly, 88.2% of educational science students were in their first year, with internships typically recommended after the second semester, resulting in minimal teaching experience.

5.2 Measures

Given that most student teachers only have negligible experience teaching experience (see 5.1), they were prompted during the survey to respond the teaching-related items by envisioning themselves as a future teacher (“Please think about your future teaching in a school and rate how strongly you would agree with each statement”). All sample items in this section are translated by the authors.

Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media was assessed using an adapted version of the enthusiasm for teaching scale by Kunter et al. (2019); 4 items; sample item: “I teach with great enthusiasm using digital media.” The scale achieved good internal consistency (McDonald’s Ω = 0.92).

The intrinsic value of teaching is operationalized in the construct enthusiasm for teaching was assessed using the scale by Kunter et al. (2019); 4 items; sample item: “I teach with great enthusiasm.” The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.89).

The intrinsic value of digital media is operationalized in the construct interest in ICT was assessed using the interest in ICT scale from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2015 survey (Goldhammer et al., 2016); 6 items; sample item: “I like using digital devices.” The scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.59 across all six items). However, based on both psychometric analyses and theoretical considerations, only three items (items 2, 4 and 6) were retained for the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.71). The factor loadings of the excluded items for the latent variable interest in ICT were below the typical lower threshold of 0.4 (Guadagnoli and Velicer, 1988). Additionally, they were found to capture aspects such as flow, social media utility or internet dependence, which are conceptually distinct from the core construct of interest in ICT. Although reducing the scale limits its scope slightly, the remaining three items still provide a focused measure of students’ interest in ICT for the purposes of this study, given the aforementioned theoretical background, including interest in exploring ICT resources, discovering new digital media and general enjoyment of using digital media.

Perceived utility value of digital media was assessed using an adapted version of the scale for perceived instructional media use for individual learning (Olbrecht, 2010); 4 items; sample item: “Using digital media in teaching increases my performance.” The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.91).

Teachers’ self-efficacy was measured using the teacher self-efficacy scale by Schwarzer and Schmitz (1999); 10 items; sample item: “I am confident that I can come up with creative ideas that I can use to change unfavorable classroom structures.” The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.85).

Self-efficacy regarding media use was measured using the scale by Pumptow (2020); 7 items; sample item: “If something does not work out when using digital media, I find ways and means to make it work anyway.” This scale includes 12 items in total and has shown good internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.93).

Self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching was measured using the scale by Dinse de Salas (2019); 12 items; sample item: “I am very confident in my ability to use digital tools in the classroom.” The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (McDonald’s Ω = 0.89).

5.3 Data analysis

To test whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching are one or two distinct constructs (H1.1), a one- and a two-dimensional structural equation model were calculated. Missing data was handled using the full information maximum likelihood estimator (Arbuckle, 2013). The models are evaluated based on the common fit indices χ2 test, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Finally, both models are compared using χ2 difference tests and ΔAICc. The analyses are carried out using lavaan 0.6–11 (Rosseel, 2012) in R 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2013). The same method is used to test H1.2.

If the comparison of the structural equation models indicates the superiority of the two-dimensional models, the next step is to calculate multiple regression analysis to determine the relative importance of the predictors. The classical approach would be to use multiple regressions using the forward, backward, or stepwise method to finally select a regression model and estimate the regression parameters for this “best” model and make inferences based on this single model. However, this typical approach ignores uncertainties in the selection of a particular model as the “best” approximating model (Claeskens and Hjort, 2008). This limitation is even more strongly emphasized in studies with small sample sizes (Burnham and Anderson, 2004) and when the integrated predictors are (highly) correlated with each other (Burnham and Anderson, 2002).

To improve inference if there is uncertainty regarding model selection, the information-theoretic approach goes beyond inference based on only one single selected model to inference from the full set of models or at least many models, the so-called multimodel inference (Burnham and Anderson, 2004). For the analysis of data with small sample sizes, the corrected Akaike’s Information Criterion (AICc) is calculated for each model. AICcs are not interpretable in themselves. What can be interpreted are the distances of each model from the best model—the ΔAICc values—with smaller values indicating a higher probability of being selected as the best model across different data sets. In order to more accurately interpret this relative probability of a model, given the data and the full range of models under consideration, Akaike weights (AICcWt) are calculated, adding up to 1.0 (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). Instead of selecting the model with the highest AICc, multimodel inference attempts to make an inductive inference by including all (or at least many) a priori models with various approaches. Model averaging is an approach employed to quantify the relative importance of variables considered across all the models, if the predictors are highly correlated with each other. Model averaging assigns Akaike weights to candidate models, reducing variance for predictors with weak effects (Burnham and Anderson, 2002; Claeskens and Hjort, 2008). It addresses multicollinearity by considering different models with different combinations of variables, thereby reducing uncertainty in model selection in regression models.

For this purpose, all (multiple) linear regression models with all possible combinations of predictors are considered and parameters for each of these models are estimated, because all factors considered may influence enthusiasm for teaching with digital media based on empirical and theoretical foundations. The corrected AICc and the Akaike weights (AICcWt) are then calculated for each model. To evaluate the importance of the individual predictors considered, the b-weight of each predictor in each model is multiplied by the Akaike weights (AICcWt) of the model, and the sum of these products is denoted as ω+ (j). The relative importance of a variable j is reflected in this sum ω+ (j). The larger the ω+ (j), the more important j is, relative to the other variables considered. Using the ω+ (j), all variables can be ranked according to their importance “within the context of the set of models and predictors used” (Burnham and Anderson, 2002, p. 345). Some of the poorest models are thus not excluded in the averaging, but receive virtually no weights (Anderson, 2008). The direction and the magnitude of the averaged regression coefficients, can be interpreted as the coefficients within a (linear) multiple regression analysis. Since all possible models and the uncertainty in the model selection are taken into account, these averaged b-weights are much more likely to be replicated than the b-weights of individual models (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). Analyses are carried out using the package AICcmodavg (Mazerolle, 2023) in R 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2013).

6 Results

6.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, internal consistencies, and intercorrelations of the scales. With values ranging from McDonald’s Ω = 0.71 to 0.93, the internal consistencies were good to very good. A more comprehensive overview of the quality of the measurements with regard to the CFA results, including both model fit indices and standardized factor loadings for all items, can be found in Table 1 and Table 2 of the Supplementary material. A first look at the bivariate correlations, enthusiasm for teaching with digital media correlated moderately to strongly with all considered predictors ranged from 0.33 to 0.61. The highest correlation was observed between enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and the value-related constructs: interest in ICT and perceived utility value. Two cross-context correlations, namely between general enthusiasm for teaching and perceived utility of digital media, and between teachers’ self-efficacy and perceived utility of digital media, were not significant, underscoring the contextual relevance of teaching with digital media. The Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) for all predictors ranged from 1.6 to 2.6, well below the commonly recommended threshold of 5, indicating no evidence of serious multicollinearity (O’brien, 2007). Those who consider themselves enthusiastic for teaching do not necessarily highlight the instructional potential of digital media. In contrast, those who showed high enthusiasm for teaching with digital media clearly recognized its benefits. It has to be mentioned that the enthusiasm for teaching with digital media had only a moderately strong correlation with (general) enthusiasm for teaching, which indicated a tendency for a two-dimensional model for the teaching-related enthusiasm (s. 6.2). Furthermore, general enthusiasm for teaching showed only low to moderate correlations with the other constructs, except for its strong correlation with teachers’ self-efficacy, indicating a substantial positive association in this context. The correlation between self-efficacy regarding media use and self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching was also strong, suggesting that these two expectancies are closely related and likely perceived as overlapping aspects of self-efficacy in digital teaching by students in teaching professions.

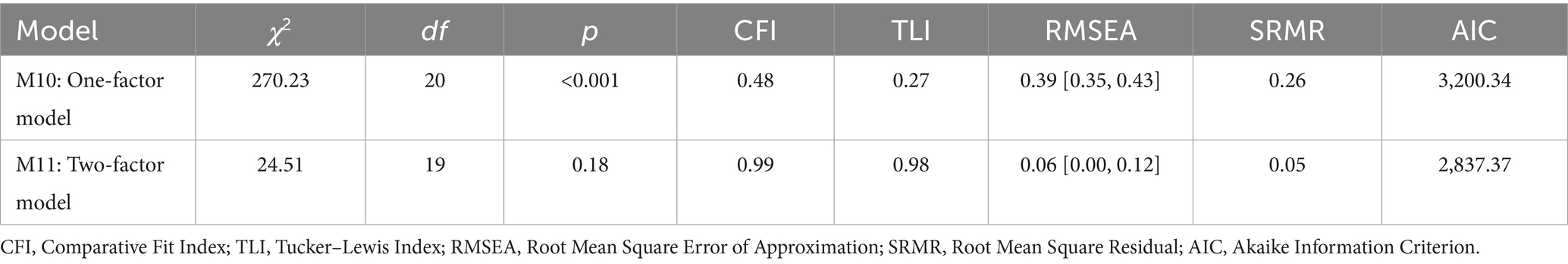

Table 2. Models testing the relationship between enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and enthusiasm for teaching.

6.2 Structural equation models regarding enthusiasm for teaching with digital media

To examine whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching are identical or distinct constructs, structural equation models were computed. Figure 2 shows the results of the estimation of the one-dimensional model and the two-dimensional model.

Figure 2. (a) Results for the one-dimensional model. (b) Results for the two-dimensional model. TE, General enthusiasm for teaching; DE, Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media.

The fit indices indicate a very bad fit for the one-dimensional model and an acceptable fit for the two-dimensional model (Table 2). Only the RMSEA of the two-dimensional model is above the common thresholds (Schumacker and Lomax, 2010), which is common for models with small degrees of freedom (Kenny et al., 2015) and small sample sizes (Chen et al., 2008). Accordingly, the fit of the two-dimensional model is significantly better than that of the one-dimensional model (Δχ2 (Δdf = 1) = 200.34, p < 0.001). Following the rough rules of thumb within the information-theoretic approach, the ΔAIC (412.98) indicates that the two-dimensional model provides essentially stronger evidence for being selected as the best approximating model.

The results thus indicate that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching are two distinct, albeit (moderate) correlated constructs (r = 0.31).

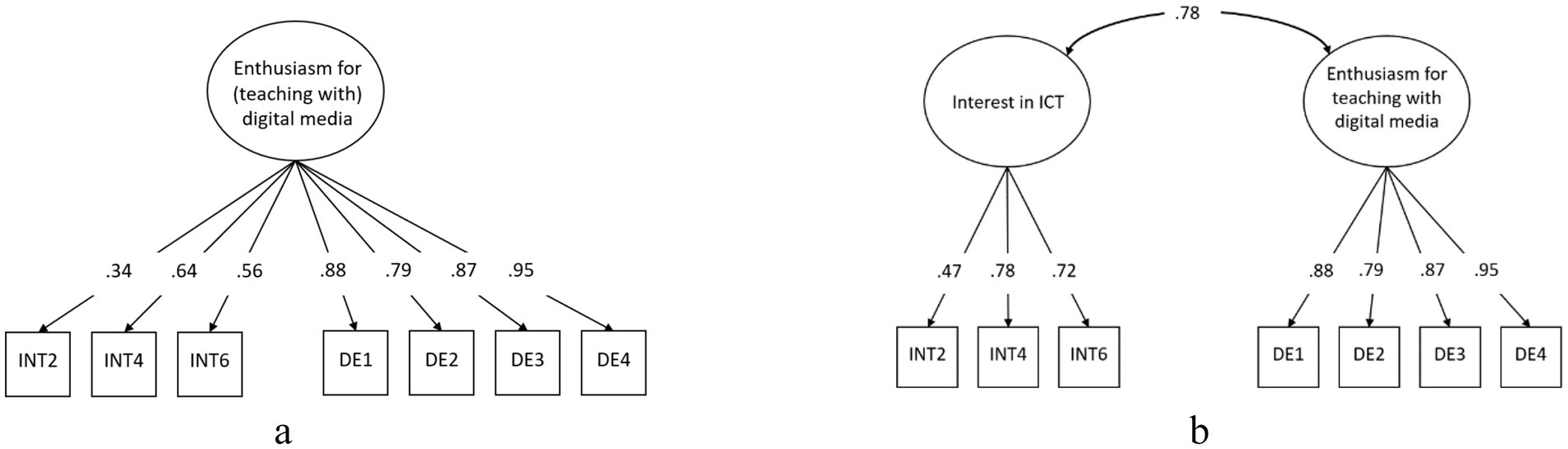

To examine whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and interest in ICT are identical or distinct constructs, structural equation models were computed. Figure 3 shows the results of the estimation of the one-dimensional model and the two-dimensional model.

Figure 3. (a) Results for the one-dimensional model. (b) Results for the two-dimensional model. INT, Interest in ICT; DE, Enthusiasm for teaching with digital media.

The fit indices indicate acceptable to good fit for both models (Table 3). However, the fit of the two-dimensional model is significantly better than that of the one-dimensional model (Δχ2 (Δdf = 1) = 10.25, p = 0.001). The ΔAIC (14.34) also indicates that the two-dimensional model provides stronger evidence for being selected as the best approximating model.

Table 3. Models testing the relationship between enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and interest in ICT.

The results therefore suggest that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and interest in ICT are two distinct, albeit highly correlated constructs (r = 0.78). It is noteworthy that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media has a higher correlation with interest in ICT than with general enthusiasm for teaching.

6.3 Relative importance of teachers’ motivational characteristics

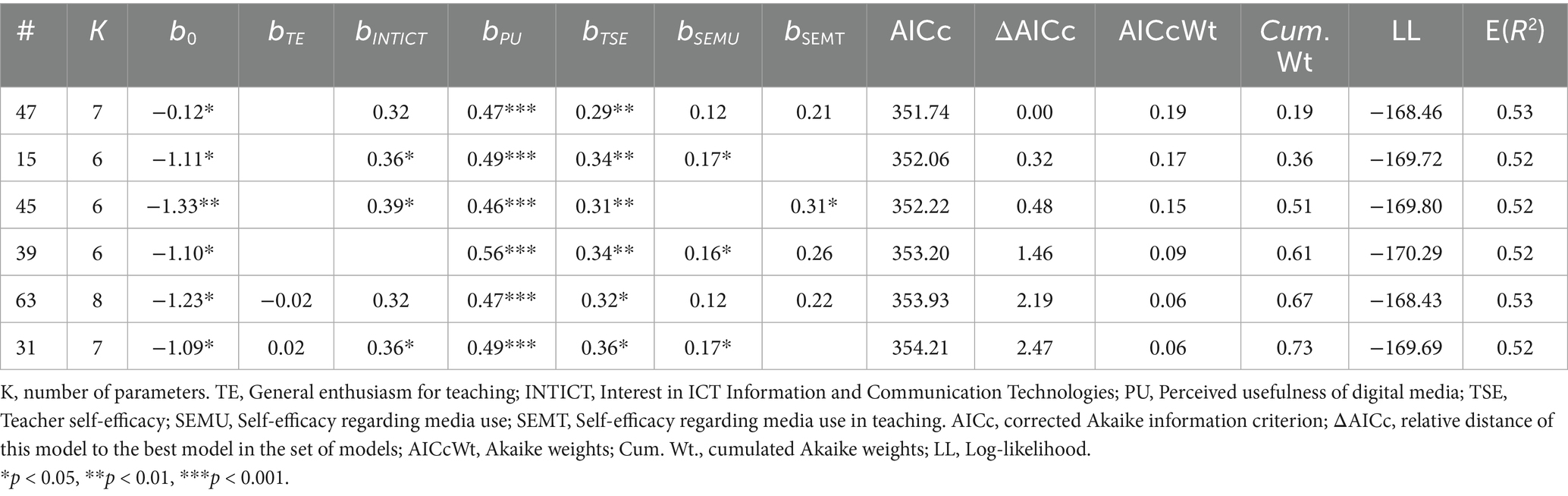

The relative importance of the predictors considered was determined using model averaging and the information-theoretic approach. Table 4 shows the estimation of the parameters of the six (multiple) linear regression models with the highest Akaike weights as examples, their AICcs, ΔAICcs, Akaike weights (AICcWts), and corrected multiple determination coefficients. The full table with all models can be found in the Supplementary material (Table 3).

Table 4. (Multiple) linear regression models predicting enthusiasm for teaching with digital media with the highest Akaike weights.

Table 5 displays the results of the model averaging approach with respect to the relative importance of the predictors considered. Based on these results, perceived utility value of digital media, interest in ICT, teachers’ self-efficacy and self-efficacy regarding media use are relevant for predicting enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. The perceived utility value of digital media emerged as the strongest predictor, with an averaged relative importance (ω+ = 0.49), indicating a moderate effect on enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. This was followed by interest in ICT (ω+ = 0.37). Expectancy-related predictors showed comparatively smaller effects, with teachers’ self-efficacy at ω+ = 0.33 and self-efficacy regarding media use at ω+ = 0.15, suggesting that perceived expectancy, particularly in media use, is less influential than value-related factors. Self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching received a relative importance score comparable to that of self-efficacy regarding media use; however, its 95% confidence interval included zero, indicating that it was not a statistically reliable predictor. Surprisingly, general enthusiasm for teaching, which is conceptually most closely related to enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, did not show a positive effect, highlighting the importance of contextual factors in shaping this form of enthusiasm.

7 Discussion

The aim of the present study was twofold. Firstly, it attempted to examine whether enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is distinct from both general enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT. The structural equation models indicate that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media and general enthusiasm for teaching are distinct, moderately correlated constructs, supporting evidence for the context specificity of enthusiasm for teaching (Kunter et al., 2011). Thus, student teachers with strong enthusiasm for teaching in general are not necessarily enthusiastic about teaching with digital media and vice versa. In addition, and in line with theoretical considerations (Schiefele et al., 2013), enthusiasm for teaching with digital media differs from interest in ICT. However, these two constructs are strongly related, suggesting that anticipated enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is more closely associated with student teachers’ media-related interests than with their intrinsic motivation related to teaching.

Secondly, the present study aimed to explore the antecedents of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. The interaction effects between expectancy and value typically require large sample sizes (e.g., N ≥ 1,000) to be reliably detected (Nagengast et al., 2011). Given the exploratory nature of the present study, the focus is placed on the main predictive effects of expectancy- and value-related factors on teaching and media use. The results indicate that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can be predicted mainly by the perceived utility of media use in teaching, interest in ICT, teachers’ self-efficacy and self-efficacy regarding media use. The powerful effect of the combination of utility value and self-efficacy on enthusiasm for teaching with digital media strongly aligns with situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020), which posits that motivation to engage in an activity is shaped by one’s perceptions of its value and the probability of success. Notably, across the top six models, perceived utility of digital media and general teachers’ self-efficacy consistently emerge as the strongest predictors. When extending this perspective to the top 11 models—whose cumulative weight totaled 0.90—this pattern remained stable, indicating a 90% probability that the combination of perceived utility and teachers’ self-efficacy would be replicated in another study (see Table 3 in Supplementary material). Interestingly, these two variables are not significantly correlated with each other. This suggests that student teachers’ enthusiasm for integrating digital media into teaching largely depends on their confidence in managing teaching tasks as well as their perception of the usefulness of digital media (and also their interest in ICT). Having an interest in innovative media or an awareness of the educational potential of digital media but lacking general teaching competence; or being highly efficacious at teaching but lacking perception and interest in digital media, makes it difficult to develop high (prospective) enthusiasm for teaching with digital media (see Table 3 in Supplementary material).

Moreover, the value-related predictors—such as perceived utility and interest—demonstrated greater importance than expectancy-related predictors, highlighting that values play a more critical role than expectancy in fostering enthusiasm. Surprisingly, the perceived utility of digital media, which exemplifies more “extrinsic” reasons for engaging in teaching with digital media, has far more predictive power than the other, more intrinsic, motivational variables considered. It supports the assumption that the internalization process of extrinsic motivation through identification even integration of utility value to the self, share some qualities of intrinsic motivation characterized by positive affect (Ryan and Deci, 2018). This finding indicates that student teachers are more likely to teach enthusiastically with digital media and to experience enjoyment and excitement during digital teaching if they are aware of the potential of digital media for teaching (Hecht et al., 2021). This finding hints at the conclusion that enthusiasm is not necessarily synonymous with intrinsic motivation, even though they both involve anticipated positive emotions when engaging in an activity (Kunter et al., 2008). Further studies should link this enthusiasm scale with existing intrinsic motivation measures regarding teaching with digital media, especially with in-service teachers. In addition, the level of interest in ICT has a stronger influence on enthusiasm for teaching with digital media than general enthusiasm for teaching in different regression models. Student teachers who are more interested in ICT are more likely to be more enthusiastic about using digital media in their teaching than student teachers who are simply excited about teaching. The finding that general enthusiasm for teaching is not a significant predictor—and appears to play a minimal role—in explaining student teachers’ enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is somewhat unexpected. This suggests that media-related values may hold greater importance in shaping enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. Furthermore, enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is seen to be more context-dependent than expected, suggesting that it may develop somewhat independently from general enthusiasm for teaching. From the perspective of the I/E model, this finding indicates that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media may result from dimensional comparison processes within the teaching activity. This leads to a more specific and contextualized form of enthusiasm, rather than a direct transfer of general enthusiasm for teaching (Möller et al., 2016). Another possible explanation for non-significant effects of general enthusiasm for teaching is restricted range. The average score for general enthusiasm for teaching was high (M = 5.01, SD = 1.04) out of a possible six, suggesting that most participants reported very high levels of general enthusiasm for teaching. This ceiling effect probably reduced the variance, and consequently its predictive power.

Furthermore, the analysis indicates that teachers’ self-efficacy has a stronger influence compared to self-efficacy regarding media use, contrary to previous suggestions about the context specificity of the measurement of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). This highlights that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is still rooted in teaching identity. Student teachers who have strong beliefs about their general teaching competence are more likely to approach new digital media with enthusiasm. Their confidence in their teaching abilities enables them to transfer this to new or specific contexts, such as the effective integration of digital media, even if they are not experts in this area (Bock et al., 2021; Möller, 2024). In contrast, self-efficacy regarding media use may be perceived as a skill and be less connected to identity as a teacher (or future teacher). Surprisingly, self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching—which offers the most context-specific alignment with the activity of teaching with digital media—did not emerge as a significant predictor. One possible explanation could be that self-efficacy regarding media use is a prerequisite for self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching. This notion is supported by the strong correlation between the two constructs. Self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching does not seem to make any additional contribution to the variance explained, especially when general self-efficacy and media-related self-efficacy are simultaneously included in the model. This implies that self-efficacy regarding media use already covers (almost) all the relevant aspects of the expectancy beliefs regarding the use of digital media for teaching for student teachers. Moreover, with regard to all possible models (see Table 3 in Supplementary material), self-efficacy regarding media use in teaching shows significant b-weights primarily in those models where general media-related self-efficacy is not included. This may also be explained by the lack of practical teaching experience (with digital media) among student teachers, based on the assumption that self-efficacy is most effectively measured by mastery of one’s own experience (Bandura, 1997). In-service teachers may assess their self-efficacy regarding media use and regarding media use in teaching differently from student teachers, which is likely to influence the relative importance of the two factors. However, this needs to be corroborated in future studies.

7.1 Limitations and future research

The results of the current study have a number of limitations. First, this study relies on cross-sectional data, which limits causal interpretations. It is likely that student teachers’ enthusiasm, interest in ICT, perceived utility of digital media, and self-efficacy reciprocally influence one another. The (expected) enjoyment experienced in teaching with digital media might also be a factor that favors self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). Therefore, longitudinal and experimental studies examining the impact of perceived utility and self-efficacy on enthusiasm for teaching with digital media are desirable.

Another limitation is the sample of the study. Due to the small sample size, the results can be generalized only to limited extent to other contexts. Moreover, the prospective assessments of the teaching-related motivational constructs present challenges with regard to response bias, as enthusiasm is one of the most desirable occupation-related characteristics (Keller et al., 2013). It is therefore questionable whether the results of the study can be generalized for in-service teachers. In addition, when employing self-reports for prospective assessment within a single session, the observed correlations tend to be overestimated, primarily as a result of common rater effects (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To reduce such risks, future studies could measure the variables in different sessions or contexts. A further limitation of this study concerns the heterogeneous sample, which included both student teachers and students of educational science. Future research should employ larger and more balanced samples to test the generalizability of the findings and it would be highly interesting to examine whether the structural relations among motivational constructs differ between those preparing directly for teaching careers and those pursuing broader educational pathways. Finally, the sample was skewed toward participants with high level of general enthusiasm for teaching, implying that those with lower level of enthusiasm are underrepresented. This is reasonable given the voluntary nature of the study, which probably resulted in students with higher enthusiasm being more likely to participate. The high ratings of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media may also be attributed to the fact that the students were at the beginning of their teaching program at university. However, this may change over time as they gain more practical experience and become more concerned about dynamics in real teaching settings, or social and political conditions in schools. Therefore, future studies should aim to recruit a more heterogeneous group of participants from different stages of teacher education, including those with more practical experience, as well as from different program types and institutions. Combining pre-service and in-service teachers would also help to capture a broader range of motivational profiles.

This study examined six predictors of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. However, as Burnham and Anderson (2002) point out, the relative importance of a single predictor can change substantially when other predictors are considered simultaneously due to the correlation among the predictors. Furthermore, beyond individual motivational factors, enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can also be shaped by technology-related perceptions described in models such as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT; Wang et al., 2022; Wijaya et al., 2025) and the Task–Technology Fit (TTF; Wang et al., 2022) framework. From this perspective, enthusiasm may emerge when teachers perceive digital media as useful and easy to integrate (performance and effort expectancy), and when the use of digital media align well with didactic learning activities. These contextual and cognitive appraisals may therefore also predict enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. Therefore, further studies could use interviews to examine key characteristics of enthusiastic teachers, or conduct experiments to explore how enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can be promoted by increasing teachers’ perception of the utility of digital media and self-efficacy, or consider other predictors using different theoretical frameworks. Follow-up studies could then reexamine and clarify the relative importance of the predictors. However, the question of which additional predictors might be causally relevant is open for discussion.

7.2 Practical implications

Having enthusiasm for teaching does not automatically mean having enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. The present findings extend existing frameworks for teacher enthusiasm by introducing enthusiasm for teaching with digital media as a context-specific construct. While previous studies have focused on general enthusiasm for teaching, this research emphasizes the importance of digital contexts and identifies value- and efficacy-related factors that influence enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. These insights highlight the need to conceptualize and support enthusiasm in a more context-sensitive manner within teacher education frameworks.

Our study addressed student teachers and revealed several factors that could help to maintain or boost enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, which is regarded as an important feature in the teaching profession. While this introductory study does not provide direct empirical evidence of the effects of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media on teaching quality or student outcomes, this remains an important area for future research. However, given previous findings on the positive effects of general teaching enthusiasm (Kunter et al., 2013; Praetorius et al., 2017), it is reasonable to assume that this construct is relevant in the context of teacher education programs (Wang et al., 2022). If the results of the present study are substantiated by further studies, student teacher programs that aim to foster teachers’ value perceptions (especially regarding digital media) and self-efficacy in using digital media could play an important role in shaping enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. Policy frameworks have emphasized the integration of digital media training within teacher education, supporting broader digitalization efforts at universities with a particular focus on teaching-related disciplines. Teacher training projects must be dynamic and adaptable in order to keep up with rapidly developing technologies. Such initiatives could encourage future teachers to view digital media, including AI-powered tools, as personally meaningful and pedagogically valuable. This issue should be addressed more intensively in continuing education courses, which should also target in-service teachers (cf. Drossel et al., 2024). This is particularly important for those who have already established stable teaching routines that do not involve digital media. Furthermore, student teacher programs should emphasize the benefits of digital media for teaching as well as foster teaching- and media-related self-efficacy to promote enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. To this end, it seems advisable to offer media-related and competence-oriented programs, to create opportunities to use digital media in university courses, and to provide positive verbal feedback regarding media use (cf. Bandura, 1997). This process should be facilitated by emphasizing the utility value of digital media, which is an inspiring message for educators. To foster enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, student teachers need to know about the benefits of digital media and enjoy the process of using them. Our research also suggests that diverse practical phases should be included in student teacher programs. They should also be encouraged to believe in their teaching abilities and their ability to use digital media, which is nowadays considered an integral part of the teaching profession. As demonstrated by the significant role of interest in digital media as a predictor of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media, it can be assumed that experiencing positive emotions when using innovative technologies and developing situational interest in digital media are crucial components of acquiring and developing enthusiasm for teaching with digital media. Accordingly, teacher education programs should create opportunities for student teachers to engage with digital media in emotionally positive and pedagogically meaningful ways. This could be achieved through hands-on experimentation, creative lesson design and reflection on successful and unsuccessful digital learning experiences. Such experiences can help future teachers to become competent and develop a sustained enthusiasm for integrating digital media into their teaching practice.

7.3 Conclusion

In summary, the main take-away of the present study is that enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is distinct from both general enthusiasm for teaching and interest in ICT. Furthermore, enthusiasm for teaching with digital media can be predicted primarily by the perceived utility value of digital media for teaching, interest in ICT, teachers’ self-efficacy and self-efficacy regarding media use. We can therefore look enthusiastically toward future research on enthusiasm for teaching in general and for the use of digital media in teaching, which should deepen our understanding of the sources of enthusiasm for teaching.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Faculty 2 of the TU Braunschweig. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LX: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. MF: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. LS: Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted within the project Digitale Kompetenzen in der Lehrerbildung Braunschweig [Digital competencies in teacher training Braunschweig] (DiBS), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMBF) as part of the Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung III, grant number 01JA2028. The author(s) acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of Technische Universität Braunschweig.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1668870/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1 ^Students of educational science were included, since many of them receive training or develop their identities in areas such as adult and further education, instructional design and educational institutions. They were recruited from the mandatory lecture “Introduction to Teaching and Learning” and, like most student-teacher participants, had negligible experience of teaching with digital media prior to the study. Subgroup analyses were conducted prior to pooling, but only limited checks could be performed due to the small number of educational science students. A two-sided t-test showed no statistically significant difference in enthusiasm for teaching with digital media between the two groups (student teachers and educational science students) (t(141) = −1.40, Cohen’sd = 0.36,p = 0.16). The same applies to the other variables, except general enthusiasm for teaching (t(141) = −2.31, Cohen’sd = 0.60,p = 0.02). This pattern is theoretically reasonable, as student teachers typically identify more strongly with the teaching profession. However, both groups have comparable experience with digital media and limited teaching practice. Consequently, including educational science students in the analysis of enthusiasm for teaching with digital media is unlikely to introduce bias and broadens the sample of future educational professionals.

References

Anderson, D. R. (2008). Model based inference in the life sciences: a primer on evidence. New York: Springer.

Andersson, S. B. (2006). Newly qualified teachers’ learning related to their use of information and communication technology: a Swedish perspective. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 37, 665–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00563.x

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In Advanced structural equation modeling. eds. Marcoulides, G. A, and Schumacker, R. E (New York: Psychology Press), 243–277.

Backfisch, I., Lachner, A., Hische, C., Loose, F., and Scheiter, K. (2020). Professional knowledge or motivation? Investigating the role of teachers’ expertise on the quality of technology-enhanced lesson plans. Learn. Instr. 66:101300. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101300

Baier, F., Decker, A. T., Voss, T., Kleickmann, T., Klusmann, U., and Kunter, M. (2019). What makes a good teacher? The relative importance of mathematics teachers’ cognitive ability, personality, knowledge, beliefs, and motivation for instructional quality. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 767–786. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12256,

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften [keyword: professional competence of teachers]. Z. Erziehungswiss. 9, 469–520. doi: 10.1007/s11618-006-0165-2

Beardsley, M., Albó, L., Aragón, P., and Hernández-Leo, D. (2021). Emergency education effects on teacher abilities and motivation to use digital technologies. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 1455–1477. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13101

Bleck, V. (2019). Lehrerenthusiasmus [teacher enthusiasm]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Bock, D., Harms, U., and Mahler, D. (2021). Examining the dimensionality of pre-service teachers’ enthusiasm for teaching by combining frameworks of educational science and organizational psychology. PLoS One 16:e0259888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259888,

Burić, I., and Moè, A. (2020). What makes teachers enthusiastic: the interplay of positive affect, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 89:103008. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.103008

Burnham, K. P., and Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference. A practical information-theoretic approach. New York: Springer.

Burnham, K. P., and Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33, 261–304. doi: 10.1177/0049124104268644

Chen, F., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J., and Paxton, P. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 36, 462–494. doi: 10.1177/0049124108314720,

Chen, X., Guo, S., Zhao, X., Fekri, N., and Azari Noughabi, M. (2024). The interplay among Chinese EFL teachers’ enthusiasm, engagement, and foreign language teaching enjoyment: a structural equation modelling approach. Asia-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 9:67. doi: 10.1186/s40862-024-00293-x

Chen, Y. C., and Hou, H. T. (2025). Design of a digital gamified learning activity for relationship education with conceptual scaffolding and reflective scaffolding. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 34, 237–251. doi: 10.1007/s40299-024-00849-y

Claeskens, G., and Hjort, N. L. (2008). Model selection and model averaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results [dissertation]. Cambridge: Sloan School of Management.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., and Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 22, 1111–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1993). Die Selbstbestimmungstheorie der motivation und ihre Bedeutung für die Pädagogik [the theory of self-determination of motivation and its relevance to educational science]. ZfPäd 39, 223–238. doi: 10.25656/01:11173

Dinse de Salas, S. (2019). Digitale Medien im Unterricht – Entwicklung professionellen Wissens und professionsbezogener Einstellungen durch coaching [digital media in the classroom - developing professional knowledge and professional attitudes through coaching] [dissertation]. Heidelberg: Pädagogische Hochschule Heidelberg.

Drossel, K., Eickelmann, B., Schaumburg, H., and Labusch, A. (2019). “Nutzung digitaler Medien und Prädiktoren aus der Perspektive der Lehrerinnen und Lehrer im internationalen Vergleich [use of digital media and its predictors from teachers' perspective in an international comparison]” in ICILS 2018 #Deutschland: Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im zweiten internationalen Vergleich und Kompetenzen im Bereich Computational Thinking. eds. B. Eickelmann, W. Bos, J. Gerick, F. Goldhammer, H. Schaumburg, and K. Schwippert, et al. (Münster: Waxmann), 205–240.

Drossel, K., Gerick, J., Niemann, B., Eickelmann, B., and Domke, M. (2024). “Die Perspektive der Lehrkräfte auf das Lehren mit digitalen Medien und die Förderung des Erwerbs computer- und informationsbezogener Kompetenzen in Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich [teachers' perspectives on teaching with digital media and promoting the acquisition of computer and information-related skills in Germany in an international comparison]” in ICILS 2023 #Deutschland: Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen und Kompetenzen im Bereich Computational Thinking von Schüler*innen im internationalen Vergleich. eds. B. Eickelmann, N. Fröhlich, W. Bos, J. Gerick, F. Goldhammer, and H. Schaumburg, et al. (Münster: Waxmann), 149–187.

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: a developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101859. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

European Commission (2020). Digital Education Action Plan 2021–2027. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/document-library-docs/deap-communication-sept2020_en.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2025)

Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., and Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: a reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 628–639. doi: 10.1037/edu0000228

Ginsberg, M. B., and Wlodkowski, R. J. (2019). Intrinsic motivation as the foundation for culturally responsive social-emotional and academic learning in teacher education. Teach. Educ. Q. 46, 53–66.

Goldhammer, F., Gniewosz, G., and Zylka, J. (2016). “ICT engagement in learning environments” in Assessing contexts of learning. eds. S. Kuger, E. Klieme, N. Jude, and D. Kaplan (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 331–354.

Guadagnoli, E., and Velicer, W. F. (1988). Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol. Bull. 103, 265–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.265,

Hecht, C. A., Grande, M. R., and Harackiewicz, J. M. (2021). The role of utility value in promoting interest development. Motiv. Sci. 7, 1–20. doi: 10.1037/mot0000182,

Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., and Kunter, M. (2013). How teachers’ self-efficacy is related to instructional quality: a longitudinal analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 774–786. doi: 10.1037/a0032198

Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., and Kunter, M. (2016). Ein Blick in die black-box: Wie der Zusammenhang von Unterrichtsenthusiasmus und Unterrichtshandeln bei angehenden Lehrkräften erklärt werden kann [a look into the black box: how to explain the relationship between teaching enthusiasm and teaching activities among teacher traintees]. Z Entw. Pädagogis. (ZEPP) 48, 90–105. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637/a000150

Hulleman, C. S., and Harackiewicz, J. M. (2009). Promoting interest and performance in high school science classes. Science 326, 1410–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.1177067,

Keller, M. M., Becker, E. S., Frenzel, A. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2018). When teacher enthusiasm is authentic or inauthentic: lesson profiles of teacher enthusiasm and relations to students’ emotions. AERA Open 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/2332858418782967

Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Becker, E. S., Morger, V., and Hensley, L. (2014). Feeling and showing: a new conceptualization of dispositional teacher enthusiasm and its relation to students' interest. Learn. Instr. 33, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.03.001

Keller, M., Neumann, K., and Fischer, H. E. (2013). “Teaching enthusiasm and student learning” in International guide to student achievement. eds. J. Hattie and E. Anderman (New York: Routledge), 247–249.

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., and McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 44, 486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236

Kouhsari, M., Huang, X., and Wang, C. (2024). The impact of school climate on teacher enthusiasm: the mediating effect of collective efficacy and teacher self-efficacy. Camb. J. Educ. 54, 143–163. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2023.2255565

Krapp, A. (2007). An educational–psychological conceptualisation of interest. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 7, 5–21. doi: 10.1007/s10775-007-9113-9

Kunter, M. (2013). “Motivation as an aspect of professional competence: research findings in teacher enthusiasm” in Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers. Results from COAKTIV project. eds. M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, and M. Neubrand (New York: Springer), 273–290.

Kunter, M., Frenzel, A., Nagy, G., Baumert, J., and Pekrun, R. (2011). Teacher enthusiasm: dimensionality and context specificity. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.07.001

Kunter, M., and Holzberger, D. (2014). “Loving teaching: research on teachers’ intrinsic orientations” in Teacher motivation: theory and practice. eds. P. W. Richardson, S. A. Karabenick, and H. M. G. Watt (New York: Routledge), 83–99.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., and Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 805–820. doi: 10.1037/a0032583

Kunter, M., Leutner, D., Seidel, T., Dicke, T., Holzberger, D., Hein, N., et al. (2019). Ertrag und Entwicklung des universitären bildungswissenschaftlichen Wissens - Validierung eines Kompetenztests für Lehramtsstudierende (BilWiss-UV) [Yield and development of educational science knowledge in higher education - validation of a competence test for student teachers (BilWiss-UV)]. Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. Available online at: https://www.fdz-bildung.de/studiendetails.php?id=439 (Accessed May 18, 2025)

Kunter, M., Tsai, Y. M., Klusmann, U., Brunner, M., Krauss, S., and Baumert, J. (2008). Students' and mathematics teachers' perceptions of teacher enthusiasm and instruction. Learn. Instr. 18, 468–482. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.008

Lazarides, R., Fauth, B., Gaspard, H., and Göllner, R. (2021). Teacher self-efficacy and enthusiasm: relations to changes in student-perceived teaching quality at the beginning of secondary education. Learn. Instr. 73:101435. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101435

Mazerolle, M. J. (2023). AICcmodavg: model selection and multimodel inference based on (Q)AIC©. Available online at: http://10.32614/CRAN.package.AICcmodavg (Accessed May 18, 2025)

Möller, J. (2024). Ten years of dimensional comparison theory: on the development of a theory from educational psychology. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36:82. doi: 10.1007/s10648-024-09918-6

Möller, J., Müller-Kalthoff, H., Helm, F., Nagy, N., and Marsh, H. W. (2016). The generalized internal/external frame of reference model: an extension to dimensional comparison theory. Frontline Learn. Res. 4, 1–11. doi: 10.14786/flr.v4i2.169

Nagengast, B., Marsh, H. W., Scalas, L. F., Xu, M. K., Hau, K. T., and Trautwein, U. (2011). Who took the “×” out of expectancy-value theory? A psychological mystery, a substantive-methodological synergy, and a cross-national generalization. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1058–1066. doi: 10.1177/0956797611415540,

O’brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41, 673–690. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

Olbrecht, T. (2010). Akzeptanz von E-Learning - Eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Technologieakzeptanzmodell zur Analyse individueller und sozialer Einflussfaktoren [Acceptance of e-learning - An examination of the Technology Acceptance Model to analyze individual and social influencing factors]. [dissertation]. Jena: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena.

Öngel, G., and Tabancali, E. (2022). Teacher enthusiasm and collaborative school climate. Educ. Q. Rev. 5, 347–356. doi: 10.31014/aior.1993.05.02.494

Özdemir, O. (2025). Kahoot! Game-based digital learning platform: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 41:e13084. doi: 10.1111/jcal.13084

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879,

Praetorius, A. K., Lauermann, F., Klassen, R. M., Dickhäuser, O., Janke, S., and Dresel, M. (2017). Longitudinal relations between teaching-related motivations and student-reported teaching quality. Teach. Teach. Educ. 65, 241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.023

Pumptow, M. I. (2020). Digital Media in Higher Education – the use and importance of digital Media in Contemporary University Studies [dissertation]. Tübingen: Universität Tübingen.

R Core Team. (2013). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Available online at: http://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed May 18, 2025)

Renninger, K. A., and Hidi, S. E. (2016). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. New York: Routledge.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford.

Schiefele, U., Streblow, L., and Retelsdorf, J. (2013). Dimensions of teacher interest and their relations to occupational well-being and instructional practices. J. Educ. Res. Online (JERO) 5, 7–37. doi: 10.25656/01:8018

Schubatzky, T., Burde, J. P., Große-Heilmann, R., Haagen-Schützenhöfer, C., Riese, J., and Weiler, D. (2023). Predicting the development of digital media PCK/TPACK: the role of PCK, motivation to use digital media, interest in and previous experience with digital media. Comput. Educ. 206:104900. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104900

Schumacker, R. E., and Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Schwarzer, R., and Jerusalem, M. (2002). “Das Konzept der Selbstwirksamkeit [the concept of self-efficacy]” in Selbstwirksamkeit und Motivationsprozesse in Bildungsinstitutionen. eds. M. Jerusalem and D. Hopf (Weinheim and Basel: Beltz), 28–53.

Schwarzer, R., and Schmitz, G. S. (1999). “Skala zur Lehrer-Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung [scale for measuring teachers' self-efficacy]” in Skalen zur Erfassung von Lehrer- und Schülermerkmalen. eds. R. Schwarzer and M. Jerusalem (Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin), 60–61.

Shao, G. (2023). A model of teacher enthusiasm, teacher self-efficacy, grit, and teacher well-being among English as a foreign language teachers. Front. Psychol. 14:1169824. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1169824,

Stieler-Hunt, C., and Jones, C. M. (2015). Educators who believe: understanding the enthusiasm of teachers who use digital games in the classroom. Res. Learn. Technol. 23:26155. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v23.26155,