- 1Department of Methods of Primary Education, Zhanibekov University, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

- 2Department of Foreign Languages for Technical Specialties, M. Auezov South Kazakhstan University, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

- 3Department of Psychological and Pedagogical Education and Teaching Methods, Korkyt Ata Kyzylorda University, Kyzylorda, Kazakhstan

- 4Department of Physics, M. Auezov South Kazakhstan University, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

Introduction: Organizing the primary education process within the framework of STEM education enhances students' scientific literacy, fosters the development of engineering skills, promotes analytical and critical thinking abilities, and increases interest in technical disciplines. This study is grounded in an integrative approach to organizing the primary education process through STEM education, focusing on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students. Based on this integrative approach, a dedicated STEM-oriented educational program was developed.

Methods: The study was conducted in three stages: diagnostic, formative, and control. A pre-test and post-test design was employed to compare the outcomes of the control and Experimental classs. The Experimental class was taught using the newly developed STEM program, while the control class followed the traditional curriculum.

Results: All data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of data distribution. The pre-test results indicated that the initial knowledge levels of the two classes were comparable. However, the post-experimental findings revealed significant changes. A statistically significant difference was identified between the performance of the control and experimental classes, with the experimental class demonstrating superior outcomes. These results provide clear evidence of the effectiveness of the interventions implemented in the Experimental class. Overall, the findings confirm the reliability and validity of the study.

Discussion: The STEM-based educational program was tested during the experiment, and its effectiveness was evaluated through a comparative analysis of pre- and post-test results. The findings provide strong evidence in support of the effectiveness of the instructional approach applied to the Experimental class.

1 Introduction

In a rapidly changing world, humanity constantly faces new challenges, and through the process of addressing them, it evolves and develops. Future professionals must be prepared to adapt swiftly to new conditions, respond to changes in the labor market, and acquire new skills that align with the fast-paced innovations in science, technology, and engineering. As noted in the Didactic Foundations for Implementing the STEM Approach in Education (Bilim berudegi STEM-tasilin iske asyrudyn didaktikalyk negizderi: adistemelik kural [Didactic foundations of implementing the STEM approach in education: methodological book], 2023), learners need to master a set of universal competencies that enable them to adapt to new realities, engage in lifelong learning, solve problems independently, and critically evaluate the outcomes of their efforts.

Achieving such educational outcomes is possible through the integration of STEM approaches in the learning process and the transition from a traditional subject-based model to a meta-subject framework centered on intellectual and cognitive activity. The novelty of this study lies in its integrative approach to organizing the primary education process through STEM education, aiming to foster the development of meta-subject skills in young learners. Although STEM education has been shown to enhance students' research and creative activity, this study specifically focused on examining its impact on the development of meta-subject skills among primary school students.

By addressing current challenges in STEM education in Kazakhstan, this research implements practice-oriented projects that promote the solving of experimental and technically focused tasks. The central aim of this study is to investigate the impact of STEM-based instruction, grounded in the theory of integrated learning, on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students. Specifically, this study seeks to explore the potential of integrating science, technology, engineering, and mathematics in primary education and its influence on students' meta-subject skill development.

Fogarty (1991) identifies ten models for integrating the learning process: Fragmented Model, Connected Model, Nested Model, Sequenced Model, Shared Model, Webbed Model, Threaded Model, Immersed Model, Integrated Model, and Networked Model. These models illustrate different forms of integration across school subjects. An integrated or interdisciplinary curriculum is considered an effective and relevant approach for teaching 21st-century competencies and for applying interdisciplinary skills essential to addressing complex global challenges. Moreover, integrated curricula have been shown to contribute to positive learning outcomes and personal development (Drake and Reid, 2020). Building on this, Kelley and Knowles (2016) propose the conceptual foundation of integrated STEM education, which involves the unification of science (S), technology (T), engineering (E), and mathematics (M). Integrating STEM disciplines provides students with opportunities to develop interdisciplinary thinking, complex problem-solving abilities, and creative skills.

Integrating STEM disciplines in the learning process enhances student motivation and creativity. However, primary schools tend to lag behind secondary and high schools in implementing STEM technologies in their curricula. This study addresses that gap by focusing on the primary education context and introducing STEM-based instructional approaches that help develop essential 21st-century skills. STEM-oriented learning environments foster critical thinking, creativity, research skills, and meta-subject skills in students.

Furthermore, the study is grounded in the theory of integrated learning, which emphasizes students' ability to develop holistic knowledge by applying both interdisciplinary and intradisciplinary connections. STEM represents an integrated learning approach that promotes a holistic understanding of the world, facilitates the completion of engineering tasks, problem-solving, and engagement in research activities. This study is also informed by the theories of problem-based and project-based learning, highlighting the importance of fostering students' creative abilities through various technological styles by combining science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

In this context, STEM serves as a tool for developing meta-subject skills in primary school students while also enhancing their critical and creative thinking. The study contributes to the field of education by demonstrating how a STEM-based program can be effectively implemented to foster meta-subject skills among young learners.

Although the number of studies highlighting the benefits of STEM education is growing, this research fills an important gap by focusing specifically on the organization of STEM instruction in the context of primary education and its impact on meta-subject skill development. The findings offer valuable insights into how interdisciplinary topics, research activities, and STEM projects can be designed and implemented. Additionally, the study advances understanding of the role of STEM technologies in education and the broader implications for teaching primary school subjects from a meta-subject perspective. It also proposes new strategies for fostering 21st-century competencies.

Thus, the research objective is to investigate the impact of STEM-based instruction on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students. Based on it, the following research question guides the study:

(1) What is the impact of STEM-based instruction on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students?

2 Literature review

2.1 STEM education in Kazakhstan

STEM education is rapidly developing as one of the key global educational trends and is increasingly being integrated into mainstream educational systems (Abylkassymova et al., 2024). In Kazakhstan, focused attention on STEM began around 2017, as part of initiatives to implement new innovation-driven projects based on science and technology. These efforts aimed to adopt international best practices, prepare Kazakhstani students for technological innovation, bridge the gap between education and future careers, and stimulate interest in technical disciplines.

Currently, Kazakhstan is witnessing the establishment of STEM centers, the opening of specialized STEM classrooms, the development of STEM-oriented curricula, and the hosting of international conferences on STEM education. In 2023, the Ministry of Education of Kazakhstan introduced the “Concept of STEM Education” (STEM - bilim beru tuzhyrymdamasy [The concept of STEM education], 2023) as part of a national strategy to modernize and improve the education system. This concept emphasized the need to incorporate STEM education across all levels of schooling, from early childhood education to primary and secondary levels.

Kazakhstan has achieved notable progress in applying STEM technologies in disciplines such as robotics (Karataev et al., 2024), physics (Zhandarbayeva et al., 2025), engineering, and computer science (Ramankulov and Gench, 2025). Educational institutions such as STEM Academia, STEM Inventor, and Quantum-STEM were established to support the advancement of STEM education. These initiatives reflect Kazakhstan's growing commitment to equipping students with scientific knowledge (Abdrakhmanova and Kudaibergenova, 2023), competencies in engineering and technological fields (Baiganova and Nauryzova, 2024), analytical skills (Maratova et al., 2023), and critical thinking abilities (Iskakova et al., 2023).

As a result, the popularity and implementation of STEM education in Kazakhstan are expanding rapidly, not only in schools (Kadirbaeva and Zhitabay, 2025; Ospanbekova et al., 2024) but also across higher education institutions (Mukhamediyeva et al., 2023).

STEM education is a comprehensive approach that emphasizes teamwork, project-based learning, the use of modern technological tools, and the integration of multiple disciplines. It supports creativity, problem-solving, and innovation through interdisciplinary teaching and progressive instructional strategies (STEM - tekhnologiya negizinde orta bilim beru mazmunyn kajta kurylymdau [Restructuring the content of secondary education based on STEM technology], 2022).

2.2 Integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (integrated STEM education)

Various definitions of integrated STEM education have been proposed in academic literature and methodological guidelines. For example, Satylmysh et al. (2025) define integrated STEM education as a pedagogical approach that promotes students' holistic and meaningful understanding of the four components—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—through project-based, problem-based, and experiential learning. More specifically, integrated STEM education is viewed as an interdisciplinary instructional approach that merges the four domains of STEM to support cross-curricular learning (Havice et al., 2018). According to Thibaut et al. (2018), integrated STEM represents a novel educational strategy that fosters student interest across all STEM disciplines. English (2016) also highlights that integration in STEM education is achieved through interdisciplinary, inquiry-based methods.

A common theme across these definitions is the unified treatment of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as interconnected disciplines. However, Sun et al. (2025) point out that engineering remains the least integrated component among the four fields. Nevertheless, considering the growing importance of engineering in interdisciplinary STEM projects, it is essential to implement STEM instruction within an engineering context. Sanders (2009) described integrated STEM as “approaches that explore teaching and learning between/among any two or more of the STEM subject areas, and/or between a STEM subject and one or more other school subjects.”

In this regard, Martín-Páez et al. (2019) draw several important conclusions from their analysis of STEM education initiatives. First, the use of STEM terminology appears to play only a minor role at the theoretical level. Second, STEM education is often employed merely to describe learning outcomes in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Third, in many STEM programs, the connections between disciplines are not explicitly articulated. Fourth, students' cognitive and practical engagement, together with their intrinsic motivation, significantly enhances their interest in STEM subjects. Fifth, the design of STEM programs should be guided by the fundamental questions of where, how, for whom, and under what conditions they are implemented. Accordingly, the authors argue that STEM education should be understood as “an instructional approach that integrates the content and skills characteristic of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics” (Martín-Páez et al., 2019).

Scholarly research on integrated STEM education emphasizes several key dimensions:

A focus on problem-based and project-based learning (Alfer'yeva-Termsikos, 2025; Baiganova and Nauryzova, 2024; Reutskaya, 2021). In problem-based and project-based learning, students engage in addressing real-world problems.

The development of critical thinking, problem-solving, creative thinking, and research skills (Dosymov et al., 2025; Buzni and Osipenko, 2025; Kudaibergenova et al., 2022).

The impact of integrated STEM education on cognitive skills, as noted by Chen B. et al. (2025). Within the framework of STEM education, students acquire knowledge and learn to apply it in practice. When confronted with real-life challenges, they strive to solve complex problems by drawing on knowledge from multiple domains. In this context, reliance on a single disciplinary perspective is insufficient for effective problem-solving.

Nishanbayeva et al. (2021) argue that STEM education is especially effective for enhancing communication skills and fostering a more applied understanding of abstract academic content in primary school students.

The integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics is increasingly reflected in the content and curricula of primary education, including textbooks and teaching materials. For instance, integration in STEAM education has been extensively examined, with mathematics content being linked to topics from science, Russian language, native language, English, technology, and even historical knowledge (Tulentayeva et al., 2023). According to Karataev et al. (2024), developing conceptual understanding in these subjects during the early grades fosters interdisciplinary thinking in students.

Moreover, STEM-integrated lessons deepen students' understanding of STEM concepts and provide insights into the successes and challenges of integrated instruction (Menon et al., 2025). Despite these advances, researchers in the field of education have reported that teachers often face difficulties in establishing meaningful connections among STEM disciplines (Kelley and Knowles, 2016).

This challenge underscores the relevance and significance of the present study, which seeks to explore and address the complexities of implementing integrated STEM education, particularly at the primary level.

2.3 Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST)

To assess students' perceptions of scientists in the context of STEM education, the Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST) was employed (Luo and So, 2023). The instrument was originally developed by Chambers (1983), and it has since been widely applied in numerous studies (Fung, 2002; Ferguson and Lezotte, 2020; Medina-Jerez et al., 2011).

In analyzing students' drawings, researchers typically focus on indicators such as laboratory coats, glasses, scientific instruments, and the overall depiction of the scientist's appearance. These visual representations provide insight into how students conceptualize scientists (Farland-Smith, 2012). Findings from multiple studies indicate that students often portray scientists as male figures who spend their lives in laboratories conducting dangerous experiments. Research also shows that elementary students' stereotypes are more often associated with the scientist's work than with physical appearance. Importantly, such stereotypes influence students' attitudes toward science (Losh et al., 2008) and may later affect their career choices (Farland-Smith et al., 2014).

Therefore, educators are encouraged to use science education as a means to cultivate more accurate and authentic understandings of scientists and their work (Emvalotis and Koutsianou, 2018). As noted by Bartels and Lederman (2022), scientific literacy is the primary goal of early science education. Teachers of science thus play a critical role in challenging stereotypical perceptions (Finson, 2002). Furthermore, (Farland-Smith 2009) demonstrated that students' ideas of who scientists are, where they work, and what they do are shaped by cultural experiences.

Against this backdrop, the present study draws on insights from DAST research by employing drawing-based procedures to explore students' perceptions of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

2.4 Meta-subject skills

In the Kazakhstani education system, the scientific theory of meta-subject education is still in its formative stages. Notably, the term “meta-subject” has yet to be included in Kazakh explanatory dictionaries, which reflects its novelty within the national pedagogical discourse. The core concept of this study—meta-subject—is relatively new in Kazakhstani pedagogical science and is only beginning to be explored.

One of the first researchers to address the issue of meta-subject instruction in primary education in Kazakhstan was Zhumabayeva et al. (2021). Subsequent studies have examined related aspects: Turysbayeva and Turalbayeva (2024) explored the use of formative assessment to support the development of meta-subject outcomes in primary school students; Ospanbekova et al. (2024) investigated the pedagogical conditions necessary for implementing meta-subject instruction in primary education; and Zhussip et al. (2025) proposed a functional model for developing universal learning activities in young learners.

Two of the most influential scholarly traditions in the theoretical and practical development of the concept of “meta-subject” are the research schools by Gromyko and Khutorskoy, who are considered pioneers in the field. According to Khutorskoy (2012), the meta-subject approach is “not only an activity-based dimension of a subject but also a foundational element of the subject itself.” Gromyko (2004) defines the foundation of meta-subject as “the integration and unification of parts into a unique and holistic system.”

Meta-subject skills refer to a set of actions that enable learners to acquire new knowledge independently, develop skills and abilities, and manage their learning processes (Asmolov et al., 2014). The concept of meta-subject is viewed as a universal attribute of educational systems, supporting the integration of scientific knowledge and the formation of a holistic worldview (Saudabayeva and Sholpankulova, 2020). Meta-subject skills allow primary school students to perceive the world as an integrated whole.

In this context, the development of assessment tools for diagnosing meta-subject outcomes through the integration of multiple school subjects is seen as a promising direction (Aytbaev et al., 2023). However, a review of domestic research reveals a significant gap in the study of how meta-subject skills can be developed in primary school students within the context of STEM education.

Therefore, the current study aims to examine the effect of STEM-based instruction on developing meta-subject skills in primary school students by structuring the learning process around integrated, interdisciplinary methods.

Moreover, research has shown that meta-disciplinary skills are often referred to as non-cognitive skills. Recent studies increasingly highlight the critical role of non-cognitive skills as a key determinant of academic success in STEM education. For instance, Sultanova and Shora (2024) demonstrate the significant influence of non-cognitive skills on students' performance in secondary school STEM subjects. Non-cognitive skills encompass a wide range of attributes that substantially contribute to achievement in STEM domains (Han et al., 2020). These skills enable students to solve problems, grasp complex concepts, and sustain focus when completing tasks.

Effective collaboration, in particular, transforms teamwork into a non-cognitive skill that supports the implementation of scientific research and engineering projects. In this regard, cooperative interaction becomes essential for advancing knowledge, while well-executed STEM education fosters students' critical thinking, pedagogical skills, and practical experiences (Upadhyay et al., 2021a). As noted by Upadhyay et al. (2021b), “STEAM education provides learners with opportunities to interpret and make sense of the world in broader ways than simply engaging in project-based tasks or studying natural sciences.”

Schiepe-Tiska et al. (2021) integrate both cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes under the concept of multidimensional educational goals, emphasizing their importance in STEM learning. At this developmental stage, students refine their self-concepts and clarify their relationships with peers and the wider world, marking a decisive phase in personal development. Similarly, Dweck et al. (2014) associate non-cognitive skills with academic perseverance, characterized by: (1) a sense of academic and social belonging; (2) engagement in learning with a positive attitude toward effort and novelty; (3) persistence in the face of difficulties; and (4) the ability to sustain long-term commitment while developing new strategies for effective progress.

In summary, non-cognitive skills hold a pivotal place in STEM education. Their development within STEM contexts is essential for fostering the holistic growth of students and equipping them with the adaptability needed to succeed in an ever-changing world.

3 Methods

3.1 Research design

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of organizing the educational process within the framework of STEM education on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students. Specifically, we examined students' attitudes toward integrated instruction in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), as well as their cognitive, communicative, self-regulatory, and personal universal learning activities through diagnostic methods.

The design of the study, aligned with the research questions, is presented in Table 1.

The objective of the data analysis is to uncover the underlying patterns, trends, and relationships within the contextual framework of the study (Brown, 2024). Data for this research were collected from primary school students attending a public comprehensive school in Shymkent city, Kazakhstan.

3.2 Research sample

The study was conducted among second-grade students at a public general education school in Shymkent, Kazakhstan. This institution is a state-run primary and lower secondary school, which makes the findings potentially relevant to other schools of a similar type across the country. The school employs 40 primary teachers and serves 928 primary students in total. For this study, 35 second-grade students were recruited with the consent of their parents and school administration. Primary schoolchildren were assigned to two classes: a control class (n = 17; 10 boys, 7 girls) and an experimental class (n = 18; 9 boys, 9 girls). The overall sample consisted of 21 boys and 14 girls, aged 7–8 years (M = 7.5).

Second-grade students were selected because learners at this age typically demonstrate strong motivation to study and begin to develop the foundational elements of meta-subject skills. Integrating STEM-based approaches from the early grades provides opportunities to foster critical thinking, problem-solving, and inquiry-oriented activities.

The control class was taught through a traditional curriculum, whereas the Experimental class participated in lessons based on a specially designed STEM-Based Instructional Program. The program comprised 12 h of theoretical and practical learning activities aimed at stimulating interest in scientific and technical inquiry, developing spatial understanding, investigating lunar phases, exploring elements of astronomy, and engaging in engineering tasks.

STEM-integrated lessons were delivered once per week across 12 sessions. All sessions were taught by a researcher–teacher with prior training in STEM pedagogy to ensure consistency in implementation and alignment with research objectives. Lessons were conducted with the approval of school administrators and organized in a way that did not interfere with the students' core curriculum.

3.3 Research instruments

To collect data for the study, two primary instruments were employed:

3.3.1 Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST)

This test was used to assess students' perceptions and stereotypes of scientists, thereby identifying their attitudes toward science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects. Students were asked to draw a picture of a scientist. The analysis of the drawings was guided by the criteria proposed by Chambers (1983). The evaluation focused on identifying stereotypical features commonly associated with scientists working in scientific domains. These criteria included:

- Laboratory coat

- Glasses

- Beard or unusual hairstyle

- Chemical flasks or test tubes

- Labels such as “laboratory” or “experiment”

- Technical devices

- Isolation (working alone in an enclosed space)

Each feature was coded binarily (0 = absent, 1 = present). The total score represented the degree to which the student's drawing reflected a stereotypical perception of a scientist.

Scoring Criteria:

- 6–7 points: High level of stereotypical representation

- 3–5 points: Moderate level of stereotypical representation

- 0–2 points: Low level of stereotypical representation

The DAST is a qualitative method, and indeed, the high variability of drawings can create challenges in interpretation. In our analysis, considerable variation was observed in how scientists were depicted, which sometimes complicated objective evaluation. Some students produced atypical representations—such as portraying a scientist as a robot, superhero, doctor, or fantastical character—requiring additional interpretative effort. Further difficulties arose with drawings that were highly schematic or contained minimal details, where it was not possible to reliably determine the presence of specific features (e.g., a laboratory coat or laboratory setting).

3.3.2 Author-developed assessment of meta-subject skills

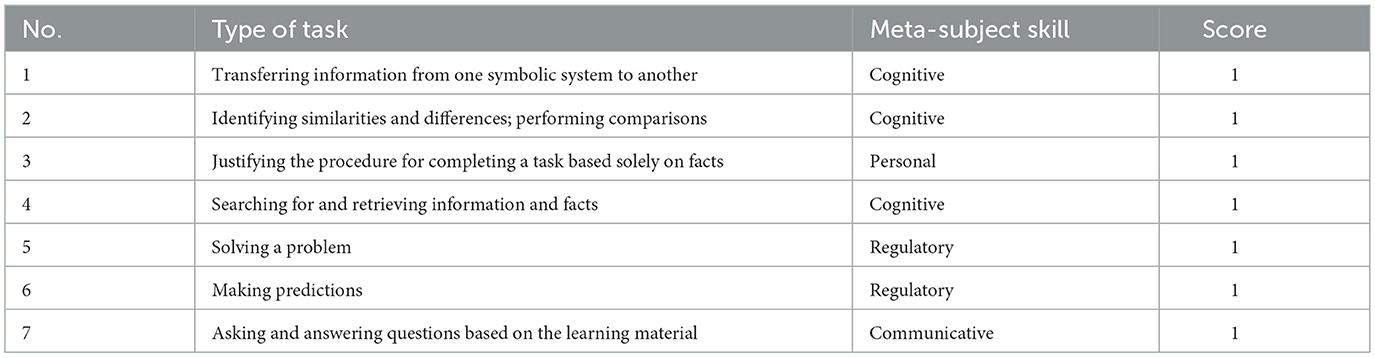

A set of 12 tasks was designed to measure students' cognitive, self-regulatory, communicative, and personal learning skills (Table 2). Each correctly completed task is awarded 1 point.

Scoring Criteria:

- 6–7 points: High level of competency

- 3–5 points: Moderate level

- 0–2 points: Low level

3.4 Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted to determine whether there were significant differences (p <0.05) between the experimental and control classes. To assess the normality of the data distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965) was applied, as it provides reliable results for small- and medium-sized samples. Since the test indicated that the data were not normally distributed, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (Mann and Whitney, 1947) was employed to evaluate differences between the groups. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0.

Research Phases:

The experimental study was implemented in three stages:

1. Diagnostic Stage: Pre-tests and competency tasks were administered to both the control and experimental classes to assess baseline levels. These tests and tasks were administered to assess students' levels of meta-subject skills and subject-specific understanding before they participated in STEM lessons. During the pre-testing phase, second-grade students had already been introduced, within the framework of the general education curriculum, to the following topics: living and non-living nature; substances and their properties; seasonal changes; and basic rules for conducting simple experiments. These topics provided the foundational basis for the STEM lessons and ensured students' readiness to engage in the research process.

2. Formative Stage: The Experimental class received instruction based on the STEM program developed by Yesnazar et al. (2024), which included STEM-based tasks, projects, and research activities integrated into the learning process. As part of the author-designed course titled “Secrets of the Universe,” a STEM-based instructional module was developed to foster meta-subject skills in primary school students. The module includes interdisciplinary STEM tasks, projects, and inquiry-based activities such as: “Young Scientist,” “I Am an Engineer,” “Phases of the Moon,” “3D Fish Model,” “Hygiene Science?”, “Journey to the World of Astronomy. The full content of the elective course and module topics is provided in Table 3.

3. Evaluation Stage: Post-tests and tasks were re-administered to both groups, and a comparative analysis was conducted to assess changes in meta-subject skills.

The research was carried out over the first and second quarters of the 2024–2025 academic year, with lessons and assessments held on Fridays each week.

4 Results

4.1 Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST)

To assess students' perceptions of scientists, the Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST) developed by Chambers (1983) was employed. Students were asked to depict a scientist on a blank sheet of paper. The drawings were evaluated against seven criteria: laboratory coat, glasses, beard or unusual hairstyle, chemical flasks or test tubes, labels such as “laboratory” or “experiment,” technical devices, and isolation (working alone or in an enclosed space). Each indicator was scored as one point, with a maximum possible score of seven.

To enhance the reliability of the analysis, three independent experts conducted the evaluation and resolved all contested issues through consensus.

Examples of students' drawings are presented in Figure 1.

The analysis revealed that, before the intervention, the majority of students held highly stereotypical views of the scientist's profession. However, following the series of lessons, a noticeable decline in the level of stereotypical representations was observed in the Experimental class, indicating the development of a more multifaceted and realistic understanding of scientific work.

At the same time, the analysis of the drawings demonstrated considerable variability in how scientists were depicted, which in some cases complicated objective evaluation. Several students presented atypical images (e.g., a scientist portrayed as a robot, superhero, doctor, or fictional character), which required additional interpretation. Further challenges arose when assessing schematic drawings or those with minimal detail, where it was difficult to determine with certainty the presence of specific indicators (e.g., laboratory coat or laboratory setting).

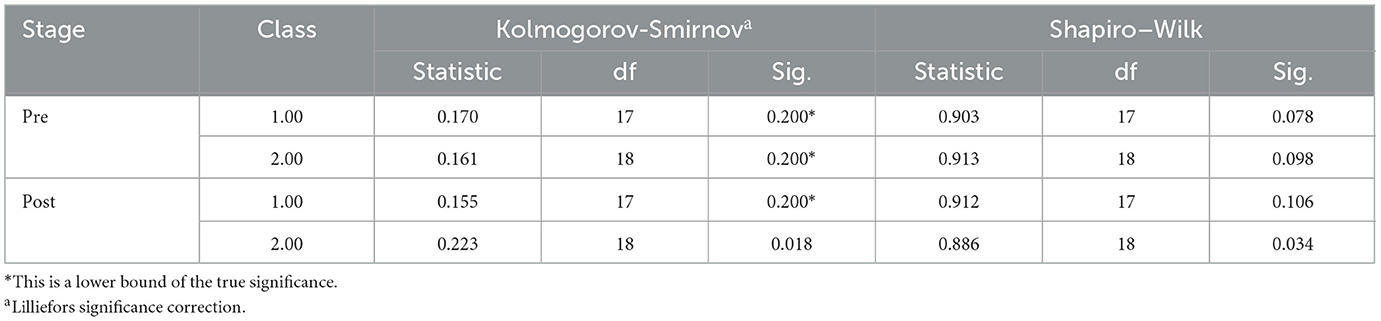

To assess the normality of the quantitative data obtained from the DAST test, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied. The results are presented in Table 4.

According to the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test, the data for both the control and Experimental classs were normally distributed in the pre-test stage (p > 0.05). However, in the post-test stage, the data from the Experimental class deviated from normality (p < 0.05). Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric method, was applied at both stages to determine differences between the groups.

In other words, because the assumptions required for applying parametric statistical methods (e.g., Student's t-test) were not fully met—specifically, the lack of normal distribution in some groups—it was considered appropriate to use the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. This approach ensures reliable statistical inferences that align with the structure of the data. The test is suitable for comparing quantitative indicators between two independent groups and does not require normally distributed data (Field, 2024).

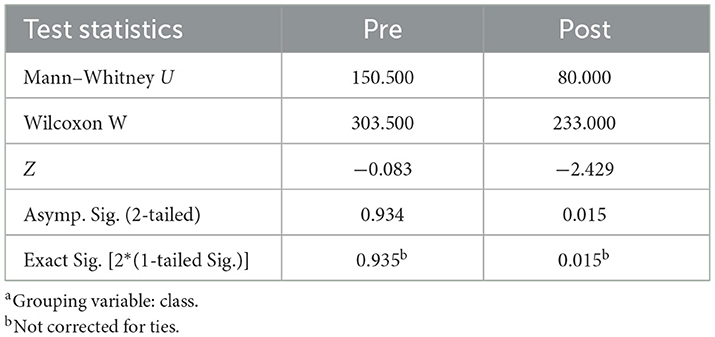

The next step is to examine the statistical values generated by SPSS for the Mann–Whitney U test (U-value and p-value). If p < 0.05, the difference is considered statistically significant (Table 5).

The pre-test analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups (U = 150.5, p = 0.934), indicating comparability of the groups at baseline. In contrast, the post-test results demonstrated a statistically significant advantage for the Experimental class over the control class (U = 80.0, p = 0.015), confirming the effectiveness of the implemented instructional approach.

4.2 Author-designed task for assessing meta-subject skills

To assess the universal learning activities (cognitive, regulatory, communicative, and personal) of primary school students, a series of author-designed diagnostic tasks was developed. The term “task” varies in definition across disciplines, but in a broad sense, it refers to an instruction that requires completion. As outlined earlier in this study, universal learning activities serve as the foundation for the development of meta-subject skills. When these activities are consistently integrated into instruction, students gradually acquire essential meta-subject skills.

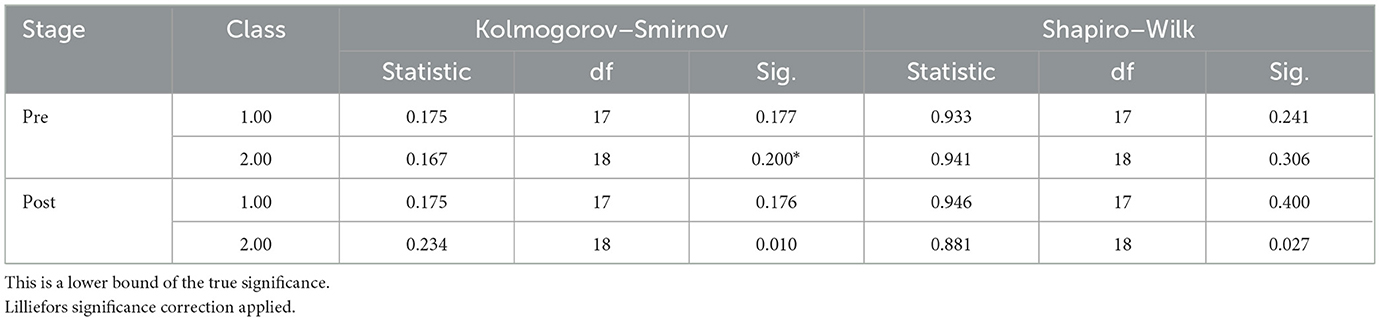

The assessment of students' meta-subject skills was based on integrated tasks. To examine whether the quantitative data followed a normal distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied. The results are presented in Table 6.

According to the Shapiro–Wilk test, the data for both control and Experimental class in the pretest stage were normally distributed (p > 0.05). However, in the posttest stage, the data for the Experimental class were not normally distributed (p < 0.05). Therefore, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was employed to compare differences between groups at both stages.

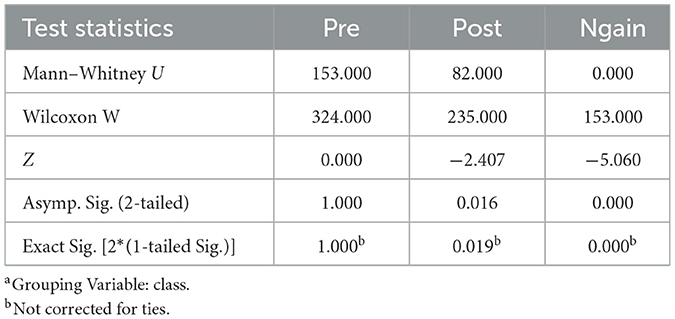

The Mann–Whitney U test results provided by SPSS are shown in Table 7.

The pre-test analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups (U = 153.000, p = 1.000), confirming their comparability at baseline. In contrast, the post-test results indicated a statistically significant advantage for the Experimental class compared to the control class (U = 82.000, p = 0.019), thereby confirming the effectiveness of the implemented instructional methodology.

(N-gain): Mann–Whitney U = 0, Z = −5.060, p < 0.001. The results indicate a highly significant difference (p < 0.001). A substantial difference was also observed in normalized gain scores (p < 0.001), which provides strong evidence of the intervention's effectiveness. We applied the N-gain method to evaluate students' progress in universal learning activities, as this approach accounts for baseline differences in pretest scores, thereby ensuring a more reliable and unbiased assessment of learning outcomes.

Overall, the statistically significant differences between the control and experimental classes demonstrate the positive impact of the experimental intervention. The higher performance of the Experimental class provides strong evidence supporting the reliability and validity of the study's findings.

5 Discussion

5.1 Analysis of the “Draw-A-Scientist Test” (DAST) results

The results of the independent t-test in our study suggest that primary school students' motivation and interest in learning science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects significantly increased following the intervention.

The outcomes of the Draw-a-Scientist Test (DAST) provided valuable insight into how students conceptualize scientists. One notable trend observed in this study is the “youthful representation” of scientists, indicating a shift in students' perceptions toward a broader and more modern image of scientific professionals. Students' drawings reflected an expanded understanding, depicting scientists not only in laboratories but also working outdoors (Bardullas and Leyva-Figueroa, 2024) and in diverse environments (Sinclair et al., 2023).

However, existing literature points out that many students still associate scientists with stereotypical traits such as being elderly, male, and working exclusively in laboratory settings (Ferguson and Lezotte, 2020). This highlights a potential limitation in the reliability and validity of the DAST instrument. For example, if students are given only a blank sheet and a single pencil without access to colored pencils or markers, they may not fully express their image of a scientist (Farland-Smith et al., 2017). Moreover, students might replicate stereotypical images of scientists from popular culture or prior education (Schibeci, 2006).

In our findings, students most commonly portrayed scientists using tools such as microscopes, wearing glasses, and conducting chemical experiments, rather than building robots or designing machines. This suggests that scientific research instruments remain the dominant symbols in their understanding of science. In some drawings, digital devices such as tablets and computers appeared as tools or symbols of scientific inquiry, indicating a growing association between technology and research.

Given this, there is a clear need to reshape students' perceptions of scientists through curriculum innovations actively. Incorporating STEM projects, hands-on scientific investigations, and play-based STEM activities into the learning process can enrich students' conceptions of science and scientific careers (Avraamidou, 2013; Thibodeau-Nielsen et al., 2025). These approaches not only deepen students' understanding of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics but also help bridge the gap between school science and real-world applications.

Furthermore, introducing students to real-life STEM careers and professionals helps cultivate early interest in science-related fields (Chen Y. W. et al., 2025; Blotnicky et al., 2018; Küçükaydin and Ayaz, 2025). To broaden students' scientific literacy, it is essential to foster collaborations between schools and research institutions (Quílez-Cervero et al., 2021). Strengthening partnerships between schools and STEM professionals (Chen et al., 2022; So et al., 2021) can also play a critical role in dismantling outdated stereotypes and providing students with authentic representations of scientists and their work.

5.2 Discussion of meta-subject skills development

The development of meta-subject skills can be effectively supported through the implementation of universal learning activities—specifically cognitive, regulatory, communicative, and personal actions—within the learning process. In this study, these universal learning actions were examined as key mechanisms in the formation of meta-subject skills. The analysis of the results obtained from the author-developed tasks provided valuable insights into students' personal, cognitive, regulatory, and communicative competencies, confirming their integral role in shaping meta-subject proficiency.

Teaching primary education subjects from a meta-subject perspective enhances students' ability to acquire integrative knowledge across disciplines (Zhumabayeva and Güven, 2018). Furthermore, the tasks designed to target regulatory universal learning activities focused on assessing metasubject outcomes related to monitoring and making predictions. Tasks aligned with cognitive universal learning activities were aimed at developing skills in information retrieval, knowledge structuring, modeling, and reflective practice.

Personal learning actions were supported through hands-on experimentation and guided questioning, allowing students to independently construct knowledge. These activities were integrated into STEM-based instruction, demonstrating that universal learning actions can be successfully implemented in STEM education environments.

Furthermore, the implementation of these actions contributed to the development of students' communicative and creative abilities, critical thinking, and inquiry-based practices. The integration of multiple subject areas helped foster interdisciplinary understanding. This instructional approach not only strengthened collaboration and peer interaction within the classroom (Öndeş, 2025) but also promoted the development of problem-solving skills in engineering contexts (Yang, 2025).

Dweck's (2013) work on goal theory and personal mindsets is particularly relevant in this context. Drawing on Dweck's (2013) theoretical perspectives, especially her concept of mindset, is useful, as it frames the development of self-regulation and growth-oriented skills as key to successful learning and overcoming challenges. For example, the category regulatory may relate to self-regulation, emotional regulation, or motivational regulation (Dweck, 2013); the category problem-solving may refer to task orientation, cognitive engagement, or adaptive coping with difficulties (Dweck and Leggett, 1988); while the category personal encompasses personal relevance, emotional involvement, or connections to personal identity (Dweck, 2006). Such a theoretical framework assigns significant value to these codes, enabling the interpretation of learners' behavioral manifestations not merely as isolated reactions but as expressions of broader meta-subject skills.

The study was conducted over 12 weeks and included 12 STEM-based lessons aimed at developing primary school students' metasubject competencies. To foster universal learning activities—regulatory, cognitive, personal, and communicative—a range of tasks was introduced, including comparison, evaluation, empirical research, solving word problems, extracting relevant information from large volumes of data, constructing diagrams, making predictions, providing arguments, identifying errors, answering questions, engaging in group games, carrying out project work, and completing creative assignments. The integration of these tasks into the educational process was implemented within the framework of STEM education.

For example, during the lesson entitled “Young Scientist,” the following tasks were proposed:

1. Construct a strong, stable, lightweight, and aesthetically pleasing bridge.

2. Test the bridge's strength by driving a toy car across it.

The development of metasubject competencies through these tasks was targeted as follows:

• Cognitive: selecting and comparing materials, identifying cause-and-effect relationships;

• Regulatory: planning the work, dividing it into stages, adjusting one's actions;

• Communicative: presenting the work, answering questions, engaging in discussion;

• Personal: expressing one's opinion, striving for success, and developing a sense of responsibility.

During task performance, students were guided by reflective and exploratory questions, such as: What did you notice when the car crossed the bridge? Did the bridge shake or break, and if so, where? What were the length and width of the bridge? What plan did you make to ensure its stability? What challenges did you encounter while constructing it? What would you change, and why? What did this task teach you?

Based on the study's results, it can be concluded that STEM-oriented tasks, projects, and inquiry activities positively influenced the formation of primary school students' meta-subject skills. These findings are further supported by observed improvements in students' creative and research abilities, as well as in their cognitive and personal learning abilities.

5.3 Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study.

First, the assessment of students' perceptions of scientists was limited to the DAST (Draw-A-Scientist Test) instrument. Future research should consider incorporating additional tools, such as the Draw-a-Science-Teacher or Draw-an-Engineer instruments, to broaden the scope of data collection.

Second, while focusing on primary school students in Kazakhstan provided valuable insights, the generalizability of the findings to other educational contexts remains limited.

Third, the STEM-based instructional program was implemented over only two academic quarters. Future research should consider the implementation of long-term STEM programs to better evaluate their effects on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students.

6 Conclusion

In response to the first research question, the findings revealed several opportunities for interdisciplinary integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics within the primary education process. These opportunities are aligned with the planning of the learning process and the implementation of active, inquiry-based learning strategies within the framework of STEM education. They also encompass the integration of creative and innovative projects, as well as research activities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics into the primary education curriculum. In addition, tasks such as constructing diagrams, making predictions, providing evidence-based arguments, identifying cause-and-effect relationships, planning, structuring knowledge, modeling, and reflecting on actions create favorable conditions for the development of meta-subject skills.

Furthermore, students begin to develop flexible (universal) skills such as engineering thinking, construction, design, and modeling. These skills enhance the creative function of instruction and contribute to a more holistic educational experience.

Concerning the second research question, the study successfully evaluated the impact of STEM-based instructional design on the development of meta-subject skills in primary school students. The experimental research was conducted using a program specifically developed for the STEM learning environment.

The research findings were subjected to statistical analysis. The results of the Mann–Whitney U test indicated an improvement in the performance of the experimental class compared to the control class. At the pretest stage, no statistically significant difference was observed between the control and experimental classes (U = 150.5; p = 0.934), confirming that both groups had comparable baseline levels of knowledge. However, the posttest results demonstrated significant changes: a statistically significant difference emerged between the control and experimental classes (U = 80.0; p = 0.015), with the experimental class outperforming the control class. These findings provide statistical evidence supporting the effectiveness of the methodology applied in the experimental class.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by E. Kerimbekov Zhanibekov University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZA: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KO: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research endeavors documented in this article have been undertaken as part of the AP19175630 project, “Development of a system for the formation of meta-subject skills of primary school students in the conditions of STEM education”. This project has been generously supported by the research grant allocated under the project “Young Scientist” initiative by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2025.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdrakhmanova, K. K., and Kudaibergenova, K. B. (2023). Readiness of school teachers to teach natural science disciplines by the method of STEM education. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan 5, 7–19. Available online at: https://journals.nauka-nanrk.kz/bulletin-science/article/view/4779/4082

Abylkassymova, A. E., Karatayeva, M. S., and Berkimbayev, K. M. (2024). Methodological foundations of training future computer science teachers for STEAM education. Bulle. Natl. Acad. Sci. Republic Kazakhstan 6, 44–62. doi: 10.32014/2024.2518-1467.853

Alfer'yeva-Termsikos, V. B. (2025). Proyektirovaniye STEM-sredy uchebnogo zavedeniya v usloviyakh tsifrovizatsii obrazovaniya [Designing STEM environment of an educational institution in the context of digitalization of education]. Epokha Nauki 41, 165–174. doi: 10.24412/2409-3203-2025-41-165-174

Asmolov, A. G., Burmenskaya, G. V., Voldarskaya, I. A., and Molchanov, S. V. (2014). Formirovaniye universal‘nykh uchebnykh deystviy v osnovnoy shkole: ot deystviya k mysli. Sistema zadaniy: posobiye dlya uchitelya [Formation of Universal Educational actions in Basic School: From Action to Thought. System of Tasks: Teachers' Book]. Moscow: Prosveshcheniye.

Avraamidou, L. (2013). Superheroes and supervillains: reconstructing the mad-scientist stereotype in school science. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 31, 90–115. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2012.761605

Aytbaev, S. T., Sumatokhin, S. V., Kitapbayeva, A. A., Seksenova, D. U., and Atalikhova, G. B. (2023). Formative assessment – as a tool for monitoring metasubject educational results at school. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Republic Kazakhstan 6, 38–51. doi: 10.32014/2023.2518-1467.615

Baiganova, A. M., and Nauryzova, N. K. (2024). STEM okytuga arnalgan programmalyk zhabdykty azirleu [Software development for STEM education]. Vestnik Aktyubinskogo Regional'nogo Universiteta Imeni K. Zhubanova 1, 8–15. doi: 10.70239/arsu.2024.t75.n1.02

Bardullas, U., and Leyva-Figueroa, E. (2024). Unveiling stereotypes: a study on science perceptions among children in Northwest Mexico. Res. Sci. Educ. 54, 1199–1215. doi: 10.1007/s11165-024-10175-4

Bartels, S., and Lederman, J. (2022). What do elementary students know about science, scientists and how they do their work? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44, 627–646. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2022.2050487

Bilim berudegi STEM-tasilin iske asyrudyn didaktikalyk negizderi: adistemelik kural [Didactic foundations of implementing the STEM approach in education: methodological book]. (2023). Astana: Y. Altynsarin National Academy of Education.

Blotnicky, K., Franz-Odendaal, T., French, F., and Joy, P. (2018). A study of the correlation between STEM career knowledge, mathematics self-efficacy, career interests, and career activities on the likelihood of pursuing STEM career among middle school students. Int. J. STEM Educ. 5:22. doi: 10.1186/s40594-018-0118-3

Brown, G. (2024). Teaching advanced statistical methods to postgraduate novices: a case example. Front. Educ. 8:1302326. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1302326

Buzni, V. A., and Osipenko, S. D. (2025). Razvitiye kreativnogo i kriticheskogo myshleniya obuchayushchikhsya nachal'noy shkoly cherez STEAM-proyekty. [Development of creative and critical thinking of primary school students through STEAM projects]. Problemy sovremennogo pedagogicheskogo obrazovaniya 86, 38–40. Available online at: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/razvitie-kreativnogo-i-kriticheskogo-myshleniya-obuchayuschihsya-nachalnoy-shkoly-cherez-steam-proekty

Chambers, D. W. (1983). Stereotypic images of the scientist: the draw-A-scientist test. Sci. Educ. 67, 255–265. doi: 10.1002/sce.3730670213

Chen, B., Chen, J., Wang, M., Tsai, C.-C., and Kirschner, P. A. (2025). The Effects of integrated STEM education on K12 students' achievements: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. doi: 10.3102/00346543251318297

Chen, Y., Chow, S. C. F., and So, W. W. M. (2022). School-STEM professional collaboration to diversify stereotypes and increase interest in STEM careers among primary school students. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 42, 556–573. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2020.1841604

Chen, Y. W., Wang, Y., Wing, M., and So, W. (2025). The effects of specialist co-teaching STEM intervention on primary students' attitudes, perceptions, behaviors, and career aspiration: a mixed-methods study in China. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanced Learn. 20:38. doi: 10.58459/rptel.2025.20038

Dosymov, Y., Ualihan, A., and Bakirjankyzy, A. (2025). ≪Atom fizikasy≫ kursyn STEM bilim beru negizinde oqytu tiimdiligin zertteu [Research on the Effectiveness of Teaching the Course ≪Atomic Physics≫Based on STEM Education]. Iasaui Universitetinin Habarshysy 1, 432–443. doi: 10.47526/2025-1/2664-0686.176

Drake, S. M., and Reid, J. L. (2020). 21st century competencies in light of the history of integrated curriculum. Front. Educ. 5:122. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00122

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Random House. Available online at: https://adrvantage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Mindset-The-New-Psychology-of-Success-Dweck.pdf (Accessed October 16, 2025).

Dweck, C. S. (2013). Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. New York, NY: Psychology Press. doi: 10.4324/9781315783048

Dweck, C. S., and Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95, 256–273. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2014). Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills that Promote Long-Term Learning. Seattle, WA: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Emvalotis, A., and Koutsianou, A. (2018). Greek primary school students' images of scientists and their work: has anything changed? Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 36, 69–85. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2017.1366899

English, L. D. (2016). STEM education K-12: perspectives on integration. Int. J. STEM Educ. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40594-016-0036-1

Farland-Smith, D. (2009). How does culture shape students' perceptions of scientists? Cross-national comparative study of American and Chinese elementary students. J. Elementary Sci. Educ. 21, 23–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03182355

Farland-Smith, D. (2012). Development and field test of the modified draw-a-scientist test and the draw-a-scientist rubric. Sch. Sci. Math. 112, 109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-8594.2011.00124.x

Farland-Smith, D., Finson, K., Boone, W. J., and Yale, M. (2014). An investigation of media influences on elementary students representations of scientists. J. Sci. Teacher Educ. 25, 355–366. doi: 10.1007/s10972-012-9322-z

Farland-Smith, D., Finson, K. D., and Arquette, C. M. (2017). How picture books on the National Science Teacher's Association recommend list portray scientists. Sch. Sci. Math. 117, 250–258. doi: 10.1111/ssm.12231

Ferguson, S. L., and Lezotte, S. M. (2020). Exploring the state of science stereotypes: systematic review and meta-analysis of the Draw-A-Scientist Checklist. Sch. Sci. Math. 120, 55–65. doi: 10.1111/ssm.12382

Field, A. (2024). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. London: Sage Publications Limited. Available online at: http://sadbhavnapublications.org/research-enrichment-material/2-Statistical-Books/Discovering-Statistics-Using-IBM-SPSS-Statistics-4th-c2013-Andy-Field.pdf (Accessed October 16, 2025).

Finson, K. D. (2002). Drawing a scientist: what we do and do not know after fifty years of drawings. Sch. Sci. Math. 102, 335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-8594.2002.tb18217.x

Fung, Y. Y. (2002). A comparative study of primary and secondary school students' images of scientists. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 20, 199–213. doi: 10.1080/0263514022000030453

Gromyko, N. V. (2004). Mysledeyatel'nostnaya pedagogika i novoye soderzhaniye obrazovaniya. Metapredmety kak sredstvo formirovaniya refleksivnogo myshleniya u shkol'nikov. Mysledeyatel'nostnaya pedagogika v starshey shkole: metapredmety [Thought-Activity Pedagogy and New Content of Education. Meta-Subjects as a Means of Forming Reflective Thinking in Schoolchildren. Thought-Activity Pedagogy in Senior School: Meta-Subjects]. Moscow: APKiPRO.

Han, C., woo Farruggia, S. P., and Solomon, B. J. (2020). Effects of high school students' noncognitive factors on their success at college. Stud. High. Educ. 47, 572–586. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1770715

Havice, W., Havice, P., Waugaman, C., and Walker, K. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of integrative STEM education: teacher and administrator professional development. J. Technol. Educ. 29, 73–90. doi: 10.21061/jte.v29i2.a.5

Iskakova, L., Alpysbay, L., and Yermakhanov, B. (2023). Developing critical thinking skills of primary school students through STEM programs. Bull. Abai KazNPU Series Pedagog. Sci. 1, 228–238. doi: 10.51889/1728-5496.2023.1.76.024

Kadirbaeva, R. I., and Zhitabay, N. M. (2025). The essence and significance of using STEM technologies in teaching mathematics to high school students. Bull. Ser: Pedagog. Sci. 2, 649–666.

Karataev, N. S., Ibashova, A. B., and Bulbul, H. I. (2024). STEAM-based robotics training for elementary school students. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Republic Kazakhstan 4, 272–281. doi: 10.32014/2024.2518-1467.804

Kelley, T. R., and Knowles, J. G. (2016). A conceptual framework for integrated STEM education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 3:11. doi: 10.1186/s40594-016-0046-z

Khutorskoy, A. V. (2012). Metapredmetnyy podkhod v obuchenii: nauchno-metodicheskoye posobiye [Meta-Subject Approach in Teaching: Scientific and Methodological Book]. Moscow: Izdatel'stvo “Eidos”.

Küçükaydin, M. A., and Ayaz, E. (2025). Modelling the relationship between parents' STEM awareness and elementary school children's STEM career interest and attitudes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 28:31. doi: 10.1007/s11218-024-10000-w

Kudaibergenova, Q. B., Abdrahmanova, H. K., and Umbetkulova, A. K. (2022). Turkiya memleketinin STEM-bilim beru boiynsha tajiribesi [Experience of Turkey in STEM education]. Iasaui Universitetinin Habarshysy 4, 294–304. doi: 10.47526/2022-4/2664-0686.25

Losh, S. C., Wilke, R., and Pop, M. (2008). Some methodological issues with “Draw a Scientist Tests” among young children. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 30, 773–792. doi: 10.1080/09500690701250452

Luo, T., and So, W. W. M. (2023). Elementary students' perceptions of STEM professionals. Int. J. Technol. Design Educ. 33, 1369–1388. doi: 10.1007/s10798-022-09791-w

Mann, H. B., and Whitney, D. R. (1947). On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 18, 50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491

Maratova, T. F., Bostanov, B. G., Kultan, J., and Nauryzbayev, D. B. (2023). Systematic review of scientific research on the training of future computer science teachers based on STEAM education. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Phys. Math. Sci. 2, 253–259.

Martín-Páez, T., Aguilera, D., Perales-Palacios, F. J., and Vílchez-González, J. M. (2019). What are we talking about when we talk about STEM education? A review of literature. Sci. Educ. 103, 799–822. doi: 10.1002/sce.21522

Medina-Jerez, W., Middleton, K. V., and Orihuela-Rabaza, W. (2011). Using the DAST-c to explore colombian and bolivian students'images of scientists. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 9, 657–690. doi: 10.1007/s10763-010-9218-3

Menon, D., Johnson, A. M., Cox, D., Nguyen, U., Jeon, M., and Thomas, A. (2025). STEM-themed pathways within elementary preservice methods coursework: benefits and challenges associated with designing and implementing integrated STEM projects. Sch. Sci. Math. 1–13. doi: 10.1111/ssm.18321

Mukhamediyeva, K. M., Nurgazinova, G.S, Abykenova, D. B., Abisheva, I. S., et al. (2023). Implementation of artificial intelligence in education through the development of STEM projects. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Republic Kazakhstan 5, 190–204.

Nishanbayeva, S., Sadvakas, G. T., and Abilkhairova, Z. A. (2021). Okytu uderisindegi gylymiy tusinikter arkyly bastauysh synyp okushylarynyn zertteushilik madenietin kalyptastyru [Formation of research culture of younger schoolchildren through scientific ideas in the learning process]. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Pedagog. Sci. 72, 286–297. doi: 10.51889/2021-4.1728-5496.33

Öndeş, R. N. (2025). Research trends in STEM clubs: a content analysis. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 23, 561–588. doi: 10.1007/s10763-024-10477-z

Ospanbekova, M., Ryskulbekova, A., Iskakova, L., and Kara, A. (2024). Training of future specialists for the use of STEM laboratories in primary education. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Pedagog. Sci. 3, 210–222. doi: 10.51889/2959-5762.2024.83.3.019

Quílez-Cervero, C., Diez-Ojeda, M., López Gallego, A. A., and Queiruga-Dios, M. Á. (2021). Has the stereotype of the scientist changed in early primary school–aged students due to COVID-19? Educ. Sci. 11:365. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070365

Ramankulov, S., and Gench, N. (2025). ≪Balamaly energia jobalaryndagy STEAM: kun energiasy≫ kursyn agylshyn tilinde oqytudyn adistemelik erekshelikteri [Methodological features of teaching the course ≪STEAM in alternative energy projects: solar energy≫ in English]. Iasaui Universitetinin Habarshysy 1, 257–267. doi: 10.47526/2025-1/2664-0686.161

Reutskaya, I. V. (2021). STEM tekhnologii v srednem professional'nom obrazovanii [STEM technologies in secondary vocational education]. Yestestvenno-Gumanitarnyye Issledovaniya 3, 197–199. doi: 10.24412/2309-4788-2021-11151

Sanders, M. (2009). STEM, STEM education, STEMmania. Technol. Teach. 68, 20–26. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237748408_STEM_STEM_education_STEMmania

Satylmysh, Y., Zhumakayeva, B. D., and Bekenova, G. S. (2025). Problems of teaching chemistry lessons in an integrated STEM context in secondary education. 3i: Intellect Idea Innov. 1, 398–404. doi: 10.52269/22266070_2025_1_398

Saudabayeva, G. S., and Sholpankulova, G. K. (2020). Panaralyk bajlanys negizinde studentterde metapandik kuzyretterdi kalyptastyru [Formation of meta-subject competence of students based on interdisciplinary communications]. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Pedagog. Sci. 1, 43–48. doi: 10.51889/2020-1.1728-5496.07

Schibeci, R. (2006). Student images of scientists: what are they? Do they matter? Teach. Sci. 52, 12–16. Available online at: https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=61MUN_INST&filePid=13136898950007891&download=true

Schiepe-Tiska, A., Heinle, A., Dümig, P., Reinhold, F., and Reiss, K. (2021). Achieving multidimensional educational goals through standard-oriented teaching. An application to STEM education. Front. Educ. 6:592165. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.592165

Shapiro, S. S., and Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611. doi: 10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591

Sinclair, B. B., Long, C. S., Szabo, S., and Naizer, G. (2023). Investigating equitable representation in K-8 science textbook portrayal of scientists. Sci. Educ. 34, 1189–1202. doi: 10.1007/s11191-023-00482-z

So, W. M. W., He, Q., Chen, Y., and Chow, C. F. (2021). School-STEM professionals' collaboration: a case study on teachers' conceptions. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 49, 300–318. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2020.1774743

STEM - bilim beru tuzhyrymdamasy [The concept of STEM education]. (2023). Astana: Y. Altynsarin National Academy of Education.

STEM - tekhnologiya negizinde orta bilim beru mazmunyn kajta kurylymdau [Restructuring the content of secondary education based on STEM technology]. (2022). Nur-Sultan. Astana: Y. Altynsarin National Academy of Education.

Sultanova, G., and Shora, N. (2024). Comparing the impact of non-cognitive skills in STEM and non-STEM contexts in Kazakh Secondary Education. Educ. Sci. 14:1109. doi: 10.3390/educsci14101109

Sun, D., Zhan, Y., Wan, Z. H., Yang, Y., and Looi, C. K. (2025). Identifying the roles of technology: a systematic review of STEM education in primary and secondary schools from 2015 to 2023. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 43, 145–169. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2023.2251902

Thibaut, L., Ceuppens, S., De Loof, H., De Meester, J., Goovaerts, L., Struyf, A., et al. (2018). Integrated STEM education: a systematic review of instructional practices in secondary education. Eur. J. STEM Educ. 3:2. doi: 10.20897/ejsteme/85525

Thibodeau-Nielsen, R. B., Rueda-Posada, M. F., Dier, S. E., Dooley, A. W., Nadler, D. R., and Coxon, S. V. (2025). Exploring playful opportunities for STEM learning in early elementary school. Early Educ. Dev. 36, 1499–1514. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2025.2478653

Tulentayeva, G., Seylova, Z., and Berkimbayev, K. (2023). The content of the discipline “higher mathematics” in the training of technical personnel in the conditions of the STEAM education. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Pedagog. Sci. 80, 154–167. doi: 10.51889/2959-5762.2023.80.4.015

Turysbayeva, A., and Turalbayeva, A. (2024). The use of formative assessment in the development of meta-subject results of primary school students. Bull. Abai KazNPU Ser. Pedagog. Sci. 2, 419–437. doi: 10.51889/2959-5762.2024.84.4.037

Upadhyay, B., Alberts, J., Coffino, K., and Rummel, A. (2021a). Building a successful university and school partnership for STEAM education: lessons from the trenches. Southeast Asian J. STEM Educ. 2, 127–150.

Upadhyay, B., Coffino, K., Alberts, J., and Rummel, A. (2021b). STEAM education for critical consciousness: discourses of liberation and social change among sixth-grade students. Asia-Pac. Sci. Educ. 7, 64–95. doi: 10.1163/23641177-bja10020

Yang, K. K. (2025). Exploring primary school students drawing solutions to problems in STEM activities. Thinking Skills Creat. 56:101790. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2025.101790

Yesnazar, A., Zhorabekova, A., Kalzhanova, A., Bayymbetova, Z., and Almukhanbet, S. (2024). Methodological system for formation of meta-subject skills of primary school students in the context of STEM education. Front. Educ. 9:340361. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1340361

Zhandarbayeva, A. M., Ualikhanova, B. S., and Turmambekov, T. A. (2025). Features of modern physics teaching through the finnish education system. ILIM 2, 31–56. doi: 10.47751/skpu.1937.v44i2.2

Zhumabayeva, Z., Uaisova, G., and Jetpisbayeva, S. (2021). Meta-Subject methodology approach in the training of future primary school teachers. World J. Educ. Technol.: Curr. Issues 13, 21–30. doi: 10.18844/wjet.v13i1.5406

Zhumabayeva, Z. A., and Güven, M. (2018). “Bastauysh synypta kazak tilin metapandik turgyda okytu [Teaching the Kazakh language in a meta-disciplinary perspective in primary school],” in Proceedings of the International Forum of the Association of Pedagogical Universities “Problems of Continuing Pedagogical Education: Tradition and Innovations” (Almaty: Abai KazNPU), 104–110.

Keywords: STEM, STEM education, meta-subject skills, STEM in primary education, STEM-based instructional program

Citation: Yesnazar A, Zhorabekova A, Kalzhanova A, Abilkhairova Z, Ortaeva K and Jumassaeva Z (2025) STEM education impact on the development of primary school students' meta-subject skills: an experimental study in Kazakhstan. Front. Educ. 10:1669765. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1669765

Received: 20 July 2025; Accepted: 09 October 2025;

Published: 14 November 2025.

Edited by:

Dina Tavares, Polytechnic University of Leiria, PortugalReviewed by:

Bhaskar Upadhyay, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesÖzlem Gökçe Tekin, Independant Reviewer, Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Yesnazar, Zhorabekova, Kalzhanova, Abilkhairova, Ortaeva and Jumassaeva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ainur Zhorabekova, YWludXIuemhvcmFiZWtvdmFAYXVlem92LmVkdS5reg==; Zhanar Abilkhairova, Wmhhbl9hYUBtYWlsLnJ1

Asel Yesnazar

Asel Yesnazar Ainur Zhorabekova

Ainur Zhorabekova Altynai Kalzhanova

Altynai Kalzhanova Zhanar Abilkhairova

Zhanar Abilkhairova Kamila Ortaeva

Kamila Ortaeva Zhuldyz Jumassaeva

Zhuldyz Jumassaeva