- Business School, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

University students often face both intellectual and emotional pressures that can affect how well they perform in their studies. To deal with these challenges, one useful approach is help-seeking, where students reach out for support when needed. In many cases, staff have observed that students turn to them for guidance after attempts to get assistance from peers were not effective. Help-seeking plays an important role in how students adjust to university life, influencing their academic, psychological, and social experiences. Previous studies show the link between help-seeking and adjustment, but there are still gaps, especially in research that looks at these issues over time and across different cultural contexts. This study therefore sets out to explore how help-seeking, adjustment, and workload interact and shape the academic performance of university students. The study used a survey research methodology to gather quantitative data and analyze correlations among factors. Conducted in South Africa, it targeted full-time academic and support staff from Regent Business School and MANCOSA. Questionnaires were distributed to the entire population, yielding 247 valid responses out of 250 (98.8%). Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed for the analysis, while Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to assess the presented hypotheses. Affective Factors (attitude toward support) emerged as the strongest determinant of academic performance (β = 0.478, f2 = 0.237, p < 0.001), highlighting the crucial role of students’ emotional engagement and motivational orientation. This implies that students who perceive institutional and peer support positively are more likely to achieve better academic outcomes. The strong effect size reinforces the value of fostering supportive academic environments that build emotional confidence. These results suggest that students who are emotionally engaged and well-adjusted, as well as those who actively seek help, are more likely to undertake greater academic tasks and responsibilities.

1 Introduction

In modern schooling, students face significant intellectual and emotional challenges that necessitate effective strategies for managing stressors and maintaining high academic performance. This affirmation is buttressed by the works of Kong et al. (2025), who were able to attest to the high place of information that welcomes the 21st century with respect to learning. Although data have confirmed its importance, the detailed interaction between adjusting, and workload remains poorly explained and irregularly noted, especially within high-stress learning environments like higher institutions of learning (Martín-Arbós et al., 2021). Help-seeking, framed under self-regulated learning, is a metacognitive and motivational behavior whereby learners recognise their academic challenges and make efforts to solve these through interpersonal or institutional resources (Umar et al., 2023). The extent to which help-seeking manifests as real adjustment is understood as students’ psychological, academic, and social adaptation to the university environment. This depends on several contextual and dispositional variables, including perceived stigma, cultural norms, and workload intensity (Shanahan, 2021). Such heavy workloads in competitive educational systems have also been identified as barriers that not only enhance psychological distress but also hinder help-seeking behavior wherein individuals may be afraid of negative evaluation or judgment regarding their difficulties.

Adjustment is conceptualized as an emergent, multifaceted construct that is vital to understanding students’ outcomes such as performance, retention, and mental health during academic stressors because it acts as a mediator (Nwadi et al., 2025). In other words, recent evidence suggests that help-seeking is a strong predictor of positive adjustment and can be influenced by academic workload (Tinto, 2017). In the view of this study, the concept of help seeking is from the perspective of the student having the second tire of meeting the faculty to resolve their academic dispute. This comes after the attainment of the initial meeting of their fellow students but the help could not translate into the expected need. The causal pathways are unclear, with limited evidence on whether a heavy workload automatically reduces the ability to seek help due to lack of time or if maladaptive adjustment constrains the consideration of workload, thereby limiting help-seeking. Indeed, models tend to underrepresent this reciprocal complexity and are especially limited when considering the educational experiences of students in different cultural or resource-deprived contexts (Harvey et al., 2025). Examined literatures (Kaymakcioglu and Thomas, 2024; Harmon and Hunter, 2025; López Flores et al., 2025) has established that there is a noticeable absence of longitudinal and cross-cultural studies simultaneously explaining these relationships. Much of the literature (Bisschoff et al., 2024; Tshivhase and Bisschoff, 2024) available arguably favours cumulative or separate explanations of these constructs, as they fail to discuss how the process of students’ workload pressures and help-seeking behaviors evolve concurrently and how they both influence the trajectory of students’ performance over time. This lack of integrative understanding hinders institutional policy in modeling a setup for effective support facilities for students adjusting to the dual responsibilities of performing academically while psychosocially adjusting to a new environment.

The complexities of students’ academic achievement encompass a combination of help-seeking behaviors, psychological adjustment, and perceived workload (Davison et al., 2023; Bisschoff et al., 2024; Cassim et al., 2024). Each construct has been evaluated independently, with few studies simultaneously estimating their predictive utility for students in higher education, particularly in Africa. For this reason, this research aims is to examine the dynamic and mutual relationship between help-seeking, adjustment, and workload on university students’ performance. This research will add to a stronger theoretical and practical understanding of how students cope with academic difficulties. It will also show how universities can design interventions that support students’ adjustment, especially by helping them manage their workload through available help-seeking options.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical framework

The relationship between help-seeking, adjustment, workload, and academic performance can be explained through Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) Theory and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. SRL, as outlined by Zimmerman (2000), views learners as active participants who use strategies such as setting goals, monitoring progress, taking purposeful action, and seeking help to manage their learning. Most notably, Help-seeking is not viewed as a lack of confidence but as an advanced metacognitive strategy of a learner often used in recognising their limitations and to intentionally use out-of-school resources to address those weaknesses. The Zimmerman theory states that the process is cyclical, and factors can include forethought (goal-setting, planning), performance (self-checking and employing a strategy), self-reflection (evaluating, adjusting), the components of help-seeking, workload management, and adjusting/adjustment strategies. Students in tertiary institutions who successfully engage in self-regulated learning are often better at seeking academic help, adapt more effectively to new learning situations and environments, and, when engaged, manage cognitive load more effectively (Panadero, 2017). Additionally, research has demonstrated that students who employ SRL strategies, particularly those behaviors and activities associated with planning and help-seeking, are significantly more likely to achieve higher academic performance (Dent and Koenka, 2016). Therefore, the studies on SRL provide a background for consideration of how students engage with academic challenges by applying different cognitive, motivational, and behavioral elements of the regulation of the learning process.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, developed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), is a dynamic model that describes how individuals perceive and respond to academic stressors, such as an increased workload, operating in a new situation, and evaluations during a course. The model indicates that stress arises from the interaction between environmental demands and an individual’s appraisal of available coping resources. On the premise of a hypothetical situation, a scenario where students appraise the workload to be overwhelming and beyond their unique coping abilities, will invariably result in a need for academic adjustment and poor outcomes (Folkman and Lazarus, 1985). More generally, students who demonstrate stronger coping strategies, such as effective time management principles, seeking help, and having social support networks, tend to manage and maintain better psychological adjustment and academic achievement (Cheng et al., 2019). In addition, the model differentiates between problem-focused coping (e.g., enlisting help, restructuring of work activities) and emotion-focused coping (e.g., avoidance, denial) (Bisschoff et al., 2024). While students often engage in these types of coping strategies, problem-focused coping is more definitively associated with positive academic outcomes. More recent studies have substantiated the applicability of this model to educational contexts (Bisschoff et al., 2024; Cassim et al., 2024). Basith et al. (2021) found that university students with higher academic resilience as defined by adaptive coping and self-regulation had better adjustment and achievement even under higher workload expectations. Consequently, the Transactional Model accurately suggests that students’ perceptions and responses to academic demands significantly contribute to both their psychological well-being and academic performance.

2.2 Related empirical studies

Studies (da Conceição et al., 2024; Fan, 2025; Wang et al., 2025) has indicated that help-seeking behavior is crucial in predicting students’ achievement. In the United Kingdom, Davison et al. (2023) examined the metacognitive and motivational dimensions of help-seeking using a microlongitudinal design. According to their research, students who seek help do get higher grades (controlling for background factors). They also found that students taught strategic help-seeking outperformed academically. In the same vein, Martín-Arbós et al. (2021), in a systematic review of 15 university-based studies, found that adaptive help-seeking practices, such as asking teachers or classmates for assistance, were positively associated with grade point average (GPA).

Help-seeking has become a growing focus in educational research, with studies highlighting its role in students’ academic success. For example, Davison et al. (2023), in a microlongitudinal study conducted in the UK, reported that students who sought learning support when necessary, earned significantly higher grades. In their focus group, Davison et al. (2023) drew attention to the ‘metacognitive’ and ‘motivation’ variables that lay behind help-seeking and showed that when educators taught students about help-seeking and advised them appropriately about advice-seeking, their performance improved. Similarly, Martín-Arbós et al. (2021), in a systematic review of literature, found that adaptive help-seeking behaviors, e.g., connecting with other students or instructors, were positively correlated with student GPA in 15 studies framed in undergraduates’ contexts, providing evidence for socio-emotional learning variables impacting academic success.

Studies examining barriers to help-seeking have been useful. Bimerew and Arendse (2024) found that over 60 percent of first-year nursing students in South Africa were unsuccessful in their help-seeking efforts because they had limited peer networks, formal help-seeking options such as tutors; language and increased failure rates (Bimerew and Arendse, 2024). similarly, quantitative intervention study done in Nigeria found that barriers to help-seeking resulted from low self-esteem and language insecurity, which contributed to reduced help-seeking; although, the barriers to help-seeking that were stigma-related stemmed from academic anxiety (Dueñas et al., 2025). Overall, these findings suggest that help-seeking success is conditional and context-dependent, whereas help-seeking can similarly rely on social support or availability of emotional supports (Martín-Arbós et al., 2021; Sithaldeen et al., 2022). It is on this note that the study’s hypotheses state that:

Hypothesis 1: Helpseeking has a significant positive effect on General Means of Academic Performance

Hypothesis 2: Help-seeking has a significant positive effect on Workload

Umar et al. (2023) studied mechanical-technology undergraduates from northern Nigeria. They found that help-seeking, academic motivation, and self-esteem predicted approximately 35% of the variance in academic performance but not university adjustment, meaning that coping strategies could support performance. There was little rationale to suggest that the performance was a result of improved adjustment (Umar et al., 2023). In Zambia, by studying first-year students using qualitative methods, Mwale et al. (2023) showed that inadequate preparation and stresses of cultural transition obstructed students’ academic adjustment, though it was evident that financial insecurity and homesickness were key factors. This finding is consistent with research in South Africa, which showed that disadvantaged students who experience poor adjustment tend to report lower grades and higher withdrawal rates (Mwale et al., 2023). This therefore, culminate into the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Adjustment has a significant positive effect on General Means of Academic Performance

Hypothesis 4: Adjustment has a significant positive effect on Workload

Hypothesis 5: Affective Factors have a significant positive effect on the General Means of Academic Performance

Hypothesis 6: Affective Factors have a significant positive effect on Workload

Workload (volume and structure) is another area that has recently drawn the attention of researchers as Ojo (2014) investigates the influence of academic overload and help-seeking behavior as predictors of academic performance of biology undergraduates at the Tai Solarin University of Education. The author found that there was no significant relationship between academic overload and academic performance, while help-seeking behavior did predict the academic performance of students. In a large mixed-methods study of medical undergraduates in the UK, the implementation of time-management coaching led to significant improvements in both academic performance and psychological wellbeing (Harvey et al., 2025). However, an excessive workload, even when suitably structured, can increase distress and exacerbate feelings of burnout (Harvey et al., 2025). In a separate intervention study in Nigeria targeting vocational education students, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness training reduced test anxiety by 22% and enhanced achievement scores by 15 percentage points, demonstrating a demonstrably positive influence of structured workload support (Nwadi et al., 2025). Invariably, from this and overall, the study hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 7: Workload has a significant positive effect on General Means of Academic Performance

Hypothesis 8: Help-seeking support has an indirect positive effect on General Means of Academic Performance (GMAP) through its influence on workload

Hypothesis 9: Adjustment indirectly influenceGeneral Means of Academic Performance (GMAP) through its effect on workload

Hypothesis 10: Affective Factors indirectly influence General Means of Academic Performance (GMAP) through its effect on workload.

This brings to light that rather than simply summarizing prior studies, this review highlights unresolved tensions in how help-seeking, adjustment, affective factors, and workload are understood as predictors of academic performance. Existing work (Cassim et al., 2024; López Flores et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025) often examines these constructs in isolation, with limited attention to how they interact or are perceived within specific institutional contexts. By addressing these gaps, the present study clarifies its unique contribution to the literature. In line with the generated hypothesis, the study conceptual model has been drawn to reflect this in Figure 1.

2.2.1 Conceptualized general means of academic performance model

Although help-seeking, adjustment, and workload are recognized as critical factors in students’ academic success, prior studies (Umar et al., 2023; da Conceição et al., 2024; Fan, 2025; Harvey et al., 2025; Nwadi et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025), have mostly examined them in isolation by offering limited insights into their reciprocal interactions. Thereby, rendering the evidence on the causal pathways to remain inconclusive. This creates a lack of longitudinal and cross-cultural research in capturing how these constructs evolve together to shape performance, particularly in resource-constrained contexts. This study therefore investigates the dynamic relationship among help-seeking, adjustment, and workload, with the aim of advancing theory and informing institutional policies that foster adaptive student adjustment and improved academic outcomes.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

The study adopted a survey design to collect quantitative data and examine the relationships among variables. A survey was considered suitable because it allows researchers to gather broad and reliable information about the target population (Ponto 2015). This approach also helped reduce bias and provided a structured way to analyze the data (Saunders et al., 2019).

3.2 Population of the study, sample and sampling technique

The target population for this study consisted of all full-time academic and support staff members from two private business schools: Regent Business School and the Management College of South Africa (MANCOSA), excluding part-time staff. These organisations were selected because they have a broad geographical coverage in South Africa and Southern Africa, account for a substantial proportion of the private business school market, and because of strong endorsement for the research from senior management. The research sought to involve the entire population rather than a sample, allowing all eligible staff to share their perspectives. Participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous, and inclusion was limited to full-time employees, with part-time or temporary staff excluded. To facilitate data collection, questionnaires were distributed via academic administrators at the Durban headquarters and trained office managers at the regional offices. Out of 250 questionnaires sent, 247 were completed and returned, resulting in an effective response rate of 98.8%. The collected data were processed by the Statistical Consultation Services of North-West University and analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp, 2025), while PLS-SEM via SmartPLS 4 was employed for schematic analysis of the designated variables. The data was collected over a period of 3 months in 2019. The data was not affected by COVID 19 as it was just before the hard lockdown.

3.3 Method of data collection

The survey consisted of two sections: Section A, Demographics, and Section B, Measurement Criteria. Section A comprised five questions designed to collect demographic information from the respondents. Section B encompassed five antecedents, each characterised by unique measuring criteria, about components of academic success. Participants were asked to evaluate their level of agreement or disagreement with the criteria using a five-point Likert scale. The criteria were articulated as statements. Section B had a total of twenty-seven measurement criteria.

3.4 Method of data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed for the analysis, as required by the problem. Percentage tables, mean, and standard deviation were used to evaluate the survey responses. The questionnaire was drafted from the theory by using exploratory factor analysis to ensure each antecedent (factor)’s statements measure the specific factor it is supposed to measure. In total, the statistical analysis omitted 26 criteria from the initial theoretical and quantitative model of 86 measuring criteria because of their low- or dual factor loadings (≤0.4). All ten factors have excellent reliability that exceeds the minimum alpha coefficient of 0.70 with ease (six factors have alpha coefficients in excess of 0.90). It was from this data that the 25 constructs were harnessed to the outlined 5 identified d variables (Rehman et al., 2019). Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to assess the presented hypotheses at a significance level of 0.05 using Smart PLS 4 software. If the alpha is below the significance criterion of 5% (0.05), the null hypothesis will be rejected, indicating that the whole model is significant. The f value signifies the explained variability and the likelihood that the model is a result of random chance. The Adjusted R Square measures the variation explained by the model; a higher explained variance indicates a more dependable model.

3.5 Ethical considerations

The Ethical Committee of North-West University (Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences) evaluated this work for compliance with its ethical principles, processes, and rules. The committee approved the research and classified it as low-risk; a study-specific ethics number, NWU-00600-20-A4, was given.

4 Result

The methodology discussion outlines the use of Smart PLS-SEM for analyzing data gathered from the designated respondents to test the proposed hypothesis. The following tables provide the results, highlighting the specified numerical distribution. The reflecting latent variables in the structural models were examined before the implementation of regression analysis. A measuring model with substantial reliability and validity. This foundation may lead to conceptions that are difficult to comprehend and may foster deceptive relationships. Table 1 presents a compilation of commonly used criteria for evaluating PLS-SEM measurement models.

To evaluate the reliability of a reflective factor solution, this research adopted the commonly used three key indicators: Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability. AVE reflects how much of the variance in the indicators was captured by the underlying latent variable, and this should ideally be greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2007, p. 605). Cronbach’s alpha measures the internal consistency of the indicators, with values above 0.70 considered acceptable (Malhotra 2010, p. 287). Composite reliability, which assesses internal consistency like Cronbach’s alpha but is not influenced by the number of indicators (with rho_a and rho_c), should be at least 0.80 for models with around five to eight items (Natemeyer et al., 2003). In this study, all five measures exceeded their respective thresholds for each latent variable, indicating that the measurement model has strong reliability. In alignment with this, it can be seen that help-seeking, adjustment, affective factors, workload, and general measures of academic performance achieved a reliability coefficient (CR (rho_a) of 0.936, 0.946, 0.903, 0.956 and 0.947). In contrast, the CR (rho_c) values were 0.948, 0.952, 0.927, 0.964, and 0.950, corresponding to help-seeking, adjustment, affective factors, workload and general measures of academic performance. The AVE values were also noted as 0.785, 0.800, 0.718, 0.844 and 0.659, respectively. Thus, all constructs successfully met the AVE criterion, with values greater than 0.5, demonstrating strong convergent validity. Additionally, the Cronbach’s Alpha values for all constructs were above the 0.7 threshold. (Cortina, 1993, Field, 2017). Thus, in totality, this highlights excellent internal stability and reliability and as such, the data are suitable for use in multivariate statistics.

The Fornell-Larcker criteria (1981) evaluate discriminant validity. A construct is unique when its Average Variance Extracted (AVE) surpasses the correlation it shares with other constructs. Simply put, a construct should be more closely related to its own measurements than to those of other constructs in a model. In Table 2 the diagonal entries show the square roots of the AVEs. The table also shows the bivariate correlation coefficients (the average correlations between each construct and its indicators). The results verify the model’s discriminant validity by showing that every construct’s AVE square root exceeds its correlations with other constructs, signifying that all the indicators propose separate concepts.

By examining the mean correlations across different constructs and within the same construct, the HTMT-ratio offers a different approach for evaluating discriminant validity. Values below 0.90, but specifically below 0.985 signify acceptable validity although some variables are marginal exceeding the lower margin of 0.85 (see Table 3). The General Means of Academic Performance correlates with Affective Factors, with 0.913, Affective Factors correlate with Adjustment with 0,861 and Help-Seeking correlates with Affective Factors, having 0,862. The results also indicates that discriminant validity is largely acceptable; however, some HTMT values (e.g., GMAP–Affective Factors = 0.913) are close to or slightly exceed the 0.90 threshold, suggesting a degree of conceptual overlap between certain constructs that should be acknowledged. However, all of them have values below the upper HTMT threshold of 0.985 As such, all the variables are acceptable and have satisfactory validity. This finding supports the AVE analysis on construct validity. In the next stage of analysis, the regression weights of the inner model are interpreted and linked to the latent constructs and their respective related observable variables. These values are in Tables 4, 5 while model fit is shown in Table 6.

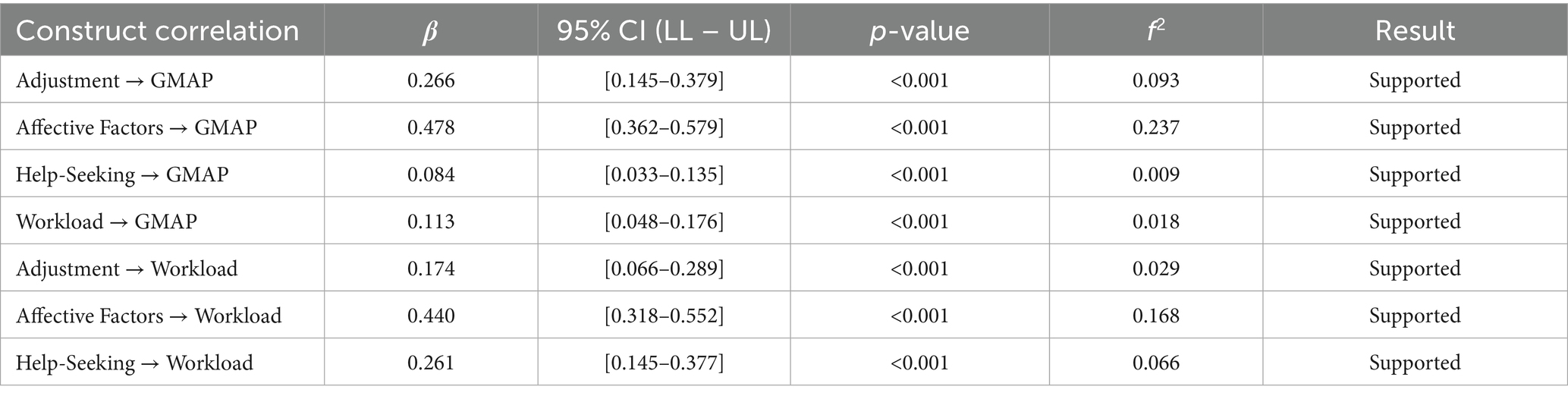

Table 4. Regression weights and statistical significance p-value for the structural models in the complete sample.

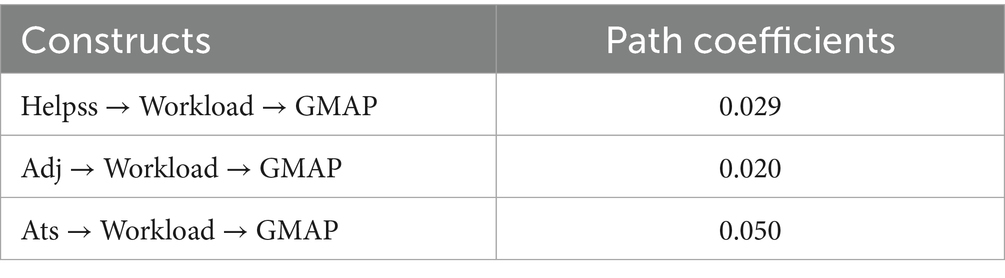

Table 5. Regression weights and Statistical significance p-value for the structural indirect effects models in the complete sample.

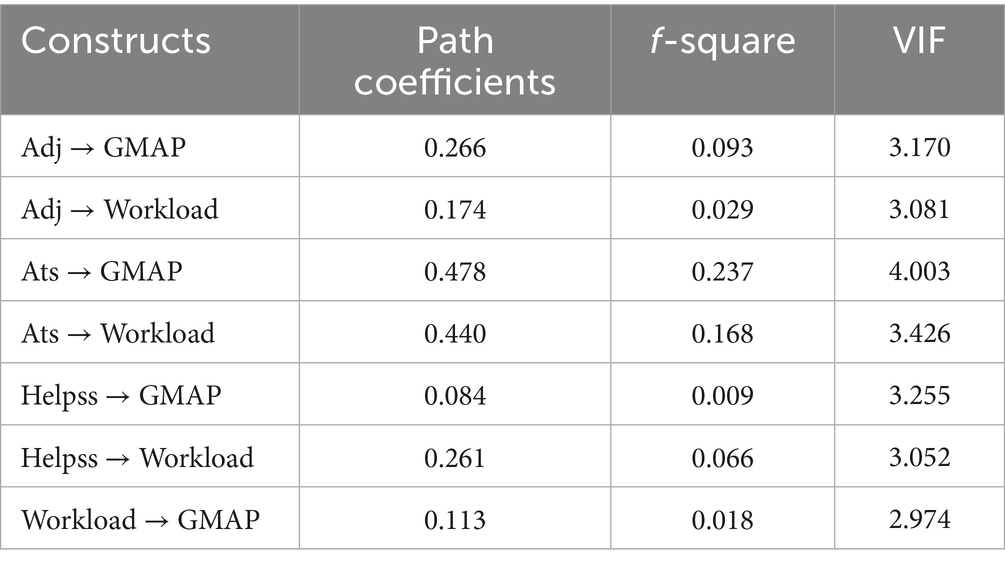

The results of the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis reveal several important relationships among the constructs examined. Affective Factors (Ats) demonstrate the most substantial direct influence on General Means of Academic Performance (GMAP), with a path coefficient of 0.478 and a large effect size (f2 = 0.237). Ats also strongly predicts workload (β = 0.440, f2 = 0.168), suggesting that individuals who hold a more positive attitude toward receiving support tend to report higher levels of workload, which in turn influences their performance outcomes. Adjustment (Adj) is positively associated with GMAP (β = 0.266, f2 = 0.093) and Workload (β = 0.174, f2 = 0.029), although these effects are smaller in magnitude. Help-seeking support (Helpss) shows a moderate direct effect on Workload (β = 0.261, f2 = 0.066), but its direct influence on GMAP is minimal (β = 0.084, f2 = 0.009), indicating a more indirect contribution.

Workload has a small but positive direct effect on GMAP (β = 0.113, f2 = 0.018), suggesting that increased Workload can slightly enhance performance, possibly due to engagement or perceived responsibility. The mediation analysis further reveals that Workload partially mediates the effects of the three main predictors on GMAP. Specifically, the indirect effect of Ats on GMAP through Workload is the strongest (β = 0.050), followed by Helpss (β = 0.029) and Adj (β = 0.020). These mediated paths suggest that while the constructs may directly influence GMAP, part of their impact is channeled through their effect on Workload. Finally, the model shows acceptable collinearity levels, with all Variance iInflation Factor (VIF) values below 5, indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern in this analysis.

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value of 0.057 is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.08, indicating only a minimal discrepancy between the observed and predicted correlations. This result suggests a good overall model fit and lends further support to the reliability and adequacy of the structural equation model. Convergent and discriminant validity are confirmed through AVE and HTMT (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Extracted PLS- SEM Model. Where: Helpss, Help- Seeking; Adj, Adjustment; Ats, Affective Factors; Workload, Employee Workload; GMAP, General Means of Academic Performance.

4.1 Hypothesis testing

The structural model provides compelling insights into the help-Seeking pathways that influence academic performance. Specifically, the PLS-SEM analysis employed 5,000 bootstrap resamples with bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) 95% confidence intervals. Help-seeking exhibited a significant positive impact on students’ overall academic performance (β = 0.084, f2 = 0.009, VIF = 3.255, p < 0.001), suggesting that students who proactively pursue assistance, be it from peers, instructors, or support services generally achieve modest but substantial enhancements in their academic results. Despite the modest impact size, the statistical significance highlights the necessity of cultivating a learning environment that normalizes and promotes help-seeking behavior. This activity demonstrates proactive learning attitudes, academic resilience, and a readiness to address knowledge deficiencies, all of which collectively contribute to sustained academic achievement. The discovery supports comprehensive educational perspectives that view help-seeking as a strategic, self-regulated learning activity linked to academic achievement.

Help-seeking shows a substantial positive impact on perceived Workload (β = 0.261, f2 = 0.066, VIF = 3.052, p < 0.001), indicating that students who proactively pursue academic assistance may develop greater awareness of or involvement in their academic obligations. Although this may initially appear paradoxical, the outcome suggests that asking for assistance may improve students’ comprehension of academic standards, enabling them to better grasp tasks and deadlines. In this framework, Workload is perceived not as a hardship but as an indication of active academic involvement. This supports the idea that requesting assistance enhances cognitive clarity and organizational preparedness, enabling students to negotiate and manage their academic responsibilities more effectively.

Adjustment exhibited a positive and statistically significant impact on students’ overall academic performance (β = 0.266, f2 = 0.093, VIF = 3.170, p < 0.001), suggesting that students who effectively acclimate to the academic, social, and emotional challenges of their educational setting are likely to attain superior performance results. This outcome underscores the essential function of adaptation in fostering academic achievement, particularly in dynamic or demanding environments. The modest impact size underscores that the capacity to adapt, whether by managing stress, navigating new learning methods, or assimilating into institutional culture equips students’ with the resilience and stability essential for academic success. This conclusion corresponds with existing literature on student transition and adjustment, which asserts that academic achievement is influenced not just by cognitive talents but also by emotional and behavioral flexibility.

Furthermore, Adjustment demonstrated a substantial positive impact on students’ perception of Workload (β = 0.174, f2 = 0.029, VIF = 3.081, p < 0.001), indicating that students who are more adept at acclimating to the academic environment are more inclined to acknowledge and interact with their academic responsibilities in a systematic and significant manner. This outcome suggests that Adjustment may improve students’ ability to organize, analyze, and address academic demands, thereby augmenting their knowledge and ownership of workload duties. Instead of viewing Workload as burdensome, well-adjusted students may regard it as manageable and essential to their academic progression. The study corroborates the view that emotional and behavioral adaptability improves students’ preparedness to confront academic obstacles proactively.

Affective factors exhibited a robust and statistically significant positive influence on overall academic performance (β = 0.478, f2 = 0.237, VIF = 4.003, p < 0.001), suggesting that students’ emotional states including motivation, interest, self-confidence, and attitudes toward learning substantially contribute to academic achievement. This substantial effect size highlights the significant impact of emotional involvement on cognitive function and academic results. Students with strong emotional dispositions are more likely to engage with learning assignments enthusiastically, persistently, and purposefully, thereby enhancing their academic achievements. This finding supports the idea that fostering emotional well-being and positive academic emotions is essential for helping students achieve at a high level.

Affective factors demonstrated a significant positive influence on perceived workload (β = 0.440, f2 = 0.168, VIF = 3.426, p < 0.001), indicating that students with heightened emotional engagement and favorable attitudes toward learning are more inclined to perceive and approach academic tasks with increased involvement and accountability. This significant effect suggests that emotionally engaged students may perceive workload not as a burden but as a valuable aspect of their academic experience. Their intrinsic desire and positive emotions may enhance their focus on academic requirements, leading to a greater sense of effort through active engagement. This finding supports the idea that fostering emotional well-being and positive academic emotions is essential for helping students achieve at a high level.

Notably, workload exhibited a substantial positive influence on overall academic performance (β = 0.113, f2 = 0.018, VIF = 2.974, p < 0.001), indicating that students who perceive their workload as manageable and stimulating are more likely to achieve superior academic results. Despite the small sample size, the statistical significance suggests that well-structured and intentional academic assignments can enhance students’ concentration, discipline, and perseverance. A challenging task can motivate students to put in effort and work toward their goals, rather than being seen only as a source of stress. This study suggests that meaningful academic engagement helps students succeed, especially when they have clear guidance and adequate support.

Workload mediated the effect of help seeking on global academic performance to a small but meaningful extent (β = 0.029, p < 0.001). This supports previous research that found students actively seeking help are more capable of controlling and organizing their academic duties and are therefore performing better. Despite its small indirect effect, the results emphasize the relevance of promoting help-seeking to facilitate improved workload management and academic achievement.

Adjustment exerted a small but significant indirect effect on GPA via workload (β = 0.020, p < 0.001). It suggests that if students can successfully adjust to academic and environmental challenges, they will be better equipped to manage workload, which has positive consequences for performance. Even if the indirect effect is small, it emphasizes that successful adaptation permits greater engagement with workload and thus condones improved academic performance. This discovery highlights the mediating role of workload in the relationship between student adaptation and academic achievement.

Affective variables demonstrated a favorable indirect effect on overall academic performance (β = 0.050, p < 0.001) by influencing workload. This suggests that students’ emotional involvement and favorable attitudes toward learning improve academic achievement by influencing their perception and management of academic burden. The moderate indirect impact size highlights the significant mediating function of effort in connecting affective preparation to enhanced academic achievement. This discovery underscores the interrelation of emotional elements and cognitive involvement in promoting student achievement. In summary, the result is presented in the Tables 7, 8.

4.2 Direct effects

The results showed that Adjustment (β = 0.266, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.093), Affective Factors (β = 0.478, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.237), Help-Seeking (β = 0.084, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.009), and Workload (β = 0.113, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.018) all had significant positive effects on general measures of academic performance (GMAP). In addition, Adjustment (β = 0.174, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.029), Affective Factors (β = 0.440, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.168), and Help-Seeking (β = 0.261, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.066) significantly predicted Workload, indicating their relevance as antecedents of students’ performance-related stress conditions.

4.3 Indirect effects (mediation)

Bootstrapping results also confirmed significant indirect pathways through Workload. Adjustment influenced GMAP indirectly via Workload [β = 0.020, 95% CI (0.009–0.034), p < 0.001]. Similarly, Affective Factors showed an indirect effect on GMAP through Workload [β = 0.050, 95% CI (0.025–0.078), p < 0.001]. Help-Seeking likewise exhibited a significant indirect effect through Workload [β = 0.029, 95% CI (0.012–0.047), p < 0.001].

4.4 Model fit and predictive power

The model demonstrated acceptable explanatory power, with the endogenous construct GMAP yielding a substantial R2 value. GMAP achieved an R2 of 0.760 (Adjusted R2 = 0.755), indicating that 76% of its variance is explained by the predictors. Workload yielded an R2 of 0.664 (Adjusted R2 = 0.659), confirming strong predictive accuracy. The f2 effect sizes further indicated that Affective Factors had the largest contribution, followed by Adjustment and Help-Seeking, while Workload exerted smaller yet significant effects and is positively associated with academic performance, suggesting that when adequately supported, higher perceived workload may reflect deeper engagement.

Overall, these results provide strong evidence that staff-perceived student adjustment, affective regulation, help-seeking behaviors, and workload jointly shape the academic performance environment within private tertiary institutions.

5 Discussion

This study examined how help-seeking behavior, adjustment, affective factors, and workload interact to influence students’ academic performance, using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The results offer valuable insights into how these psychological and behavioral factors collectively shape students’ General Means of Academic Performance (GMAP).

Affective factors, of the predictors investigated, were related to academic performance directly and indirectly through workload. This points to the saliency of emotions and socio-psychological context for learning. In line with the self-regulated learning literature and the stress–coping model, a supportive emotional climate appears to reduce cognitive load, enhance persistence, and facilitate learning-relevant behavior.

These results are consistent with the research in post-secondary education. For example, Lo and Punzalan (2025) carried out a study about Positive Psychology interventions with the teachers of languages in East Asian universities. They found that strategies such as mindfulness, gratitude, and resilience training bolstered stress management skills, enhanced relationships with colleagues, and created a more positive classroom climate. It is indicated that the more employees prioritize good feelings and emotional recognition at the institution, the more positive a university climate is produced, making it easier for students to adapt and seek help there.

Workload can serve as an expression of heightened student engagement if, in doing so, resources and support are provided (Bisschoff et al., 2024). Additionally, excessive demands may result in stress, burnout, and impaired performance (da Conceição et al., 2024; Kong et al., 2025). These findings highlight that the effect of workload depends heavily on context, indicating it can either enhance or hinder academic success.

Overall, the results show that academic performance is not only dependent on cognitive or workload factors but also on affective/environmental features steered by most variables analysed by staff practices. This has implications for university practice; institutions should consider the development of a staff well-being program, the embedding of culturally congruent emotional support mechanisms, and creating environments that promote resilience. As Lo and Punzalan (2025) show, such interventions are possible and have a powerful effect at higher levels of education; this finding is also consistent with the present evidence that affective factors explain 31% of outcomes.

5.1 Direct effects on academic performance

Among the predictors, Affective Factors (attitude toward support) emerged as the strongest determinant of academic performance (β = 0.478, f2 = 0.237, p < 0.001), highlighting the crucial role of students’ emotional engagement and motivational orientation. This implies that students who perceive institutional and peer support positively are more likely to achieve better academic outcomes. The strong effect size reinforces the value of fostering supportive academic environments that build emotional confidence.

Adjustment also significantly influenced academic performance (β = 0.266, f2 = 0.093, p < 0.001). This suggests that students who can effectively adapt to academic pressures, routines, and transitions tend to perform better. Programs that support students’ adjustment, such as orientation, counseling, and mentorship may therefore yield tangible performance benefits.

Although Help-Seeking Behavior had the smallest direct effect on GMAP (β = 0.084, f2 = 0.009, p < 0.001), its significance underscores that even modest efforts by students to seek assistance whether academic or emotional can positively influence performance. This reinforces the importance of accessible academic support services and promoting a help-seeking culture among students.

5.2 Direct effects on workload

All three exogenous constructs (Help-Seeking, Adjustment, and Affective Factors) had significant positive effects on Workload, with affective factors having the highest impact (β = 0.440, f2 = 0.168, p < 0.001), followed by Help-Seeking (β = 0.261, f2 = 0.066) and Adjustment (β = 0.174, f2 = 0.029). These results suggest that students who are emotionally engaged and well-adjusted, as well as those who actively seek help, are more likely to undertake greater academic tasks and responsibilities. This may reflect deeper academic involvement, suggesting that workload is not merely a burden but also a signal of active student engagement.

5.3 Workload’s role in academic performance

Interestingly, Workload itself had a significant, albeit small, positive effect on GMAP (β = 0.113, f2 = 0.018, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that increased workload, when managed effectively, may contribute to academic success. It challenges the assumption that high workload is inherently negative and highlights the importance of balancing task demands with students’ capabilities and support mechanisms.

5.4 Mediated effects through workload

The model also reveals several significant mediation paths, showing that workload acts as a partial mediator in the relationship between the exogenous constructs and GMAP.

• Affective Factors had the strongest indirect effect on GMAP through workload (β = 0.050, p < 0.001), reinforcing the idea that students with positive attitudes toward support not only perform better directly but also do so by engaging more intensely in academic tasks.

• Help-Seeking Support also exhibited an indirect effect (β = 0.029, p < 0.001), indicating that students who seek support are likely to take on more workload, which in turn boosts their academic performance.

• Similarly, Adjustment showed a smaller but still significant indirect influence on GMAP via workload (β = 0.020, p < 0.001), suggesting that well-adjusted students are more inclined to be actively involved in their studies, which supports better outcomes.

These mediation results provide a more nuanced understanding of the pathways through which psychological and behavioral factors contribute to academic performance. They suggest that while attitudes, behaviors, and adaptability are directly important, their effects are also transmitted through students’ academic engagement (i.e., workload).

6 Conclusion

This study examined staff-reported perceptions of students’ help-seeking, adjustment, affective factors, workload, and academic performance within two private business institutions.

Of these factors, affective elements, in particular positive orientations toward support, proved to be the strongest predictor for academic performance and therefore emphasized the necessity of emotionally supportive contexts that enhance students’ self-assurance and motivation. Coping strategies were also a significant factor, highlighting the importance of orientation programs, counselling services, and mentorship for students in balancing academic demands.

Help-seeking was the least direct effect, but crucial; it is necessary to promote and encourage students to utilize support. Workload (considered as academic engagement rather than burden) would have some positive effect on performance, also. Moreover, it played a complementary role in the process of predicting the effect of affective factors, adjustment, and help-seeking on academic outcomes. These data may indicate that affective factors and adjustment matter most for student success, while workload carries a slightly different effect on engagement when enough support is in place. As a cross-sectional study, these findings should be considered as associations, not causations.

Overall, the results suggest that fostering supportive academic climates, strengthening students’ adaptive capacities, and normalizing help-seeking behaviors not only enhance immediate performance but also promote deeper engagement with learning tasks. These insights provide practical implications for educators, administrators, and policymakers seeking to design interventions that holistically support student success.

7 Limitations

There are several methodological issues with the current study that should be noted to guide future research and build a stronger body of evidence. First, the study’s focus on private schools makes it more challenging to generalise the results to other situations. Compared to public organizations, private ones generally have distinct ways of running things, distributing resources, and meeting the needs of stakeholders. Because of this, the experiences and impressions presented here may not fully represent what occurs in public institutions, where bureaucratic rules and larger social and political factors often have a greater impact. Adding both private and public organizations to future research would help to create a more balanced perspective and make the information more useful to people outside of the study. Second, the cross-sectional study approach is well-suited for identifying patterns and connections at a specific moment in time, but it does not allow for determining the cause of these patterns. Temporal factors or unmeasured confounders may influence the correlations observed between variables, making it challenging to determine the direction or stability of these interactions. Longitudinal or experimental designs are recommended to address this issue, as they enable researchers to observe how relationships evolve over time and whether specific actions result in measurable change.

Furthermore, this study was framed within the Self-Regulated Learning and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which provided a strong foundation for examining staff-reported perceptions of students’ help-seeking, adjustment, affective factors, workload, and academic performance. Nonetheless, emerging perspectives such as Positive Psychology (PP) may serve as a complementary lens to extend this work. PP interventions, such as mindfulness, gratitude, and resilience training have been shown to enhance affective well-being, stress management, and professional relationships, thereby fostering more supportive educational environments.

Finally, the absence of qualitative data means that we missed the opportunity to examine the deeper psychological, emotional, and environmental factors that influenced how participants responded. Quantitative approaches are effective for identifying patterns and basic trends, but they may overlook the lived experiences, nuanced perspectives, and subjective interpretations that influence people’s actions. Using interviews, open-ended questions, or ethnographic methodologies in future research may disclose a wealth of useful information about people’s motives, anxieties, or faith in institutions that numbers alone cannot reveal. By fixing these problems, future research can provide us a better, more complete, and more reliable knowledge of the things we are studying.

7.1 Practical implication

The results highlight the role of staff-perceived affective and adjustment factors in student academic performance, with workload being presented as a challenge and an opportunity for engagement. Building on works on higher education by Lo and Punzalan (2025), the institutions may implement low-cost Positive Psychology (PP) inspired initiatives to create more supportive and emotionally enriched settings. Brief gratitude or mindfulness exercises at the start of lectures or tutorials, for example, can help to shape workload as a meaningful challenge rather than a threat. Positive feedback workshops for staff and cross-disciplinary communities of practice between academic and support staff might also increase resilience and collegiality, benefitting student psychosocial climate.

Given that the present study focused on staff perceptions in private institutions, the cultural and institutional tailoring emphasized by Lo and Punzalan (2025) is particularly relevant. Tailored PP programmes that align with local culture, resource constraints, and institutional priorities may maximize impact. Future pilots embedded with evaluation components are recommended, not only to assess effectiveness but also to capture potential differences across public and private institutions, as well as across disciplines.

7.2 Future research

Future longitudinal studies should reveal how the subject evolves and grows. Longitudinal studies demonstrate how things evolve, particularly in response to policy or institutional changes, more effectively than cross-sectional research. Looking at objects from this angle may reveal patterns, such as cumulative or later consequences. This can help you grasp the idea and perform more effectively.

Future studies could also extend the present findings by examining whether PP-informed institutional practices enhance staff and student well-being, thereby influencing perceptions of help-seeking, adjustment, workload, and performance. Such integration would provide a more holistic understanding of how psychosocial and affective mechanisms jointly shape academic success.

Mixed-methods or the employment of longitudinal research is also advised. By employing both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, researchers can uncover hidden beliefs, contextual nuances, and underlying reasons that statistics miss. This could also be a pathway to encourage the testing of these relationships more robustly and to clarify the mechanisms underlying staff perceptions of student performance. Survey data may reveal trends in stakeholder involvement or institutional support, but in-depth interviews or focus group discussions can provide a deeper understanding of the emotional, cultural, and experiential aspects of these interactions.

We need more full, open example frameworks in the end. Modern research may overlook vital perspectives by focusing on specific institutions or places. Public institutions, underrepresented geographical areas, and culturally diverse populations would make policy recommendations more generalizable, while also taking into consideration local conditions. This inclusive approach recognizes that society is made up of diverse groups and allows for more fair and relevant findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethical Committee of North-West University (Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

CB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ridwaan Asvat, and Sayed Rehman who provided the data for the study. This comes as a deep reflection of the notice of the meticulous gathering of the data and its current usability. The authors wish to acknowledge the management of Northwest Business school for the support and the APC of the article. There is no competing interest. The data are available upon request. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Basith, A., Syahputra, A., Fitriyadi, S., Rosmaiyadi, R., Fitri, F., and Triani, S. N. (2021). Academic stress and coping strategy in relation to academic achievement. Cakrawala Pendidikan 40, 292–304. doi: 10.21831/cp.v40i2.37155

Bimerew, M. S., and Arendse, J. P. (2024). Academic help-seeking behaviour and barriers among college nursing students. Health SA Gesondheid 29, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v29i0.2425

Bisschoff, C. A., Kamoche, K., and Wood, G., (2024). The formal and informal regulation of labour in AI. SAGE Open, 14, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/00197939241278956

Cassim, N., Botha, C. J., Botha, D., and Bisschoff, C. (2024). The organisational commitment of academic personnel during WFH within private higher education, South Africa. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 50:2123. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v50i0.2123

Cheng, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, H., and Liu, Q. (2019). Input and output data [Data set]. U.S. Department of Energy. doi: 10.25584/data.2020-02.1114/1597292

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98–104. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

da Conceição, V., Mesquita, E., and Gusmão, R. (2024). Effects of a stigma reduction intervention on help-seeking behaviors in university students: a 2019-2021 randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 331:115673. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115673

Davison, K. T., Malmberg, L.-E., and Sylva, K. (2023). Academic help-seeking interactions in the classroom: a microlongitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 93, 33–55. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12538

Dent, A. L., and Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 425–474. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dueñas, J.-M., Stepanovic Ilic, I., Moya, M., Krstić, K., and Martín-Arbós, S. (2025). What They Think of Me and What I Think of Myself: Social Influences on Academic Self-Concept in Adolescence. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 1–15. doi: 10.17583/remie.17779

Fan, Y. (2025). Investigating the relationship between family socioeconomic status and online academic help-seeking behaviours: internet self-efficacy as a mediator. Int. J. Educ. Res. 130:102530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102530

Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes, it must be a process: a study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 150–170. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. L. (2007). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harmon, M. D., and Hunter, K. (2025). Uplifting our voices: centering black women pre-service teachers in teacher education research. Int J Qual Methods 24:16094069251331351. doi: 10.1177/16094069251331351

Harvey, A., Brown, T., and Lawson, J. (2025). Reflecting on reflective practice: Issues, possibilities, and guidance principles. Higher Education Research and Development, 44, 832–846. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2025.2463517

Kaymakcioglu, A. G., and Thomas, M. (2024). Gender inequalities and academic leadership in Nigeria, South Africa and the United Kingdom: a systematic literature review (2013–2023). Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 10:101066. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.101066

Kong, S. C., Lin, T. J., and Siu, Y. M. K. (2025). The role of perceived teacher support in students’ attitudes towards and flow experience in programming learning: a multi-group analysis of primary students. Comput. Educ. 228:105249. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2025.105249

Lo, N., and Punzalan, C. (2025). The impact of positive psychology on language teachers in higher education. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 22, 1–19. doi: 10.53761/5ckx2h71

López Flores, N. G., Óskarsdóttir, M., and Islind, A. S. (2025). Supporting teachers in higher education: design of an institutional programme from a socio-technical perspective. J. Workplace Learn. 37, 219–236. doi: 10.1108/JWL-09-2024-0219

Martín-Arbós, S., Castarlenas, E., and Dueñas, J.-M. (2021). Help-seeking in an academic context: a systematic review. Sustainability 13:4460. doi: 10.3390/su13084460

Mwale, M., Banda, T., and Phiri, J. (2023). The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation on SME performance in Southern Africa. Journal of African Business, 24, 287–305.

Natemeyer, W. E., McMahon, J. T., and Hersey, P. (2003). Classics of organizational behavior (3rd ed.). Waveland Press.

Nwadi, C., Okafor, E., Olatunde, A., and Dlamini, S. (2025). Impact of cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction in reducing test anxiety among university students: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Medical Education, 25:7130. doi: 10.1186/s12909-025-07130-w

Ojo, O. (2014). Organizational culture, and performance. Empirical evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Business systems governance and ethics. 5. doi: 10.15209/jbsge.v5i2.180

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 8:422. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Ponto, J. (2015). Understanding and evaluating survey research. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, 6, 168–171. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4601897/

Rehman, S., Bisschoff, C. A., and Botha, C. J. (2019). A model to measure academic performance of private higher education institutions. J. Contemp. Manag. 16, 178–200. doi: 10.35683/jcm19064.32

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2019) Research Methods for Business Students. 8th Edition, Pearson, New York.

Shanahan, L. (2021). Understanding help-seeking and stigma in university students: a review. Educ. Res. Rev. 32:10039. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2021.10039

Sithaldeen, R., Phetlhu, O., Kokolo, B., and August, L. (2022). Student sense of belonging and its impacts on help-seeking behaviour. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 36, 67–87. doi: 10.20853/36-6-5487

Tinto, V. (2017). Through the eyes of students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 19, 254–269. doi: 10.1177/1521025115621917

Tshivhase, M. L., and Bisschoff, C. A. (2024). Investigating green initiatives at south African public universities. Nurture 18, 245–263. doi: 10.55951/nurture.v18i2.599

Umar, Z., Ahmad, S., Khokhar, M., and Khan, N. (2023). Phenobarbital and alcohol withdrawal syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus, 15:e33695. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33695

Wang, G.-Y., Hatori, Y., Sato, Y., Tseng, C.-H., and Shioiri, S. (2025). Predicting learners’ engagement and help-seeking behaviors in an e-learning environment by using facial and head pose features. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 8:100387. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2025.100387

Keywords: academic performance, adjustment, help-seeking, structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), student performance

Citation: Bisschoff C and Ayeni AAW (2025) Assessing the impact of staff-reported perceptions of students’ helping-seeking and adjustment on academic performance of students: a case of selected tertiary institutions. Front. Educ. 10:1670588. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1670588

Edited by:

Ramon Ventura Roque Hernández, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, MexicoReviewed by:

John Mark R. Asio, Gordon College, PhilippinesNoble Lo, Lancaster University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Bisschoff and Ayeni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christo Bisschoff, Y2hyaXN0by5iaXNzY2hvZmZAbnd1LmFjLnph; Adebanji Adejuwon William Ayeni, YWRlYmFuamlheWVuaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Christo Bisschoff

Christo Bisschoff Adebanji Adejuwon William Ayeni

Adebanji Adejuwon William Ayeni