- Department of Educational Studies, Reno College of Education & Human Development, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, United States

The purpose of this study was to examine academic and personal variables as predictors of degree completion within 150% of the normal time for students participating in the federally funded Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR UP) grant. The study aimed to identify which factors most strongly influenced college completion among students traditionally placed at risk. Academic and personal variables analyzed included 12th-grade GPA, 7th-grade college aspirations, cumulative GEAR UP program service hours, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity. A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which these variables predicted timely college completion. The resulting model identified 12th-grade GPA and cumulative GEAR UP program service hours as significant predictors of degree completion within 150% of normal time. Students with higher GPAs and greater participation in GEAR UP programming were more likely to graduate on time. Findings suggest that sustained academic performance and engagement in GEAR UP services contribute meaningfully to college completion among students from historically underrepresented groups. Implications for program design and recommendations for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Providing support for individuals to attain a college education is recognized as an effective strategy for facilitating upward, intergenerational social and economic mobility (Chetty et al., 2017). This is particularly important for GEAR UP, in support of students placed at risk who can get programming toward college degree completion. Individuals with some college attendance or a college degree have, on average, higher annual median incomes and lower unemployment rates than individuals with a high school degree or less (Hussar et al., 2020). The recognition of the strength of a college education in positively impacting the lives of students, their families, and their communities has led to major investments from federal, state, and local governments; non-profit and non-governmental organizations; and private citizens and foundations (Kuenzi, 2005; Redden, 2021; U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

Despite the well-established benefits of a college education vast disparities in rates of postsecondary enrollment and completion exist amongst groups with differing backgrounds. Specifically, students from low-income households are far less likely to be prepared for or attend college, more likely to attend undercapitalized or less selective institutions and/or drop out quickly if they do attend, and graduate at rates significantly lower than individuals from more advantaged households (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.; Engle and Tinto, 2008; Horn, 2006; Nellum and Hartle, 2016; Rowan-Kenyon, 2007). While recent reports have indicated an increase in the number of students from low-income families that are attending college since the mid 1990’s, “these changes are not occurring uniformly across the postsecondary landscape. The rise of poor and minority students has been most pronounced in public two-year and the least selective four-year colleges and universities” (Pew Research Center, 2019, p. 3). As more selective institutions are often associated with higher rates of student success, such as increased degree completion, this disparity means that the increase in low-income student college enrollment may not be resulting in the increased social mobility and economic stability associated with degree attainment.

It is important to better understand the factors that may be contributing to students from low-income backgrounds having lower rates of postsecondary enrollment or completion in order to enhance program designs to address these discrepancies. However, complicating any investigation into the enrollment and completion rates of students from low-income backgrounds are the multitude of factors that have been found to impact rates of college enrollment. These factors include, but are not limited to gender, race or ethnicity, geographic location of elementary and secondary schools, academic rigor of pre-college coursework, and awareness of college opportunities. Studies that include factors beyond a student’s income level have the ability to provide more robust data to individuals and organizations that are developing and refining programs designed to serve students at risk of not attending or completing college. One such program that can benefit from an increased availability of data is the federally-funded Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR UP) program. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine which academic and personal variables, if any, can predict whether GEAR UP eligible students that enroll in college complete postsecondary education and obtain a college degree within 150% of the normal time to degree completion.

The context of GEAR UP

The following sections provide an overview of the GEAR UP program, including governing legislation, the rationale for program design, and a summary of available research that evaluates the success of this program in meeting its stated objectives. The GEAR UP program was first authorized in the 1998 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (1965). The 1998 authorization supports the establishment of a program that (1) encourages eligible entities to provide or maintain a guarantee to eligible low-income students who obtain a secondary school diploma (or its recognized equivalent), of the financial assistance necessary to permit the students to attend an institution of higher education; and (2) supports eligible entities in providing: (a) additional counseling, mentoring, academic support, outreach, and supportive services to elementary school, middle school, and secondary school students who are at risk of dropping out of school; and (b) information to students and their parents about the advantages of obtaining a postsecondary education and the college financing options for the students and their parents (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

Although the original authorization has been amended several times, primarily in 1999 and 2008, the focus, required services, target population, and eligible organizations have stayed consistent with the original authorization (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs, 2008). The following descriptions of the GEAR UP program, which are consistent with the scope of funded awards made since the program’s inception. The GEAR UP program offers competitive grants for two types of awardees, both of which are “designed to increase the number of low-income students who are prepared to enter and succeed in postsecondary education” (U.S. Department of Education, 2021).

The first type of award is made to states and funds six-year matching grants that provide early intervention services designed to raise the college expectations of low-income students, increase their college enrollment and success, and provide scholarships to eligible students. States may only have one active GEAR UP grant at a time; states may only apply for new GEAR UP awards if they do not currently have an active award, or if that award will end prior to the funding start date of the new grant. The second type of award is made to partnerships consisting of at least one local education agency and at least one degree-granting institution of higher education and have the option of including community organizations. If opting to include community organizations, partnerships must include at least two separate organizations, which may be businesses, professional organizations, state agencies, or other public or private agencies or organizations. Awards to partnership applicants are also six-year matching grants that must include the same types of services described above for state grants, but partnerships may administer more than one active GEAR UP award at a time, although overlap between students and services between the awards is not allowed. Both types of grantees have the option to request a seven-year grant if they plan to provide services through the students’ first year of postsecondary education, and both grantee types must provide at least a 50% match to be considered eligible for funding, although partnership grantees may request a waiver of up 75% of the requirement based on circumstances and partnership composition.

Grant awardees have both required services that they must, and optional services that they may, include in their funded programming. Required services comprise providing postsecondary education financial aid information and postsecondary scholarships for in-state enrollment to participating and eligible students (scholarships are a requirement only for state grants, and grantees may elect to offer scholarships for students who attend institutions of higher education outside the state), encouraging students to enroll in rigorous coursework to reduce their enrollment in remedial education at the postsecondary level, and increasing the number of students who complete high school and apply and enroll for postsecondary education. Grantees use a combination of mentoring, outreach, and provision of supportive services to facilitate the latter program outcomes. Additionally, they may opt to customize their program to meet the needs of their target population, adding in services such as academic tutoring, college tours and job shadowing, and cultural enrichment content.

GEAR UP awardees also have flexibility in identifying their target audiences. The program has two implementation models: a cohort model and a priority student model. In the cohort model grantees begin offering services to all students in a particular grade that attend eligible schools (i.e., “originating school”), or that reside in public housing. Eligibility is determined by the percent of students enrolled in the originating school that are eligible for reduced-price or free lunch; at least 50% of the students must meet this criterion for the school to be eligible. Once school eligibility has been determined program services are available to all students in designated grade levels regardless of family income. The school must have a 7th-grade class, as projects must begin offering services to students by 7th-grade but may opt to begin services (i.e., start the cohort) with students in an earlier grade. Since grant services must be offered to students through their senior year of high school if part of a six-year grant, and through their first year of postsecondary if they are part of a seven-year grant, beginning services prior to grade seven may result in needing to serve students after the end of the GEAR UP funding award. Programs may serve students that have not completed high school by the end of the funding award term through a subsequent GEAR UP grant, but this is not recommended because there is a risk that an additional grant will not be awarded. Services must be provided to all students in the beginning grade (often, but not always, 7th-grade) at the originating school(s), and services must follow the majority of the cohort as they progress to high school.

An alternate to the cohort model is the priority student model, which allows programs to identify the criteria of their target audience. In this case, awardees prioritize offering services to secondary students who are low-income, have limited English proficiency, are experiencing homelessness or are in foster care, or are from other groups traditionally underrepresented in postsecondary education. Partnership awardees must utilize the cohort model, while states may utilize either the cohort or priority student model.

Rationale for program design

The GEAR UP program was specifically developed to “address the continuing imbalance in postsecondary enrollment rates by specifically promoting equal access to higher education for low-income students” (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service, 2008, p. 1). A key element of the program is its focus on the role of peers, which is supported through the development of cohorts either within a specific grade or by targeting subpopulations that share common characteristics. The use of peers and inclusivity was based on its use in other initiatives such as the I Have a Dream project, which, as of 2019, had reported that low-income participants in their college readiness programs had high school completion rates 16% higher than their non-participating, low-income peers, and were three times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree (I Have a Dream Foundation, 2021). GEAR UP also mandates some of the same best practices seen in TRIO programming, such as supporting secondary academic achievement and assisting with completion of financial aid and scholarship applications. The conceptual framework for the program highlights the involvement of, and provisioning of services to and with students, families, schools, and communities. Programs have the flexibility to implement services as they believe will best serve their target population, but it is anticipated that these services should be based on research-based best practices. If implemented as conceptualized, the expected interim or intermediate outcomes of the program are increased family, teacher, and student expectations and knowledge around college; increased secondary academic achievement; and collaboration with partner organizations. It is then expected that these interim outcomes support the long-term outcomes of increased college enrollment and success of participating students (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service, 2008).

GEAR UP program outcomes

In 2008, the U. S. Department of Education published the Early Outcomes of the GEAR UP Program report, which investigated the interim outcomes of the first cohort of students served via GEAR UP funds (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service, 2008). The evaluation included up to 140 students from each of 18 GEAR UP participating middle schools and up to 140 students from each of 18 non-GEAR UP participating middle schools. Evaluation activities took place during the 5 years following the initial grants, which began serving students in fall 1999. This evaluation could only report interim outcomes, as the high school graduation date, and thus anticipated postsecondary enrollment date, for members of the initially served cohort fell after the term of the evaluation. Although the sample size was relatively small and the authors noted that the results of this initial evaluation should not be considered definitive, they provide several key findings that speak to the initial success of the program and its impact on intermediate outcomes. The authors found that attending a GEAR UP school was positively associated with parents’ knowledge of the benefits of postsecondary education and opportunities available to their children, with parents’ involvement in the school and their children’s education, and with parents’ higher academic expectations for their children. Although there was no positive association between attending a GEAR UP school and the student’s college aspirations, there was a positive association with attending a GEAR UP school and student knowledge of postsecondary opportunities. There was also a positive association between attending a GEAR UP school and students enrolling in above-grade-level science courses in middle school. The report found that GEAR UP students and their parents had more knowledge of postsecondary education, parents of GEAR UP students had higher academic expectations for their children, and GEAR UP students were more likely to enroll in some more rigorous coursework, than similar parents and students at non-GEAR UP schools. As these factors are all associated with increased rates of college success, they indicated that initial GEAR UP efforts were supporting the long-term outcomes of the program to increase college entrance and completion of low-income students.

Other studies have supported these correlations between GEAR UP participation and the achievement of some intermediate outcomes. Bausmith and France (2012) found that program participation was associated with increases in college readiness as demonstrated by significant increases in PSAT and Advanced Placement course participation, but that participants failed to realize significant increases in performance within the PSAT and Advanced Placement courses. Leuwerke et al. (2021) compared secondary school data for over 30,000 GEAR UP and non-GEAR UP students, finding that GEAR UP participation had a significant effect on 10thgrade attendance and on 10th grade reading proficiency. They also found that low-income (as determined by Free or Reduced-Price Lunch eligibility) GEAR UP participants may benefit more from the program than their higher income peers, as students in the Free or Reduced-Price Lunch group demonstrated increased 10th grade math proficiency while their higher income peers did not. Both studies indicate mixed results of GEAR UP programming’s efficacy in achieving interim outcomes, but more recent studies have not been as ambiguous. Lunceford et al. (2017) compared both indicators of interim program success (i.e., secondary attendance, GPA, rates of behavior incidents, and high school graduation rates) and the long-term outcome indicator of college enrollment rates, between GEAR UP and non-GEAR UP participating students and found that GEAR UP students “performed significantly better on all measures” (p. 185). Similarly, a 2015 report published by the New England Board of Higher Education indicated that GEAR UP participants showed higher secondary persistence, high school graduation, and college enrollment rates than a comparison group (Fogg and Harrington, 2015).

The GEAR UP program mandates some program components and allows grantees flexibility in adding other components. Some studies have focused on identifying which of these optional and mandated program components are most linked to the anticipated outcomes of high school graduation and college success, in some cases with unexpected results. Dalpe (2008) found that over 50% of an eligible cohort did not access the postsecondary scholarship that was part of the GEAR UP program for this group. A possible rationale for this finding was tied to the timing of the funding, as this cohort did not receive GEAR UP services in their senior year of high school; without continued access to supportive services that encouraged completion of college applications, eligible students may not have applied to attend a postsecondary institution and therefore did not access the available scholarship funds. This shortfall in programming was resolved through subsequent GEAR UP legislation, which now provides funding for GEAR UP programming to be used through the senior year of high school, and in some cases the first year of college, and illustrates the importance of continued evaluation and program refinement.

Other studies have also focused on identifying the most impactful service components. A 2015 study focused on 294 GEAR UP students within one cohort found that participants had a high school graduation rate of 95%, compared to the average school rate of below 60%. When asked which program components had impacted their academic success and college aspirations, GEAR UP participants in the 12th grade indicated that college tours and fairs, test preparation, tutoring, and financial aid workshops had the greatest impact (Morgan et al., 2015). This aligns, in part, with other work done on the topic. An Iowa-based research team found that college visits, financial aid counseling, college campus activities, academic assistance, and ACT/SAT test preparation had positive associations with college enrollment of GEAR UP participants, while college visits and college campus activities had a positive effect on their college persistence (Kim et al., 2021). The authors noted that these college-based activities may increase persistence as they prepare students for the challenges and realities of college before they enroll.

Similar to Fogg and Harrington (2015), Lunceford et al. (2017), and Kim et al. (2021), recent research has moved beyond investigation of only interim outcomes and has included investigation of the primary goals of the GEAR UP program, namely college enrollment and college success. These studies have primarily been focused on the impact of GEAR UP programming on college enrollment and persistence and have not included postsecondary graduation as an outcome measure. Prior to the mid-2010’s literature on any postsecondary outcomes of GEAR UP students was more or less unavailable; a review of the available literature conducted by Knaggs et al. (2015) found eleven GEAR UP program evaluations available in peer reviewed journals or public reports. Of these, only one included college enrollment as an outcome measure and none included persistence or graduation. In response to this deficit Knaggs et al. evaluated the linkages between GEAR UP programming and college-related outcomes for one GEAR UP cohort, finding that GEAR UP participation was correlated with increased college enrollment and persistence, and with enrollment at more selective institutions. Of most relevance to the stated outcomes of the GEAR UP program, this study reported that low-income GEAR UP participants had significantly higher rates of college enrollment and persistence compared to low-income non-GEAR UP participating students, indicating that the program increases success for its target population in addition to increasing success for all participants. Similarly, Sanchez et al. (2016) found that GEAR UP did impact college persistence, as GEAR UP students were as likely to persist in college as their peers from less disadvantaged backgrounds enrolled at the same university. This is contrary to other research that found that the target population served by GEAR UP had lower rates of persistence when interventions were not provided. Conversely, Bowman et al. (2018), in their analysis of over 17,000 students found that “GEAR UP Iowa improved college enrollment rates shortly after high school graduation, but it did not contribute to college persistence” (p. 414). More recently, Sanchez and Mutiga (2024) identified that the GEAR UP program helped to tighten the aspiration-pursuit gap, with students in GEAR UP students having high college aspirations in their early adolescent years and then pursuing their goals through college completion. In their quantitative, exploratory study, 84% of the students completed a four-year postsecondary education.

Ultimately, while there are discontinuities visible in the available research regarding the impact of GEAR UP programming on specific indicators of college readiness and success, literature supports the finding that GEAR UP programming is helping participating students achieve college readiness and success through a variety of services. There is even some evidence that the efficacy of GEAR UP programming may be increasing over time with regards to college enrollment. The National Council for Community and Education Partnerships (2018) reported a 17.4% increase between 2011 and 2014 in the percentage of former GEAR UP high school graduates who immediately enrolled in college. However, it is clear from this review that research is lacking around the long-term program outcome of college success of GEAR UP students, particularly pertaining to college degree attainment. One group seeking to rectify this scarcity is the College and Career Readiness Evaluation Consortium (CCREC), a group comprised of 13 GEAR UP state grant projects that have agreed to adopt common data collection and evaluation practices. The CCREC has developed a research and evaluation framework, and plans to evaluate the postsecondary enrollment, persistence, and graduation of two longitudinal cohorts of students through FY2025 (National Council for Community and Education Partnerships, 2018).

The pre-2015 lack, and recent proliferation of studies that explore college outcomes is not surprising. The first cohort of GEAR UP students likely did not graduate high school until around 2005, and data on four-year college graduation would not have been available for four to six more years (based on 150% normal time to degree completion). Now, more efforts to examine this national investment should be reflected in the literature in order to explore the efficacy of this program and implement changes that can impact long-term outcomes of college enrollment, persistence, and graduation.

Postsecondary enrollment and completion factors in brief

It is important to make sense of key factors that may influence be related to a student’s postsecondary enrollment or completion, especially those that may relate to or interact with family income level, to enhance programming and increase the success of students from low-income backgrounds. As such, many studies have been conducted to determine the program factors, personal factors, and academic factors that are associated with college success. For instance, factors of college-readiness programs such as academic rigor of secondary courses, completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), smaller secondary class sizes, participation in structured youth development activities, and access to social capital are correlated with enrollment and/or completion rates (Belasco, 2013; Dynarski et al., 2013; Lapan and Poynton, 2020; Morgan et al., 2018). For this study, the primary college-readiness factor of concern was participation in structured activities through GEAR UP.

Educational aspirations

The U.S. Department of Education reported that the proportion of high school students that anticipated completing a college degree rose from 1980 through 2002, the most recent year these data were collected as part of the 2002 National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Education Longitudinal Study (ELS); in 2002, nearly double the percentage of 10th-graders reported that they expected to earn at least a bachelor’s degree compared to 1980, and over double reported that they planned to obtain a graduate degree (National Center for Education Statistics, 2004). Recent findings identify that college aspirations of high school-aged students are correlated with college enrollment rates when compared to students who do not aspire to attend college, with youth who develop a college-going identity being more likely to attend a postsecondary institution following high school. For example, in a study of 405 individuals found that students who had developed a college-going identity by the 10th-grade were more likely to decide to enroll, and then actually enroll, in a two- or four-year college upon graduation (Lapan and Poynton, 2020). These students had also taken more steps towards achieving this goal, such as submitting more college applications, enrolling in more advanced high school courses, and earning better grades during secondary school. There is also evidence that a higher-stated postsecondary goal is related to college enrollment; this same 2020 study found that high school seniors “were more likely to enroll in college if they set higher postsecondary goals for themselves” (Lapan and Poynton, 2020, p. 419). Similar work has noted that students aspiring to attend college while in high school increased the probability of enrolling in a postsecondary institution, with this effect being stronger in females than males (Christofides et al., 2015).

There is also evidence that establishing aspirations prior to high school can increase college enrollment. A longitudinal study of 681 students indicated that a youth’s plan for college as early as 6th-grade was a significant predictor of full-time college enrollment. In this study, students were asked to indicate if they planned to go to a four-year college after finishing high school; results indicated that “sixth-grade certainty of college plans predicted to college enrollment status even after [other factors] were controlled” (Eccles et al., 2004, p. 71). One of the factors that was controlled for was family income, as this study, consistent with other research, found that higher family incomes predicted college enrollment. With sixth-grade certainty of college enrollment being a predictor of college enrollment, even after family demographics were controlled for, Eccles et al. asserted that early college planning and encouragement to attend college could increase enrollment rates among all groups, including low-income students. Many studies have found that parent, family, and teacher expectations also have a strong influence on whether students develop and retain aspirations to attend college (Mitchall and Jaeger, 2018; National Center for Education Statistics, 2001; Turner et al., 2019), supporting Eccles et al.’s (2004) assertion that familial support and expectation setting can influence the college aspirations of students, and thereby increase their college enrollment rates, regardless of income levels.

While correlations between aspirations and enrollment have been established, there is evidence that aspiring to attain a college degree, unfortunately, does not necessarily align with postsecondary achievement, specifically for low-income students. The correlation between aspirations and postsecondary completion has not been published for the entire ELS 2002 cohort, but a 2017 Institute of Education Sciences report found that nearly two-thirds of the students had failed to realize their postsecondary aspirations by 2012. Specifically, “students who had higher socioeconomic status were more likely than students who had lower socioeconomic status to match rather than to fall short of their postsecondary education expectations” (Molefe et al., 2017, p. 9). Previous findings also recognized that high school student expectations regarding college achievement fell short of actual enrollments (National Center for Education Statistics, 2004).

Overall, the literature indicates that college aspirations of school-aged children and youth are correlated with increased postsecondary enrollment, but that aspirations may not have the same positive effect on postsecondary completion. There is also conflicting research around whether the correlation between aspirations and postsecondary enrollment is similar to or weaker for low-income students compared to higher income students.

Gender

The Digest of Education Statistics reported that females have represented a higher percentage of both part-time and full-time enrollments in degree-granting postsecondary institutions since approximately 1990; this trend is projected to continue through 2029 (De Brey et al., 2019). Other, more regional studies support these trends. Robson et al. (2019) found that males in two different cities (i.e., Toronto and Chicago) were less likely to go to a four-year college than females, and also found that low-income status had a stronger, negative effect on males than their female counterparts.

While postsecondary enrollment has favored females for decades, trends in postsecondary completion are more nuanced (De Brey et al., 2019). Females have accounted for over half of the total associate’s, bachelor’s, and Master’s degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions since approximately the late 1980s, but males dominated completion of Doctor’s1 degrees until the 2004–05 academic year, at which point females accounted for approximately 50% of Doctor’s degrees conferred. Following the 2004–2005 year, females have accounted for over half of all Doctor’s degrees as well. Females are projected to be awarded between 54 and 61% of all degree types through 2030 (De Brey et al., 2019).

While females are completing and on track to continue completing more degrees than their male counterparts, a 2019 study focused on intergenerational economic mobility found that females may not receiving the same level of economic benefit from their degrees as males, depending on their parental income level (e.g., low-income status). Creusere et al. (2019) found gender to be a strong predictor of upward economic mobility, with “male graduates 50.2% more likely than female graduates to be upwardly mobile after controlling [for other factors]” (p. 929). However, when parental income was considered, rates of mobility were similar for very low-income males and females (e.g., that come from families with parental incomes under $23,500/year). This equivalency was reduced as parental incomes increased; economic mobility was approximately 12% higher for males than females when parental income was between $40,500–$65,500/year and double when parental income was between $65,500 and $106,500/year (Creusere et al., 2019). Taken together, the existing literature indicates that while females are more likely to complete postsecondary education, and that students from very low-income families will experience similar upward economic mobility regardless of gender, males from families with parental incomes levels over ~$23,500/year will experience more upward mobility based on degree attainment than their female peers.

Geographical location of high school

While income is associated with outcomes, geographical location also contributes to educational attainment; students from rural areas have lower educational aspirations, and both enroll in and graduate college at rates lower than their urban or suburban peers (Chen et al., 2010; Hu, 2003; Provasnik et al., 2007; U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2003). Koricich et al. (2018) combined the ELS 2002 data with Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) data and found that “rural students are not only less likely to attend any postsecondary education within 2 years of completing high school, but they are also less likely to attend four-year institutions, more-selective institutions, and those that confer graduate degrees” (Koricich et al., 2018, p. 294). Comparisons of the socioeconomic status of these students found that rural students did not benefit as much from a higher socioeconomic status (SES) standing as did their nonrural counterparts; of students from similar, higher SES backgrounds, rural youth were still more likely than nonrural students to attend a two-year versus a four-year institution.

In exploring more of the complexities around educational disparities in rural versus nonrural students, rural students have a higher level of community social resources (i.e., social capital), which tends to increase their likelihood of degree attainment (Byun et al., 2012). When socioeconomic status is considered, rural students are less likely to enroll or graduate from college, overall (Byun et al., 2012). Rural students also tend to lag behind nonrural students in college success, citing higher levels of poverty within rural areas as a key factor explaining the disparities, along with lower parental educational expectations and academic achievement within rural families, and increased distance from more selective institutions of higher education, which disproportionately impacts low-income rural students who need to live at home to afford college (Byun et al., 2012; Roscigno and Crowley, 2001).

More recent works contradict the findings that rural students experience lower rates of college success, in one case through use of similar datasets. Molefe et al. (2017) reported that nonrural students had, on average, higher college aspirations (i.e., completing more college or attaining more advanced degrees) than rural students, ultimately “after background characteristics were controlled for, rural and nonrural students still had similar educational attainment levels, both in the REL Midwest Region and in the rest of the nation” (Molefe et al., 2017, p. 10). Altogether, there is conflicting research with regard to how geographic location of a student’s high school within either an urban or rural area is related to their college enrollment and success rates. The impact that socioeconomic factors, such as family income, have on differential college-success outcomes between urban and rural students is similarly unclear, as higher levels of poverty within rural areas may contribute to findings that correlate rural areas with reduced rates of college success.

Key academic indicators

Academic achievement at the high school (HS) level is, unsurprisingly, correlated with increased college enrollment and graduation. Students who aspire to attend college may prioritize their academic achievement in anticipation of completing college applications and GPA is used as an admittance standard by colleges, explaining the correlation between secondary academic achievement and college enrollment. Additionally, students that do well academically in high school are more prepared for the rigors of college (i.e., college ready), which may explain the correlation with college completion (Davidson, 2014; Hussar et al., 2020; Nagaoka et al., 2009; Ou and Reynolds, 2014).

The impact of secondary academic achievement on college success have been of focus in current scholarship. For example, both 7th-grade and 12th-grade GPA were significant predictors of postsecondary enrollment, while 7th-grade and 11th-grade GPA were significant predictors of postsecondary persistence in Ecker-Lyster’s (2017) study. Likewise, Johns (2019) found that of 10 possible predictor variables, three, including two associated with HS academic achievement, were significant predictors of postsecondary enrollment. Specifically, students that completed higher math courses were 1.3 times as likely, and students with a higher GPA were almost three times as likely, to enroll at a postsecondary institution immediately following high school than those with a lower GPA. In further support of these findings, “when looking specifically at low-income students only, GPA is a statistically significant predictor of postsecondary enrollment, indicating the higher the GPA, the more likely the student enrolled in a postsecondary program” (Rhone, 2019, p. 60).

Lapan and Poynton (2020) found that a demonstrated record of academic achievement in high school (e.g., earning better grades, scoring higher on standardized testing, and enrolling in higher-level courses) was an indicator both of college enrollment as well as retention after the students’ first year at college. Eccles et al. (2004) also identified that students enrolled in college at age 20 had higher 12th-grade GPAs than the not-enrolled group. Related to the assumption that higher GPAs may serve as an indicator of college aspiration, Eccles et al. found that 6th-grade college plans significantly predicted 12th-grade GPAs; in other words, college plans as early as 6th-grade likely affected high school academic performance and eventual college enrollment. Findings (i.e., Engberg and Wolniak, 2010; Rhone, 2019) similarly across the span of nearly a decade have still noted that final HS GPA is strongly influential in predicting enrollment at both two- and four-year institutions, but the effect was much stronger for enrollment at a four-year institution. Indicators of secondary school academic achievement, including high school GPA, are positively correlated with college enrollment for students generally and, more specifically, for students from low-income backgrounds. Yet, data on college completion related to HS GPA remain largely unavailable.

Race/ethnicity

In examining additional factors, recent findings illustrate that White students have, and are projected to continue to, represent the majority of degree-seeking postsecondary enrollment through 2029 (De Brey et al., 2019). However, the percentage of total enrollment that White students represent has been declining since 1976 (84.3%), reaching levels that are relatively consistent with the demographic make-up of the U.S. by the time of the Digest’s 2021 publication. The American Community Survey (ACS) 2019 5-year-estimate indicated that White, non-Hispanic or Latino individuals comprise ~61% of the population, and the Digest noted they accounted for 55.2% of 2018 postsecondary enrollment (PE). Ratios of other racial and ethnic groups for these time periods are Asian, ACS: 5.5%/PE: 7%; Black, ACS: 12.3%/PE: 13.4%; Hispanic, ACS: 18%/PE: 19.5%; Pacific Islander, ACS: 0.2%/PE: 0.3%; American Indian/Alaska Native, ACS: 0.7%/PE: 0.7%; Two or more races, ACS: 2.4%/PE: 3.9% (De Brey et al., 2019; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

While percentages of total college enrollment rates appear to be approaching proportionately with overall population statistics, other, large-scale analyses show patterns of over- and under- representation of racial and ethnic groups by type of college. Asian and White students are overrepresented, and Black and Hispanic students are underrepresented, at more selective institutions. This underrepresentation of Black students is most pronounced in the southern U.S., and while rates of representation at more selective institutions have been equalizing for White and Hispanic students, they have remained stagnant for Black students (Monarrez and Washington, 2020).

The most recent volume of the Condition of Education reported that college enrollment rates have increased for college-aged students within all racial and ethnic groups since 2000, with an aggregated increase of 6% between 2000 and 2018 (Hussar et al., 2020). The largest increases have been Hispanic students (increased by 14%), American Indian/Alaska Native (increased by 6%), and Black students (increased by 6%). The smallest increase was Asian and White students (both 3%). Asian students have had the highest rates of college enrollment since at least 2000 (59% in 2018), and even with the recent increases by Hispanic and other non-White students, White students still have the third highest college enrollment rates (42%) after students of two or more races (44%). Comparatively, 24% of both Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native, 37% of Black, and 36% of Hispanic college-aged students enrolled in college in 2018.

The outcomes for postsecondary completion has varied based on institution type (De Brey et al., 2019). Mirroring enrollment rates, Black students had the lowest graduation rates with 150% of normal time for both bachelor’s (40%) and associate’s (23%) degrees. Asian students had the highest graduation rates for both degree types, 74 and 36%, respectively. White students had the next highest completion rate at four-year institutions (64%), while Pacific Islander students had the next highest completion rate at two-year institutions (34%). When combined, enrollment and graduation data indicate that while college enrollment rates of minority students have increased over time and are approaching proportionality with overall U.S. demographics, there are stark discrepancies in the rates of degree attainment, with Black or African American students having, overall, the lowest rates of college enrollment and graduation.

Researchers have explored the intersection between race, ethnicity, gender, college enrollment, and other factors, such as social capital. To illustrate, Riegle-Crumb (2010) examined gender gaps in college enrollment rates between Hispanic and White students, finding that females of both ethnicities attended college at higher rates than their co-ethnic male peers. Their research indicated that the higher access to social capital through academically-focused friend groups (for females of both ethnicities), and interactions with high school counselors on the subject of college (for Hispanic students only), served as predictors for the higher college enrollment rates of females.

The intersection between race, ethnicity, familial income, and college enrollment has also been an area of investigation. Compared to above-poverty-level students, large-scale analyses have found that low and very-low income undergraduate students were more likely to be Black, Hispanic, or Asian (Chen and Nunnery, 2019). African American and Hispanic students were significantly less likely to complete a four-year degree than their White peers, even when examined by income category (Blankenherger et al., 2017). However, this conflicts with other work. For example, Tekleselassie et al. (2013) noted that after, controlling for socioeconomic status, the racial gap between African American and Caucasian students around college enrollment disappeared. The researchers did find that, even after controlling for other variables, a similar gender gap was revealed, and this gap was exacerbated within the African American sample. Tekleselassie et al. (2013) also noted that while the gender gap for college enrollment among Caucasian students was approximately 2% in favor of females, with African American students it was 36% in favor of females. As the authors stated when considering the social and economic benefits to an increased education, “African American men’s disadvantages in college attainment when compared to their female counterparts is concerning” (p. 140).

The associations among finances, race, and college enrollment may not be of surprise, scholars have found that students from low-income backgrounds attend college and persist to graduation at rates much lower than their higher income peers. Wealth disparities likely account for some of the differences in postsecondary outcomes seen between groups, specifically between White, and Black and Hispanic, students, as “the typical White family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family” (Bhutta et al., 2020, para. 1). Creusere et al. (2019) also found that, in general, mobility rates for underrepresented minority students were lower than for non-underrepresented minority students. As with their gender analysis, the race/ethnicity of students played “a complicated role in intergenerational mobility” when combined with parental income status, as “at the lowest income levels, the difference in mobility rates is quite small” (Creusere et al., 2019, p. 934). Ultimately, race/ethnicity equivalences are reduced as parental incomes increase, and these variables remain essential considerations in exploring predictions toward postsecondary completion.

Methodology

This study was conducted upon attaining Institutional Review Board approval using a quantitative methodology with binary logistic regression. This was determined to be the most appropriate statistical test to explore the research questions based on the composition of the variables and the research topic. Logistic regression is a flexible approach that can be used to predict a categorical outcome or membership in a group when there are multiple predictors and it is unclear if those predictors are the causes of the outcome (Menard, 2010). Logistic regression is “currently considered the [original emphasis] best practice when dealing with outcomes that are dichotomous or categorical in nature” (Osborne, 2014, p. 17).

A binary logistic regression was used to determine which, if any, of six independent variables predicted college completion in 150% of normal time to degree for GEAR UP eligible students that enrolled in college. The primary research question was, Can postsecondary completion of GEAR UP eligible students who enroll in college be reliably predicted from knowledge of 12th-grade GPA, 7th-grade college aspirations, cumulative GEAR UP program service hours, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity? For this primary question, the null hypothesis and the alternate hypotheses were as follows:

H10: None of the six predictor variables (12th grade GPA, 7th grade college aspirations, cumulative service hours, gender, middle school setting, race/ethnicity) will significantly predict postsecondary completion within 150% of normal time.

H1a: At least one of the six predictor variables will significantly predict postsecondary completion within 150% of normal time.

The second research question focused on whether postsecondary completion could be predicted through certain variables, and the third research question centered on the strength of the resulting model at classifying cases. For the second research question regarding variable prediction, the hypotheses centered specifically on the strength of the particular predictor variables in relation to the outcome variable of college completion in 150% normal time to degree. As such, the following hypotheses were reflective of the exploration on the relative strength of the six predictor variables:

H2a: 12th grade GPA will have the strongest positive relationship with postsecondary completion within 150% of normal time.

H2b: Cumulative GEAR UP service hours will have a significant positive relationship with postsecondary completion, but a weaker effect than GPA.

H2c: 7th grade college aspirations will have a weaker, non-significant relationship with postsecondary completion compared to GPA and service hours.

H2d: Gender will not significantly predict postsecondary completion when controlling for other variables.

H2e: Middle school setting (rural/urban) will not significantly predict postsecondary completion.

H2f: Race/ethnicity will not significantly predict postsecondary completion when controlling for GPA and service hours.

Related, for the third research question, the intention was to assess the overall strength of the model, with the null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis as follows:

H30: The logistic regression model including the six predictors will not significantly improve classification accuracy of college completion status compared to a null model.

H3a: The logistic regression model including the six predictors will significantly improve classification accuracy of college completion status compared to a null model.

Data sources for dataset

Two data sources were used to establish the dataset for this study – the GEAR UP Cohort 2 report was maintained by Nevada GEAR UP program staff and includes demographic, academic, and survey data for 5,977 students (after deduplication) that were identified as eligible for participation in GEAR UP Cohort 2. Note that this report contained information on students who were eligible for but did not participate in GEAR UP activities, as represented by cumulative service hours total of zero. Service hours were collected during participants’ 7th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade years and recorded in separate columns, which were then merged into the overall dataset. The resulting totals were placed within one of four categorical groupings: no participation (0 h), low participation (>0 to <100 h), moderate participation (100 to <1,000 h), and high participation (1,000 + hours). These categories were developed through consultation with university faculty and were determined based on a consideration of average weeks of school per year, when the data were collected by program leaders, and what would constitute low versus moderate versus high participation.

This cohort began receiving services in their 7th-grade years during AY 2006–2007 and graduated high school in spring 2012. This dataset contains information for, or that informs the coding of, all predictor variables. The next source was generated by National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) in January 2019, which included the postsecondary enrollment and attainment data for these same 5,977 GEAR UP program-eligible students. The names and other required personally identifiable information for these 5,977 students were submitted to NSC on December 2018. The NSC produced three reports, all of which were used to identify postsecondary enrollment status for this study. Appropriate data screening occurred, as well as testing of assumptions, which were not found to be in violation of the test. Only complete cases (i.e., those records for which data were available on all six predictor variables, as well as the outcome variable) were included in the analysis. After conducting screening and testing of assumptions, 1,632 cases were used to establish the dataset and conduct the analysis.

Variables

In alignment with the primary question for this study, the outcome variable was postsecondary completion (No = 0, Yes = 1) as evidenced by degree attainment within 150% of the normal time to degree. The categorical predictor variables were 7th-grade college aspirations (High school or less = 1, Some college but less than a 4-year degree = 2, 4-year degree or more = 3) through a self-reported survey, cumulative GEAR UP service hours (Low participation = 1, Moderate participation = 2, High participation = 3), gender (Female = 1, Male = 2, middle school setting (Rural = 1, Urban = 2), and race/ethnicity (American Indian = 1), Asian = 2, Black = 3, Hispanic = 4, White = 5). The continuous predictor variable was 12th-grade GPA.

Limitations

This study was limited to data collected by others as part of GEAR UP programmatic activities and to postsecondary data produced by others upon request. The researcher did not collect any of the data utilized in this study and therefore cannot validate its accuracy. Additionally, the college aspiration variable utilized data provided by program participants in their 7th-grade year and accuracy of this data was dependent on the answers provided by students.

GEAR UP data were available only for three periods during program service delivery: the 7th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade years of program participation. This limitation was most relevant to the cumulative service hours variable, which summed the number of service hours reported in each of these years. It is possible that inclusion of service hour totals in students’ 8th-, 10th-, and 11th-grade years would have resulted in different statistical outputs and interpretation of results, but this information was not available for use in this study. The postsecondary data report produced by the NSC did not contain data for all GEAR UP program participants. Specifically, the NSC reported that postsecondary data were blocked for 53 students due to institution or student restrictions. Because personally identifiable information was not available for these students, they could not be removed from the analysis. It is possible that their inclusion in the analysis may have skewed the final results, as up to 53 students may have been classified incorrectly as not completing a college degree due to unavailable data. Analysis of the data also required merging of datasets and the manual coding of some key variables. While the resulting merged dataset was thoroughly reviewed without noted errors, it could still include human error. It is also possible that other researchers would have differed in manual coding decisions.

Results

The binary logistic regression analysis included only those students for which data on all variables were available (n = 1,704). Cases that were missing data for any of the predictor variables (12th-grade GPA, 7th-grade college aspirations, cumulative GEAR UP program service hours, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity), or that did not enroll in college, are not included in the binary logistic regression. Descriptive statistics for all GEAR UP Cohort 2 eligible students (n = 5,971) are provided in the following section, and descriptive statistics for only those students whose records are included in the logistic regression are presented in detail within the Binary Logistic Regression session.

Descriptive statistics

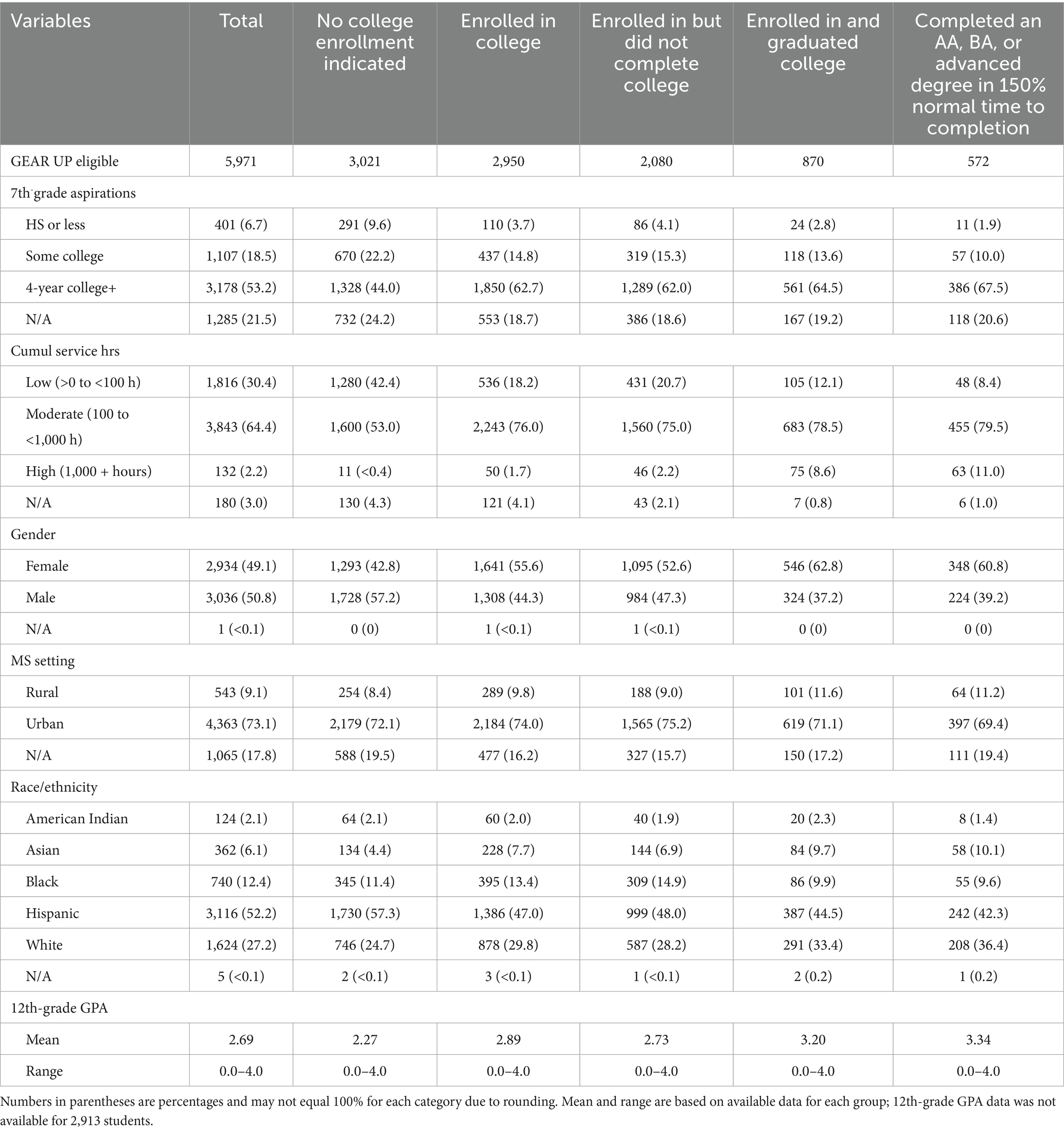

Descriptive statistics allowed for an overall examination of the cases in this study. Table 1 provides an overall view of the complete dataset to glean the unique composition of the students who participated (as a whole) in the GEAR UP program. In total, data provided by NSC indicated that 2,950 out of the 5,971 GEAR UP Cohort 2 eligible students enrolled in college (2,950/5,971 = 49.4%); 2,080 of these students did not complete college (2,080/2,950 = 70.5%) while 870 did complete college (870/2,950 = 29.5%) by the time the NSC report was run. 2,916 of the 2,950 students that enrolled in college could be coded as having either graduated (n = 572, 572/2,916 = 19.6%) or not graduated (n = 2,344, 2,344/2,916 = 80.4%) with a postsecondary academic degree within 150% of the normal time to degree completion. Degree type or other relevant data was missing for 34 students and their inclusion in the 150% normal time to completion category could not be determined.

Students that enrolled in college (n = 2,950) varied from students that did not enroll in college (n = 3,021) on a few key characteristics. Students that enrolled in college had higher rates of college aspiration (77.5% = 62.7% aspiring to a four-year degree + 14.8% aspiring to some college) than those for which no college enrollment data was indicated (66.2% = 44% aspiring to a four-year degree + 22.2% aspiring to some college). Students that enrolled in college demonstrated higher rates of moderate or high participation in GEAR UP programming (77.7% = 76% + 1.7%) compared to students for which no college enrollment data was indicated (54% = 53% + <1%). Females made up less than half of the GEAR UP Cohort 2 (49.1%) but were more highly represented than males in both the enrolled in college group (55.6% compared to 44.3%) and completed college group (62.8% compared to 37.2%). Compared to the total Cohort 2 population (n = 5,971), Asian and White students were overrepresented in the groups that enrolled in and graduated college (i.e., made up a larger proportion of these groups than they did in the Cohort 2 population). Hispanic students were underrepresented within these same groups, and Black students were slightly underrepresented in the group that graduated college. Students that enrolled in college had a higher mean GPA (2.89) compared to students that did not enroll in college (2.27). Students that completed college in 150% normal time to completion had the highest mean GPA of all groups (3.34) compared to students who enrolled in and graduated college (3.20) and students who enrolled in but did not complete college (2.73).

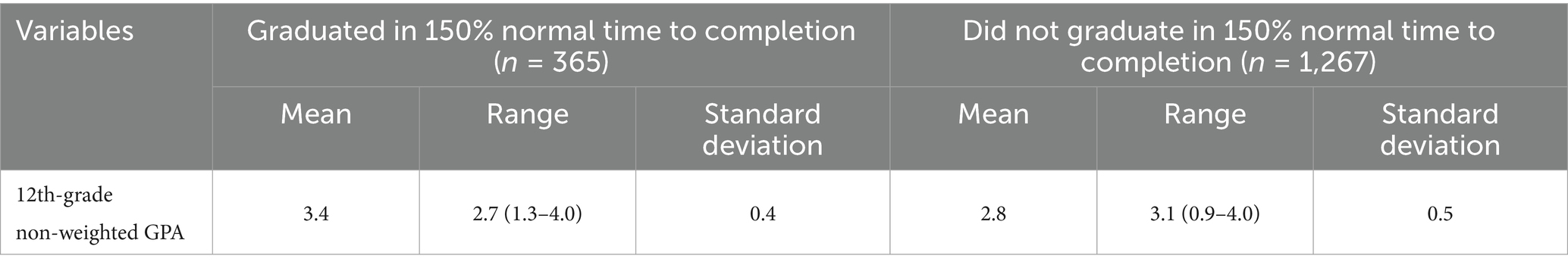

Now focusing purely on the complete cases explored for this analysis, the majority of students included in the binary logistic regression did not obtain a degree within 150% normal time to completion, with 78% of the 1,632 students who did not graduate and 22% who did graduate within the designated time to completion. For 12th-grade, non-weighted GPA, students who graduated in 150% normal time to completion had a higher mean GPA than students that did not graduate in 150% normal time to completion (Table 2). They also had a slightly lower standard deviation, indicating less variation in the spread of the data. This is also evident in the range of GPAs within each group. While both groups had a maximum GPA of 4.0, students who graduated in 150% normal time earned a higher minimum GPA value (1.3 v 0.9).

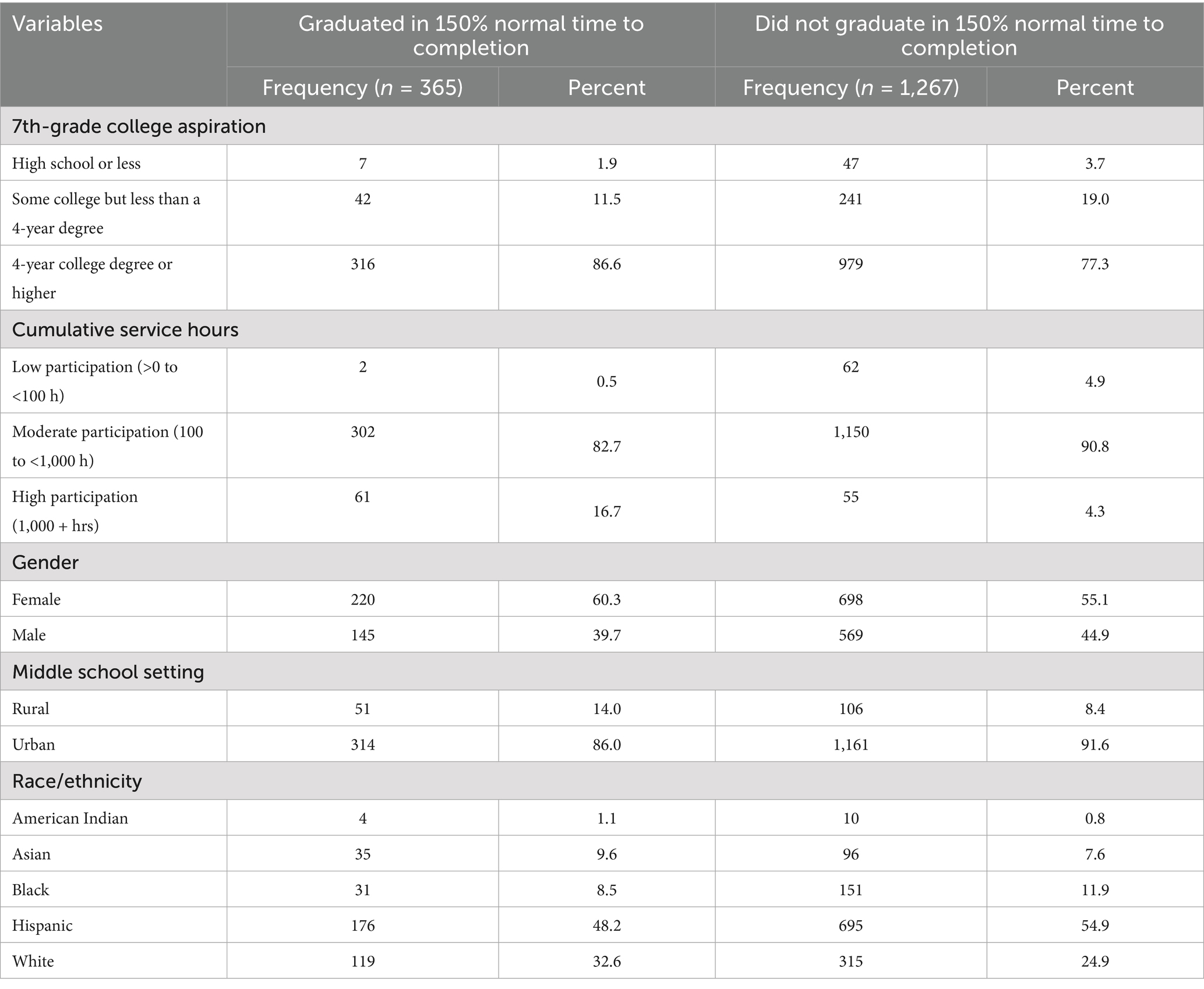

Table 3 provides frequencies of each of the categorical predictor variables, followed by a brief narrative summary for each variable. Students who graduated in 150% normal time expressed slightly higher rates of college aspiration than those who did not express aspirations to attend some college, 87% compared to 77%, respectively. A similar trend was evidenced regarding participation in the program with increased participation aligning with completion time. Females were only slightly overrepresented in the graduated in 150% normal time to completion group compared to males. Also, students who attended a rural middle school were slightly overrepresented within the completion group as compared to urban students. In examining racial/ethnic demographics. Asian and White students were slightly overrepresented in the group that completed college in 150% normal time (9.6% compared to 8% in the overall dataset, and 32.6% compared to 26.6%, respectively), while Hispanic and Black students were underrepresented within this same group (48.2% compared to 53.4% in the total dataset, and 8.5% compared to 11.2%, respectively).

Binary logistics regression

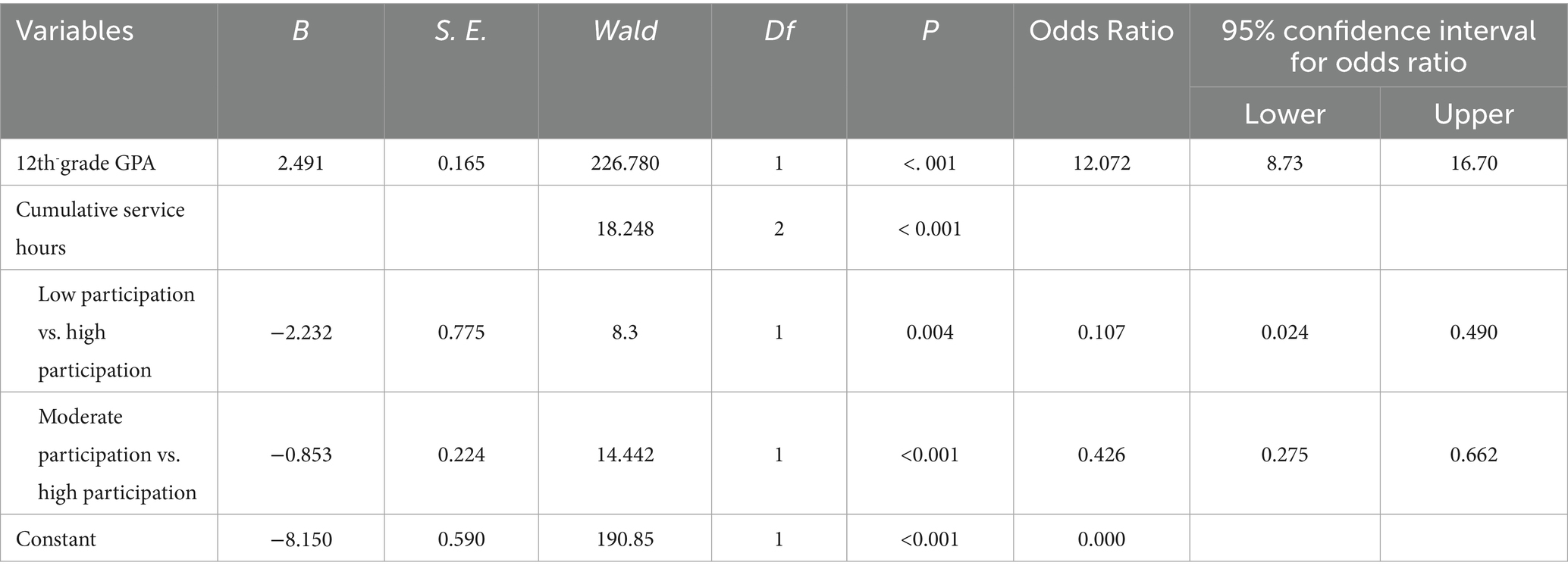

Regression results indicated that the overall model of two predictors (12th-grade GPA and cumulative service hours) was questionable (−2 Log likelihood = 1,339.36) but statistically reliable in distinguishing between completing or not completing a college degree in 150% normal time [χ2(2) = 395.431, p < 0.001], with Cox & Snell R2 = 0.215 and Nagelkerke R2 = 0.329.

Table 4 shows the regression coefficient, standard errors, Wald tests, dfs, p values, odds ratios, and the 95% confidence intervals around them when all other predictors are held at a constant, the odds ratio of 12.072 means the change in the odds of 150% normal time to degree completion given a one-unit increase in 12th-grade GPA. In addition, the odds of a student with low participation in service hours being able to graduate in 150% normal time to degree completion were 0.107 times as great as the odds of a student with high participation in service hours graduating in 150% normal time to degree completion. The odds of a student with moderate participation in service hours being able to graduate in 150% normal time to degree completion were 0.426 times as great as the odds of a student with high participation in service hours graduating in 150% normal time to degree completion. In other words, students in the high participation group were more likely to graduate within 150% normal time to degree completion than students in the other two participation groupings. Importantly, the model correctly classified 81% of cases. The final model correctly classified 94% of cases that did not graduate in 150% normal time and 37% of cases that did graduate in 150% normal time to completion.

The research questions were important to better understanding the participants and the efforts of the GEAR UP program. Specifically, six predictive variables were considered in relationship to the outcome variable of 150% normal time to degree completion. Table 5 provides an overview of the questions, hypotheses, and observed results.

Discussion

The 12th-grade GPA and participation in GEAR UP programming were predictors of college degree attainment within 150% normal time to completion. Even so, in considering the 37% of cases for those who did graduate in 150% normal time to completion, it is important to acknowledge the model’s predictive accuracy. Essentially, it could be that the model may be better-serving for interventions, rather than predictions, across the program years 7th, 9th, 12th, similar to Sanchez and Mutiga (2024) results that revealed the 9th-grade was a critical year in the academic transition toward college-readiness. The model may also be used to target the service types to identify more nuanced differences, rather than cumulative hours. While cumulative hours provided overall participation distinctions, the low, moderate, and high participation could be sorted in an exploratory means to determine if there is an average range of hours that improves the models’ accuracy. Additionally, it is essential to still conduct analyses with disaggregated hours by service type to more accurately determine which service experiences lead to long-standing educational impacts toward access, retention, and completion of postsecondary education. For example, in this study, the remaining four predictor variables (i.e., 7th -grade college aspirations, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity) were not identified as predictors within the final model. In Sanchez and Mutiga (2024), similar results were noted, and it was concluded that the GEAR UP program may be leveling the playing field in its service offerings. Specifically, mentoring and tutoring were essential services that contributed to program successes (Sanchez and Mutiga, 2024). In doing, it establishes an opportunity whereby the services may be uplifting students across all demographics.

Notably, it was identified that GEAR UP-eligible students’ average college enrollment rate was slightly higher than recently reported national averages for similar students. Of the 5,971 GEAR UP-eligible students, 3,021 (51%) did not show evidence of college enrollment while 2,950 (49%) did enroll in college. For context, college enrollment rates for recent high school graduates in the lowest income quartile were in the mid-45% range during 2012, in line with the timeframe of GEAR UP participants (Cahalan et al., 2018). Also, the college participation rate for students from low-income backgrounds in Nevada was 35% during this similar participation time. It is acknowledged that GEAR UP services are provided to all students within the starting cohort grade-level based on a Free and Reduced Priced Lunch rate of at least 50% for the school, so not all GEAR UP students were necessarily from a low-income family background. Also, approximately 3% did not participate in GEAR UP programming during the years at which relevant datapoints were collected. With this in mind, the findings demonstrate that participation in the GEAR UP program was associated with higher-than-average college participation rates.

When focused on aspirations for postsecondary attainment, students who aspired to enroll in some college or obtain a four-year degree or higher were more highly represented in the group who enrolled in college compared to the group that did not, 77.5 and 66.2%, respectively. They were only slightly more represented within the subgroup that completed rather than did not complete college (78.1% compared to 77.3%). Indeed, college aspirations of youth are correlated with increased postsecondary enrollment, necessarily college completion, especially for those from low-income family backgrounds (Sanchez and Mutiga, 2024; Christofides et al., 2015; Eccles et al., 2004; Lapan and Poynton, 2020; Molefe et al., 2017).

The overall GEAR UP participation composition by college-going and college-completion also reflected current literature for academic achievement, gender, middle school setting, program participation, and race/ethnicity. Consistent with the literature (Ecker-Lyster, 2017; Engberg and Wolniak, 2010; Johns, 2019; Lapan and Poynton, 2020), students in this study who enrolled in and completed college had increased levels of secondary academic achievement as demonstrated by 12th-grade GPA. Female students were more highly represented than expected based on the total cohort composition within the college-going and college-completing groups, aligning with current findings (De Brey et al., 2019). Middle school setting of either rural or urban did not appear to have a large impact on college enrollment, although within the enrolled in college group rural students made up a slightly larger proportion of the completers subgroup than was expected based on the composition of the entire cohort. This, for the most part, mirrors findings regarding conflicting results when exploring the impact of rural and nonrural student outcomes (Byun et al., 2012; Koricich et al., 2018; Molefe et al., 2017).

Evaluations of the GEAR UP program have found that program participation is correlated with increased college enrollment (Fogg and Harrington, 2015; Knaggs et al., 2015; Lunceford et al., 2017), which is reflected in the dataset at-large for GEAR UP participants. Specifically, students with moderate to high participation levels were more highly represented in the enrolled in college and completed college groups than was expected. Asian and White students made of larger proportions of the enrolled and completing groups than was expected, while Hispanic students made up smaller proportions of these groups and Black students made up a smaller proportion of the college completing but not college enrolling groups. Findings reflect large-scale studies indicating that Asian and White students have the highest rates of college completion and Black students having, on average, the lowest rates of college graduation (De Brey et al., 2019).

Significance of the model

While the opportunity to examine the overall statewide descriptive statistics revealed commonalities across the literature, it is essential to focus on the two key variables that served as predictors for this work. As such, 12th-grade unweighted GPA and cumulative service hours were found to be predictors of college degree attainment within 150% normal time to completion. In line with these findings, secondary academic achievement has consistently been correlated with increased college enrollment and persistence; scholars express that this is because students who aspire to attend college likely prioritize pre-college academic achievement and because students who do well academically are more prepared for the rigors of college (Nagaoka et al., 2009; Davidson, 2014; Hussar et al., 2020; Ou and Reynolds, 2014). Some researchers have specifically found a correlation between HS GPA and college enrollment, with higher GPAs being significant predictors of college enrollment and persistence (Ecker-Lyster, 2017; Johns, 2019; Rhone, 2019). Additionally, with GPA’s role as the strongest predictor of completion, this helps address the cumulative nature of academic preparation and persistence behaviors. As such, with GPA as a predictive variable, this may reference not only cognitive ability or mastery of academic content but also non-cognitive traits that were beyond the focus of this study. It could be that other areas not accounted for in this work, such as self-discipline, goal orientation, intrinsic motivation, time management, etc. For GEAR UP students—who often come from lower-income or first-generation backgrounds—GPA can represent the student’s ability to gain the necessary support to navigate academic systems effectively and maintain consistently, regardless of the known challenges. Thus, while this reflects a cognitive orientation as a prediction on the outcome variable, it may also reflect aspects of resilience toward desired goals. Certainly, academic performance remains a critical factor, but opportunities to include interventions that support that academic progress through skill-building, sustained motivation, and self-regulated learning throughout their educational pathways as GEAR UP students may help to (even if indirectly) increase the odds of postsecondary completion, as intended by GEAR UP programming.

Along with the academic focus, placement of GEAR UP service hours as a proxy for GEAR UP participation (i.e., intervention) within the model is likely due to the range of activities. College preparation activities often include academic rigor of secondary courses, smaller class sizes, FAFSA awareness and completion, participation in structured youth development activities, and access to social capital (Belasco, 2013; Dynarski et al., 2013; Lapan and Poynton, 2020; Morgan et al., 2018). Several of these activities are required components of GEAR UP programming. Required GEAR UP services comprise providing postsecondary education financial aid information (aligning with FAFSA awareness and completion) and encouraging students to enroll in rigorous coursework to reduce their enrollment in remedial education at the postsecondary level (aligning with academic rigor of secondary courses). GEAR UP providers must use a combination of mentoring, outreach, and provision of supportive services, which may increase access to social capital. Finally, the GEAR UP program, itself, is a structured youth development activity.

As a predictive variable, participation in GEAR UP services helps to capture the degree to which students were exposed to the noted activities of mentoring, academic tutoring, college visits, and workshops, among other academically-driven efforts. These experiences are reflective of more opportunities to expand college knowledge, along with opportunities to potentially broaden various means of capital and self-efficacy. One way to consider this predictive variable on the outcome variable is that the services hours may be reflective of other variables that could serve as more direct, strong predictors, such as program engagement, investment, or sense of belonging. For this study, cumulative aspect of the services hours may be capturing this as an operational indicator of those more nuanced predictive variables.

The use of best practices for facilitating student success within the GEAR UP program may explain the correlation between higher GEAR UP participation levels and higher college success as indicated by predicted placement within the degree attainment within 150% normal time to completion category.

Although evaluation activities of GEAR UP programming have found that participation is correlated with college enrollment and persistence (Kim et al., 2021; Sanchez et al., 2015), little to no research is available that explores the impact of GEAR UP programming on college degree attainment. This shortfall was one of the primary reasons that this research study was conducted. Based on these results, GEAR UP programming is not only correlated with college enrollment, it is also a predictor of college completion within 150% normal time. Furthermore, increased levels of participation (1,000 + hours) more strongly predicted placement in the college completion group.

Variables not significant in the model

The remaining four predictor variables of 7th-grade college aspirations, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity were not found to be predictors of college degree attainment within 150% normal time to completion. The results of middle school setting more or less align with existing literature, which provides conflicting data on whether being from a rural or urban setting impacts college success (Byun et al., 2012; Koricich et al., 2018; Molefe et al., 2017). In contrast, these results do not align with existing literature for college aspirations, gender, and race/ethnicity, which report that aspiring to attend college is highly correlated with eventual enrollment (Christofides et al., 2015; Eccles et al., 2004; Lapan and Poynton, 2020), that females are more likely to complete college (De Brey et al., 2019), and that students of particular racial or ethnic groups are more and less likely to graduate with a college degree, with Black and African American students having the lowest rates of degree attainment (De Brey et al., 2019).

A possible explanation for the variance between this study and the findings of others may be that the GEAR UP program is helping to ensure that all students, regardless of their personal circumstances or characteristics, are provided with the information they need to prepare for and succeed in college. It is also possible that the program is encouraging college attendance, and thus increasing the aspirations for students that in the 7th-grade did not aspire to attend or complete college. In this sense, one consideration could be to more critically examine sample characteristics in future studies. For example, given the self-reporting of high aspirations of GEAR UP students (Dalpe, 2008; Sanchez, 2010), it could be that these early years make it more difficult to detect an effect. For instance, in Sanchez and Mutiga (2024), it was noted that college-seeking information varied vastly between 7th-grade and 12th-grade, relying on family in the early years and switching to a reliance on school personnel in the later year. This variation can limit the predictive relationships. Given the data came from one state that has had long-standing GEAR UP efforts, it may be that relationships are also limited due to contextual variables, which include the variations across schools.

In any case, the majority of literature that explores these variables, specifically college aspirations, does so through the lens of college enrollment rather than graduation completion. It is possible that similar studies that explore college completion rather than enrollment would produce results consistent with what is demonstrated in these findings. Overall, these inconsistencies reveal the need for more studies that investigate college completion, rather than enrollment or other proxy measures of college success.

Implications for practice

As the model shows that academic preparation (as demonstrated through 12th-grade GPA) and participation in service hours to be predictors of higher odds of college completion, GEAR UP programs should consider prioritizing activities that support higher academic readiness and higher program participation. Additionally, the model did not indicate that variables that traditionally I are related to college success, namely 7th-grade college aspirations, gender, middle school setting, and race/ethnicity, were predictors of college completion. That may indicate that the GEAR UP programming offered to this cohort between the time period of fall 2006 through spring 2012 was successful in overcoming these barriers, and current and future GEAR UP programs may consider modeling program in an effort to potentially to replicate these successes.

Recommendations for future research

Much of the existing literature explores predictors of college enrollment or other proxy measures of college success rather than college completion. This is due to several challenges that can be difficult to overcome. The first is that GEAR UP grants traditionally cover a six- to seven-year period that begins during students’ 7th-grade year and closes either upon the end of their 12th-grade year or their first year of college. This timeline does not allow for the inclusion of evaluation activities focused on college completion to be funded through the grant. Those researchers who are interested in pursuing this line of inquiry may also face barriers to obtaining and merging GEAR UP participant data; margining of datasets required the assistance of a software engineer, which many researchers likely do not have access to or cannot afford, especially if they are conducting this research outside of a funded grant. These challenges are noted to provide context for the lack of comparable research that focuses on college graduation, as well as to allow researchers to address and overcome these through the planning process.