- Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Introduction: Supporting wellbeing within education settings is vital. Whole school approaches present a holistic and integrated mechanism that recognises school staff, the school community, and pupils. The Well Schools whole school approach to supporting teacher and pupil wellbeing provides a framework that guides planning, policy, and practice while allowing for bespoke and socially valid approaches suitable for each school community.

Method: A case study approach explored how schools adopted the Well Schools framework, and what practices and provisions schools were offering as part of Well Schools. Second, it aimed to identify the perceived impact of embedding the Well Schools approach for schools, teachers, and pupils. Ten case study schools were recruited that were implementing Well Schools and that represented diversity in setting type, varying locations across the UK, and school demographics. Data was collected via interviews (n = 16) with school leaders and class teachers that focused on their experiences and engagement with the whole school approach, with particular attention to the process of implementation.

Findings: Six themes were identified covering how Well Schools was being implemented, what drove this, and the impact it was having: (1) staff enrichment, (2) pupil enrichment, (3) motivation, (4) capability, (5) awareness and engagement, and (6) sustainability. Findings suggest the value of supporting staff and pupil wellbeing was central to an effective learning environment that supported wellbeing. Well Schools offered the opportunity for schools to build relationships, collaborate, and learn from a network of schools. This network and the engagement with like-minded schools were identified as a reason why some schools were attracted to the whole school approach.

Conclusion: Promoting Well Schools can help other schools adopt better practices for health, wellbeing, and identify ways of developing holistic wellbeing at the school, teacher, and pupil levels. Such continued engagement further exemplifies the feasibility, acceptability, and positive impact the case study schools reported regarding Well Schools.

1 Introduction

National trends from the Department for Education show a concerning pattern for children and young people’s reduced mental and physical health (Department for Education, 2023), and The Children’s Society (2023) reports “children’s wellbeing is at a ten-year low,” and this is echoed internationally (World Health Organization, 2022a; World Health Organization, 2022b). The education community can play a significant role in promoting the physical and psychological wellbeing of their children and young people (Department of Health and Social Care & Department for Education, 2017), and whole school approaches are a recognised avenue for achieving this (Demkowicz and Humphrey, 2019). ‘Well Schools’ is a whole school approach that presents an overarching framework to promote a culture of wellbeing permeating the school and its community. The framework sets out a series of broader objectives alongside exemplar approaches that can be designed and adapted to suit individual schools and their diverse contexts. The approach is designed to be flexible and adaptable rather than a precise ‘one size fits all’ approach. The current work aimed to capture how a diverse range of schools across the UK implemented Well Schools, examining the factors underpinning decision-making and identifying what approaches they used, worked well, and where challenges arose and how these were managed. Understanding the nuanced approaches and contextualised factors that underpin successful approaches to whole school wellbeing is vital for the education community. Moreover, such insights will help address challenges faced by children and young people regarding their mental health and wellbeing that are reported on a national level (Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, 2021).

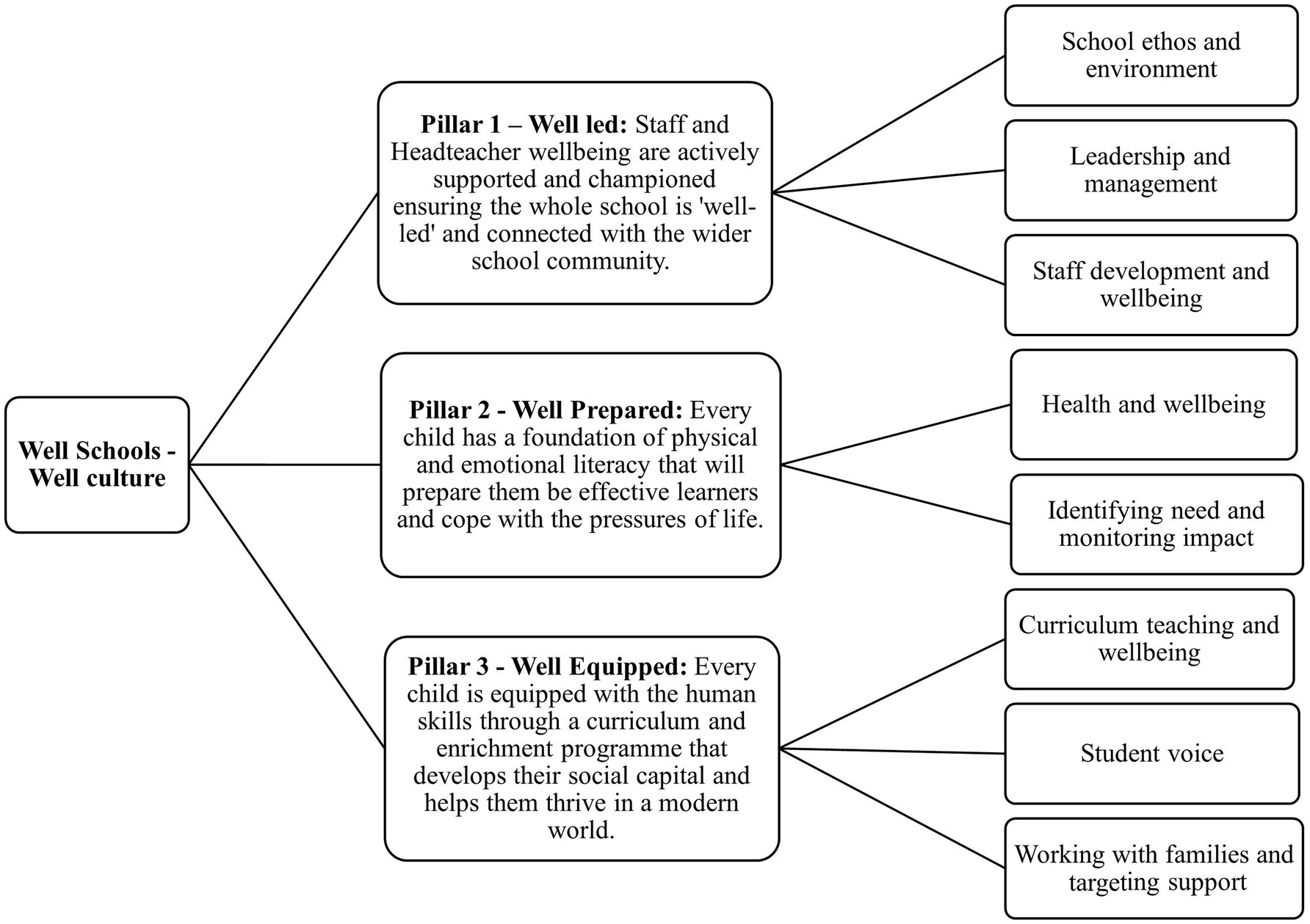

School wellbeing, regarded as the wellbeing of the pupils and staff within schools, is timely and vital to supporting the holistic development of children. The wellbeing of pupils is recognised as a key aspect of development and is associated with short- and long-term outcomes across learning, attainment, health, and future success (Early Intervention Foundation, 2015). However, how we understand and define wellbeing is a multifaceted and complex concept (Petersen et al., 2020), crucially impacting the types of provision and support education settings can put in place. Models of wellbeing focus on hedonic wellbeing, concerned with the immediate states of happiness, and that of eudaimonic wellbeing concerned with the realisation of potential, personal growth, self-acceptance, and life satisfaction (Ryan and Deci, 2001). However, researchers have suggested wellbeing is more than this (e.g., Ruggeri et al., 2020), suggesting it should also include domains such as social and emotional (Jarden and Roache, 2023) and physical wellbeing (Hennessey et al., 2024). This has led to the possibility of unidimensionality of wellbeing, incorporating multiple dimensions that are not necessarily separate but instead interact (Khanna et al., 2024). The Well Schools approach aligns with this idea of a holistic perspective on wellbeing, and emphasises school support and approaches spanning multiple domains, including, for example, physical and mental health, as well as developing social, emotional, and life skills (Hennessey et al., 2023). Well Schools, in a Youth Sport Trust initiative (UK charity, https://www.youthsporttrust.org/), promotes the use of whole school approaches to support the wellbeing of teachers and their pupils. A Well School promotes the idea that children and young people are more effective learners when they are happy and well, emphasising the importance of wellbeing for academic performance. It advocates that taking care of staff and pupil wellbeing fosters a culture that allows everyone to reach their potential. Well Schools therefore focuses on supporting the wellbeing of school staff, senior leaders, and pupils to improve education outcomes. The Well Schools ideology of school culture and ethos for supporting wellbeing was underpinned by three pillars. Pillar 1 – Well Led—Staff and headteacher wellbeing is actively supported and championed, ensuring the whole school is ‘well-led’ and connected with the wider school community. Pillar 2—Well Prepared—Every child has a foundation of physical and emotional literacy that will prepare them to be effective learners and cope with the pressures of life. Pillar 3—Well Equipped—Every child is equipped with the human skills (e.g., resilience, leadership, teamwork) through a curriculum enrichment program that develops their social capital and helps them thrive in a modern world.

Whole school approaches to wellbeing are commonplace, nationally (Glazzard, 2019; Public Health England, 2019) and internationally (Cavanagh et al., 2024, WHO, 2023). Whole school approaches can help enable pupils to develop resilience and learn strategies to cope (Glazzard, 2019), thereby promoting wellbeing. Such approaches aim to provide supportive, caring, and nurturing environments via the culture, ethos, and climate of the school and connections with the family and community, as well as through curriculum, teaching, and learning (WHO, 2023). As whole school approaches are complex and multi-level, so must recognise the interactive systems between the individual child and the school environment and community (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006; Lewallen et al., 2015). Schools are ideally placed to support access to mental health and wellbeing provision, and whole-school approaches have been successful in supporting a range of wellbeing-associated outcomes (Lekamge et al., 2025), improving and decreasing externalising and internalising symptoms (WHO, 2023), supporting social and emotional development (Goldberg et al., 2019). Moreover, they have also been successful in improving teacher wellbeing (Lester et al., 2020). Yet, their success is dependent on an appreciation of the local context and cohort. Cavanagh et al. (2024), in an international scoping review of whole school approaches, identified the range of barriers and facilitators to whole school provision that need to be understood, for example, school size and staffing, leadership and buy-in, and positive student-staff relationships. The Well Schools approach embraces the idea that support for wellbeing within school should be led top-down and is best supported by the whole school. Yet, understanding the individualised context and decision-making on approaches individual schools take to support wellbeing in their school is needed to provide not only guidelines for good practice, but the context underpinning these – what works for one school may not necessarily work for another.

Public Health England (2015, 2019) identifies eight principles for promoting emotional health and wellbeing in schools that align with the Well Schools framework, and these eight principles map to the Well Schools ideology (see Figure 1). Pillar One Well Led concerns how staff, leadership, and development promote a school ethos and environment of wellbeing. Pillar Two, Well Prepared, is concerned with the emotional foundations and skills pupils enter school with, and links to how schools continue to support and monitor health and wellbeing. Pillar Three Well Equipped considers how schools can build skills through the curriculum, teaching and learning, pupil voice, as well as by working with families. The Well Schools approach is built on the idea of a community platform that provides a community for schools to join and share practices. Therefore, there will be common approaches embraced across Well Schools, as well as additional bespoke approaches to meet the needs of staff and pupils in the unique context of each school. Well Schools centralises teacher wellbeing, a factor often misunderstood and poorly conceptualised (Ozturk et al., 2024). Pupils, supported by teachers, who exhibit protective factors, such as confidence and resilience, are known to achieve better educational outcomes (Day, 2008; Mansfield et al., 2016). However, concurrent research regarding staff wellbeing is often overlooked, and for sustainable whole-school approaches to wellbeing, such knowledge may be vital (Harding et al., 2019). The relationship between teacher and pupil wellbeing is a factor of the Well Schools logic chain, making this a well-timed investigation. Thus, the adoption and interpretation of Well Schools requires specific study to examine the architecture of wellbeing it can achieve.

Figure 1. Mapping the Well Schools framework to Public Health England’s eight principles for promoting wellbeing in schools.

School programs for supporting educational outcomes are widely studied and often consider quantitative outcomes and impact (Goldberg et al., 2019) whereas direct engagement with stakeholders in understanding the implementation process and practice lags behind (Durlak et al., 2011; Wigelsworth et al., 2016). Context and variability in implementation are crucial aspects to be examined. Therefore, the current project has centralised capturing implementation and the voice of key school stakeholders to collect profiles of experiences promoting wellbeing. School evaluation work should incorporate comprehensive qualitative case studies to evaluate and understand the complexity of implementation and process (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). Such insight can help explain intervention implementation and impact, and identify, in this case, the Well School characteristics for success support recommendations for future practice and policy (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019).

The current work explored what a Well School looks like, considered common approaches schools are implementing, and evaluated the impact of such approaches on wellbeing and education outcomes. The main objective was to explore what provisions were in place to support wellbeing and understand the factors that affected the implementation of Well Schools, as well as the perceived impact. We were interested in finding examples of good practice, how challenges were addressed, and opportunities realised. This was captured within two research questions:

1. What are schools doing as part of Well Schools, and what factors are affecting implementation?

2. What was the impact of embedding the Well Schools approach, and what are some of the factors affecting this?

2 Methods

2.1 Research design

The data reported in the paper draws from a larger mixed-method project that used a case study approach to explore both the implementation of Well Schools and what factors are affecting implementation, alongside understanding the impact of Well Schools for schools, teachers, and pupils, and what factors affect this. The larger project collected quantitative data through surveys measuring both teacher and pupil wellbeing, supporting comparisons with national data and established benchmarks, as well as qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with school staff and relevant document analysis to understand processes.

The data reported within the current paper focuses on the rich set of qualitative interviews collected via semi-structured interviews with school leaders and class teachers, and aimed to examine school provision, decision-making, and perceptions of impact, and allowed us to capture depth of experience and perceptions of Well Schools (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This approach supports a narrative on good practice, reflecting on challenges faced by embedding a whole school wellbeing initiative and offers advice on solutions and opportunities (Clarke et al., 2021), and crucially, the context that underpins them (Skivington et al., 2021). Such a qualitative design was used to elicit rich, detailed insight into experiences and perceptions, and allowed the recording of data to (i) document and understand how Well Schools was being implemented (including how and why this varies), (ii) research the adaptation processes (e.g., what adaptations are made, why, and what impact do they have?), and (iii) understand the context influencing successes and outcomes for all.

Ethical approval for the project was sought from the University of Manchester University Research Ethics Committee. Opt-in informed and signed consent procedures were used with all teachers ahead of interviews. Ethical working in line with the British Psychological Society (2021) was maintained throughout.

2.2 Sample and participants

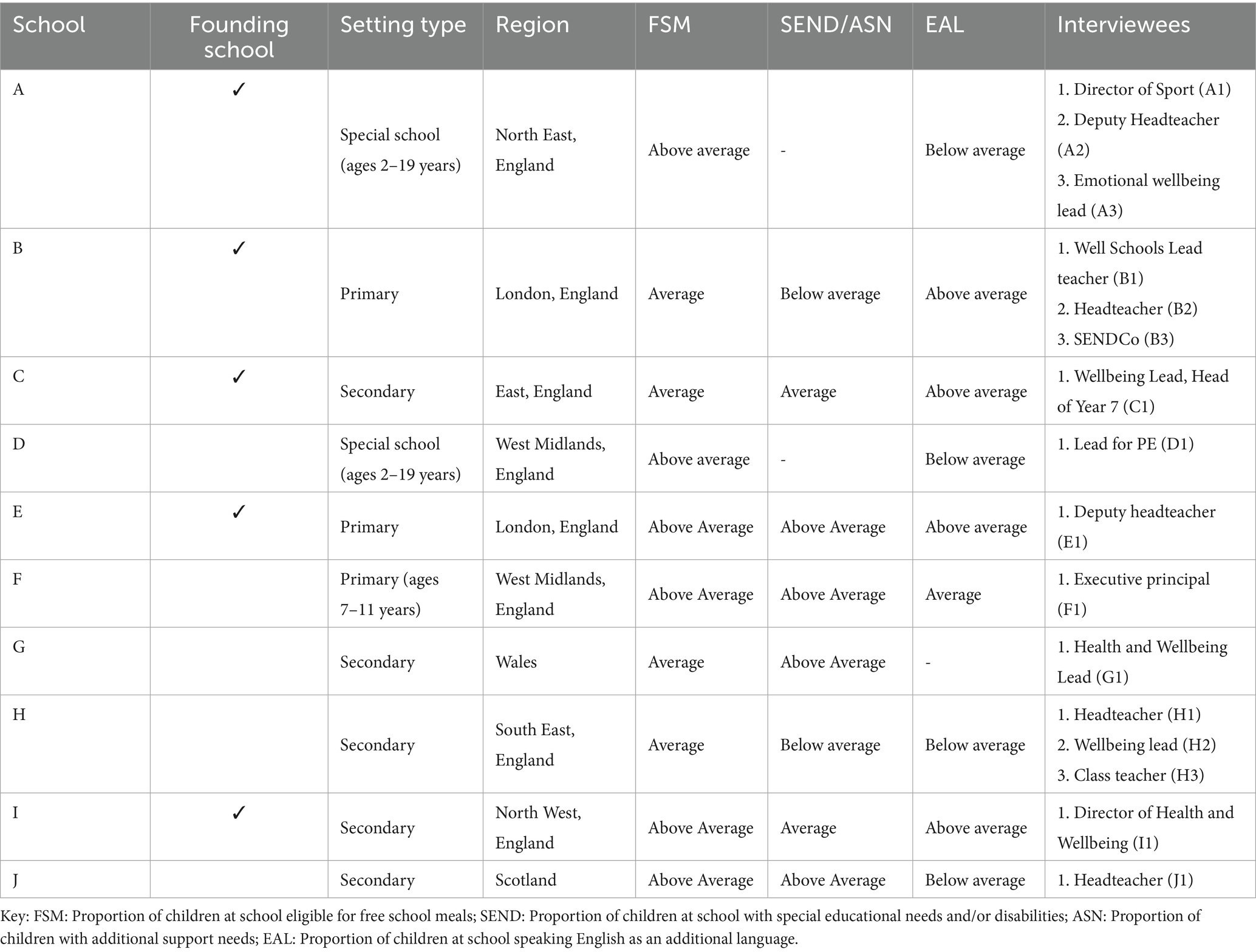

Ten schools (Table 1) were recruited representing diversity in settings (mainstream primary and secondary schools, and alternative provision special schools), geographical areas of the UK (England, Scotland and Wales), variation in school demographics such as proportion of children eligible for free school meals (FSM), special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) and English as an additional language (EAL). Five of the 10 schools were founding schools representing their early involvement when the Well Schools approach was being established in 2020. Sixteen interviews involved a range of relevant stakeholders who were sourced across these 10 schools. These included interviews held with Well School leads, headteachers, deputy headteachers, class teachers, special educational needs coordinators, and wellbeing leads. Table 1 offers specific details about each school, reflecting the diverse voices that were captured and shaped the data.

2.3 Data collection

Semi-structured interviews provided a set of prescribed questions (informed by theory and frameworks) while allowing scope for interviewees to discuss related content (Braun and Clarke, 2013). The flexibility in this approach suited exploring ideas, experiences, and diversity and nuances in practice across the 10 different school contexts. Semi-structured interviews explored the range of stages and processes of implementation. Foundations, prior practice, expectations, role of professionals involved in supporting staff and pupils, planning for implementation, implementation progress on three pillars, factors affecting implementation (e.g., barriers, competing pressures, expectations vs. reality), barriers and opportunities (such as equipment, provision, timetabling), attitudes and opinions, indicators of impact and sustainability, alongside recommendations for future delivery and ensuring lasting impact.

2.4 Analysis

A hybrid thematic analysis was conducted on a dataset composed of interviews from 16 staff who volunteered to share their perspectives. The approach to analysis involved a deductive phase and a subsequent inductive phase. Thematic analysis was applied to the interview data to enable researchers to address both broad and narrow research questions about individuals’ experiences, views, and perceptions (Braun and Clarke, 2019). A summary of this coding process is provided. Multiple researchers were involved in the coding process, and this supported a reflective and detailed appraisal of the coding process.

2.4.1 Interview coding

A hybrid approach was used, meaning the coding and thematic development attended to both deductive ideas as a priori categories of possible themes, such as those informed by the school implementation literature base and policy, and the Well School ideology and framework, as well as inductive aspects. Thus, when coding, a combination of deductive and inductive approaches was used to accurately represent participant voices and allow for unanticipated content. This hybrid approach to thematic analysis facilitates the development of themes employing both theory and a data-driven approach using the six steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006) and exemplified by Xu and Zammit (2020) and Byrne (2022).

Coding was conducted using NVivo version 12 and followed a two-step process. First, this began with generating theory-driven codes, which were informed by implementation and education theory and policy, as well as the program framework itself. These deductive codes were informed by evidence and this included (i) pre-existing literature and policy of wellbeing and whole school provision (e.g., Department for Education, 2021), (ii) the Well School framework, and (iii) implementation literature, e.g., Theoretical Domains Framework to explore implementation and to identify influences on behavior related to implementation including barriers and facilitators (Atkins et al., 2017; Fohlin et al., 2021). To ensure rigor two coders coded a sample of scripts and discussed these, to appraise and examine codes and applicability of the framework in a reflexive manner (Byrne, 2022). Initial coding used pre-defined deductive codes and supported a discussion of how these were used and applied, and a reflection on this process (Byrne, 2022). These insights informed and updated the coding framework, and when necessary, edits were applied to deductive codes. A second coding, taking an inductive approach, further examined the data, accommodating a ground-up approach, recognising the depth of teachers’ perceptions and reported experiences. The coding scheme1 maps out codes, a description, and for deductive codes identifies the evidence that informed their preparation. Application and auditing of the coding approach, employing two coders and coding discussions to support interpretation, supported the rigor and trustworthiness of the data (Nowell et al., 2017).

3 Findings

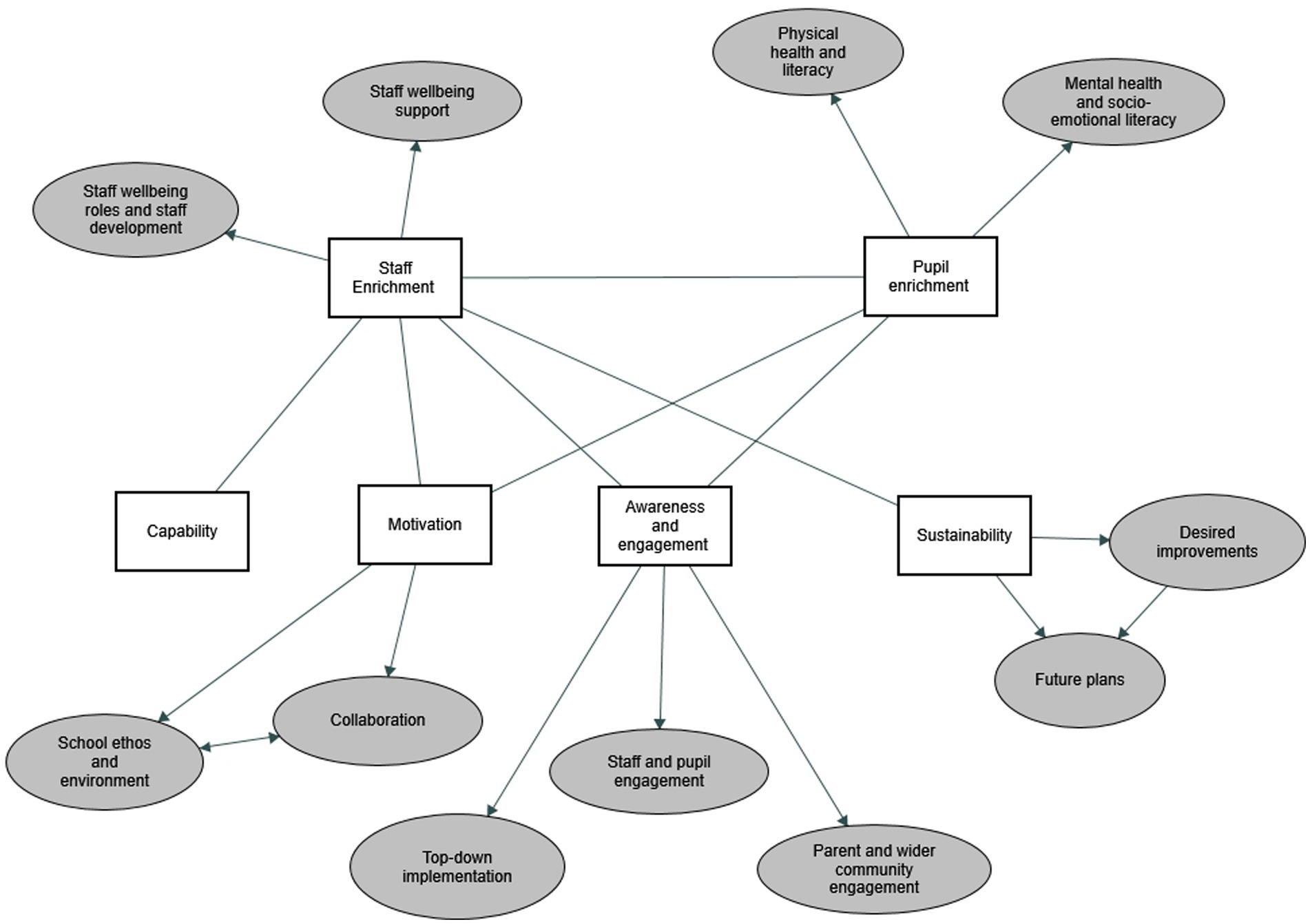

Elements of the deductive framework were prepared to focus on the three pillars (well-led, well-prepared, and well-equipped) from the Well Schools framework. During analysis and inductive approaches allowed the identification of patterns in engagement and interactions between the pillars of the Well School framework. Interviewees spoke about the active and practical elements that sat within each Well School pillar, and much overlap in practice. Consequently, the a priori coding framework was adapted to reflect the way participants talked about Well Schools. Such refinement and development are a vital component of a hybrid thematic analysis approach. The knowledge gained during the coding phases supported the arrangement of themes as best reflecting the knowledge shared by interviewees. Figure 2 presents an overview of themes and sub-themes and is summarised below:

• Theme 1 “staff enrichment” reflected that effective leadership involved enriching staff job satisfaction through supporting staff development and wellbeing days.

• Theme 2 “pupil enrichment” incorporates elements of the model, in particular “well-prepared” and “well-equipped” strands, as equipping pupils with socio-emotional literacy occurred alongside focusing on their mental and physical health. Participants often described these approaches hand-in-hand, recognising a practical and theoretical overlap in strategies to both prepare and equip pupils simultaneously.

• Theme 3 “motivation” reflected participants talked about it as a reason for getting involved, and for staying involved in Well Schools, and included ethos and environment.

• Theme 4 “capability" considered barriers and facilitators to implementing Well Schools.

• Theme 5 “awareness and engagement” recognised elements of impact as well as how aware the different stakeholders were of Well Schools, and also to what extent they engaged with it.

• Finally, sustainability (theme 6) captured content regarding future plans and practice.

3.1 Theme 1: staff enrichment

Staff enrichment in Well Schools connects wellbeing strategies with professional development. Schools adopted both structured policies and formal strategies, e.g., signing the Education Staff Wellbeing Charter (a voluntary declaration developed collaboratively by the Department for Education, Ofsted, unions and sector bodies that invites state-funded schools and colleges in England to commit publicly to protecting, promoting and enhancing the mental health and wellbeing of every member of their education community), and more informal initiatives to improve staff health, morale, and retention. The need for nuanced approaches required from schools to support staff wellbeing and health was clear, alongside consideration of availability and fit. A positive impact on the staff-centered approach to wellbeing was evident, and staff involved in the interviews reported that their wellbeing was enhanced through a range of lifestyle initiatives. School D connected better attendance with wellbeing support post-pandemic. School B feared low job satisfaction and retention without these initiatives. One headteacher observed:

“[Staff are] fresh, they're happy, they love their job, and so they teach better because they're in a better place. If they're happy and they're relaxed, then the lessons they teach are generally going to be better, so yeah we see that every day. We get comments regularly by visitors about the feel of the school, that it feels different it feels, the buzz of the school staff are happy staff are smiling”. (Participant B2—headteacher)

3.1.1 Staff wellbeing support

3.1.1.1 Staff wellbeing charter

The Education Staff Wellbeing Charter provided a visible framework for wellbeing strategies, enhancing shared understanding. One headteacher reflected, “I’ve worked with the DfE on their Staff Wellbeing Charter, it’s why I’m part of Well Schools” (participant H1—headteacher). Another school in Scotland adapted the Charter to suit the local context, appointing an external wellbeing coordinator to gather staff feedback confidentially and develop a bottom-up wellbeing model (participant J1—headteacher). However, they raised concerns that the charter was not feasible because of the lack of cultural transferability across English and Scottish Education, choosing to adapt and implement their own version.

3.1.1.2 Workload support

Managing workload was reported as integral to staff wellbeing. Senior leadership ensured all staff had acceptable and manageable workloads and made efforts to incorporate staff perspectives, where staff are encouraged to challenge ineffective working practices and propose more productive alternatives. Well Schools provide several resources that support staff workload, such as “workload reduction toolkits” and share practice across schools on how best to achieve this. School B implemented a “Keep, Tweak, or Ditch” process to eliminate inefficiencies:

“… for many years we did a process called ‘keep tweak ditch’, where we looked at everything that we were doing and we got all different teams to kind of say yes we should keep this, this needs to go because it’s making no demonstrable difference to children or to what we’re doing at the school and these are things that are that we think we should keep but this is how we need to tweak them to make them more effective and that is a really good way of, you know, that workload.” (Participant B1—Well Schools lead teacher)

3.1.1.3 Mental health support

Schools supported staff mental health through training and coaching. Two schools trained staff as Mental Health First Aiders. School J offered “a lot of wellbeing resources for staff,” including “one-to-one coaching, obviously our occ health and that side of things, and support of our staff wellbeing” (participant J1—headteacher), noting its role in supporting the mental health needs of new staff who may be more likely to become overwhelmed with the demands of teaching.

3.1.1.4 Recognition programs

Daily and weekly recognition boosted staff morale and acknowledged staff achievement and dedication to their role. School H’s initiatives included a “personal cheerleader program” and a token-passing mug, a “mug that is passed from colleague to colleague when they see someone do something good as a means to offer a small gesture of recognition and appreciation” (participant H2—Wellbeing lead). A teacher at the school reflected on the personal impact of this approach “‘I was having a really bad day and I’ve got this, and it’s just highlighted why I do this job and it’s helped me feel happier’” (participant H3—class teacher). School A held weekly recognition events with small rewards (e.g., sweet treats).

3.1.1.5 Personal lifestyle program

Staff wellbeing was further supported through a range of lifestyle initiatives. School A earned a “Better Health at Work” award, facilitated health advocacy, and themed activities such as mindfulness, walking, cooking, and awareness sessions. As one staff member explained, “We feel like we are getting our… handle back on this wellbeing” (participant A1—Director of Sport). Staff sought training to become “health advocates.” This fostered activity that encouraged healthy lifestyles and extended to themed monthly activities that raised awareness of different issues, such as alcohol consumption and healthy eating. Wider activity involved the formation and development of clubs to encourage physical and creative activity, such as cycling, walking, crochet, and cooking.

“Resilience and assertiveness training, menopause, breast cancer awareness, basic mental health training, we have got people coming in and delivering after-school sessions around mindfulness and meditation… We have cycling groups we have walking groups, we have cooking groups, we have crochet groups. So, we feel, we feel like we’re getting our, you know, getting a handle back on this well led this aspect, this wellbeing, and the governors are on board as well.” (Participant A2—headteacher)

School J offered staff the same residential retreat as they do for pupils, evidencing the mutual focus on staff and pupil wellbeing: “All of my leadership team have gone through values-based leadership residential for five days” (participant J1—headteacher).

3.1.2 Staff wellbeing roles and development

Wellbeing leadership was either top-down or distributed, and organisation and division of roles were especially important in larger secondary schools. School H’s senior team viewed staff as whole individuals and advocated for a wellbeing culture driven by the senior leadership team, who view staff as their greatest resource and believe in supporting and promoting their wellbeing and health: “The same thought process that I have about pupils… I have about every member of staff in the school” (participant H1—headteacher). This approach was directly praised in the school’s Ofsted report:

“Leaders are sensitive to the amount of work that staff do. Staff feel that leaders listen to them, and they feel valued by the school leaders. They appreciate the importance that leaders give to their wellbeing.” (School H Ofsted report 2020)

Other schools assigned wellbeing responsibilities to specific roles (e.g., coordinators, mental health leads), enabling participatory ownership and autonomy. School H, as a large secondary school, specifically developed a range of leadership roles and a specific wellbeing lead under the Well School framework to support leadership channels whole school. Both approaches were valued by staff and regarded as contributing to a whole-school wellbeing approach.

3.2 Theme 2: pupil enrichment

Pupil enrichment encompasses strategies used by schools to support students’ physical, mental, and socio-emotional wellbeing. Across schools, educators reported the use of named initiatives, collaboration with external services, and bespoke in-school approaches designed to enhance students’ health and wellbeing. Physical activity was often an entry point for broader development. These initiatives were shown to improve academic performance and focus. It is also evident that elements across the pupil enrichment theme fed into how pupils performed academically and engaged with academic learning, and schools were reporting happier pupils.

“What's worked well has been what we are seeing is the links between physical health and attention in class so we’re seeing that by running daily fitness sessions and by, by having our physical health lessons, sports days, work out Wednesday, all of those initiatives, active learning breaks, all of those initiatives that are working at the moment we are seeing an improvement with attention and focus when it comes to reading or writing so that’s like a real big benefit that we’re seeing.” (Participant B1—Well Schools lead teacher)

The collective approaches towards pupil enrichment demonstrated interlinked reported benefits across physical, emotional, and academic domains, fueling a holistic positioning and comprehension of wellbeing that created an enriched environment for pupils.

3.2.1 Physical health and literacy

Across all participating schools, physical health and literacy were focal areas. All schools recognised the link between physical activity and overall wellbeing in a multitude of ways.

3.2.1.1 High-quality PE and sports enrichment

Schools reported a broad and inclusive physical education (PE) curriculum. School D, for example, offered both team and individual sports—ranging from team sports such as hockey, rugby, basketball, and football to individual sports such as sailing, climbing, cycling, and trampolining. Several schools and teachers made deliberate efforts to move away from competitive sports toward inclusive physical activities that focus, and celebrate individual development. One primary school headteacher explained, “a progressive curriculum that is, very much focused on, children developing the skills and understanding in those areas that they need to be physically and mentally well. Our physical health curriculum is very much focused on physical health rather than sport” (participant B2—headteacher). While another teacher at the same school stated:

“The fitness sessions they're all about getting out, running around, playing a game etc., just getting them pumped, and that’s all linked to, you know, obesity in the area. It’s about health, and that’s one thing which we've seen huge differences we actually monitor that. We've got a physical health lead who actually monitors the fitness of the children. It’s just really interesting just to see what that impact is over the space of three years, it’s been it’s really been great.” (Participant B3—SENDCo)

Schools A and D, special schools with pupils with specific and complex needs, described tailoring physical activity to meet the unique needs of their pupils.

“Some strategies are not… quite right for our school, but we do similar things… We don’t do the mile a day because it’s not appropriate for our pupils, but we do walking to help build that stamina and that wellbeing.” (Participant D1—lead for PE)

Within the special schools, teachers used physical activity sessions to observe pupils’ fine and gross motor development that aided early intervention. However, a significant challenge emerged in ensuring physical health habits continued outside of school. One participant noted the challenges that cut across school provision and maintaining wellbeing and physical literacy across holiday periods: “We have these fantastically well-rounded children in school, but then we do not have them for six weeks in the holidays, and we want it to carry on outside of the school building” (participant D1—lead for PE). Teachers at the special schools emphasised the socio-emotional benefits of sport, reflecting how engaging in physical activity opportunities supports the consolidation and development of wider learning:

“When I'm teaching in PE, I might be yes I'm looking at the physical side but I'm also looking at the emotional side as well and we’re looking at the social skills, you know, team work and communication it underpins everything that we do and that’s what everybody does in their lessons rather than it just being ‘right you're learning x y and z today.”(Participant D1—lead for PE)

To address socio-economic barriers, schools like School J provided equipment such as bicycles and organised cycling lessons and trips to ensure equitable access to physical development opportunities. One participant shared, “We connect with the sailing lake down the road…we value, massively value, ski trips and Duke of Edinburgh and bush craft trips” (participant H1—headteacher).

3.2.1.2 Outdoor education and learning

Outdoor learning was particularly valued in primary and special education settings. Schools described moving learning beyond the classroom to improve engagement and wellbeing: “Everything is outdoor… outdoor learning in maths… in English… making it much more creative for those children” (participant B3—SENDCo). School A incorporated a specific intervention, the Outdoor Play and Learning (OPAL) program, a school improvement program focused on enhancing the quality of play for children and learning, to facilitate outdoor experiences, including nature walks and hands-on learning. Other schools saw the benefits of outdoor environments; they were seen as therapeutic and beneficial for students who struggle in traditional settings. It “supports some of our learners who, in particular, find it difficult to be in the classrooms all day” (participant J1—headteacher). A primary school participant explained, “Some children… struggle with the rigidity of the classroom… over there, they are solving problems with their hands… building, and they are making things” (participant E1—deputy headteacher). Outdoor learning roles were formalised in some schools. School B had an outdoor lead who developed initiatives such as an “edible playground.” Meanwhile, School J was in the process of hiring a full-time Outdoor Educator to enhance its already diverse curriculum that included mechanics and gardening.

3.2.2 Mental health and socio-emotional literacy

Most schools employed programs to support mental health and social–emotional learning. These programs often replaced punitive discipline with self-regulation strategies. One primary school highlighted, “It’s not us telling the children ‘you have done this’… it’s about them supporting their own regulation… we have regulation break-out corners in each room” (participant B3—SENDCo). Mental health charities like Place2Be were used by some schools for counselling and emotional support. Small group interventions addressed self-esteem and emotional resilience. This includes one-to-one counselling support and small groups focusing on developing skills such as “self-esteem building,” which serves to remind pupils “this is where you come for support” (participant C1—wellbeing lead).

Secondary schools advocated for and provided students with leadership opportunities that enhanced emotional and social wellbeing. Roles such as sports captains, anti-bullying ambassadors, transition mentors, and school council members empowered students. Providing leadership opportunities for secondary and sixth form pupils enabled building of self-esteem and confidence, and provided experience of a responsible position that can be beneficial for addressing behavioral issues and role models for younger pupils:

“Everybody likes PE one in one way or another, so it’s really quite nice to if we've got a young person who’s presenting quite challenging and not wanting to be in the classroom, then giving them the responsibility of working with smaller young people in a PE lesson.” (Participant A2—deputy headteacher)

3.3 Theme 3: motivation

The motivation leading to getting involved and joining the Well Schools movement was rooted in the desire to embed a culture that prioritises the holistic wellbeing of pupils and staff. Schools reported the Well Schools framework “naturally” aligned with their existing ethos and offered a structured approach to enhance and evaluate wellbeing practices.

3.3.1 School ethos and environment

Schools consistently described the Well Schools framework as complementary to pre-existing wellbeing initiatives. Rather than introducing a new programme, it provided a cohesive structure that enabled school leaders to evaluate and align their current work; it “just embedded quite naturally into the school life” (participant H3 – class teacher). As one school leader noted,

“We see Well Schools as an umbrella under which we can run our organization in the best possible way for all of the human beings within it… basically everything we do as a school fits under this umbrella.” (Participant H1—headteacher)

The framework allowed schools to assess what was working, adapt what was not, and identify gaps. It enabled ongoing monitoring and reflection to ensure health and wellbeing strategies remained “impactful.” In the words of one special school leader: “We’ve probably been a Well School for quite a while… Our motivation then wasn’t to start the journey, it was probably more to fine-tune what we were doing” (participant A3—Emotional wellbeing lead).

Some schools emphasised a subtle implementation approach to avoid overburdening staff. “We have not made a thing of it because if you make a thing of something it becomes something people have to do, so we have just really put it there by stealth” (participant H1—headteacher). This approach helped embed Well Schools organically without it being perceived as an additional workload.

3.3.2 Collaboration

Collaboration with other schools was regarded as a catalyst that encouraged schools to be affiliated and become a “Well School.” Schools appreciated the opportunity to share ideas, successful practices, and experiences with others in the Well Schools community. As one participant expressed, “It’s a movement… schools are all coming together to share ideas, share knowledge of what’s successful… and spread that across more schools” (participant B3—SENDCo).

This sharing of practice provided reassurance and validation, and it offers “a confidence to continue on the path that you are on” (participant B2—headteacher). For special schools, learning and sharing with similar institutions proved particularly valuable. For example, School A connected with another special school to explore yoga techniques suited to their pupils’ diverse physical and emotional needs:

“It opens up a network for collaboration and sharing of ideas and things like that, you know, people who have, you know, unofficial research, you know, that, you know, have just tried things on the ground and things that have worked and things that haven’t worked and, you know, it’s time saving we haven’t got a lot of time in, in schools and know that helps massively.” (Participant A3—Emotional wellbeing lead)

The value of engagement with schools was noted to be time-efficient and empowering. Schools preferred learning from practical, contextually similar experiences rather than independently starting initiatives from theory or academic research. Such engagement extended to external organisations, such as mental health organisations, charities, and schemes. However, not all schools found collaboration straightforward. School J, based in Scotland highlighted difficulties in engaging with the broader Well Schools community due to differences in educational systems across the UK. The school’s headteacher suggested:

“If Youth Sport Trust could articulate that through what already exists [in my country], I think that would open up a huge number of schools …that would have their interest piqued.” (Participant J1—headteacher)

Most Well Schools envision that by promoting the Well Schools philosophy and principles, they hope to drive it forward and help other schools with their adoption to support better practices for health and wellbeing.

3.4 Theme 4: capability

Capability themes focused on barriers and facilitators to implementation, such as school systems, workload, competing priorities, and time constraints. A challenge for all participating schools in implementing the Well Schools framework was the constraints tied to time and capacity. Schools acknowledged that meaningful change required time, both for implementation and for gaining staff buy-in. Balancing competing priorities was not straightforward, as one participant explained:

“Time is always a challenge in schools, the opportunity to embed, the opportunity to bring these ideas. Even though change is good, too much change at too much is not, so it’s about the timing of when you introduce these things. Getting all staff on board to them, pitching the ideas to them, and giving it time to embed. If we all throw in too many ideas of too much change, then it’s just… ‘right, it’s the new thing, it’s the new thing, it’s the next thing, what's going to come next?’ We want staff to be behind it and get involved with it, so time is definitely a priority.” (Participant I1—Director of health and wellbeing)

Some schools adopted specific strategies to manage workload and prioritise wellbeing. As noted earlier, to support workload and teacher capacity, School B introduced a “Keep, Tweak and Ditch” model to ease unnecessary pressures on staff and enable them to focus on student wellbeing and relationship-building:

“Our staff are supported, we take away so much of the unnecessary bureaucracy so that our staff can just focus on what they love, which is working with kids.” (Participant B1—Well Schools lead teacher)

In secondary schools in particular, leadership teams recognised the need to restructure staff responsibilities to make room for wellbeing-focused roles.

“I can’t do both jobs, so it’s kind of been noted this year that the wellbeing lead needs to focus on that for staff and students, so currently we can definitely do more, but that’s obviously being addressed for September.” (Participant C1—Wellbeing Lead)

Despite time constraints, there were repeated reports that Well Schools saved time given the collaboration and resource sharing that being part of the network afforded. Before adopting the framework, teachers recalled questioning whether it would add to their burden. However, they later recognised its efficiency and ease of integration. School A, a special school, appreciated the network’s capacity to provide tested strategies and ready-made resources suited to diverse pupil needs: “It opens up a network for collaboration and sharing of ideas… it’s time saving, we have not got a lot of time in.” (Participant A3—Emotional wellbeing lead). Ultimately, while time limitations remain a concern, schools identified that their investment in the Well Schools network helped streamline wellbeing practices, reduce duplication, and support sustainable implementation across the school community.

3.5 Theme 5: awareness and engagement

Awareness and engagement with Well Schools concerned staff, pupils, and parents/family understanding of Well Schools and how this shaped and impacted implementation. The effective implementation of the Well Schools framework was shaped by awareness and engagement across staff, pupils, and parents. Central to this process was strong leadership, inclusive practices, and efforts to extend the ethos of wellbeing across the wider school community.

3.5.1 Top-down implementation

In most schools, implementation was led by senior leadership teams (SLT) who promote the culture of Well Schools across the whole school community. The approach was modular, with each SLT member responsible for specific aspects of wellbeing.

“It’s not simply led in like a hierarchical working manner, it’s very much (laughs)… each member of SLT oversees their team and makes those decisions based on what they're seeing day in day out, which means our teams are heard.” (Participant B3—SENDCo)

School H exemplified this structure through collaborative planning and regular communication between the headteacher, wellbeing lead, safeguarding lead, and assistant head. The Well Schools framework has also facilitated consistent dissemination of wellbeing strategies:

“We’ve learnt so much about wellbeing and that’s been transferred onto staff from leaders… that’s shared and trickled down to us, throughout staff training throughout briefings…” (Participant B2—headteacher)

3.5.2 Staff and pupil engagement

While strong leadership is important, whole school engagement was regarded as essential when developing a ‘Well Culture’. Both staff and pupil voices were valued. Schools fostered feedback directly with regular surveys and other means of engaging staff and pupils. Crucially, the feedback was regarded as directly supporting wellbeing initiatives and creating change:

“Staff coming together and creating that vision as well meant that everybody played a part, and everybody felt that they had invested in this journey and this process.” (Participant F1—Executive principal)

Pupil involvement also played a critical role. Schools highlighted the importance of children evaluating the health curriculum and acting as wellbeing ambassadors: “children’s voice on whether or not they feel the health curriculum’s having a positive impact on their learning” (participant B1—Well Schools lead teacher).

School E, for instance, implemented a daily whole-school physical activity initiative, encouraging pupils, staff, and even parents to lead.

“…that’s the whole school, everyone coming together, something different every time, but we’re really trying to get the children to lead [and] we involve the parents […] it’s just raising the profile of actually being healthy and sport, you know, getting out and getting active every day.” (Participant E1—deputy headteacher)

3.5.3 Parent and wider community engagement

Schools also aimed to engage parents and the wider community, recognising the value of consistency between home and school wellbeing efforts. However, some schools found it challenging to maintain parental involvement, particularly during school holidays. To address this, schools introduced strategies like parent events and workshops. One school hosted “parent gym sessions” focused on parenting, healthy eating, and emotional wellbeing: “The parents are begging for it… we have got children coming from other schools to join our school” (participant B3—SENDCo).

Ultimately, schools acknowledged that sustaining a Well Schools ethos required ongoing communication, shared responsibility, and cross-community collaboration:

“The leadership team we support that, but it goes out wider than that, you know, it’s about teachers, it’s about the support staff, it’s about the families, it’s about the borough as well there's so many different aspects of it, and actually getting all of those parties together that was well led, I think.” (Participant B3—SENDCo)

The connection between wellbeing and the recognition of its mental health benefits underpins the opportunity created by schools to build, develop, and maintain a relationship with families that reflects a holistic approach to wellbeing.

3.6 Theme 6: sustainability

All schools confirmed their commitment to continuing with Well Schools and expressed intentions to adapt and develop their approach to better meet their unique contexts and needs. This adaptability is a valued feature of the framework and central to sustaining Well Schools’ ethos in the longer term.

3.6.1 Future plan for well schools

Schools expressed a strong interest in improving how they monitor the impact of the framework, particularly in considering its long-term benefits for their communities. Most schools stated they would continue to use tools that enable regular feedback, such as staff and pupil wellness surveys, strategic meetings, and may extend to input from external agencies to track progress. These measures would guide decisions and ensure that wellbeing initiatives remain impactful and aligned with their goals.

“Moving forward and to identify where we are doing well and maybe where we have areas to improve… We look at maybe things that we can take off our Well Schools list or not or things we need to add on, and areas where we need to target for improvement.” (Participant H1—headteacher)

Another emerging priority was sharing the Well Schools philosophy more widely as it embodies “where the vast majority see education going, where they want education going, this is what people want for their children this is what, everybody wants out of a future of education,” however, they understand that this requires quite a shift in current educational thinking, so it is important to consider “just how to communicate that” (participant B2—headteacher). One primary school highlighted the importance of extending this ethos into their local secondary schools to ensure continuity in students’ wellbeing experiences.

“I don’t want everything that we’re doing to stop, and the children to lose focus or lose sight of how, you know, we’ve built something that’s so magnificent that can carry them right through to when they’re adults, for it to stop at the secondary because, you know, there’s like three thousand children or however many there are there, and they get lost.” (Participant F1—Executive principal)

3.6.2 Desired improvements

Several schools voiced the need to raise the profile of Well Schools and to better communicate and share effective practices with a wider network: “You know, I mean it’s amazing over a thousand schools that have joined up, but you know, what is the best way to communicate that to the other 21,000?” (participant B2—headteacher). Three schools were keen to continue to raise awareness and promote the Well Schools approach:

“It’s continuing to try to take that message, more widely and to try to influence more schools and more school leaders, more teachers to think about what they are doing in terms of the Well School approach and, you know, how they can bring that into their school and like I say continuing to be reflective, continuing to, you know, reflect on what we’re doing to refine it to look at others and what they’re doing, you know, continue to better understand the impact.” (Participant B2—headteacher)

School J in Scotland called for Well Schools to better align with the devolved policy in each of the four nations that make up the UK. The terminology and framing of Well Schools were perceived as predominantly English, potentially discouraging uptake in other UK regions: “It immediately makes you think; okay, so that’s for England, that’s not for us” (participant J1—headteacher). However, this school also recognised the framework’s value in bringing together various wellbeing initiatives under one coherent structure.

“I think the great potential in the Well Schools framework is that it brings all [initiatives] together potentially under one approach and one umbrella… and if we could or if Youth Sport Trust could articulate that through what already exists [in my country], I think that would open up a huge number of schools [in my country] that would have their interest pricked.” (Participant J1—headteacher)

Schools remained hopeful that expanding networks and clarifying communication could help foster a broader movement towards wellbeing-centered education across the UK.

4 Discussion

The current paper explored contextualised approaches from a range of ten diverse school settings across the UK that each adopted and adapted a whole school model of wellbeing to achieve a bespoke, feasible, and socially valid approach that schools can successfully implement, develop, and maintain. The aim of this paper was to collect and consider detailed insights regarding Well Schools’ provision and examine factors affecting implementation (research question 1). The research being reported recognised that the Well Schools framework was a multifaceted approach to supporting the wellbeing of pupils (Khanna et al., 2024) and teachers (Ozturk et al., 2024). It’s an optimal and flexible strategy that fueled the development and application of a novel and timely framework for supporting and examining whole school wellbeing in a real-world context. It was evident that schools used bespoke approaches to support their local context, teachers, and school context and cohort of pupils. The approaches reported suggest a multitude of ways to support teacher and pupil wellbeing and highlight the decision-making underpinning this. It also emphasises the specific course on pupil-centered approaches.

Secondly, we aimed to capture the perceived impact of embedding the Well Schools approach and what some of the factors are that affect this (research question 2). Supporting children and young people’s wellbeing is firmly part of a recovery and future plan for education (Department for Education, 2023). Thus, the experiences from these 10 schools are timely, providing important and valuable insights regarding how their approach supported an interpretation of and achieved a contextualised approach to whole school wellbeing provision. All schools report perceived impact in terms of wellbeing across their schools. The experience of the 10 schools emphasises that prioritising wellbeing via a whole school approach can lead to positive outcomes for pupils and teachers.

4.1 Well schools implementation and factors affecting implementation

For whole school wellbeing provision to be successful it must be an integrated systems approach (Glazzard and Bostwick, 2024), an idea not unnoticed by children and young people themselves (Demkowicz et al., 2023), and this message was at the center of the Well Schools approach, and it was evident that whole school engagement was key to developing a ‘Well Culture’. Pivotal to the successful accounts of the ten schools was the opportunity to prioritise wellbeing and develop a whole school approach that recognised that doing so would lead to a more cohesive and productive learning environment for all. This ‘buy-in’ was needed from the outset for successful implementation. Successful implementation of Well Schools must be driven by senior leadership (Public Health England, 2015, 2019). Across all 10 schools was evidence of senior leadership driving and supporting Well Schools implementation, through staffing, curriculum planning, and sensitive leadership.

Another critical aspect to successful implementation was the flexibility offered and a recognition that ‘one size does not fit all’. For example, increased leadership and staffing roles adopted by large secondary schools, tailored physical, social, and emotional provision suitable for children attending special schools. The Well Schools framework encouraged adaptation to develop provision suitable to the individual school context. This is highlighted by the diverse range of approaches schools were adopting to support whole school wellbeing, and how they used the Well Schools framework as a guide to structure and strategise, as well as to monitor and evaluate practice. The benefits of the Well Schools approach offered an “umbrella” framework that allows the principles of Well Schools to be organised and evaluated, and other provisions to be structured and monitored. The Well Schools approach sympathised with the physical and emotional health provision already being implemented in many schools and supported the development of current practice. The integration of Well Schools into an existing school ethos was facilitated by the feasibility and suitability of the framework; indeed, it was found to complement many existing practices while also allowing a re-focus and sharpening of approaches to support staff and pupil wellbeing – and it was this opportunity that motivated schools to join Well Schools.

Another benefit of belonging to the Well Schools community was being part of a network of schools providing an opportunity for schools to build relationships, collaborate, and learn from other like-minded schools. Therefore, the promotion of Well Schools can facilitate good practice and help other schools adopt better practices for health and wellbeing, and practices that can be meaningfully integrated alongside school activity (that may extend to targeted or universal interventions).

4.1.1 Pupil-centered provision to nurture wellbeing

Physical health and socio-emotional literacy were the leading focus of wellbeing provision across all schools with regard to preparing and equipping pupils. Schools adopted many pupil-centered approaches and recognised the importance of providing a broader, richer curriculum to support the development of skills and strategies to manage emotional wellbeing and mental health, as well as academic learning. Physical health and activity are identified as key ingredients to pupil wellbeing (Hennessey et al., 2024), although it must be recognised that this may be attributable to the Youth Sport Trust’s focus on PE, school sport, and physical activity initiatives. Schools adopted a range of pupil-centered approaches to physical health, including:

• Educating pupils on the importance of physical activity, good sleep, hygiene, and maintaining a balanced diet.

• Using sports and mobility to support mental and physical health.

• Offering a diverse range of sports and extracurricular activities and recognising the importance of making physical activity accessible for pupils’ individual needs.

• Recognising the benefits of outdoor learning.

• Offering pupils psycho-social development through a variety of whole school, universal, and targeted provision and programs to support the development of skills and strategies to manage emotional wellbeing and mental health.

• Valuing pupil voice and creating pupil leadership roles and pupil ambassadors to provide feedback and share pupil perspectives on how best to support them, bridging the gap between staff and pupils.

Physical activity is a recognised mechanism for supporting wellbeing and mental health (Rodriguez-Ayllon et al., 2019). School physical activity interventions are effective approaches to improve social and emotional wellbeing in children and young people (Andermo et al., 2020) and can promote skills such as resilience and social relationships (Sport England, 2024). Increased physical activity can also operate as a protective factor and offer the potential to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents (Bell et al., 2019). Indeed, schools recognised to promote wellbeing have multi-faceted benefits by placing emphasis on physical activity, movement, and access to outdoor learning.

4.2 The impact of embedding well schools

All Well Schools had plans to sustain practice and emphasised the benefits and positive impact on their school. Staff wellbeing was supported through a combination of approaches and was led top-down by senior leadership: Staff Wellbeing Charter allows schools to monitor and show their commitment to Staff Wellbeing, many schools set up designated staff wellbeing leads. A wellbeing culture was driven by the senior leadership team to ensure workload is acceptable and manageable, offer staff mental health support, and recognise staff achievement. This aligns with Ozturk et al. (2024), who argue that a holistic approach to conceptualising teacher wellbeing must accommodate feelings of negativity and deficiency, positivity and flourishing, and professionalism; each was traceable and recognised within strategies for support offered across Well Schools. Advocating for staff wellbeing, staff recognition, and allowing staff to have autonomy over staff enrichment in their schools can lead to positive outcomes for teachers and for an effective learning environment. In the UK, there is converging evidence regarding the multiple stressors that impact teacher retention; favorable conditions within schools as workplaces can be difficult to achieve (Taberner and MacQuarrie, 2025). Within these accounts of Well Schools, these stressors were evident, yet job satisfaction and teacher retention were identified as discrete benefits supported by becoming a Well School.

Supporting the wellbeing of teachers is also recognised to indirectly impact pupil academic outcomes (Granziera et al., 2023). Increased teacher wellbeing has implications for pupils as increased feelings of teacher wellbeing are associated with a range of positive academic outcomes, such as academic achievement, motivation, and school satisfaction (Arens and Morin, 2016; Madigan and Kim, 2021; Shen et al., 2015). This converges with evidence from this study as benefits from being a Well School included reports that their pupils were happier and healthier, which in turn fueled pupil engagement with learning and boosted pupil academic performance. Pupil wellbeing and pupil academic learning are inextricably linked (Kaya and Erdem, 2021) and should not be considered separately.

4.3 Transferability of findings

These findings need to be contextualised and appreciated in the climate in which the current project and data were collected. Ten schools were involved, sourced from a wider population of more than 1,000 schools in the Well Schools community. Additional evidence is required to look at experiences within Well Schools located in countries other than England. The findings include evidence from one Welsh and one Scottish school, and this helps identify that the approach and techniques of this study can be suitable for use with a range of settings. Thus, there is a need to understand and contextualise experiences within all four nations of the United Kingdom, given their devolved education status.

Data were collected during the tail end of the COVID-19 pandemic when societies and education were endeavoring to adapt and acclimatise to their circumstances. Yet, this was a period of uncertainty and anxiety, especially for schools and young people (Department for Education, 2023). These are promising findings, especially viewed in the context of the current teaching and general political climate (e.g., disputes concerning workload, pay, and pending strike action). Yet, both pupil and teacher wellbeing are elusive and multi-faceted constructs; understanding what it is, how to measure it, and ultimately how to support it is much debated (Khanna et al., 2024; Ozturk et al., 2024). Consequently, the approach in the research adopted a specific framework that acquired insights into the variety of strategies adopted by Well Schools to look after their staff and pupil wellbeing, which is bespoke and adapted for individual school needs. A strength of this study relates to the bespoke techniques used to gain insights into teacher voice, which is much needed to support and grasp the nuances attached to wellbeing and school provision.

5 Conclusion

Such knowledge and insights supported the development of a series of illustrative school experiences that offer an account and insight into the nature of wellbeing situated within schools where the commitment to supporting wellbeing is linked to pupils, staff, and extends to the school community. Long-term accounts of school mental health and wellbeing initiatives are rare at the school level; thus, exploring and understanding the sustainability of such approaches is valuable (Clarke et al., 2021). There is a general call for such evidence across the education research field. The current evaluation identified that Well Schools offers a valuable opportunity to contribute new insights and understanding to this field, given the large number of schools that have joined and maintained their Well School status. There is a pressing call for closer examination of the sustainability of school wellbeing approaches, perhaps Well Schools is building an evidence base that mental and physical wellbeing and educational and social outcomes can be interwoven into a school landscape for the benefit of staff and pupils.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YWxleGFuZHJhLmhlbm5lc3NleUBtYW5jaGVzdGVyLmFjLnVr.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Manchester Proportionate University Research Ethics Committee (ref: 2022-13368-23243). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KP: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. CM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LV: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Youth Sport Trust.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to support a reduced word count and create Harvard reference list, authors fully reviewed and checked for accuracy. All quotations are verbatim from the participants.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Andermo, S., Hallgren, M., Nguyen, T. T. D., Jonsson, S., Petersen, S., Friberg, M., et al. (2020). School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine – Open 6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40798-020-00254-x

Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (2021). Closing the gap in child and youth mental health support: Insights from north West England. London: Anna Freud Centre.

Arens, A. K., and Morin, A. J. S. (2016). Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 108, 800–813. doi: 10.1037/edu0000105

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., et al. (2017). A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Bell, S. L., Audrey, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, A., and Campbell, R. (2019). The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16:138. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners : SAGE Publication.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 32, 513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). “The bioecological model of human development” in Handbook of child psychology. eds. W. Damon and R. M. Lerner. 6th ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 793–828.

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Cavanagh, M., McDowell, C., Connor Bones, U. O., Taggart, L., and Mulhall, P. (2024). The theoretical and evidence‐based components of whole school approaches: an international scoping review. Rev. Educ. 12:e3485. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3485

Clarke, A., Sorgenfrei, M., Mulcahy, J., Davie, P., Friedrich, C., and McBride, T. (2021) Adolescent mental health: A systematic review on the effectiveness of school-based interventions. London: EIF. Available online at: https://www.eif.org.uk/report/adolescent-mental-health-a-systematic-review-on-the-effectiveness-of-school-based-interventions

Day, C. (2008). Committed for life? Variations in teachers’ work, lives and effectiveness. J. Educ. Chang. 9, 243–260. doi: 10.1007/s10833-007-9054-6

Demkowicz, O., and Humphrey, N. (2019) Whole school approaches to promoting mental health: What does the evidence say? London: EBPU. Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/evidence-based-practice-unit/sites/evidence-based-practice-unit/files/evidencebriefing5_v1d7_completed_24.10.pdf

Demkowicz, O., Pert, K., Bond, C., Ashworth, E., Hennessey, A., and Bray, L. (2023). “We want it to be a culture”: children and young people’s perceptions of what underpins and undermines education-based wellbeing provision. BMC Public Health 23:1305. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15836-z

Department for Education (2021) Promoting children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing: a whole school or college approach. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1020249/Promoting_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_and_wellbeing.pdf (accessed July 29, 2025).

Department for Education (2023), State of the nation: children and young people’s wellbeing. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1134596/State_of_the_nation_2022_-_children_and_young_people_s_wellbeing.pdf (accessed July 29, 2025).

Department of Health and Social Care & Department for Education (2017), Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper (accessed July 29, 2025).

Durlak, J. A., and DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Early Intervention Foundation (2015). Social and emotional learning: Skills for life and work. London: EIF.

Education Endowment Foundation (2019). Implementation and process evaluation guidance for EEF evaluations. London: EEF.

Fohlin, L., Sedem, M., and Allodi, M. W. (2021). Teachers’ experiences of facilitators and barriers to implement theme-based cooperative learning in a Swedish context. Front. Educ. 6:663846. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.663846

Glazzard, J. (2019). A whole-school approach to supporting children and young people’s mental health. J. Public Ment. Health 18, 256–265. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-10-2018-0074

Glazzard, J., and Bostwick, R. (2024). A whole school approach to mental health and wellbeing. 2nd Edn. St Albans: Critical Publishing.

Goldberg, J. M., Sklad, M., Elfrink, T. R., Schreus, K. M. G., Bohlmeijer, E. T., and Clarke, A. M. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole-school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 755–782. doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0406-9

Granziera, H., Martin, A. J., and Collie, R. J. (2023). Teacher well-being and student achievement: a multilevel analysis. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 26, 279–291. doi: 10.1007/s11218-022-09751-1

Harding, S., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., Tilling, K., et al. (2019). Is teachers' mental health and wellbeing associated with students' mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord. 242, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080

Hennessey, A., MacQuarrie, S., Pert, K., Bagnall, C., and Squires, G. (2023). Embedding a whole-school culture for supporting teacher and pupil wellbeing: a well schools case study example. Psychol. Educ. Rev. 47, 22–28. doi: 10.53841/bpsper.2023.47.2.22

Hennessey, A., MacQuarrie, S., and Petersen, K. J. (2024). Exploring physical, subjective and psychological wellbeing profile membership in adolescents: a latent profile analysis. BMC Psychol. 12, 720–713. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-02196-5

Jarden, A., and Roache, A. (2023). What Is Wellbeing? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:5006. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20065006

Kaya, M., and Erdem, C. (2021). Students’ well-being and academic achievement: a meta-analysis study. Child Indic. Res. 14, 1743–1767. doi: 10.1007/s12187-021-09821-4

Khanna, D., Black, L., Panayiotou, M., Humphrey, N., and Demkowicz, O. (2024). Conceptualising and measuring adolescents’ hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Child Indic. Res. 17, 551–579. doi: 10.1007/s12187-024-10106-9

Lekamge, R. B., Jain, R., Sheen, J., Solanki, P., Zhou, Y., Romero, L., et al. (2025). Systematic review and Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of whole-school interventions promoting mental health and preventing risk behaviours in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 54, 271–289. doi: 10.1007/s10964-025-02135-6

Lester, L., Cefai, C., Cavioni, V., Barnes, A., and Cross, D. (2020). A whole-school approach to promoting staff wellbeing. Australian J. Teacher Educ. 45, 1–22. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n2.1

Lewallen, T. C., Hunt, H., Potts-Datema, W., Zaza, S., and Giles, W. (2015). The whole school, whole community, whole child model: a new approach for improving educational attainment and healthy development for students. J. Sch. Health 85, 729–739. doi: 10.1111/josh.12310

Madigan, D. J., and Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 105:101714. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714

Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., and Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 54, 77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International journal of qualitative. Methods 16. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

Ozturk, M., Wigelsworth, M., and Squires, G. (2024). A systematic review of primary school teachers’ wellbeing: room for a holistic approach. Front. Psychol. 15:1358424. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1358424

Petersen, K. J., Humphrey, N., and Qualter, P. (2020). Latent class analysis of mental health in middle childhood. Sch. Ment. Heal. 12, 786–800. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09384-9

Public Health England (2015). Promoting children and young people’s emotional health and wellbeing: A whole-school and college approach. London: PHE.

Public Health England (2019). Universal approaches to improving children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing: Findings of a special interest group. London: PHE.

Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., et al. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in mental health. Sports Med. 49, 1383–1410. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., and Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18:192. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Shen, B., McCaughtry, N., Martin, J., Garn, A., Kulik, N., and Fahlman, M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 519–532. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12089

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., et al. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. Br. Med. J. 374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061