- 1National Professional Master's in Physics Teaching, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 2Research Group Accessible Science Museums and Centers (Grupo MCCAC), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- 3Cecierj Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- 4Institute of Biosciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 5Research Group Culture and Historicity in Communication and Education in Science (CHOICES), São Paulo, Brazil

- 6Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

This exploratory and qualitative research aims to investigate how Science Capital is connected with accessibility. The study participants were adults, self-identified as blind or Deaf users of Brazilian Sign Language. They were invited to a guided visit at an exhibition at a science museum in Brazil, where data was collected through interviews, observations, and questionnaires. After conducting a thematic analysis, three main categories emerged: (1) Mechanisms of In/Exclusion in Museums and Science, (2) Scientific Content in Context and (3) Attitudes, Values, and Science-Related Dispositions. In each category, evidence shows correlations between accessibility indicators and dimensions of Science Capital. The results from the Science Capital Index questionnaires revealed changes in all participants' scores, with one of the most significant changes being how participants understood what it means to be a scientist. Our study advances previous research that used the Science Capital model by addressing its limitations when applied to people with disabilities. It also challenges the original British/Eurocentric design by proposing a more inclusive approach that considers structural inequalities and contextual barriers, particularly in the Global South.

1 Introduction

Despite ongoing efforts to advance diversity in science education, people with disabilities remain largely excluded from scientific communication, activities, careers and environments, whether in formal education or non-formal education (Sukhai and Mohler, 2017; UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2018; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020). Equity debates have often focused on social markers such as gender, race, and class (Archer et al., 2015), leaving disability comparatively under-addressed (Brinkman et al., 2023; Heck, 2024). This neglect has led to ongoing structural barriers that limit participation, representation, and a sense of belonging in STEM (Sukhai and Mohler, 2017; Daehn and Croxson, 2021), and little is discussed about how accessibility specifically shapes the opportunities of people with disabilities to engage with science learning, which is the gap this study aims to address.

Non-formal education spaces, such as science museums, hold critical potential for mitigating these inequities (Dawson, 2014; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020; Norberto Rocha, 2021), playing a vital role in promoting science communication and offering educational experiences that extend beyond the classroom. By providing interactive, experiential, and self-directed learning opportunities, museums allow visitors to engage with content through multiple senses—touching, feeling, interacting, moving, and interpreting objects in context—at their own pace, based on their emotions, interests, and personal narratives (Falk and Dierking, 2002; Hooper-Greenhill, 1994, 2006; Dawson, 2014). However, the extent to which these spaces are truly accessible and whether their strategies effectively support the needs of diverse audiences remains a pressing concern (Bezzon and Bizerra, 2024).

Over the past decades, science museums worldwide have begun to address inclusion more deliberately, implementing initiatives to improve accessibility and reduce exclusionary practices (Norberto Rocha et al., 2017). These efforts include transforming organizational culture, training staff, and developing targeted programs to engage underserved groups (Reich et al., 2011; Reich, 2014; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020; Norberto Rocha, 2021). In Latin America, the Guia de Museus e Centros de Ciências Acessíveis da América Latina e do Caribe (Guide to Accessible Science Museums and Centers in Latin America and the Caribbean) identified at least 110 institutions that have adopted accessibility practices (Norberto Rocha et al., 2017). However, further analysis revealed that these efforts often focus primarily on physical access, with limited attention to attitudinal and communicational strategies, which are essential for promoting meaningful participation and learning (Norberto Rocha et al., 2020; Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022; Norberto Rocha et al., 2025).

For people with visual or hearing disabilities, these limitations are particularly pronounced (Sukhai and Mohler, 2017). Inaccessible websites, lack of tactile or auditory resources, absence of sign language interpretation, and insufficient staff training, for example, can prevent spontaneous visits to museums and hinder independent navigation through their spaces (Fernandes, 2020; Carmo, 2021; Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022; Heck, 2024; Norberto Rocha et al., 2025). These gaps not only affect the immediate visitor experience but also contribute to the long-term exclusion of people with disabilities from scientific debate and career pathways. To address these challenges, museums should learn from the perspectives of visitors with disabilities, placing their experiences at the center of institutional transformation (Levent et al., 2013; Levent and Reich, 2013; Vicente and Norberto Rocha, in press).

In this context, the concept of Science Capital (Archer et al., 2015)—a theoretical framework that links individual engagement with science to cultural, social, and material resources—offers a valuable lens through which to examine these dynamics. Previous studies (Science Museum Group, 2023; ASPIRES, 2023; Heck, 2024; Heck and Ferraro, 2025; Heck and Norberto Rocha, 2025) suggest that accessible environments may enhance Science Capital among historically marginalized groups by enabling deeper interaction with scientific content and fostering positive attitudes toward science. However, few investigations have explored accessibility and the Science Capital model focused on people with disabilities, as shown in a literature review by Heck (2024).

Aiming to address this gap and bring a more inclusive perspective to this model, in the present research, we explore how Science Capital and accessibility are intertwined, based on empirical data collected during a visit to a Brazilian science museum.

2 Science capital through the lens of accessibility

Initially introduced by Archer et al. (2012), the term “Science Capital” was used without a formal definition, simply suggesting that its presence or absence could shape young people's aspirations in science. Only in later texts (Archer et al., 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020) was the idea published as a conceptual tool to explore how different forms of cultural, social, and symbolic capital interact to influence engagement and participation in science.

Archer et al. (2015), drawing on Bourdieu's theory of capital (Bourdieu, 1986), argue that unequal access to science-related capital helps explain the persistent disparities in who aspires to and succeeds in STEM fields. Science Capital is not a distinct form of capital in itself but rather an analytical tool that bundles various science-related resources, values, behaviors, and dispositions that have the potential to support individuals in seeing science as “for them” and participating in scientific pathways (Archer et al., 2015). The model combines three main domains: scientific cultural capital (knowledge, values, and science literacy), scientific social capital (networks and relationships that support science engagement), and science-related behaviors and practices (e.g., consuming science media, visiting science spaces).

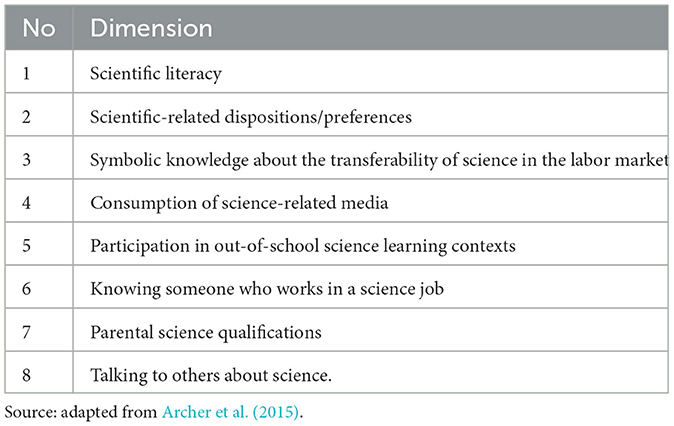

Afterwards, DeWitt et al. (2016) operationalized the concept into eight interrelated dimensions of Science Capital: (1) Scientific literacy; (2) Scientific-related dimensions/preferences; (3) Knowledge about the transferability of science qualifications; (4) Consumption of science-related media; (5) Participation in out-of-school science learning activities; (6) Family science skills, knowledge, and qualifications; (7) Knowing people in science-related jobs and (8) Talking about science in everyday life (Table 1). These dimensions are organized factors that explain why some individuals develop aspirations in science while others do not, even when interest or ability may be present. Instead of being solely cognitive or knowledge-based, they are shaped by structural inequalities, social norms, and personal experiences.

These works, however, are deeply rooted in the British educational and cultural context, drawing on large-scale studies conducted in UK schools. The dimensions formulation, then, reflects the structure of British schooling, social dynamics, and the cultural context of science communication. As such, applying the Science Capital framework outside Europe requires not only theoretical adaptation but also recognition of the sociocultural realities of the Global South. In Brazil, for example, disparities in access to education, cultural institutions, and science-related opportunities are compounded by structural inequalities (De Oliveira and Bizerra, 2023; Polino et al., 2024). Factors such as regional gaps, underfunded public schools, and lack of family acquaintance with scientific careers, as noted by Massarani et al. (2021a) in a study on Brazilian youths' perceptions of Science and Technology, can serve as social markers that may negatively impact the development of Science Capital.

Besides country or regional contexts, people with disabilities face increased challenges when engaging with science and science museums due to additional barriers (see Burgstahler, 2009; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020), creating a layered exclusion not fully captured by the original Science Capital model. Consequently, when observed through the lens of accessibility, people with disabilities face compounded barriers across all eight dimensions of the Science Capital, as explored by Heck (2024). By situating this study in the Global South, specifically in Brazil, we aim to contribute a non-British/Eurocentric perspective that highlights how cultural realities, local inequities, and accessibility gaps shape the ways people with disabilities engage with science in museums.

In this scenario, it also needed to incorporate the concept of “barriers”. As Sassaki (2020) states, barriers to people with disabilities can be attitudinal, communicational, methodological, instrumental, and programmatic. Attitudinal barriers, such as prejudice, low expectations, and ableism, can restrict opportunities for people with disabilities to develop science-related identities (Saudan et al., 2021; Meeks et al., 2025). The communicational ones can affect how individuals engage with scientific content, particularly when sign language, braille, audio description, or simplified language are not available (Carmo, 2021; Varano and Zanella, 2023; Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022; Silva, 2022; Ferreira et al., 2023; Norberto Rocha et al., 2023, 2025). Methodological and instrumental barriers, such as the lack of equipment and assistive technology (Norberto Rocha et al., 2025) or trained staff (De Leal and Norberto Rocha, 2024; Passos et al., 2024; Massarani et al., 2021b), also limit the quality of learning opportunities. Additionally, programmatic barriers, such as the absence of inclusive policies, undermine institutional responsibility in supporting equitable access to science (Reich, 2014; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020; Heck, 2024). Although recognizing the root of a barrier is important, in this study, as in Fernandes and Norberto Rocha (2022), we consider that a “barrier” can result from a lack of accessibility across multiple spheres or indicators with varied attributes.

Therefore, applying the Science Capital framework to audiences with disabilities requires not only acknowledging its eight dimensions but also critically examining the structural and material conditions that influence access to each of them. It also involves identifying how barriers intersect with forms of exclusion already addressed by the model (such as social class, gender, and race) how inclusion strategies must extend beyond physical access to embrace attitudinal and communicational dimensions.

3 Accessibility indicators and their correlation with science capital in museums

Inacio (2017) proposed a conceptual and methodological framework designed to analyze the accessibility potential of science and cultural places. Known as “Indicators of Accessibility in Science Museums and Centers,” the framework was further refined by Norberto Rocha et al. (2020) under the scope of the research group Accessible Science Museums and Centers. Since then, it has been adopted in various Brazilian studies and national and international institutions (Fernandes, 2020; Carmo, 2021; Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022; Silva, 2022; Marinho, 2023; Vicente and Norberto Rocha, 2024; Heck, 2021, 2024; De Oliveira, 2025).

The framework is grounded in an international literature review and Brazilian accessibility standards, such as NBR 9050 (Brasil, 2015). It can be used in national and international contexts to identify trends and disparities in accessibility across global museum practices. It enables an integrated assessment of a museum's accessibility based on three core indicators: (1) physical accessibility, (2) attitudinal accessibility, and (3) communicational accessibility (Table 2). Each indicator is composed of specific attributes and evaluative items that allow researchers to observe, measure, and interpret how inclusive and responsive a given space is to the needs of people with disabilities.

The Physical Accessibility' indicator assesses architectural aspects of the museum environment and the design of exhibits, ensuring barrier-free navigation and respectful engagement with diverse physical abilities. It includes access to buildings, ramps, signage, and exhibit features like tactile models. Attitudinal Accessibility indicator refers to inclusive practices and institutional commitments that aim to overcome stereotypes, biases, and stigmas related to disability. It encompasses staff training, inclusive programs, and the presence of formal policies supporting diversity. Lastly, Communicational Accessibility indicator involves resources that facilitate effective communication and information-sharing, such as accessible websites, printed materials in Braille or large print, videos with sign language or audio description, and staff equipped to mediate interactions in diverse formats. Together, these indicators form a comprehensive lens through which accessibility in science museums can be evaluated and enhanced (Norberto Rocha et al., 2020).

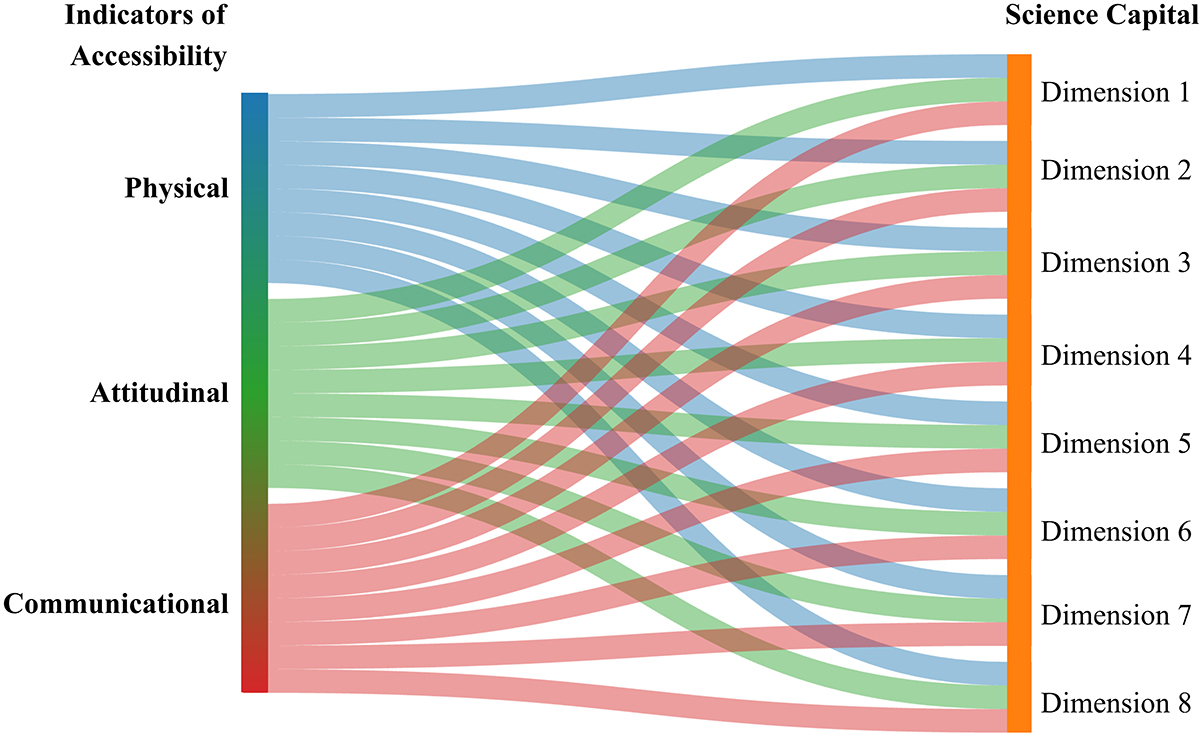

While these indicators serve as practical tools for diagnosing accessibility, we consider that they can also offer valuable insights into how different forms of exclusion impact the development of Science Capital among visitors with disabilities. Our hypothesis is that indicators of accessibility can intersect with the Dimensions of Science Capital and the visitors' experience can provide necessary evidence for that (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Potential connection between Accessibility Indicators and Science Capital Dimensions. Source: Authors (2025).

To support this hypothesis, the results section of this paper provides empirical examples that demonstrate correlations between accessibility indicators and specific dimensions of Science Capital, as reflected in participants' experiences during their museum visit and their own thoughts about their relationship to science throughout life.

4 Materials and methods

This exploratory and qualitative research was designed as a case study (Yin, 2018). Grounded in prior studies exploring Science Capital (DeWitt et al., 2016) and the Indicators of Accessibility in Science Museums and Centers (Inacio, 2017; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020), this study, carried out in two stages, focused on the experiences of Deaf visitors, users of Brazilian Sign Language (Libras), and blind visitors at a museum of science and technology in southern Brazil.

4.1 Participants with disabilities

Recruitment was carried out through snowball sampling (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981; Bernard, 2005), a method that involves starting with a key individual who meets the study criteria and can refer others in their network who also qualify (Henn et al., 2013). Snowball sampling has been particularly helpful in studies involving museum visitors, where accessibility factors might limit representation from the general population (Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022). To ensure inclusive outreach, invitation materials were provided in both Portuguese and Libras.

Adults with visual and hearing disabilities were invited to participate in a guided visit to an exhibition in a science museum. Two groups were chosen because access to scientific content often depends on sensory modalities, namely visual and auditory, especially in museums, where most exhibits rely heavily on visual communication.

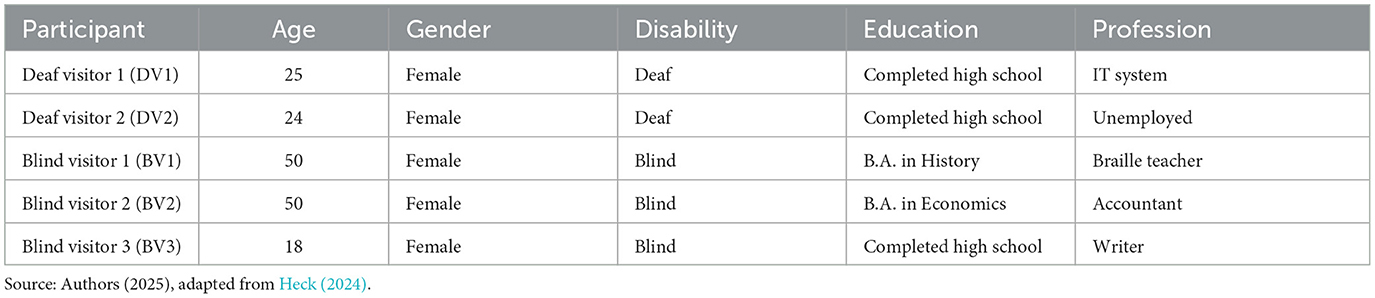

The eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, with no upper age limit, due to the challenge of recruiting volunteer participants with disabilities. In total, five self-identified women, with diverse educational backgrounds and professional experiences, participated in the study (Table 3). Although all participants were of the same gender, no criteria related to gender were established for this research. The predominance of women is only one characteristic of people who volunteer for research.

One group of visitors consisted of three individuals identified as blind participants (BV1, BV2, BV3). All three were congenitally blind women with strong social and educational backgrounds. One of the participants worked professionally as a Braille teacher, another was employed as a systems programmer and writer, and the third held a degree in Economics. Two had completed secondary and higher education, demonstrating familiarity with discussions about accessibility and museum environments. All participants in this group relied on tactile and auditory resources to navigate their surroundings and engage with the content.

The other group consisted of two women identified as deaf participants (DV1, DV2). Although both had finished secondary school, their exposure to science museums was limited. They had little prior experience visiting such places and expressed doubts about how accessible they are. Both participants were deaf from birth and mainly used Libras for communication, along with written Portuguese as a second language. They reported facing frequent barriers when accessing cultural and scientific environments.

Considering the small sample size, the specific sociodemographic makeup of the participants, and the limited diversity typical of snowball sampling, these findings should not be considered statistically representative of all people with disabilities.

4.2 The climate change exhibition: content and accessibility resources

The guided visit stage of this research took place at an exhibition called “Climate Change.” This exhibition was selected among many offered by the museum due to its contemporary and relevant theme, as well as the provision of accessibility resources. The museum chosen is one of the leading interactive science museums in Latin America, hosting thousands of visitors each year, including school groups, families, and tourists. Although the museum has implemented some inclusion-oriented initiatives, the consistent presence of people with disabilities remains limited.

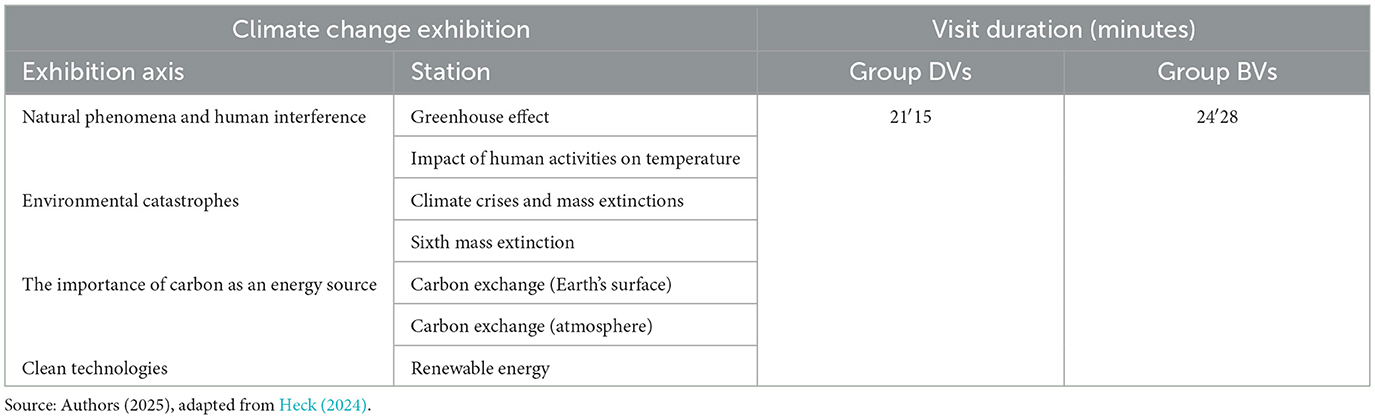

The Climate Change exhibition was launched in April 2022, addressing the causes, consequences, and strategies to mitigate climate change. It combines scientific evidence with an immersive visitor experience and is organized into five conceptual axes: (A) natural and human-induced climate change; (B) environmental catastrophes and mass extinction; (C) the role of carbon in the energy matrix; (D) the contribution of clean technologies; and (E) future choices and collective responsibility. The exhibition features 13 interactive stations distributed across two floors, utilizing videos, panels, models, games, and multimedia displays to engage visitors through sight, touch, and sound. Highlights include a sensory greenhouse chamber and a full-scale replica of a Carnotaurus, used to demonstrate the connection between climate events and species extinction. A custom itinerary (Supplementary Material 1) was created for this research, encompassing all five conceptual axes.

The exhibition's accessibility relies on a mobile application designed with inclusive navigation to promote access for people with visual and hearing disabilities. The app, which needs to be downloaded onto the visitor's mobile phone, offers a simplified visual interface with high-contrast icons and touch-based navigation. Created to allow blind visitors to explore the interactive stations independently and deaf visitors to access content in their first language, it features two distinct modes: (1) a voice-controlled audio interface that guides visitors step-by-step through the exhibition, providing environmental navigation tips (such as locations of restrooms and stairs) and audio descriptions of the exhibit's interactive stations; and (2) a Libras mode, enabling users to access videos in sign language with detailed explanations of each concept, even when the physical display lacks written information. The app connects via Bluetooth to beacons placed near each interactive station and works offline. Except for two interactive games, all stations are supported by the app. The content is also available in English through on-screen language options, QR codes, or subtitles.

4.3 Data production

The study was conducted in two stages: (1) Guided Visit and (2) Science Capital Assessment. Before working with participants, the museum exhibition was evaluated using the Accessibility Indicators (Norberto Rocha et al., 2020). This involved observing the exhibition areas and recording the available accessibility features through field notes, photos, and videos. The interactions between visitors and exhibits, along with the accessibility tools, were monitored to assess their practical usability and how engaged visitors were with the materials.

In the first stage, Guided Visit to the Climate Change exhibition were conducted with two separate groups of adults: one comprising blind visitors (Group BV) and the other of Deaf visitors (Group DV). The groups visited the exhibition on different days (see Table 4), following the predefined itinerary and spending between 20 and 25 min. The entire visit, including interactions with exhibits and accessibility resources, was observed and recorded in both video and audio formats with the consent of all participants. The visit of the Deaf participants took place in November 2023 and was supported by a certified Brazilian Sign Language interpreter. The visit of the blind participants occurred in January 2024, with each participant accompanied by a sighted guide for logistical support and safety.

In the second stage, data were collected through both pre- and post-visit interviews, each lasting approximately 30 min, as well as the administration of a Science Capital Index questionnaire (Moote et al., 2020). The pre-visit interviews focused on their experiences and expectations regarding museum accessibility and their understanding of climate change concepts, with questions such as “What do you expect in terms of accessibility when you visit a museum?” and “What do you understand by climate change?”

The post-visit interview focused on participants' overall impressions of the exhibition, clarity of the content, the role and effectiveness of accessibility resources, and whether the experience would have been different without them. They were also asked to comment on whether they felt welcomed and included and provided suggestions for making the museum more accessible. Also, the participants were asked about their perceptions of the importance of science, their interest in becoming scientists, and whether the experience increased their engagement with science. These included: “If you had visited this museum as a child, do you think you would have liked science more? Or been more interested in becoming a scientist?”, “Do you think people with disabilities can work with science or as scientists?” and “Do you think people like you can work in science or become scientists?”. Lastly, a question explored the impact of accessible science communication: “If scientific news and information were presented the way they are in this museum, would you be more interested?”

The Science Capital Index questionnaire (Supplementary Material 2), administered both prior to and after the visit, is an instrument widely used in studies based on the Science Capital model. It includes standardized questions. While this instrument has been widely used in international studies to assess participants' attitudes, aspirations, and engagement with science, it does not include items specifically addressing issues of access or representation in science. As such, the tool may not fully capture the attitudinal and communicational barriers faced by participants with disabilities in their relationship with science. Since this questionnaire was initially developed within a British educational context, adaptations were made for the Brazilian reality, including terminological adjustments and the addition of items addressing access and representation issues, such as “Do you have access to science in your primary language?”, “Is scientific content available to you through assistive technologies or accessible formats?”, or “Do you perceive science as accessible?”. These extra questions were excluded from the Index calculation, as including them would have required revalidating the instrument, which is beyond the scope of this study.

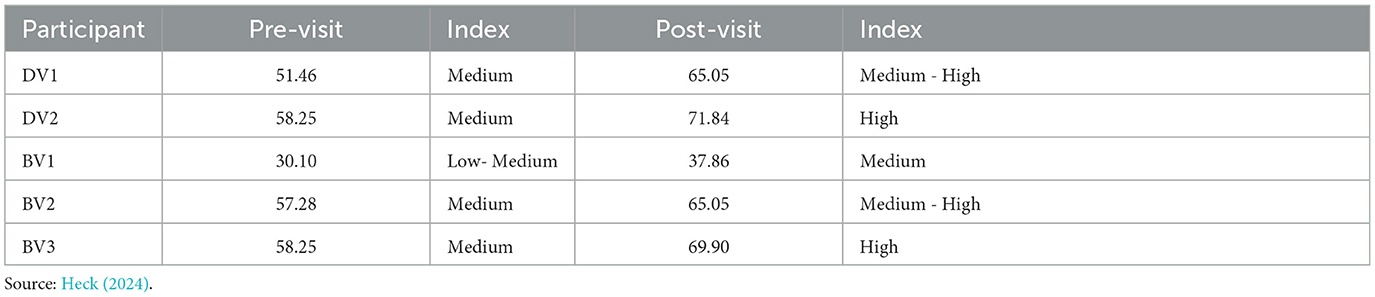

In this questionnaire, participants completed Likert-scale questions from DeWitt et al. (2016) and Moote et al. (2020), using a five-point agreement scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), with assigned weights ranging from −2 to +2. Raw scores were calculated by averaging the values for each participant, producing an index ranging from −21 to 30.5 (Moote et al., 2020). For interpretability, scores are converted to a 0–100 scale, classifying as: High (70–100), Medium (35–69), Low (0–34) (Archer et al., 2015; Moote et al., 2020). For this research, intermediate brackets (e.g., medium-high and low-medium) were defined to refine the analysis.

As discussed by Archer et al. (2015) and Moote et al. (2020), the score does not directly reflect accumulated scientific knowledge but rather represents a set of interconnected factors that indicate how science is integrated into individuals' lives. Individuals with high Science Capital are more likely to engage in science-related conversations, know people working in science, take part in out-of-school science activities, and see science as relevant and accessible. In contrast, those with low Science Capital often lack exposure to science experiences, feel detached from scientific careers, and may not view science as something for “people like them” (Moote et al., 2020). This distinction highlights that Science Capital is shaped by social, cultural, and structural factors that affect a person's opportunities to engage with science.

In this research, we consider that changes in the indices may reflect shifts in perception, trust, or interest in science, especially among historically underrepresented groups, such as people with disabilities. However, we will not use them as measures of Science Capital, but rather as a tool to gain a more robust understanding of how research participants perceived their museum experience and how this influenced their relationship with science.

4.4 Data analysis: exploring the data through the double lenses of science capital and indicators of accessibility

The data produced in both stages were triangulated, enabling cross-validation of the data from different sources and helping to capture complementary perspectives on participants' experiences. The corpus comprised 133 min of interview transcripts, ten questionnaires, and 225 min of video recordings of the visits, as well as field notes from the observations. All research activities prioritized communication and subjectivity as central tools for knowledge production (Flick, 2009), emphasizing the lived experiences of participants and situating them within broader social and cultural contexts.

A thematic analysis (cf. Braun and Clarke, 2006) was utilized to interpret the qualitative data, whereby the collected information was systematically organized and coded thematically to categorize similar ideas and expressions under broader conceptual groups. Considering the qualitative and exploratory nature of this study, quantifying data does not imply converting it into a numerical metric for quantitative analysis. Rather, the purpose of assigning numerical values to qualitative data is to facilitate the identification of patterns that enhance our understanding of the participants' lived experiences (Minayo, 2012), thereby contributing to an overall comprehension of the research subject (Creswell, 2014).

The results are presented and discussed in the following section. First, the categories that emerged from the thematic analysis are described and analyzed; second, the Science Capital Index results are provided, along with an examination of the changes exhibited by the participants.

5 Results

Examining the data through the double lenses of Science Capital and Indicators of Accessibility, using thematic analysis, resulted in 497 codes. These codes were identified and organized into 25 initial categories, 10 intermediate categories, and three final thematic groups: mechanisms of in/exclusion in museums and science; scientific content in context; and attitudes, values, and science-related dispositions (Supplementary Material 3). Each of these final categories provides evidence, in the context of a science museum visit, of how dimensions of Science Capital and Indicators of Accessibility are intertwined.

5.1 Mechanisms of in/exclusion in museums and science

The highest number of codes (n = 288) was labeled as “Mechanisms of In/Exclusion in Museums and Science” because it includes data showing visitors' experiences with accessibility and inaccessibility across three indicators: physical, attitudinal, and communicational (Norberto Rocha et al., 2020). This category reflected participants' thoughts on how their experience influenced their sense of inclusion, autonomy, and connection with science.

For participants with visual disabilities (BV1, BV2, and BV3), access to sensory-based content during the Climate Change exhibition visit was central. As BV3 stated, “The sensory aspect, the chance to touch things, is really important to understand better” (indicators 1 and 3). It directly relates to the Scientific Literacy dimension (dimension 1), as tactile experiences are a crucial way of learning that allows them to actively construct meaning from scientific content (Sukhai and Mohler, 2017). At the same time, it emphasizes the importance of inclusive out-of-school Science Participation opportunities (dimension 5), which are part of the experiential dimensions of Science Capital, since these spaces support multi-sensory, accessible experiences (Morais, 2019).

The attitudes of museum professionals and visitors were also considered important (indicator 2). BV2 highlighted: “The most important thing is goodwill. If they want to make it work, it will.” Conversely, BV1 cautioned: “But if there's no goodwill… it's pointless.” These statements underscore the role of science-related attitudes and dispositions (dimension 2), especially as they are influenced by institutional culture and staff engagement.

These science-related attitudes and dispositions are influenced not only by personal interest or early exposure to science but also by interpersonal interactions within scientific contexts (dimensions 7 and 8) (DeWitt et al., 2016). In science museums, such attitudes can either foster a sense of inclusion and belonging or reinforce exclusion and disidentification.

For the Deaf participants (DV1 and DV2), linguistic access was a prerequisite for engagement (indicators 3 and 2). As DV2 stated: “If there is a Libras interpreter, then I go.” This aligns with the need for communicational and attitudinal accessibilities to ensure full inclusion and relates to multiple Science Capital dimensions: Talking about Science in Everyday Life (dimension 8), Out-of-School Participation (dimension 5), and Attitudes and Dispositions (dimension 2). This seemingly simple statement encapsulates a profound reality faced by many Deaf individuals: participation is not a matter of choice, but of accessibility (Burgstahler, 2017). Without access to communication in their primary language, opportunities to engage with science are systematically restricted, and several dimensions of Science Capital become severely constrained.

Participants' statements illustrate how the eight dimensions of Science Capital, especially those related to social connections and science interaction, can be either limited or expanded depending on the level of the three indicators of accessibility. The presence of accessible resources, inclusive attitudes, and opportunities for meaningful interaction not only facilitates learning but also supports identity formation and engagement with science.

Participants noted that accessibility in museums is often sporadic rather than a consistent institutional policy (indicator 2), stating that “There was an ad on Instagram about an exhibition, downtown, […] but I didn't feel like going that day because it was really just… looking at the information there. If there had been an interpreter, then I might have gone” (dimension 5). This highlights the lack of a strong institutional culture that truly integrates inclusion as a core value, which underscores the critical role of institutional commitment and long-term planning in fostering inclusion beyond isolated or performative actions. According to Norberto Rocha et al. (2020), attitudinal accessibility requires the presence of formal policies, strategic planning, ongoing staff training, and budget allocation for accessibility, all of which must be embedded in the institution's mission and day-to-day practices. When these elements are absent, the visitor experience becomes conditional rather than guaranteed, particularly for people with disabilities.

Overall, this category provides insights on how accessibility, or its absence, can influences how visitors with disabilities construct, limit, or expand their Science Capital in non-formal learning environments, through dimensions 2 (Attitudes and Dispositions), 4 (Science Media Consumption), 5 (Out-of-School Participation), 7 (Knowing People in Science), and 8 (Talking About Science in Daily Life). The data reinforce that Science Capital is not an abstract construct; it is actively shaped, constrained, and enabled by lived experiences with science, as well as by accessibility.

5.2 Scientific content in context

The second most frequent category identified (n = 158) was labeled “Scientific Content in Context” because it explored participants' understanding and use of scientific concepts related to climate change. It highlighted how scientific knowledge is interpreted, questioned, and applied in their daily lives, both before and after the guided visit, and linked to accessibility factors. This corresponds with the Scientific Literacy dimension (dimension 1) of Science Capital, which includes scientific knowledge, skills, and an understanding of how science “works,” as well as the ability to use and apply these competencies in everyday situations for personal and social benefit (Archer et al., 2015). The museum experience prompted changes in participants' understanding of scientific content, revealing the centrality of accessibility in supporting knowledge development.

DV1 initially believed that CO2 was inherently toxic and denied emitting it herself. After engaging with interactive exhibits and watching explanatory videos in Libras (indicators 1 and 3), she revised her understanding (dimension 1): “Yes, in our breath we emit [CO2],” she acknowledged, distinguishing between natural emissions and industrial sources. Similarly, DV2 clarified: “What contributes [to global warming] is when this gas, CO2, is extracted from underground and released into the atmosphere, which happens when we use fossil fuels.”

There was also evidence of a shifting understanding regarding human contributions to climate change. Before the visit, DV1 hesitated to assign blame to human actions, stating: “I don't think people are to blame… we're just consumers.” However, after engaging with the exhibit, she revised her view: “I feel that the influence is ours, right? I feel the extinction of animals and the influence on the planet is caused by humans.” This shift demonstrates how the exhibit content, supported by accessible mediation, catalyzed critical thinking about collective responsibility.

Participants also articulated connections between scientific content and their lived experiences (dimension 1 and 5) through the physical and communication interaction with the exhibits (indicators 1 and 3). One of the exhibition topics addressed the greenhouse effect and highlighted some of the potential ecological imbalances affecting humanity. The description says:

“Many species will become extinct, while others will be displaced from their natural habitats into new regions. There is evidence, for example, that climate change has contributed to an increase in certain bat populations in regions where the new coronavirus originated. It is known that bats are the primary source of this virus.”

This excerpt prompted participants to reflect on local news and personal experiences involving the unusual presence of bats in the historic center of their city, raising concerns about the coronavirus. BV2 stated:

“I don't know if you've seen it, but not long ago, there was a situation with a lot of bats showing up downtown. And during the storm on January 16th [2016], the roof of my building was completely torn off. I believe there was a bat nest there because they seem to be spreading downtown and in the neighborhoods, right? I remembered.”

BV1 asked, “Does the increase in bats increase the transmission of coronavirus?” Although the mere presence of bats near urban areas does not directly correlate with the spread of COVID-19, the participants expressed concern due to a lack of accessible and reliable information. This highlights how limited access to scientific content—particularly in formats that are inclusive of people with disabilities—can leave gaps in understanding, potentially fueling misinformation or unwarranted fears.

When discussing the extinction of dinosaurs, participants encountered a vivid narrative supported by audio description (indicator 3), portraying a meteorite strike that caused a massive dust cloud to envelop the Earth, ultimately blocking sunlight, halting vegetation growth, and leading to species extinction. It stated,

“On the riverbank, dinosaurs walk peacefully […] while a flaming meteor crosses the sky. […] and the explosion fills the screen. […] From space, a dust cloud begins to envelop the planet. […] As it falls, amid smoke and dust, a Carnotaurus and a Brontosaurus suffocate and die. […] From space, the planet gradually becomes entirely covered in dust. […] Time passes, and the continents shift shape until reaching their current form. On Earth, a natural landscape and blue sky give way to a city with factories and heavy pollution. In front of the city, a yellow lizard walks with a sad expression as the smoke intensifies. Smoke fills the entire screen”.

After this description, BV3 connected this depiction to scientific theory, stating: “It was dust that blocked sunlight from entering the Earth. Vegetation didn't grow. Then the animals died… not directly by the meteor” (dimension 1).

Her reaction also revealed an emotional connection to the exhibit: “Poor sad lizard,” referring to the animated representation described. Such comments reflect how sensory and emotional engagement (dimension 2), enabled by access tools, supports the idea that accessible science communication is not only cognitive but also experiential and emotional, allowing visitors to build meaning through emotional resonance and connect it to broader concerns about environmental change and human responsibility.

In this category, we conclude that the accessible design, mainly through physical and communicational accessibilities of the exhibition, empowered participants not only to engage and build scientific knowledge but also to recognize their roles as informed citizens. This can contribute to the development of several dimensions of the Science Capital – Scientific Literacy (1), Attitudes and Dispositions (2), Science Media Consumption (4), Participation in Out-of-School Learning (5) and Talking About Science in Daily Life (8).

5.3 Attitudes, values, and science-related dispositions

Lastly, we could group 51 codes under the label “Attitudes, Values, and Science-Related Dispositions” since they reveal how participants' perceptions, aspirations, and values influenced their relationship with science. Most responses were related to Scientific Career Pathways (dimensions 6, 7, and 8) and Scientific Identity (dimension 2). Both are directly connected to key dimensions of Science Capital: attitudes and dispositions, knowing people in science-related jobs, aspirations, and perceived relevance of science in everyday life (Archer et al., 2015; DeWitt et al., 2016).

Throughout the activity, participants expressed both interest in science and frustration with the barriers preventing full participation. DV1 clearly articulated this tension: “If there were accessibility, then I would think about becoming a scientist.” Similarly, BV3 shared: “I really like science, but because of these barriers, I wouldn't pursue it… Honestly, yes, I'd like to be a scientist, but it's not accessible. That's the complicated part, I like science.”

These quotes reflect how a lack of accessibility, in its general form (indicators 1, 2 and 3) undermines scientific aspirations, particularly when disability is wrongly perceived as incompatible with scientific practice. DV1 remarks: “Science is zero accessible for Deaf people”, which illustrates how systemic exclusion can influence both career interest and the development of a scientific identity (dimension 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8).

Regarding the Science Capital Index, BV1 noted during the interview: “I answered many questions favoring science, but for the ones about encouragement at school… I marked them all as ‘bad' because there was none.” (indicators 1, 2 and 3). BV2 complemented: “[Encouragement] doesn't exist, especially if the person is blind. Unless you really love science. If you only like it a little, they'll discourage you.” (indicator 2). These statements point to barriers in schools and confirm ableist practices in formal education that perpetuate the exclusion of students with disabilities and diminish any chance of developing interest in science and science careers (dimension 2 and 3).

In terms of Science Capital, this lack of encouragement and representation reflects deep-rooted inequalities: fewer accessible opportunities and resources restrict the development of positive attitudes and aspirations (dimension 2). As Shingledecker et al. (2014) explain, without role models, meaningful science experiences, or family/school support, students with disabilities may internalize limiting beliefs about their own potential in science.

The lack of adequate opportunities remains a pressing issue. DV1 shared that she declined a university program due to the absence of a qualified sign language interpreter (indicators 2 and 3): “I really wanted to study at this university, but there was no interpreter in my field.” She concluded: “If the path were open, with accessibility already in place, then yes, I could work in science. Without it, it's impossible” (dimension 1, 2 and 8).

BV3 raised a broader concern about the devaluation of science in Brazil: “Science… in Brazil? There's no support, right? Scientists don't get recognition. I'd only pursue it if I already had my life sorted out and wanted to do something extra.” This sentiment underscores how structural disincentives, such as lack of funding, professional instability, and public undervaluing of science, intersect with accessibility issues, creating a more complex and exclusionary scenario for aspiring scientists with disabilities (Burgstahler, 2009).

This category also included reflections on scientific identity. For some participants, early experiences of exclusion led to disengagement. DV1 repeatedly expressed disinterest in science, saying: “It doesn't fit my profile… I NEVER wanted to be a scientist.” However, when asked why, she explained: “There's a reason… my interest [during school] wasn't there because there was no accessibility, no interpreter. We just followed the classes without understanding.”

The analysis highlights the cyclical and multi-layered nature of exclusion: a lack of accessibility leads to disengagement, which reinforces marginalization and underrepresentation in science. However, participants revealed curiosity and interest during the museum visit, showing that accessible and engaging science communication can spark latent scientific curiosity.

5.4 Science capital index

The results of the pre- and post-visit Science Capital Index questionnaires revealed changes in the scores of all participants (Table 5). DV1 and BV2 increased from medium to medium-high levels; DV2 and BV3 moved from medium to high levels; and BV1 improved from low-medium to medium levels, indicating that inclusive science experiences can potentially alter participants' perceptions of their relationship with science.

Although the Science Capital Index was not originally meant to be used before and after a single intervention, because its increase is usually seen as a reflection of cumulative changes and perceptions developed over a lifetime, the use of the index in this study shows its potential as a reflective tool, especially when adapted to inclusive settings. By allowing participants to revisit their perceptions after an accessible and dialogic science experience, the questionnaire itself became a tool for critical reflection.

The shifts on Science Capital Index can be expressed by the following elements:

5.4.1 Redefining scientists and science in everyday life

One of the most important changes was how participants understood what it means to be a scientist. At first, they linked scientists to the stereotypical image of a man in a lab coat working in a lab. After the visit and discussions, participants began to see that scientists work in many different fields, including at the museum. This change affected their answers to questions like “Do you know someone who works in science?” and “Do you think studying science can lead to various career opportunities?” The activity helped expand their view of science's applicability and relevance in different aspects of life.

5.4.2 Media engagement and science consumption

Participants also reported increased awareness of science in traditional media—such as books, films, and news. While they did not always actively seek out scientific information, they realized that science was present in many of the formats they consume. As stated by DV1, “such as the medicine, right? It's in everything, all of it is science,” and DV2 commented, “[in the museum] it's a different kind of content, right? It's designed for science communication, so it's not that raw, complex text”. However, DV1 reported that to access scientific content, “[…] nowadays the only accessibility would be subtitles, but Deaf people won't really understand. Many times they don't know many [Portuguese] words, there are some things we miss… For example, ‘carbon dioxide.' If it were just that word in the subtitle, it would be something lost [in the exhibition],” demonstrating that beyond an interest in the content, accessibility is essential for meaningful understanding and engagement.

This recognition led to a shift in how they answered the question “How often do you read science books or magazines outside school?”, aligning with the Science Media Consumption dimension of Science Capital, which is closely related to a person's ability to access and apply scientific knowledge in everyday contexts. However, the initial answer on this dimension may reflect not a lack of interest, but a lack of accessibility. Participants with disabilities often face limited access to scientific content in inclusive formats, such as sign language videos, audio description, or Braille materials (Burgstahler, 2009). When scientific information is not available in accessible formats, it reinforces inequality and leaves disabled individuals more vulnerable to misinformation and exclusion from critical knowledge networks.

5.4.3 Attitudinal barriers and institutional influences

Despite the positive changes, attitudinal barriers, particularly between family and school contexts, remained strong. Participants recalled receiving little to no encouragement from teachers or parents regarding science. BV3 stated that “back in school […] I had a teacher who skipped basic math steps, she was a very prejudiced math teacher. […] I liked computer science, right? but couldn't manage some parts that involved basic math because of that teacher”, and BV2 complemented, “That's exactly what we struggle with the most [prejudice], what really holds us back.”

Questions such as “Did your teachers encourage you to continue with science after high school?” or “Did your parents think science is useful for your future?” revealed long-standing gaps in support. These barriers align with what Archer et al. (2020) describe as inequalities in science-related aspirations caused by limited social capital and reinforcement in everyday life. Participants' formative experiences, often shaped by low expectations or a lack of understanding of disability, contributed to a weakened scientific identity. Notably, these factors remained largely unchanged after the activity, indicating the deep-rooted nature of attitudinal barriers and highlighting the need for systemic cultural shifts in education.

6 Discussion

Through empirical data gathered during a visit to a science museum exhibition in Brazil, we demonstrated strong correlations between Science Capital (DeWitt et al., 2016) and the Indicators of Accessibility in Science Museums and Centers (Inacio, 2017; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020).

The insights from blind and Deaf adults provided evidence to confirm our hypothesis that the indicators can intersect with the dimensions of Science Capital. Barriers in architecture, accommodations, and in the design and use of objects (indicator 1) may prevent participation in museum visits, directly limiting exposure to non-formal science education (dimension 5) and, consequently, to opportunities for science literacy (dimension 1), as well as the consumption of science-related media that depends on physical resources (dimension 4).

A lack of tactile exhibits and Braille materials, Sign language interpretation, and other communication resources (indicator 3) can hinder scientific literacy for blind and deaf visitors (dimension 1), the communication and understanding of science (dimension 3), talking with others about science (dimension 8), and, consequently, all the dimensions that rely on any form of communication. Similarly, attitudinal barriers (indicator 2), such as prejudice and ableism, can discourage people with disabilities from seeing science as relevant to them (dimension 2), ultimately weakening their identification with scientific discourse, but they can also prevent family encouragement (related to dimension 6) and decrease opportunities for science-related conversations in everyday life (dimension 8). Additionally, when people with disabilities are underrepresented in a science museum, its exhibitions, and science-related jobs, or when they have no chance to interact with disabled scientists, technicians, or educators, they miss important examples of future possibilities (dimension 7). This lack of representation can perpetuate stereotypes and limit aspirations. Furthermore, the lack of institutional policies promoting accessibility in museums undermines the opportunity to develop inclusive practices systematically (indicator 2). This affects not only isolated experiences but also the broader mission of museums as inclusive spaces for science communication.

Furthermore, accessible and inclusive practices at science museums can significantly boost the Science Capital of visitors with disabilities by engaging multiple dimensions, such as scientific literacy, attitudes, media involvement, aspirations, and identity. This issue is primarily highlighted in categories 1 (Mechanisms of In/Exclusion in Museums and Science) and 2 (Scientific Content in Context) of our analysis.

The guided visit at the science museum and the research procedures also showed that participants' past experiences with exclusion can greatly influence their interactions with science in everyday life (dimension 8). If people with disabilities are prevented from accessing information through their preferred communication methods (indicator 2) or face repeated exclusion (indicator 1), they are less likely to view science as a subject worth discussing or sharing with others. This can lessen their sense of belonging within the scientific community and reduce the likelihood of science being part of their social conversations.

The participant comments also revealed that barriers stemming from various levels of structural, communicational, and attitudinal inaccessibilities directly impact the perception, access, and engagement with science. As the data indicates, the barriers can limit not only immediate learning but also broader aspects of identity formation, aspirations, and long-term participation in science. This is especially clear in category 3 (Attitudes, Values, and Science-Related Dispositions), illustrating the complexity and interconnectedness of the layers of access and barriers in the life of a person with disability. The thickness of these multiple, intertwined layers can suggest how hard it is to break through the bubble and move past the layers of scientific engagement.

The results of the Science Capital Index Assessment—although it was not originally designed to be used immediately after a single museum visit, as in this study—indicate that some dimensions of Science Capital previously unnoticed by the participants were activated during the process. This data production method helped reinforce evidence and express the participants' lived experiences, particularly regarding their perceptions of scientists and science in daily life, media involvement and science consumption, and attitudinal barriers and institutional influences on their scientific identity.

Finally, we understand that the Indicators of Accessibility (Inacio, 2017; Norberto Rocha et al., 2020) worked not only as evaluative tools of the access of the science museum experience but also as a conceptual bridge linking institutional practices with the structural conditions necessary to expand the Science Capital model (DeWitt et al., 2016). This consideration is particularly pertinent when engaging with individuals with disabilities and/or those from outside the British/European context.

7 Limitations

The study was conducted in a controlled environment where the accessibility strategies were already known to the researchers. This may not reflect typical museum experiences, given their diversity in contexts, programming, and activities. Additionally, the data comes from a small number of participants, recruited through snowball sampling; therefore, the experiences and views of the adults in this study should not be considered fully representative of wider populations of people with disabilities. Caution and careful consideration are needed when applying these findings to other groups. The research focused on immediate effects without a longitudinal follow-up to evaluate long-term impacts on participants' educational or career paths.

The Science Capital index, while useful, also faces challenges in translating from English to Portuguese and Brazilian Sign Language, as well as in cultural adaptation. Originally developed focusing on populations in the UK without explicitly recognizing the diversity among disability groups, it does not fully address barriers faced by people with disabilities or consider alternative ways to engage them. Using adapted surveys in Libras and providing narration was a priority to ensure the participation of blind and deaf individuals in this research; however, this might affect the ability to compare the results with other studies.

8 Contributions and final remarks

As part of the Research Topic Inclusion in Non-formal Education Places for Children and Adults with Disabilities Vol. II, this study makes an original contribution by exploring how accessibility in science museums can promote the development of Science Capital among blind and Deaf visitors, and what this means for expanding the Science Capital framework in contexts marked by structural inequalities. Previous publications have advanced valuable discussions on accessibility and inclusion in museum settings for blind and Deaf audiences. For example, studies have examined the experiences of adults with visual disabilities in Brazilian museums (Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022), the impact of inclusive creative projects in Spanish museums (Rojas-Pernia et al., 2025), and in Egyptian museums (Zakaria, 2023), as well as strategies to improve online accessibility in science exhibitions (Norberto Rocha et al., 2025). Other research has focused on Deaf individuals' participation in science outreach, exploring video strategies for traveling science centers (Ferreira et al., 2023), and non-formal science activities for Deaf and hard-of-hearing children (García-Terceño et al., 2023).

While these papers share this study's concern for promoting inclusion and accessibility, they do not incorporate the ideas of Science Capital, nor do they assess how inclusive practices influence science aspirations, identities, or long-term engagement. Thus, this research contributes by integrating accessibility with the Science Capital model (Archer et al., 2015; DeWitt et al., 2016). Our proposal also advances beyond prior published studies that used the Science Capital model by addressing its limitations when applied to people with disabilities. The current findings suggest that accessible and inclusive science experiences can highlight overlooked aspects of Science Capital and advocate for expanding the model to include accessibility as a key analytical dimension explicitly.

We also emphasize that accessibility should no longer be seen as a secondary concern, but as a core part of equitable science engagement. While the Science Capital framework has been key in understanding how individuals connect with science through cultural, social, and symbolic resources, it still falls short in addressing the systemic and structural barriers that disproportionately affect people with disabilities. As this study demonstrates, even a single accessible science experience can activate multiple aspects of Science Capital, highlighting the transformative power of inclusion. However, sustainable change requires recognizing accessibility not as an optional add-on but as an essential element in theoretical models, institutional practices, and public policy.

Reshaping the Science Capital model to account for accessibility would not only enhance its analytical strength but also better align it with social justice principles and the right to science for everyone. From this perspective, science museums that prioritize accessibility can activate and strengthen multiple dimensions of Science Capital in their audiences (Heck, 2024). They can provide opportunities for participation in science communication, increase scientific literacy through multisensory experiences, and foster positive attitudes toward science by encouraging a sense of belonging (Sandell et al., 2010; Reich, 2014; DeWitt et al., 2019). Most importantly, by involving people with disabilities in designing and evaluating their programs, museums can challenge traditional assumptions in science education and promote a more diverse and equitable scientific culture. In this way, science communication and education initiatives can work toward creating a more inclusive and diverse scientific culture.

Our study demonstrates an effort to challenge the original British/Eurocentric design by proposing a more inclusive perspective that is sensitive to structural inequalities and contextual barriers, especially in the Global South. It suggests methodological adaptations, addresses structural barriers, and shows how inclusive design can encourage lifelong and life-wide learning. We hope this research will inspire future studies to continue expanding the Science Capital model.

By highlighting interdisciplinary collaboration and institutional responsibility, this research also contributes to the discussion on how museums and other non-formal education spaces can become more socially just, accessible, and empowering for diverse audiences. We, therefore, recommend that museums adhere to essential principles to enhance the accessibility of exhibition design.

• Multisensory resources: ensure that every exhibit includes tactile, visual, and auditory options (such as Braille, audio descriptions, sign language interpretation).

• Consistent institutional policies: incorporate accessibility into long-term plans, budgets, and staff training programs.

• Co-creation with communities: involve visitors with disabilities in the design and evaluation of exhibitions, recognizing their lived experiences as expertise.

• Inclusive and representative communication: guarantee that information – from websites to exhibit panels – is available in accessible formats and primary languages of the target audiences, and promote diversity within the museum's staff and exhibits for better representation.

• Attitudinal change: foster a culture of goodwill and awareness among staff, as interpersonal interactions are essential for creating a sense of inclusion and belonging.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Data generated in Portuguese. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to aGVjay5nc0BnbWFpbC5jb20=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio/FIOCRUZ/RJ (CAAE 47557021.0.0000.5241). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JN: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors are supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico -CNPq/Brazil), GH under Junior Postdoctoral Fellowship 179836/2024-2, JNR, AB and JLF under grant Research Productivity Fellow PQ 305408/2021-6, PQ 315606/2023-1 and PQ 316520/2021-7. GH was also supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior -CAPES/Brazil), Finance Code 001, processes 88887.605905/2021-00, 88887.683506/2022-00 and 88887.979300/2024-00.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brazilian Science Museum, its staff, and the research participants. We also thank the research group Accessible Science Museums and Centers (Grupo MCCAC) for their discussions and contributions to the work. This paper is based on findings from the doctoral thesis “(Defi)ciência & inclusão: possibilidades para construção do Capital da Ciência a partir de uma experiência museal acessível” (PhD thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, 2024). The authors acknowledge the support of the Graduate Program in Education at PUCRS and the CAPES-PrInt program for providing the international exchange scholarship, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for their support through the Research Productivity Fellowship. Special thanks are extended to Newcastle University, the Great North Museum, the University of Oxford, and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History for hosting and supporting the research exchange period.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1681129/full#supplementary-material

References

Archer, L., Dawson, E., DeWitt, J., Seakins, A., and Wong, B. (2015). Science capital: a conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending Bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 52, 922–948. doi: 10.1002/tea.21227

Archer, L., DeWitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., Wong, B., et al. (2012). Science aspirations, capital, and family habitus: how families shape children's engagement and identification with science. Am. Educ. Res. J. 49, 881–908. doi: 10.3102/0002831211433290

Archer, L., DeWitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., Wong, B., et al. (2013). ASPIRES Report: Young People's Science and Career Aspirations, Age 10–14 [Report]. UK: King's College London.

Archer, L., DeWitt, J., and Willis, B. (2014). Adolescent boys' science aspirations: masculinity, capital, and power. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 51, 1–30. doi: 10.1002/tea.21122

Archer, L., Moote, J., Francis, B., DeWitt, J., and Yeomans, L. (2020). ASPIRES 2: Young People's Science and Career Aspirations, Age 10–19. UK: UCL Institute of Education.

ASPIRES (2023). What Shapes People with Disabilities' Scientific Aspiration and Capital? London: UCL Blog.

Bernard, H. R. (2005). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th edn. Devon: AltaMira Press.

Bezzon, R. Z., and Bizerra, A. F. (2024). Educação não formal e espaços científico-culturais brasileiros: uma visão materialista histórico-dialética. Investigações em Ensino de Ciências, 29, 1–22. doi: 10.22600/1518-8795.ienci2024v29n1p01

Biernacki, P., and Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Soc. Methods Res. 10, 141–163. doi: 10.1177/004912418101000205

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J. G. Richardson (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

Brasil (2015). ABNT NBR 9050: Acessibilidade a edificações, mobiliário, espaços e equipamentos urbanos. Rio de Janeiro: Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brinkman, A. H., Rea-Sandin, G., Lund, E. M., Fitzpatrick, O. M., Gusman, M. S., Boness, C. L., et al. (2023). Shifting the discourse on disability: moving to an inclusive, intersectional focus. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 93, 50–62. doi: 10.1037/ort0000653

Burgstahler, S. (2009). Making Math, Science, and Technology Instruction Accessible to Students with Disabilities. Seattle: University of Washington.

Burgstahler, S. (2017). Equal Access: Science and Students with Sensory Impairments. Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology (DO-IT). Seattle, WA, United States: University of Washington.

Carmo, M. P. S. (2021). Experiências museais de sujeitos surdos em três museus de ciências do Rio de Janeiro (master's dissertation). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th edn. Newbury Park, Califórnia: SAGE Publications.

Daehn, I. S., and Croxson, P. L. (2021). Disability innovation strengthens STEM. Science 373, 1097–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.abk2631

Dawson, E. (2014). Equity in informal science education: developing an access and equity framework for science museums and science centres. Stud. Sci. Educ. 50, 209–247. doi: 10.1080/03057267.2014.957558

De Leal, A. O., and Norberto Rocha, J. (2024). As estratégias na divulgação da ciência para públicos diversos: um estudo sobre os mediadores de nove museus e centros de ciências do Rio de Janeiro. Amazônia: Revista de Educação em Ciências e Matemáticas 20, 87–104. doi: 10.18542/amazrecm.v20i44.15371

De Oliveira, B. H., and Bizerra, A. F. (2023). Social participation in science museums: a concept under construction. Sci. Educ. 108, 123–152. doi: 10.1002/sce.21829

De Oliveira, C. A. M. (2025). Análise dos desafios e potencialidades de acessibilidade para pessoas com deficiência em um centro de ciências itinerante: O caso do Ciências Sob Tendas (master's dissertation). Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Brazil.

DeWitt, J., Archer, L., and Mau, A. (2016). Dimensions of science capital: exploring its potential for understanding students' science participation. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 38, 2431–2449. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2016.1248520

DeWitt, J., Nomikou, E., and Godec, S. (2019). Recognising and valuing student engagement in science museums. Mus. Manage. Curatorship 34, 97–115. doi: 10.1080/09647775.2018.1514276

Falk, J. H., and Dierking, L. D. (2002). Lessons Without Limit: How Free-Choice Learning is Transforming Education. Devon: AltaMira Press.

Fernandes, M. P. (2020). A experiência de pessoas com deficiência visual: A acessibilidade e a inclusão no Museu da Geodiversidade da UFRJ e na Casa da Descoberta da UFF (master's dissertation). Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro.

Fernandes, M. P., and Norberto Rocha, J. (2022). The experience of adults with visual disabilities in two Brazilian science museums: an exploratory and qualitative study. Front. Educ. 7:1040944. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1040944

Ferreira, A. T. S., Alves, G. H. V. S., Vasconcelos, I. A. H., Souza, T. V. A., and Fragel-Madeira, L. (2023). Analysis of an accessibility strategy for deaf people: videos on a traveling science center. Front. Educ. 8:1084635. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1084635

García-Terceño, E. M., Greca, I. M., Santa Olalla-Mariscal, G., and Diez-Ojeda, M. (2023). The participation of deaf and hard of hearing children in non-formal science activities. Front. Educ. 8:1084373. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1084373

Heck, G. S. (2021). Popularização da ciência e inclusão de surdos: um estudo sobre espaços museais acessíveis (master's dissertation). PUCRS Repositório Institucional, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Heck, G. S. (2024). (Defi)ciência and inclusão: possibilidades para construção do Capital da Ciência a partir de uma experiência museal acessível (PhD thesis). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul]. PUCRS Repositório Institucional, Brazil.

Heck, G. S., and Ferraro, J. L. (2025). Accessible practices in science museums and their impact on the science capital of visually and hearing-impaired people. Rev. Int. de Pesquisa em Didática das Ciências e Matemática (RevIn) 6, e025011, 1–20.

Heck, G. S., and Norberto Rocha, J. (2025). A dimensão educativa dos museus e o Capital da Ciência: reflexões sobre inclusão e acessibilidade no campo científico. Museologia and Interdisciplinaridade. Brasília.

Henn, M., Weinstein, M., and Foard, N. (2013). A Critical Introduction to Social Research, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (1994). “Education, communication and interpretation: towards a critical pedagogy in museums,” in The Educational Role of the Museum, ed. E. Hooper-Greenhill (London: Routledge), 133–146.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2006). “The power of the museum pedagogy,” in Museum Philosophy for the Twenty-First Century, ed. H. H. Genoways (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press), 235–245. doi: 10.5771/9780759114258-235

Inacio, L. G. B. (2017). Indicadores do potencial de acessibilidade em museus e centros de ciência: análise da caravana da ciência (bachelor's thesis). Instituto Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

Levent, N., Kleege, G., and Pursley, M. J. (2013). Guest editors' introduction: museum experience and blindness. Disability Stud. Q. 33, 1–2. doi: 10.18061/dsq.v33i3.3751

Levent, N., and Reich, C. (2013). Museum accessibility: combining audience research and staff training. J. Mus. Educ. 38, 218–226. doi: 10.1080/10598650.2013.11510772

Marinho, L. (2023). Indicadores de acessibilidade em exposições on-line: a experiência de visitantes com deficiência visual no Museu da Vida Fiocruz (master's dissertation). Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro.

Massarani, L., Alvaro, M. V., Norberto Rocha, J., de Abreu, W. V., Silveira, F., Morales, S. I. F., et al. (2021b). Mediadores de centros e museus de ciência: um estudo sobre os profissionais que atuam na América Latina. Revista Eletrônica do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Museologia e Patrimônio 14, 446–466. doi: 10.52192/1984-3917.2021v14n1p446-466

Massarani, L., Polino, C., de Castro Moreira, I., and Medeiros, L. (2021a). O que os jovens brasileiros pensam da ciência e da tecnologia? Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz/COC; INCT-CPCT.

Meeks, L. M., Nguyen, M., Pereira-Lima, K., Sheets, Z. C., Betchkal, R., Swenor, B. K., et al. (2025). The inaccessible road to science for people with disabilities. Trends Mol. Med. 31, 97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.08.006

Minayo, M. C. S. (2012). Análise qualitativa: teoria, passos e fidedignidade. Ciência and Saúde Coletiva 17, 621–626. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232012000300007

Moote, J., Archer, L., DeWitt, J., MacLeod, E., and Yeomans, L. (2020). Science capital or STEM capital? Exploring relationships between science capital and technology, engineering, and maths aspirations and attitudes among young people aged 17/18. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 57, 1228–1249. doi: 10.1002/tea.21628

Morais, S. B. R. (2019). Inclusão em museus: conceitos, trajetórias e práticas (PhD thesis). Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro; Museu de Astronomia e Ciências Afins, Rio de Janeiro.

Norberto Rocha, J. (2021). Acessibilidade em museus e centros de ciências: experiências, estudos e desafios. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Cecierj e Grupo Museus e Centros de Ciências Acessíveis.

Norberto Rocha, J., Heck, G. S., Marinho, L., and de Carmo, M. P. S. (2023). Esse museu tem sinal em Libras? Glossário de sinais de museus para a inclusão de pessoas surdas. Revista Areté: Revista Amazônica de Ensino de Ciências 21, 1–13. doi: 10.59666/Arete.1984-7505.v21.n35.3662

Norberto Rocha, J., Marinho, L., Heck, G., Carmo, M. P. S., and de Abreu, W. V. (2025). Accessibility in online exhibitions of Brazilian science museums and centers: identifying strategies and barriers. Front. Educ. 10:1542430. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1542430

Norberto Rocha, J., Massarani, L., Abreu, W., Inacio, L., and Molenzani, A. (2020). Investigating accessibility in Latin American science museums and centers. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 92:e20191156. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202020191156

Norberto Rocha, J., Massarani, L., Gonçalves, J., Ferreira, F. B., de Abreu, W. V., Molenzani, A. O., et al. (2017). Guia de museus e centros de ciências acessíveis da América Latina e do Caribe. Rio de Janeiro: Museu da Vida/Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz, RedPOP.

Passos, K. K., de Bernardino, C. G. S., and Norberto Rocha, J. (2024). A ausência da temática da acessibilidade na formação em museologia no Brasil. Anais do Museu Histórico Nacional 58, 1–33.

Polino, C., Massarani, L., and Dawson, E. (2024). Social inequality determines science museums attendance in Latin America: a quantitative analysis of data from seven countries. Mus. Manage. Curatorship 1–33. doi: 10.1080/09647775.2024.2357069

Reich, C. (2014). Taking action toward inclusion: Organizational change and the inclusion of people with disabilities in museum learning (doctoral dissertation). Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, United States.

Reich, C., Lindgren-Streicher, A., Beyer, M., Levent, N., Pursley, J., Mesiti, L. A., et al. (2011). Speaking out on art and museums: A study on the needs and preferences of adults who are blind or have low vision [Report]. Boston: Museum of Science.