- 1School of Public Health, KAHER, Belagavi, Karnataka, India

- 2Department of Microbiology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Belagavi, Karnataka, India

- 3Public Health Foundation of India, Gurugram, Haryana, India

Background: Public health education in India faces several challenges like non-uniform curricula, limited emphasis on experiential and competency-based learning, and inadequate infrastructure. Addressing these challenges demands significant changes in public health education to align it with Sustainable Development Goals 4 and National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 in particular. To overhaul the Masters of Public Health (MPH) program with a focus on holistic and multidisciplinary approaches, objective of this paper was to propose a framework for MPH program in alignment with NEP 2020.

Methods: A thorough desk review of NEP 2020 for reforms in higher education was conducted. Nine documents by University Grants Commission (UGC) detailing implementation of the policy at higher education level were reviewed for their relevance to MPH programs. Various guidelines to align MPH programs with policy’s proposed reforms were identified. MPH framework was developed on the basis of these guidelines.

Results: MPH programs in India are not in alignment with NEP 2020 reforms. The framework suggested in this study includes guidelines on: (1) Flexible career pathways, (2) multiple entry and multiple exits, (3) levels, level descriptors, qualification specifications and graduate attributes, (4) credit system and Academic Bank of Credit, (5) evaluation and assessment, (6) Incorporation of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC), Indian Knowledge System (IKS) Courses and Courses on Human Values and Ethics, and (7) provisions for recognition of prior learning (RPL) thus aligning the MPH program with selected policy reforms.

Conclusion: MPH programs can be aligned with certain reforms suggested by NEP 2020. The proposed framework can provide a solid background for transforming MPH programs in India, making them more flexible, interdisciplinary, research oriented and improving their quality.

Background

India’s first public health education institute, the All-India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health (AIIHPH) was established in Kolkata in 1932 and is dedicated exclusively to public health education and research (Bangdiwala et al., 2011). Since the late 19th century, medical colleges in India have offered various public health courses to medical practitioners (Sharma and Zodpey, 2011). Medical students receive this training during their second year in medical school as a “preventive and social medicine/community medicine” course, or they can pursue Doctor of Medicine (MD) in a community medicine degree, diploma in public health (DPH), or diploma in community medicine (DCM) after graduation (Sharma and Zodpey, 2013). Public health education for nonmedical students in India began to gain prominence in the early 2000’s when a high-level expert group for universal health coverage suggested the introduction of postgraduate courses in public health for healthcare and nonhealthcare graduates (Joshi et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic further increased the demand for public health education (Magaña and Biberman, 2022). As of 2024, 129 MPH programs, including general and specialized programs, are running in the country (Dhagavkar et al., 2024).

Despite the acknowledged importance of education in public health for national development, the program faces several persistent challenges, such as inadequate infrastructure, limited faculty, nonuniform curricula, the absence of a professional council, a lack of robust policy support and regulation and underrepresentation of public health in medical education with cultural and language barriers, exacerbating these issues (Chauhan, 2011; Miller et al., 2022). To overcome these challenges, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is critical for providing high-quality public health education to young public health professionals to achieve sustainable developmental goal 4 (SDG 4), which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030 (Saini et al., 2023). Achieving such an ambitious target necessitates rapid transformation in India’s educational landscape, a transformation that the NEP 2020 seeks to catalyze.

NEP 2020, is the third major education policy of India, following the Education Policies of 1968 and 1986. Its formulation was initiated in 2015 through extensive nationwide consultations involving experts, teachers, students, and civil society stakeholders. A Draft NEP was released in 2019 by a committee chaired by former Indian Space Research Organization chief Dr. K. Kasturirangan, which laid the foundation for wide-ranging reform across the education system (Kumar, 2021). The policy emphasizes nurturing the creative potential of each individual, advocating for an education system that not only develops cognitive capacities such as critical thinking and problem solving but also fosters social, ethical, and emotional development (Swargiary and Roy, 2023). While previous efforts in MPH education focused largely on curriculum standardization and expansion of seats, they often failed to bridge the gap between policy directives and institutional realities (Upadhyay et al., 2023). Hence this study was conducted with an objective to propose a framework for the MPH program in alignment with NEP 2020.

The proposed framework is innovative because it contextualizes NEP provisions specifically for MPH programs rather than treating them generically, and integrates global best practices such as competency-based training and credit portability with Indian Knowledge Systems (IKSs) and values-based education. This approach adds value by explicitly addressing long-standing gaps of fragmented curricula, limited employability pathways, and lack of international recognition of Indian MPH programs.

Methods

A thorough desk review of the NEP 2020 (Ministry of Human Resource Development GOI, 2020) for reforms in higher education was conducted. To ensure rigor and transparency, documents were identified from the official UGC and Ministry of Education websites (January–April 2024). Inclusion criteria required that documents directly addressed postgraduate education frameworks, credit systems, evaluation mechanisms, or curriculum design. Documents focusing exclusively on undergraduate or school-level reforms were excluded. This process yielded nine relevant UGC documents detailing the implementation of the NEP 2020 at the higher education level. They were reviewed for their relevance to MPH programs.

1. The National Higher Education Qualifications Framework (NHEQF): Levels, level descriptors, qualification specifications and graduate attributes for MPH programs were formulated using this document (University Grants Commission, 2023a).

2. National credit framework (NCrF): Credits, credit points and notional learning hours relevant to higher education were derived from this document and adapted for MPH programs. Recognition of prior learning (RPL) can also be provided for students enrolled in MPH programs under this provision, as suggested in this document (University Grants Commission, 2023b).

3. Guidelines for Multiple Entry and Exit in Academic Programs Offered in Higher Education Institutions: This document was used to frame multiple entry and exit pathways for MPH students (University Grants Commission, 2021).

4. Curriculum and Credit Framework for Post Graduate Programs: Choices of curricular components as well as credits, credit points and notional learning hours relevant to higher education were adapted for MPH programs from this document (University Grants Commission, 2016a).

5. UGC Regulation on Credit Framework for Online Learning Courses Through Study Webs of Active-Learning for Young Aspiring Minds (SWAYAM): Guidelines from this document were used for incorporation of courses offered through the SWAYAM portal in the MPH program (University Grants Commission, 2016b).

6. UGC Regulation on the Establishment and Operation of the Academic Bank of Credits in Higher Education: This document was also used to adapt credits, credit points and notional learning hours relevant to higher education to the MPH program (University Grants Commission, 2016c).

7. Guidelines for Incorporating Indian Knowledge in the Higher Education Curriculum: These guidelines were used to incorporate a part of the IKS curriculum in the MPH program (University Grants Commission, 2023c).

8. Inculcation of Human Values and Professional Ethics in Higher Education Institutions: This document was used to incorporate a part of the curriculum suggested by the UGC on Human Values and Professional Ethics in the MPH program (University Grants Commission, 2023d).

9. Evaluation Reforms in Higher Educational Institutions: This document refers to various reforms in evaluation of students that could be used in MPH programs (University Grants Commission, 2023e).

Process of thematic synthesis

Key provisions relevant to postgraduate education were extracted from each document using a structured template. These provisions were then mapped against the existing structure of MPH programs in India. Areas of convergence, gaps, and opportunities for adaptation were identified. A narrative synthesis approach was applied to integrate findings across the nine UGC documents, ensuring that the proposed framework reflects both policy intent and applicability to MPH education. The extracted elements were synthesized into 7 thematic categories to form the basis of the proposed framework. Stakeholder consultations or consensus-building exercises were not undertaken for this version of the framework.

Results

MPH programs in India are not in alignment with NEP 2020 reforms (Dhagavkar et al., 2024). Based on the narrative synthesis, the proposed framework was organized around the following seven thematic categories:

1. Flexible career pathways.

2. Multiple entry and multiple exits.

3. Levels, level descriptors, qualification specifications and graduate attribute.

4. Credit system and Academic Bank of Credit.

5. Evaluation and Assessment.

6. Incorporation of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC), IKS Courses and Courses on Human Values and Ethics.

7. Provisions for RPL.

The seven thematic categories emerged inductively from the narrative synthesis of the nine NEP/UGC documents. These categories were selected because they directly address persistent challenges in MPH education, including fragmented curricula, lack of standardization, limited employability, and absence of international recognition. After the categories were identified, their relevance to MPH education was examined, revealing that they align closely with persistent challenges such as fragmented curricula, lack of standardization, limited employability, and insufficient global recognition. These post-hoc observations helped explain why the emergent categories are particularly salient for strengthening MPH programs and ensuring alignment with both NEP 2020 priorities and the competencies expected of public health professionals.

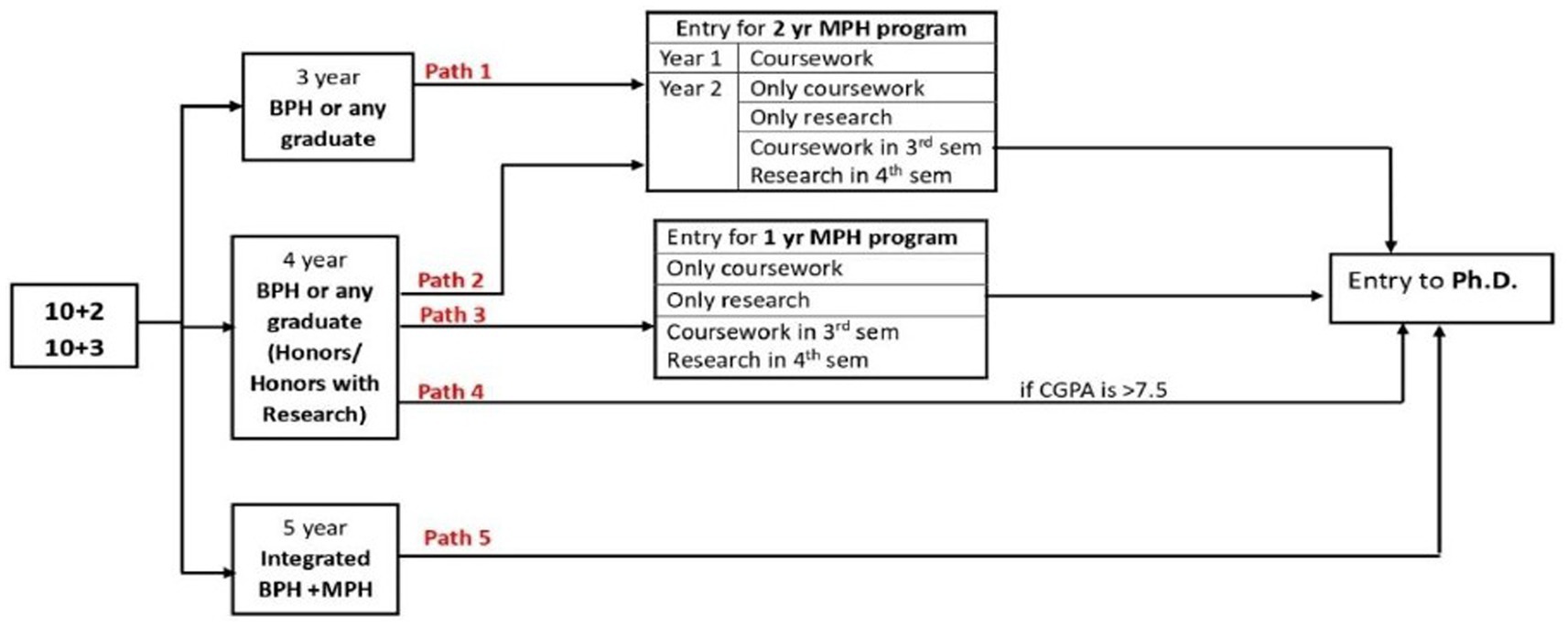

As depicted in Figure 1, after completing secondary education, students can choose various academic career pathways in the field of public health. They may choose a 3-year bachelor’s programme in public health, a 4-year bachelor’s programme (honors) in public health with the last year dedicated to research (honors with research) or an integrated 5-year programme in public health, including bachelors as well as masters.

After a 3- or 4-year bachelor’s degree in public health the student may choose to opt for either a 1- or 2-year master’s degree program. This path may also be followed by students from other health as well as non-health background.

A Ph.D. can be pursued either after the master’s degree of 1, 2 or 5 years or after a 4-year bachelor’s degree if the student scores CGPA >7.5.

Public health students can choose to exit the program after completing a specific number of credits and at specific levels. They can return later to complete their education or pursue another program where these credits can be transferred. After completing a 3-year bachelors program, students can choose to enter a 2 year masters program and exit after 1 year with a PG diploma or after 2 years with a masters degree. After completing a 4-year bachelors program, students can choose to enter either a 1 year or a 2 year master’s program and exit with a master’s degree but at different levels. Students can choose their course components depending on the point of entry into the program as shown in Figure 2.

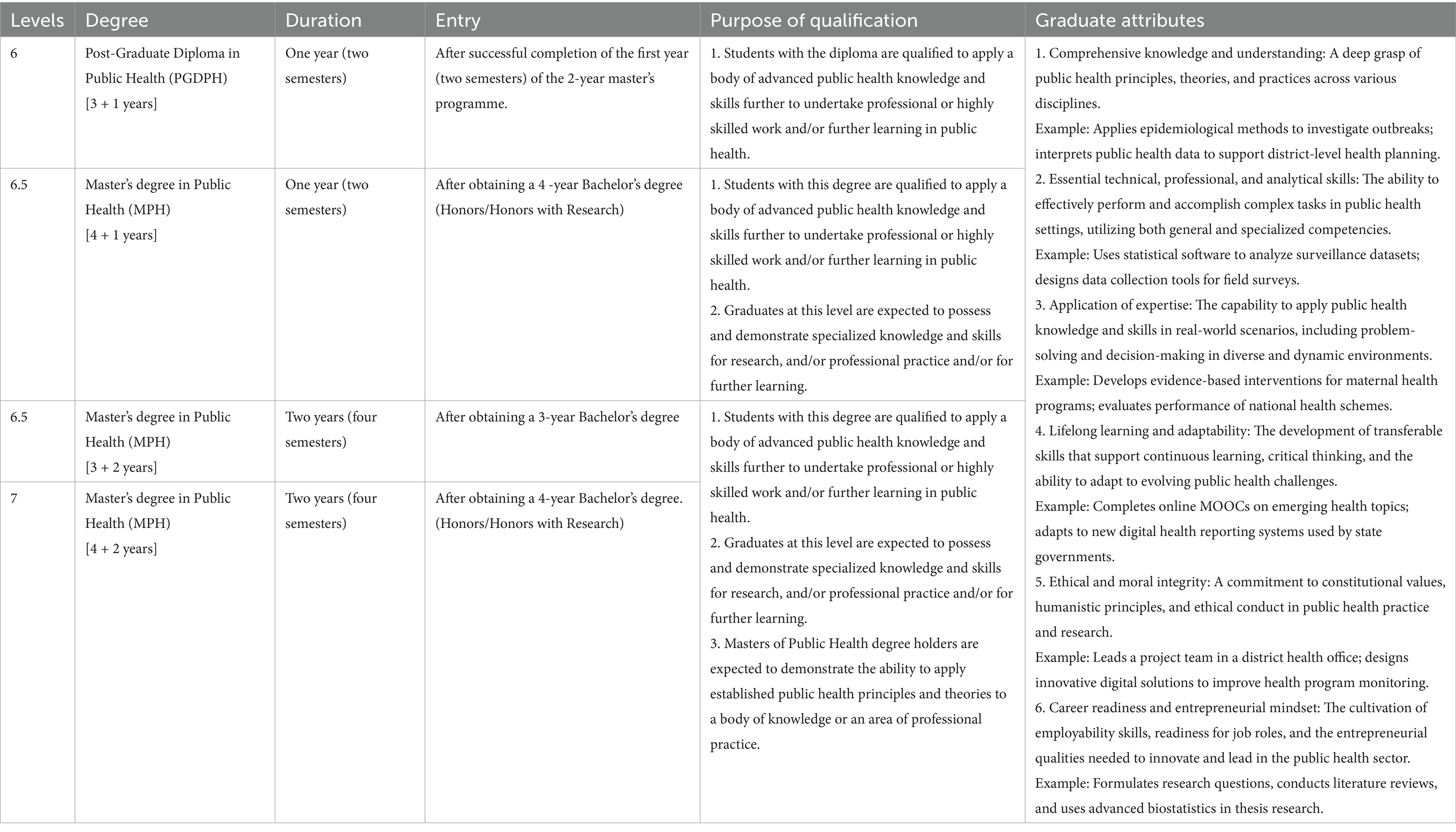

Table 1 shows that, The NHEQF levels are a series of sequential stages, expressed in terms of the range of learning outcomes against which qualifications are located. Levels 6, 6.5 and 7 are relevant to postgraduate programs. Diploma/degree in public health will be awarded to students who have demonstrated achievement of the outcomes associated with the specific NHEQF level. Graduate attributes for all PG programs in general have been suggested in the policy, which can be modified for MPH programs. Postgraduate degrees in public health are awarded to students who demonstrate these attributes.

Table 1. Levels, level descriptors, qualification specifications and graduate attributes for MPH students.

Public health students earn credit for completing various courses and training modules subject to assessment as seen in Table 2. These credits are independent of the mode of learning. Credit points are obtained by multiplying the credits earned with the NCrF level.

ABC is a national-level facility that digitally keeps records of all the learning of a student throughout life in a common account. The credits are stored, transferred and applicable across different educational contexts via the ABC. Higher education institutes are required to register in ABC. Upon obtaining a certificate/diploma, those credits will be deleted from account. Credits are deposited for a maximum of 7 years. Only those credits obtained during or after the year 2021–2022 are eligible for transfer.

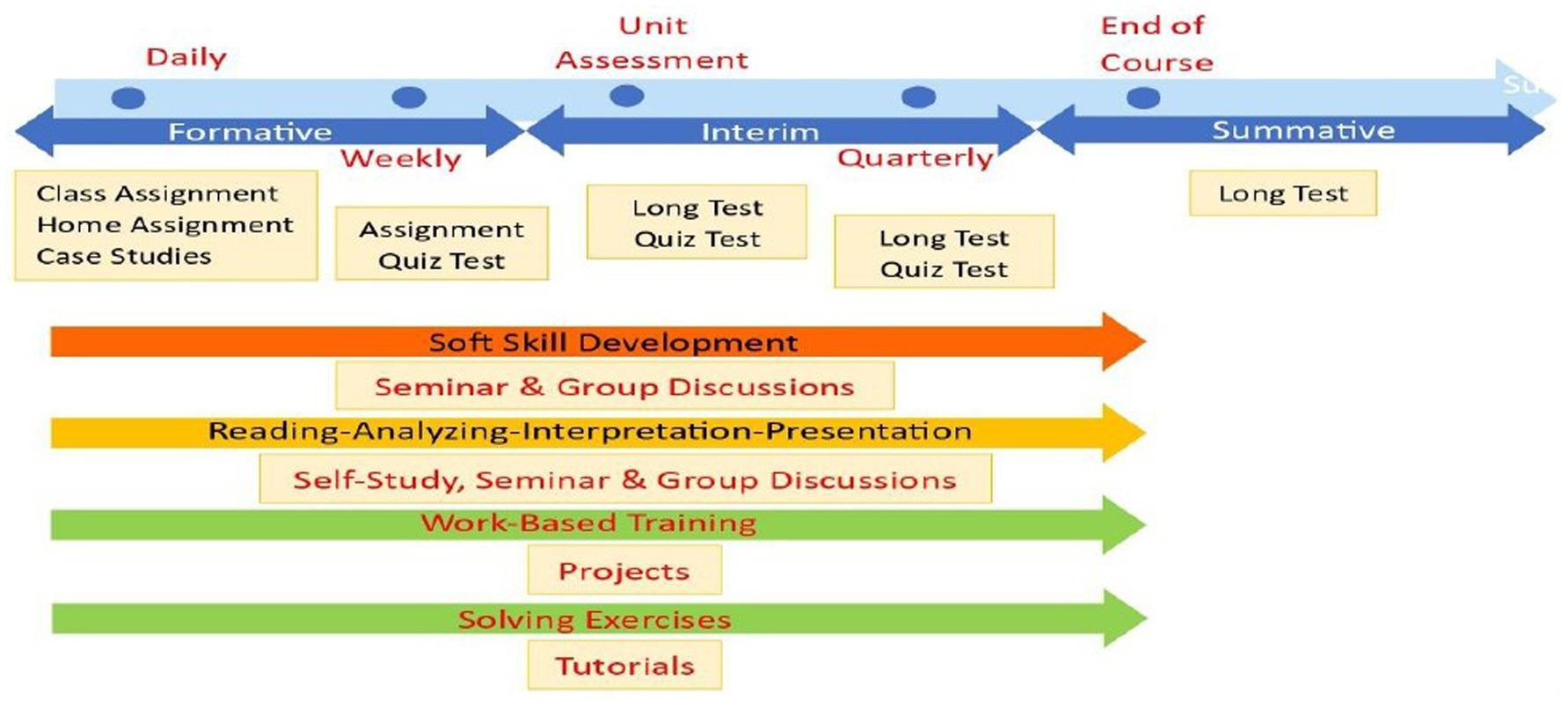

Assessment continuum as given in Figure 3 is the best practice suggested by the NEP 2020. This can be used to assess the progress of MPH students. It involves triangulating assessment data via several different sources in a continuous and formative manner, as indicated in the figure. Further assessment will correlate with the learning outcomes.

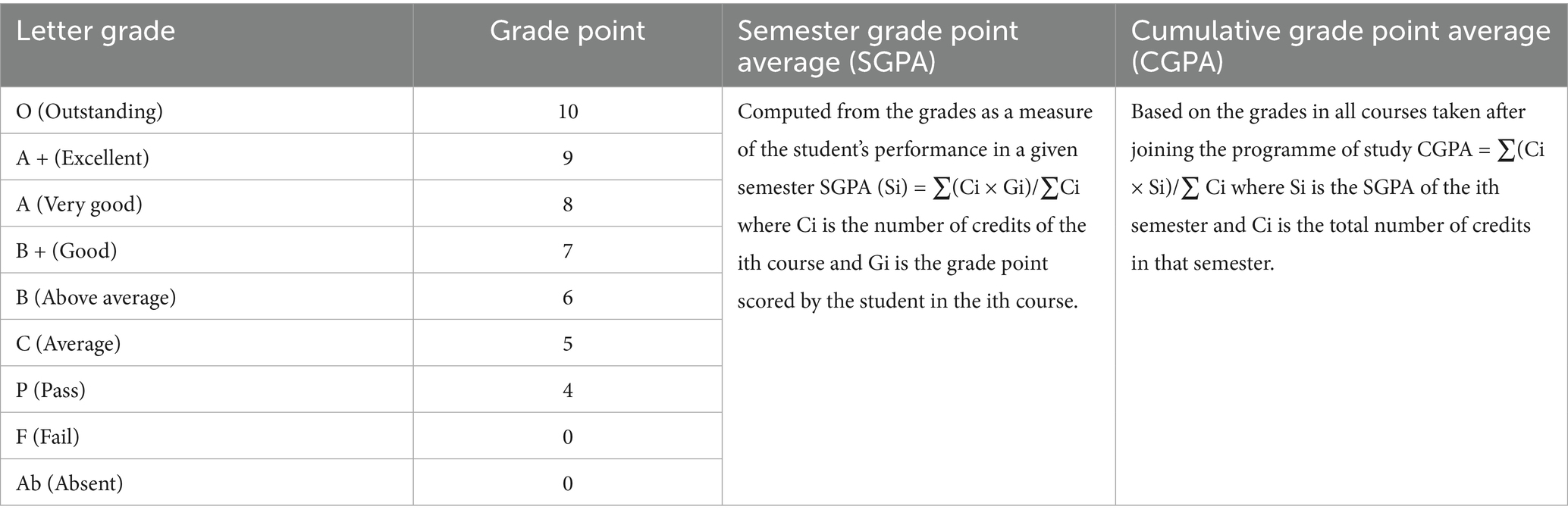

Grade Point Averages as depicted in Table 3 can be used for evaluation of MPH students after continuous, formative and summative assessment. For noncredit courses, ‘satisfactory’ or ‘unsatisfactory’ will be indicated instead of the letter grade, and this will not be considered in the computation of the SGPA/CGPA.

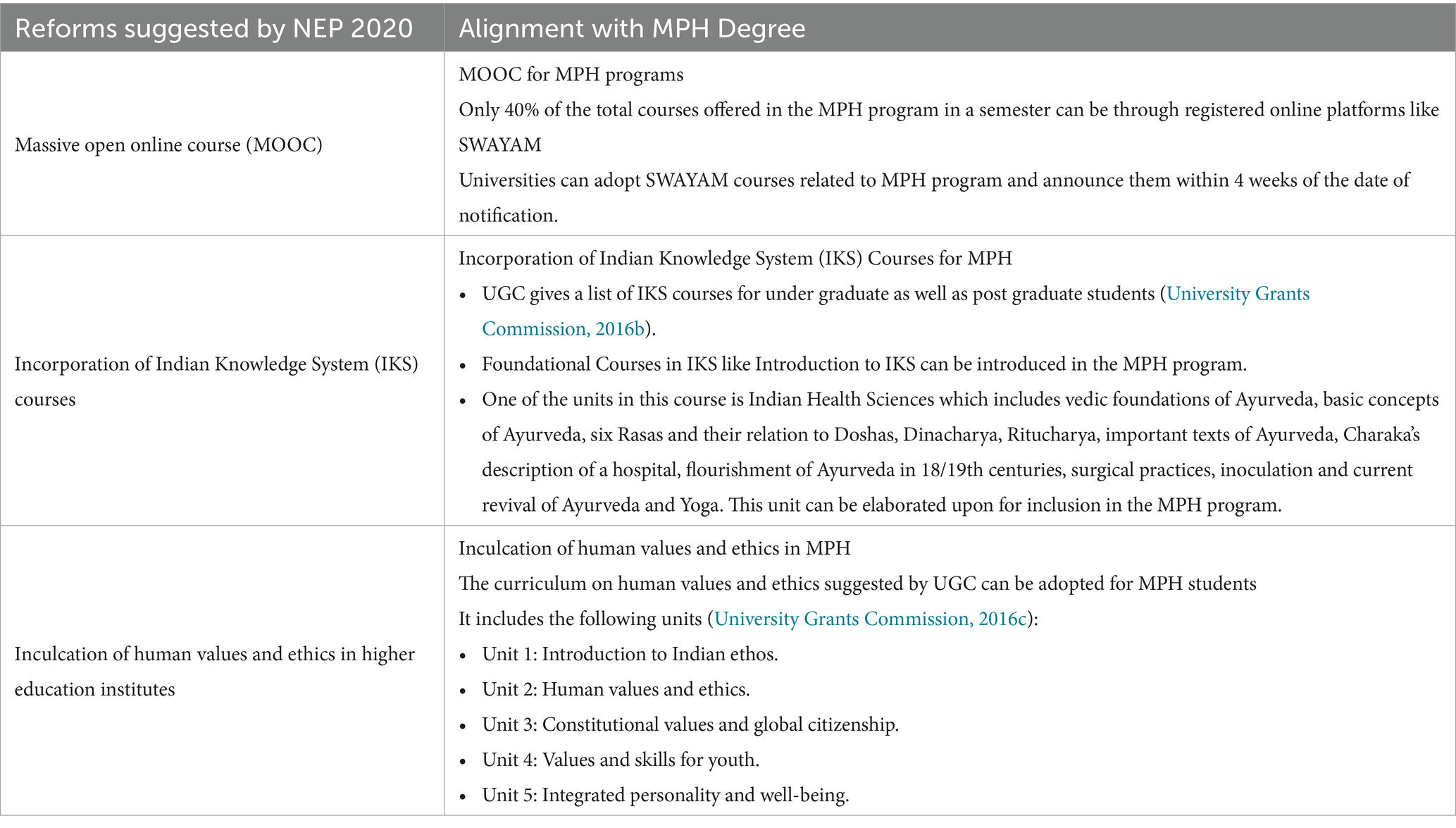

Table 4 shows how the MOOCs, IKS courses and courses on Human Values and Ethics can be incorporated in MPH program curriculum.

Table 4. Incorporation of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), Indian Knowledge System (IKS) courses and courses on human values and ethics in MPH programs.

MPH students can enroll in the RPL as given in Table 5. It recognizes learning that has been developed from experience and allows students to bypass redundant coursework. Credits are given for their experience subject to assessment. The focus is on acquiring new, specialized knowledge that will enhance their careers. When experiential learning is part of employment, the learner would earn credits as weightages between 1 and 2 on the basis of the relevant work experience and proficiency/professional levels achieved. Although there are existing practices already in place for calculating credit for prior learning, the framework follows the credit calculations given in the NCrF as follows (University Grants Commission, 2023b).

Discussion

NEP 2020 recognizes that higher education plays an extremely important role in promoting human and societal well-being. It calls for a complete overhaul and re-energizing of the higher education system to deliver high-quality higher education with equity and inclusion. The policy’s vision includes several key changes to the current system, such as moving toward more multidisciplinary education and revamping the curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, and student support for enhanced student experiences. This policy presents a valuable opportunity to reform the public health education system in the country.

India is currently grappling with multiple public health crises, including the rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, persistent infectious diseases like tuberculosis and dengue, maternal and child health challenges, and the increasing impact of environmental and climate-related health risks (Kumar, 2024). These issues are compounded by disparities in healthcare access, workforce shortages, and gaps in health infrastructure (Soni and Kumari, 2025). In this context, aligning Master of Public Health (MPH) programs with the NEP 2020 is crucial to addressing these challenges effectively. NEP 2020 emphasizes a multidisciplinary, flexible, and technology-driven approach to education, fostering skill development, research innovation, and intersectoral collaboration. By integrating these principles into MPH curricula, public health education can be made more relevant, evidence-based, and solution-oriented, equipping professionals with the necessary competencies to tackle India’s evolving health crises.

India’s public health system depends on doctors, nurses, and community health workers (CHWs) like Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), who are essential in delivering healthcare. Strengthening their skills through education is crucial, and aligning MPH programs with the NEP 2020 offers a transformative approach. Integrating epidemiology, health policy, and digital health tools into MPH curricula can empower medical professionals as public health leaders. Nurses can benefit from skill-based training in health promotion and disease surveillance, while CHWs and ASHAs need competency-based training and digital learning for improved healthcare delivery. NEP 2020’s emphasis on multidisciplinary, research-driven, and technology-enabled education can bridge public health training gaps, fostering a skilled workforce and a resilient, equitable healthcare system for India’s future.

Flexibility is the hallmark of this policy. Flexible academic career pathways, along with multiple entry and exit pathways for MPH programs, can create more dynamic, student-centered learning environments that can prepare postgraduates to be adaptable, innovative, and well-rounded public health professionals. The choice of coursework or research component for MPH postgraduates will not only enhance their learning experience but also equip them with specialized knowledge, multidisciplinary skills, and the adaptability needed to succeed in the diverse and evolving field of public health.

Aligning MPH programs with the requirements of NCrF, NHEQF and ABC will facilitate international equivalence and transfer of credits (Hovenga and Mantas, 2004; Groome and Cunningham, 2024). The NCrF and ABC provide a unified structure for measuring, storing and transferring academic credits, which can be recognized by institutions worldwide, whereas the NHEQF establishes clear learning outcomes and qualifications at each level of higher education. Together, these frameworks can enhance the global mobility and internationalization of MPH graduates. This enables them to seamlessly continue their education or careers in international settings and contributes to the global public health workforce. The credit accumulation and transfer mechanism provided by ABC may even enable prospective employers to verify the public health competencies achieved by a candidate in terms of credits and map their job requirements. ABC acts as a bridge for employability, meaning that it will enable public health employers to access the credits accumulated and stored to establish the eligibility of a candidate for a particular public health job.

The NHEQF provides specific descriptors for each graduate attribute at the postgraduate level. These descriptors can be tailored to the MPH program. Likewise, program learning outcomes (PLOs) for the MPH degree can be developed to align with the corresponding qualification descriptors at the relevant NHEQF level, whereas course learning outcomes (CLOs) can be designed to connect with certain, but not all, graduate attributes. To effectively formulate these descriptors, PLOs, CLOs, national consultations and consensus-building efforts involving a diverse range of public health stakeholders are essential.

Formative and continuous assessment, as suggested by the NEP 2020, will offer significant benefits to MPH students by providing ongoing feedback, enhancing learning, and supporting their academic and professional development. Students will be able to identify strengths and areas for improvement, address knowledge gaps, and refine their understanding of complex public health concepts. The iterative nature of these assessments’ mirrors professional practices. Students are prepared for their future roles while enhancing motivation and engagement. Overall, formative and continuous assessments provide MPH students with a robust framework for improvement and preparation, contributing to their success in the public health field.

The incorporation of MOOCs and IKS courses, along with the increase in human values and ethics, as suggested by the NEP 2020, can significantly enhance the educational experience of MPH students. MOOCs provide access to a wide array of specialized content and global perspectives. IKS courses can integrate traditional Indian practices and philosophies relevant to public health in mainstream education. This inclusion enriches students’ understanding of diverse health approaches and cultural contexts. Additionally, embedding human values and ethics into the curriculum ensures that MPH students not only are well versed in their technical skills but are also grounded in principles of integrity, compassion, and social responsibility. This holistic approach will prepare students to address public health challenges from a balanced perspective, integrating scientific knowledge with ethical considerations and cultural sensitivity.

Provisions for RPL offer significant advantages for MPH students by acknowledging and accrediting their existing knowledge and skills acquired through work experience, informal learning, or prior education. RPL allows students to gain academic credit for competencies in public health that they have already mastered, thereby reducing the time and cost needed to complete their MPH degree. This recognition will help streamline their educational journey by exempting them from repeating content they are already proficient in, allowing them to focus on advanced topics and new areas of study. This not only accelerates their path to the MPH degree but also enhances their engagement and motivation by aligning their studies with their real-world expertise.

The National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 emphasized public health with the suggestion of establishing a public health cadre in each state (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare GOI, 2017). It set an agenda for health priorities, workforce development, and overall public health infrastructure that act as a guide for the development of public health education in the country. The suggestions from the NHP 2017 can be closely integrated with those of the NEP 2020. Both policies emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary education; additionally, the NEP’s emphasis on flexible and inclusive learning paths can be utilized to incorporate the NHP’s focus on preventive and promoting health.

Despite the promise of NEP 2020, implementation in MPH programs may encounter challenges. Institutional resistance to change is common, particularly where faculty lack experience with flexible credit frameworks or competency-based teaching. Resource constraints such as inadequate infrastructure, limited digital access, and shortage of trained faculty present additional risks. Regional disparities mean that elite urban institutions may adopt reforms more quickly than smaller universities in underserved areas, thereby widening inequities (Upadhyay et al., 2023). Mitigation strategies include phased rollouts of reforms, faculty development workshops, and leveraging digital platforms for cost-effective scaling. Establishing regional centers of excellence and promoting inter-institutional collaborations can reduce disparities, while clear monitoring and evaluation frameworks can help sustain reform momentum (World Health Organization, 2021).

Historically, MPH faculty in India were predominantly from medical backgrounds, especially Community Medicine, due to the concentration of public health training within medical colleges (Sharma and Zodpey, 2011; Miller et al., 2022). With the expansion of MPH programs into general universities, faculty now come from diverse disciplines such as epidemiology, sociology, statistics, nutrition, environmental health, and health management. However, many still lack formal public health training or pedagogical preparation needed for competency-based teaching (Joshi et al., 2022). Strengthening faculty development is therefore critical for implementing NEP 2020 reforms effectively.

Nonetheless, NEP 2020 also presents several opportunities for enhancing the quality and relevance of MPH degrees. It encourages the establishment of uniform frameworks and accreditation processes to address issues of quality and consistency across institutions, ensuring uniform educational outcomes. The policy advocates leveraging technology to facilitate remote and blended learning, making public health education more accessible and adaptable to diverse learning needs. Furthermore, NEP 2020 emphasizes the importance of research and collaboration between academia, industry, and government, which can lead to the integration of real-world insights and innovative practices into the curriculum. Finally, by enhancing the global competitiveness of Indian MPH graduates through international partnerships and exposure to global best practices, NEP 2020 ensures that graduates are well prepared to tackle both domestic and international public health issues effectively.

Unlike earlier reform attempts that emphasized curriculum expansion without structural flexibility, the proposed framework adds value by combining NEP 2020 directives with context-specific adaptations. Innovations include embedding IKSs and ethics courses into global competency-based MPH training, enabling academic credit transferability, and aligning graduate attributes with employability pathways. International experiences demonstrate that competency-based public health education improves workforce readiness. In China, nationwide MPH reforms emphasized applied competencies, leading to enhanced graduate employability (Bangdiwala et al., 2011). In the US, accreditation standards from the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) foster continuous assessment and global recognition of MPH graduates (Calhoun et al., 2012). The UK has similarly transitioned toward outcome-oriented public health curricula, strengthening research capacity and international collaboration (Frenk et al., 2010).

Although NEP 2020 provides a comprehensive reform framework for higher education in India, its successful implementation in MPH programs also depends on the presence of discipline-specific accreditation mechanisms. At present, India does not have a dedicated public health accrediting body—unlike medicine, nursing, or allied health sciences. This regulatory gap has been highlighted as one of the major reasons for the wide variability observed across MPH programs (Dhagavkar et al., 2024). Establishing a national public health accreditation mechanism—similar to the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) in the United States or the Agency for Public Health Education Accreditation (APHEA) in Europe—has been recommended in previous studies(Bangdiwala et al., 2011; Calhoun et al., 2012). Such an accrediting body would complement NEP 2020 by translating its broad mandates into discipline-specific standards and by monitoring the implementation of NEP reforms.

Since NEP 2020 reforms for MPH programs are still in the early stages of roll-out, there are currently no published case studies, pilot experiences, or stakeholder consultations available specific to MPH implementation in India. As the objective of this paper is to propose a conceptual framework derived from existing NEP 2020 and UGC guidelines, detailed institutional-level implementation evidence lies beyond the present scope. National consultations will be essential for future framework validation.

Conclusion

Given that the MPH degree is inherently multidisciplinary and not governed by a formal professional council such as the National Medical Commission (NMC), fully integrating MPH education within the scope of the NEP 2020 presents challenges. However, MPH programs in India have the potential to align with certain key reforms outlined in NEP 2020. Comparative insights from China, the US, and the UK suggest that NEP-aligned MPH reforms are likely to enhance graduate employability, expand educational equity, strengthen research capacity, and increase the global competitiveness of Indian MPH graduates. Taken together, the proposed framework represents a significant step forward in reimagining MPH education for India’s future public health workforce. This can provide a solid framework for transforming MPH programs in India, making them more flexible, interdisciplinary, and research oriented and improving their quality.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA: Writing – review & editing. PD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JN: Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author SZ declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bangdiwala, S. I., Tucker, J. D., Zodpey, S., Griffiths, S. M., Li, L. M., Reddy, K. S., et al. (2011). Public health education in India and China: history, opportunities, and challenges. Public Health Rev. 33, 204–224. doi: 10.1007/BF03391628

Calhoun, J. G., Ramiah, K., Weist, E. M., and Shortell, S. M. (2012). Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree. Am. J. Public Health 102, 159–169. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117978

Chauhan, L. S. (2011). Public health in India: issues and challenges. Indian J. Public Health 55, 88–91. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.85237,

Dhagavkar, P. S., Angolkar, M., Nagmoti, J., and Zodpey, S. (2024). Mapping of MPH programs in terms of geographic distribution across various universities and institutes of India—a desk research. Front. Public Health 12, 1443844–1443851. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1443844,

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems. Lancet 376, 1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

Groome, D., and Cunningham, C. (2024). From vocational to graduation: a mixed methods study of support needs for vocational learners pursuing post-graduate education in South Africa. Afr J Emerg Med 14, 263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2024.08.008,

Hovenga, E. J. S., and Mantas, J. (2004). 1.3. Academic standards, credit transfers and associated issues. Glob Health Informat Educ 109:18.

Joshi, A., Bhatt, A., Gupta, M., Grover, A., Saggu, S. R., and Malik, I. V. (2022). The current state of public health education in India: a scoping review. Front. Public Health 10, 970617–970624. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.970617,

Kumar, A. (2021). New education policy (NEP) 2020: a roadmap for India 2.0, vol. 3. Tampa, Florida: University of South Florida (USF) M3 Publishing, 36.

Kumar, R. (2024). “Epidemiological challenges in India” in Handbook of epidemiology (New York, NY: Springer New York), 1–27.

Magaña, L., and Biberman, D. (2022). Training the next generation of public health professionals. Am. J. Public Health 112, 579–581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306756,

Miller, E., Reddy, M., Banerjee, P., Brahmbhatt, H., Majumdar, P., Mangal, D. K., et al. (2022). Strengthening institutions for public health education: results of an SWOT analysis from India to inform global best practices. Hum. Resour. Health 20, 19–24. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00714-3,

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare GOI. (2017). National Health Policy 2017. Available online at: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/9147562941489753121.pdf (Accessed August 16, 2024)

Ministry of Human Resource Development GOI. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. Available online at: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf (Accessed August 16, 2024)

Saini, M., Sengupta, E., Singh, M., Singh, H., and Singh, J. (2023). Sustainable development goal for quality education (SDG 4): a study on SDG 4 to extract the pattern of association among the indicators of SDG 4 employing a genetic algorithm. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 2031–2069. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11265-4,

Sharma, K., and Zodpey, S. (2011). Public health education in India: need and demand paradox. Indian J. Community Med. 36, 178–181. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.86516,

Sharma, A., and Zodpey, S. (2013). Transforming public health education in India through networking and collaborations: opportunities and challenges. Indian J. Public Health 57, 155–160. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.119833,

Soni, P., and Kumari, U. (2025). “Revitalizing health governance: charting a resilient path for India’s future” in Intersecting realities of health resilience and governance in India: Emerging domestic and global perspectives (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 55–73.

Swargiary, K., and Roy, K. (2023). Transforming education: The National Education Policy of 2020. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAP.

University Grants Commission (2016a). Curriculum and credit framework for post graduate programs. New Delhi: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2016b). UGC (credit framework for online learning courses through SWAYAM) regulation 2016. Gazette of India: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2016c). UGC (establishment and operation of Academic Bank of Credits in higher education) regulation 2021. Gazette of India: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2021). Guidelines for multiple entry and exit in academic programs offered in higher education institutions. New Delhi: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2023a). National Higher Education Qualifications Framework. New Delhi: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2023c). Guidelines for incorporating Indian knowledge in higher education curriculum. New Delhi: UGC.

University Grants Commission (2023d). Inculcation of human values and professional ethics in higher education institutions. New Delhi: UGC.

University Grants Commission. Evaluation reforms in higher educational institutions. (2023e). Available online at: https://www.ugc.gov.in/e-book/EVALUATION%20ENGLISH/mobile/index.html (Accessed August 16, 2024).

Upadhyay, K., Goel, S., and John, P. (2023). Developing a capacity building training model for public health managers of low and middle income countries. PLoS One 18:e0272793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272793,

World Health Organization (2021). Global competency and outcomes framework for health workforce education. Geneva: WHO.

Glossary

NEP - National Education Policy

MPH - Masters of Public Health

UGC - University Grants Commission

MOOC - Massive open online courses

IKS - Indian Knowledge System

RPL - Recognition of prior learning

SWAYAM - Study Webs of Active-Learning for Young Aspiring Minds

AIIHPH - All-India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health

MD - Doctor of Medicine

DPH - Diploma in Public Health

DCM - Diploma in Community Medicine

SDG 4 - Sustainable Developmental Goal 4

NHEQF - National Higher Education Qualifications Framework

NCrF - National Credit Framework

PGDPH - Post-Graduate Diploma in Public Health

ABC - Academic Bank of Credits

CLOs - Course learning outcomes

PLOs - Program learning outcomes

NHP - National Health Policy

SGPA - Semester grade point average

CGPA - Cumulative grade point average

Keywords: NEP 2020, MPH program, public health education, policy, Masters of Public Health

Citation: Angolkar M, Dhagavkar PS, Nagmoti J and Zodpey S (2025) National Education Policy 2020 and MPH programs-translating policy to practice. Front. Educ. 10:1683140. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683140

Edited by:

Sunjoo Kang, Yonsei University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Emmanuel D. Jadhav, Ferris State University, United StatesRosemary M. Caron, Saint Anselm College, United States

Copyright © 2025 Angolkar, Dhagavkar, Nagmoti and Zodpey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pooja S. Dhagavkar, ZGhhZ2F2a2FyLnBvb2phQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Mubashir Angolkar

Mubashir Angolkar Pooja S. Dhagavkar1*

Pooja S. Dhagavkar1* Jyoti Nagmoti

Jyoti Nagmoti Sanjay Zodpey

Sanjay Zodpey