- 1Academic Department of Physics, Federal University of Technology – Paraná (UTFPR), Paraná, Brazil

- 2Paraná State Department of Education – SEED/PR, Paraná, Brazil

- 3Federal University of the South and Southeast of Pará (UNIFESSPA), Marabá, Pará, Brazil

- 4International Center of Physics, Institute of Physics, University of Brasília (UnB), Brasília, Brazil

This article presents an innovative interdisciplinary approach to teaching the solar system in lower secondary education (9th grade), grounded in David Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory and the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) methodology. Traditional astronomy teaching often fails to connect with students’ prior knowledge, resulting in superficial and fragmented learning. Addressing this issue is crucial for fostering deeper cognitive engagement and preparing students for complex, interdisciplinary challenges. However, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding integrating Ausubel’s theory with the STEAM approach, particularly in astronomy education at the lower secondary level. The study, conducted with 9th-grade students, employed active learning strategies such as planetarium visits, hands-on model construction, mind mapping, and collaborative projects to foster a holistic understanding of astronomical concepts. The proposal aimed to bridge prior knowledge with new content by integrating these methods, promoting critical thinking and creativity. Results demonstrated significant improvements in students’ ability to articulate and apply astronomical knowledge, highlighting the effectiveness of combining theoretical frameworks with experiential and interdisciplinary activities. The study underscores the potential of such approaches to address challenges in astronomy education, preparing students for contemporary cognitive demands while cultivating a deeper appreciation for the cosmos.

1 Introduction

Astronomy plays a fundamental role in basic education, offering a unique opportunity to integrate different areas of knowledge, such as science, mathematics, history, and geography. In the Brazilian National Curriculum (BNCC), Astronomy is an integral part of the science curriculum for elementary school, with specific learning objectives for the 9th grade that include understanding the Solar System, celestial motions, and the Earth’s position in the universe (BRASIL Ministério da Educação, 2018). By exploring astronomical concepts, students develop essential skills, such as observation, logical reasoning, critical thinking, and scientific investigation. Moreover, the study of astronomy awakens curiosity and fascination for the universe, motivating students to question the world around them and understand their place in the cosmos. This understanding of the universe not only enriches the school curriculum but also promotes a broader and holistic view of knowledge, preparing students to face the challenges of the modern world with an open mind and a deep appreciation for the beauty and complexity of the universe (Vieira et al., 2024).

However, astronomy teaching often faces significant challenges in elementary education despite its recognized importance. Traditional methods frequently prioritize rote memorization of facts and isolated concepts over deep, contextualized understanding (Magron et al., 2022). This approach can lead to fragmented learning that fails to connect with students’ daily lives or prior knowledge, resulting in low engagement and meaningful understanding (Batista et al., 2022a, 2022b). Consequently, there is a pressing need for innovative pedagogical strategies that effectively bridge this gap.

In recent years, the teaching of astronomy has been widely discussed in science education, with research highlighting the need for innovative approaches that transcend traditional teaching methods. Studies such as those by Sitko et al. (2023) and Ferreira et al. (2024) have emphasized the value of active methodologies to increase student engagement. Furthermore, the integration of arts and technology, as proposed by the STEAM approach, has emerged as a promising path for interdisciplinary teaching (Khine and Areepattamannil, 2019; Yakman, 2008). Concurrently, David Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory (MLT) provides a robust theoretical framework for ensuring new knowledge is substantively anchored in the learner’s cognitive structure (Ausubel, 2012; Moreira and Massoni, 2015).

While active methodologies and interdisciplinarity are increasingly advocated, few structured proposals systematically integrate the cognitive principles of MLT with the practical, hands-on approach of STEAM specifically for teaching astronomy in elementary education. This lack of integration risks creating engaging activities that may not lead to lasting conceptual understanding, or conversely, theoretically sound lessons that fail to captivate students. This study addresses this gap by developing and implementing a teaching proposal that intertwines these two frameworks.

In the context, didactic proposals that connect students’ prior knowledge with interactive and meaningful practices have proven particularly effective (Vilaça et al., 2013). This article presents an innovative proposal: the creation and implementation of an educational product, a board game entitled “Via Solare,” which applies astronomical concepts in a playful and interactive manner. The game was tested with 9th-grade elementary school students, highlighting the importance of meaningful materials for the teaching-learning process, as proposed by David Ausubel in his meaningful learning theory (Ausubel, 2012).

The integration of games and playful activities in the teaching of astronomy in particular and physics, in general (Ferreira et al., 2020), is aligned with the STEAM methodology, which integrates science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics. This approach has gained prominence as an effective strategy to promote interdisciplinary and practical education (Khine and Areepattamannil, 2019). Furthermore, the use of educational games has been widely recognized for its ability to engage students, making learning more dynamic, engaging, and memorable (Gee, 2003; Prensky, 2003).

Therefore, the present research aims to investigate the pedagogical potential of games and playful activities in the teaching of astronomy, based on Ausubel (2012) and on recent studies that highlight the effectiveness of active methodologies in the educational context. By proposing the game “Via Solare,” we seek not only to facilitate the understanding of astronomical concepts but also to stimulate students’ interest in science, contributing to a critical, reflective, and engaged approach to education.

To guide this investigation, the study is structured around the following research questions:

1. How does the integration of the STEAM approach with Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory (MLT) influence 9th-grade students’ understanding of the Solar System?

2. To what extent does the proposed teaching sequence (advanced organization, progressive differentiation, and integrative reconciliation) facilitate meaningful learning and interdisciplinary integration?

3. What are the perceived impacts of this hybrid approach on student engagement and the development of critical thinking and creativity?

2 Theoretical framework

The Brazilian educational model has undergone significant changes in recent decades, mainly in terms of recognizing students’ differences and the need to adapt teaching methods to meet their specific needs (Chaves et al., 2021). However, despite these efforts, there are still many criticisms regarding the country’s educational system. This is largely due to insufficient investment in infrastructure and teacher training, as well as ineffective public policies to improve the quality of education. In addition, the Brazilian educational model remains largely focused on conventional teaching methods, which fail to account for the individual differences of students and their diverse ways of learning. This ultimately limits students’ potential.

STEAM education proposes an interdisciplinary integration of knowledge in science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics to prepare students for the challenges of society and the job market. The methodology fosters knowledge integration and learning through collaboration among students (Vygotsky, 1978), making teaching more challenging and engaging (Maia et al., 2021). To implement this model, it is necessary to prepare teachers and choose ways to present concepts in an integrated manner, such as through workshops and classroom debates (Sousa, 2022). This approach also helps to develop socio-emotional skills and can be applied through real-world problems and technological tools. Integrating disciplines in teaching can be a positive path for education.

The implementation of the STEAM approach in schools aims to integrate different areas of knowledge to stimulate creativity, inventiveness, empathy, humanism, and the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes essential for today’s life, such as computational thinking and the “do it yourself” mentality of the maker culture (Martinez and Stager, 2019; Graça et al., 2020). Using this pedagogical approach, students are encouraged to develop their skills autonomously, interactively, and collaboratively through the construction, creation, testing, and problem-solving involved in their projects. The focus on the STEAM approach promotes learning through experimentation, one of the most widely used methods in Brazil (Pugliese, 2020). By implementing active methodologies, students have the opportunity to engage with scientific, technological, and artistic knowledge in an inventive and investigative manner.

However, a critical literature analysis reveals significant challenges in the practical implementation of STEAM. While its potential for engagement and interdisciplinarity is widely recognized, several studies point to weaknesses that can compromise the depth of learning. A common criticism is the tendency for projects to prioritize the practical and technological component at the expense of a solid conceptual foundation, leading to a potentially superficial understanding where students are “doing” without necessarily “understanding” the underlying scientific principles (Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro, 2019). This scenario highlights a crucial gap: the need for a robust theoretical framework that guides the integration of disciplines in a way that ensures engagement and meaningful cognitive internalization of concepts.

This is where David Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory (MLT) offers a robust complementary framework. While STEAM provides the engaging, hands-on, and interdisciplinary methodology, MLT provides the cognitive “glue” that ensures new information is non-arbitrarily and substantively integrated into the learner’s pre-existing cognitive structure (Ausubel, 2012). The state of the art in educational research shows a growing, but still incipient, interest in connecting active methodologies with cognitive theories. Some recent studies have begun to explore this interface, suggesting that the combination can lead to more effective learning outcomes (Ferreira et al., 2020, 2022). However, a specific research gap is evident: there is a lack of structured teaching proposals that explicitly and systematically articulate the principles of MLT (such as advanced organizers, progressive differentiation, and integrative reconciliation) with the stages of a STEAM project, especially in the context of elementary school astronomy education.

The focus on the STEAM approach, by fostering learning based on experimentation and the connection between the aforementioned knowledge areas, offers an ideal scenario for the application of Ausubel’s meaningful learning theory (MLT). While STEAM proposes an interdisciplinary and practical methodology that sharpens students’ curiosity and investigative reasoning, MLT complements this perspective by emphasizing the importance of the coherent and substantive integration of newly acquired knowledge. Therefore, when students are exposed to educational experiences that combine the exploratory practice of STEAM with the cognitivist principles of MLT, new concepts are not only introduced but also deeply internalized and understood, facilitating a process of progressive differentiation and integrative reconciliation. In this way, the combination of these approaches not only enriches the educational experience but also ensures that learning becomes an effective and lasting process (Ausubel, 2012; Ferreira et al., 2020, 2021a, 2022, 2023a, 2023b, 2025).

Therefore, this study addresses this identified gap by developing and implementing a teaching framework that hybridizes STEAM and MLT. Our position is that MLT directly counteracts the main weaknesses of STEAM by providing a precise cognitive sequence for organizing instruction. In this hybrid framework, the hands-on, interdisciplinary activities characteristic of STEAM is strategically planned and sequenced according to the principles of MLT. The advanced organization phase (from MLT) ensures students’ prior knowledge is activated before engaging in STEAM projects. The progressive differentiation phase is operationalized through the distinct stages of the STEAM project (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics), allowing for a gradual and connected construction of knowledge. Finally, the integrative reconciliation phase is achieved through synthesizing and applying knowledge in the final project, a cornerstone of the STEAM approach.

This integrated framework represents an advanced field because it offers a theoretically grounded model to prevent superficiality in STEAM projects. It provides teachers with a clear structure to ensure that the engaging “making” process is intrinsically linked to the “meaning-making” process, leading to a more profound and lasting understanding of astronomical concepts.

As widely known, meaningful learning occurs when new knowledge is integrated in a substantive and non-arbitrary manner with pre-existing conceptual objects. “Meaningful learning occurs when the new material to be learned is related to relevant concepts or propositions already existing in the individual’s cognitive structure in a non-arbitrary and substantive way” (Ausubel, 2003, p. 33). Thus, understanding how meaningful learning occurs is crucial for pedagogical practice. By considering the student’s prior cognitive structure as a key element for learning, teachers can develop pedagogical strategies that promote the construction of knowledge in a meaningful way. Identifying subsumers, it is possible to connect new information to the student’s prior knowledge and promote more meaningful and lasting learning.

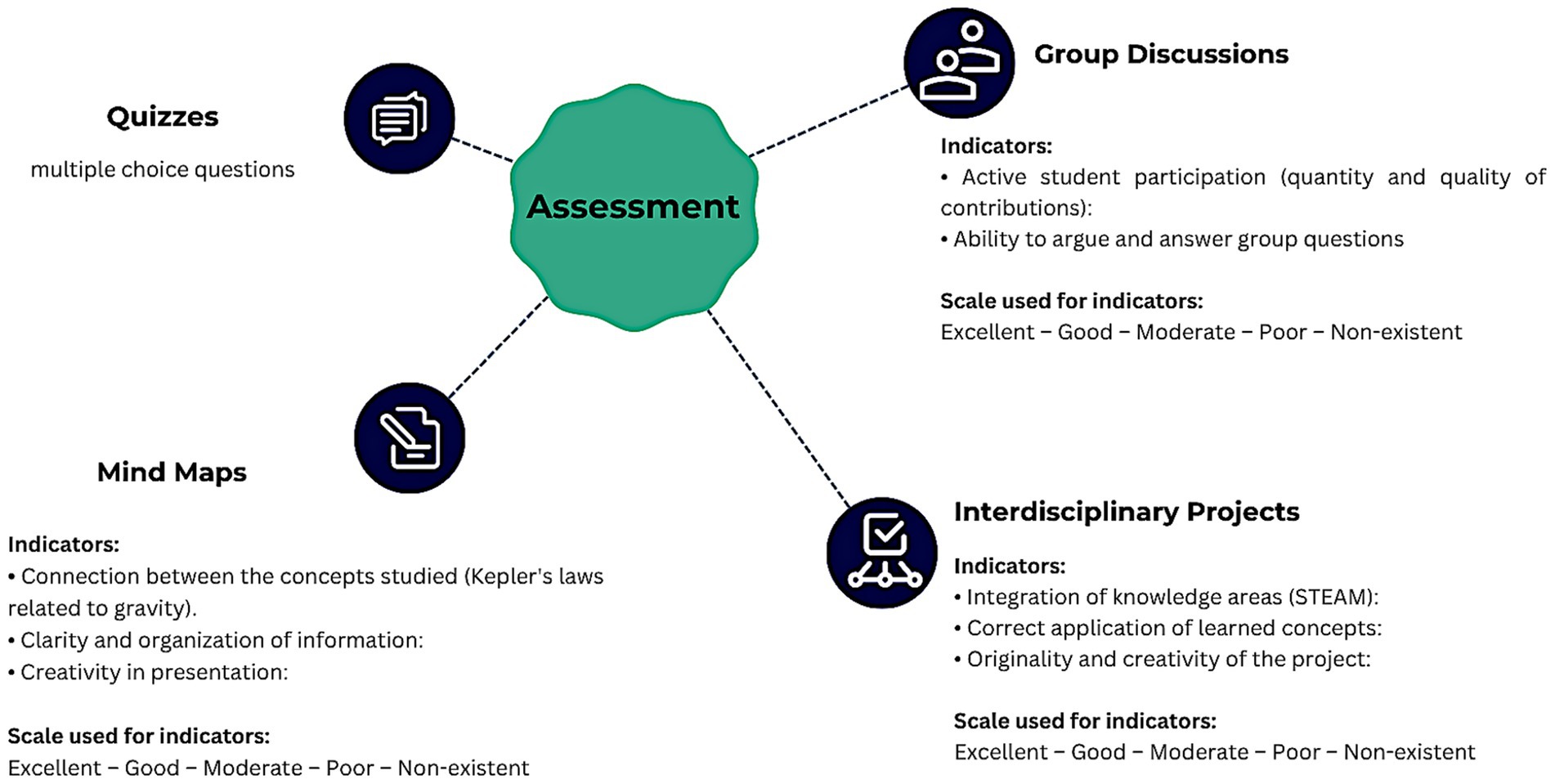

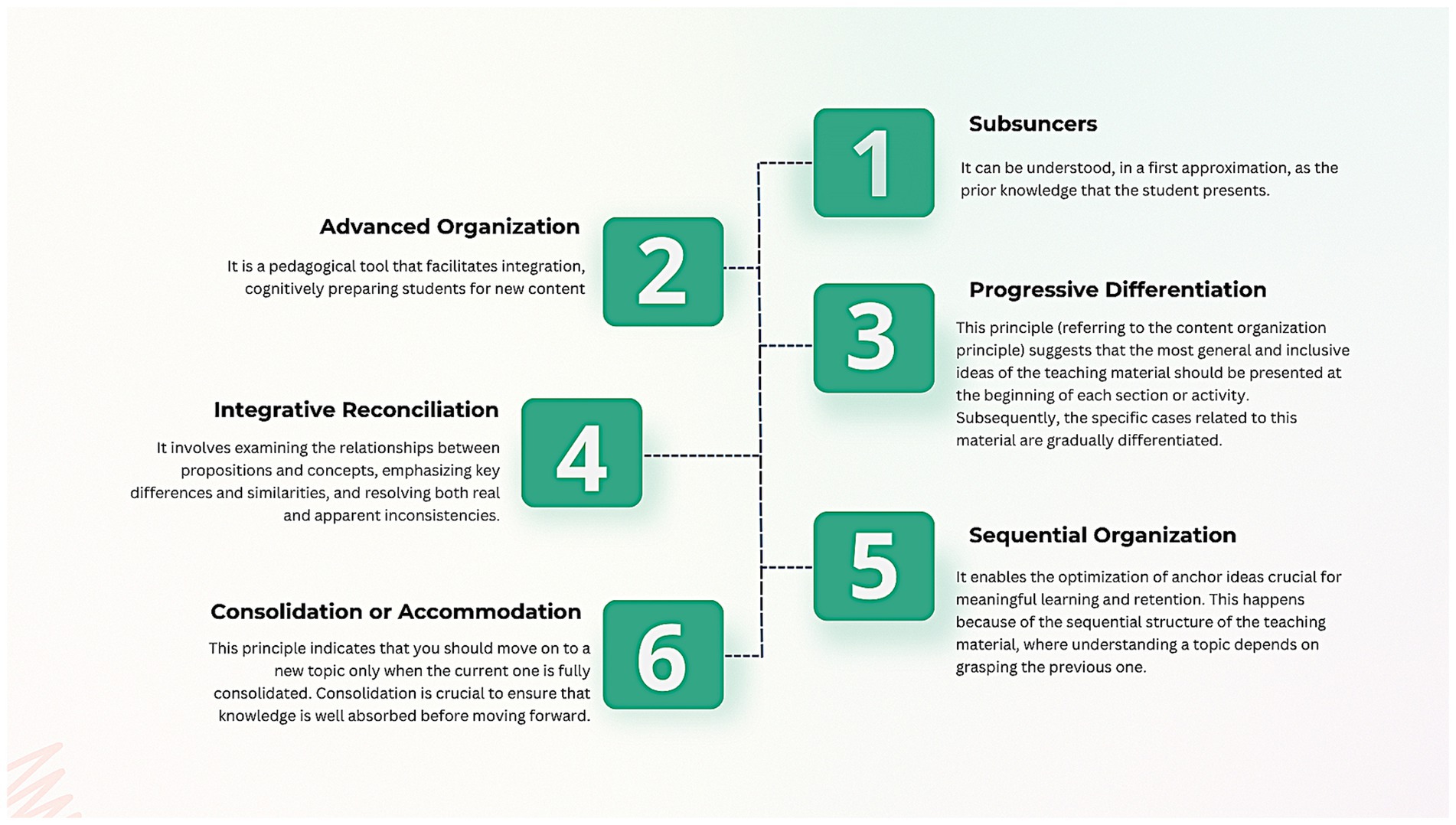

The student’s cognitive structure can be modified through principles related to efficient content programming, which can be applied regardless of the knowledge area. We call these principles subsumers, advanced organizers, progressive differentiation, integrative reconciliation, sequential organization, and consolidation or accommodation, as shown in Figure 1 (Ausubel, 2012; Ferreira et al., 2020, 2021a, 2022, 2023a, 2023b, 2025; Silva Filho and Ferreira, 2022).

Figure 1. Description of principles related to efficient content planning. Source: prepared by the authors.

Teaching materials designed to promote meaningful learning are called potentially meaningful materials, and they must have the property that they must connect to the learner’s cognitive structure in a non-arbitrary way. It is this last constraint that makes these materials only potentially meaningful, since cognitive structures of students may vary, sometimes to a greatly extent. The flexibility of games may help giving these materials their meaningful property (Vilaça et al., 2013; Ausubel, 2012; Ferreira et al., 2020).

It is crucial to acknowledge students’ prior knowledge, even if incomplete or incorrect, to create learning situations that help them assign meaning to the topics being taught (Batista and Gomes, 2021). A crucial stage in meaningful learning involves the teacher making a bridge between students’ prior knowledge and the new content to be taught - what is known as the advanced organization stage. This well-planned stage significantly increases the likelihood of student engagement and success in subsequent phases (Silva Filho and Ferreira, 2022).

In pursuing astronomy teaching that fosters meaningful learning and addresses the aforementioned deficiencies, we argue that teachers must create learning situations during the advanced organization process to enrich students’ experiences. This challenge in basic education can be addressed by leveraging the full pedagogical potential of planetariums, moving beyond their use solely for tourism, leisure or scientific dissemination (Vilaça et al., 2013).

3 Methodological approach

3.1 Research design and context

This study adopts a qualitative descriptive approach, focusing on analyzing and interpreting theoretical data without employing statistical techniques (Batista and Fusinato, 2015; Creswell, 2014). The qualitative approach is particularly suitable for this research, as it allows for an in-depth understanding of the phenomena under investigation, emphasizing the participants’ perspectives and experiences (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

More specifically, this research can be characterized as an instrumental case study (Stake, 1995), as it examines the implementation of a specific teaching proposal (the case) to provide insight into the broader issue of integrating STEAM and Meaningful Learning Theory in astronomy education. In terms of participant selection, a non-probabilistic, intentional sampling technique was employed (Patton, 2015). The sample consisted of a single 9th-grade class from a private school. This choice was justified by the researchers’ access to the field and the class’s typicality regarding the age group and curriculum content relevant to the research objectives, thus facilitating an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon within a defined context.

In terms of methodology, this research employs participant observation, specifically characterized as natural participant observation, since the researcher is already a member of the community being studied. This approach enables the researcher to assume an active and interactive role, engaging deeply with various aspects of the observed phenomenon (Angrosino, 2007). To manage potential bias arising from this insider role, reflexivity and peer debriefing strategies were employed throughout the research process. The lead researcher maintained a reflexive journal to critically examine their own influence, assumptions, and interactions during the study. Furthermore, regular debriefing sessions were held with other co-authors who were not directly involved in the data collection and acted as critical peers to challenge interpretations and minimize subjective bias. The naturalistic setting of the research ensures that the data collected reflects the authentic behaviors and interactions of the participants (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

3.2 Teaching proposal structure and implementation

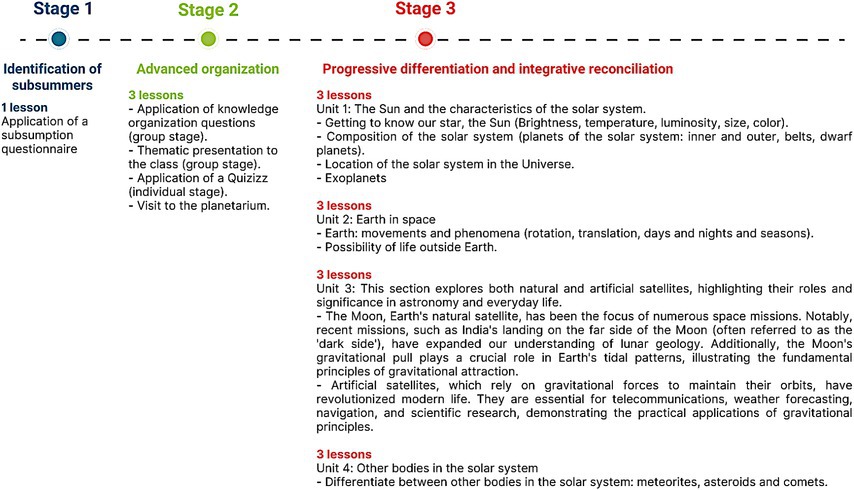

The teaching proposal is structured into 13 in-person classes, divided into three distinct stages. Additionally, asynchronous activities were assigned to students for completion at home. Figure 2 outlines the themes covered in each module.

Figure 2. Presentation of the proposal stages. Source: prepared by the authors based on Reinisz (2024).

3.3 Advanced organization

This initial stage aimed to activate students’ prior knowledge (subsumers) and create a conceptual anchor for new learning.

• Activity 1 (Diagnostic Questionnaire): Students answered a questionnaire with 15 questions designed to map their prior knowledge. The questions were structured based on the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, covering remembering, understanding, and applying levels, and focused on basic concepts of the solar system (planetary order, basic characteristics) (Johnson et al., 2014).

• Activity 2 (Collaborative Group Activities): Students, organized into small heterogeneous groups, engaged in structured activities including fill-in-the-blank exercises and column-matching activities. Each group received one activity at a time, fostering collaboration and discussion. After completion, groups presented their answers to the class, promoting peer learning (Brookfield and Preskill, 2005).

• Activity 3 (Interactive Quiz): An individual low-stakes quiz was conducted using the Quizizz platform, featuring 20 questions of varying complexity (true/false and multiple-choice) to reinforce concepts playfully (Wang, 2015).

• Activity 4 (Planetarium Visit): Students visited the Rodolpho Caniato Planetarium.1 The session focused on the solar system, and a subsequent discussion, guided by the teacher, explicitly connected the visual experience to the concepts that would be studied later, such as gravity (Kolb, 2014).

3.4 Progressive differentiation (STEAM integration)

This stage involved the gradual and differentiated content exploration through interdisciplinary activities, explicitly addressing each component of STEAM.

• Science: Classes focused on the structure of the solar system, Kepler’s laws, and the law of universal gravitation. Discussions connected these concepts to the observations made at the planetarium.

• Technology: Use technological tools to explore the solar system, including observation equipment, satellites, and space missions.

• Engineering: Students designed and built a scaled solar system model. This hands-on project required solving problems related to accurately representing vast distances and relative sizes within the classroom space, applying engineering design principles.

• Arts: Students engaged in artistic expressions related to the theme, such as creating paintings of planets, designing informational posters, and developing the visual layout for the final exhibition of their projects.

• Mathematics: Mathematical concepts were applied to understand astronomical scales. Students performed calculations involving ratios, proportions, and powers of base 10 to determine the correct scales for their solar system model and to comprehend interplanetary distances.

Thus, this approach adheres to the STEAM perspective by fostering interdisciplinary learning and encourages students to apply knowledge across different domains (Yakman, 2008).

3.5 Integrative reconciliation

This phase aims to integrate the concepts and skills acquired across the different areas of knowledge explored during progressive differentiation.

• Final Project “Solar System Exhibition”: The main activity was the development of a collaborative project where students applied all acquired knowledge and skills to create a comprehensive exhibition for the school’s science fair (Hmelo-Silver, 2004). The project involved the construction of a functional prototype demonstrating the translational and rotational movements of celestial bodies, the display of the scaled solar system model, and the presentation of informational lapbooks and mind maps.

• Group Discussions: Students participated in guided discussions to articulate the connections between the concepts learned across the different STEAM areas, promoting integrative reconciliation.

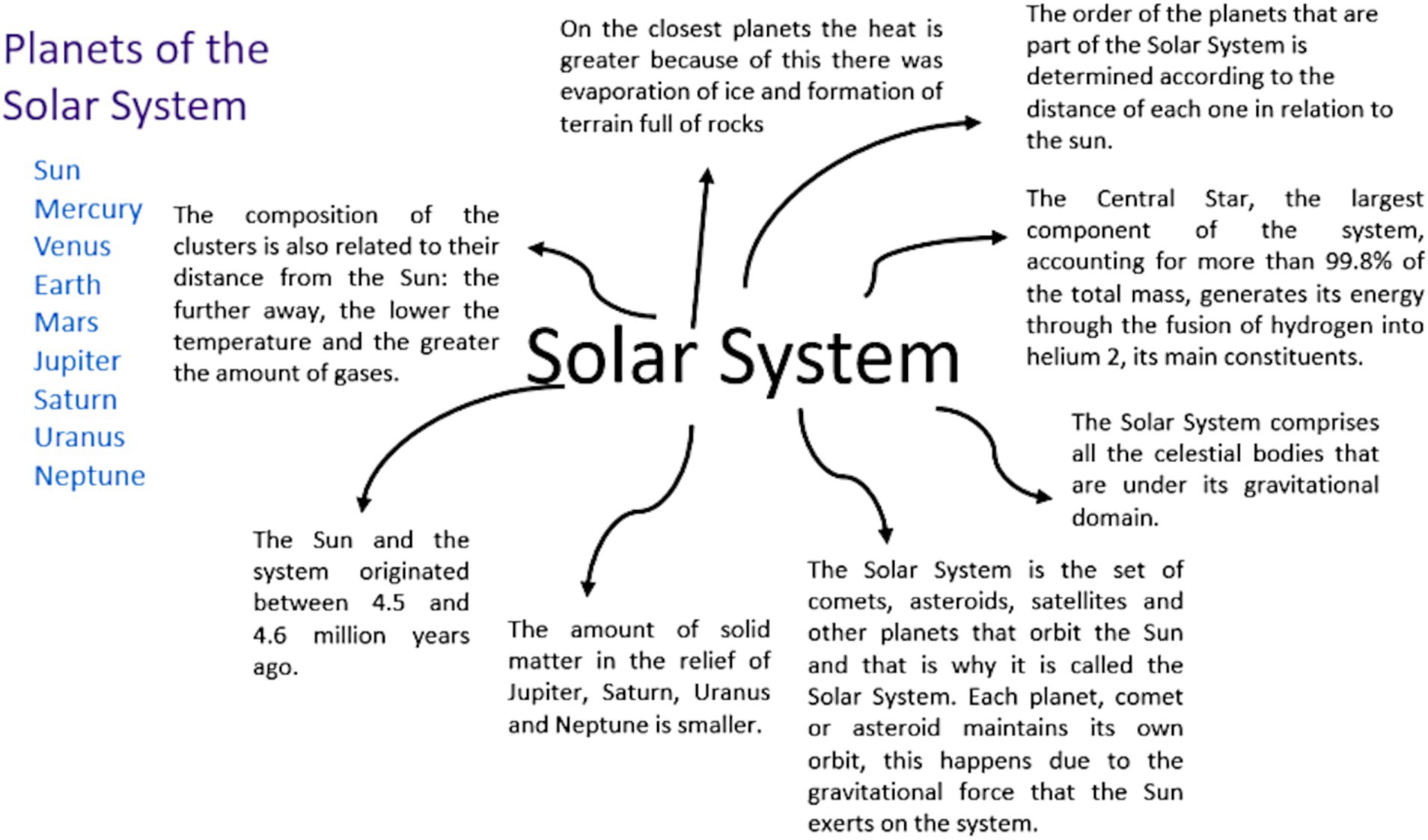

• Mind Map Creation: Students individually created mental maps of the solar system. This activity served as a cognitive organization and assessment tool, allowing them to visually represent the connections between concepts, such as linking gravity to orbital motion.

3.6 Data collection

Data collection took place during the first semester of 2023, specifically between March 10 and July 10, involving a group of 22 students (10 girls and 12 boys) in the 9th grade of an elementary private school in Araruna, located in the central-west region of Paraná, Brazil. The number of students participating in this qualitative research is considered sufficient to support the sample for the proposed objectives. Unlike the numerical representation predominant in quantitative research, the qualitative approach focuses on the participants’ ability to provide substantial information and meaning related to the topic. The validity of the sample, therefore, resides in the quality of individual contributions and their ability to lead to theoretical saturation of the data, where new information does not add significant insights to the understanding of the phenomenon.

The research corpus was composed using the following instruments:

• Questionnaires: These were designed to assess students’ prior knowledge and their understanding of key concepts related to the solar system. The questionnaire was developed based on the learning objectives and its content validity was reviewed by two experienced science education researchers (Cohen et al., 2018). The full instrument is available in Reinisz (2024).

• Mind maps: They were used to visualize students’ understanding and organization of knowledge (Petchenik, 1995). The evaluation of mind maps was guided by the criteria established by Batista and Gomes (2021), which emphasize the clarity, coherence, and depth of the connections made by students.

• Researcher’s field diary: This instrument was used to record observations, reflections, and interactions during the research process. This resource is essential in qualitative research, as it allows the researcher to document the context and nuances of the observed phenomena (Emerson et al., 2011).

The data analysis followed a descriptive qualitative approach, employing systematic procedures to ensure reliability and transparency. The unit of analysis was defined as the individual student’s productions and textual responses. The analytical process, guided by Creswell (2014), involved the following stages:

• Preparation and Familiarization: All data were organized and reviewed to understand the content.

• Inductive Coding: Inductive coding was applied for open-ended responses and field diary observations, allowing themes to emerge directly from the data without a pre-imposed framework.

• Deductive Coding Scheme for Mind Maps: The analysis of mind maps was guided by a deductive scheme based on the criteria of Batista and Gomes (2021), focusing on clarity, coherence, and depth of connections. Specifically, we looked for evidence of key concepts (“gravity,” “gaseous planet”), simple connections (“Sun → provides light”), and complex/integrative connections (“planet mass → gravitational force → orbit”).

• Theme Identification: Codes were subsequently grouped into broader themes that captured significant student perceptions and understanding patterns.

• Credibility Strategies: To ensure the trustworthiness of the analysis, multiple strategies were employed:

• Triangulation: Different data sources (questionnaires, mind maps, observations) were cross-referenced to corroborate findings.

• Researcher Conferencing: Two researchers discussed and refined Initial codes and themes until a consensus was reached.

• Audit Trail: The analytical decision-making process, from raw data to identifying final themes, was documented to provide transparency.

To illustrate the procedure, an example of the analysis of an open-ended response is provided: Raw Data: “At the planetarium, I understood that the force that keeps the Moon orbiting the Earth is the same one that keeps us on the ground.”

Code: Gravity as a universal force.

Theme: Conceptual integration of gravity.

3.7 Assessment

Assessment was continuous and formative, aligned with the proposal’s objectives. It was based on multiple instruments: is based on participation, the development and presentation of projects, mind maps, questionnaires, and all other documents produced by students during the teaching proposal, as shown in Figure 3. The focus was on evaluating the ability to integrate concepts and skills from the different areas of knowledge.

This holistic approach to assessment aligns with the principles of formative assessment, which emphasizes the ongoing learning process and the development of higher-order thinking skills (Black and Wiliam, 1998).

3.8 Ethical considerations

This study was conducted per the ethical guidelines for research with human subjects and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Technology - Paraná (UTFPR) opinion number 4.993.567. Before data collection, informed consent was obtained from the students’ parents/guardians and the school administration. Participants were clearly informed about the research objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. To ensure anonymity, all identifying information was removed from the collected data, and participants are referred to by non-identifiable codes (Student 1, Student 6) throughout the manuscript. The students’ images were blurred to hide their identification.

4 Results

This section presents the findings obtained from implementing the teaching proposal, organized systematically according to the primary data collection instruments: assessment results, analysis of student productions (models and mind maps), and content analysis of open-ended responses.

To address the research question regarding the influence of the integrated STEAM-MLT approach on student understanding (RQ1), student learning was evaluated through a combination of a post-intervention quiz, graded project presentations, and mind map analysis. A comparative study between the post-intervention quiz and the initial diagnostic questionnaire revealed a marked improvement in the class’s overall performance. Analysis of the Quizizz scores from the diagnostic and post-intervention phases showed a clear positive shift. The number of students achieving a ‘high understanding’ score (above 80%) increased from 3 (14% of the class) in the diagnostic to 14 (64% of the class) in the post-intervention assessment. Student outcomes were categorized into three levels based on a holistic analysis of all assessment instruments. A significant portion of students demonstrated an Advanced level of understanding, characterized by their ability to articulate complex connections between concepts such as gravity, orbital motion, and planetary characteristics. Most students achieved proficiency, accurately describing individual concepts and their fundamental interrelations. A smaller group of students was classified as Developing, showing solid recall of basic facts but facing challenges in integrating concepts across the different STEAM areas in a synthesized manner. This distribution indicates a positive shift towards more meaningful and integrated knowledge construction among most participants.

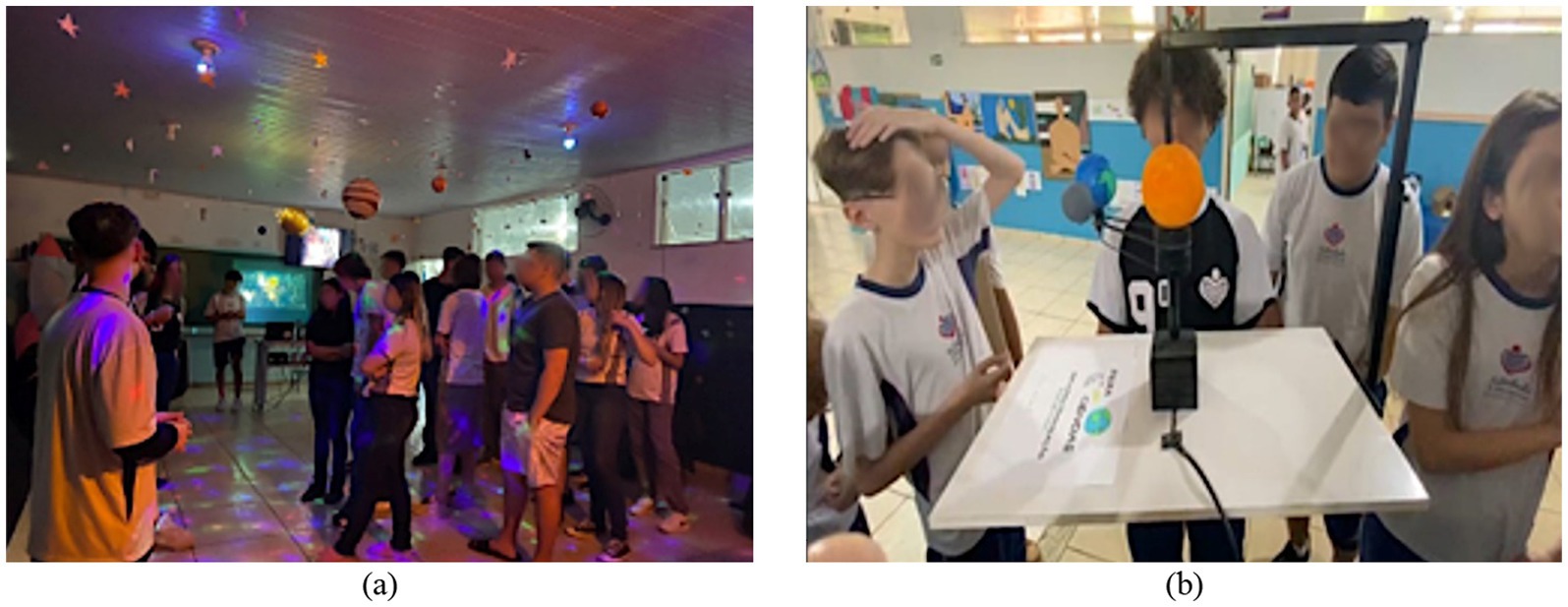

The analysis of the tangible outcomes from the hands-on activities provides evidence related to RQ1 and RQ2, concerning interdisciplinary integration and meaningful learning. A systematic review of the final projects and lapbooks revealed that 18 out of 22 groups (82%) successfully integrated concepts from at least three different STEAM areas in their final exhibition, providing concrete evidence of interdisciplinary application. The construction of the scaled solar system model required students to apply mathematical reasoning (scale and proportions) and engineering design principles, resulting in a functional representation that was later showcased at the school’s science fair (Figures 4a,b). The final collaborative project, the “Solar System Exhibition,” was the primary outcome of the integrative reconciliation phase. Students successfully created a prototype simulating planetary motions, effectively communicating the concept of orbits governed by gravitational force to the school community. Furthermore, the lapbooks and mental maps produced by students served as evidence of knowledge consolidation.

Figure 4. Student engagement and project outcomes. (a) Students presenting their work at the school science fair, demonstrating communication skills and engagement. (b) The functional prototype of the solar system built by students, showcasing the application of engineering and mathematical principles to model astronomical phenomena. Source: personal file (2024).

The mental maps, in particular, varied in complexity, with some demonstrating simple linear connections (Figure 5) and others showcasing a rich, non-linear structure with multiple branches integrating concepts like space–time curvature (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Mind map demonstrating initial conceptual integration. This mind map, created by Student 6, shows a foundational understanding with primary branches connecting key concepts, illustrating the successful initial organization of knowledge following the teaching sequence. Source: Student 6 (2024).

Figure 6. Mind map evidencing advanced integrative reconciliation. This complex mind map by Student 1, with multiple branches and connections (e.g., linking gravity to space–time curvature), provides strong evidence of meaningful learning and deep conceptual integration achieved through the STEAM-MLT approach. Source: Student 1 (2024).

In general, all the maps produced at the end of the implementation satisfactorily addressed the theme’s content. Some maps had a narrower scope, reinforcing the prior knowledge initially identified. In comparison, others demonstrated a broader scope, highlighting a direct connection between prior knowledge and the new concepts studied during the progressive differentiation process.

To gain insight into the perceived impacts on engagement and conceptual internalization (RQ3), a qualitative content analysis was performed on responses to open-ended questions, such as “What did I learn at the planetarium?” The coding process revealed emergent categories that reflect the internalization of key concepts. The analysis indicated that the most prevalent themes among student responses were “Gravity as an orbital force” and “Differentiation between rocky and gaseous planets,” which appeared consistently across most submissions. A substantial number of responses also referenced the “Mathematical scale of the solar system,” demonstrating an appreciation for quantitative aspects. Other notable, though less frequent, themes included “Relation between mass and gravitational force” and “Scientific models as representations,” which appeared in a meaningful subset of the answers.

The credibility of the findings is strengthened by the triangulation of data from different sources, which revealed converging evidence of student learning. A clear example is the understanding of gravity. This concept was not only frequently articulated in open-ended responses (Student 2’s explanation of mass and attraction) but was also structurally integrated into the more complex mind maps (Figure 6), which linked it to orbital motion. Quantitatively, this was reflected in the post-intervention quiz, where a significant increase in correct answers to questions about gravity was observed. Similarly, the field diary consistently noted high levels of engagement and collaborative problem-solving during the engineering and design phases, a finding corroborated by the high percentage of final projects (82%) that successfully synthesized concepts from multiple STEAM areas. This consistency across diverse data types, direct statements, cognitive organization, observed behavior, and quantitative metrics, provides robust, multi-faceted support for the effectiveness of the intervention.

5 Discussion

This study aimed to develop and evaluate an interdisciplinary teaching proposal for the solar system that integrates the STEAM approach with Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory (MLT). The discussion interprets the results within the context of existing literature, highlighting the novel contributions of this hybrid framework.

The significant improvement in assessment scores and the depth of connections observed in student mind maps suggest that the integration of MLT effectively addressed common weaknesses of STEAM initiatives. Previous research has cautioned that STEAM activities can sometimes prioritize engagement and product creation over deep conceptual understanding, potentially leading to superficial learning (Schweingruber et al., 2014; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro, 2019). Our proposal countered this by using MLT principles as a structural backbone. The advanced organization phase (planetarium visit, diagnostic activities) ensured new knowledge was anchored to relevant subsumers. The progressive differentiation phase was explicitly mapped onto the sequential exploration of each STEAM area, allowing for a gradual build-up of concepts. Finally, the integrative reconciliation phase was not left to chance but was engineered through the final exhibition project and mind mapping, which required students to synthesize knowledge. This structured approach differs from conventional STEAM by ensuring that the “A” for Arts and the “T” for Technology are not merely motivational add-ons but are integral to a cognitively sequenced learning process, a synergy suggested by Ferreira et al. (2022) but operationalized here in a detailed teaching proposal.

The content analysis of student responses, particularly the high frequency of codes like “Gravity as orbital force,” demonstrates that students moved beyond rote memorization to achieve a substantive, non-arbitrary integration of concepts. This aligns with Ausubel (2012) core premise that learning is meaningful when new ideas are related to existing cognitive structures. The STEAM approach provided the multifaceted experiences necessary to create these connections. For instance, building the physical model (Engineering) forced a practical engagement with mathematical scale (Mathematics), giving concrete meaning to the planetary characteristics learned in Science class. This finding reinforces the argument by Yakman (2008) that integrated knowledge is more readily internalized. However, our study extends this by showing that when these experiences are deliberately planned within an MLT framework, the resulting learning exhibits the characteristics of integrative reconciliation, as visually evidenced by the complex branches in mind maps like the one in Figure 6.

The positive outcomes, including high student engagement and the quality of the final projects, indicate that the proposed hybrid framework is a practical and effective model for astronomy education. It offers teachers a clear blueprint for designing interdisciplinary units that are both engaging and cognitively rigorous. In contrast to studies that apply STEAM or MLT in isolation (Maia et al., 2021; Silva Filho and Ferreira, 2022), this research provides a validated example of their integrated application. The main novelty of this discovery lies in giving a concrete pedagogical model that explicitly links the stages of a STEAM project to the cognitive processes of meaningful learning. For future research, we recommend exploring the application of this STEAM+MLT framework to other scientific topics and in different educational contexts.

6 Conclusion

The research demonstrated that 9th-grade elementary school students when exposed to a methodology integrating different areas of knowledge and emphasizing content significance, developed a deeper and more articulated understanding of astronomical concepts. They were able to solve problems similar to those studied during the implementation and gained a more interdisciplinary perspective supported by the STEAM approach. In short, the proposal developed in this study was innovative, practical, and applicable to the educational context analyzed.

The students’ mental maps analysis revealed significant improvement in their understanding of the solar system, indicating that the STEAM approach combined with MLT principles facilitates integrated and contextualized knowledge construction. The evaluation of the teaching proposal, based on results and student feedback, showed that the methodology sparked student interest and curiosity while fostering a collaborative and investigative learning environment. Experience reports indicate that interdisciplinary activities and advanced organizers significantly contributed to the internalization of astronomical concepts by the students.

This study reaffirms the importance of an educational approach that integrates different areas of knowledge and aligns with contemporary learning theories. The proposal enriches the school curriculum and prepares students for contemporary cognitive demands by promoting essential skills like critical thinking, logical reasoning, and scientific investigation.

In summary, based on MLT and the STEAM approach, the teaching proposal effectively addressed challenges in astronomy education, particularly in teaching the solar system. The integration of these frameworks led to meaningful and engaging learning, giving students a holistic view of the cosmos, and preparing them to be informed, aware citizens. Therefore, it is recommended that research and educational practices continue to explore and expand this approach, aiming for the ongoing improvement of astronomy education in elementary school.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MB: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Supervision, Project administration, Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Validation, Funding acquisition. IC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. TV: Resources, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. EG: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Project administration, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization. OS: Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization, Resources. OF: Validation, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. MF: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors express their gratitude to the following institutions: (1) Federal Technological University of Paraná (UTFPR); (2) University of Brasília; (3) Rodolpho Caniato Astronomical Center; (4) National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) -process 310465/2022-2; (5) Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes) -Funding Code 001; (6) Araucária Foundation (FA); (7) Secretariat of Science, Technology and Higher Education of Paraná (SETI) -PDI 346/2024; (8) Paraná Network for Research on Extreme Phenomena of the Universe (NAPI); and (9) Foundation for Research Support of the Federal District (FAPDF) -Grant and Acceptance Term 492/2022, process 00193-00002222/2022-24.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1683810/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

^The Planetarium is a space dedicated to teaching, disseminating, and popularizing astronomy, located in Campo Mourão, Paraná, Brazil. It features a 7-meter diameter dome with capacity for 40 seats and a Titan digital fulldome projector. @poloastronomico_rcaniato andhttps://www.poloastronomicorcaniato.com/.

References

Ausubel, D. P. (2003). Aquisição e retenção de conhecimentos: uma perspectiva cognitiva. v. 1. Lisbon: 334.

Ausubel, D. P. (2012). The acquisition and retention of knowledge: A cognitive view. New York, EUA: Springer Science & Business Media.

Batista, M. C., dos Santos, O. R., Canovas, D. P. D. S., and Pereira, R. F. (2022b). Um jogo de tabuleiro como recurso didático para o ensino de luz e cores no Ensino Médio. Rev. Professor Física 6, 55–64. doi: 10.26512/rpf.v6i2.42008

Batista, M. C., and Fusinato, P. A. (2015). A utilização da modelagem matemática como encaminhamento metodológico no ensino de Física. Rev. Ensino Ciências Matemática 6:2. doi: 10.26843/rencima.v6i2

Batista, M. C., and Gomes, E. C. (2021). “Diário de campo, gravação em áudio e vídeo e mapas mentais e conceituais” in Metodologia da Pesquisa em Educação e Ensino de Ciências. eds. C. A. O. M. Júnior and M. C. Batista (Maringá: Massoni), 130–136.

Batista, M. C., Santos, O. R. D., Matins, V. C., and Vieira, T. F. (2022a). Teaching seasons with a hands-on activity. Int. Astron. Astrophysics Res. J. 4:3.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

BRASIL Ministério da Educação (2018). Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: Ministério da Educação.

Brookfield, S. D., and Preskill, S. (2005). Discussion as a way of teaching: Tools and techniques for democratic classrooms. Boston, EUA: Jossey-Bass.

Chaves, A. L. F., Ferreira, R. L., and Ferreira, L. S. S. (2021). Contextualizando a Educação no Brasil, sua influência no processo histórico. Rev. Científ. Multidiscip. Núcleo Conhecimento 4, 141–154.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. London: Routledge doi: 10.4324/9781315456539.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., and Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ferreira, M., Couto, V. L. R., Silva Filho, O. L., Paulucci, L., and Monteiro, F. F. (2021a). Teaching astronomy: a didactic approach based on the theory of general relativity. Rev. Brasil. Ensino Física 43:157. doi: 10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2021-0157

Ferreira, L., de Andrade, V. C., Batista, M. C., and Langhi, R. (2024). Dos LEDs aos pulsares: um experimento interativo de baixo custo para o ensino de astronomia e astrofísica na escola. Cuadernos Educ.y Desarrollo 16:e6734. doi: 10.55905/cuadv16n13-011

Ferreira, M., de Araújo Nascimento, F. A., Campos, L. D. L. V., do Couto, R. V. L., and da Silva Filho, O. L. (2025). Simulação Computacional como Organização Avançada e Mediação Pedagógica do Efeito Fotoelétrico. Rev. Enseñanza Física 37, 67–81. doi: 10.55767/2451.6007.v37.n1.48953

Ferreira, M., Silva Filho, O. L., Batista, M. C., Arão Filho, A., Strapasson, A., and Santana, A. E. (2023a). Science fiction in the didactic transposition of the concept of entropy: Isaac Asimov’s last question. Rev. Brasil. Ensino Física 45:254. doi: 10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2023-0254

Ferreira, M., Silva Filho, O. L., Moreira, M. A., Franz, G. B., Portugal, K. O., and Nogueira, D. X. (2020). Potentially meaningful teaching unit on geometric optics supported by videos, apps and games for smartphones. Rev. Brasil. Ensino Física 42. doi: 10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2020-0057

Ferreira, M., Silva Filho, O. L., Nascimento, A. B. S., and Strapasson, A. B. (2023b). Time and cognitive development: from Vygotsky’s thinking to different notions of disability in the school environment. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10:768. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-02284-8

Ferreira, M., Silva, A. L. S., and Silva Filho, O. L. (2022). Meaningful learning theory and science teaching through research: interfaces from a narrative literature review. Rev. Brasil. Pesquisa Educ. Ciências 22:e41847. doi: 10.28976/1984-2686rbpec2022u12151241

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Comput. Entertain. 1:95. doi: 10.1145/950566.950595

Graça, A. R. T., Massoni, A. M., Dias, T. M. S., and Melo, G. J. (2020). STEAM: A engenharia integrada ao ensino de ciências. Maceió-AL: Anais do VII Congresso Nacional de Educação (Conedu).

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 16, 235–266. doi: 10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. J. Excell. Univ. Teach. 25:3.

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: FT Press.

Magron, A. Á., Batista, M. C., Schiavon, G. J., and dos Santos, O. R. (2022). Proposta para o ensino de astrofísica a partir da teoria da aprendizagem significativa. Rev. Física 6, 233–238. doi: 10.26512/rpf.v1i1.45955

Maia, D. L., de Carvalho, R. A., and Appelt, V. K. (2021). Abordagem STEAM na educação básica brasileira: uma revisão de literatura. Rev. Tecnol. Soc. 17:68. doi: 10.3895/rts.v17n49.13536

Martinez, S. L., and Stager, G. (2019). Invent to learn: Making, tinkering, and engineering in the classroom. 2nd Edn. Torrance, CA: Constructing Modern Knowledge Press.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Moreira, M. A., and Massoni, N. T. (2015). Interfaces entre teorias de aprendizagem e ensino de ciências/física. Porto Alegre: Instituto de Física/UFRGS.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Perignat, E., and Katz-Buonincontro, J. (2019). STEAM in practice and research: an integrative literature review. Think. Skills Creat. 31, 31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018.10.002

Prensky, M. (2003). Digital game-based learning. Computers in entertainment (CIE). 1:1. doi: 10.1145/950566.950596

Pugliese, G. (2020). STEM Education – Um panorama e sua relação com a educação brasileira. Curríc Front. 20:1. doi: 10.35786/1645-1384.v20.n1.12

Reinisz, I. K. C. (2024). Estudo de uma proposta para o ensino do sistema solar nos anos finais do ensino fundamental a partir da teoria da aprendizagem significativa e da abordagem steam (Master's thesis). Campo Mourão, PR: Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná.

Schweingruber, H., Pearson, G., and Honey, M. (2014). STEM integration in K-12 education: Status, prospects, and an agenda for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Silva Filho, O. L., and Ferreira, M. (2022). Theoretical model for surveying and organizing subsumers within the scope of meaningful learning. Rev. Brasil. Ensino Física 44:339. doi: 10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2021-0339

Sitko, C. M., Batista, M. C., and dos Santos, O. R. (2023). Constelações 3D: proposta didática na formação continuada de professores. Física Escola 21:42. doi: 10.59727/fne.v21i1.42

Sousa, R. R. A. (2022). História da Metodologia STEAM. Revista Científica Campus XIX 3:4. doi: 10.52302/renove.vol3.n4.a19937

Vieira, T. F., da Fonseca, M. O., Buffon, A. D., Batista, M. C., and dos Santos, O. R. (2024). A educação em astronomia no livro didático de física do ensino médico no estado do Paraná: insurreições necessárias. Ciências Ideias 1:15. doi: 10.22407/2176-1477/2024.v15.2690

Vilaça, J., Langhi, R., and Nardi, R. (2013). Planetários enquanto espaços formais/não-formais de ensino, pesquisa e formação de professores. Encontro Nacional Pesquisa Educ. Ciências 14, 209–224. doi: 10.5007/1982-5153.2021.e75620

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Wang, T. H. (2015). Web-based quiz-game-like formative assessment: development and evaluation. Comput. Educ. 51, 1247–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2007.11.011

Keywords: astronomy education, elementary school, interdisciplinarity, meaningful learning theory, STEAM approach, solar system

Citation: Batista MC, Cintra Reinisz IK, Vieira TF, Gomes EC, Santos OR, Silva Filho OL and Ferreira M (2025) A STEAM approach supported by the meaningful learning theory to teach the solar system in lower secondary education (9th grade). Front. Educ. 10:1683810. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683810

Edited by:

Cecília Costa, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, PortugalReviewed by:

Matteo Tuveri, University of Cagliari, ItalyAinun Mardia, Sriwijaya University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Batista, Cintra Reinisz, Vieira, Gomes, Santos, Silva Filho and Ferreira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oscar Rodrigues dos Santos, b3NjYXJzYW50b3NAdXRmcHIuZWR1LmJy

Michel Corci Batista

Michel Corci Batista Ivana Kelly Cintra Reinisz2

Ivana Kelly Cintra Reinisz2 Ederson Carlos Gomes

Ederson Carlos Gomes Oscar Rodrigues dos Santos

Oscar Rodrigues dos Santos Olavo Leopoldino da Silva Filho

Olavo Leopoldino da Silva Filho Marcello Ferreira

Marcello Ferreira