- Department of Education Management, Policy and Comparative Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Background: Multigrade classrooms in the Foundation Phase present unique teaching and behavioural management challenges. These settings require innovative and consistent classroom management strategies to ensure effective learning.

Objective: This study explored how Foundation Phase teachers perceive and manage multigrade classrooms.

Methods: The study adopted an interpretive paradigm and employed a qualitative approach within a multiple case study design. It was grounded in Self-Efficacy Theory and the Alternatives to Establishing a Conducive Learning Environment (AECLE) model. Purposive sampling was used to select three schools, and five Foundation Phase teachers teaching in multigrade settings. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews and document analysis. Thematic analysis was used to interpret the data.

Results: The findings revealed that teachers perceive multigrade classroom management as complex and demanding, primarily due to limited training, insufficient policy guidelines, and behavioural challenges associated with learner diversity. These conditions undermined teachers’ self-efficacy. Nonetheless, teachers applied adaptive strategies, such as rule-setting, modelling, reinforcement, learner movement, relationship-building, and grade splitting, that reflected emerging situational efficacy. However, inconsistent implementation of these strategies highlighted the absence of systematic professional development and institutional support tailored to multigrade contexts.

Conclusion: The study concludes that improving multigrade classroom management requires professional development that directly addresses the unique pedagogical and behavioural challenges of teaching across grades. Strengthening teacher efficacy through structured, context-specific training could foster consistent application of management strategies and reduce reliance on fragmented, individual adaptations.

Introduction and background

One of the fundamental human needs is acquiring skills, primarily attained through education. However, the provision and quality of education are often shaped by contextual realities. Recognising this, Sustainable Development Goal 4 calls on countries to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all, a vision further supported by scholars such as Kanyopa and Chibaya (2025), who advocate for policy reforms to meet this mandate. Whilst constitutional frameworks may enshrine the right to education, evolving circumstances and contextual challenges raise critical questions about whether systems like multigrade teaching truly uphold the promise of quality education for all.

As defined by Msimanga (2020) multigrade teaching is a pedagogical approach in which a single teacher instructs learners from multiple grade levels within one classroom. These learners differ in age, academic ability, and developmental stage, distinguishing multigrade classrooms from monograde settings (Little, 2005 cited in Karaçoban and Karakuş, 2022). Scholars such as Naparan et al. (2021) and Taole (2024) explain that multigrade teaching is often driven by low learner enrolment and demographic challenges, particularly in rural and geographically isolated communities.

The Foundation Phase (Grade R-3), which includes the first years of formal schooling, is critical for cognitive, emotional, and social development (Tastan and Bezci, 2023). Quality education at this early stage equips learners with the foundational skills to navigate an increasingly complex world. However, when multigrade teaching is implemented without adequate support, it can compromise learning outcomes. Urma and Callo (2023) highlight that the structural complexities of multigrade classrooms, ranging from diverse learning needs to competing instructional demands, often hinder effective teaching and learning.

In South Africa, multigrade teaching is not a pedagogical innovation but a systemic necessity. It is particularly prevalent in provinces such as the Eastern Cape, Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, and Northwest, where schools operate under limited resources, sparse learner populations, and teacher shortages (Msimanga, 2020). Globally, multigrade teaching is practised in countries like Philippines (Bongala et al., 2020; Recla and Potane, 2023), Malaysia (Idris, 2020), Cyprus (Erden, 2020), Pakistan (Qayoom et al., 2024) and Turkey (Kartal and Demir, 2022). For instance, Malaysia mandates multigrade instruction in government schools with fewer than 30 learners, using standardised procedures (Idris, 2020). Despite its international relevance, multigrade teaching remains under-researched, especially in the Foundation Phase in South Africa.

Historically disadvantaged rural schools in South Africa continue to face systemic challenges such as underqualified teachers, poor infrastructure, and limited professional support (du Plessis and Mestry, 2019). Families in these communities often experience severe socio-economic constraints that limit their ability to support children’s education (Mulford & Johns, 2004 cited in du Plessis and Mestry, 2019). Although policies like the South African Schools Act (SASA) sought to address historical inequalities, progress has been slow, with the legacy of apartheid still shaping educational outcomes (Kanyopa and Makgalwa, 2024). Consequently, multigrade classrooms remain prevalent in rural areas, exposing learners to unequal educational conditions that perpetuate cycles of poverty and marginalisation.

Classroom management in such multigrade settings is particularly demanding. Teachers must address multiple curricula, learner behaviours, and instructional needs simultaneously, which can lead to fragmented attention, disengagement, and instructional breakdowns (Erden, 2020; Kartal and Demir, 2022). These pressures contribute directly to teacher stress, exhaustion, and burnout (Naparan and Alinsug, 2021; Shank and Santiague, 2022). Without effective management systems, learning environments are more likely to suffer from disruptive behaviours Letuma (2024b), low achievement, and reduced teacher satisfaction (Clement, 2010 cited in Shank and Santiague, 2022; Bennett, 2020; Setyaningsih and Suchyadi, 2021).

Prior studies confirm that multigrade teaching is widely perceived as isolating and uncertain (Mpahla and Makena, 2021), that teachers face barriers such as inadequate ICT infrastructure, limited training, and lack of support from principals (Taole, 2024), and that principals themselves often lack induction training to guide leadership in rural multigrade schools (Taole, 2024). Moreover, teachers are burdened by competing responsibilities, balancing individual learner attention, supervision, and administrative duties, whilst struggling with overcrowded classes and insufficient support (Tredoux, 2020). These studies document significant challenges but stop short of exploring how teachers themselves navigate and manage these difficulties in practise.

Therefore, this study addresses a critical gap by exploring Foundation Phase teachers’ lived experiences of managing multigrade classrooms. By focusing on their strategies and perceptions, it generates context-sensitive insights to inform policy, professional development, and support mechanisms tailored to the realities of rural multigrade education (du Plessis and Mestry, 2019).

The following research questions guide this study:

• How do Foundation Phase teachers perceive the management of a multigrade classroom?

• How do Foundation Phase teachers manage multigrade classrooms?

Literature review

Nature of behaviour in children

Children’s behaviour is complex, shaped by psychological, developmental, and environmental factors. Whether learners act voluntarily or are influenced by internal and external pressures, questions of agency remain central to how behaviour is interpreted and addressed (Sarah, 2021). Within classrooms, Bennett (2020) categorises behaviour into three types: uncontrollable behaviours (e.g., neurological conditions such as Tourette syndrome), behaviours that become challenging through ingrained habits (e.g., yelling for attention), and voluntarily chosen behaviours (e.g., displaying or avoiding tasks). Recognising these distinctions helps teachers avoid misjudging learners and ensures that expectations and supports are appropriate. Whilst learners can exercise responsibility for their actions, the degree of their agency is not uniform. Teachers, therefore, need to interpret behaviour with sensitivity to the limits of learners’ control, balancing accountability with support.

Proactive and preventive management strategies

According to Paramita et al. (2020), behaviour management strategies fall into two categories: proactive and reactive. Reactive strategies respond to misbehaviour after it occurs, focusing on correction, whilst proactive strategies aim to prevent disruptions by encouraging positive conduct from the outset. Hepburn and Beamish (2020) note that proactive practises emphasise teaching and reinforcing appropriate behaviour.

In multigrade classrooms, where teachers must simultaneously manage diverse age groups and curricula, proactive approaches are especially valuable. Preventing problems before they arise reduces divided attention and helps maintain order. A core proactive strategy is the establishment of classroom rules, which provide a framework for acceptable behaviour and shared values (Sarah, 2021; Aelterman et al., 2019). For rules to be effective, they must be clearly communicated, positively phrased, limited in number for easy recall, and consistently applied with fairness and respect (Alter and Haydon, 2017; Kaya, 2012; Zoromski et al., 2021).

Equally important is the cultivation of strong teacher–learner relationships. Studies show that positive connections enhance engagement and reduce behavioural problems (Bosman et al., 2018; Ettekal and Shi, 2020; Gregory et al., 2017). In multigrade settings, where learners of different developmental levels share one classroom, such relationships help foster cooperation and reduce disruptions by ensuring that all learners feel valued. Walker and Graham (2021) further highlight that teacher–learner relationships are dynamic systems, and in contexts of disadvantage, such as rural multigrade schools, emotional support plays a central role in sustaining classroom harmony. However, as Bennett (2020) cautions, relationships cannot replace structure; they must complement clear rules and boundaries to ensure consistency and fairness in managing diverse behaviours.

The teacher’s role in the classroom

Bicard (2000) argues that whilst rules establish boundaries and expectations, they are less effective than the teacher’s consistent actions. Through continuous modelling and reinforcement, teachers create conditions for praise, engagement, and success, showing that effective classrooms are deliberately cultivated rather than accidental (Bennett, 2020). This underscores the central role of teachers in classroom management, especially in multigrade settings, where diverse learner needs require intentional and strategic approaches.

In such contexts, teachers function not only as educators but also as behavioural architects, balancing their responsibility to both educate and protect. As Bennett (2020) notes, behaviour management is not innate but must be developed through training. Yet many teachers continue to feel underprepared, particularly for multigrade classrooms, due to gaps in pre-service and in-service programmes that seldom address their specific realities (Erden, 2020; Msimanga, 2020; Mpahla and Makena, 2021). Recent evidence confirms that limited preparation leaves teachers reliant on improvisation, which often results in inconsistent practises and weakened behavioural expectations (Tredoux, 2020). By contrast, effective management requires clear planning, structured routines, and proactive strategies to prevent disruptions, combined with reactive responses that reinforce learning and maintain respect (Letuma, 2024a; Bennett, 2020).

Challenges of managing multigrade classrooms

Structural and systemic challenges

Though often necessary in rural and geographically isolated contexts, multigrade teaching presents multifaceted pedagogical and structural challenges. International research consistently shows that teachers in such settings, whether in Asia, Europe, or Africa, often experience inadequate pre-service preparation, rigid curricula, and minimal institutional support (Erden, 2020; Idris, 2020; Kartal and Demir, 2022; Qayoom et al., 2024; Recla and Potane, 2023). Similar concerns arise in sub-Saharan Africa, including Uganda, Zambia, and South Africa (Kivunja, 2014; Mpahla and Makena, 2021; Taole, 2024; Tredoux, 2020), where multigrade teaching is frequently a necessity driven by low enrolment and vast geographic dispersion (Bongala et al., 2020; Naparan and Alinsug, 2021).

In South Africa, education policy, curriculum development, and teacher training have historically prioritised mono-grade classrooms, creating a structural mismatch between policy and practise (Mpahla and Makena, 2021). Teachers are compelled to adapt mono-grade curricula for mixed-ability groups without adequate guidance, adding to the workload of lesson planning, content delivery, and assessment (Tredoux, 2020; Taole, 2024). These systemic pressures extend directly into behaviour management: when teachers juggle multiple developmental levels without differentiated strategies, learners may not share the same understanding of behavioural norms. This variation in readiness often manifests as disruptions, requiring teachers to teach and reinforce behaviour as deliberately as academic content. Thus, behaviour management in multigrade classrooms is shaped not only by learner diversity but also by systemic gaps in policy and training.

Resource constraints and environmental barriers

In addition to systemic policy gaps, resource limitations remain a critical challenge for multigrade teaching in rural and underserved areas in South Africa (Mpahla and Makena, 2021; Taole, 2024). According to Mpahla and Makena (2021), the Department of Education’s commitment to enhancing the professional skills of multigrade teachers remains largely theoretical. Although Department of Basic Education (DBE) guideline, such as the Multi-grade Strategy and Basic Education Sector Plan: Strengthening the Provision of Quality Teaching and Learning in Multi-Grade Schools advocate for the development of teachers’ capacity to design instructional plans tailored to the unique needs of multigrade classrooms, the reality on the ground tells a different storey (Mpahla and Makena, 2021). The existing curriculum is designed primarily for monograde teaching, requiring multigrade teachers to go the extra mile to adapt it. However, such efforts do not necessarily translate into effective teaching and learning, as the structural and contextual challenges in multigrade settings often hinder the delivery of quality education. Teachers frequently operate in classrooms that lack adequate textbooks, print-rich environments, and basic teaching aids, which hampers curriculum implementation and learning engagement (Recla and Potane, 2023; Tredoux, 2020). Infrastructure issues, such as overcrowded classrooms, insufficient sanitation, and deteriorating buildings, further strain teacher capacity and affect learner concentration (Taole, 2024).

Compounding these difficulties is the limited access to ongoing professional development and peer support, contributing to teacher fatigue and burnout (Egeberg et al., 2020). Educators often feel isolated and underprepared to manage classrooms that require constant differentiation and behavioural support. As a result, classroom management in multigrade contexts becomes an act of ongoing creation and maintenance. Like juggling, it requires continuous effort, adjustment, and resilience. Teachers must maintain routines, respond constructively to shifts in learner behaviour, and prevent the deterioration of positive classroom dynamics. These demands call for a reconceptualisation of classroom management not as a finite goal but as a continuous, adaptive process embedded in the structural and environmental realities of multigrade schooling.

Theoretical framework

This study was grounded in Albert Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory, which was complemented by the Alternatives to Establishing a Conducive Learning Environment (AECLE) model proposed by Letuma (2023, 2024a). These two frameworks were deliberately paired to provide a psychological and a practical lens for understanding how Foundation Phase teachers manage multigrade classrooms. Whilst Self-Efficacy Theory explains how teachers’ beliefs in their abilities shape their classroom management behaviours, the AECLE model offers structured, context-specific strategies to implement those behaviours effectively.

According to Bandura (1977), self-efficacy comprises four key components: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological states. Mastery Experiences refer to personal successes achieved through direct engagement with a task. Their confidence increases when teachers successfully manage disruptive behaviour or implement effective routines. Repeated success strengthens their belief in their capacity to handle future challenges (Bandura and Adams, 1977).

Vicarious Experiences occur when individuals observe others, especially peers, successfully performing a task. For teachers, watching a colleague manage a multigrade class effectively can inspire belief in their abilities. The closer the model is to the observer, the stronger the impact (Bandura and Adams, 1977).

Verbal Persuasion involves encouragement and constructive feedback from credible figures such as principals, mentors, or colleagues. When teachers are told they are capable or praised for their efforts, their belief in their ability grows. However, the persuasion must be realistic to be effective.

Physiological emotional states refer to the teachers’ interpretation of their emotional and physical state, such as anxiety or calmness, as indicators of capabilities. High stress can lower efficacy if interpreted as inability, whilst emotional calmness can signal readiness. Effective coping strategies help teachers regulate these states and perform better.

The AECLE model consists of six interlinked components: professional development, determining expectations, setting rules, communicating expectations, modelling behaviour, and reinforcement (Letuma, 2023, 2024a).

Professional development (core component)

At the centre of the model is professional development, facilitated externally when needed, to strengthen teachers’ capacity to implement the steps. School management is responsible for initiating this support (Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2022).

Determining expectations and setting rules

Using tools such as incident books, SA-SAMS data, and parent–school communication records, teachers identify common behavioural issues and formulate clear, consistent rules and expectations tailored to their school’s context. This teacher-led process ensures a structure that supports teaching and learning.

Communicating expectations

Teachers explain the established rules and expectations to learners, including the rationale and consequences, to ensure clarity and shared understanding.

Modelling desired behaviour

Teachers explicitly teach and demonstrate expected behaviours, considering developmental needs, so that learners see practical examples of appropriate conduct.

Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is consistently applied, with teachers acknowledging desirable behaviours such as participation and compliance to create a supportive climate focused on encouragement rather than punishment.

Applying consequences

When disruptive behaviour persists, teachers enforce appropriate disciplinary measures aligned with the school’s code of conduct, ensuring that behavioural standards are upheld.

Pairing self-efficacy theory with the AECLE model allowed this study to capture both the internal drivers of teacher behaviour and the external systems required to support it.

Materials and methods

Paradigm and approach

This study was grounded in the interpretive research paradigm, which prioritises comprehending human experiences within their social and contextual settings. This framework employed a qualitative approach to provide a comprehensive examination of Foundation Phase teachers’ experiences in managing multigrade classes. Qualitative research is especially suitable for exploring phenomena in natural environments, emphasising depth and contextual understanding rather than generalizability (Rubin, 2021).

Design

A multiple case study design was adopted. As defined by Strumińska-Kutra and Koładkiewicz (2018), a multiple case study involves investigating several bounded cases to understand a phenomenon within its real-life context. This approach offers the advantage of enabling cross-case comparisons whilst preserving the uniqueness of each case. It allows researchers to capture the complexity of participants’ lived experiences and the meanings they assign to their practises. In this study, the multiple case study design was particularly relevant, as it facilitated an in-depth understanding of how teachers in different school contexts navigate the pedagogical and managerial challenges inherent in multigrade classrooms.

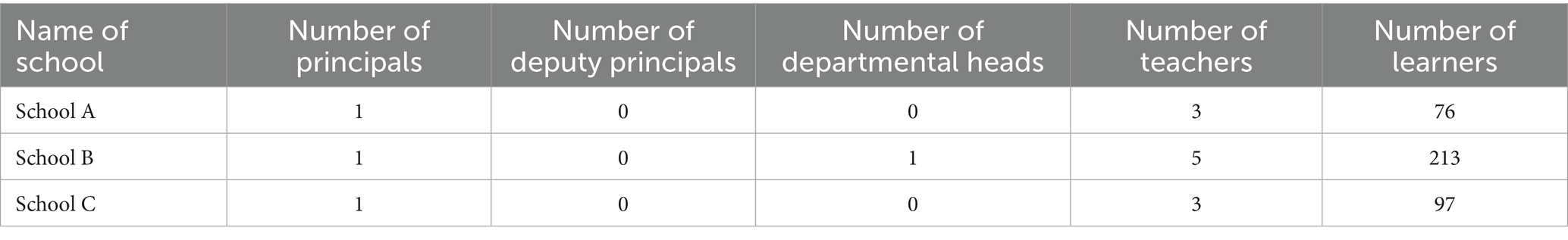

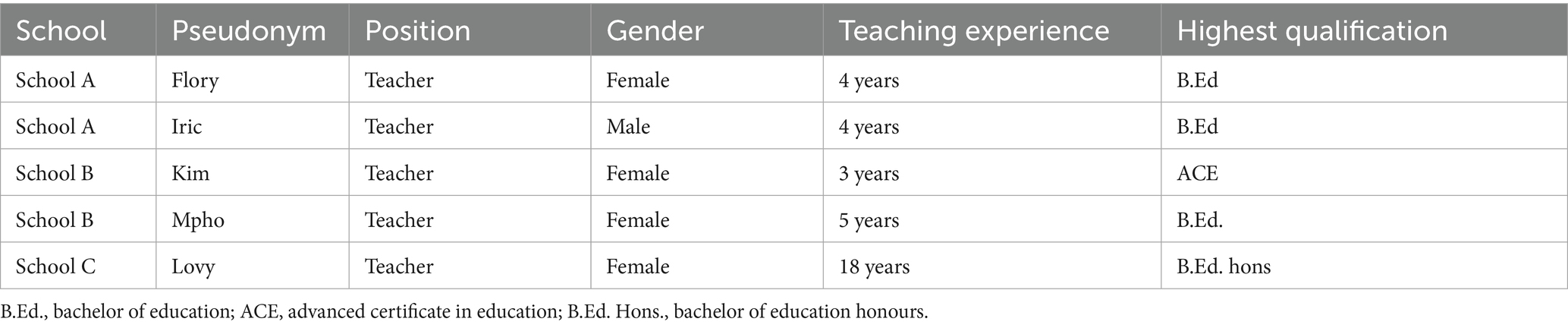

Sampling

The research sites and participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure the inclusion of specific characteristics likely to yield rich and relevant data. A total of five teachers participated. The primary criterion for selection was schools where multigrade teaching is implemented at the Foundation Phase level, as well as teachers who are exclusively responsible for such classes. The selected schools are in the Alfred Nzo District of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, and are classified as Quintile 1 schools. According to the national quintile ranking system, these schools fall within the lowest category and are characterised by serving some of the most impoverished communities in the country.

Tables 1, 2 below represent the background data of the research sites and participants.

Data collection and analysis

Data for this study was collected through semi-structured interviews with five Foundation Phase teachers working in multigrade classrooms. Two participants were selected from each of two schools, whilst one participant was drawn from a third school. In addition to interviews, relevant documents, specifically classroom rules and records of professional development activities from the past 2 years, were requested from each school for analysis. Document analysis served as a second method of data generation, providing an additional source of evidence to supplement and cross-check interview data. This triangulation not only strengthened the credibility of the findings but also offered contextual insights into how teachers’ reported practises aligned with documented school policies and professional learning activities.

The data was analysed using thematic analysis, guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach. The following steps were followed: First, data familiarisation involved reading transcripts and documents multiple times to gain a thorough understanding. Second, initial codes were generated by systematically identifying significant features across the dataset. Third, related codes were grouped to search for potential subthemes and overarching themes. In the fourth step, these themes were reviewed and refined to ensure alignment with the data. Fifth, themes were defined and clearly named to reflect their core meanings. Lastly, the final report was produced using illustrative extracts to support the findings. This process ensured a rigorous and credible interpretation of both interview and document data. This analytical process ensured that both interview and document data were systematically explored, allowing for rich insights into teachers’ experiences and practises in managing multigrade classrooms.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct research was sought from the University of Free State ethics committee and the Eastern Cape Department of Education. Informed consent was sought, and the nature of the study was clearly explained to the participants. The ethical approval number for the study is UFS-HSD2023/1289.

Findings

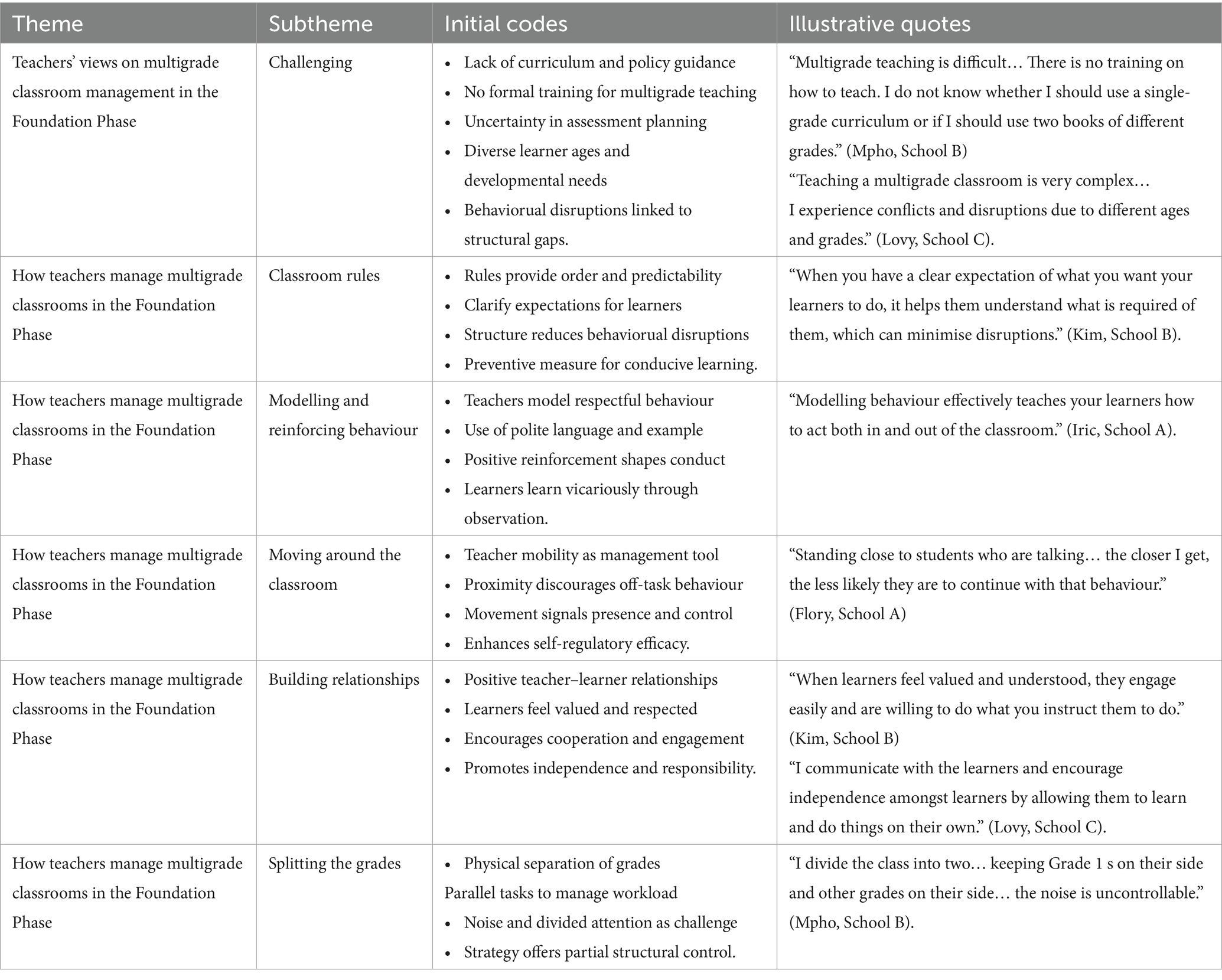

The data revealed the following major themes regarding the teachers’ views on multigrade classroom management and classroom management of multigrade classrooms in the foundation phase (Table 3).

Theme 1: teachers’ views on multigrade classroom management in the foundation phase

Teachers expressed strong dissatisfaction with multigrade classroom management, citing difficulties in curriculum organisation, assessment, and behavioural control. A key concern was the absence of clear guidelines from the Department of Education, leaving teachers uncertain about how to plan lessons, assess learners, or align with policy. As Mpho (School B) explained:

Multigrade teaching is difficult… There is no training on how to teach. I do not know whether I should use a single-grade curriculum or if I should use two books of different grades.

Beyond curriculum and policy gaps, teachers emphasised the daily realities of managing diverse learners. Lovy (School C) vividly described this challenge:

Teaching a multigrade classroom is very complex… I experience conflicts and disruptions due to different ages and grades. It is not easy, more especially in the Foundation Phase, because I’m dealing with learners who still need individualised attention; some cannot write, read, or count.

This highlights how behavioural management pressures intersect with developmental needs in early schooling. The accounts reveal not only systemic gaps in policy and training but also how such conditions undermine teachers’ self-efficacy. The lack of official guidance weakens teachers’ mastery experiences, leaving them doubtful about their capacity to effectively teach across grades. Unclear procedures also limit opportunities for vicarious learning (e.g., learning from structured models or exemplars), which Bandura identifies as critical for developing efficacy. From the perspective of the AECLE model, the absence of curriculum and policy support constrains teachers’ ability to implement structural alternatives that create a conducive learning environment. Instead of focusing on instructional innovation, they are preoccupied with confusion, workload, and classroom disruptions, which erode both confidence and effectiveness.

Theme 2: how teachers manage multigrade classrooms in the foundation phase

Teachers described several strategies for managing multigrade classrooms. Five subthemes emerged: establishing classroom rules, modelling and reinforcing behaviour, moving around the classroom, building relationships, and splitting the grades. These strategies reflect teachers’ ongoing efforts to balance instructional demands with behaviour management, often relying on practical, adaptive methods rather than formal guidance.

Subtheme 1: classroom rules

Teachers emphasised that rules created order and predictability, helping learners understand expectations and minimise disruptions. As Kim (School B) explained:

When you have a clear expectation of what you want your learners to do, it helps them understand what is required of them, which can minimise disruptions.

Rules provided teachers with a sense of mastery experience, reinforcing their confidence in managing behaviour. In the AECLE model, rules represent a preventive alternative, laying structural foundations for a conducive learning environment by clarifying boundaries and promoting cooperation.

Subtheme 2: modelling and reinforcing behaviour

Participants also relied on modelling and positive reinforcement to shape behaviour. By demonstrating polite language and respectful interaction, teachers guided learners towards desirable behaviours. As Iric (School A) noted:

Modelling behaviour effectively teaches your learners how to act both in and out of the classroom.

This approach reflects vicarious learning in Self-Efficacy Theory, where learners observe and imitate competent behaviour, thereby reducing misbehaviour. Within the AECLE framework, modelling and reinforcement operate as relational alternatives, fostering environments where learners internalise norms through example rather than punishment.

Subtheme 3: moving around the classroom

Teachers highlighted mobility as a subtle but effective technique to manage behaviour. Proximity discouraged off-task activity and signalled teacher presence. Flory (School A) remarked:

Standing close to students who are talking… the closer I get, the less likely they are to continue with that behaviour.

This strategy enhanced teachers’ perception of control, strengthening their self-regulatory efficacy, the belief in their capacity to sustain discipline without confrontation. In the AECLE model, movement is a monitoring alternative, allowing continuous oversight and quick intervention to maintain focus.

Subtheme 4: building relationships

Teachers stressed that fostering positive relationships reduced conflict and encouraged cooperation. Kim (School B) explained:

When learners feel valued and understood, they engage easily and are willing to do what you instruct them to do.

Similarly, Lovy (School C) encouraged independence through regular communication and interaction. She shared:

I communicate with the learners and encourage independence amongst learners by allowing them to learn and do things on their own.

Such relationships nurtured teachers’ social persuasion efficacy, as positive learner responses reinforced their belief in their own effectiveness. In the AECLE model, relationship-building is a relational alternative, cultivating mutual respect and trust that form the emotional foundation for a conducive classroom climate.

Subtheme 5: splitting the grades

Some teachers separated learners by grade level to manage competing demands, though this strategy often presented difficulties with noise and divided attention. As Mpho (School B) explained:

I divide the class into two… keeping Grade 1s on their side and other grades on their side… the noise is uncontrollable.

Whilst splitting grades helped teachers cope with workload, it often undermined their self-efficacy by reinforcing feelings of partial control and persistent struggle. From the AECLE perspective, this represents a structural alternative, yet one that is limited in effectiveness given the dynamic realities of multigrade classrooms.

The findings suggest that no single strategy guarantees effective classroom management in multigrade contexts. Instead, teachers combine preventive (rules), relational (relationships, modelling), monitoring (movement), and structural (splitting grades) alternatives. This aligns with the AECLE model’s emphasis on diverse strategies for establishing a conducive environment. However, the variability in success highlights the fragile nature of teachers’ self-efficacy, which depends heavily on contextual challenges and the responsiveness of learners.

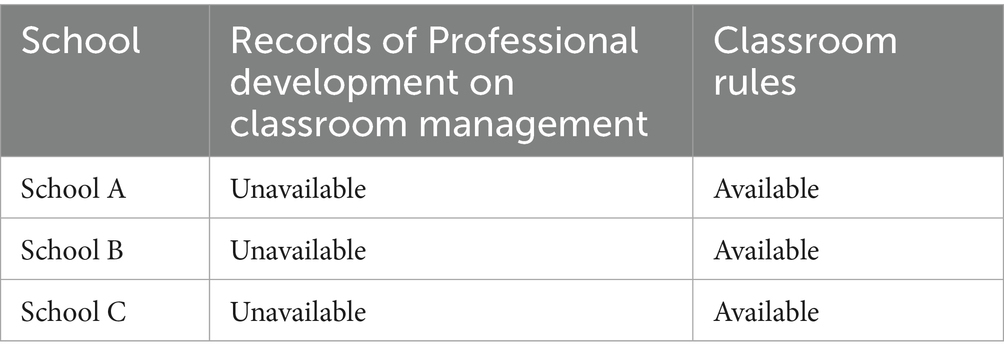

Document analysis

Table 4 below provides the details of the document analysis per school and their availability.

Records of professional development on classroom management

During data collection, no evidence was found of professional development initiatives specifically targeting classroom management in any of the three schools. The analysis of these documents aimed to identify whether topics related to classroom management were covered and how frequently such workshops were conducted to support teachers in managing their classrooms.

Classroom rules

Document analysis revealed that all schools had classroom rules visibly displayed in their classrooms. In School A, the rules in the Foundation Phase were written exclusively in isiXhosa, aligning with the school’s use of isiXhosa as the medium of instruction at that level. School B presented its rules solely in English, whereas School C displayed rules in both English and isiXhosa. The purpose of requesting and analysing these classroom rules was to examine the language used, the number of rules, and their intended function.

The differences in language choice carried important implications. Where rules were displayed only in English (School B), younger learners with limited English proficiency may have struggled to fully grasp behavioural expectations. This could weaken compliance, increase disruptions, and, in turn, erode teachers’ confidence in their ability to manage the classroom effectively. Conversely, rules displayed in isiXhosa (School A) reflected cultural and linguistic alignment with learners’ everyday communication, which likely enhanced their comprehension and responsiveness. However, this also posed challenges for learners transitioning into higher grades where English becomes the primary language of learning and teaching, potentially creating discontinuities in rule-following practises.

School C’s bilingual approach offered a more inclusive model. By displaying rules in both isiXhosa and English, the school accommodated diverse learners and provided opportunities for language reinforcement whilst promoting clarity of expectations. From a theoretical standpoint, this dual-language strategy supported teachers’ self-efficacy by reducing misunderstandings and strengthening their sense of control over behaviour. Within the AECLE model, the use of home and instructional languages in tandem functions as a relational and structural alternative, ensuring that behavioural guidelines are not only visible but also accessible to all learners.

Image of classroom rules

School C: classroom sample

1. Everyone has the right to work to their potential.

2. Everyone has the right to voice their opinions in the right manner.

3. Everyone has the right to understand and respect the opinions of others.

4. Everyone has the right to treat others in the right manner.

5. Everyone has the right to ask for help and advice at the appropriate time and manner.

6. Everyone has the right to uphold the values of the school even when outside.

7. Everyone has the right to respect the decision made by the school.

8. All students must arrive prior to the official start time of 07:45.

9. Every absence from school requires a parent or guardian to provide an absentee note.

10. In the event that a student misses 3 days or more of class, a letter of justification ought to be provided.

11. Any absence from a formal assignment requires a letter of justification.

12. During school hours, no student may leave without the school’s consent and a letter from a parent or guardian asking for their child’s release.

School A: classroom sample

1. Keep your classroom tidy and orderly.

2. Pay attention to your teacher.

3. Be a good friend to others.

4. Be kind to others.

5. Avoid making others cry.

6. Avoid fighting in class.

7. Always remain silent unless the teacher gives you instructions to do so.

8. Please refrain from yelling.

9. Refrain from running around the classroom.

10. Raise your hand when you wish to speak.

11. Share resources and

12. Support one another.

School A: classroom sample

1. No stealing

2. No fighting

3. No bullying

4. No playing in class, and

5. Keep the classroom clean.

Discussion

Teachers’ views on multigrade classroom management in the Foundation Phase

The findings revealed that teachers perceive multigrade classroom management as highly challenging, largely due to inadequate curriculum guidance and the absence of clear policy directives. Participants noted that CAPS fails to address the complexities of teaching across multiple grades, reflecting the persistent policy–practise disconnect identified in South Africa (Mpahla and Makena, 2021). Like Kartal and Demir (2022), this study found that teachers entered the profession with little preparation for multigrade teaching and encountered minimal institutional support. However, this study adds nuance by showing how teachers’ uncertainty around lesson planning and assessment is not just procedural but directly undermines their self-efficacy, leaving them reliant on trial-and-error strategies (Bandura, 1977).

The lack of professional development reported in this study reinforces earlier work on systemic gaps in teacher support (Egeberg et al., 2020; Okeke and Akobi, 2024; Recla and Potane, 2023), yet our document analysis makes a novel contribution: none of the three schools studied had records of classroom management workshops. This absence confirms the AECLE model’s concern that without developmental structures, schools cannot build teacher competence or provide structural alternatives for a conducive learning environment.

Compounding these institutional barriers, participants highlighted the behavioural diversity of learners in the Foundation Phase, where wide variations in age, readiness, and developmental needs created daily classroom pressures. Whilst Bennett (2020) and Sarah (2021) stress that teachers must distinguish among uncontrollable, habitual, and voluntary behaviours, this study shows that teachers felt underprepared to apply such distinctions in practise. This points to a novel implication: professional development should not only address instructional methods but also help teachers make theory-informed judgements about behaviour in multigrade contexts.

How teachers manage multigrade classrooms in the Foundation Phase

Despite these constraints, teachers demonstrated adaptive strategies such as setting rules, modelling behaviour, reinforcing positive conduct, moving around the classroom, building relationships, and splitting grades. From a Self-Efficacy Theory perspective, these reflect emerging situational efficacy; teachers gained confidence through performance accomplishments even in the absence of formal preparation (Bandura, 1977). The AECLE model affirms that such strategies represent preventive, relational, monitoring, and structural alternatives, yet this study highlights a key gap: because they are applied inconsistently and without institutional backing, these practises remain fragmented rather than systematised.

Classroom rules

Previous studies emphasise the value of rules in guiding behaviour and legitimising teacher authority (Demir et al., 2023; Frazier and Sterling, 2005; Marder et al., 2023; Okeke et al., 2025). What this study adds is evidence of variation in both the number and phrasing of rules across schools, with some lists exceeding a dozen and others reduced to four, some phrased positively and others negatively. This inconsistency contrasts with recommendations for fewer, positively framed rules (Kaya, 2012; Alter and Haydon, 2017). From a Self-Efficacy Theory perspective, such variability suggests fragmented teacher confidence in developing effective behavioural guidelines. Within the AECLE model, it signals a breakdown in the “setting classroom rules” component, where consistent school-wide expectations are essential.

Whilst literature notes that learners sometimes resist rules through defiance (Aelterman et al., 2019), this study extends the insight by showing that even in the Foundation Phase, where peer pressure is less pronounced, learners’ non-compliance was reported as linked to inconsistent or unclear rule-setting by teachers. This underscores the need for autonomy-supportive, positively framed rules that both enhance learner understanding and strengthen teacher efficacy.

Modelling and reinforcing behaviour

Teachers reported that they modelled respectful behaviour and used positive reinforcement to manage conduct. This aligns with the findings of Okeke et al. (2025) and Bicard’s (2000) assertion that teacher actions are more powerful than written rules in shaping learner behaviour. These daily modelling practises form a core part of the AECLE model and proactive management strategies (Paramita et al., 2020), offering learners a lived demonstration of expected conduct.

Moving around the classroom

Teachers used movement and proximity to manage behavioural dynamics, a technique aligned with proactive management principles (Paramita et al., 2020). Through this strategy, teachers maintained control and reduced off-task behaviour. Within Self-Efficacy Theory, such methods contribute to situational mastery, building teachers’ belief in their capacity to influence learner behaviour through immediate and intentional action.

Building relationships

Positive teacher-learner relationships were identified as essential for classroom harmony. Juta and Van Wyk (2020) note that such relationships are key to behaviour management. However, as Bennett (2020) cautions, strong relationships should not replace structure. In the context of AECLE, relationship-building supports, but does not substitute, the other pillars of management, such as rules and routine. From a Self-Efficacy Theory viewpoint, the ability to foster trusting relationships may serve as a source of emotional confidence for teachers managing complex multigrade environments.

Splitting the grades

Splitting the class by grade level became a key instructional and management technique. This reflects Bicard’s (2000) notion that effective classrooms are deliberately planned rather than spontaneously managed. However, the need for improvisation here, such as multitasking between grade groups, further supports the conclusion that teachers operate without sufficient systemic support or guidance, echoing AECLE’s concern with uneven implementation.

Limitations

This study was limited to three Foundation Phase schools with multigrade classrooms, using a small sample of five teachers selected through purposive sampling. Whilst this allowed for rich, in-depth insights, the findings may not be generalisable to all multigrade contexts in South Africa. The study focused only on teacher perspectives, excluding the voices of learners, school management, and district officials. Additionally, data collection relied primarily on interviews and document analysis, without classroom observations that could have added behavioural context. The study also focused mainly on classroom management, without fully exploring instructional strategies or academic outcomes.

Recommendation for further studies

Future studies could expand to include a larger and more diverse sample of schools across different provinces to enhance the transferability of findings. Including learners’ perspectives may offer a more comprehensive view of how classroom management practises are received and perceived. Further research could also explore the role of school leadership and district support in shaping multigrade teaching conditions. Longitudinal studies might assess how professional development interventions impact teacher efficacy and classroom practise over time. Additionally, classroom observation-based studies could deepen understanding of how strategies like grade splitting or modelling are enacted in real-time. Finally, comparative studies between monograde and multigrade classrooms may reveal critical policy and practise gaps. This would strengthen systemic responses to multigrade education challenges.

Conclusion

This study explored how Foundation Phase teachers perceive and manage multigrade classrooms. The findings revealed that teachers experience multigrade classroom management as challenging, primarily due to limited training, insufficient policy guidance, and the behavioural complexities presented by learners at varying developmental stages. These conditions appear to contribute to low or uncertain self-efficacy, particularly in the absence of structured mastery experiences and formal professional development. Despite these obstacles, teachers employed various adaptive strategies, such as classroom rules, behavioural modelling, reinforcement, movement, relationship-building, and grade splitting, demonstrating emerging situational efficacy. However, the inconsistent application of these strategies, especially in rule-setting and behaviour reinforcement, highlights the gap left by the absence of professional development. This implies that teachers find it difficult to regularly apply classroom management techniques without institutional support and focused professional development. As a result, elements like behaviour reinforcement and rule-setting continue to be fragmented and reliant on the teacher, thereby compromising the development of harmonious and orderly multigrade classroom settings. Based on these insights, it is recommended that multigrade-specific classroom management training be integrated into ongoing professional development programmes to strengthen teacher efficacy and foster greater behavioural consistency across multigrade contexts. This study contributes to the body of knowledge by highlighting the possible intersection between teacher efficacy, institutional support, and practical classroom strategies in multigrade Foundation Phase settings, calling attention to the need for systemic responses to support educators in these complex environments.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, this study recommends the following:

• Integrating multigrade-specific classroom management training into ongoing professional development programmes. Teachers reported lacking formal preparation, possibly contributing to low self-efficacy and inconsistent application of strategies such as rule-setting and behaviour reinforcement.

• Standardised guidelines should be developed and adopted across schools to address the observed inconsistencies in classroom rules, ranging in number, phrasing, and format.

• The lack of institutional and leadership support also highlights the need for school management teams to actively organise internal training and mentorship for teachers in multigrade settings.

• Peer collaboration should be encouraged through communities of practise that allow teachers to share practical strategies like grade splitting and behavioural modelling.

• Curriculum policy documents, such as CAPS, should be reviewed to incorporate guidance specific to multigrade instruction, including assessment and planning adaptations. These recommendations aim to enhance teacher efficacy, promote consistent behavioural norms, and support effective multigrade classroom environments.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Free State ethics committee UFS-HSD2023/1289. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TQ: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. MCL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on research originally conducted as part of TQ’s master’s dissertation titled “Exploring Teachers’ Classroom Management Practises in Foundation Phase Multigrade Classrooms in the Alfred Nzo Education District,” submitted in July 2025 to the Faculty of Education, Department of Management, Policy and Comparative Education, University of the Free State. The study was supervised by MCL. The dissertation is unpublished and is not publicly accessible. This manuscript has been revised and adapted for journal publication. The author confirms that the content has not been previously published or disseminated and adheres to ethical standards for original publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Whilst preparing this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT-4o vision and Grammarly to support text structuring, grammatical corrections, style, and language cohesion. QuillBot was also used for paraphrase from the dissertation into this paper.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., and Haerens, L. (2019). Correlates of students’ internalisation and defiance of classroom rules: a self-determination theory perspective. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 22–40. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12213

Alter, P., and Haydon, T. (2017). Characteristics of effective classroom rules: a review of the literature. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 40, 114–127. doi: 10.1177/0888406417700962

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A., and Adams, N. (1977). Analysis of self efficacy theory of behavioral change. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1, 287–310. doi: 10.1007/BF01663995

Bennett, T. (2020). Running the room: the teacher’s guide to behaviour. United Kingdom: John Catt Educational Limited.

Bongala, J. V., Bobis, V. B., Castillo, J. P. R., and Marasigan, A. C. (2020). Pedagogical strategies and challenges of multigrade schoolteachers in Albay, Philippines. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 22, 299–315. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-06-2019-0037

Bosman, R. J., Roorda, D. L., van der Veen, I., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2018). Teacher-student relationship quality from kindergarten to sixth grade and students’ school adjustment: a person-centred approach. J. Sch. Psychol. 68, 177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.006

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Clement, M. C. (2010). Preparing teachers for classroom management: The teacher educator’s role. The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin 77: 41–4.

Demir, I., Sener, E., Karaboga, H. A., and Basal, A. (2023). Expectations of Students from Classroom Rules: A Scenario-Based Bayesian Network Analysis. Participatory Educational Research, 10, 424–442. doi: 10.17275/per.23.23.10.1

du Plessis, P., and Mestry, R. (2019). Teachers for rural schools – a challenge for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 39, S1–S9. doi: 10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1774

Egeberg, H., McConney, A., and Price, A. (2021). Teachers’ views on effective classroom management: a mixed-methods investigation in Western Australian high schools. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 20, 107–124. doi: 10.1007/s10671-020-09270-w

Erden, H. (2020). Teaching and learning in multi-graded classrooms: is it sustainable? Int. J. Curric. Instr. 12, 359–378.

Ettekal, I., and Shi, Q. (2020). Developmental trajectories of teacher-student relationships and longitudinal associations with children’s conduct problems from grades 1 to 12. J. Sch. Psychol. 82, 17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.07.004

Frazier, W. M., and Sterling, D. R. (2005). What Should My Science Classroom Rules Be and How Can I Get My Students to Follow Them? The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 79, 31–35. doi: 10.3200/tchs.79.1.31-35

Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., and Mediratta, K. (2017). Eliminating disparities in school discipline: a framework for intervention. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 253–278. doi: 10.3102/0091732X17690499

Hepburn, L., and Beamish, W. (2020). Influences on proactive classroom management: views of teachers in government secondary schools, Queensland. Improv. Sch. 23, 33–46. doi: 10.1177/1365480219886148

Idris, J. (2020). School leaders’ challenges and needs in leading and managing the multigrade classrooms practice. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 7, 168–173.

Juta, A., and Van Wyk, C. (2020). Classroom management as a response to challenges in mathematics education: experiences from a province in South Africa. Afr. J. Res. Math., Sci. Technol. Educ. 24, 21–30. doi: 10.1080/18117295.2020.1731646

Kanyopa, T. J., and Chibaya, S. (2025). Conceptual analysis of the basic education Laws amendment act and its implications for diversity and inclusion. J. Posthumanism 5:2987. doi: 10.63332/joph.v5i7.2987

Kanyopa, T. J., and Makgalwa, M. M. (2024). The understanding of psychological challenges facing south African school learners in the 21st century: a visual explanatory approach. E-Bangi J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 21:23. doi: 10.17576/ebangi.2024.2102.23

Karaçoban, F., and Karakuş, M. (2022). Evaluation of the curriculum of the teaching in the multigrade classrooms course: participatory evaluation approach. Pegem Egitim ve Ogretim Dergisi 12:9. doi: 10.47750/pegegog.12.01.09

Kartal, A., and Demir, E. (2022). Multi-grade teaching: experiences of teachers and preservice teachers in Turkey. Hungarian Educ. Res. J. 13, 170–188. doi: 10.1556/063.2022.00132

Kaya, S. (2012). Examining the process of establishing and implementing classroom rules in kindergarten. Master Dissertation: Middle East Technical University.

Kivunja, C. (2014). The urgent need to train teachers for multigrade pedagogy in African schooling contexts: lessons from Uganda and Zambia. Int. J. High. Educ. 3:63. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v3n2p63

Letuma, M. C. (2023). Dynamics of managing learners’ classroom disruptive behaviour: experiences of secondary school staff. South Africa: University of Free State. Doctoral Thesis. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11660/12617

Letuma, M. C. (2024a). Alternatives to establishing conducive learning environment (AECLE) model for schools: assertive discipline perspective. Res. Educ. Policy Manag. 6, 42–57. doi: 10.46303/repam.2024.21

Letuma, M. C. (2024b). Understanding the complexities: Exploring secondary school contextual challenges teachers face in addressing indiscipline. Stud. Learn. Tech 5, 334–345. doi: 10.46627/silet.v5i2.418

Little, A. W. (2005). Learning and teaching in multigrade settings. Paper prepared for UNESCO 2005 EFA Monitoring Report.

Marder, J., Thiel, F., and Göllner, R. (2023). Classroom management and students’ mathematics achievement: The role of students’ disruptive behaviour and teacher classroom management. Learning and Instruction, 86. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2023.101746

Mpahla, N. E., and Makena, B. (2021). Rural primary teachers’ experiences of quality teaching and learning in multi-grade schools. ICERI2021 Proceedings: 14th Annual International Conference of Education, 7445–7448

Msimanga, M. R. (2020). Teaching and learning in multi-grade classrooms: the LEPO framework. Afr. Educ. Rev. 17, 123–141. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2019.1671877

Naparan, G. B., and Alinsug, V. G. (2021). Classroom strategies of multigrade teachers. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 3:109. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100109

Naparan, B., Leigh, L., and Castañeda, M. (2021). Challenges and coping strategies of multi-grade teachers. Int. J. Theory Appl. Element. Sec. Schl. Educ. 3, 25–34. doi: 10.31098/ijtaese.v3i1.510

Okeke, C. I., and Akobi, T. O. (2024). Professional development needs as determinants of early childhood educators’ effectiveness in the Motheo District. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 23, 70–88. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.23.11.4

Okeke, C., Akobi, T., and Mohanoe, P.. (2025). Effective verbal disciplining strategies to control classroom misconduct in primary schools. In EDULEARN25 proceedings. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394501318 (Accessed September 12, 2025).

Paramita, P., Sharma, U., and Anderson, A. (2020). Indonesian teachers’ causal attributions of problem behaviour and classroom behaviour management strategies. Camb. J. Educ. 50, 261–279. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2019.1670137

Qayoom, A., Aziz, A., Akram, M., and Khan, F. (2024). Multi-grade Teaching and its Detrimental Effects on the Performance of Primary School Teachers in District Hub, Balochistan. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Entrepreneursh. 4, 2790–7724.

Recla, B., and Potane, J. (2023). Teachers’ challenges and practices in handling multigrade classes: a systematic review. ASEAN J. Open Distance Learn. 15, 73–87.

Republic of South Africa [RSA]. (2022). Personnel administrative measures (PAM) gazette no 46879. Government printer. Available online at: https://www.gpwonline.co.za (Accessed June 14, 2023).

Rubin, A. (2021). Rocking qualitative social science: An irreverent guide to rigorous research. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Sarah, D. (2021). Behaving together in the classroom: a teacher’s guide to nurturing behaviour. London: Open University Press.

Setyaningsih, S., and Suchyadi, Y. (2021). Classroom management in improving school learning processes in the cluster 2 teacher working group in North Bogor City. J. Hum. Soc. Stud. 5, 99–104. doi: 10.33751/jhss.v5i1.3906

Shank, M., and Santiague, L. (2022). Classroom management needs of novice teachers. Clear. House 95, 26–34. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2021.2010636

Strumińska-Kutra, M., and Koładkiewicz, I. (2018). “Case study” in Qualitative methodologies in organization studies: Volume II: Methods and possibilities. eds. M. Ciesielska and D. Jemielniak (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 1–33.

Taole, M. J. (2024). ICT integration in a multigrade context: exploring primary school teachers experiences. Res. Soc. Sci. Technol. 9, 232–252. doi: 10.46303/ressat.2024.13

Tastan, M. A., and Bezci, F. (2023). Bullying from the perspective of multigrade classroom teachers. J. Qual. Res. Educ. 23:34. doi: 10.14689/enad.34.1681

Tredoux, M. (2020). Managing multi-grade teaching for optimal learning in Gauteng west primary schools. Master Dissertation, University of South Africa.

Urma, C. R., and Callo, E. C. (2023). Pedagogical challenges and teaching practices of multigrade teachers in rural public elementary schools. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 10, 219–226. doi: 10.14738/assrj.1012.16017

Walker, S., and Graham, L. (2021). At risk students and teacher-student relationships: student characteristics, attitudes to school and classroom climate. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 896–913. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1588925

Keywords: Foundation Phase, classroom management, early childhood education, multigrade teaching, rural schools

Citation: Qangule T and Letuma MC (2025) One teacher, many grades: Foundation Phase teachers’ experiences in multigrade classroom management. Front. Educ. 10:1685825. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1685825

Edited by:

Mayra Urrea-Solano, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Ririn Ambarini, Universitas PGRI Semarang, IndonesiaUpik Elok Endang Rasmani, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Qangule and Letuma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Motsekiso Calvin Letuma, bGV0dW1hbWNAdWZzLmFjLnph

Tabisile Qangule

Tabisile Qangule Motsekiso Calvin Letuma

Motsekiso Calvin Letuma