- College of Education, Cebu Technological University, Cebu, Philippines

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is gaining recognition as an essential component of academic performance, especially in teacher education programs where emotional competence is critical for engaging with young learners. This research analyzes the significant impact of four emotional intelligence dimensions (Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale) on Learning Performance among pre-service teachers in Bachelor of Early Childhood Education and Bachelor of Elementary Education programs in the Philippines. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized to evaluate the measurement and structural models. The results showed that all four EI dimensions had a significant and positive effect on LP. ROE had a medium effect size, while the other three dimensions had small effect sizes. UOE was the strongest predictor of the path coefficient, which shows how important it is to leverage emotions to boost motivation and cognitive engagement. The model accounted for 57.6% of the variance in LP. These findings contribute to the literature by examining the relatively neglected environment of early childhood and elementary pre-service teachers, offering empirical evidence for the beneficial implications of several EI components in improving learning performance. The study provides theoretical implication for incorporating emotional intelligence development into teacher education programs to enhance academic performance and professional preparedness.

Introduction

The impact of Emotional Intelligence (EI) on a person's ability to navigate the workforce and interpersonal relationships has become an increasingly important topic of interest in education (Shamsi et al., 2024). In the last decades, EI has gained importance in the educational field, as it favors the psychological wellbeing of students and allows them to better understand the environment surrounding them, providing them with the necessary skills, to be able to face everyday situations (Puertas-Molero et al., 2020). Zhang (2025) emphasized that EI is a collection of talents encompassing an individual's self-knowledge, self-management abilities, social awareness, and appropriate behaviors in different situations. EI also has been found to be connected with key skills and important students' competencies that can help to better control emotions and connect with other (Acebes-Sánchez et al., 2019). Petrides et al. (2016) and Phang et al. (2018) suggested that EI is individuals' perception about their emotional dispositions and the ability to recognize, manage, use and understand their own emotions as well as those of others. Chen et al. (2023) highlighted that EI helps students foster positive attitudes toward feedback and regulate negative emotions triggered by criticism, thereby promoting more effective engagement with feedback and empathy. Moreover, EI encompasses a variety of unique skills and characteristics that allow a person to perceive, understand, and regulate their emotions (Shamsi et al., 2024; Issa et al., 2022). Additionally, Zhang et al. (2024) noted that EI is the ability to perceive, access, generate, understand, and regulate emotions, promoting both emotional and intellectual growth. Thus, individual who are emotionally intelligent typically possess a clear understanding of their requirements, strengths, weaknesses, and capabilities (Zhang, 2025).

(Dover and Amichai-Hamburger 2023) emphasized that that individuals with high levels of EI can identify and regulate negative emotions while generating and utilizing positive emotions to facilitate thinking and decision making. Moreover, Saud (2019) highlighted that EI has a high impact on many aspects of a learner's life and academic performance level. For instance, students possessing EI frequently exhibit more proficiency in articulating intricate emotional nuances through their artistic endeavor (Costa and Cipolla, 2025), establishes healthy and positive relationships (Sharma, 2024), influences capacity to control conduct, navigate complex social circumstances, and make personal decisions that result in positive results (Chung et al., 2023), enjoy greater productivity, success, and positive health outcomes (Kotsou et al., 2019), protector against mental illness and potentially increases mental health (Nguyen et al., 2025), high EI can positively influence adaptive coping styles (Mavroveli et al., 2007) and general academic performance (Gugliandolo et al., 2015; Petrides et al., 2004). Moreover, emotions can significantly influence students' engagement, motivation, and overall success (Lantolf and Poehner, 2023). Given this contribution of Emotional Intelligence (EI) to education, it is undeniable that EI plays a significant influence in the academic endeavors and success of students in higher education.

Emotions significantly impact the academic performance. Building upon this foundational understanding, Pishghadam (2009) and Abera (2023) have demonstrated through empirical studies that students with higher levels of EI tend to achieve better academic results. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial to foster supportive learning environments that mitigate negative emotions and promote positive ones (Zhang et al., 2024). Several researches have been undertaken to ascertain the contribution of EI in higher education, but there is still very little research that directly examines how different EI (i.e., self-emotion appraisal, others' emotion appraisal, regulation of emotion, and use of emotion) affect learning performance for students taking Bachelor in Early Childhood Education and Bachelor in Elementary Education.

Prior research predominantly concentrated on general teacher education or students from various disciplines (Trigueros et al., 2019; Keefer et al., 2018), neglecting the distinctive emotional demands associated with early childhood and elementary education, where pre-service teachers must possess advanced emotional competencies to engage effectively. Moreover, limited research has employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the predictive capacity of Emotional Intelligence (EI) on student performance in this particular domain, despite SEM's efficacy in assessing both measurement and inter-variable correlations (Hair et al., 2021). This study fills the gap by employing SEM to investigate the impact of emotional intelligence on learning performance among pre-service teachers, including those enrolled in early childhood and primary education programs in the Philippines. This study will examine the impact of emotional intelligence on the academic performance of pre-service teachers in early childhood and elementary education Using structural equation modeling, it will shed light which components of EI are most significant. This will enable higher educational institutions (i.e., state universities and colleges) create programs that improve these skills, which will lead to improved learning performance of the students.

Literature review

Emotional intelligence

Thorndike (1920) introduced the notion of Emotional Intelligence (EI) in the 1920s, categorizing it as abstract, mechanical, and social. Later, in the 1980s, various scholars added additional contributions to the concept of emotional intelligence. Gardner (2013) introduced the concepts of intra-emotional intelligence and inter-emotional intelligence. Steiner (1984) proposed the concept of EI. Salovey and Mayer (1990) developed the idea of “emotional intelligence” based on the contributions of these researchers. Moreover, emotional intelligence has been intensively researched in various fields, including organizational behavior, human resources, and management. George (2000) is of the view that individuals are different from each other in terms of degree of awareness about their emotions and expression of verbal and non-verbal emotions. Additionally, interest in emotional intelligence (EI) has increased greatly over the last decade. Although some researchers and practitioners have been quite optimistic about the importance of EI in organizations, critical questions remain about the concept, theory, and measurement of (Landy and Conte, 2004; Matthews et al., 2002). Day and Carroll (2004) emphasized that the relationship between various aspects of emotional intelligence and individual performance in terms of decision making. They explained that, better performance can be achieved through emotional performance.

Self-emotion appraisal

Self-emotion appraisal is the ability to detect and understand one's feelings. This skill helps students understand how emotions affect their thinking, motivation, and learning. Students with excellent self-emotion evaluation can detect and handle stress and frustration, which helps them focus and continue in school (Law et al., 2004; Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal, 2005). Awareness increases self-regulation and problem-solving in higher education, improving learning outcomes (Pekrun et al., 2017). Self-emotion appraisal helps pre-service teachers adapt to problems, stay motivated, and communicate well with colleagues and instructors (MacCann et al., 2020). Self-emotion appraisal is crucial to academic performance since it is the first step to emotion regulation.

H1. Self-emotion appraisal has a positive influence on learning performance.

Regulation of emotion

Regulation of emotion is how students handle their feelings so they can pay attention, remember things, and keep going with their work (Broderick, 2021). Cognitive reappraisal enhances concentration, engagement, and academic success, whereas expressive suppression does not (Ahmed, 2020; Montasser, 2019). Because they participate more and have less exam anxiety and stress, emotionally balanced adolescents perform better in school (Arsenio and Loria, 2014). Recent meta-analysis suggests that emotion regulation components predict emotional intelligence success (MacCann et al., 2020). All this demonstrates that emotionally stable students perform better academically. Thus, the hypothesis was constructed:

H2. Regulation of emotion has a positive influence on learning performance.

Others emotion appraisal

The ability to recognize, understand, and assess one's own and others' emotions corresponds to others emotion appraisal. This skill improves learning by helping students manage stress, academic issues, and motivation (Pekrun et al., 2017). Effective emotion assessment helps students manage negative emotions, solve issues, and focus on academic tasks, improving performance (MacCann et al., 2020). Emotional assessment helps students meet course expectations, boosting academic resilience (Trigueros et al., 2019). Others emotion appraisal promotes learning group performance and peer interactions (Perera and DiGiacomo, 2013). Given these findings, students with higher emotional assessment should do better intellectually. Thus, the hypothesis was constructed:

H3. Emotion appraisal has a positive influence on learning performance.

Use of emotion

Emotion use is the process of using feelings like excitement and optimism to drive thought, keep working hard, and solve problems. According to the Wong–Law EI framework, this trait predicts important outcomes because students who can “use” their feelings are more likely to study and keep at it (Law et al., 2004). Positive feelings make it easier to pay attention, think, and interact with others, which helps with learning and performance (Fredrickson, 2001). Enjoyment and hope make students do better in school, while fear and boredom make them do worse (Pekrun et al., 2017). A meta-analysis shows that emotional intelligence, which includes using emotions in a healthy way, improves academic success in ways that go beyond cognitive ability (MacCann et al., 2020). EI raises performance by increasing academic involvement and social-emotional skills, which are important for doing well in college (Perera and DiGiacomo, 2013). These results show that students learn more when they use their feelings to inspire and focus.

H4. Use of Emotion has a positive influence on learning performance.

Learning performance

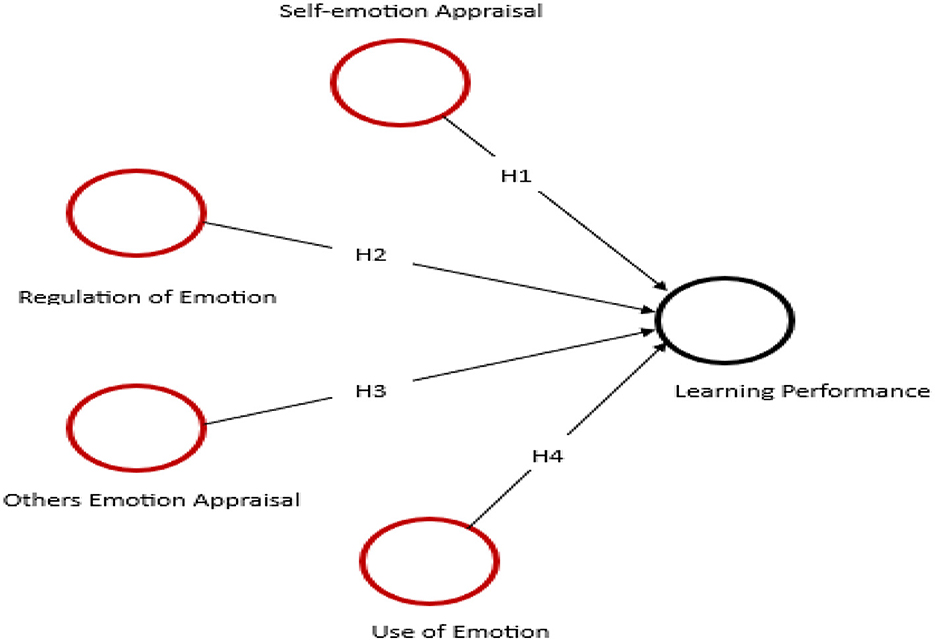

Learning performance refers to the ability of students to achieve desired academic outcomes, often measured through grades, test scores, or skill acquisition (Guskey, 2013). It is influenced by a range of factors, including cognitive abilities, motivation, emotional intelligence, teaching quality, and learning environment (Kasemy et al., 2022). Empirical research by Morrison (1999) examined various student attributes associated with academic motivation. These findings suggested that either cognitive abilities or non-ability traits can have a strong positive influence on both academic performance and subsequent employment performance (Griffin et al., 2013). Moreover, studies show that psychological aspects, such as self-regulation and emotional management, play an important role alongside traditional academic skills (Putwain et al., 2013). Technology integration, active learning strategies, and supportive feedback have also been found to enhance student learning outcomes (Wang, 2020). In higher education, understanding what drives learning performance is essential for designing interventions that improve student success and prepare them for professional demands (Norris et al., 2008). The conceptual framework of the study, which illustrates the hypothesized relationships among emotional intelligence constructs and learning performance, is presented in Figure 1.

Methods

Instruments

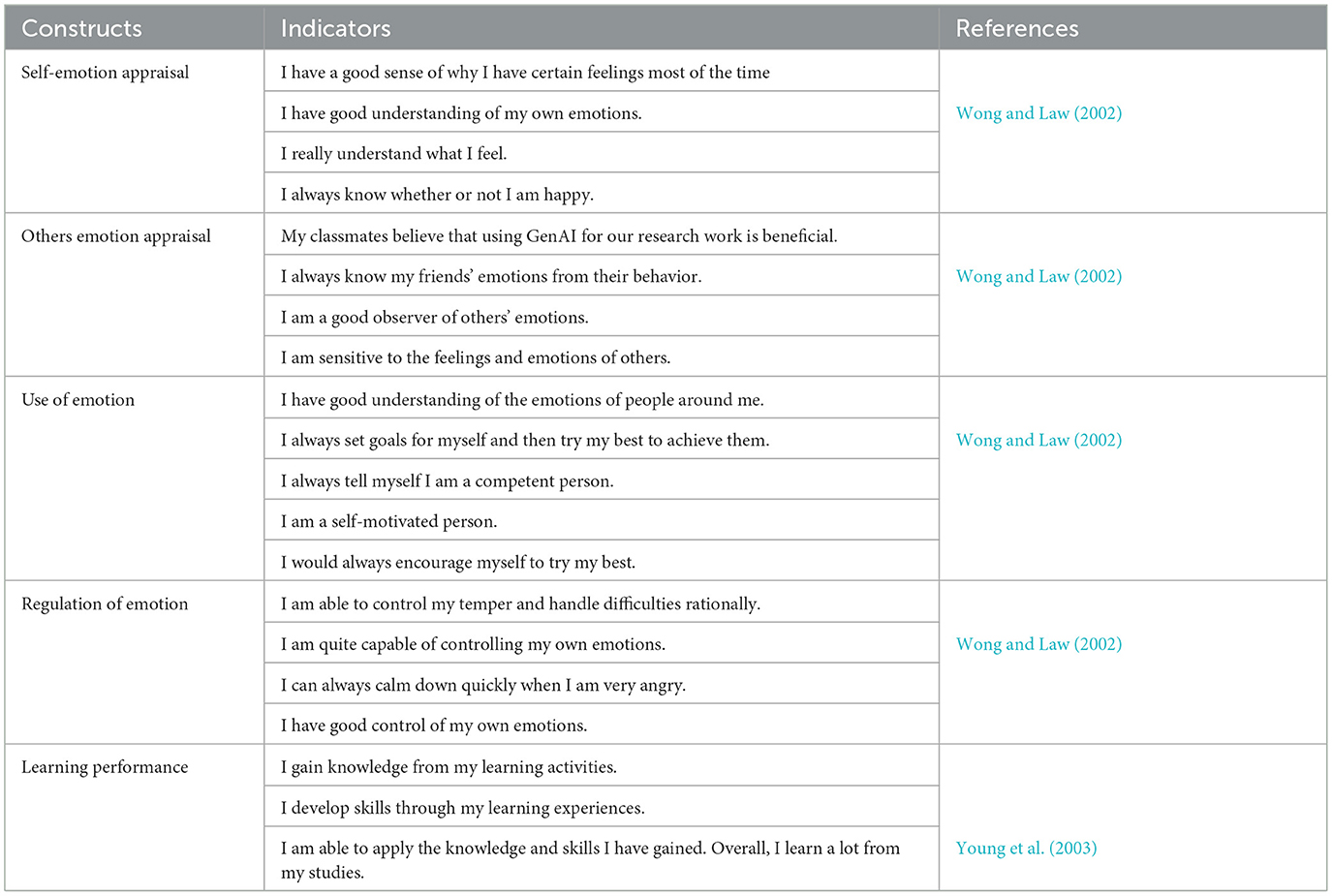

The constructs in the proposed model were assessed using items that were developed after conducting a comprehensive literature review (Appendix 1). Emotional Intelligence (EI) was assessed using the Wong and Law (2002) with 16 items. There are four subscales, with four items each. The questionnaire includes self-emotion appraisals (SEA), Others' Emotion Appraisals (OEA), Regulation Of Emotion (ROE), and Use Of Emotion (UOE). Whereas, the items for measuring Learning Performance (LP) of students were taken from Young et al. (2003). A 7-point Likert scale was employed to evaluate each construct in the survey instrument. Items in all of the constructs transitioned from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” In order to enhance the questionnaire's instructions, questions, difficulty, phrasing, order, form, and structure, a pre-test was administered. The pretest was distributed to ten individuals, who were subsequently requested to complete it. Any modifications that were necessary were implemented prior to the commencement of the actual collection, as indicated by their responses. For IE no modifications on EI were implemented since the responses were consistent, clear, and indicated that the instrument was understandable and appropriate for the study's objectives. However, for LP, the indicators were revised align with the objectives and function of the study.

Data collection

Participants in the study were undergraduate students from one of the Philippines' major state universities. The participants were senior College of Education students pursuing bachelor's degrees in elementary and early childhood education. This study involved a total of 819 students. The data was obtained via online platforms (i.e., Google Forms). The study used online surveys to collect and analyze data more efficiently. As a general rule of thumb, the minimum sample size should be ten times the maximum number of arrows that lead to the latent variable in the PLS path mode (Hair et al., 2021). As a result, the minimal sample size for this study was 40, as recommended by Hair et al. (2021). According to the rule of thumb, the sample size in this study is more than adequate because the number of respondents exceeds the minimum required.

Data analysis results

Hair et al. (2017) emphasized that in using PLS-SEM, the first criterion for evaluating the model is an assessment of the reliability and validity of the measures. The measurement model assessment result shows that all the indicators were convergent and reliable, as shown in Table 1, where the factor loading for each item is above the threshold value of 0.70 (Henseler et al., 2009). Additionally, the AVE statistics for each construct range from 0.773 to 0.881, which is higher than the proposed threshold of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). This indicates that all the constructs in the model had an appropriate convergent validity. In addition, the measures were all reliable, with all the constructs being above the Cronbach's alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR) threshold value of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2017).

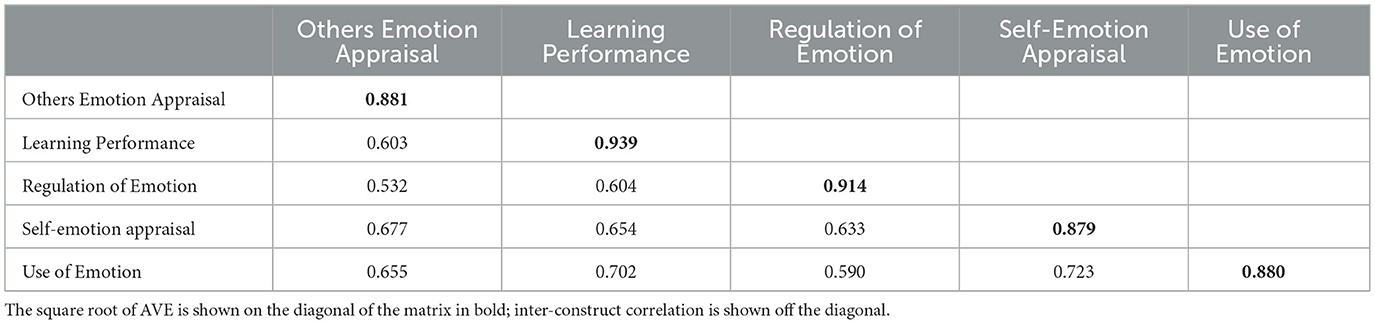

Fornell and Larcker (1981) demonstrated discriminant validity by finding that the average variance extracted (AVE) of the constructs was greater than the squared correlation of each latent variable. As indicated in Table 2, the values in bold inside the data table represent the square roots of the AVE, whilst the values in the table that are not bolded represent the intercorrelation values between the structures. Off-diagonal values less than the square roots of the AVE are thought to be compatible with the Fornell and Larker criteria.

Structural model assessment

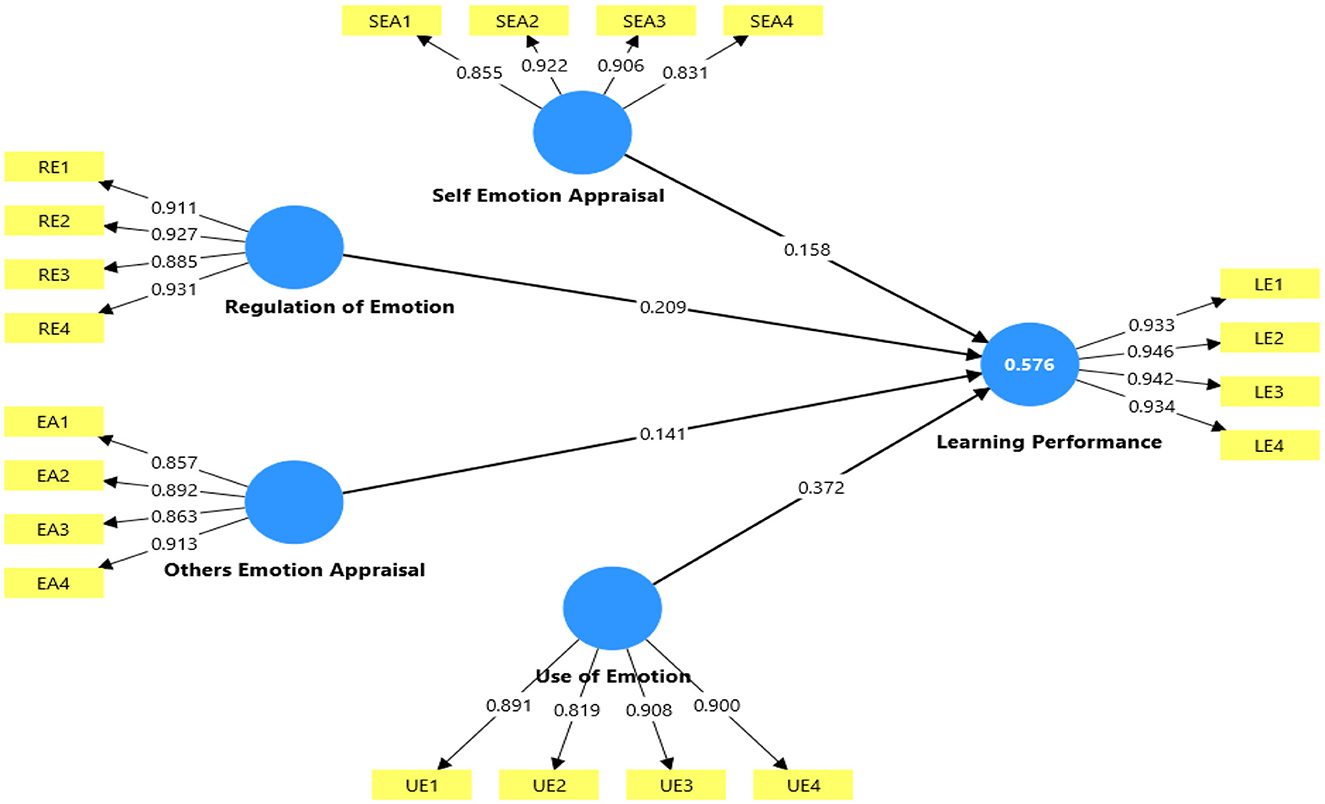

The summary of the measurement model, including factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted, is shown in Table 3. This study examined the predictive capacity of the model's endogenous variables, a finding from the PLS-SEM results (Sarstedt et al., 2014). The structural model was assessed utilizing PLS-SEM, focusing on the significance of the path coefficients, R2 values (predictive power), and f2 (effect size) (Hair et al., 2017). The route coefficient outcomes of the structural model that validate the proposed hypotheses are detailed in Table 4 and displayed in Figure 2. All 4 hypotheses were supported.

Figure 2 displays the structural model's R2 value, which represents its prediction accuracy. R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 were considered acceptable according to the rule of thumb for prediction accuracy (Henseler et al., 2009; Hair et al., 2011). With an R2 of 0.576 (58%), the model's R2 values demonstrated that LP accounted for the most variation.

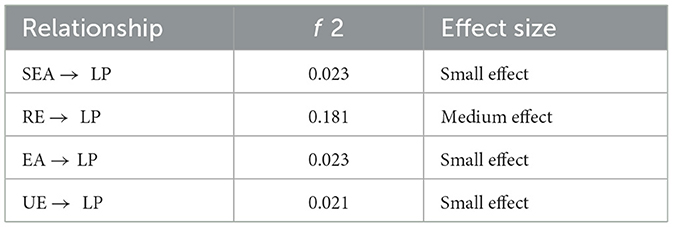

Using the PLS algorithm, effect sizes (f2) of 0.02, 0.15, 0.35 were calculated, indicating small, medium or significant effects, respectively, on the relationship between the exogenous and endogenous constructs (Hari et al. 2017). A value of less than 0.2 indicates no effect of the exogenous constructs on an endogenous construct. The (f2) result showed that RE and LP, had medium effects, while SEA and LP, EA and LP, and UE and LP had small effects. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

This study proposed a model examining the influence of Emotional Intelligence (EI) dimensions among pre-service teachers in early childhood and elementary education programs. Using PLS-SEM, the model demonstrated moderate predictive accuracy, with LP accounting for 57.6% of the variance (R2 = 0.576). All four hypotheses were supported, confirming the robustness of the framework in explaining how EI contributes to academic achievement in this context. The results revealed that UE had the largest path coefficient (β = 0.372) but a small effect size (f2 = 0.021), indicating that while the ability to channel emotions toward learning significantly predicts LP, its incremental explanatory power over other EI components is limited. This supports prior work by Law et al. (2004) and Pekrun et al. (2017), which showed that positive emotions such as enthusiasm and hope enhance engagement and persistence, thereby improving performance. SEA (β = 0.158, f2 = 0.023) and EA (β = 0.141, f2 = 0.023) also exhibited significant positive effects on LP, consistent with MacCann et al. (2020) and Perera and DiGiacomo (2013), who highlighted that accurate self- and other-emotion evaluation fosters adaptive coping, resilience, and academic focus. RE (β = 0.209) emerged as the second-strongest predictor, with a medium effect size (f2 = 0.181), reinforcing evidence from Arsenio and Loria (2014) that students who can effectively regulate negative emotions, such as stress and anxiety, perform better academically.

Notably, while all EI components were significant, their relative contributions suggest complementary roles such as SEA and OEA establish emotional awareness, ROE ensures emotional stability, and UOE translates emotions into motivational and cognitive resources for learning. This aligns with Broderick (2021) and Fredrickson's (2001) broaden and build theory, where positive emotions expand cognitive capacity and social resources. Unlike some prior studies that found ROE to be the dominant EI predictor of performance (e.g., Ahmed, 2020), the present findings indicate a more balanced interplay among the four dimensions, suggesting that for pre-service teachers, the capacity to use emotions constructively is as critical as regulating or appraising them. Overall, the results underscore that enhancing EI in teacher education particularly fostering skills to harness emotions for motivation UOE and maintaining composure under stress RE can have meaningful impacts on academic success. These findings carry important implications for curriculum design in teacher preparation programs, supporting the integration of targeted EI training to optimize learning performance.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that emotional intelligence dimensions (i.e., SEA, ROE, OEA, UOE), significantly enhances the learning performance of pre-service teachers in early childhood and elementary school. Applying structural equation modeling, all four factors demonstrated a positive influence, with regulation of emotion exhibiting a medium effect and the remaining constructs displaying small but still significant effects. The findings indicate that cultivating emotional competencies can assist prospective educators in dealing with stress, maintaining motivation, and enhancing their academic engagement. These results can be used by higher education to create training programs that improve students' emotional intelligence. This will enhance students‘ academic performance and equip them with the affective skills necessary to become educators.

Theoretical implications

This research makes a significant contribution to the expanding body of literature on Emotional Intelligence (EI) by demonstrating how the four components of EI (self-emotion appraisal, others emotion appraisal, regulation of emotion, and use of emotion) predict learning performance among pre-service teachers in early childhood and elementary education. Previous research has frequently investigated Emotional Intelligence (EI) in broad student populations however, this study expands upon that research by concentrating on the specific emotional demands that are associated with teacher education. The findings, which were obtained through the use of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), the findings support the theoretical premise that EI not only influences social and emotional functioning but also directly enhances academic outcomes. Emotional intelligence (EI) aspects are associated yet different determinants of performance, as confirmed by the findings, which lend support to models such as the Wong–Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) framework. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the significance of incorporating emotional skills into teacher preparation programs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RS: Validation, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Software, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. AD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. HG: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ME: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft. HP: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abera, W. G. (2023). Emotional intelligence and pro-social behavior as predictors of academic achievement among university students. Commun. Health Equity Res. Policy 43, 431–441. doi: 10.1177/0272684X211033447

Acebes-Sánchez, J., Díez-Vega, I., Esteban-Gonzalo, L., and Rodríguez-Romo, G. (2019). Physical activity and emotional intelligence among undergraduate students: a correlational study. BMC Publ. Health 19:1241. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7576-5

Ahmed, K. A. M. (2020). Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression: an examination of their associations with seeking social support, well-being and academic performance. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 6, 1–11.

Arsenio, W. F., and Loria, S. (2014). Coping with negative emotions: connections with adolescents' academic performance and stress. J. Genet. Psychol. 175, 76–90. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2013.806293

Broderick, P. C. (2021). Learning to Breathe: A Mindfulness Curriculum for Adolescents to Cultivate Emotion Regulation, Attention, and Performance. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Chen, H., Zhang, S., Xu, J., Du, R., and Tang, S. (2023). Effect of the teacher–student relationships on feedback literacy of high school students in Tibetan areas of China: mediating effect of emotional intelligence and moderating effect of ethnicity category. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 33, 419–429. doi: 10.1007/s40299-023-00739-9

Chung, S. R., Cichocki, M. N., and Chung, K. C. (2023). Building emotional intelligence. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 151, 1–5. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009756

Costa, M. F. B., and Cipolla, C. M. (2025). Critical soft skills for sustainability in higher education: a multi-phase qualitative study. Sustainability 17:377. doi: 10.3390/su17020377

Day, A. L., and Carroll, S. A. (2004). Using an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence to predict individual performance, group performance, and group citizenship behaviours. Pers. Individ. Dif. 36, 1443–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00240-X

Dover, Y., and Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2023). Characteristics of online user-generated text predict the emotional intelligence of individuals. Sci. Rep. 13:6778. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33907-4

Extremera, N., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2005). Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: predictive and incremental validity using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Pers. Individ. Dif. 39, 937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.012

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gardner, H. (2013). “The theory of multiple intelligences,” in Teaching and Learning in the Secondary School, eds. N. Selwyn and J. Potter (London: Routledge), 38–45.

George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: the role of emotional intelligence. Hum. Relat. 53, 1027–1055. doi: 10.1177/0018726700538001

Griffin, R., MacKewn, A., Moser, E., and VanVuren, K. W. (2013). Learning skills and motivation: correlates to superior academic performance. Bus. Educ. Accred. 5, 53–65. doi: 10.19030/cier.v5i2.6928

Gugliandolo, M. C., Costa, S., Cuzzocrea, F., Larcan, R., and Petrides, K. V. (2015). Trait emotional intelligence and behavioral problems among adolescents: a cross-informant design. Pers. Individ. Dif. 74, 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.032

Guskey, T. A. (2013). “Defining student achievement,” in International Guide to Student Achievement, eds. J. Hattie and E. M. Anderman (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–6.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., and Danks, N. P. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. Cham: Springer.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed, a silver bullet. J. Market. Theor. Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). “The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing,” in Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20, eds. R. R. Sinkovics and P. N. Ghauri (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 277–319.

Issa, M. R., Muslim, N. A., Alzoubi, R. H., et al. (2022). The relationship between emotional intelligence and pain management awareness among nurses. Healthcare 10:1113. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10061047

Kasemy, Z. A., Kabbash, I., Desouky, D., Abd El-Raouf, S., Aloshari, S., and El Sheikh, G. (2022). Perception of educational environment with an assessment of motivational learning strategies and emotional intelligence as factors affecting medical students' academic achievement. J. Educ. Health Promot. 11:303. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1772_21

Keefer, K. V., Parker, J. D. A., and Saklofske, D. H., (eds.). (2018). Emotional Intelligence in Education: Integrating Research With Practice. Cham: Springer.

Kotsou, I., Mikolajczak, M., Heeren, A., Grégoire, J., and Leys, C. (2019). Improving emotional intelligence: a systematic review of existing work and future challenges. Emot. Rev. 11, 151–165. doi: 10.1177/1754073917735902

Landy, F. J., and Conte, J. M. (2004). Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lantolf, J. P., and Poehner, M. E. (2023). Sociocultural theory and classroom second language learning in the East Asian context: Introduction to the special issue. Mod. Lang. J. 107, 3–23. doi: 10.1111/modl.12816

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., and Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 483–496. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

MacCann, C., Jiang, Y., Brown, L. E., Double, K. S., Bucich, M., and Minbashian, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 150–186. doi: 10.1037/bul0000219

Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., and Roberts, R. D. (2002). Emotional Intelligence: Science and Myth. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Mavroveli, S., Petrides, K. V., Rieffe, C., and Bakker, F. (2007). Trait emotional intelligence, psychological well-being and peer-rated social competence in adolescence. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 25, 263–275. doi: 10.1348/026151006X118577

Montasser, M. (2019). Rethinking the role of anxiety: using cognitive reappraisal in the classroom. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 6, 1–7.

Morrison, B. H. (1999). Acknowledging student activities associated with academic motivation. J. Dev. Educ. 23, 7–16.

Nguyen, Q. A. N., Tran, T., Tran, T. A., Nguyen, T. V., and Fisher, J. (2025). Validation of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire–Adolescent short form (TEIQue-ASF) among adolescents in Vietnam. SSM Ment. Health 7:100413. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2025.100413

Norris, D., Baer, L., Leonard, J., Pugliese, L., and Lefrere, P. (2008). Action analytics: measuring and improving performance that matters in higher education. Educause Rev. 43, 42–67.

Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Marsh, H. W., Murayama, K., and Goetz, T. (2017). Achievement emotions and academic performance: longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Dev. 88, 1653–1670. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12704

Perera, H. N., and DiGiacomo, M. (2013). The relationship of trait emotional intelligence with academic performance: a meta-analytic review. Learn. Individ. Differ. 28, 20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.08.002

Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., and Furnham, A. (2004). The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance and deviant behavior at school. Pers. Individ. Diff. 36, 277–293. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9

Petrides, K. V., Furnham, A., and Mavroveli, S. (2007). “Trait emotional intelligence: moving forward in the field of EI,” in Emotional Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns, eds. G. Matthews, M. Zeidner, and R. Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 151–166. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195181890.003.0006

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J., Furnham, A., and Pérez-González, J. C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 8, 335–341. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650493

Phang, C. M., Abu Bakar, N. R., and Ismail, N. (2018). The relationship between emotional intelligence and academic achievement among Malaysian undergraduates. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 8, 1153–1167. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i5/4205

Pishghadam, R. (2009). A quantitative analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and foreign language learning. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 6, 31–41.

Puertas-Molero, F., Zurita-Ortega, F., Chacón-Cuberos, R., Castro-Sánchez, M., Ramírez-Granizo, I., and González-Valero, G. (2020). Emotional intelligence in the educational field: A meta-analysis. Anales de Psicol. 36, 84–91. doi: 10.6018/analesps.345901

Putwain, D., Sander, P., and Larkin, D. (2013). Academic self-efficacy in study-related skills and behaviours: relations with learning-related emotions and academic success. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 83, 633–650. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02084.x

Salovey, P., and Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 9, 185–211. doi: 10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Saud, W. I. (2019). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to academic performance among Saudi EFL undergraduates. Int. J. High. Educ. 8, 222–230. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v8n6p222

Shamsi, A., Varkey, D. A., and Wanat, M. A. (2024). The importance of coaching pharmacy students beyond their emotional intelligence assessment scores. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 88:101264. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpe.2024.101264

Sharma, K. (2024). Emotional intelligence, general wellbeing and acceptance action among young adults: A correlational study. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 12, 183–193.

Steiner, C. (1984). Emotional literacy. Transact. Anal. J. 14, 162–173. doi: 10.1177/036215378401400301

Trigueros, R., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Cangas, A. J., Bermejo, R., Ferrándiz, C., and López-Liria, R. (2019). Influence of emotional intelligence, motivation and resilience on academic performance and the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:2810. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16162810

Wang, Y. H. (2020). Design-based research on integrating learning technology tools into higher education classes to achieve active learning. Comput. Educ. 156:103935. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103935

Wong, C. S., and Law, K. S. (2002). Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale. The Leadership Quarterly.

Young, M. R., Klemz, B. R., and Murphy, J. W. (2003). Enhancing learning outcomes: the effects of instructional technology, learning style, instructional methods, and student behavior. J.Market. Educ. 25, 130–142. doi: 10.1177/0273475303254004

Zhang, T., Zhang, R., and Peng, P. (2024). The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and English language performance among Chinese EFL university students: the mediating roles of boredom and burnout. Acta Psychol. 248:104353. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104353

Zhang, Y. (2025). Impact of arts activities on psychological well-being: emotional intelligence as mediator and perceived stress as moderator. Acta Psychol. 254:104865. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104865

Sarstedt, M, Ringle, C. M., Smith, D., Reams, R., Joseph, F., and Hair, J. F. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 5, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.01.002

Appendix A

Keywords: emotional intelligence, self-emotion appraisal, others emotion appraisal, regulation of emotion, use of emotion, learning performance

Citation: Suson R, Duites A, Gamboa HM, Entice M, Capuno JF, Cabaron AJ, Sim MJ and Paubsanon H (2025) Emotional intelligence as predictor of learning performance in higher education: a SEM approach. Front. Educ. 10:1685826. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1685826

Received: 14 August 2025; Accepted: 13 October 2025;

Published: 08 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sonia Brito-Costa, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Bakht Jamal, SED, PakistanDamanpreet Kaur, Rayat Bahra Group - Hoshiarpur Campus, India

Copyright © 2025 Suson, Duites, Gamboa, Entice, Capuno, Cabaron, Sim and Paubsanon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roberto Suson, cm9iZXJ0b3N1c29uMjlAZ21haWwuY29t

Roberto Suson

Roberto Suson Adrian Duites

Adrian Duites