- Faculty of Anatomy Division, Biomedical Sciences Department, College of Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

Anatomy is the key to medical education, and this study examines the current landscape of anatomy education in Saudi Arabia medical colleges utilizing problem-based learning (PBL) curricula, with the goal of optimizing pedagogical approaches and content dissemination. This study consolidated insights from students, faculty, and institutional frameworks to underscore significant challenges. These include the curtailment of essential anatomical content, inadequate reinforcement across the curriculum, a dearth of formalized faculty training and language-associated impediment stemming from the use of English as the primary language of instruction. Such challenges could undermine the comprehensive anatomical knowledge necessary for ensuring clinical proficiency and patient safety. The suggested modification encompasses the incorporation of anatomy across all stages of medical, education specialized faculty training, and the adoption of pedagogies that are culturally and linguistically appropriate. This study recommends standardized core anatomy curriculum, faculty training to implement dual language instructional techniques and the Saudi association for anatomical sciences to adopt a more prominent leadership position to improve and collaborate anatomical education in the Kingdom. Resolving these challenges enhance student engagement and knowledge retention, thereby harmonizing anatomy education with the healthcare commands of Saudi Arabia and objectives of vision 2030. In conclusion, this analysis culminates in a recommendation for a systematic change aimed at fostering excellence in anatomy education.

1 Introduction

Curriculum has been defined by several scholars as a strategic schema or a structured framework that details the procedure for realizing educational goals (Hegazy, 2015). The curriculum needs to align with the healthcare requirements of the community (Bin Abdulrahman et al., 2022). The increasing adoption of modern medical curricula by medical schools to equip students for future roles highlights the necessity for creating updated curricula that aligned with the evolving needs of future physicians (Yaqinuddin et al., 2016). In Saudi Arabia, medical colleges employ a variety of curricula due to reforms in the last decade to align with global changes in medical education (Azer et al., 2013). Traditional anatomy teaching is replaced by inquiry based and cooperative approaches including case-based learning, problem-based learning and team-based learning to foster student-centered active learning environments (Bolla and Saffar, 2022).

Problem based learning (PBL) is regarded as an effective instructional approach that is student-centered. Problem based learning was initially conceptualized as a medical education strategy at McMaster University in 1969 (Trullàs et al., 2022). This shifted from traditional methods and introduced student-centered learning McMasters university's novel approach to medical education integrated basic and clinical sciences (Salih et al., 2023). The PBL method offers several benefits compared to traditional curricula, including the integration of basic and clinical skills, enhanced communication skills and improved motivational factors (Potu et al., 2013). PBL promotes deep active learning and enhances knowledge retention (Almagribi et al., 2024). It also develops essential skills and attitude for future practice, increases student engagement, and facilitates the integration of core curriculum (Salih et al., 2023). These advantages are consolidated to a clinical problem-solving approach essential for practicing clinicians (Salih et al., 2024).

In PBL curricula, a subject's integration and understanding are determined by the number of learning objectives included in the clinical problem presented to students. This directly influences importance and emphasis students place on that subject. Studies analyzing anatomy learning objectives within PBL curriculum revealed that anatomy was not comprehensive and consistently covered in all modules (Potu et al., 2013).

Anatomy, a fundamental component of undergraduate medical education, has historically been imparted through methods such as cadaveric dissection and didactic lectures (Hegazy, 2015). The medical education system in Saudi Arabia has undergone significant changes marked by a notable increase in both the enrollment of medical students and establishment of medical colleges (Algahtani et al., 2020). The ongoing evolution of medical education in Saudi Arabia necessitates a consistent re-evaluation and improvement of pedagogical approaches particularly in fundamental disciplines such as anatomy (Hassanien, 2018). For medical students it is essential to integrate basic sciences with clinical practice to facilitate development of clinical skills radiological diagnostic skills and surgical skills (Bolla and Saffar, 2022). Nevertheless, several impediments impede the delivery of current anatomy instruction, thus warranting both inventive resolutions and the investigation of avenues to ameliorate learning outcomes (Yaqinuddin et al., 2016).

The integration of anatomy teaching with a PBL curriculum requires an innovative approach. Studies suggest that anatomy teaching within PBL curricula is more effective, leading to enhanced student performance compared to traditional methodologies (Alghamdi et al., 2024). However, PBL may not comprehensively address all fundamental anatomical knowledge (Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023). The incorporation of new skills and molecular biology decreased the basic sciences content within the PBL curriculum. Concerns have been raised regarding reductions in anatomy content, in the quality of surgical expertise and patient safety. This concern necessitates medical educators investigate the underlying factors contributing to this decline in anatomy teaching (Bolla and Saffar, 2022).

In Saudi Arabia anatomy education, a critical element of medical training, is navigating a complex environment shaped by contemporary pedagogical approaches and the specific healthcare needs of the Kingdom (Barbosa et al., 2020). Anatomy education in Saudi Arabia is indispensable for medical student as it lays the groundwork for clinical practice (Yaqinuddin et al., 2016). Despite the availability of advanced technologies and substantial resources, anatomy education in Saudi Arabia is confronted by a complex range of obstacles (Abdel Hamid, 2017). The integration of imaging anatomy modules into PBL curricula is proving difficult due to the emphasis placed on vertical and horizontal integration in medical colleges as well as the early introduction of clinical medicine (Bandyopadhyay and Biswas, 2017). The effectiveness of PBL and integrated curricula in anatomy education in Saudi Arabia is hindered by significant challenges that require resolution. A primary challenge stems from the varied pedagogical approaches and diverse curricula implemented across various medical colleges throughout the country (Bolla and Saffar, 2022). Depending on the curricular structure across medical colleges in Saudi Arabia, the delivery of anatomy education varies (Periya, 2017). These variations raise concerns regarding the fulfillment of essential learning outcomes and whether the anatomy component encompasses the most prevalent cases encountered in Saudi Arabia, with their corresponding anatomical considerations (Bolla and Saffar, 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to reformulate the anatomy curriculum in Saudi Arabia ensuring that graduates are well prepared to meet the health care needs of the population (Kemeir, 2012). This endeavor ensures that the competencies of healthcare graduates are in accordance with the demands of the nation, as articulated in Saudi vision 2030. The essential component of Saudi vision 2030 represents advancement of the healthcare system to deliver superior healthcare services to Saudi citizens (Fallatah, 2016).

The number of studies focusing on the medical PBL curriculum in Saudi Arabia remains limited. To date, no research has specifically examined anatomy teaching within the PBL curriculum in the country addressing the challenges and harnessing the identified opportunities. This review explores the challenges and opportunities in anatomy education within Saudi Arabia, considering factors such as curriculum design teaching methodologies, technological integration and social considerations. The primary motivation for this research and article stems from professional interest. The specific aims of this study were to determine the status of anatomy education in medical colleges in Saudi Arabia, to identify the major challenges and opportunities facing anatomy education in the Kingdom and to propose recommendations for improving anatomy education in the country.

2 Manuscript formatting

2.1 Material and methods

2.1.1 Study design

The study was designed as a narrative review, through a literature to recognize challenges and opportunities while teaching anatomy in a PBL curriculum in universities of Saudi Arabia (see Appendix A). This narrative review allows to stipulate a rich, contextualized understanding of the challenges and opportunities in anatomy education within the specific context of PBL in Saudi Arabia. The current study was guided by the PCC (Population, concept and context) framework as recommended by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) to construct clear and meaningful objectives and inclusion criteria (Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), 2020). This framework was applied to define the scope of the review and guide the selection of relevant studies. The PCC framework provided conceptual boundaries for the review, ensuring that the included studies were relevant to the population and educational context of Saudi Arabia and focused on anatomy teaching within PBL curricula (Table 1).

2.1.2 Data collection

The literature search was conducted for articles published between 2010 and 2025. The combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text key words was applied to align with the subject of this narrative review related to anatomy, PBL, and medical education in Saudi Arabia. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine terms appropriately. The research studies were manually searched using the keywords as given in detail in Table 1 across the database such as Pub-med, Scopus and Web of Science etc. For data search in Pub-med, the search string was used as (“Anatomy” [MeSH] OR “Anatomy teaching” AND “Problem-Based Learning” [MeSH] AND “Education, Medical” AND “Saudi Arabia” [MeSH]. Similar search strategies were adapted for other specific databases (Table 2).

2.1.3 Data extraction

Data extraction was performed manually by reviewing full texts and summarizing relevant findings under the initial deductive codes. No software tools (GenAI) were used. For limiting the number of studies for relevance and determining future research directions, the literature screening of titles, abstracts and full text was performed based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 3).

2.1.4 Overview of data included (PRISMA approach)

This study adopts a narrative review design, a PRISMA approach incorporated (Ferrari, 2015; Green et al., 2006) to enhance transparency and traceability in the literature identification and selection process. Using the PRISMA approach, a three-phase literature search was carried out. In total, 139 articles were selected using publication titles, keywords, and abstracts in 9 databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, MDPI, SpringerLink Journals, Science Direct, Wiley Online Library, Taylor & Francis Library, Google Scholar) directly without using GenAI. In next phase, author read each article thoroughly and found fifty-six relevant articles. These articles were selected by searching for full text based on the inclusion criteria (Table 3) and nineteen articles excluded from different databases as duplicates. Thirty-seven articles were retained by the method and subsequently taken into consideration for the final analysis (Figure 1).

2.1.5 Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clark's six phases (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Familiarization with the data was achieved through repeated reading of the included full texts. Deductive initial codes, based on prior literature (e.g., Faculty unavailability), were applied to the data, while additional codes were developed inductively as new insights emerged. Related codes were organized into broader themes (e.g., Faculty Aspects) and reviewed for coherence. Themes were subsequently defined, refined, and reported, ensuring a systematic and rigorous analytic process. Visual representations of codes and themes were generated using MAXQDA (VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany) and Microsoft Paint.

2.2 Results (Theme areas: challenges and opportunities)

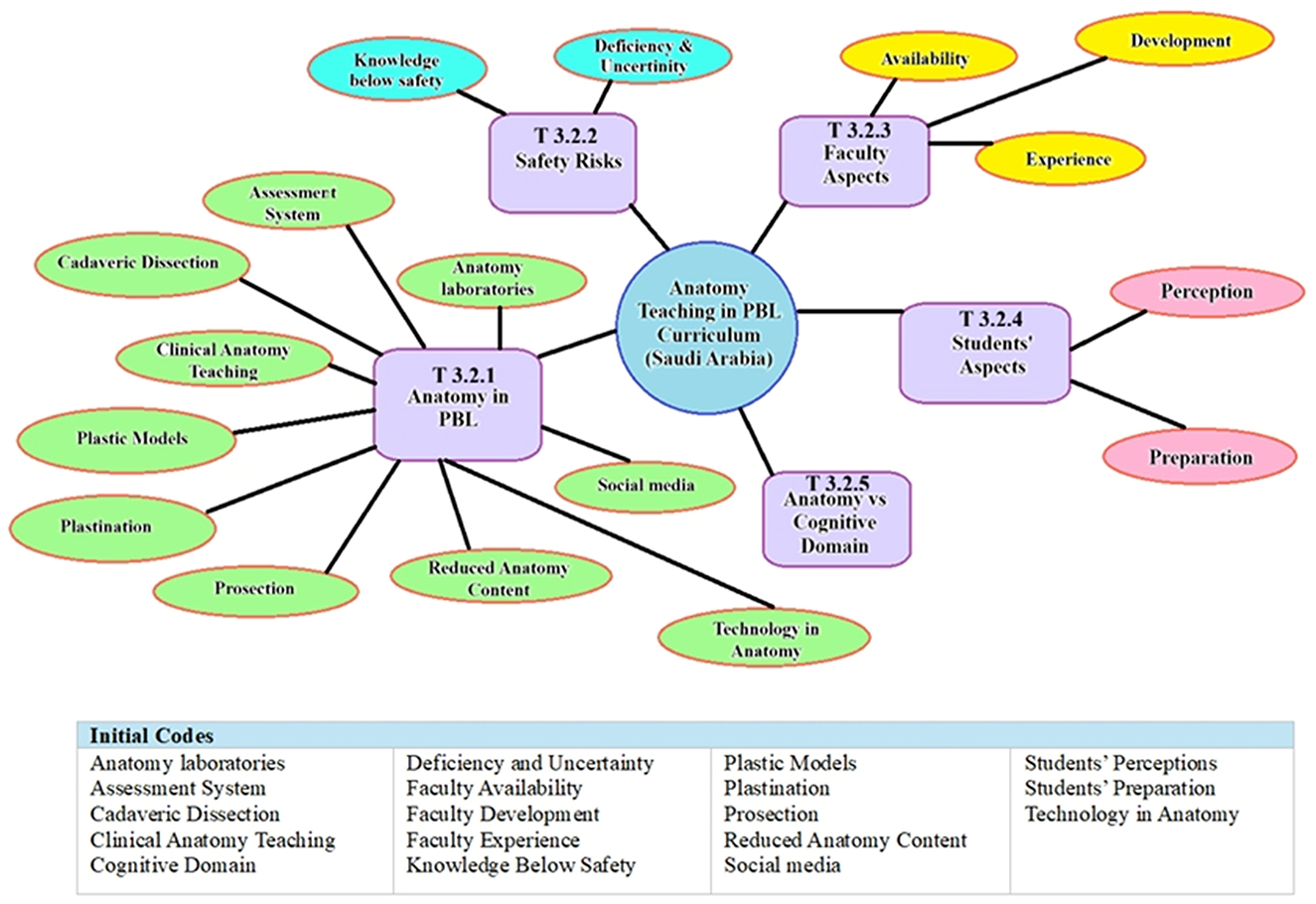

The following five themes were identified from the reviewed literature: anatomy in PBL, Safety at Risk, Faculty Aspects, Student Aspects, and Anatomy vs. Cognitive Domain in PBL. Each theme represented an independent analytical category that emerged from the data and presented separately to maintain conceptual clarity. The themes reflected distinct dimensions of anatomy teaching within the PBL context. This structural organization aimed to highlight the diversity of findings while ensuring smoother comprehension of each thematic area.

The thematic analysis produced a range of subthemes that reflected both anticipated and emerging patterns in the data. Initial deductive codes were expanded through inductive coding to capture the novel insights, leading to the development of higher-order categories. The thematic map illustrates the major themes and subthemes derived from this process (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Thematic map showing the major themes generated from the initial deductive codes during thematic analysis.

Higher-level latent themes were generated to capture underlying meanings (e.g., Anatomy needs Anatomists) (Figure 3). This hybrid inductive-deductive approach allowed both the incorporation of existing theoretical perspectives and the emergence of novel interpretations from the data (Braun and Clarke, 2019).

Figure 3. Conceptual framework showing the latent inductive codes with interconnections among the identified themes in relation to anatomy teaching within a PBL curriculum.

2.2.1 Anatomy in PBL

2.2.1.1 Reduced anatomy content

The switch to PBL has drastically reduced the amount of time spent teaching in anatomy in Saudi Arabia with a large variation of hours (89–388) in PBL while (30–140) in lectures, raised concerns about whether learning objectives were being met (Abualadas and Xu, 2023; Akeel, 2021; Bolla and Saffar, 2022). Students' understanding of fundamental concepts and their clinical application were reduced by this marginalization observed worse during COVID-19. Some reports also noted that decreased emphasis on anatomy during preclinical years coincided with reduced confidence among students during later clinical training (Kemeir, 2012; Potu et al., 2013; Yammine, 2014; Ahmad et al., 2021).

2.2.1.2 Clinical anatomy teaching

Several studies reported that PBL enhanced the acquisition of clinical anatomy through the utilization of clinical cases in problem solving, effectively integrating radiology and pathology to enhance motivation and clinical reasoning skills (Bandyopadhyay and Biswas, 2017; Nyemb, 2017; Şişu et al., 2024). Students in Saudi Arabia using problem-based learning methodology demonstrated enhanced clinical performance and greater self-assurance in the use of medical tools (Al Ansari et al., 2021). Vertical integration of anatomy throughout medical curriculum recommended by many students (Yousaf, 2023).

2.2.1.3 Cadaveric dissections

Despite its established role, the cadaveric dissection in Saudi Arabia has been diminishing due to factors such as limited availability, cultural & legal considerations, and a reduction in allocated curriculum time from 6 to 153 h across different institutions (Bolla and Saffar, 2022; Aboregela et al., 2024). Although over half (53%) of the students expressed a preference for dissection to enhance their understanding and skills, its availability was limited to only ten institutions with certain specialties lacking it altogether (Kemeir, 2012; Hegazy, 2015).

2.2.1.4 Prosection

Prosection involving the use of pre-dissected specimens, a prevalent method in Saudi Arabia medical colleges particularly in settings where cadaveric dissection is not feasible. Reported advantages included visual clarity and structured demonstration of anatomical relationships (Bolla and Saffar, 2022; Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023). while several studies noted its limitations in providing tactile, hands-on experience (Youssef, 2021).

2.2.1.5 Plastination

Plastinated specimens were favored as durable, odorless, and reusable resources in anatomy education due to their practicality and clarity in aiding structural recognition and clinical correlation (Atwa et al., 2021). In a Saudi Arabian study focusing on PBL methodology, students expressed 39.2% preference for plastinated specimens due to their practical application and 34% for distinguishing different anatomical structures (Bin Abdulrahman et al., 2021; Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023).

2.2.1.6 Plastic models

Studies from Saudi institutions indicated that 3D printed and commercially available plastic models served as supplementary tools in anatomy learning. Students acknowledged their potential to aid in memory retention, they generally rated these models to be less stimulating compared to cadaveric dissection for realism and engagement (Atwa et al., 2021; Abdellatif et al., 2022; Şişu et al., 2024). Students did not consider them a complete substitute for the experiential learning provided by cadaveric dissection (Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023).

2.2.1.7 Technology in anatomy

Multiple studies highlighted increased incorporation of digital resources such as virtual reality and anatomage tables, enhancing the visualization of intricate anatomical structures. In Saudi Arabia, approximately 41% of students across three colleges reported using Anatomage tables, primarily to compensate for limited access to cadavers (Abdellatif et al., 2022; Adnan and Xiao, 2023; Aboregela et al., 2024). Evidence on the pedagogical impact of these technologies, however, remains varied in the reviewed literature.

2.2.1.8 Anatomy laboratories

Laboratory sessions typically scheduled in conjunction with related subjects, served to reinforce learning through small group interactions and the development of practical skills. Students generally regarded this session as valuable opportunities for clarifying concepts and gaining hands-on experience, although the duration of lab sessions varied across different institutions (Azer et al., 2013; Memon et al., 2020; Abdalla, 2023).

2.2.1.9 Assessment system

In Saudi Arabia's problem-based learning medical curriculum, assessments including essays, multiple choice questions (MCQs) and objective structured practical examinations (OSPE) employed to evaluate various learning domains (Abdellatif et al., 2022). Assessment encompassed both formative and summative evaluations designed according to bloom's taxonomy serving to motivate students and monitor their academic progress. Research indicated that students in PBL curriculum frequently achieved higher outcomes compared to their counterparts in traditional programs; however, certain assessments may not have provided exhaustive coverage of the subject matter specifically anatomy (Bergman et al., 2013; Memon et al., 2020; Abdellatif et al., 2022;).

2.2.1.10 Social media

Social media platforms, particularly YouTube, were frequently used for informal anatomy education and networking purposes. Studies reported 87.7% of students in Saudi Arabia using social media for learning. Several studies mentioned ethical concerns related to the sharing of cadaveric images on social media and noted that such practices could distract from intended learning objectives (Moran, n.d.; Alsuraihi et al., 2016; Hennessy et al., 2020). Research conducted in Saudi Arabia reported 95.8% of participants finding social media helpful for anatomy study, while 40% considered it as a source of distraction (Alsuraihi et al., 2016; Alanzi and Alshahrani, 2018).

2.2.2 Safety at risk

2.2.2.1 Knowledge below safety

Studies reported that reduction in anatomy teaching hours and the fragmented nature of PBL methodologies may have jeopardized the development of safe clinical practices. Research indicated that a significant number (60%) of Saudi students and clinicians perceived their anatomy education as inadequate, which raised concern about the preparedness of future graduates (Hegazy, 2015; Almizani et al., 2022).

2.2.2.2 Deficiency and uncertainty

In several studies the phenomenon of clinical students experiencing memory lapses in anatomy resulting in heightened anxiety and uncertainty during medical procedure, has been observed. Despite the incorporation of problem-based learning, students encountered difficulties in effectively applying anatomical knowledge within clinical contexts (Kemeir, 2012; Bergman et al., 2013; Bolla and Saffar, 2022).

2.2.3 Faculty aspects

2.2.3.1 Faculty availability and experience

The scarcity of faculty and deficiency of clinically experienced anatomist in PBL environments with low professor to student ratio at several Saudi medical colleges presented obstacles to anatomy teaching (Telmesani et al., 2011). Instructors accustomed to traditional methods frequently lacked expertise in PBL (Hegazy, 2015; Yaqinuddin et al., 2016; Abdellatif et al., 2022; Salih et al., 2023).

2.2.3.2 Faculty development

Faculty preparation has been a major problem because future academics frequently come from traditional systems. Continuous faculty development in PBL pedagogy, digital teaching methodologies, and clinical anatomy was essential (Masoud et al., 2025). Efforts to recruit and train faculty to satisfy curriculum needs had been underway since 2004 (Hassanien, 2018; Algahtani et al., 2020; Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023; Yousaf, 2023).

2.2.4 Students aspects

2.2.4.1 Students' preparation for English language

The shift from conventional teacher centered instruction to the active learning approach of PBL presented difficulties, particularly when English served as the instrumental medium. While students received an initial orientation course to active learning methodologies, language obstacles and adaptation challenges remained persistent (Telmesani et al., 2011; Hassanien, 2018; Alothman and Tombs, 2024; Salih et al., 2024).

2.2.4.2 Students' perceptions

Many Saudi students acknowledged the effectiveness of PBL in integrating scientific disciplines and promoting critical thinking (Al-Shaikh et al., 2015), they also reported challenges such as extensive content, difficulties in anatomical visualization, and inconsistent facilitation (Bergman et al., 2013). Some students perceived PBL as a time-intensive approach that inadequately prepared them for examinations necessitating factual recall (Abdellatif et al., 2022; Alrashid et al., 2022; Şişu et al., 2024).

2.2.5 Anatomy vs. cognitive domain in PBL

The reviewed literature indicated that students perceived reduced emphasis on factual anatomical knowledge in problem-based learning. Several studies reported that professional behavior and communication skills have taken precedence over the acquisition of factual anatomical knowledge. Furthermore, numerous students indicated their limited enhancements in problem-solving skills and a reliance on e memorization-based learning (Kemeir, 2012; Potu et al., 2013; Nyemb, 2017; Bolla and Saffar, 2022).

2.3 Discussion

This review observed for the first time, anatomy education in Saudi Arabian PBL medical programs focusing on challenges and opportunities related to decreased anatomy content, clinical integration, resources availability, faculty and student experiences. Although PBL fosters student centered and clinically relevant education, it is crucial to uphold fundamental anatomy content, enhance faculty competence, and ensure instructional alignment with safe clinical practices.

2.3.1 Reduced anatomy content in PBL

In PBL curricula, anatomy education has undergone considerable changes, most notably a decrease in dedicated teaching time because of integrated student-centered pedagogical strategies (Abdellatif et al., 2022). This reduction is also noticeable in Saudi Arabia which results in deficiencies in comprehension and student dissatisfaction (Saikarthik, 2023). The increased emphasis on genetics in PBL medical curricula in Saudi Arabia driven by higher rates of consanguinity often diminishes the focus on anatomical knowledge (Bin Abdulrahman et al., 2022). Globally similar trends seen as curricula expanded to include subjects like genetics, ethics, and communication skills (Abualadas and Xu, 2023). Survey by Almizani et al.' (2022) reveals a common perception that medical students' anatomy understanding is inadequate, raising concern about patient safety due to lack of fundamental anatomical knowledge. This aligns with the outcomes of an earlier investigation which indicated that anatomy learning objectives were not included in certain modules in a Malaysian medical college (Potu et al., 2013). Empirical evidence suggests that insufficient exposure to anatomical topics, such as cardiac anatomy in preclinical years can negatively impact clinical performance as highlighted in the work of (Almizani et al. 2022) where most students expressed a desire for increased anatomy instruction during both preclinical and clinical training years. Hence inadequate anatomical knowledge correlated with clinical errors leading to increased medical legal claims (Yammine, 2014). Conversely proponents of PBL suggest that its integrated self-directed format enhances knowledge retention and learner motivation (Al Ansari et al., 2021; Alrashid et al., 2022). Nonetheless the integration of learning experiences cannot function as a substitute for the systematic and iterative exposure to anatomy that is crucial for ensuring safe clinical practice. The vertical integration of anatomy throughout the entirety of the curriculum is of paramount importance to address these deficiencies in an effective manner.

2.3.2 Clinical integration helps but gaps remains

The integration of anatomy into clinical scenarios within PBL curriculum has shown to enhance student motivation and facilitate a deeper understanding of anatomical concepts. I frequently use case studies and clinical images to demonstrate real world use of anatomy in my lectures and lab sessions. Similar findings are seen in studies by (Nyemb 2017) where students' participation increased by directly linking anatomical principles to relevant clinical contexts. However, PBL curricula often encounter difficulties such as disjointed and inconsistent anatomic content across modules in semesters which results in a superficial understanding. In these courses, embryology is commonly less emphasized (Abdellatif et al., 2022; Bergman et al., 2013). In contrast to traditional curricula that systematically integrate region-based instruction in gross anatomy, histology and embryology (Potu et al., 2013). Similarly, embryology has been frequently under-represented in PBL curricula in Saudi Medical colleges. Another study in Saudi Arabia indicated that 88.4% of students recognized the importance of anatomy for clinical competency however only 19.9% of clinical educators believe students were adequately prepared upon entering clinical settings this discrepancy underscores a potential deficiency in current anatomy education relative to clinical expectations (Almizani et al., 2022). Although some argue that reducing emphasis on anatomy allows for greater focus on clinical reasoning and other skills, a deep understanding of anatomy remains crucial for ensuring patient safety across all medical specialties (Ahmad et al., 2021). Integrating anatomy vertically throughout medical training reinforces its relevance and promotes lasting comprehension during clinical practice (Hegazy, 2015; Yaqinuddin et al., 2016). In a study in Saudi Arabia, (Almizani et al. 2022) emphasized on vertical integration of anatomy into PBL curriculum, beginning in the first year and continuing through the specialty training and clerkship. While in other studies anatomy education transitioned from front loaded approach to a spiral curriculum, revisiting anatomical concepts with increasing complexity through well-coordinated modules and clearly defined clinical learning objectives (Potu et al., 2013; Akeel, 2021). The integration of spiral curricula alongside diverse assessment methods serves to improve knowledge recall and enhance clinical application (Bergman et al., 2013). Employing these strategies with cadaveric exposure in labs during clinical years in regular anatomy reviews can enhance knowledge retention and its practical application (Hegazy, 2015; Almizani et al., 2022). To remediate identified deficiencies institutions should integrate targeted enhancement sessions concise dissection exercise reviews led by subject matter experts and hands-on activities explicitly aligned with PBL objectives.

2.3.3 Anatomy needs anatomists: the crisis of expertise in PBL curriculum

The efficacy of anatomy teaching within PBL curricula is significantly influenced by the availability of expert faculty which presents a considerable challenge in Saudi Arabia due to the rapid expansion of medical qualities and increasing student enrollment that outpaces the supply of qualified anatomists (Yaqinuddin et al., 2016; Hassanien, 2018). Similar studies by (Abdellatif et al. 2022) identified that anatomy departments globally rely on a appropriate number of professionals to facilitate comprehensive education in disciplines like surgery and radiology. Several factors impede effective anatomy teaching within problem-based learning curricula in Saudi Arabia. These include limiting teaching time scarcity of qualified instructors and gender segregated instruction policies that restrict the allocation of female educators with PBL expertise. Most of the faculty members accustomed to traditional lecture-based methods are resistant to adopting interactive PBL facilitation preferring lectures for their convenience (Abdel Hamid, 2017; Alothman and Tombs, 2024). Furthermore, the quality of anatomy education compromised when instructors from other disciplines lacking comprehensive anatomical expertise delivered the content. This is especially problematic in PBL contexts where precise guidance is essential (Yousaf, 2023). This deficit results in compromised or superficial anatomical knowledge thereby affecting clinical skills and the quality of patient care evidence suggests that inadequate comprehension of that means associated with increased surgical errors and diagnostic inaccuracies (Pandurangam and Gurajala, 2023). Therefore, comprehensive faculty development programs are crucial for academy education within PBL context. These initiatives should integrate interactive student-centered approaches with established procedures through workshops, cadaver sessions, case-based seminars, small group facilitation, and the interdisciplinary course design (Al Shawwa, 2012; Algahtani et al., 2020). Integrating junior and senior faculty through collaborative initiatives and mentorship programs can help to address knowledge gaps and strengthen the relevance of clinical applications via vertical integration throughout preclinical and clinical training (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). A study conducted by (Algahtani et al. 2020) in six Saudi universities involving faculty members shown the result that Faculty development Program ought to be designed to help achieve their unique teaching, scholarship, and leadership objectives. Sustaining these initiatives requires that institutional policies guarantee adequate funding for training, resources and technology (Memon et al., 2020). The establishment of a standardized national faculty development program focusing on anatomy education is crucial for ensuring quality (Algahtani et al., 2020). Further studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of the outcomes of faculty development programs on student performance.

2.3.4 Anatomy learning: from touch-to-touch screens in PBL curriculum

The characteristic reform of medical curriculum in Saudi Arabia's PBL framework has been the shift from traditional cadaveric based “touch” anatomy education to digital “touch screen” based learning resources. Digital resources that facilitate self-directed learning and spatial comprehension include plastinated specimen, 3D simulation, and virtual dissection tables (Bin Abdulrahman et al., 2021; Saikarthik, 2023). These modalities are particularly helpful in situations where logistical and cultural limitations restrict access to cadavers (Aboregela et al., 2024). Hesitant learners are encouraged to participate by plastinated specimens which are renowned for their durability and order lessness (Atwa et al., 2021). The tactile and spatial learning provided by cadaveric dissection, however, cannot be fully replicated by digital tools (Abdellatif et al., 2022; Şişu et al., 2024). As confirmed by more than 86% of Saudi students (Aboregela et al., 2024; Alghamdi et al., 2024), cadaveric dissection is still crucial for deep learning and professional identity. Although procedural learning is improved by expert guiding VR and anatomy technologies, students cite drawbacks including decreased realism and technical difficulties (Şişu et al., 2024).

Social media networks have become informal but powerful resources for studying anatomy, much like alternate digital tools. The accessibility and visual content of social media, especially YouTube, allow learning anytime and anywhere perfect for today's touchscreen Gen. Z, as reported 93% of Saudi students utilize social media. However, questions are raised concerning the ethical sharing of cadaveric material and authenticity of its content (Alsuraihi et al., 2016; Hennessy et al., 2020). Using carefully chosen, expert approved information, and upholding digital professionalism are the best practices for social media use in anatomy learning.

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies presents opportunities for self-study learning. AI driven tools in anatomy can dynamically visualize intricate systems such as basal ganglia networks or embryological development turning passive review into active involvement successful AI integration necessitates students' preparation to use AI in clinical practice faculty digital literacy and curriculum adoption (Abdellatif et al., 2022). Digital innovations should serve to augment rather than replace traditional cadaveric dissection within a balanced and ethically informed PBL framework.

2.3.5 A silent obstacle: to shape anatomy in PBL curriculum

A frequently neglected challenge in Saudi medical education is the linguistic barrier encountered when studying intricate subjects like anatomy in English a non-native language for most students. Research suggests that learning in a second language can impede cognitive processes crucial for PBL including critical thinking and problem solving (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). However, there is a scarcity of research on how learning in a second language influences understanding involvement and knowledge retention within the context of Saudi medical education (Telmesani et al., 2011). In Saudi Arabia despite a preparatory year aimed at enhancing English proficiency prior to commencing PBL curricula students continue to face challenges in grasping anatomical concepts primarily because English the language of instruction is not their native language (Telmesani et al., 2011; Masoud et al., 2025). Most students enter medical programs from general secondary education with inadequate preparation in both biomedical sciences and English complicating their comprehension and engagement in PBL activities (Telmesani et al., 2011). Instructors frequently note that students in PBL sessions are often hesitant to participate due to a limited English vocabulary and fear of errors (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). Therefore, the interactive dynamics of PBL are often compromised by students' limited English proficiency. My experience indicates that students with weaker English skills tend to avoid asking questions or actively participating in clinical case discussions which adversely affect their understanding of concepts and performance in examination. These challenges extend to interpreting clinical scenarios and formulating responses during OSPE (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). Faculty surveys with an average rating of 3.7 out of 5, indicate that English language proficiency poses a substantial obstacle to Saudi student learning (Hassanien, 2018). The shift from traditional teacher centered instruction to a student-centered PBL model delivered in English heightens the cognitive demands on student (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). Although PBL is associated with gains in autonomy and self-directed learning, its effectiveness can be attenuated by language barriers (Azer et al., 2013). Research demonstrates a significant correlation between English language skills and academic achievement occuring among medical students in Saudi Arabia (Alothman and Tombs, 2024). To enhance understanding and alleviate cognitive burden certain educators suggest integrating Arabic into the initial stages of medical education (Telmesani et al., 2011). While transitioning to Arabic language reresources and faculty training would necessitate resource allocation, it prompts critical inquiries into harmonizing pedagogical approaches with student linguistic background.

2.3.6 Recommendations

2.3.6.1 Standardize core curriculum

A standardized core anatomy curriculum needs to be implemented across medical education to guarantee that all graduates possess the fundamental anatomical knowledge necessary for clinical competency and patient safety.

2.3.6.2 Enhance faculty development

Augment targeted faculty training in PBL curricula, digital pedagogical tools, and clinical anatomy, to deepen subject matter expertise and improve the quality of teaching and learning.

2.3.6.3 Overcome language barriers

Implement dual language instructional techniques early in medical programs incorporating essential anatomical terminology in both students' native language and English this should be facilitated by educators proficient in linguistic responsiveness.

2.3.6.4 Lead through collaboration and innovation

Professional anatomy organizations such as Saudi association for anatomical sciences (SAAS) should advocate for the vertical integration of anatomy, support research into innovative tools like AI and encourage partnerships between institutions and international collaborators to improve standards in anatomy education globally. By employing these approaches medical educators worldwide can foster anatomy education that is clinically relevant, inclusive, and adaptable to the changing educational environment.

2.4 Limitations

This review is subject to certain limitations. The inclusion of only English language studies may have resulted in the omission of pertinent research published in Arabic or other languages. Furthermore, the concentration of resources from a restricted number of institutions may not fully represent the heterogeneity of medical colleges across Saudi Arabia. This review's reliance on previously published data, without incorporating new empirical research, restricts the scope of its general applicability. The varied foci of the included studies, some concentrating solely on faculty perspectives while others involving students, coupled with differences in participant demographics, further complicate the ability to draw comparisons. These considerations underscore the necessity for future investigations that are more standardized, inclusive, and methodically sound. Although this review has limitation it provides a thorough overview of anatomy education in Saudi Arabia's PBL curricula. By bringing together different viewpoints from institutions and focusing on important topics like anatomy content, clinical integration, technology use, problems faced by faculty and students and language barriers, it offers useful information and practical suggestions for improving anatomy education.

2.5 Conclusion

The integration of anatomy education into Saudi Arabia's PBL curriculum presents notable advantages such as fostering learner autonomy and enhancing clinical relevance. However, it also encounters substantial challenges, including the potential for reduced coverage of core anatomical content, faculty limitations, inconsistencies in curriculum integration, and significant linguistic obstacles for students. Tackling these challenges through strategies such as vertical curriculum integration, focused faculty training, and bilingual support, is crucial. Enhancing anatomy education is vital for adequately preparing future physicians for secured clinical practice, thereby aligning medical education with national healthcare objectives and the aspirations of Saudi vision 2030.

Author contributions

NK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research funded by “The Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University (KFU), Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia” with the Grant Number KFU254191.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge “The Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University (KFU), Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia” for their support in covering the costs of publication for this research paper. The author acknowledges ChatGPT to help standardize journal name's abbreviations and format references. The manuscript was written and analyzed without the aid of AI.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1686355/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

SAAS, Saudi Association for Anatomical Sciences; OSPE, Objective structured practical exams; PCC, population, concept and context; GenAI, generative artificial intelligence; MCQ, multiple choice questions; PBL, problem-based learning; KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; AI, artificial intelligence; 3D, three-dimensional; VR, virtual reality.

References

Abdalla, A. M. E. (2023). Medical Students satisfaction and performance towards implementation of Anatomy laboratory guide in a discipline-based curriculum. Bahrain Med. Bull. 45, 1452–1459. Available online at: https://www.bahrainmedicalbulletin.com/June2023/BMB-23-399.pdf

Abdel Hamid, G. A. (2017). Problem-based learning facilitates vertical integration of basic and clinical sciences in medical curriculum. MOJ Anat. Physiol. 3, 110–111. doi: 10.15406/mojap.03.00096

Abdellatif, H., Al Mushaiqri, M., Albalushi, H., Al-Zaabi, A. A., Roychoudhury, S., Das, S., et al. (2022). Teaching, learning and assessing anatomy with artificial intelligence: the road to a better future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:14209. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114209

Aboregela, A. M., Khired, Z., Osman, S. E. T., Farag, A. I., Hassan, N. H., Abdelmohsen, S. R., et al. (2024). Virtual dissection applications in learning human anatomy: international medical students' perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 24:1259. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-06218-z

Abualadas, H. M., and Xu, L. (2023). Achievement of learning outcomes in non-traditional (online) versus traditional (face-to-face) anatomy teaching in medical schools: a mixed method systematic review. Clin. Anat. 36, 50–76. doi: 10.1002/ca.23942

Adnan, S., and Xiao, J. (2023). A scoping review on the trends of digital anatomy education. Clin. Anat. 36, 471–491. doi: 10.1002/ca.23995

Ahmad, K., Khaleeq, T., Hanif, U., and Ahmad, N. (2021). Addressing the failures of undergraduate anatomy education: dissecting the issue and innovating a solution. Ann. Med. Surg. 61, 81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.12.024

Akeel, M. A. (2021). Exploring students' understanding of structured practical anatomy. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 16, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.12.006

Al Ansari, M., Al Bshabshe, A., Al Otair, H., Layqah, L., Al-Roqi, A., Masuadi, E., et al. (2021). Knowledge and confidence of final-year medical students regarding critical care core-concepts, a comparison between problem-based learning and a traditional curriculum. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 8:2382120521999669. doi: 10.1177/2382120521999669

Al Shawwa, L. (2012). The establishment and roles of the medical education department in the faculty of medicine, king Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah Saudi Arabia. Oman Med. J. 27, 4–9. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.02

Alanzi, T. M., and Alshahrani, B. (2018). Use of social media in the department of radiology at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 11, 583–589. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S175440

Algahtani, H., Shirah, B., Subahi, A., Aldarmahi, A., and Algahtani, R. (2020). Effectiveness and needs assessment of faculty development programme for medical education: experience from Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 20, e83–89. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2020.20.01.012

Alghamdi, M. A., Bu Saeed, R., Fudhah, W., Alqarni, D., Albarzan, S., Alamoudi, S., et al. (2024). Perceptions of medical students regarding methods of teaching human anatomy. Cogent Educ. 11:2340836. doi: 10.1080/2332024.2340836

Almagribi, A. Z., Al-Qahtani, S. M., Assiri, A. M., and Mehdar, K. M. (2024). Perceptions of medical students at Najran University on the effectiveness of problem-based learning and team-based learning. BMC Med. Educ. 24:1150. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-06148-w

Almizani, M. S., Alotaibi, M. A., Bin Askar, M. F., Albaqami, N. M., Alobaishi, R. S., Arafa, M. A., et al. (2022). Clinicians‘ and students' perceptions and attitudes regarding the anatomical knowledge of medical students. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 13, 1251–1259. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S370447

Alothman, S., and Tombs, M. (2024). Identification of the challenges teachers face in teaching small problem-based learning (PBL) groups in the College of Medicine, King Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. MedEdPublish 14:63. doi: 10.12688/mep.20163.1

Alrashid, F. F., Khalifah, E. M., Alshammari, K. F., Alenazi, F. S., Alqahtani, A. S., Alshmmri, M. A., et al. (2022). Medical students‘ perception towards recently introduced problem-based learning in surgery module: a case of university of Ha'il. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 16, 583–587. doi: 10.53350/pjmhs22162583

Al-Shaikh, G., Al Mussaed, E., Almofeed Altamimi, T., Elmorshedy, H., Syed, S., Habib, F., et al. (2015). Perception of medical students regarding problem based learning. Kuwait Med. J. 47, 133–138. Available online at: https://applications.emro.who.int/imemrf/Kuwait_Med_J/Kuwait_Med_J_2015_47_2_133_138.pdf

Alsuraihi, A. K., Almaqati, A. S., Abughanim, S. A., and Jastaniah, N. A. (2016). Use of social media in education among medical students in Saudi Arabia. Korean J. Med. Educ. 28, 343–354. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2016.40

Atwa, H., Dafalla, S., and Kamal, D. (2021). Wet specimens, plastinated specimens, or plastic models in learning anatomy: perception of undergraduate medical students. Med. Sci. Educ. 31, 1479–1486. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01343-6

Azer, S. A., Hasanato, R., Al-Nassar, S., Somily, A., and AlSaadi, M. M. (2013). Introducing integrated laboratory classes in a PBL curriculum: impact on student's learning and satisfaction. BMC Med. Educ. 13:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-71

Bandyopadhyay, R., and Biswas, R. (2017). Students' perception and attitude on methods of anatomy teaching in a medical college of West Bengal, India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 11, AC10–AC14. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/26112.10666

Barbosa, M. V. J., Barbosa, A. M. D. S. J., and Duarte, S. G. (2020). Pedagogical challenges in teaching anatomy on a problem-based learning curriculum. Teach. Anat. 14, 117–122. doi: 10.2399/ana.20033

Bergman, E. M., Bruin, D. E., Herrler, A. B., Verheijen, A., Scherpbier, I. W., Van Der Vleuten, A. J. C. P., et al. (2013). Students' perceptions of anatomy across the undergraduate problem-based learning medical curriculum: a phenomenographical study. BMC Med. Educ. 13:152. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-152

Bin Abdulrahman, A. K., Aldayel, A. Y., Bin Abdulrahman, K. A., Rafat Bukhari, Y., Almotairy, Y., Aloyouny, S., et al. (2022). Do Saudi medical schools consider the core topics in undergraduate medical curricula? BMC Med. Educ. 22:377. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03452-1

Bin Abdulrahman, K. A., Jumaa, M. I., Hanafy, S. M., Elkordy, E. A., Arafa, M. A., Ahmad, T., et al. (2021). Students' perceptions and attitudes after exposure to three different instructional strategies in applied anatomy. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 12, 607–612. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S310147

Bolla, S. R., and Saffar, R. A. A. (2022). Anatomy teaching in Saudi medical colleges- is there necessity of the national core syllabus of anatomy. Anat. Cell Biol. 55, 367–372. doi: 10.5115/acb.22.041

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology'. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). ‘Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis'. Qual. Res. Sport, Exercise Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Fallatah, H. I. (2016). Introducing inter-professional education in curricula of Saudi health science schools: an educational projection of Saudi Vision 2030. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 11, 520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.10.008

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 24, 230–235. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., and Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 5, 101–117. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

Hassanien, M. (2018). Faculty members' perception towards changes in medical education in Saudi Arabia. MedEdPublish 7:23. doi: 10.15694/mep.0000023, 1.

Hegazy, M. S. A. (2015). Reflection of the type of medical curriculum on its anatomy content: trial to improve the anatomy learning outcomes. Int. J. Clin. Dev. Anat. 1:52. doi: 10.11648/j.ijcda.20150103.11

Hennessy, C. M., Royer, D. F., Meyer, A. J., and Smith, C. F. (2020). Social media guidelines for anatomists. Anat. Sci. Educ. 13, 527–539. doi: 10.1002/ase.1948

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide, South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Kemeir, M. (2012). Attitudes and views of medical students toward anatomy learnt in the preclinical phase at King Khalid University. J. Fam. Community Med. 19:190. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.102320

Masoud, I., Adam, E., Alfaifi, J., Alamri Mohannad Mohammed, S., Muffarah, H. A., Ali Eleragi, M. S., et al. (2025). Developing in situ problem-based curriculum at the university of bisha, college of medicine, Saudi Arabia. Bahrain Med. Bull. 47, 2830–2033. Available online at: https://www.bahrainmedicalbulletin.com/March_2025/BMB-24-874.pdf

Memon, I., Alkushi, A., Shewar, D. E., Anjum, I., and Feroz, Z. (2020). Approaches used for teaching anatomy and physiology in the university pre-professional program at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 44, 188–191. doi: 10.1152/advan.00167.2019

Moran, M. (n.d.). Teaching, Learning, and Sharing: How Today's Higher Education Faculty Use Social Media. Pearson.

Nyemb, P. M. M. (2017). Studying anatomy through a problem-based learning approach. MOJ Anat. Physiol. 4, 377–379. doi: 10.15406/mojap.04.00150

Pandurangam, G., and Gurajala, S. (2023). Pedagogical strategies in medical anatomy: a comprehensive review. Natl. J. Clin. Anat. 12, 216–222. doi: 10.4103/NJCA.NJCA_181_23

Periya, S. (2017). Teaching human anatomy in the medical curriculum: a trend review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 5, 445–448. doi: 10.21474/IJAR01/3830

Potu, B. K., Shwe, W. H., Jagadeesan, S., Aung, T., and Cheng, P. S. (2013). Scope of anatomy teaching in problem-based learning (PBL) sessions of integrated medical curriculum. Int. J. Morphol. 31, 899–901. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022013000300019

Saikarthik, J. (2023). Anatomy e-Learning experience in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic-a narrative review. Int. J. Morphol. 41, 1158–1165. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022023000401158

Salih, K. M., Al-Faifi, J., Alamri, M. M., Mohamed, O. A., Khan, S. M., Marakala, V., et al. (2024). Comparing students' performance in self-directed and directed self-learning in College of Medicine, University of Bisha. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 19, 696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.05.003

Salih, K. M., Elnour, S., Albaqami, A. A. S., Alaklobi, R. O., Hussein, K. E., Abbas, M., et al. (2023). Comparison between faculty members and students toward learning through problem-based learning and case-based learning in an innovative curriculum in a regional university in the KSA. Bahrain Med. Bull. 45, 1291–1294.

Şişu, A. M., Stoicescu, E. R., Bolintineanu, S. L., Faur, A. C., Iacob, R., Ghenciu, D. M., et al. (2024). Blending tradition and innovation: student opinions on modern anatomy education. Educ. Sci. 14:1150. doi: 10.3390/educsci14111150

Telmesani, A., Zaini, R. G., and Ghazi, H. O. (2011). Medical education in Saudi Arabia: a review of recent developments and future challenges. East. Mediterr. Health J. 17, 703–707. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.8.703

Trullàs, J. C., Blay, C., Sarri, E., and Pujol, R. (2022). Effectiveness of problem-based learning methodology in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 22:104. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03154-8

Yaqinuddin, A., Ikram, M. F., Zafar, M., Eldin, N. S., Mazhar, M. A., Qazi, S., et al. (2016). The integrated clinical anatomy program at Alfaisal University: an innovative model of teaching clinically applied functional anatomy in a hybrid curriculum. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 56–63. doi: 10.1152/advan.00153.2015

Yousaf, A. (2023). Anatomy in the undergraduate medical curriculum; blending the old and new. J. Rawalpindi Med. Coll. 27, 1–3. doi: 10.37939/jrmc.v27i1.2271

Keywords: anatomy, anatomy teaching, problem-based learning, problem-based learning challenges, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, medical education, Saudi Arabia universities, preclinical teaching

Citation: Kausar N (2025) Anatomy teaching in problem-based learning curriculum: challenges and opportunities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front. Educ. 10:1686355. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1686355

Received: 15 August 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025; Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Nerissa Naidoo, Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Ramy K. A. Sayed, Sohag University, EgyptLelika Lazarus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Kausar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naheed Kausar, bm11cnRhemFAa2Z1LmVkdS5zYQ==; bm11cnRhemEyMDE1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Naheed Kausar

Naheed Kausar