- 1College of Geodesy and Geomatics, Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, China

- 2College of Oceanography and Space Informatics, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China

- 3National Institute of Telecommunications (Inatel), Santa Rita do Sapucaí, Brazil

Based on the challenges of cultivating innovative talents in emerging engineering disciplines, this study addresses challenges such as low levels of student engagement and limited innovation capacity in the “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing” course. Guided by constructivist learning theory, an intelligent blended teaching model empowered by artificial intelligence and data analytics was designed and implemented. This model, structured around the 5E instructional framework, establishes a teaching closed-loop of “Engagement–Exploration–Explanation–Elaboration–Evaluation” through intelligent content delivery, human–computer collaborative teaching activities, and a data-driven feedback mechanism. A three-year quasi-experimental study involving 706 students demonstrated that the model significantly enhanced learning outcomes: the excellence rate increased from 5.1 to 11.25%, while the failure rate decreased from 8.1 to 1.44%. Moreover, it effectively stimulated students’ innovation capacity, resulting in 19 approved national-level innovation and entrepreneurship projects and 293 academic publications. This study provides a replicable theoretical and practical paradigm for the construction and application of intelligent teaching models in higher engineering education.

1 Introduction

Satellite remote sensing can efficiently acquire extensive imagery data of the Earth’s surface over a large area in a short period (Ulaby, 2018). Its efficiency surpasses that of manual ground surveys, near-earth sensing monitoring, and aerial photogrammetric measurements. With the continuous development of spatial information technology, satellite remote sensing has gradually become one of the most effective tools for observing the Earth at regional and global spatial scales.

Satellite remote sensing technology enables the acquisition of electromagnetic waves from the Earth’s surface without physical contact, allowing for the extraction of information and avoiding damage to the surfaces of objects. This non-destructive characteristic has propelled the widespread use of satellite remote sensing in resource surveys and environmental monitoring. The obtainable resource information includes land use (Zhang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022), vegetation types (Alvarez-Vanhard et al., 2020; Fauvel et al., 2020), hydrology (Huang et al., 2022), and geology (Bozzano et al., 2015). Environmental information comprises meteorological conditions (Zhang et al., 2020; Marra et al., 2017), air quality (Yan et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2023), soil moisture (Albergel et al., 2013; Babaeian et al., 2019), water quality (Castro et al., 2020), and disasters such as typhoons (Chen et al., 2022), heavy rain, drought (Xu et al., 2020), floods, earthquakes (Marchetti et al., 2019), landslides, diseases transmitted by animal vectors (Kalluri et al., 2007), microbial infections, forest fires (Chand et al., 2019; Sicard et al., 2019), and marine red tides, among others. Social scientists have also utilized satellite remote sensing datasets to visually classify targets, investigating the correlation between the 2019 coronavirus disease and various socio-economic datasets to understand its impact on global crises (Diffenbaugh et al., 2020). Satellite remote sensing technology provides technical support for urban planning, precise weather forecasting, economic and social development, and early warning of natural disasters.

The “Blue Book on the Development of Remote Sensing Applications in China (2023)” (referred to as the “Blue Book”) (China Remote Sensing Application Development Blue Book, 2023) states that as of the end of June 2023, China has launched nearly 300 remote sensing satellites of various types. Approximately 200 satellites are in orbit, supported by a comprehensive ground-based infrastructure. Significant progress has been made in remote sensing-related education, scientific research, policy measures, standards and specifications, application promotion, association organizations, and international cooperation (Yang et al., 2011). According to the “Blue Book,” there are at least 47,000 remote sensing-related enterprises in China. The industry’s scale reached 100 billion RMB in 2020 and is projected to grow to 200 billion RMB by 2025 and 500 billion RMB by 2035 (China Remote Sensing Application Development Blue Book, 2023).

To fully leverage the advantages of remote sensing technology, it is imperative to enhance the effective training of interdisciplinary and innovative talents among remote sensing professionals. The effective cultivation of talent in remote sensing technology is a pressing issue in current remote sensing courses, particularly in undergraduate courses such as “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing” (Yang et al., 2011). Currently, numerous universities nationwide offer courses related to remote sensing, and our university classrooms play a crucial role in talent development. However, some pressing issues need to be addressed regarding the focus on students’ learning needs and the implementation of the “student-centered” educational philosophy. These issues are primarily manifested in the following aspects:

• Low student engagement in the classroom: In traditional teaching methods, crucial and challenging content is often delivered to students directly in an information-heavy manner, resembling a “spoon-feeding” approach. In this scenario, students act as passive “audience members,” not actively thinking, speaking, or participating in classroom activities. The weak intrinsic motivation for independent learning results in a state of passive learning. Consequently, traditional teaching methods yield poor educational outcomes.

• Insufficient student self-learning ability: Assignments given in traditional teaching methods lack difficulty, requiring students to neither think critically nor consult reference materials to obtain answers. This situation leads to the neglect of students’ active and thoughtful learning activities. On the other hand, the knowledge imparted by teachers in the classroom has not transformed into learning resources that actively engage students. Additionally, teachers’ instructional practices do not support students developing sustained learning abilities and critical thinking behavior.

• Outdated and obsolete course content: Few teachers focus on building bridges between research projects and teaching, failing to transform cutting-edge research findings into effective course resources. When research achievements cannot be promptly integrated into meaningful classroom discussions, they fail to serve as compelling materials to ignite students’ enthusiasm for learning a subject. Consequently, students may lose motivation for independent learning, critical thinking, and active practical engagement.

• Single evaluation method: Traditional assessment methods rely on a formula such as “regular assignments (10%) + attendance scores (10%) + final exam (80%).” This quantitative approach fails to objectively and scientifically reflect students’ attitudes, initiative, accuracy, and mastery throughout the learning process. It is not conducive to fostering students’ interests and developing their learning abilities.

Science and technology have created a significant opportunity to enhance teaching efficiency greatly, and innovative educators have begun designing new teaching methods. On April 18, 2022, the Higher Education Information Technology released the “2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition,” analyzing and reflecting on the current state of higher education development while anticipating new trends in educational advancement (Liu et al., 2022). The report highlights that, driven by the development of modules such as artificial intelligence, data analytics, and blended learning, teaching models in higher education are gradually transitioning toward a “data-driven, more sustainable blended/online teaching model” (Zhang et al., 2022). With the support of technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data, this transformation is driving continuous improvement and innovation in both the practices of “teaching” and “learning” (Liu et al., 2022).

The use of artificial intelligence in education not only enhances technological capabilities but also tailors courses and feedback according to learners’ unique needs. It provides personalized learning experiences. Moreover, it can liberate teachers from routine administrative tasks, allowing them to focus more effectively on teaching. Additionally, virtual reality technology facilitates interactive, simulated scenarios for teaching, enhancing the overall learning experience. Finally, leveraging artificial intelligence, teaching data can be collected to provide information feedback through data analysis. Data analysis informs teachers, improves their digital teaching methods, and provides students with information to enhance their learning skills and behaviors (Heredia-Negrón et al., 2024). In summary, the key to innovative teaching models lies in empowering students, and information technologies based on artificial intelligence and big data can precisely assist teachers in achieving this goal. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of an intelligently designed blended teaching model in improving student learning performance, engagement, and innovation capacity. To achieve this aim, the study designed and implemented an AI and data analytics-empowered teaching model based on constructivist learning theory, which was operationalized in the Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing course using the 5E instructional framework.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Methods: constructivist learning theory

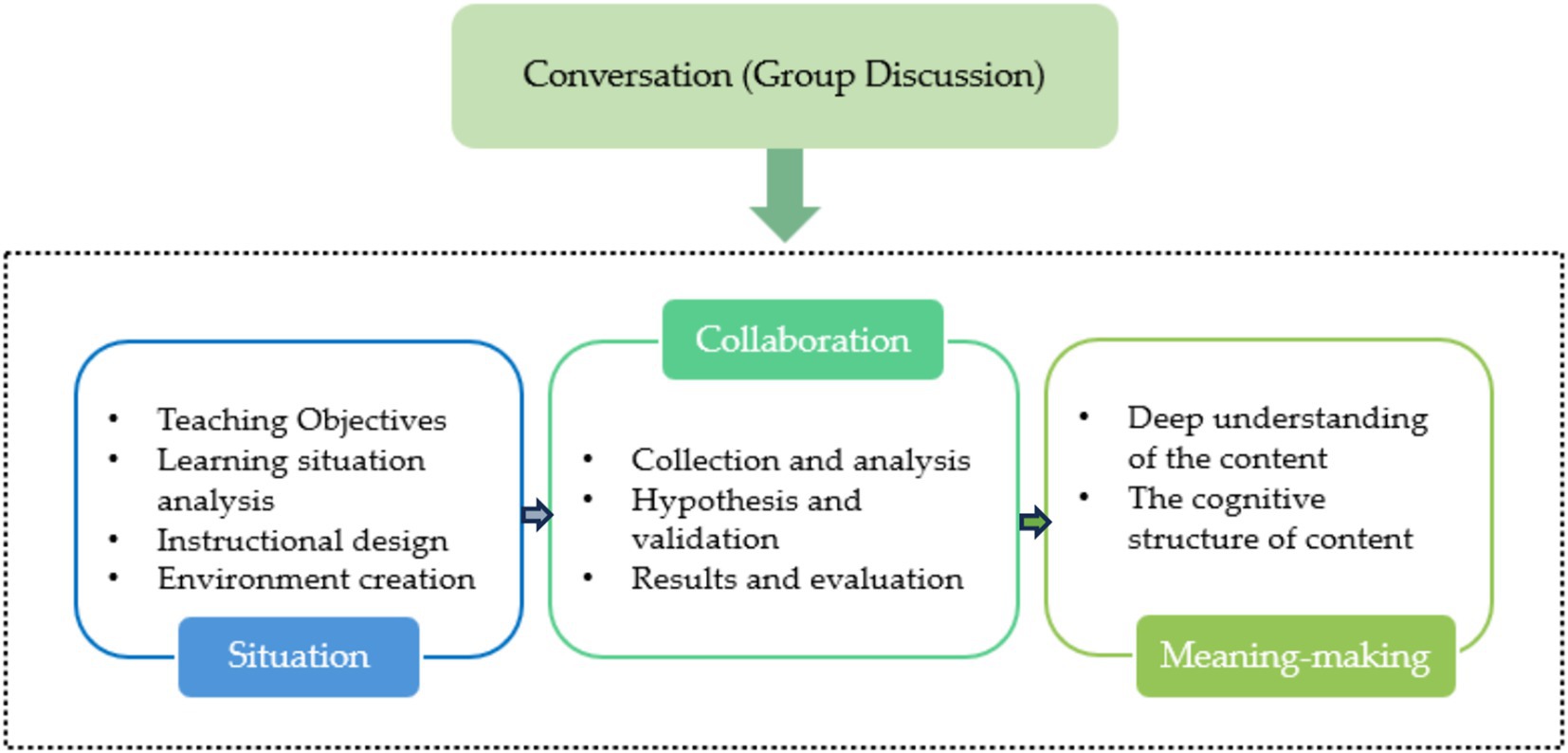

This study is grounded in constructivist learning theory, focusing specifically on the core elements that align with our instructional design: context creation, collaboration, conversation, and meaning construction. These elements directly support the inquiry-based learning activities enabled through intelligent teaching tools. While cognitive outcomes such as critical thinking may arise during learning, they are considered as results rather than theoretical foundations of this study.

The basic tenets of constructivist learning theory can be elucidated through two aspects: the “meaning of learning” (i.e., “what learning entails”) and the “methods of learning” (i.e., “how learning occurs”). Regarding the meaning of learning, constructivism posits that knowledge is not transmitted by teachers but rather constructed by learners within specific social-cultural contexts through collaborative activities (Zhao, 2001; Ren, 2002). Therefore, the theory identifies “context,” “collaboration,” “conversation,” and “meaning construction” as the four key elements or attributes within the learning environment (Figure 1).

• Context: The learning environment should facilitate students’ construction of meaning from the learning content, thereby placing new demands on instructional design. In a constructivist learning environment, instructional design should consider analyzing teaching goals and creating contexts that facilitate students’ construction of meaning. Context creation is viewed as one of the most crucial aspects of instructional design.

• Collaboration: Collaboration is integral throughout the learning process. Collaboration plays a significant role in collecting and analyzing learning materials, proposing and validating hypotheses, evaluating learning outcomes, and constructing meaning.

• Conversation: Conversation is an indispensable component of the collaborative process. Learning group members must converse to discuss plans for completing assigned learning tasks. The collaborative learning process is a conversation process, where each learner’s intellectual contributions are shared among the entire learning community. Therefore, conversation is a crucial means to achieve meaning construction.

• Meaning Construction: This is the ultimate goal of the entire learning process. Assisting students in constructing meaning during the learning process involves helping them achieve a deeper understanding of the nature and patterns of the phenomena reflected in the current learning content, as well as the inherent connections between these phenomena and others. This deep understanding contributes to the cognitive structure of the current learning content. From the above, it can be concluded that the extent of knowledge acquisition depends on the learner’s ability to construct meaning about the knowledge based on their own experiences, rather than relying on memorizing and reciting the content taught by the teacher (He, 1998).

For students to become active constructors of meaning, it is required that they play a central role in the learning process in the following aspects: (1) They should employ exploratory and discovery methods to construct knowledge; (2) During the process of meaning construction, students are expected to actively gather and analyze relevant information and data, formulate various hypotheses about the studied issues, and make diligent efforts to validate them; (3) Students should strive to connect the current learning content with what they already know and engage in serious reflection on these connections. “Connection” and “reflection” are key to constructing meaning. Suppose the processes of connection and reflection are combined with the negotiation process in collaborative learning (i.e., the process of communication and discussion), the efficiency and quality of students’ meaning construction will be enhanced.

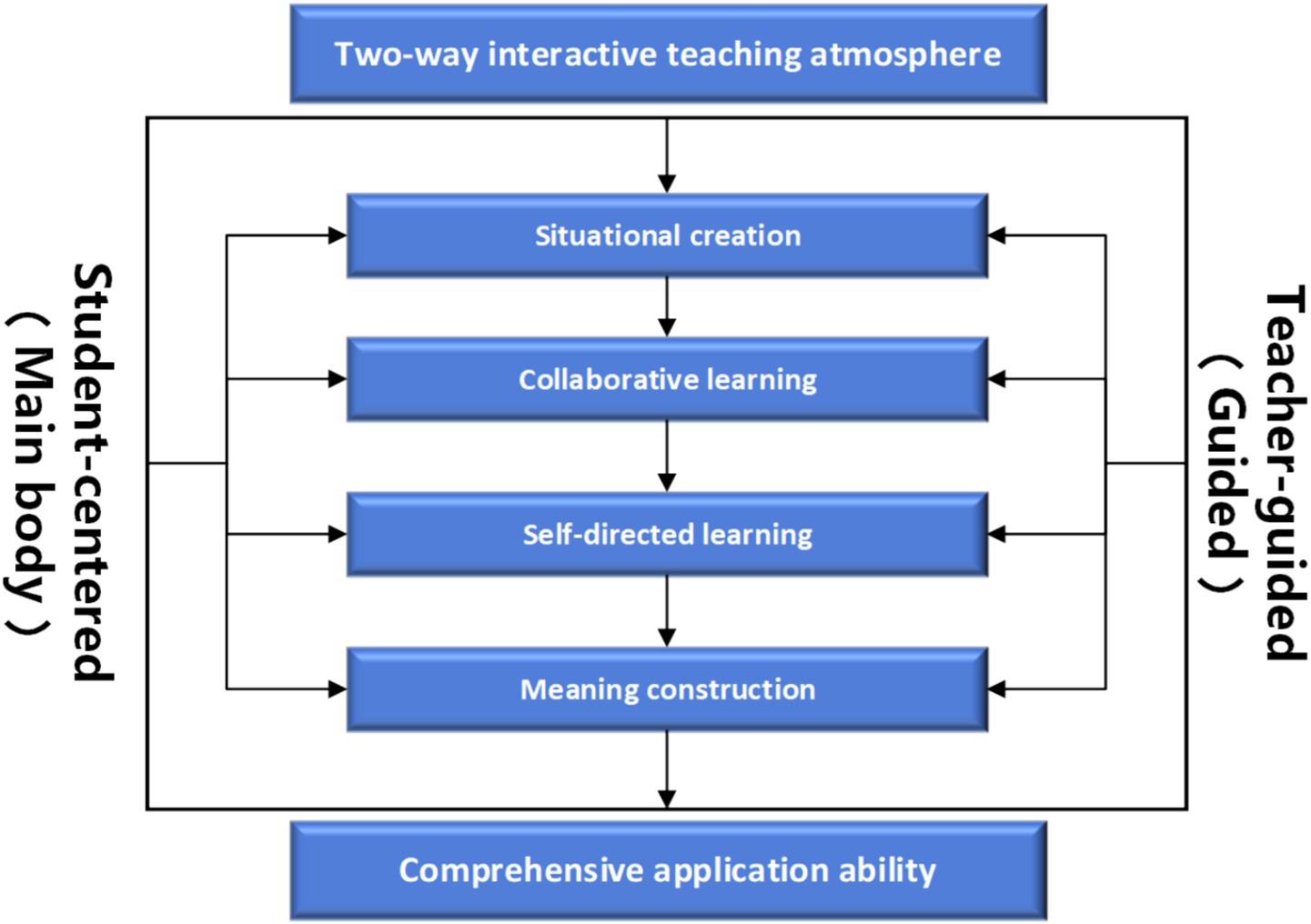

As shown in Figure 2, the teacher acts as a facilitator of students’ meaning construction and plays a guiding role in the teaching process in the following ways: (1) Ignite students’ interest in learning and help them develop a motivation for learning; (2) By creating situations and providing prompts that align with the requirements of the instructional content, assist students in constructing the meaning of the knowledge they are currently learning; (3) To make meaning construction more effective, teachers should organize collaborative learning (including discussions and exchanges) and guide the collaborative learning process in a direction conducive to meaningful construction. This ultimately aims to help students construct meaning for the knowledge they are currently acquiring. Guiding methods include inquiry-based learning, situational teaching, team-based learning (TBL), problem-based learning (PBL), and discussion-based teaching.

2.2 Materials

To fully leverage students’ agency and emphasize their active exploration, discovery, and construction of knowledge, the teaching team underscores the provision of intelligent instructional content based on artificial intelligence and digital technology. This aims to provide personalized and diverse teaching resources for students in blended learning, catering to their diverse and multi-level learning needs (Marton and Saljo, 2020).

2.2.1 Intelligent delivery of instructional content

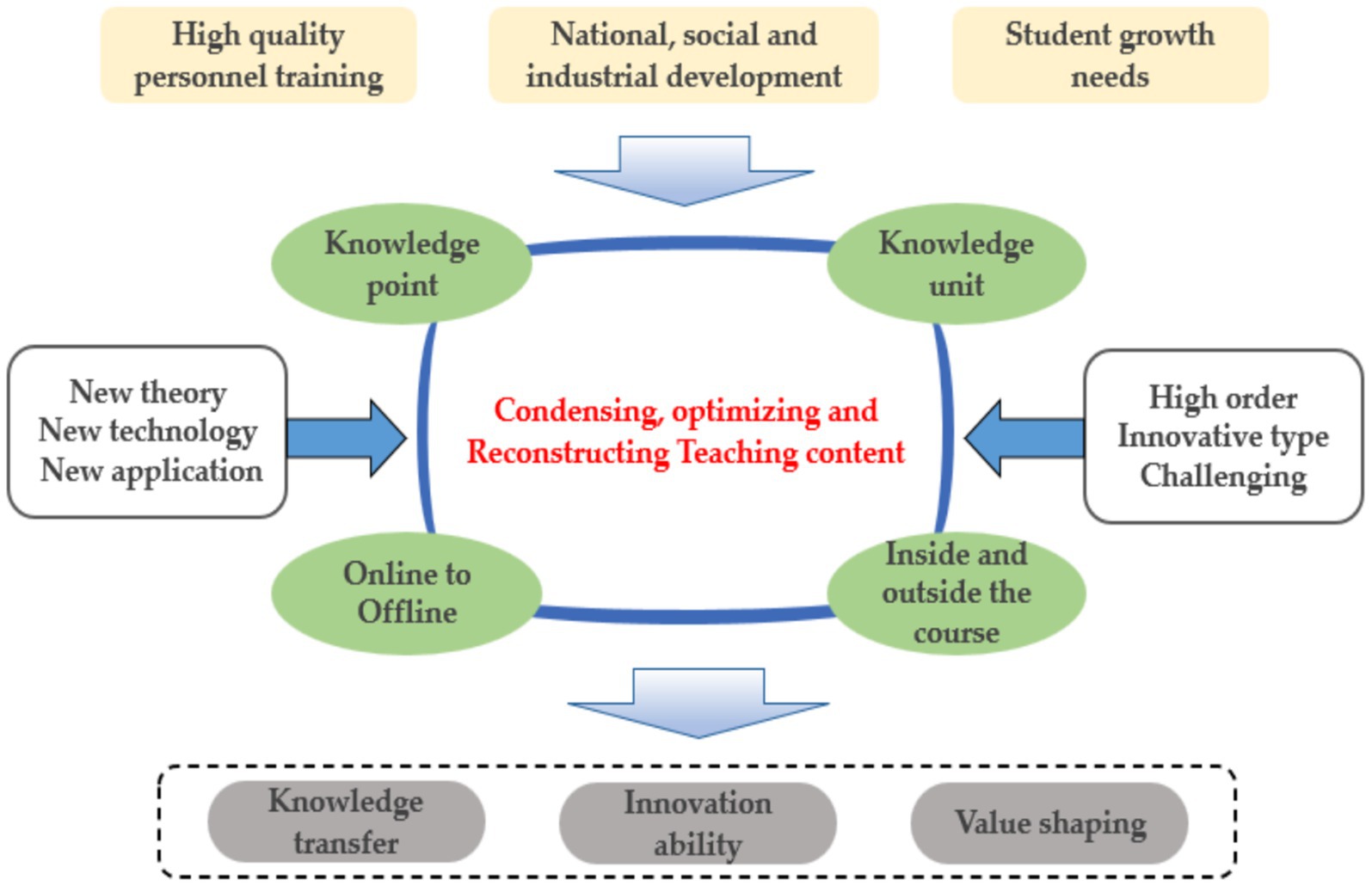

Optimizing and restructuring instructional content is a systematic endeavor where the teaching team focuses on the talent development objective of “knowledge-innovation-value.” They aim to revamp, modularize, functionalize, and compartmentalize knowledge units around core theoretical foundations and engineering issues (Bai et al., 2020). Figure 3 shows the principles for optimizing and reconstructing teaching content in this course. This includes:

1. Clarifying the relationships between knowledge points within the course itself.

2. Analyzing the connections between knowledge points in the course and those in other courses.

3. Aligning the course’s instructional content with the evolving trends in China’s surveying and geographic information industry, considering new trends in discipline development, national demands, and practical case studies.

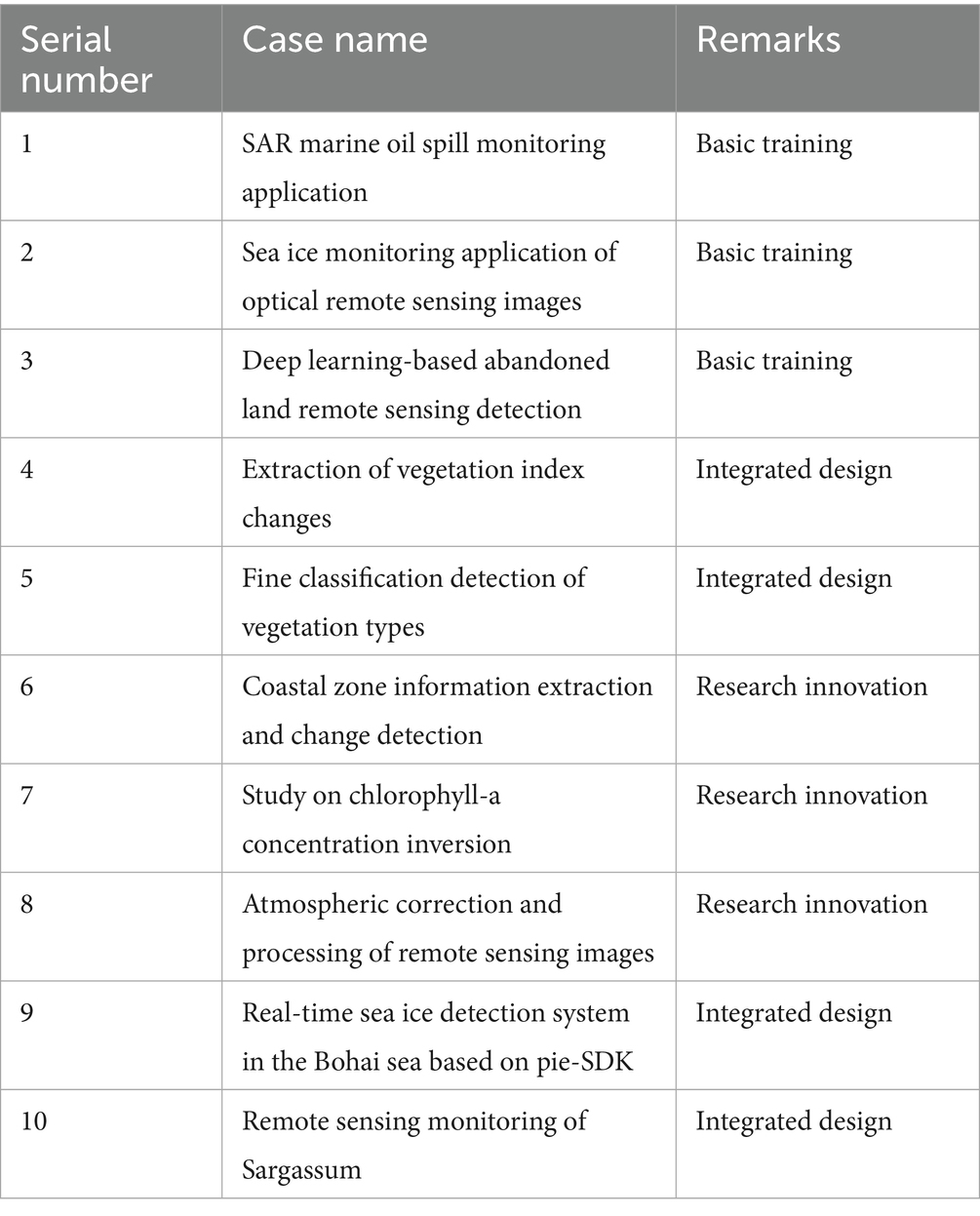

The quality of course resources is a decisive factor in the successful implementation of intelligent teaching. Therefore, the teaching team has been diligently constructing and cultivating high-quality teaching resources in recent years. Success has been achieved in six aspects: online teaching, practical case studies, industry-education integration, science-education integration, teaching competitions, and educational reform projects, with several attaining national or provincial recognition. Table 1 shows that all these achievements have been seamlessly integrated into daily undergraduate teaching resources, facilitating the transformation and upgrading of the resource supply side. The sharing of these high-quality resources lays a foundation for achieving the goal of cultivating high-quality, innovative talent.

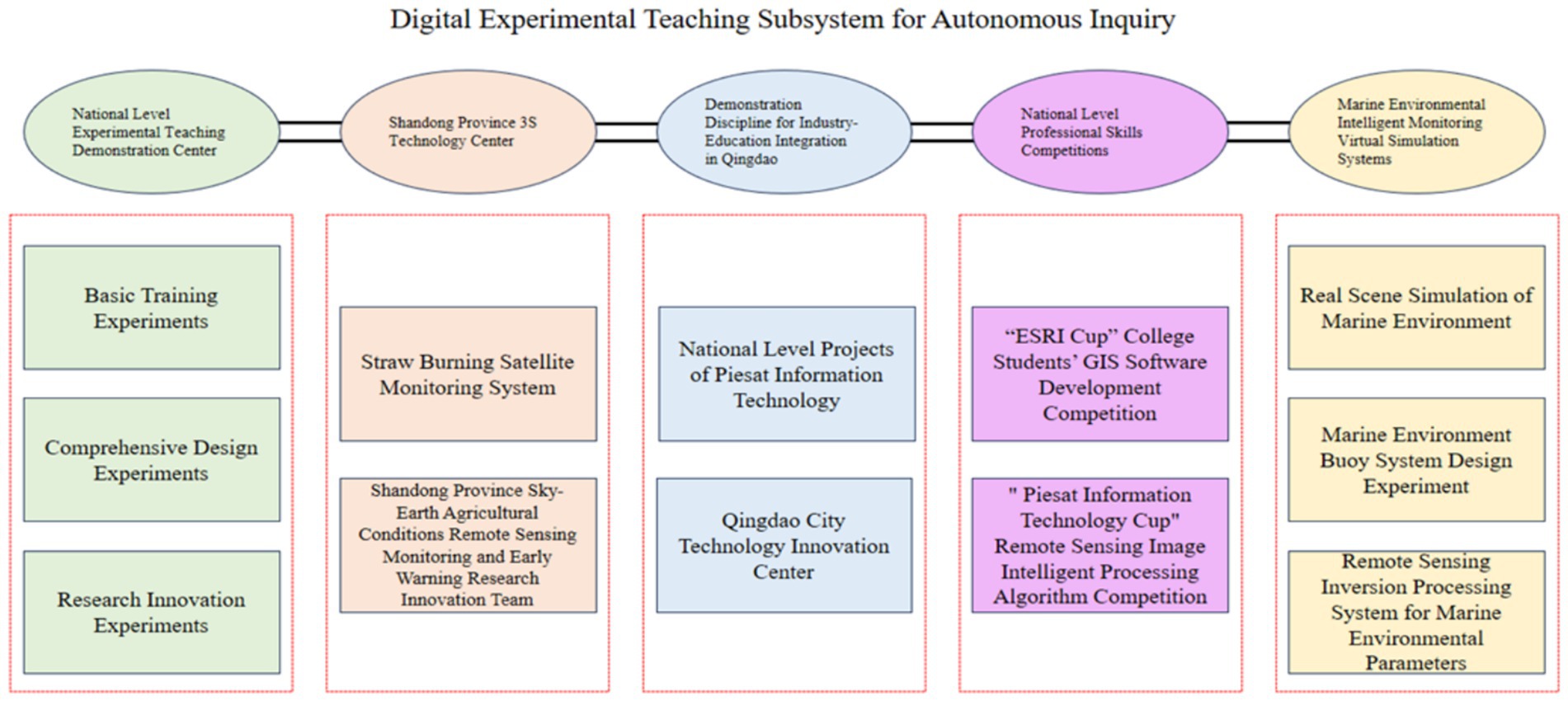

2.2.2 A digital experimental teaching system oriented towards independent inquiry

This section details the construction of an AI-enhanced, inquiry-based digital experimental teaching system. This system expands the scope of experimental inquiry, significantly broadening the experimental landscape. It enhances the setup of experimental environments, presentation methods for experimental content, and the acquisition and analysis of experimental data. This development creates a much richer teaching context for students engaged in exploratory learning. This system enables students to enhance their design thinking, programming skills, and scientific modeling abilities through practical experimentation. It facilitates a comprehensive improvement in digital literacy, problem-solving skills, and communication and collaboration abilities as students engage in experimentation and practice.

The experimental teaching system (Figure 4) consists of five components:

1. Leveraging the national-level experimental teaching demonstration center, the system fully exploits the role of practical teaching platforms in talent development. Students are provided with drones, allowing them to autonomously control flights to collect multispectral data, engage in data processing, and undertake innovative modeling.

2. Fusion of science and education involves students participating in research projects and scientific innovation teams of teachers, relying on the “Shandong Province 3S Technology Center.”

3. Industry-education integration is achieved through collaboration with the platform of the “Demonstration Discipline for Industry-Education Integration in Qingdao Higher Education Institutions.” Focusing on the development needs of key industries in Qingdao, a collaboration with Aerospace Macro Information Technology Co., Ltd., and Qingdao Technology Innovation Center is established for student training.

4. Using competitions as a catalyst for learning, students integrate into the teacher’s scientific innovation team by participating in national, provincial, and association-level remote sensing competitions and applying for projects in the national-level university student innovation and entrepreneurship training program. Competition content is incorporated into classroom teaching.

5. Finally, the system constructs virtual simulation software and cloud platforms to provide students with visually appealing (Mikropoulos and Natsis, 2010), experientially engaging, and functionally efficient virtual simulation experimental conditions. This upgrade aims to achieve the evolution of teaching resources.

2.2.3 Data sources and participant characteristics

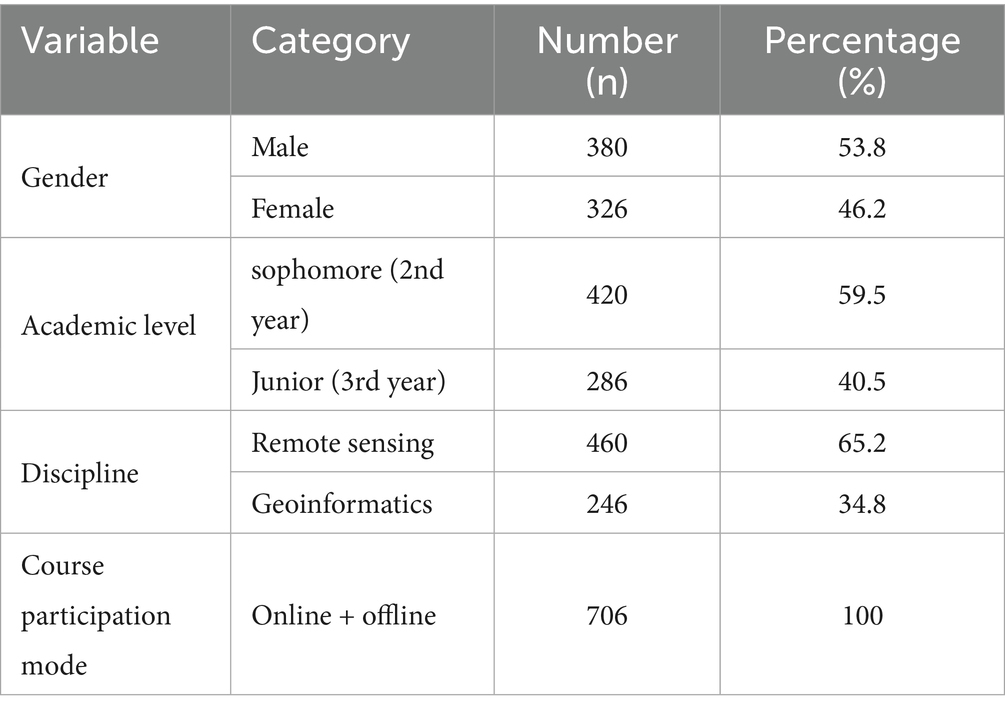

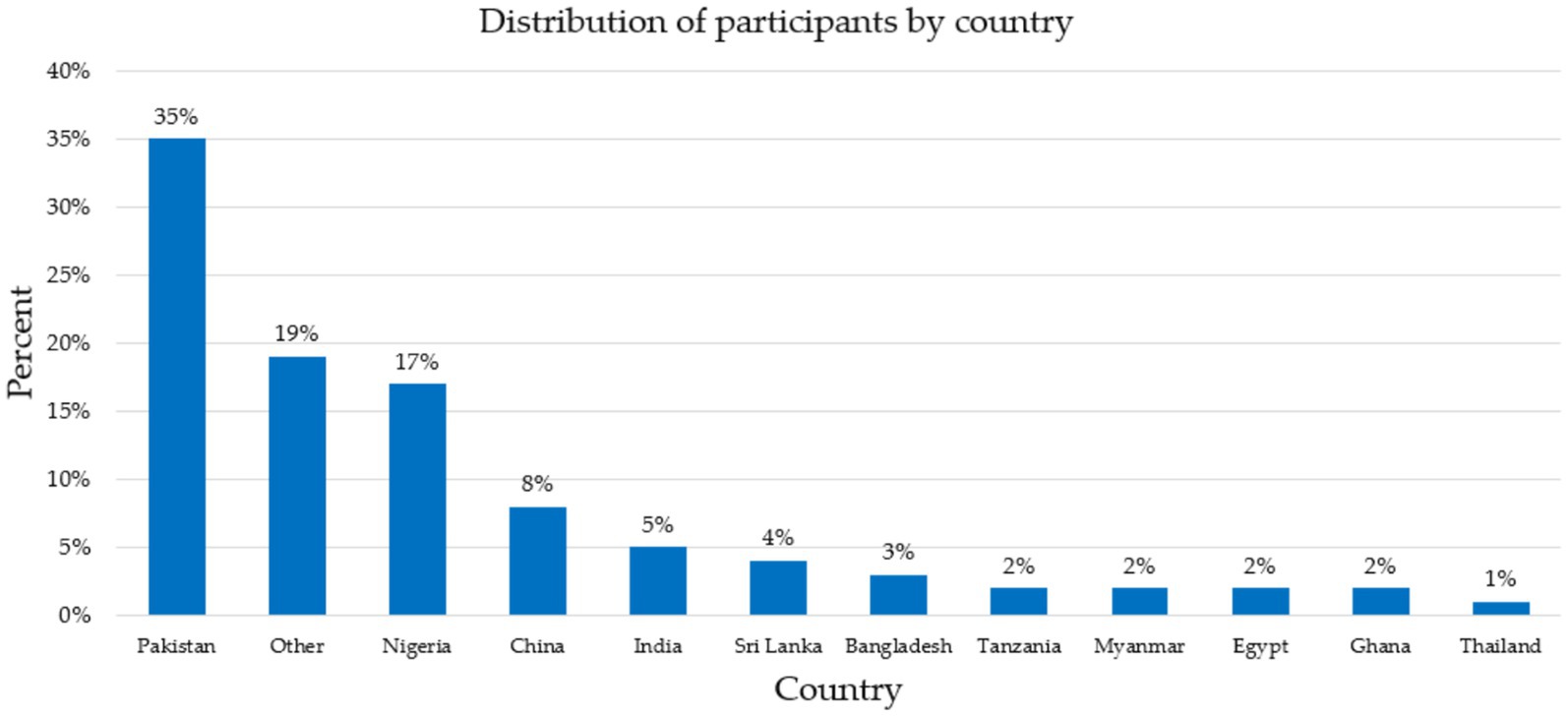

This study was conducted among undergraduate students majoring in Remote Sensing and Geoinformatics at Shandong University of Science and Technology in China. In total, 706 students participated in the ‘Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing’ course between 2020 and 2023. The course was delivered through hybrid learning modes via Zhihuishu and Chaoxing online platforms, integrating online and offline instruction.

Data collection included the following components:

1. Learning behavior logs automatically generated by the online platforms (e.g., video viewing time, quiz completion, and discussion participation);

2. Pre-test and post-test results used to evaluate learning effectiveness;

3. Online survey responses assessing students’ perceptions of course design and AI-supported learning experiences.

Before analysis, data were anonymized and preprocessed. Missing values were handled by listwise deletion when necessary, and continuous variables were standardized to ensure comparability. The demographic composition of the participants is summarized in Table 2.

This study adopted a quasi-experimental quantitative design, where only one experimental group received the AI-supported instructional intervention (Creswell, 2014; Campbell and Stanley, 2015). Due to the course organization structure, a synchronous physical control group was not feasible; therefore, students’ historical performance in previous semesters was used as a reference.

The online survey utilized to assess students’ perceptions was developed based on a comprehensive literature review. To ensure content validity, the initial survey was reviewed by a panel of three experts in educational technology and remote sensing pedagogy. Their feedback was incorporated to refine the item wording and relevance. A pilot study was conducted with a sample of 50 students (not included in the main study) to assess the reliability of the survey scales. The internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s Alpha, was found to be above 0.8 for all key constructs (e.g., perceived engagement, satisfaction with AI tools), indicating good reliability (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011).

3 Intelligent teaching design

According to survey data from 2019, approximately 20–25% of schools in the United States have initiated the process of digital transformation, and China’s development progress and extent are roughly comparable. Globally, prevalent scenarios for AI applications in higher education include plagiarism detection (Devedzic, 2004), automated assignment grading (Timms, 2016), chatbots, online proctoring (Snyder, 2019), adaptive tutorials (Hinojo-Lucena et al., 2019), accessible communication (Chassignol et al., 2018), learning risk prediction, online teaching (Kahraman et al., 2010), and efficiency tools (Peredo et al., 2011), among others.

From a teaching perspective, guided by constructivist learning theory, this article explores the deep integration of artificial intelligence technology and educational instruction. The instructional implementation adopts a blended learning structure combining online learning (Zhixueshu MOOC, forum interaction, AI-enabled learning analytics) and offline classroom activities (experimentation, case discussion, collaborative inquiry).

The integration mechanism includes:

• Online before class: Engagement and pre-assessment.

• Offline during class: Exploration, explanation, and elaboration.

• Online + offline after class: Evaluation and feedback via AI analytics.

3.1 5E deep learning teaching model

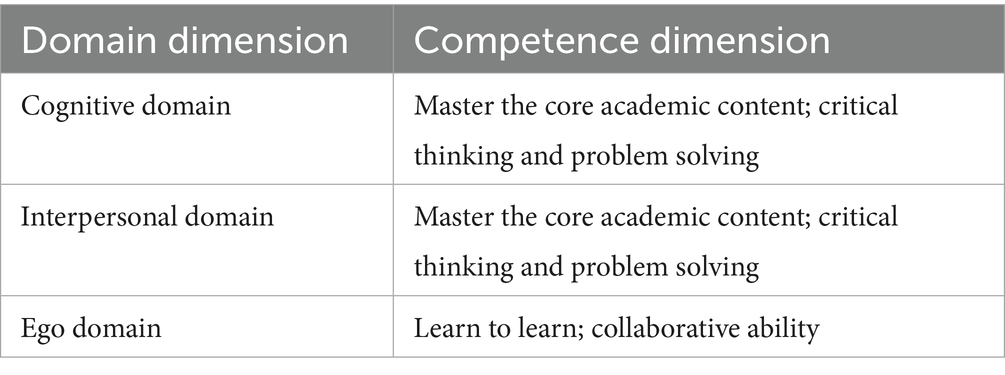

The concept of deep learning in education was initially proposed by Marton and Säljö from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden (Shen, 2015). In 1976, while researching university students engaged in extensive prose reading tasks, they observed differing levels of information processing among students, displaying disparities between surface and deep approaches to learning. Based on this, the two scholars introduced the concept of “deep learning,” defining it as a knowledge transfer process that helps learners enhance their problem-solving and decision-making abilities. The American Institutes for Research further delineated deep learning into three major domains—cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal—forming a compatible framework of deep learning across domains and competency dimensions (Table 3).

Table 3. Deep learning compatibility framework in the domain dimension and the capability dimension.

From this framework, we can observe that deep learning is proposed in response to prevalent issues in teaching practices, such as mechanical learning, rote memorization, and shallow learning characterized by knowing the facts without understanding the underlying principles, or pseudo-learning. The 5E deep learning model, introduced by scholars including Bybee et al. (2006) represents a constructivist teaching approach. It has gained widespread application in science classrooms due to its broad applicability. The 5E deep learning model stands for Engagement, Exploration, Explanation, Elaboration, and Evaluation. It has garnered significant attention in education (D'Mello et al., 2010; Ignatov et al., 2018; Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, State Council, China, 2020).

3.2 Smart classroom teaching based on 5E deep learning teaching model

We chose the widely used Chinese online course platform ‘Zhihuishu’ to deliver our MOOC, titled “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing.” Aligning with the development positioning and talent demands of China’s surveying and geospatial information industry, we have optimized the teaching content and curriculum structure, blending “theoretical core, professional frontier, and innovative practice.” We have restructured the course into four theoretical core modules, four innovative practice modules, and 26 cutting-edge industry points.

Simultaneously, the MOOC provides diversified teaching materials, catering to the learning needs of students with different levels and interests. We strive to offer personalized and differentiated teaching services to students. For each teaching project within “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing,” we provide an online course catalog that includes “teaching objectives (key points and difficulties),” “courseware (PPT),” “teaching videos corresponding to the PPT,” “extended learning materials,” “online tests and assignments,” “discussion forums,” and “practical cases.” The resources comprise 49 course videos totaling 636 min, a question bank with 365 questions, and 16 discussion topics. Reference materials comprise 37 items, including literature, reports, experimental procedures, and practical case studies.

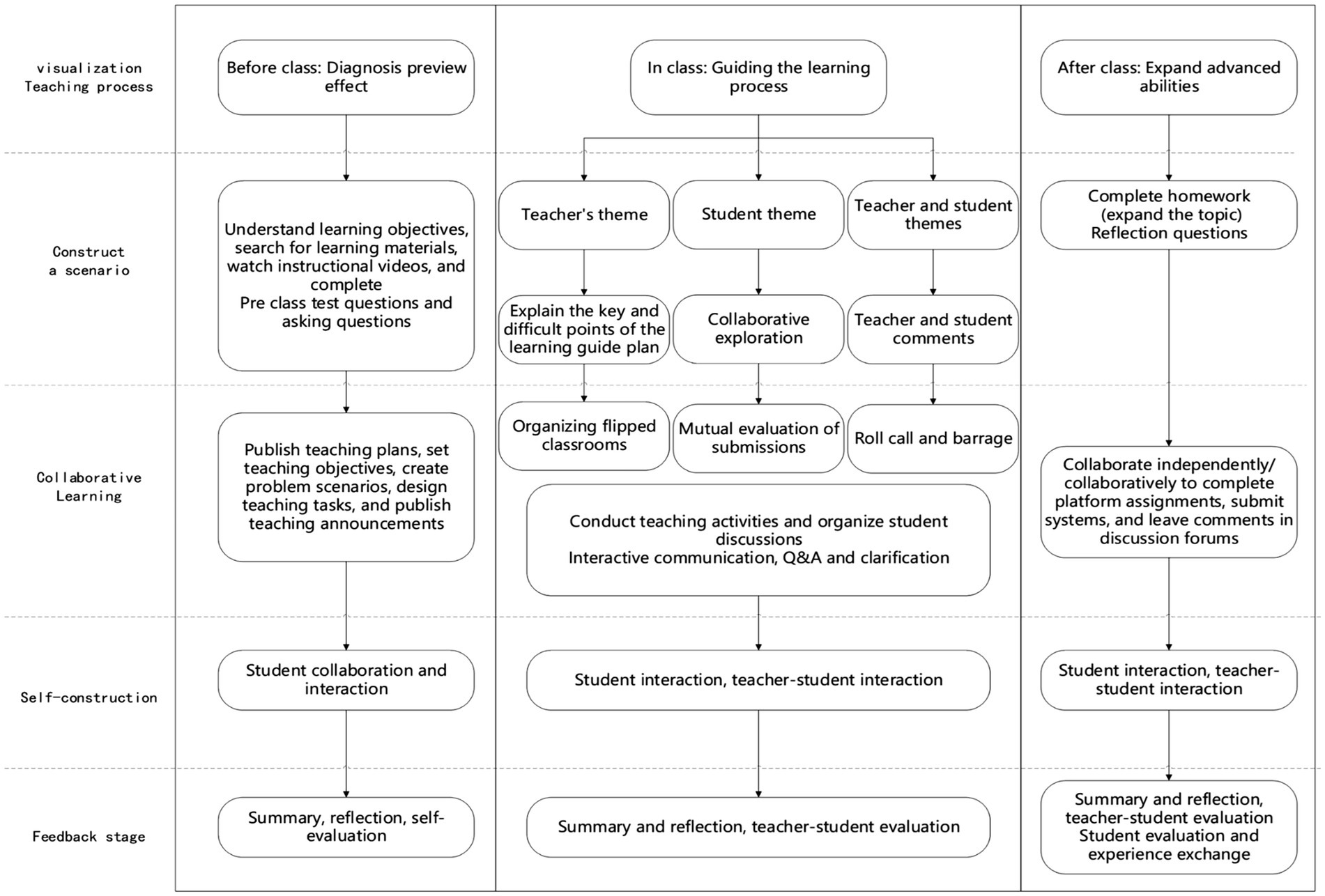

The course is based on platforms like “XuetangX,” “Zhizhidao” intelligent teaching app, and real-time messaging software such as “WeChat” and “QQ.” Leveraging cloud platform functionalities for data push, collection, and analysis, it enables the analysis of student learning. A student-centered approach integrates various teaching activities, including lesson preparation, task assignments, classes, quizzes, group discussions, and peer assessments. It employs multimodal teaching methods like online learning, flipped classrooms, BOPPPS classrooms, case discussions, and practical examples. This course implements a diverse, tiered, and differentiated hybrid teaching innovation model (Figure 5) by blending online and offline elements, theoretical and practical aspects, and mixing in-class and out-of-class activities.

The instructional design followed the 5E learning model (Engagement, Exploration, Explanation, Elaboration, Evaluation), which has been proven effective in inquiry-based STEM education (Bybee et al., 2006).

The specific strategies of the 5E instructional model proposed by us are as follows (Figure 6).

3.2.1 Step 1: engagement: igniting student engagement and inquiry interest

The primary task of this stage is for the teacher to create a problem scenario that stimulates interest in the learning task and encourages students to engage actively in learning and exploration. The questions within the scenario should adhere to three key connections: connecting with students’ real-life experiences, linking to the course content and teaching tasks, and relating to existing knowledge and concepts. It should captivate students, trigger cognitive conflict, and foster active engagement in knowledge construction.

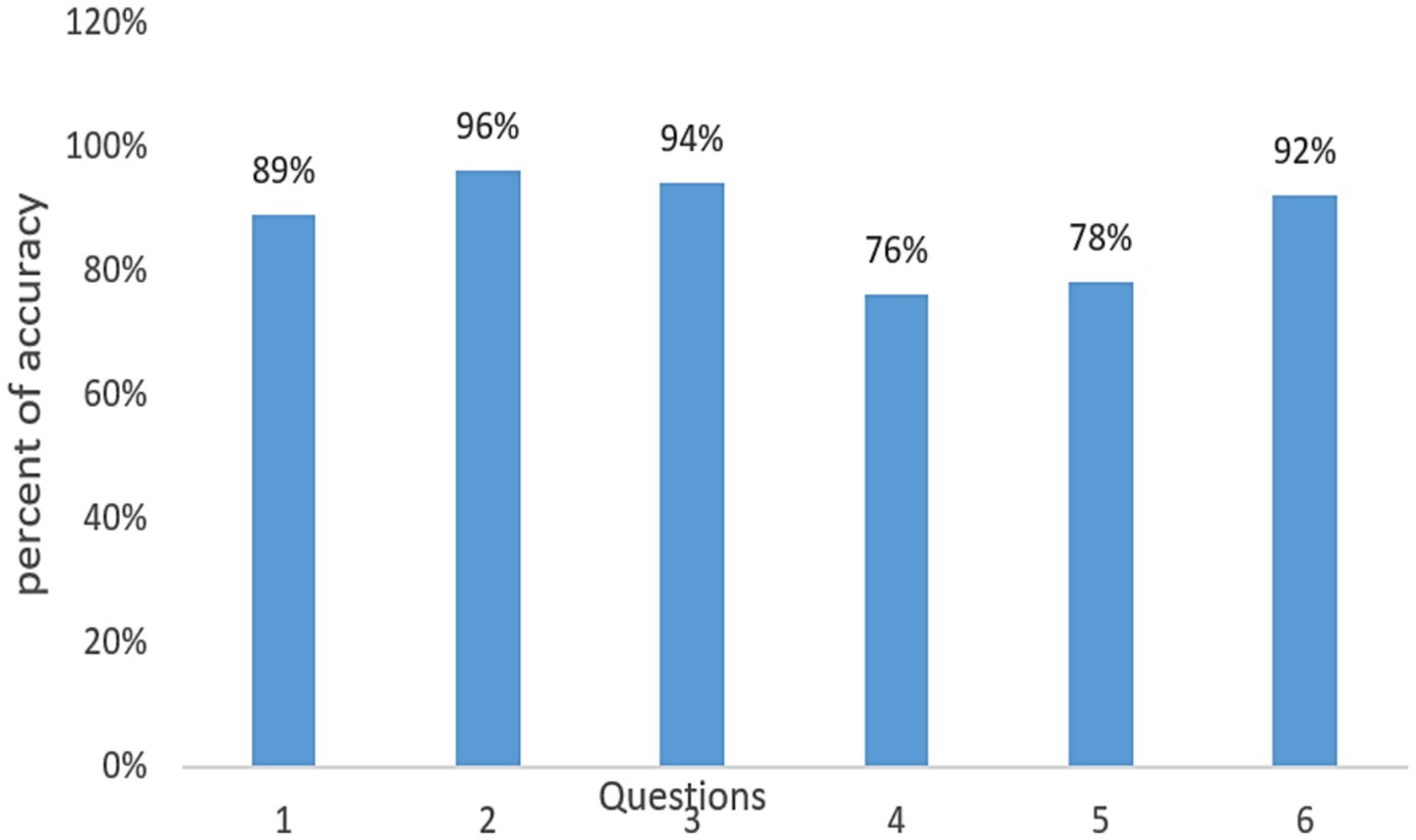

Firstly, the teacher disseminates instructional announcements through the cloud platform. They publish the teaching plan, establish objectives, create discussion scenarios, and design teaching tasks. Based on the tasks provided by the teacher, students engage in self-directed learning activities such as understanding learning objectives, searching for relevant study materials, watching instructional videos, completing pre-class test questions, and posing questions. Students can form study groups, collaborate, establish a visual learning micro-platform, individually complete exercises and preview readings, or engage in discussions and sharing based on posed questions. During the preview phase, interactive methods primarily utilize the platform’s designed message boards and discussion forums. The teacher collects real-time feedback on students’ learning outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 7 (pre-class test results), to understand individual differences in students’ pre-class knowledge comprehension. This information enables targeted adjustments to classroom teaching objectives, informs the reshaping of teaching methods, and facilitates the organization of teaching formats.

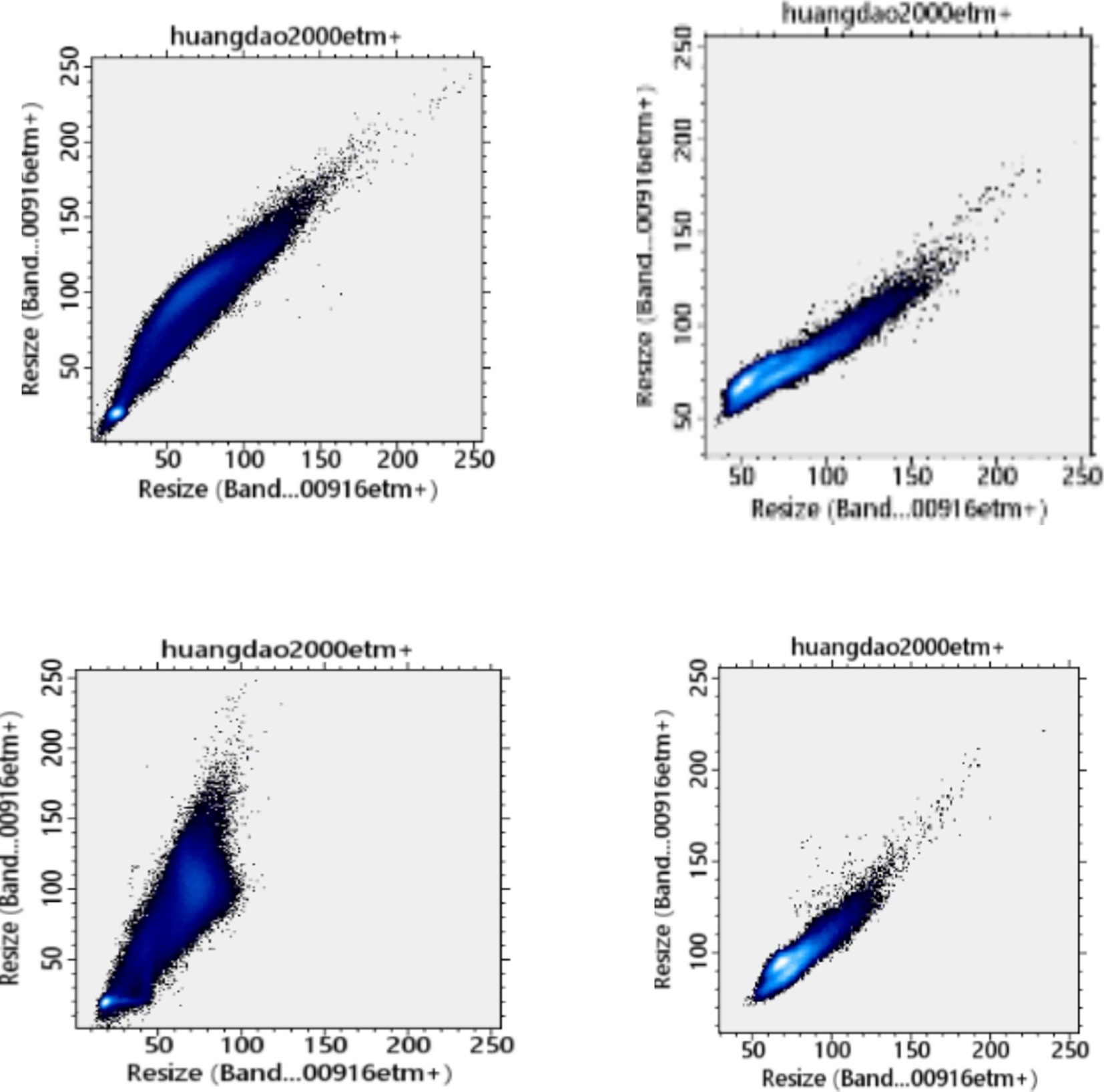

We analyze and evaluate pre-class learning (online) and test data, allowing teachers to address specific difficulties and adjust classroom organizational forms. Taking the “Remote Sensing Image Feature Transformation” unit as an example, students are grouped into teams of four. The teacher organizes the students to work in small groups to complete the experiment of drawing multi-band spectral feature maps (Figure 8) and initiates group discussions. Based on the experiment, students’ thinking becomes active, filled with curiosity and questions.

1. What is the multispectral feature space and its purpose?

2. Analyze the relationship between data volume and information content among various spectral bands in the context of the multispectral feature space. Is it correlated or uncorrelated?

A series of inquiry-based questions guides students in cultivating divergent thinking, but the teacher does not directly provide them with the answers.

3.2.2 Step 2: exploration: in-depth and continuous inquiry

This stage is the central component of the “5E” instructional model, with the primary aim of enabling students to engage in authentic and effective inquiry, learn key concepts, acquire new skills, and gain experiences in research, exploration, and questioning. It also involves comprehending the underlying relationships among concepts through feedback and examination, thereby fostering further learning and skill development. Experimental research, scenario studies, and hands-on activities are common instructional tasks during this phase. In the inquiry process, students take on the role of the subject, while the teacher acts as a facilitator and observer of student learning. Teachers should design and encourage collaborative learning, provide time for students to think and receive feedback, facilitate genuine and high-quality learning, and listen to students’ voices. Analyzing student behavior, offering timely and targeted feedback, tracking progress, and adjusting are crucial to ensuring that students can effectively and correctly engage in inquiry. Only by continually cross-verifying their own experiences with those of others can students enrich their perspectives, extend their judgments, and gradually clarify their thinking.

Guided by the questions in step 2, students conduct research using the Internet, AI, platform course resource libraries, and textbooks to acquire fundamental knowledge. They collaborate to design and conduct experiments that validate their hypotheses. Given that different students have different aspects of inquiry questions, their experiments also vary. The experimental topics are listed below:

(1) The relationship between points in the multispectral feature space and points on remote sensing images.

(2) The impact of redundancy in multispectral remote sensing data on extracting remote sensing information.

(3) What is the relationship between information attributes among different spectral bands?

3.2.3 Step 3: explanation: verify the genuine understanding of the learned material

This stage primarily aims to further assist students in understanding key knowledge and concepts in new learning scenarios. It involves reinforcing the connections and understanding between new and prior knowledge and concepts, ultimately transforming the acquired knowledge into internalized experiences and cognition for individual students. This process is essential for making new concepts, processes, or methods explicit and understandable. This stage is typically manifested in collaborative discussions and presentations within small groups.

Teachers should provide ample opportunities for students to describe and explain what they observe and articulate the reasons behind those observations. Before this, through various guidance methods, teachers explain to students how to interpret observed phenomena scientifically.

Teachers should guide students in connecting their scientific explanations with the evidence obtained from the participatory exploration activities. Additionally, they should link these explanations to the interpretations students have already developed, forming a robust chain of evidence and logical relationships. Teachers should further encourage students to articulate the exploration process and results using scientific terminology, fostering a profound understanding of scientific concepts.

At this stage, the teacher guides student groups to project their answers on the big screen, introducing new lessons and addressing key challenges. If the students collected data and analyzed experimental results during the exploration stage, they are expected to explain them using scientific knowledge. In this phase, students learn and deepen their understanding of concepts and principles, such as the necessity of feature transformation and various methods.

During this stage, students find answers to the explored questions and stimulate more and deeper concepts. Building on this foundation, the teacher raises the bar, challenging each group to apply the acquired knowledge to practical situations and design a typical application scenario for feature transformation. The students’ enthusiasm and initiative are instantly sparked, and they engage in spontaneous brainstorming as follows:

(1) What is the necessity of feature transformation in remote sensing image analysis?

(2) Methods and steps of feature transformation in remote sensing image analysis.

(3) What are the Principal Component Analysis’s (PCA) characteristics?

(4) Is feature transformation necessary in the computer interpretation of remote-sensing images?

Students utilized their imagination, creativity, communication, and collaboration abilities during this exploratory stage. Based on the available time and materials, the teacher guided students in conducting research and analyzing feasibility, and each group ultimately selected a research scenario to pursue.

3.2.4 Step 4: elaboration: applying learning to Foster knowledge and conceptual transformation

This phase encourages students to apply newly acquired knowledge in novel or similar contexts. Teachers should create and provide new scenarios for applying knowledge and concepts, guiding students to apply their understanding and skills to solve new problems, acquire and apply new concepts and skills, and establish connections with other knowledge and skills to build a comprehensive knowledge network.

For instance, when exploring dynamic changes in land use in a specific region, is there a need to preprocess feature changes, and what particular methods are used? Can Principal Component Analysis be employed in image fusion? Students should fully utilize previously learned knowledge and concepts to apply, explain, and solve problems in new, analogous situations. They should be able to propose solutions, make decisions, design experiments, draw reasonable conclusions from evidence, and solve problems, thereby practicing, validating, applying, and consolidating their understanding, refinement, internalization, and application of new concepts.

3.2.5 Step 5: evaluation: diverse assessment for authentic feedback on student learning

This is the concluding phase of the “5E” classroom approach. It primarily employs various assessment methods, such as teacher evaluations, student self-assessments, and peer evaluations within groups. During this phase, teachers observe how students apply new concepts and methods to solve problems and pose open-ended questions to assess students’ understanding and application of these new concepts and methods. Teachers also collect evidence of students’ changed thinking and behaviors through questioning, group discussions, documenting hands-on skills, experimental results, presentation reports, and written assessments, among other formats, to provide a comprehensive evaluation. Teachers also encourage students to conduct self-assessments of their learning. They should design assessment criteria based on the learning content and methods to more objectively, comprehensively, and authentically reflect students’ learning situations. Therefore, the evaluation is not limited to exam or test results; it should also emphasize the inquiry process and the degree of student participation.

3.3 AI-driven learning analytics and feedback mechanism

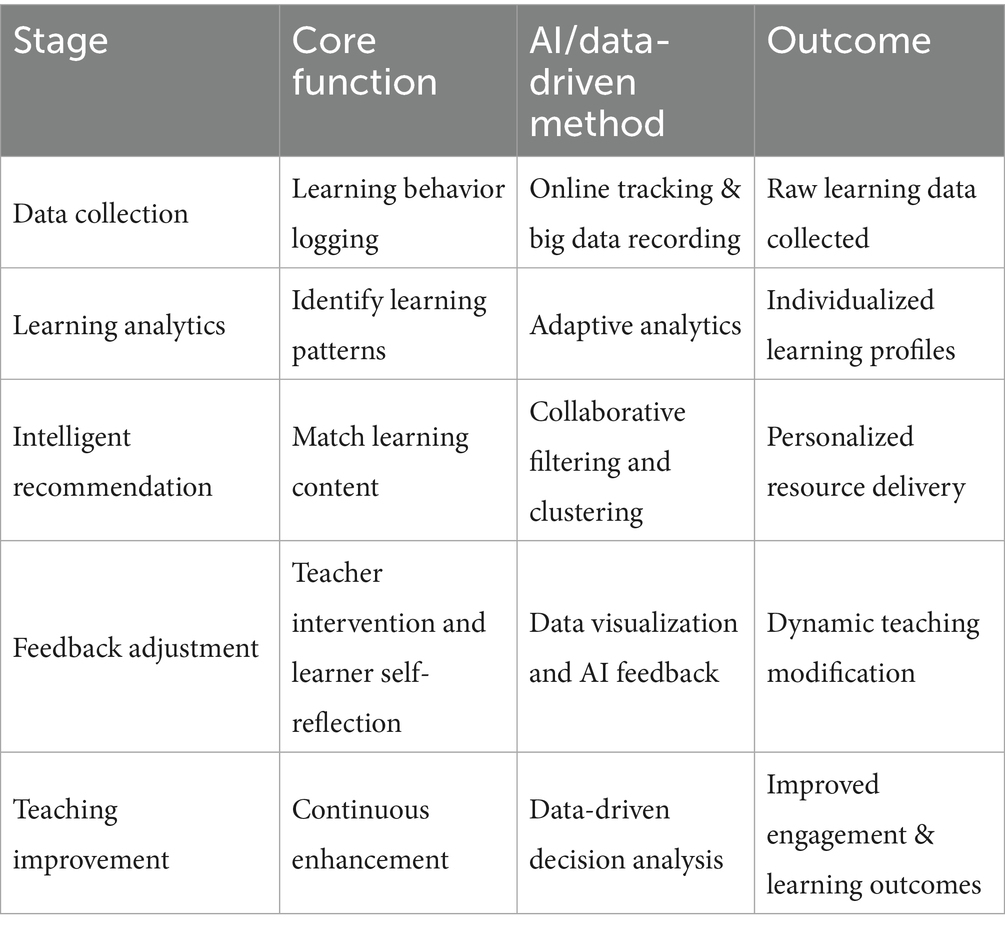

To enhance the scientific design of intelligent teaching and strengthen data-driven decision-making, this study incorporates multiple artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics techniques into the 5E deep learning model. These techniques are applied at different stages of teaching — including instructional content delivery, learning behavior analysis, and performance evaluation — forming a closed-loop mechanism for continuous teaching improvement (Table 4).

1 Adaptive Learning Analytics

The teaching platform automatically collects and analyzes learners’ behavioral data, such as video engagement time, quiz accuracy, discussion frequency, and assignment submission patterns. By employing adaptive learning analytics algorithms, the system identifies students’ learning preferences and difficulties. It then dynamically recommends personalized learning resources and adjusts instructional pacing, ensuring that both high-performing and low-performing students receive targeted guidance.

2 Intelligent Recommendation System

The system integrates a resource recommendation algorithm that combines collaborative filtering and clustering methods. It matches learning content to students based on their previous activities, performance trends, and interests. For example, students who demonstrate weaker understanding of “Remote Sensing Image Feature Transformation” will automatically receive supplemental materials such as case videos and self-assessment quizzes.

3 Data-driven Feedback Loop

To ensure effective interaction between teachers and students, an AI-based feedback loop has been established. The platform analyzes real-time learning data, visualizes key indicators (e.g., participation rate, accuracy improvement, engagement level), and provides feedback to teachers for instructional adjustment. At the same time, students can access individualized learning reports generated by the system to reflect on their progress and optimize study strategies. This process constitutes a closed-loop feedback mechanism that continuously refines teaching quality and learning outcomes.

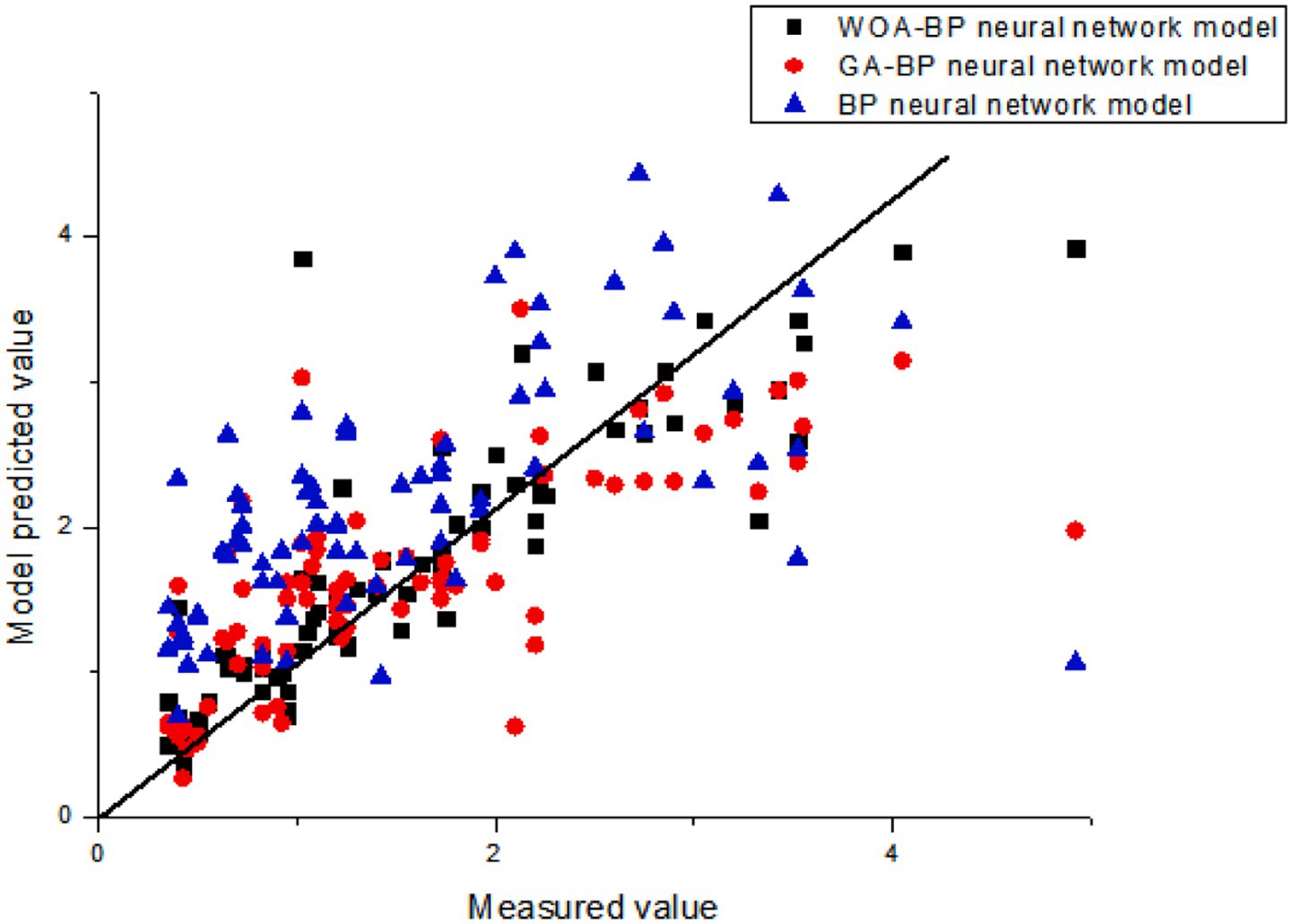

4 Application of Neural Network Optimization Algorithms

In the Digital Experimental Teaching System, students apply AI algorithms such as BP Neural Network, GA-BP (Genetic Algorithm optimized BP), and WOA-BP (Whale Optimization Algorithm improved BP) for data modeling and prediction tasks. These algorithms were used in case studies like “Chlorophyll-a Concentration Inversion” and “Sea Ice Detection System,” enabling students to experience the integration of AI with remote sensing applications and to enhance computational thinking and problem-solving abilities.

5 Visualization of AI-driven Feedback

Table 4 illustrates the overall structure of the AI-supported teaching feedback loop, showing the relationships among the five key modules: data collection → learning analysis → intelligent recommendation → feedback adjustment → teaching improvement.

In Engagement and Exploration, student curiosity and inquiry intention are stimulated (Duran and Duran, 2004). In Explanation and Elaboration, learners collaboratively construct knowledge through reflection and classroom dialogue (Kim, 2001). Evaluation emphasizes competency-oriented authentic assessment to promote deep learning (Minner et al., 2010).

These five steps together provide a coherent pedagogical scaffold aligned with constructivist learning theory.

4 Results

Teaching evaluation is a crucial component of educational activities, pivotal in enhancing the quality of talent cultivation and driving educational reform. In recent years, the profound integration of big data technology, artificial intelligence, and education has enabled the recording and statistical analysis of students’ learning processes and various learning data (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, State Council, China, 2020; Duan, 2021). This integration enables highly targeted assessments aligned with each student’s learning progress and academic growth.

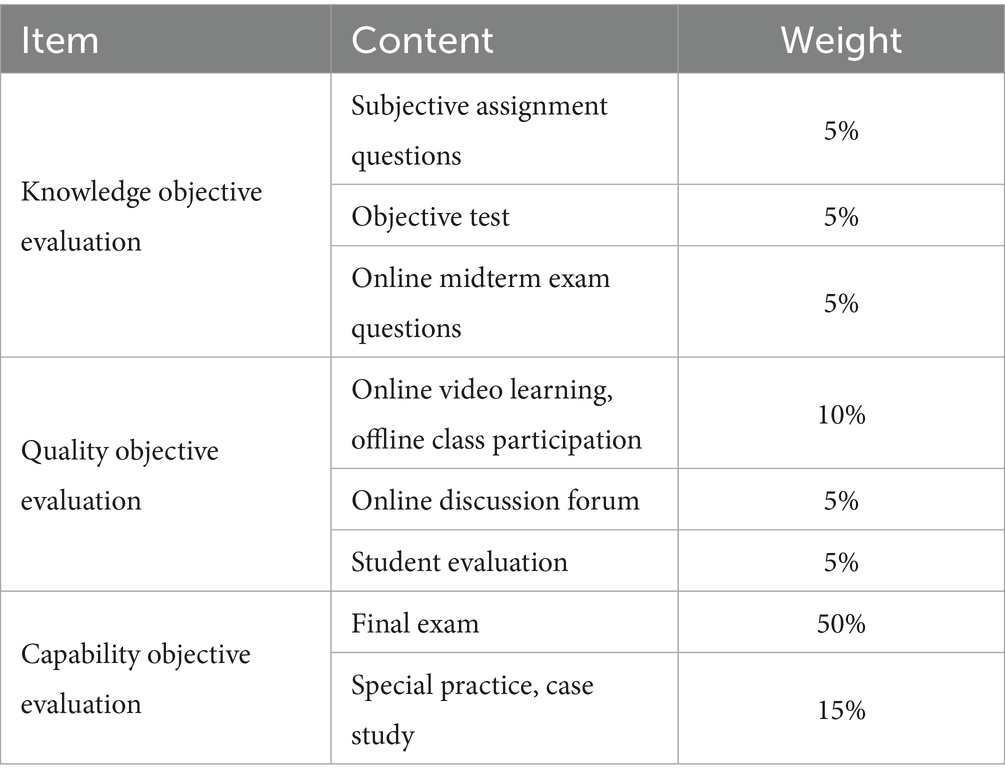

The evaluation results are primarily utilized to improve teaching and guide students’ development. Therefore, the evaluative process should possess diverse and developmental characteristics, considering both the process and outcomes. As shown in Table 5, forms of learning effectiveness evaluation include online grades, classroom participation, group discussions, special practices, and regular performance, assessing knowledge objectives (15%), quality objectives (20%), and competency objectives (60%). Leveraging artificial intelligence teaching tools, teachers analyze learning process data to generate individualized student learning reports, conduct retrospective analyses, and provide timely feedback.

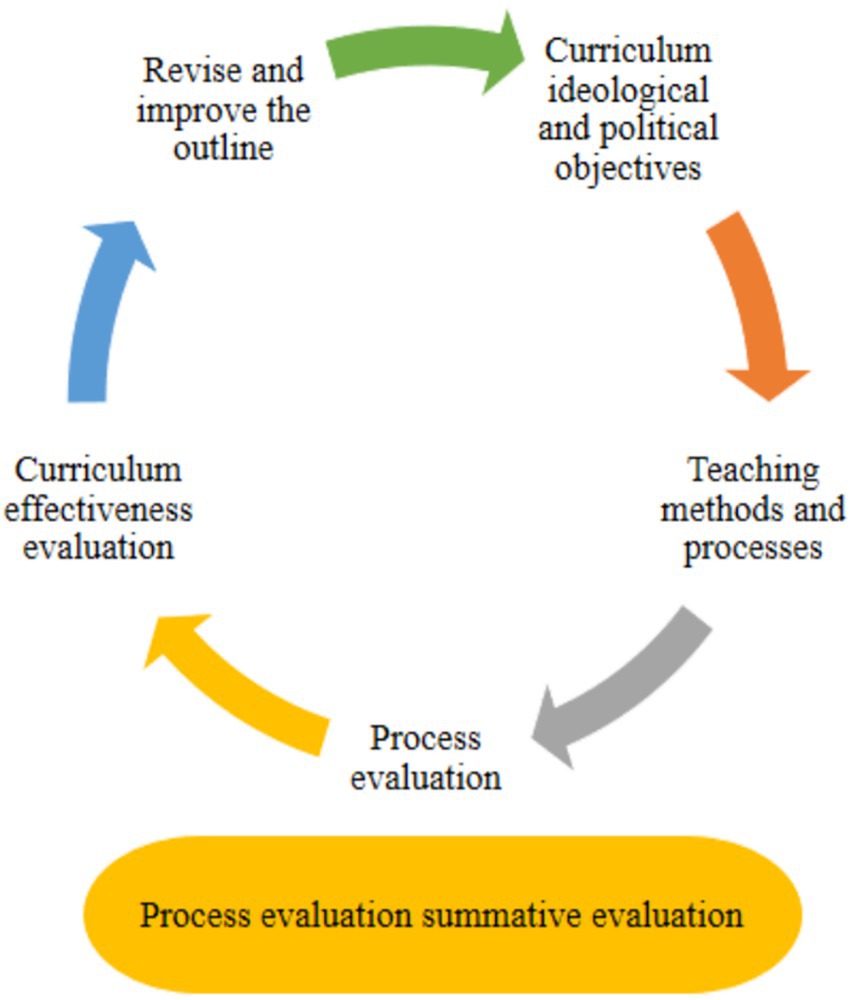

Simultaneously, teachers dynamically improve their teaching strategies by starting from the course outline, implementing the teaching process, evaluating the process, and assessing the course. This forms a closed-loop feedback system, continuously enhancing teaching practices (Figure 9).

We use grades, grade distribution rate (%), and goal achievement to evaluate teaching effectiveness. The calculation of the achievement degree is shown in Equations 1 and 2:

: Average score of the corresponding examination of each goal.

: Full score of the corresponding examination of each goal.

: The achievement degree of the corresponding assessment links of each goal.

: The proportion of each target section.

A: The objective achievement degree.

Throughout the implementation of the entire course, the teaching team has established the MOOC course for the first-class undergraduate course “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing” in Shandong Province.1 This course has been simultaneously offered at our university for eight sessions, with a current enrollment of 706 students. In our university’s “Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing” course, the MOOC is primarily used for blended teaching, incorporating pre-class online previews, homework quizzes, and student discussions, which account for 30% of the final evaluation grade. This learning and assessment method effectively enhances students’ autonomy and learning outcomes.

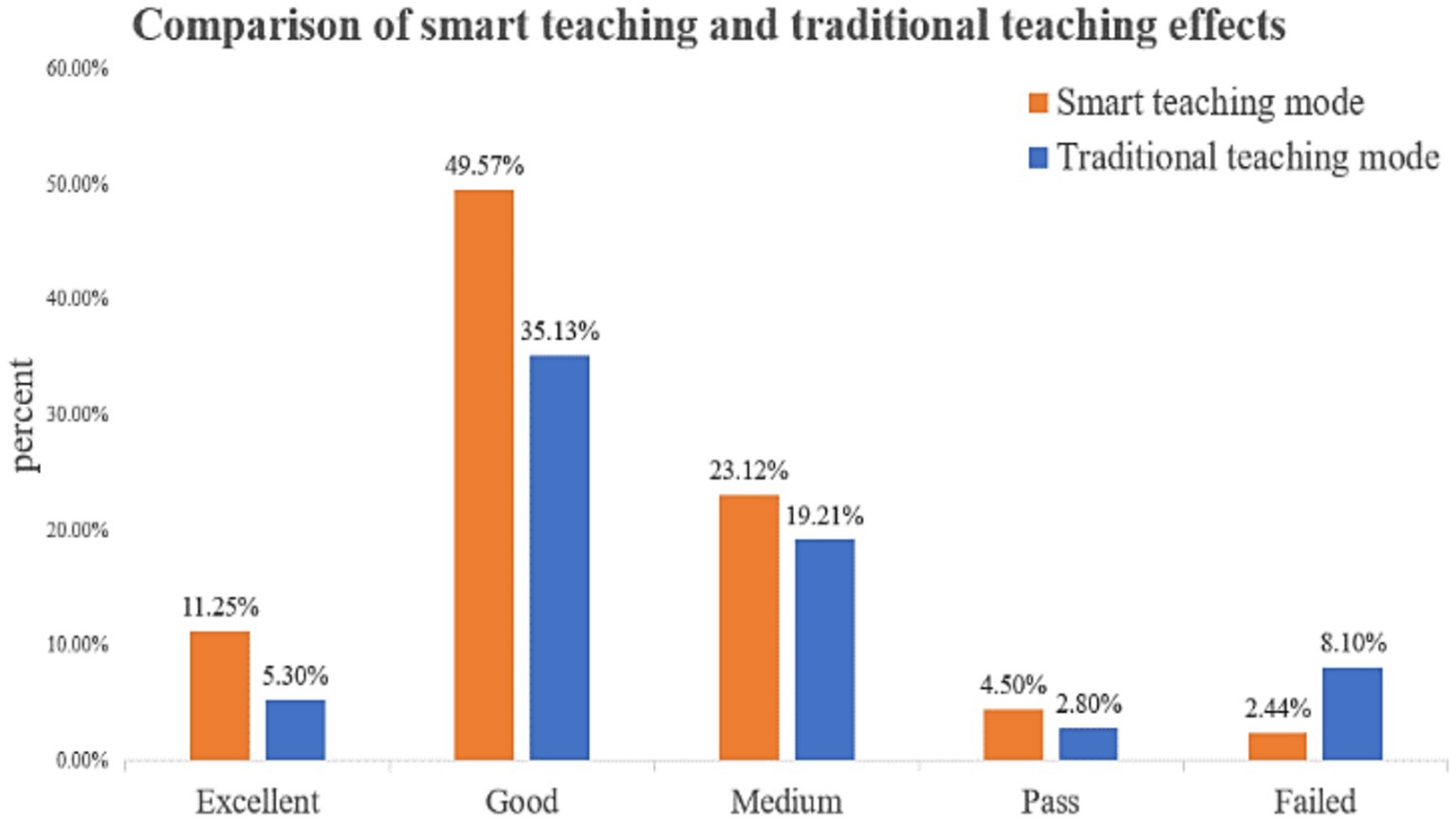

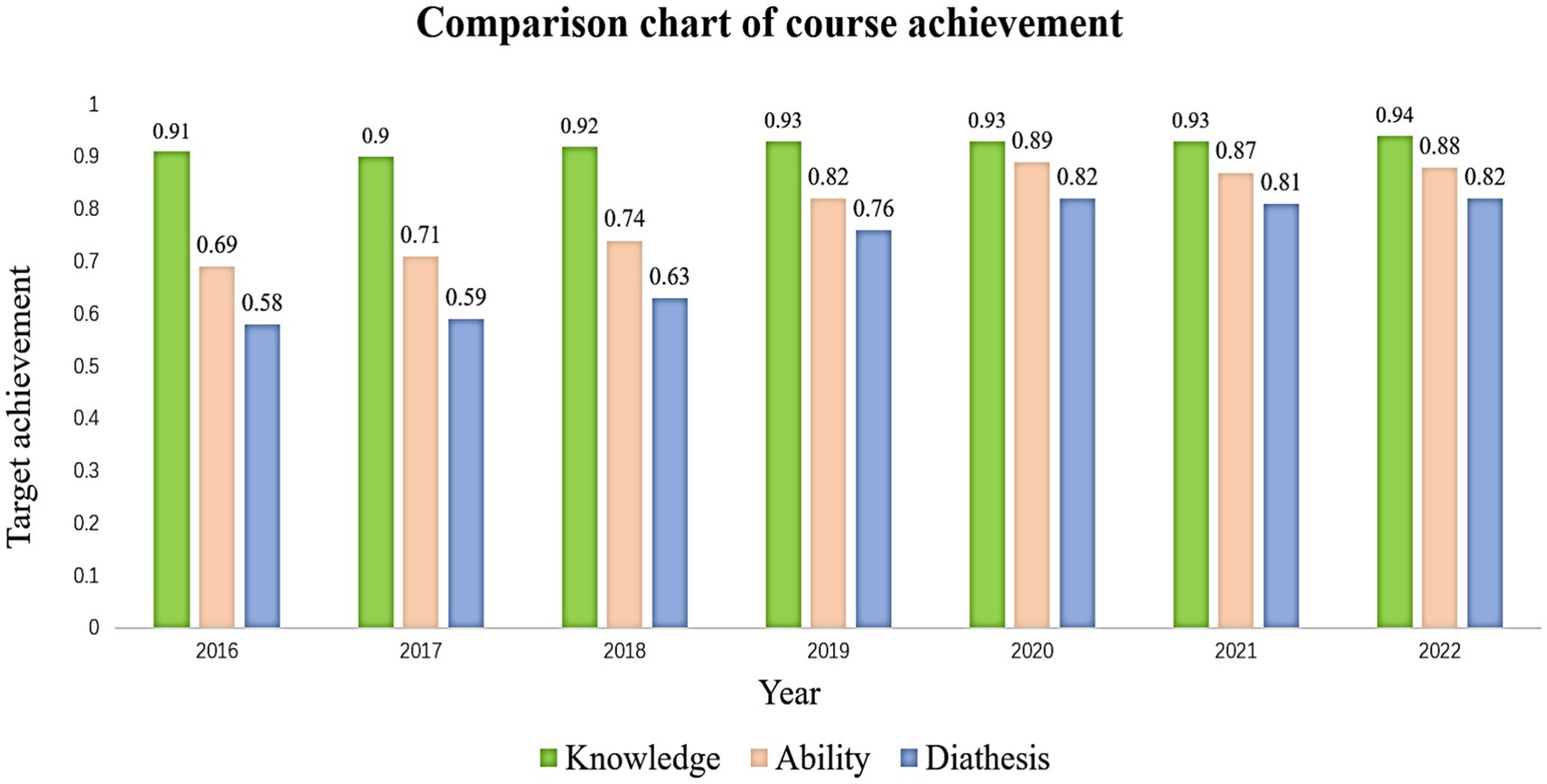

Compared to semesters without the implementation of smart teaching methods, semesters with smart teaching methods show significant improvements in average scores, pass rates, and grade distribution. Figure 10 indicates that the excellence rate has increased from 5.1 to 11.25%, the good rate has risen from 35.13 to 49.37%, and the failure rate has decreased from 8.1 to 1.44%. The student’s achievement levels in knowledge objectives, skill objectives, and quality objectives are 0.8876, 0.838, and 0.9116, respectively, demonstrating a noticeable improvement in teaching effectiveness. Figure 11 shows an increase in students’ achievement in knowledge objectives from 0.91 to 0.935, skill objectives from 0.69 to 0.88, and quality objectives from 0.58 to 0.82.

Algorithms should be numbered and include a short title. They are set off from the text with rules above and below the title and after the last line.

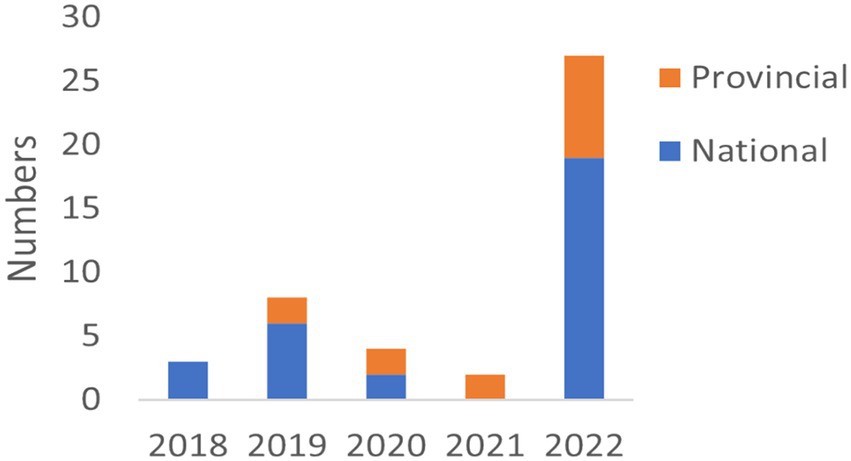

In terms of students’ technological innovation capabilities, through smart classroom teaching, the Smart Ocean Mentor Innovation Studio, and participation in competitions, students’ practical skills, independent thinking, and innovation capabilities have been significantly enhanced. Using national, provincial, and association-level remote sensing competitions and national university innovation and entrepreneurship training program projects as carriers, competition content is integrated into classroom teaching. This approach involves students in teachers’ research teams and mentor studios, establishing a practical training and practice system for independent exploration. It provides a solid platform for students to participate in subject competitions. Simultaneously, various measures, including subject skill competitions and competition rewards, have significantly motivated students to participate actively in subject competitions. During the competition, team members also learn how to collaborate and communicate, playing a unique and irreplaceable role in optimizing talent development processes.

In addition to descriptive analysis, an independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the final examination scores before and after implementing the AI-supported instructional model. Results showed a statistically significant increase in students’ performance (M_traditional = 78.35, SD = 6.28; M_smart = 83.61, SD = 5.74), t(704) = 9.42, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.63 (medium effect size). This confirms that the observed improvement in learning performance was not due to random variation.

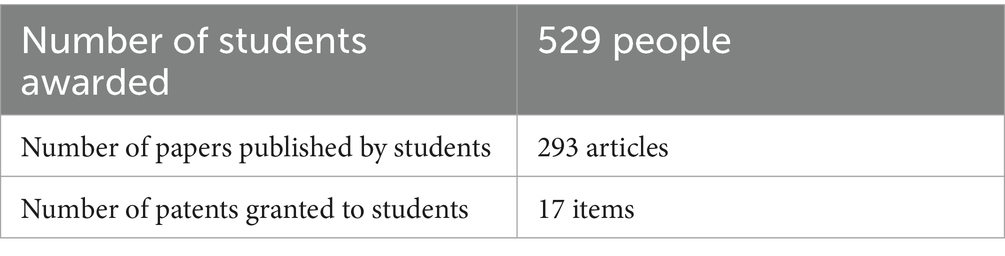

In the past 5 years (2018–2022), the number of students funded in national and provincial-level innovation and entrepreneurship training program projects is illustrated in Figure 12. There have been 39 instances of provincial-level and above innovation and entrepreneurship projects, achieving a historic breakthrough in 2022 with a total of 22 approved projects, including 19 at the national level. As shown in Table 6, students have published 293 academic papers, obtained 17 authorized invention patents, and won awards 529 times. This reflects the effectiveness of our teaching strategies in enhancing students’ learning motivation, self-directed learning abilities, innovative capacity, and practical skills.

5 Discussion

The primary research objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the AI-supported 5E intelligent teaching model in improving students’ learning performance, classroom engagement, and innovation ability in the course Principles and Methods of Remote Sensing. The following discussion focuses exclusively on interpreting these results and answering the research question.

5.1 Overall findings in relation to the research objective

Quantitative results demonstrate notable improvement after implementing the AI-supported 5E model. The mean examination score increased from 78.35 to 83.61 (+5.26 points). The proportion of excellent students rose from 5.10 to 11.25%, the “good” rate from 35.13 to 49.37%, while the failure rate decreased from 8.10 to 1.44%. Achievement levels for knowledge, skill, and quality objectives improved to 0.935, 0.88, and 0.82, respectively. These results confirm that the proposed instructional design effectively enhances academic performance and competency attainment.

5.2 Engagement and behavioral changes

Learning-behavior logs revealed higher video-completion rates, quiz participation, and forum interaction frequency, aligning with improved course grades. Pre-class diagnostics and group inquiry enabled differentiated instruction and timely formative feedback, which strengthened students’active participation and self-regulation.

5.3 Students’ research achievements

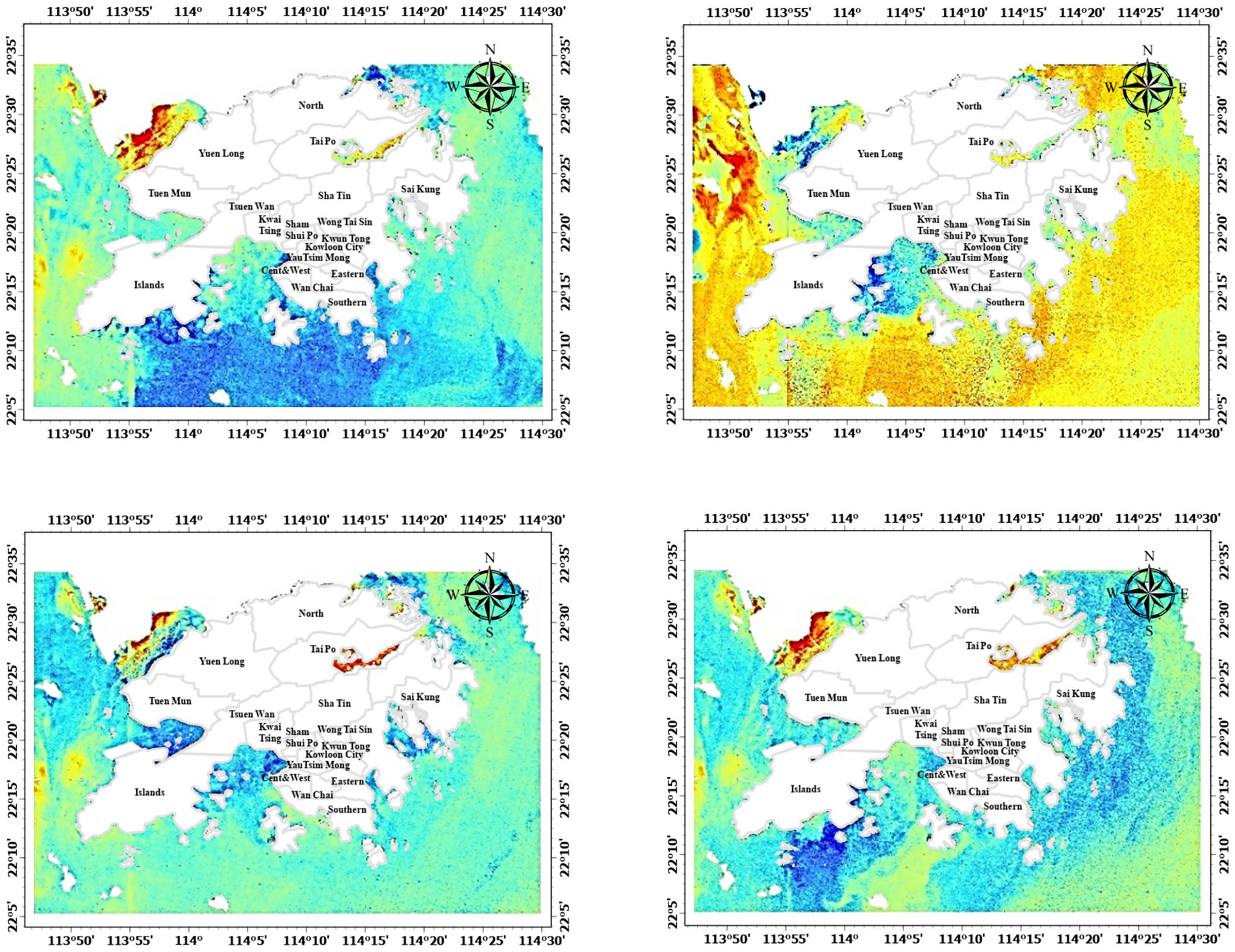

In cultivating innovation capabilities, establishing a practical case library is a crucial strategy for fostering students’ deep learning and autonomous exploration abilities. We have designed three categories of practical cases—Basic Training, Comprehensive Design, and Research Innovation—with the experiment content and training objectives progressively increasing, accounting for 30, 40, and 30%, respectively. Specific case details are presented in Table 7. For the comprehensive design practice titled “Real-time Detection System for Bohai Bay Sea Ice Based on PIE-SDK,” we require students to conduct texture analysis on Sentinel-1 SAR data (Zakhvatkina and Bychkova, 2015; Nakamura et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2019). Through machine learning algorithms, students are tasked with achieving fine-grained classification of sea ice in Bohai Bay and implementing a real-time detection system based on PIE-SDK. An undergraduate’s work based on this practical case earned a second prize in the 6th Aerospace Vision & Huawei Cloud PIE System Development Competition.

For the innovative research practice case based on the “Study of Chlorophyll-a Concentration Inversion,” a project was undertaken to develop a chlorophyll-a concentration inversion model for the coastal waters near Hong Kong. The task involved optimizing and improving the traditional BP neural network. Three models were established: a BP neural network model, a BP neural network optimized with a genetic algorithm (GA-BP), and a BP neural network model improved with a Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA-BP) (Figure 13). These models were compared and analyzed using actual measurement data (Mirjalili and Lewis, 2016; Aljarah et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2004). Figure 14 shows a reduction in error compared to the traditional BP neural network model. Students presented the outcomes of this case at the 5th International Conference on Geoscience and Remote Sensing Mapping (GRSM 2023), organized by the IEEE Earth Science and Remote Sensing Society, thereby contributing to the development of their international perspectives.

Figure 14. Seasonal distribution map of chlorophyll a concentration in Hong Kong coastal waters: spring, summer, autumn, winter.

The improvement in conceptual understanding is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the benefits of inquiry-based active learning supported by intelligent technologies (Hinostroza et al., 2024).

The results also empirically validate constructivist learning principles as the underlying theoretical foundation of the instructional design.

6 Implications and directions for future studies

This study offers practical guidance for integrating artificial intelligence and data-driven feedback into blended learning for cultivating innovative talents in emerging engineering disciplines. It offers insights for teachers, instructional designers, and educational institutions in designing adaptive and inquiry-oriented learning environments.

6.1 Application to other universities and learners in the community

Based on our university’s achievements in smart teaching, we have won the first prize in the National Surveying Teachers’ Teaching Innovation Competition and the second prize in the Shandong Province Online Excellent Teaching Case competition. Our course has been approved as a first-class undergraduate online course in Shandong Province. In the spring of 2023, the smart teaching experience of the course was continuously promoted in the Shandong University of Science and Technology’s campus newspaper, official website, official WeChat account, and Weibo.

The online MOOC (see text footnote 1) has been available for 8 semesters, offering comprehensive teaching services to over 4,000 undergraduate students from more than 30 universities. Multiple schools have consistently adopted it for SPOC teaching, including five times by Gansu Forestry Vocational and Technical College, four times by Inner Mongolia University, and three times by China University of Petroleum (East China).

During the course opening period, the discussion forum accumulated 18,400 interactions. On average, teachers post 60 times per semester, and students participate 164 times per semester. The platform randomly sent 634 survey questionnaires, with 508 valid responses. The overall satisfaction rate of the course is 92.5%. The platform indicates that the average pass rate for course exams is the highest among similar courses on the platform, with a pass rate of 68%. The highest pass rate, during the 6th round, reaches 93.5%.

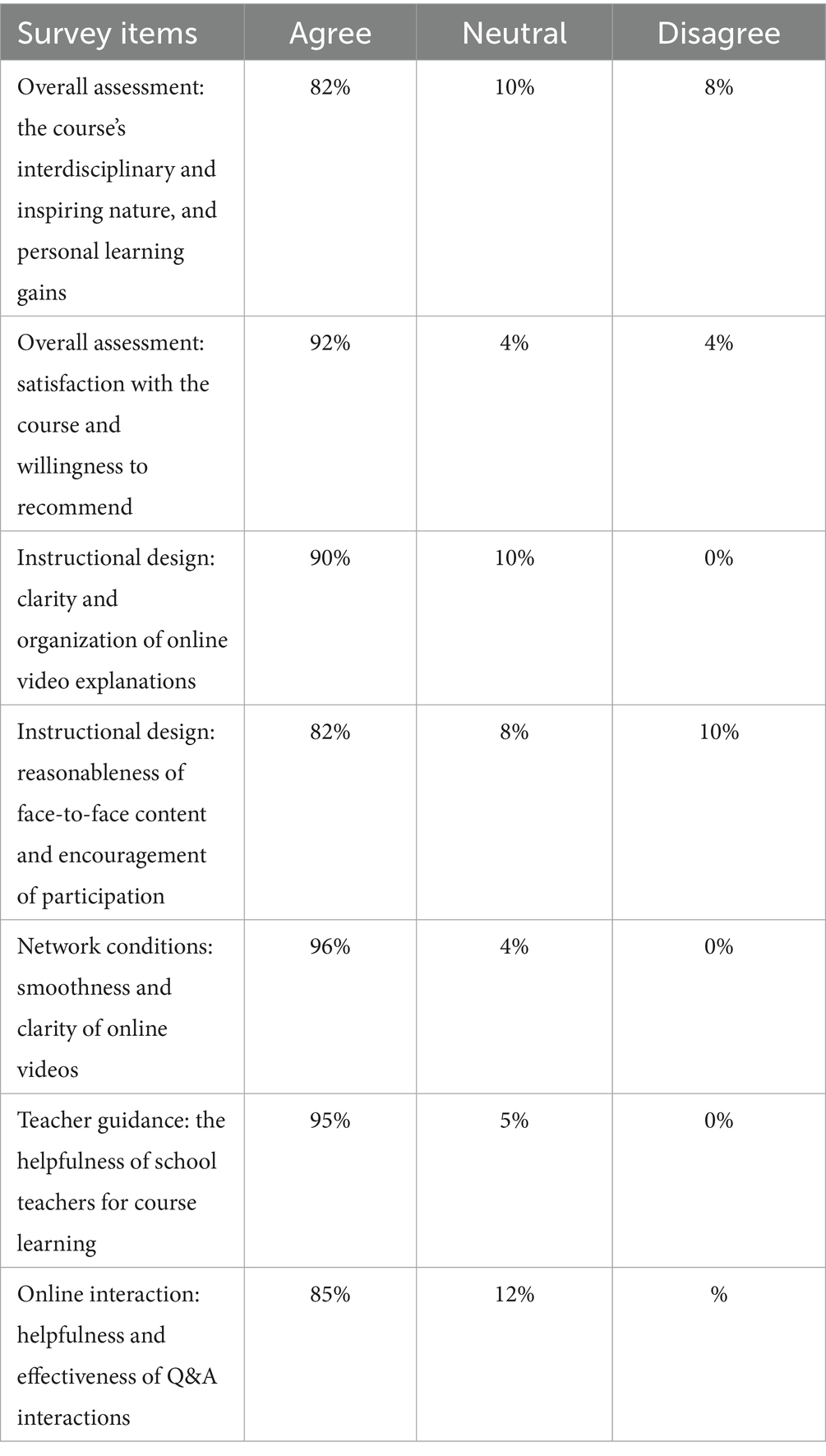

In addition, we conducted an anonymous survey of 800 students participating in the online course, with a primary focus on their learning experiences and satisfaction with the course. Table 5 illustrates the students’ perception of using the MOOC course and the 5E deep learning intelligent teaching method. From Table 8, it is evident that students are satisfied with the course experience. For instance, a majority (90%) of students find the overall explanations in the videos to be clear, well-organized, and logically designed, with engaging presentations that encourage active student participation. The majority (82%) also believe that the course content is informative and inspirational, with 92% expressing willingness to recommend the course to others.

Additionally, a significant proportion (85%) of students consider the response time prompt effective, with a notable subset finding it particularly helpful. Furthermore, based on student feedback, there is a desire to enhance participation in live interactions during face-to-face sessions at partner schools. We plan to implement improvements in this regard in future course iterations.

6.2 Impact at home and abroad

The teaching team has consistently prioritized the dissemination and exchange of teaching innovations, with the goal of advancing higher education and remote sensing pedagogy. Therefore, they actively participate in teaching seminars, competitions, and evaluations domestically and internationally. Specific data is outlined in Table 9, highlighting achievements such as the first prize in the national lecture competition, the second prize for outstanding teaching cases in Shandong Province, and recognition for Shandong Province’s top undergraduate courses.

The team also made a featured presentation titled “Innovative Design and Implementation of Ocean Remote Sensing Teaching Integrating Digital Technology” at the Teaching Innovation Forum of the First National Coastal Remote Sensing Conference. Additionally, in November 2022, they conducted a live broadcast of the “Ocean Remote Sensing” course at the “Belt and Road” International Geoinformation Training Center, serving over 60 countries globally (Figure 15). This facilitated the exchange and presentation of teaching reform experiences with counterparts both domestically and internationally, leading to significant progress.

6.3 Theoretical and practical innovations

This study contributes to both the theoretical framework and practical implementation of intelligent education, particularly in the field of remote sensing. By integrating constructivist learning theory with AI-driven learning analytics, the research forms a new data-informed teaching paradigm that supports active, reflective, and personalized learning processes.

1. 1 Theoretical innovations

(1) The study establishes a hybrid theoretical framework that connects constructivism and data-driven learning theory, bridging the gap between traditional human-centered pedagogy and intelligent adaptive instruction.

(2) It conceptualizes AI as a cognitive scaffold, transforming the role of technology from a passive tool to an active co-constructor of knowledge.

(3) The integration of learning analytics into the 5E model (Engage–Explore–Explain–Elaborate–Evaluate) provides a systematic approach to monitor and optimize learning dynamics, ensuring deep learning outcomes.

2 Practical innovations

(1) The study develops a Digital Experimental Teaching System, embedding neural network algorithms (BP, GA-BP, WOA-BP) into remote sensing data analysis tasks. This system demonstrates the feasibility of applying AI-based feedback in professional domain teaching.

(2) It introduces a data-driven feedback loop that continuously improves teaching design, student engagement, and learning assessment through adaptive data insights.

(3) The study provides a replicable model for other engineering and data-intensive disciplines, offering a reference for universities promoting AI-enabled teaching transformation.

Future studies could: (1) include randomized control groups for stronger causal validity (2) examine long-term learning retention and transfer (3) explore different AI analytics tools and broader disciplinary contexts (4) investigate students’ cognitive and affective processes in depth These directions will help further refine intelligent pedagogy and expand research impact.

6.4 Limitation of experimental design

This study adopted a quasi-experimental design because a synchronous physical control group was not feasible due to curriculum scheduling and the mandatory nature of the course. According to Ishtiaq and Creswell (2014), quasi-experimental designs are appropriate in educational settings where random assignment is not possible. Therefore, historical cohort data from previous semesters were used as a reference baseline for comparison. Although this approach enables practical implementation in real educational environments, it may introduce uncontrolled external variables, such as differences in student motivation or instructor experience. Future research will incorporate parallel control groups across multiple classes or universities to strengthen causal inference.

6.5 Potential bias and generalizability

The student satisfaction data were obtained through self-reported surveys, which may introduce response bias such as social desirability or acquiescence bias. To mitigate this issue, surveys were conducted anonymously, and participation did not affect academic grades. Nevertheless, subjective bias may still exist.

Additionally, the study was conducted at a single university in China, which may affect the generalizability of results to other cultural or institutional contexts. Future studies will involve multi-institutional collaboration and cross-cultural validation to enhance external validity.

7 Conclusion

This paper proposes using constructivist teaching theory to guide scientific instructional design, creating an intelligent teaching model based on 5E deep learning, which incorporates artificial intelligence and big data technology. Firstly, empowered by AI, we aim to combine industry and education, integrate science and education, and use competitions to build an experimental teaching system that encourages autonomous exploration. Secondly, we reconstruct the teaching content and make multiple high-quality teaching resources available online. Thirdly, based on artificial intelligence technology and big data, we scientifically design a teaching structure that breaks the limitations of time and space, realizing the intelligent teaching model of 5E deep learning. Fourthly, through AI software that records learning process data, we obtain individualized learning reports for students, enabling fine-grained teaching evaluation and timely feedback, as well as conducting retrospective analysis and continuous improvement of teaching.

In this intelligent teaching process, we have achieved the following results in student skill development and teaching effectiveness: (1) The average exam score of students has increased from 78.35 to 83.61, representing a 5.26-point improvement. The percentage of students with excellent grades has increased by 6.15%, the percentage of students with satisfactory grades has increased by 14.24%, and the failure rate has decreased by 6.66%. Students have undertaken 39 provincial-level and above innovative and entrepreneurial projects, published 293 academic papers, obtained 17 authorized invention patents, and won 529 awards. This reflects the effectiveness of our teaching strategies in enhancing students’ learning motivation, self-directed learning skills, and innovative practical competencies. (2) We have developed high-quality provincial-level online courses and continuously provide online teaching services to more than 30 universities and approximately 900 learners in society. (3) We have disseminated our teaching experience through global live lectures, conference exchanges, and news publicity, among other means, to promote the development of education and professional disciplines.

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of an AI-supported 5E instructional model in improving learning outcomes in remote sensing education. The results demonstrate significant improvements in academic performance and learner satisfaction. This study contributes practical evidence to AI-assisted blended learning design in higher education.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. FY: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FF: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was partially funded by CNPq (Grant Nos. 403612/2020-9, 311470/2021-1, 403827/2021-3, and 306199/2025-4), by Minas Gerais Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) (Grant Nos. PPE-00124-23, APQ-04523-23, APQ-05305-23, and APQ-03162-24), by the Brazil 6G project (1245.010604/2020-14), supported by RNP and MCTI, and by the projects XGM-AFCCT-2024-2-5-1 and XGM-AFCCT-2024-9-1-1 supported by xGMobile - EMBRAPII-Inatel Com-petence Center on 5G and 6G Networks, with financial resources from the PPI IoT/Manufatura 4.0 from MCTI grant number 052/2023, signed with EMBRAPII. Shandong Province Undergraduate Teaching Reform Research General Project (M2022220), the Distinguished Teachers Training Plan Program of Shandong University of Science and Technology (MS20231205) and the Ministry of Education, the industry university.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Albergel, C., Dorigo, W. A., Balsamo, G., Dorigo, W., Muñoz-Sabater, J., de Rosnay, P., et al. (2013). Monitoring multi-decadal satellite earth observation of soil moisture products through land surface reanalyses. Remote Sens. Environ. 138, 77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2013.07.009

Aljarah, I., Faris, H., and Mirjalili, S. (2016). Optimizing connection weights in neural networks using the whale optimization algorithm. Soft. Comput. 22, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00500-016-2442-1

Alvarez-Vanhard, E., Houet, T., Mony, C., Lecoq, L., and Corpetti, T. (2020). Can UAVs fill the gap between in situ surveys and satellites for habitat mapping? Remote Sens. Environ. 243:111536. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2020.111780

Babaeian, B., Sadeghi, M., Jones, S. B., Montzka, C., Vereecken, H., and Tuller, M. (2019). Ground, proximal, and satellite remote sensing of soil moisture. Rev. Geophys. 57, 530–616. doi: 10.1029/2018RG000618

Bai, Q., Feng, Y. M., Shen, S. S., and Li, Y. (2020). Reviewing and reappraising: Piaget’s genetic constructivism and learning theory from his perspective. J. East China Normal Univ. 38, 106–116. doi: 10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2020.03.010

Bozzano, F., Esposito, C., Franchi, S., Mazzanti, P., Perissin, D., Rocca, A., et al. (2015). Understanding the subsidence process of a quaternary plain by combining geological and hydrogeological modelling with satellite InSAR data: the Acque Albule plain case study. Remote Sens. Environ. 168, 219–238. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2015.07.010

Bybee, R. W., Taylor, J. A., Gardner, A., Van Scotter, P., Powell, J. C., Westbrook, A., et al. (2006). “The BSCS 5E Instructional Model: Origins and Effectiveness” in A Report Prepared for the Office of Science Education National Institutes of Health, BSCS (Colorado Springs, CO: BSCS), 1–43.

Campbell, D. T., and Stanley, J. C. (2015). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. New York, NY: Raven Books.

Castro, C. C., Gómez, J. A., Delgado Martín, J., Hinojo Sánchez, B. A., Cereijo Arango, J. L., Cheda Tuya, F. A., et al. (2020). An UAV and satellite multispectral data approach to monitor water quality in small reservoirs. Remote Sens 12:1514. doi: 10.3390/rs12091514

Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, State Council, China (2020) Overall plan for deepening the reform of educational evaluation in the new era. Beijing: Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council.

Chand, T. R. K., Badarinath, K. V. S., Prasad, V. K., Murthy, M. S. R., Elvidge, C. D., and Tuttle, B. T. (2019). Monitoring forest fires over the Indian region using Defense meteorological satellite program - operational line scan system nighttime satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 103, 165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2006.03.010

Chassignol, M., Khoroshavin, A., Klimova, A., and Bilyatdinova, A. (2018). Artificial intelligence trends in education: a narrative overview. Proc. Comput. Sci. 136, 16–24. doi: 10.1016/J.PROCS.2018.08.233

Chen, Y. J., Su, W. J., Xing, C. Z., Chen, Y., Su, W., Xing, C., et al. (2022). Kilometer-level glyoxal retrieval via satellite for anthropogenic volatile organic compound emission source and secondary organic aerosol formation identification. Remote Sens. Environ. 270:112852. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2021.112852

China Remote Sensing Application Development Blue Book, China remote sensing application association, 3rd Conference on Spatial Information Technology Applications, Hunan, China, (2023).

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Devedzic, V. (2004). Web intelligence and artificial intelligence in education. Educ. Technol. Soc. 7, 29–39. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220374721_Web_Intelligence_and_Artificial_Intelligence_in_Education

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Field, C. B., Appel, E. A., Azevedo, I. L., Baldocchi, D. D., Burke, M., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 lockdowns: a window into the earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 470–481. doi: 10.1038/s43017-020-0079-1

D'Mello, S., Lehman, B., Sullins, J., Daigle, R., Combs, R., Vogt, K., et al. (2010). A time for emoting: when affect-sensitivity is and isn't effective at promoting deep learning. Lecture Notes Comput. Sci. 6094:388. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-13388-6_29

Duan, R. L. (2021). Research on accurate teaching evaluation for learning process in a data-based learning environment. Chinese J. Multimedia Netw. Teach. 7, 53–55.

Duran, L. B., and Duran, E. (2004). The 5E instructional model: a learning cycle approach for inquiry-based science teaching. Sci. Educ. Rev. 3, 49–58. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1058007.pdf

Fauvel, M., Lopes, M., Dubo, T., Rivers-Moore, J., Frison, P.-L., Gross, N., et al. (2020). Prediction of plant diversity in grasslands using sentinel - 1 and - 2 satellite image time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 237:111536. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.111536

He, K. K. (1998). Constructivism: the theoretical basis for renovating traditional teaching (I). Discipl. Educ. 3, 29–31.

Heredia-Negrón, F., Tosado-Rodríguez, E. L., Meléndez-Berrios, J., Nieves, B., Amaya-Ardila, C. P., and Roche-Lima, A. (2024). Assessing the impact of AI education on Hispanic healthcare professionals' perceptions and knowledge. Educ Sci 14:339. doi: 10.3390/educsci14040339,

Hinojo-Lucena, F.-J., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M.-P., and Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M. (2019). Artificial intelligence in higher education: a bibliometric study on its impact in the scientific literature. Educ. Sci. 9:51. doi: 10.3390/educsci9010051

Hinostroza, J. E., Armstrong-Gallegos, S., and Villafaena, M. (2024). Roles of digital technologies in the implementation of inquiry-based learning (IBL): a systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 9:100874. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.100874

Huang, Q., Long, D., Han, Z., and Han, P. (2022). High - resolution satellite images combined with hydrological modeling derive river discharge for headwaters: a step to ward discharge estimation in ungauged basins. Remote Sens. Environ. 277:113030. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113030

Ignatov, A., Timofte, R., Chou, W., and Wang, K., Wu, M., Hartley, T., and Van Gool, L. (2018). “AI benchmark: running deep neural networks on android smartphones,” Computer vision – ECCV 2018 workshops, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. pp. 288–314. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.01109

Ishtiaq, M., and Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kahraman, H.T., Sagiroglu, S., and Colak, I., “Development of adaptive and intelligent web-based educational systems,” (2010) 4th International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technologies, pp. 1–5, 2010.

Kalluri, S., Gilruth, P., Rogers, D., and Szczur, M. (2007). Surveillance of arthropod vector-borne infectious diseases using remote sensing techniques: a review. PLoS Pathog. 3, 1361–1371. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030116,

Kim, B. Social constructivism emerging perspectives on learning, teaching and technology, (2001) Available online at: http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/ (Accessed May 11, 2025).

Lee, H. J., Kuwayama, T., and Fitzgibbon, M. (2023). Trends of ambient O3 levels associated with O3 precursor gases and meteorology in California: synergies from ground and satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 284:113358. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113358

Liu, X. F., Lan, G. S., and Wei, J. C. (2022). Digital transformation of education boosts the future of higher education teaching: macro trends, technology practices and future scenarios—key points and thoughts of the 2022 EDUCAUSE horizon report. J. Soochow Univ. 2, 115–118. doi: 10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2019.02.008

Liu, Z. J., Liu, A., Liu, Z., Wang, C., and Niu, Z. (2004). Evolving neural network using real coded genetic algorithm (GA) for multispectral image classification. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 20, 1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2003.11.024

Marchetti, D., De Santis, A., D'Arcangelo, S., Poggio, F., Piscini, A., Campuzano, S. A., et al. (2019). Pre-pre-earthquake chain processes detected from ground to satellite altitude in preparation of the 2016 - 2017 seismic sequence in Central Italy. Remote Sens. Environ. 229, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.04.033

Marra, F., Morin, E., Peleg, N., Mei, Y., and Anagnostou, E. N. (2017). Intensity - duration - frequency curves from remote sensing rainfall estimates: comparing satellite and weather radar over the eastern Mediterranean. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 2389–2404. doi: 10.5194/hess-21-2389-2017

Marton, F., and Saljo, R. (2020). On qualitative differences in learning II: outcome as a function of the learner’s conception of the task. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 46, 106–116. doi: 10.1111/J.2044-8279.1976.TB02304.X

Mikropoulos, T. A., and Natsis, A. (2010). Educational virtual environments: a ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009). Comput. Educ. 56, 769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.10.020

Minner, D. D., Levy, A. J., and Century, J. (2010). Inquiry-based science instruction-what is it and does it matter? Results from a research synthesis years 1984 to 2002. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 47, 474–496. doi: 10.1002/tea.20347

Mirjalili, S. M., and Lewis, A. (2016). The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67. doi: 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008

Nakamura, K., Wakabayashi, H., Naoki, K., Nishio, F., Moriyama, T., and Uratsuka, S. (2005). Observation of sea-ice thickness in the Sea of Okhotsk by using dual-frequency and fully polarimetric airborne SAR (pi-SAR) data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 43, 2460–2469. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2005.853928

Peredo, R., Canales, A., Menchaca, A., and Peredo, I. (2011). Intelligent web-based education system for adaptive learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 38, 14690–14702. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.05.013

Ren, Y. Q. (2002). The philosophical sociological origins of constructivist learning XI theory. Global Educ. Outlook 1, 15–19.

Shen, H. D. (2015). Current situation, problems and suggestions of informatization teaching practice of vocational education. China Vocat. Tech. Educ. 33, 90–95.

Sicard, M., Granados-Muñoz, M. J., Alados-Arboledas, L., Barragán, R., Bedoya-Velásquez, A. E., Benavent-Oltra, J. A., et al. (2019). Ground/ space, passive/ active remote sensing observations coupled with particle dispersion modelling to understand the inter-continental transport of wildfire smoke plumes. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111294–111481. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.111294,

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Tavakol, M., and Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd,

Timms, M. J. (2016). Letting artificial intelligence in education out of the box: educational cobots and smart classrooms. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Edu. 26, 701–712. doi: 10.1007/s40593-016-0095-y

Ulaby, F. T. (2018). Introduction to satellite remote sensing: atmosphere, ocean, land, and cryosphere applications. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 6, 109–110. doi: 10.1109/MGRS.2018.2873040

Wang, J., Ma, A., Zhong, Y., Zheng, Z., and Zhang, L. (2022). Cross-sensor domain adaptation for high spatial resolution urban land-cover mapping: from airborne to spaceborne imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 277:113058. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113058

Xu, L., Abbaszadeh, P., Moradkhani, H., Chen, N., and Zhang, X. (2020). Continental drought monitoring using satellite soil moisture, data assimilation and an integrated drought index. Remote Sens. Environ. 250:112028. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2020.112028

Yan, X., Zang, Z., Luo, N. N., Luo, N., Jiang, Y., and Li, Z. (2020). New interpretable deep learning model to monitor real-time PM2.5 concentrations from satellite data. Environ. Int. 144:106060. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106060,

Yang, Y., Li, J., Xu, J., Tang, J., Guo, H., and He, H. (2011). Contribution of the compass satellite navigation system to global PNT users. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 2813–2819. doi: 10.1007/S11434-011-4627-4

Zakhvatkina, N. Y., and Bychkova, I. A. (2015). Bayesian classification of the ice cover of the Arctic seas. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 51, 883–888. doi: 10.1134/S0001433815090212

Zhang, Y. D., Chen, G., Zhang, Y., Myint, S. W., Zhou, Y., Hay, G. J., et al. (2022). Urbanwatch: a 1-meter resolution land cover and land use database for 22 major cities in the United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 278:113106. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113106

Zhang, X., Zhou, J., Liang, S., Chai, D., and Liu, J. (2020). Estimation of 1-km all - weather remotely sensed land surface temperature based on reconstructed spatial - seamless satellite passive micro wave temperature and thermal infrared data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 167, 2321–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.07.014

Zhao, Z. T. (2001). Constructivism: a poststructuralist xi theory. Journal of Nantong Normal university. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2, 117–121. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-2359.2001.02.025

Keywords: smart teaching model, artificial intelligence (AI), big data, 5E deep learning, remote sensing education, constructivist learning theory, student engagement

Citation: Zhan L, Yang F, Zhu H, Wang W, Yasir M and de Figueiredo FAP (2025) Design and implementation of an intelligent teaching model based on artificial intelligence and data-driven approaches. Front. Educ. 10:1694663. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1694663

Edited by:

Amr Abdullatif Yassin, Ibb University, YemenReviewed by:

Minju Hong, University of Arkansas, United StatesMohammed Abdulkareem Alkamel, Ibb University, Yemen

Yousef Qasem, Accenture, United States

Copyright © 2025 Zhan, Yang, Zhu, Wang, Yasir and de Figueiredo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felipe A. P. de Figueiredo, RmVsaXBlLmZpZ3VlaXJlZG9AaW5hdGVsLmJy

Lili Zhan1