- 1Department of Education, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

- 2Surgical, Medical, Dental and Morphological Sciences Department, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

- 3Department of Education, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy

- 4School of Education, St. Thomas University, Fredericton, NB, Canada

Formative assessment is widely accepted as an essential strategy that teachers of all levels should know and use. At the secondary education level, a crucial stage in learner development, teachers are expected to actively incorporate formative assessment strategies into their subject-specific teaching and to create learning environments that consider both the teaching methods and the specific content being taught. This study reports findings from a continuing professional development (CPD) program that was designed to train in-service secondary school subject teachers to implement formative assessment strategies in their teaching practice. The main purpose of this study was to analyze the effectiveness of a CPD program about formative assessment to support teachers’ professional development. The program was developed throughout the school year 2024/25, using an action research framework to involve teachers in planning, acting, observing and reflecting on their own assessment strategies. The study involved 26 teachers who planned both self- and peer-assessment activities in their upper secondary classrooms. During and after the CPD program, teachers completed two questionnaires focused on two main issues: firstly, they had to reflect on the effectiveness of the formative assessment strategies implemented in their classrooms. Secondly, they had to consider whether the action research CPD program supported their own professional development. Findings indicate that teachers perceived formative assessment as a valuable strategy for planning activities to increase students’ cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective skills. Additionally, teachers reported that the CPD program improved both their formative assessment capacity and their skills in pedagogical content knowledge.

1 Introduction

The history of contemporary formative assessment can be traced to Scriven (1967), who first used the expression ‘formative evaluation’ to represent the ongoing improvement of curriculum at the school level (Black and Wiliam, 2003). Bloom et al. (1971)extended the concept of formative evaluation from curriculum to content: specifically through the implementation of ongoing tasks designed to reveal students’ mastery of content and identify gaps in learning. With the more focused attention on students’ ability to achieve learning objectives prior to a summative assessment, the origins of current formative assessment practices were established. Distinguishing between formative and summative assessment, with the former aimed at identifying learning objectives obtained during instructional phases and the latter linked to the end of instructional units/courses (Bloom et al., 1971) was a key educational development. This distinction set the foundation for formative strategies aimed at involving students in the improvement of their own learning and academic performance through ongoing classroom assessment and feedback (Black and Wiliam, 1998).

An early empirical study of the effectiveness of formative assessment experiences in teaching secondary subject matter was carried out by Hart (1981), and focused on “the diagnosis of errors in the concepts formed by secondary school students” (Black and Wiliam, 2003, p. 624). In the following decades, formative assessment spread rapidly at all educational levels from primary to higher education. More recently, a 2023 policy and practice report (European Commission et al., 2023) underlined the importance of applying formative assessment strategies in order to strengthen and support the development of learners’ competences.

This study is focused on a continuing professional development (CPD) program designed to train in-service subject teachers in formative assessment strategies for everyday classroom activities. A school-based action research framework was chosen to allow teachers to plan, apply, observe, and reflect (Kemmis et al., 2014) on their own teaching strategies and test the effectiveness of their practices. Teachers were asked to plan self- and peer-assessment activities, apply these strategies in their secondary classes, and observe and reflect on their actions. Two main areas provided insight: firstly, teachers had to reflect on the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies applied in their classrooms. Secondly, they had to reflect on the CPD program and verify if the action research framework actually supported their own professional development.

This study was carried out in secondary schools in an effort to investigate action research as an effective practice for training teachers with high levels of content knowledge. Teachers of this school level are subject specialists who are highly capable of applying their subject-specific knowledge (Jeschke et al., 2021; Kroksmark, 2015; Ligozat et al., 2015) but can struggle to connect their content knowledge with pedagogical knowledge. Secondary teachers can receive less pedagogical training on how to apply several methodological approaches and strategies within their instructional activities (Almunawaroh and Steklács, 2025; Mapulanga et al., 2024; Mizzi, 2024). Our study design has the potential to provide insight on whether action research can support the effective integration of content and pedagogical knowledge, thereby generating deeper pedagogical content knowledge (Almonacid-Fierro et al., 2023; Fukaya et al., 2025; Star, 2023).

2 Literature review

Our study adopted a school-based action research model of CPD to allow in-service teachers to reflect on their everyday assessment practices and improve them through experimentation with formative assessment strategies focused on student learning. In the following sections, we highlight supporting literature that informs our conceptual and methodological approach to this research.

2.1 Continuing professional development (CPD) for in-service teachers

It is important to differentiate between educating pre-service and training in-service teachers. The World Bank (2019) highlighted that programs for pre- and in-service teachers are “conceptually different but linked, with preservice training following a logical progression through a series of steps, each of which has a singular purpose and specific quality characteristics. In-service training, by nature, is not sequential, can serve a variety of purposes, and encompasses a cluster of quality drivers, all of which need to be addressed to some degree to ensure success” (2019, p. 4). In recent years, several studies have emphasized the differences between pre- and in-service teachers across topics: use of ICT (Jenßen et al., 2023), global competence (Zhang et al., 2024), readiness and self-competency (Polat, 2010).

Teaching is a vocation characterized by lifelong learning (Birenbaum and Rosenau, 2006) and the development of a professional identity that occurs across career stages (Yağan et al., 2022). Teachers are not merely technicians who apply teaching techniques, but professionals whose ongoing learning should be aimed at nurturing the expert within (Dadds, 1997). A CPD program should attend “to the development of teachers’ understanding of learning, to their sense of voice, their judgement and their confidence to cultivate inner expertise as a basis for teaching and for judging outsider initiatives” (1997, p. 31).

There is an asymmetric background between pre- and in-service teachers (Kervinen et al., 2022). In-service teachers, compared to pre-service teachers, already have professional experiences from which they can identify specific training needs (Guerrero-Romera and Perez-Ortiz, 2022) and are more likely to engage in deep learning than pre-service teachers to meet these needs (Birenbaum and Rosenau, 2006). Therefore, with experienced teachers it is beneficial to create professional relationships between researchers and teachers based on a bottom-up perspective (Bergmark, 2023) that values and engages with their professional goals and teaching experiences (Parr et al., 2021).

According to Eraut (1994), the development of teachers’ professional knowledge can occur in three main contexts: in university within an academic context, during an institutional discussion to define the relationship between policy and practice, and in the school context where the teachers can practice directly. Kennedy (2005) listed a series of models in which continuing professional development (CPD) can be carried out: training; award-bearing; deficit; cascade; standards-based; coaching/mentoring; community of practice; action research; transformative. Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) note that professional development programs can be defined as and are effective when teachers can experiment with changes in their knowledge and professional practices and develop instructional strategies that can improve student learning outcomes.

In recent years, research on CPD for subject teachers in various contexts has reinforced the importance of ongoing professional learning and provided insights for effective CPD practices. In-service teachers are adult learners whose participation in CPD can be voluntary or required, but ultimately CPD should leverage independence, self-direction and goal-directed learning to increase the participation of teachers in enhancing their own teaching quality (Njenga, 2023). Through the lens of sociocultural theory, Abakah’s (2023) study of CPD asserts the importance of grounding CPD in realistic learning experiences that enable teachers to contextualize and implement new knowledge in authentic classroom situations (Wilkinson et al., 2014). Additionally, CPD should improve the pedagogical skills of teachers (Okumu and Opio, 2023), the academic performance of students (Ngendahayo et al., 2023), and an overall improvement of instructional quality in secondary schools (Dulo, 2022). Ultimately, the core of CPD is to improve teacher learning and build greater capacity for educational quality in context (Abakah, 2023). Abakah et al. (2022) reinforce this point, affirming that the professional development of teachers, when supported by effective CPD programs, represents an important and valuable approach for improving the quality of teaching and learning within schools.

2.2 Action research within CPD for subject teachers

Action research has its origins in the work of social psychologist Kurt Lewin. Tracing the history of action research, Adelman (1993) reports how Lewin and his collaborators conducted workplace experiments that showed how workers increased their productivity through discussions and active problem solving. From an educational point of view, Lewin (1946) supported teachers and schools with strategies that enabled them to be active agents of cooperative change within the community. It was Lewin’s belief that “Action research must include the active participation by those who have to carry out the work in the exploration of problems that they identify and anticipate” (Adelman, 1993, p. 8).

Within an educational context, action research serves as a basis for teacher-designed studies of educational issues, with the goal of enhancing professional development through activities enacted in their own classrooms (Parsons and Brown, 2002). This format of practical research carried out in real contexts gave rise to the concept of teacher-as-researcher (La Velle, 2024). The teacher takes on the role of researcher through a five step pedagogic cycle of understanding, preparing, instructing, assessing, and reflecting (La Velle and Newman, 2022).

This cycle can be carried out autonomously by teachers but it can be also supported by a strong relationship and collaboration with academic researchers (Aussems et al., 2024). Together, teachers and researchers can define the problem, the research questions, the actions to be carried out, the data to be collected and the instruments to be used. In the scientific literature, we can find several models of action research in secondary education (Johannesson and Olin, 2024; Rabgay and Kidman, 2024). The ‘classroom action research’ (CAR) model was introduced by Kemmis et al. (2014) and is particularly interesting because it combines the improvement of teaching and learning practices together with scientific results to verify the quality of research results. The CAR model includes four steps: planning, action, observing, and reflecting. While some CPD models are merely transmissive, Kennedy (2005) underlines how action research can represent a transformative model for CPD because it allows teachers to face critical questions and try to find feasible and effective solutions through a process that enhances their professional autonomy.

CPD based on action research offers intentional approaches to changing teaching (Manfra, 2019) since it requires high levels of autonomy for practitioner-researchers, and a collaborative view of knowledge (Cain and Milovic, 2010). A CPD program based on action research is naturally collaborative in the sense that teachers collaborate among them to deeply understand an educational situation and try to find good solutions (Crawford, 2022; Hanfstingl and Pflaum, 2022). Additionally, an action research model of CPD can enhance the improvement of research competences developed by teachers (Bergmark, 2023; Osmanović Zajić et al., 2021). Through action research as CPD, teachers learn the structure of a study in order to observe, plan, collect data, and modify their teaching strategies (Cierpiałowska, 2023). Through enhanced research and pedagogical understanding, action research as CPD can be viewed as a critical platform for advocating change (Shaik-Abdullah et al., 2020).

Some of the literature on CPD programs has focused on its effectiveness in individual subjects, such as physics (Etkina et al., 2009), second language (De Neve et al., 2022), chemistry (Vogelzang and Admiraal, 2017), and mathematics (Kyaruzi et al., 2019). Other studies have demonstrated the connection of CPD with cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective skills such as co-regulated learning (Veugen et al., 2024) and decision-making (Van Der Steen et al., 2022). There is ample supporting literature in different areas of secondary education to demonstrate how CPD programs based on the action research framework have been effective.

2.3 Training in-service subject teachers

The OECD (2025) created the ‘Schools+ teaching taxonomy’ aimed at identifying the building blocks of high-quality teaching. One of these points is dedicated to the quality of subject content that “includes both building a deep understanding around propositional knowledge (information and facts that can be captured and expressed in spoken or written sentences) and ways of doing subjects (including explicit procedures and wider tacit knowledge). It also encompasses students working with connections, patterns and generalizations in the content, and across content” (OECD, 2025, p. 72). Therefore, the role of subject teachers in the creation of a learning environment where students can achieve high-quality subject content is crucial. Compared to primary education, subject teachers usually teach individual subjects to their classes (Wettstein et al., 2021) and are interested in the subject matter they teach (Havia et al., 2023). Subject teachers have to be able to blend propositional knowledge, or subject-specific content, with tacit procedural and methodological knowledge, or the ways of doing a subject. This expertise is necessary both within and across content areas, requiring them to build a cognitive space where students can connect the multidimensional characteristics of multiple subjects. This high level of content and pedagogical knowledge is part of the ongoing learning of subject teachers, who are expected to develop a professional identity that bridges the gap between theory and practice and to find the balance between subject studies and pedagogical studies (European Commission, 2007).

In 1987, Shulman defined this educational skill as Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) which was “the blending of content and pedagogy into an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organized, represented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented for instruction” (Shulman, 1987, p. 8). The concept of PCK represents the development and point of contact between the subject-specific content knowledge (CK) and the pedagogical knowledge (PK) of a subject teacher. Extending this definition, Park and Oliver (2008) specified that “PCK is teachers’ understanding and enactment of how to help a group of students understand specific subject matter using multiple instructional strategies, representations, and assessments while working within the contextual, cultural, and social limitations in the learning environment” (2008, p. 264). In this way, it is clear that PCK is not just a ‘technical’ issue through which teachers can be trained to use several teaching strategies (Depaepe et al., 2013) because subject teachers relate to the subjects in several ways through their knowledge, ideas, beliefs and emotions.

Subject teachers need not only CK, PK and PCK, but also an ability to apply this knowledge in teaching situations (Blömeke et al., 2015) and master demanding classroom situations (Jeschke et al., 2021). PCK is a multidimensional concept composed of several elements, such as: general pedagogical knowledge, knowledge of learners and educational contexts, and knowledge of educational ends, purposes and values (Niemelä, 2022). Additionally, the professional knowledge subject teachers must develop is complex. It is composed of the curricular, pupil, content, pedagogical, and evaluation knowledge that creates topic-specific professional knowledge (TSPK) as well as instructional strategies, content representations, pupil understanding and development, subject-specific practices, and habits of mind (Vázquez-Bernal et al., 2022).

Our study is focused on these challenging and interrelated areas of subject-specific content, pedagogical issues, and real instructional situations. Specifically, we believe that formative assessment could represent a key to enhance this dynamic connection and support the professional growth of in-service subject teachers (Estaji, 2024; Guerrero-Romera and Perez-Ortiz, 2022).

2.4 Effectiveness of formative assessment

The CPD program in our study focused on two formative assessment strategies: self- and peer-assessment. Within our research context, we knew this pedagogical approach to be particularly demanding for subject teachers to implement in their subject-specific activities.

From a technical point of view, self-assessment can be defined as an activity through which students can reflect on the quality of their own learning processes and outcomes (Panadero et al., 2016). Additionally, Andrade (2019) specified that the purpose of self-assessment is not to give a grade but to improve students’ capacity to give feedback, as portrayed by Wanner and Palmer (2018). Peer-assessment activities allow students to evaluate each other through several kinds of peer interactions. Through these activities and interactions students can learn together (Van Gennip et al. (2010) and enhance their work or learning strategies (Ketonen et al., 2020). Yin et al. (2022) described peer-assessment as an active process where deep interaction provides students opportunities to re-construct relevant and significant cognitive understanding in different contexts.

To measure the potential effectiveness of both formative assessment strategies, we focused our study on the development of a series of cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective skills, as suggested by Theobald (2021). From an affective standpoint, we supported teachers in examining how assessment can be connected to the development of students’ emotional and motivational capacities (Liu and Yu, 2021; Muho and Taraj, 2022; Renninger and Hidi, 2022; Rodriguez et al., 2020), resilience (Clipa et al., 2021) and self-efficacy (Meusen-Beekman et al., 2016). Concerning the behavioral changes, we supported teachers in observing improvements in effort regulation and learning time management, as suggested by Dever et al. (2023) and Karaca and Bektas (2022). Finally, teachers were asked to analyze some cognitive and metacognitive aspects, such as: self- reflection (Veugen et al., 2024), metacognitive awareness (Carney et al., 2022; Rajcoomar et al., 2024) and the aspects of self-regulation related to rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials (Lämsä et al., 2025; Martínez-López et al., 2023).

3 Context of the study and research questions

This study was conducted in 6 Italian upper secondary schools. The Italian educational system is composed of 13 grades split into three levels: primary school (1st to 5th grade), lower secondary school (6th to 8th grade) and upper secondary school (9th to 13th grade). In primary school, teachers have more generalized teacher preparation training and are not focused on specific subjects; however, both lower and upper secondary teachers have undergraduate or graduate degrees in and are specialized in teaching certain groups of subjects.

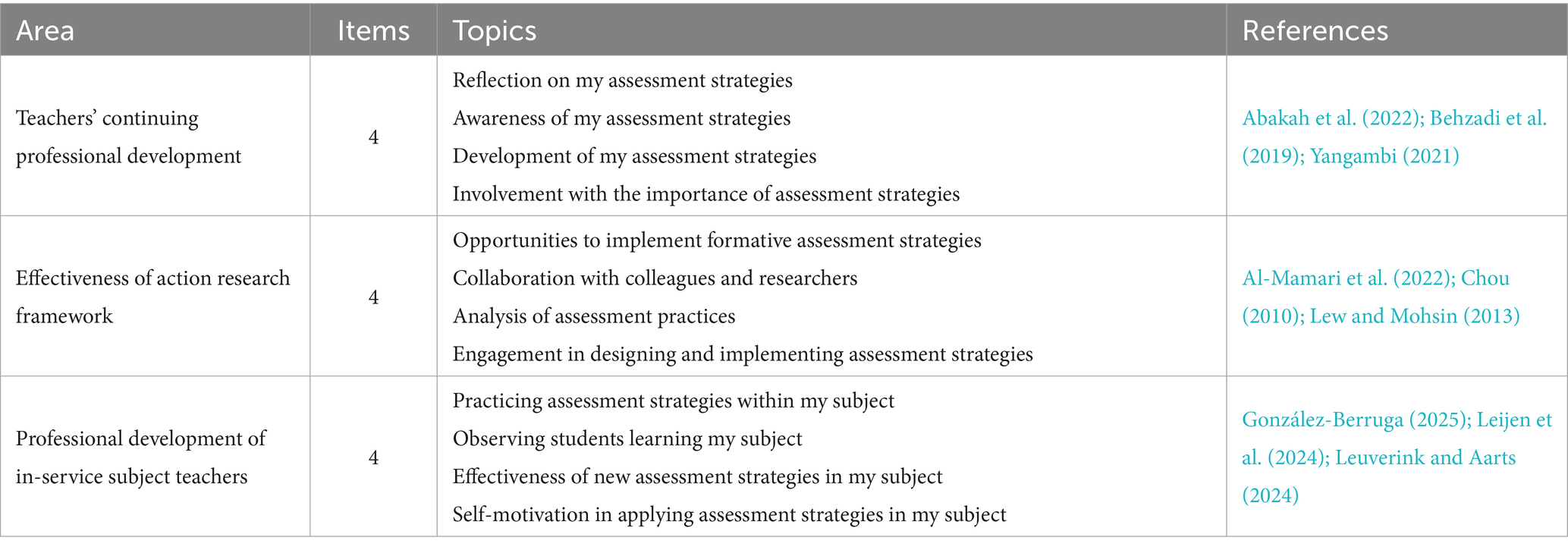

The overall purpose of this study was twofold: to investigate in-service subject teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of (a) classroom-based formative assessment strategies, and (b) an action-research CPD program to support their capacity with formative assessment. For the first aim, we identified six skills linked to cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective areas to measure the effectiveness of the formative assessment activities (Table 1). For the second aim, we sought to monitor the effectiveness of an action research CPD program focused on formative assessment. Our two main research questions (RQ) and sub-questions are expressed as follows:

RQ1: How did teachers perceive the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies in the development of the cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective skills listed in Table 1? In particular, did the use of self- and peer-assessment strategies help students: enhance their emotional, motivational, and resilience capacities (RQ1a); support their self-efficacy, self-reflection, and metacognitive awareness (RQ1b); foster their self-regulation competences both in learning time management and in rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials (RQ1c)?

RQ2: How effective is a CPD program on formative assessment in supporting teachers’ professional development? Specifically, how did an action research framework affect the capacity of teachers to experiment with, reflect on, and modify their own assessment strategies (RQ2a) and were subject teachers able to increase their pedagogical content knowledge through the application of formative assessment strategies (RQ2b)?

4 Research design

To answer the research questions, a mixed method research design was chosen. In particular, we adopted a multistrand design because the study included two phases (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2009). We collected both quantitative and qualitative data during each phase of the study concurrently, in line with Creswell et al. (2003) who noted that the interpretation of results can be based on the triangulation of both data types, with neither being prioritized over the other.

4.1 Participants, procedure, and instruments

4.1.1 Participants

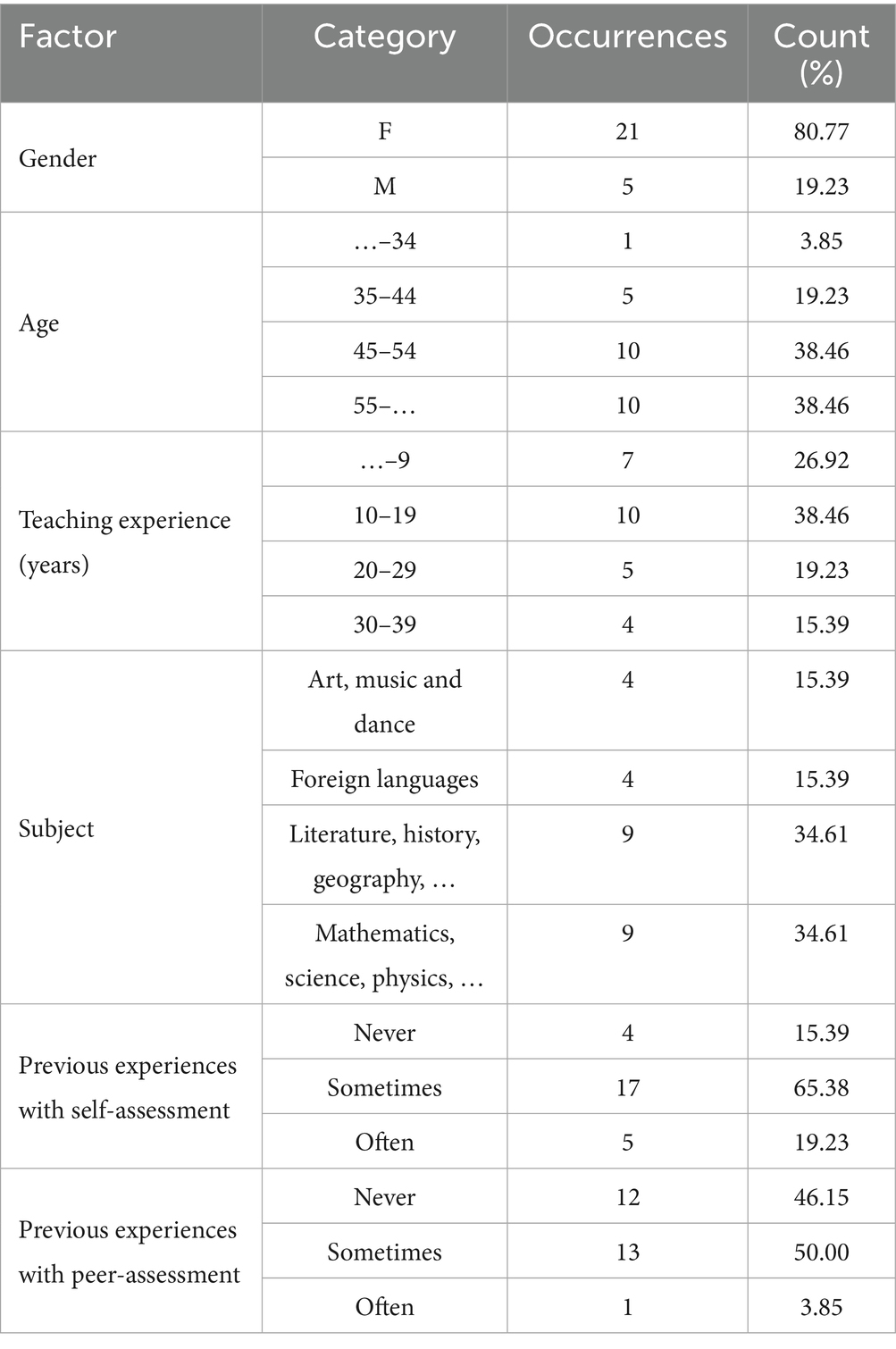

The recruitment of participants was based on a two-stage sampling procedure. The first stage was founded on the creation of clusters (Ahmed, 2024; Galway et al., 2012), whilst the second stage was based on a non-probabilistic self-selection procedure (Berndt, 2020; Stratton, 2023). Specifically, we established four initial clusters that represented the four provinces of the region where the University of Genoa is located. Then, we randomly selected 3 schools for each cluster. During the second stage, we sent an invitation to all teachers at the selected schools to participate in the research. Twenty-six teachers accepted the invitation to participate, and Table 2 shows their demographic and professional characteristics. It is interesting to highlight that many teachers had previous experiences with self-assessment (around 9 out of 10) but half of them had never had experiences with peer-assessment.

The principles of research ethics were strictly followed. All teachers involved in the study were informed about the aims, activities and procedures for the study. Participation was optional, and those who agreed to participate gave written informed consent.

4.1.2 Procedure

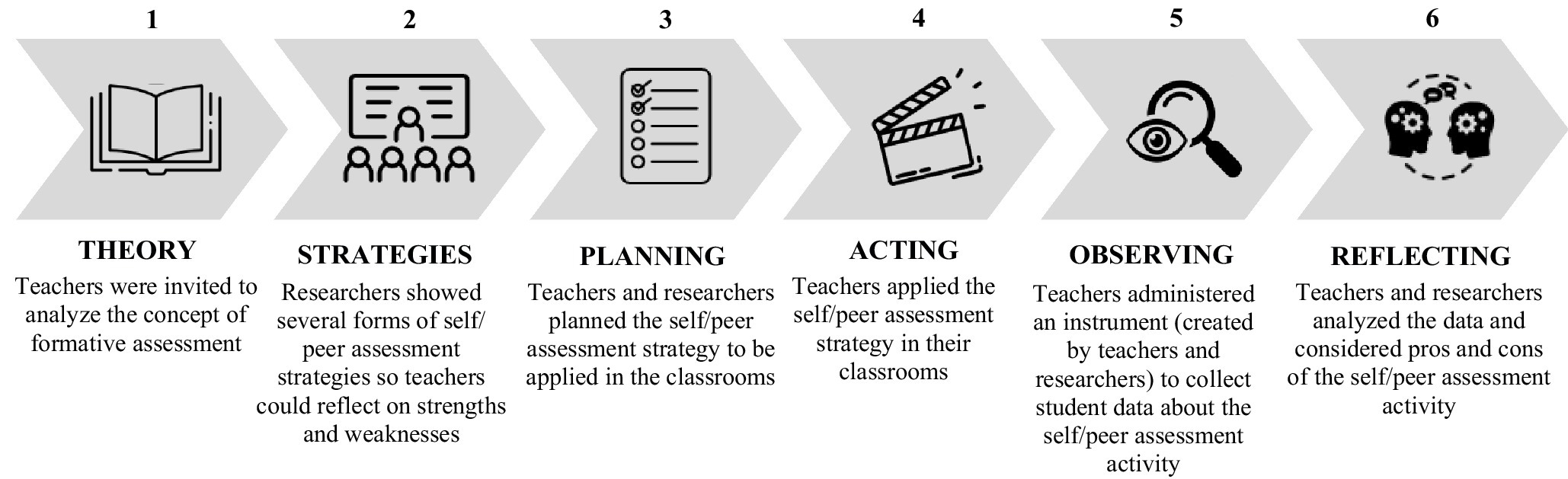

The CPD procedure was divided into two main phases. During the first phase, teachers were trained to use a self-assessment strategy through a six step procedure outlined in Figure 1. In the first step (Theory), researchers introduced the concept of formative assessment. Then, in the second step (Strategies), researchers presented several self- and peer-assessment approaches, underlining both strengths and weaknesses. During the third step (Planning), teachers and researchers collaboratively planned instructional activities based on self- and peer-assessment to be applied in the classrooms. Both activities were carried out by the teachers within their own classrooms in the fourth step (Acting). In the fifth step (Observing), teachers administered some instruments to collect the students’ ideas about the use of formative assessment, as indicated by Parmigiani et al. (2025a). Finally, in the sixth step (Reflecting), teachers and researchers reflected together on both students’ ideas and their own considerations, regarding strengths and limitations about the use of formative assessment at school.

The second phase engaged the same six step procedure but the topic and the training focused on peer-assessment strategies. After each phase, teachers were asked to complete a questionnaire focused on their perceptions of the effectiveness of self- and peer-assessment strategies, respectively (RQ1). After the completion of both phases and the end of the CPD, teachers were asked to complete an instrument focused on the CPD’s effectiveness on their professional development (RQ2).

4.1.3 Instruments

Two research instruments provided three data collection points. Both instruments are included in the Supplementary materials. The first questionnaire was administered twice, once after each of the self- and peer-assessment phases. This instrument was focused on teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies (RQ1). The questionnaire was composed of three sections. The first section included the demographic and professional characteristics of teachers as shown in Table 2. The second section comprised closed-ended questions related to the six respective skills identified in the research questions. Items from instruments in other international questionnaires were adapted for our research context. Table 1 shows the areas/sub-areas, the number of items, the topics and the references to these international questionnaires. Teachers rated items on a five-point Likert scale, from 5 (Yes, in my opinion, the self- (or peer-) assessment activity has been very useful/effective) to 1 (No, in my opinion, the self- (or peer-) assessment activity has not been useful/effective at all). Additionally, the third section contained an open-ended question: “In your opinion, did the self- (or peer-) assessment activity help students reflect and modify their own learning strategies? If so, in what ways? If not, how not?” We decided to add an open-ended question to allow teachers to more deeply describe their reflections on and perceptions of the application of formative assessment strategies.

The second instrument was administered at the end of the CPD program and teachers were asked their perceptions of the CPD’s strengths and weaknesses (RQ2). As with the first instrument, the first section comprised teachers’ demographic and professional characteristics. The second section included closed-ended questions related to three areas: (a) teachers’ continuing professional development in formative assessment, (b) the action research framework, and (c) the professional development of in-service subject teachers. Table 3 shows the areas, the number of items, the topics, and references to the international questionnaires. Teachers rated items on a five-point Likert scale, from 5 (Yes, the CPD program has been very useful/effective) to 1 (No, the CPD program has not been useful/effective at all). The third section was composed of 3 open-ended questions regarding the areas of formative assessment strategies, action research, and in-service CPD for subject teachers. The open-ended questions provided the opportunity for teachers to more deeply describe their perceptions of the CPD program.

5 Data analysis and findings

We performed both quantitative and qualitative data analysis. The qualitative responses generated by the open-ended questions were analyzed using Nvivo 14 software following three steps suggested by Al-Eisawi (2022): open coding, axial coding and selective coding. The quantitative data analysis was carried out using SPSS29. First of all, we performed the reliability analyses, using the following coefficients: Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and McDonald’s Omega (⍵). Then, we examined the areas and sub-areas using frequency analysis for an overview of the data. The most important findings were reached with the ANOVA for repeated measures, applied to the data collected with the first questionnaire, and the multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), applied to the data collected with the second questionnaire. The analyses were aimed at examining the differences among the areas to emphasize potential statistically significant differences among participants considering the demographic and professional characteristics listed in Table 2. Additionally, for the first questionnaire, we completed a cluster analysis to identify groups of teachers relatively homogeneous within themselves and heterogeneous between themselves, based on their answers to the areas and sub-areas of the questionnaire.

5.1 First questionnaire: teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of self- and peer-assessment

5.1.1 Quantitative findings

The first questionnaire provided data focused on teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment. After experimenting with both self- and peer-assessment, teachers were asked about the potential development of a series of six skills linked to cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective areas, indicated in Table 1. We focused our attention mainly on the research questions named RQ1a, RQ1b and RQ1c. The frequency distribution and the ANOVA for repeated measures allowed us to point out the teachers’ ideas about the potential effectiveness of formative assessment.

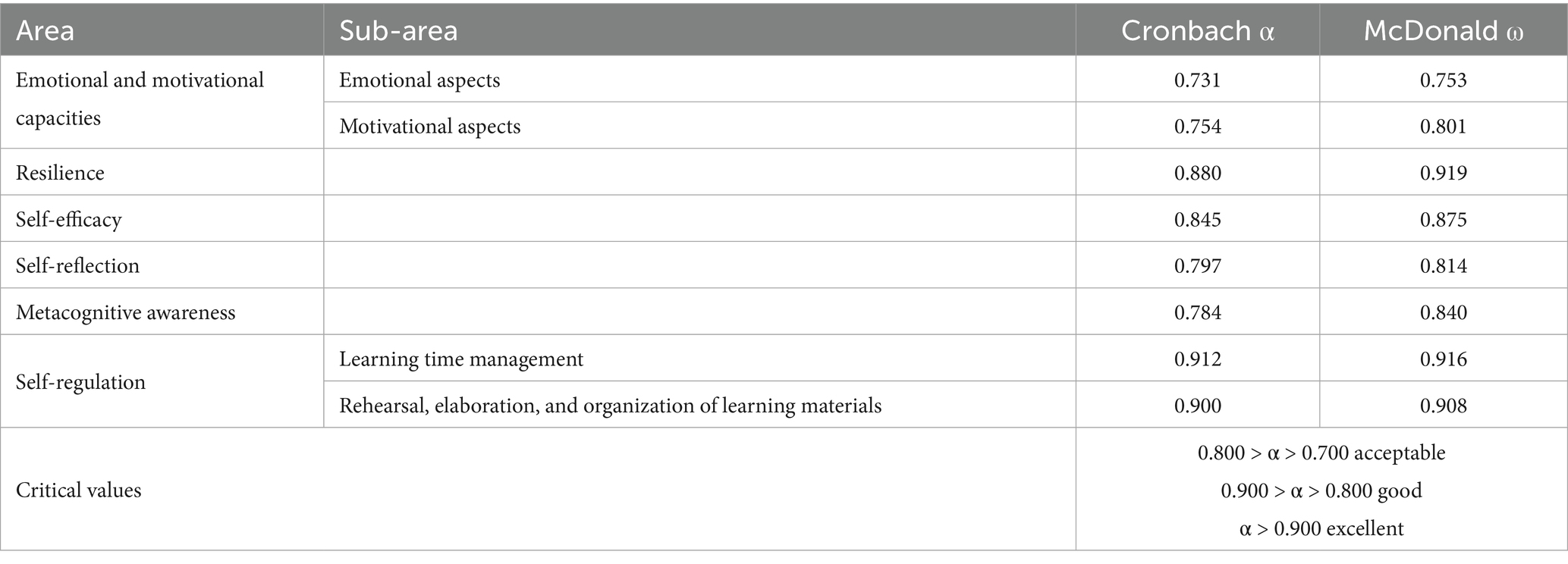

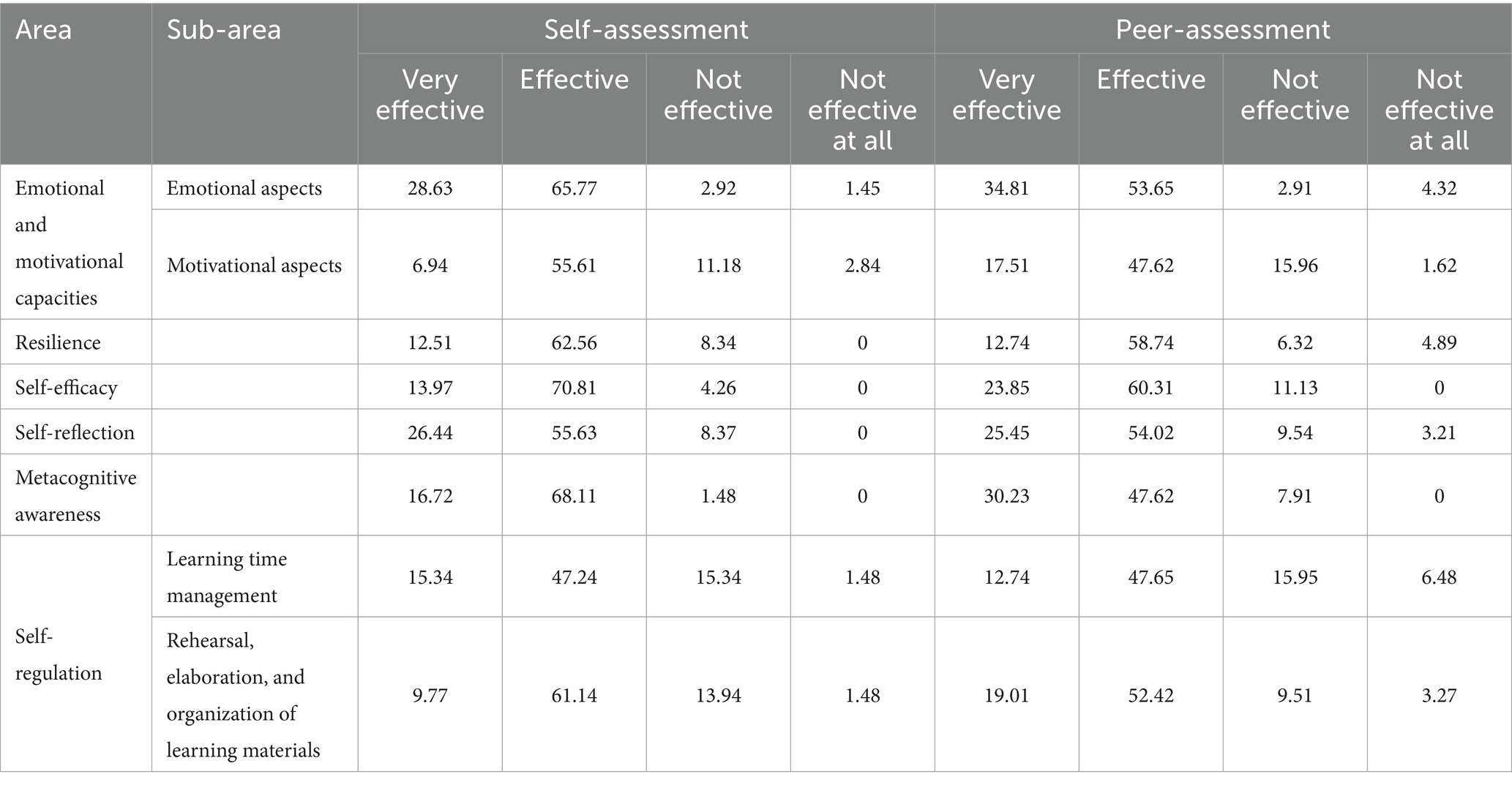

First, we examined the instrument reliability and frequency distribution, as shown in Tables 4 and 5. In particular, Table 5 reports the percentages related to positive (‘very effective’ and ‘effective’) and negative answers (‘not effective’ and ‘not effective at all’). We did not indicate the middle point because it represents a neutral answer (neither agree nor disagree). The reliability reveals a good level of instrument consistency. The frequencies were analyzed in all areas and sub-areas to have an overview of answer distribution. Generally, all areas and sub-areas report positive percentages after both self- and peer-assessment. Specifically, teachers rated self-assessment as ‘Effective’ for emotional aspects, resilience, self-efficacy, metacognitive awareness, and self-regulation for rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials. Similarly, teachers rated peer-assessment as ‘Very effective’ for emotional and motivational aspects, self-efficacy, self-reflection, metacognitive awareness, and self-regulation for rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials. Negative scores are located mainly in the areas related to self-regulation for learning time management.

Table 4. First questionnaire on teacher perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies: reliability coefficients.

Table 5. First questionnaire on teacher perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies: frequency distribution.

Teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of self- and peer-assessment are better revealed by separating the two formative assessment strategies. The analysis showed just one difference between self- and peer-assessment, found in the area related to metacognitive awareness. In this case, teachers considered self-assessment more effective than peer-assessment (MD = 0.414 p < 0.043). In general, teachers indicated an overall appreciation for both formative assessment strategies. When examining the data further, we found that female teachers in particular valued the peer-assessment strategy when compared to their male colleagues (MD = 0.895 p < 0.005). Specifically, female teachers perceived the effectiveness of peer-assessment for the following areas: motivational aspects (MD = 1.093 p < 0.011); self-efficacy (MD = 1.093 p < 0.002); metacognitive awareness (MD = 1.338 p < 0.000); self-regulation in learning time management (MD = 1.167 p < 0.017); self-regulation in rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials (MD = 1.025 p < 0.020). Notably, male teachers preferred the self-assessment strategy (MD = 0.567 p < 0.049), precisely for metacognitive awareness (MD = 1.083 p < 0.004).

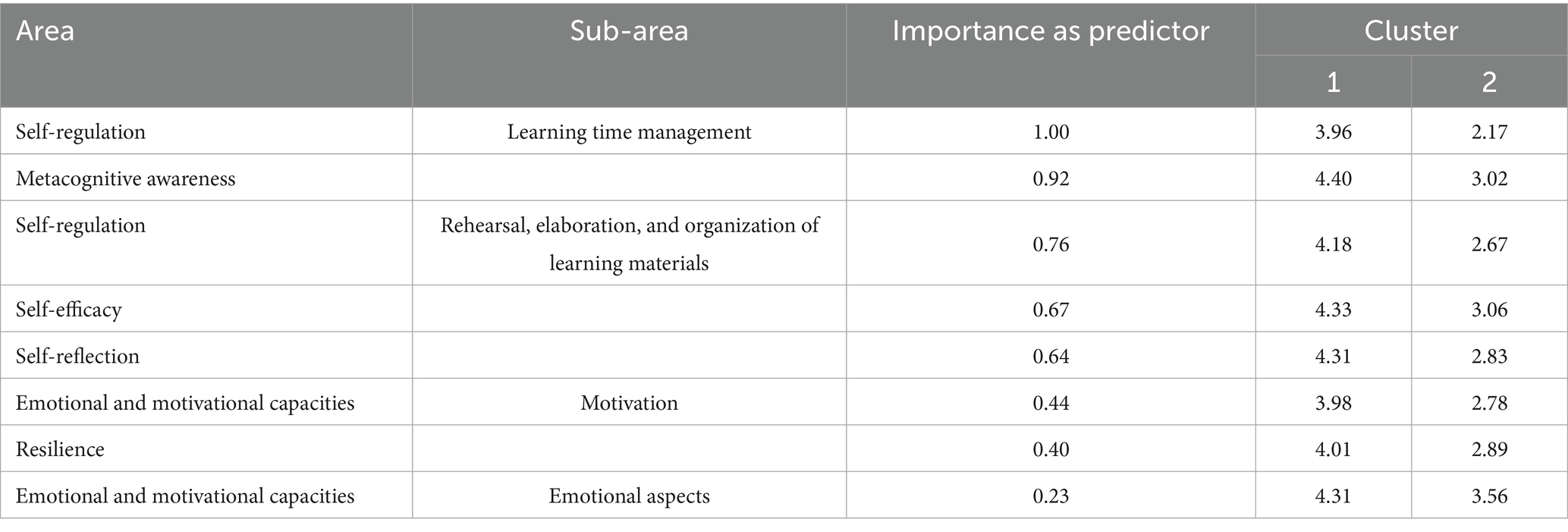

The two-step cluster analysis allowed us to identify homogeneous groups among the participants and within the self- and peer-assessment strategies, and to focus on each area/sub-area. This analysis did not show clusters for the self-assessment strategy but it revealed two clusters for peer-assessment. Table 6 presents details of the clusters. Cluster 1 includes 18 teachers (69.23%) whilst cluster 2 includes 8 teachers (30.77%). Participants included in cluster 1 represent a homogenous group of teachers who perceived peer-assessment as an effective activity to improve self-regulation in learning time management, metacognitive awareness, self-regulation in rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials, self-efficacy, and self-reflection. This cluster is composed mainly of female teachers (χ2 = 12.353 p < 0.000).

5.1.2 Qualitative findings

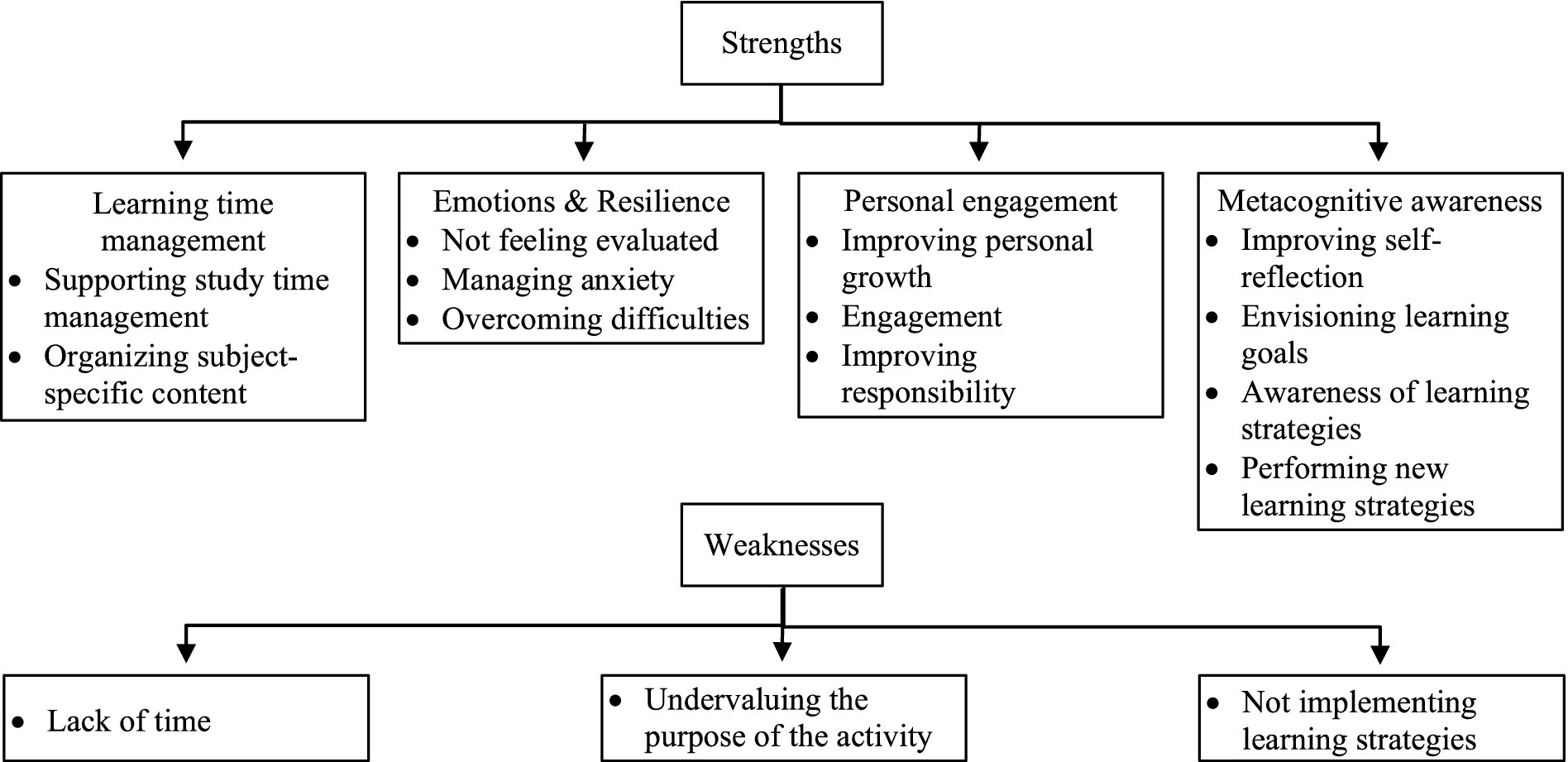

The qualitative data analysis further revealed teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of self- and peer-assessment in improving students’ learning strategies to complete the analysis of research question, called RQ1. These findings were divided into two main categories, named ‘Strengths’ and ‘Weaknesses.’ The first category, ‘Strengths’ underlines the positive elements, while ‘Weaknesses’ reveals both areas of critique and teachers’ educational needs regarding formative assessment activities. Each category is composed of different codes, as shown in Figure 2.

The category ‘Strengths’ is split into 4 sub-categories. The first sub-category is called ‘Learning time management’ because it includes 2 codes related to students’ capacity to organize study time. Specifically, the code ‘Organizing subject-specific content’ describes how formative assessment supported students capacity to effectively organize large quantities of information and content for learning. One teacher affirmed: ‘The non-graded activities, as formative assessment, allowed the students themselves to organize the topics, to be well-prepared’. Self- and peer-assessment also empowered the students’ ability to plan their schedules and managing their study time in a more productive way, as shown by the code ‘Supporting study time management’. One teacher stated: ‘I think that the self-assessment activity was useful in helping the students manage their time better’.

The second sub-category is ‘Emotions & resilience’. Teachers perceived that formative assessment activities were able to affect the emotional aspects of learning and support students in facing potential difficulties. For example, regarding the code ‘managing anxiety’, a teacher affirmed: ‘Students were more aware of what to do to study and they were able to manage their anxiety’. Similarly, the code ‘Not feeling evaluated’ shows how teachers perceived that their students felt comfortable and not judged during the formative assessment activities. A teacher said: ‘I noticed an interesting aspect for me. When I introduced the project and summarized the tools and purposes, students were immediately involved because I was involved in these activities’. Ultimately, the code ‘Overcoming difficulties’ proves how teachers perceived that formative assessment can support students in dealing with potential difficulties they may encounter during their own learning paths. A teacher stated: ‘These activities made the students more aware of their own learning processes and gave them the tools to overcome any difficulties’.

The third sub-category is named ‘Personal engagement’ because it involves teachers’ perceptions of students’ personal development through formative assessment. The codes called ‘Improving own responsibility’ and ‘Engagement’ focus on the role of formative assessment in enhancing students’ individual responsibility when it comes to organizing and facing learning tasks. Students were recognized as being more active during learning activities, with their personal development supported by formative assessment, as the code ‘Improving personal growth’ shows. One teacher stated: ‘Self-assessment is a powerful tool for student growth’.

The last sub-category, ‘Metacognitive awareness’, contains the most important codes. The first, ‘Improving self-reflection,’ shows teachers’ perceptions of the role played by formative assessment in supporting students’ reflection on their own learning process. One teacher declared: ‘The students were able to have time to reflect on their learning strategies.’ Similarly, the code ‘Envisioning own learning goals’ reveals how teachers felt that formative assessment activities gave the students the opportunity to better visualize and understand their learning objectives. Teachers observed that their students became more aware of their own learning strategies. The code ‘Awareness of learning strategies’ was stated by the majority of teachers and it represents how formative assessment activities supported students in developing their metacognitive capacities. A teacher said: ‘Formative assessment makes students more aware of their own learning process’. Additionally, teachers described how self- and peer-assessment helped their students with new learning strategies to improve their achievement, as underlined by the code ‘Performing new learning strategies’.

The ‘Weaknesses’ category includes three elements. These codes describe the critiques identified by teachers involved in the CPD. The code named ‘Not implementing learning strategies’ indicates that some teachers noticed that some students struggled to modify their learning strategies. Teachers noted that while formative assessment activities revealed to some students that their study methods were not particularly effective, not all of them were able to either change or activate new strategies. As one teacher stated: ‘Students reflected on their learning strategies and some of them realized that these strategies were not suitable to effectively elaborate the content to be studied, but they did not find any new learning solutions’. The code named ‘Lack of time’ indicates an organizational limitation. Teachers affirmed that they would need more time to effectively apply a formative assessment strategy and support students’ learning processes. The last code, called ‘Undervaluing the purpose of the activity’, underscores how some students considered the formative assessment just as a minor activity and quite unrelated to everyday learning practices.

5.2 Second questionnaire: teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of CDP program

5.2.1 Quantitative findings

The second questionnaire was dedicated to analyze the research question named RQ2. Especially, the quantitative data were useful to understand the potential strengths of a CPD based on the action research framework (RQ2a).

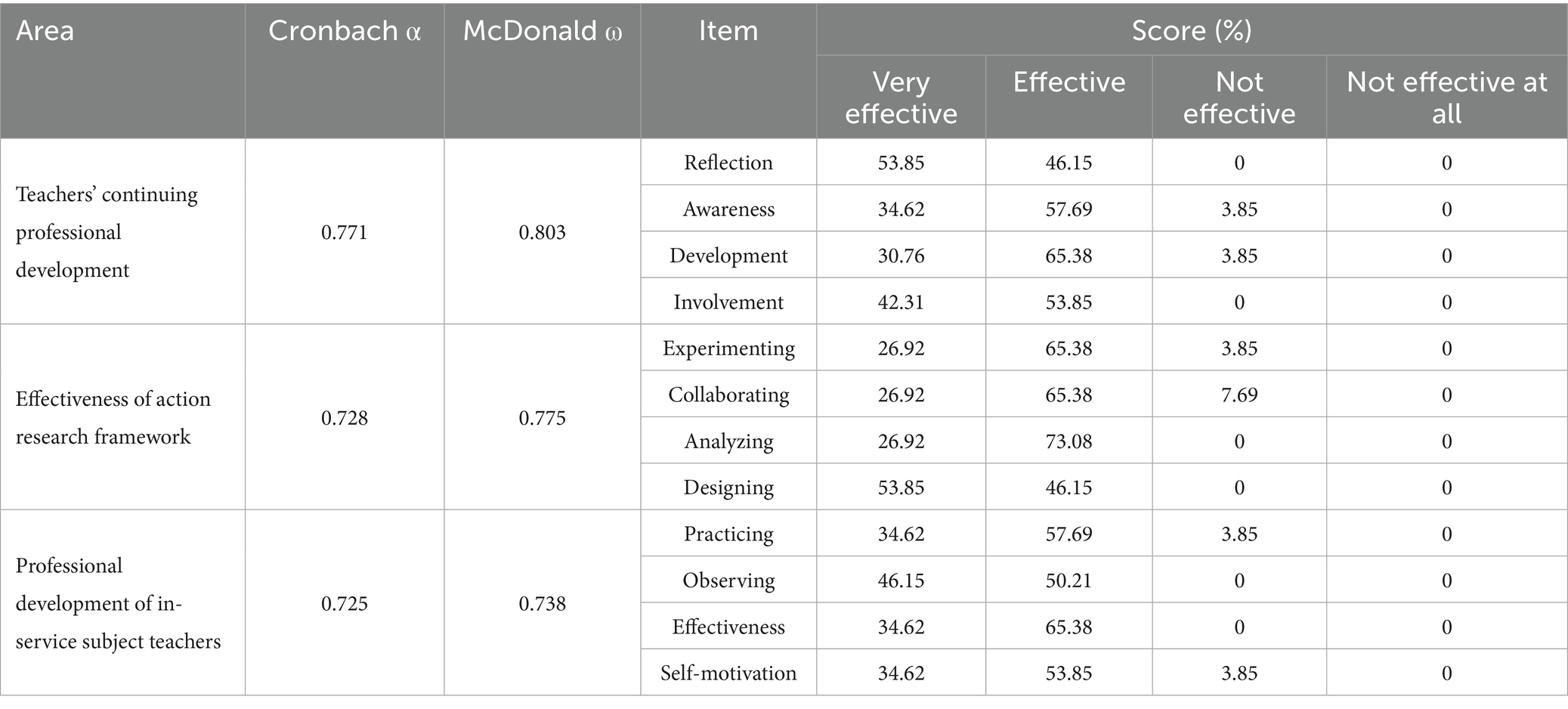

Table 7 shows the second questionnaire’s reliability and frequency distribution. As with the first questionnaire, the reliability levels indicate good instrument consistency. We specified the frequencies for all items because it was interesting to compare the teachers’ perceptions across all areas. Generally, teachers rated all areas very highly, appreciating the overall quality of CPD program (M = 4.34 SD = 0.47), the effectiveness of action research framework (M = 4.26 SD = 0.45), and the specific aspects of CPD for subject teachers (M = 4.32 SD = 0.44). The percentage distribution shows high scores for all items, with detailed MANOVA analysis revealing differences within each area. For example, in the area dedicated to the quality of CPD program the first item focused on teachers’ opportunity to reflect on assessment activity preparation and design during the CPD. This item was rated higher than the third item (MD = 0.271 p < 0.032) concerning teachers’ increased professional growth. Similarly, the first item was rated highly compared to the second item (MD = 0.208 p < 0.049) that was focused on the awareness of assessment styles.

In the area on the effectiveness of an action research framework for CPD, the fourth item focused on the capacity of the framework to involve teachers in designing new assessment strategies. This item was particularly appreciated by teachers compared to: the first item (MD = 0.436 p < 0.004) that was focused on implementing formative assessment strategies in everyday classroom activities; the second item, focused on the opportunity to cooperate with other colleagues (MD = 0.385 p < 0.022); the third item, aimed at analyzing the details of the assessment strategies (MD = 0.231 p < 0.031). In the section addressing specific aspects of CPD for subject teachers, the most valued item concerned the opportunity to observe students’ learning in a specific subject through formative assessment.

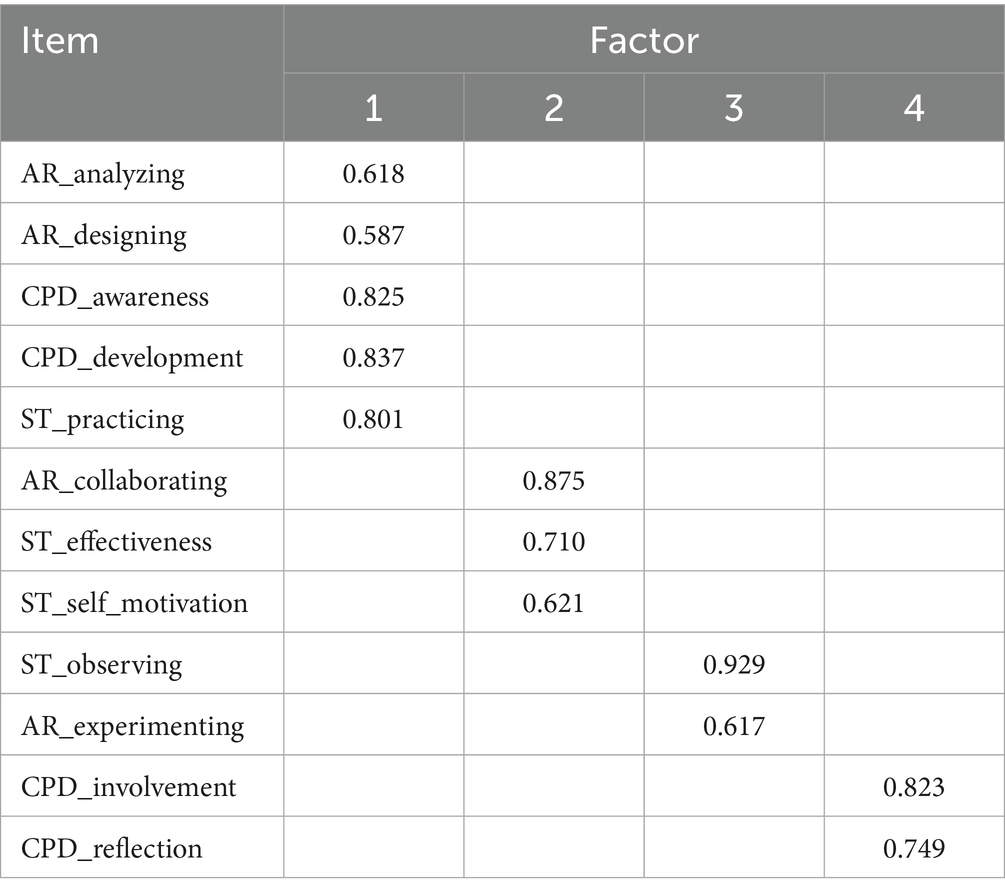

We decided to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) because we wanted to check the presence of latent factors that crossed and overlapped the three areas. The EFA was completed with varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization, using principal components extraction to highlight factors with eigenvalues > 1. The results indicate that the sample was limited since the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test was 0.602. Naseer et al. (2019) defined this level as ‘mediocre’ whilst Hair et al. (2019) and Field (2005) indicated this level as ‘reasonable’. In any case, we are aware that the number of participants involved in this study (26) is quite low. The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity revealed a p-value of < 0.000 (χ2 = 160.711; df = 66). The EFA underscored four factors (see Table 8). Factors 1 and 2 represent the main factors, since they explain the 41.27 and 17.87% of variance, respectively. The remaining two factors explain the 9.78 and 8.57% of variance. Factor 1 crosses all three areas since it is composed of five items, two from the CPD effectiveness area, two from the effectiveness of action research area, and one from the professional development of in-service subject teachers area. By focusing on the Factor 1 items, we can observe that Factor 1 summarizes teachers’ perceptions of the CPD as a catalyst for developing a higher level of assessment strategy awareness. Teachers could develop their own professional assessment competences through the action research framework, by designing and analyzing the assessment activities, and by specifically practicing them in their own subjects. Factor 2 includes the opportunity to cooperate with other colleagues, increase motivation, and experiment with the effectiveness of new assessment strategies.

5.2.2 Qualitative findings

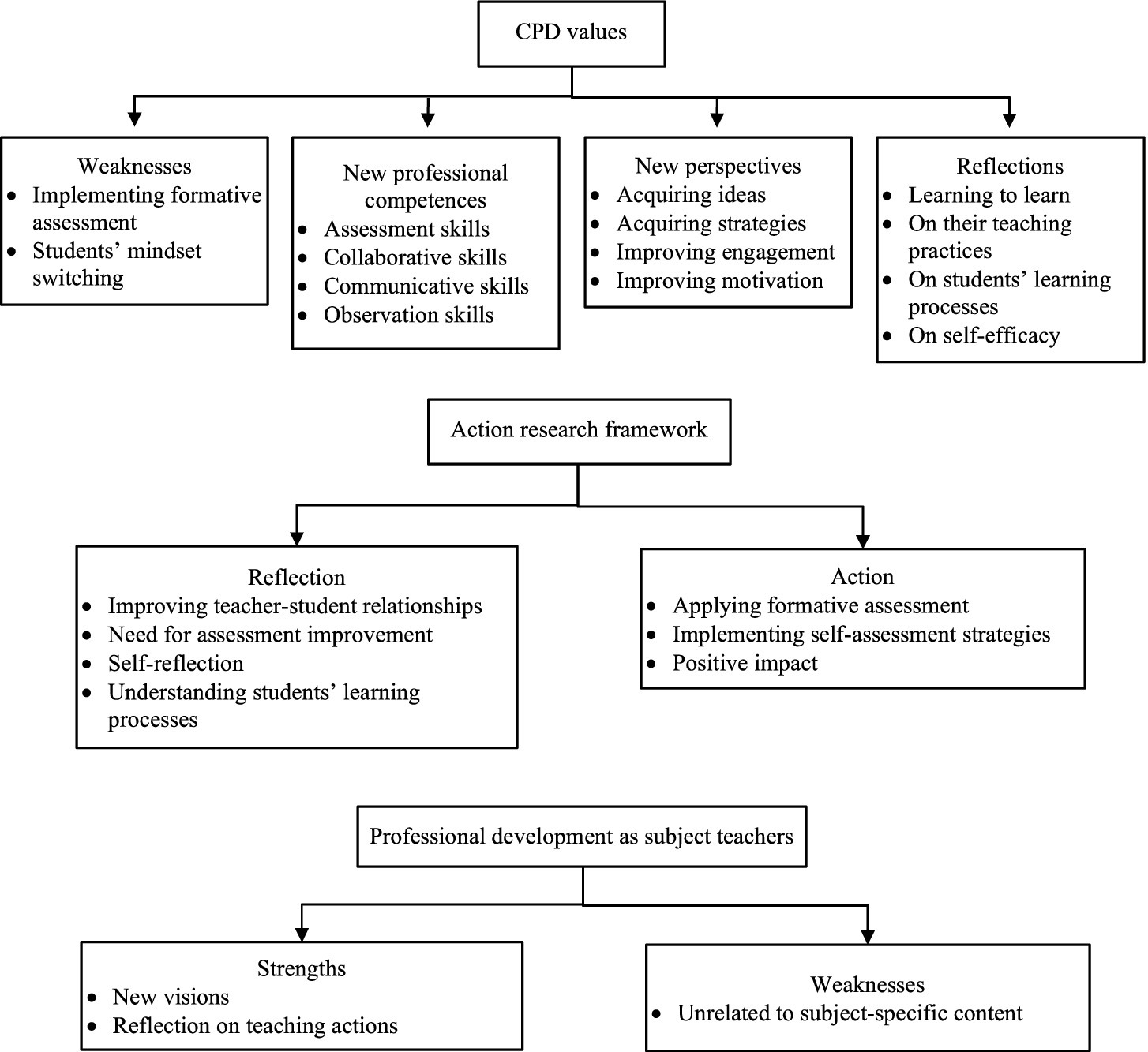

The qualitative analysis highlighted teachers’ valuable observations about the role of CPD in developing their competence in formative assessment strategies. The three questions on the second questionnaire focused on the value of continuing professional development, the effectiveness of the action research framework, and their professional development as in-service subject teachers. Specifically, these qualitative data were particularly useful to answer the RQ2b.

Figure 3 shows the main categories and codes that emerged during the analysis of responses to these three questions. Under the ‘CPD values’ area, four categories emerged, including: ‘weaknesses’, ‘new professional competences’, ‘new perspectives’, and ‘reflections’. Regarding the ‘weaknesses’, teachers emphasized two codes linked to the difficulties they encountered during the CPD program. First of all, teachers expressed difficulty transforming theoretical insights about formative assessment into practical teaching practices. The code ‘Implementing formative assessment’ represents this difficulty, illustrated by one participant: “I encountered a significant difficulty in transforming theory into practice, especially in designing the tests and adapting them for my classes.” The code named ‘Students’ mindset switching’ represents the difficulty in changing students’ beliefs regarding assessment. Students are used to assessment solely as a summative practice. So teachers found it difficult to modify these rooted opinions and give a different assessment perspective.

The second category is called ‘New professional competences’ and refers to the new skills acquired by the participants during the CPD program, as expressed by the codes ‘Collaborative skills’, ‘Communicative skills’, ‘Observation skills’ and ‘Assessment skills’. Regarding this last code a teacher affirmed: “This program reinforced my awareness of the importance of a student-centered approach, based on continuous and constructive feedback.”

The category named ‘New perspectives’ represents the new standpoints developed by the teachers during the CPD. In particular, teachers declared to have acquired ‘new ideas’ and ‘new strategies’ about assessment that can be applied in everyday classroom activities. The codes ‘Improving engagement’ and ‘Improving motivation’ show the high level of involvement felt by the participants during the CPD.

The last category, ‘Reflection’, reveals that the CPD program offered participants many opportunities to reflect on their own actions. The codes ‘Learning to learn’ and ‘On self-efficacy’ indicate how much participants reflected on the importance of developing, as in-service teachers, new teaching and assessment strategies. In particular, the code ‘On self-efficacy’ revealed that teachers were able to analyze their own teaching practices, and focus on the effectiveness of their pedagogical actions. The code ‘On their teaching practices’ specifies this impact of reflection on their teaching practices. On this point, a participant stated: “The design phase of the assessment activity was crucial. When I tried to design a concrete assessment activity, suitable for my students, I needed to completely rethink and revise my usual teaching strategies. Additionally, when I asked the students to make some comments about the activity, their answers were surprising. They offered me new perspectives about the effectiveness of my assessment strategies.” Regarding the code ‘on students’ learning processes’, another teacher said: “I developed new instruments and strategies to observe students’ learning processes more deeply. I could also value their changes and I could actively involve them in building their own learning paths.”

Concerning the action research framework, we identified two categories: ‘Reflection’ and ‘Action’. These categories indicate how the action research framework involved teachers, offered them several opportunities to reflect and, consequently, supported them in changing/modifying their teaching approaches. Specifically, the category named ‘Reflection’ indicates how teachers could act as reflective practitioners (Schön, 1984). This category is expressed by the codes: ‘Improving teacher-student relationships’, ‘Need for assessment improvement’ and ‘Understanding students’ learning processes’. The action research framework allowed teachers to self-reflect about how teaching-learning activities impact the relationships among students and teachers, as pointed out by a participant: “I was able to reflect thoroughly and deeply understand the interactive dynamics.” The category ‘Action’ represents a consequence of reflection. Teachers expressed how reflection led them to design several concrete steps to modify and improve their assessment procedures, as indicated by the codes: ‘Applying formative assessment’ and ‘Implementing self-assessment strategies’. Finally, the code ‘Positive impact’ indicates that the action research framework positively affected the teachers’ approaches to implementing assessment activities.

The last question was dedicated specifically to teachers’ professional development as in-service subject teachers. As subject teachers, the participants identified both CPD strengths and weaknesses. Regarding strengths, teachers underscored the development of new points of view, as expressed in the code ‘New visions’ and their empowerment through ‘Reflection on teaching actions’. Several participants stated that the CPD enabled them to see their subject in a different light and from several perspectives. One teacher said: ‘I observed my teaching actions with new eyes, more sensitive to the rhythm and timing of the lesson’. At the same time, some teachers declared that the formative assessment strategies were quite unrelated to their subjects, as shown by the code ‘Unrelated to subject-specific content’.

6 Discussion

The data analysis and the findings suggest some important considerations about the research questions. The RQ1 was focused on teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment strategies. To measure these ideas, teachers were asked to express their opinions about the potential development of a series of skills linked to cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and affective areas after implementing self- and peer-assessment with the students. The data indicated that peer-assessment was considered particularly effective, as already stated by van Gennip et al. (2010) and Ketonen et al. (2020). Specifically, peer-assessment was perceived as an useful strategy for emotional and motivational aspects, self-efficacy, self-reflection, and self-regulation for rehearsal, elaboration, and organization of learning materials. These results confirm the studies on the efficacy of peer-assessment conducted by Son and Ha (2024) and Van Hoe et al. (2024). Teachers identified the effectiveness of self-assessment for developing metacognitive awareness, as already indicated by Kasimatis and Papageorgiou (2019), Shekh-Abed (2024).

The data analysis, both MANOVA and cluster analysis, underlined that female teachers preferred the peer-assessment activity compared to their male colleagues who, on the contrary, attributed more value to self-assessment. This is an interesting result because this gender difference has not been reported by others. Previous studies have underscored the different perceptions by female and male students (Guo, 2024), and Asamoah et al. (2019) emphasized gender differences among teachers, but only in relation to levels of formative assessment knowledge. In any case, due to the limited number of participants in our study, this finding should be confirmed in further studies with a larger number of teachers.

It is important to highlight and discuss the findings raised from the qualitative analysis. First of all, teachers emphasized lack of time as an important limitation of formative assessment. Parmigiani et al. (2025b) have already discussed this weakness related to the practical use of formative assessment. Many teachers complain that an effective formative assessment activity needs time, and that they experience difficulty combining formative assessment with other instructional activities. Teachers have also indicated some crucial strengths of formative assessment. In particular, they stressed the importance of formative assessment in supporting students’ growth in: effectively managing their learning and study time; facing their anxiety; improving their resilience levels, personal engagement and metacognitive awareness. Through the qualitative data, teachers further expressed how formative assessment can support the development of students’ affective, behavioral, cognitive and metacognitive skills, as indicated by Andrade and Brookhart (2020) and Li and Yongqi Gu (2024).

Concerning the RQ2, teachers were asked to evaluate the quality of the CPD program, the effectiveness of the action research framework, and the professional development of subject teachers regarding their pedagogical content knowledge. Teachers declared that the CPD program supported them in reflecting on how they prepare and design their assessment activities. These results confirm the studies conducted by Kemmis et al. (2014) and La Velle and Newman (2022). Similarly, teachers affirmed that the action research framework increased their capacities in designing new assessment strategies. The keyword is ‘designing’. Teachers appreciated the CPD program because they could implement the formative assessment strategies they designed, thereby improving their own skills in designing lectures based on formative assessment (Abakah, 2023). As subject teachers, participants highlighted the benefits of observing students while they are learning a specific subject through formative assessment. Teachers could link specific features of their subject content with methodological aspects of their instruction, consequently increasing their pedagogical content knowledge (Nkundabakura et al., 2024). Through the CPD on assessment, teachers gained awareness of formative assessment’s potential to support students’ learning processes, and teachers felt capable of integrating formative assessment within subject-specific activities more effectively, as indicated by Estaji (2024) and Guerrero-Romera and Perez-Ortiz (2022). Additionally, teachers valued opportunities to cooperate with other colleagues through the CPD. These professional and pedagogical connections enhanced their motivation to experiment with new teaching and assessment practices (Holmqvist and Lelinge, 2021).

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the low number of participants reduces the generalisability of the findings. Second, the focus of the study was primarily on teachers’ perceptions. So, additional instruments should be applied to assess the actual effects on teaching effectiveness. Finally, the sampling procedure was carried out on voluntary basis. Consequently, we must consider that self-selection might introduce biases.

7 Conclusions and implications for policy and practice

In conclusion, we propose some considerations and implications for policy and practice. First of all, it is important to highlight our observations on the characteristics of professional development programs for in-service teachers. Following our findings, the CPD programs should support teachers’ skills in designing and implementing new teaching strategies (Altun and Gök, 2010). Through an educational design implementation, teachers can imagine new learning environments and become designers of new learning experiences (Bosch et al., 2025). Together with design implementation, a CPD program for in-service teachers needs to be based on the opportunity to put into practice the design and experiment new teaching strategies (João et al., 2023). The action research framework proved to be the right context for in-service teachers to support their professional growth (Francisco et al., 2024). Donath et al. (2023) emphasized that the activeness of teaching/learning processes allows teachers to apply newly learned methods with their pupils during CPD. Ultimately, a CPD program should also provide opportunities to reflect on teachers’ practices in a collaborative context where teachers can share potential solutions and doubts with their colleagues (Girardet, 2018).

In particular, these characteristics are remarkably effective for in-service subject teachers because they can focus on the benefits for teaching their own subject and need good practical applications for their classrooms (Ahraz, 2025). In this way, teachers can combine the subject-specific aspects of their instruction with the pedagogical content knowledge that can improve their practice (Teslo et al., 2023).

From a critical point of view, we need to underline also some negative aspects related to the CPD organization, such as: high workload, financial and resource constraints, potential lack of motivation, as indicated by Asmare (2025). Our final remark reiterates the importance of the topic central to this CPD program: formative assessment. Our findings indicate that formative assessment is a meaningful CPD focus for in-service subject teachers because it addresses several challenges found in current learning contexts, as indicated by Vattøy and Gamlem (2024) and Levy-Feldman and Fresko (2025). Further studies should be focused on important topics, such as: the analysis of several formative assessment strategies to highlight the respective strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, it would be important to investigate the differences in applying formative assessment strategies within several subjects or with different participants’ typologies, mainly primary and secondaty students or focusing on potential differences, like students’ gender, age, etc.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Comitato Etico per la Ricerca di Ateneo (CERA) of the University of Genoa (Italy). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. EN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. EM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SR: Writing – review & editing. MI: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1695771/full#supplementary-material

References

Abakah, E. (2023). Teacher learning from continuing professional development (CPD) participation: a sociocultural perspective. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 4:100242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100242

Abakah, E., Widin, J., and Ameyaw, E. K. (2022). Continuing professional development (CPD) practices among basic school teachers in the central region of Ghana. SAGE Open 12:21582440221094597. doi: 10.1177/21582440221094597

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educ. Action Res. 1, 7–24. doi: 10.1080/0965079930010102

Ahmed, S. K. (2024). How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: a simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 12:100662. doi: 10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662

Ahraz, A. O. (2025). Continuing professional development of in-service physical education teachers: a scoping review, 2002–2021. Quest 77, 518–533. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2025.2513355

Al-Eisawi, D. (2022). A design framework for novice using grounded theory methodology and coding in qualitative research: organisational absorptive capacity and knowledge management. Int J Qual Methods 21:16094069221113551. doi: 10.1177/16094069221113551

Al-Mamari, A., Al-Mekhlafi, A. M., Al-Seyabi, F., and Omara, E. (2022). Exploring the practice of action research among English language teachers in Omani public schools and factors affecting its implementation. World J. Engl. Lang. 12:370. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n5p370

Almonacid-Fierro, A., Sepúlveda-Vallejos, S., Valdebenito, K., Montoya-Grisales, N., and Aguilar-Valdés, M. (2023). Analysis of pedagogical content knowledge in science teacher education: a systematic review 2011-2021. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 9, 525–534. doi: 10.12973/ijem.9.3.525

Almunawaroh, N. F., and Steklács, J. (2025). The interplay of secondary EFL teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and pedagogical content knowledge with their instructional material use approach orientation. Heliyon 11:e42065. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42065

Altun, A., and Gök, B. (2010). Determining in-service training programs’ characteristics given to teachers by conjoint analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2, 1709–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.970

Andrade, H. L. (2019). A critical review of research on student self-assessment. Front. Educ. 4:87. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

Andrade, H. L., and Brookhart, S. M. (2020). Classroom assessment as the co-regulation of learning. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 27, 350–372. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1571992

Asamoah, D., Songnalle, S., Sundeme, B., and Derkye, C. (2019). Gender difference in formative assessment knowledge of senior high school teachers in the upper west region of Ghana. J. Educ. Pract. 10, 54–58. doi: 10.7176/jep/10-6-08

Asmare, M. A. (2025). Teachers’ experiences of continuous professional development: implications for policy and practice. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 11:101514. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101514

Aussems, K., Isarin, J., Niemeijer, A., and Dedding, C. (2024). Working together as scientific and experiential experts: how do current ethical PAR-principles work in a research team with young adults with developmental language disorder? Educ. Action Res. 32, 311–326. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2022.2130386

Behzadi, A., Golshan, M., and Sayadian, S. (2019). Validating a continuing professional development scale among Iranian EFL teachers. J. Modern Res. English Lang. Stud. 6:1358. doi: 10.30479/jmrels.2019.10848.1358

Bergmark, U. (2023). Teachers’ professional learning when building a research-based education: context-specific, collaborative and teacher-driven professional development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 49, 210–224. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1827011

Birenbaum, M., and Rosenau, S. (2006). Assessment preferences, learning orientations, and learning strategies of pre-service and in-service teachers. J. Educ. Teach. 32, 213–225. doi: 10.1080/02607470600655300

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2003). ‘In praise of educational research’: formative assessment. Br. Educ. Res. J. 29, 623–637. doi: 10.1080/0141192032000133721

Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., and Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: competence viewed as a continuum. Z. Psychol. 223, 3–13. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

Bloom, B. S., Hastings, T., and Madaus, G. F. (1971). Handbook on formative and summative evaluation of student learning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bosch, N., Härkki, T., and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2025). Teachers as reflective learning experience designers: bringing design thinking into school-based design and maker education. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 43:100695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcci.2024.100695

Cain, T., and Milovic, S. (2010). Action research as a tool of professional development of advisers and teachers in Croatia. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 33, 19–30. doi: 10.1080/02619760903457768

Carney, E. A., Zhang, X., Charsha, A., Taylor, J. N., and Hoshaw, J. P. (2022). Formative assessment helps students learn over time: why aren’t we paying more attention to it? Intersect. J. Intersect. Assess. Learn. 4:38391. doi: 10.61669/001c.38391

Chou, C. (2010). Investigating the effects of incorporating collaborative action research into an in-service teacher training program. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2, 2728–2734. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.404

Cierpiałowska, T. (2023). Action research as a path to change in the teaching/learning process. Multidiscip. J. Sch. Educ. 12, 257–275. doi: 10.35765/mjse.2023.1224.13

Clipa, O., Duca, D. S., and Padurariu, G. (2021). Test anxiety and student resilience in the context of school assessment. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidim. 13:397. doi: 10.18662/rrem/13.1Sup1/397

Coryn, C. L. S., Spybrook, J. K., Evergreen, S. D. H., and Blinkiewicz, M. (2009). Development and evaluation of the social-emotional learning scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 27, 283–295. doi: 10.1177/0734282908328619

Crawford, R. (2022). Action research as evidence-based practice: enhancing explicit teaching and learning through critical reflection and collegial peer observation. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 47:6065. doi: 10.14221/1835-517X.6065

Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. P., Gutmann, M., and Hanson, W. (2003). “Advanced mixed methods research designs” in Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 209–240.

Dadds, M. (1997). Continuing professional development: nurturing the expert within. J. In-Serv. Educ. 23, 31–38. doi: 10.1080/13674589700200007

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., and Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

De Araujo, J., Gomes, C. M. A., and Jelihovschi, E. G. (2023). The factor structure of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ): new methodological approaches and evidence. Psicol. Reflexão e Crítica 36:38. doi: 10.1186/s41155-023-00280-0

De Neve, D., Leroy, A., Struyven, K., and Smits, T. (2022). Supporting formative assessment in the second language classroom: an action research study in secondary education. Educ. Action Res. 30, 828–849. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1828120

Depaepe, F., Noens, P., Kelchtermans, G., and Simons, M. (2013). Do teachers have a relationship with their subject? A review of the literature on the teacher-subject matter relation. Teor. Educ. 25, 109–124. doi: 10.14201/11153

Dever, D. A., Sonnenfeld, N. A., Wiedbusch, M. D., Schmorrow, S. G., Amon, M. J., and Azevedo, R. (2023). A complex systems approach to analyzing pedagogical agents’ scaffolding of self-regulated learning within an intelligent tutoring system. Metacogn. Learn. 18, 659–691. doi: 10.1007/s11409-023-09346-x

Donath, J. L., Lüke, T., Graf, E., Tran, U. S., and Götz, T. (2023). Does professional development effectively support the implementation of inclusive education? A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 35, 1–28. doi: 10.1007/s10648-023-09752-2

Dulo, A. A. (2022). In-service teachers’ professional development and instructional quality in secondary schools in Gedeo zone, Ethiopia. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 5:100252. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100252

Estaji, M. (2024). Perceived need for a teacher education course on assessment literacy development: insights from EAP instructors. Asian-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 9:50. doi: 10.1186/s40862-024-00272-2

Etkina, E., Karelina, A., Murthy, S., and Ruibal-Villasenor, M. (2009). Using action research to improve learning and formative assessment to conduct research. Phys. Rev. Special Top. Phys. Educ. Res. 5:010109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.5.010109

European Commission. (2007). Schools for the 21st century. Commission staff working paper. European Commission.

European CommissionLooney, J., and Kelly, G. (2023). Assessing learners’ competences – Policies and practices to support successful and inclusive education. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Francisco, S., Forssten Seiser, A., and Olin Almqvist, A. (2024). Action research as professional learning in and through practice. Prof. Dev. Educ. 50, 501–518. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2024.2338445

Fukaya, T., Nakamura, D., Kitayama, Y., and Nakagoshi, T. (2025). A systematic review and meta-analysis of research on mathematics and science pedagogical content knowledge: exploring its associations with teacher and student variables. Teach. Teach. Educ. 155:104881. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104881

Galway, L., Bell, N., Sae, A. S., Hagopian, A., Burnham, G., Flaxman, A., et al. (2012). A two-stage cluster sampling method using gridded population data, a GIS, and Google EarthTM imagery in a population-based mortality survey in Iraq. Int. J. Health Geogr. 11:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-11-12

Girardet, C. (2018). Why do some teachers change and others don’t? A review of studies about factors influencing in-service and pre-service teachers’ change in classroom management. Rev. Educ. 6, 3–36. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3104

González-Berruga, M. Á. (2025). Measuring educational quality in the classroom: validation of the effective teaching in secondary education questionnaire. Int. J. Didact. Stud. 1:1584. doi: 10.33902/IJODS.202531584

Guerrero-Romera, C., and Perez-Ortiz, A. L. (2022). The training needs of in-service teachers for the teaching of historical thinking skills in compulsory secondary education and the baccalaureate level. Front. Educ. 7:934646. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.934646

Guo, W. (2024). Gender differences in teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning. Educ. Stud. 50, 341–361. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2021.1943648

Hair, J. F., Gabriel, L. D. S., Da Silva, D., and Braga Junior, S. (2019). Development and validation of attitudes measurement scales: fundamental and practical aspects. RAUSP Manag. J. 54, 490–507. doi: 10.1108/RAUSP-05-2019-0098

Hanfstingl, B., and Pflaum, M. (2022). Continuing professional development designed as second-order action research: outcomes and lessons learned. Educ. Action Res. 30, 223–242. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1850496

Havia, J., Lutovac, S., Komulainen, T., and Kaasila, R. (2023). Preservice subject teachers’ lack of interest in their minor subject: is it a problem? Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 21, 923–941. doi: 10.1007/s10763-022-10277-3

Holmqvist, M., and Lelinge, B. (2021). Teachers’ collaborative professional development for inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 819–833. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1842974

Jenßen, L., Eilerts, K., and Grave-Gierlinger, F. (2023). Comparison of pre- and in-service primary teachers’ dispositions towards the use of ICT. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 14857–14876. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11793-7

Jeschke, C., Kuhn, C., Heinze, A., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Saas, H., and Lindmeier, A. M. (2021). Teachers’ ability to apply their subject-specific knowledge in instructional settings: a qualitative comparative study in the subjects mathematics and economics. Front. Educ. 6:683962. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.683962

João, P., Henriques, M. H., Rodrigues, A. V., and Sá, P. (2023). In-service teacher education program through an educational design research approach in the framework of the 2030 agenda. Educ. Sci. 13:584. doi: 10.3390/educsci13060584

Johannesson, P., and Olin, A. (2024). Teachers’ action research as a case of social learning: exploring learning in between research and school practice. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 68, 735–749. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2023.2175253

Karaca, M., and Bektas, O. (2022). Self-regulation scale for science: a validity and reliability study. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Sci. 4, 236–256. doi: 10.46328/ijonses.302

Kasimatis, K., and Papageorgiou, T. (2019). Self-assessment through the metacognitive awareness process in reading comprehension. Educ. New Dev. 1, 121–125. doi: 10.36315/2019v1end026

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., and Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Singapore: Springer.

Kennedy, A. (2005). Models of continuing professional development: a framework for analysis. J. In-Serv. Educ. 31, 235–250. doi: 10.1080/13674580500200277

Kervinen, A., Portaankorva-Koivisto, P., Kesler, M., Kaasinen, A., Juuti, K., and Uitto, A. (2022). From pre- and in-service teachers’ asymmetric backgrounds to equal co-teaching: investigation of a professional learning model. Front. Educ. 7:919332. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.919332

Ketonen, L., Nieminen, P., and Hähkiöniemi, M. (2020). The development of secondary students’ feedback literacy: peer assessment as an intervention. J. Educ. Res. 113, 407–417. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2020.1835794

Kroksmark, T. (2015). Teachers’ subject competence in digital times. Educ. Inq. 6:24013. doi: 10.3402/edui.v6.24013

Kyaruzi, F., Strijbos, J.-W., Ufer, S., and Brown, G. T. L. (2019). Students’ formative assessment perceptions, feedback use and mathematics performance in secondary schools in Tanzania. Assess. Educ. 26, 278–302. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1593103

La Velle, L. (2024). Teacher-as-researcher: a foundational principle for teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 50, 367–370. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2024.2361498

La Velle, L., and Newman, S. (2022). “Becoming a teacher: what do teachers do?” in Learning to teaching in the secondary school: A companion to school experience. eds. S. Capel, M. Leask, S. Younie, E. Hidson, and J. Lawrence (London: Routledge), 37–51.

Lämsä, J., De Mooij, S., Aksela, O., Athavale, S., Bistolfi, I., Azevedo, R., et al. (2025). Measuring secondary education students’ self-regulated learning processes with digital trace data. Learn. Individ. Differ. 118:102625. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2024.102625

Leijen, Ä., Pedaste, M., and Baucal, A. (2024). A new psychometrically validated questionnaire for assessing teacher agency in eight dimensions across pre-service and in-service teachers. Front. Educ. 9:1336401. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1336401

Lereya, S. T., Humphrey, N., Patalay, P., Wolpert, M., Böhnke, J. R., Macdougall, A., et al. (2016). The student resilience survey: psychometric validation and associations with mental health. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 10:44. doi: 10.1186/s13034-016-0132-5

Leuverink, K. R. K., and Aarts, A. M. L. R. (2024). Exploring secondary education teachers’ research attitude. Educ. Stud. 50, 702–721. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2021.1982676

Levy-Feldman, I., and Fresko, B. (2025). School assessment culture and the formative assessment of teachers. Teach. Dev. 29, 947–965. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2025.2477250

Lew, M. M., and Mohsin, M. (2013). Action research project in teacher education curriculum: a tool for developing professional construct among pre-service teachers. Int. J. Learning High. Educ. 19, 13–23. doi: 10.18848/2327-7955/cgp/v19i01/48671

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues 2, 34–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Li, J., and Yongqi Gu, P. (2024). Formative assessment for self-regulated learning: evidence from a teacher continuing professional development programme. System 125:103414. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2024.103414

Ligozat, F., Amade-Escot, C., and Östman, L. (2015). Beyond subject specific approaches of teaching and learning: comparative didactics. Interchange 46, 313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10780-015-9260-8

Liu, X., and Yu, J. (2021). Relationships between learning motivations and practices as influenced by a high-stakes language test: the mechanism of washback on learning. Stud. Educ. Eval. 68:100967. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100967

Manfra, M. M. (2019). Action research and systematic, intentional change in teaching practice. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 163–196. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821132

Mapulanga, T., Ameyaw, Y., Nshogoza, G., and Bwalya, A. (2024). Integration of topic-specific pedagogical content knowledge components in secondary school science teachers’ reflections on biology lessons. Discov. Educ. 3:17. doi: 10.1007/s44217-024-00104-y

Martínez-López, Z., Nouws, S., Villar, E., Mayo, M. E., and Tinajero, C. (2023). Perceived social support and self-regulated learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 5:100291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100291

Meusen-Beekman, K. D., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., and Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2016). Effects of formative assessments to develop self-regulation among sixth grade students: results from a randomized controlled intervention. Stud. Educ. Eval. 51, 126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.10.008

Mizzi, E. (2024). Pedagogical content knowledge in school economics. Citizenship Soc. Econ. Educ. 23, 127–143. doi: 10.1177/14788047241276192

Muho, A., and Taraj, G. (2022). Impact of formative assessment practices on student motivation for learning the English language. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 10, 25–41. doi: 10.18488/61.v10i1.2842

Naseer, M., Ashfaq, M., Hassan, S., Abbas, A., Razzaq, A., Mehdi, M., et al. (2019). Critical issues at the upstream level in sustainable supply chain management of Agri-food industries: evidence from Pakistan’s citrus industry. Sustainability 11:1326. doi: 10.3390/su11051326