- 1Didactic and School Organization, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain

- 2Development and Educational Psychology, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain

This paper discusses the application of challenge-based education (CBE) in sustainability contexts, based on the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 projects. Within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 3, CBE is proposed as a way to develop transversal and sustainability skills. The study describes its implementation in open, multicultural, multilingual, and cross-subject contexts, with the participation of regional agents. It highlights the creation of collaborative communities, redefining the role of the teacher as facilitator and the thoughtful use of log books. The experience shows how to structure active learning with local solutions, offering recommendations for universities seeking a transformational educational experience committed to sustainability.

Introduction: background and rationale for the educational activity innovation

The Agenda 2030 (United Nations, 2015) sets the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a target for 2030, challenging universities to make education for sustainable development (EDS) part of their research, teaching, and administration (Weybrecht, 2017). EDS, crucial to SDG 4.7 (UNESCO, 2014), fosters skills such as critical thought and global citizenship by calling for innovative, action-oriented educational environments (UNESCO, 2017).

Spanish universities have taken on board the Agenda 2030, and the Spanish university rectors’ conference (CRUE) opted to make the SDGs one of its priorities (CRUE, 2012). The most significant, visible advances are those centered on the greening of campuses and research initiatives (Sáez de Cámara et al., 2021). Teaching practices, on the other hand, are developing more slowly (Cotton et al., 2009; Sterling and Scott, 2008; Wals, 2009) and require the implementation of cross-subject projects and measures to tackle the social-environmental issues related to degree curricula (Cruz-Iglesias et al., 2022; Rekalde-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

The configuration of the physical learning environment depends largely on the chosen teaching–learning methodology, as it must respond to its specific requirements. Thus, the physical setting is not a secondary element; it shapes participation and the types of tasks carried out in the learning process (Delbury and y Carcamo, 2020). The OECD (2013) report on innovative learning environments highlights a broad consensus that learning is situated and socially embedded. While literature often associates learning environments mainly with ICT-based programs (Zitter and Hoeve, 2012), the OECD conceptualizes them holistically as learning ecosystems that integrate both the learning processes and the environment in which they occur. In this view, context functions as an organic system essential to contemporary understandings of learning, where diverse combinations of approaches are considered the norm (Dumont et al., 2016).

This paper, therefore, sets out to describe the construction of two open, living EDS environments open to the region: Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3, in order to help the academic community in its task of designing and structuring EDS-linked teaching and learning processes.

Pedagogical framework(s), pedagogical principles, and competencies/standards underlying the educational activity

Learning environments go beyond the traditional classroom, extending into informal spaces such as outdoor training (Rekalde-Rodríguez et al., 2024) or living labs (Prestol, 2020), where knowledge flows freely. The OECD (2013) stresses that context is crucial to situated learning, seen as a dynamic, flexible ecosystem (Dumont et al., 2016). The OECD Handbook for Innovative Learning Environments (2017) proposes seven essential principles to take into account when designing innovative learning environments:

1. The learning environments recognize the learners as their core participants, encourage their active engagement, and develop in them an understanding of their own activity as learners.

2. The learning environments are founded on the social nature of learning and actively encourage well-organized cooperative learning.

3. The learning professionals within the learning environment are highly tuned to the learners’ motivations and the key role of emotions in achievement.

4. The learning environment is acutely sensitive to the individual differences among the learners in it, including their prior knowledge. It is said: “As the learning becomes more personalized, the active role of the learners themselves” (p. 26).

5. The learning environment devises programs that demand hard work and challenge all, without excessive overload. It is said: “No-one should be allowed to coast for any significant time on work that does not stretch them. By the same token, simply increasing pressure to overload does not make for deep and lasting learning” (p. 25).

6. The learning environment operates with clarity of expectations and deploys assessment strategies consistent with these expectations; there is a strong emphasis on formative feedback to support learning.

7. The learning environment emphasizes horizontal connections across disciplines, the community, and the real world. As stated: “Real-world problems do not fit neatly into subject boundaries, and tackling them makes learning more relevant” (p. 26). It also highlights that partnerships and networks will be essential in the future.

To put these seven principles into practice, the OECD (2017) proposes: (a) innovation in the core educational elements of the learning environment, i.e., students, trainers, content, and learning resources plus the dynamics that put them together; (b) turning organizations into training spaces; and (c) opening up to alliances with the community, cultural institutions, media, companies, and so on.

Furthermore, the literature points out that scientific progress often comes about in interdisciplinary settings in which the traditional borders between subjects are no longer the initial point of reference (Bernstein, 2015; Correa and Carlachiani, 2021; Evans, 2019; Morin, 2011; Tilbury, 2011).

The complex, global challenges posed by EDS can only be met through a cross-subject approach to education (Barth et al., 2023; Sabbah, 2021), implemented in contexts that represent true learning environments (Oser and Baeriswyl, 2001); stimulus-rich learning environments that encourage an active learning process (Zabalza and Zabalza, 2019). In fact, the literature warns us that skills development is not automatically guaranteed by the method used but depends on the learning environment (Gil-Molina et al., 2024; Membrillo-Hernández et al., 2019).

Innovative environments call for methodologies focused on both process and results (Márquez and Blas, 2022). Challenge-based learning (CBL), an active methodology aligned with EDS (Evans, 2019), was promoted by Apple (2008), though its academic origins date back to 2001 (Gallagher and Savage, 2023). The Enlight consortium defines it as a multidisciplinary approach in which students solve real problems by developing 21st-century skills (2025). Challenge-based education (CBE) aims to not only deepen subject matter expertise but also to develop transferable 21st-century skills, such as creativity, collaboration, and communication, and to better prepare students for challenges they are likely to encounter in their future careers (Enlight, 2025).

CBE focuses on learning by solving complex, real problems (López-Fraile et al., 2021), on the basis of experiential learning (Benítez Erice et al., 2016; Portuguez and Gomez, 2020). While similar to project based learning (PBL), it involves greater flexibility and co-creation within the community (Membrillo-Hernández et al., 2019).

Sukackè et al. (2022) consider CBE in five different dimensions: (1) the learning activities deal with real problems for which a response/solution must be found; (2) the solution type must be real and open; (3) the product—response/solution—leads to one or more specific actions; (4) the process challenges students to analyze, design, develop, and execute the best response/solution to the challenge; and (5) throughout the process, teachers play the part of coach and co-researcher. Outside professionals play an active part in students’ skills development (Agüero et al., 2019), and this multiactor collaboration (students, teachers, and outside agents) fosters integration between academia and the world of work (Yang et al., 2018), acting as a methodological bridge between these two spheres (Pinto and Soto, 2021).

The CBE process is divided into three interconnected stages: engagement, investigation, and action (Nichols et al., 2016). Each phase offers opportunities for mini-research cycles and prepares students to move on to the next phase or, if necessary, go back to a previous phase in a continuous process of documentation, reflection, participation, and collaboration.

Gallagher and Savage (2023), after reviewing a total of 100 papers using a qualitative thematic matrix, identified eight features common to CBE approaches: challenge definition, global themes, real-world challenges, collaboration, technology, flexibility, multidisciplinarity, and innovation and creativity. Van den Beemt et al. (2023) take into account these features, but incorporate dimensions and indicators to reflect the range of features to be seen in CBE implementation: vision challenge (link to real problems, global themes, and stakeholders), teaching and learning (T-shaped professionals, guided teaching, self-directed learning, summative assessment training, interdisciplinarity, collaborative learning and use of educational technology), and support (ICT infrastructures and teacher support in designing challenges, change in the teacher’s role from expert to facilitator).

The literature stresses the development of transversal skills such as teamwork, communication, leadership, and creativity based on sustainability (Kohn Rådberg et al., 2020; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2022; Portuguez and Gomez, 2020; Rodríguez-Chueca et al., 2020), and the purpose of having a social, environmental, economic, and political impact on the region through sustainable solutions (van den Beemt et al., 2023).

In short, CBE is considered a method to transform adult learning and develop 21st-century skills to meet the needs of the world of work (Leijon et al., 2022). Its features of flexibility, adaptability, and connectivity with the region and the community mean that this methodology is clearly oriented toward sustainable development (Kohn Rådberg et al., 2020; Portuguez and Gomez, 2020; Sukackè et al., 2022; van den Beemt et al., 2023). However, this calls for engagement with the bodies and stakeholders in order to ensure that the EDS is rooted in the challenges of the region.

Finally, while CBE is being implemented in higher education in different areas, good practices need to be identified and described; these are as yet lacking because of its incipient nature as a methodology and research area (Gallagher and Savage, 2023; Leijon et al., 2022; Sukackè et al., 2022).

Learning environment (setting, students, faculty), learning objectives, pedagogical format

Ocean i3 (2018–2022) and EmPACT i3 (2024–2026) are international, cross-border inter-university projects within the Basque Country-Nouvelle Aquitaine region, involving the University of the Basque Country (EHU), the University of Bordeaux (UBx), and Euskampus Foundation.

Ocean i3 was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), through the Interreg V-A Spain, France, Andorra program (POCTEFA 2014–2020), and EmPACT i3 is funded by Interreg VI-A Spain-France-Andorra (POCTEFA 2021–2027).

The overall aim of these environments is horizontal participation by students, teachers, and stakeholders in the Basque Country and Nouvelle-Aquitaine to develop responses/solutions through projects/ideas with a social, environmental, and educational impact, focused on major challenges in the ecological and social transition in this cross-border region (see Figure 1). Both respond to a positioning with regard to sustainability and the use of oceans, concerning SDG 14 (life below water), 4 (quality education), and 17 (alliances) in Agenda 2030, as recognized by the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) in September 2015. EmPACT i3 incorporates SDG 7 (renewable energies) and SDG 12 (circular economy).

Both are cross-subject as they involve a range of university subject areas (including Fine Arts, Biology, Criminology, Law, Economics, Nursing, French Philology, Engineering, Teaching, and Psychology). They are also cross-level, as bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degree students take part, as well as multilingual, as Basque, Spanish, French, and English coexist within them. Shared leadership and support in the students’ training process are shared between lecturers from both universities and bodies in the Basque Country-Nouvelle-Aquitaine region (Rekalde-Rodríguez et al., 2021). This joint work enriches students’ educational experience, developing key competencies that provide a new vision and awareness of sustainability (Cruz-Iglesias et al., 2022) and employability (Zinkunegi-Goitia and Rekalde-Rodríguez, 2022).

In general terms, as pointed out by Rodríguez-Chueca et al. (2020), to maximize the ability to put to use the specific skills of each degree and encourage the development of transversal skills to boost students’ employability, it is felt to be appropriate, pertinent, and beneficial to include them in the curriculum in the final years of a degree course. Such inclusion varies depending on the university and the degree and may involve subject course work, final dissertations or projects, or practicums (Alba, 2017). It is implemented in the second term (January–June), with the academic community and social agents taking part in three cross-border workshops (or five in the case of Ocean i3) for training, dialog, and collaborative supervision.

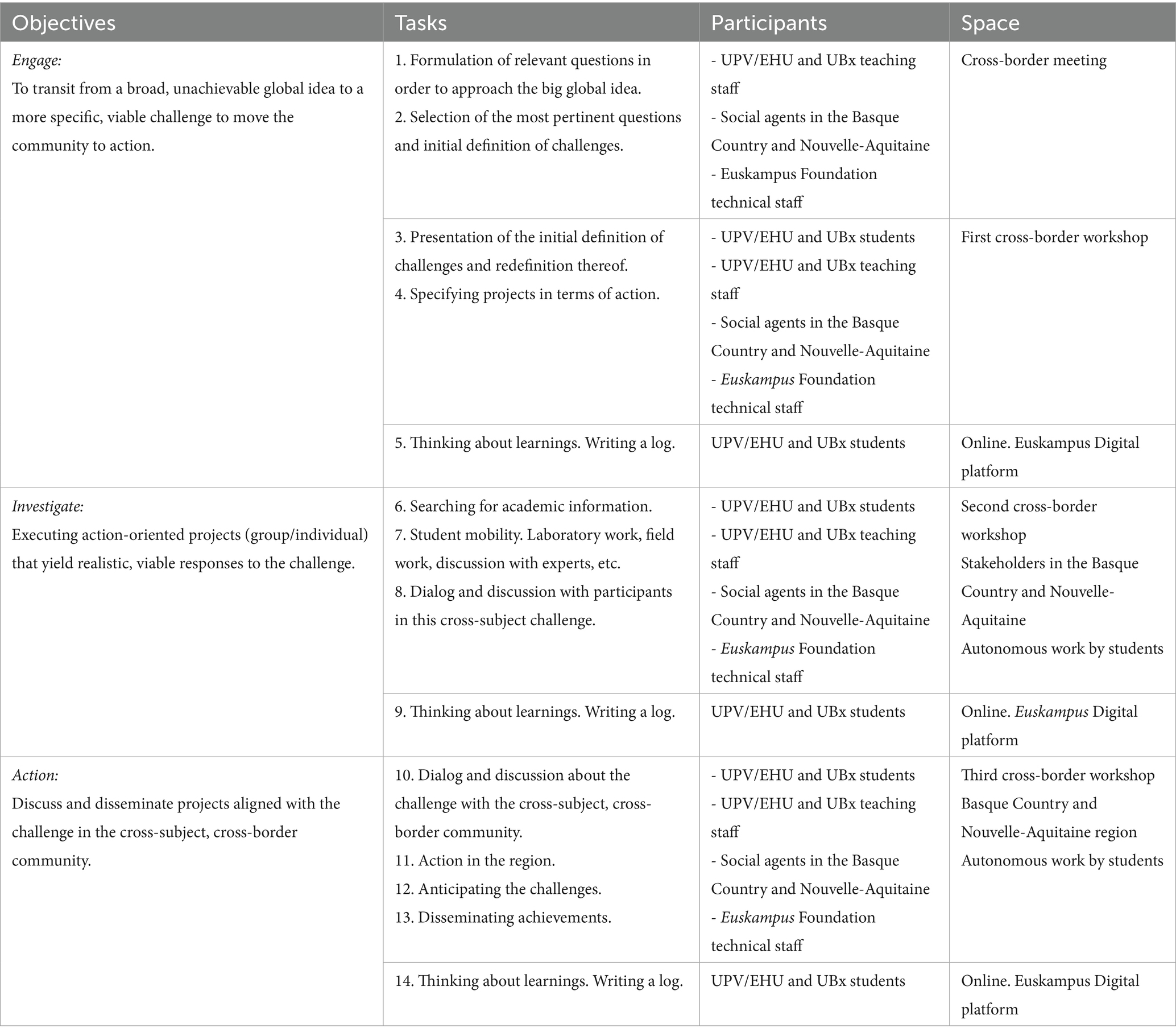

These are based on the SBE model that inspired the European universities in Enlight, in which activities are structured in three inter-connected phases: (1) engage, in which students set out from a global idea to define specific challenges; (2) investigate, in which information is compiled from primary and secondary sources and findings documented; and (3) act, in which solutions aligned with the research are developed (Enlight, 2025; Nichols et al., 2016). This methodology is implemented traditionally in academic contexts with the support of outside agents (Nichols et al., 2016; Pinto and Soto, 2021), but the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 projects have adapted the model to their complex environments, as shown in Table 1, which specifies the aims, tasks, participants, and spaces involved in each phase of the process.

In each phase, students reflect on their learning in a logbook. The whole process fosters a critical, collaborative response to real challenges based on a cross-subject approach (see Figure 2).

Results to date/assessment (processes and tools; data planned or already gathered)

The challenges are a call to action for the whole community, but above all for the students, as they are called on to investigate and reflect on the challenge and to devise, prepare, and organize actions. The results include: 11 completed projects, participation of 15 EHU students and 14 UBx students, 18 EHU teachers and 7 UBx teachers, 13 social agents, and 11 disciplines mobilized during the academic year 2024–2025. Table 2 shows the projects that students on the different degree courses at both universities set up to define, focus on, and dimension each of these broad, global challenges. In many cases, each student specified these group projects even further (territory, physical and temporal space, people involved, and so on), making them into their final degree project, doctoral thesis, subject course work, or work placement. Many of the projects were linked to a target to meet the challenge posed more directly, but indirectly, they also had an impact on other challenges. The cross-border and cross-subject projects developed products ranging from communication plans and educational materials to academic analyses, comparative studies, and sustainable prototypes, generating practical solutions and raising awareness of current environmental issues.

Through these projects, students from both universities developed competencies specific to their university studies and transversal competencies. Students become aware of their achievements through a reflective process that they record in their logbook. In the words of a student: “I believe that my participation in EmPACT i3 has fostered the development of my employability skills, as it has allowed me to strengthen abilities such as teamwork, communication with other organizations, problem-solving, and adaptability. I have also acquired practical tools and knowledge that make me feel better prepared to face the challenges of today’s work environment, such as how to create a good resume or how to implement an escape room”.

With regard to assessment, we must differentiate between two levels in the assessment of students: on the one hand, that is directly linked to the project, and on the other, that is linked to the assessment of the products derived from this participation. At the first level, the assessment aims to make students aware of the learning acquired through their participation in the open eco-learning environment represented by EmPACT i3. To this end, assessment is conceived as a formative process for students, in which the teacher monitors progress through the logbook, using a general rubric that can be adapted to the specific syllabus. The assessment criteria are organization and presentation of information, adequacy of the record of activities and monitoring of the process, personal reflection and critical analysis, appropriate use of language and written expression, creativity and visual presentation, and compliance and consistency with tasks. These criteria guide the teacher’s feedback to students, which may be written or oral, when compiling the logbook. The assessment of the logbook is not subject to a numerical grade or a mark on the student’s academic record, but rather its purpose is for students to reflect and become aware of their learning beyond the value of the results obtained. Let us say that this level corresponds more to the personal aspect of the change in attitudes that this participation has brought about, and this is recognized with a certificate issued by the project organization. In contrast, the second level is carried out outside the EmPACT i3 project and involves the evaluation of the products derived from the intervention. These are evaluated using the criteria established in the teaching program for each syllabus and degree; let us say that this corresponds to the technical aspect of each degree program.

Discussion on the practical implications, objectives, and lessons learned

This study shows how CBE, within the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 project, aligns with the principles of the SDGs proposed by UNESCO (2017), where active learning in real contexts reinforces the acquisition of key skills. As Van den Beemt et al. (2023) point out, the success of CBE lies in its ability to integrate global challenges with local solutions through a cross-subject approach like that implemented in this project involving collaboration between universities, students, and social agents in the region.

Experience backs up the ideas of Nichols et al. (2016) in their three-phase model (engage, investigate, and act), but adds a critical component: ongoing reflection using logs, as pointed out by Kolb (1984) in his theory of experiential learning, allows students to turn practical experience into significant knowledge. Furthermore, the results match the proposition by Sterling and Scott (2008) concerning the need to move on from traditional approaches to sustainability, as CBE fosters not only technical skills, but also critical thought and social commitment, aspects that Wiek et al. (2011) identify as essential in training for sustainability.

Moreover, the study backs up the ideas of Tilbury (2011) and Barth et al. (2023) about how innovative learning environments must be open and flexible, fostering cooperation between a range of figures, as achieved in the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 projects with the participation of local stakeholders. It is also shown that, as argued by Sukackè et al. (2022), the role of the teacher in CBE evolves toward that of a learning facilitator, guiding students to cope with complex challenges without imposing predetermined solutions.

In conclusion, this study validates the potential of CBE as a key methodology for EDS in higher education, in line with the arguments of Leijon et al. (2022) and Gallagher and Savage (2023); but stresses the importance of: (1) structuring systematic processes of reflection, (2) fostering solid alliances in the region, and (3) adapting existing theoretical frameworks to specific contexts. Future research should further explore the long-term impact of these experiences on students’ employability and on socio-environmental change in the regions, in line with the recommendation by Evans (2019) concerning the assessment of sustainability skills.

This study describes the process followed to put into practice the CBE methodology in the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 learning environments for sustainable development. Environments that go beyond the walls of the university take place in open, living, and permeable spaces, in contact and dialog with the social, economic, and cultural fabric of the region. The steps described and the examples given make it possible to conclude that to construct and put into practice CBE, the following is required:

Participation

By all groups (students, teachers, and social agents) in the spaces generated for dialog, exchange, and face-to-face discussion, from when the challenges are defined to when the results are disseminated. This participation involves attendance and work at cross-border workshops where

• The challenges and their impact are defined.

• Work on the challenge is monitored.

• A shared overview of the impact of the work is built.

• The value of the results obtained is maximized.

• Future lines of action are proposed.

Engagement

Constructing and developing CBE in an EDS environment seeks the interest of those who take part in the community; interest in knowing about and understanding the situation, acting in an informed, structured manner, reflecting on practices and changing/regulating one’s own behavior in relation to the issue, situation, etc. This engagement is reinforced by students spending a week with a body in the Basque Country/Nouvelle-Aquitaine region linked to the challenge on which they are working.

Commitment

To the challenge and all the tasks arising from it, encouragement is given to a responsible attitude to the work on the challenge over time, between one workshop and another, through autonomous and collaborative work in the digital space (Euskampus online platform). Also involved is the direct responsibility taken by students for individual work, such as the final degree project, master’s dissertation, voluntary practicums, subject course work, and so on, all of which have an impact on the challenge.

Reflection

The CBE process in an EDS environment aims to make students change their perspective on the situation through the critical thought generated by the experience. This involves a restructuring of the way students see the challenge and contribute with their responses (solutions, actions, and so on), above and beyond acquiring knowledge. It is the questioned narrative students build up during their training path in CBE that gives rise to this realization of what they are doing, why they are doing it, why they are doing it, and what sense it makes. A narrative set down in a logbook, which specifies the impact of their participation in this environment on the development of their employability skills.

All this aims to assist the academic educational community in the task of designing and structuring CBE-based teaching and learning processes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

IR-R: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision. PG-M: Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. EC-I: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Resources, Methodology, Project administration. OZ-G: Visualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AM-U: Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the voluntary assistance of all the people involved who have taken part in the Ocean i3 and EmPACT i3 environments over the years.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agüero, M. M., López, L. A., and Pérez, J. (2019). El aprendizaje basado en retos como modelo de aprendizaje profesionalizante. Caso del programa Universidad Europea con Comunica+A. Vivat Acad. Rev. Comun. 149, 1–25. doi: 10.15178/va.2019.149.1-24

Alba, D. (2017). Hacia una fundamentación de la sostenibilidad en la educación superior. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 73, 15–34. doi: 10.35362/rie730197

Barth, M., Jiménez-Aceituno, A., Lam, D. P. M., Bürgener, L., and Lang, D. J. (2023). Transdisciplinary learning as a key leverage for sustainability transformations. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 64:101361. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2023.101361

Bernstein, J. H. (2015). Transdisciplinarity: a review of its origins, development, and current issues. J. Res. Pract. 11:20. Available online at: https://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/510.html

Benítez Erice, D., Giraldo Valdés Pardo, V., Questier, F., and Pérez Luján, D. (2016). La producción del conocimiento experiencial de los estudiantes en la educación superior. Praxis & Saber, 7, 17–39.

Correa, M. D., and Carlachiani, C. M. (2021). Transdisciplinarity, transversality and alternative training models. Rev. PACA 11, 175–196. doi: 10.15388/ActPaed.2021.47.7

Cotton, D., Bailey, I., Warren, M., and Bissell, S. (2009). Revolutions and second-best solutions: education for sustainable development in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 719–733. doi: 10.1080/03075070802641552

CRUE. (2012) Guidelines for the Inclussion of sustainability in the curriculum. Document approved by the executive committee of the CRUE work group on environmental quality and sustainable. Communiqués issued by CRUE, the Spanish university rectors’ conference. Available online at: https://www.crue.org/Documentos%20compartidos/Declaraciones/Directrices_Sostenibli-dad_Crue2012.pdf.

Cruz-Iglesias, E., Gil-Molina, P., and Rekalde-Rodríguez, I. (2022). A navigation chart for sustainability for the ocean i3. Educational project. Sustainability 14:4764. doi: 10.3390/su14084764

Delbury, P., and y Carcamo, H. (2020). Participación en el aula y formación ciudadana para la democracia: un análisis de caso. Educación 29, 43–66. doi: 10.18800/educacion.202002.003

Dumont, H., Istance, D., and Benavides, F. (2016). La naturaleza del aprendizaje: Usando la investigación para inspirar la práctica. OCDE, UNESCO y UNICEF.

Enlight. (2025). Available online at: https://enlight-eu.org/for-educators/challenge-based-education.

Evans, T. L. (2019). Competencies and pedagogies for sustainability education: a roadmap for sustainability studies program development in colleges and universities. Sustainability 11:5526. doi: 10.3390/su11195526

Gallagher, S. E., and Savage, T. (2023). Challenge-based learning in higher education: an exploratory literature review. Teach. High. Educ. 28, 1135–1157. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1863354

Gil-Molina, P., Cruz-Iglesias, E., and Rekalde-Rodríguez, I. (2024). Developing competences in a cross-border interdisciplinary project: student and teacher perceptions of the ocean i3 project. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 21:42. doi: 10.53761/677rfm42

Kohn Rådberg, K., Lundqvist, U., Malmqvist, J., and Hagvall Svensson, O. (2020). From CDIO to challenge-based learning experiences – expanding student learning as well as societal impact? Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 45, 22–37. doi: 10.1080/03043797.2018.1441265

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. London, UK: Pearson Education.

Leijon, M., Gudmundsson, P., Staaf, P., and Christersson, C. (2022). Challenge based learning in higher education– a systematic literature review. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 59, 609–618. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2021.1892503

López-Fraile, L. A., Agüero, M. M., and Jiménez-García, E. (2021). Effect of challenge-based learning on academic performance rates in communication degree programs at the European University of Madrid. Form. Univ. 14, 65–74. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062021000500065

Márquez, A., and Blas, J. (2022). Metodologías activas y diseño universal para el aprendizaje. Influencia de las pautas DUA en el diseño de tareas, actividades y/o ejercicios de aula. J. Neuroeduc. 3, 109–118. doi: 10.1344/joned.v3i1.39661

Membrillo-Hernández, J., Ramírez-Cadena, M. J., Martínez-Acosta, M., Cruz-Gómez, E., Muñoz-Díaz, E., and Elizalde, H. (2019). Challenge based learning: the importance of world-leading companies as training partners. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 13, 1103–1113. doi: 10.1007/s12008-019-00569-4

Nichols, M., Cator, K., and Torres, M. (2016). Challenge based learner user guide. Washington, DC: Digital Promise.

OECD (2013). Innovative learning environments, educational research and innovation. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Oser, F. K., and Baeriswyl, F. J. (2001). Choreographies of teaching: bridging instruction to teaching. V. Richardson Handbook of research on teaching. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association, pp. 1031–1065.

Pérez-Rodríguez, R., Lorenzo-Martin, R., Trinchet-Varela, C. A., Simeón-Monet, R. E., Miranda, J., Cortés, D., et al. (2022). Integrating challenge-based-learning, project-based-learning, and computer-aided technologies into industrial engineering teaching: towards a sustainable development framework. Int. Educ. 26, 198–215. doi: 10.15507/1991-9468.107.026.202202.198-215

Pinto, J. A., and Soto, J. A. (2021). Challenge-Based Learning: Un Puente Metodológico entre la Educación Superior y el Mundo Profesional. Madrid: Thomson Reuters Aranzadi.

Portuguez, M., and Gomez, M. G. (2020). Challenge based learning: innovative pedagogy for sustainability through e-learning in higher education. Sustainability 12:4063. doi: 10.3390/su12104063

Prestol, J. (2020). Innovation labs: as a mechanism to create public value. Rev. Centroam. Adm. Publica 78, 162–189. doi: 10.35485/rcap78_16

Rekalde-Rodríguez, I., Barrenechea, J., and Hernandez, Y. (2021). Ocean i3. Pedagogical innovation for sustainability. Educ. Sci. 11:396. doi: 10.3390/educsci11080396

Rekalde-Rodríguez, I., Barrenechea, J., and Zinkunegi-Goitia, O. (2024). Sailing aboard the training ship Saltillo. An extracurricular experience in education for sustainable development. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s42322-024-00173-5

Rekalde-Rodríguez, I., Gil-Molina, P., and Cruz-Iglesias, E. (2023). Institutional teaching choreographies in education for sustainability in times of pandemic: the ocean i3 project. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 24, 1–20. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-02-2022-0039

Rodríguez-Chueca, J., Molina-García, A., García-Aranda, J. C., Pérez, J., and Rodríguez, E. (2020). Understanding sustainability and the circular economy through flipped classroom and challenge-based learning: an innovative experience in engineering education in Spain. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 238–252. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2019.1705965

Sabbah, R. (2021). Foreword by the president of global campaign for education. Transformative education: meanings and policy implications. Global campaign for education, p. 2. Available online at: https://campaignforeducation.org/images/downloads/f1/1075/transformative-education-meanings-and-policy-implications.pdf.

Sáez de Cámara, E., Fernández, I., and Castillo-Eguskitza, N. (2021). A holistic approach to integrate and evaluate sustainable development in higher education. The case study of the University of the Basque Country. Sustainability 13:392. doi: 10.3390/su13010392

Sterling, S., and Scott, W. (2008). Higher education and ESD in England: a critical commentary on recent initiatives. Environ. Educ. Res. 14, 386–398. doi: 10.1080/13504620802344001

Sukackè, V., Guerra, A. O. P., Ellinger, D., Carlos, V., Petronienė, S., Gaižiūnienė, L., et al. (2022). Towards active evidence-based learning in engineering education: a systematic literature review of PBL, PjBL, and CBL. Sustainability 14:13955. doi: 10.3390/su142113955

Tilbury, D. (2011). Education for sustainable development: an expert review of processes and learning. UNESCO. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001914/191442e.pdf.

UNESCO. (2014). UNESCO roadmap for implementing the global action Programme on education for sustainable development. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002305/230514e.pdf.

UNESCO. (2017). Educación para los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. Objetivos de aprendizaje. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252423.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution passed by the general assembly on 25th September 2015. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed September 25, 2015).

Van den Beemt, A., Van de Watering, G., and Bots, M. (2023). Conceptualising variety in challenge-based learning in higher education: the CBL-compass. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 48, 24–41. doi: 10.1080/03043797.2022.2078181

Wals, A. E. J. (2009). A mid-DESD review: key findings and ways forward. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 3, 195–204. doi: 10.1177/097340820900300216

Weybrecht, G. (2017). From challenge to opportunity–management education's crucial role in sustainability and the sustainable development goals–an overview and framework. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 15, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2017.02.008

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., and Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 6, 203–218. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

Yang, Z., Zhou, Y., Chung, J. W., Tang, Q., Jiang, L., and Wong, T. K. (2018). Challenge based learning nurtures creative thinking: an evaluative study. Nurse Educ. Today 71, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.09.004

Zabalza, M. A., and Zabalza, M. A. (2019). Coreografías didácticas institucionales y calidad de la enseñanza. Linhas Crít. 25:586. doi: 10.26512/lc.v25i0.24586

Zinkunegi-Goitia, O., and Rekalde-Rodríguez, I. (2022). Employability within an education for sustainability framework: the ocean i3 case study. Educ. Sci. 12:277. doi: 10.3390/educsci12040277

Keywords: higher education, challenge-based learning, education for sustainable development, SDG 4, environments for innovation

Citation: Rekalde-Rodríguez I, Gil-Molina P, Cruz-Iglesias E, Zinkunegi-Goitia O and Mendia-Urrutia A (2025) Challenge-based education methodology within sustainable development environments: from ocean i3 to EmPACT i3 experience. Front. Educ. 10:1698274. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1698274

Edited by:

Rolando Salazar Hernandez, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, MexicoReviewed by:

Christine Evain, University of Rennes 2 – Upper Brittany, FranceYurley Hernandez Peña, Universidad Simon Bolivar, Colombia

Copyright © 2025 Rekalde-Rodríguez, Gil-Molina, Cruz-Iglesias, Zinkunegi-Goitia and Mendia-Urrutia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Itziar Rekalde-Rodríguez, aXR6aWFyLnJla2FsZGVAZWh1LmV1cw==; Aitor Mendia-Urrutia, YWl0b3IubWVuZGlhQGVodS5ldXM=

Itziar Rekalde-Rodríguez

Itziar Rekalde-Rodríguez Pilar Gil-Molina

Pilar Gil-Molina Esther Cruz-Iglesias

Esther Cruz-Iglesias Olatz Zinkunegi-Goitia

Olatz Zinkunegi-Goitia Aitor Mendia-Urrutia

Aitor Mendia-Urrutia