- 1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Sciences, São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP), Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Psychology Centre of the University of Porto (CPUP), Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto (FPCEUP), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Inclusive resources can contribute to the development of inclusive teaching practices and equity in education. The study aimed to analyze the perception of Brazilian and Portuguese teachers who work with students with special educational needs regarding the inclusive resources available and their inclusive practices, correlating them with personal variables (age, gender) and professional variables (teaching experience, education cycle in which they work, and participation in Special and Inclusive Education courses). A total of 85 Brazilian and 94 Portuguese teachers from public basic education schools participated in the study. The majority were women, with a mean age of 43.6 years among Brazilian teachers and 54.5 years among Portuguese teachers. For most Brazilian teachers, teaching experience was under 20 years, whereas for Portuguese teachers, it was over 20 years. Brazilian teachers predominantly worked in Early Childhood Education and Elementary School I, while Portuguese teachers mainly worked in the third cycle of basic education. Regarding training, 70% of Brazilian teachers and 42% of Portuguese teachers had completed courses in Special and Inclusive Education or related areas. Data collection employed a sociodemographic questionnaire and the Resources and Practices for Inclusive Education instrument, composed of 24 items: nine to assess available resources and 15 to assess inclusive practices in the classroom. Data were collected online. Results indicated that 80% of Portuguese teachers and 34% of Brazilian teachers agreed that resources for inclusion were available. Regarding inclusive practices, 98% of teachers from both countries reported using them in the classroom. Among Brazilian teachers, those with more students specific needs and those who had training in inclusive education perceived more available resources and reported better practices. Brazilian teachers with less experience and those teaching students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and alongside students with other conditions perceived fewer available inclusive resources. Among Portuguese teachers, those who perceived more resources available reported more inclusive practices, and teachers who used additional measures exhibited higher levels of inclusive practices.

1 Introduction

Promoting more inclusive and equitable education has become a central priority for policymakers, researchers, and educational agents (Alves, 2019; Ainscow, 2020; UNESCO, 2017). Ensure that educational systems provide all children with the opportunity to learn together, addressing their needs and overcoming barriers, including vulnerable and marginalized groups it is part of the current education guidelines (Santos and Mendes, 2021; UNESCO, 2020).

In some countries inclusive education is still understood as a proposal intended only for children who need some kind of help to perform their school activities. However, the concept has expanded to encompass all students (Abreu and Grande, 2021; Ainscow, 2020; Alves, 2019; Schwab, 2019; Vrǎşmaş, 2018; Zerbato and Mendes, 2018), o que has led schools around the world to adapt by through the implementation of support structures and human and material resources for learning support and school inclusion. The objective is to enable everyone to acquire knowledge, in consonance with their culture, which must be considered throughout the entire teaching and learning process (Ainscow, 2020; Brasil, 2008).

However, the way countries are attempting to implement inclusion varies widely, as do the challenges each faces, often differing even within the same country. The decision on whether a child is entitled to special resources to support inclusive education may differ among stakeholders. In some countries, this choice is made primarily by parents, whereas in others, professionals decide which school is most appropriate (Schwab, 2019).

In Brazil, the basic school education system is organized into four levels: Early Childhood Education (up to 5 years old); Elementary School—Early Years (1st to 5th grade); Elementary School—Later Years (6th to 9th grade); and High School (1st to 3rd year). The responsibility for providing access to education in public schools in Brazil is shared between the municipal and state governments (Brasil, 1988). After completing these stages of education, students can proceed to higher education in state and federal public schools, as well as private institutions.

At all these levels, according to the National Education Policy from the Perspective of Inclusive Education (Brasil, 2008), special and inclusive education permeates them transversally, from Early Childhood Education to Higher Education, integrating the pedagogical proposal of regular education. Resolution No. 4, of October 2, 2009, established Operational Guidelines for Specialized Educational Assistence (SEA) in Basic Education, as a support service for students with disabilities, global developmental disorders, and high abilities/giftedness, assisted by Special Education teachers in Multifunctional Resource Rooms, to complement and/or supplement their education (Brasil, 2009). Although a diagnosis is not mandatory to access Specialized Educational Assistance (Ministério da Educação e Cultura (MEC), 2014), it is required in many schools, the teacher receiving information about his student's diagnosis (Silva and Szymanski, 2020). According to the authors, reports from teachers indicate that they feel safer when they know what condition the child has.

The education system in Portugal is organized into four levels: Pre-school (3 to 6 years old); Basic Education, which comprises three sequential cycles: 1st Cycle: from 1st to 4th grade; 2nd Cycle: from 5th to 6th grade; 3rd Cycle: from 7th to 9th grade (12 to 15 years old); and Secondary Education (10th to 12th grade) (Portugal, 1986). After completing these stages of education, students can proceed to higher education, which includes universities and polytechnic institutes. In Portugal, Law no. 116/2019, of September 13, is currently in force. This law makes the first amendment, through parliamentary review, to Decree-Law no. 54/2018, of July 6, which establishes the legal framework for inclusive education.

Since then, the Portuguese education system has adopted a holistic view of education and an integrated, continuous approach to the school trajectory, enhancing the inclusion of all students regardless of their personal or social conditions (Alves, 2019; Portugal, 2018). Support resources are based on two methodological options: a) the multi-level approach, which provides an integrated set of learning support measures according to each student's needs, and b) the Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which proposes flexible pedagogical practices to meet classroom diversity (Pereira et al., 2018).

Consequently, a diagnosis is not required as a mandatory condition for student intervention (Silveira-Maia, 2024). Learning supports are organized into three levels: universal, selective, and additional (Silveira-Maia, 2024; Pereira et al., 2018). Universal measures are aimed at all students based on UDL, focusing on pedagogical differentiation. Selective and additional measures are applied when universal measures are insufficient to ensure learning and access to the curriculum. Selective measures involve reinforcement and tutorial support, while additional measures are more specific, involving curricular adaptations, more structured teaching resources and methodologies (Silveira-Maia, 2024) with more frequent and intensive interventions tailored to each student's needs and potential, usually over an extended period (Pereira et al., 2018).

It is noteworthy that despite the increase in the enrollment of students who need support for learning in mainstream schools in both countries (Brasil, 2008, 2023; Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Económico (OCDE), 2022; Carvalho et al., 2019). The literature highlights the complexity and diversity in implementing inclusive practices as well as the ongoing challenges mainstream schools face in providing a quality response to diversity (Azorín and Ainscow, 2020; UNESCO, 2022).

The studies by Capellini (2018) and Carvalho et al. (2019) highlighted challenges and advances in the implementation of inclusive education in differents contexts. In Brazil, Saloviita (2020) identified structural and pedagogical barriers, such as a lack of planning to meet students' needs, inadequate infrastructure, insufficient teacher training, non-inclusive practices, and low family participation. In Portugal, the teachers surveyed by Capellini (2018) highlighted as positive points the appreciation of differences, the support offered to students and the cooperation between teachers and students, although they pointed out limitations in resources and difficulties in lesson planning to meet diversity. Both studies reinforced the need to improve policies, practices, and resources to consolidate truly inclusive education.

Strategies have been tested to promote more inclusive practices. Among them, in the Brazilian context, are Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (Santos and Mendes, 2021). The Multilevel Approach and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) are recommended for implementing inclusive practices in the Portuguese context (Alves et al., 2020; Portugal, 2018; UNESCO, 2020). Furthermore, specific resources for individual cases may be necessary to ensure learning and good academic performance. However, in both countries, this is still the case lack of clear specification of the indicators of resources necessary for an educational system to be considered inclusive, high-quality, and equitable (Goldan and Schwab, 2020; Santos et al., 2023).

Inclusive educational resources have been widely studied in many countries, including Brazil and Portugal, noting their insufficiency is an extremely relevant variable for educational quality (Ainscow, 2020; Goldan and Schwab, 2020; Alcaraz et al., 2024; Carvalho et al., 2019; Santos and Capellini, 2021). They can be categorized as: personal, including teaching and non-teaching professionals; technological, relating to teaching and learning materials; and technical, such as spatial resources related to school accessibility (Carvalho et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2018). Research in this area is necessary to better understand how educational resources can become barriers or facilitators for learning (Kerr and Ainscow, 2022).

In addition to the availability of inclusive educational resources, teachers are frequently encouraged to apply new strategies to overcome barriers and enable the inclusion of all students in the classroom (Carvalho et al., 2019; Alcaraz et al., 2024; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2018). Implementing new strategies may be linked to opportunities for training and the exchange of successful experiences. However, the lack of continuous teacher training is identified as a challenge for inclusive classroom practice (Alves et al., 2020; Carvalho et al., 2019; Alcaraz et al., 2024). Another important factor for the effective use of resources is training teachers on how to organize and properly integrate them into teaching–learning processes (Gallardo et al., 2019).

Recent studies on teacher perceptions indicate that they report using inclusive teaching practices (Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020; Schwab et al., 2022). Sharma et al. (2021) also emphasized their role in the success of inclusive education, though implementation requires teachers' openness to change and the development of pedagogical strategies that respond to all students' needs (López-Azuaga and Riveiro, 2018).

(Azorín and Ainscow 2020) stressed that, given the complexity of the processes involved and the challenges to creating more inclusive contexts, inclusion must be understood in relation to particular contexts. Some factors related to teachers' personal and professional characteristics, as well as contextual factors, may influence pedagogical practices (Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020). However, research on factors influencing teachers' inclusive practices remains scarce (Sharma et al., 2021).

A starting point can be identifying the strengths and weaknesses of inclusive education present in each school and across the school community. The literature suggests using the Themis Inclusion Tool to monitor school progress (Azorín et al., 2019; Azorín and Ainscow, 2020). The instrument was translated and adapted into Portuguese as the Resources and Practices for Inclusive Education (RPEI) to facilitate school reflection on contexts, resources, and processes supporting teachers' work in education and to guide necessary changes along the path to inclusion (Carvalho et al., 2022).

Cruz et al. (2023) analyzed the relationship between inclusive practices of teachers working in public and private schools in Portugal and personal and professional characteristics, including gender, education level, years of experience, roles performed in the school, and perception of inclusive resources. Nine hundred twenty-four teachers participated, responding to a sociodemographic questionnaire and the RPEI. Results showed that inclusive practices were significantly associated with teachers' perceptions of inclusive resources, education levels, and gender. Roles and years of teaching experience were not significantly associated with inclusive practices, likely due to the influence of prior and intense contact with diversity.

A study on the perceptions of 450 Portuguese teachers regarding inclusive education challenges identified strengths as acceptance and respect for differences, provision of student support, and cooperation between teachers and students, while limited and insufficient resources related to inclusion were identified as weaknesses (Carvalho et al., 2019). Abreu and Grande (2021), investigating the difficulties and solutions reported by 17 Portuguese educational professionals regarding inclusive education, identified lack of resources (e.g., lack of training, lack of time) and adjustment to new role definitions by the entire educational community as the main challenges.

In the study by Carvalho et al. (2024), 539 Portuguese teachers evaluated variables such as self-efficacy, teaching experience with disabilities, prior training in inclusive education, and knowledge of laws and educational policies. Results indicated favorable attitudes toward the inclusion of children with disabilities, with reported use of inclusive practices above the instrument's average score. About 50% had training in inclusive education, but most reported extensive experience with this population. Other studies have examined the influence of attitudes and self-efficacy regarding inclusive education, suggesting a positive association with the use of inclusive practices (Schwab et al., 2022; Sharma and Sokal, 2016). These results align with findings by Krischler et al. (2019) and Schwab and Alnahdi (2020), who identified years of experience as a predictor of inclusive practices, with more experienced educators employing more diverse pedagogical strategies. However, Saloviita (2020) found that teachers with fewer years of service demonstrated more positive attitudes toward inclusive education.

An important point is the exchange of experiences between countries. According to Hernández-Torrano et al. (2022), most research on inclusive education still comes from a limited number of countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. The lack of a solid research base in many countries represents a challenge to advancing the global inclusive education agenda because “there is no one model of inclusive education that suits every country's circumstances” (Mitchell, 2005, p. 19).

Countries lacking research can benefit from dialogue among researchers from different geographical backgrounds to exchange inclusive education strategies and practices capable of addressing complexities, social dilemmas, and educational challenges common across nations (Pather, 2007). In the present study, given the cultural and linguistic similarities, identifying and comparing inclusive resources and practices in Portugal and Brazil may provide valuable insights for promoting inclusive education in both nations.

Additionally, in both countries, new legislation has defined the parameters of inclusive education, requiring teachers to adapt to them in order to guarantee a quality education for all students. However, considering both strengths and weaknesses, advantages and disadvantages, the results are inconclusive. There is more consistency regarding the lack of available inclusive resources, but there is disagreement regarding the use of inclusive pedagogical practices. Using an instrument that encompasses both variables can be useful for evaluating teachers' perceptions of them.

The present study aimed to address the following questions, intending to confirm or refute data from other studies (Capellini and Zerbato, 2019; Carvalho et al., 2019): How do Brazilian and Portuguese teachers perceive the available inclusive resources and their inclusive practices? What are the strengths and weaknesses regarding available resources and inclusive practices identified among Brazilian and Portuguese teachers? Is there a relationship between the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices with variables such as gender, length of teaching experience, direct work with students receiving selective and additional measures, and training in inclusive education among Brazilian and Portuguese teachers?

The study intended to: a) analyze the perception of Brazilian and Portuguese teachers who work with students with special educational needs regarding available inclusive resources and their inclusive practices; b) identify strengths and weaknesses in the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices; and c) correlate the perception of available inclusive resources and their inclusive practices with personal and professional variables of Brazilian and Portuguese teachers.

2 Method

2.1 Ethical procedures

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP) Faculty of Sciences, under opinion number 6.871.899 (CAAE: 79401624.3.0000.5398) and by the Municipal Education Departments of the municipalities of São Paulo, Brazil. In Portugal, the research received favorable approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto with Ref 2025-06-01b. Also, authorization was requested from the School Grouping Directorate, in accordance with the required ethical procedures.

2.2 Participants

The convenience sample, consisted of 85 Brazilian teachers and 94 Portuguese teachers from various educational levels in public Basic Education schools. The Brazilian teachers worked in schools in municipalities of the State of São Paulo, while the Portuguese teachers worked in a school grouping in the metropolitan area of Porto. All Brazilian participants worked with students with Special Educational Needs. Among the Portuguese teachers, 72.4% worked directly with students receiving selective measures, and of these, 49.0% worked with students receiving both selective and additional measures. Table 1 presents the characterization of the teachers by country.

3 Materials

3.1 Socioprofessional questionnaire

For this study, a questionnaire was developed to collect participants' characteristics (gender and age) and professional experience (years of teaching experience, teaching cycle/grade, and training in special and inclusive education) to describe the sample. Additional data on professional characteristics were collected to address the research questions of the study: direct work with students receiving learning and inclusion support for Portuguese teachers, and the diagnoses of students currently under the responsibility of Brazilian teachers.

3.2 Recursos e Práticas para a Educação Inclusiva (RPEI)

The Themis Inclusion Tool, developed by Azorín et al. (2019), was translated and adapted for the Portuguese context by Carvalho et al. (2022), under the name Recursos e Práticas para a Educação Inclusiva. For the Brazilian context, some terms were adapted, evaluated by consensus by the Brazilian and Portuguese researchers, in order to avoid biases in the understanding of the statements. The instrument was designed to facilitate school reflection on the contexts, resources, and processes that support teachers' work. It consists of 24 items, with statements rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater inclusion, measuring two factors: (1) Inclusive Resources – nine items (e.g., human resources – “the school's human resources include specialized professionals and operational assistants to respond to the diversity of its students”; technical resources – “the school's equipment and furniture are adapted to students' needs”; and technological resources – “the computer labs are equipped with enough computers for the number of students”); (2) Inclusive Practices – 15 items (e.g., beliefs – “diversity enriches the educational process” and behaviors – “I provide supplementary activities for students who complete tasks more quickly”). The choice of the RPEI instrument was based on the fact that it had been adapted and validated for the Portuguese context and allows for determining, from the teachers' perspective, the availability of inclusive resources and practices. For use in Brazil, the same instrument validated in Portugal was applied without modifications. Both subscales demonstrated good psychometric properties, with Cronbach's alpha values of 0.815 (Inclusive Resources) and 0.902 (Inclusive Practices) (Carvalho et al., 2022; Cruz et al., 2023). In this study, the overall instrument showed good internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.882, while the Inclusive Resources subscale had a value of 0.813, and the Inclusive Practices subscale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a value of 0.932.

3.2.1 Data collection procedures

After the ethical procedures, authorization was requested from the authors for the application of the RPEI instrument (Carvalho et al., 2022), conducted concurrently and independently in both countries. In the Brazilian municipalities that approved the research, contact with the schools was made via the schools' institutional email, providing information about the study, its objectives, and a Google Forms link for distribution to the teachers. In Portugal, the study was disseminated to teachers via institutional email, requesting participation in completing an online questionnaire on the Qualtrics platform.

Participants in both countries only gained access to the questionnaires after signing the consent form. This cover sheet contained the study objectives, ethical procedures, and informed consent declaration, as well as the email addresses of the participating researchers for any clarifications. They were informed that participation was voluntary, with minimal or no risk, that they could withdraw at any time, and that the data would remain confidential. Data confidentiality was ensured, processed in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation for research purposes, and not disclosed individually. Completion of the Socioprofessional Questionnaire and the self-report RPIE instrument was estimated to take approximately 15 min and was available from October to November 2024. The data were stored on password-protected electronic media, with access restricted to the researchers. Participants were assured of the right to access the study results upon request.

3.2.2 Data analysis

For data analysis, the data from each subscale, Inclusive Resources and Inclusive Practices, were considered separately, according to the number of items. The Inclusive Resources subscale comprised nine items, with a minimum score of nine and a maximum of 45 points. Classifications were established from the Likert scale items as follows: Totally Disagree (TD) corresponded to 9 points, Disagree (D) to 10 to 18 points, Disagree/Agree (D/A) to 19 to 27 points, Agree (A) to 28 to 36 points, and Totally Agree (TA) to 37 to 45 points. The Inclusive Practices subscale comprised 15 items, with a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 75 points. Classifications from the Likert scale items were as follows: Totally Disagree (TD) corresponded to 15 points, Disagree (D) to 16 to 30 points, Disagree/Agree (D/A) to 31 to 45 points, Agree (A) to 46 to 60 points, and Totally Agree (TA) to 61 to 75 points.

Based on these classifications, it was possible to identify strengths and weaknesses in both the available resources and inclusive practices. Strengths were identified as the three items with the highest frequency of “Agree” and “Totally Agree” responses, whereas weaknesses were identified as the three items with the lowest frequency of “Agree” and “Totally Agree” responses.

Correlation analyses were performed separately for each group, considering the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices as outcome variables, using Spearman's test. For Portuguese teachers, the independent variables were gender, age, length of experience, participation in Special and Inclusive Education courses, and measures applied with students (direct work with selective and/or additional measures or no measures currently needed). For Brazilian teachers, the independent variables were gender, age, length of experience, participation in Special and Inclusive Education courses, weekly working hours, and student diagnoses (Autism Spectrum Disorder [ASD], ASD + other conditions, and other).

4 Results

Table 2 presents the data for the two groups of teachers regarding their overall perception of available resources. Considering the frequencies for “Agree” and “Totally Agree” as classifications indicating a favorable position toward the existence of inclusive resources available to teachers and, consequently, to students, it can be seen that 34.0% of the Brazilian sample perceived these resources as available, while in the Portuguese sample this perception was 60.6%. Among the participants who were uncertain whether they agreed or disagreed about resource availability, 39.5 were from the Brazilian sample and 34.0% from the Portuguese sample. Those who “Disagreed” or “Totally Disagreed” accounted for 26.5% of the Brazilian participants and 5.3% of the Portuguese teachers.

Table 2. Absolute and relative distribution of teachers from the Brazilian and Portuguese samples regarding their perception of available inclusive resources.

Next, the resources that teachers perceive as adequate and those requiring strategies to provide them were identified. It was decided to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the available resources according to the teachers' perceptions (Table 3). Among Portuguese teachers, the strengths were associated with items 2, 6, and 9. These refer to the support received from the inclusive education support team, the school's accessibility, and the availability of resources for acquiring materials for students. Regarding weaknesses, the items evaluated were 1, 5, and 3, which relate to human resources perceived as insufficient to meet student diversity, such as specialized professionals and operational assistants, as well as scarce alternative or more complex resources for students who need them.

Table 3. Analysis of strengths and weaknesses related to the perception of available inclusive resources.

Among Brazilian teachers, the strengths identified in the available resources referred to items 6, 7, and 8 (Table 3). These were the items with the highest frequencies of agreement, although none reached 50%. Items 6 and 7, with the highest frequencies, referred to the school's accessibility conditions, including both the building and equipment and furniture adapted to meet students' needs. Item 8 referred to extracurricular activities available to students, although the frequency of disagreement exceeded that of agreement. Regarding weaknesses, the items evaluated were 1 and 3, the same as for Portuguese teachers, related to the human resources available for teachers and students. Item 4 was also more frequent, indicating disagreement that, among the available resources, computer labs were sufficient to meet all students' needs.

Table 4 presents the data regarding how teachers perceived their own inclusive practices. Among Brazilian and Portuguese teachers, 99% agreed or totally agreed that their practices were inclusive.

Table 4. Absolute and relative distribution of teachers from the Brazilian and Portuguese samples regarding the practices used.

The analysis of inclusive practices showed that, among Portuguese teachers, more than 86% reported using them with their students, with 95% agreeing or fully agreeing that they promoted inclusive values among students, prevented discrimination, shared materials with colleagues, reviewed lesson plans and adapted them to students' needs, and used varied assessment instruments, valuing student progress. Among Brazilian teachers, 73% or more agreed or fully agreed that they used inclusive practices. More than 90% agreed or fully agreed that they provided supplementary activities for their students, used varied assessment instruments, regularly reviewed lesson plans and adapted them to students' needs, and organized classes according to students' characteristics. They also agreed or fully agreed that learning support measures are a shared responsibility between teachers and the specialized technical team.

Correlation analyses were conducted separately for each group. For Portuguese teachers, the outcomes considered were the perception of available resources and inclusive practices, which were associated with gender, age, teaching experience, participation in special and inclusive education courses, and direct work with selective and additional measures. A significant positive association of moderate magnitude was observed between the perception of inclusive resources and inclusive practices (r = 0.211, p < 0.05), suggesting that greater perception of inclusive resources is related to increased inclusive practices. A significant negative correlation of moderate magnitude was also identified between inclusive practices and direct work with students receiving additional measures (r = −0.206, p < 0.05). This negative correlation, considering the coding of the variable (1 = yes, 2 = no), suggests that teachers working directly with students receiving additional measures exhibit higher levels of inclusive practices.

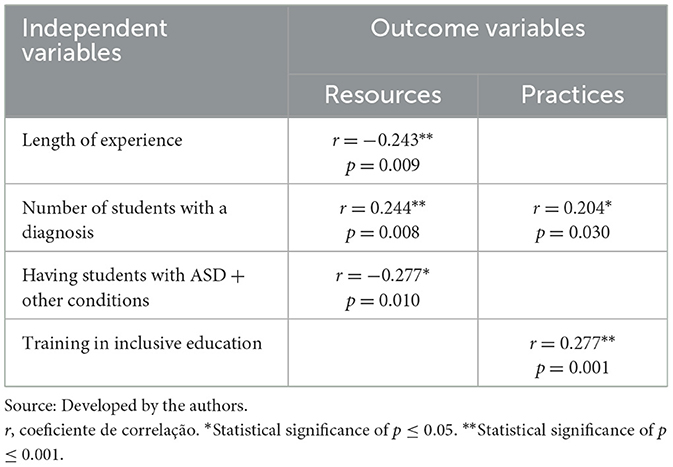

For Brazilian teachers, the outcomes considered were the perception of inclusive resources available and inclusive practices, and the independent variables included gender, age, teaching experience, number of students with diagnoses, participation in special and inclusive education courses, weekly hours worked, and student diagnoses (ASD, ASD + other conditions, and others). Teaching experience showed a negative moderate correlation with perceived resources, meaning that the longer the teaching experience, the worse the perception of available resources. The number of students with a diagnosis correlated positively with better perception of available resources and with better practices, indicating that higher numbers of students correspond to improved perceptions and practices. Having students with ASD and other conditions correlated negatively with the perception of available resources, meaning that teachers working with students with diverse conditions, including ASD, perceive the resources as less adequate. Training in inclusive education correlated positively with educational practices, meaning that teachers with specific training reported using more inclusive practices (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlation analysis between the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices with the socio-professional variables of Brazilian teachers.

5 Discussion

The first objective of the study was to analyze the perception of Brazilian and Portuguese teachers who work with students who need some type of specific support, regarding the inclusive resources available and their inclusive practices. The results indicated that Portuguese teachers reported a greater perception of inclusive resources compared to Brazilian teachers. In Brazil, similar results regarding the lack of material and human resources, which hinder inclusive education, are also highlighted in the literature (Campos et al., 2019; Capellini and Zerbato, 2019; Santos and Capellini, 2021; Sebastian-Heredero and Anache, 2020; Feitosa and Araújo Filho, 2023). In Portugal, Carvalho et al. (2019) and Santos et al. (2014) found that the inclusive resources available are limited and insufficient.

Although the results found in this study present a more positive picture of the availability of inclusive resources in Portuguese schools, these are still, according to the perception of some of the participating teachers, insufficient to meet the specific needs of the schools, reiterating the findings of previous studies in Portugal (Carvalho et al., 2019; Alves et al., 2020; Abreu and Grande, 2021; Cruz et al., 2023). Ensuring quality inclusive education for all is supported by various documents that advocate for the availability of adequate human and material resources as a means to overcome barriers that prevent access to educational opportunities (Alcaraz et al., 2024; Gitschthaler et al., 2021; Goldan and Schwab, 2020; Schneider et al., 2018; Tébar, 2018). Therefore, the school, as an educational institution, must have sufficient resources adjusted to the characteristics of each student so that all feel welcomed, safe, and able to achieve their goals (Goldan et al., 2021; Valenzuela et al., 2014).

Brazilian and Portuguese teachers agreed or fully agreed that they promote inclusive values among students and that they use inclusive practices. However, researchers have highlighted that a greater variety of available resources is related to the planning and use of more inclusive practices by teachers (Arnaiz-Sánchez et al., 2023; Cruz et al., 2023), since adequate and accessible resources are essential for implementing effective inclusive practices, and insufficient perception of resources is a barrier to inclusion (Cruz et al., 2023; Finkelstein et al., 2021).

Apesar das críticas que os professores dos dois países, mais fortemente os brasileiros, fizeram com relação aos recursos inclusivos disponíveis, eles percebem suas práticas como inclusivas. Elas são inclusivas desde a prevenção da discriminação até a avaliação, o planejamento e a utilização de práticas pedagógicas diferenciadas e adequadas às necessidades de todos os seus alunos, aí incluídos aqueles who need differentiated strategies for good academic performance.

Despite the criticisms from teachers in both countries, especially Brazilian teachers, regarding the available inclusive resources, they perceive their own practices as inclusive. These practices range from preventing discrimination to assessment, planning, and the implementation of differentiated pedagogical strategies tailored to the needs of all students, including those who need differentiated resources. The results of Portuguese teachers corroborate other recent studies (Cruz et al., 2023; Carvalho et al., 2024), whose participants had high levels of perception of the implementation of inclusive practices, especially teachers at the first level of education. Previous studies, such as Carvalho et al. (2019), found that teachers reported that implementing inclusive practices in schools was a major challenge, especially with limited and insufficient resources. Santos et al. (2014), in a study with teachers from northern Portugal, identified that around 50% of them did not feel prepared to meet the needs of their students, even though they valued collaboration with specialized professionals for the development of inclusive practices. It is likely that the experience gained over the past years working with this population has resulted in the more inclusive practices observed in the present study.

In Brazil, participants in the study by Coutinho and Tessaro (2024) reported the importance of adapting content, establishing routines, and using differentiated pedagogical practices when working with children with ASD, attributing these practices to the continuing education they had undertaken. Pinheiro Filho et al. (2024) highlighted that inclusive pedagogical practices are crucial to ensure the real inclusion of students who require special strategies to learn. According to the authors, new educational technologies are promising for adapting teaching to the needs of their students. Martins et al. (2025) confirm that the use of adapted resources and assistive technology has proven effective for student learning. However, access to this information requires greater investment in teacher training. Older studies, such as Capellini and Zerbato (2019), indicated that teaching practices were still minimally inclusive. The data seem to indicate a substantial improvement in the use of inclusive practices in both countries, even though they complain about limited resources. The cited studies are based on self-report data but appear to indicate a favorable change in inclusive practices, which was less observed a few years ago. Dias and Cadime (2018) noted that there are few studies evaluating teachers' inclusive practices, especially those of early childhood education teachers, and that there are few validated instruments for this purpose.

One of the objectives of the instrument used, the RPEI, is to enable the identification of aspects requiring greater investment and planning. In comparing the strengths and weaknesses of the available inclusive resources among Brazilian and Portuguese teachers, some similarities and differences were observed, albeit at different frequencies. Both groups agreed that the schools are architecturally accessible, perceived by about 50% of Brazilian teachers and 66% of Portuguese teachers.

Araújo et al. (2023) highlighted that Brazilian laws guaranteeing school accessibility have evolved; however, not all schools are adequately prepared to serve children of ramps or specific furniture. In Brazil, Menino-Mencia et al. (2019) identified that both the school staff and the students and parents reported the need for more adequate physical structures in schools, mainly regarding physical accessibility, to ensure inclusion. In another study, (Silva Filho and Kassar 2019) found that 16 of 17 schools in a municipality that received adaptations for students with disabilities still had a set of spaces that did not meet the technical standards, which, in most cases, completely rendered their use unviable.

On the other hand, Rocha et al. (2018) identified in the Portuguese context that most participants in their study fully agreed that schools sought to make their buildings accessible to all students (79.0%), as well as admit all students from their geographic area (83.9%). Similar results were also observed by Machado (2024).

Among the resource questions answered by Brazilian teachers, the most frequently selected were questions 7 and 8, referring to adapted furniture and extracurricular activities offered to students with differentiated needs. However, the frequency was low, with fewer than 38% of teachers agreeing that they were actually present. Insufficient resources constitute a barrier that could hinder the promotion, presence, participation, and learning of all students in the same educational context (Ainscow, 2020).

However, this is not always the case, as some schools, despite efforts to adapt them for all children, often lack desks suitable for students with disabilities, or, in some situations, the responsibility for providing them falls to the students' parents (Santos, 2019). One hypothesis for the teachers' agreement with this statement may be related to a lack of knowledge about resources for the inclusion of students with specific needs.

Regarding the provision of extracurricular activities for student development, in 16 schools analyzed by Santos and Capellini (2021), only six offered extracurricular activities in the after-school period to their students, such as music classes (guitar, flute), dance classes (capoeira), computer classes, chess, and school band, corroborating the data found in the present study. Among Portuguese teachers, for the other two strongest points, more than 70% agreed that they have the support they need from the team of professionals, and about half agreed that the school has a resource fund for the acquisition of materials suitable for students' needs.

In Portugal, Santos et al. (2014) investigated teachers' perceptions regarding the inclusion of students that require selective or additional measures in regular schools. The participants revealed that there were not enough human resources in schools to create teams capable of responding to the needs of all students enrolled in regular schools. Despite some increase in the number of resources offered to students who need one of these measures, such as specialized teams to support these students in conventional schools, this number is insufficient compared to the high number of students included [Alves et al., 2020; Direção Geral das Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência (DGEEC), 2011, 2018], making it difficult to provide adequate support for these students.

In Portugal, Santos et al. (2014) investigated teachers' perceptions regarding the inclusion of students who need selective or additional measures in regular schools. Regarding weaknesses, Brazilian and Portuguese teachers scored lowest on two questions related to the insufficient number of specialized professionals and appropriate resources for students, which are important for promoting learning. However, Portuguese teachers recognize that they can count on these resources. In school environments, the existence of a collaborative support network can make classroom teaching less challenging if teachers have the support of professionals within their institution, such as management, specialist teachers, other staff, or experiences of co-teaching (Capellini and Zerbato, 2019; Vilaronga et al., 2016).

The results found corroborate previous studies indicating that the unavailability of resources is a barrier to meeting the diversity of students with SEN (Santos et al., 2014; Santos and Capellini, 2021). Santos and Capellini (2021) concluded that schools face a shortage of material and adapted resources, particularly in general education classrooms, to adequately meet the needs of all students.

Brazilian teachers pointed out that computer labs are insufficient to serve all students. Portuguese teachers also indicated a lack of specific resources for students to access the curriculum. These data are consistent with the annual School Census in Brazil. Data from the latest year show continued difficulties in students' access to and use of computers and the internet (Brasil, 2025). The mean availability of desktop computers is 53.5% across Brazilian regions, while internet availability is 51.8%. In the Southeast region, where the participating teachers of this study were concentrated, these figures were above the national average (63.5 and 65.7%, respectively), though still insufficient.

As Santos et al. (2014) argue, students with specific needs may require a series of curricular adaptations for which regular education teachers should be prepared, making the collaboration of other educational agents, particularly special education teachers, necessary for the student to access the curriculum. In this sense, teamwork is highlighted as an alternative to ensure inclusive practices (Santos et al., 2014; Vilaronga et al., 2016).

Another important analysis was to determine what can influence the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices. Among Portuguese teachers, those who work directly with students under additional measures perceived their inclusive practices more positively. It was also observed that teachers who perceived better resources reported better practices, probably due to requiring more support because of the diversity of the population under their responsibility. These results corroborate those found by Dias and Cadime (2018), indicating that the implementation of inclusive practices is related to the perception of support and prior use of inclusive practices.

For Brazilian teachers, the perception of available inclusive resources and inclusive practices was also considered as the outcome. Among the independent variables analyzed (gender, age, length of experience, number of students with a diagnosis, participation in Special and Inclusive Education courses, weekly hours worked, and students' diagnoses—ASD, ASD + other conditions, and others), years of experience correlated negatively and moderately with available inclusive resources, meaning that the more experience, the lower the perception of these resources. These data corroborate the findings of Ferreira (2023), in which teachers with less experience reported a better perception of inclusive resources.

The number of students with a diagnosis correlated positively with better perception of available resources and with better practices. However, having students with ASD and other conditions correlated negatively with the perception of available resources, meaning that teachers working with students with different conditions, including ASD, perceive resources as poorer. Resource scarcity can be both human, when teachers need support from other professionals, such as the Specialized Educational Assistance service within the school, an assistant teacher, or caregiver, and material, related to specific learning materials to support and meet the singularities of students for learning (Camargo et al., 2020).

Thus, the data may indicate that having a student with ASD makes teachers more aware of the importance of resources that could aid their practice and facilitate student participation in the proposed activities. However, Camargo et al. (2020) highlight that teachers often rely only on materials available in schools, such as modeling clay, paints, matching games, puzzles, letters and numbers made out of foam sheets, cut-outs, and other activities deemed appropriate for working with children with autism in the classroom, often disregarding activities proposed for other students.

Training in Inclusive Education correlated positively with educational practices, corroborating literature data indicating that teachers with training in special and inclusive education feel more prepared for their work (Camargo et al., 2020; Favoretto and Lamônica, 2014). Teachers need to acquire knowledge of alternative practices to implement them with their students and share the results with their peers. Continuing education is important, considering the singularities of students with SEN, creating favorable conditions for learning and development for all students (Camargo et al., 2020; Favoretto and Lamônica, 2014; Nascimento et al., 2017; Schmidt et al., 2016).

6 Final considerations

The present study showed that inclusive education still requires adjustments regarding the availability of resources and support for teachers who have students who need them, both in Brazil and in Portugal, a finding that has been consistently reported in the literature from both countries. It was observed, however, in the present study, Portuguese teachers reported greater access to these resources compared to Brazilian teachers, although teachers in both groups considered them insufficient to meet their pedagogical demands and the their students' needs.

One relevant piece of data obtained relates to teachers' perception of their own practices. They consider them inclusive, holding beliefs favorable to the inclusion of all students and report using inclusive practices. However, these data were obtained through self-report. Other data collection methods, such as field observations or focus groups on the topic, could help confirm these findings.

In addition to the small number of participants, another limitation of the study was that in both countries, data collection it occurred in specific regions, in the city of Porto and in the State of São Paulo, this makes it impossible to generalize the findings to the entire population of each country. The instrument used proved to be suitable and, in future analyses, may allow for greater detail, such as identifying the type of resources needed or which practices need to be improved require improvement, contributing to the planning of actions to promote more inclusive education.

Future research could conduct investigations with larger and more representative samples of teachers, from different regions of each country and from varied socioeconomic contexts. Another suggestion would be the use of mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative), combining data from questionnaires and observations in the classroom and in focus groups to validate and enrich the data obtained through self-reporting.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP) Faculty of Sciences, under opinion number 6.871.899 (CAAE: 79401624.3.0000.5398) and by the Municipal Education Departments of the municipalities of São Paulo, Brazil. In Portugal, the research received favorable approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto with Refa 2025-06-01b. Also, authorization was requested from the School Grouping Directorate, in accordance with the required ethical procedures. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SV: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was financed, in part, by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil. Process Number 2025/12983-6, and the Research Deans Office of the São Paulo State University Júlio de Mesquita Filho - UNESP (PROPG/PROPe Notice 06/2024); from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq); from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) (Funding code 001) and from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), grant UID/PSI/000050/2013 for the Psychology Center of the University of Porto (CPUP).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ASD, autismo spectrum disorder; RPEI, Recursos e Práticas para a Educação Inclusiva; UDL, universal design for learning.

References

Abreu, D., and Grande, C. (2021). A caminhar para uma escola inclusiva em Portugal: os desafios sentidos pelos profissionais dos contextos educativos. Revista Educação Especial 35:e20. doi: 10.5902/1984686X47438

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Policy 6, 7–16. doi: 10.1080/20020201729587.

Alcaraz, S., Caballero, C. M., and Arnaiz-Sánchez, P. (2024). Inclusion and the availability of educational resources—capturing stakeholder voices. Educ. Res. 66, 263–278. doi: 10.1080/00132024.2347977

Alves, I. (2019). International inspiration and national aspirations: inclusive education in Portugal. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 23, 862–875. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1624846

Alves, I., Pinto, P. C., and Pinto, T. J. (2020). Developing inclusive education in Portugal: evidence and challenges. Prospects 49, 281–296. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09504-y

Araújo, D. P., Lopes Sobrinho, O. P., Pereira, A. I. S., Coelho, B. A. F. J., and Almeida, G. A. (2023). A acessibilidade arquitetônica em escolas do interior do Maranhão: um estudo de caso. Boletim De Conjuntura (BOCA) 16, 641–660. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10251841

Arnaiz-Sánchez, P., Jurado, V., Caballero, C. M., and Alcaraz, S. (2023). Estudio sobre el uso inclusivo de recursos en educación primaria desde la perspectiva del profesorado. Publicaciones 53, 297–316. doi: 10.30827/publicaciones.v53i3.26378

Azorín, C., and Ainscow, M. (2020). Guiding schools on their journey towards inclusion. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 24, 58–76. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1450900

Azorín, C., Ainscow, M., Arnaiz, P. Y., and Goldrick, S. (2019). A tool for teacher reflection on the response to diversity in schools. Profesorado Revista Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 23, 11–36. doi: 10.30827/profesorado.v23i1.9142

Brasil (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília: Centro Gráfico do Senado Federal. Available online at: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/ConstituicaoCompilado.htm (Accessed August 15, 2025).

Brasil (2008). Ministério da Educação. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP. Available online at: https://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/politica.pdf (Accessed July 28, 2025).

Brasil (2009). Ministério da Educção. Resolução n° 4, de 2 de outubro de 2009. Institui Diretrizes Operacionais para o Atendimento Educacional Especializado na Educação Básica, modalidade Educação Especial. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP. Available online at: https://portal.mec.gov.br/dmdocuments/rceb004_09.pdf (Accessed October 22, 2025).

Brasil (2023). Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo da Educação Básica 2022: Notas estatísticas. Brasília, DF: INEP.

Brasil (2025). Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo da Educação Básica 2024: Notas estatísticas. Brasília, DF: INEP.

Camargo, S. P. H., Silva, G. L. D., Crespo, R. O., Oliveira, C. R. D., and Magalhães, S. L. (2020). Desafios no processo de escolarização de crianças com autismo no contexto inclusivo: diretrizes para formação continuada na perspectiva dos professores. Educação em Revista 36:e214220. doi: 10.1590/0102-4698214220

Campos, E. R. T., Rodrigues, H. G., Macedo, H. G. O., Sá, A. C. C., Oliveira, F. M., Beirão, E. S., et al. (2019). Educação inclusiva: um estudo sobre a percepção dos professores de uma escola em Espinosa - MG. Revista Cerrados (Unimontes) 17, 69–81. doi: 10.22238/rc24482692201917017085

Capellini, V. L. M. F. (2018). Avaliação da qualidade da educação ofertada aos alunos público alvo da Educação Especial em escolas públicas da Comarca de Bauru. São Paulo, Brazil: Projeto de Pesquisa, Universidade Estadual Paulista.

Carvalho, M., Azevedo, H., Vale, C., and Fonseca, H. (2019). “Diversity, inclusion, and education: challenges in perspective,” in Proceedings of the EDULEARN19, Palma (Palma, Spain: IATED). doi: 10.21125/edulearn.2019.2003

Carvalho, M., Cruz, J., Azevedo, H., and Fonseca, H. (2022). Measuring inclusive education in portuguese schools: adaption and validation of a questionnaire. Front. Educ. 7:812013. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.812013

Carvalho, M., Pinatella, D., Azevedo, H., and Alcocer, A. (2024). Inclusive education in Portugal: exploring sentiments, concerns and attitudes of teachers. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 24, 729–741. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12663

Coutinho, M. C., and Tessaro, M. (2024). Percepção de professores acerca do processo de inclusão de alunos neurodivergentes. Revista Pedagógica 26:e7871. doi: 10.22196/rp.v26i1.7871

Cruz, J., Azevedo, H., Carvalho, M., and Fonseca, H. (2023). From policies to practices: factors related to the use of inclusive practices in Portugal. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 13, 2238–2250. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe13100158

Dias, P. C. A., and Cadime, I. M. D. (2018). Percepções dos educadores sobre a inclusão na educação pré-escolar: o papel da experiência e das habilitações. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação 26, 91–111. doi: 10.1590/s0104-40362018002600962

Direção Geral das Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência (DGEEC) (2011). Necessidades especiais de educação, 2010/2011 [Special education needs, 2010/2011]. Lisboa: DGEEC.

Direção Geral das Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência (DGEEC) (2018). Necessidades especiais de educação, 2017/2018 [Special education needs, 2017/2018]. Lisboa: DGEEC.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018). Promoting Common Values and Inclusive Education: Reflections and Messages. European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education: Odense, Denmark.

Favoretto, N., and Lamônica, C. D, A, C. (2014). Conhecimento de professores sobre Transtornos do Espectro Autístico. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial 20, 103–116. doi: 10.1590/S1413-65382014000100008

Feitosa, D. C., and Araújo Filho, G. M. (2023). (2023). Percepção e dificuldades das professoras acerca da sala de recurso utilizada no aprendizado de crianças com deficiência. EDUCERE - Revista da Educação da UNIPAR 23, 610–625. doi: 10.25110/educere.v23i2.2023-006

Ferreira, A. P. (2023). Avaliação e prática pedagógica inclusiva: percepções dos professores da Rede Municipal de Educação de Iporá-GO. [dissertação/dissertação de mestrado Master's dissertation]. [Luiziânia (GO)]: Universidade Estadual de Goiás.

Finkelstein, S., Sharma, U., and Furlonger, B. (2021). The inclusive practices of classroom teachers: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 735–762. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1572232

Gallardo, I. M., San Nicolás, M. B., and Cores, A. (2019). Visiones del profesorado de primaria sobre materiales didácticos digitales. Campus Virtuales 8, 47–62. Available online at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7151664 (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Gitschthaler, M., Kast, J., Corazza, R., and Schwab, S. (2021). “Resources for inclusive education in Austria: an insight into the perception of teachers,” in Resourcing Inclusive Education, eds. J. Goldan, J. Lambrecht, and T. Loreman (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 67–88. doi: 10.1108/S1479-363620210000015007

Goldan, J., Hoffmann, L., and Schwab, S. (2021). “A matter of resources students academic self-concept, social inclusion and school well-being in inclusive education,” in Resourcing Inclusive Education, eds. J. Goldan, J. Lambrecht, and T. Loreman (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 89–100. doi: 10.1108/S1479-363620210000015008

Goldan, J. A., and Schwab, S. (2020). “Measuring students' and teachers' perceptions of resources in inclusive education - validation of a newly developed instrument.” Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 1326–1339. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1515270

Hernández-Torrano, D., Somerton, M., and Helmer, J. (2022). Mapping research on inclusive education since salamanca statement: a bibliometric review of the literature over 25 years. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 893–912. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1747555

Kerr, K., and Ainscow, M. (2022). Promoting equity in market-driven education systems: lessons from England. Educ. Sci. 12:495. doi: 10.3390/educsci12070495

Krischler, M., Powell, J. J. W., and Pit-Ten Cate, I. M. (2019). What is meant by inclusion? On the effects of different definitions on attitudes toward inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 632–648. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1580837

López-Azuaga, R., and Riveiro, J. (2018). Perceptions of inclusive education in schools delivering teaching through learning communities and service-learning. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1507049

Machado, A. B. T. (2024). Desafios na implementação da Educação Inclusiva na escola básica Poeta Manuel da Silva Gaio. [dissertação/dissertação de mestrado Master's dissertation]. [Coimbra, Portugal (PT)]: Universidade de Coimbra.

Martins, M. T. N., Silva, A. J., Amorim, A. H. R., Gomes, D. O. S., Sousa, G. P., Simiao, J. A. G. C., et al. (2025). Práticas pedagógicas inclusivas: estratégias para atender a diversidade. Revista Aracê 7, 5084–5102. doi: 10.56238/arev7n2-033

Menino-Mencia, G. F., Balancieri, M. F., Santos, M. P., and Capellini, V. L. M. F. (2019). Escola inclusiva: uma iniciativa compartilhada entre pais, alunos e equipe escolar. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional 23:e191819. doi: 10.1590/2175-35392019011819

Ministério da Educação e Cultura (MEC) (2014). Orientação aos documentos comprobatórios de alunos com deficiência, transtornos globais do desenvolvimento e altas habilidades/superdotação no Censo Escolar. (Nota técnica no 4/2014/MEC/SECADI/DPEE). Ministério da Educação e Cultura. Available online at: https://iparadigma.org.br/biblioteca/educacao-inclusiva-nota-tecnica-no-04-de-2014-secadi-orientacao-quanto-a-documentos-comprobatorios-de-alunos-com-deficiencia/ (Accessed July 26, 2025).

Mitchell, D. (2005). “Sixteen propositions on the contexts of inclusive education,” in Contextualizing Inclusive Education: Evaluating Old and New International Perspectives, ed. D. Michell (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge), 1–21.

Nascimento, F. F., Cruz, M. M., and Braun, P. (2017). Escolarização de pessoas com Transtorno do Espectro do Autismo a partir da análise da produção científica disponível na Scielo-Brasil (2005–2015). Arquivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas 24, 1–26. doi: 10.14507/epaa.24.2515

Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Económico (OCDE) (2022). Review of Inclusive Education in Portugal, Reviews of National Policies for Education. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/a9c95902-en

Pather, S. (2007). Demystifying inclusion: implications for sustainable inclusive practice. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 11, 627–643. doi: 10.1080/13603110600790373

Pereira, F., Crespo, A., Trindade, A. R., Cosme, A., Croca, F., Breira, G., et al. (2018). Para uma Educação Inclusiva: Manual de apoio à prática. Ministério da Educação: Direção Geral de Educação. Available online at: https://www.dge.mec.pt/noticias/para-uma-educacao-inclusiva-manual-de-apoio-pratica (Accessed July 30, 2025).

Pinheiro Filho, I. S., Paiva, C. D. C., Neves, A. L. M. S., Sousa, M. A. M. A., Jeckel, L. G. B. C., Xavier, F. J., et al. (2024). Práticas pedagógicas inclusivas no contexto brasileiro: desafios e perspectivas futuras. Caderno Pedagógico 21:e8936. doi: 10.54033/cadpedv21n10-112

Portugal (1986). Lei no 46/86, de 14 de outubro. Lei de Bases do Sistema Educativo. Available online at: https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=1744andtabela=leis (Accessed November 5, 2025).

Portugal (2018). Decreto-lei 55/2018 da Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. Diário da República: I série, no 129. Available online at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/55-2018-115652962 (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Rocha, E. S., Silva, H. A., Carvalho, O., Galinha, S., and Machado, C. (2018). “Perceções dos docentes sobre inclusão na educação: um estudo no Norte, Centro e Sul de Portugal,” in Bem-estar, Educação e Direitos da Criança. Coleção CO3 Co-Construir Comunidades, Vol. I, ed. S. A. Galinha (Santarém: JOIA1), 127–149.

Saloviita, T. (2020). Attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education in Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 64, 270–282. doi: 10.1080/00320181541819.

Santos, A. F., Correia, L. M., and Cruz-Santos, A. (2014). Percepção de professores face à educação de alunos com necessidades educativas especiais: um estudo no norte de Portugal. Revista Educação Especial 27, 11–26. doi: 10.5902/1984686X9013

Santos, C. E. M. (2019). Da infraestrutura física às práticas pedagógicas: desafios da escola frente ao aluno público-alvo da Educação Especial. [dissertação/dissertação de mestrado Master's dissertation]. [Bauru (SP)]: [Universidade Estadual Paulista, Bauru, SP.

Santos, C. E. M., and Capellini, V. L. M. F. (2021). Inclusão Escolar e Infraestrutura Física de Escolas de Ensino Fundamental. Cadernos de Pesquisa 51:e07167. doi: 10.1590/198053147167

Santos, G. C. S., Oliveira-Neta, A. S., and Anache, A. A. (2023). Políticas de Educação Especial no Brasil: ameaças, contradições e descontinuidades. Série-Estudos 28, 11–34. doi: 10.20435/serieestudos.v28i62.1759

Santos, K. S., and Mendes, E. G. (2021). Ensinar a todos e a cada um em escolas inclusivas: a abordagem do ensino diferenciado. Revista Teias 22, 40–50. doi: 10.12957/teias.2021.57138

Schmidt, C., Nunes, D. R. P., Pereira, D. M., Oliveira, V. F., Nuernberg, A. H., Kubaski, C., et al. (2016). Inclusão escolar e autismo: uma análise da percepção docente e práticas pedagógicas. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática Psicol. teor. Prát 18, 222–235. doi: 10.15348/1980-6906/psicologia.v18n1p222-235

Schneider, K., Klemm, K., Kemper, T., and Goldan, J. (2018). Dritter Bericht Zur Evaluation Des Gesetzes Zur Förderung Kommunaler Aufwendungen Für Die Schulische Inklusion em Nordrhein-Westfalen. Available online at: https://www.wib.uni-wuppertal.de/fileadmin/wib/documents/publications/WIB_EvalInklF%C3%B6G_3_Bericht_20170718_final.pdf (Accessed August 5, 2025).

Schwab, S. (2019). “Inclusive and special education in Europe,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education (Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1230

Schwab, S., and Alnahdi, G. H. (2020). Do they practise what they preach? Factors associated with teachers' use of inclusive teaching practices among in-service teachers. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 20, 321–330. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12492

Schwab, S., Sharma, U., and Hoffmann, L. (2022). How inclusive are the teaching practices of my German, Maths and English teachers? Psychometric properties of a newly developed scale to assess personalisation and differentiation in teaching practices. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 61–76. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1629121

Sebastian-Heredero, E., and Anache, A. A. (2020). A percepção docente sobre conceitos, políticas e práticas inclusivas: um estudo de caso no Brasil. Revista Ibero-Americana dDe Estudos eEm Educação 15, 1018–1037. doi: 10.21723/riaee.v15iesp.1.13514

Sharma, U., and Sokal, L. (2016). Can teachers' self-reported efficacy, concerns, and attitudes toward inclusion scores predict their actual inclusive classroom practices? Aust. J. Spec. Educ. 40, 21–38. doi: 10.1017/jse.2015.14

Sharma, U., Sokal, L., Wang, M., and Loreman, T. (2021). Measuring the use of inclusive practices among pre-service educators: a multinational study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103506. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103506

Silva Filho, D. M. d. a., and Kassar, M. d. e. C. M. (2019). Acessibilidade nas escolas como uma questão de direitos humanos. Revista Educação Especial 32, 1–19. doi: 10.5902/1984686X29387

Silva, L. S., and Szymanski, L. (2020). Crianças e seus diagnósticos no cenário da educação inclusiva: a perspectiva de mães e professoras. Educação e Pesquisa 46:e225328. doi: 10.1590/s1678-4634202046225328

Silveira-Maia, M. (2024). Política de educação inclusiva em Portugal: implicações para a prática dos terapeutas ocupacionais. Cadernos Brasileiros de Terapia Ocupacional 32:e3796. doi: 10.1590/2526-8910.ctoen392337961

Tébar, F. (2018). Autonomía de los centros educativos. Revista de la Asociación de Inspectores de Educación de España 29, 1–26. doi: 10.19052/ruls.vol1.iss76.3

UNESCO (2020). Final Report of the International Forum on Inclusion and Equity in Education - Every Learner Matters. Paris: UNESCO.

Valenzuela, B. A., de los Ángeles, C. A. R, and Lúgigo, M. G. (2014). Recursos para la inclusión educativa en el contexto de educación primaria. Infancias Imágenes 13, 64–75. doi: 10.14483/udistrital.jour.infimg.2.a06

Vilaronga, C. A. R., Mendes, E. G., and Zerbato, A. P. (2016). O trabalho em colaboração para apoio da inclusão escolar: da teoria à prática docente. Interfaces da Educação 7, 66–87. doi: 10.26514/inter.v7i19.1029

Vrǎşmaş, E. (2018). For a pedagogy of inclusion. a brief overview of the current research on inclusive education. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov 11, 31–44. Available online at: https://webbut.unitbv.ro/index.php/Series_VII/article/view/2580 (Accessed August 8, 2025).

Keywords: inclusive resources, inclusive practices, basic education, children with special needs, perception, teachers, school inclusion

Citation: Rodrigues OMPR, Santos CEM, Vieira SMVdS, Grande C and Alves D (2026) Available resources and inclusive practices for students with special educational needs: perceptions of Brazilian and Portuguese teachers. Front. Educ. 10:1707006. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1707006

Received: 16 September 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025;

Published: 12 January 2026.

Edited by:

Vitor Franco, University of Evora, PortugalReviewed by:

Raquel Oliveira, University of Coimbra, PortugalEduardo Manzini, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Copyright © 2026 Rodrigues, Santos, Vieira, Grande and Alves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olga Maria Piazentin Rolim Rodrigues, b2xnYS5yb2xpbUB1bmVzcC5icg==

Olga Maria Piazentin Rolim Rodrigues

Olga Maria Piazentin Rolim Rodrigues Camila Elidia Messias dos Santos

Camila Elidia Messias dos Santos Susana Maria Veiga de Sousa Vieira

Susana Maria Veiga de Sousa Vieira Catarina Grande

Catarina Grande Diana Alves

Diana Alves