- Agricultural Leadership, Education, and Communications, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

Introduction: Academic misconduct surged during the COVID-19 pandemic as online learning expanded. Understanding factors influencing cheating behaviors is critical for promoting integrity in higher education.

Methods: A correlational study was conducted with stratified random samples of undergraduate students (N = 78) at a large U.S. university during Fall 2021. Data were collected via an online survey using validated scales for ethical sensitivity (ESSQ) and integrity perceptions, along with questions on honor code adherence, unauthorized resource use, and demographics. Binary logistic regression identified predictors of cheating in online courses.

Results: Students reported high ethical sensitivity and strong endorsement of the honor code but low willingness to report violations. Two ESSQ domains—preventing social bias and identifying consequences—were inversely associated with cheating likelihood (p <.05). Belief in the honor code significantly reduced odds of cheating (OR = 0.36, p =.03), while using unauthorized sources for online quizzes increased odds nearly sixfold (OR = 5.92, p =.05). Peer behavior strongly influenced cheating likelihood. No significant relationships were found with gender or class status.

Discussion: Findings reveal a gap between students’ stated values and behaviors, highlighting the role of peer norms and unauthorized resources in academic dishonesty. Interventions should emphasize ethical decision-making, peer-led mentoring, and practical applications of honor codes to foster integrity. Implications: Universities should move beyond punitive measures toward restorative approaches that strengthen ethical culture and address emerging challenges such as AI-assisted cheating.

1 Introduction

Texas A&M University has six core values (i.e., respect, excellence, leadership, loyalty, integrity and selfless service) that unify current and former students, faculty and staff (Purpose & Values | Texas A&M University, 2021). These core values help define the university’s culture and create expectations for students, faculty, and staff to live through word and deed. Texas A&M University students are introduced to the Aggie Honor Code through orientation programs, which is required to be included in every course syllabus, and through pledges to uphold the code to safeguard Texas A&M University’s core value of integrity. Integrity is essential to members’ civic development. In the context of academic conduct, integrity encompasses the other core values. Texas A&M University believes students should actively participate in administering academic policies to uphold the university’s reputation of promoting integrity among its members.

Increased use of online classes and online cheating occurred during the novel coronavirus of 2019, a.k.a., COVID-19 pandemic. Nationwide, universities faced more academic misconduct from increased numbers of online classes (Eaton, 2020; Jenkins et al., 2023; Lancaster and Cotarlan, 2021). Texas A&M University was not exempt from online cheating, experiencing a 20% increase in cheating allegations during the fall 2020 semester (McGee, 2020). Some students self-reported instances of academic misconduct; however, it remains unknown if misconduct was related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bretag et al. (2013) defined academic integrity as “the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility in learning, teaching and research” (p. 6). Students must demonstrate integrity in their academic and social lives. Before a student can graduate and receive a degree, they should be assessed as having good character and academic standing. Guerrero-Dib et al. (2020) postulated that academic dishonesty and unethical behavior, such as cheating and plagiarism, occur in academic settings, particularly among undergraduate students, and that these behaviors may be carried over into their social and professional lives.

Strong personal ethical standards typically encourage moral and responsible behavior, but Guerrero-Dib et al. (2020) contend they can lead to corruption in some situations, if individuals prioritize their moral codes over established legal and ethical norms of their organizations or society. Many corrupt practices, such as bribery/or accepting kickbacks, favoritism, nepotism, abuse of power, misuse of funds, bypassing standard procedures, and manipulating information for personal gain, often go unaccounted. However, after studying data from 40 countries, such as Australia, Brazil, and China, Orosz et al. (2018) reported a relationship between academic dishonesty and level of corruption. Guerrero-Dib et al. (2020) emphasized that mastering technical, practical, and theoretical skills is not enough to succeed after the university experience; personal integrity and ethical behavior, which embody the core values of university ethical efforts, are also essential. Based on the evidence, we hypothesized that self-perceived ethical sensitivities were significantly inversely related to the likelihood of cheating in online courses. Those with low ethical sensitivity scores would report higher likelihood of cheating in online courses and vice versa.

McCabe et al. (1999) noted that honor codes influenced moral norms by making students responsible for identifying violators of such codes in their universities. When most students ascribe moral norms, they become responsible for protecting university values and reputation (Schwartz, 1968), which may be interpreted as protecting their personal values and reputations. McCabe and Pavela (2004) noted that modified honor codes gained traction in the early 2000s as they were found to reduce cheating in universities compared to those that did not have such codes. Modified honor codes involve students in the enforcement process, offering flexible sanctions with a focus on supporting a student’s educational growth, rather than punishment. Modified codes encourage students to bear the responsibility for upholding the code for themselves and peers. Core values promote a standard of behavior upheld by an institution. Gilman (2005) stated, “First, codes of ethics increase the probability that people will behave in certain ways. They do this partially by focusing on the character of their actions and partly by focusing on sanctions for violations” (p. 8).

Tatum (2022) echoed these sentiments following a review of the last 30 years of research on honor codes. She found that research has consistently shown honor codes serve a purpose as an effective tool by educating students on expectations for academic integrity, creating social and cultural norms, encouraging students to take personal responsibility and consider their moral compass, and by acting as repeated reminders to students of what is expected of them through elements like pledges and practices. Through these codes, students demonstrated clarity of what constituted misconduct and created peer influence to act accordingly.

Beyond establishing expectations of responsible behavior, universities use honor codes and pledges to discourage misbehavior too. McCabe and Trevino (1993) suggested that by defining cheating behavior, honor codes may lead to less academic dishonesty. Discouraging misbehavior is reiterated by Mayo (2010), who suggested a primary reason for honor codes is to dissuade cheating, noting that “Honor codes explain the practices that are not tolerated and encourage students to police themselves and their peers” (para. 2). Students understand what is expected of them and others when an honor code, pledge, or set of values exists in academia. Texas A&M University should be concerned about protecting and promulgating its core values. Doing so helps students and others develop positive, productive actions, behaviors, and values for life beyond the university.

Texas A&M University’s student code of honor states, “An Aggie does not lie, cheat or steal or tolerate those who do” (Student Rules | Texas A&M University, 2021). The student honor code, or pledge, was established to create a high code of ethics for all Texas A&M University men and women (Purpose & Values | Texas A&M University, 2021). As a modified honor code, Texas A&M University created an ideology wherein Aggies (i.e., students, faculty, and staff) would never lie, cheat, steal or tolerate those who do. Texas A&M University reflects this idealism through its student rules, in that “For most, living under this code will be no problem, as it asks nothing of a person that is beyond reason. It only calls for honesty and integrity, characters that Aggies have always exemplified” (Purpose & Values | Texas A&M University, 2021) (para. 2). As a result, Texas A&M University instituted rules for its students, faculty, and staff; one is that Texas A&M University instructors are required to include the honor pledge statement on their syllabi. While the code of honor is a set of ethical standards that should guide students in their academic pursuits, there is a system office dedicated to educating students, faculty, and staff as well as responding to academic misconduct and facilitating remediation efforts when students are found to violate the honor pledge. As is typical in modified honor codes, students make up the disciplinary panel, determining outcomes and sanctions for peers who are brought before the honor council by faculty, staff, or other students. Students who fail to uphold the honor pledge face consequences ranging from a grade reduction in the course, receiving a 0 on the assignment, being placed on honor violation probation to even being suspended or expelled from the university.

Although Texas A&M University adheres to its standard of integrity, not all students upheld the honor pledge. The Director of the Honor System Office (AHSO) overseeing potential honor code violations noted “…from Aug. 21, 2019, to Aug. 20, 2020, his office (AHSO) recorded 621 instances of academic misconduct. Meanwhile, from Aug. 20, 2020, to the present (May 31, 2021), the office AHSO recorded 1,330 cases of academic misconduct” (Henton, 2021). Ideally, all students should adhere to an honor pledge. However, recurring violations require Texas A&M University to question its core values, at least that of integrity. Zerbe and Paulhus (1987) defined Socially Desirable Responding as the potential an individual may present themselves in a socially positive manner based on current norms and standards. They identified two distinct components of this theory. In the first, self-deception, a person may unknowingly have blind spots to their character defects, thinking more highly of themselves than would be congruent with their behavior. In the second component, impression management, a person may intentionally attempt to deceive others in order to represent oneself in the most positive light. Perceived ethical sensitivities affect views about integrity; therefore, we hypothesized that self-perceived integrity differed (−/+) in relationship to the likelihood of cheating in online courses. Those with low integrity scores would report higher likelihood of cheating in online courses.

Academic misconduct can harm a university’s reputation of integrity; some who commit academic misconduct might continue such behavior beyond the university. Hollman et al. (2021) found that business students were more likely to adopt unethical behavior tactics to get ahead in their careers after graduation. Increased misconduct in academia could cause grave consequences in the workforce and cost trillions of dollars. Davidson (2021) reported, “The head of the IRS calculated that tax evasion in the U. S. may total $1 trillion a year, a figure that is multiples higher than previous estimates from the federal government” (para. 1). Other unethical practices endanger society. Walker (2021) reported, “For over a month, crews worked to recover survivors and then the dead from the collapsed Champlain Towers South in Surfside, Florida. The 98th and final victim was identified only 2 weeks ago” (para. 1). Some individuals’ misconduct, such as ignoring multiple violations in building codes, contributed to the complex collapse (Blaskey et al., 2021) (para. 9). Violating building codes during construction is unethical, begging the question, “Does professional misconduct originate in a collegiate environment?” In the context of Texas A&M University, if students believe in and uphold the student honor pledge, would they compromise their integrity by cheating in online courses? Would they allow their peers to cheat, if they knew, and not report them for violating the student honor pledge?

The prevalence of online classes (because of the COVID-19 pandemic) ushered in an increased wave of academic misconduct (Henton, 2021). After conducting a systematic review of 52 articles on cheating from 2017 to 2021, Surahman and Wang (2022) identified three factors that contributed to cheating: (1) the individual, because of lack of interest in learning and/or low intellectual ability, (2) the situation, through peer pressure, academic pressure, and ease of cheating, and (3) through sociocultural norms, where cheating was tolerated and/or a lack of understanding of what plagiarism constitutes. Stone (2024) explored the role of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in students’ lives, noting ambiguity around the permitted usage of AI, differing ethical perspectives, peer pressure, and differences in access as contribution factors students face. Perceptions about the likelihood of being caught cheating differed from traditional (face-to-face) settings, in part because of online instructors’ lack of physical presence. Students believed that lack of supervision during exams made it easy to cheat (Reedy et al., 2021). Adzima (2020) found anonymity in online learning was positively correlated with cheating.

Several universities experienced increased academic misconduct resulting from increased student numbers in online classes. The University of North Texas and Texas State University reported increased academic misconduct ranging from 20 to 33% (McGee, 2020). The University of Pennsylvania reported cheating investigations grew 71% during 2019–2020 (Hobbs, 2021). McGee (2020) reported that Texas A&M University students were found using Chegg to gain answers in an online finance class. Chegg was an American education technology company, popular at the time of this study, that provided online student services, including artificial intelligence (AI) tools and resources with a focus on personalized learning experiences. Although Texas A&M University did not explicitly disallow students’ use of Chegg, each course instructor may or may not have authorized it as an allowed source for completing course quizzes, group projects, major exams, and term papers. Therefore, due to this ambiguity based on professors’ preferences, we distinguished differences between authorized and unauthorized online sources used to complete online quizzes, group projects, major exams, and term papers at Texas A&M University. Authorized online resources were explicitly permitted by professors whereas unauthorized online resources were sought by students but not sanctioned by professors. Based on the evidence about use of unauthorized sources, we hypothesized a direct relationship existed between unauthorized source use and the likelihood of cheating in online courses. Those with low unauthorized source use would report lower likelihood of cheating in online courses.

Choice of academic major or profession are not sole indicators of one’s likelihood to cheat; other demographic variables help explain one’s cheating behavior. Yu et al. (2016) found differences in students’ cheating behaviors by gender; females had fewer self-reported incidents of academic cheating. Male students were found more likely than females to cheat (Kobayashi and Fukushima, 2012; Peled et al., 2013). Ghanem and Mozahem (2019) found females cheated less than males. However, Feinberg (2009) found female students cheated with equal frequency to males cheating. Koscielniak and Bojanowska (2019) found significant negative correlations between GPA and students’ cheating behaviors; cheating behaviors decreased when students’ grade point averages increased, which were also found by Ghanem and Mozahem (2019). Among undergraduates, younger students were more prone to cheating than their older peers (Klein et al., 2007; Olafson et al., 2013). Some students are enticed to cheat because of peer pressure (Noorbehbahani et al., 2022; Sarita, 2015; Waltzer and Dahl, 2023). Given the existence of selected academic major, peers, class status, and demographic variables (gender, age), we hypothesized the likelihood of cheating during online courses would be related to selected demographic variables. Conflicting results from previous research prohibits stating directional outcomes of the hypothesis test.

The purpose of this study was to explore university students’ perceptions of academic integrity. The research objectives were to test if (1) students perceived ethical sensitivity was inversely related to their likelihood of cheating in online courses; (2) students’ perceptions of integrity were inversely related to their likelihood of cheating; (3) the likelihood of cheating in online courses was directly related to the use of unauthorized sources in online quizzes, group projects, major exams and/or term papers; (4) the likelihood of cheating in online courses was related to selected demographics.

To evaluate these hypotheses, researchers considered the field of ethical sensitivity. In 1984, Rest proposed four cognitive processes involved in moral behavior: (1) a recognized quandary noting who is involved, possible action choices, and the impact of those choices on each person involved, (2) evaluating which of the choices is the most just or morally right while prioritizing key factors and synthesizing diverse components so that a single moral choice is identified, (3) choosing the moral choice over and above personal needs and goals that serve other purposes, and (4) carrying out the moral action, without wavering, through self-regulation and cognitive choice.

2 Materials and methods

This study was part of a larger project (IRB2021-1065 M). Some of the methods are reported elsewhere (Benitez and Wingenbach, 2025; Okolo et al., 2025) but all are described fully herein. This study was designed and occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic in fall 2021. One shortcoming in survey research is the reliance on self-reported data, which could be biased because of the topic (cheating behavior).

A correlational design was used to conduct this study (Sousa et al., 2007) analyzing relationships between the variables of interest (i.e., students’ ethical sensitivities, likelihood to cheat, and demographics). The population of interest (N = 5,312) was undergraduate students enrolled at Texas A&M University—main campus during the 2021 fall semester. Participants were randomly selected from courses with and without ethics as a course descriptor. Ethics-based courses were included from majors such as engineering, public health, accounting, agriculture, and international politics. Courses without an ethics descriptor were included from those same majors. The population (N = 5,312) was composed of students (first year to senior students) enrolled in one of 16 ethics-based courses (n = 1,918) or in one of 25 non-ethics-based courses (n = 3,394). Thus, we created an ethics-based sampling frame and a non-ethics-based sampling frame. Stratified random samples (n = 100/sample type) were created using Dillman et al.’s (2009) methods to derive probability samples. We calculated samples based on a conservative 50/50 split with a 5% sampling error and 95% confidence level (Dillman et al., 2009). An incentive ($5 e-gift card) was offered to participants who completed the survey. Students redeemed the incentive by exiting the survey on the final question when they were transferred to a third-party vendor (Tango Card Inc.), which disassociated their responses from the incentives.

A personalized invitation and nine reminders were sent through Qualtrics, producing 92 responses (46% response rate), which were reduced to 78 because of partial or incomplete data (i.e., some students opted out of sensitive questions about cheating). Only those completing 50% or more of the questions were included in the data. The final response rate was ~39%. Due to limited response, the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Given the sensitivity of the topic and potential that students who cheated may not be as likely to self-report, even with an anonymous instrument, we used Lindner and Wingenbach’s (2002) method of comparing early to late respondents to determine if nonresponse error affected the data set. Respondents were defined using waves of email reminders. All responses before September 27, 2021, were coded as early (responses from the invitation and first email reminder). Those received on September 27, 2021, or after were coded as late (second through ninth email reminders). Independent samples t-tests were used to test nonresponse error. We compared summed Ethical Sensitivity scores for early (n = 57) vs. late (n = 15) respondents, finding no significant differences (early: M = 92.56, SD = 10.86; late: M = 92.27, SD = 8.83), t(70) = −0.89, p = 0.37. Respondents’ Ethical Sensitivity scores were not affected by respondent type. As such, the results are indicative of nonrespondents and consequently are representative of the target population.

Data were collected using the Core Values research instrument, created from modified versions of the Ethical Sensitivity Scale Questionnaire (ESSQ) (Tirri and Nokelainen, 2007) and integrity questions developed by the researchers. Content and face validity were established through a panel of experts (non-study related university faculty) and a pilot study with 15 students who were not in the research samples. Respondents averaged about 8 min to complete the research instrument. All instrument sections employed attitudinal scales (disagree to agree) or forced response (Yes/No) sets.

Lützén et al. (1995) defined ethical sensitivities as a moral sensitivity to recognizing a moral conflict, having contextual and intuitive understanding of the vulnerabilities related to the situation, and having insight into ethical consequences of how actions affect others. For the present study, ethical sensitivities were measured using the ESSQ (Tirri and Nokelainen, 2007), which was based on Narvaez (2001) operationalization of ethical sensitivity across seven dimensions. Those dimensions measure ethical concepts as: (1) reading and expressing emotions, (2) taking the perspectives of others, (3) caring by connecting to others, (4) working with interpersonal and group differences, (5) preventing social bias, (6) generating interpretations and options, and (7) identifying the consequences of actions and options. Each dimension had four statements (28 statements total) that were measured with five-point scales (1 = totally disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = unsure, 4 = agree, 5 = totally agree). The scale replicates previous studies (Tirri and Nokelainen, 2007; Schutte et al., 2017) to preserve its authenticity in measuring ethical sensitivities as value or moral issue statements.

Our reliability analysis confirmed the previous works of Tirri and Nokelainen (2007) and Schutte et al. (2017). Respondents’ scores were summed for each ESSQ dimension and for the total scale. Some ESSQ items were reverse-coded before they were summed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to determine subscale reliabilities (Taber, 2018). Post-hoc reliability tests revealed acceptable (Taber, 2018) Cronbach’s coefficient alphas (αs = 0.49–0.69) for ESSQ dimensions, which was consistent with previous studies (αs = 0.40–0.78) (Schutte et al., 2014; Tirri and Nokelainen, 2007). As noted elsewhere, alpha values are affected by dimensionality of the scale (Tirri and Nokelainen, 2007; Schutte et al., 2014; Helms et al., 2006) and limited number of items per subscale (Ary et al., 2010).

Students’ integrity was captured by asking students about their perspectives of the Student Code of Honor, specifically concerning the core value of integrity. We asked respondents how much they valued the honor pledge (Scale of 0–10, with “0 = no value” and “10 = full value”); and, how likely they were to report yourself or others for violating the honor pledge. Next, we asked them how much do Texas A&M University faculty respect the honor pledge and how likely would they enforce it in their classes. We also asked about the likelihood (self and others) of using unauthorized sources that constituted cheating in online and face-to-face courses at Texas A&M University. Nine demographic questions (gender, year in school, college, race/ethnicity, political views, religious views, religiosity, socio-economic status, and estimated GPA) were developed based on others’ research (Stankovska et al., 2019; Jantos, 2021; Taşgın, 2018) that showed demographics were related to perceptions of ethical sensitivities and likelihood or motivations to cheat.

Data were collected online (Qualtrics), beginning on September 20, 2021, and concluding on October 22, 2021. Personalized pre-notice emails were sent to all potential respondents 3 days before the study invitation was released.

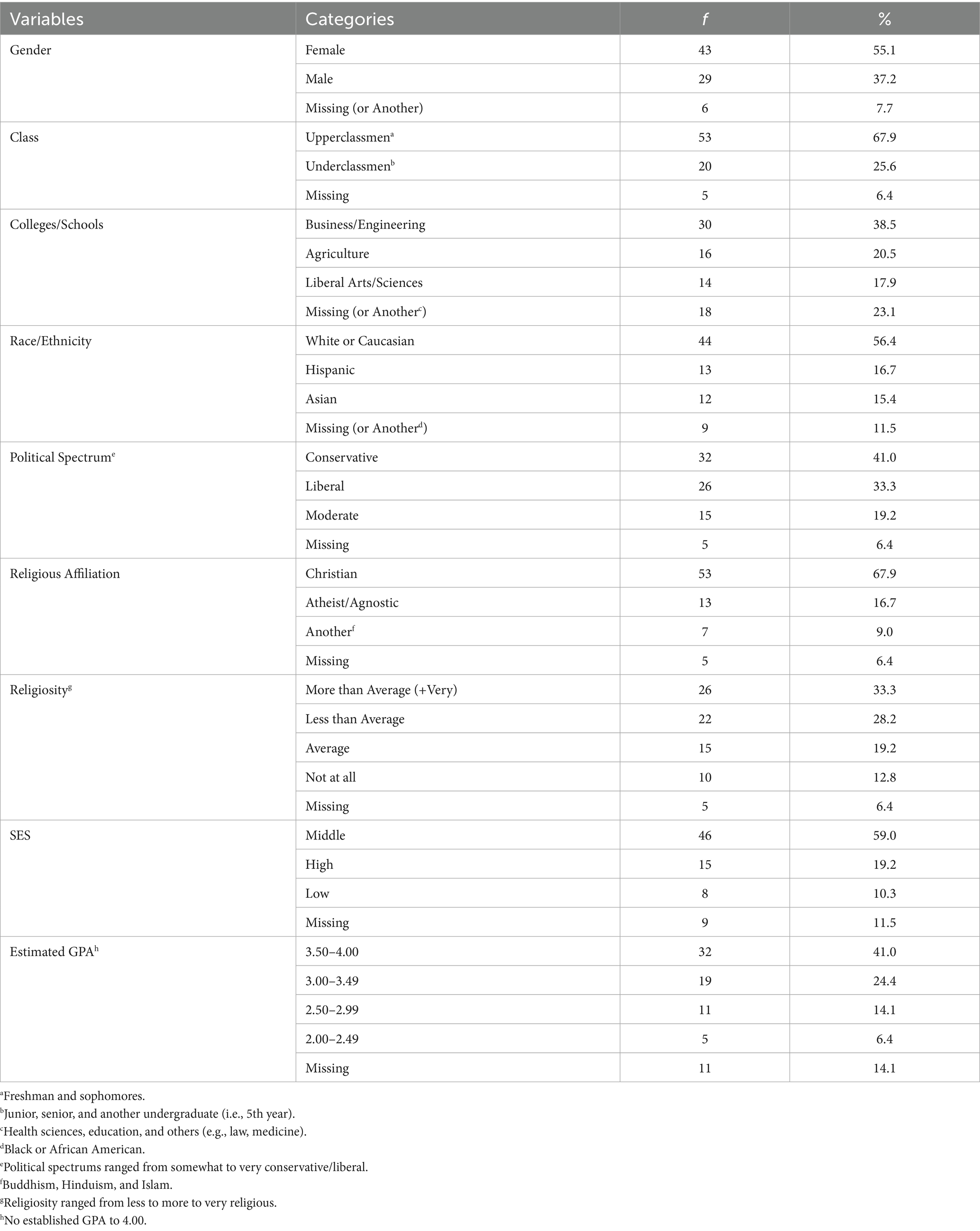

Respondents (N = 78) were characterized as females (55%), white or Caucasian (56%), juniors or seniors (68%), who were studying engineering or business (38%). Respondents self-reported as coming from middle income (59%), conservative (41%), Christian (68%) households with more than average to very religious beliefs (33%). Respondents estimated their grade point average (GPA) of 3.5 to 4.0, indicating an A average (41%) (Table 1).

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to check for outliers, normality, skewness and other basic outputs (Ott and Longnecker, 2015) for respondents’ demographics (Fraenkel et al., 2012). Inferential statistics were used to analyze and report data for higher order analysis. Assumptions were evaluated including normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity. No concerns were noted. The Durbin-Watson test was within normal range (1.5–2.5), thereby indicating no issues with autocorrelation. All statistical tests were conducted with a priori alpha level of 0.05.

Binary logistic regression (Equation 1) was used to determine statistically significant predictor variables, and the proportion of variability explained in the regression model (Ott and Longnecker, 2015). The student’s likelihood to cheat (yes/no) in online courses during COVID served as the dependent variable. The predictor variables were: (1) likelihood friends cheated (yes/no), (2) honor code values (self and others), (3) report code violations (self and others), (4) faculty views’ of honor code (respect and enforce), (5) ESSQ (7 Domains), (6) gender (M/F), (7) class (under/upperclassmen), and (8) use of unauthorized sources to complete graded activities (online quizzes, group projects, major exams, and term papers). The binary logistic regression equation was stated as:

where:

p = Probability of the binary outcome (yes or no), a = Constant, b1X1 = Likelihood friends cheatedFriendsCheat, b2aX2a = Honor code self valueHonorSelf, b2bX2b = Honor code others valueHonorOthers, b3aX3a = Report self violationsReportSelf, b3bX3b = Report others’, violationsReportOthers, b4aX4a = Faculty respect the codeFacultyRepect, b4bX4b = Faculty enforced the codeFacultyEnforce, b5aX5a = ESSQDom1, b5bX5b = ESSQDom2, b5cX5c = ESSQDom3, b5dX5d = ESSQDom4, b5eX5e = ESSQDom5, b5fX5f = ESSQDom6, b5gX5g = ESSQDom7, b6X6 = StudentGender, b7X7 = StudentClass, b8aX8a = SourceQuiz, b8bX8b = SourceProject, b8cX8c = SourceExam, b8dX8d = SourcePaper.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed an excellent fit of the model based on X2 = 2.30, GFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.96, and RMSEA = 0.05. Respondents were informed repeatedly that they could skip any questions that made them uncomfortable.

3 Results

3.1 Perceptions of ethical sensitivities

Objective 1 was to test if students perceived ethical sensitivity, measured by Tirri and Nokelainen’s (2007) ESSQ domains, was inversely related to their likelihood of cheating in online courses. Respondents rated their disagreement or agreement with four statements in each of the seven domains (Table 2). In response to stating one’s needs to others, students disagreed they would tell others when they were offended by them (M = 2.85, SD = 1.18) or to take others’ positions when confronted with conflict (M = 3.09, SD = 1.08). Alternatively, students agreed with being concerned about others (M = 4.51, SD = 0.70), that it is good that their friends think in separate ways (M = 4.35, SD = 0.78), and that they maintain good personal relationships in conflict situations (M = 4.31, SD = 0.63). Of the 28 ESSQ statements, 24 were scored at or above 3.50, suggesting respondents perceived themselves as having ethical sensitivity, according to Tirri and Nokelainen’s (2007) ESSQ (Table 2).

3.1.1 Relationships between ethical sensitivities and the likelihood to cheat in online courses

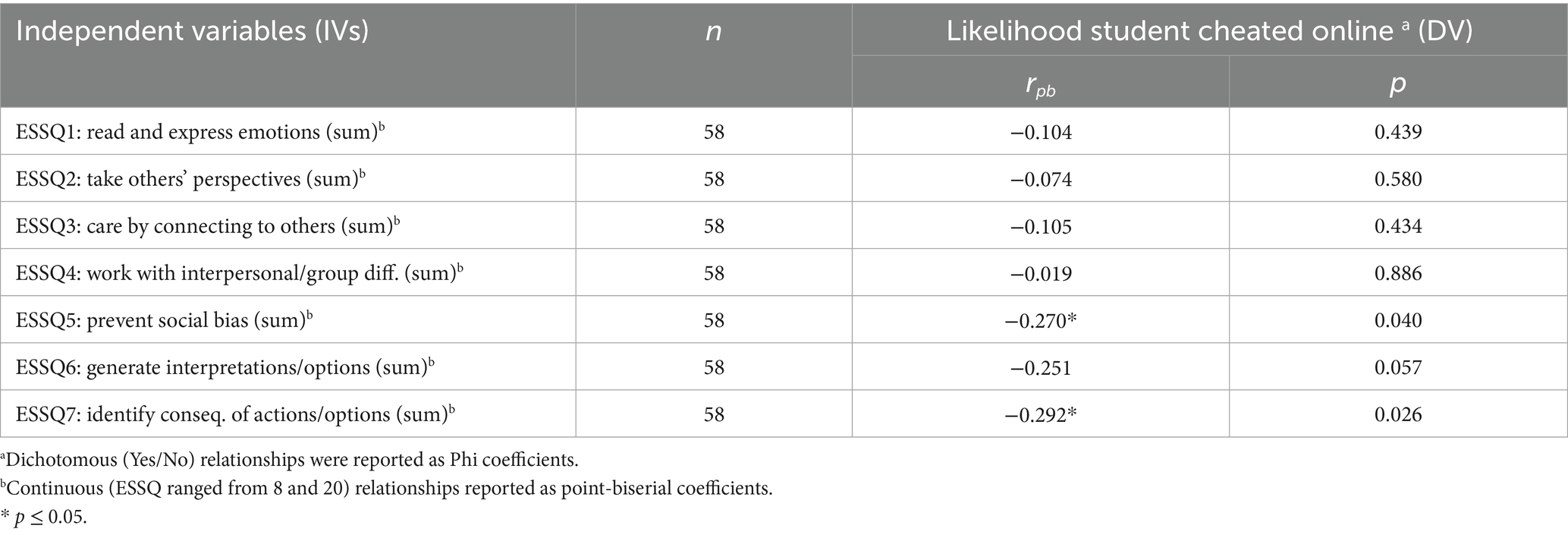

Significant inverse associations existed between ESSQ domains (ESSQ5: ethical sensitivity toward preventing social bias, rpb = −0.270, p = 0.040), (ESSQ7: ethical sensitivity toward identifying the consequences of actions and options, rpb = −0.292, p = 0.026) and likelihood of cheating in online courses (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations between the likelihood of cheating in online courses (DV) and ESSQ domains (IVs).

Based on the evidence (Table 3), we rejected the null hypothesis and partially accepted the alternative as true. The evidence suggested that two ESSQ domains were significantly inversely related to the likelihood of cheating in online courses. Those with low ethical sensitivity scores had a significantly higher likelihood of cheating in online courses. However, the correlation for ESSQ5 was moderate at −0.27 and ESSQ7 at −0.29, suggesting a medium effect size (Cohen, 1988) in both.

3.2 Perceptions of integrity and likelihood to cheat in online or in-person courses

Objective 2 was to test if students’ perceptions (i.e., views of integrity in online and/or face-to-face courses) were inversely related to their likelihood of cheating. Overall, they reported that they upheld and promoted the student honor pledge, which is to not lie, cheat, or steal (M = 8.79, SD = 1.51), or tolerate others who do (M = 7.06, SD = 2.63) (Table 4). On the contrary, they were unwilling to report themselves (M = 4.36, SD = 3.56) or others (M = 4.76, SD = 3.20) for violating the student honor pledge; hence, their behavior was incongruent with their beliefs. They perceived that faculty respected the honor pledge (M = 8.46, SD = 1.90) and would enforce it (M = 8.69, SD = 1.70) in their courses.

3.2.1 Relationships between perceptions of integrity and the likelihood to cheat

Significant associations (positive and negative) existed (Table 5), revealing likely predictor variables such as friends’ likelihood of cheating in online courses during COVID-19 (ϕ = 0.386, p = 0.006); respondent’s belief in the honor pledge (rpb = −0.369, p = 0.004).

Table 5. Correlations between the likelihood of cheating in online courses (DV) and perceptions of integrity (IVs).

Based on the evidence (Table 5), we rejected the null hypothesis and accepted the alternative as true. The evidence suggested that perceptions of integrity were significantly inversely related to the likelihood of cheating in online courses. Those who had high perceptions of the student honor pledge had significantly less likelihood of cheating in online courses. However, perceptions of their peers cheating were significantly positive associated with the likelihood of cheating in online courses.

3.3 Use of unauthorized sources and likelihood to cheat

Objective 3 was to test if students’ use of unauthorized sources (e.g., Chegg) to complete online quizzes, group projects, major exams, and term papers was directly related to their likelihood of cheating. They reported (Table 6) being highly unlikely (M = 1.53, SD = 1.89) to cheat in online courses during COVID-19, and even less likely to use unauthorized sources in face-to-face class assignments (M = 0.73, SD = 1.50). However, respondents reported greater likelihoods that their friends cheated in online courses during COVID-19 (M = 4.43, SD = 3.07) and used unauthorized sources for face-to-face class assignments (M = 1.59, SD = 2.22). The highest reported likelihood of using unauthorized sources for face-to-face course assignments was for group projects (M = 1.43, SD = 2.10), although it was considered a highly unlikely outcome.

3.3.1 Relationships between unauthorized source use and the likelihood to cheat

Significant positive associations existed (Table 7), revealing likely predictor variables such as using unauthorized sources during COVID-19 for online quizzes (ϕ = 0.540, p < 0.001), major exams (ϕ = 0.342, p = 0.011), and term papers (ϕ = 0.383, p = 0.004).

Table 7. Correlations between the likelihood of cheating in online courses (DV) and unauthorized source use (IVs).

Based on the evidence (Table 7), we rejected the null hypothesis and accepted the alternative as true. The evidence suggested using unauthorized sources may have promoted cheating behaviors when completing graded assignments for online quizzes, major exams, and term papers.

3.4 Relationships between the likelihood to cheat in online courses and demographics

To answer Objective 3, we analyzed bivariate correlations between the likelihood of cheating in online courses during COVID-19 (Yes/No) and selected demographic variables (Table 8). No significant associations were found between the likelihood of cheating in online courses and gender or class.

Table 8. Correlations between the likelihood of cheating in online courses (DV) and selected demographic variables (IVs).

Based on the evidence (Table 8), we failed to reject the null hypotheses. The evidence failed to suggest significant relationships existed between the likelihood of cheating in online courses and selected demographic variables.

3.5 Regression analysis of the likelihood of cheating in online courses

From results of the bivariate analyses, we modified the regression equation (Equation 2) to include only statistically significant independent variables that may affect students’ likelihood of cheating in online courses during COVID-19. The modified equation was:

where:

p = Probability of the binary outcome (yes or no), a = Constant, b1X1 = Likelihood friends cheatedFriendsCheat, b2aX2a = Honor code self valueHonorSelf, b5eX5e = ESSQDom5, b5gX5g = ESSQDom7, b8aX8a = SourceQuiz, b8cX8c = SourceExam, b8dX8d = SourcePaper.

A logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of predictor variables (likelihood friends cheated, student values the honor pledge, ethical domains—preventing social bias and identifying the consequences of actions and options—and, using unauthorized sources for online class assignments—quizzes, major exams, and term papers) on the dependent variable (student’s likelihood to cheat in online courses during COVID-19). The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 (7, 50) = 33.61, p < 0.001. The model explained 66% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in student’s likelihood to cheat in online courses during COVID-19 and correctly classified 84% of cases.

A student’s belief in the honor pledge (Table 9) was statistically significant (B = −1.01, Wald = 4.91, p = 0.03, Exp (B) = 0.36, 95% CI [0.15, 0.89]), indicating the more a student believed in the tenets of the pledge, the lower were his/her odds of cheating. Students were 0.36 times less likely to cheat in online courses during COVID-19 if their self-perceived value of the student honor pledge was positive. However, they were 5.92 times more likely to use an unauthorized source to cheat during online quizzes (B = 1.78, Wald = 3.71, p = 0.05, Exp(B) = 5.92, 95% CI [0.97, 36.16]), which may have offset or negated entirely the positive effects of believing in and valuing the student honor pledge. The Nagelkerke R2 revealed a strong model fit (0.66), while the Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (χ2 (8) = 2.71, p = 0.95) indicated a good model fit (i.e., non-significant p-value indicates the model fit the data well).

4 Discussion

We investigated students perceived ethical sensitivities. We found Texas A&M University’s students had high levels of ethical sensitivity, as evidenced by agreement with most ESSQ statements. This is an encouraging outcome because it indicates students were at least aware of ethical considerations and they valued ethical behavior. Students expressed less sensitivity in expressing discomfort when offended and taking others’ perspectives in conflict situations. These findings may indicate a need for interventions focusing on assertiveness and empathy in interpersonal interactions. Future studies should compare ethical sensitivity scores between students in ethics-based and non-ethics-based courses to see if such courses influence students’ ethical awareness and/or attitudes.

We examined students’ perceptions of integrity and their likelihood to cheat during online and/or in-person courses. We found significant discrepancies between self-reported high values of Texas A&M University’s honor pledge, which contradicted their willingness to self-report violations of the honor pledge. Respondents espoused values about ethical sensitivities were incongruent (Stephens, 2017) with their behaviors. We need to further explore students’ reluctance to report honor pledge violations. Social norms and peer pressure influence students’ cheating behaviors. If cheating is an acceptable behavior within one’s social circle, it is more likely an honest student will engage in such behavior too.

Participating in online only classes during the COVID-19 pandemic may have “normalized” or ameliorated (Stephens, 2017) students’ feelings, attitudes, and behaviors about cheating and its relationship to academic dishonesty. Perhaps the pandemic changed some students’ ethical views about cheating and personal guilt associated with it. Shu et al. (2011) posited that people routinely commit dishonest acts without feeling guilty because they were morally disengaged in the act of cheating, accomplished by forgetting moral rules of honest behavior. Thus, some students justified their dishonest deeds vis-a-vis moral disengagement, which is to say they “mentally” closed the gap between ethical standards (morals) and dishonest behaviors, yet the dissonance remains. Helping students resolve it requires educators to creatively address cheating behavior without prompting students’ feelings of shame or guilt; this might be addressed by deploying mechanisms of moral engagement (Stephens, 2017). Shu et al. (2011; as cited in Stephens, 2017) found they could reduce moral disengagement and cheating behavior, in situ, by having participants read and sign an honor pledge. Hence, a simple reminder about honesty, personal responsibilities to not cheat, and moral integrity to uphold social norms can help students rekindle (i.e., moral engagement) innate desires to displace dissonance with consonance.

We sought to determine if relationships existed between ethical sensitivities, perceptions of integrity and the likelihood to cheat and/or select demographics. Although no demographic variables significantly predicted cheating, multiple relationships were shown to exist between likelihood to cheat and predictors of cheating. Additionally, a considerable amount of variance for explaining the predictors of cheating were found in the model. Students who demonstrated ethical sensitivities toward social bias, or prejudice, and identifying consequences to actions and options were correlated with cheating outcomes. Students who indicated friends had cheated online were also significantly related to predicting the likelihood of their own cheating. Not surprisingly, a student’s self-perceived integrity about the honor pledge was significantly and inversely related, lessening the odds of cheating if the honor pledge was valued positively. The significant finding of using unauthorized sources to engage in cheating behavior during online quizzes is concerning. Our findings support earlier works (Adzima, 2020; McGee, 2020), which showed cheating behavior differed in online vs. in-person courses because online courses included anonymity, lack of instructor presence, and use of unauthorized sources in low-stakes cheating behavior.

Intuitively, our results highlight the importance of discussions about ethical behavior among university students. Universities have critical roles in the developmental nexus between adolescence and young adulthood. The university’s orientation program is often a student’s first awareness of the expectations of academic conduct. These initial discussions could be key moments for conversations about integrity; the student honor pledge and the role that peer pressure plays in making ethical decisions should be emphasized during orientation. Furthermore, educators can do more than include the university’s mandatory honor pledge on their syllabi; they can be active promoters of the honor pledge by engaging students in discussion of real-world examples of dishonesty and unethical behavior (Guerrero-Dib et al., 2020; Orosz et al., 2018). Research on integrity and honor pledges (social codes) beyond the classroom may help students examine and refine their moral compasses.

Two of seven dimensions (i.e., skill sets) of ethical sensitivity, “preventing social bias” and “identifying consequences of actions and options,” were identified as significant predictors of cheating behaviors. Preventing social bias is described as the extent to which an individual recognizes, understands, identifies, controls, and actively counters their biases when addressing ethical problems (Schutte et al., 2017; Schutte et al., 2014). Identifying consequences of actions and options describes the extent to which an individual recognizes ethical issues around them. Students who recognized and controlled their social bias and could recognize ethical issues were less likely to cheat. Not all students recognized cheating as an ethical issue, in present or future settings. Some students need help in understanding that cheating is contradictory behavior to building and maintaining one’s ethical status, integrity, moral character, and agreement to uphold the social contracts upon which peaceable communities exist (Schutte et al., 2017). Identifying consequences of actions and options is inherently based on understanding relationships between events and their consequences, positive or negative, in short- and long-term situations. In other words, behavioral actions such as cheating in academia could result in a failed exam or class today but might be associated with breaking laws and anti-social behavior in the future. Educators and universities can instill positive decision-making skills that extend short-term outcomes to long-term consequences through predictive analyses of personal choices (e.g., spending vs. saving money; use vs. misuse of alcohol/tobacco). Given structured practice through role-played ethical problems, students’ identification of consequences was positively associated with higher quality forecasts of the outcomes and more ethical decisions (Shu et al., 2011).

There were some limitations to this study such as reduced generalizability, self-reported data, and the cross-sectional design. While we randomly selected participants, respondents were all from Texas A&M University, which limits our ability to generalize the results to other universities or student populations. We relied on self-reported data. Cheating is a sensitive topic; therefore, it is possible that social desirability bias affected the outcome. Students may have answered questions according to how they believed they should act, not necessarily how they do act. The cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal research to examine long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors influencing academic integrity are needed.

4.1 Limitations

Constraints impacted on the current study, starting with the small sample size. While a larger population was identified at the university, the study was divided into three smaller, related studies, resulting in a smaller sample for this component of the study. The final response rate was ~39%, possibly due to the sensitive nature of the questions, and due to limited response, the results may not be generalizable to other populations. We are not sure why students did not perceive the topic important enough to respond or if the incentive was too low to compensate for their time. More study solely on the topic itself and/or the level of incentive offered is needed. Further, few scales in the ESSQ demonstrated noteworthy effect size. As such, while statistical significance was found at points in the study, the practical application of the ESSQ predicting likelihood of misconduct may not be present. Replicating the study with a larger sample size would help better support the results of this study including whether or not a practical effect size exists.

An additional consideration that may impact a study such as this is the effect of Socially Desirable Responding, as Zerbe and Paulhus (1987) noted that this incongruent behavior in some can distort research results. Researchers suggested using Socially Desirable Responding as an additional variable of interest rather than presuming error, including assessment questions that evaluate this effect. Adding methods for capturing this effect could strengthen this study by explaining the role this effect plays on research of such a sensitive nature.

4.2 Implications

Based on the results, we recommend Texas A&M University engage students in practical applications of upholding the honor pledge through ethical decision-making workshops focused on the core values. Workshops could include increasing students’ awareness of the honor pledge and clarifying how to report honor pledge violations. However, ethical decision-making workshops alone are not enough to inculcate a culture of integrity for all. We believe a culture of integrity at Texas A&M University should not focus on punishing cheaters but rather include interventions that encourage ethical decision-making and emphasize the value of learning, that in a sense, promotes restorative justice (Ellis and Murdoch, 2024) to help students move past their academic misconduct. Interventions should involve student-led initiatives and peer-to-peer mentoring because peers significantly influenced students’ likelihood to cheat.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a shift to more online learning formats, which may have influenced students’ cheating behaviors. There is a possibility the online environment created a perception that cheating was easier and less likely to be detected. Further, students were under increased stress during the pandemic, which could have contributed to cheating behavior. Future research on this topic could explore long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic integrity, using experimental designs to investigate the impact of different interventions to reduce cheating as well as qualitative research to explore students’ perspectives on cheating and honor pledges. Studies could be completed to examine relationships between ethical sensitivity and professional misconduct to empirically validate the importance of ethical behavior in college. Additionally, as this study was limited to one institution, further research could include comparative studies to examine academic integrity across different universities and student populations.

Returning to Surahman and Wang’s (2022) systematic review of cheating, they noted a gap in the research from 2017 to 2021 that appears to have arrived in the present day, the role of generative AI in cheating. While we have seen the use of positive AI, such as plagiarism detection tools, like TurnItIn, take on more prominence in the academic setting, the researchers encouraged deeper studies into the negative aspects of AI. Further, they noted that institutions’ policies should address not only prevention of AI cheating but redesign assessments to reduce opportunities for students to cheat. Stone’s (2024) research found five key factors related to AI: (1) widespread but uneven AI use - while 63% of students used AI in ways that were explicitly allowed, 41% used it in ways that were explicitly banned; (2) ethical ambiguity and peer influence – students who believed peers cheated were more likely to cheat themselves, were more likely to use AI unethically when familiar with AI, and believed output mattered more to employers than using AI; (3) accusations – that some students were falsely accused of using AI, (4) men reported more acceptance of using banned AI, and (5) professors’ role – while professors addressed AI in their syllabus few brought it into the coursework itself; however, when professors did incorporate AI, students were more likely to use it, including banned AI.

4.3 Conclusion

Since this study was conducted, we note a relevant situation that occurred at Texas A&M University during fall 2024. The popular forum Reddit is a place for individuals to post questions and thoughts about subjects. Submitters can create fake names to protect their identities. Submitters freely post their thoughts on all manners of issues. In fall 2024, a post (see Supplementary materials) from a student at Texas A&M University described how the student’s roommate was deliberately cheating in engineering courses by using friends and Artificial Intelligence to complete homework. The Reddit submitter asked if they should report their roommate to the Texas A&M University honor council. More than 200 replies were posted while we finished this manuscript.

Most respondents suggested the roommate should not report the cheating to the honor council, positing that the roommate would eventually “crash and burn,” as college assignments unfolded. A few individuals urged the roommate to report the cheating to avoid being “complicit” in the matter, thereby subjecting the submitter to allegations of cheating too. Based on self-reports, many responders who encouraged the original submitter to report the cheating, also self-identified as older, former students, who were now in the workforce. One person described how they had observed individuals in the workforce who “failed upwards” often, while others stood by and allowed it to happen. This respondent implored the original submitter to report the roommate to the Texas A&M University honor office (Stenmark et al., 2011).

Much evidence exists to support our contention that cheating in school may lead to more serious consequences of unethical behavior outside of academia. For example, structural engineers repeatedly signed off on the construction and on inspection reports of the Champlain Towers South Condominium before it collapsed on 24 June 2021, resulting in 98 deaths (Subreddit, 2024). The U.S. is not alone in experiencing increased engineering failures due to a lack of practical experience and a comprehensive set of ethical norms in engineering practices. Researchers (Alvarez, 2023; Tang and Huang, 2024) found similar results when investigating the collapse of self-built houses in Changsha (Hunan, China) on 29 April 2022. Among the authors’ conclusions, which were consistent with ours, is the need for increased awareness, concern, and application of ethics education, especially in civil engineering (Subreddit, 2024) at the postsecondary level. “Ethics education has become an important measure to improve the moral and ethical standards of engineers” (p. 40), which we believe should be the norm for preparing postsecondary students in all careers. The Reddit poster (Subreddit, 2024) who claimed, “…I just care that the engineers of our society actually know what they are doing, I’m not too concerned with how they acquire that knowledge,” may want to think more deeply about the connections between ethical behavior while studying engineering and the results of unethical civil engineering practices beyond academia.

This is one scenario and one example of cheating beyond the COVID-19 pandemic; nevertheless, cheating still occurs, and some students are unwilling to report it to the Texas A&M University honor office. What then, shall the future hold for Texas A&M University’s ideals about integrity? The current prevalence of AI-generated output, which is nearly impossible to detect, will create an avalanche of academic dishonesty that could bury Texas A&M University’s efforts to uphold its core value of integrity. Academic integrity is in jeopardy. University administrators, educators, and others concerned with honesty in and beyond academia must devote more time and resources to ethics education and practices on college campuses.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SO: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WM: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their time. Special thanks to J. Solis for assistance in data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1709760/full#supplementary-material

References

Adzima, K. (2020). Examining online cheating in higher education using traditional classroom cheating as a guide. Electron. J. E Learn. 18, 476–493. doi: 10.34190/JEL.18.6.002

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., and Sorenson, C. (2010). Introduction to research in education. 8th Edn. Belmont, California: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Benitez, J. A., and Wingenbach, G. (2025). Masks off: Exploring undergraduates’ motivations to cheat during COVID-19. Journal of Academic Ethics, 23, 1593–1608. doi: 10.1007/s10805-025-09616-0

Blaskey, S., Leibowitz, A., and Conarck, B. (2021). Surfside tower was flawed from day one. Designs violated the code, likely worsened collapse. Miami, Florida: Miami Herald.

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., McGowan, U., East, J., et al. (2013). ‘Teach us how to do it properly!’ An Australian academic integrity student survey. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 1150–1169. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.777406

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Davidson, L. (2021). Tax cheats are costing the U.S. $1 trillion a year, IRS estimates. New York, NY: Bloomberg.

Dillman, D. A., Phelps, G., Tortora, R., Swift, K., Kohrell, J., Berck, J., et al. (2009). Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the internet. Soc. Sci. Res. 38, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.03.007

Eaton, S. E. (2020). Academic integrity during COVID-19: reflections from the University of Calgary. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 48, 80–85. doi: 10.11575/PRISM/38013

Ellis, C., and Murdoch, K. (2024). The educational integrity enforcement pyramid: a new framework for challenging and responding to student cheating. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 49, 924–934. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2024.2329167

Feinberg, J. M. (2009). Perception of cheaters: the role of past and present academic achievement. Ethics Behav. 19, 310–322. doi: 10.1080/10508420903035299

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., and Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education. 8th Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Ghanem, C. M., and Mozahem, N. A. (2019). A study of cheating beliefs, engagement, and perception–the case of business and engineering students. J. Acad. Ethics 17, 291–312. doi: 10.1007/s10805-019-9325-x

Gilman, S. C. (2005). Ethics codes and codes of conduct as tools for promoting an ethical and professional public service: comparative successes and lessons. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract., 1–76.

Guerrero-Dib, J. G., Portales, L., and Heredia-Escorza, Y. (2020). Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 16, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s40979-020-0051-3

Helms, J. E., Henze, K. T., Sass, T. L., and Mifsud, V. A. (2006). Treating Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients as data in counseling research. Counsel. Psychol. 34, 630–660. doi: 10.1177/0011000006288308

Henton, L. (2021). Integrity, communication key to avoiding academic misconduct. [University]Today. Available online at: https://today.[University].edu/2021/05/13/integrity-communication-key-to-avoiding-academic-misconduct/ (Accessed September 12, 2022).

Hobbs, T. D. (2021). Cheating at school is easier than ever—and it’s rampant. Available online at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/cheating-at-school-is-easier-than-everand-its-rampant-11620828004 (Accessed October 31, 2022).

Hollman, T., Palmer, N. F., Chaffin, D., and Luthans, K. (2021). Lying, cheating, & stealing: strategies for mitigating technology driven academic dishonesty in collegiate schools of business driven academic dishonesty in collegiate schools of business. Mountain Plains J. Bus. Technol. 22, 31–50.

Jantos, A. (2021) Motives for cheating in summative e-assessment in higher education - a quantitative analysis. EDULEARN21 Proceedings, 8766–8776.

Jenkins, B. D., Golding, J. M., Le Grand, A. M., Levi, M. M., and Pals, A. M. (2023). When opportunity knocks: college students’ cheating amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach. Psychol. 50, 407–419. doi: 10.1177/00986283211059067

Klein, H. A., Levenberg, N. M., McKendall, M., and Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: how do business school students compare? J. Bus. Ethics 72, 197–206. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9165-7

Kobayashi, E., and Fukushima, M. (2012). Gender, social bonds, and academic cheating in Japan. Sociol. Criminol. Fac. Pub. 82:402. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2011.00402.x

Koscielniak, M., and Bojanowska, A. (2019). The role of personal values and student achievement in academic dishonesty. Front. Psychol. 10:1887. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01887,

Lancaster, T., and Cotarlan, C. (2021). Contract cheating by STEM students through a file sharing website: a COVID-19 pandemic perspective. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 17:3. doi: 10.1007/s40979-021-00070-0

Lindner, J. R., and Wingenbach, G. (2002). Communicating the handling of nonresponse error in journal of extension research in brief articles. J. Ext. 40:6RIB1.

Lützén, K., Nordström, G., and Evertzon, M. (1995). Moral sensitivity in nursing practice. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 9, 131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1995.tb00403.x,

Mayo, D. S. (2010). Comparisons of perceptions of North Carolina community college chief academic officers and faculty on codes of conduct. Doctoral dissertation. Greenville, North Carolina: East Carolina University.

McCabe, D. L., and Pavela, G. (2004). Ten (updated) principles of academic integrity: how faculty can foster student honesty. Change 36, 10–15. doi: 10.1080/00091380409605574

McCabe, D. L., and Trevino, L. K. (1993). Academic dishonesty: honor codes and other contextual influences. J. High. Educ. 64, 522–538. doi: 10.2307/2959991,

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., and Butterfield, K. D. (1999). Academic integrity in honor code and non-honor code environments: a qualitative investigation. J. High. Educ. 70, 211–234. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1999.11780762

McGee, K. (2020). [University] investigates cheating case involving Chegg website. Austin, Texas: Texas Tribune.

Narvaez, D. (2001) Ethical sensitivity. Activity booklet 1 Available online at: http://www.nd.edu/~dnarvaez/ (Accessed January 16, 2023).

Noorbehbahani, F., Mohammadi, A., and Aminazadeh, M. (2022). A systematic review of research on cheating in online exams from 2010 to 2021. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 8413–8460. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-10927-7,

Okolo, E. C., Appiah, I., and Wingenbach, G. (2025). Conflicts between academic misconduct and university honor codes: Implications for ethical behavior. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 21. doi: 10.1007/s40979-025-00198-3

Olafson, L., Schraw, G., Nadelson, L., Nadelson, S., and Kehrwald, N. (2013). Exploring the judgment-action gap: college students and academic dishonesty. Ethics Behav. 23, 148–162. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2012.714247

Orosz, G., Tóth-Kiràly, I., Böthe, B., Paskuj, B., Berkics, M., Fülöp, M., et al. (2018). Linking cheating in school and corruption. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 68, 89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2018.02.001

Ott, R. L., and Longnecker, M. T. (2015). An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. 7th Edn. Belmont, California: Brooks Cole.

Peled, Y., Eshet, Y., and Grinautski, K. 2013 Perceptions regarding the seriousness of academic dishonesty amongst students – a comparison between face-to-face and online courses. Chais Conference on Instructional Technologies Research, 69–74

Purpose & Values | Texas A&M University. (2021). College Station, Texas. https://www.tamu.edu/about/purpose-values.html

Reedy, A., Pfitzner, D., Rook, L., and Ellis, L. (2021). Responding to the COVID-19 emergency: student and academic staff perceptions of academic integrity in the transition to online exams at three Australian universities. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 17:9. doi: 10.1007/s40979-021-00075-9

Rest, J. R. (1984). Research on moral development: implications for training counseling psychologists. Counsel. Psychol. 12, 19–29. doi: 10.1177/0011000084123003

Sarita, R. D. (2015). Academic cheating among students: pressure of parents and teachers. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 793–797.

Schutte, I. W., Kamans, E., Wolfensberger, M. V., and Veugelers, W. (2017). Preparing students for global citizenship: the effects of a Dutch undergraduate honors course. Educ. Res. Int. 2017:631. doi: 10.1155/2017/3459631

Schutte, I., Wolfensberger, M., and Tirri, K. (2014). The relationship between ethical sensitivity, high ability and gender in higher education students. Gift. Talented Int. 29, 39–48. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2014.11678428

Schwartz, S. H. (1968). Words, deeds and the perception of consequences and responsibility in action situations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 10, 232–242. doi: 10.1037/h0026569

Shu, L. L., Gino, F., and Bazerman, M. H. (2011). Dishonest deed, clear conscience: when cheating leads to moral disengagement and motivated forgetting. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 330–349. doi: 10.1177/0146167211398138,

Sousa, V. D., Driessnack, M., and Mendes, I. A. C. (2007). An overview of research designs relevant to nursing: part 1: quantitative research designs. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 15, 502–507. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692007000300022,

Stankovska, G., Dimitrovski, D., Memedi, I., and Ibraimi, Z. (2019). Ethical sensitivity and global competence among university students. Bulgarian Comp. Educ. Soc. 17, 132–138.

Stenmark, C. K., Antes, A. L., Thiel, C. E., Caughron, J. J., Wang, X., and Mumford, M. D. (2011). Consequences identification in forecasting and ethical decision-making. J. Emp. Res. Human Res. Ethics 6, 25–32. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.25,

Stephens, J. M. (2017). How to cheat and not feel guilty: cognitive dissonance and its amelioration in the domain of academic dishonesty. Theory Pract. 56, 111–120. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2017.1283571

Stone, B. W. (2024). Generative AI in higher education: uncertain students, ambiguous use cases, and mercenary perspectives. Teach. Psychol. 52, 347–356. doi: 10.1177/00986283241305398

Subreddit (2024). Roomate [sic] is blatantly cheating [online forum post]. San Francisco, California: Reddit.

Surahman, E., and Wang, T. H. (2022). Academic dishonesty and trustworthy assessment in online learning: a systematic literature review. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 38, 1535–1553. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12708

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 48, 1273–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Tang, D., and Huang, M. (2024). Dilemmas and solutions for sustainability-based engineering ethics: lessons learned from the collapse of a self-built house in Changsha, Hunan, China. Buildings 14:2581. doi: 10.3390/buildings14082581

Taşgın, A. (2018). The relationship between pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards research and their academic dishonesty tendencies. Int. J. Prog. Educ. 14, 85–96. doi: 10.29329/ijpe.2018.154.7

Tatum, H. E. (2022) Honor codes and academic integrity: Three decades of research. Journal of College and Character, 23, 32–47. doi: 10.1080/2194587X.2021.2017977

Tirri, K., and Nokelainen, P. (2007). Comparison of academically average and gifted students’ self-related ethical sensitivity. Educ. Res. Eval. 13, 587–601. doi: 10.1080/13803610701786053

Walker, A. (2021). Collapsed surfside towers actually broke building code from the very beginning. Curbed. Available online at: https://www.curbed.com/2021/08/miami-condo-collapse-structural-flaws.html (Accessed December 13, 2022).

Waltzer, T., and Dahl, A. (2023). Why do students cheat? Perceptions, evaluations, and motivations. Ethics Behav. 33, 130–150. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2022.2026775

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., and Moore, B. (2016). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A study of individual factors. Ethics Behav. 27, 401–422. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535

Keywords: academic integrity, cheating, perceptions, ethics, student honor pledge

Citation: Bennett LC, Odom SF, Wingenbach G and Moody W (2025) Ethical sensitivities, perceptions of integrity, honor pledges, and cheating in higher education. Front. Educ. 10:1709760. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1709760

Edited by:

Ramon Ventura Roque Hernández, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, MexicoReviewed by:

David A. Rettinger, University of Tulsa, United StatesPatrik Holm, Karlstad University, Sweden

Copyright © 2025 Bennett, Odom, Wingenbach and Moody. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lanice C. Bennett, bGJlbm5ldHRAdGFtdS5lZHU=

Lanice C. Bennett

Lanice C. Bennett Summer F. Odom

Summer F. Odom Gary Wingenbach

Gary Wingenbach Whitney Moody

Whitney Moody