- 1African Center of Excellence for Innovative Teaching and Learning Mathematics and Science (ACEITLMS), Rwamagana, Rwanda

- 2University of Rwanda-College of Education (UR-CE), Kayonza, Rwanda

Introduction: Project-based Learning (PjBL) holds a paramount foundation in fostering a human resource equipped with practical skills and innovative mindset necessary for sustainable growth and prosperity.

Methods: This study investigated the teachers’ insights and practices in project-based learning teaching methods of mathematics, with eight teachers selected in one district of Rwanda. A qualitative exploratory design was used to collect data from eight teachers selected through convenience sampling. In-depth interviews were conducted, and the data were thematically analyzed using Taguette software.

Results: The results from the study showed that teachers have a limited understanding of PjBL, which hinders its application in their regular mathematics instruction. Lack of awareness, time constraints, limited skills, overcrowded classes, lack of school leaders’ support, and lack of interest are barriers to teachers incorporating PjBL in mathematics instructions.

Discussion: Mathematics teachers’ understanding and classroom practices of project-based learning influence its implementation. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on project-based learning by providing empirical insights into how mathematics teachers in primary schools of Nyamasheke district, Rwanda, perceive and apply PjBL within their instructional practices.

Introduction

Teachers play a crucial role in applying Project-based learning (PjBL) since they design, facilitate, and assess students’ projects (Pan et al., 2021; Viro et al., 2020; Almulla, 2020). In contrast to traditional methods that often focus on rote memorization, PjBL encourages students to apply the acquired understanding to real-world problems to foster deeper understanding and retention of concepts (Karan and Brown, 2022; Mutanga, 2024). Project-based learning is a teaching method appropriate for mathematics instruction where abstract concepts should be made tangible and relevant through carefully designed projects (Miller and Krajcik, 2019; Rehman et al., 2024; Siregar, 2024). In primary education, especially in developing countries like Rwanda, adopting the PjBL teaching method nationwide can address critical educational gaps and enhance learning outcomes.

Project-based instructions enhance students’ understanding and interest in the learning subjects (Karan and Brown, 2022; Baghoussi et al., 2019). In developed countries such as the United States, Canada, and Finland, PjBL was adopted to foster students’ critical thinking, collaboration, and practical problem-solving skills (Juuti et al., 2021; Williamson, 2023; Eswaran, 2024). The integration of PjBL in these countries was supported by extensive teacher training programs, well-developed curricula, and robust educational resources (Rehman et al., 2024; McGibbon and Van Belle, 2015). PjBL is expected to contribute to the country’s economic growth, as it is once considered by governments.

Project-based learning was claimed to be a transformative educational strategy emphasizing student engagement through different students’ project execution (Syamsuddin et al., 2025; Juuti et al., 2021). However, PjBL in mathematics education is integrated differently depending on the availability of resources, teacher training, and infrastructure. For instance, the adoption of PjBL in Sub-Saharan Africa was hindered by large class sizes, inadequate teaching materials, and the need for extensive teacher professional development (Đerić et al., 2021; Muchira et al., 2023). Countries like South Africa and Kenya have made strides in adopting PjBL. However, limited resources and insufficient training were among the identified challenges (Wilson, 2021; Baghoussi et al., 2019; Aldabbus, 2018). Facing barriers linked with project-based learning can enhance a successful teachers’ application of PjBL within Sub-Saharan African countries.

Project-based learning was first introduced in Rwanda in 2015 with the launch of the Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC), with a shift from content-heavy and exam-oriented teaching to a learner-centered approach (Mbarushimana and Kuboja, 2016; MINEDUC, 2018). The CBC emphasized active learning, critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, positioning PjBL as a core pedagogical strategy to achieve these goals. Its introduction aims to national priorities of equipping students with practical skills and fostering lifelong learning to meet the demands of the 21st century, as outlined in Rwanda’s Vision 2050 (REB, 2015). However, PjBL implementation by teachers in Rwanda’s primary schools is not without barriers. For instance, it was found that the teaching and learning of mathematics in Rwanda is still teacher-centered (Otara et al., 2019; Nsengimana et al., 2021). In addition, Ukobizaba et al. (2025) found that the teaching and learning of mathematics in primary and secondary schools is still dominated by traditional learning characterized by paper and pen or note-taking. Since PjBL can be a solution to enhance students’ engagement in mathematics instruction (Juuti et al., 2021), this study sought to explore the teachers’ understanding, insights, and applications of PjBL in mathematics instruction within primary schools of Nyamasheke district.

Project-based learning has become increasingly recognized in educational research and curriculum reforms as an effective teaching approach in integrated science education, aimed at enhancing students’ 21st-century skills and competencies (Karan and Brown, 2022; Serin, 2019). In developed countries, PjBL has become integral to modern educational strategies, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. Countries such as the United States, Canada, and Finland have adopted PjBL to foster critical thinking, collaboration, and practical problem-solving skills among students (Juuti et al., 2021). The integration of PjBL in these regions is supported by extensive teacher training programs, well-developed curricula, and robust educational resources (Rehman et al., 2024; Morrison et al., 2021). Like in other many developing countries, PjBL was first introduced in Rwanda in 2015 with the launch of the Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC), with a shift from content-heavy and exam-oriented teaching to a learner-centered approach (Mbarushimana and Kuboja, 2016; MINEDUC, 2018). The CBC emphasized active learning, critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, positioning PjBL as a core pedagogical strategy to achieve these goals. Its introduction aims to national priorities of equipping students with practical skills and fostering lifelong learning to meet the demands of the 21st century, as outlined in Rwanda’s Vision 2050 (REB, 2015).

The mathematics achievements situation is worse in African countries, where the standard of mathematics performance is still low compared to other continents like Europe and America (Bethell, 2016; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2023). In Africa, where educational disparities persist and traditional rote learning approaches often prevail, PjBL offers a reformed teaching approach that promotes active engagement, collaboration, and creativity, addressing the region’s demanding necessity for skilled professionals (Morrison et al., 2021). There are no synthesized data about the standards of students’ performance in East African Countries (EAC), yielding a gap in the EAC with the rest of the countries in Africa. It may take centuries for EAC countries to reach the OECD level if no measures are taken to reform the teaching and learning practices (Bethell, 2016). Similarly, mathematics instruction in Rwanda is still teacher-centered. Teachers are still considered a source of knowledge. Students are passive and sit in class listening to the teachers explaining the concepts (Nsengimana et al., 2021; Ukobizaba et al., 2020). Thus, without teachers’ adequate knowledge, the implementation of competence-based curricula may remain superficial, underscoring the strategic importance of this study.

Although the Rwandan Government has supported continuous professional development programs enhancing mathematics instruction and learning outcomes, mathematics has emerged as the lowest-performing subject among national leaving examination subjects in Rwanda’s schools. For instance, in the recently released results of the 2024/2025 academic year, only 27% of primary pupils passed the primary leaving examination (PLE) of Mathematics (KT-Press Team, 2025). The pass mark is 50% marks. While reacting to these figures on the release day (20/08/2025), the Ministry of Education described it as “alarming” and requiring urgent intervention. The results in the previous years were not publicly released by the MINEDUC or the National Examination and Supervision Authority (NESA), but the primary pupils’ performance in Mathematics is consistently low in Rwandan primary schools.

Although the project-based learning approach seems important in enhancing the overall academic achievement of learners, the willingness of teachers to implement it remains critical, and its implications in science and mathematics education are an integral matter of serious concern (Twahirwa et al., 2021). In addition, Rwanda’s limited research about PjBL, with the abundance of studies from developed countries, highlights the need for contextualized African perspectives. Studies on PjBL in the Rwandan context help researchers and education stakeholders identify professional development needs for mathematics teachers. In addition, this study ensures whether teachers have the necessary skills and understanding to implement PjBL successfully. Further, this study fills the gap in the existing literature about the lack of research focusing on PjBL in the Rwandan context, particularly in the Nyamasheke district. Enhancing the incorporation of teaching approaches supporting learner-centered pedagogies, such as project-based learning, may be one strategy that enhances students’ mathematics achievement. Ultimately, the present study sought to shed light on teachers’ understanding and practices of PjBL toward implementing CBC in mathematics education.

Research questions

This study was guided by the following research questions:

1. How do the mathematics teachers understand project-based learning?

2. What are the mathematics teachers’ insights into project-based learning?

3. How are project-based learning teaching methods applied by selected teachers in mathematics instruction?

4. What are the identified barriers preventing teachers from applying project-based learning in mathematics instruction?

5. What are the teachers’ suggestions to implement project-based learning in mathematics instruction?

Methodology

Research design

This study used an exploratory research design (Swedberg, 2020) to collect qualitative data. An exploratory qualitative design was adopted because there is limited prior research on the implementation of project-based learning (PjBL) in the Rwandan educational context, particularly in mathematics instruction at the primary level. Given this gap, an exploratory approach allowed the researcher to understand teachers’ experiences, perceptions, and challenges without being constrained by predetermined variables or hypotheses (Stebbins, 2001). Thus, this study explored the teachers’ understanding, insights, and application of PjBL while teaching mathematics to Grade Five (Primary Five) students.

Population, sample, and sampling techniques

The population of the study involved teachers who teach mathematics in upper primary classes within the Nyamasheke district. A randomized convenience sampling technique (Golzar et al., 2022; Oribhabor and Anyanwu, 2019) was used to get a sample of teachers. Through the process, teachers have shared a link via a WhatsApp group of primary teachers teaching in the Nyamasheke district. The teachers opened the link and filled in information, including their contact address. A group called WhatsApp was found to be an effective channel for reaching the majority of teachers. All teachers who teach mathematics in the upper primary have the right and equal chance to fill out the form. This minimized the bias and ensured randomization. This sampling technique was an effective approach for the researcher to afford participants online who would be otherwise very difficult to reach face-to-face in their environments.

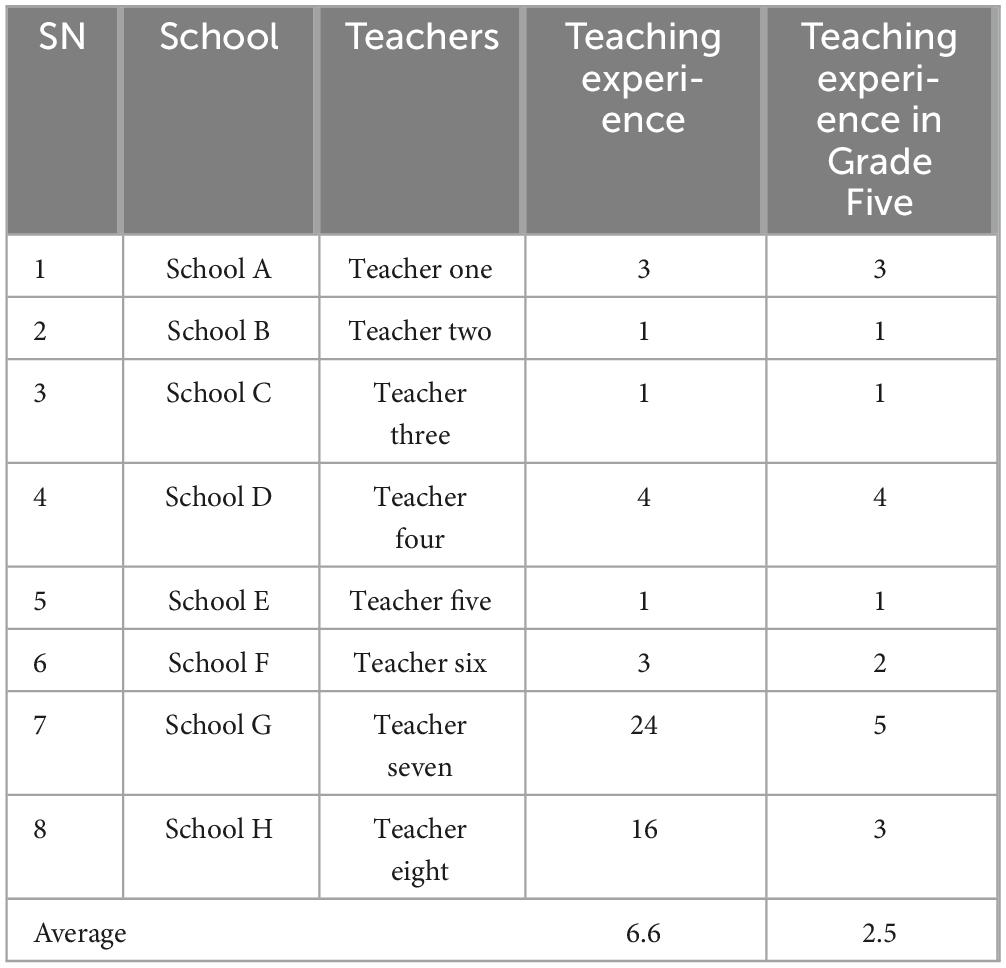

The sample size was initially composed of 29 teachers who submitted the forms and agreed to participate in the interview. During data collection, data saturation was followed to determine the number of participants to be interviewed. According to Braun and Clarke (2021), data saturation refers to the information redundancy or the point at which no new themes or codes “emerge” from data. Thus, the data was saturated at six teachers. However, the researcher added two more teachers and stopped at eight teachers since no new information was being captured from the participants. These teachers are from eight different schools, including schools A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. The teachers’ identifications were coded for anonymity reasons (see Table 1).

The sampled teachers have a teaching experience of 6.6 years. Among the participants, five out of eight have more than 3 years of teaching experience. In general, teachers have 2.5 years of teaching experience in Grade Five. Half of the participants have three or more years of teaching experience in mathematics in Primary Five. Although Table 2 shows that three teachers are novices in the profession with 1 year of teaching experience, the average teaching experience suggests that teachers may have some prior understanding of project-based learning.

Table 2. Primary leaving examination (PLE) level (P6) performance by subject in the 2024/2025 academic year.

Instrument

Data collection involved semi-structured interviews that were used to investigate the teachers’ insights about PjBL. The instrument was made of seven items. The interview provided insights into the teachers’ understanding of PjBL, how they practice PjBL while teaching mathematics, challenges met during implementation, and suggestions to implement PjBL into mathematics instructions. The results served as the baseline informing the current status of the teacher’s understanding and practices of PjBL, which provided an adequate intervention based on the results findings.

Instrument validity and reliability

The instrument for data collection was self-constructed. Thus, the research instrument was checked for face and content validity before use (Cohen et al., 2018). To this end, the interview guide underwent rigorous peer reviews to check for validity. It was shared with two experts in research and lecturers from the University of Rwanda-College of Education, to check for content and face validity (Connell et al., 2018). Thus, some items were edited to make them more understandable, while others were removed. For instance, an item such as “What did you perceive as the main benefits or outcomes of using project-based learning to teach mathematics?” was removed. The final version used during the interview is made of five open-ended questions corresponding to five research questions. The interview took between 15 and 20 min.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the authors adhered to four standards suggested by Cresswell (2018), including credibility, dependability, generalizability, and confirmability. A member check and peer review were used to ensure the credibility of the data. Within this regard, transcripts were shared with participants to confirm that their views and experiences had been accurately represented. This ensured data credibility and accuracy. Dependability was ensured by using notebooks and audio records to ensure that findings were grounded in the data during data analysis. Transferability was also confirmed by referring to the relevance of the study’s findings and the potential for the findings to be applied to other similar contexts. Finally, through member check, confirmability ensured that the transcripts were from informants’ thoughts. In this regard, the transcripts were shared with participants to validate their accuracy. Further, a peer debriefing was carried out and it involved a Ph.D. scholar from the University Of Rwanda College Of Education to enhance the study’s credibility, transparency, and trustworthiness. The scholar is knowledgeable in qualitative study. Peer debriefing was carried out during data analysis to discuss coding decisions, emerging themes, and interpretations, ensuring that findings are well-reported and supported by data.

Data collection and ethical consideration

This study is a part of the Ph.D. program’s requirements. Thus, data were collected professionally by considering potential ethical issues. The main author obtained a research clearance letter from the UR-CE Research Screening and Ethics Clearance Committee (RSEC-C) through the Research and Innovation Unit. The obtained letter has a reference number Ref: DRI-CE/031(a)/EN/gi/2024. A recommendation letter was also provided and used while requesting permission to conduct a study within the Nyamasheke district. Participants were, and they were informed of the study’s purpose. They were presented with an authorization letter provided by the district office.

Data were collected using two approaches including paper and pen, and audio recording. These two approaches served to keep all data used during analysis. Teachers were interviewed one after another until the data needed were exhaustive as per the research questions. Each participant was assigned a code for protection. For instance, codes such as Teacher Two from School B were used while reporting participants’ ideas. Data were kept in the researcher’s computer with a personal code for the data file. To identify the participants, the teachers were assigned codes such as Teacher One, Teacher Two to Teacher Eight for anonymity reasons.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Taguette software (Rampin and Rampin, 2021). Although Taguette is not as robust as N-Vivo, it is an open-source, user-friendly tool suitable for researchers seeking a straightforward, cost-effective option for coding and analyzing qualitative data. The analysis was conducted through systematic procedures, progressing from smaller units of data toward forming meaningful statements (Mezmir, 2020; Cohen et al., 2018). Thematic analysis was chosen for this qualitative study because it allows the researcher to move beyond merely describing participants’ responses to uncover deeper insights about their experiences, perceptions, and barriers to PjBL. An inductive approach resulted in creating themes. Themes were created based on research questions (see also the Section “Results”). The data analysis process involved assembling the data, coding, comparing, building meaning and interpretation, and finally reporting the results (Elliott, 2018). Through this process, data was gathered, and patterns were identified, forming categories from emerging participants’ responses. Based on the themes, the presentation of the final results reflecting participants’ voices was developed.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the authors adhered to four standards suggested by Cresswell (2018). These are: credibility, dependability, generalizability, and confirmability. A member check was used to ensure the credibility of the data. Dependability was ensured by using an audit trail of data collection procedures used for data collection and analysis to verify that findings were grounded in the collected data. Transferability was also confirmed by referring to the relevance of the study’s findings and the potential for the findings to be applied to other similar contexts. Through audit trail and member check ensured that the results were internally consistent. However, the study involved eight mathematics teachers from the Nyamasheke district, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or larger populations. The themes include: (1) Teachers’ understanding of project-based learning, (2) The teachers’ application of project-based learning while teaching mathematics, (3) Teachers’ insights toward project-based learning, (4) Barriers hindering teachers from applying project-based learning and suggestions, and (5) Suggestions for the implementation of project-based learning. The results are presented based on themes as shown in the next section.

Results

Teachers’ understanding of project-based learning

In the study on mathematics teachers’ application of project-based learning (PjBL) for Primary Five students in Nyamasheke District, several key insights emerged regarding teachers’ understanding of PjBL. The results revealed a range of familiarity with PjBL, ranging from confusion and limited understanding to a more accurate understanding of PjBL. The little understanding teachers have received through training that was not directly linked with project-based learning during pre-service in Teacher Training Colleges (TTCs).

During the interview, teachers demonstrated a grasp of PjBL concepts. For instance, one teacher described PjBL as a methodology that helps students to deeply understand the lesson by using teaching aids and other tools. The teacher recognized PjBL as a teaching strategy that often requires tangible resources to enhance students’ comprehension, highlighting an understanding. Teacher Two from School B conveyed that PjBL involves students working on projects that address real-world problems. Teacher Two from School B argued, “It (PjBL) is a strategy of teaching students based on some of the projects that students can themselves create (Interview: 23 May 2024).” These findings indicate the teachers’ awareness of PjBL’s focus on student-driven and problem-solving-related activities.

The teachers’ understanding of PjBL is due to prior training. For instance, Teacher Four from School D said, “Last year, I attended the training about play-based learning. During the training, they also told us about project-based learning (Interview: 24 May 2024).” This implies that training helped teachers to get some concepts about PjBL. Additionally, Teacher Six from School F mentioned, “I learned this in teaching methodology when I was still a student in TTC (Interview: 25 May 2024).” Although these results suggest that teachers grasp some key concepts of PjBL, their explanations and practices contain confusion and a limited understanding.

One teacher claimed to have heard about PjBL for the first time while attending training about the Comprehensive Assessment Management Information System (CA-MIS). Teachers were told that they would also need to record students’ scores on project assessments. Teacher Seven from School G reported,

“… Before, none had explained, taught, or talked to me about PjBL. However, during CA-MIS training, they told us that there would be a project assessment. They explained to us what project assessment is (Interview: 23 May 2024).”

Most of the interviewed teachers had misconceptions about PjBL, reflecting confusion about its core principles and application. For example, one teacher initially thought of PjBL as an existing project to enhance the learning of students. However, after being explained, Teacher Seven from School G, later, admitted, “Eh it is clear now. I was confused before (Interview: 25 May 2024).” This reflects an initial misunderstanding of one teacher who perceived PjBL as just any project rather than a structured pedagogical approach. Another teacher seemed unclear about how PjBL fits into mathematics instruction. Teacher Eight from School H expressed, “In mathematics, I can’t easily grasp how it (PjBL) comes in the application (Interview: 25 May 2024).” During the interview, the researcher explained about PjBL. However, the informant could not understand. During the intervention, Teacher Five from School E said, “Please explain to me because I don’t understand very well about PjBL! (Interview: 24 May, 2024).” This indicates a need for continuous professional development to support teachers in PjBL and its practices in mathematics instruction.

The teachers’ application of project-based learning while teaching mathematics in upper primary schools

Only two teachers identified effective project-based learning activities that align well with PjBL principles during the interview. The PjBL principles involve real-world connection, students’ voice and choice, inquiry and innovation, sustained inquiry, reflection, critique, and revision, and public product (Abidin et al., 2020). However, only one out of eight interviewed teachers provided a PjBL activity in mathematics reflecting PjBL key observations. While teaching solids in mathematics, the teacher gave students a project to make boxes. These boxes served as teaching aids; students used them to learn mathematics concepts such as total surface area and volume. Teacher Two from School C reported,

“In mathematics, we made a watch, which we can use in teaching time. We also made boxes when we were learning cubes. A cube was useful since it can be used to keep different teaching aids, such as bottle tops. Students were able to find the total surface area and volume (Interview: 23 May 2024).”

These results indicate that this teacher taught different concepts in mathematics through different hands-on activities. Students got engaged directly with the content while addressing societal issues of waste management, creating teaching aids and tools to be used at school or home. This shows that the content became more relevant to students.

Despite limited understanding, some of the interviewed teachers were not able to apply PjBL in its realistic application. For instance, Teacher Eight from School H asked students to prepare 100 questions and answer them to prepare for national exams called PjBL. The teacher thus asked students to share them with colleagues through peer learning. It is known that these are just assignments or one of the ways of assessment approaches. Another teacher was uncertain if PjBL involved activities that students would do when they were in their homes. Teacher Eight from School H argued, “… when I am teaching solving equations for P6 students, I give them activities to be done individually while at home. I ask them about the relevance of that lesson in real life (Interview: 25 May 2024).” This result suggests a misunderstanding of the in-class and collaborative nature of PjBL principles. However, a project-based learning activity involves students exploring real-world problems and challenges and finding solutions through inquiry, data collection, and presentation. This activity is often done by students’ group collaboration with their colleagues. Therefore, the teacher’s confusion highlights a need for clearer guidelines and examples of implementing PjBL effectively in the classroom.

Teachers’ insights into project-based learning

Although most teachers do not clearly understand the PjBL concept, the explanation justifies the teachers’ interest in applying what they call PjBL. By applying PjBL, teachers showed an interest and a desire to enhance students’ engagement and understanding through practical and hands-on activities. Teacher Eight from School H argued that PjBL enhances independent learning and said, “It is the best way to teach learners in the best way using materials and learning independently (Interview: 25 May 2024).” Teachers also recognized PjBL’s ability to make lessons more interactive and relevant to students’ lives, which is likely to increase motivation and application of mathematical concepts.

Some of the interviewed teachers asserted that they have never applied PjBL in their instructions. However, they know that PjBL positively impacts students’ retention of learning materials and skills development. Teachers added that this approach integrates real-life experiences, making learning more relevant and impactful. PjBL was reported to be linked to everyday life experiences connecting classroom learning to home and environmental experiences which deepen students’ understanding. Teacher Five from School E highlighted this by stating, “Through PjBL, students do practical works, and they cannot forget what they have learned (Interview 24 May 2024).”

A teacher who applied PjBL witnessed that projects enhance students’ engagement and make complex concepts clearer. The teacher claimed that students were excited to create boxes for storing different objects as they were also learning about the volume of a cube. Teacher Two from School B argued, “Students were interested and were saying the usage of the box that they can make in real life (Interview: 23 May 2024).” The teacher observed and noted that the given practical task helped students grasp the dimensions of a cube more easily. A teacher explained those physically cutting cubes and identifying their length, width, and height made the lesson more understandable and engaging, demonstrating PjBL’s effectiveness in teaching mathematical concepts.

Barriers hindering teachers from applying project-based learning and suggestions

Time constraints and insufficiency of materials were reported by the interviewed teacher who applied PjBL among the challenges met. The teacher explained that it took a long time to execute the project. Teachers also reported a lack of awareness and a lack of teacher training. The lack of awareness is even for school leaders. Teacher Seven from School G witnessed,

“The school leader told us not to pay much attention to those things (about filling marks projects in CA-MIS). The headteacher explained that it is because there are no projects that we give to our students, and we make follow-ups when students implement them to get marks. However, he promised that the time will come when projects will be incorporated into our teaching. The headteacher promised they were just waiting (Interview: 25 May 2024).”

The participant teacher shows the lack of prioritizing PjBL teaching strategy as one educational policy that needs to be strengthened at different educational levels. Within this regard, after raising teachers’ awareness, school leaders should also be explained how PjBL works. This will make school leaders get involved in supporting teachers in applying for PjBL.

Teachers indicated that the main reason for not applying project-based learning (PjBL) is due to the lack of information and training about the teaching strategy. Teacher Two from School B expressed, “I didn’t have any information about it (project-based learning). But it is a good teaching strategy; not only in mathematics but also in other subjects (Interview: 24 May 2024).” Teacher Four from School D added, “I don’t have enough skills about PjBL. Even what I have done is because we have mentors to assist us with our subjects (Interview: 24 May 2024).”

Teacher Three from School C further claimed, “We don’t know about PjBL. To apply it is just one’s self-arrangement. No training has been received about PjBL.… It is a good strategy, but as you may understand we don’t have enough information about it (Interview 23 May, 2024).”

Another significant barrier to implementing PjBL is the time constraint due to the overloaded school timetable. Teacher Three from School C explained, “There is a time when you look at the available time, and find that by using PjBL, you will delay and fail to complete other lessons (Interview: 23 May 2024).” The lack of resources and large class sizes were also highlighted as significant challenges. Teacher Four from School D added, “Sometimes, a teacher may have an overcrowded class, large class, timing, an overloaded timetable, and then you fail to give a project assessment after realizing that it will not be easy for you to evaluate and assess it (Interview: 24 May 2024).” These responses indicate that the current school schedules do not accommodate the additional time required for PjBL activities.

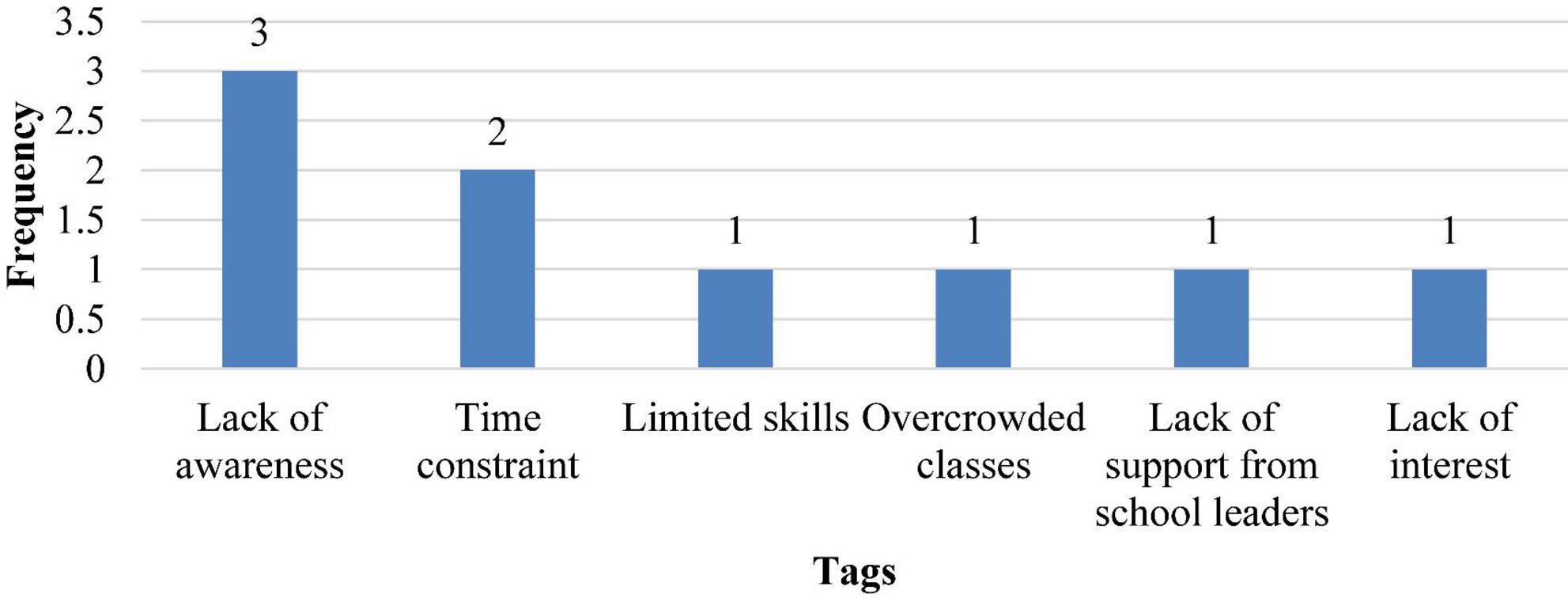

The Taguette analysis results showed the frequency of tags regarding the barriers hindering teachers from implementing PjBL (see Figure 1). The Figure below shows the frequency of tags.

Figure 1 displays the reported frequency of tags about the barriers to PjBL implementation, including lack of awareness, time constraints, limited skills, overcrowded classrooms, lack of support from school leaders, and lack of interest. The results indicate that the most significant barrier hindering teachers from PjBL includes a lack of awareness, which was reported three times. This suggests that a substantial proportion of teachers are either unfamiliar with the principles of PjBL or lack sufficient understanding of how to implement it effectively in the classroom. The second most frequently reported barrier is time constraint, which was reported two times. This indicates that even when teachers are aware of PjBL, they may struggle to allocate reasonable time for planning, facilitating, implementing, and assessing students’ projects within the limited instructional hours. These two barriers imply professional development and workload management, directly influencing teachers’ readiness and capacity to integrate PjBL into their teaching practices.

Although barriers such as limited skills, overcrowded classes, lack of support from school leaders, and lack of interest were reported once. These barriers indicate that targeted interventions can enhance the effectiveness of PjBL implementation even if they may be reflected in fewer teachers. Limited skills suggest a need for focused professional development and training programs to equip teachers with the practical competencies required for designing and facilitating project-based activities. Overcrowded classrooms inform a need for adopting flexible grouping strategies or differentiated instruction to ensure that all students are engaged in projects. Minimal administrative support indicates the necessity of fostering a school culture that encourages innovation, provides resources, and recognizes teachers’ efforts in implementing PjBL. Finally, an on-going encouragement, mentorship, and demonstration of the benefits of PjBL are required to raise the teachers’ interest in applying PjBL in mathematics instructions on a regular basis.

Suggestions for the implementation of project-based learning

The interviewed teachers suggested how PjBL should be incorporated into their instructions. It was suggested that PjBL should be one of the Government’s priorities. For instance, Teacher Two from School B argued that teachers should be trained on the PjBL application in different subjects. The teacher added that teachers should be accompanied by people experienced in PjBL. Further, Teacher Four from School D suggested that there should be a manageable number of students in class (reducing the classroom population) for the teacher to be able to follow up on students’ projects. They should reduce the teaching periods on the timetable. Teacher Seven from School G suggested that some lessons should be allocated at a special time on the timetable. The teacher argued,

“… On the weekend, if for example, a lesson takes 40 min, using weekends, I can start from 8:00 am until 12:00 noon. In that case, I can teach two lessons, and thus, I will at the same time solve the problem related to time (Interview: 25 May 2024).”

Project-based Learning should be given a specific time in the teachers’ timetable. The curriculum should guide teachers about how projects embedded in the curriculum will be implemented. Prioritizing PjBL within the national education policy may enhance students’ learning outcomes in different subjects, particularly mathematics.

Discussion

Results from interviews showed that teachers have limited knowledge and understanding of PjBL whereby some of them could not differentiate PjBL-related activities from other activities given to students. The limited knowledge highlights a significant gap in the effective implementation of PjBL. This confusion can result in activities that do not fully engage students or fail to meet the educational objectives of PjBL. A similar challenge was also found by other scholars. For instance, Aldabbus (2018) found that teachers often struggle with designing PjBL activities that are both educationally valuable and feasible within the constraints of the classroom environment. Although, PjBL requires teachers to provide detailed examples and scaffolding to design PjBL activities that align with PjBL core principles (Morrison et al., 2021). In addition, Karan and Brown (2022) and suggested that for PjBL to be effective, activities must be well-designed to promote critical thinking, collaboration, and real-world problem-solving. The findings suggest that without clear guidelines and support, teachers may continue struggling with implementing PjBL effectively, limiting its potential benefits for student learning.

There is a gap between theoretical understanding and practical perception, showing that participants may misinterpret or simplify the concept compared to how it is conceptualized in the educational literature. While PjBL is defined as a self-directed learning based on in-depth investigations to look for solutions to problems in the environment (Eswaran, 2024; Karan and Brown, 2022), teachers think that PjBL is simply about giving students activities to be performed for a long time. The study participants’ understanding of PjBL is diverging from the literature mainly due to limited exposure to the theoretical foundations and practical models of PjBL (Mutanga, 2024). Teachers did not receive sufficient training or continuous professional development specifically focused on the design and facilitation of authentic projects. Subsequently, teachers often equate PjBL with simple group work, end-of-term assignments, or hands-on activities rather than viewing it as an extended, inquiry-driven process that integrates knowledge and skills to solve real-life problems.

The limited understanding observed among Rwandan teachers suggests that current training programs are necessary to arouse their awareness, skills, and efficacy in applying innovative teaching methods (Nkundabakura et al., 2024; Muchira et al., 2023). The misconceptions about PjBL identified by teachers indicate a broader issue in teachers’ understanding of PjBL. Similarly, Juuti et al. (2021) found that teachers frequently refer to PjBL as simply assigning student projects rather than viewing it as a student-centered learning strategy emphasizing inquiry, collaboration, and real-world application. As revealed by the study, the teachers’ limited knowledge and misunderstanding calls for more effort to be put in monitoring the implementation of CBC in both primary and secondary schools in Rwanda. By raising teachers’ awareness and monitoring the implementation of competence-based pedagogies including those related to developing projects will make learning more active and relevant students within Nyamasheke in particular and Rwanda in general.

The time constraints, the lack of resources and support were also identified as major barriers hindering interviewed teachers from applying PjBL in mathematics instructions. The same barriers were found by different scholars across different countries (e.g., Aldabbus, 2018; Muchira et al., 2023; Đerić et al., 2021). In developed countries, project-based learning (PjBL) has become integral to modern educational strategies, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. The integration of PjBL developed countries is supported by extensive teacher training programs, well-developed curricula, and robust educational resources (Morrison et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2021). While developing countries such as those located in the EAC region, including Rwanda, have made efforts in adopting PjBL, there are still challenges linked to limited resources and insufficient training for educators (Aldabbus, 2018; Baghoussi et al., 2019). In addition, the widespread adoption of PjBL in Sub-Sharan Africa is hindered by large class sizes, inadequate teaching materials, and the need for extensive teacher professional development (Đerić et al., 2021; Muchira et al., 2023). To address these challenges, a sustained investment in teacher professional development, adequate resource provision, and institutional support is needed to enable effective implementation of project-based learning in mathematics instruction.

The fact that few of the interviewed teachers have ever applied PjBL indicates that the CBC implementation remained theoretical rather than practical in some aspects of it. This challenge is not only found in Rwanda. Scholars such as Meng et al. (2023) and Aldabbus (2018) revealed that the practical implementation of PjBL in these countries often faces challenges such as limited teacher training, insufficient resources, and rigid examination-oriented educational systems. For instance, in Kenya, it was found that teachers often struggle to implement these methods effectively due to insufficient training and support (Muchira et al., 2023; Cintang et al., 2018). In Uganda and Tanzania, overcrowded classrooms and limited access to teaching aids were reported as barriers preventing teachers from effectively applying PjBL in mathematics instruction (Đerić et al., 2021). Continuous teacher support is needed to ensure the curriculum is implemented as a whole. Within the same vein, Aldabbus (2018) and Morrison et al. (2021) argued that it is essential to provide teachers with the necessary support, such as professional development, access to teaching materials, and flexible scheduling. To effectively shift from teacher-centered to learner-centered pedagogy, teachers should be equipped with skills about how to link the concepts found in the curriculum with students’ projects. Thus, ongoing professional development will equip teachers with the understanding and skills necessary to implement PjBL effectively in their regular instructions.

In the Rwandan CBC, PjBL is conceptualized as a learner-centered pedagogical approach that engages students in exploring real-life problems and creating practical solutions through collaborative projects implementation (REB, 2015). PjBL encourages learning by doing, whereby students apply knowledge, skills, and attitudes to meaningful tasks that reflect real-world contexts. PjBL is integrated across subjects to develop key competencies such as critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, creativity, and cooperation (Rehman et al., 2024; Siregar, 2024). Although PjBL is officially included and strongly encouraged in Rwanda’s CBC for both primary and secondary schools, but in practice, its implementation remains limited and inconsistent. Teachers may struggle to implement PjBL effectively due to challenges such as large class sizes, time constraints, limited teaching resources, insufficient training, and the pressure to complete the syllabus and prepare students for exams. However, teachers should make a paradigm shift from teacher-centered to a learner-centered pedagogy whereby they guide learners through inquiry, planning, execution, and presentation of projects rather than merely transmitting knowledge. Professional development and resource mobilization are essential to build the capacity and confidence needed to implement PjBL effectively, gradually transforming traditional classrooms into dynamic, project-driven learning environments.

Conclusion and limitations

The study revealed significant insights into understanding, insights, and practices about PjBL of teachers selected from the Nyamasheke district, Rwanda. The study also explored barriers hindering teachers from applying PjBL and suggested best practices for implementing PjBL into regular mathematics instructions. A strong interest in applying PjBL was found among teachers despite the limited teachers’ understanding of PjBL. Lack of awareness; time constraints, limited skills, overcrowded classes, lack of school leaders’ support, and lack of interest were reported as barriers hindering teachers from implementing PjBL. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on project-based learning by providing empirical insights into how mathematics teachers in primary schools of Nyamasheke district, Rwanda, perceive and apply PjBL within their instructional practices. This study fills a gap in the literature on PjBL in Global South contexts and provides evidence for how teachers’ limited understanding can undermine curriculum reforms. This study recommends a need for more comprehensive and continuous professional development that equips teachers with both the theoretical understanding and practical skills needed to effectively implement PjBL.

This study employed eight teachers from the Nyamasheke district, limiting the generalizability of the results. However, the findings from the study may serve as a reference for other settings with a similar context. For further studies, comparative studies across districts of Rwanda, quantitative assessments of PjBL’s impact on student performance within the district, or longitudinal studies tracking teachers before and after targeted training should be conducted.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UR-CE Research Screening and Ethics Clearance Committee (RSEC-C). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FU: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AU: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the African Center of Excellence for Innovative Teaching and Learning of Science and Mathematics (ACEITLMS). We are grateful to all the teachers who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abidin, Z., Utomo, A. C., Pratiwi, V., and Farokhah, L. (2020). Project-based learning - literacy in improving students’ mathematical reasoning abilities in elementary schools. J. Madrasah Ibtidaiyah Educ. 4, 39–52. doi: 10.32934/jmie.v4i1.170

Aldabbus, S. (2018). Project-based learning: Implementation and challenges. Int. J. Educ. Learn. Dev. 6, 71–79.

Almulla, M. A. (2020). The effectiveness of the Project-based learning (PBL) approach as a way to engage students in learning. SAGE Open 10:15. doi: 10.1177/2158244020938702

Baghoussi, M., Zoubida, gand El Ouchdi, I. (2019). The implementation of the project-based learning approach in the Algerian EFL context: Curriculum designers’ expectations and teachers’ obstacles. Arab World Engl. J. 10, 271–282. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no1.23

Bethell, G. (2016). Mathematics education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Status, challenges, and opportunities. Washington DC: World Bank, 1–212.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 13, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Cintang, N., Setyowati, D. L., and Handayani, S. S. D. (2018). The obstacles and strategy of project based learning implementation in elementary school. J. Educ. Learn. 12, 7–15. doi: 10.11591/edulearn.v12i1.7045

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education, 8th Edn, Vol. 59. Milton Park: Routledge.

Connell, J., Carlton, J., Grundy, A., Taylor Buck, E., Keetharuth, A. D., Ricketts, T., et al. (2018). The importance of content and face validity in instrument development: Lessons learnt from service users when developing the Recovering quality of life measure (ReQoL). Quality Life Res. 27, 1893–1902. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1847-y

Cresswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Đerić, I., Malinić, D., and Đević, R. (2021). Project-based learning: challenges and implementation support. Problems Perspect. Contemp. Educ. 1, 52–73.

Elliott, V. (2018). Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. Qual. Rep. 23, 2850–2861. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3560

Eswaran, U. (2024). “Project-based learning: Fostering collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking,” in Enhancing education with intelligent systems and data-driven instruction, eds M. Bhatia and M. Tahir Mushtaq (Hershey, PA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 23–43. doi: 10.4018/979-8-3693-2169-0.ch002

Golzar, J., Noor, S., and Tajik, O. (2022). Convenience sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 1, 72–77. doi: 10.22034/ijels.2022.162981

Juuti, K., Lavonen, J., Salonen, V., Salmela-Aro, K., Schneider, B., and Krajcik, J. (2021). A teacher–researcher partnership for professional learning: Co-designing project-based learning units to increase student engagement in science classes. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 32, 625–641. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2021.1872207

Karan, E., and Brown, L. (2022). Enhancing student’s problem-solving skills through project-based learning. J. Problem Based Learn. High. Educ. 10, 74–87. doi: 10.5278/ojs.jpblhe.v10i1.6887

KT-Press Team. (2025). Mathematics and physics are the worst performed subjects in national exams. Kigali: KT-PRESS.

Mbarushimana, N., and Kuboja, J. M. (2016). A paradigm shift towards competence-based curriculum: The experience of Rwanda. Saudi J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 1, 6–17. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2102.5764

McGibbon, C., and Van Belle, J.-P. (2015). Integrating environmental sustainability issues into the curriculum through problem-based and project-based learning: A case study at the University of Cape Town. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainabil. 16, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.013

Meng, N., Dong, Y., Roehrs, D., and Luan, L. (2023). Tackle implementation challenges in project-based learning: A survey study of PBL e-learning platforms. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 71, 1179–1207. doi: 10.1007/s11423-023-10202-7

Mezmir, E. A. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: An overview of data reduction, data display, and interpretation. Res. Humanities Soc. Sci. 10, 15–27. doi: 10.7176/RHSS/10-21-02

Miller, E. C., and Krajcik, J. S. (2019). Promoting deep learning through project-based learning: A design problem. Disciplinary Interdisciplinary Sci. Educ. Res. 1:7. doi: 10.1186/s43031-019-0009-6

Morrison, J., Frost, J., Gotch, C., McDuffie, A. R., Austin, B., and French, B. (2021). Teachers’ role in students’ learning at a project-based STEM high school: Implications for teacher education. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 19, 1103–1123. doi: 10.1007/s10763-020-10108-3

Muchira, J. M., Morris, R. J., Wawire, B. A., and Oh, C. (2023). Implementing competency based curriculum (CBC) in Kenya: Challenges and lessons from South Korea and USA. J. Educ. Learn. 12, 62–77. doi: 10.5539/jel.v12n3p62

Mutanga, M. B. (2024). Students’ perspectives and experiences in project-based learning: A qualitative study. Trends High. Educ. 3, 903–911. doi: 10.3390/higheredu3040052

Nkundabakura, P., Nsengimana, T., Uwamariya, E., Nyirahabimana, P., Nkurunziza, J. B., Mukamwambali, C., et al. (2024). Contribution of continuous professional development (CPD) Training programme on rwandan secondary school mathematics and science teachers’ pedagogical, technological, and content knowledge. Educ. Information Technol. 29, 4969–4999. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11992-2

Nsengimana, Mugabo, L. R., Ozawa, H., and Nkundabakura, P. (2021). Science competence-based curriculum implementation in Rwanda: A multiple case study of the relationship between a school’s profile of implementation and its capacity to innovate. Afr. J. Res. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 25, 38–51. doi: 10.1080/18117295.2021.1888020

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2023). Report of the programme for international student assessment (PISA 2023). Paris: OECD.

Oribhabor, C. B., and Anyanwu, C. A. (2019). Research sampling and sample size determination: A practical application. J. Educ. Res. 2, 47–57.

Otara, A., Uworwabayeho, A., Nzabalirwa, W., and Kayisenga, B. (2019). From ambition to practice: An analysis of teachers ’ attitude toward learner- centered pedagogy in public primary schools in Rwanda. SAGE Open 9, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/2158244018823467

Pan, G., Shankararaman, V., Koh, K., and Gan, S. (2021). Students’ evaluation of teaching in the project-based learning programme: An instrument and a development process. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 19:100501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100501

Rampin, R., and Rampin, V. (2021). Taguette: Open-source qualitative data analysis. J. Open Source Softw. 6:3522. doi: 10.21105/joss.03522

REB. (2015). Competence -based curriculum: summary of curriculum framework pre-primary to upper secondary. Kigali: REB.

Rehman, N., Huang, X., Batool, S., Andleeb, I., and Mahmood, A. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of project-based learning: a comprehensive meta-analysis of student achievement between 2010 and 2023. ASR: Chiang Mai University J. Soc. Sci. Human. 11, 1–26. doi: 10.12982/cmujasr.2024.015

Serin, H. (2019). Project based learning in mathematics context. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 5, 232–236. doi: 10.23918/ijsses.v5i3p232

Siregar, T. P. (2024). The effect of project-based learning method on understanding geometry concepts in secondary school students. Attractive Innov. Educ. J. 6, 302–310. doi: 10.51278/aj.v6i3.1545

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences, Vol. 48. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Swedberg, R. (2020). Exploratory research. Production Knowledge Enhancing Progr. Soc. Sci. 2, 17–41.

Syamsuddin, S., Tahir, M., Idris, I., Efendi, E., Asrianti, A., and Gazali, G. (2025). Transformative learning through project-based learning: Enhancing student engagement and creativity in writing. J. Edusci. 12, 660–671. doi: 10.36987/jes.v12i3.6828

Twahirwa, J. N., Ntivuguruzwa, C., Twizeyimana, E., and Shyiramunda, T. (2021). Effect of project-based learning: Learners’ conceptualization and achievement in science education. Afr. J. Educ. Stud. Math. Sci. 17, 17–35. doi: 10.4314/ajesms.v17i1.2

Ukobizaba, F., Maniraho, J. F., and Uworwabayeho, A. (2025). Lesson observation tool for project-based learning: A useful tool for learner-centered pedagogy enhancement. Front. Educ. 10:1623269. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1623269

Ukobizaba, F., Ndihokubwayo, K., and Uworwabayeho, A. (2020). Teachers’ behaviours towards vital interactions that attract students’ interest to learn mathematics and career development. Afr. J. Educ. Stud. Math. Sci. 16, 85–93. doi: 10.4314/ajesms.v16i1.7

Viro, E., Lehtonen, D., Joutsenlahti, J., and Tahvanainen, V. (2020). Teachers’ perspectives on project-based learning in mathematics and sciences. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 8, 12–31. doi: 10.30935/scimath/9544

Williamson, E. (2023). The effectiveness of project-based learning in developing critical thinking skills among high school students. Eur. J. Educ. 1, 1–11.

Keywords: Competence-Based Curriculum, Grade Five, mathematics, project-based learning, teachers’ insights

Citation: Ukobizaba F, Maniraho JF and Uworwabayeho A (2025) Exploring mathematics teachers’ insights and practices of project-based learning in primary schools of Nyamasheke district, Rwanda. Front. Educ. 10:1709849. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1709849

Received: 21 September 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Álvaro Nolla, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Widodo Winarso, Universitas Islam Negeri Siber Syekh Nurjati Cirebon, IndonesiaNiroj Dahal, Kathmandu University School of Education, Nepal

Gelar Dwirahayu, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Ukobizaba, Maniraho and Uworwabayeho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fidele Ukobizaba, dWtvYmlmaWRlbGVAZ21haWwuY29t

Fidele Ukobizaba

Fidele Ukobizaba Jean Francois Maniraho2

Jean Francois Maniraho2