- 1Department of Science Technology and Vocational Education, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Department of Mathematics, Universitetet i Bergen, Bergen, Norway

This study examined the impact of a GeoGebra-supported problem-based learning (GSPBL) intervention on in-service primary mathematics teachers’ understanding of three-dimensional (3D) geometry. Ninety-two teachers from a Core Primary Teachers’ College in Western Uganda participated, selected through purposive sampling. An explanatory sequential mixed methods design combined a pre-test-post-test control group experiment with instructional observations. A paired samples t-test showed that the experimental group’s post-test scores were, on average, 4.72 points higher than their pre-test scores (t = −6.565, df = 45, p < 0.001). An independent samples t-test (Welch’s correction) also revealed a significant post-test difference between groups, with the experimental group outperforming the control by 2.53 points [t = 3.780, df = 70.20, p < 0.001, 95% CI (1.20, 3.86)]. Observation data supported these results, indicating greater engagement, collaboration, visualization, and application of geometric concepts. The study concluded that GSPBL significantly improved teachers’ understanding of 3D geometry compared to traditional methods. The findings highlight the potential of technology-enhanced instruction to strengthen mathematics education. For in-service primary mathematics teachers, GSPBL offers an effective approach to developing mathematics conceptual understanding. For researchers, it provides evidence of the pedagogical value of GeoGebra as a dynamic geometry tool, and for policymakers, it underscores the need to integrate GSPBL into teacher education, enhance digital infrastructure, and support continuous professional development in technology-supported pedagogy.

1 Introduction

Students should develop complex, abstract, and powerful mathematical structures to solve a wide variety of meaningful problems effectively (Abdullah et al., 2010). Achieving this goal requires teachers, particularly at the primary level, to possess contemporary skills and competencies that enable effective instruction (Pamenan et al., 2022). Research highlights that the quality of mathematics teaching is pivotal in fostering students’ development of these competencies (Jawawi et al., 2016). Studies such as Lehiste (2015) and Hursen (2021) have emphasised the importance of preparing teachers to design instruction aligned with technology and modern pedagogical approaches. Further, Bosica et al. (2021) argue that professional development in teaching strategies is essential. However, they note that direct instruction remains a dominant practice in mathematics teacher education. This trend is particularly pronounced in Uganda’s primary teacher education, where traditional, lecture-based approaches are still heavily relied upon (Muganga and Ssenkusu, 2019). Such approaches often limit learners’ opportunities to construct meaning and understand mathematical concepts beyond theoretical contexts, leaving higher-order competencies underdeveloped (Magpantay and Pasia, 2022).

The integration of digital tools such as GeoGebra into pedagogical models like Problem-Based Learning (PBL) has the potential to address these challenges. GeoGebra provides dynamic visualization, immediate feedback, and opportunities for interactive exploration, which align well with PBL’s emphasis on inquiry, collaboration, and problem-solving. Compared to other mathematics software, GeoGebra offers a freely accessible, cross-platform environment that supports both algebraic and geometric representations simultaneously, making it particularly effective for developing spatial reasoning and conceptual understanding in geometry (Birgin and Topuz, 2021). When combined with PBL, GeoGebra enables learners to explore real-world mathematical problems through guided discovery, thus fostering deeper understanding and engagement. Whilst previous studies have demonstrated GeoGebra’s value in teaching various topics such as translation (Selvy et al., 2020), two-dimensional geometry (Suratno, 2016), and three-dimensional geometry (Darhim et al., 2019), the majority of these studies have employed GeoGebra in isolation rather than in conjunction with PBL (Shadaan and Eu, 2013; Batiibwe, 2024). The current study, therefore, extends this body of work by investigating the synergistic effect of integrating GeoGebra with PBL, referred to here as GeoGebra-Supported Problem-Based Learning (GSPBL).

Specifically, there is limited empirical research exploring how GSPBL influences in-service primary mathematics teachers’ (IPMTs) understanding of three-dimensional geometry, particularly in contexts with minimal exposure to educational technology, such as Uganda. Moreover, the role of adult learning principles (andragogy) and socio-cultural mediation of tools (activity theory) in shaping such interventions has not been sufficiently examined. To counteract passive learning habits, Loc et al. (2022) underscore the need for innovative teaching methods. The professional competencies of teachers are strongly tied to the training they receive during their pre-service education (Hursen, 2021). Despite this, many primary mathematics teachers in Uganda lack sufficient technological knowledge and continue to rely on teacher-centred methods (Ssemugenyi, 2023). These methods prioritise factual knowledge and memorisation, failing to inspire imagination and higher-order thinking (Lessani et al., 2017). Furthermore, such practices primarily assess lower-order skills, offering little opportunity for the application of knowledge in real-world contexts (Selvy et al., 2020).

Engaging learners in meaningful mathematical discussions, where all students contribute actively whilst maintaining conceptual focus, remains a challenge for many teachers (Pourdavood and Song, 2021). Additionally, tensions exist between the teaching practices advocated in teacher education programs in Uganda (Kibirige, 2023) and the realities faced in classrooms, resulting in a disconnect between institutional learning and classroom practice (Klegeris and Hurren, 2022). Hence, the significance of this study lies in its examination of GeoGebra-Supported Problem-Based Learning (GSPBL) as an approach that promotes active, reflective, and technology-enhanced mathematical thinking. By focusing on in-service primary mathematics teachers in Uganda, where empirical investigations into innovative teacher education practices are scarce, this study addresses a critical gap in both local and global research. It offers insights to inform reforms aimed at transitioning from teacher-centred instruction to technology-supported, problem-based pedagogy. GSPBL has emerged as a promising approach for bridging this gap by immersing teachers in complex, real-world mathematical problem-solving contexts (Halai and Tennant, 2016). Accordingly, this study investigated the impact of the GSPBL approach on in-service primary mathematics teachers’ understanding of three-dimensional geometry in Core Primary Teachers’ Colleges (CPTCs). Using GeoGebra software with problem-based learning strategies, the study sought to explore the following question: “What is the impact of the GSPBL approach on IPMTs’ understanding of 3-D geometry?” The study also tested the following hypotheses:

H0₁: There is no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test mean scores of the IPMTs in the experimental group.

H0₂: There is no significant difference between the post-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups.

2 Literature review

2.1 Overview of GSPBL

The GSPBL approach integrates PBL with GeoGebra software to enhance learners’ engagement, understanding, and problem-solving abilities in mathematics (Selvy et al., 2020). GeoGebra, developed by Markus Hohenwarter in 2001, is a free, dynamic mathematical software that combines geometry, algebra, statistics, and calculus in a single interactive platform (Thapa et al., 2022). It allows learners to visualise, create, and manipulate mathematical objects in real time, making abstract concepts more concrete and accessible (Putra et al., 2021). GeoGebra’s 3D environment enables rotation, translation, and zooming of geometric figures (Pentang and Cuanan, 2022), thereby improving spatial reasoning and mental rotation skills (Ziatdinov and Valles, 2022). By enabling real-time exploration of multiple perspectives and cross-sections of solids, it helps bridge the gap between two-dimensional representations and the conceptualisation of three-dimensional structures (Septian et al., 2019; Wassie and Zergaw, 2019; Tamam and Dasari, 2021).

Despite these advantages, research indicates that many teachers and students continue to experience challenges in visualising and conceptualising 3D geometry, often leading to misconceptions and low achievement (Topraklikoglu and Ozturk, 2021). In Uganda’s primary schools, for instance, traditional instructional approaches that prioritise rote learning and factual recall over exploration and reasoning persist (Batiibwe, 2024; Adolphus, 2015). These practices limit opportunities for learners to develop spatial reasoning and conceptual understanding. Consequently, there is a need to retool in-service primary mathematics teachers (IPMTs) with innovative, technology-supported pedagogies such as GSPBL that promote active learning, collaboration, and conceptual exploration. This is particularly crucial given the real-world relevance of 3D geometry in fields such as architecture, engineering, and computer graphics (Che Ku et al., 2023), where spatial thinking and problem-solving skills are foundational for success in STEM disciplines.

The PBL model provides the pedagogical foundation for GSPBL. Originally developed at McMaster University in the 1960s (Martin, 2022), PBL is a student-centred approach in which learners acquire knowledge and skills by addressing authentic, real-world problems (Amini and Helsa, 2019). Hmelo-silver and Barrows (2006) identified six defining characteristics of PBL: student-centred learning, collaborative group work, facilitator guidance, authentic problem contexts, problem-driven inquiry, and self-directed knowledge acquisition. Compared to related pedagogies such as Constructivism and Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL), PBL offers a more structured framework for learning through complex, ill-structured problems. Whilst Constructivism provides the philosophical foundation for active knowledge construction (Thapa et al., 2022), and IBL promotes exploration through questioning (Eshetu et al., 2022), PBL uniquely integrates authentic problem-solving, collaboration, and self-directed inquiry as drivers of conceptual and applied understanding (Yurniwati and Utomo, 2020; Febriza et al., 2021; Poonsawad et al., 2022).

These features make PBL an ideal complement to GeoGebra’s dynamic environment. GeoGebra supports visual reasoning and model construction (Ziatdinov and Valles, 2022), whilst PBL structures the learning process around real-world problems that require learners to apply, test, and refine their mathematical understanding (Bosica et al., 2021). When integrated, GSPBL enables learners to visualise and manipulate geometric objects, generate hypotheses, conduct investigations, and collaboratively reflect on solutions to contextually relevant problems (Suratno, 2016). Thus, GSPBL represents a synergy between technology-enhanced visualization and problem-oriented pedagogy, positioning learners as active constructors of mathematical meaning (Saputro, 2023). This study, therefore, defines GSPBL as an instructional approach that integrates GeoGebra with PBL to engage in-service primary mathematics teachers in exploring, analysing, and solving real-world problems in 3D geometry. Through this approach, IPMTs collaboratively construct knowledge, develop spatial reasoning, and enhance their pedagogical skills for facilitating inquiry-driven geometry instruction.

2.2 The impact of using GSPBL

A growing body of research highlights the pedagogical benefits of GSPBL, including improvements in learners’ critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, collaboration, communication, and overall academic performance (Darhim et al., 2019; Selvy et al., 2020; Martin and Jamieson-Proctor, 2022). GSPBL fosters critical thinking by engaging learners in open-ended mathematical problems that require evidence-based reasoning and reflective judgment (Aini et al., 2019; Magpantay and Pasia, 2022). Studies such as (Putra et al., 2021) show that using GeoGebra in geometry enhances truth-seeking, open-mindedness, and self-confidence among learners. Pre-service and in-service teachers likewise benefit by learning how to design and implement cognitively challenging problem-solving tasks (Hannula, 2019; Suryanti et al., 2022). Research also indicates that GSPBL enhances problem-solving and reasoning skills by immersing learners in authentic contexts that demand systematic exploration and application of mathematical concepts (Mensah et al., 2022; Yaniawati et al., 2019). Likewise, creative thinking is promoted as learners explore multiple solution paths, formulate hypotheses, and develop original strategies (Darhim et al., 2019; Selvy et al., 2020). Moreover, GSPBL supports collaboration and communication, as learners work in teams to share ideas, test hypotheses, and co-construct solutions (Chaidam and Poonputta, 2022; Ramadhani and Umam, 2019; Sefa and Darko, 2023). These interactions cultivate communication, cooperation, and reflection, key competencies for effective teaching and lifelong learning (Bosica et al., 2021; Suryanti et al., 2023).

Empirical studies further show that integrating GeoGebra with PBL enhances academic achievement compared to traditional approaches. For example, students taught through GeoGebra-assisted PBL achieved significantly higher post-test scores and stronger problem-solving abilities than those taught via lecture-based instruction (Septian et al., 2019; Eshetu et al., 2022). Similarly, GeoGebra-assisted PBL improved prospective teachers’ mathematics content knowledge more effectively than PBL without GeoGebra (Darhim et al., 2019). These findings collectively suggest that GSPBL supports conceptual understanding and skill development more effectively than conventional methods. Despite these positive outcomes, significant gaps remain in the literature. Contextually, few studies have examined GSPBL among IPMTs in CPTCs in Uganda, where digital integration in teacher education remains minimal. Conceptually, prior research has typically examined GeoGebra and PBL in isolation, overlooking the pedagogical synergy between technology and inquiry-driven learning. Methodologically, most studies have adopted either quantitative or qualitative designs, with limited use of mixed-methods approaches that capture both statistical impacts and pedagogical processes. Theoretically, existing studies predominantly rely on constructivist perspectives, with limited application of Activity Theory and Andragogy, which are essential for understanding tool-mediated learning and adult professional development. Addressing these gaps, the present study investigates the impact of GSPBL on IPMTs’ understanding of 3D geometry within Uganda’s CPTCs, employing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design grounded in Activity Theory and Andragogic principles.

2.3 Justification for focusing on the IPMTs’ 3D understanding

The central focus of this study is on IPMTs’ understanding of 3D geometry as influenced by the GSPBL approach. We selected 3D geometry understanding as the dependent variable because the ultimate aim of mathematics teacher education is to strengthen teachers’ subject matter knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge in ways that directly impact classroom practice. The critical educational outcome is whether technology-supported pedagogies foster improved conceptual understanding of mathematics content, particularly in 3D geometry. This area remains challenging for both teachers and learners, as it demands spatial reasoning, visualisation, and abstraction, skills with which many teachers struggle. By focusing on 3D geometry understanding, this study addresses a core issue of content mastery and pedagogical preparedness. Thus, evaluating the impact of GSPBL on this construct ensures that the findings contribute meaningfully to professional development, curriculum innovation, and teacher education policy.

2.4 Theoretical framework

This study was underpinned by two complementary theoretical lenses, including the Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) and Knowles’s theory of Andragogy (KTA). Together, these frameworks provided a robust foundation for examining the pedagogical and cognitive dimensions of the GSPBL approach in the context of IPMTs, particularly in relation to 3D geometry concepts.

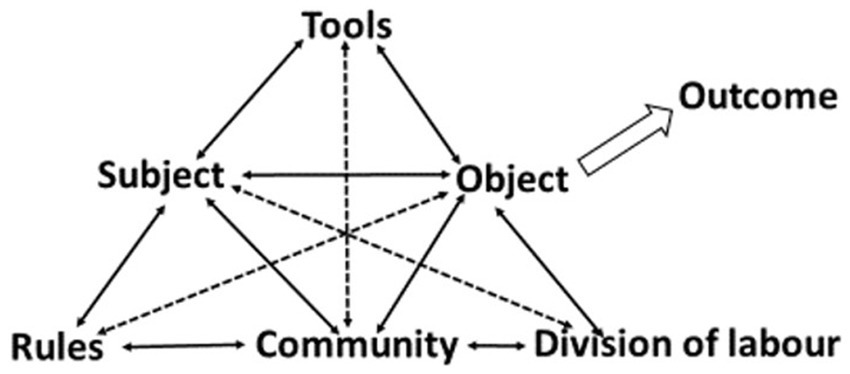

First, emphasis is placed on the importance of active student participation in enhancing learning outcomes (Agustin et al., 2020). First, the study is grounded in the Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) as a theoretical framework, which asserts that all intentional human actions are goal-directed and mediated by tools (Golding and Batiibwe, 2021). Jaworski et al. (2007) define “activity” as participant engagement during practice, highlighting the theory’s focus on the complexity of social contexts, community norms, and role divisions (Loc et al., 2022). This framework helps students comprehend, engage in, and transform their learning activities (Karasavvidis, 2022).

Originating from Vygotsky, CHAT comprises a subject, object, and tool, later expanded by Leont’ev to include the community and the division of labour (Jaworski et al., 2007). Leont’ev stressed that actions gain meaning in the context of collective activity, with social norms (rules) influencing interactions (Jaworski et al., 2007). Engeström further refined the model to illustrate the complexity of activity systems better (Laforce et al., 2017; Jaworski et al., 2007). In the current study, the subjects are the IPMTs who engaged in solving real-world 3D geometry problems. The object is to deepen their understanding of 3D geometry. GeoGebra serves as the mediating tool, facilitating the visualisation and manipulation of shapes (Selvy et al., 2020). The community consists of small collaborative groups of IPMTs, promoting active engagement. The division of labour involves shared and rotating roles, like chairperson or presenter, to ensure balanced participation (Anthony and Anthony, 2014). Finally, rules include both formal and informal guidelines that support respectful communication, independent problem-solving, and reflection. These elements of CHAT collectively guided the IPMTs’ learning experience, emphasising structured collaboration, accountability, and meaningful engagement with geometry content (Figure 1).

Second, Knowles’s theory of andragogy (KTA) outlines principles of adult learning that differentiate it from child learning, making it a suitable framework for understanding the learning behaviours of IPMTs. This study applies Knowles’s principles to examine how the GSPBL approach enhances IPMTs’ understanding of 3D geometry concepts. A key tenet of andragogy, self-direction, aligns with the problem-based learning aspect of GSPBL, which promotes autonomy by engaging IPMTs in open-ended, spatially complex problems. Through these tasks, IPMTs took initiative in solving problems using GeoGebra as a tool for exploration and problem-solving. This enabled them to independently formulate questions, test hypotheses, and reflect on spatial relationships in 3D geometry. Another principle, the use of prior experience as a learning resource, was evident as IPMTs drew on their own classroom experiences, both as learners and novice teachers, to contextualise new geometric concepts. Knowles also emphasises the importance of understanding the rationale behind learning. In the study, this was addressed by situating 3D geometry tasks within real-world contexts, making the content relevant and applicable. Readiness to learn was supported by tailoring tasks to match the curriculum IPMTs were expected to teach, enhancing immediate relevance and engagement. Furthermore, the pragmatic orientation of adult learners was addressed through the hands-on use of GeoGebra for modelling real-world 3D problems, which facilitated direct application of new skills in teaching. IPMTs also developed dynamic visualisations and interactive tasks for primary students, reinforcing GeoGebra’s practical value. Finally, the study catered to IPMTs’ internal motivation by designing tasks that were both personally meaningful and professionally applicable, encouraging reflection and ongoing improvement in their pedagogical practices (Figure 2).

3 Methodology

3.1 Research approach and design

The study utilised a mixed methods approach (Sileyew, 2019), incorporating a pre-test post-test control group design for the quantitative phase and a case study design for the qualitative phase (Creswell, 2014). The pre-test post-test control group design was selected to examine the differences in the pre-test and post-test scores within the Experimental group (EG) and to compare the test scores of the EG with those of the control group (CG). The case study design was employed because the intervention specifically targeted a group of IPMTs, allowing for an in-depth exploration of the GSPBL intervention’s impact on their understanding of 3D geometry.

3.2 Study population and sampling strategies

The study was conducted at one of Uganda’s 23 Core Primary Teachers’ Colleges (CPTCs), institutions that prepare primary school teachers to upgrade their academic and professional skills to the diploma level. The college had a population of 345 in-service primary teachers, with 214 in the first year and 131 in their second year. A two-stage sampling technique was used to select participants. First, homogeneous purposive sampling was applied to select 92 first-year in-service teachers who were pursuing mathematics education as one of their two subjects. First-year participants were chosen because 3D geometry is covered in the first semester, first year of the CPTC curriculum. According to Fraenkel et al. (2012), purposive sampling is appropriate when the researchers believe that specific conditions will yield useful data. All IPMTs consented to participate in the study, to be video-recorded, and were randomly assigned to either the EG or CG using simple random sampling. Each group initially consisted of 46 IPMTs; however, two EG participants and three CG participants did not complete the study. Consequently, 44 IPMTs from EG and 43 from the CG completed the post-test. The college was selected purposively from among the 23 Core Primary Teachers’ Colleges in Uganda. The selection was based on three main criteria. First, it had the largest number of IPMTs, which was essential for conducting a mixed-methods study that required both quantitative and qualitative data. Second, it possessed a relatively higher number of functional computers (15 in total) compared to the other CPTCs, thereby facilitating the integration of GeoGebra tools in the intervention. Therefore, we used purposive sampling appropriate, as it allowed the researchers to select a case that is information-rich and relevant to the purpose of the study.

3.3 Data collection methods and tools

The selection of data collection methods and tools was guided by CHAT and Knowles’s principles of Andragogy. First, the spatial ability test aligns with CHAT’s emphasis on mediated learning through the GeoGebra tools, capturing cognitive transformation resulting from tool-supported engagement. Observations were informed by the socio-cultural dimension of Activity Theory, focusing on interactions within the learning environment. Additionally, both the test and observational tools reflect Andragogy’s focus on adult learners’ self-direction and experiential learning. By assessing performance and engagement in authentic problem-solving contexts, the instruments captured outcomes and the processes central to adult learning and activity-based instruction. A pre-test-post-test control group experiment was employed to collect quantitative data, whilst lesson observations were used to obtain qualitative data for this study, which investigated the impact of the GSPBL approach on understanding 3D geometry. A pre-test was given to both the experimental group and the control group before instruction to assess the baseline knowledge of the IPMTs in 3D geometry. Following instruction using GSPBL for the EG and traditional approaches for the CG, a post-test was administered to evaluate the impact of GSPBL on the IPMTs’ understanding of 3D geometry compared to the traditional approach. This two-step testing approach provided insights into the significant changes brought about by the learning methods (Creswell, 2014).

Quantitative data were collected through tests, whilst qualitative data were obtained using an observation tool (the link to the test, its marking rubric, marking guide, and observation tool have been provided at the end of this manuscript, Journal Editor’s email, and is available online). The tests included a pre-test and a post-test with identical items, designed by the researchers to assess the same competencies. The test consisted of four 3D geometry-related scenarios, each containing five problems. To ensure validity, the test was reviewed by three experts in mathematics education for primary teacher training. The scale of content validity index (S-CVI) across all items was 0.956, indicating that, on average, 96% of the ratings were deemed relevant by the majority of the experts. This result confirmed that the test was well-designed, covering the intended content effectively. Additionally, a pilot test involving 20 IPMTs from a different college was conducted to assess the test’s internal consistency. The test–retest reliability score of 0.82 (where α ≥ 0.7) demonstrated strong stability, further supporting its reliability.

We employed an observation tool to collect qualitative data. Lesson observations for both the EG and the CG were conducted, with notes taken using the observation tool by one of the researchers. Additionally, a video camera was used to record the lesson proceedings. This approach enabled re-examination of the lessons, provided flexibility in analysis, and helped reduce observer bias. The observation tool consisted of 10 open-ended questions designed to focus on the IPMTs’ engagement strategies in solving real-world problems. To ensure content validity, the tool was reviewed by two expert lecturers in pedagogical practices. The raters’ evaluations were analysed using Cohen’s Kappa (k), yielding a k-value of 0.87 (where k ≥ 0.70). This result confirmed that the observation tool was both valid and reliable for capturing the constructs. The high level of agreement between the raters enhanced confidence in the validity of the conclusions drawn from the observations, as there was minimal variation in their evaluations.

3.4 Data analysis

3.4.1 Quantitative data

Before the pre-test, demographic information, which included age, gender, prior ICT experience, teaching experience, and academic qualification of participants, was collected. This information was used to assess baseline equivalence between the experimental and control groups, thereby helping to control for potential confounding variables. The pre-test ensured that both groups were comparable before the intervention, minimizing the impact of extraneous factors such as instructional time and prior experience.

Using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0, quantitative data from survey and tests were analysed using percentages, descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics were employed to compute the mean, standard deviations, and standard errors for the pre-test and post-test scores of the EG and CG. Additionally, we conducted paired samples and independent samples t-tests to compare mean scores. The paired samples t-test assessed the statistical significance of the difference between pre-test and post-test scores within the EG. Meanwhile, the independent samples t-test evaluated the statistical significance of the difference between the post-test scores of the EG and CG. To examine the variance between the groups, we calculated the F-value using Welch’s test for Equality of Variances. This test was instrumental in determining whether the assumption of equal variances was valid (Şenyiğit, 2021). To assess the practical significance of the observed differences in mean scores, the effect size was computed using Cohen’s d formula and was interpreted based on Cohen’s (1988) interpretive framework of 0.00–0.19 for a negligible magnitude, 0.20–0.49 for a small magnitude, 0.50–0.79 signifies for a medium magnitude, 0.80–1.29 for a large magnitude and 1.30 and above for a very large magnitude.

3.4.2 Qualitative data

We conducted a thematic analysis of the observation notes and the video recordings. Initially, the notes were transcribed and systematically organised. Recurring patterns were identified and categorised, forming the basis for theme development. Related patterns were grouped into cohesive themes, which were then assigned specific codes. Finally, narratives were constructed based on these themes and triangulated findings from the quantitative study to ensure comprehensive insights.

3.5 Ethics

A week before data collection, the researchers briefed the participants on the study’s objectives and obtained their written informed consent. Participants were assured that their identities, as well as those of the CPTC, would remain anonymous at all times. It was also explained that the video recordings would be used exclusively by the researchers for data analysis and would be deleted afterwards. Each participant was assigned a unique code (P001-P092) and was referred to solely by this code. No monetary compensation was provided, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Both the experimental and control groups were taught by the same instructor to maintain consistency in instructional delivery and to ensure that differences in outcomes were attributable to the intervention rather than teaching style or competence. To minimize potential bias, the instructor adhered to standardized lesson plans and instructional procedures developed for the study (Fraenkel et al., 2012). This approach aligns with best practices in experimental research where instructor-related variables are controlled by standardization (William, 2011).

3.6 The implementation process

The six-week study conducted at a CPTC aimed to investigate the impact of the GSPBL approach on IPMTs’ understanding of 3-D geometry. The EG was taught using the GSPBL approach whilst the CG was taught using traditional methods. Both groups received instruction from the researchers, with lessons held twice a week, lasting 2 h per session for each group, totalling 4 h per week. The study began with a pre-test in the first week, which was marked and used to randomly assign participants to the EG and CG. Instruction occurred during the second through fifth weeks, and a post-test was administered to both groups in the sixth week in a shared setting. Observations were conducted during instruction to capture real-time behaviours, collaboration, task engagement, and responses of the IPMTs. Two distinct lesson plans, one for EG and another for CG, were developed based on the Year 1, Semester 1, Mathematics Education curriculum. Topics included the surface areas and volumes of cubes and cuboids, cylinders, and pyramids.

3.6.1 The implementation process in the experimental group

In the EG, lessons incorporated activity sheets with real-life scenarios related to 3D geometry, designed by the researchers. To create these scenarios, the researchers first reviewed the literature on 3D geometry to identify the common patterns, processes, and misconceptions. They then aligned targeted learning outcomes with the Mathematics Education curriculum and developed scenarios accordingly. Each lesson included one scenario, focusing on ill-structured real-world problems requiring multiple solution processes. The scenarios underwent validation by two university mathematics education lecturers, who confirmed their appropriateness. They were then pilot-tested with 20 IPMTs from another college, grouped into fives. Feedback from the pilot test demonstrated the scenarios’ reliability, as participants engaged actively, collaborated effectively, and independently proposed alternative solutions. These tasks were intended to explore 3D geometry concepts such as surface areas and volumes. The GSPBL environment encouraged IPMTs to use GeoGebra, supported by researchers, to tackle authentic, real-world problems in small collaborative groups and individually.

Process activities included analysing the scenario, listing hypotheses, listing the known in the problem, listing the unknown, listing what needs to be done, gathering information/individuals doing research, sharing ideas within groups, presenting findings, and engaging in reflections and evaluation (Figure 3). The collaborative setup ensured that every group member played an active role, conducting individual research, sharing strategies, and providing peer support. GeoGebra, installed on all computers in the college lab, was a key tool in facilitating problem-solving for 3D geometry tasks. Each group had a chairperson and a secretary/presenter, with roles rotated across sessions. Groups established rules to ensure active participation, such as familiarising themselves with GeoGebra’s functionalities, respecting peers’ views, and taking turns speaking. After each lesson, groups designed a real-world problem for primary six students as a take-home assignment. These problems, written on manila cards and displayed for peer sharing, aimed to enhance the IPMTs’ ability to create authentic, meaningful problems related to 3D geometry for use in primary school contexts (Kanyesigye et al., 2022a,b).

3.6.2 The implementation process in the control group

In the CG, lessons were conducted in a conventional, teacher-centred approach, characterized by lecture and question-and-answer methods. Lessons were conducted in a standard classroom setting where the teacher researcher (TR) introduced 3D geometry concepts through direct verbal explanations, supported by chalkboard illustrations and step-by-step demonstrations. Content delivery focused on the procedural aspects of 3D geometry, specifically, the recall and application of formulas for calculating surface areas and volumes of 3D shapes, and worked through examples, which IPMTs copied. Assignments were given to reinforce learning, and desks were arranged in rows facing the chalkboard throughout the lessons. Instructional materials included the CPTC mathematics education module and a teacher-prepared chart containing 2D diagrams representing 3D shapes, key formulas, and practice exercises. Occasionally, 3D models, including paper boxes and plastic shapes, were used to demonstrate structural properties, and these were vertices, edges, and faces. Problem-solving was guided by worked examples that reinforced memorization of the procedural steps of solving 3D geometry problems. Interaction in CG was limited to answering oral questions or completing individual exercises. One researcher (TR) delivered the lesson, another one observed and recorded field notes, and a third videotaped the sessions for consistency monitoring. Problem-solving focused on formulas and memorised steps to solve lower-order 3D geometry problems. Textbooks with 3D diagrams, properties, and exercises were provided to support learning.

4 Findings

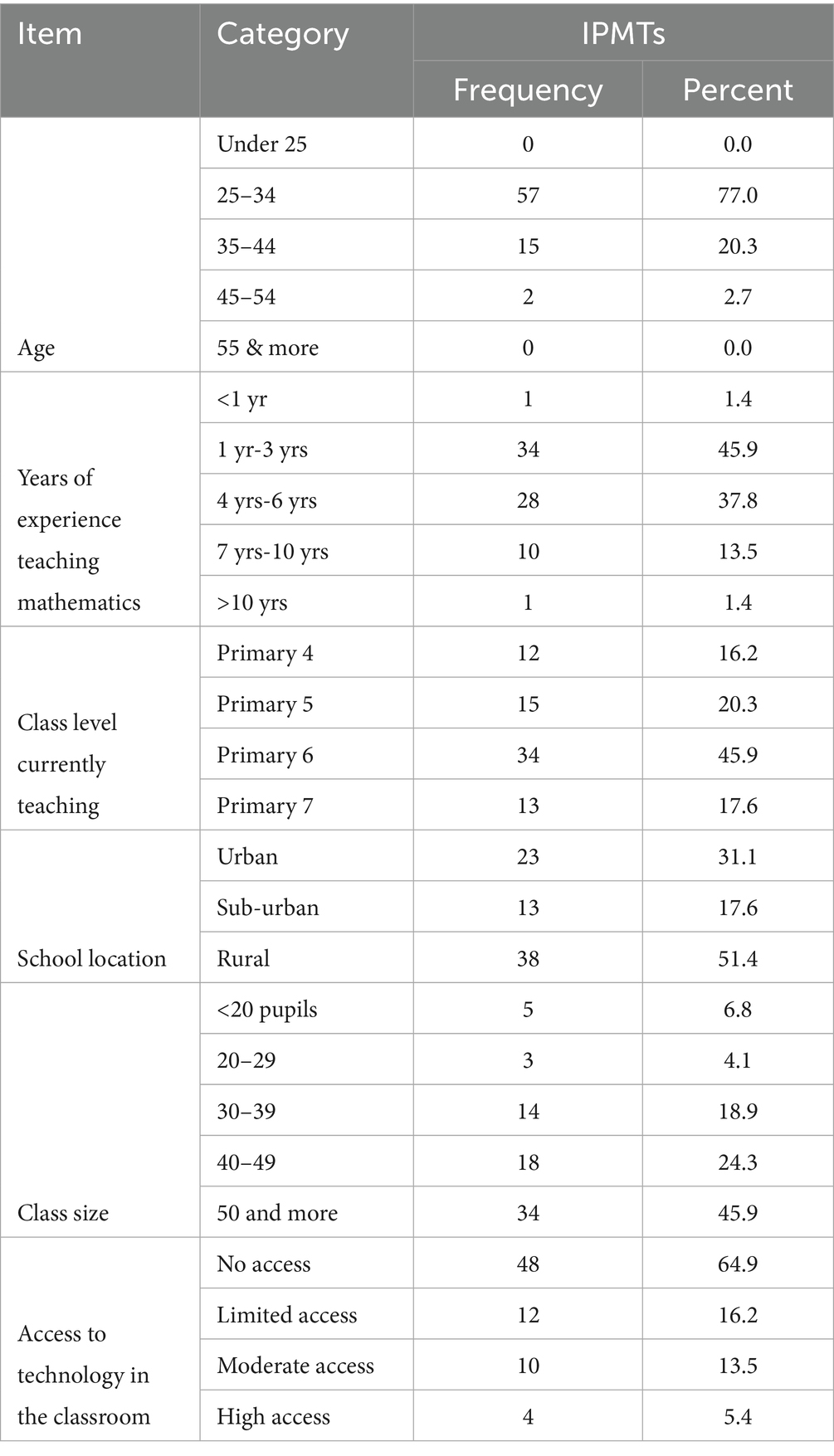

This section begins by presenting the demographic characteristics of the IPMTs who participated in the study. Data were collected on variables such as age range, years of experience teaching mathematics, class level currently taught, geographical location of the school, average class size, and access to technology in classrooms. All demographic questions were structured with multiple-choice options to ensure consistency and ease of analysis (Table 1). The findings of the study revealed key insights into the impact of the intervention. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and standard errors, as well as inferential statistics, including paired-samples and independent-samples t-tests, to determine statistical significance and effect size. In addition, qualitative observations of instruction for both the experimental group (EG) and the control group (CG) provided deeper insights into the IPMTs’ engagement with 3D geometry learning.

The results in Table 1 showed that the majority of participants were aged between 25 and 34 years (77.0%), had between 1 and 6 years of mathematics teaching experience (83.7%), and primarily taught upper primary classes (Primary 5–7). Over half (51.4%) of the participants taught in rural schools, with class sizes of 50 pupils or more for 45.9% of them. Most participants reported limited or no access to technology in their classrooms (81.1%). This demographic analysis provided a clear profile of the IPMTs and helped establish baseline equivalence between the experimental and control groups before the intervention. It also enabled the researchers to account for demographic factors that could influence learning outcomes (Fraenkel et al., 2012).

4.1 Comparison of the pre-test and post-test mean scores within the EG

A paired samples t-test was performed to compare the pre-test and post-test mean scores of IPMTs in the EG. This comparison of dependent samples was primarily conducted to test the first hypothesis. Results with more than two decimal places were rounded to two decimal places (2dp) for precision and clarity.

H01: There is no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test mean scores (𝜇𝑝𝑟𝑒=𝜇𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡) of the IPMTs in EG.

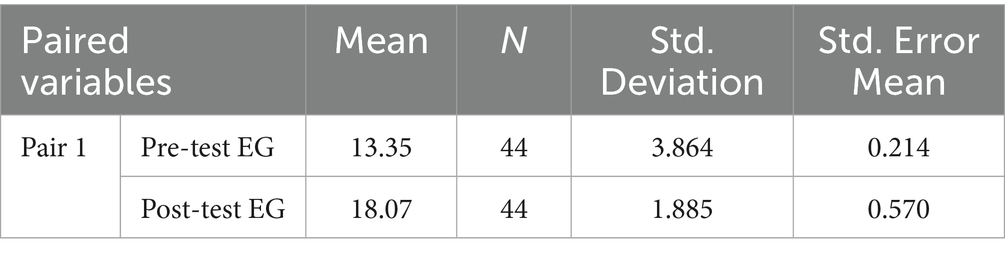

Table 2 presents the paired sample statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean for the two variables, pre-test EG and post-test EG. Before the intervention with GSPBL in 3D geometry instruction, the mean score was 13.35, with a standard deviation of 3.87. After the intervention, the mean score increased to 18.07, with a standard deviation of 1.89, suggesting significantly higher post-test scores and low variability. The standard errors for the pre-test and post-test were 0.21 and 0.57, respectively, highlighting the precision of the estimated mean values. The notable difference in mean scores indicates a substantial improvement in understanding 3D geometry from the pre-test to the post-test.

Table 3 presents the paired samples correlation between the pre-test and post-test scores of the EG, revealing a low and statistically nonsignificant correlation (r = 0.093, p = 0.537) between the two sets of scores. This weak correlation suggests that IPMTs’ performance on the pre-test did not strongly predict their outcomes on the post-test. In the context of the study, this may imply that the GSPBL approach effectively disrupted prior performance trends, enabling learners who may have initially struggled with 3D geometry to make significant progress. The absence of a significant correlation reinforces the idea that improvement was not limited to already high-performing individuals but rather occurred broadly across the group. This finding supports the equitable impact of GSPBL in enhancing the understanding of 3D geometry among IPMTs, regardless of their initial proficiency levels.

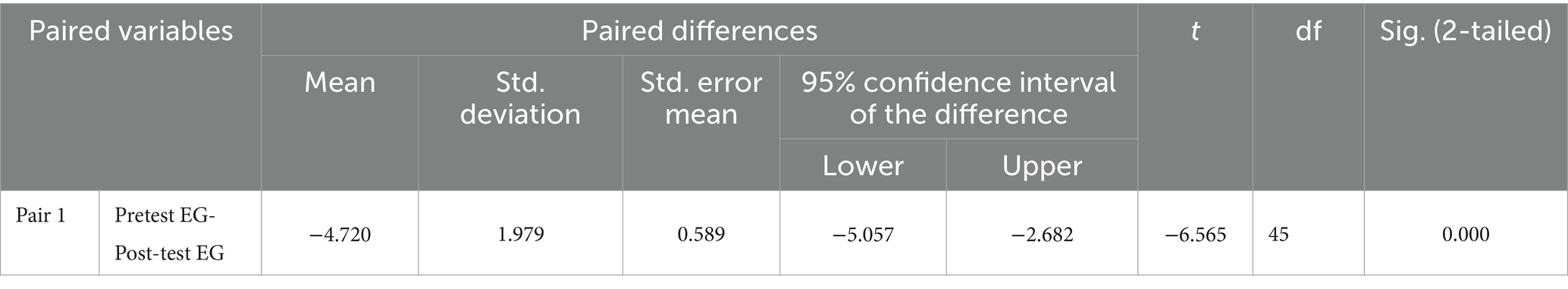

Table 4 presents the results of a paired samples t-test used to compare EG’s pre-test and post-test scores. The analysis yielded a statistically significant difference between the two assessments, with a t-value of −6.565 (df = 45, p < 0.001), indicating a highly significant improvement following the intervention. The mean difference of −4.720 (SD = 1.979) suggests that participants scored, on average, nearly five points higher on the post-test than on the pre-test. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference ranges from −5.057 to −2.682, excluding zero. This suggests that the true mean difference is likely to fall within this range, supporting the conclusion that the post-test scores were consistently higher than the pre-test scores. Consequently, the null hypothesis was confidently rejected, indicating that the observed difference in means is unlikely to be due to random variation. Given the direction and magnitude of this difference, it can be concluded that the GSPBL approach had a substantial positive impact on IPMTs’ understanding of 3D geometry. In addition to demonstrating statistical significance, we calculated the effect size to assess the practical significance of the observed differences in the EG’s pre-test and post-test mean scores. The effect size computed using Cohen’s d was 0.97. Based on Cohen’s (1988) interpretive framework, this reflected a notable and practically meaningful improvement in IPMTs’ performance following the intervention. The magnitude of this effect is acceptable and supported by Santhosh et al. (2024), whose study reported an average effect size of Cohen’s d as 0.913. This effect size suggests that the GSPBL approach had a clear and measurable impact on learning outcomes, fostering substantive academic gains within the EG.

4.2 Comparison of the post-test mean scores between the EG and the CG

An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the post-test mean scores of the EG and the CG. The objective was to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in performance between the two groups following the instruction of 3D geometry using GSPBL for the EG and traditional methods for the CG. Descriptive statistics and t-test results were presented to compare the post-test mean scores of the two groups.

H0₂: There is no significant difference between the post-test mean scores of the EG and CG (μ[post-EG] = μ[post-CG]).

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics for the EG and CG post-test scores as part of an independent samples t-test. The analysis aimed to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in performance between the two groups following instruction. The sample size (N) for EG during the post-test was 44, whilst the CG comprised 43 IPMTs. The results show that the EG, which received the GSPBL approach, achieved a higher mean score (M = 18.07, SD = 1.885) than the CG (M = 15.53, SD = 3.628). The relatively small standard deviation in the EG suggests more consistent performance among participants, whilst the larger standard deviation in the CG indicates greater variability in outcomes. The mean difference of approximately 2.54 points reflects a notable advantage for the EG, suggesting that the GSPBL approach may have contributed meaningfully to improved understanding of 3D geometry.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for the independent samples t-test on the post-test scores of EG and CG.

Table 5 presents the results of an independent samples t-test comparing the post-test scores of the Experimental Group (EG) and the Control Group (CG). Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances was significant (F = 7.515, p = 0.007), indicating that the assumption of equal variances was violated. Consequently, the interpretation is based on the “Equal variances not assumed” row (Welch’s t-test). The t-test revealed a statistically significant difference between the two groups, t(70.2) = 3.78, p < 0.001. The EG outperformed the CG by an average of 2.53 points (Mean Difference = 2.53, Standard Error = 0.67), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.20 to 3.86. This result indicates that the difference in mean scores between the groups is both statistically significant and practically meaningful. These findings suggest that the intervention implemented with the EG had a significant positive impact on participants’ performance, supporting its effectiveness in enhancing learning outcomes. In the context of the independent samples comparison, the calculated effect size of d = 0.80 indicates that the mean score of the EG exceeded that of the CG by 0.80 standard deviations. This represents a large effect, implying that the intervention produced not only statistically significant gains but also substantial educational improvements in participants’ understanding and performance (see Table 6).

4.3 Comparative analysis of the lesson observations during the intervention phase

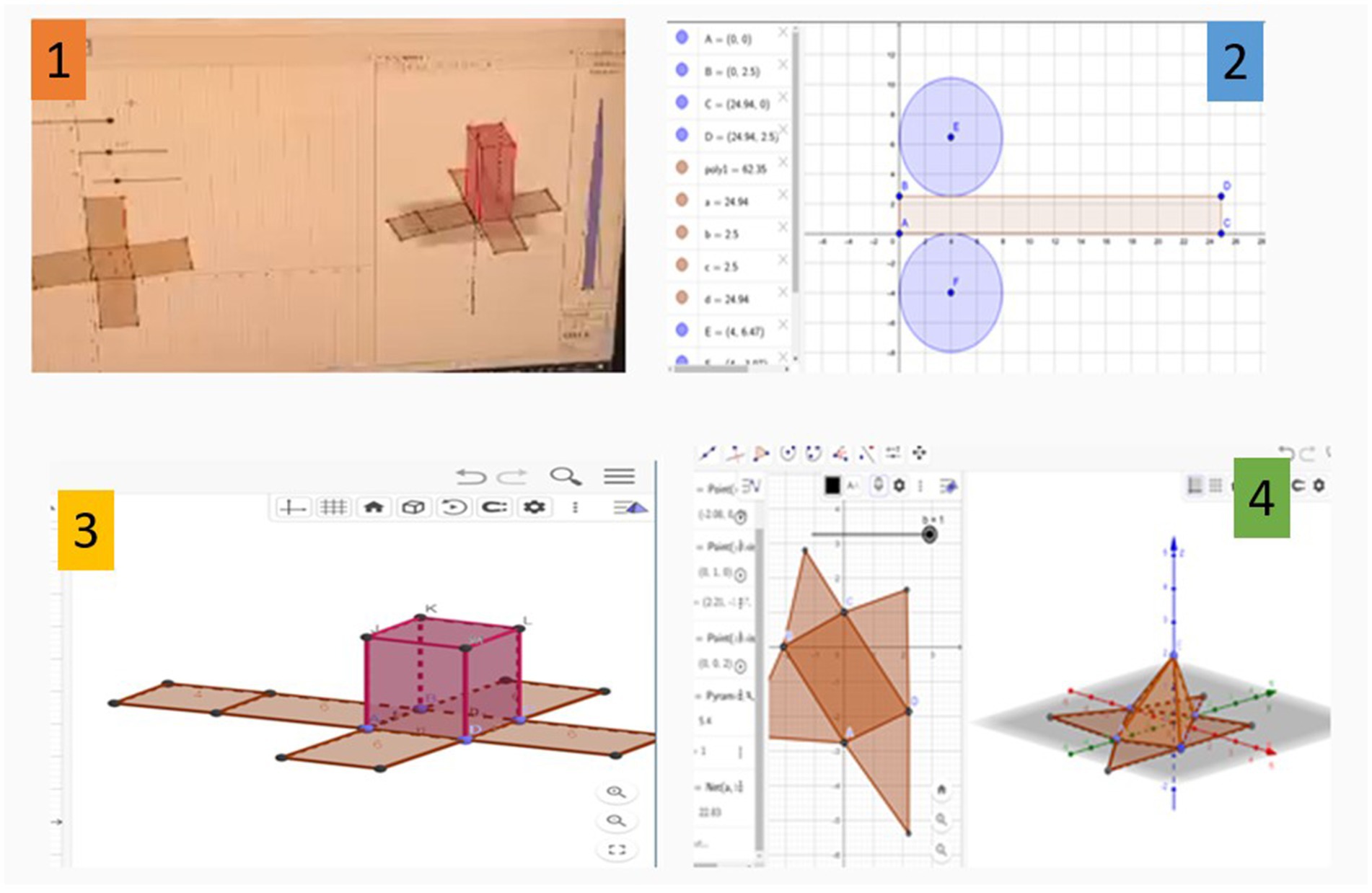

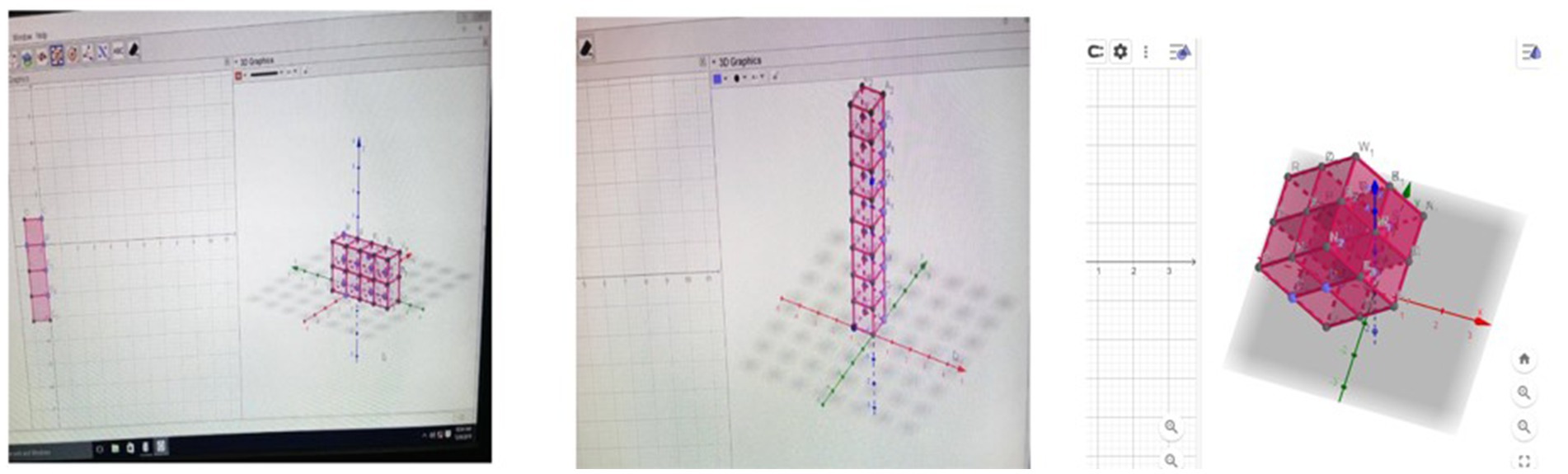

During the intervention phase, lesson observations were conducted in both the EG and CG, each comprising 46 IPMTs and taught identical 3D geometry content under comparable classroom conditions, which included similar class sizes (46 IPMTs in each group) and exposure to real-world problem scenarios. The groups differed mainly in pedagogy: the EG was taught using the GSPBL approach, whilst the CG received conventional traditional instruction. Six lessons (2, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 11) were observed in each group, all centred on real-life problem scenarios involving nets, surface areas, and volumes of cubes, cuboids, cylinders, and pyramids. In the EG, lessons were structured around collaborative group work, where learners brainstormed, conducted short research tasks, and shared insights. Their findings were synthesised by a group secretary and presented during plenary sessions for whole-class discussions. GeoGebra was integrated extensively, enabling learners to manipulate nets dynamically and connect physical and digital representations of 3D shapes. Conversely, the CG followed a teacher-led model, focusing on explanations, individual seatwork, and limited peer discussion, with minimal use of interactive tools. For example, in Lesson 2, both groups studied the construction of nets. Whilst the CG relied on paper-based explanations, the EG combined physical folding of nets with digital GeoGebra simulations, enhancing engagement and conceptual clarity (Figure 4).

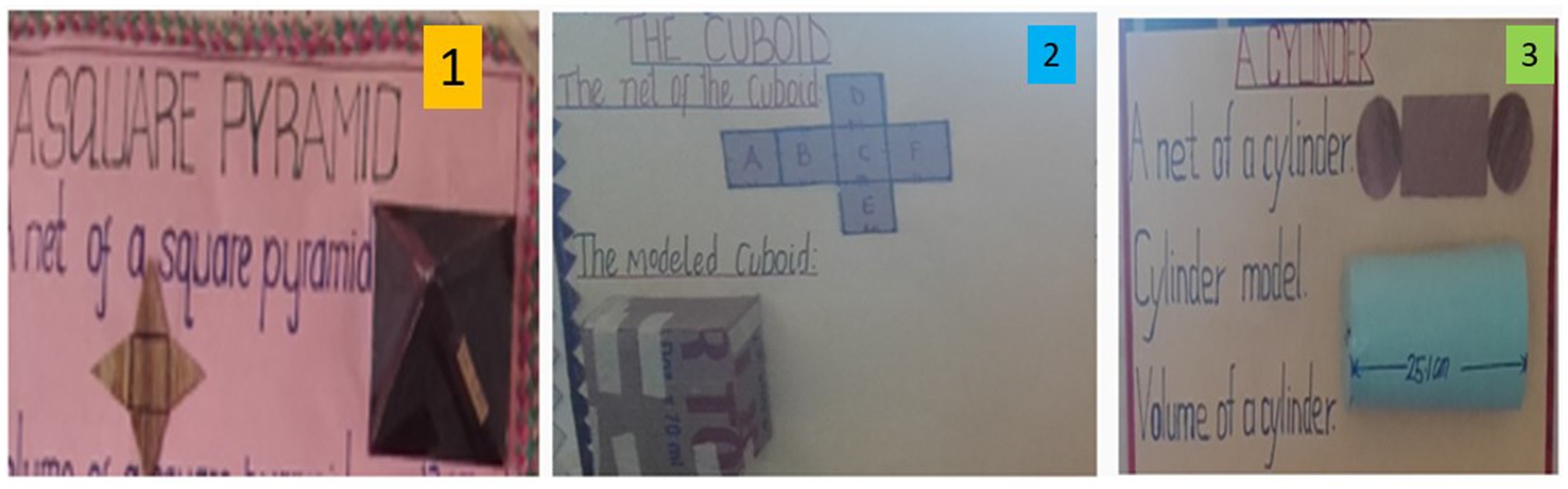

Figure 4 shows some of the 3D geometry shapes and their nets designed by the EG using GeoGebra software. Images 1 and 3 in the figure are nets of a cube, Image 2 is a net of a cylinder, and Image 4 is a net of a pyramid. IPMTs used slider tools to manipulate the dimensions of the shapes, and the sliding changed the dimensions proportionally on the 3D and the 2D worksheets. The CG designed nets using Manila cards and other locally available materials, but without the use of GeoGebra or other interactive digital tools (Figure 5).

In Figure 5, Images of 3D shapes and their nets designed by the CG are presented. Image 1 shows a square pyramid and its net, Image 2 is a net of a cube and a cuboid model, and Image 3 shows the net of a cylinder and the cylinder, as displayed by the CG.

In Lesson 3, IPMTs were oriented to a scenario that required them to explore the application of a cube and the net. “Grace, who was renting, built a house and needed to shift to her new house. She went out to Central Market to buy packaging materials in which she would pack her items orderly, without getting damaged. She has many items to pack, so she will need many of these packaging materials. What type of packaging material would you suggest Grace buy? Analyse the form in which the packaging material you have suggested will be carried from the market to the home. What reason do you have for your suggestion?”

The EG, in their small groups, discussed predicting the packaging material. P52 in G4 suggested boxes or paper boxes. P86 added that the shape of the box could be a cube or a cuboid, because they have three dimensions, which are the length, the width, and the height, for the shape of a cuboid and equal dimensions for the shape of a cube. P70 proposed paper bags and sacks, reasoning that one sack can carry a lot more items than a box. P52 responded to P70, saying, “Remember, we are suggesting to Grace to buy packaging materials that will not cause damage to her items, for example, if they are cups or plates, packing them in a sack will definitely damage them, do not you think so?” The G7 agreed on a cube or cuboid for packaging materials and discussed the most suitable form for transporting these materials from the market to the home. P15 suggested unfolding the boxes to be flat. P39 supplemented and said, “Oh! If Grace unfolds the boxes, then they will be nets of cubes or cuboids.” IPMTs in their small groups were guided to represent the form in which the packaging materials would be carried from the market on a GeoGebra worksheet. On the GeoGebra, groups visualised the possibility of carrying many boxes. P44 reasoned that when boxes are unfolded into nets, many can be packed together and carried by any means, including carrying them on the head.

The CG were introduced to the same problem scenario and were asked to brainstorm on the type of packaging materials they would propose to Grace to buy. IPMTs raised their hands and suggested paper boxes and sacks. Their reasoning for suggesting paper boxes and sacks was that they are light to carry from the market to the home. The characteristics of different packaging materials were explained, with particular attention given to boxes shaped as cubes and cuboids. It was clarified that cubes have equal dimensions, whilst cuboids have varying lengths, widths, and heights, making them more adaptable for different item sizes. The limitations of using sacks for fragile items were pointed out, and the advantages of rigid, structured containers were emphasised.

Following the demonstration, individual tasks on sheets of paper were assigned to IPMTs to investigate the different nets that can form cubes. A similar assignment was given to the EG, and they were encouraged to design the shapes on GeoGebra to explore which shapes can form cubes. The CG IPMTs copied the diagrams of cube and cuboid nets into notebooks, and dimensions were labelled. Worksheets were completed that included identifying nets and writing brief explanations about the suitability of boxes over sacks for packaging items.

In Lesson 5, IPMTs were given the scenario to investigate and compare the two shapes, the cylinder and the cuboid.

“A school wants to install a rainwater harvesting tank that can store up to 20,000 litres (20 m3) of water with a maximum height of 2metres and with a cuboidal base length of 3.16metres. Help to design two different tank shapes (cylinder, cuboid). Compare their volumes and surface areas. Recommend the most efficient design in terms of material use and replacement space. Which of the two would have less material cost?”

In Group (G) 5 of EG, Participant (P) 27 explained, “The problem says we need to design a water tank that holds exactly 20,000 litres. Should we start by exploring different shapes? P74 said, “I think we can explore with the GeoGebra 3D worksheet and identify a suitable shape that can hold water with minimal space.” P12 said, “Yeah, that’s a good idea, let us open the GeoGebra and we shall not fail to get one most appropriate.” In G2, P82 suggested, “Let us compare a cube and a cylinder. I will set the dimensions and see how the volume changes when we adjust the height and the length of the cube and the radius of the cylinder.” P21, “Eeeh! Do you see that this cylinder will need less surface area than the cube for the same volume?” Then P43 said, “Sure! But how? Why is it so? Let us have someone explain to me how it happens. Could it be due to the dimensions of the cube?” “I need to understand the reason behind your argument.” P06 explained, “Yeah! You see, we have to consider the surface area of the two shapes. For example, let us try to find the surface area for each shape.” The observation supported that IPMTs in this group notably displayed high levels of participation and interest. The integration of GeoGebra allowed them to interact dynamically with the scenario, with curiosity and sustained attention. Some IPMTs who were still struggling with using the software were supported by peers and the instructor to navigate.

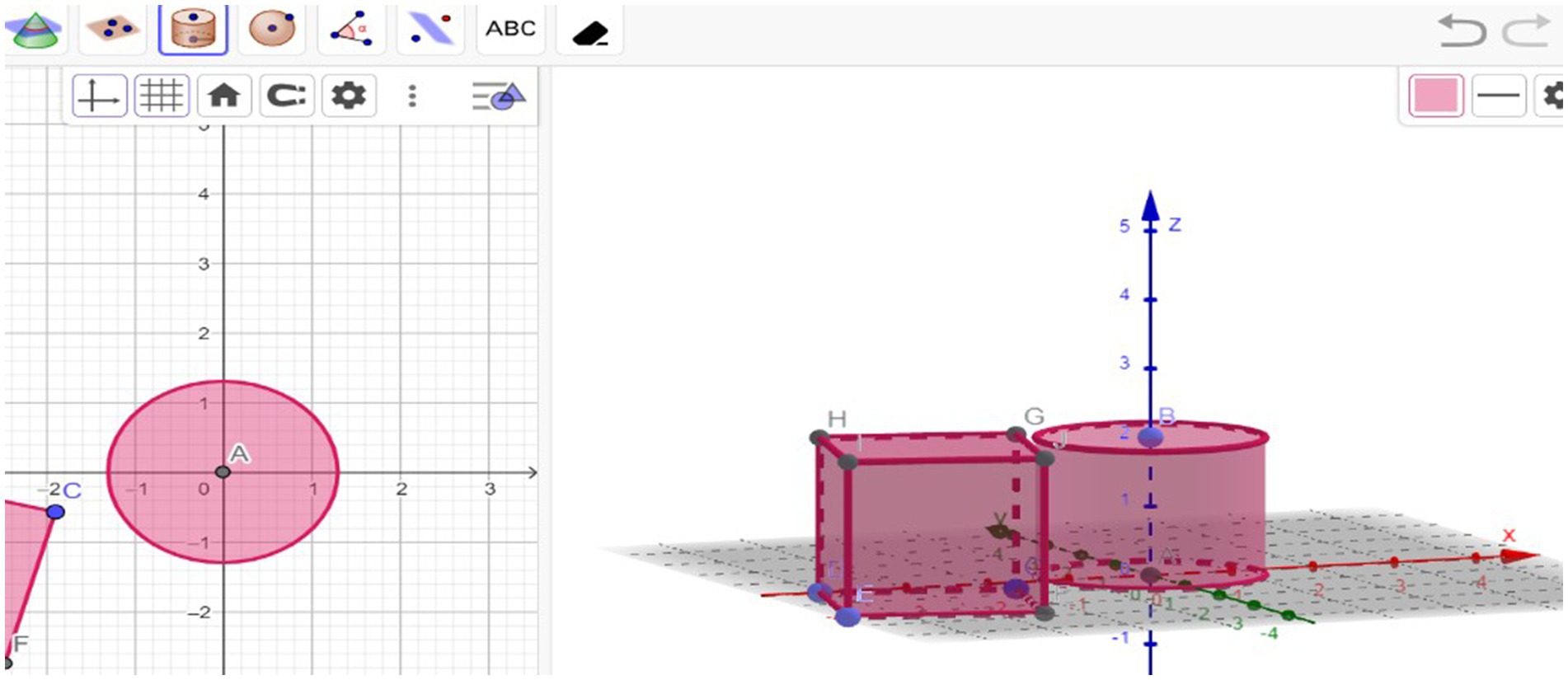

In G2, P82 suggested that they first design parameters for the cylindrical and the cuboidal tanks. Each group member worked out the radius for the cylinder. They each shared their findings and asked each other how they arrived at the radius. P47 explained the process of calculating the radius, “Since we have the volume as 20 m3, and the height as 2metres, then we can calculate the radius by taking volume is equal to Pi times radius squared times height, (V = πr2h), substitute the volume, Pi (𝜋=3.14), and the height. When we put this in our calculator, we get the radius to be approximately 1.78.” P21, who was the chairperson of the group for that session, summarised, “We now have our calculations for the cylindrical tank; height is 2 m, radius is approximately 1.78 m, surface area is also approximately 42.42 m2. For our cuboidal tank, height is 2 m, square base length is 3.16 m, and surface area is approximately 45.3 m2. G2 tried to design the two shapes on the GeoGebra worksheet (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 shows G2’s models of cylindrical and cuboidal tanks, which they designed on a GeoGebra worksheet. They designed the two at approximately equal height to visualise which of the two was more compact. The IPMTs’ proposals for exploring with GeoGebra and the inquiries they made to tackle the problem scenarios suggested greater cognitive and emotional engagement. Meanwhile, the CG was also engaged with the same scenario of “Rainwater harvesting tanks.” Through direct instruction and use of textbook examples, IPMTs were introduced to the scenario by outlining the volume requirement of 20,000litres (20𝑚3). They were guided through the formulas for calculating volume and cuboids using one of the displayed charts in the classroom (Figure 7).

Figure 7 represents a chart which shows the formulas for finding the surface areas and volumes of the different 3D geometric figures, including a cube, cuboid, cylinder, and rectangular and square pyramids. It was made by the researcher and displayed in the classroom at the front near the chalkboard, to help remind IPMTs whilst solving problems related to surface areas and volumes of those figures. The IPMTs were engaged in discussions as a whole class whilst answers were written on the chalkboard. IPMTs were guided to individually compute the corresponding base dimensions and surface areas. From their calculations, they concluded that the cylindrical tank was more efficient due to its lower surface area.

In Lesson 7, IPMTs in both classes were assigned a scenario that required them to design a visual rectangular-shaped or cylindrical container, which could hold 100 mangoes: “Amagara Juice Factory wants to design storage containers that will safely transport mangoes from farms to the factory. The containers must be strong, spacious, and easy to stack in a truck. Help to design a visual rectangular-shaped container that can hold at least 100 mangoes, where each mango takes up 250 cm3.

a. Choose the dimensions of your container in centimetres.

b. Calculate the volume of your container.

c. Display your designed container to appeal to the factory manager.

The factory truck can accommodate up to a volume of 300,000 cm3. How many of your containers will you need to design?

In EG, P13 from G6 explained, “The problem says we need to design a storage container for transporting mangoes. Should we try designing it as a rectangular prism first? P75 added, “Yeah! Good idea. Let me open GeoGebra, okay, I have created a box. If we keep the height at 50 cm, what happens when we increase the base dimensions?” P28 said, “Remember one mango occupies 250 cm3, so if height remains 5 cm, then we need a base and width which, when we multiply the three numbers, we shall get 250𝑐𝑚3, because they should be three numbers, the length, width and height.” P13 added, “That’s so helpful! Let us look for the three numbers” P55 in agreement said, “Aaaah, yes! And then we shall find the volume of the container to hold the 100 mangoes.” Then, P28 commented, “Exactly, but before we go to finding the volume of the container, let us try to increase the dimensions of our box to see what it will look like. For example, you can use that computer to investigate with 5 × 5 × 10, then for us we investigate with 10 × 5 × 5.” P13 added, we need a scale, then, can we suggest for every small box to represent the 250 cm3, then extrude to design the container of 100 mangoes.” Different groups of the EG explored the different alternatives for the container dimensions (length by width by height) (50 × 25 × 20, 25 × 20 × 50, 20 × 50 × 25) by designing them using GeoGebra with a scale to accommodate the dimensions. In G2, one IPMT first sketched the container on paper (Figure 8).

Figure 8 shows a sketch of the container made by G2. They were investigating the container shape and its dimensions. In their presentation in plenary, the presenter showed that each small box was for a mango occupying 250 cm3, thus they could pack ten by two by five mangoes. They also used GeoGebra and attempted to design the container (Figure 9),

Figure 9 indicates Group 2’s attempt to design a 10 by 2 by 5 unit cube container, which was not completed. In a discussion, one member explained, “To make our container with a base of 10 units, width of 2 units, and height of 5 units so that finally we have 100-unit cubes, we keep extruding cubes in each dimension until we have all the dimensions. In the CG, IPMTs were individually engaged in drawing sketch diagrams of rectangular-shaped figures. They were guided in a class discussion on how to calculate the dimensions and the volume of the rectangular container. Their contributions, which they gave by raising their hands, were written on the chalkboard. They drew their sketch diagrams of the rectangular-shaped containers in their exercise books, Manila paper, and labelled their dimensions. They were also guided to design visual rectangular boxes using paper. Two IPMTs in the CG class worked together and successfully designed a rectangular-shaped container using cardboard, banana fibre, and a pair of scissors, a metre ruler, a pencil, and masking tape (Figure 10).

Figure 10 shows a rectangular-shaped container designed by two of the IPMTs in CG. They used local materials, which included banana fibre, cardboard, and masking tape, to develop it. They used the model to present to the whole class the dimensions (the length, width, and height) of their designed shape. In Lesson 8, IPMTs were tasked to solve a real-world problem scenario about packaging material for cubes of soap. The context of the scenario: “A local soap producer needs help designing a package to hold eight cube-shaped soaps. Explore the various 3D arrangements of the eight cubes inside a single rectangular box. Determine the most compact and material-efficient box shape. Give a reason for your answer.”

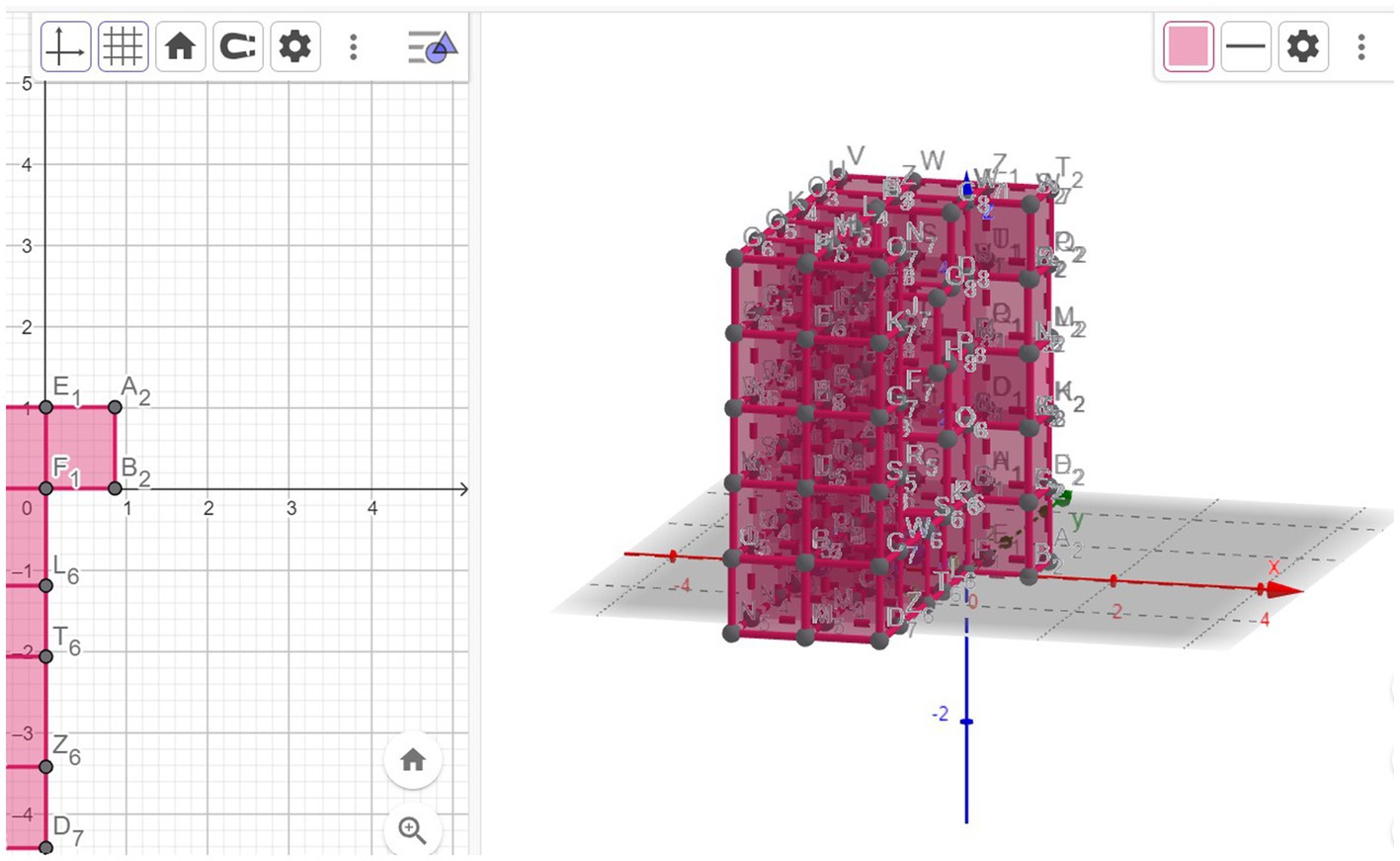

The EG worked in their groups whilst the CG discussed as a whole class and at desk level, where they were seated three or four at a desk. EG used GeoGebra to design various patterns of eight cube-shaped pieces of soap (see Figure 11).

Figure 11 shows the three different patterns of rectangular-shaped containers designed and displayed by G2. The first pattern indicates a four by two by one (4 × 2 × 1) or two by four by one (2 × 4 × 1). The second one shows a one by one by eight (1 × 1 × 8), and the last one shows a two by two by two (2 × 2 × 2). Similarly, in plenary, P30 from G8 presented the group’s three different designs and explained, “We got three different arrangements of the eight cube-shaped soaps, arranged in the order of length by width by height. We have the first one as 4 × 2 × 1, the second as 1 × 1 × 8, and the third arrangement as 2 × 2 × 2. When we examined the three designs, we discovered that the most compact and material-efficient box shape is the 2 × 2 × 2 arrangement.” She explained the reason for their finding, saying, “This design forms a perfect cube, which encloses the 8 unit cubes with the smallest possible surface area for that volume.” P19 from G1 asked for the reason for their conclusion. P16 from the presenting group raised his hand and explained, “Since surface area determines the amount of material needed to construct the box, a cube shape minimises material usage compared to more elongated forms like 1 × 1 × 8 or 4 × 2 × 1.” Whilst P09 from G4 said, “Yeah! The cube has balanced dimensions, offering structural stability and ease of storage and stacking. This makes the 2 × 2 × 2 box both practically efficient and cost-effective in the packaging scenario.”

IPMTs from other groups asked critical questions and shared their opinions. For example, P28 from G6 said, “I understand the point about surface area, but is not the 4 × 2 × 1 design potentially more practical in some retail scenarios? For example, if shelf space is limited in height but not in length, would not that shape fit better in certain displays even if it uses a bit more material?” P30, the presenter responded, “That’s a valid point, and retail space plays a role in packaging decisions. However, our focus was on material efficiency, but we agree that shelf compatibility is important too. The presenter added emphasis that in real-world applications, companies might choose a 4 × 2 × 1 design if it better suits display requirements. Still, from a pure material usage and structural standpoint, the cube remains the most efficient.

P36 from G3 commented, “I see why a cube might use the least surface area, but can you show us how you calculated the surface areas for all three designs? I think it would help if we saw the exact numbers to compare material usage more clearly.” The presenter explained, “Sure! We actually calculated the surface areas during our design comparison. For example, for the 2 × 2 × 2 cube, the surface area is 6 × (2 × 2) = 24 square units. For the 4 × 2 × 1 box, it’s 2 × (4 × 2 + 4 × 1 + 2 × 1) = 2 × (8 + 4 + 2) = 28 square units. And for the 1 × 1 × 8 box, it’s 2 × (1 × 1 + 1 × 8 + 1 × 8) = 2 × (1 + 8 + 8) = 34 square units. So, you can see that the cube uses the least material to enclose the same volume.”

In a similar lesson with the same scenario in the CG, IPMTs were presented with the same scenario, helping a local soap producer design a rectangular box to hold eight cube-shaped soaps in the most material-efficient way. Some IPMTs sketched quick diagrams of possible arrangements in their exercise books, whilst others described verbally the configurations they imagined. All their contributions were written on the chalkboard, which included a single column (1 × 1 × 8), arranged flat in a rectangular shape (4 × 2 × 1), and compactly in a cube (2 × 2 × 2). They were guided to calculate the surface areas of each arrangement to determine which one was the most material-efficient. One IPMT (P03) led a class discussion, and they compiled a comparison table on the chalkboard for the box dimensions (1 × 1 × 8), (4 × 2 × 1), and (2 × 2 × 2), and their surface areas, 34 square units, 28 square units, and 24 square units, respectively. IPMTs were guided to assess each of the arrangements and choose one that was most material-efficient. P41 said, “(1 × 1 × 8) shape is very tall, the (4 × 2 × 1) shape is flat, but the (2 × 2 × 2) shape is most compact and has the smallest surface area, hence it is the most efficient one in material cost.

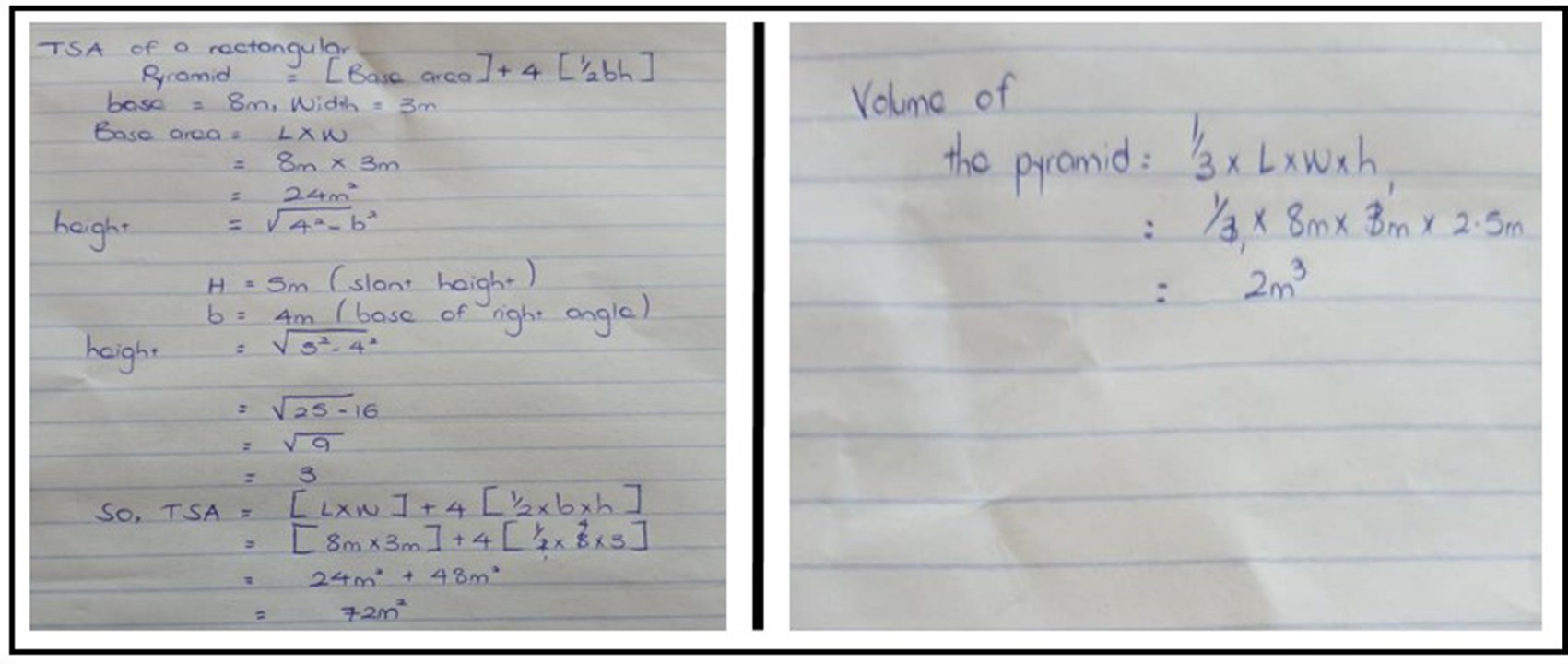

In Lesson 11, IPMTs were oriented to the surface area and the volume of a rectangular pyramid with a scenario that required them to plan a design of a tent to be used on a camping trip. “You have been asked to plan a design of a rectangular pyramidal tent for a camping trip. The tent must have a base length of 8metres, a base width of 3metres, a height of the middle pole of 2.5 m, and a slant height of 5m. It must all be covered with a canvas to protect the inhabitants from outside harm. Sufficient aeration in a tent is approximately ≥0.8 cubic units of space it occupies. How much of the canvas will be required to design the tent? Investigate the adequacy of good aeration in the tent to be designed.”

The IPMTs in EG used GeoGebra, which stimulated high levels of engagement. In their small groups, they designed the rectangular pyramids on the GeoGebra worksheets. G6 designed its pyramid with the z-axis on the 3D sheet targeted as the middle pole of the tent (height of the pyramid). They used a slider on the 2D sheet to unfold the pyramid (net of the pyramid), which they used to investigate the size of the canvas they required for the whole tent (Figure 12). One IPMT in the group suggested that they determine the surface areas of each of the parts of the net of the pyramid and add them together. They added the area of the base (8 m × 3 m) to the area of the four triangular faces [4(8 m × 3 m × 12)] and obtained 72 m2. Also, G3 used their modelled pyramid to visualise its volume and concluded that a rectangular pyramid is a third of a cuboid. To investigate the level of aeration in the tent to be designed, they computed the surface area of the base and multiplied it by the height of the pyramid (middle pole), then multiplied it by a third, [8 m × 3 m × 2.5 × 13] = 2 m3.

Figure 12 indicates two parts of the designed rectangular pyramid by G6. Part A shows the pyramid on a 3D sheet in its entirety. Part B shows the net of the pyramid, indicating the base area, the four triangular faces laid open, and the middle pole (height of the pyramid). IPMTs used this open pyramid to investigate the total surface area of the canvas that was required for the tent.

In CG, IPMTs brainstormed how to find the canvas’s total surface area that was required. One IPMT raised their hand and suggested sketching the tent in the shape of a rectangular pyramid and finding its surface area. The IPMTs used the formula for finding the total surface area of a rectangular pyramid indicated on a displayed chart. One IPMT worked out the total surface area in her exercise book (Figure 13).

Figure 13 indicates one of the IPMTs’ procedural works in her exercise book, showing how she worked out the total surface area and the volume of the pyramid following the predetermined formulas and procedures.

5 Discussion

In this study, the objective was to investigate the impact of the GSPBL approach. Results from the test of hypothesis one indicate that the GSPBL approach significantly impacts the understanding of 3D geometry among IPMTs. The finding that the IPMTs exposed to GSPBL performed significantly higher in the post-test than in the pre-test indicated that the IPMTs’ understanding was significantly enhanced. This finding aligns with the theoretical framework proposed by William (2011) within the context of activity theory. According to this theory, when students are provided with opportunities to deeply engage with learning activities, understand them in a meaningful way, and actively transform their learning experiences, they become more empowered to navigate and address different situations and challenges. The results of this study provided empirical support for this claim, highlighting the effectiveness of the GSPBL approach in fostering a deeper conceptual understanding of 3D geometry among IPMTs.

During instruction, a notable distinction was observed between the CG and the EG. Whilst the CG primarily emphasised procedural knowledge, the EG focused on conceptual understanding, fostering active engagement through individual research and group collaboration supported by the GeoGebra tool. As highlighted by Eshetu et al. (2022), IPMTs in the EG demonstrated an enhanced ability to articulate the interconnections between 3D geometric concepts and their properties. They also effectively explored surface areas and volumes using GeoGebra and provided logical explanations for procedural steps. Furthermore, visualisation, facilitated by GeoGebra, played a crucial role in strengthening IPMTs’ conceptual comprehension of 3D geometry. Gunawan et al. (2019) emphasised that effective visualisation stimulates students’ cognitive processes, enabling them to grasp complex material more creatively. This increase in creativity allowed IPMTs to identify personalised learning patterns, ultimately optimising their learning outcomes and fostering a deeper understanding of 3D geometry.

Moreover, as suggested by Selvy et al. (2020), the GSPBL tasks assigned to the IPMTs were designed as ill-structured, open-ended, real-world problems. This approach provided IPMTs with opportunities to engage in solving complex and authentic mathematical challenges that closely resemble real-world scenarios. Engaging with such problems not only enhanced their understanding of 3D geometry but also facilitated the development of essential problem-solving, creativity, and critical reasoning skills. These cognitive abilities are crucial in enabling students to tackle advanced mathematical concepts and apply logical reasoning in diverse contexts (Ssemugenyi, 2023). By grappling with ill-structured problems, IPMTs were encouraged to explore multiple solution pathways, justify their reasoning, and refine their analytical skills. Consequently, the incorporation of GSPBL tasks within the learning process equipped IPMTs with the necessary competencies to navigate complex mathematical problems, reinforcing their ability to think critically and creatively when faced with real-world challenges.

This finding corroborates those of the earlier studies conducted in Indonesia, such as Akhdinirwanto et al. (2020), Gunawan et al. (2019), Pamenan et al. (2022), and Selvy et al. (2020), who came up with similar findings. It is clear from this finding that before the IPMTs in the EG were exposed to the GSPBL approach in learning 3D geometry, their performance mean score in the pre-test was 14.20, as compared to their performance in the post-test, which was 18.07, after exposure to GSPBL. The EG’s performance in the pre-test indicates that IPMTs were not familiar with solving ill-structured, open-ended, real-world problems in geometry learning. This implies that it is highly likely that mathematics teacher educators employed traditional methods in teaching mathematics concepts that are procedural and formulaic. Such traditional instructional methods were reported to be used by most teachers when it comes to teaching mathematics, claiming that most students have gaps in knowledge that the teacher must fill with lots of information (Ardeleanu, 2019). However, it is obvious from the findings of this study and other studies, such as Kanyesigye et al. (2022a,b) and Klegeris and Hurren (2022), that IPMTs learn better when they are encouraged to discover their knowledge of the surrounding world.

After instruction of 3D geometry to the EG and CG for 5 weeks, a post-test was given to establish if the GSPBL approach had enhanced IPMTs’ understanding better than the traditional methods. Findings from the test of hypothesis two indicated that the EG outperformed the CG. As provided in this study, there appears to be a significant impact of GSPBL on IPMTs in understanding 3D geometry concepts. The success of the IPMTs in the EG, as asserted by Selvy et al. (2020), was due to the PBL learning model that presented the contextual problem so that the IPMTs were actively involved in the learning activities, creative thinking, seeking information, processing data, and summarising the problem-solving. Besides, the use of GeoGebra helped IPMTs simplify the learning process and discover the concept of 3D geometry in the form of simulations. It is possible, as asserted by Klegeris and Hurren (2022), that the higher performance of the EG than the CG in the post-test is partially because IPMTs in the EG were taught 3D geometry through GSPBL. Unlike the CG, who had limited engagement with the 3D geometry material, the EG’s problem-solving, creative, and critical thinking skills, and collaboration were highly enhanced.

Whereas Ssemugenyi’s (2022) findings from a study conducted at the University of Kisubi, Uganda, indicated that the academic performance of students taught using PBL did not significantly differ from those taught through traditional methods, the present study demonstrates that GSPBL is a more effective approach for fostering meaningful learning compared to conventional methods. The limited impact of PBL on conceptual understanding in Ssemugenyi’s study may be attributed to the absence of technological tools or the brief exposure period to the PBL approach, yet, like in this study, students in Ssemugenyi’s study were introduced to PBL for the first time, which may have hindered their ability to fully benefit from the methodology. In contrast, the current study incorporated a more extended period of engagement with GSPBL, allowing students to familiarise themselves with the approach and maximise its potential benefits. Extending students’ exposure to a new instructional approach enhances their ability to internalise concepts, adapt to novel learning strategies, and develop essential problem-solving skills (Ali, 2019; Razak et al., 2022). Tawfik et al. (2020) further asserted that prolonged engagement with innovative pedagogies fosters deeper cognitive processing and long-term knowledge retention.

Empirical studies, such as those by Ayanwale et al. (2022) in South Africa and Pamenan et al. (2022) in Indonesia, have also demonstrated that extended exposure to technology-integrated learning environments can significantly improve students’ conceptual understanding and engagement. In the context of this study, IPMTs in the EG received sustained exposure to the GSPBL approach for over 2 months. This prolonged engagement likely played a critical role in the observed improvement in meaningful learning outcomes. Extended interaction with GSPBL may have allowed the participants to gradually overcome initial learning difficulties, build confidence in problem-solving, and refine their critical thinking skills. This aligns with the findings of Darhim et al. (2019) in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, who reported that integrating GeoGebra into problem-based learning environments significantly enhanced students’ comprehension of solid geometry. The dynamic and interactive visualisations provided by GeoGebra helped bridge the gap between abstract 3D concepts and practical application, making learning more accessible and meaningful. It is also noteworthy that the CG, which was taught using traditional instructional methods, was exposed to mathematics instruction for the same duration as the EG. Although the CG did not receive the benefit of the GSPBL approach or technology integration, their prolonged engagement with the same real-life scenarios likely contributed to a slight improvement in learning outcomes, albeit not as substantial as that observed in the EG.

This suggests that extended instructional time alone can produce some level of conceptual gain; however, the quality and nature of the instructional approach appear to be decisive factors in achieving meaningful learning improvements. In other words, these findings highlight the dual importance of both instructional duration and pedagogical innovation. Whilst extended exposure to content can yield moderate learning gains regardless of teaching method, the combination of sustained engagement with student-centred, technology-enhanced instructional strategies like GSPBL offers a more profound and lasting impact on students’ conceptual understanding and problem-solving abilities. Beyond the significant positive effect of GSPBL on IPMTs’ understanding, the qualitative phase of this study, through observing the lessons, gave more insights. IPMTs in EG, in their small groups, collaborated through sharing ideas, opinions, and knowledge as well as member roles following the activity theory as suggested by Jaworski et al. (2007). At the same time, they also used GeoGebra, which was installed on the CPTC laboratory computers, to visualise, manipulate 3D shapes, and explore the surface areas and volumes of 3D shapes. Generally, four major themes emerged from EG lesson observations: engagement with problem-solving, use of GeoGebra and visualisation, collaboration and peer feedback, and knowledge application.

5.1 IPMTs’ engagement with problem-solving

The findings of this study indicate that IPMTs’ engagement with problem-solving was evident in the GSPBL-instructed class. This was particularly demonstrated through their dedication to tasks, both in terms of the time they invested and the effort they exerted. Such engagement goes beyond mere intellectual involvement; it also encompasses psychological and behavioural components, as described by Riswari and Bintoro (2020). In this regard, the study’s findings align with Riswari and Bintoro's (2020) assertion that engagement in problem-solving through the GSPBL model fosters a deeper connection to the learning process. Similar patterns were observed globally. For instance, a study in the Philippines by Benedicto and Andrade (2022) revealed that pre-service teachers faced challenges in non-routine problem-solving but showed improved engagement and resilience when exposed to structured problem-based interventions. The active participation of IPMTs in the 3D-related scenarios suggested that they not only focused on finding solutions but also experienced an intrinsic motivation to learn. A study that drew on survey responses from American high school students indicated that students’ ratings in TSPBL were associated with the interest they demonstrated in solving complex STEM problems (Laforce et al., 2017). Meanwhile, Ocak and Uluyol (2010) described interest as a motivational construct that refers to the state of being engaged with a particular idea. In this study, IPMTs’ engagement enabled them to express their ideas and opinions freely, promoting a more dynamic and interactive learning environment.