- 1Department of Special Needs Education and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Educational and Social Sciences, Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

- 2Department of Rehabilitation Education, Philosophical Faculty III, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany

Introduction: The right to education is recognized as a fundamental human right in international law. Despite these legislative foundations, education systems still often fail to recognize and provide the necessary accommodations and support needed by many autistic students. Studies on mainstream schooling of autistic students predominantly report negative experiences, as their needs are not adequately addressed, leading to stress and anxiety. Attendance at mainstream schools has also been identified as a potential risk factor for school attendance problems. In Germany, research on the school experiences and absences of autistic students remains scarce. The present study therefore aims to investigate the role of emotions in the development of school attendance problems among autistic students in mainstream school settings in Germany.

Methods: The study employed a constructivist grounded theory design. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 autistic students between 7 and 20 years, who experienced school attendance problems within the German mainstream school system. Interviews were transcribed with high level of accuracy to capture how emotions were expressed. The interviews analyzed through iterative coding, including initial, focused, and theoretical coding. In-vivo codes were applied to preserve participants' perspectives and generate a theory grounded in the data.

Results: Findings show that autistic students experience school attendance as stressful and exhausting due to sensory overload and barriers in reciprocal interaction with peers and teachers. Stress accumulated over time, resulting in anxiety, panic, anger, and exhaustion, which directly contributed to school absenteeism. Students used strategies to adapt and endure the environmental factors, which did not regulate but rather intensified their stress. At the same time, positive emotions such as the desire to learn, willingness to attend or return to school, and hope to re-engage occured as central motivational drivers for attendance. Results highlight the importance of environmental factors in shaping students' ability to fulfill their desire to learn and attend school.

Discussion: The study adds to existing literature by centering autistic students' perspectives and demonstrating how emotional experiences contribute to school attendance and absenteeism. The findings underscore the need for strength-based, flexible, and context-sensitive approaches. Future research is required to examine educational outcomes and wellbeing of students in mainstream schools.

1 Introduction

The right to education is recognized as a fundamental human right in international law. It is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), and explicitly extended to persons with disabilities through the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006). In Germany, this right is also anchored in the Basic Law [particularly Art. 7 in conjunction with Art. 2(1) and Art. 1(1)] as well as in the education laws of the federal states. With this right comes the obligation to design education systems that guarantee participation and non-discriminatory access to learning for all students. Achieving this requires structural change, flexible learning arrangements, and a professional stance that actively acknowledges and values diversity (Booth and Ainscow, 2002). Education therefore, means more than the transmission of knowledge, it is a central part of social participation and personal development. For an inclusive society, it is essential that all children and young people are able to learn together (Booth and Ainscow, 2002). Yet despite these legislative foundations, education systems still “often fail to recognize and provide the necessary accommodations and support needed by many autistic students” (McGoldrick et al., 2025). Educational provision continues to be shaped by deficit-oriented assumptions that construct neurological differences as deviations from an assumed norm, thereby undermining the principles of inclusion (Ducarre, 2024).

An approach that views diversity not as a deficit but as a natural variant of human existence is offered by the neurodiversity paradigm (Alcorn et al., 2024; Ducarre, 2024; Shaw et al., 2024). This perspective recognizes variation in perception, action, and thought as intrinsic to all individuals and provides a framework for discussing diversity while simultaneously advancing an inclusive understanding of education (Ducarre, 2024). By moving away from a medical model that defines autism as a “disorder,” attention shifts toward the societal barriers that produce restrictions in the first place. Central to this paradigm is ensuring that the experiences and perspectives of neurodivergent individuals are placed at the center, and that language, structures, and support are not shaped by neurotypical norms but oriented toward the wellbeing and goals of neurodivergent people (Shaw et al., 2024). From this perspective, learning environments should be designed to acknowledge and foster diversity while enabling autonomy, belonging, and participation for all students (Ducarre, 2024). An inclusive education system, in line with the CRPD, therefore both recognizes neurodivergence as a valuable form of human diversity and responds to barriers by providing needs-based support. Autistic students nevertheless often experience educational settings as exclusionary, as these remain shaped by neurotypical expectations (Alcorn et al., 2024). At the institutional level, autistic traits are still frequently viewed through a deficit-oriented lens, resulting in support and interventions that aim at normalization rather than participation and the development of individual strengths. To overcome educational exclusion and to strengthen autistic students' self-efficacy and mental health in the long term, a true paradigm shift toward neurodiversity is required (Ducarre, 2024).

While there is research regarding general school attendance in Germany (a.o. Enderle et al., 2024; Speck and Stauvermann, 2025), currently, there is no representative data on school attendance of autistic students (Sasso and Sansour, 2024). However, two non-representative surveys conducted by the national autism association (autismus Deutschland e.V.) collected parental reports on their children's educational experiences (Czerwenka, 2017; Grummt et al., 2022). The first survey (Czerwenka, 2017; N = 621) found that at the time of data collection in 2016, one-third of the autistic students attended special schools, 45 percent attended secondary schools or grammar schools, 20 percent were enrolled in primary schools, and five students attended alternative forms of schooling. According to parents, 21 percent of students enrolled in special schools met the criteria for attending a mainstream school. Parents nevertheless reported that conditions such as smaller classes and greater teacher knowledge of autism made attendance possible only in special schools. They further indicated that placement in a special school was “not seldom […] the result of several school changes” (Czerwenka, 2017). In total, 132 exclusions from school were reported (approx. 21 %), with durations ranging from several months to as long as one and a half to two and a half years, most without replacement provision. Parents expressed the need for less bureaucracy in the application and continuation of support, increased expertise and openness among teachers, better cooperation between teachers and school support staff, smaller class sizes, access to quiet spaces, and acceptance of alternative forms of schooling. The second non-representative survey was conducted in 2019 with N = 1,343 participating parents. Here, 72 percent of the general statements about schooling were negative, describing the system as “inadequate” or even “catastrophic” (Grummt et al., 2022). 25 % of parents reported that their child had been excluded from school, with durations ranging from single days to several years. Forty-two percent reported at least one school change explicitly attributed to the child's impairment. Parents also noted that their children were often expected to adapt and display inconspicuous behavior. When this adaptation failed, a school transition became necessary. In this context, parents also reported severe psychological consequences, including self-injury and suicidality. Once again, parents emphasized the need for supportive conditions that had already been identified in the earlier survey. Numerous international studies on the schooling situation of autistic children and adolescents confirm the findings of these surveys and provide a comprehensive picture of autistic students' experiences in mainstream education. Mullally et al. (2024), for example, investigated the experiences of 136 autistic children aged 8–14 through semi-structured online surveys. Many reported experiencing school as an unsafe place where they felt misunderstood by both peers and professionals. A systematic review by Horgan et al. (2023), synthesizing 33 qualitative studies, identified three overarching themes: the demands of mainstream schooling, social participation, and the influence of school environments on students. The demands were described as academic, sensory, and transitional, with many participants characterizing their surroundings as crowded, chaotic, and sensory-challenging. Social participation emerged as a second key theme, encompassing relationships with peers, teachers, and school staff, as well as bullying. Several studies emphasized that, from the perspective of autistic students, effective teachers were those who understood individual needs, held high expectations, showed genuine interest, and refrained from shouting or expressing frustration. Conversely, lack of understanding and support were recurring concerns. The third theme related to the impact of mainstream school environments on wellbeing and mental health, with students reporting anxiety, loneliness, fear, anger, and frustration. Negative social constructions of autism and broader notions of difference often led students to conceal or mask their autistic identity in order to fit in. Anxiety was linked both to the intensity of sensory environments and to school-related demands such as heavy workloads, deadlines, and examinations. Feelings of fear, anger, and frustration were often internalized, leading in some cases to depressive symptoms and suicidality (Horgan et al., 2023). Despite these burdens, some students reported valuing their autism and associated differences positively, for example: “I like being like this you know, that's the way it is” (Humphrey and Lewis, 2008) and “I think I'm special, I am different from others and that marks me out of the crowd” (Poon et al., 2014). Zakai-Mashiach (2025) hypothesizes that the predominance of negative experiences among autistic students in mainstream schools may be partly explained by the absence of strength-based approaches within education systems.

1.1 Autistic students

Children and adolescents on the autism spectrum are highly diverse, a reality reflected in the very concept of the “spectrum” and underscoring the principles of neurodiversity. Autism is far more than the symptom-oriented criteria of diagnostic classification systems. Autistic individuals experience both challenges in interaction with their environments and distinct strengths, such as detail-oriented perception, cognitive abilities in logical reasoning, pattern recognition, and analytical skills (Cherewick and Matergia, 2024). Accordingly, many autistic people reject the notion of autism as a “disorder.” Because autism and its associated characteristics cannot be separated from the individual, and thus cannot be “cured” or “treated” (Vivanti, 2020), many prefer identity-first language (Gernsbacher, 2017; Kenny et al., 2016). To reflect this, identity-first terminology is also used in the present article. Autism typically manifests in early childhood, but developmental trajectories vary widely, influenced by an interplay of individual and environmental factors (Mailick et al., 2025). It is estimated that about 70 percent of autistic individuals experience at least one co-occurring mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression (Rosen et al., 2018; Curnow et al., 2023). These conditions substantially affect the development of autistic children and adolescents (Simonoff et al., 2008; Micai et al., 2023) and can have significant long-term consequences for health and quality of life (Lai et al., 2019; Curnow et al., 2023). Deficit-oriented diagnostic criteria, which are often used to describe autism-specific characteristics, particularly communication and interaction patterns, fail to account for strengths and abilities (Gernsbacher and Yergeau, 2019). Social interaction patterns and rules are generally learned by autistic children and adolescents less intuitively and more explicitly, often through targeted instruction (Plavnick and Hume, 2014; Ying Sng et al., 2018). Research shows that autistic students particularly benefit from structured, visually supported, and consistent learning environments, as these provide transparency regarding social expectations (White et al., 2023). Building on existing strengths, such as systematic thinking or detail-oriented perception, can further support the acquisition of social rules and patterns (Gernsbacher and Yergeau, 2019). Importantly, understanding between autistic and non-autistic people is a reciprocal challenge (Gernsbacher et al., 2017). Milton (2012) and Milton et al. (2022) conceptualized this phenomenon as the “double empathy problem,” emphasizing that empathy is a bidirectional process in which both autistic and non-autistic individuals may struggle to adopt the other's perspective. Misunderstandings can arise from differences in communication styles, interests, and perceptions in social situations. Thus, difficulties in communication should not be attributed solely to autistic individuals but rather understood as relational challenges. Positive interaction quality is marked by mutual understanding, reflected in less effortful and more relaxed communication, in which autistic adults report feeling less pressure to explain or adapt themselves, thereby reducing stress (Watts et al., 2024). Similarly, autistic children show greater social engagement when interacting with autistic peers (Kasari et al., 2016; Sutherland et al., 2025), and autistic adults disclose more personal information to other autistic individuals Morrison et al., (2020; Watts et al., 2024). (Morrison et al. 2020) conclude that “social interaction difficulties in autism may be better understood as relational rather than individual impairments.” One common strategy autistic individuals use, either consciously or unconsciously, to gain social acceptance and avoid rejection is “camouflaging” (Lundin Remnélius and Bölte, 2024). This involves masking autism-related traits in social interaction, for example by suppressing repetitive behaviors, maintaining eye contact despite discomfort, or preparing extensively for communicative situations (Hull et al., 2017). In addition, autistic individuals often experience differences in the perception and processing of sensory information. These may occur in any sensory modality (hearing, vision, touch, smell, taste, as well as proprioceptive and vestibular senses) and can involve either heightened sensitivity (hyperreactivity) or reduced responsiveness (hyporeactivity) to sensory input (Marco et al., 2011; Robertson and Baron-Cohen, 2017; Gray et al., 2023). Within educational contexts, such sensory differences may significantly affect students' capacity to learn and sustain attention, particularly in cases of heightened sensitivity to auditory or visual stimuli. These sensitivities have been linked to elevated anxiety, avoidance behaviors, and hypervigilance, all of which hinder full participation in classroom learning and social interaction. Schools represent environments rich in sensory input where students have limited control over their surroundings while simultaneously facing high demands (Gentil-Gutiérrez et al., 2021). Sensory issues therefore constitute a major source of elevated stress. Multiple studies emphasize the need to adapt school environments and to provide safe spaces to support regulation (Anderson, 2020; Gray et al., 2023; Martin-Denham, 2022).

1.2 Emotionally based school attendance problems

A growing body of research recognizes the role of the school system and school-related interactions in shaping school attendance problems, alongside the stress that contributes to them (Connolly et al., 2023). While school attendance problems and absences are widely acknowledged as multidimensional phenomena involving multiple systemic levels (Melvin et al., 2019, 2025), autism-related research has tended to focus primarily on individual factors Mailick et al., (2025). (Mailick et al. 2025) emphasize the need for research that examines how contextual factors influence autistic individuals over time. As school-avoidant behaviors often arise from unmet needs, terminology surrounding school non-attendance should reflect that responsibility for such behavior or absences cannot be placed on the young person (Knage, 2023; Leslie et al., 2025). In the present study, the term school attendance problems was used to capture a broader conceptualization of engagement and disengagement in school, one that goes beyond physical presence or absence to also include forms of mental disengagement (Kearney, 2016; Enderle et al., 2025).

Even though school attendance problems among autistic students seem to gain internationally more attention in research and practice, the topic is still underrepresented in Germany in research, intervention and practice.

As most research on school attendance problems among autistic students is primarily based on parent and teacher perspectives (Sasso and Sansour, 2024), the research presented in this article is based on the perspectives of autistic students. The study presented in this article, therefore, seeks to explore how emotional experiences in mainstream school settings in Germany influence school attendance and absenteeism among autistic students.

The study is guided by the following question: How do autistic students experience their school attendance problems in mainstream school settings in germany?

This article especially focuses on the question: Which role do emotions play in the development of school attendance problems?

2 Methods

This study examines the perspectives and lived experiences of autistic students regarding school absenteeism and the role of related emotions. To capture these experiences and reconstruct students' realities, a qualitative design was adopted, drawing on Charmaz's (2025) constructivist grounded theory. Grounded theory allows researchers to analyze complex relationships and processes (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Unlike earlier, objectivist-oriented variants (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), Charmaz's constructivist approach conceptualizes reality as socially constructed. Researchers are active participants in the research process, and their subjectivity must be critically reflected as part of knowledge production (Charmaz, 2025). This approach is particularly suited to the present study, as it is theory-generating, reflexive, and context-sensitive. It enables an inductive development of theory while acknowledging the researcher's influence on the analytical process. In sensitive fields, where existing interpretations are often normatively shaped and lack nuance, constructivist grounded theory provides a robust and appropriate framework (Charmaz, 2025).

2.1 Participants

Eligible for participation were autistic children and young people who are experiencing or experienced school attendance problems while educated in mainstream schools. No age rage was specified. Participants were recruited through centers for autism support, via social media and self-help forums. Interested parties were asked to contact the project leader (I.S.) via e-mail or phone. Only participants who reported having a confirmed autism diagnosis were included. The diagnosis was not independently verified but was accepted based on participants' statements.

Twenty participants were recruited between seven and 20 years, 8 female and 12 male. The participants were from 9 out of 16 federal states in Germany (Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, Thuringia, North Rhine-Westphalia, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Berlin, Schleswig-Holstein).

The present article draws on the perspectives of n = 15 students (7 female, 8 male) between 9 and 20 years. Most participants reported periods of absences during secondary school, except for students still enrolled in elementary schools. Characterisations of the sample are presented in Table 1.

2.2 Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between July and December 2023, 11 online, eight in person and one participant answered the questions in written form as he is non-verbal. The interview guide was structured and informed by the findings of the systematic review (Sasso and Sansour, 2024) and covered individual, school and parental factors while encouraging participants to narrate their experiences. The semi-structured interview format was chosen because it combines openness, by providing space for narratives and accommodating situational and individual variations in the narrative process with specific questioning techniques guided by theoretically informed prompts (Witzel and Reiter, 2012). Shortly before the interviews, participants completed a brief questionnaire that gathered relevant personal and contextual information such as age, interests, grade level, school type, and longest period of absence, serving as preparation for the interviews. Following each interview, a postscript was written to document key points discussed before and after the interview. In addition, important observations regarding the interview situation were noted, and the researcher's own interview conduct was critically reflected.

2.3 Data analysis

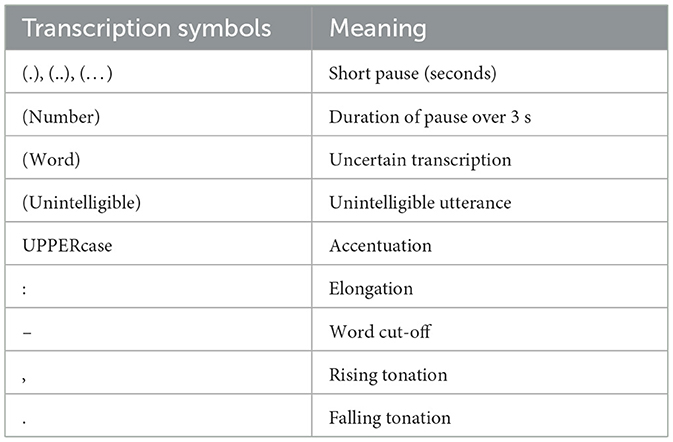

The transcription was carried out with a high level of accuracy, capturing not only the content of speech but also the nuances of how it was expressed. This included noting pauses, repetitions, filler words, and other speech markers, which provide important context and convey the speaker's emotional tone, hesitation, or emphasis. These elements were preserved to allow a more nuanced analysis of the verbal exchange and are demonstrated in Table 2. The interviews were conducted in German, and quotations presented in this paper were translated by the author. Quotations are referenced using the interviewee's pseudonym, age, and position within the interview.

Constructivist Grounded Theory was utilized as the analytical framework for this study (Charmaz, 2025). This approach allowed to develop a theory grounded in the participants' experiences and perspectives. Through an iterative process, themes and patterns emerged inductively, offering deeper insights into the emotional, social, and sensory factors influencing school attendance problems among autistic students.

The core of the analytic process was stepwise coding, serving to structure, interpret, and theoretically condense the data. Coding proceeded through three interrelated phases that unfolded iteratively rather than linearly: initial, focused, and theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2025; Strauss and Corbin, 1990). This approach enabled the development of central meanings, relationships, and interpretive patterns directly from the material without imposing predefined theoretical categories (Strübing, 2021).

Initial coding aimed to identify meaningful codes in the data relevant for building categories. (Charmaz 2025) conceptualizes initial coding as an open approach, staying close to participants' own language in order to capture subjective meanings. Here, in-vivo codes which are taken directly from participants' words, were employed to preserve dense or symbolic expressions, emphasize participants' perspectives, and avoid premature interpretation. Comparative methods (Charmaz, 2025) were used to generate dimensionalized categories by contrasting codes both within and across cases. Constant comparison helped identify contradictions, ambivalences, and dimensions that informed theory development.

Focused coding was used to reach a higher level of abstraction and to identify relationships and interactions between categories. This phase built a more systematic understanding of the data by connecting initial codes and condensing them into central categories, which were then differentiated through subcategories and further specified in terms of their properties and dimensions. In this study, focused coding first produced analytically meaningful categories; in subsequent steps, relationships among categories were further elaborated.

Emotions were treated as integral components of motives, meaning-making, and coping strategies that shape participants' responses and actions (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Their role was analyzed through analytic memos, explicit coding of emotions, and attention to nuances in how participants expressed themselves.

Theoretical coding then served to link analytically rich categories in interpretive ways (Charmaz, 2025). Categories were not merely descriptive but functioned explanatorily by highlighting patterns, relationships, and processes within the data. Theoretical coding, in this sense, supported the exploratory and context-sensitive integration of meaning structures, remaining open to ambiguity, tensions, and processuality while taking participants' perspectives seriously. The aim was not to produce a universal explanation but to develop a theoretically dense, empirically grounded interpretation of social reality that captures the complexity of autistic students' experiences. The development and refinement of the central category was carried out through an ongoing interpretive process in which meaning structures, categorical connections, and theoretical ideas were continuously reflected.

Through this iterative process, a grounded theory was constructed that highlights how participants made sense of their experiences and how their emotions were shaped within the context. As the present article is part of a broader dissertation project, it does not present the full range of finding. Instead, it concentrates on the emotions which were expressed by the autistic students and their role in developing school non-attendance.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Prior to the start of the study, approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Oldenburg. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, anonymised and pseudonymised. Data were managed in accordance with German data protection law. In both the analysis and presentation of results, attention was given to protect privacy of data. Students and parents were provided with appropriate information to ensure informed consent.

Throughout the process, the researcher's role was subject to continuous reflection. This involved careful attention to (1) personal behavior, particularly in interactions with participants; (2) thoughts, especially regarding one's own expectations and preconceptions as well as the potential expectations of participants; and (3) emotions that arose during the research process and how these shaped interactions with participants and engagement with the data.

3 Results

Based on the findings, a grounded theory was developed that explains the process of school attendance problems, with particular emphasis on emotions. These emotions were constructed as the main phenomenon within the grounded theory that is based on the perspectives of autistic students. Causal conditions to negative emotions were found within the school environment, whereas positive emotions were determined by intervening conditions such as capabilities and qualities:

“So, in class, I understood everything quite quickly. (..) Um (5) well (4) I learn very quickly. (..) That means if I- well- (..) if I really WANT to learn something then I just understand it very quickly.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 58).

“So, I can, uh- When I'm awake and also interested I can learn very quickly, so I don't have to study too much, and I grasp the material in class quite quickly and can apply it directly.” (Malte, 18, pos. 73).

“That I um actually pick up things quite quickly and try to understand them as well […] I can just remember things very quickly.” (Matilda, 20, pos. 46).

“So right now, because the material is appropriate, I can usually- well, I, (.) uh (.) once I- once I get into it- I mean, once I start, I usually get thru it very quickly.” (Marten, 15, pos. 188).

Some participants expressed limitations in their capability to “understand quickly” and “to learn”. Leonie emphasized the link to the willingness to learn, while Malte explicitly referred to personal interest as a factor that enhances the speed of learning. Malte further tied quick learning to the condition of being “awake,” which may allude to challenges with early school start times or the need for sufficient rest. Marten's remark, “once I start” points to potential difficulties with initiating tasks, suggesting a need for support in getting started. These limitations are closely related to contextual circumstances, prerequisites, challenges, and structural conditions of everyday school life, such as resources, subject matter, support, and time of day, and illustrate how these factors can influence students' capability to learn. The significance of the school environment for the desire to learn is, for example, articulated by Felicitas:

“especially at the [name of the] school I noticed that I-, I was so eager to learn and when I left, I thought, noo, I don't want to learn if it's not absolutely necessary right now” (Felicitas, 12, pos. 98).

Negative emotions appeared mainly in the context of school attendance, while positive emotions were reported mainly in the context of learning. School non-attendance therefore appears as consequence, as autistic students experienced attendance as an obstacle to learning. The autistic students are primarily occupied with adapting to the learning environment and the expectations during their school attendance, which is why they can no longer muster any capacity for learning itself:

“So, let's assume, that I WENT to school, it was super stressful, I didn't really do ANYthing in class, I mean, I didn'- didn't really aCHIEVE anything. And then, yeah, I was-” (Marten, 15, pos. 128).

“Hm so the main thing, is that I hang in there or get thru the day, just sit in class, keep myself away from everything, mostly just in my own thoughts. I never really took any notes or anything like that,” (Matilda, 20, pos. 36).

“Going to school was no longer- I basically just went there to survive, so to speak.” (Till, 14, pos. 58).

“(I didn't) really keep up with the lessons anymore, so it wasn't really a proper school attendance anymore.” (Till, 14, pos. 64).

Enduring the conditions of everyday school life generates negative emotions and results in exhaustion (Figure 1). The initially strong will to learn, under the pressure of persistent stressors, shifts into an inability to learn. Autistic students report that their individual effort is insufficient to sustain regular school attendance. Over time, this constant adaptation, combined with limited opportunities for recovery or change, culminates in exhaustion.

3.1 Positive emotions as driver for attendance and learning

The narratives of how autistic students began to develop school attendance problems often started with their willingness to attend school in order to fulfill their desire to learn. The accounts show that school attendance and learning itself were frequently viewed and evaluated separately. In several examples, particularly those of Ella, Julian, and Leonie, school attendance was itself described as a desire:

“My strong will has also helped me, namely that I want to go to school. (4)” (Ella, 12, pos. 96).

”I always wanted to go to school and love the classes, if I couldn't go, it was always due to circumstances” (Julian, 18, pos. 18).

“And actually um so it makes me a little angry that I actually want to go to school. And I want- well I really want to go to school.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 90).

Felicitas, however, regarded school attendance primarily as a necessary burden in order to fulfill her desire to learn:

“I really wanted to learn a lot, and I just thought that, there was no other way to do it than in school. […] because I wanted to learn all of that, but, actually I never wanted to go to school itself” (Felicitas, 13, pos. 26).

Across all participants, it became evident that learning itself was the primary driver of their willingness to attend school, as exemplified by Julian's statement. The desire to learn thus emerged as a central motivation and a key driver of attendance. At the same time, this desire was frequently linked to frustration, anger, and hopelessness about not being able to attend school, as powerfully expressed in Leonie's account and echoed by Ella:

“I WANTED to learn something. I didn't want to learn nothing. I just couldn't.” (Ella, 12, pos. 40).

Extending these perspectives, Frida emphasized the link between successful learning and the enjoyment of learning, suggesting that the desire to learn is not only tied to attendance but also to the positive affective experience of learning itself:

“If I WANT to learn something or WANT to come to class, because I ENJOY it, because the learning methods are FUN, then LEARning works better.” (Frida, 15, pos. 179).

3.2 Stress, anxiety, and anger as driver for absenteeism

When schools fail to meet students' needs and they feel misunderstood, attending school becomes associated with negative emotions. Some participants described how numerous unresolved conflicts and situations accumulated over time. The lack of resolution and the inability to express their emotions led to significant stress, ultimately making them feel unable to attend school. Notably, participants often retained these experiences, recalling them years later with emotional intensity.

Participants reported experiences related to burdens such as shame, sadness, confusion, despair, pressure, and feelings of injustice. In most cases, one or several of these emotional burdens were mentioned. Stress was also accompanied by physical symptoms. The most frequently reported emotional burdens were stress, anger, and anxiety. Stress was described primarily as being triggered by conditions within the school context, most notably sensory challenges and difficulties in reciprocal interaction.

Sensory Challenges and Overload:

- “When they all screamed and talked so loudly, it was like a huge wave of sound, that completely overwhelmed the center of my brain and irritated it.” (Ella, 12, pos. 102).

- “I went to school, sat there, um, saw nothing, heard nothing, had (terrible) headache, so I didn't really accomplish much.” (Felicitas, 13, pos. 82).

- “due to my autism I couldn't filter the stimuli around me. And I perceived everything more intensely.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 52).

Reciprocal Interaction including Interaction with peers and teachers, as well as the lack of a sense of belonging:

- “I found it hard to do things with others because, somehow everyone, expected something from me. Um (..) well I was often overwhelmed um the- also with the communication somehow and conversations, um and I just- well I often felt somehow out of place, and well I was never really myself? I had to always pretend and somehow adapt (..) and that was just exhausting.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 50).

- “That's difficult because I can't talk or react when they [his classmates] say hello, I like them and I'm one of them, and they accept me but doing things together is difficult. I'm in but doing something together is difficult.” (Julian, 18, pos. 56).

- “I don't know. I often feel- (.) like (.) different from everyone else. (..) First of all because (…) autism and (.) yes I speak so much less than (..) all the other children. (..) And I'm mostly like (.) quiet. (…) Yes. (4)” (Enno, 9, pos. 90).

- “the teachers somehow couldn't take care of my problems there anymore, it was just too much, I was just a bit too different, I would say” (Till, 14, pos. 57).

- “where the teachers then put a lot of pressure and yes, directly told me and my mother that I should leave the school and that I don't belong there” (Malte, 18, pos. 21).

Within the framework of the grounded theory, the underlying conditions can only be outlined briefly at this point, as the present article is primarily oriented toward the role of emotions.

The experience of stress resulting from these conditions was directly expressed by several autistic students:

“actually a school day for me consisted only of stress. So I arrived at school and, then, it was actually already too much. […] Um I was already anxious about the class um and then in the class even more stress was added.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 48).

“Too many kids were stressing me out and it was too LOUD it was, (.) generally always TOO MUCH. I, couldn't THINK anymore and no one underSTOOD me.” (Felicitas, 13, pos. 15).

“I wouldn't say that those were specific situations. It was just the long accumulation of (.) stress and so on.” (Fred, 15, pos. 51).

“because I didn't learn anything and just became more stressed, which for some reason made the stress even worse. (4)” (Sven, 15, pos. 44).

“If it ever worked out completely eh it was usually just stress, especially if there were insults in class, yeah. So the day was always relatively stressful.” (Toni, 12, pos. 76).

The accounts indicate that stress during the school day is associated with feelings of being overwhelmed and agitated. Stress appears to accumulate over the course of the day, intensifying until it manifests as anxiety. One form of this anxiety is a more general fear of school:

“I also often didn't GO to school because I was afraid of it” (Leonie, 15, Pos. 6).

“I was too nervous (.) to go. School anxiety.” (Enno, 9, Pos. 44).

In many cases, it appears that anxiety itself is not the primary barrier to school attendance, but rather specific aspects of the school environment:

“Um I:I was afraid that I would have to say something in front of the class. (..)“ (Leonie, 15, pos. 48).

“I always have some kind of fear, that I might do something wrong. Yeah I was worried I might get in trouble with my classmates or with my teacher- my gym teacher.” (Alexandra, 14, pos. 120).

“Yes I think it's because of STRESS and fear of the other classmates because maybe someday it could come out that I for example have a (special educational need) or that they might laugh at me. So that (unintelligible) I didn't want to take any DAmage there.” (Till, 14, Pos. 15).

An increase in anxiety manifests as panic. Panic episodes were reported in direct connection with school attendance and appear to result from significant stress, developing over time as burdens accumulate:

“as soon as the bell rang for class to start um, I started having panic attacks and they just kept getting worse” (Leonie, 15, pos. 28).

“Because it was such a PANIC reaction, eventually I just couldn't go to school anymore.” (Marten, 15, pos. 20).

“shortly after I stayed home I had to go back to school to get my textbooks and stuff I then-then had this panic and was so stressed and (.) somehow totally uh (.) somehow yeah- (4) And yeah (.) I don't know if I could even go back to school.” (Fred, 15, pos. 63).

“The PANIC ATTACKS have already (started early) in class” (Till, 14, pos. 58).

“I always had these panic attacks and could hardly concentrate on the lessons. That was very bad.” (Till, 14, pos. 12).

Anxiety can also co-occur with anger, which appears to be directed both at objects and, more prominently, at the self:

“Mm (4) so, um- so I feel a lot of FEAr and also PAnic. (…) Mmmh and, somehow also helplessness. Hm (4) Somehow also a bit of anger” (Leonie, 15, pos. 20).

“But I think I was really angry and really really desperate” (Ella, 12, pos. 69).

“I am frustrated and angry and sometimes I hurt myself because I have to channel my anger somewhere.” (Julian, 18, pos. 35).

“So- it also happened that I:I punched the back of my bed or got very, very angry.” (Matilda, 20, pos. 30).

Negative emotions consistently co-occurred with mental health issues and impacted school attendance. Autistic students experienced emotional disturbances throughout all stages of their process. While absences initially provided short-term relief, this was quickly replaced by cognitive concerns about the future, alongside boredom, anger, and frustration. A key finding highlights the role of the environment: autistic students often reported anger and frustration due to a lack of support and limited opportunities to access education when attendance of a mainstream school was not viable. Leonie, in particular, expresses her anger and despair over the lack of support she and her family receive in re-engaging with school:

“a lot has actually happened but in the end somehow nothing at all because I'm still sitting at home and the school isn't really contacting us anymore, I haven't received any assignments from the school and so on. And actually um it makes me a bit angry that I actually want to go to school. And I want- well I really want to go to school. But somehow they just leave us alone. […] And I wish it were different.” (Leonie, 15, pos. 90).

3.3 Emotions as driver for re-engagement

Despite their disturbing experiences of negative emotions in school, autistic students expressed hope for finding a solution and a willingness to return to school, while others appear to have lost their hope over time and trust in the process.

“I longed so much to go back and just be there because that's my place where I can learn something.” (Julian, 18, pos. 26).

“I have always- always HOPED, that I- that I could go back to SCHOOL.” (Ella, 12, pos. 40).

“I knew, I couldn't handle it anymore, but I also wanted to learn something. (.) I- (8) I always hoped, that we would somehow find a solution” (Ella, 12, pos. 44).

Particularly through Ella's use of the past tense, it appears that she maintained hope over an extended period but currently no longer believes that she and her family can independently find a solution to their situation. Ella seems to occupy the same “waiting position” that Leonie describes in relation to her anger and frustration. This waiting position, combined with the ongoing search for a long-term solution, constitutes a significant challenge for autistic children and adolescents. They are also acutely aware of the consequences of absenteeism, including concerns about the future (Leonie, 15, pos. 42), reduced contact with friends (Fred, 15, pos. 39), and the feeling of missing out on both interpersonal experiences and academic content (Fred, 15, pos. 39; Edda, 9, pos. 214).

Nevertheless, participants reported a sense of relief following the cessation of school attendance, reflecting a temporary alleviation of the stress, anxiety, and pressures associated with the ongoing struggle to maintain regular attendance.

“but (.) in any case, I feel much better now than before” (Fred, 15, pos. 37).

“And, I would say, I am now happier than before, when I used to spend, 5 hours, until 4, recovering from school.” (Ella, 12, pos. 110).

“Compared to before I feel so good now better than I could ever feel. So on a scale from 1 to 10 I would say 1000. Um well compared to before. Of course not everything runs perfectly, but it never does.” (Marten, 15, pos. 40).

From the perspective of the autistic students, there currently appear to be “simply no good SOLUTIONs” (Frida, 15, pos. 189) to the dilemma that autistic students are unable to fulfill their desire to learn during school attendance using the strategies and resources available to them (see Figure 1). This underscores the pressing need to modify environmental factors in order to reduce their stress and support autistic students' learning within school.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of emotions when it comes to school attendance problems among autistic students.

The findings of this Grounded Theory study provide insights in how the interviewed autistic students experience their school attendance. A main outcome is the fact that the autistic students expressed a strong desire to learn and willingness to attend school, while simultaneously experience barriers to learning that cause stress, anxiety and anger. Their opportunities to fulfill the motivation to learn were significantly constrained by sensory challenges and difficulties in reciprocal interaction in the school environment. The inability to overcome these barriers with the means available to them led to experiences of helplessness and frustration, as well as broader concerns about future prospects, social participation, and a sense of missing out. These findings underline the urgent necessity of adapting school environments to meet the needs of autistic students and to enable their participation in learning without disproportionate emotional cost.

Emotions seem to play a crucial role when it comes to school attendance and absenteeism among autistic students. Negative emotions such as stress, anxiety and anger can therefore be seen as drivers for school attendance problems and absenteeism. However, these emotions are responses to environments that fail to meet the needs of autistic students over extended periods of time. Although inclusion is widely framed as a central educational priority, the reality often resembles integration, in which students are still expected to adapt to mainstream school settings rather than schools adapting to them (Pellicano et al., 2018; McGoldrick et al., 2025). The pressure to adapt amplifies the sensory, social, and emotional challenges experienced by autistic students, ultimately contributing to mental health difficulties, school attendance problems, and absenteeism (Den Houting, 2019; Shaw et al., 2024). Practices such as camouflaging meaning masking salient autistic behaviors and compensating for social-communicative challenges in order to meet external expectations and blend into specific environments, require considerable effort. This effort has been linked to emotional exhaustion, identity conflicts, and an increased risk of mental health problems (Hull et al., 2017; Lundin Remnélius and Bölte, 2024). Research further shows that adolescence is a period marked by heightened stress and exhaustion (Byrne et al., 2007; Pascoe et al., 2020; Sisk and Gee, 2022), which is associated with poorer mental health outcomes (Eppelmann et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2019; McGorry et al., 2025) and an increased risk of educational underachievement (Kaplan et al., 2005; Raufelder et al., 2018). For autistic children and adolescents, who already face a heightened risk of developing mental health conditions (Simonoff et al., 2008; Micai et al., 2023), these challenges result in complex, cumulative burdens. When adequate resources and support are lacking, these burdens can escalate into significant psychological consequences (Hoferichter and Raufelder, 2022). The findings of this study extend these perspectives by showing how the desire to learn and the willingness to attend school are gradually undermined by cumulative stressors in the school environment. As illustrated in Figure 1, the sustained effort to cope with adverse conditions leads to exhaustion and ultimately transforms a strong motivation to learn into an inability to engage in learning. This highlights the urgent need to reconfigure environmental conditions in schools to sustain attendance and participation.

The emotional burdens reported in this study, which contribute to both mental health challenges and school absenteeism, should therefore not be understood as a reflection of personal deficits but rather as the result of an imbalance between needs and available support within the mainstream school system in Germany. The necessity of adapting in order not to stand out socially is also described in the present study as an effort that leads to exhaustion and, ultimately, absenteeism. This underscores the need for environments that recognize and acknowledge autism-related differences in social interaction (Alcorn et al., 2024). Only when schools allow autistic students to show and communicate their challenges can these needs be adequately identified and addressed. Camouflaging, by contrast, makes the recognition of such needs more difficult (Truman et al., 2021). In Truman et al.'s (2021) study, parents reported that their children were able to mask their difficulties at school but subsequently broke down from exhaustion once at home. Similar patterns of profound exhaustion were also described by participants in the present study, such as Ella and Felicitas.

In a study by Atkinson et al. (2025), 72 autistic students attending mainstream schools were surveyed about school belonging, camouflaging, and anxiety. Of the participants, 38.9 percent reported feeling safe, accepted, and comfortable at school, whereas 61.1 percent indicated that this was not the case. When asked what helped them to be themselves, students highlighted friendships, but also support from teachers as well as inclusive adjustments such as the option to wear headphones and having access to a quiet room.

Especially the desire to learn, the willingness to attend and return to school highlight the importance of language when it comes to school attendance, especially when talking about autistic students. Phrases like “school refusal” or “school avoidance” imply that it is the individual that causes and chooses to refuse or avoid school. Leaving out the crucial role that emotional disturbances due to contextual environmental factor play in the process of becoming absent (Leslie et al., 2025).

A process of becoming absent emerged across participants, which appeared consistent across age groups but was described as occurring at different points as participants age varied. While several participants reported an initial increase in school-related difficulties during primary school, most experienced school attendance problems during secondary school. This pattern aligns with previous findings indicating that stress and emotional strain tend to intensify during adolescence and secondary education (Byrne et al., 2007; Pascoe et al., 2020).

The processual nature of school attendance problems is also reflected in the study by Hamadi et al. (2025), which emphasizes the lack of support that, from the perspective of participants, was provided “too late.” This process corresponds to the development of school absenteeism described by (Kearney et al. 2019). The contradiction between the experience of “no longer being able to attend school” and terms such as “school refusal” or “school avoidance” has likewise been highlighted in other studies (Corcoran and Kelly, 2023). Furthermore, students in these studies predominantly identified school-related factors, which, against the backdrop of insufficient support, contributed to absenteeism (Corcoran and Kelly, 2023; Hamadi et al., 2025). The fundamentally positive orientation toward learning, expressed in the present study as the desire to learn, is also reflected in the findings of Hamadi et al. (2025) as well as the “vicious cycle” of short-term relief when becoming absent, followed by negative emotions and the fear of missing out which was expressed by participants in the present study. At the same time, autism-specific differences become evident in this study, particularly regarding sensory processing, interactional challenges in reciprocal understanding, and the resulting needs within the learning environment. Accordingly, it is assumed that the burdens described occur with increased intensity in autistic students, whereas more general burdens can also be observed among other vulnerable students and may be interpreted as expressions of broader structural challenges within the school system.

The results highlight the need for holistic and strength-based approaches when addressing school attendance problems.

Findings from a scoping review by White et al. (2023) underscore the importance of such approaches in creating inclusive learning environments, reducing barriers, and supporting learning. While deficit-oriented interventions have shown some effectiveness in promoting executive or communication skills, they have also been linked to negative impacts on mental health, school experiences, and educational outcomes (White et al., 2023). By contrast, studies included in the review indicate that tasks aligned with autistic students' personal interests can significantly enhance motivation, concentration, and learning outcomes. A key condition for the successful implementation of strength-based approaches is a positive attitude among teachers toward neurodiversity, combined with professional awareness of autism-specific modes of perception and learning. Beyond individual pedagogical perspectives, structural conditions are also essential such as visual supports, predictable daily routines, sensory-regulated classrooms, and designated quiet spaces. Furthermore, the active involvement of students and their families in shaping these structures is consistently emphasized as critical. Shifting toward a strength-based paradigm in education fosters participation, improves wellbeing, and supports academic development among autistic students by reframing autistic characteristics not as challenges but as valuable resources (White et al., 2023).

Examples for such approaches can be find in autism-specific research and literature, as well as literature addressing school attendance problems. Autism specific approaches are exemplified by the Autistic SPACE framework (McGoldrick et al., 2025), which highlights five core domains, Sensory needs, Predictability, Acceptance, Communication, and Empathy, supported by considerations of physical, processing, and emotional space. Applied in education, this framework provides teachers with a practical roadmap to recognize and respond to autistic students' needs by making small but meaningful adjustments in classroom environments. This is directly relevant to the present findings, where sensory overload, lack of predictability, and limited acceptance emerged as central stressors that undermined students' desire to learn and contributed to absenteeism. It shifts the focus away from deficit-based models toward a neurodiversity-affirmative ethos that values autistic strengths and wellbeing, thereby supporting both learning and participation. Complementing this, the LEANS programme (Alcorn et al., 2024) represents a classroom-level intervention that introduces all students to neurodiversity concepts. The feasibility study demonstrated that LEANS is both acceptable and effective in enhancing students' knowledge, attitudes, and intended inclusive actions, with minimal risks of harm. This aligns with the results of the present study, in which social misunderstandings and lack of peer acceptance were identified as drivers of stress and emotional exhaustion. By fostering peer understanding and promoting more positive classroom dynamics, LEANS addresses precisely these social barriers. Together, SPACE and LEANS illustrate how inclusive practices can operate on different levels. While SPACE supports teachers in adapting environments to autistic needs, LEANS builds a broader culture of acceptance and awareness among peers, both of which are crucial for reducing stressors and supporting school attendance.

5 Strengths and limitations

The results must be understood within their limitations. First, due to the qualitative design, the ability to generalize findings is limited. The study was conducted within the German mainstream school context, and while this provides important insights, the findings may not be directly transferable to other educational systems, though they may serve as a basis for comparison. A further limitation is that autism diagnoses were not independently verified but relied solely on participants' self-report. Consequently, the accuracy of diagnostic status cannot be assured, which may limit both the validity and generalizability of the results. Moreover, the findings are based exclusively on the perspectives of autistic students, no interviews with parents or school staff were conducted. While this means that alternative perspectives may exist, the aim of the present study was to reconstruct the subjective perspectives of autistic students with school attendance problems. As shown in the discussion, these perspectives align with findings from other studies, highlighting the validity of the results.

At the same time, a strength of this study lies in its focus on autistic students' own voices, which provided in-depth insights into their lived experiences and the social constructions surrounding school attendance problems. The use of numerous direct quotations and in-vivo codes ensured that participants' perspectives were preserved and foregrounded. In line with Charmaz's (2025) criteria for assessing the quality of grounded theory studies which are reflected in originality, credibility, resonance, and usefulness, this study demonstrates originality by making the perspectives of autistic students on the development of school absenteeism visible within the “inclusive” German school system. The credibility of the findings is enhanced through systematic coding and continuous reflexivity, while the resonance is reflected in their relevance both for autistic students and for professionals working in this context. Finally, the usefulness of the study lies in its potential to inform future research and to generate concrete implications for inclusive educational practice.

6 Conclusion

The study investigated the perspectives and lived experiences of autistic students regarding school attendance problems and the role of emotions in the process of becoming absent. The study mainly identified how environmental conditions contributed to emotional burdens including stress, anxiety, and anger, which in turn lead to and intensified school attendance problems. These findings underscore the importance of shifting from deficit-oriented explanations toward a contextualized understanding of school attendance problems as outcomes of systemic and environmental challenges rather than individual failings. At the same time, the findings highlight the role of positive emotions such as the desire to learn, the willingness to attend and return to school, and the hope to re-engage. These emotions emerged as central motivational drivers that sustained students' connection to education despite adverse environmental circumstances. Recognizing and fostering these positive emotions is essential for approaches that not only reduce barriers but also build on students' intrinsic motivation for participation and learning. The current study adds to the growing body of literature highlighting the interplay between emotions, school environments, and attendance, thereby advancing autism-specific insights. To further explore these dynamics, future studies should investigate environmental conditions and emotional burdens in larger and more diverse samples. Quantitative data are needed to provide an overview of the prevalence of absenteeism among autistic students in Germany, while longitudinal studies are essential to examine long-term educational outcomes and wellbeing in the mainstream school system.

Finally, the study highlights once more the importance of centering students' perspectives in both research and practice. Participatory approaches are essential to ensure that educational and learning processes are designed to adequately reflect the needs, strengths, and lived realities of autistic students.

Data availability statement

The data generated and analyzed for this study obtain sensitive qualitative data from interviews with a vulnerable population. Due to ethical and privacy concerns data cannot be shared publicly. Access to anonymized data may be granted upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Oldenburg. Participants and, where applicable, their guardians received comprehensive written information about the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and from guardians for participants under 18. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. All data were treated confidentially and anonymised prior to analysis.

Author contributions

IS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Teresa Sansour for her encouragement and support during the whole research process. A special thanks goes to all students who participated in this research. Their willingness to share their thoughts, experiences, and reflections on both positive and challenging moments greatly enriched this research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author declares that Generative AI was used for grammar checking and to enhance readability during creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alcorn, A. M., McGeown, S., Mandy, W., Aitken, D., and Fletcher-Watson, S. (2024). Learning about neurodiversity at school: a feasibility study of a new classroom programme for mainstream primary schools. Neurodiversity 2, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/27546330241272186

Anderson, L. (2020). Schooling for pupils with autism spectrum disorder: parents' perspectives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 4356–4366. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04496-2

Atkinson, E., Wright, S., and Wood-Downie, H. (2025). “Do my friends only like the school me or the true me?”: school belonging, camouflaging, and anxiety in autistic students. J. Autism Dev. Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-024-06668-w

Booth, T., and Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools (rev. ed., reprinted). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education [u.a.].

Byrne, D. G., Davenport, S. C., and Mazanov, J. (2007). Profiles of adolescent stress: the development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). J. Adolesc. 30, 393–416. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.004

Charmaz, K. (2025). Constructing Grounded Theory, 3rd Edn. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi; Singapore: Sage.

Cherewick, M., and Matergia, M. (2024). Neurodiversity in practice: a conceptual model of autistic strengths and potential mechanisms of change to support positive mental health and wellbeing in autistic children and adolescents. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 8, 408–422. doi: 10.1007/s41252-023-00348-z

Connolly, S. E., Constable, H. L., and Mullally, S. L. (2023). School distress and the school attendance crisis: a story dominated by neurodivergence and unmet need. Front. Psychiatry 14:1237052. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1237052

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd Edn.: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi; Singapore: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781452230153

Corcoran, S., and Kelly, C. (2023). A meta-ethnographic understanding of children and young people's experiences of extended school non-attendance. J. Res. Special Educ. Needs 23, 24–37. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12577

Curnow, E., Rutherford, M., Maciver, D., Johnston, L., Prior, S., Boilson, M., et al. (2023). Mental health in autistic adults: a rapid review of prevalence of psychiatric disorders and umbrella review of the effectiveness of interventions within a neurodiversity informed perspective. PLoS ONE 18:e0288275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288275

Czerwenka, S. (2017). Umfrage von autismus Deutschland e.V. zur schulischen Situation von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Autismus. autismus 83, 42–48.

Den Houting, J. (2019). Neurodiversity: an insider's perspective. Autism 23, 271–273. doi: 10.1177/1362361318820762

Ducarre, L. M. (2024). Redefining the right to quality education for autistic children through a neurodiverse perspective. Scand.J. Disab. Res. 26, 366–379. doi: 10.16993/sjdr.1043

Enderle, C., Kotschy, L., Ricking, H., and Kreitz-Sandberg, S. (2025). Their voices matter: Student and professional perspectives on overcoming school attendance problems in the context of social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties. Front. Educ. 10:1627098. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1627098

Enderle, C., Kreitz-Sandberg, S., Backlund, Å., Isaksson, J., Fredriksson, U., and Ricking, H. (2024). Secondary school students' perspectives on supports for overcoming school attendance problems: a qualitative case study in Germany. Front. Educ. 9:1405395. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1405395

Eppelmann, L., Parzer, P., Lenzen, C., Bürger, A., Haffner, J., Resch, F., et al. (2016). Stress, coping and emotional and behavioral problems among German high school students. Mental Health Prev. 4, 81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mhp.2016.03.002

Gentil-Gutiérrez, A., Cuesta-Gómez, J. L., Rodríguez-Fernández, P., and González-Bernal, J. J. (2021). Implication of the sensory environment in children with autism spectrum disorder: perspectives from school. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:7670. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147670

Gernsbacher, M. A. (2017). Editorial perspective: the use of person-first language in scholarly writing may accentuate stigma. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 859–861. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12706

Gernsbacher, M. A., Stevenson, J. L., and Dern, S. (2017). Specificity, contexts, and reference groups matter when assessing autistic traits. PLOS ONE 12:e0171931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171931

Gernsbacher, M. A., and Yergeau, M. (2019). Empirical failures of the claim that autistic people lack a theory of mind. Arch. Sci. Psychol. 7, 102–118. doi: 10.1037/arc0000067

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London; New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

Gray, L., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2023). “He's shouting so loud but nobody's hearing him”: a multi-informant study of autistic pupils' experiences of school non-attendance and exclusion. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 8:23969415231207816. doi: 10.1177/23969415231207816

Grummt, M., Lindmeier, C., and Semmler, R. (2022). Die beschulungssituation autistischer schüler:innen: ergebnisse einer elternumfrage. Gemeinsam leben 2, 95–104. doi: 10.3262/GL2202095

Hamadi, S. E., Havik, T., and Holen, S. (2025). “Too little, too late”: youth retrospectives on school attendance problems and professional support received. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 4:1595289. doi: 10.3389/frcha.2025.1595289

Hoferichter, F., and Raufelder, D. (2022). Kann erlebte Unterstützung durch Lehrkräfte schulische Erschöpfung und Stress bei Schülerinnen und Schülern abfedern? Zeitschrift Pädagogische Psychol. 36, 101–114. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000322

Horgan, F., Kenny, N., and Flynn, P. (2023). A systematic review of the experiences of autistic young people enrolled in mainstream second-level (post-primary) schools. Autism 27, 526–538. doi: 10.1177/13623613221105089

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., Allison, C., Smith, P., Baron-Cohen, S., Lai, M.-C., et al. (2017). “Putting on my best normal”: social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 2519–2534. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

Humphrey, N., and Lewis, S. (2008). ‘Make me normal': the views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism 12, 23–46. doi: 10.1177/1362361307085267

Kaplan, D. S., Liu, R. X., and Kaplan, H. B. (2005). School related stress in early adolescence and academic performance three years later: the conditional influence of self expectations. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 8, 3–17. doi: 10.1007/s11218-004-3129-5

Kasari, C., Dean, M., Kretzmann, M., Shih, W., Orlich, F., Whitney, R., et al. (2016). Children with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: a randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57, 171–179. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12460

Kearney, C. A. (2016). Managing School Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers: An Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for Professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199985296.001.0001

Kearney, C. A., Gonzálvez, C., Graczyk, P. A., and Fornander, M. J. (2019). Reconciling contemporary approaches to school attendance and school absenteeism: toward promotion and nimble response, global policy review and implementation, and future adaptability (part 1). Front. Psychol. 10:2222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02222

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., and Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism 20, 442–462. doi: 10.1177/1362361315588200

Knage, F. S. (2023). Beyond the school refusal/truancy binary: engaging with the complexities of extended school non-attendance. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 32, 1013–1037. doi: 10.1080/09620214.2021.1966827

Lai, M.-C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., et al. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 819–829. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

Leslie, R., Oberg, G., Townley, C., Westphal, T., Rogers, L., and Brömdal, A. (2025). “School can't: a conceptual framework for reframing school refusal and recognising school related stress/distress”. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 46, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2025.2552132

Lundin Remnélius, K., and Bölte, S. (2024). Camouflaging in autism: age effects and cross-cultural validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 54, 1749–1764. doi: 10.1007/s10803-023-05909-8

Mailick, M., Bennett, T., DaWalt, L. S., Durkin, M. S., Forbes, G., Howlin, P., et al. (2025). Expanding research on contextual factors in autism research: what took us so long? Autism Res. 18, 710–716. doi: 10.1002/aur.3312

Marco, E. J., Hinkley, L. B. N., Hill, S. S., and Nagarajan, S. S. (2011). Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatr. Res. 69(5 Part 2), 48R−54R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54

Martin-Denham, S. (2022). Marginalisation, autism and school exclusion: caregivers' perspectives. Support Learn. 37, 108–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12398

McGoldrick, E., Munroe, A., Ferguson, R., Byrne, C., and Doherty, M. (2025). Autistic SPACE for Inclusive Education. Neurodiversity 3:27546330251370655. doi: 10.1177/27546330251370655

McGorry, P., Gunasiri, H., Mei, C., Rice, S., and Gao, C. X. (2025). The youth mental health crisis: analysis and solutions. Front. Psychiatry 15:1517533. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1517533

Melvin, G., McKay-Brown, L., Heyne, D., and Cameron, L. (2025). Barriers to School Attendance and Reasons for Student Absence: Rapid Literature Review. Australian Education Research Organisation. Available online at: https://www.edresearch.edu.au/research/research-reports/barriers-school-attendance-and-reasons-student-absence (Accessed November 11, 2025).

Melvin, G. A., Heyne, D., Gray, K. M., Hastings, R. P., Totsika, V., Tonge, B. J., et al. (2019). The Kids and Teens at School (KiTeS) framework: an inclusive bioecological systems approach to understanding school absenteeism and school attendance problems. Front. Educ. 4:61. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00061

Micai, M., Fatta, L. M., Gila, L., Caruso, A., Salvitti, T., Fulceri, F., et al. (2023). Prevalence of co-occurring conditions in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 155:105436. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105436

Milton, D., Gurbuz, E., and López, B. (2022). The ‘double empathy problem': ten years on. Autism 26, 1901–1903. doi: 10.1177/13623613221129123

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem'. Disab. Soc. 27, 883–887. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Morrison, K. E., DeBrabander, K. M., Jones, D. R., Faso, D. J., Ackerman, R. A., and Sasson, N. J. (2020). Outcomes of real-world social interaction for autistic adults paired with autistic compared to typically developing partners. Autism 24, 1067–1080. doi: 10.1177/1362361319892701

Mullally, S. L., Wood, A. E., Edwards, C. C., Connolly, S. E., Constable, H., Watson, S., et al. (2024). Autistic voice: sharing autistic children's experiences and insights. medRXiv. doi: 10.1101/2024.07.22.24310796

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., and Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 104–112. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823

Pellicano, L., Bölte, S., and Stahmer, A. (2018). The current illusion of educational inclusion. Autism 22, 386–387. doi: 10.1177/1362361318766166

Plavnick, J. B., and Hume, K. A. (2014). Observational learning by individuals with autism: a review of teaching strategies. Autism 18, 458–466. doi: 10.1177/1362361312474373

Poon, K. K., Soon, S., Wong, M.-E., Kaur, S., Khaw, J., Ng, Z., et al. (2014). What is school like? Perspectives of Singaporean youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 18, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.693401

Raufelder, D., Lazarides, R., and Lätsch, A. (2018). How classmates' stress affects student's quality of motivation. Stress Health 34, 649–662. doi: 10.1002/smi.2832

Robertson, C. E., and Baron-Cohen, S. (2017). Sensory perception in autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 671–684. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.112

Rosen, T. E., Mazefsky, C. A., Vasa, R. A., and Lerner, M. D. (2018). Co-occurring psychiatric conditions in autism spectrum disorder. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 30, 40–61. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1450229

Sasso, I., and Sansour, T. (2024). Risk and influencing factors for school absenteeism among students on the autism spectrum—a systematic review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. doi: 10.1007/s40489-024-00474-x

Shaw, S. C. K., Brown, M. E. L., Jain, N. R., George, R. E., Bernard, S., Godfrey-Harris, M., et al. (2024). When I say … neurodiversity paradigm. Med. Educ. 59, 466–468. doi: 10.1111/medu.15565

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., and Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 47, 921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f

Sisk, L. M., and Gee, D. G. (2022). Stress and adolescence: vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.005

Snyder, H. R., Young, J. F., and Hankin, B. L. (2019). Chronic stress exposure and generation are related to the p-factor and externalizing specific psychopathology in youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 48, 306–315. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1321002

Speck, K., and Stauvermann, L. (2025). “Multiprofessionelle kooperation im umgang mit schulabsentismus: sozialpädagogische perspektiven, erklärungsansätze, empirische befunde und empfehlungen,” in Interdisziplinäre Kooperation und Schulabsentismus. Absentismus und Dropout, eds. K. Speck and H. Ricking (Wiesbaden: Springer VS). doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-46233-8

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Strübing, J. (2021). Grounded Theory: Zur Sozialtheoretischen und Epistemologischen Fundierung eines Pragmatistischen Forschungsstils. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-24425-5

Sutherland, H. E. A., Fletcher-Watson, S., Long, J., and Crompton, C. J. (2025). ‘A difference in typical values': autistic perspectives on autistic social communication. Scand. J. Disab. Res. 27, 313–329. doi: 10.16993/sjdr.1184

Truman, C., Crane, L., Howlin, P., and Pellicano, E. (2021). The educational experiences of autistic children with and without extreme demand avoidance behaviours. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 28, 57–77. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1916108

Vivanti, G. (2020). Ask the editor: what is the most appropriate way to talk about individuals with a diagnosis of autism? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 691–693. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04280-x

Watts, G., Crompton, C., Grainger, C., Long, J., Botha, M., Somerville, M., et al. (2024). ‘A certain magic' – autistic adults' experiences of interacting with other autistic people and its relation to Quality of Life: a systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis. Autism 29:2239–53. doi: 10.1177/13623613241255811