- Department of Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Technology Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Introduction: The alignment between pre-service teachers’ instructional intentions and their actual classroom enactment remains a critical yet underexplored issue in STEM teacher education. In this study, STEM education is operationalised through science-led inquiry-based practical work that integrates scientific reasoning, mathematical thinking, and problem-solving practices characteristic of integrated STEM pedagogy. The study investigates the intention–enactment gap experienced by pre-service teachers during practicum.

Methods: A cross-sectional research design was employed. Data were collected from a cohort of pre-service teachers and analysed using Bayesian statistical modelling to estimate (i) the average gap between intended and enacted inquiry-based practical work, (ii) variations across demographic subgroups, and (iii) associations with educational and programme-related factors.

Results: Findings indicate that, on average, pre-service teachers intended to implement significantly more inquiry-based practical work than they were able to enact during practicum. Age-related differences were observed, with younger pre-service teachers exhibiting larger intention–enactment gaps, while gender differences were minimal and uncertain. Participation in peer or learning communities emerged as the strongest predictor of alignment, with actively engaged pre-service teachers demonstrating substantially smaller gaps. Conversely, higher self-reported communication skills were unexpectedly associated with larger gaps, potentially reflecting heightened professional aspirations or practicum roles that limited opportunities for hands-on enactment.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the complexity of translating instructional intentions into classroom practice and suggest that individual competencies alone are insufficient to bridge the intention–enactment gap. Deliberately designed, feedback-rich, and collaborative learning environments play a critical role in supporting pre-service teachers to transform pedagogical aspirations into enacted STEM practice. These results offer both theoretical insights and actionable guidance for strengthening STEM teacher preparation programmes.

Introduction

STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education has increasingly been recognized as central to national development and global competitiveness. Beyond transmitting disciplinary knowledge, effective STEM instruction is expected to cultivate 21st-century competencies such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving (Gillies, 2023; Twizeyimana et al., 2024). To achieve these aims, teacher education programs must prepare pre-service teachers who can design and facilitate learning environments that mirror authentic scientific inquiry.

A central pedagogical strategy in this regard is inquiry-based practical work (IBPW), which immerses learners in the practices of science, posing questions, designing and conducting investigations, analyzing data, and communicating evidence-based explanations (Furtak et al., 2012; Kang, 2022; Krajcik and Shin, 2022). Engaging with IBPW during training strengthens pedagogical content knowledge and professional competencies for pre-service teachers, enabling them to manage complex classroom dynamics and foster deep understanding among learners (Leonor, 2015). As such, IBPW is regarded as a cornerstone of contemporary STEM education reforms.

In this study, STEM education is conceptualized as an integrated pedagogical approach enacted primarily through inquiry-based practical work in science classrooms. Authoritative STEM scholarship emphasizes that science frequently serves as the pedagogical anchor for STEM integration, as inquiry-based science instruction naturally incorporates mathematical reasoning, problem-solving, and the use of technological tools (Breiner et al., 2012; Kelley and Knowles, 2016; Honey et al., 2014). Integrated STEM education does not require the simultaneous and equal representation of all STEM disciplines within every lesson; rather, it prioritizes the coordinated development of interdisciplinary competencies through authentic inquiry and problem-based learning experiences (English, 2016; Becker and Park, 2011). Accordingly, the focus on inquiry-based practical work in science during practicum reflects a pragmatic and widely adopted mode of STEM enactment in pre-service teacher education. In this study, this population is referred to as pre-service teachers in STEM education, emphasizing their preparation to enact STEM-oriented curricula through inquiry-based science instruction during practicum.

Despite its potential, the enactment of IBPW is often constrained by systemic and contextual barriers. In many Sub-Saharan African contexts, overcrowded classrooms, limited laboratory facilities, and inadequate teaching resources present formidable challenges (Fitzgerald et al., 2019; Kaggwa et al., 2023; Mumba et al., 2015). These structural limitations hinder in-service teachers and restrict pre-service teachers’ ability to transfer pedagogical intentions into actual classroom practice (Abdurrahman et al., 2019). As a result, there is a persistent gap between what pre-service teachers intend to implement and what they can enact during practicum experiences.

This intention–practice divide represents a critical concern for STEM teacher education. While pre-service teachers often enter training with strong motivation to apply inquiry-based approaches, contextual barriers, limited learning opportunities, and insufficient collaborative supports weaken their capacity for enactment. Bridging this divide requires examining pre-service teachers’ intentions and understanding the individual, contextual, and programmatic factors that shape enactment. Situating this problem within established theoretical perspectives provides a lens for explaining why and how such gaps may be addressed in practice.

Despite widespread adoption of inquiry-based pedagogies in policy and coursework, many pre-service teachers report enacting less practical classroom work than they intend during placements. We address this intention–enactment gap by (i) estimating its average size with uncertainty, (ii) describing variation by gender and age, and (iii) modeling how program-relevant factors jointly relate to the gap. The study’s contribution is a theoretically-integrated, program-usable account that identifies social learning structures, particularly engagement in peer/learning communities, as actionable levers for narrowing the gap in resource-constrained contexts.

Theoretical framework

This study draws on three complementary theoretical frameworks that have been extensively used in education and teacher education research to explain discrepancies between intended and enacted instructional practice: the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the Opportunities to Learn (OTL) framework, and Social Constructivist/Situated Learning perspectives. Each of these frameworks has an established history of application in education and teacher education research, and together they enable a theoretically coherent examination of intention, opportunity, and enactment. Together, these frameworks provide a multi-level explanatory lens for understanding the intention–enactment gap by addressing individual, structural, and sociocultural influences on teaching practice (Ajzen, 1991; Carroll, 1963; Lave and Wenger, 1991).

Recent scholarship in teacher education increasingly draws on multi-level theoretical approaches that integrate intention-based, programmatic, and sociocultural perspectives to explain why ambitious pedagogical reforms, such as inquiry-oriented STEM instruction, often remain unevenly enacted during practicum (Kang and Windschitl, 2018; Sims and Fletcher-Wood, 2021; Keskin et al., 2024).

Theory of planned behavior (TPB)

The TPB is a social-psychological theory that explains behavior as a function of behavioral intentions, which are shaped by attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). Meta-analytic and theoretical syntheses demonstrate that TPB has been widely applied beyond its original formulation, including in educational and professional contexts where individuals face constraints on action (Armitage and Conner, 2001).

In teacher education research, TPB has been used to explain why teachers often fail to enact pedagogical practices they value, particularly when contextual factors reduce perceived behavioral control (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Sniehotta et al., 2014). Studies show that limited resources, institutional norms, and lack of autonomy can weaken the translation of intention into practice, even when attitudes and motivation are strong (Ajzen, 2011). This makes TPB especially relevant for examining inquiry-based practical work (IBPW) during practicum, where pre-service teachers frequently operate under constrained classroom conditions.

In the present study, TPB is employed as an analytic and interpretive framework, rather than as a strict instrument-development protocol. While classical TPB applications often involve a qualitative elicitation phase followed by structured questionnaire construction (Ajzen, 2006), education researchers have also used TPB conceptually to interpret intention–action gaps without replicating the full elicitation methodology (Armitage and Conner, 2001; Sniehotta et al., 2014).

Opportunities to learn (OTL)

While TPB focuses on individual intentions and perceived control, the OTL framework foregrounds the structural and instructional conditions that enable or constrain enactment. Originally articulated by Carroll (1963), OTL has been widely operationalized in education research to examine how access to content, instructional time, and learning experiences shapes educational outcomes. Subsequent work has applied OTL to teacher education, demonstrating that access to aligned coursework, microteaching, supervised practicum, and feedback opportunities significantly influences pre-service teachers’ instructional preparedness (Schmidt et al., 1997; Tatto et al., 2012). Research in STEM and science teacher education further shows that uneven OTL contributes to variability in teachers’ ability to enact inquiry-based pedagogies, even when intentions are strong (Kang and Windschitl, 2018). In this study, OTL provides a program-level explanatory lens for interpreting how educational experiences, such as exposure to microteaching, participation in peer learning communities, and opportunities to practice IBPW, shape pre-service teachers’ capacity to enact their intentions during practicum.

Social constructivist and situated learning perspectives

To situate individual intention and structural opportunity within authentic teaching contexts, the study also draws on Social Constructivist and Situated Learning perspectives. Social Constructivist theory emphasizes that learning occurs through social interaction and scaffolding within cultural and institutional contexts (Vygotsky, 1978). Situated Learning theory further argues that professional learning is embedded in participation within communities of practice, rather than acquired solely through formal instruction (Lave and Wenger, 1991). In teacher education, these perspectives have been widely used to explain how novice teachers learn instructional practices through legitimate peripheral participation during practicum experiences (Wenger, 1998). Empirical studies show that peer collaboration, mentoring, and shared reflection play a critical role in shaping how pre-service teachers interpret classroom challenges and adapt pedagogical strategies (Hammerness et al., 2005; Opfer and Pedder, 2011). Within the context of IBPW, Social Constructivist and Situated Learning perspectives help explain why engagement in peer and learning communities can mediate the translation of intention into classroom action, particularly in resource-constrained settings where individual capacity alone is insufficient.

The integration of TPB, OTL, and Social Constructivist/Situated Learning perspectives is theoretically justified by their complementary explanatory roles. TPB addresses individual-level processes of intention formation and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991); OTL captures program-level conditions that enable or constrain enactment (Carroll, 1963; Tatto et al., 2012); and Social Constructivist/Situated Learning theories explain the sociocultural mechanisms through which teaching practices are learned, supported, and sustained (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). Together, these frameworks provide a coherent multi-level lens for interpreting the Bayesian models used in this study, allowing demographic characteristics and educational supports to be examined jointly as predictors of the intention–enactment gap in inquiry-based practical work.

Literature review

A growing body of research underscores the importance of preparing pre-service teachers to enact inquiry-based practices that foster STEM competence in diverse and often resource-constrained classrooms. Within STEM teacher education, inquiry-based science instruction is widely recognized as a central mechanism for enacting integrated STEM pedagogy, particularly in pre-service contexts where practicum experiences emphasize hands-on investigation, experimentation, and problem solving (Kelley and Knowles, 2016; Becker and Park, 2011). Conceptual syntheses of integrated STEM education further identify inquiry and authentic problem contexts as defining features of effective STEM teaching and learning environments (English, 2016). The literature highlights four main strands relevant to this study: (i) the role of inquiry-based practical work (IBPW) in developing STEM competencies, (ii) the influence of opportunities to learn (OTL) in shaping pre-service teacher readiness, (iii) the challenges of implementing inquiry approaches in under-resourced environments, and (iv) the persistent gap between teachers’ intentions and enacted practices. Reviewing these strands provides a foundation for understanding the conditions under which pre-service teachers’ intentions are translated into classroom practice, and where they are likely to falter.

Recent reviews and empirical studies in STEM teacher education emphasize that the success of inquiry-oriented reforms depends not only on teachers’ beliefs and knowledge, but critically on their capacity to enact these practices during practicum under real classroom constraints (Shernoff et al., 2017; Krajcik and Shin, 2022; Strat et al., 2023).

Inquiry-based practical work and STEM competence

Inquiry-based practical work (IBPW) has emerged as a cornerstone of effective STEM education because it immerses learners in authentic scientific practices such as posing questions, designing investigations, analyzing data, and communicating findings (Furtak et al., 2012; Krajcik and Shin, 2022). By actively engaging students in inquiry processes, IBPW develops higher-order thinking, problem-solving, and conceptual understanding, essential STEM learning competencies (Gillies, 2023; Strat et al., 2023). Competence in IBPW is particularly significant for pre-service teachers because it strengthens pedagogical content knowledge, fosters adaptability in diverse classrooms, and enhances professional identity as future STEM educators (Leonor, 2015; National Research Council, 2019).

Yet, despite its potential, the enactment of IBPW presents notable challenges. Pre-service teachers often struggle with the pedagogical and classroom management demands of inquiry lessons, particularly in large class sizes and scarce resources (Akuma and Callaghan, 2019; Ramnarain, 2016). These challenges are amplified in Sub-Saharan Africa, where inadequate facilities and limited teacher preparation opportunities frequently constrain the ability to implement IBPW effectively (Kaggwa et al., 2023). Such tensions highlight the need to examine pre-service teachers’ intentions to adopt IBPW and the conditions that enable or inhibit enactment.

Opportunities to learn in STEM teacher education

The concept of opportunities to learn (OTL) offers a valuable lens for understanding differences in pre-service teachers’ preparedness for IBPW. OTL encompass the quantity and quality of structured instructional opportunities available to learners, including coursework, microteaching, guided observations, and mentoring (Carroll, 1963; Kurz and Elliott, 2011). In STEM teacher education, OTL shapes pedagogical and content knowledge development, influences confidence, and prepares pre-service teachers to enact inquiry-based strategies (Connolly et al., 2023; Gerhard et al., 2023). Evidence suggests that when pre-service teachers experience abundant and structured OTL, they are more likely to enact their intentions successfully (Berisha and Vula, 2021; Kang and Windschitl, 2018).

Conversely, limited OTL, such as inadequate exposure to microteaching, weak supervision during practicum, or lack of collaboration, constrain pre-service teachers’ ability to translate intentions into practice (Mutseekwa et al., 2024). This resonates with the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), which posits that intentions alone are insufficient predictors of action if perceived behavioral control is low. OTL can therefore be conceptualized as structural enablers that increase perceived control and support the translation of intention into enacted practice. In this study, categories such as observation of IBPW implementation (OIBPWTP) and simulated teaching in methods courses (STMC) represent specific opportunities to learn, while competencies such as improvisation (CIMNA) and substitution of materials (CSPM) reflect behavioral control factors aligned with the Theory of Planned Behavior. For clarity and interpretation, these categories are later synthesized into two overarching conceptual subthemes: Participation in Peer Learning Communities, representing collaborative program-level supports, and Planned Behavior for Implementing IBPW, representing individual-level competencies and behavioral control factors. This conceptual grouping provides a theoretical bridge to interpreting the results and discussion that follow. Having established these conceptual foundations, it is also important to consider the contextual realities that shape pre-service teachers’ experiences.

Challenges in under-resourced classrooms

In many Sub-Saharan African contexts, pre-service teachers face structural barriers that make it difficult to enact IBPW. Common challenges include overcrowded classrooms, inadequate laboratory facilities, insufficient instructional materials, and limited institutional support (Kim et al., 2013; Nemadziva et al., 2023; Mumba et al., 2015). These conditions often push teachers toward didactic approaches that are easier to manage but less effective in promoting inquiry and conceptual understanding (Fitzgerald et al., 2019). For pre-service teachers, the problem is compounded by inexperience: they must simultaneously learn to improvise with scarce resources and manage complex classroom dynamics during practicum placements (Abdurrahman et al., 2019). Evidence from STEM teacher education research indicates that although pre-service teachers often express strong intentions to implement inquiry-oriented STEM practices, enactment during practicum is frequently constrained by organizational, pedagogical, and contextual factors (Shernoff et al., 2017; Stohlmann et al., 2012). These studies highlight the need for structured opportunities, mentoring, and collaborative learning environments to support the translation of STEM-oriented intentions into classroom practice. This aligns with Situated Learning Theory, which emphasizes that teacher development is shaped by participation in authentic contexts that may either facilitate or constrain learning.

Some studies have suggested that resource improvisation and the creative use of local materials can partially mitigate these challenges (Photo, 2025; Sumida and Kawata, 2021). However, evidence indicates that such adaptations are rarely sufficient to sustain rigorous inquiry processes. Instead, these barriers contribute to the persistence of an intention–practice divide, where pre-service teachers enter classrooms with positive intentions but cannot fully realize them. This aligns with Situated Learning Theory (Lave and Wenger, 1991), which emphasizes that teacher development is shaped by participation in authentic contexts that may either facilitate or constrain learning.

The intention–practice gap in teacher education

The gap between what teachers intend to do and what they actually enact in classrooms has been documented extensively across education research. Psychological accounts explain that while intentions are necessary precursors to action, contextual constraints and low perceived control often prevent intentions from being enacted (Ajzen, 1991; Malaguti et al., 2020). This problem is especially pronounced for pre-service teachers because they are still developing professional skills and must adapt to challenging practicum contexts (Keskin et al., 2024).

Studies also highlight that individual capacities such as self-efficacy and motivation have only modest effects on bridging the intention–practice divide compared to structural and social supports (Bardach and Klassen, 2021). Collaborative environments, structured feedback, and professional learning communities have significantly improved teachers’ likelihood of enacting intended practices (Demir, 2021; Sims and Fletcher-Wood, 2021). Finefter-Rosenbluh and Power (2023) further emphasize that communities of practice can reduce feelings of isolation and promote ethical noticing, enabling pre-service teachers to anticipate and address classroom challenges more effectively during practicum experiences. In the case of STEM teacher education, where IBPW requires advanced instructional orchestration, the gap between intention and enactment is particularly wide if pre-service teachers lack robust opportunities to learn and collaborative support systems.

The literature demonstrates a consistent pattern: pre-service teachers in STEM education often value IBPW and express strong intentions to adopt it, but their enactment is contingent on structured OTL, social supports, and enabling contexts. Systemic barriers in under-resourced classrooms exacerbate this gap, while existing studies remain fragmented, focusing on implementation challenges or teachers’ beliefs without linking the two. Moreover, few studies quantify how demographic factors such as gender and age interact with program-level supports to shape the intention–practice gap. These gaps in the literature form the basis for the present study. In this study, the term “pre-service teachers in STEM education” is used to refer to pre-service teachers preparing to implement STEM-oriented curricula, where inquiry-based science instruction constitutes a primary mode of STEM enactment during practicum. This definition reflects a pragmatic conception of STEM education as an integrated pedagogical approach, rather than a requirement for the simultaneous teaching of all STEM disciplines in every instructional context.

Despite growing interest in inquiry-based teaching and opportunities to learn, limited research systematically investigates the intention–enactment gap among pre-service teachers in STEM education. Most existing studies are either descriptive or focus on isolated dimensions such as teacher beliefs or resource constraints, without explicitly linking intentions to enacted classroom practice or modeling how demographic and programmatic factors jointly shape this gap. Furthermore, empirical work in under-resourced Sub-Saharan African contexts remains particularly scarce, and few studies employ advanced statistical techniques, such as Bayesian analysis, that allow for nuanced modeling of multiple influencing factors while incorporating uncertainty.

Taken together, these limitations reveal a need for research that quantifies the intention–enactment gap, examines how it varies across pre-service teacher characteristics, and identifies program-relevant factors associated with alignment between intention and practice. To address these gaps, this study examines the magnitude of the intention–enactment gap in inquiry-based practical classroom work among pre-service teachers in STEM education, explores variation by demographic characteristics (gender and age), and models how educational supports and competencies jointly relate to this gap. Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research questions.

Research questions

1. What is the average difference between intended and enacted practical classroom work among pre-service teachers in the cohort?

2. How does the intention–enactment gap vary by demographic factors such as age and gender?

3. When considered jointly, how are confidence, participation in peer/learning communities, microteaching exposure, content knowledge, communication skills, planning/management, and inquiry/practical skills associated with the gap?

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional study using a cohort of student teachers enrolled in a primary teacher education program. The focus was on the difference between what participants reported intending to implement and what they reported actually enacting in practical classroom work during their placements. Analyses follow the Bayesian models reported in the Results section; no additional technical detail is introduced here.

Participants and sampling

A total of 65 pre-service teachers enrolled in a primary teacher education program participated in this study. The participants were specializing in STEM-related subjects across Grades 3–7 at a Zimbabwean teacher education institution during the 2022/2023 academic session. Eligibility criteria included current enrolment in the program and completion of the practicum placement cycle required to report both intended and enacted practical classroom work using the study instrument. Participation was voluntary with informed consent; data were de-identified prior to analysis and analyzed under approved program policies. Subgroups were recorded for gender and age bands (e.g., <20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39) to permit descriptive comparisons. Exact subgroup counts are available in the results tables; small cell sizes at older ages motivate cautious interpretation.

Instrument development and adaptation

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered by the program during or immediately after the practicum period. The instrument was adapted from established literature on inquiry-based practical work, teacher enactment of inquiry, and opportunities to learn, with modifications to reflect the realities of under-resourced classroom contexts common in the study setting (e.g., Carroll, 1963; Furtak et al., 2012; Ramnarain, 2016; Kang and Windschitl, 2018).

The questionnaire comprised closed-ended Likert-type items and open-ended questions. Closed-ended items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and were designed to capture two related but distinct constructs: intended inquiry-based practical work (intended IBPW) and enacted inquiry-based practical work (enacted IBPW). Open-ended items invited participants to describe inquiry activities implemented, strategies for improvisation, and challenges encountered during teaching practice, providing contextual insight into enactment.

The instrument was specifically designed to align with the study’s research questions by capturing both pre-service teachers’ intended use of inquiry-based practical work and their reported enactment of these practices during practicum. Items addressing intention focused on planned instructional actions prior to classroom implementation, while enactment items prompted reflective reporting on what was actually carried out in real classroom contexts. This dual structure enabled the operationalization of the intention–enactment gap required to address Research Question 1, while the inclusion of demographic indicators and program-relevant learning experiences supported analyses related to Research Questions 2 and 3.

Measures and construct operationalization

The primary outcome variable was the intention–enactment gap, operationalized as the individual-level difference between intended and enacted inquiry-based practical work (IBPW) scores (intended minus enacted). Positive values indicate instances in which intended implementation exceeded reported classroom enactment.

Guided by the study’s theoretical framework, questionnaire items were organized into conceptually coherent constructs informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Opportunities to Learn (OTL) framework. Program-level learning experiences aligned with OTL were grouped under the construct Participation in Peer Learning Communities, comprising observation of IBPW implementation during teaching practice (OIBPWTP), implementation of IBPW during teaching practice (IIBPWTP), theory learning in methods courses (TMLC), simulated teaching in methods courses (STMC), and observation of mentor teachers’ improvisation during teaching practice (OMTITP).

Individual competencies and behavioral control factors aligned with TPB were grouped under the construct Planned Behavior for Implementing IBPW. This construct included competence to improvise when materials are unavailable (CIMNA), conduct demonstrations without prescribed materials (CCOMNA), substitute prescribed materials with locally available resources (CSPM), and substitute prescribed IBPW activities with alternative activities addressing equivalent concepts (CSPIBPWA). Additional predictors included confidence in teaching methods, content knowledge, communication skills, and classroom planning and management. All predictors were z-standardized (M = 0, SD = 1) prior to analysis to facilitate comparison of regression coefficients across factors.

Although both intention and enactment were measured through self-report, this approach is consistent with prior research on intention–behavior gaps, which commonly relies on reflective self-report to capture enacted practice when direct observation is not feasible (Ajzen, 1991; Malaguti et al., 2020). In this study, enactment items were explicitly framed to reference actions taken during practicum rather than planned behavior, thereby distinguishing retrospective reporting of classroom practice from prospective intention. While self-reports may be subject to calibration bias, the focus of the analysis is on within-participant differences between intended and enacted practice, which mitigates concerns about absolute score inflation. This makes the instrument suitable for examining relative alignment and misalignment between intention and enactment, consistent with the study’s theoretical framing and research questions.

Reliability and validity

Internal consistency reliability of the composite scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values above 0.79 considered acceptable for research purposes. Reliability analyses were conducted separately for intended IBPW, enacted IBPW, and program-relevant predictor scales. Content validity was supported through alignment of questionnaire items with established theoretical frameworks and empirical literature on inquiry-based practical work, teacher learning, and opportunities to learn. Construct validity was supported by the theoretical distinction between intention and enactment and by modeling these constructs as related but analytically separable. Contextual validity was enhanced through adaptation of items to reflect the practical realities of teaching practice in resource-constrained school environments.

Model description

We estimated three related models that address the research questions and keep interpretation aligned to program decisions. First, to describe the overall intention–enactment difference, we modeled individual gaps as normally distributed around a single cohort mean with a common variance:

Here, is the gap for participant , is the cohort average gap, and is the residual variance.

Second, to summarize differences by gender and age bands, we used a parallel normal model with group-specific means and a common variance:

where indexes the participant’s group (e.g., gender or age band). Group estimates report each with uncertainty.

Third, to examine associations with educational factors considered together, we fit a linear regression of the gap on standardized predictors:

Because predictors were standardized, each coefficient expresses the expected change in the gap (instrument units) for a one standard deviation increase in factor , holding other factors constant.

Priors and rationale

For the overall mean and group-mean models, we used weak, default choices that place minimal structure on the mean and avoid overconfidence about the variance. Specifically, we used a non-informative prior for the mean and a standard Jeffreys prior for the variance, which yields familiar Student’s summaries for and . This choice reflects limited prior knowledge about the scale of the gap in this cohort and is common in introductory Bayesian estimation of means.

We used weakly informative priors for the multivariable regression that stabilize estimation while keeping a wide range of effects plausible given the small cohort size and correlation among predictors. The intercept had a zero-centered normal prior with variance 10, the slope coefficients had independent zero-centered normal priors with variance 1, and the residual variance had a conjugate inverse-gamma prior with shape 2 and scale 1. These settings say that very large effects are a priori unlikely, but moderate positive or negative associations remain quite plausible. With standardized predictors, a normal prior with variance 1 for each places most prior mass on effects within roughly one instrument unit per predictor standard deviation, which is intentionally broad for educational contexts. The variance prior is weak relative to the data and serves primarily to ensure a proper posterior.

Estimation and reporting

All models admit closed-form posteriors under these priors. We summarized each parameter by drawing from the corresponding posterior distribution and reporting posterior means, 95% credible intervals, and posterior probabilities of direction (for example, ). For group comparisons, we report each group mean with its interval rather than relying on a single difference score, which helps avoid over-interpretation when groups are small.

Procedures

Following routine program procedures, participants completed the instrument during or immediately after the practicum period. Data were de-identified prior to analysis. Ethics approval and consent procedures are reported in the policy statements.

Diagnostics and robustness

Posterior draws were inspected for stability and reasonable coverage. Given the conjugate structure, sampling pathologies were not expected. Posterior predictive checks were used informally to confirm that the normal likelihood reasonably approximated the gap distribution. We also conducted simple prior-scale sensitivity checks for the regression by halving and doubling the prior variances on the intercept and slopes; substantive conclusions did not change. Because the study is cross-sectional and observational, inferences are associative, and we avoid causal claims.

Data analysis

Bayesian analysis was used to estimate group differences and examine the intention–enactment gap predictors. This approach allows for probability statements that are directly interpretable for decision-making in teacher education contexts. Bayesian modeling was selected over traditional frequentist methods because it provides more nuanced interpretations of uncertainty, especially in smaller cohorts typical of pre-service teacher education programs (Huang and Kaplan, 2024). Weakly informative priors were specified to regularize estimates, and results are reported as posterior means with 95% credible intervals. Analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4) with packages such as brms. Predictors were standardized to allow direct comparison of effect sizes. Model fit was assessed using Leave-One-Out cross-validation (LOO-CV) and posterior predictive checks.

Two focal models were estimated:

1. A baseline model estimating the average intention–enactment gap.

2. A multivariable model examining how demographic factors (e.g., age, gender) and educational predictors (e.g., peer community engagement, communication skills) were associated with the gap.

Results

This section presents the findings of the Bayesian analyses in relation to the three research questions. First, we report the estimated average difference between intended and enacted inquiry-based practical classroom work across the cohort. Second, we examine variation in the intention–enactment gap by demographic characteristics, specifically age and gender. Finally, we present results from the multivariable model assessing how program-relevant educational factors are jointly associated with the gap.

Average gap

We examine the question: What is the average difference between intended and actual implementation of practical classroom work across participants? We estimate the mean of the individual differences (intended minus actual) using a Bayesian Normal model with unknown variance and a non-informative prior, summarizing the posterior with a mean, 95% credible interval, and the posterior probability that the average difference is greater than zero.

As shown in Table 1, the posterior mean is (95% credible interval ; ; ). Evidence supports a positive, moderate average difference: roughly 99% of posterior mass lies above zero. Although expressed in instrument units and averaging over participants, the central tendency indicates intentions exceed practice. We next examine variation by gender and age and associations with educational factors.

Group differences

We ask how the gap varies by gender and age. Table 2 summarizes group means by gender and age bands. Estimates for men and women are close (means and ). For both genders, the 95% intervals extend from slightly below zero to moderately above it (men ; women ). In practical terms, values around zero remain plausible for each gender, so a systematic gender difference is not evident in these data. Age shows a clearer structure. The two youngest groups have positive averages with ranges that sit above zero: and ages 20 to 24 For ages 25 to 29, the range spans negative to positive values meaning the typical average for this group could be small in either direction. For ages 30 to 34 and 35 to 39, the ranges are wide and straddle zero ( and ), reflecting few cases; their average gap may be close to zero. Age, more than gender, accounts for the observed variation.

Predictors of the gap

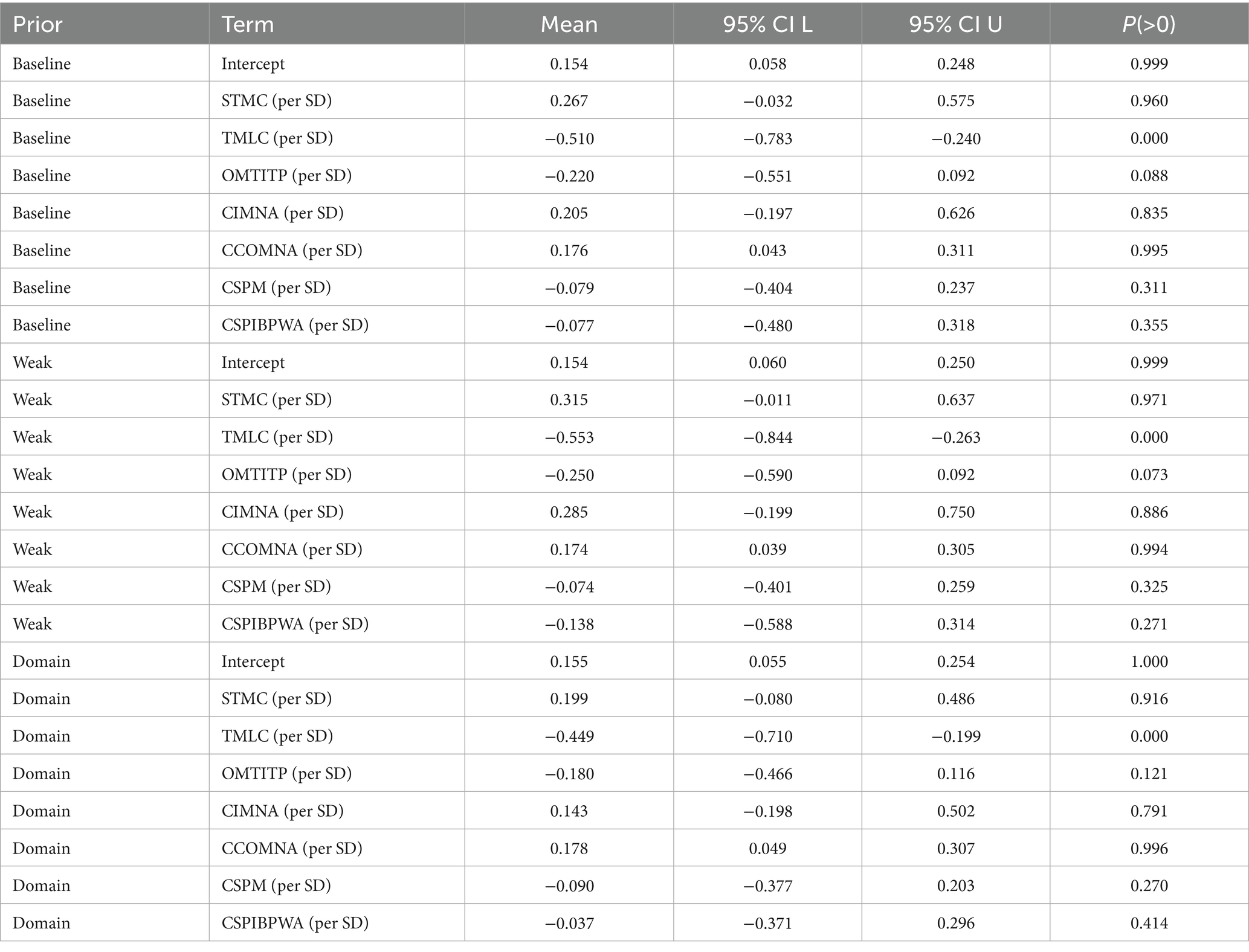

We examine the question: Which educational factors are associated with the difference between intentions and practice when considered together? The joint associations of educational factors with the gap are presented in Table 3. We fit a Bayesian linear regression of the individual difference on confidence in teaching methods, participation in peer or learning communities, micro-teaching exposure, content knowledge, communication skills, classroom planning and management, and inquiry-based practical skills. Predictors are standardized, so coefficients reflect the change in the difference for a one standard deviation increase in each factor, holding the others constant. We use a conjugate Normal-inverse-gamma prior with a weak variance prior, yielding posterior means, 95% credible intervals, and posterior probabilities that coefficients are positive.

In the multivariable model with standardized predictors (Table 3), two associations stand out. Participation in peer or learning communities is associated with a smaller gap (mean ; 95% interval ), while communication skills are associated with a larger gap (mean ; ). For the remaining factors, the intervals include zero; for example, content knowledge , confidence in teaching methods , and micro-teaching exposure , indicating that small positive and small negative values are both compatible with the data. Coefficients are per standard deviation; given and correlation among predictors, these magnitudes should be read as modest.

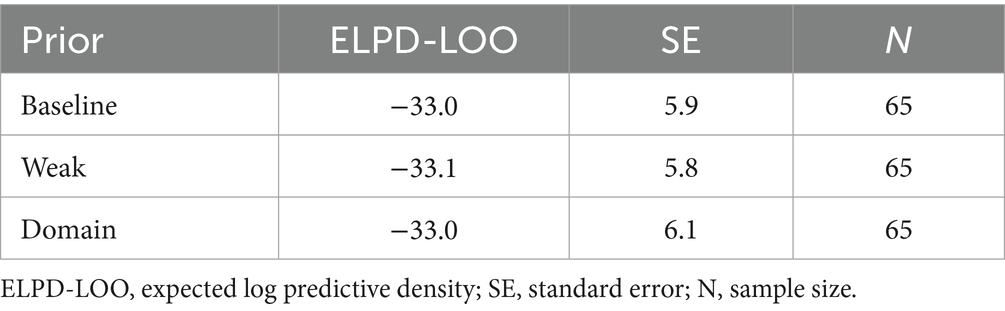

Prior sensitivity and predictive checks

We conducted prior sensitivity analyses and both prior and posterior predictive checks for the regression model with standardized predictors to assess robustness. We considered a grid of proper, conjugate priors that span: (a) the manuscript’s baseline setting (broad intercept, unit-scale slopes, weak variance prior), (b) a weaker variant (wider slope scales and variance prior), and (c) a domain-informed variant (tighter slope scales and a slightly tighter variance prior). We refit the model for each configuration and summarize key parameters and out-of-sample performance. Prior predictive checks (Table 4) examined simulated outcomes before seeing the data. Across priors, the prior predictive distributions placed mass on plausible outcome ranges (center and spread), indicating no major prior–data conflict at the scales used. The distribution of simulated outcomes under these prior settings is visualized in Figure 1, which overlays the weak, domain, and robust priors.

Figure 1. Prior predictive overlays for weak, domain, and robust priors. Overlays illustrate differences in outcome distributions under alternative prior configurations for comparison with observed data.

Across the prior grid, the direction of the two main associations was stable: higher participation in peer or learning communities remained associated with a smaller gap. In contrast, higher communication skills remained associated with a larger gap. Posterior means shifted modestly under weaker versus tighter priors, but conclusions did not change, and credible intervals showed substantial overlap (Table 5). For the remaining factors, posterior intervals largely continued to include zero across priors, consistent with small or context-dependent associations in this cohort. The full sensitivity table is provided in the Table 6.

For out-of-sample validation, leave-one-out cross-validation based on the conjugate posterior predictive yielded similar expected log predictive densities across priors; observed differences were small relative to their uncertainty (Table 6), indicating comparable predictive adequacy. Posterior calibration and diagnostic checks are shown in Figure 2, with LOO–PIT on the left and PSIS Pareto–k diagnostics on the right.

Figure 2. Posterior calibration (LOO–PIT; left) and PSIS Pareto–k diagnostics (right), baseline prior. LOO–PIT, leave-one-out probability integral transform; PSIS, Pareto-smoothed importance sampling.

Taken together, the prior predictive coverage, posterior predictive fit, and prior sensitivity results support the robustness of the primary findings to reasonable prior choices in this setting.

Discussion

This study examined the intention–enactment gap in practical classroom work among pre-service teachers and identified demographic and program-related factors that shape the translation of pedagogical intentions into classroom practice. Using a Bayesian modeling approach, the findings provide a nuanced account of the magnitude of this gap, its demographic variation, and the program-relevant educational factors associated with alignment between intention and enactment in a resource-constrained teacher education context.

Magnitude of the intention–enactment gap

Across the cohort, pre-service teachers reported higher intended than enacted inquiry-based practical classroom work, indicating a modest but credible intention–enactment gap (posterior mean ≈ 0.15; 95% CrI [0.02, 0.28]). This finding is consistent with a substantial body of teacher education research demonstrating that novice teachers’ pedagogical aspirations frequently exceed what they are able to enact during practicum placements (Ajzen, 1991; Chen et al., 2024; Keskin et al., 2024).

From the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior, this pattern reflects situations in which favorable attitudes and strong intentions are insufficient to overcome contextual constraints that reduce perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). In under-resourced classrooms, limited materials, overcrowded conditions, and restricted instructional autonomy can hinder enactment even when pre-service teachers value inquiry-based pedagogies. Meta-analytic and review evidence further suggests that many individual teacher attributes, such as motivation and self-efficacy, show small and context-dependent relationships with enacted practice, particularly in novice populations (Bardach and Klassen, 2021).

Interpreted through Opportunities to Learn and Situated Learning perspectives, the observed gap also signals a misalignment between what pre-service teachers are encouraged to aspire to during coursework and the affordances of their practicum environments. Without sustained, supported opportunities to enact inquiry-based practices in authentic contexts, intentions may outpace practice, producing the pattern observed in this study (Carroll, 1963; Lave and Wenger, 1991).

Demographic variation in the intention–enactment gap

Demographic variation in the intention–enactment gap was more evident across age groups than across gender. Younger pre-service teachers exhibited clearer positive gaps, whereas estimates for older groups were imprecise and centered closer to zero. The absence of meaningful gender differences aligns with prior research suggesting that enactment of inquiry-based practices is shaped more strongly by contextual opportunities and professional learning experiences than by gendered dispositions (Finefter-Rosenbluh and Power, 2023).

One plausible explanation for the age-related pattern is a cohort effect, whereby younger pre-service teachers may be more strongly influenced by contemporary pedagogical discourses emphasizing inquiry-based and learner-centered instruction. These discourses can elevate instructional aspirations without necessarily equipping novices with the experiential knowledge required to enact inquiry under real classroom constraints. From a Social Constructivist and Situated Learning perspective, younger pre-service teachers are more likely to occupy peripheral positions in practicum communities, limiting their authority and capacity to enact ambitious instructional practices (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

Older pre-service teachers, by contrast, may draw on prior classroom exposure or pragmatic expectations that temper both intention setting and enactment. However, given the imprecision of estimates for older age groups, these interpretations should be treated cautiously. Overall, the findings suggest that demographic characteristics influence enactment indirectly, through experience and access to supportive learning contexts, rather than determining outcomes in isolation.

Program-relevant educational factors associated with the gap

When considered jointly, program-relevant educational factors showed differential associations with the intention–enactment gap. Participation in peer and learning communities emerged as the strongest and most robust factor associated with smaller gaps, while communication skills were associated with larger gaps. Other factors—microteaching exposure, content knowledge, and inquiry/practical skills—showed weak or statistically uncertain direct associations.

Peer and learning communities

The strong association between engagement in peer and learning communities and reduced intention–enactment gaps converges with extensive evidence highlighting the role of collaboration and social capital in teacher learning and instructional change (Demir, 2021; Schuster et al., 2021; Sims and Fletcher-Wood, 2021). In pre-service contexts, communities of practice can buffer isolation, support ethical noticing, and provide anticipatory guidance that makes desired practices feel achievable (Finefter-Rosenbluh and Power, 2023).

From an Opportunities to Learn perspective, peer and learning communities function as structured program-level supports that provide repeated opportunities for rehearsal, feedback, and reflection. Social Constructivist and Situated Learning theories further explain how such communities enable guided participation, allowing pre-service teachers to move from peripheral observation toward confident enactment of inquiry-based practices (Vygotsky, 1978; Lave and Wenger, 1991). The magnitude of this association suggests that strengthening collaborative structures within practicum represents a highly actionable lever for narrowing the intention–enactment gap.

Communication skills

The positive association between communication skills and a larger intention–enactment gap warrants careful interpretation. Stronger communicators may articulate more ambitious instructional plans, raising intended practice without a corresponding increase in enacted practice, a calibration effect consistent with research linking goal articulation and self-regulation to heightened expectations (Hunter and Springer, 2022). Communication strengths may also align with practicum role specialization that prioritizes discourse-oriented tasks over hands-on practical work, inflating the gap captured by the instrument.

From a Social Constructivist perspective, these findings suggest that communication skills must be developed alongside scaffolded opportunities for enactment. Without guided mentoring and collaborative participation, strong communication may amplify aspirations without reducing enactment constraints.

Microteaching, content knowledge, and inquiry/practical skills

Although microteaching exposure, content knowledge, and inquiry/practical skills were specified as key predictors in Research Question 3, their partial associations with the intention–enactment gap were weak and statistically uncertain. This does not suggest that these factors lack educational importance. Rather, it indicates that their influence on enactment may be indirect or conditional on contextual supports, a pattern reported in prior teacher education research (Opfer and Pedder, 2011; Kang and Windschitl, 2018).

Microteaching typically occurs in simulated, low-stakes environments and supports instructional rehearsal and confidence development; however, studies show that such experiences often transfer imperfectly to complex, resource-constrained classroom settings (Grossman et al., 2009; Tatto et al., 2012). Similarly, strong content knowledge and inquiry/practical skills are widely recognized as necessary foundations for inquiry-based teaching, yet evidence suggests that they do not automatically translate into enactment when material constraints, time pressure, and classroom management demands are high (Furtak et al., 2012; Ramnarain, 2016).

From an Opportunities to Learn and Situated Learning perspective, these competencies require sustained, supported engagement in authentic teaching contexts to influence practice (Carroll, 1963; Lave and Wenger, 1991). Social scaffolding through mentoring and peer collaboration is therefore critical for converting individual capacities into enacted inquiry-based practical work, helping to explain their limited direct effects in the multivariable models.

Mechanisms and theoretical integration

The findings are best explained through the complementary use of the three theoretical frameworks guiding this study, each illuminating a distinct aspect of the intention–enactment gap. From the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) perspective (Ajzen, 1991), the modest but credible average gap identified in RQ1 and the weak partial effects of several individual competencies in RQ3 indicate that strong intentions alone were insufficient for enactment under constrained practicum conditions. Limited resources and restricted instructional autonomy likely reduced perceived behavioral control, weakening the translation of intention into classroom action. In contrast, participation in peer and learning communities may have enhanced perceived control by providing social support, modeling, and shared resources, explaining its strong association with smaller gaps.

The Opportunities to Learn (OTL) framework further clarifies why some educational experiences mattered more than others. Although microteaching exposure, content knowledge, and inquiry/practical skills are central to teacher preparation, their weak and statistically uncertain direct effects suggest that isolated or simulated learning opportunities do not readily transfer to complex classroom contexts. Engagement in peer and learning communities, however, represents richer, more continuous opportunities for rehearsal, feedback, and contextualized practice, which are more likely to support enactment.

Social Constructivist and Situated Learning perspectives explain how these opportunities become actionable. Through guided participation and collaboration in communities of practice, pre-service teachers can move from peripheral involvement toward confident enactment of inquiry-based practices (Lave and Wenger, 1991). The larger gaps observed among younger pre-service teachers are consistent with this interpretation, reflecting greater dependence on social scaffolding during early professional development.

Taken together, the findings suggest that the intention–enactment gap is shaped less by deficits in individual motivation or skill than by the availability of socially embedded, contextually aligned learning opportunities. Reducing this gap therefore requires teacher education programs to integrate individual preparation with sustained, collaborative practicum structures that expand perceived control and support authentic enactment.

Strengths and limitations

This study integrates Bayesian estimation of group means with a multivariable model of standardized educational factors, enabling interpretable probability statements and effect sizes commensurate across predictors. The use of weakly informative priors and reporting of posterior probabilities provides transparent evidence for decision-making in small cohorts. We also translate standardized coefficients to practical differences (e.g., a two-SD increase in learning-community participation corresponds to about one unit reduction in the gap), aiding program interpretation.

Nonetheless, limitations remain. First, measures are self-reported differences; self-report can systematically overstate intentions and understate enactment for some respondents (calibration bias), potentially inflating gaps among those who set higher standards (e.g., strong communicators). Second, the cross-sectional design and correlated predictors limit causal claims; observed associations could reflect selection (e.g., self-selection into learning communities) or unmeasured confounding (e.g., mentor quality, placement constraints). Third, subgroup estimates for older age groups are imprecise because of small cell sizes, which are credible intervals that straddle zero, caution against over-interpretation. Fourth, constructs like “communication skills” may capture multiple underlying traits (self-presentation, reflective articulation) and practicum role assignment; without observational triangulation, we cannot locate the association source. Fifth, we did not model school/mentor clustering; multi-level Bayesian models could sharpen inferences where data permit. Finally, the instrument’s scale is cohort-specific; generalization to other programs warrants replication.

Conclusion

This study revealed a modest but meaningful gap between pre-service teachers’ intentions and their enactment of inquiry-based practical work during the practicum. This persistent gap underscores the ongoing challenge of translating plans into practice in STEM teacher education. Younger teachers displayed larger gaps than their older peers, while gender differences were minimal, suggesting that contextual and structural factors play a more significant role than demographics alone. A key finding was the strong association between active participation in peer or learning communities and smaller intention–enactment gaps. These communities provide critical social and professional supports, enabling pre-service teachers to move from aspiration to action. In contrast, communication skills were unexpectedly linked to larger gaps, possibly reflecting heightened aspirations or specialized practicum roles that reduce direct engagement with practical tasks. Collectively, these results highlight that collaborative, contextual supports are more effective for fostering enactment than individual competencies alone.

Drawing on the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Opportunities to Learn framework, and Social Constructivist/Situated Learning perspectives, this study demonstrates how individual intentions, program-level structures, and social processes interact to shape enactment. The Bayesian modeling approach provided nuanced probabilistic interpretations directly actionable for program design and improvement, especially in small cohort contexts typical of teacher education. These findings should be interpreted with caution. Self-reported data may introduce bias, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and small subgroup sizes reduce precision. Future research should employ longitudinal and experimental designs, integrate observational data, and test these mechanisms across diverse settings to strengthen generalizability. Overall, closing the intention–enactment gap requires more than developing individual skills. It demands deliberately structured, feedback-rich, and collaborative environments that empower pre-service teachers to enact their aspirations in authentic classroom contexts. Recognizing peer/learning communities as a powerful lever for alignment while addressing the nuanced role of individual competencies like communication offers theoretical insight and practical guidance for enhancing STEM teacher preparation and improving instructional quality.

Educational implications and recommendations

The findings of this study have several important implications for teacher education programs, school partnerships, and policymakers seeking to strengthen STEM education. A central implication is the critical role of collaborative structures, particularly peer and learning communities, in supporting pre-service teachers to bridge the gap between intention and practice. When pre-service teachers engage in sustained, structured communities of practice, they gain access to peer feedback, shared modeling of effective strategies, and safe spaces to rehearse and refine instructional approaches. These collaborative experiences reduce the cognitive and emotional burdens of enacting complex instructional routines during practicum, increasing the likelihood that planned practices are implemented successfully. Teacher education programs should therefore prioritize the systematic integration of learning communities into their curricula, embedding cycles of observation, rehearsal, and reflection throughout the preparation process.

Another implication relates to demographic differences, especially the larger gaps among younger pre-service teachers. These findings suggest that teacher education programs could provide early and scaffolded practicum experiences that gradually build younger teachers’ confidence and enactment capacity. Mentorship models that pair novices with experienced educators can play a crucial role in fostering the skills and dispositions necessary for effective classroom practice. Without such targeted support, younger teachers may become discouraged when their aspirations consistently outpace their ability to implement desired practices.

The unexpected positive association between communication skills and larger gaps also has important programmatic implications. While communication remains a vital teaching competency, the findings caution against treating it as a stand-alone indicator of readiness for practice. Teacher education programs should ensure that communication skills training is closely integrated with hands-on, inquiry-based classroom activities. This integration will help pre-service teachers articulate ambitious goals and enact them effectively in real-world classroom settings.

From a policy perspective, these findings highlight the need for strong partnerships between universities and schools to ensure consistent, high-quality practicum experiences. Policymakers and institutional leaders should work to create resource-rich environments that enable collaborative mentoring and support the availability of materials needed for inquiry-based practical work, especially in resource-constrained contexts. Even well-prepared pre-service teachers will struggle to implement their intentions without adequate structural support.

These recommendations emphasize a shift from focusing solely on individual competencies to designing ecosystems that enable and sustain practice. By fostering collaborative learning environments, aligning communication training with practical enactment, and ensuring equitable access to resources and mentorship, teacher education programs and their partners can create conditions where pre-service teachers are empowered to translate their aspirations into meaningful classroom action. In doing so, they can help close the intention–enactment gap, improve instructional quality, and ultimately enhance student learning outcomes in STEM education.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Department of Teacher Education, University of Zimbabwe, under standard institutional procedures for practicum-based research involving pre-service teachers. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MT: Resources, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Visualization, Formal analysis, Software, Resources, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. FE: Supervision, Data curation, Validation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Visualization, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Grammarly were used solely to improve the language and readability of this manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for the content and its accuracy.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdurrahman, A., Nurulsari, N., Maulina, H., and Ariyani, F. (2019). Design and validation of inquiry-based STEM learning strategy as a powerful alternative solution to facilitate gifted students facing 21st century challenges. J. Educ. Gift. Young Sci. 7, 33–56. doi: 10.17478/jegys.513308

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2006). Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Amherst, MA, United States: University of Massachusetts Amherst. Available online at: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf

Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 26, 1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995,

Akuma, F. V., and Callaghan, R. (2019). Teaching practices linked to the implementation of inquiry-based practical work in certain science classrooms. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 56, 64–90. doi: 10.1002/tea.21469

Armitage, C. J., and Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939,

Bardach, L., and Klassen, R. M. (2021). Teacher motivation and student outcomes: searching for the signal. Educ. Psychol. 56, 283–297. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1991799

Becker, K., and Park, K. (2011). Effects of integrative approaches among science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects on students’ learning: A preliminary meta-analysis. Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, 12, 23–37. Available online at: https://www.jstem.org/jstem/index.php/JSTEM/article/view/1501

Berisha, F., and Vula, E. (2021). Developing pre-service teachers’ conceptualisation of STEM and STEM pedagogical practices. Front. Educ. 6:585075. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.585075

Breiner, J. M., Harkness, S. S., Johnson, C. C., and Koehler, C. M. (2012). What is STEM? A discussion about conceptions of STEM in education and partnerships. Sch. Sci. Math. 112, 3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-8594.2011.00109.x

Carroll, J. B. (1963). A model of school learning. Teach. Coll. Rec. 64, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/016146816306400801

Chen, S., Phillips, B. M., and Dong, S. (2024). Unpacking the language teaching belief–practice alignment among preschool teachers serving children from low-SES backgrounds. Teach. Teach. Educ. 140:104465. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104465

Connolly, C., Logue, P. A., and Calderon, A. (2023). Teaching about curriculum and assessment through inquiry and problem-based learning methodologies: an initial teacher education cross-institutional study. Irish Educ. Stud. 42:3, 443–460. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2021.2019083

Demir, E. K. (2021). The role of social capital for teacher professional learning and student achievement: a systematic literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 33:100391. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100391

Eagly, A. H., and Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-97700-000

English, L. D. (2016). STEM education K–12: perspectives on integration. Int. J. STEM Educ. 3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40594-016-0036-1

Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., and Power, K. (2023). Exploring pre-service teachers’ professional vision: modes of isolation, ethical noticing, and anticipation in research communities of practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 132:104245. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104245

Fitzgerald, M., Danaia, L., and McKinnon, D. H. (2019). Barriers inhibiting inquiry-based science teaching and potential solutions: perceptions of positively inclined early adopters. Res. Sci. Educ. 49, 543–566. doi: 10.1007/s11165-017-9623-5

Furtak, E. M., Seidel, T., Iverson, H., and Briggs, D. C. (2012). Experimental and quasi-experimental studies of inquiry-based science teaching: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 82, 300–329. doi: 10.3102/0034654312457

Gerhard, K., Jäger-Biela, D. J., and König, J. (2023). Opportunities to learn, technological pedagogical knowledge, and personal factors of pre-service teachers: understanding the link between teacher education program characteristics and student teacher learning outcomes in times of digitalisation. Z. Erziehungswiss. 26, 653–676. doi: 10.1007/s11618-023-01162-y

Gillies, R. M. (2023). “Teaching science that is inquiry-based: practices and principles” in Challenges in science education. eds. G. P. Thomas and H. J. Boon (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 39–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-18092-7_3

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., and McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15, 273–289. doi: 10.1080/13540600902875340

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., and Bransford, J. (2005). “How teachers learn and develop” in Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. eds. L. Darling-Hammond and J. Bransford (San Francisco, CA, United States: Jossey-Bass), 358–389.

Honey, M., Pearson, G., and Schweingruber, H. (Eds.). (2014). STEM integration in K–12 education: Status, prospects, and an agenda for research. National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18612

Huang, M., and Kaplan, D. (2024). Predictive performance of Bayesian stacking in multi-level education data. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 50, 214–238. doi: 10.3102/10769986241255969

Hunter, S. B., and Springer, M. G. (2022). Critical feedback characteristics, teacher human capital, and early-career teacher performance: a mixed-methods analysis. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 44, 380–403. doi: 10.3102/01623737211062913

Kaggwa, R. J., Blevins, A., Wester, E., Arango-Caro, S., Woodford-Thomas, T., and Callis-Duehl, K. (2023). STEM outreach to under-resourced schools: a model for inclusive student engagement. J. Stem Outreach 6, 1–16. doi: 10.15695/jstem/v6i1.04,

Kang, J. (2022). Interrelationship between inquiry-based learning and instructional quality in predicting science literacy. Res. Sci. Educ. 52, 339–355. doi: 10.1007/s11165-020-09946-6

Kang, H., and Windschitl, M. (2018). How does practice-based teacher preparation influence novices’ first-year instruction? Teach. Coll. Rec. 120, 1–44. doi: 10.1177/016146811812000803

Kelley, T. R., and Knowles, J. G. (2016). A conceptual framework for integrated STEM education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 3:11. doi: 10.1186/s40594-016-0046-z

Keskin, Ö., Seidel, T., Stürmer, K., and Gegenfurtner, A. (2024). Eye-tracking research on teacher professional vision: a meta-analytic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 42:100586. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100586

Kim, M., Tan, A. L., and Talaue, F. T. (2013). New vision and challenges in inquiry-based curriculum change in Singapore. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 35, 289–311. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2011.636844

Krajcik, J. S., and Shin, N. (2022). “Project-based learning” in The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. ed. R. K. Sawyer (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press), 72–92. doi: 10.1017/9781108888295.006

Kurz, A., and Elliott, S. N. (2011). “Overcoming barriers to access for students with disabilities: testing accommodations and beyond” in Assessing students in the margins: Challenges, strategies, and techniques. ed. M. Russell (Charlotte, NC, United States: Information Age Publishing), 31–58.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Leonor, J. P. (2015). Exploration of conceptual understanding and science process skills: a basis for differentiated science inquiry curriculum model. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 5, 255–259. doi: 10.7763/IJIET.2015.V5.512

Malaguti, A., Ciocanel, O., Sani, F., Dillon, J. F., Eriksen, A., and Power, K. (2020). Effectiveness of the use of implementation intentions on reduction of substance use: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 214:108120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108120,

Mumba, F., Banda, A., and Chabalengula, V. (2015). Chemistry teachers’ perceived benefits and challenges of inquiry-based instruction in inclusive chemistry classrooms. Sci. Educ. Int. 26, 180–194.

Mutseekwa, C., Dzavo, J., Musaniwa, O., and Nshizirungu, G. (2024). Framing pre-service teacher preparation in Africa from global STEM education practices. Pedagog. Res. 9:em0215. doi: 10.29333/pr/14701

National Research Council (2019). Science and engineering for grades 6–12: Investigation and design at the center. Washington, DC, United States: National Academies Press.

Nemadziva, B., Sexton, S., and Cole, C. (2023). Science communication: the link to enable enquiry-based learning in under-resourced schools. S. Afr. J. Sci. 119, 1–9. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2023/12819,

Opfer, V. D., and Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 376–407. doi: 10.3102/0034654311413609

Photo, P. (2025). Teaching experiences connected to the implementation of inquiry-based practical work in primary science classrooms. Res. Sci. Educ. 55, 1493–1516. doi: 10.1007/s11165-025-10235-3,

Ramnarain, U. (2016). Understanding the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on inquiry-based science education at township schools in South Africa. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 53, 598–619. doi: 10.1002/tea.21315

Schmidt, W. H., McKnight, C. C., and Raizen, S. A. (1997). A splintered vision: An investigation of U.S. science and mathematics education. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Schuster, J., Hartmann, U., and Kolleck, N. (2021). Teacher collaboration networks as a function of type of collaboration and schools’ structural environment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 103:103372. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103372

Shernoff, D. J., Sinha, S., Bressler, D. M., and Ginsburg, L. (2017). Assessing teacher education and professional development needs for the implementation of integrated approaches to STEM education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 4:13. doi: 10.1186/s40594-017-0068-1,

Sims, S., and Fletcher-Wood, H. (2021). Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: a critical review. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 32, 47–63. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2020.1772841

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., and Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.869710

Stohlmann, M., Moore, T. J., and Roehrig, G. H. (2012). Considerations for teaching integrated STEM education. J. Pre-Coll. Eng. Educ. Res. 2:4. doi: 10.5703/1288284314653

Strat, T. T. S., Henriksen, E. K., and Jegstad, K. M. (2023). Inquiry-based science education in science teacher education: a systematic review. Stud. Sci. Educ. 60, 191–249. doi: 10.1080/03057267.2023.2207148,

Sumida, S., and Kawata, K. (2021). An analysis of the learning performance gap between urban and rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 41:1779. doi: 10.15700/saje.v41n2a1779

Tatto, M. T., Schwille, J., Senk, S. L., Ingvarson, L., Peck, R., and Rowley, G. (2012). Teacher education and development study in mathematics (TEDS-M): Policy, practice, and readiness to teach primary and secondary mathematics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

Twizeyimana, E., Shyiramunda, T., Dufitumukiza, B., and Niyitegeka, G. (2024). Teaching and learning science as inquiry: an outlook of teachers in science education. SN Soc. Sci. 4:40. doi: 10.1007/s43545-024-00846-4

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA, United States: Harvard University Press.

Keywords: Bayesian analysis, inquiry-based practical work, intention–enactment gap, pre-service teachers, professional learning communities, stem education

Citation: Tsakeni M, Mosia M, Egara FO and Nwafor SC (2026) Bridging the gap between intention and enactment: a Bayesian analysis of pre-service teachers’ implementation of inquiry-based practical work in STEM (science-led) classrooms. Front. Educ. 10:1719693. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1719693

Edited by:

Konstantinos T. Kotsis, University of Ioannina, GreeceReviewed by:

Anastasios Zoupidis, Democritus University of Thrace, GreeceCharilaos Tsichouridis, University of Patras, Greece

Copyright © 2026 Tsakeni, Mosia, Egara and Nwafor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felix O. Egara, ZmVsaXguZWdhcmFAdW5uLmVkdS5uZw==

Maria Tsakeni

Maria Tsakeni Moeketsi Mosia

Moeketsi Mosia Felix O. Egara

Felix O. Egara Stephen C. Nwafor

Stephen C. Nwafor