- Department of Physics, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Bogotá, Colombia

Research on emotions in science education has gained increasing relevance in recent years, as it is now recognized that participants in the educational process, regularly experience emotions in the classroom, which in turn impact both teaching and learning. Teachers are responsible not only for promoting students’ academic achievement but also for promoting their holistic personal development. Consequently, addressing the affective dimension from the outset of science teacher education is essential in order to cultivate professional competencies that support emotionally informed teaching practices. This mixed-methods study involved 125 students from the Faculty of Science and Technology at the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Colombia. It examined emotions experienced in two different teaching situations: experimental or practical activities and lecture-based explanations. Findings indicate that emotional activation and self-efficacy in these situations are dynamic processes mediated by context, prior experience, perceived control, and the value attributed to the task. Understanding these affective experiences highlights the importance of strengthening initial science teacher education to equip future science teachers with the tools needed to address the emotional demands of teaching practice.

Introduction

Science teachers’ education must extend beyond mastery of conceptual and methodological content. Emotional experience, beliefs about one’s capacity to teach, and performance related goals are crucial for shaping teaching identity from the earliest stages of education (Brígido et al., 2013; Chang, 2009; Frenzel, 2014; Pekrun, 2006; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003). This study focuses on three interrelated constructs: self-efficacy, emotional activation, and teaching situations, framed theoretically through Russell’s Circumplex Model (Russell, 1980; Russell, 2003), Pekrun’s 2×2 framework (Pekrun, 2006), and Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). These models conceptualize emotional experience as an organized structure that interacts with personal beliefs and goals (Russell, 1980; Pekrun, 2006; Frenzel, 2014). Incorporating these models into the study of initial teacher education contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting teaching performance and provides clear guidance for designing educational interventions that promote emotional competence, professional confidence, and motivation to teach science (Serrano-Rodríguez and Pontes-Pedrajas, 2016; Costillo Borrego et al., 2013; Bravo Lucas et al., 2022).

Teacher self-efficacy defined as the belief in one’s capacity to influence student learning (Bandura, 1997), is a key factor that shapes the emotional experience in teaching. High self-efficacy is associated with the tendency to perceiving classroom challenges as manageable, experiencing positive emotions, and persisting in teaching tasks (Brígido et al., 2013; Borrachero et al., 2013; Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). Low self-efficacy, in contrast, is often associated with anxiety, frustration, and avoidance, particularly in pre-service teachers who experience emotionally demanding instructional situations (DeMauro and Jennings, 2016). Theoretical models by Russell and Pekrun frame emotions as responses to cognitive appraisals of control and value (Pekrun, 2006; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003), both of which are influenced by self-efficacy beliefs. Burić et al. (2020) show reciprocal relationships between self-efficacy and emotions experienced in teaching practice. These findings are supported by research that connects self-efficacy with emotional regulation, engagement, and resilience (Chang, 2009; Keller et al., 2014).

Emotional activation or arousal, distinguishes between physiologically activating states, associated with high energy levels, and deactivating states, associated with low energy levels. Activating states include excitement, enjoyment, hope, pride, anger, anxiety, revenge, and frustration. Deactivating states include relaxation, relief, calmness, hopelessness, sadness, boredom, and exhaustion (Pekrun and Perry, 2014; Shuman and Scherer, 2014). It is important to note that these states involve heightened physiological arousal, which can be measured at various levels, including neuronal activation and activation of large-scale autonomic and motor systems, engaging the body as a whole. Implicit motives closely related to these states are linked to hormonal changes, immune system functioning, and the activation of brain areas involved in motivation, such as the amygdala and the striatum (Pekrun and Perry, 2014; Schultheiss and Köllner, 2014; Shuman and Scherer, 2014).

Within the framework of initial teacher education, this study examines emotional activation and teacher self-efficacy in two pedagogical contexts: experimental or practical activities and lecture-based explanations. Although these situations can be approached as methodological strategies, they are understood here as pedagogical scenarios that generate different types of cognitive and affective demands that generate different emotions in future teachers.

Lecture-based explanation refers to a structured verbal presentation of content, in which information is structured and delivered to students. Traditionally associated with transmissive approaches, this strategy aims to organize, synthesize, and communicate knowledge, particularly when addressing abstract concepts or introducing a new topic (Camilloni et al., 1998; Martínez, 2006). However, its effectiveness depends on maintaining students’ engagement and attention. Porlán (1998) state that explanation loses its formative value when it becomes a monologue excluding active participation; therefore, it should be complemented with questions, examples, and visual aids. Zabala and Arnau (2007) emphasize that, an explanation used critically, can promote metacognitive processes if it is integrated into a didactic sequence that supports knowledge construction.

Experimental or practical activities are teaching situations in which students manipulate, observe, or explore physical or natural phenomena for educational purposes. In science education, these activities not only allow the application of procedures but also promote discovery learning, inquiry, and the development of scientific thinking (Hodson, 1993; Wellington, 1998). Millar (2004) argues that their value lies in creating meaningful connections between theory and experience, enabling students to compare their ideas with observed results. Furthermore, Acevedo-Díaz et al. (2017) suggests that well-designed practical work promotes the construction of meaning, generates cognitive conflict, and develops skills such as hypothesis formulation, variable control, and data interpretation. These characteristics make practical activities highly effective in eliciting emotions and perceptions of self-efficacy, as they offer tangible evidence of learning.

Theoretical framework

An approximation to the concept of emotion

Emotions are understood as brief, situation-dependent episodes that integrate physiological, cognitive, motivational, and expressive components (Shuman and Scherer, 2014). From a theoretical perspective, emotions have been conceptualized through basic and categorical approaches (Izard, 2007; Plutchik, 2001), as well as through multicomponential and appraisal-based models that emphasize dynamic interactions between cognitive, physiological, and contextual components (Scherer, 1984, 1997, 2000, 2001a, 2001b, 2009). They arise from individuals’ subjective appraisals of events and their relevance to personal goals or needs, which explains why the same situation can elicit different emotions across individuals. This conception integrates evolutionary, cultural, and cognitive perspectives (Tooby and Cosmides, 1990; Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Scherer, 2005) and is particularly relevant for this study, as it frames emotions as dynamic, multidimensional phenomena requiring interdisciplinary analysis. Emotions are understood as brief, situation-dependent episodes that integrate physiological, cognitive, motivational, and expressive components (Shuman and Scherer, 2014).

Emotional experience

A central aim of emotion research is to describe and organize affective phenomena systematically. The literature identifies two fundamental characteristics of emotional states: valence and activation, that provide the basis for such description and classification (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). Valence refers to the pleasantness or unpleasantness of an emotional state. Positive valence encompasses emotions such as enjoyment, happiness, whereas negative valence is associated with tension-filled states, such as anger, anxiety, boredom, hopelessness, or sadness. These two poles are thus designated as positive valence and negative valence, respectively (Shuman and Scherer, 2014).

Emotional activation (arousal) is closely related to action and effort. Some theoretical models suggest that when individuals perceive slow or insufficient progress toward a goal, affective responses may increase activation, prompting greater action and effort. For example, if progress is slow, the affective response may trigger an increase in actions and effort to achieve the goal (activating states). Conversely, when progress exceeds expectations, there may be a reduction in actions and effort, reflecting a tendency to avoid expending unnecessary energy (deactivating states). Discussion of the energetic levels of activation or deactivation in emotions introduces the field of objective measurement of emotional experience. According to the literature, emotional arousal can be objectively assessed by analyzing facial muscle activity through electromyography, which allows for associations between facial expressions and positive or negative affective responses (Schultheiss and Köllner, 2014).

The classification of emotions according to their valence (positive–negative) and activation (high–low) is grounded in the descriptive criteria of Russell’s Circumplex Model and does not imply any normative judgment regarding their pedagogical value. Consistent with contemporary perspectives in educational psychology (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014; Immordino-Yang, 2016), this study acknowledges that all emotions serve adaptive functions in teaching: negative emotions can stimulate reflection, pedagogical adjustment, and cognitive monitoring, while positive emotions can foster motivation, engagement, and the development of teacher–student relationships. Accordingly, the analysis of valence and activation is used as a heuristic for mapping affective states rather than as a prescriptive framework suggesting that certain emotions should be encouraged or suppressed.

Distinguishing emotions by valence and activation allows a more systematic grouping, beyond simple naming or similarity-based categories toward the use of basic axes or criteria for their description, organization, and comparison, giving them measurable, quantifiable properties (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). From a psychological perspective, valence and activation are orthogonal dimensions (statistically independent from one another). Valence reflects the pleasant-unpleasant emotions whereas activation captures the energizing-deactivating dimension (Shuman and Scherer, 2014). Therefore, Orthogonality implies that each dimension is statistically and mathematically independent from the other: valence indicates how positive or negative an emotion is, while activation denotes how energizing or deactivating it is.

Any emotional state can thus be described as a combination of pleasantness and energy demand. For example, sadness is negative and low in activation, while anger is negative but high in activation; both are unpleasant, but their bodily and behavioral effects differ. In general, this bidimensional framework (valence × activation) defines an affective space in which emotional experiences can be positioned according to their pleasantness and intensity, recognizing that these dimensions are related but vary independently (Russell, 1980; Feldman-Barrett and Russell, 1998).

The approach has a long-standing tradition in psychology, with Wundt (1897) proposing that emotions should not be understood merely as fixed categories, such as joy, anger, or fear, but rather as affective experiences describable along three dimensions: (1) valence, (2) activation, and (3) tension–relaxation dimension. Schlosberg (1954), refined Wundt’s ideas, by mapping emotions in a bidimensional space capable of representing the emotional experience in a circular (circumplex) structure based on facial expressions. This work provided the foundation for James Russell’s Circumplex Model in 1980.

Russell’s Circumplex Model (Russell, 1980; Russell, 2003) conceptualizes emotions as bidimensional phenomena defined by their valence (pleasant–unpleasant) and activation (high–low) in a continuous circular structure rather than as fixed categories (Russell and Barrett, 1998; Lang et al., 1998; Scherer, 2005). For instance, enthusiasm occupies the positive–high activation quadrant, whereas hopelessness lies in the negative–low activation quadrant (Goetz et al., 2006; Pekrun et al., 2002). This structure facilitates empirical study through affective mapping and provides a conceptual framework for linking emotional states to pedagogical practices (Sutton, 2004; Frenzel, 2014). In educational contexts, positive high activation states such as enthusiasm, curiosity, or joy are associated with greater teacher engagement, while negative high activation states such as stress, anxiety, or boredom can negatively impact classroom management and relationships (Meyer and Turner, 2002; Burić et al., 2020).

Within the circumplex model affective states are grouped according to their valence (positive vs. negative) and activation (activating vs. deactivating). This model, proposed by Feldman-Barrett and Russell (1998), also identifies and defines measurement tools such as the Self-Assessment Manikin (Bradley and Lang, 1994) which allow for empirical assessment of where emotions fall within this affective space. Constructivist perspectives interpret valence and activation as core components of affective life, shaped by both individual dispositions and environmental stimuli (Feldman-Barrett and Russell, 1998; Shuman and Scherer, 2014).

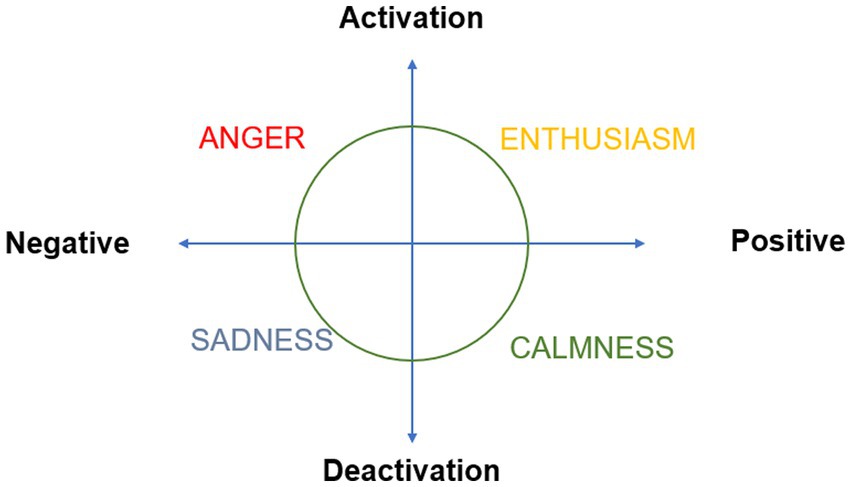

Specifically, Russell’s (1980) model places valence along the horizontal axis (negative on the left, positive on the right) and activation along the vertical axis (low activation at the bottom, high activation at the top). Emotions are located according to their specific combination of pleasantness and energy: anger is high activation with negative valence; sadness is low activation with negative valence; enthusiasm is high activation with positive valence; and calm is low activation with positive valence. This arrangement produces a circumplex, in which similar emotions cluster near one another and opposing emotions occupy opposite poles as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of Russell’s model proposal (Russell, 1980). Source: Authors' elaboration based on Russell's model.

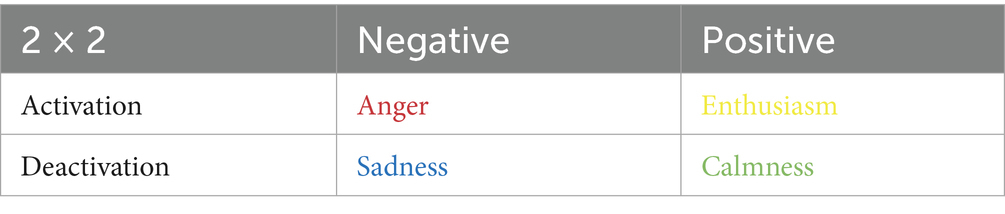

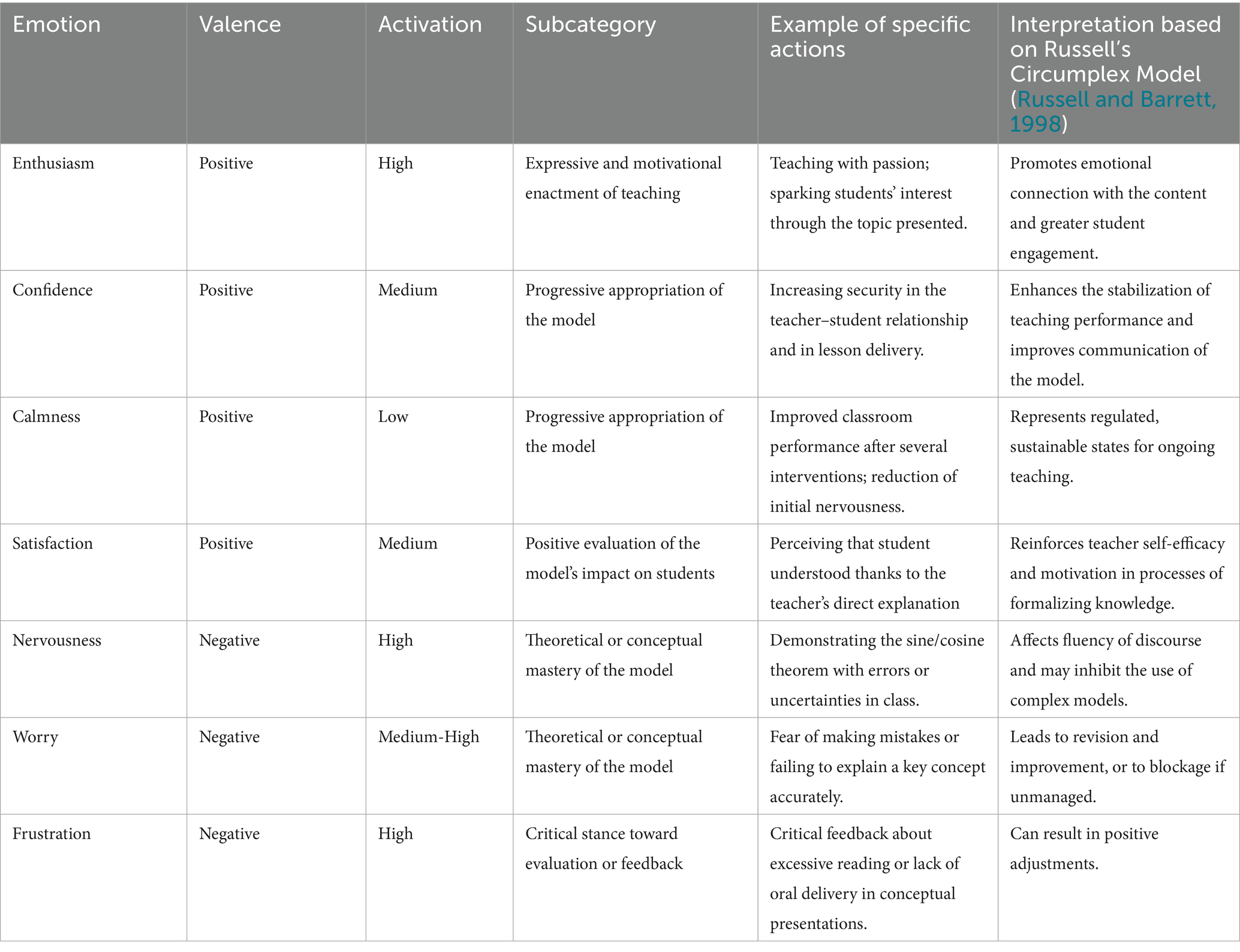

The circumplex approach, Pekrun’s (2006) 2 × 2 matrix transfers the bidimensional logic of affect into the educational domain, particularly in contexts involving performance assessment and achievement situations. This model classifies academic emotions into four categories according to their valence (positive or negative) and activation (high or low): positive activating (e.g., hope, pride), positive deactivating (e.g., relief), negative activating (e.g., anxiety, anger), and negative deactivating (e.g., boredom, hopelessness) (Pekrun et al., 2002; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). Unlike the circumplex model, the 2 × 2 framework focuses on motivational and cognitive effects of emotions on teaching and learning processes. High-activation positive emotions tend to promote engagement, intrinsic motivation, and deep learning strategies, whereas negative emotions, particularly those of low activation, are associated with reduced concentration, persistence, and academic performance (Pekrun, 2006; Goetz et al., 2007; Frenzel et al., 2016). In teacher education, this model helps identify emotional profiles linked to adaptive or maladaptive pedagogical practices (Allaire et al., 2023; Gramipour et al., 2019). A strength of this dimensional approach lies in its capacity to organize emotions within a 2 × 2 structure, widely used in emotion psychology for its clarity and functionally simplicity to show the interaction between valence and activation dimensions (Russell, 1980; Feldman-Barrett and Russell, 1998; Pekrun and Perry, 2014). This structure arranges emotions into four quadrants according to valence and activation, facilitating the interpretation of their effects on behavior, learning, or well-being. Moreover, it combines the dimensions effectively, grounded in two orthogonal independent central axes, thus providing both empirical and theoretical support, as validated by Russell (1980), Feldman-Barrett and Russell (1998), and Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014). The integration of this classification into educational research provides insight into the role of emotions in students’ academic achievement. An example of this framework is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Example of Russell’s (Russell and Barrett, 1998) 2 × 2 model.

The dimensional perspective on emotions has gained significant prominence within the psychological study of individuals’ affective states, being applied in multiple fields and contributing to the development and structuring of various models and theories aimed at understanding the role of emotions in everyday activities. Within this framework, Pekrun’s control–value theory (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014) explains the generation of academic through students’ subjective evaluations of two factors: the perceived control over a task or outcome and the value assigned to it. These evaluations generate emotions that can be located within the circumplex space, for example, high perceived control combined with high value tends to reflect enthusiasm (positive, high activation), whereas low perceived control and low value may lead to boredom or hopelessness (negative, low activation). Thus, Pekrun’s (2006) theoretical proposal complements the circumplex model by adding a cognitive mechanism for the emergence of emotions, offering a more comprehensive perspective for understanding their role in learning processes and academic performance.

Emotions in science education and teacher preparation

Building on the psychological models previously described, it is important to situate emotional activation within the specific field of science education, where emotions have acquired a central role in understanding how preservice and in-service teachers interpret teaching situations, make pedagogical decisions, and construct their relationships with scientific knowledge and with their students. Research has shown that emotions influence not only the quality of teaching and learning processes but also motivation, teacher self-efficacy, and the capacity to cope with the inherent challenges of educational practice (Mellado Jiménez et al., 2014). Understanding emotions as sociocultural and pedagogical constructions thus enables the development of training approaches that recognize their complexity and their mediating role in teacher activity. Recent studies highlight the need to integrate the affective dimension into teacher education programs to strengthen didactic decision-making, emotional regulation, and engagement with school scientific practices (Romero et al., 2024). The emerging paradigm that positions emotions as a constitutive dimension of science teacher identity also calls for more reflective and humanized approaches to initial teacher preparation (Alméciga Castro, 2024).

Affective dimensions of inquiry and experimental practice

In the context of scientific inquiry and experimental activities, emotions function as structuring components that shape the execution of procedures, the interpretation of results, and the willingness to persist in the face of difficulties. A positive and well-regulated emotional climate supports higher-quality learning experiences and allows experimental practice to become a space of meaning and professional confidence (Bellocchi et al., 2014). Affectivity, understood as the emotional orientation accompanying inquiry, modulates cognitive and motivational engagement in school research processes. Inquiry-based and student-centered approaches have been shown to increase interest and achievement precisely because they elicit favorable affective responses that sustain curiosity, persistence, and intellectual effort (Kang and Keinonen, 2018). Classroom intervention studies also demonstrate that it is possible to strengthen both emotional and cognitive engagement among preservice teachers when scientific practices incorporate socioscientific issues and explicitly integrate affective–cognitive instructional strategies (López-Banet et al., 2024).

Emotion, scientific practice, and the development of teacher identity

The relationship between emotion, scientific practice, and teacher identity is reciprocal and mutually reinforcing. Emotional experiences during experimental tasks shape preservice teachers’ perceptions of their professional competence, while emerging identities influence how they interpret, regulate, and assign meaning to their affective experiences in school laboratories and classrooms (Smit et al., 2021). Research in laboratory and classroom contexts has documented substantial individual differences in emotional responses, which in turn predict variations in teacher self-efficacy; these findings underscore the importance of providing structured opportunities for emotionally meaningful practice to foster professional confidence (Smit et al., 2021; Bellocchi et al., 2014). Moreover, studies in instructional design and science teacher education reveal that active emotional engagement in inquiry environments not only promotes the acquisition of scientific competencies but also contributes to the construction of a reflective and resilient teacher identity capable of integrating affective and cognitive dimensions into informed didactic decisions (López-Banet et al., 2024; Kang and Keinonen, 2018).

Emotions of pre-service science teachers

As has been noted, recent literature has highlighted that teachers’ emotions constitute a central axis in understanding teaching and learning processes. Porter and Donaldson (2025) point out that although teachers’ emotions decisively influence their beliefs, shape their pedagogical and didactic interpretations, and motivate their actions in the classroom, this dimension has received limited attention in educational research, despite its profound impact on the decisions made daily in school contexts.

In the same vein, Dağtaş and Zaimoğlu (2025) emphasize that emotions play a fundamental role in the development and transformation of teachers’ professional identity, as they mediate how teachers recognize themselves in their role, relate to their practices, and envision their professional activity. This argument is reinforced by the work of Cheng (2021), who maintains that emotions not only accompany pedagogical practice but also act as shaping forces of teacher identity, influencing the construction of its meaning, the perception of self-efficacy, and the decisions that guide professional trajectories. From this perspective, emotions offer insight into how teachers manage tensions, challenges, and expectations as they continuously reconstruct their identity.

These insights align with studies on teachers’ emotional competence and its impact on students’ socio-emotional development. As demonstrated by Rauterkus et al. (2025), teachers’ ability to regulate their emotions fosters the development of positive relationships with students and, through these, facilitates processes of social integration within the classroom. Taken together, these contributions suggest that emotions form a structuring axis that permeates professional identity, pedagogical decision-making, and the quality of educational relationships, positioning the emotional dimension as a key element for understanding and strengthening teaching practice.

During pedagogical practice, pre-service teachers experience various emotions arising from their interactions in real-educational settings. These emotions are not merely instinctive or physiological impulses; rather, they are shaped by the sociocultural conditions, influenced by political, cultural, and power dynamics (Heng et al., 2024). Factors such as personal beliefs, performance expectations, lack of teaching experience, feedback from mentors, institutional climate, insufficient mastery of subject matter, all contribute to emotional states when teaching. Addressing these emotions is essential for maintaining teaching quality and safeguarding teachers’ psychological well-being (Frenzel et al., 2015).

Research indicates that pre-service science teachers often feel emotionally vulnerable reporting negative emotions when confronted with the everyday demands of classroom life (Borrachero et al., 2014). Such experiences highlight the need for developing emotional self-regulation skills to manage and transform emotions productively. Conversely, activities such as scientific demonstrations and reflective teaching exercises are frequently associated with positive emotions, as they align with pre-service teachers’ expectations and learning abilities in acquiring relevant knowledge (Bellocchi et al., 2014). Nevertheless, even these positive experiences can vary in intensity depending on context and individual differences.

Cultivating awareness of emotional responses allows pre-service science teachers to recognize situations and actions that affect affective processes in science teaching and learning. This awareness supports the capacity to self-regulate and adapt emotions in ways that enhance teaching effectiveness (Borrego et al., 2013). Therefore, initial teacher education programs should intentionally incorporate opportunities for identifying and reflecting on emotions, given their influence on teaching attitudes, self-regulate strategies, and the development of teaching self-efficacy (Borrachero Cortés, 2015).

Drawing on the theoretical framework presented—which articulates the role of emotions in science teaching, teacher self-efficacy, and the influence of instructional situations—the objectives of this study are defined as follows: (1) to identify the predominant emotions experienced by pre-service science teachers across different teaching situations; (2) to analyze how these emotions relate to their perceived self-efficacy, understood as their belief in their ability to plan, implement, and evaluate instruction; and (3) to examine how features of the institutional context—particularly lectures and practical activities—shape emotional activation. This theoretical foundation justifies the methodological design and underscores the relevance of exploring the affective dimension as a constitutive component of science teacher professional development.

In summary, activation refers to the level of physiological and psychological arousal associated with an emotion, whereas valence describes its perceived pleasantness or unpleasantness. Perceived control refers to the teacher’s appraisal of their ability to influence teaching outcomes, and self-efficacy refers to their belief in their capacity to plan, implement, and evaluate teaching activities.

Method

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach, defined as a referential framework distinct from positivist, interpretative, and critical paradigms, as it integrates the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods. This approach addresses research questions through paradigmatic perspectives that prioritize problem-solving over rigid adherence to philosophical positions (Greene, 2008; Morgan, 2007). Scholars including Bryman (2008) and Bredo (2009) have noted that this methodology mitigates paradigm tensions and facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of educational phenomena. Similarly, Creswell and Plano Clark (2011) identify methodological triangulation as a key element, enabling the strategic combination of multiple data sources to strengthen validity.

Within this framework, explanatory and exploratory designs, applied simultaneously or sequentially, make it possible to integrate surveys with interviews or focus groups with quantifiable measurements (Ucar et al., 2011; Adadan, 2020). This flexibility allows for the combined use of methods to deepen understanding of variables such as motivation (Adadan, 2020). In the present study, the qualitative and quantitative components were synergistically integrated, enabling data triangulation, which provided a more complete and nuanced understanding of the research object. The mixed-methods design enhanced both the robustness and generalizability of the results while maintaining the level of detail necessary to ensure the validity and replicability.

Quantitative data was collected through a structured questionnaire designed to measure specific constructs related to emotions experienced by pre-service teachers. Qualitative data was gathered through focus groups, enabling in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences and perceptions regarding the expression and regulation of emotions during pedagogical practice.

A convergent-triangulation mixed-methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011) was employed, in which quantitative and qualitative data was collected and analyzed in parallel and subsequently integrated during the interpretive phase. The quantitative component identified patterns in the frequency of emotions across teaching situations, while the qualitative component deepened the understanding of the subjective and contextual dimensions of those emotional experiences. The joint interpretation allowed for the examination of points of convergence (alignment between self-reported emotions and narrated experiences), divergence (emotions with high quantitative frequency but limited qualitative elaboration), and complementarity, strengthening the explanatory power of the findings. One example of convergence appeared in the case of anxiety: participants rated anxiety as one of the most frequent emotions in the questionnaire, and the focus group narratives revealed similar concerns about lack of content mastery and fear of negative evaluation. A divergence emerged with joy: while it showed moderate quantitative frequency, qualitative data revealed rich descriptions of joyful experiences during practical activities, suggesting that joy may be more context-dependent and less spontaneously self-reported. These patterns illustrate how mixed-methods integration allowed a more nuanced understanding of emotional activation.

Research objectives

Building in the theoretical framework—which integrates emotional activation, teacher self-efficacy, and the pedagogical characteristics of lecture-based explications and practical activities—this study addresses the following research objectives: 1. To identify the predominant emotions experienced by pre-service science teachers across different teaching situations. 2. To analyze how these emotions relate to their perceived self-efficacy, understood as their belief in their ability to plain, implement, and evaluate instruction. 3. To examine how specific features to the instructional context–particularly lectured-based explanations and practical/experimental activities–shape emotional activation.

These objectives guide the methodological design and ensure coherence between the theoretical foundations, analytical procedures, and conclusions of the study.

Instruments

Data collection instruments included a questionnaire and focus groups, both aimed at capturing the emotional experiences of pre-service teachers. The Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument (STEBI), developed by Riggs and Enochs (1990), was used to assess two key dimensions: personal efficacy for science teaching and outcome expectancy. Grounded in Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977, 1997), this instrument has proven to be a valid and reliable tool for evaluating teaching beliefs in initial educational contexts (Enochs and Riggs, 1990; Bleicher, 2004). The questionnaire assessed ten emotions: five of positive valence (joy, satisfaction, enthusiasm, calmness, and confidence) and five of negative valence (nervousness, worry, boredom, frustration, and rejection). This structure enabled the identification of both the activating nature and the emotional direction associated with each reported teaching experience. The instrument was complemented by an ad hoc emotional questionnaire designed to examine emotions activated in specific teaching situations.

The questionnaire used in this study was adapted from the STEBI, originally developed by Riggs and Enochs (1990), which is widely recognized for assessing self-efficacy beliefs in prospective science teachers. For this research, a linguistic and contextual adaptation was conducted following international guidelines for instrument adaptation in educational research, and its content validity was reviewed by two experts in emotional processes in science education. The internal consistency of the adapted instrument demonstrated adequate reliability: the Personal Science Teaching Efficacy (PSTE) factor yielded a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.8, and the Science Teaching Outcome Expectancy (STOE) factor exceeded 0.70. An exploratory factor analysis replicated the original two-factor structure, supporting the construct validity of the instrument in the Colombian context. This process ensures that the questionnaire used in the quantitative phase meets appropriate standards of content validity, construct validity, and reliability, enabling meaningful interpretation of the results within the theoretical frameworks of teacher self-efficacy and emotional activation (Enochs and Riggs, 1990; Bleicher, 2004). Quantitative data was collected through a Google Forms questionnaire and the information was processed using SPSS v.30. An initial descriptive and inferential statistical analysis of responses was conducted for each section of the questionnaire, followed by the analysis in relation to three different teaching situations.

For qualitative data collection, focus groups were conducted using a set of expert-validated questions. An interpretative approach guided the qualitative analysis, using discourse analysis to identify the ideas, perceptions, and experiences expressed by pre-service teachers in the Faculty of Science and Technology.

Qualitative data was transcribed and organized in Atlas.ti 25 according to a priori theoretical categories. Interpretation followed the three levels proposed by Peñalva-Vélez et al. (2013): (1) the textual level (fragmentation of the text and extraction of relevant quotations), (2) the conceptual level (construction of models by linking codes into semantic networks), and (3) the organizational level (establishing connections between textual and conceptual levels to enable comprehensive discourse analysis).

Participants

The study population comprised 125 students from the Faculty of Science and Technology, enrolled in undergraduate programs in Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Mathematics, Electronics, Technological Design, and Natural Sciences at the Faculty of Science and Technology, who were engaged in pedagogical practice or immersive educational experiences in diverse contexts (n = 125). The sample included students from various teacher education programs within the faculty, all with direct experience in teaching natural sciences and technology. These participants were therefore well suited to provide insights into the emotions elicited in specific teaching scenarios. They were enrolled between the fourth and tenth semesters and were completing their teaching practicum in public and private schools across the city. During this practicum, the pre-service teachers assisted in science courses and assumed responsibilities such as lesson planning, classroom instruction, conducting laboratory and hands-on activities, evaluating student learning, and participating in feedback sessions with both the school mentor teacher and the university advisor. The curriculum in science, mathematics, and technology included topics from mechanics, electricity, general chemistry, school biology, mathematical reasoning, technology education, and integrated science. This variety of disciplinary contexts enabled a comprehensive examination of emotional activation across different domains of science teaching.

Results

The results are presented for two selected teaching situations: lecture-based explanations, and experimental or practical activities. These situations were chosen for their pedagogical significance in science teacher education and their capacity to reveal distinct emotional and cognitive dynamics among preservice teachers. First, quantitative results obtained through the questionnaire were reported, followed by qualitative findings derived from the focus groups, which provided complementary insights into the emotional experiences of students enrolled in the faculty’s teacher education programs at the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional.

Teaching situation: lecture-based explanations in class

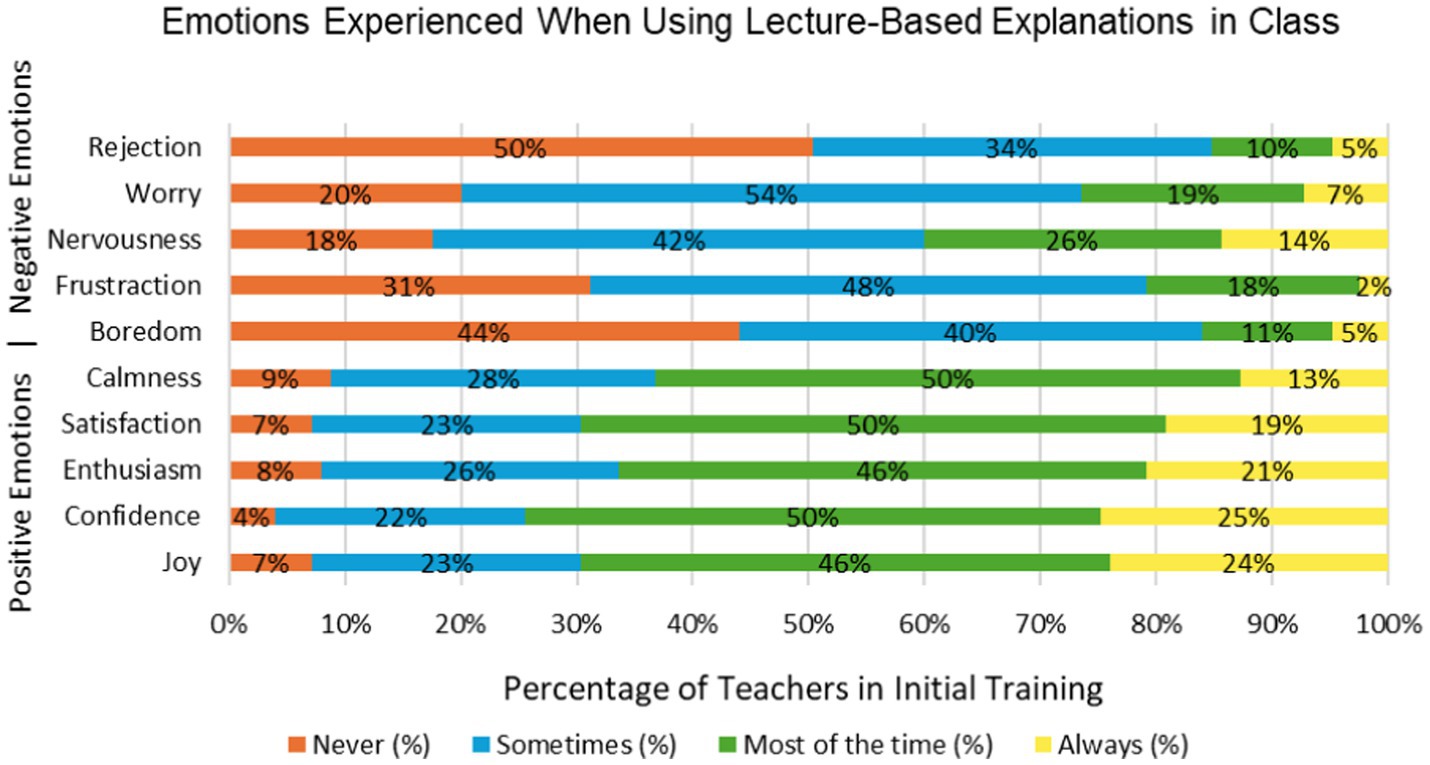

Findings indicate a predominance of positive over negative emotions, suggesting an overall favorable perception of lecture-based explanations, as shown in Figure 2. Confidence emerged as the most salient positive emotion, reported as experienced “most of the time” by 50% of participants and “always” by 25%, indicating that this teaching situation provides prospective teachers with a sense of security. Likewise, calmness was reported “most of the time” by 50% and “always” by 13% of participants; satisfaction by 50 and 19%, respectively; and joy by 46 and 24%.

Figure 2. Emotions experienced when using lecture-based explanations in class. Authors' elaboration—Excel 2019.

Negative emotions appeared most frequently in the “sometimes” category, with 34% reporting feelings of rejection, 54% worry, 42% nervousness, 48% frustration, and 40% boredom. These findings suggest that, although lecture-based explanations are generally valued positively, they can also elicit mixed or ambivalent emotional responses in certain contexts.

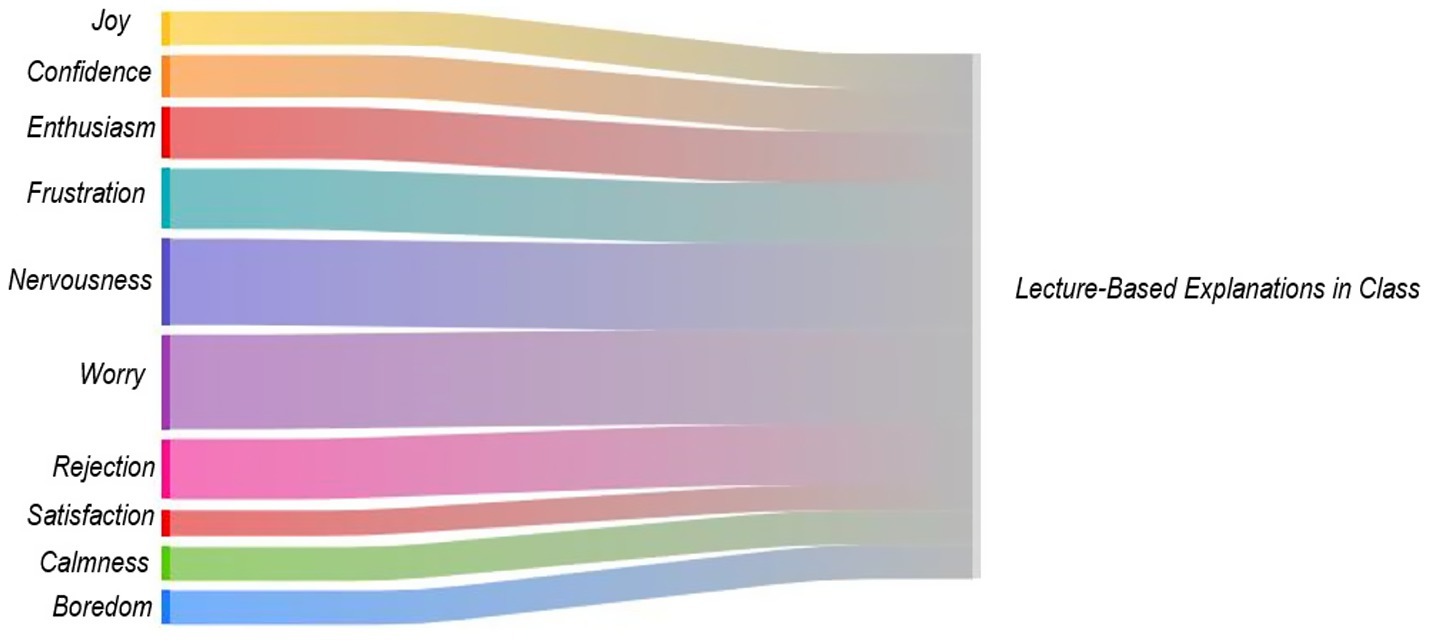

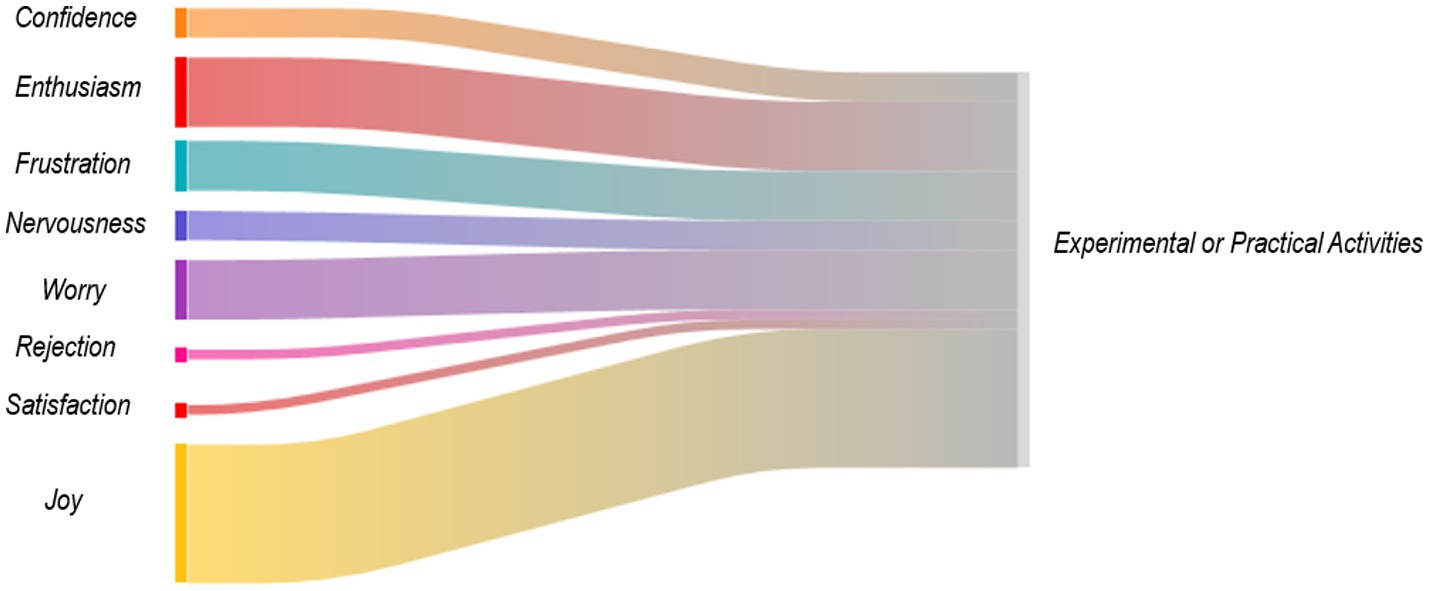

In this teaching situation, participants reported experiencing all ten (10) emotions identified in the study. As shown in Figure 3, the Sankey diagram visually represents how frequently each emotion is associated with lecture-based explanations: the width of each flow indicates the strength of the connection, allowing for a rapid identification of the most prominent emotional responses. At first observation, negative emotions occupy a substantial portion of the diagram, indicating that lecture-based explanations often evoke negative affect or represent a challenge for participants. Worry, nervousness, frustration, and rejection appear as the most prominent emotions by wider flows in the diagram. Worry is linked to concerns regarding the effectiveness of student learning, classroom time management, and the development of pedagogical competencies required to successfully implement lecture-based instruction. Nervousness is associated with limited mastery of content and difficulties in classroom management, particularly maintaining order and sustaining student attention, as well as the tensions generated by performance evaluations conducted by mentor teachers. Frustration emerges from limited student participation and the perception that teaching science through lectures does not promote deep learning or meaningful real-world connections.

In contrast, positive emotions such as enthusiasm, confidence, joy, and satisfaction are less prevalent, suggesting that this pedagogical approach is not a strong generator of positive emotions for prospective teachers and may even inhibit such emotions. Ambivalence is observed between calmness and boredom: while calmness may arise at specific moments during practice, boredom is often expressed in discourse as characterizing monotonous or unstimulating lectures.

The Sankey diagram shows how frequently each emotion in linked to this teaching situation. Wider flows represent stronger associations.

From the perspective of Russell’s Circumplex Model (Russell and Barrett, 1998), as shown in Table 2, lecture-based explanations show high activation levels for negative-valence emotions. This pattern is attributable to the demands placed on science teachers to convey disciplinary content effectively and to adapt language to suit specific classroom contexts and student populations. Inexperience in delivering lectures frequently triggers emotions such as worry, nervousness, and frustration. Lecture delivery requires communication skills, the ability to sustain attention, clear and logical structuring of content, and the capacity to anticipate students’ questions skills that when underdeveloped can lead teachers feeling ineffective. These emotions are further intensified when mentors or students evaluate the teacher unfavorably, particularly if the session fails to facilitate the construction of school-level scientific knowledge.

Table 2. Relationship between emotion, lecture-based explanations, and Russell’s circumplex model (Russell and Barrett, 1998).

Among all emotions, worry registers the highest activation, primarily due to apprehension over theoretical of conceptual mastery of the material presented. This worry is rooted in fears of making errors or misrepresenting concepts. Within Russell’s Circumplex Model (Russell and Barrett, 1998), worry can become a persistent barrier, keeping the individual in an “unpleasant” state and preventing progression toward calmness or pleasure. A participant discourse illustrates this concern:

“It was worry, because that class was my responsibility. I had to explain the sine and cosine theorem, and at one point I wanted to do a demonstration, but the diagram on the board—the right angles—was not very clear, which is essential for the demonstration to be valid. You feel the responsibility for what you are teaching, and I think that if they do not study it elsewhere, it depends entirely on me.”

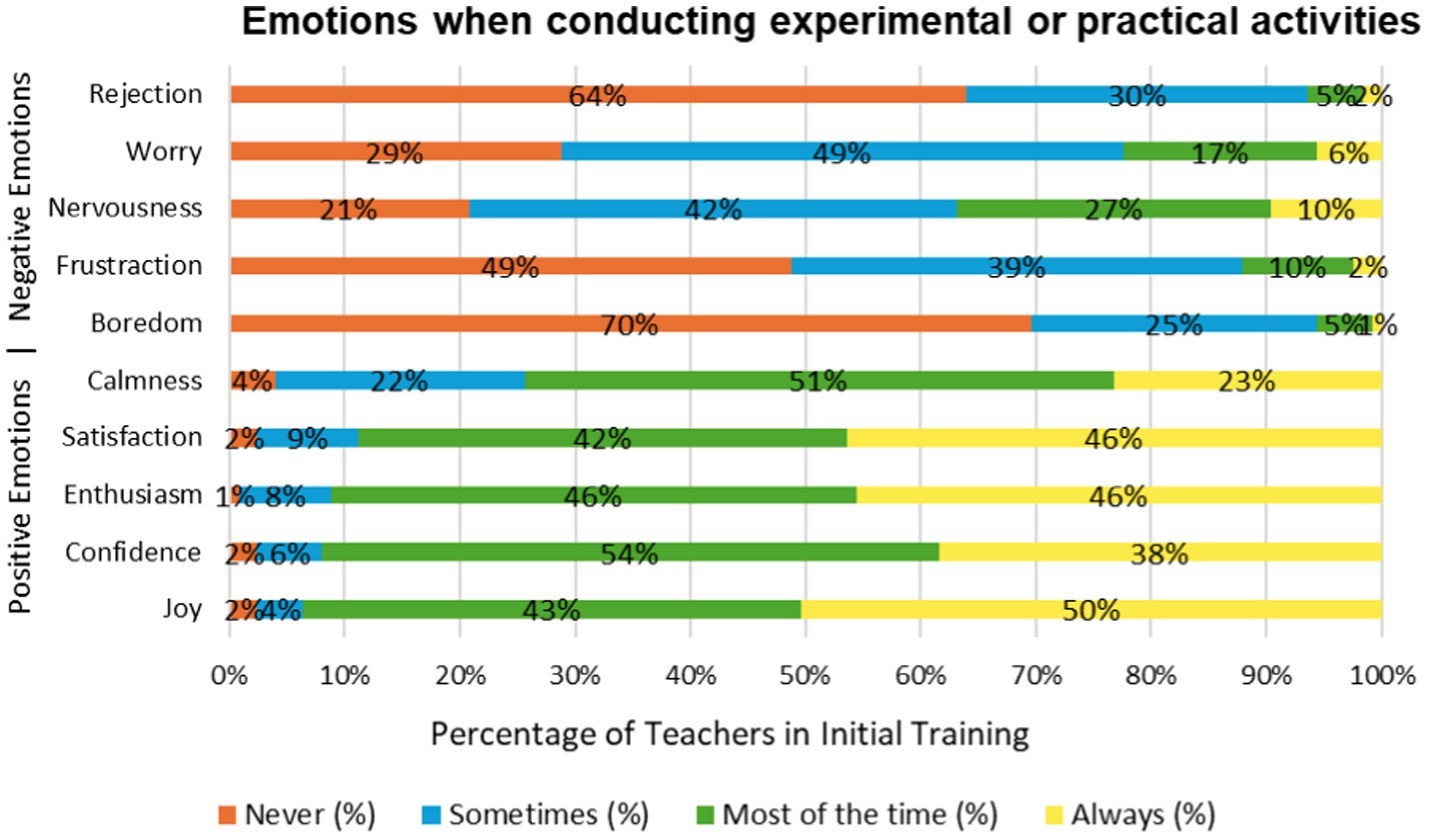

Teaching situation: experimental or practical activities

The implementation of experimental or practical activities in initial teacher education is predominantly associated with the activation of positive emotions among preservice teachers. As shown in Figure 4, joy emerged as the most frequently reported emotion with 50% of participants indicating that they experienced it “always” and 43%, “most of the time.” This pattern reflects the high level of gratification derived from engaging in experimental activities. Similarly, confidence was experienced “most of the time” by 54% and “always” by 38% of participants; enthusiasm was reported by 46% in both categories; satisfaction by 42 and 47%, respectively; and calmness by 51% “most of the time” and 23% “always.”

Figure 4. Emotions when conducting experimental or practical activities. Authors' elaboration—Excel 2019.

In contrast, negative emotions were largely concentrated in the “never” and “sometimes” categories. Boredom was reported as “never” by 70% of respondents, rejection by 64%, frustration by 49%, worry by 29%, and nervousness by 21%. In the “sometimes” category, the distribution was as follows: worry 49%, nervousness 42%, frustration 39%, rejection 30%, and boredom 25%. These findings suggest that experimental activities significantly reduce the occurrence of negative emotions while enhancing the prevalence of positive affect, an essential factor in strengthening motivation and professional confidence among pre-service teachers.

The Sankey diagram in Figure 5 illustrates the magnitude and distribution of emotions reported by participants. Consistent with the representation used in Figure 3, the diagram shows the relative prominence of each emotion by the width of its flow, indicating how strongly it was associated with practical or experimental activities. This visual structure facilitates rapid comparison across emotions and highlights the predominance of high-activation positive emotions in this teaching situation.

Figure 5. Emotional associations with practical or experimental activities. Authors´ elaboration—Atlas.ti.

Only eight of the ten emotions identified in the study appeared in participants’ discourse; tranquility and boredom were absent. Joy was the most prominent emotion, signifying high levels of well-being, motivation, and enjoyment. It also serves as an indicator of engagement and meaningful connection with learning processes. Laboratory experiments, direct observation of phenomena, fieldwork (e.g., the school garden), practical challenges, and science-based games requiring the application of theoretical knowledge were identified as particularly impactful teaching situations (Smit et al., 2021; López-Banet et al., 2024; Sánchez-Martín et al., 2018).

Similarly, enthusiasm and confidence exhibited relatively wide flows in the diagram, reflecting perceptions of self-efficacy, intellectual curiosity and an active solution-oriented attitude toward the demands of practical activities. These emotions were closely linked to participants belief in their capacity to successfully execute scientific tasks, appreciation of science as a tool for understanding the world, and willingness to address challenges with resilience.

Negative emotions, while less prevalent, were not absent. Frustration, worry, and nervousness were associated with uncertainty regarding the attainment of desired results, difficulties in executing experimental procedures accurately, and conceptual insecurity. Rejection appeared only marginally and linked to prior negative experiences, attitudinal resistance or gaps in procedural skills.

The Sankey diagram shows how frequently each emotion is linked to this teaching situation. Wider flows represent stronger associations.

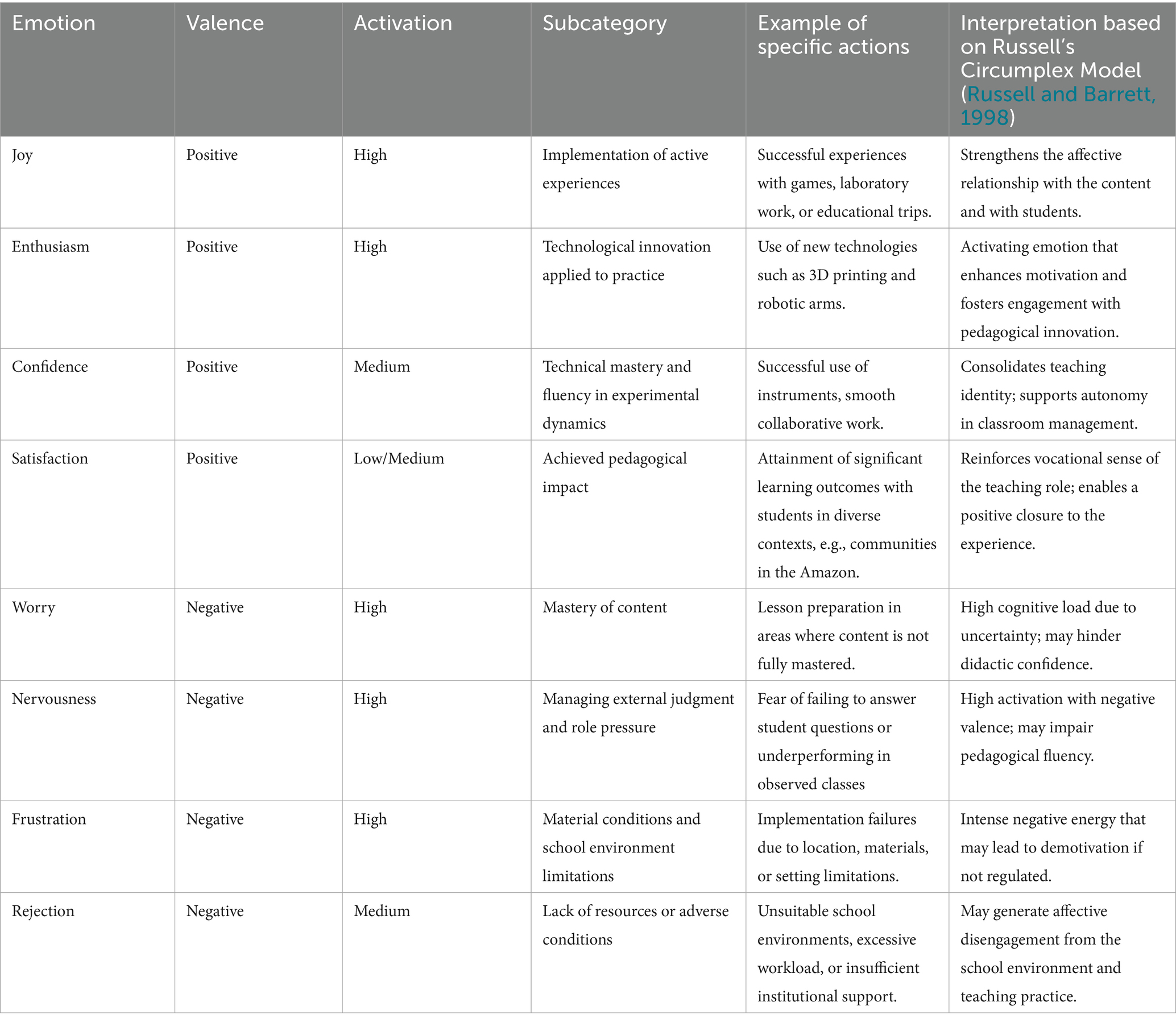

Table 3 summarizes the relationship between reported emotions and the Russell Circumplex model (Russell and Barrett, 1998) for this teaching situation. The most frequently mentioned subcategory in the participants’ discourse concerned the implementation of practical tasks or concrete actions. These results highlight the emotional complexity of formative experiences during initial pedagogical practice, revealing their influence not only on teaching performance but also on the construction of professional identity.

Table 3. Relation between entre emotion, practical or experimental activities and Russell circumplex model (Russell and Barrett, 1998).

Joy emerged as the most prevalent emotion, characterized by positive valence and high activation. Within this context, joy provides an optimal emotional environment, reinforcing coherence between the act of teaching and the relationships established with students. This emotion was mentioned in activities that required the use of didactic resources that were well received by learners. Games, laboratory work, and educational field trips were cited as experiences that contributed to a heightened sense of teaching effectiveness, reinforcing teachers’ vocational commitment and the perceived importance of implementing innovative strategies.

In Russell’s circumplex model (Russell and Barrett, 1998), joy is interpreted as a positive affective state that enhances the bond between teachers, subject matter, and students. This is exemplified in the following participant reflection.

“The lesson was on angiosperms, that is, flowering plants. It involved creating an interactive blog, a web page where students could move elements, click on them, and have new items appear something very dynamic. I worked on it throughout the semester, and when I finally met with them in the computer lab, they opened it, explored it, and completed the activities that were already there. At that moment, I felt very, very happy, it was incredible. They even told me that they really liked the evaluations I had included on the page.” (Reference 124 – Atlas.Ti).

These findings align with research showing that emotions emerge as epistemic forces during scientific inquiry and laboratory activity (Bellocchi et al., 2014). The heightened activation observed in practical situations resonates with studies demonstrating that hands-on engagement increases emotional intensity because it requires immediate decision-making, manipulation of materials, and coordination with students—conditions known to influence the development of scientific teaching identity (Smit et al., 2021).

Discussion of results

The mixed-methods design of this study allowed for the integration of quantitative and qualitative data, each guided by distinct methodological logics complementing one another to provide a richer, multidimensional understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The quantitative component based on a structured questionnaire, measured the frequency of ten pre-defined emotions experienced by pre-service teachers. The qualitative component, conducted through focus groups, enabled the contextualized elicitation of these emotions during real teaching situations experienced in the practicum. While no direct statistical correlation was established between the two datasets, methodological triangulation facilitated their joint interpretation providing complementary perspectives that enhanced the explanatory depth of the findings.

Teaching situation: lecturing in class

The affective impact of lecture-based instruction can be interpreted through the frameworks of Russell’s Circumplex Model (Russell, 1980), Pekrun’s Control-Value Theory (Pekrun, 2006), and Bandura’s self-efficacy Theory (Bandura, 1997), alongside multicomponential perspectives on emotion proposed by Scherer (2005) and Shuman and Scherer (2014). Quantitative results revealed reports of enthusiasm, confidence, and joy all positioned in the high activation, positive valence quadrant of the circumplex. Within Pekrun’s model these are categorized as positive activating emotions that promote engagement, commitment, and perseverance, often emerging when lectures are accompanied by prior positive experiences or supportive feedback. These emotions are also indicative of elevated self-efficacy, aligning with prior STEBI- based research (Riggs and Enochs, 1990; Bleicher, 2004).

Lower activation positive emotions, such as tranquility and satisfaction, occupy the positive deactivating quadrant, contributing to emotional stability without requiring high arousal, beneficial in routine or low stress situations. In contrast, high activation negative emotions such concern, nervousness, and frustration, occupy the negative-valence high-activation quadrant and are classified by Pekrun as activating negative emotions, emerging when a task is highly valued but perceived as difficult to control (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). These can heighten stress and diminish self-regulatory capacity, with repeated exposure impacting self-efficacy and performance (Pekrun and Perry, 2014; Scherer, 2005). According to Bandura (1997), repeated exposure to such emotions can undermine perceived self-efficacy, particularly in individuals still consolidating their professional identity.

Low-activation negative, namely rejection and boredom, fall within the negative deactivating quadrant and signal affective disengagement, often linked to low perceived task value also (Pekrun et al., 2002). Physiologically and behaviorally, such states entail reduced commitment and a predisposition toward withdrawal, which can diminish pedagogical involvement (Schultheiss and Köllner, 2014).

Overall, the data highlight the coexistence of emotions of varying valences and activation levels within the same teaching situation, reflecting the multicomponential and subjective nature of emotions, as emphasized by Scherer (2005) and Shuman and Scherer (2014). This diversity captures not only the individual judgments that each pre-service teacher makes about the situation but also contextual factors such as content mastery, student interaction, and institutional conditions. Consequently, the analysis extends beyond quantifying emotions to interpreting them as indicators of professional, emotional, and cognitive development in future science educators (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). This interpretation responds directly to Objective 1, as it characterizes the emotional patterns that emerge across the two instructional situations analyzed.

Considering the three teaching situations studied, lecturing emerges as a structuring practice within the initial training experience, not only due to its prevalence in school environments but also due to its substantial emotional load. Far from being a neutral or mechanical practice, lecturing is experienced intensely, with oscillations between motivation and exhaustion. Participant accounts reveal contrasting emotions, such as confidence and anxiety, clearly dependent on contextual and personal conditions. While concern and nervousness were the most frequently reported emotions in this scenario, enthusiasm, confidence, and tranquility also appeared, revealing an affective ambivalence: although lectures allow greater control over discourse and preparation, they also expose the teacher to constant evaluation, and the pressure of meeting external expectations, such as: (1) receiving feedback from a mentor teacher or class reception; (2) exhibiting expressive and motivational teaching behaviors; (3) demonstrating theoretical and conceptual mastery; (4) managing effective communication with the group.

From the circumplex perspective, emotions such as enthusiasm and satisfaction fall within the positive-valence, high-activation quadrant, signaling strong emotional engagement with teaching, particularly when communication flows smoothly and students respond positively. In contrast, confidence and tranquility are located in the positive-valence, low-activation quadrant, reflecting a regulated emotional state conducive to role stability. Negative high-activation emotions (nervousness, concern, frustration) correspond to the negative-valence, high-activation quadrant, indicating substantial emotional strain that, if unregulated, may undermine teaching quality, professional self-image, and identity formation (Scherer, 2005; Pekrun, 2006; Bandura, 1997).

Thus, lecturing emerges as an ambivalent practice, capable of promoting both high engagement and high stress. On one hand, it may activate intense negative emotions linked to public exposure, external evaluation, and fear of error; on the other, a pedagogical opportunity, as it supports the development of discourse competencies, content control, and stronger student relationships when emotions are effectively managed (Pekrun et al., 2002; Sutton, 2004). From this perspective, even adverse emotional experiences can become learning opportunities if the pre-service teacher is aware of and reflects upon their emotional state. This aligns with Pekrun’s control–value theory (Pekrun, 2006, Pekrun and Perry, 2014), which states that emotions arise from subjective evaluations of control and task value. High negative activation may be reinterpreted positively if accompanied by reflective processes and planning that strengthen teaching self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). Therefore, systematic emotional support during initial teacher education can be key in transforming lectures from a unidirectional, rigid format into more dialogic, participatory, and emotionally sustainable experiences in which knowledge is co-constructed with students.

Teaching situation: experimental or practical activities

The emotions experienced by pre-service teachers during experimental or practical activities elicited a predominance of high activation positive- valence emotions, notably joy, enthusiasm, confidence, and satisfaction, each reported at frequencies exceeding 80% in the “most of the time” and “always” categories. In Russell’s circumplex model (Russell, 1980), these emotions occupy the upper right quadrant, reflecting energizing and pleasurable experiences that Pekrun identifies as optimal for promoting intrinsic motivation, deep learning, and commitment to teaching.

From a self-efficacy perspective (Bandura, 1997), high levels of confidence and enthusiasm suggest that pre-service teachers perceived a high degree of control over practical activities with tangible results and immediate feedback reinforcing mastery. Such experiences align with STEBI findings linking practical engagement to higher perceived teaching competence (Riggs and Enochs, 1990). These findings address Objective 2, demonstrating how emotional activation is closely intertwined with pre-service teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and their appraisal of instructional demands.

Despite the predominance of positive emotions, Figure 4 also shows the presence of negative emotions such as nervousness and concern, reported at moderate levels (42 and 49%, respectively, in the category “sometimes”). These are high-activation, negative-valence emotions occupy the opposite quadrant in Russell’s model and are classified by Pekrun as negative activating emotions. Their occurrence may be related to perceptions of challenge, uncertainty, or complexity associated with managing materials, procedures, or timing. Pekrun (2006) notes that such emotions emerge when a task is valued highly but perceived as having only moderate or low controllability, a common situation in initial teacher education.

Low activation negative emotions (boredom, frustration, and rejection), occurred with low frequency in high-recurrence categories and predominate in the “never” category (70% for boredom, 64% for rejection). These emotions, are rare in this teaching context, indicating that practical activities are highly valued and relevant for future teachers. The absence of boredom and rejection indicates a high degree of cognitive and emotional engagement.

The multicomponential framework proposed by Scherer (2005) and expanded by Shuman and Scherer (2014) further explains these dynamics. The reported emotions are not isolated reactions but complex episodes involving cognitive (value and control appraisals), motivational (action tendencies), physiological (activation level), and expressive (associated behaviors) components, making the experimental setting a powerful platform for emotional development in teacher education.

In summary, the incorporation of practical and experimental activities in the initial training of science teachers generates predominantly positive and activating emotional experiences, closely linked to high levels of self-efficacy and professional commitment. These emotions reflect not only the affective state of pre-service teachers but also their perceptions of the effectiveness of such practices for teaching and learning science. In contrast to lecture-based instruction, where negative activating emotions such as worry or nervousness are more prevalent, experimental practices foster a more favorable emotional environment that should be strengthened and systematized within teacher education programs. This result fulfills Objective 3, as it shows how contextual features of lecture-based explanations and practical activities modulate emotional activation in distinct ways.

From a qualitative perspective, laboratory and experimental practices reveal a substantial emotional load experienced by pre-service teachers during pedagogical engagements in authentic contexts. Classified and analyzed through Russell’s circumplex model (Russell, 1980), these emotions underscore the central role of affect in science education, particularly in settings where theoretical, practical, and classroom management components intersect.

A salient finding within this category is the importance of active experiences, as pre-service teachers describe moments of heightened pedagogical dynamism through laboratory work, scientific games, and field trips. These situations are frequently associated with joy, an emotion of positive valence and high activation, arising from the recognition of meaningful student participation. Within Russell’s framework (1980), joy occupies the quadrant of maximum positive activation, signifying an affective state conducive to forming bonds both with the content and with students. Consistent with Pekrun (2006), joy functions as an emotional regulator that enhances motivation, commitment, and engagement by demonstrating that the strategies employed are effective and valued by learners.

Equally significant is the role of technological innovation in practice, exemplified in accounts of the integration of emerging technologies such as 3D printing and robotics in school settings. In these cases, enthusiasm emerges as the predominant emotion, also positively valence and highly activating, reflecting an energizing experience for teachers. Unlike joy, enthusiasm is not limited to immediate impact; it is linked to the perception of introducing transformative practices. Within the circumplex model, enthusiasm demonstrates motivational potential oriented toward the future, promoting creativity, innovation, and the pedagogical appropriation of non-traditional tools. This finding is particularly relevant, as it reveals that the integration of technology evokes emotions that are not merely instrumental but deeply symbolic, while simultaneously redefining the teacher’s role as a mediator between science, technology, and society.

Likewise, the qualitative research process facilitated the identification of an emergent category highlighting the theoretical mastery and fluency with which the teacher conducts experimental activities. Within this framework, the emotion of trust is salient, characterized by positive valence and a medium level of activation; this emotion arises when preservice teachers report having established a controlled environment over instruments, groups, and experimental procedures. According to Shuman and Scherer (2014), trust fulfills a regulatory and stabilizing function, sustaining teaching practice without generating emotional oversaturation. Its presence is significant due to it facilitates the construction of a reflective and autonomous practice, wherein practical knowledge, or knowing-how, is accompanied by a sense of self-efficacy that strengthens professional identity (Bandura, 1997).

Additionally, a pedagogical impact condition emerges, linked to the emotion of satisfaction. This emotion is located within the quadrant of positive valence and low-to-medium activation, it is frequently reported in teaching experiences with diverse school communities, such as those in the Amazon region. Satisfaction illustrates the transformative effect of experiential or experimental teaching. Unlike trust, satisfaction appears as a closing emotion of positive balance, reinforcing both the ethical and vocational dimensions of preservice teacher’s practice. In Russell’s model (Russell, 1980), this type of emotion contributes to the recovery of emotional equilibrium and to the construction of personal narratives that reinforce teachers’ professional commitment from community, cultural, and social perspectives.

However, such teaching situations also give rise to negative-valance emotions. Four subcategories were identified, reflecting the main challenges faced by preservice teachers: (1) mastery of disciplinary content that supports the theoretical frameworks of experimental activity; (2) exposure to external judgment and the pressures of the teaching role; (3) the condition of materials, either due to inadequate preparation or lack of access to resources prior to implementation, compounded by school limitations; and (4) scarcity of resources or adverse conditions for experimentation in educational contexts. These factors trigger emotions such as concern, nervousness, frustration, and rejection. The first three are situated in the quadrant of negative valence and high activation, which, according to Pekrun (2006), may compromise intrinsic motivation and emotional self-regulation when low task control intersects with high contextual pressure are perceived. Recurrent exposure to such experiences may undermine teaching self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997), thereby weakening the perception of professional competence.

Rejection, however, requires particular attention, while it shares negative valence, it is characterized by low emotional activation, and is classified as a deactivating emotion within both Russell’s model and Pekrun’s 2×2 matrix. Unlike other emotions, rejection does not necessarily arise from a single incident, but rather accumulates through persistent structural constrains. This accumulation may lead preservice teachers to develop affective disengagement from teaching, jeopardizing their connection with the school as a formative space. According to Frenzel et al. (2015) and Heng et al. (2024), such emotions not only diminish teacher well-being but also shape maladaptive attitudes that risk becoming entrenched if not addressed both pedagogically and emotionally.

In conclusion, the analysis of experimental teaching practices demonstrates that the emotional dimension constitutes a central axis of pre-service teachers’ pedagogical experience. Positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, trust, and satisfaction not only motivate but also establish lasting affective dispositions that promote commitment and identity. Conversely, negative emotions such as concern, nervousness, frustration, and rejection, reveal zones of emotional tension and vulnerability that require attention within teacher education programs. The circumplex model of Russell (1980) and Pekrun’s 2×2 matrix (Pekrun, 2006) provide conceptual tools for mapping and analyzing these emotional experiences, acknowledging that teaching science entails navigating a complex emotional path shaped by practice, reflection, and the pursuit of professional transformation.

It is important to highlight that the identification of emotional confusion among pre-service teachers emerged repeatedly in the focus groups and constitutes a substantive empirical finding derived from the inductive analysis. Participants showed difficulty distinguishing among closely related emotions—such as joy, motivation, and satisfaction, or sadness, frustration, and boredom. This ambiguity appeared in their spontaneous language, in hesitations when describing classroom experiences, and in the interchangeable use of emotional terms as if they were synonyms. This phenomenon aligns with previous research in education and affective science (Barrett, 2017; Pekrun, 2021), which documents limited emotional granularity among young adults and pre-service teachers. Therefore, this conclusion is not speculative; it is grounded in recurring discursive patterns and supported by contemporary theoretical perspectives.

Regarding the limitations of the study, several aspects should be acknowledged. These include the size and composition of the focus groups, the self-selection of participants, and the predominance of students from natural science programs compared with those from mathematics or technology. Future research would benefit from incorporating longitudinal designs and comparing emotional activation at different stages of teacher education. Although the STEBI is a widely validated instrument and its psychometric properties were replicated in this study, it focuses on beliefs related to science teaching self-efficacy and does not directly assess the physiological or expressive components of emotional arousal. For this reason, qualitative techniques were incorporated to capture the depth and complexity of participants’ affective experiences, enabling a more robust and complementary triangulation of the findings.

Conclusion

These conclusions respond directly to the three objectives of the study by (1) characterizing emotional patterns in lecture-based and practical teaching situations, (2) examining how these emotions relate to pre-service teachers’ perceived self-efficacy, and (3) identifying how instructional contexts shape emotional activation.

The results from the STEBI questionnaire applied to pre-service teachers indicate differentiated emotional activation depending on the type of teaching situation, thereby addressing Objective 1 of this study. Experimental activities and the use of conceptual models are associated with higher levels of perceived self-efficacy and positive emotions, while lecture-based instruction generates a broader range of emotions, including moderately activated negative ones.

Russell’s circumplex model (Russell, 1980) and Feldman-Barrett and Russell (1998) helps explain this differentiation, as it organizes emotions along valence (pleasant–unpleasant) and activation (high–low). Lectures often elicit insecurity or boredom, particularly when pre-service teachers struggle to connect with students or sustain a coherent discourse. These emotions, situated in negative valence and low-to-medium activation, exemplify what Scherer (2005) describes as negative appraisals of situational self-efficacy, which may inhibit teaching performance.

By contrast, experimental activities are associated with high-activation, positively valenced emotions such as enthusiasm, curiosity, and satisfaction, particularly when tasks are successfully completed or results are meaningfully interpreted. Located in the upper-right quadrant of the circumplex model, these emotions promote an emotionally favorable environment for active learning. According to Pekrun (2006), such emotions enhance cognitive and motivational engagement, strengthening perceptions of self-efficacy, an outcome aligned with Objective 2, which examined the relationship between emotional activation and perceived teaching competence, particularly when students perceive control over the task and attribute formative value to it.

Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy suggests that competence perceptions increase when pre-service teachers engage in tasks that show tangible outcomes, provide positive feedback, or allow performance comparison with peers. This finding is consistent with Bleicher (2004), who reports that confidence in teaching science strengthens when future teachers achieve both conceptual and methodological mastery, particularly in experimental settings.

A central conclusion of the study is that emotional activation and self-efficacy are interrelated and dynamic processes, influenced by variables such as institutional context, prior experience, perceived control, and the value attributed to the task. Positive emotions, whether high or low activation, such as joy, enthusiasm, or calmness, tend to strengthen professional vocation, didactic achievement, confidence in the teaching role, and commitment to teacher education. Negative emotions such as frustration, concern, or rejection may generate doubts about belonging to the profession, confidence in training quality and perceived capacity to manage classroom challenges.

The study also highlights a recurring difficulty among pre-service teachers in clearly identifying their emotions. Focus groups revealed frequent confusion, for example, between joy, motivation, and satisfaction, or between sadness, boredom, and frustration, highlighting the need for teacher education programs to include systematic emotional literacy training, fostering reflection on affective dimensions of practice.

Finally, and consistent with Objective 3, the findings show that contextual features of teaching situations significantly shape emotional activation. Teaching self-efficacy is reinforced by positive emotions, while negative high-activation emotions tend to undermine confidence. This highlights the need for teacher preparation to focus not only on disciplinary and pedagogical knowledge but also on the development of emotional regulation skills, equipping future teachers to navigate the challenges of science teaching more effectively.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité de Etica Universidad Pedagógica Nacional - Consentimiento informado aprobado. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This project was funded by the National Pedagogical University of Colombia through the Internal Research Call of the Research Center (CIUP), within the framework of the project “Teaching situations that activate emotions in teachers in training of the Faculty of Science and Technology” (Code DFI-703-25).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acevedo-Díaz, J. A., García-Carmona, A., Aragón-Méndez, M., and Oliva-Martínez, J. M. (2017). Modelos científicos: significado y papel en la práctica científica. Rev. Cient. 3, 155–166. doi: 10.14483/23448350.12288

Adadan, E. (2020). Analyzing the role of metacognitive awareness in preservice chemistry teachers’ understand-ing of gas behavior in a multirepresentational instruction setting. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 57, 253–278. doi: 10.1002/tea.21589

Allaire, F. S., King, J. P., and Frenzel, A. C. (2023). Measuring science-teaching affect: first results on the science teaching emotions scales (Sci-TES). J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 35, 465–479. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2023.2291884

Alméciga Castro, A. (2024). El paradigma de las emociones en la educación en ciencias, aportes a la formación de profesores. Available online at: Bio Grafía, 16(Extraordinario). Recuperado a partir de Available online at: https://revistas.upn.edu.co/index.php/bio-grafia/article/view/21342 (Accessed March 12, 2024).

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191,

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

Bellocchi, A., Ritchie, S. M., Tobin, K., King, D., Sandhu, M., and Henderson, S. (2014). Emotional climate and high quality learning experiences in science teacher education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 51, 1301–1325. doi: 10.1002/tea.21170

Bleicher, R. E. (2004). Revisiting the STEBI-B: measuring self-efficacy in preservice elementary teachers. Sch. Sci. Math. 104, 383–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-8594.2004.tb18004.x

Borrachero, A. B., Brígido, M., Mellado, V., and Bermejo, M. L. (2013). Relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and emotions of future teachers of physics. Asia Pac. Forum Sci. Learn. Teach. 14, 1–11.

Borrachero, A. B., Brígido, M., Mellado, L., Gramipour, E., and Mellado, V. (2014). Emotions in prospective secondary teachers when teaching science content, distinguishing by gender. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 32, 182–215. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2014.909800

Borrachero Cortés, A. B. (2015). Las emociones en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de las ciencias en educación secundaria. Ensenanza De Las Ciencias 33, 199–200. doi: 10.5565/rev/ensciencias.1823

Borrego, E., Borrachero, A., Brígido, M., and Mellado, V. (2013). Las emociones sobre la enseñanza-aprendizaje de las ciencias y las matemáticas de futuros profesores de Secundaria. Rev. Eureka Ensenanza Divulg. Cienc. 10, 514–532.

Bradley, M., and Lang, P. (1994). Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 25, 49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9,

Bravo Lucas, E., Brígido Mero, M., del Hernández Barco, M. A., and Mellado Jiménez, V. (2022). Las emociones en ciencias en la formación inicial del profesorado de infantil y primaria. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profesor. 36, 57–74. doi: 10.47553/rifop.v97i36.1.92426

Bredo, E. (2009). Comments on Howe: getting over the methodology wars. Educ. Res. 38, 441–448. doi: 10.3102/0013189x09343607

Brígido, M., Borrachero, A. B., Bermejo, M. L., and Mellado, V. (2013). Prospective primary teachers’ self-efficacy and emotions in science teaching. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 200–217. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2012.686993

Bryman, A. (2008). “The end of paradigm wars?” in SAGE hand-book of social research methods. eds. P. Alasuutari, L. Bickman, and J. Brannen (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 12–26.

Burić, I., Slišković, A., and Sorić, I. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and self-efficacy: examining reciprocal relations. Front. Psychol. 11:1650. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01650,

Camilloni, A. R. W. de, Celman, S., Litwin, E., and de Palou Maté, M. C. (1998). La evaluación de los aprendizajes en el debate didáctico contemporáneo. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Chang, M. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 21, 193–218. doi: 10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y