- Faculty of Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

This study provides a cross-cultural analysis of educational leadership’s impact on digital pedagogy professional development (PD) in Ghana and China. The objective was to identify effective leadership styles and strategies for overcoming implementation barriers, and to assess their impact on educator competence and equity. A mixed-methods approach was used, surveying 412 academic leaders and policymakers in Ghana (n = 180) and China (n = 232) with the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) and a bespoke Digital Education PD Leadership Practices Inventory (DEPLPI), supplemented by 48 semi-structured interviews. Statistical analysis revealed significant national differences; Chinese leaders scored higher on transformational leadership (p < 0.001), while Ghanaian leaders scored higher on transactional styles (p < 0.001) and stakeholder collaboration (p < 0.001). In Ghana, transformational leadership was a significant predictor of enhanced educator digital competence, confidence, and perceived PD success (p < 0.01). Inadequate infrastructure was a primary barrier, but leadership effectively mitigated challenges related to low digital literacy and resistance to change. The study concludes that leadership is a central driver of successful digital education PD in West Africa. Fostering culturally responsive, transformational leadership is critical for navigating systemic barriers and promoting equitable, sustainable digital learning environments. Policy interventions should prioritize leadership development to empower educators and students in the digital age.

1 Introduction

The 21st century has introduced an era where digital technologies are increasingly essential to global educational transformation (Laufer et al., 2021). In West Africa, a region characterized by diverse socioeconomic landscapes and growing youth populations, the promise of digital education to improve access, quality, and equity is especially compelling. However, realizing this potential critically depends on educators’ ability to incorporate these technologies into their teaching practices effectively. Professional development (PD) programs are therefore vital for equipping teachers with the necessary digital skills. The success of such PD initiatives, in turn, is greatly affected by the quality and approach of educational leadership (Jameson et al., 2022). The swift uptake of digital tools, accelerated by global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, has revealed both the opportunities and challenges of digital education systems worldwide, including in West Africa (Dewey et al., 2020). While technology provides opportunities for innovative teaching and learning, its effective utilization is often hindered by issues such as inadequate infrastructure, limited financial resources, varying levels of digital literacy among educators, and resistance to change (Ullah et al., 2019). Educational leaders ranging from institutional heads and policymakers to PD coordinators play a crucial role in navigating these challenges and creating a supportive environment for successful digital integration and professional growth (Karaköse et al., 2024).

This study aims to explore the multifaceted impact of leadership on PD for digital education in West Africa, with a particular focus on Ghana as a case study and comparative insights from China to highlight diverse leadership approaches. Three primary objectives guide the research: to identify effective leadership styles and strategies, analyze the specific leadership styles (e.g., transformational, transactional) and strategies employed by educational leaders in West Africa that most effectively foster successful, sustainable, and culturally responsive PD programs for digital education. This involves understanding how leaders inspire vision, manage change, and promote innovation within their institutions (Antonopoulou et al., 2021). To evaluate how educational leadership directly influences the mitigation of key barriers (e.g., infrastructure limitations, funding constraints, resistance to change, digital literacy gaps) to implementing effective digital education PD for educators across diverse West African contexts. This includes identifying actionable leadership practices for resource mobilization, policy advocacy, and fostering a supportive institutional culture (Perry et al., 2007). To determine the measurable impact of targeted leadership interventions (e.g., policy development, resource allocation, mentoring, and fostering collaborative cultures) on enhancing educators’ digital pedagogical competence and confidence.

This study aims to explore the multifaceted impact of leadership on PD for digital education in West Africa, with a particular focus on Ghana as a case study, and drawing comparative insights from China to highlight diverse leadership approaches. Three primary objectives guide the research: to identify effective leadership styles and strategies, to analyze and identify the specific leadership styles (e.g., transformational, transactional) and strategies employed by educational leaders in West Africa that most effectively foster successful, sustainable, and culturally responsive PD programs for digital education. This involves understanding how leaders inspire vision, manage change, and promote innovation within their institutions (Brown and Wyatt, 2010). To evaluate how educational leadership directly influences the mitigation of key barriers (e.g., infrastructure limitations, funding constraints, resistance to change, digital literacy gaps) to implement effective digital education PD for educators across diverse West African contexts.

This includes identifying actionable leadership practices for resource mobilization, policy advocacy, and fostering a supportive institutional culture (Anderson et al., 2023). It also aims to determine the measurable impact of targeted leadership interventions (e.g., policy development, resource allocation, mentoring, and fostering collaborative cultures) on enhancing educators’ digital pedagogical competence and confidence (Karaköse et al., 2024). Furthermore, it aims to evaluate the subsequent impact on enhancing equitable access and learning outcomes for students in West Africa, especially in underserved or marginalized communities. The need for effective digital leadership in education is not limited to one region (Brown and Wyatt, 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, compelled a global shift to online learning, testing the readiness and flexibility of educational systems worldwide (Kratz, 2022). This period underscored the vital role of leadership in managing crises, ensuring continuity of learning, and bridging the digital divide (Jenkins, 2009; Greenhow, 2020). In contexts like West Africa, existing challenges related to digital infrastructure and access were often worsened, making strong leadership even more essential.

2 A comparative analysis of educational leadership paradigms

Higher education institutions worldwide play a crucial role in shaping future leaders by nurturing cognitive, social, and ethical skills. This study compares leadership development frameworks in two contexts: China, with its Confucian-influenced educational traditions, and the University of Ghana, which reflects post-colonial and community-focused values relevant to the broader West African region. By analyzing institutional structures, student groups, and gender dynamics, this review highlights cultural and structural factors influencing leadership education, offering a context for understanding leadership for digital PD in West Africa. Chinese higher education emphasizes collective harmony and societal contribution, reflecting the influence of Confucian principles (Karaköse et al., 2024). Universities like Tsinghua and Peking integrate leadership training through state-aligned initiatives and student organizations. Clubs often focus on technology, traditional arts, and innovation, reflecting national priorities like the “Made in China 2025” strategy. Student councils, though regulated, emphasize civic responsibility and political loyalty, aligning with broader socialist values.

Leadership curricula emphasize teamwork, moral integrity, and adaptive problem-solving, preparing students for roles in governance and industry. The University of Ghana operates within a higher education context that prioritize community engagement and pan-African leadership. Student clubs, such as the Debate Society, Entrepreneurs’ Hub, and Cultural Troop, address local challenges like sustainable development and cultural preservation. The Students’ Representative Council (SRC), elected democratically, advocates for student welfare and organizes civic activities, fostering a sense of agency and social accountability. Leadership programs often blend Western pedagogical models with indigenous philosophies, emphasizing empathy and communal well-being. This community-centric approach is vital when considering leadership for PD that must be culturally responsive and address local needs (Brown and Wyatt, 2010).

In China, traditional gender roles persist, yet women are increasingly assuming leadership roles in academia and the technology sector. Studies have noted that female students often excel in collaborative leadership, although cultural biases may limit their visibility in male-dominated fields. Conversely, at the University of Ghana, women’s leadership is on the rise, supported by initiatives like the Women’s Commission (Anderson et al., 2023). Research indicates that Ghanaian female students excel in conflict resolution and grassroots mobilization, leveraging relational skills rooted in communal culture. Both contexts, however, face challenges in bridging gender gaps in leadership representation. China’s leadership model emphasizes collectivism and alignment with the state, while Ghana focuses on community-centric and decolonial approaches. Chinese clubs align with national agendas, whereas Ghanaian groups concentrate on localized societal issues. Both regions exhibit increasing female leadership; however, cultural norms influence opportunities differently in China through gradual institutional change, whereas in Ghana, they are influenced by grassroots advocacy.

This comparative analysis highlights how cultural, historical, and political contexts shape leadership education (Kratz, 2022). While China’s structured, state-integrated approach contrasts with Ghana’s community-driven model, both aim to develop ethical, adaptable leaders. Understanding these differences can guide how leadership for digital PD is understood and implemented in West Africa, ensuring it is both practical and suitable to the local context. For example, the focus on community engagement in Ghana indicates that leadership strategies for digital PD in West Africa could benefit from participatory approaches involving local stakeholders and addressing specific community needs.

Gender dynamics further distinguish these paradigms. While Chinese women excel in collaborative roles within structured systems, cultural biases remain in male-dominated STEM fields. In Ghana, women lead community-focused initiatives but encounter obstacles in formal political spheres (Anderson et al., 2023). Both countries utilize technology differently: China employs AI tools for leadership simulations, while Ghana relies on mobile platforms for community engagement. Addressing systemic barriers in both contexts is essential. This comparative perspective helps frame the subsequent investigation into the role of leadership in digital education professional development, specifically within the West African context, using Ghana as a primary example. The study will examine how leadership styles manifest in this setting and how they can be improved to support educators in the digital age, ultimately fostering more effective and equitable education across the region. Developing digital leadership skills among educational administrators is vital for this transformation (Ayyaswamy, 2024; Anwar and Saraih, 2024). Additionally, understanding the conceptual progression of digital leadership research offers a basis for recognizing effective practices (Karaköse et al., 2024).

3 Research methodology

3.1 Study design

This comparative analysis uses a mixed-methods approach to examine educational leadership paradigms and their influence on digital education professional development. The study primarily focuses on universities in Ghana as representative of the West African context, with universities in China serving as a comparison to illustrate cultural and systemic differences and their implications for leadership practices. This design combines quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews to capture measurable leadership practices (e.g., styles, strategies) and the cultural contexts (e.g., values, norms) that shape them. The mixed-methods approach enables a thorough exploration of systemic, cultural, and policy factors affecting leadership in higher education and its role in promoting effective PD for digital education.

3.2 Sample

The study focused on academic leaders (e.g., deans, department heads, senior faculty involved in PD) and administrative policymakers from six universities: three in Ghana and three in China. These institutions were selected for comparison of cultural, institutional, and policy contexts relevant to leadership in digital education. A stratified purposive sampling strategy ensured representation across different types of universities. In Ghana, the sample included a flagship public university renowned for its comprehensive programs and national influence, a technical university specializing in vocational and applied technology education, which is vital for digital skills development, and a private university with active community engagement initiatives, reflecting grassroots approaches to education. This selection aimed to capture diverse leadership experiences within the West African higher education landscape.

In China, for comparison, institutions included a “Double First-Class” elite research-focused university, a provincial university emphasizing regional equity, and a polytechnic specializing in applied sciences. A total of 412 participants completed the survey: 232 respondents from China (62% male, 38% female) and 180 from Ghana (55% female, 45% male). These demographics highlight interesting trends in gender representation, with a male majority among Chinese respondents and a female majority among Ghanaian respondents in leadership or policy roles related to education. Additionally, 48 semi-structured interviews (24 per country, focusing on those directly involved in PD for digital education in Ghana) were conducted with senior administrators and PD coordinators to contextualize quantitative findings and explore leadership practices, challenges, and successes related to digital education PD. This mixed-methods approach enabled a comparative analysis of leadership practices and decision-making in higher education, with a specific focus on how these influence PD in the digital age in West Africa (Ghana), using China for contrasting perspectives.

3.3 Study instrumentation

The study employed two primary quantitative tools and a qualitative interview guide, specifically the Adapted Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). Based on Bass and Avolio (1997) framework, this 45-item instrument assessed transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles among educational leaders. Participants rated statements on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The instrument was adapted to reflect cultural nuances relevant to educational leadership in both contexts, such as items reflecting Confucian collectivism in China and Ubuntu communalism and community engagement in Ghana, especially regarding PD initiatives. The reliability and validity of the adapted MLQ were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and confirmatory factor analysis for each cultural setting.

To assess leadership practices relevant to digital education professional development (PD), this study used the Digital Education PD Leadership Practices Inventory (DEPLPI), a researcher-designed instrument. The DEPLPI was informed by the foundational five leadership practices identified by Kouzes and Posner (2012) and integrated with contemporary frameworks on digital leadership in educational contexts (Antonopoulou et al., 2025; Karaköse et al., 2021; Zhong, 2017). The inventory consists of 30 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale, and is structured across five distinct dimensions. The first dimension, Transformational Visioning for Digital PD, assesses the leader’s ability to align institutional PD objectives with broader national digital education policies and local cultural values. This involves creating and communicating a clear, shared vision for technology integration that is supported by stakeholders (A’mar and Eleyan, 2021; Thannimalai and Raman, 2018). The second dimension, Ethical Governance in Digital Environments, focuses on addressing critical issues such as digital equity (Pittman et al., 2021), data privacy within PD activities, and the transparent allocation of resources for digital tools and training. This dimension reflects the importance of digital citizenship in leadership (Zhong, 2017).

Stakeholder Collaboration for PD Success is the third dimension, which measures the leader’s capacity to engage a wide range of stakeholders, including educators, students, technical staff, and external partners, in the co-design and implementation of digital PD. This collaborative approach is crucial for building effective professional learning communities and strategic partnerships (Nzarugarura and Ndagijimana, 2025). The fourth dimension, Innovation Adoption and Support in PD, examines practices related to leading the integration of new digital tools and pedagogies into PD programs. A key aspect of this dimension is the provision of continuous, ongoing support for educators as they adopt these innovations (Karaköse et al., 2021; Twining et al., 2013).

Finally, the fifth dimension, Resilience and Barrier Mitigation in Digital PD, evaluates leadership in overcoming systemic challenges. This includes addressing infrastructure deficits, common in contexts such as Ghana, as well as navigating funding shortages and managing resistance to technological change among educators (A’mar and Eleyan, 2021; Richardson and McLeod, 2011). To complement the quantitative data from the DEPLPI, semi-structured interviews were conducted. An interview guide was developed to facilitate in-depth exploration of educational leaders’ perceptions and experiences regarding their roles in fostering PD for digital education, providing richer context for the survey findings. While the DEPLPI provides a focused assessment of digital leadership practices, it is important to note its limitations. The instrument does not explicitly assess the multimodal aspects of leadership required in the digital age, such as the specific competencies needed to lead effectively in fully virtual or hybrid environments, which have their own unique challenges (Wiederhold, 2020).

3.4 Data collection

A sequential explanatory mixed-methods data collection strategy was employed over a four-month period. Phase 1: Quantitative data collection involved online surveys (using Qualtrics) that contained the adapted MLQ and the DEPLPI, which were distributed to a selected sample of academic leaders and administrative policymakers across six universities in Ghana and China. In Ghana, where internet access could be limited for some potential participants at regional technical universities, paper-based versions of the survey were also provided and administered with the assistance of local research assistants. Surveys were predominantly conducted in English, the official language of instruction. In China, surveys were translated into Mandarin by a professional translation service and back-translated to ensure accuracy. The online platform remained the primary method of distribution. Initial contact was made through official university channels, followed by personalized email invitations containing the survey link or details for in-person administration. Reminder emails were sent after two and 4 weeks to encourage participation. Participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. A total of 412 complete responses were received, with 180 from Ghana and 232 from China.

Phase 2: Qualitative Data Collection. Following the initial analysis of the quantitative data, participants for semi-structured interviews were purposefully selected from survey respondents who expressed a willingness to participate further. Selection focused on individuals in key leadership roles directly influencing digital education PD (e.g., heads of e-learning departments, PD coordinators, and deans championing digital initiatives). A total of 48 interviews were conducted: 24 in Ghana and 24 in China. In Ghana, interviews were mainly conducted face-to-face at the participants’ institutions or virtually via Zoom/Skype, depending on preference and location. Interviews were held in English and lasted approximately 45–60 min. In China, interviews were predominantly conducted virtually via WeChat or Tencent Meeting, in Mandarin, by bilingual research team members. These also lasted 45–60 min. All interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent. Additionally, institutional documents such as strategic plans, digital education policies, PD program outlines, and annual reports were collected from participating universities to triangulate interview data and provide contextual understanding. International reports from organizations like the World Bank on digital education in these regions were also reviewed (Kaufmann et al., 2009). All data collection procedures received ethical approval from the relevant institutional review boards in both countries.

3.5 Data analysis

A multi-stage data analysis process was implemented to integrate the quantitative and qualitative findings from the study. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of leadership styles and their impact on digital professional development (PD) in the selected national contexts.

3.6 Quantitative data analysis

Survey data derived from the adapted Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) and the Digital Education Professional Development Leadership Practices Instrument (DEPLPI) were analyzed using SPSS version 27. To ensure the transparency and credibility of the analysis, cases with missing data were excluded on a case-by-case basis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were calculated for all demographic variables as well as for the scores on leadership styles and digital PD leadership practices. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) were employed to compare leadership styles, specifically transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire, and digital PD leadership practices across different groups. These comparisons were made based on national context (Ghana vs. China), institutional type, and gender demographics. This statistical approach helped to identify whether specific leadership approaches were more prevalent or perceived as more effective within particular settings. To identify predictors of leadership effectiveness in fostering digital education PD, multiple regression analyses were conducted (Dewey et al., 2020). The dependent variables in these models included the perceived success of PD programs and educator engagement in digital PD. The independent variables comprised leadership styles, specific leadership practices from the DEPLPI, institutional support, and resource availability. This analysis was particularly focused on the Ghanaian data to address the core research questions for West Africa. Furthermore, independent samples t-tests were utilized for specific comparisons, such as contrasting the mean scores on certain leadership practices between leaders who had overseen demonstrably successful digital PD initiatives and those who had not.

3.7 Qualitative data analysis

Interview transcripts were managed and systematically analyzed using NVivo 12. The data collection and analysis process followed established protocols for qualitative research. All interview audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. Interviews conducted in Mandarin were first transcribed in the original language and then translated into English by professional translators with expertise in educational research. To ensure fidelity, the accuracy of these translations was verified through back-translation and a final review by bilingual members of the research team. A systematic thematic analysis approach was used to interpret the qualitative data. This process involved several distinct stages. The research team engaged in repeated reading of the transcripts to gain a deep understanding of the data. Initial codes were generated based on recurring concepts and themes related to leadership roles, strategies, challenges, and their impacts on digital PD. Codes were grouped into potential overarching themes that captured broader patterns in the data. The potential themes were reviewed to ensure they accurately represented the dataset and were distinct from one another. Final themes were defined and named to articulate their essence clearly. Examples of final themes include “Visionary Leadership for Digital Change,” “Navigating Resource Scarcity,” “Fostering a Culture of Digital Experimentation,” and “Addressing Digital Equity in PD.”

3.8 Integration of findings

The findings from the quantitative and qualitative analyses were integrated at the interpretation stage to develop a holistic understanding of the research phenomena. This blended approach ensured a more nuanced and robust interpretation of the results. For instance, statistical findings on the prevalence of specific leadership styles were enriched and contextualized by qualitative descriptions of how these styles were enacted in daily practice. Similarly, qualitative insights from the interviews helped explain complex statistical relationships, such as why a particular leadership practice emerged as a strong predictor of PD success, specifically within the Ghanaian context. This integrated methodology was crucial for understanding how cultural paradigms intersect with institutional policies and individual leadership actions to shape the outcomes of digital education PD, particularly in the context of West Africa (Ghana).

4 Results

4.1 Participant demographics

A total of 412 academic leaders and administrative policymakers participated in the study’s survey component. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the participants from Ghana and China. The demographic data reveal a higher proportion of female leaders among the Ghanaian respondents than the Chinese sample. Both groups predominantly fall within the 40–59 age range and possess doctoral degrees. Experience in leadership roles is fairly distributed, with the largest cohort having 5–10 years of experience. Most respondents hold positions at universities, while a smaller percentage are affiliated with governmental or non-governmental organizations. This diversity in professional settings enriches the insights gathered from the survey, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by academic leaders in both countries. Furthermore, the data suggest that while there are similarities in leadership experiences, cultural differences may influence decision-making processes and institutional priorities.

4.2 Identify effective leadership styles and strategies

Table 2 presents mean scores for transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles, as well as key DEPLPI dimensions, for leaders in Ghana and China. The findings reveal notable differences in leadership preferences between the two countries, underscoring the significance of cultural context in shaping practical leadership approaches and the varying impacts these styles have on team dynamics and organizational performance. Leaders in China reported significantly higher mean scores for overall transformational leadership than those in Ghana. Conversely, Ghanaian leaders scored significantly higher on transactional and laissez-faire leadership. Within the DEPLPI practices, Ghanaian leaders scored significantly higher on “Stakeholder Collaboration for PD Success,” aligning with qualitative findings that emphasize the importance of community engagement.

Chinese leaders scored higher on “Innovation Adoption and Support in PD” and “Resilience and Barrier Mitigation,” possibly reflecting the strength of state-driven tech initiatives and resource allocation. Qualitative interviews with Ghanaian leaders underscored the importance of a participatory and empathetic approach. The data also suggests that leaders in Ghana tend to favor transformational styles, which emphasize inspiration and motivation. By contrast, their Chinese counterparts lean toward transactional methods that focus on structured tasks and rewards. This divergence underscores the need for leaders to adapt their strategies to align with their teams’ cultural values and expectations, ultimately fostering a more cohesive and productive work environment. Additionally, understanding these preferences can help organizations tailor their leadership development programs to enhance effectiveness across diverse cultural landscapes.

4.3 Assess leadership’s role in overcoming implementation barriers

Table 3 presents leaders’ perceptions of key barriers to digital education PD in Ghana and the perceived effectiveness of leadership strategies in mitigating these barriers. Inadequate digital infrastructure and time constraints were perceived as the most severe barriers for educators in Ghana. Leadership strategies to address low digital literacy and educator resistance to change were rated as the most effective. A PD coordinator from a Ghanaian technical university noted, “Our biggest challenge was internet connectivity. Leadership has pushed for partnerships with telecom companies, which have helped, but it remains an ongoing battle. However, when we focused on efficient, hands-on training for basic tools, and showed teachers how it could make their lives easier, we saw real progress.” Qualitative data further revealed that leaders who actively advocated for resources, built coalitions with external stakeholders, and fostered a culture of experimentation successfully navigated these barriers (Brown and Wyatt, 2010).

Table 3. Perceived barriers to digital PD and effectiveness of leadership mitigation strategies in Ghana (n = 180).

4.4 Measure leadership impact on educator competence and equity

The impact of leadership interventions on educator digital competence and perceived improvements in student equity was assessed through survey items and qualitative feedback. Table 4 presents mean scores for these impacts in Ghana. Leadership interventions focusing on mentoring/peer support and resource allocation were perceived as having the most significant impact on educator competence and confidence. Leadership support addressing the digital divide among students was rated highest for its impact on equitable access. A senior faculty member in Ghana commented, “When our HoD actively sought funds for tablets for students from disadvantaged backgrounds and ensured our PD included strategies for inclusive digital teaching, it made a huge difference. Teachers felt more equipped and motivated to reach every student.”

Table 4. Perceived leadership impact on educator competence and student equity in Ghana (n = 180, Scale 1–5, 5 = Strong Impact).

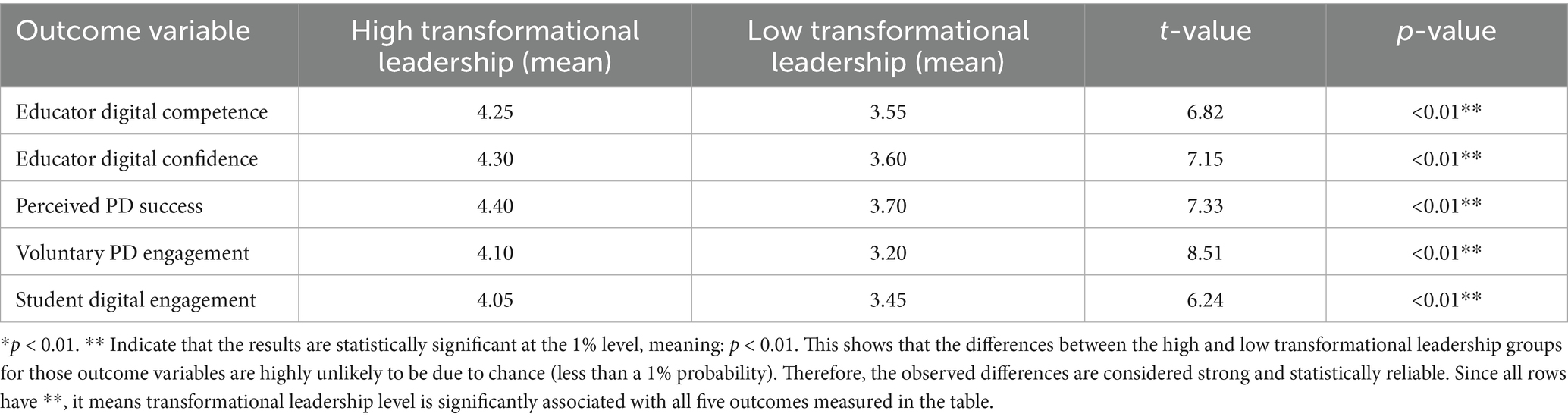

The results indicate that leaders perceived as exhibiting higher levels of transformational leadership were associated with significantly higher self-reported educator competence, confidence, perceived PD program success, voluntary engagement in PD, and perceived student digital engagement. This underscores the critical role of transformational leadership qualities in driving effective digital education PD and its subsequent positive outcomes in the West African context.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the critical and multifaceted role of educational leadership in shaping the landscape of professional development (PD) for digital education in West Africa, with Ghana serving as a key exemplar. The results underscore that specific leadership styles and strategies are more conducive to fostering successful, sustainable, and culturally responsive PD programs, particularly in contexts marked by resource constraints and evolving digital infrastructures. The quantitative data indicate that transformational leadership was associated with more positive PD outcomes in Ghana (Table 5). This aligns with extensive research showing that transformational leadership is particularly potent during periods of change and innovation, such as the integration of digital technologies in education (Antonopoulou et al., 2021; Niță and Guțu, 2023). The significantly higher scores on transformational leadership among Chinese leaders compared to their Ghanaian counterparts (Table 2) may reflect different systemic and cultural expectations; however, the positive impact of this style in Ghana is clear.

Table 5. T-tests comparing outcomes by level of perceived transformational leadership in Ghana (n = 180).

Qualitative findings further enriched this understanding, showing that Ghanaian leaders who successfully drove digital PD initiatives often employed strategies rooted in participation and empathy. They emphasized the importance of building trust, fostering a shared vision, and providing tailored support to educators. The high rating for “Stakeholder Collaboration for PD Success” among Ghanaian leaders (Table 2) is particularly noteworthy. This suggests that leadership that actively engages educators, students, and the broader community in the PD process in the West African context is more likely to achieve buy-in and sustainable impact. This resonates with the community-oriented values observed in Ghanaian higher education paradigms and the importance of social capital in development initiatives (World Bank, 1988). The comparative data from China, where leaders scored higher on practices like “Innovation Adoption and Support,” possibly driven by state mandates, highlights that effective leadership strategies can be context-dependent. While West African leadership may benefit from structured approaches, the relational and collaborative elements appear paramount.

The study identified significant barriers to digital PD in Ghana, including inadequate infrastructure, limited funding, and educator time constraints (Table 3). These challenges are common in many developing countries (Angwaomaodoko, 2023). The effectiveness of leadership in mitigating these barriers was evident. Strategies such as advocating for resources, forging partnerships, and fostering a culture of experimentation were highlighted in qualitative interviews. Leaders who were proactive in seeking solutions and resilient in the face of setbacks were perceived as more effective. The finding that leadership strategies targeting low digital literacy and educator resistance to change were rated as most effective (Table 3) is crucial. This suggests that while systemic issues, such as infrastructure, are more complex for individual institutional leaders to resolve completely, leadership can still make a significant difference in human capital development and cultural shifts. By providing foundational training, showcasing success stories, and offering incentives, leaders can build momentum for digital adoption. The higher scores for Chinese leaders on “Resilience and Barrier Mitigation” (Table 2) might reflect more centralized support systems, whereas Ghanaian leaders often rely on local ingenuity and collaborative problem-solving.

This highlights the importance for West African leaders to be skilled networkers and effective resource mobilizers. The study demonstrated a clear link between targeted leadership interventions and enhanced educator digital competence, confidence, and subsequent improvements in student equity (Tables 4, 5). Interventions such as establishing mentoring and peer support systems, allocating resources for tools and training, and fostering a collaborative culture were perceived to have a substantial positive impact. This aligns with literature emphasizing the importance of supportive environments for teacher learning and professional growth (Ghanney, 2024).

The finding that higher transformational leadership was associated with better outcomes across multiple domains (Table 5) underscores the power of this leadership style to drive educational improvement. By their nature, transformational leaders inspire and empower their teams, which is essential when asking educators to adopt new and sometimes challenging digital practices (Anwar and Saraih, 2024). Crucially, leadership support for addressing the digital divide among students was rated highest for its impact on equitable access (Table 4). This underscores that effective leadership in the digital age is not just about technological integration but also about ensuring that these technologies narrow, rather than widen, existing equity gaps (Laufer et al., 2021). Leaders who prioritize equity in their digital PD programs play a vital role in creating more just educational systems. The challenges of digital transformation in higher education, including the need for effective leadership to manage institutional change and overcome resistance, are well-documented (Carvalho et al., 2022). The findings have several important implications for educational policy and practice in West Africa (Ghana): Policymakers and institutions should invest in developing transformational leadership capacities among educational leaders. This includes training in change management, strategic communication, resource mobilization, and the fostering of collaborative cultures. PD programs for digital education must be designed with the specific cultural and resource contexts of West Africa in mind. Leadership should champion approaches that are participatory, practical, and responsive to local needs and challenges.

Leaders should actively build networks and partnerships with government agencies, NGOs, the private sector, and communities to pool resources, share expertise, and address systemic barriers, such as inadequate infrastructure (Kaufmann et al., 2009). Leadership must ensure that digital education initiatives and associated PD programs are designed to promote equity. This includes advocating for equitable access to technology for all students and training educators in inclusive digital pedagogies. The rapid changes brought by events like the COVID-19 pandemic have underscored the need for agile and responsive educational leadership (Dewey et al., 2020). Digital leadership, as an evolving concept, requires a blend of vision, technical understanding, and strong interpersonal skills to navigate the complexities of digital transformation (Jameson et al., 2022; Karaköse et al., 2024).

The study demonstrated a clear link between targeted leadership interventions and enhanced educator competence and student equity (Tables 4, 5). Interventions such as mentoring, resource allocation, and fostering a collaborative culture had a substantial positive impact, aligning with literature on supportive environments for teacher growth (Mikkonen, 2022). Crucially, leadership support for addressing the student digital divide was rated highest in terms of its impact on equity (Table 4). This highlights that effective digital leadership is not just about technology but about social justice, ensuring that technology narrows, rather than widens, equity gaps (Kier, 2022).

Future research could expand this work by, conducting longitudinal studies to track the long-term impact of leadership interventions on PD and student outcomes. Including direct measures of educator digital skills and student learning (Sidiki et al., 2025). Expanding the research to other West African countries to capture a broader range of contexts and leadership approaches. The journey toward effective digital education in West Africa is complex and ongoing. However, as this study demonstrates, strong, visionary, and contextually responsive leadership is beneficial for navigating this path successfully and ensuring that the promise of digital technology translates into meaningful improvements in teaching and learning for all. Digital skills and leadership development in higher education are ongoing processes, as highlighted by studies focusing on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing need for digital transformation (Antonopoulou et al., 2020; Ayyaswamy, 2024).

5.1 Implications for policy and practice

The findings have several important implications for West Africa. Policymakers should invest in developing transformational leadership capacities that are culturally attuned, blending visionary change with the region’s inherent collaborative strengths (Kirkpatrick, 2024). Leaders should design PD programs that are participatory and practical, leveraging digital tools for cross-cultural and collaborative learning (Dong, 2024; Anwar and Saraih, 2024). Leaders must actively build networks with the government, NGOs, and the private sector to address systemic barriers, such as infrastructure, a practice vital for sustainable development (Grootaert and Narayan, 2004). Leadership must ensure that digital education initiatives and PD programs are explicitly designed to promote equity, training educators in inclusive digital pedagogies (Yende, 2023).

5.2 Limitations and future research

This study has limitations. The focus on Ghana may not capture the full diversity of West Africa. Reliance on self-reported data may be subject to bias. The comparison with China, while illustrative, involves different systemic scales. Future research could conduct longitudinal studies to track the long-term impact of leadership interventions, including direct measures of educator skills and student learning (Waight and Bruggeman, 2020), and expand to other West African countries. Exploring leadership in fully virtual or hybrid environments is also a critical next step (Chapelle, 2024). The journey toward effective digital education in West Africa is complex (Naik, 2000), but firm, visionary, and contextually responsive leadership is crucial for navigating this path successfully (Verma et al., 2024).

6 Conclusion

This study has provided compelling evidence of the profound impact of educational leadership on professional development in digital education in West Africa, primarily through an in-depth examination of the Ghanaian context, with comparative insights from China. The findings indicate that leadership is not peripheral but a central driving force in the successful design, implementation, and sustainability of PD programs that enhance educators’ digital competencies and foster equitable learning environments. Effective leadership in this domain, particularly transformational leadership, plays a crucial role in inspiring a shared vision for digital integration, motivating educators to embrace change, and providing the individualized support needed for skill development.

In the West African context, strategies that emphasize stakeholder collaboration, community engagement, and participatory decision-making are particularly effective, reflecting the region’s sociocultural dynamics (Jenkins, 2009). Leaders who actively address significant implementation barriers, such as inadequate infrastructure, funding constraints, and varying levels of digital literacy, by mobilizing resources, fostering innovation, and building resilient systems, make a tangible difference in the quality and reach of digital education. The measurable impact of targeted leadership interventions on enhancing educators’ digital pedagogical competence and confidence, as well as improving equitable access and learning outcomes for students, underscores the strategic importance of investing in leadership development. Specifically, leadership actions that prioritize mentoring, peer support, adequate resource allocation, and a focus on bridging the digital divide for students contribute significantly to positive outcomes.

While challenges remain, particularly systemic issues such as infrastructure and funding, this research demonstrates that proactive, visionary, and contextually attuned leadership can significantly mitigate these obstacles and unlock the transformative potential of digital education (Kurland and Berg, 2010). The comparative perspective with China highlighted both universal leadership principles and the importance of culturally responsive strategies. Ultimately, for West African nations to fully harness the benefits of the digital revolution in education, a concerted effort is needed to cultivate and support educational leaders who can champion change, foster innovation, and ensure that digital PD initiatives are effective, sustainable, and equitable. The evidence-based strategies identified in this study offer a pathway for policymakers, institutional heads, and PD coordinators to strengthen their leadership practices and, in doing so, empower educators and students in the digital age. The ongoing evolution of digital leadership in education necessitates continuous research and adaptation to ensure that leadership practices remain effective in the face of emerging technologies and shifting educational landscapes (Vavouras and Theodosiadis, 2024).

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ED: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. ZQ: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

A’mar, F., and Eleyan, D. (2021). Effect of principal’s technology leadership on teacher’s technology integration. Int. J. Instr. 15, 781–798. doi: 10.29333/iji.2022.15145a

Anderson, E., Nonterah, N., Tayviah, M., Agyeman, S., and Mahami, R. (2023). It seems the women are taking over: stereotyping around women in top-level leadership positions in Ghana's universities. Agenda 37, 74–88. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2023.2251814

Angwaomaodoko, E. (2023). A comparative study of education systems in Nigeria and other developing countries. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. doi: 10.24940/ijird/2023/v12/i11/nov23014

Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., and Beligiannis, G. (2020). Leadership types and digital leadership in higher education: behavioural data analysis from University of Patras in Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 19, 110–129. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.19.4.8

Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., and Beligiannis, G. (2021). Transformational leadership and digital skills in higher education institutes: during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 5, 1–15. doi: 10.28991/esj-2021-01252

Antonopoulou, H., Matzavinou, P., Γιαννούκου, Ι., and Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Teachers’ digital leadership and competencies in primary education: a cross-sectional behavioral study. Educ. Sci. 15:215. doi: 10.3390/educsci15020215

Anwar, S., and Saraih, U. (2024). Digital leadership in the digital era of education: enhancing knowledge sharing and emotional intelligence. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 38, 14–15. doi: 10.1108/ijem-11-2023-0540

Ayyaswamy, K. (2024). Enhancing digital technology planning, leadership, and management to transform education. Adv. Educ. Technol. Instruc. Design Book Ser. 1-9. doi: 10.4018/979-8-3693-5370-7.ch001

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1997). Shatter the glass ceiling: Women may make better managers. Leadership, 199–210. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198781820.003.0011

Brown, T., and Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Dev. Outreach 12, 29–43. doi: 10.1596/1020-797x_12_1_29

Carvalho, A., Alves, H., and Leitão, J. (2022). What research tells us about leadership styles, digital transformation and performance in state higher education? Int. J. Educ. Manag. 36, 218–232. doi: 10.1108/ijem-11-2020-0514

Chapelle, F. (2024). Traiter l’anxiété. Traiter l’anxiété, 110–148. doi: 10.3917/dunod.rusin.2024.01.0110

Dewey, C., Hingle, S., Goelz, E., and Linzer, M. (2020). Supporting clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, 752–753. doi: 10.7326/M20-1033,

Dong, T. V. (2024). Emotional management skills and training among high school administrators. The International Journal of Educational Organization and Leadership, 31, 27–44. doi: 10.18848/2329-1656/cgp/v31i02/27-44

Ghanney, R. (2024). Integrating 21st century skills into teaching of social studies among public junior high school learners in Effutu municipality. Int. J. Multidis. Res. 6, 13–17. doi: 10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i04.26441

Greenhow, P. (2020). A comparison of poor relief in Norfolk and Huntingdonshire. Local Population Studies, 104, 24–36. doi: 10.35488/lps104.2020.24

Grootaert, C., and Narayan, D. (2004). Local institutions, poverty and household welfare in Bolivia. World Development, 32, 1179–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.02.001

Jameson, J., Rumyantseva, N., Cai, M., Markowski, M., Essex, R., and McNay, I. (2022). A systematic review and framework for digital leadership research maturity in higher education. Comput. Educ. Open 3, 100115–100115. doi: 10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100115

Jenkins, K. (2009). Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama, 2009. Southern Spaces. doi: 10.18737/m7nk56

Karaköse, T., Polat, H., and Papadakis, S. (2021). Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13, 13448–13448. doi: 10.3390/su132313448

Karaköse, T., Polat, H., Tülübaş, T., and Demirkol, M. (2024). A review of the conceptual structure and evolution of digital leadership research in education. Educ. Sci. 14, 1166–1166. doi: 10.3390/educsci14111166

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., and Mastruzzi, M. (2009). “Governance matters VIII: aggregate and individual governance indicators across Pakistan 1996–2008” in World Bank policy research working paper. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-4978

Kier, H. (2022). Wolfram Hagspiel (1952–2021): Kunsthistoriker – Denkmalpfleger –wissenschaftler. Jahrbuch des Kölnischen Geschichtsvereins 85, 243–248. doi: 10.7788/9783412526320.243

Kouzes, J. M., and Posner, B. Z. (2012). Leadership practices inventory: Observer, 3rd edition. PsycTESTS Dataset. doi: 10.1037/t05491-000

Kratz, C. (2022). Continental collaboration: consulting, institution building, and mentoring across Africa. Afr. Arts 55, 68–73. doi: 10.1162/afar_a_00638.

Kurland, C. G., and Berg, O. G. (2010). A Hitchhiker’s guide to evolving networks. Evolutionary Genomics and Systems Biology, 361–396. doi: 10.1002/9780470570418.ch17

Laufer, M., Leiser, A., Deacon, B., Perrin de Brichambaut, P., Fecher, B., Kobsda, C., et al. (2021). Digital higher education: a divider or bridge builder? Leadership perspectives on edtech in a COVID-19 reality. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 18:51. doi: 10.1186/s41239-021-00287-6,

Niță, V., and Guțu, I. (2023). The role of leadership and digital transformation in higher education students' work engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20065124,

Nzarugarura, M., and Ndagijimana, J. (2025). Effects of head teachers' professional development programs on effective school leadership: a case of secondary schools in Rubavu district, Rwanda. Afr. J. Empir. Res. 6, 504–521. doi: 10.51867/ajernet.6.2.42

Perry, G., Arias, O., Fajnzylber, P., Maloney, W., Mason, A., and Saavedra-Chanduví, J. (2007). Informality. The World Bank eBooks. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-7092-6

Pittman, J., Severino, L., DeCarlo-Tecce, M., and Kiosoglous, C. (2021). An action research case study: digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent COVID-19 divide. J. Multicult. Educ. 15, 68–84. doi: 10.1108/jme-09-2020-0099

Richardson, J., and McLeod, S. (2011). Technology leadership in native American schools. Pennsylvania Libr. 26, 1–14. doi: 10.18113/p8jrre2607

Sidiki, Y., Gyamfi, S., Nikoi, S., and Buer, B. (2025). Impact of socio-economic factors on ICT adoption in basic schools in Wa municipality. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 24, 362–370. doi: 10.30574/gscarr.2025.24.1.0211

Thannimalai, R., and Raman, A. (2018). The influence of principals' technology leadership and professional development on teachers’ technology integration in secondary schools. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 15, 201–226. doi: 10.32890/mjli2018.15.1.8

Twining, P., Raffaghelli, J., Albion, P., and Knezek, D. (2013). Moving education into the digital age: the contribution of teachers' professional development. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 29, 426–437. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12031.

Ullah, K., Lill, I., and Witt, E. (2019). Land Ownership and Catastrophic Risk Management in Agriculture: The Case of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan.

Vavouras, E., and Theodosiadis, M. (2024). The concept of religion in Machiavelli: Political methodology, propaganda and ideological enlightenment. Religions, 15:1203. doi: 10.3390/rel15101203

Verma, S., Verma, S., Kumar, S., and Verma, B. (2024). Preface. Multidimensional Nanomaterials for Supercapacitors: Next Generation Energy Storage, i–ii. doi: 10.2174/9789815223408124010001

Waight III, K., and Bruggeman, D. (2020). Analysis of the frequency of extreme precipitation events at Los Alamos National Laboratory. doi: 10.2172/1618315

Wiederhold, B. K. (2020). Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: avoiding "zoom fatigue". Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 437–438. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.29188.bkw,

World Bank (1988). World development report 1988. World Bank Publications eBooks. doi: 10.1596/978-0-1952-0650-0

Yende, S. J. (2023). Emerging trends in South African higher education: A critical analysis of distance learning modalities in music. Progressio, 44. doi: 10.25159/2663-5895/15087

Keywords: digital education, educator training, leadership styles, professional development, West Africa

Citation: Darko ENKO, Qi Z and Wang Z (2026) Leadership and digital pedagogy: a cross-cultural analysis of professional development in Ghana and China. Front. Educ. 10:1744901. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1744901

Edited by:

Muhammad Waqas, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Fika Megawati, Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo, IndonesiaKhairul Syafuddin, Multimedia Nusantara University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2026 Darko, Qi and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiyuan Wang, emhpeXVhbndhbmdAc25udS5lZHUuY24=

Emmanuel Nana Kwesi Ofori Darko

Emmanuel Nana Kwesi Ofori Darko Zhanyong Qi

Zhanyong Qi Zhiyuan Wang

Zhiyuan Wang