- Department of Chemical Engineering, Ordos Institute of Technology, Ordos, China

To solve the global water shortages and serious water pollution problems, research on semiconductor photocatalysts has generated significant research attention. The degradation of pollutants by titanium dioxide (TiO2) exceeds other semiconductor materials. However, its wide bandgap restricts the photocatalytic reaction under visible light. The large specific surface area and good thermal conductivity of graphene yielded an effective graphene-TiO2 catalyst combination effective under visible light. 2D graphene-TiO2 composites (2D-GTC) have shown promise, so a study of the preparation methods, mechanism and catalytic effect of different pollutants on this material was undertaken. In this current review, the characteristics of different graphene and TiO2 composites and their preparation methods, as well as the effects of different synthesis methods on the catalyst are introduced. The reaction mechanism of 2D-GTC catalysts, the degradation effects of different pollutants in water are all reviewed.

Introduction

Water is necessary for life and overcoming water shortages represents one of the bigger challenges worldwide. Also, the discharge of various chemical substances of various concentrations into water by cities and some factories makes water conservation/purification even more important. In response to existing water resource needs, existing wastewater treatment technologies are booming. Common wastewater treatment methods include biological, membrane filtration, chemical precipitation and photocatalysis. Among them, the photocatalysis has advantages in environmental protection, low process cost, energy saving and easy control of the amount of catalyst used during wastewater treatment (Herrmann, 2010). However, there are some disadvantages coexist including difficulty in regenerating photocatalytic materials and lower efficacy in the presence of too many pollutants.

Various photocatalyst materials have been studied for their photocatalysis. Generally, photocatalysis utilizes the light absorption by the semiconductor as well as transitions of electrons from the lower to higher energy levels (electron-hole separation). In this process, carriers may recombine and result in inefficient catalysts. Long-life charge carriers and fewer charge trapping centers (abnormal centers of a physical location can “trap” charge carriers) are important factors for improving photochemical efficiency. ZnS, CdS, TiO2, g-C3N4 (graphite carbon nitride) or ZnO (Sudha and Sivakumar, 2015; Hao et al., 2017; Qi et al., 2017; Thirugnanam et al., 2017) are common photocatalyst materials. Among them, titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a well-known photocatalyst whose advantages include low cost, non-toxic and high photocatalytic activity (Kurniawan et al., 2012; Kuwahara et al., 2012). However, titanium dioxide has disadvantages as well, including a rapid recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and its low activity in the visible region (Bak et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2010), and low photocatalytic efficiency in the visible light region (Wang et al., 2007; Afzal et al., 2012; Kruth et al., 2014). These shortcomings degrades the quantum efficiency of TiO2 and limits wide application.

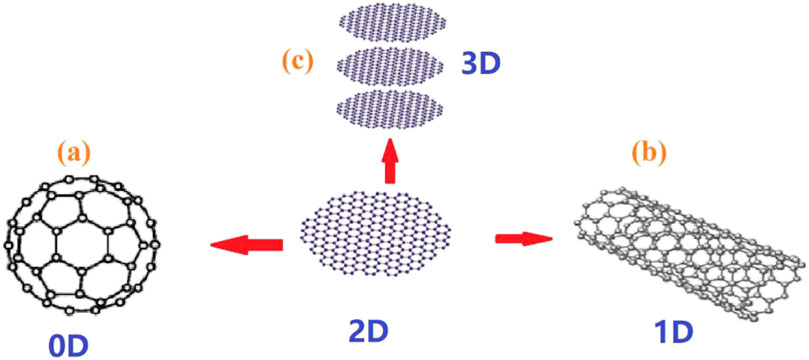

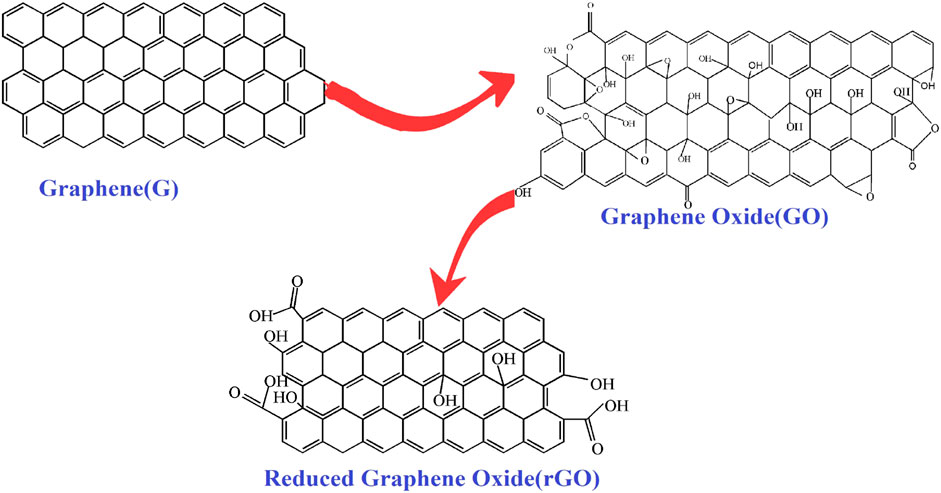

Many methods can be used to improve the photocatalytic performance of TiO2, such as doping precious metals (Ag, Pt, Au) and nonmetals (C, N, S), coupling ions with other semiconductors (ZnO, CdS, Bi2WO6), and loading TiO2 onto large surface area materials (mesoporous materials, zeolites and carbon-based materials) (Watanabe et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012b; Jose et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Sadanandam et al., 2013; Sivaranjani et al., 2014; Awate et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2016; He et al., 2013; Murugan et al., 2013). In 2004, graphene was discovered by Novoselov et al. (2004) and has attracted the attention of many research groups (Liang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018; Alamelu et al., 2018; Niu et al., 2018). It is a tightly wrapped honeycomb structure that contains sp2 hybridized carbon atoms and has been called a “miracle” material of the 21st century (Molina, 2016; Li et al., 2016; Mohan et al., 2018). Graphene can be converted into different carbon nanostructures, such as 0D C60 fullerene (Figure 1a), 1D carbon nanotube (Figure 1b) and 2D graphite flakes (Figure 1c) (Navalon et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2016). At the same time, after different chemical treatments, graphite can be converted into graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide (as seen in Figure 2).

The most outstanding feature of graphene is its huge specific surface area. In addition, graphene is only one atom thick, has good thermal conductivity (∼5000 W m−1 K−1) (Stoller et al., 2008), and high mechanical strength (1 TPa) (Balandin et al., 2008). It can also achieve ballistic transport (electron mobility at room temperature that exceeds 15,000 m2 V−1 s−1) without scattering (Kumar et al., 2017). These characteristics have allowed graphene to achieve outstanding advancements in the fields of photocatalysis and adsorption (Chakraborty et al., 2008). When graphene and TiO2 are doped to form 2D composite (2D Graphene-TiO2 Composite, which abbreviated as 2D-GTC in the description below), the appropriate energy level of TiO2 shifts, and electrons will convert the conduction band of TiO2 into the energy level of graphene, which ultimately leads to higher wastewater decomposition efficiency. The 2D-GTC not only enhances the adsorption of reactants in the visible range but also makes it easier to transfer and separate charges.

Synthesis of 2D-GTC

The current synthetic method for 2D-GTC includes the initial preparation of graphene oxide (GO), preparation of nano-TiO2 and followed by a combination with GO and nano-TiO2. Each step in the synthetic process uses different methods to generate different composites. Here is the method currently utilized most often, though other synthetic methods include chemical vapor deposition, hydrothermal method, and ultrasonic treatment were also be reported.

Preparation of Graphene Oxide (GO)

The GO is usually obtained by modifying graphene, and among them the choice of graphene is very important. As shown in Figure 3, graphene can be divided into single-layer graphene, few-layer graphene, and multi-layer graphene, according to the number of layers and thickness of graphene. A single-layer graphene is an ideal membrane structure, and the pore size can be adjusted with a porous distribution structure of atoms. The structure of few-layer graphene is smooth, neat, flat and defect-free, which can be stacked layer by layer for membrane separation experiments. Multi-layer graphene is usually stacked by single-layer graphene to form a film with a thickness of about 3–9 nm. After stacking, vivid nano-channels can be formed to penetrate gas and liquid. The sub-nano-level layer spacing in this tightly packed interlocking plate can be controlled to obtain the desired flux and separation selectivity. Graphene is usually obtained by mechanical peeling through block graphite (the "Scotch tape" method), chemical preparation and chemical vapor deposition (Schniepp et al., 2006; Stankovich et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Lomeda et al., 2008; Si and Samulski, 2008; Lotya et al., 2009; Behabtu et al., 2010).

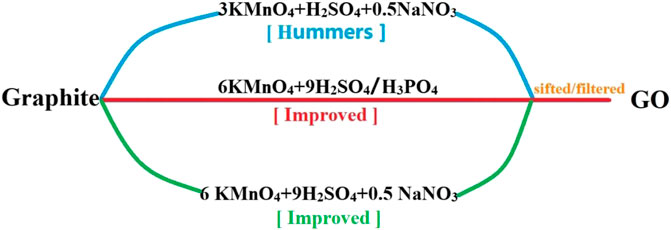

The synthesis of GO was first demonstrated in 1859 and involved the addition of potassium chlorate to a graphite slurry dissolved in fuming nitric acid (Brodie, 1859). In 1898, Staudenmaier (Staudenmaier, 1898) improved that method by dissolving graphite in concentrated sulfuric acid and fuming nitric acid, and adding chlorate several times during the reaction. Although this was only a minor improvement, it represented a more convenient and feasible way to make GO. The Hummers method, which is the most widely developed now, was published in 1958. The method oxidized graphite using KMnO4 and NaNO3 in concentrated H2SO4. However, this method also produces several gases (such as N2, N2O4, and Cl2), some of which are toxic. Due to this, many researchers sought to improve the Hummers methods (Marcano et al., 2010). The reaction equations of Hummers and two improved Hummers were shown in Figure 4. The two different improved Hummers method are safer than the original Hummers method due to the lack of heat and toxic gases released during the reaction and represents a significant synthetic step forward. The GO produced by the improved Hummers method oxidized more readily and did less damage to the graphite base surface.

Preparation of Nano-TiO2

TiO2 is an extensively studied photocatalyst. Due to different reaction processes for TiO2, the final form and photocatalytic effects are also different. Common forms include nano-sheets, nano-tubes, nano-spheres, nano-rods among other forms. After dissolving the raw materials in ethanol or deionized water, they are mixed by stirring or ultrasonic waves and placed in a polytetrafluoroethylene autoclave to react. The product is centrifuged (or suction filtered) and dried to obtain the titanium dioxide product. Nano TiO2 can be obtained by the method above, and the time and temperature in the reaction can be controlled to obtain different forms of titanium dioxide (Chen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020).

Different synthetic methods produce different TiO2 crystal structures and morphologies. TiO2 has three different crystal structures: rutile, anatase, and brookite. Among them, rutile TiO2 is the most stable, and other types readily convert to rutile TiO2 at high temperatures. Most of the TiO2 used to prepare 2D-GTC is anatase TiO2 or mixed crystals such as P25 (20% rutile phase and 80% anatase phase mixed). The heterojunction formed between different crystal phases facilitates the transfer of photogenerated electrons from one phase to another and reduces e-h+ recombination, which promotes the generation of free radical groups. The rutile phase is located at 27.1 ° of the {110} crystal plane, and the anatase phase is located at 24.2 ° of the {110} crystal plane. At low graphene levels during the synthesis of 2DGT, the 24.2 ° peak easily overlaps with the anatase peak (Rong et al., 2015).

Combination With GO and Nano-TiO2

The commonly used methods for combination with GO and nano-TiO2 to form 2D-GTC including stirring (or ultrasonic) mixing, sol-gel method and hydrothermal/solvothermal methods et al. (Mishra and Ramaprabhu, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012c). Different methods have an impact on the morphological characteristics and structure of the catalyst and influence the way that TiO2 adheres to the GO surface.

Stirring (or ultrasonic) mixing: Stirring (or ultrasonic) mixing is the simplest way to synthesize 2D-GTC which relies on van der Waals forces for bonding, so the interaction between the various components is very poor. In the reaction, GO (concentration: 0.01–10% by weight) is mixed with TiO2. Experimental results showed the addition of TiO2 altered the size of the GO colloid, which decreased accordingly (Park et al., 2011).

Sol-gel method: This method is another simple technique to prepare 2D-GTC; the 2D-GTC produced by sol-gel not only rely on van der Waals forces but also covalent oxygen bridges and hydroxyl bridges formed between GO and the metal center (Zhang et al., 2010).

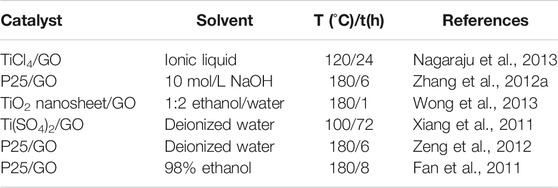

Hydrothermal/solvothermal methods: The primary benefit associated with hydrothermal/solvothermal syntheses comes from the synergistic effects of temperature, pressure, and solvent; this allows insoluble or poorly soluble substances to enter the solution in the form of complexes. Table 1 describes hydrothermal/solvothermal preparation methods for 2D-GTC and shows a variety of solvents, temperature, and times that be used. The temperature is between 100 and −180 °C and takes between 1 and −72 h. Regarding to the choice of raw materials, most differences come from titanium sources, which can usually come from TiO2 nanosheet, P25, titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) or titanium sulfate [Ti(SO4)2]. Alkaline solution, deionized water, ethanol and ionic liquid can all be used as solvents in 2D-GTC preparation. Compared with the conventional TiO2 catalyst, morphology and characteristics of the hydrothermal/solvothermal prepared 2D-GTC changed. Research show the agglomerate size of the particles decreases and the crystallites are more regular with a clearer shape. The concentration of -OH groups on the surface of hydrothermally prepared TiO2 is also about 33% higher than calcined TiO2 (Maira et al., 2001).

Degradation Effect of 2D-GTC on Different Water Pollutants

Degradation of Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used frequently because they can be used for more than just human treatment. However, overuse of antibiotics can contaminate desoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and lead to bacterial resistance in an organism (Wang et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2018). Many countries have explicit regulations on the use and residual levels of antibiotics. The limits of tetracycline antibiotics in China and the EU specify the content of edible animal muscle tissue should contain less than 100 μg kg−1. The United States has set clear chlortetracycline limits in animal muscle tissue at 200 μg kg−1. However, antibiotic levels in current water bodies are not within the range of water quality indicators. Antibiotics themselves are extremely durable, difficult to degrade, and often discharged in the original form from the human body (Xu et al., 2019). Therefore, the removal of antibiotics in wastewater has become a problem we must solve.

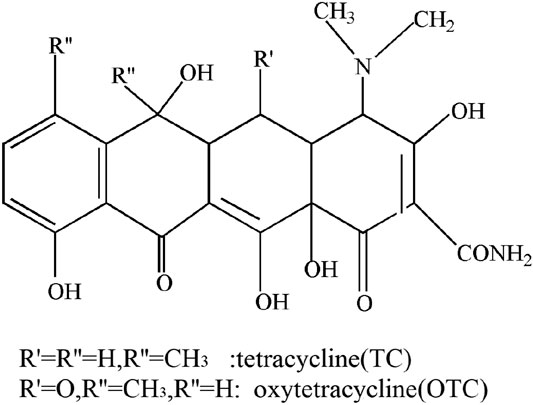

Tetracyclines (TCs) are a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics produced by actinomycetes, including tetracycline (TC), tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH), chlortetracycline (CTC) and oxytetracycline (OTC) etc. The structure of tetracycline antibiotics all contain naphthophenyl skeleton (Figure 5). Li et al. (2017) obtained a TiO2-rGO-TiO2 photocatalyst by a sol-gel method to degrade, and found under the same degradation conditions, the degradation efficiency of TCH increased by 22.8% using ultraviolet light and 32.8% under simulated sunlight than a pure TiO2 catalyst. The two main factors that promote the photocatalytic reaction are the number of pores and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the addition of GO reduces the band gap energy of TiO2. Li et al. (2017) also used TiO2 particles compounded on the surface of GO sheet to form a 2D-GTC catalyst and applied it to remove chlortetracycline (CTC) from water. Those results showed that the removal efficiency of 2D-GTC (10 mg/L) on CTC in real sewage approached 100%. Wang et al. (2019) also reported the removal rate of oxytetracycline (OTC) by hydrothermal synthesised 2D-GTC nearly reached 100% under visible light, and found during the photocatalytic reaction, h+/e− pairs are generated and the appearance of h+ is determined to be the main reason for OTC removal.

Degradation of Other Organic Pollutants

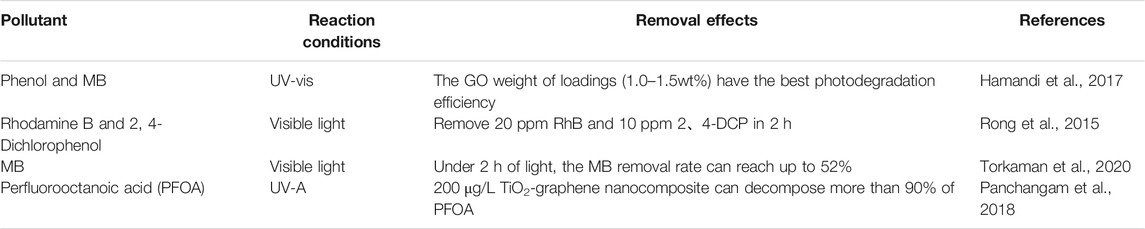

Table 2 summarizes the removal effect of 2D-GTC on other organic pollutants like phenol, Methylene blue (MB), 2, 4-Dichlorophenol and perfluorooctanoic acid. Under different light conditions (UV-Vis/visible light), 2D-GTC has different removal effects on organic pollutants. The time to reach the best removal effect, the content of 2D-GTC, and the final removal rate are all different. Pollutant removal effects by 2D-GTC is as follows: addition of GO reduces the band gap energy of TiO2 and generates voids during photocatalysis. The hole/electron (h+/e−) serves as the primary reactant for TiO2 catalysts.

Photocatalytic Mechanism and Influencing Factors of 2D-GTC

Photocatalytic Reaction Influencing Factors of 2D-GTC

GO is a structural material with an aliphatic sp3 carbon structure, an aromatic sp2 structure and contains an oxygen intercalation group. Some studies have conducted theoretical calculations and model studies and found that GO can fix gases (even gases as small as helium) because the gap in its aromatic ring is blocked by the π orbital cloud (Bunch et al., 2008). One simulation found that single-layer GO has a high salt removal rate, approximately two to three orders of magnitude higher than other permeable membranes (Cohen-Tanugi and Grossman, 2014), and its water flux can reach 400–4,000 m2 h−1 bar−1. Moreover, single-layer GO is selective to certain pollutants (O’Hern et al., 2014). The GO structure has sp3 hybridized carbon atoms and a topological network, so it is easy to wrinkle and obtain corrugated nanosheets. These GO films also have outstanding adsorption capacity because the oxidized area of GO can divide the next layer, and its non-oxidized area allows a liquid material to flow without friction. Nano multilayer GO nanosheets are highly compatible, whose uneven structure improves the mobility and contact efficiency of the reactants, and have unique permeability and unique molecular transmission characteristics (Wakabayashi et al., 2008; Han et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2015). In addition, the nano-layered GO has the ability to transport water, oil or oil/water mixture at the same time.

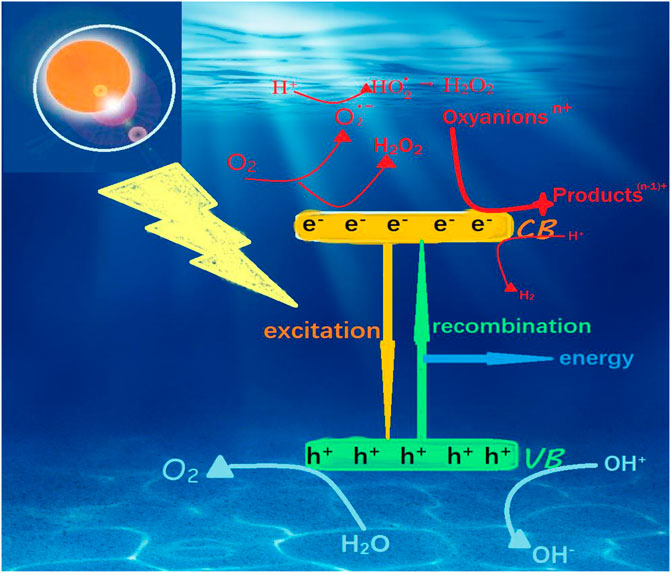

Although the GO has so many characteristic advantages, it does not have a photocatalytic effect by itself. It is still TiO2 that plays a photocatalytic role in 2D-GTC. When the energy captured by TiO2 exceeds the photon of its band gap (anatase: ∼3.2 eV or rutile: ∼3.0 eV), the photoelectron e–is excited to the conduction band (CB) and is in the valence band (VB) and holes are left on the top, resulting in electron-hole pairs (Di Valentin et al., 2004). Figure 6 details the reaction of TiO2 during photocatalysis to generate reactive oxygen species (ROSs). Holes in the VB oxidize the adsorbed water or OH− groups to produce hydroxyl groups (OH) while CB electrons reduce O2 molecules. Producing superoxide (O2-) (2.5, 2.6). O2- can generate hydroperoxy radicals (

Equation of TiO2 during photocatalysis:

Photoexcitation: TiO2 + hv → e- + h+ (2.1)

(n-1) + Chare − carrier trapping of e−:

Chare–carrier trapping of h+:

Electron–hole recombination:

Oxidation of hydroxyls: OH- + h+ → OH (2.5)

Photoexcitation of e− scavenging:

Photoexcitation of superoxide:

Co–scavenging of e−:

Formation of H2O2:

or O2+2H++2e-→ H2O2 (2.10)

Water splitting: 2H++2e-→ H2 (2.11)

and 2H2O+4h+→ 4H++O2 (2.12)

The combination of GO and TiO2 promotes their respective advantages, so that 2D-GTC becomes a photocatalyst with great application potential. Studies have shown that, under visible light, TiO2 transfers photogenerated electrons to GO and simultaneously transfers holes from GO to TiO2, which causes adsorbate oxidization. Pollutants adsorb onto the TiO2 surface (Wang et al., 2012a), the delayed recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs allows organic pollutants to undergo redox reactions with more h+ (Geng et al., 2013). Active oxygen appears when photogenerated electron-hole pairs form. Radical O2- anions, hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and h+ in these reactive oxygen species (ROSs) react with organic pollutants to cause mineralization (Chen and Liu, 2017; Reshak, 2018).

Photocatalytic Reaction Influencing Factors of 2D-GTC

Many factors affect the photocatalysis of titanium dioxide and graphene composites, such as the mass ratio of graphene to titanium dioxide, pH, and light intensity. During photocatalysis, the primary photocatalytic material is titanium dioxide, and the addition of GO increases the number of pores. The degradation efficiency of pollutants initially increases but decreases with an increasing weight percentage of GO (Zhou et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012b), because the addition of GO can guide nucleation of TiO2. At the same time, carrier recombination decreases and TiO2 crystals are evenly distributed. The introduction of pores leads to an attraction between the photocatalyst and the adsorbent. As the weight ratio of GO increases, the relative levels of TiO2 decrease which lowers carriers induced by photocatalysis as well as the photocatalytic reaction sites of TiO2. Also, high levels of TiO2 crystals cause agglomeration and reduce the number of catalytic sites. To combat this, the catalyst can be used multiple times by washing or high-temperature combustion (Wang et al., 2012a). Alteration of pH levels also led to different degradation effects. For some antibiotics, a higher pH initially increased the degradation effect though it subsequently decreased. The degradation effect maximized at a pH of 7 (for some antibiotics).

Conclusion

Graphene and TiO2 can form composites through a variety of different composite methods, and a variety of pollutants, such as dyes, antibiotics can be removed through photocatalytic reactions by 2D-GTC. TiO2 is a good semiconductor with multiple catalytic sites. Compounding GO and TiO2 produces a large number of pores that provide space for adsorption so that liquid contaminants can diffuse onto the interface, which further increases degradation. Therefore, the addition of GO increases the photocatalytic active sites of titanium dioxide. In addition to the mass ratio of GO, the pH and the form of different materials also play vital roles in the catalytic effect. 2D-GTC materials not only treat water pollutants under ultraviolet light but also perform photocatalytic reactions under sunlight.

Although a long time has passed since the discovery of 2D-GTC materials as photocatalysts, and its charge carrier transport, photo-generated electrons and photocatalytic properties are remarkable. But in its normal form it can theoretically stretch indefinitely across its width. In order to make the 2D-GTC material a practical engineering material, there are still challenges in improving the efficiency of photocatalysis and the cost of catalyst preparation, so there is still a lot of work to be done in the further.

Author Contributions

XZ, The manuscript writing; XZ, The second author, The mechanism of reactions and manuscript review; YW, The third author, Document collection and sorting; ZW, The Corresponding author, The management and manuscript conduction.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the financial supports from the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2019MS02029), the Scientific Research Project of Inner Mongolia for colleges and universities (NJZY19259), and the Postdoctoral Research Funding Project of Ordos.

References

Afzal, S., Daoud, W. A., and Langford, S. J. (2012). Self-cleaning cotton by porphyrin-sensitized visible-light photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. 22 (9), 4083–4088. doi:10.1039/c2jm15146d

Alamelu, K., Raja, V., Shiamala, L., Ali, B. M., and Jaffar, (2018). Biphasic TiO2 nanoparticles decorated graphene nanosheets for visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 430, 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.05.054

Awate, S. V., Deshpande, S. S., Rakesh, K., Dhanasekaran, P., and Gupta, N. M. (2011). Role of micro-structure and interfacial properties in the higher photocatalytic activity of TiO2-supported nanogold for methanol-assisted visible-light-induced splitting of water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13 (23), 11329–11339. doi:10.1039/c1cp21194c

Bak, T., Nowotny, J., Rekas, M., and Sorrellet, C. C. (2002). Photo-electrochemical hydrogen generation from water using solar energy. Materials-related aspects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (10), 991–1022. doi:10.1016/s0360-3199(02)00022-8

Balandin, A. A., Ghosh, S., Bao, W., Calizo, I., Teweldebrhan, D., Miao, F., et al. (2008). Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8 (3), 902–907. doi:10.1021/nl0731872

Behabtu, N., Lomeda, J. R., Green, M. J., Higginbotham, A. L., Sinitskii, A., Kosynkin, D. V., et al. (2010). Spontaneous high-concentration dispersions and liquid crystals of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5 (6), 406–411. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.86

Brodie, B. C. (1859). XIII. On the atomic weight of graphite. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. 149, 249–259. doi:10.1098/rstl.1859.0013

Bunch, J. S., Verbridge, S. S., Alden, J. S., van der Zande, A. M., Parpia, J. M., Craighead, H. G., et al. (2008). Impermeable atomic membranes from graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 8 (8), 2458–2462. doi:10.1021/nl801457b

Chakraborty, S., Guo, W., Hauge, R. H., and Billups, W. E. (2008). Reductive alkylation of fluorinated graphite. Chem. Mater. 20 (9), 3134–3136. doi:10.1021/cm800060q

Chang, P. H., Juhrend, B., Olson, T. M., Marrs, C. F., and Wigginton, K. R. (2017). Degradation of extracellular antibiotic resistance genes with UV254 treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (11), 6185–6192. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b01120

Chen, L., Yang, S., Mu, L., and Ma, P. C. (2018). Three-dimensional titanium dioxide/graphene hybrids with improved performance for photocatalysis and energy storage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 512, 647–656. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2017.10.103

Chen, Y., and Liu, K. (2017). Fabrication of Ce/N co-doped TiO2/diatomite granule catalyst and its improved visible-light-driven photoactivity. J. Hazard Mater. 324, 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.10.043

Chong, M. N., Jin, B., Chow, C. W. K., and Saint, C. (2010). Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: a review. Water Research 44 (10), 2997–3027. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.02.039

Cohen-Tanugi, D., and Grossman, J. C. (2014). Mechanical strength of nanoporous graphene as a desalination membrane. Nano Lett. 14 (11), 6171–6178. doi:10.1021/nl502399y

Di Valentin, C., Pacchioni, G., and Selloni, A. (2004). Origin of the different photoactivity of N-doped anatase and rutile TiO2. Phys. Rev. B 70 (8), 085116. doi:10.1103/physrevb.70.085116

Fan, W., Lai, Q., Zhang, Q., and Wang, Y. (2011). Nanocomposites of TiO2 and reduced graphene oxide as efficient photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C 115 (21), 10694–10701. doi:10.1021/jp2008804

Geng, W., Liu, H., and Yao, X. (2013). Enhanced photocatalytic properties of titania-graphene nanocomposites: a density functional theory study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (16), 6025–6033. doi:10.1039/c3cp43720e

Gupta, B., Melvin, A. A., Matthews, T., Dash, S., and Tyagi, A. K. (2016). TiO2 modification by gold (Au) for photocatalytic hydrogen (H2) production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 58, 1366–1375. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.236

Hamandi, M., Berhault, G., Guillard, C., and Kochkar, H. (2017). Reduced graphene oxide/TiO2 nanotube composites for formic acid photodegradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 209, 203–213. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.02.062

Han, Y., Xu, Z., and Gao, C. (2013). Ultrathin graphene nanofiltration membrane for water purification. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23 (29), 3693–3700. doi:10.1002/adfm.201202601

Hao, Q., Hao, S., Niu, X., Li, X., Chen, D., and Ding, H. (2017). Enhanced photochemical oxidation ability of carbon nitride by π–π stacking interactions with graphene. Chin. J. Catal. 38 (2), 278–286. doi:10.1016/s1872-2067(16)62561-5

He, Y., Zhang, Y., Huang, H., and Zhang, R. (2013). Synthesis of titanium dioxide-reduced graphite oxide nanocomposites and their photocatalytic performance. Micro & Nano Lett. 8 (9), 483–486. doi:10.1049/mnl.2013.0182

Herrmann, J. M. (2010). Photocatalysis fundamentals revisited to avoid several misconceptions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 99 (3-4), 461–468. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.05.012

Hou, Z., Chen, F., Wang, J., François-Xavier, C. P., and Wintgens, T. (2018). Novel Pd/GdCrO3 composite for photo-catalytic reduction of nitrate to N2 with high selectivity and activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 232, 124–134. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.03.055

Ji, Q., Yu, D., Zhang, G., Lan, H., Liu, H., and Qu, J. (2015). Microfluidic flow through polyaniline supported by lamellar-structured graphene for mass-transfer-enhanced electrocatalytic reduction of hexavalent chromium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (22), 13534–13541. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b03314

Jiang, D., Li, Y., Wu, Y., Zhou, P., Lan, Y., and Zhou, L. (2012). Photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) by small molecular weight organic acids over schwertmannite. Chemosphere 89 (7), 832–837. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.001

Jose, D., Sorensen, C. M., Rayalu, S. S., Shrestha, K. M., and Klabunde, K. J. (2013). Au-TiO2 nanocomposites and efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under UV-visible and visible light illuminations: a comparison of different crystalline forms of TiO2. Int. J. PhotoEnergy 2013, 30. doi:10.1155/2013/685614

Krishna Kumar, R., Chen, X., Auton, G. H., Mishchenko, A., Bandurin, D. A., Morozov, S. V., et al. (2017). High-temperature quantum oscillations caused by recurring Bloch states in graphene superlattices. Science 357 (6347), 181–184. doi:10.1126/science.aal3357

Kruth, A., Peglow, S., Rockstroh, N., Junge, H., Brüser, V., and Weltmann, K. D. (2014). Enhancement of photocatalyic activity of dye sensitised anatase layers by application of a plasma-polymerized allylamine encapsulation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 290, 31–37. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2014.06.005

Kurniawan, T. A., Sillanpää, M. E. T., and Sillanpää, M. (2012). Nanoadsorbents for remediation of aquatic environment: local and practical solutions for global water pollution problems. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (12), 1233–1295. doi:10.1080/10643389.2011.556553

Kuwahara, Y., Aoyama, J., Miyakubo, K., and Taro, (2012). TiO2 photocatalyst for degradation of organic compounds in water and air supported on highly hydrophobic FAU zeolite: structural, sorptive, and photocatalytic studies. J. Catal. 285 (1), 223–234. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2011.09.031

Li, D., Müller, M. B., Gilje, S., Kaner, R. B., and Wallace, G. G. (2008). Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3 (2), 101–105. doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.451

Li, D., Sun, J., Shen, T., Song, H., Liu, L., Wang, C., et al. (2020). Influence of morphology and interfacial interaction of TiO2-Graphene nanocomposites on the visible light photocatalytic performance. J. Solid State Chem. 286, 121301. doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2020.121301

Li, X., Shen, R., Ma, S., Chen, X., and Xie, J. (2018). Graphene-based heterojunction photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 430, 53–107. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.194

Li, X., Yu, J., and Jaroniec, M. (2016). Hierarchical photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (9), 2603–2636. doi:10.1039/c5cs00838g

Li, Z., Qi, M., Tu, C., Wang, W., Chen, J., and Wang, A. J. (2017). Highly efficient removal of chlorotetracycline from aqueous solution using graphene oxide/TiO2 composite: properties and mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. 425, 765–775. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.07.027

Liang, D., Cui, C., Hu, H., Wang, Y., and Shen, H. (2014). One-step hydrothermal synthesis of anatase TiO2/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 582, 236–240. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.08.062

Liu, G., Wang, L., Yang, H. G., Cheng, H. M., and Lu, G. Q. (2010). Titania-based photocatalysts-crystal growth, doping and heterostructuring. J. Mater. Chem. 20 (5), 831–843. doi:10.1039/b909930a

Lomeda, J. R., Doyle, C. D., Kosynkin, D. V., Hwang, W. F., and Tour, J. M. (2008). Diazonium functionalization of surfactant-wrapped chemically converted graphene sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (48), 16201–16206. doi:10.1021/ja806499w

Lotya, M., Hernandez, Y., King, P. J., Smith, R. J., Nicolosi, V., Karlsson, L. S., et al. (2009). Liquid phase production of graphene by exfoliation of graphite in surfactant/water solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (10), 3611–3620. doi:10.1021/ja807449u

Maira, A. J., Coronado, J. M., Augugliaro, V., Yeung, K. L., Conesa, J. C., and Soria, J. (2001). Fourier transform infrared study of the performance of nanostructured TiO2 particles for the photocatalytic oxidation of gaseous toluene. J. Catal. 202 (2), 413–420. doi:10.1006/jcat.2001.3301

Marcano, D. C., Kosynkin, D. V., Berlin, J. M., Sinitskii, A., Sun, Z., Slesarev, A., et al. (2010). Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 4 (8), 4806–4814. doi:10.1021/nn1006368

Marinho, B. A., Djellabi, R., Cristóvão, R. O., Loureiro, J. M., and Vilar, V. J. P. (2017). Intensification of heterogeneous TiO2 photocatalysis using an innovative micro-meso-structured-reactor for Cr (VI) reduction under simulated solar light. Chem. Eng. J. 318, 76–88. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2016.05.077

Mishra, A. K., and Ramaprabhu, S. (2011). Functionalized graphene-based nanocomposites for supercapacitor application. J. Phys. Chem. C 115 (29), 14006–14013. doi:10.1021/jp201673e

Mohan, V. B., Lau, K., Hui, D., and Bhattacharyya, D. (2018). Graphene-based materials and their composites: a review on production, applications and product limitations. Compos. B Eng. 142, 200–220. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.01.013

Molina, J. (2016). Graphene-based fabrics and their applications: a review. RSC Adv. 6 (72), 68261–68291. doi:10.1039/c6ra12365a

Murugan, R., Babu, V. J., Khin, M. M., et al. (2013). Synthesis and photocatalytic applications of flower shaped electrospun ZnO–TiO2 mesostructures. Mater. Lett. 97, 47–51. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2013.01.072

Nagaraju, G., Ebeling, G., Gonçalves, R. V., Teixeira, S. R., Weibel, D. E., and Dupont, J. (2013). Controlled growth of TiO2 and TiO2–RGO composite nanoparticles in ionic liquids for enhanced photocatalytic H2 generation. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 378, 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2013.06.010

Navalon, S., Dhakshinamoorthy, A., Alvaro, M., and Garcia, H. (2014). Carbocatalysis by graphene-based materials. Chem. Rev. 114 (12), 6179–6212. doi:10.1021/cr4007347

Niu, X., Yan, W., Zhao, H., and Yang, J. (2018). Synthesis of Nb doped TiO2 nanotube/reduced graphene oxide heterostructure photocatalyst with high visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 440, 804–813. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.01.069

Novoselov, K. S., Geim, A. K., Morozov, S. V., Jiang, D., Zhang, Y., Dubonos, S. V., et al. (2004). Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306 (5696), 666–669. doi:10.1126/science.1102896

O'Hern, S. C., Boutilier, M. S., Idrobo, J. C., Song, Y., Kong, J., Laoui, T., et al. (2014). Selective ionic transport through tunable subnanometer pores in single-layer graphene membranes. Nano Lett. 14 (3), 1234–1241. doi:10.1021/nl404118f

Panchangam, S. C., Yellatur, C. S., Yang, J. S., and Sarma, S. (2018). Facile fabrication of TiO2-graphene nanocomposites (TGNCs) for the efficient photocatalytic oxidation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 6 (5), 6359–6369. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.10.003

Park, Y., Kang, S. H., and Choi, W. (2011). Exfoliated and reorganized graphite oxide on titania nanoparticles as an auxiliary co-catalyst for photocatalytic solar conversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13 (20), 9425–9431. doi:10.1039/c1cp20697d

Qi, K., Cheng, B., Yu, J., and Ho, W. (2017). A review on TiO2-based Z-scheme photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 38 (12), 1936–1955. doi:10.1016/s1872-2067(17)62962-0

Reshak, A. H. (2018). Active photocatalytic water splitting solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion: chalcogenide photocatalyst Ba2ZnSe3 under visible irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 221, 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.09.018

Rong, X., Qiu, F., Zhang, C., Fu, L., Wang, Y., and Yang, D. (2015). Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic application of TiO2-graphene photocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Ceram. Int. 41 (2), 2502–2511. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.10.072

Sadanandam, G., Lalitha, K., Kumari, V. D., Shankar, M. V., and Subrahmanyam, M. (2013). Cobalt doped TiO2: a stable and efficient photocatalyst for continuous hydrogen production from glycerol: water mixtures under solar light irradiation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 38 (23), 9655–9664. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.05.116

Schniepp, H. C., Li, J. L., Mcallister, M. J., Sai, H., Herrera-Alonso, M., Adamson, D. H., et al. (2006). Functionalized single graphene sheets derived from splitting graphite oxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 110 (17), 8535–8539. doi:10.1021/jp060936f

Si, Y., and Samulski, E. T. (2008). Synthesis of water soluble graphene. Nano Lett. 8 (6), 1679–1682. doi:10.1021/nl080604h

Sivaranjani, K., RajaAmbal, S., Das, T., Roy, K., Bhattacharyya, S., and Gopinath, C. S. (2014). Disordered mesoporous TiO2-xNx+ nano-Au: an electronically integrated nanocomposite for solar H2 generation. ChemCatChem 6 (2), 522–530. doi:10.1002/cctc.201300715

Stankovich, S., Dikin, D. A., Piner, R. D., and Kevin, A. (2007). Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 45 (7), 1558–1565. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2007.02.034

Staudenmaier, L. (1898). Verfahren zur darstellung der graphitsäure. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 31 (2), 1481–1487. doi:10.1002/cber.18980310237

Stoller, M. D., Park, S., Zhu, Y., An, J., and Ruoff, R. S. (2008). Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 8 (10), 3498–3502. doi:10.1021/nl802558y

Sudha, D., and Sivakumar, P. (2015). Review on the photocatalytic activity of various composite catalysts. Chem. Eng. Process: Process Intensification 97, 112–133. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2015.08.006

Thirugnanam, N., Song, H., and Wu, Y. (2017). Photocatalytic degradation of Brilliant Green dye using CdSe quantum dots hybridized with graphene oxide under sunlight irradiation. Chin. J. Catal. 38 (12), 2150–2159. doi:10.1016/s1872-2067(17)62964-4

Torkaman, M., Rasuli, R., and Taran, L. (2020). Photovoltaic and photocatalytic performance of anchored oxygen-deficient TiO2 nanoparticles on graphene oxide. Results in Physics 18, 103229. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103229

Wakabayashi, K., Pierre, C., Dikin, D. A., and Ruoff, R. S. (2008). Polymer-graphite nanocomposites: effective dispersion and major property enhancement via solid-state shear pulverization. Macromolecules 41 (6), 1905–1908. doi:10.1021/ma071687b

Wang, C., Hu, Q., Huang, J., et al. (2013). Efficient hydrogen production by photocatalytic water splitting using N-doped TiO2 film[J]. Applied surface science, 283: 188–192.

Wang, C., Li, J., Mele, G., Yang, G. M., Zhang, F. X., Palmisano, L., et al. (2007). Efficient degradation of 4-nitrophenol by using functionalized porphyrin-TiO2 photocatalysts under visible irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 76 (3-4), 218–226. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.05.028

Wang, W. S., Wang, D. H., Qu, W. G., Lu, L. Q., and Xu, A. W. (2012a). Large ultrathin anatase TiO2 nanosheets with exposed {001} facets on graphene for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (37), 19893–19901. doi:10.1021/jp306498b

Wang, X., Tian, H., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, S., Zheng, W., et al. (2012b). Reduced graphene oxide/CdS for efficiently photocatalystic degradation of methylene blue. J. Alloys Compd. 524, 5–12. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.02.058

Wang, H., Wang, N., Wang, B., Fang, H., Fu, C., Tang, C., et al. (2016). Antibiotics detected in urines and adipogenesis in school children. Environ. Int. 89-90, 204–211. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.005

Wang, H., Zhang, M., He, X., Du, T., Wang, Y., Li, Y., et al. (2019). Facile prepared ball-like TiO2 at GO composites for oxytetracycline removal under solar and visible lights. Water Research 160, 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.073

Watanabe, M., Hagiwara, H., Iribe, A., Ogata, Y., Shiomi, K., Staykov, A., et al. (2014). Spacer effects in metal-free organic dyes for visible-light-driven dye-sensitized photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. 2 (32), 12952–12961. doi:10.1039/c4ta02720e

Wong, T. J., Lim, F. J., Gao, M., et al. (2013). Photocatalytic H2 production of composite one-dimensional TiO2 nanostructures of different morphological structures and crystal phases with graphene. Catalysis Science & Technology 3 (4), 1086–1093. doi:10.1039/c2cy20740k

Xiang, Q., Yu, J., and Jaroniec, M. (2011). Enhanced photocatalytic H₂-production activity of graphene-modified titania nanosheets. Nanoscale 3 (9), 3670–3678. doi:10.1039/c1nr10610d

Xu, D., Xiao, Y., Pan, H., and Mei, Y. (2019). Toxic effects of tetracycline and its degradation products on freshwater green algae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 174, 43–47. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.063

Xu, Y., Bai, H., Lu, G., Li, C., and Shi, G. (2008). Flexible graphene films via the filtration of water-soluble noncovalent functionalized graphene sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (18), 5856–5857. doi:10.1021/ja800745y

Yu, F., Li, Y., Han, S., and Ma, J. (2016). Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from aqueous solution using carbon materials. Chemosphere 153, 365–385. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.083

Zeng, P., Zhang, Q., Zhang, X., and Zhang, T. (2012). Graphite oxide-TiO2 nanocomposite and its efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Alloys Compd. 516, 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.11.140

Zhang, N., Zhang, Y., and Xu, Y. J. (2012a). Recent progress on graphene-based photocatalysts: current status and future perspectives. Nanoscale 4 (19), 5792–5813. doi:10.1039/c2nr31480k

Zhang, X., Sun, Y., Cui, X., and Jiang, Z. Y. (2012b). A green and facile synthesis of TiO2/graphene nanocomposites and their photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37 (1), 811–815. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.04.053

Zhang, X., Veikko, U., Mao, J., Cai, P., and Peng, T. (2012c). Visible-light-induced photocatalytic hydrogen production over binuclear Ru(II)-bipyridyl dye-sensitized TiO2 without noble metal loading. Chemistry 18 (38), 12103–12111. doi:10.1002/chem.201200725

Zhang, X. Y., Li, H. P., Cui, X. L., and Lin, Y. (2010). Graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites: synthesis, characterization and application in hydrogen evolution from water photocatalytic splitting. J. Mater. Chem. 20 (14), 2801–2806. doi:10.1039/b917240h

Zheng, L., Zhang, J., Hu, Y. H., and Long, M. (2019). Enhanced photocatalytic production of H2O2 by nafion coatings on S, N-codoped graphene-quantum-dots-modified TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 123 (22), 13693–13701. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b02311

Zheng, Y., Liu, W., Qin, Z., Chen, Y., Jiang, H., and Wang, X. (2018). Mercaptopyrimidine-conjugated gold nanoclusters as nanoantibiotics for combating multidrug-resistant superbugs. Bioconjugate Chem. 29 (9), 3094–3103. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00452

Zhou, K., Zhu, Y., Yang, X., Xin, J., and Li, C. (2011). Preparation of graphene–TiO2 composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. New J. Chem. 35 (2), 353–359. doi:10.1039/c0nj00623h

Keywords: photocatalysis, 2D graphene, titanium dioxide, water pollutants, nanocomposites

Citation: Zhou X, Zhang X, Wang Y and Wu Z (2021) 2D Graphene-TiO2 Composite and Its Photocatalytic Application in Water Pollutants. Front. Energy Res. 8:612512. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2020.612512

Received: 30 September 2020; Accepted: 21 December 2020;

Published: 02 February 2021.

Edited by:

Fenglong Wang, Shandong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Dongshuang Wu, Kyoto University, JapanZhaoke Zheng, Shandong University, China

Lin Jing, Beijing University of Technology, China

Zhou Wang, Shandong University, China

Copyright © 2021 Zhou, Zhang, Wang and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhen Wu, d3U5XzlAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Xin Zhou

Xin Zhou Zhen Wu

Zhen Wu