- 1School of Public Administration, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, China

- 2School of Economics and Management of China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, China

Heterogeneous environmental regulation provides dynamic incentives for green innovation through diversity and complementarity, and promotes technological breakthroughs and market responses. Based on the panel data of 30 provinces in China from 2010 to 2020, this paper constructs a bi-directional fixed-effect model to examine the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulation and green innovation and the moderating effect of common prosperity. The empirical results show that: (1) there is a significant U-shaped relationship between command-control and public participation environmental regulation and green innovation, while there is a significant inverse U-shaped relationship between market incentive environmental regulation and green innovation; (2) Common prosperity has a significant promoting effect on green innovation, and positively regulates the U-shaped relationship between command and control, public participation environmental regulation and green innovation, and negatively regulates the inverted U-shaped relationship between market incentive environmental regulation and green innovation; (3) There are obvious regional differences in the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulation, common prosperity and green innovation. Therefore, the government should implement differentiated environmental regulation policies, optimize the incentive mechanism for green innovation according to local conditions, build a multi-level environmental governance system, and strengthen the regulatory role of common prosperity to promote the balanced development of green innovation.

1 Introduction

With the intensification of global climate change and environmental problems, environmental regulation has gradually become an important means for governments to deal with environmental crises (Wu D. D. et al., 2020). Environmental regulation means that the government regulates and constrains the environmental behaviors of enterprises and individuals through legislation, administrative means or other means in order to achieve the goals of environmental protection and sustainable development (Wang et al., 2022). Traditional environmental regulation is mainly command-and-control, that is, through mandatory regulations, standards and fines, forcing enterprises and individuals to reduce pollution emissions.

However, with the complexity of environmental problems and the deepening of economic globalization, the limitations of command-and-control environmental regulations have gradually emerged (Dogan et al., 2022). On the one hand, command-and-control regulation may cause enterprises to over-rely on the government’s coercive means and lack autonomy and innovation. On the other hand, over-reliance on government intervention may inhibit market vitality and undermine the long-term development of green technology innovation (Khan et al., 2021). In order to make up for the deficiency of command-control regulation, market incentive environmental regulation has been paid more and more attention. Market-incentivized environmental regulation guides the environmental behaviors of enterprises and individuals through economic means (such as taxation, subsidies, emission trading, etc.) to stimulate market vitality and innovation potential (Yang and Tang, 2023). For example, through the implementation of carbon tax or carbon emission trading system, enterprises can not only reduce pollution emissions through technological innovation, but also obtain economic benefits in the market, so as to achieve a win-win situation of environmental benefits and economic benefits. However, the effects of market-based environmental regulations are also influenced by the degree of perfection of market mechanisms, the rationality of policy design, and the choice of firm behavior, so their actual effects may vary by region and industry (Weng et al., 2023). In addition, as a new means of environmental regulation, public participation environmental regulation has gradually become an important supplement to environmental governance. Public participatory environmental regulation emphasizes on promoting enterprises and governments to pay more attention to environmental protection by improving public awareness of environmental protection and enhancing the ability of the public to participate in environmental decision-making (Xie et al., 2023). For example, through information disclosure, public hearings and environmental litigation, the public can better supervise the environmental behavior of enterprises and governments, so as to form an environmental governance system of social co-governance. However, the effect of public participatory environmental regulation is often limited by public awareness of environmental protection, participation channels and participation ability, so its mechanism and effect need further study (Zhou et al., 2021).

Green innovation is one of the important means to achieve green development (Yu et al., 2023). Green innovation refers to innovative activities that adopt new technologies or improve existing technologies in the design, development and implementation of products, services or processes in order to reduce negative environmental impacts, improve resource efficiency, reduce energy consumption and emissions, while creating economic value and social wellbeing. (Wan et al., 2024). Through green innovation, industrial structure can be optimized, resource utilization efficiency can be improved, environmental pollution can be reduced, and the mode of economic development can be changed. At the same time, green innovation can also drive new economic growth points, promote employment and entrepreneurship, and promote sustainable economic development (Miao et al., 2024). Therefore, actively promoting green innovation has become the consensus of governments and enterprises. In recent years, the research on the relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation has made some achievements. First, many studies have shown that the intensity and type of environmental regulations have a significant impact on enterprises' green innovation. Some scholars put forward the Porter hypothesis, which holds that moderate environmental regulations can encourage enterprises to innovate and thus improve their competitiveness. Second, the impact of environmental regulations varies by region, industry, and firm characteristics. Other scholars have pointed out that the environmental policies of different countries and regions will lead to different performance of enterprises in green innovation (Porter and Linde, 1995). In some regions with more liberal environmental policies, companies may lack incentives to innovate because they are able to meet environmental requirements through traditional means (Kemp and Pontoglio, 2011). However, in regions with strict policies, companies are often more willing to invest in R&D and innovation to adapt to policy changes. Based on the above research results, this paper will explore the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulation and green innovation development based on provincial panel data.

The contribution of this paper is embodied in three aspects. Firstly, the classification and mechanism of heterogeneous environmental regulation are studied. This study divides environmental regulation into command and control, market incentive and public participation, which provides a new perspective for environmental regulation theory and policy formulation. Secondly, the promoting effect of common prosperity on green innovation and its regulating effect. Common prosperity not only promotes green innovation, but also regulates the role of heterogeneous environmental regulations, providing a theoretical basis for the coordinated development of green innovation and common prosperity. Finally, the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulation and green innovation from the perspective of regional differences. It is found that regional differences significantly affect the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulation, common prosperity and green innovation, which provides a basis for policymakers to implement heterogeneous environmental regulation and makes up for the shortcomings of existing studies.

2 Literature review

Environmental regulation is the government’s effort to promote sustainable development through appropriate policy measures, guiding enterprises to focus on environmental protection while pursuing economic benefits (Yu and Wang, 2021). In recent years, scholars have conducted more detailed discussions on the impact of environmental regulation, which has evolved from a single type of regulation to multiple types of regulation. Bocher divided environmental regulation into information, cooperation, economy, and regulation based on the selection of environmental policy tools, which became the foundation of later research Böcher, (2012). From the perspective of differentiated corporate decision-making, environmental regulation can be divided into legislative regulation, law enforcement regulation, and economic regulation (Albrizio et al., 2017).

The research on content mainly focuses on direct exploration of corporate competitiveness, which has led to two completely different perspectives. One view is that strict operating costs of enterprises will suppress their competitiveness (Yang et al., 2024); And another proposition is to stimulate innovation vitality, thereby enhancing long-term competitiveness (Lei et al., 2024). As research deepens, scholars gradually realize that there is significant heterogeneity in R&D investment. For example, a study by Jaffe and Palmer, (1997) on manufacturing data in the United States showed a significant positive correlation between pollution control spending and research and development investment. L ó pez (2018) pointed out that in some developed countries, strong environmental regulations may incentivize companies to engage in green innovation, while in developing countries, overly strict regulations may impose heavier burdens on companies, thereby suppressing innovation incentives. Secondly, the regional heterogeneity of regulations is closely related, with regions with more mature economic development often having stricter environmental regulations (Kemp and Pontoglio, 2011). The role of social factors in heterogeneous environmental regulation is also receiving increasing attention, as public attitudes and participation in environmental protection can have a significant impact (Hügel and Davies, 2020).

It has always been a hot topic in academic research. Some studies suggest that environmental regulation can promote the development of green innovation. For example, Porter and Linde’s (1995) Porter hypothesis suggests that appropriately designing corporate innovation and applying new technologies can improve productivity. However, studies have also shown that environmental regulations may have a restraining effect on green innovation. For example, Cropper and Oates (1992) argue that additional environmental regulations will only increase companies' costs and reduce their ability to innovate in specific company technologies, resource allocation, and consumer demand. Further research suggests that corporate characteristics such as size, industry, and technological capabilities can also affect their response to environmental regulations. Due to abundant resources, large companies are better able to cope with the challenges brought by environmental regulations and participate in technological innovation. On the other hand, small and medium-sized enterprises may face greater pressure and therefore require more policy support and incentives. Research has shown that when formulating environmental policies, governments should implement differentiated policies as needed to effectively promote green innovation.

In summary, heterogeneous environmental regulation is an important tool for promoting green innovation (Zhang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020). However, current research on the impact of heterogeneous environment r mainly focuses on the enterprise level, with less research at the provincial level. In addition, the mechanisms of action of intermediary tools vary (Stavins, 1996). Common prosperity is also an important indicator of the impact of heterogeneous environmental regulation on the development of green innovation. It mainly measures the fairness of social wealth distribution and the balance of economic development, and as an intermediary variable, it plays a guiding role in policy formulation. The goal of common prosperity encourages the government to pay more attention to the balance between social equity and economic development when formulating and implementing environmental regulation. Therefore, it is necessary to study the impact mechanism of various types of environmental regulatory tools in different regions of China on the development of green innovation in order to formulate China’s environmental regulatory policies more accurately and further improve the development level of green innovation.

3 Theoretical assumptions and mechanistic analysis

3.1 Environmental regulation and green innovation

Command-and-control environmental regulation is an environmental management method based on government coercion. It directly restricts the environmental behavior of enterprises through measures such as setting pollutant discharge standards, implementing treatment within a time limit, and forcing the closure of polluting enterprises (Cui et al., 2022). At the initial stage, low intensity command-and-control environmental regulation may be due to low compliance costs, enterprises lack sufficient motivation to carry out green innovation, and the effect of green innovation is not significant. However, with the strengthening of command-and-control environmental regulations, enterprises are faced with more stringent environmental requirements, and compliance costs rise significantly, forcing enterprises to reduce environmental impact, improve production efficiency and reduce costs through technology research and development and green innovation (Liu et al., 2024). For example, provincial governments, through strict pollutant discharge standards, force enterprises to develop cleaner production processes or introduce environmentally friendly technologies, thus promoting the development of green innovation (Lin and Du, 2015; Zhao et al., 2020). Therefore, command-and-control environmental regulation promotes green innovation behavior at the provincial level by enhancing environmental binding force.

H1. The relationship between command-and-control environmental regulation and green innovation across regions is U-shaped

Market incentive environmental regulation is a kind of environmental management mode based on economic means, mainly through tax incentives, financial subsidies, emission trading and other market-oriented tools to encourage enterprises to adopt environmental protection behaviors. In the initial stage, appropriate market incentive environmental regulation can stimulate green innovation input and promote the development of green innovation by reducing environmental protection costs (Xie et al., 2024). However, when the intensity of market incentive environmental regulations is too high, too strong economic incentives may lead to enterprises over-relying on external subsidies or preferential policies instead of achieving green development through independent technological innovation, thus inhibiting the effect of green innovation (Dong et al., 2023). For example, provincial governments encourage enterprises to adopt environmentally friendly technologies through high subsidies, which may cause enterprises to neglect R&D investment in technology in order to obtain subsidies, thus affecting the sustainability of green innovation (Kemp and Pontoglio, 2011; Testa et al., 2011). Therefore, the market incentive environmental regulation at the provincial level needs to balance the incentive intensity within a moderate range in order to give full play to its role in promoting green innovation.

H2. The relationship between market-incentivized environmental regulation and green innovation in the regions is inverted U-shape

Public participation environmental regulation is an environmental management method based on social forces. It indirectly affects the environmental behavior and green innovation of enterprises by improving public awareness of environmental protection, enhancing social supervision, and promoting public participation in environmental governance (Weihe, 2023). In the initial stage, low-intensity public participatory environmental regulation may lead to weak public awareness of environmental protection, insufficient social supervision, and insignificant promotion of green innovation (Karplus et al., 2021). However, with the enhancement of the intensity of public participatory environmental regulation, the enhancement of public awareness of environmental protection and the enhancement of social supervision, enterprises are forced to increase investment in green innovation in order to meet social expectations and avoid negative evaluation, so as to promote the development of green innovation (Hille et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2020). For example, the increase in consumer preference for environmentally friendly products has forced the development and promotion of green products, thus promoting the realization of green innovation. Therefore, public participatory environmental regulation at the provincial level promotes enterprises' green innovation behavior by enhancing social participation and supervision.

H3. The relationship between public participation environmental regulation and green innovation in each region is U-shaped.

3.2 The moderating role of common prosperity

Against the backdrop of the global environmental crisis and resource scarcity, green innovation has become an important driver of sustainable development in all countries (Wang et al., 2021). Heterogeneous environmental regulation influences innovation behavior at the provincial level through different policy instruments, and common prosperity, as an important socioeconomic goal, may play a moderating role in this process. First, command-and-control environmental regulation directly constrains provincial environmental behavior through laws and regulations. Such coercive measures may initially lead to higher costs and thus dampen innovation incentives in the short run (Wu W. Q. et al., 2020). However, when the level of regional common prosperity rises, public concern for environmental protection increases and a sense of social responsibility ensues (Zhao et al., 2022). In this context, the provincial level is more likely to initiate green innovations to meet social expectations and market demands. Common prosperity can provide a more stable economic base and favorable development environment for the provincial level, which makes it more responsive to command-and-control environmental regulations (Tomizawa et al., 2020). This can lead to a U-shaped relationship.

H4. Common prosperity positively moderates the U-shaped relationship between command-and-control environmental regulation and green innovation.

Second, market-incentivized environmental regulations aims to incentivize green innovation development through market mechanisms such as financial subsidies and tax incentives (Gao et al., 2024). At the provincial level, these types of regulatory measures are often able to quickly attract positive responses from regions at the initial stage. By introducing a series of preferential policies, such as providing subsidies for R&D funding and reducing or exempting related taxes and fees, provinces effectively reduced the cost of green innovation R&D and application, thus stimulating the enthusiasm of regions to carry out green innovation (Xu et al., 2023). During this period, frequent and efficient interactions between the government and market players jointly promoted the rapid development of green innovation. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H5. Common prosperity negatively moderates the inverted U-shaped relationship between market-incentivized environmental regulation and green innovation.

Finally, the core of public participatory environmental regulation as an innovative environmental management model lies in fully recognizing the irreplaceable role of the public in environmental protection. Under the traditional environmental management framework, the public is often regarded as a passive recipient of environmental policies, and its role is relatively passive and limited (Zhong et al., 2021). However, with the popularization and enhancement of environmental protection awareness, the public has gradually realized its own responsibility in environmental protection and started to actively participate in the decision-making and monitoring process of environmental protection (Jiang and Xie, 2021). Especially in the context of the steady increase in the level of common prosperity in the region, the public’s standard of living continues to improve, and their desire for a better life is becoming stronger and stronger. This aspiration is not only reflected in material affluence, but also in higher demands for environmental quality (Islam and Wang, 2023). The public began to pay more attention to the environmental problems around them, such as air pollution, water pollution, soil pollution, etc., and hope that the government can take effective measures to solve them.

H6. Common prosperity positively moderates the U-shaped relationship between public participatory environmental regulation and green innovation.

4 Models and data

4.1 Selection of variables

4.1.1 Explained variables

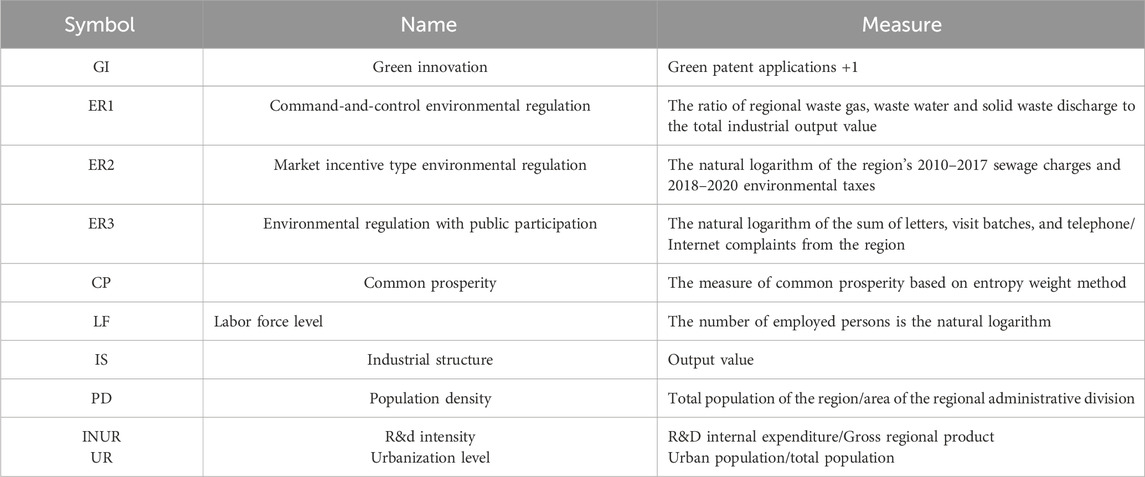

Green innovation is to see whether we are doing something to protect the environment, and whether we are developing sustainably. Nowadays, both at home and abroad, people like to use the number of green patent applications as a measure of green innovation in their research. This paper follows this approach and uses the number of green patent applications per province per year and then adds a natural logarithm so that it can better measure green innovation (Ghisetti and Quatraro, 2017). The advantage of this method is that with the use of the natural logarithm, it reduces the bias in the data, making it more scientific and accurate as shown in Table 1.

4.1.2 Explanatory variables

The disparate environmental regulations are divided into three categories (Ren et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2019). The first is command-and-control environmental regulation (ER1), which looks at how many environmental statutes, regulations, and standards come out of each province each year. The second is market-incentivized environmental regulation (ER2), which looks at how much money each province spends on pollution control as a percentage of its GDP. The third is public participation-based environmental regulation (ER3), which is expressed by adding up the number of letters, phone calls, and internet complaints and taking a natural logarithm. This way we can more clearly distinguish between different environmental regulations.

4.1.3 Moderator variables

Common prosperity Level (CP). The combination of “common” and “prosperity” is the foundation. Therefore, we measures the common prosperity level of Chinese cities from the two dimensions of “common” and “prosperity”, and adopts the entropy weight method to determine the common prosperity level (Liu et al., 2023), as shown in Table 2.

4.1.4 Control variables

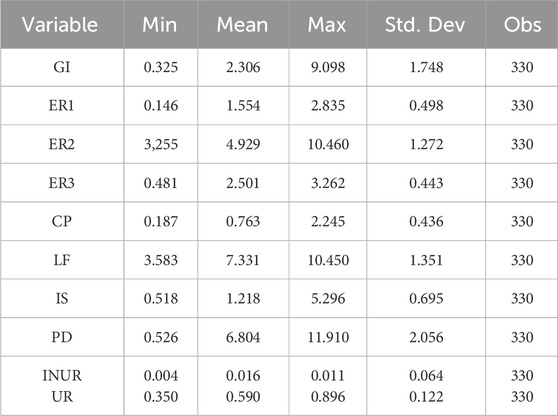

Based on the existing research, some indicators with provincial characteristics are added as control variables to reduce the analysis error as much as possible. Labor force level (LF) (Zhang et al., 2023); Industrial structure (IS) (Xue et al., 2022); Population density (PD) (Tan and Kaili, 2023); R&D intensity (INUR) (Liu et al., 2017); Urbanization level (UR) (Chen and Lin, 2021). Table 3 is the descriptive statistics of the variables.

4.2 Construction of empirical model

To test the above hypotheses one by one, regression models Equations 1–3 are constructed:

where, i and t represent individual and time. GI represents provincial green innovation and ER represents heterogeneous environmental regulation. In order to test the possible nonlinear relationship between heterogeneous, the second term ER2 of heterogeneous environmental regulation is added. CP represents the development level of common prosperity, (CP*ER) represents the interaction term between common prosperity and heterogeneous environmental regulation, and (CP*ER2) represents the interaction term between common prosperity and the secondary term of heterogeneous. X represents other control variables, ∑Year and ∑Province represent the fixed effects of each province in the year and place, respectively, ε is the random disturbance term.

4.3 Data sources

When writing this study, we fully considered the availability and comprehensiveness of the data. Therefore, this paper selects 30 provinces in Chinese Mainland from 2010 to 2020 (excluding Xizang Autonomous Region, Macao Special Administrative Region and Taiwan) as research objects, in order to comprehensively and accurately reflect the relationship. In terms of data sources, the variables involved in this article are mainly sourced from the following authoritative yearbooks: China Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Economic Statistical.

In order to ensure the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the study, we used interpolation to fill in missing data in some variables. The use of interpolation method aims to restore the original trend of data as much as possible and reduce the potential impact of data loss on research results. In addition, in order to eliminate or reduce the differences in numerical scale of different variables and avoid certain variables dominating the model results due to their values being too large or too small during statistical analysis, we performed logarithmic transformation on all variables. Logarithmic processing not only helps balance the order of magnitude differences between variables, but also improves the distribution characteristics of data to a certain extent, making it closer to a normal distribution, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and reliability of statistical analysis.

5 Empirical results and analysis

5.1 Regression analysis

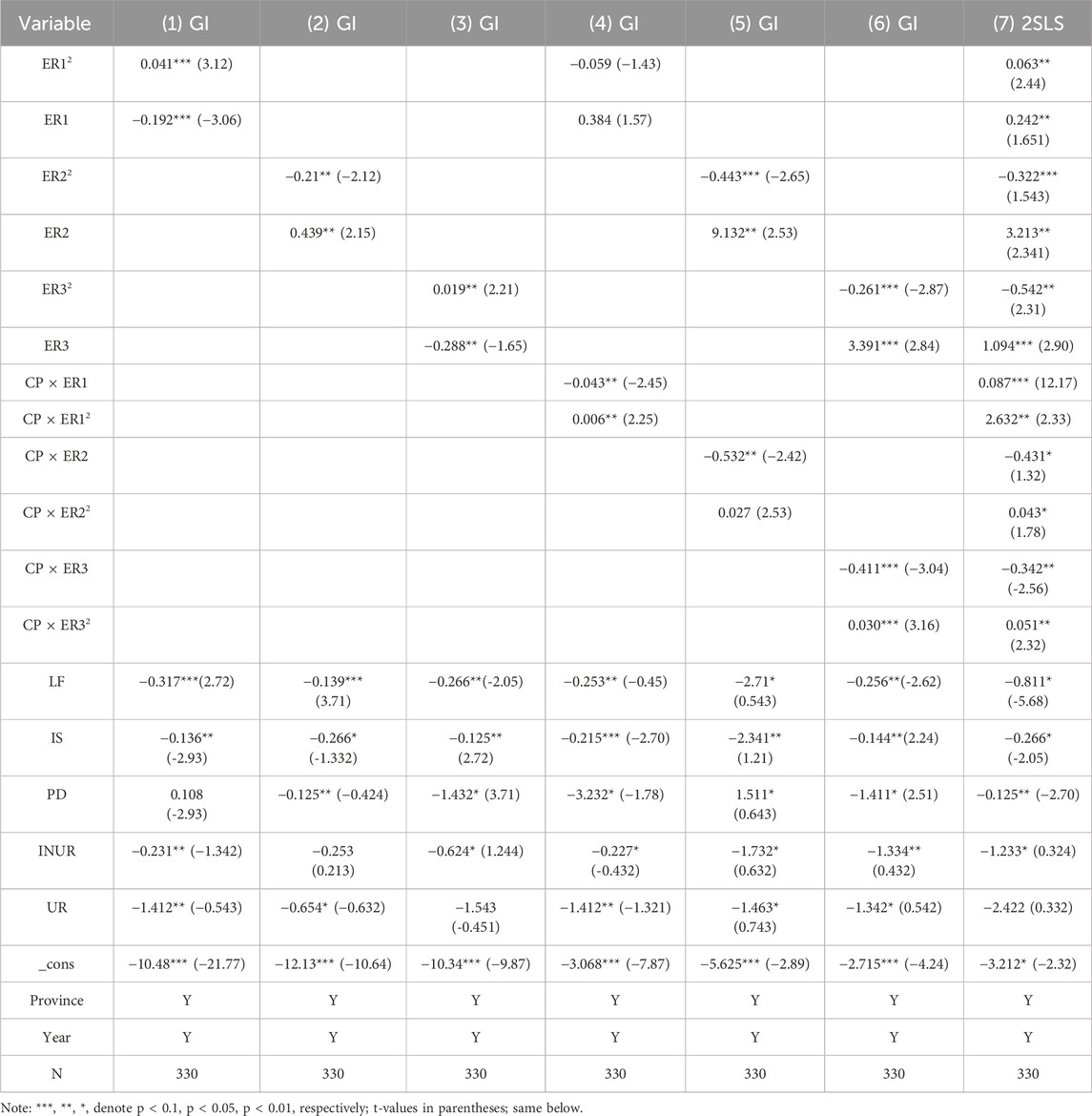

Table 4 shows the regression results for the main variables. Among them, column (1) reports the effect of ER1 on provincial green innovation, ER1 and ER12 coefficients of −0.192 and 0.041 respectively are significant at the 1% level, indicating that ER1 has a U-shape relationship with GI and H1 is verified. The curve inflection point 2.341, when the provincial ER1 intensity has not reached the inflection point, that is, when the cost of institutional implementation is lower than the cost of research and development, there will be a lack of incentives for green innovation, and they will choose to pay low-cost pollution penalties rather than actively engage in green innovation. When the provincial ER1 exceeds the inflection point, when the cost of pollution penalties is higher than the operational benefits, it pushes back green R&D and gradually generates an innovation compensation effect to promote green innovation.

Column (2) of Table 4 reports the impact of ER2 on provincial green innovation. The ER2 and ER22 coefficients are 0.439 and −0.21, respectively, which are both significant at the 5% level, indicating that ER2 has a significant inverted U-shaped relationship with GI, as verified by H2. The inflection point of the curve is 1.05, indicating that when the ER2 intensity is located on the left side of the inflection point, facing the market-incentivized environmental regulation, the sectors are more inclined to actively cater to the subsidy policy, improve the original production technology and product design to meet the environmental standards of the green products in order to better enjoy the policy incentives. When ER2 intensity is on the right side of the inflection point, in order to obtain stronger green incentives, they tend to take advantage of the government’s information disadvantage to seek rents, reduce the real investment in green R&D, and weaken the ability of green innovation.

The impact of public participation-based environmental regulation on green innovation is reported in column (3) of Table 4. The coefficients of ER3 and ER32 are −0.288 and 0.019 in that order, which are significant at the 10% and 5% levels, respectively, indicating that ER3 has a significant U-shaped relationship with GI, and H3 is verified. The inflection point of the curve is 7.579, the strength of public participatory environmental regulation is small, reflecting the relatively weak public awareness of environmental protection and the weak enthusiasm for green innovation. Along with the enhancement of ER3, the public plays an increasing role in social opinion and supervision, and its consumption preference is also tilted toward environmentally friendly products, which drives green innovation output to a certain extent.

Further, the moderating effect of common prosperity is tested (Haans et al., 2016). In column (4) of Table 2, the coefficient of the interaction term between CP and ER12 is 0.006, which is significantly positive at the 5% level, the promotion effect of ER1 on GI increases with CP,

5.2 Endogenetic analysis

Because there may be some endogeneity problem between variables, it will affect the empirical conclusion. Referring to the practice of previous scholars, the lag of heterogeneous environmental regulation was used as an instrumental variable for 2SLS estimation (Huang et al., 2023). As shown in column (7) of Table 4: Except for some changes in the significance of some control variables, the coefficient sizes, positive and negative directions of the main explanatory variables and control variables are basically consistent with the benchmark regression. This also shows that the endogeneity problem of the model in this paper does not affect the robustness of the regression results on the whole, and the regression results are relatively robust.

5.3 Robustness tests

5.3.1 Replacement of explanatory variables

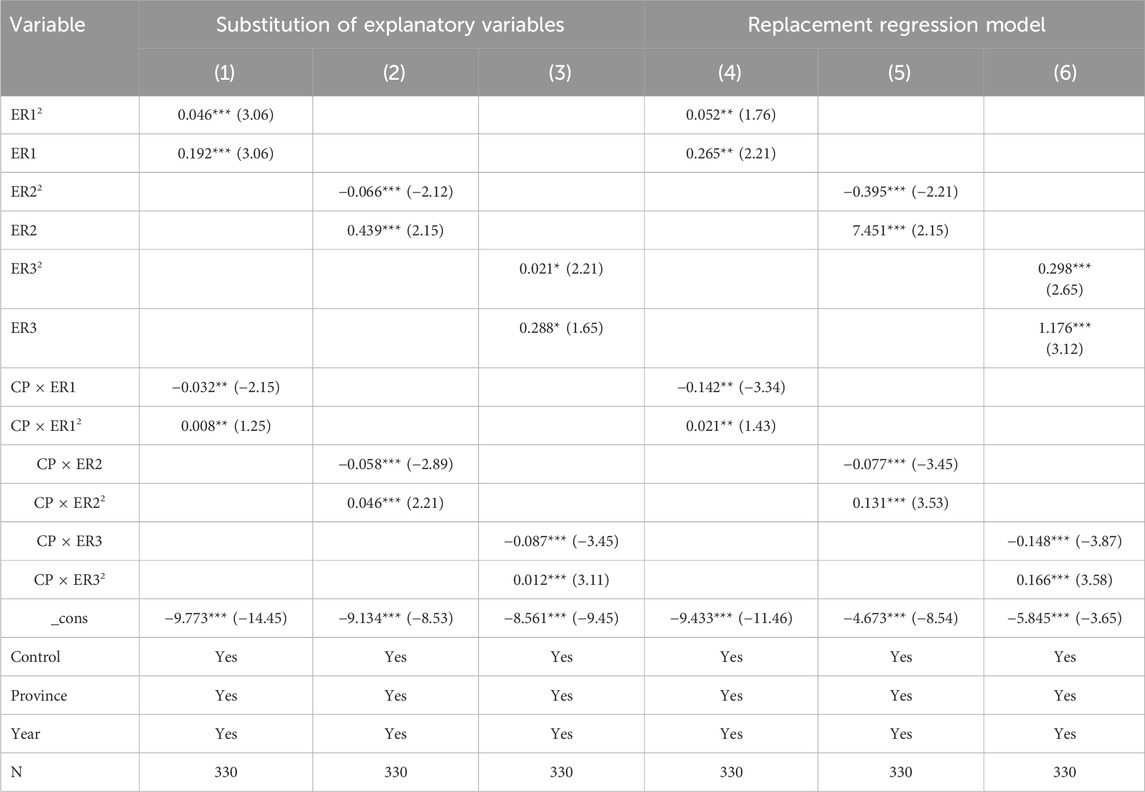

Drawing on the study of (Lin and Li, 2011), in order to enhance robustness, this paper redefines green innovation in terms of green patent applications/total patent applications, and the results are shown in columns (1)–(3) of Table 5. The results are shown in columns (1)–(3) of Table 5. The coefficients of ER12 and ER22 are 0.052 and −0.066 respectively, which are significant at the 1% level, and the coefficient of ER32 is 0.021, which is significant at the 10% level, and the coefficients of the interaction term between CP and ER12 are 0.008, which are significant at the 5% level, while the coefficients of the interaction terms between CP, ER22 and ER32 are 0.046 and 0.012 respectively, the conclusion is basically consistent with the previous paper and well supports the previous hypothesis.

5.3.2 Replacement regression models

In order to ensure the reliability of the model design, this paper adopts the Tobit model to conduct regression analysis again, and the results are shown in columns (4)–(6) in Table 5. It can be seen from the primary regression coefficients of ER1, ER2 and ER3 that all are at a certain significant level, and the secondary regression coefficients are also at a certain significant level, indicating that the impact of heterogeneous environmental regulations on green innovation is U-shaped. The regression coefficient of common prosperity is significant at the 1% level, and the primary and secondary interaction terms of common prosperity and heterogeneous environmental regulations are significant at or above the 5% level, indicating that the realization of common prosperity can positively regulate the impact of environmental regulations on green innovation. The results obtained by the replacement regression model are consistent with the baseline regression, which indicates that the above conclusions are robust.

5.4 Heterogeneity analysis

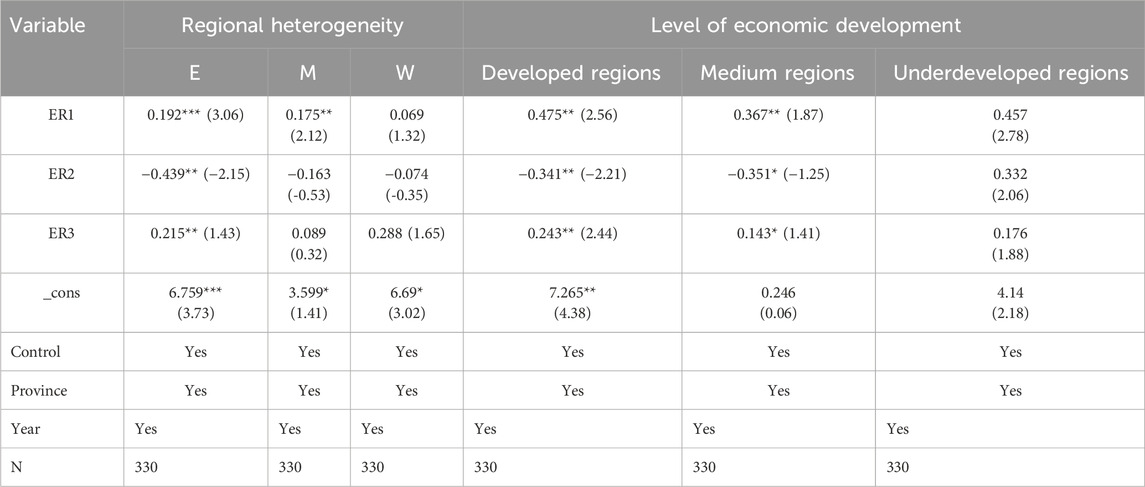

Due to the different levels of environmental policies and common prosperity development in each region, the impact mechanism of green innovation in each region also reflects certain geographical characteristics. Based on this, this paper further divides the East, Central and West samples to explore the differences in the geographical effects of the sub-samples.

5.4.1 Heterogeneity across regions

In Table 6, (1) the impact of command-and-control environmental regulations on green innovation in both the eastern and central regions exhibits a U-shaped characteristic, while in contrast, the relationship between the two in the western region is not significant; (2) the impact of market-incentivized environmental regulation on green innovation in the eastern region has an inverted U-shape, which suggests that green subsidy incentives in the eastern region are more effective in compensating for the cost of pollution control (Zeng and Yang, 2023). The relationship between the two is not significant in the central and western regions; (3) the effect of public participatory environmental regulation on green innovation is U-shaped in the eastern region and insignificant in both the central and western regions, which may be due to the overall low public environmental awareness and insufficient green innovation pushback in the central and western regions.

5.4.2 Heterogeneity in the level of economic development

To examine the impact of heterogeneous environmental regulations on green innovation across different levels of economic development, following the research of Song et al. (2020), we use the level of urban economic development as the criterion for classification, with per capita GDP as the measure of economic development level. By calculating the median to group the samples and performing regression analysis, the results are shown in Table 6, columns (4)–(6). Heterogeneous environmental regulations have a more significant impact on developed and moderately developed regions, possibly because developed regions have scale advantages in terms of industrial structure, environmental governance investment, and technological innovation, forming a certain agglomeration effect that is conducive to the optimal allocation of resources, while the effects in less developed regions are not significant.

6 Conclusions and policy implications

6.1 Conclusion

The article based on panel data from 30 provinces from 2010 to 2020, constructs a two-way fixed effects model to test the relationship between heterogeneous environmental regulations and green innovation, as well as the joint effect of common prosperity. The research results show:

(1) In response to the differentiated impacts of various types of environmental regulations on green innovation, the government should implement more refined and differentiated environmental regulation strategies to maximize their positive effects while minimizing potential negative impacts. For command-and-control environmental regulations, given the U-shaped relationship between them and green innovation, the government should timely adjust the intensity of regulations to ensure that policy can cross the inflection point of the U-shaped curve, thereby stimulating the innovation compensation effect of enterprises. For market-incentivized environmental regulation, in light of the inverted U-shaped relationship with green innovation, the government must be vigilant against rent-seeking behavior and reduced innovation investment that may result from excessive incentives. Regarding public participation-based environmental regulation, enhancing public environmental awareness is key to breaking through the inflection point of the U-shaped curve. The government should increase the intensity of environmental education and propaganda, popularize the concept of green living through various channels such as media and social platforms, and enhance the public’s sense of environmental responsibility and participation.

(2) Common prosperity has a significant promoting effect on green innovation, and positively regulates the U-shaped relationship between command and control, public participation-based environmental regulation and green innovation, and negatively regulates the inverted U-shaped relationship between market-incentivized environmental regulation and green innovation. Common prosperity not only directly promotes the flow of green elements, optimizes the research and development process, and promotes green innovation, but also shifts the U-shaped curve of command-and-control, public participation regulation and green innovation to the left, and the inverted U-shaped curve of market incentive regulation and green innovation to the right.

(3) By comparing the regional effects of heterogeneous environmental regulation, common prosperity and green innovation, it is found that there are obvious regional differences among the influence relationships among the three. Among them, command-control regulation only has a “compensation effect” in the eastern and central regions, market-incentivized environmental regulation only has an inverted U-shaped relationship in the eastern region, and public participation-based environmental regulation only has a significant reverse force effect in the eastern region. Furthermore, the regulatory ability of common prosperity to command-and-control and market-incentive regulation is more significant in the central and western regions, while the regulatory ability to public participation regulation is more significant in the eastern and central regions.

6.2 Policy implications

6.2.1 Differentiated implementation of environmental regulation policies to optimize the incentive mechanism for green innovation

In view of the differentiated impact of different types of environmental regulations on green innovation, the government should implement more refined and differentiated environmental regulation strategies to maximize the positive effects and minimize the potential negative effects. For command-and-control environmental regulation, in view of the U-shaped relationship between it and green innovation, the government should timely adjust the regulatory intensity to ensure that the regulatory policy can cross the inflection point of the U-shaped curve, so as to stimulate the innovation compensation effect of provinces. In view of the inverted U-shaped relationship between market-motivated environmental regulation and green innovation, the government should be alert to the rent-seeking behavior and the reduction of innovation investment that may be caused by excessive incentives. With regard to public participatory environmental regulation, enhancing public awareness of environmental protection is the key to breaking through the inflection point of the U-shaped curve. The government should strengthen environmental protection education and publicity, popularize the concept of green life through various channels such as media and social platforms, and enhance the public’s sense of environmental responsibility and participation.

6.2.2 Strengthening the moderating role of common wealth to promote the balance

The government needs to take the following measures: first, prioritize investment in green infrastructure, such as clean energy and public transportation, to promote green innovation and narrow regional development gaps. Second, through fiscal and tax policies, it should guide the flow of green innovation resources to less developed regions, especially in the central and western regions, in order to realize the balanced development of green technologies. Finally, establish a cross-regional and cross-industry green innovation cooperation mechanism to share R&D results and promote knowledge spillover and collaborative innovation, especially in digital investment, in order to enhance the efficiency of green innovation in the central and western regions. These measures will help to realize the positive interaction to the balanced development.

6.2.3 Constructing a multi-level environmental governance system

In response to the geographical characteristics of environmental regulation, and under the guidance of the concept of common prosperity, we have constructed a differentiated environmental governance system aimed at solving environmental problems more effectively. Specific measures include: first, strengthening inter-regional synergistic governance, establishing a cross-regional pollution prevention and control mechanism, and promoting the formation of positive spillover effects of green innovation through sharing governance experience, so that the fruits of environmental governance can benefit a wider range of regions; second, encouraging regions to tailor distinctive environmental policies based on their own resources and ecological characteristics, such as promoting a circular economy, and implementing ecological protection measures, in order to better meet the actual needs of local development; again, we will enhance the capacity of grassroots governance, and improve the relevance and effectiveness of environmental governance through community self-governance and public participation, in particular by strengthening public participation in environmental regulation. In terms of public participation, we should give full play to the role of grass-roots organizations as a bridge and link to promote effective communication and cooperation among the Government, enterprises and the public. These diversified measures will give a strong impetus to the realization of a multi-level and differentiated pattern of environmental governance, which will in turn promote the geographically balanced development of green innovation and lay a solid foundation for achieving the goal of sustainable development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JG: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the referees for their helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of our paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albrizio, S., Kozluk, T., and Zipperer, V. (2017). Environmental policies and productivity growth: evidence across industries and firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 81, 209–226. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2016.06.002

Böcher, M. (2012). A theoretical framework for explaining the choice of instruments in environmental policy. For. Policy Econ. 16, 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2011.03.012

Chen, Y., and Lin, B. (2021). Understanding the green total factor energy efficiency gap between regional manufacturing—insight from infrastructure development. Energy 237 (3), 121553. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121553

Cropper, M. L., and Oates, W. E. (1992). Environmental economics: a survey. Journal of economic literature. 30 (2), 675–740.

Cui, J., Dai, J., Wang, Z., and Zhao, X. (2022). Does environmental regulation induce green innovation? A panel study of Chinese listed firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 176, 121492. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121492

Doğan, B., Chu, L. K., Ghosh, S., Truong, H. H. D., and Balsalobre-Lorente, D. (2022). How environmental taxes and carbon emissions are related in the G7 economies? Renew. Energy 187, 645–656. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.01.077

Dong, K., Wei, S., Liu, Y., and Zhao, J. (2023). How does energy poverty eradication promote common prosperity in China? The role of labor productivity. Energy Policy 181, 113698. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113698

Gao, J. Z., Hua, G. H., Randhawa, A., and Huo, B. F. (2024). Heterogeneous environmental regulations and carbon emission efficiency in China: a perspective of resource endowment. Energy & Environ. doi:10.1177/0958305x241270274

Ghisetti, C., and Quatraro, F. (2017). Green technologies and environmental productivity: a cross-sectoral analysis of direct and indirect effects in Italian regions. Ecol. Econ. 132, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.10.003

Haans, R. F., Pieters, C., and He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U-and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Manag. J. 37 (7), 1177–1195. doi:10.1002/smj.2399

Hille, E., Althammer, W., and Diederich, H. (2020). Environmental regulation and innovation in renewable energy technologies: does the policy instrument matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 153, 119921. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119921

Hügel, S., and Davies, A. R. (2020). Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: a review of the research literature. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11 (4), e645. doi:10.1002/wcc.645

Islam, M. Z., and Wang, S. (2023). Exploring the unique characteristics of environmental sustainability in China: navigating future challenges. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 21 (1), 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.cjpre.2023.03.004

Jaffe, A. B., and Palmer, K. (1997). Environmental regulation and innovation: a panel data study. Rev. Econ. statistics 79 (4), 610–619. doi:10.1162/003465397557196

Jiang, Y., and Xie, Q. (2021). Solid promotion common prosperity: logical framework and realizing route. Econ. Rev. J. 4, 15–24.

Karplus, V. J., Zhang, J., and Zhao, J. (2021). Navigating and evaluating the labyrinth of environmental regulation in China. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 15 (2), 300–322. doi:10.1086/715582

Kemp, R., and Pontoglio, S. (2011). The innovation effects of environmental policy instruments—a typical case of the blind men and the elephant? Ecol. Econ. 72, 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.014

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., and Yu, Z. (2021). Technological innovation and environmental taxes toward a carbon-free economy: an empirical study in the context of COP-21. J. Environ. Manag. 298, 113418. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113418

Lei, P., Cai, Q., and Jiang, F. (2024). Assessing the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise high-quality development in China: a two-tier stochastic frontier model. Energy Econ. 133, 107502. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107502

Lin, B., and Du, K. (2015). Modeling the dynamics of carbon emission performance in China: a parametric Malmquist index approach. Energy Econ. 49, 550–557. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2015.03.028

Lin, B. Q., and Li, X. H. (2011). The effect of carbon tax on per capita CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 39 (9), 5137–5146. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.05.050

Liu, Y., Dong, K., Wang, J., and Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2023). Towards sustainable development goals: does common prosperity contradict carbon reduction? Econ. Analysis Policy 79, 70–88. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2023.06.002

Liu, Y., Du, J. Y., and Wang, K. (2024). Towards common prosperity: the role of mitigating energy inequality. Energy Policy 195, 114386. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114386

Liu, Y., Gao, C., and Lu, Y. (2017). The impact of urbanization on GHG emissions in China: the role of population density. J. Clean. Prod. 157, 299–309. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.138

Miao, C., Chen, Z., and Zhang, A. (2024). Green technology innovation and carbon emission efficiency: the moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Sci. Total Environ. 938, 173551. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173551

Porter, M. E., and Linde, C. v. d. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Ren, S., Li, X., Yuan, B., Li, D., and Chen, X. (2018). The effects of three types of environmental regulation on eco-efficiency: a cross-region analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 173, 245–255. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.08.113

Shao, S., Hu, Z., Cao, J., Yang, L., and Guan, D. (2020). Environmental regulation and enterprise innovation: a review. Bus. strategy Environ. 29 (3), 1465–1478. doi:10.1002/bse.2446

Shen, N., Liao, H. L., Deng, R. M., and Wang, Q. W. (2019). Different types of environmental regulations and the heterogeneous influence on the environmental total factor productivity: empirical analysis of China's industry. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 171–184. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.170

Song, M., Wu, J., Song, M., Zhang, L., and Zhu, Y. (2020). Spatiotemporal regularity and spillover effects of carbon emission intensity in China's Bohai Economic Rim. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140184. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140184

Stavins, R. N. (1996). Correlated uncertainty and policy instrument choice. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 30 (2), 218–232. doi:10.1006/jeem.1996.0015

Tan, L., and Kaili, Z. (2023). Effects of the digital economy on carbon emissions in China: an analysis based on different innovation paths. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 79451–79468. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-27975-2

Testa, F., Iraldo, F., and Frey, M. (2011). The effect of environmental regulation on firms’ competitive performance: the case of the building & construction sector in some EU regions. J. Environ. Manag. 92 (9), 2136–2144. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.03.039

Tomizawa, A., Zhao, L., Bassellier, G., and Ahlstrom, D. (2020). Economic growth, innovation, institutions, and the Great Enrichment. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 37 (1), 7–31. doi:10.1007/s10490-019-09648-2

Wan, K., Cao, L., and He, Y. (2024). Can green bonds promote corporate green technology innovation? evidence from China. Appl. Econ., 1–13. doi:10.1080/00036846.2024.2336890

Wang, L. H., Wang, Z., and Ma, Y. T. (2022). Heterogeneous environmental regulation and industrial structure upgrading: evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (9), 13369–13385. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16591-7

Wang, M., Li, Y., Li, J., and Wang, Z. (2021). Green process innovation, green product innovation and its economic performance improvement paths: a survey and structural model. J. Environ. Manag. 297, 113282. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113282

Weihe, Z. (2023). The Chinese path to rural common prosperity: based on an analysis of Jiangsu and Zhejiang rural demonstration projects. Soc. Sci. China 44 (3), 137–152. doi:10.1080/02529203.2023.2254114

Weng, Z. X., Tong, D., Wu, S. W., and Xie, Y. (2023). Improved air quality from China?s clean air actions alleviates health expenditure inequality. Environ. Int. 173, 107831. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2023.107831

Wu, D. D., Wang, Y. H., and Qian, W. Y. (2020). Efficiency evaluation and dynamic evolution of China's regional green economy: a method based on the Super-PEBM model and DEA window analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121630. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121630

Wu, W. Q., Liu, Y. Q., Wu, C. H., and Tsai, S. B. (2020). An empirical study on government direct environmental regulation and heterogeneous innovation investment. J. Clean. Prod. 254, 120079. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120079

Xie, T. C., Zhang, Y., and Song, X. Y. (2024). Research on the spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of common prosperity in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26 (1), 1851–1877. doi:10.1007/s10668-022-02788-4

Xie, T. T., Yuan, Y., and Zhang, H. (2023). Information, awareness, and mental health: evidence from air pollution disclosure in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 120, 102827. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2023.102827

Xu, Q., Li, X., Dong, Y., and Guo, F. (2023). Digitization and green innovation: how does digitization affect enterprises’ green technology innovation? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 68, 1282–1311. doi:10.1080/09640568.2023.2285729

Xue, Y., Tang, C., Wu, H., Liu, J., Hao, Y., Policy, E., et al. (2022). The emerging driving force of energy consumption in China: does digital economy development matter? Energy Policy 165, 112997. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112997

Yang, X., and Tang, W. L. (2023). Additional social welfare of environmental regulation: the effect of environmental taxes on income inequality. J. Environ. Manag. 330, 117095. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.117095

Yang, Z., Liu, P., and Luo, L. (2024). How does environmental regulation affect corporate green innovation: a comparative study between voluntary and mandatory environmental regulations. J. Comp. Policy Analysis Res. Pract. 26 (2), 130–158. doi:10.1080/13876988.2024.2328602

Yu, H., Wang, J., Hou, J., Yu, B., and Pan, Y. (2023). The effect of economic growth pressure on green technology innovation: do environmental regulation, government support, and financial development matter? J. Environ. Manag. 330, 117172. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.117172

Yu, X., and Wang, P. (2021). Economic effects analysis of environmental regulation policy in the process of industrial structure upgrading: evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Sci. Total Environ. 753, 142004. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142004

Zeng, J., and Yang, M. (2023). Digital technology and carbon emissions: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 430, 139765. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139765

Zhang, W., Fan, H., and Zhao, Q. (2023). Seeing green: how does digital infrastructure affect carbon emission intensity? Energy Econ. 127, 107085. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107085

Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Xue, Y., and Yang, J. (2018). Impact of environmental regulations on green technological innovative behavior: an empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 188, 763–773. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.013

Zhao, J., Shahbaz, M., and Dong, K. (2022). How does energy poverty eradication promote green growth in China? The role of technological innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 175, 121384. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121384

Zhao, X., Liu, C., Sun, C., and Yang, M. (2020). Does stringent environmental regulation lead to a carbon haven effect? Evidence from carbon-intensive industries in China. Energy Econ. 86, 104631. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104631

Zhong, S., Xiong, Y., and Xiang, G. (2021). Environmental regulation benefits for whom? Heterogeneous effects of the intensity of the environmental regulation on employment in China. J. Environ. Manag. 281, 111877. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111877

Zhou, G., Liu, W., Wang, T., Luo, W., and Zhang, L. (2021). Be regulated before be innovative? How environmental regulation makes enterprises technological innovation do better for public health. J. Clean. Prod. 303, 126965. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126965

Keywords: heterogeneous environmental regulation, moderating effect, common prosperity, green innovation, regulating effect

Citation: Zhang Y and Gao J (2025) Heterogeneous environmental regulation, common prosperity and green innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1544670. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1544670

Received: 13 December 2024; Accepted: 14 April 2025;

Published: 14 May 2025.

Edited by:

Jiachao Peng, Wuhan Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Wei Zhang, Wuhan University of Technology, ChinaBai Jun, Huainan Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingke Gao, Z2FvamluZ2tlQGN1Zy5lZHUuY24=

Yuchen Zhang

Yuchen Zhang Jingke Gao

Jingke Gao