- 1Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa

- 2University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa

The concept of silent violence refers to the hidden harm embedded in policy and economic systems, manifesting as the repression of activists, displacement of communities, and exploitation of labour across transitions to low-carbon economies. This article examines how structural barriers embedded in global just transition policies and energy governance frameworks produce forms of silent violence (SV) that disproportionately harm marginalized communities. Drawing on a comparative, multi-case analysis from Bolivia, Canada, South Africa, and Brazil, the study argues that SV is not accidental but a governance-enabled outcome, manifested through policy loopholes, non-consultative permitting, regulatory capture, and enforcement failures. Conceptually, SV is framed as a subset of structural violence that remains legally unframed, institutionally normalized, and largely invisible in climate policy discourse. The article advances a typology of silent violence, ranging from soft forms (epistemic exclusion, procedural marginalization) to hard forms (criminalization, state repression, and lethal harm). We introduce the Silent Violence Continuum as an analytical tool to map how different governance instruments condition escalating harms under the guise of sustainable development. The study contributes to critical climate justice scholarship by showing how SV operates as a design feature of transition governance rather than a failure. The article calls for the integration of silent violence metrics into climate policy evaluation to support more equitable, transparent, and non-violent transitions.

1 Introduction

The just transition concept emerged from labour and environmental justice movements, envisioning a rapid shift from fossil fuels to clean energy that protects workers, communities, and ecosystems. Early scholarship emphasized labour protections in the coal sector (e.g., Rosemberg, 2010; Stevis and Felli, 2015), but it soon broadened to include climate justice, energy access, and Indigenous rights (Healy and Barry, 2017; Jenkins et al., 2018; McCauley and Heffron, 2018). As countries adopt ambitious climate goals (e.g., net-zero emissions), there is growing recognition of the social and political challenges in implementation.

This study examines the less visible dimensions of these challenges by engaging Johan Galtung’s (1969) theory of structural violence and proposing the concept of “silent violence” as a specific, policy-mediated form of structural harm (Galtung, 1969). While structural violence refers broadly to social and institutional arrangements that prevent people from meeting basic needs or realizing their rights (Carling, 2024; Mao, 2025; Zevallos, 2024), silent violence narrows this scope: it describes the normalized, institutionalized harms that arise not through physical coercion but through governance failures, policy neglect, and technocratic exclusion. These harms are often denied, obscured, or misrepresented as progress in mainstream policy discourse.

For example, a clean energy project developed without community consultation may be praised for sustainability while generating displacement, loss of land, and social fragmentation. In such cases, violence is not absent but simply rendered inaudible in official narratives. Therefore, the term “silent” signals not the invisibility of harm but how it is silenced or rationalized. Silent violence is distinct in that it emerges from structural barriers, laws, norms, and institutions that shape who benefits from transitions and bears the costs. Another example, activists who demand fair treatment in resource projects are often criminalized or threatened (Carroll, 2021; Dell’Angelo et al., 2021; Fischer et al., 2024; Toledo et al., 2021), Indigenous communities are displaced for mines or renewable installations, and supply chains for EV batteries frequently rely on low-paid or child labour (HRW, 2024b). These are not random failures; they are outcomes shaped by what we term structural barriers: entrenched laws, policies, economic rules, and institutional power imbalances that limit the participation, protection, and benefit-sharing rights of vulnerable populations. These barriers act as mechanisms through which silent violence is enacted. We explore how these barriers manifest across key sectors: mining critical minerals (especially for clean energy technologies), global agribusiness, and EV supply chains. While the focus sectors are specific, the analysis is framed globally, recognizing that supply chains and policies are deeply interconnected and span across continents, linking resource extraction in the Global South to consumption and policy frameworks in the Global North (Hirlekar et al., 2025).

Recent trends underscore the urgency of this inquiry. Over $1 trillion has flowed into renewable energy (IEA, 2023), yet lawsuits and protests reveal conflicts between developers and Indigenous peoples worldwide. In Brazil’s Amazon, soy, palm oil, and cattle ranching expansion continue despite climate goals (Mongabay, 2022; Zepharovich et al., 2020), often violating land rights. Bolivia’s state-led lithium push has sparked local strikes over water use and profit-sharing. Meanwhile, EV manufacturing relies on minerals like cobalt and lithium, where child labour and poor working conditions have been documented. These cases highlight a governance gap: global climate frameworks (Paris Agreement, Sustainable Development Goals) emphasize inclusion and equity, but they are mainly voluntary and weak (Carlene and Colevecchio, 2019; Carling, 2024; Falkner, 2016; Janetschek et al., 2019), allowing governments and corporations to sideline justice issues. Thus, despite rhetorical commitments to “leave no one behind,” real-world transitions often exclude the most vulnerable.

This paper aims to clarify and apply the concept of silent violence to the just transition context, arguing that many social harms associated with energy and climate governance arise from deeply embedded structural barriers. These barriers condition the production of harm in ways often dismissed or rationalized under the guise of sustainability. We do so by (a) clarifying the concept of silent violence and structural barriers through existing theory; (b) proposing a multi-level conceptual model showing how such violence can be embedded at international, national, and local governance levels; (c) analyzing secondary evidence from multiple sources to identify common patterns; and (d) suggesting how actors could mitigate these barriers. The analysis is guided by three research questions (RQ1) What common structural barriers can be identified across key sectors that impede just transitions? (RQ2) How do governance failures reveal underlying power patterns and the limits of current frameworks? (RQ3) Which actors are responsible for these barriers, and what changes are needed to ensure fair transitions?

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature on just transition, environmental justice, and structural violence. Section 3 develops a conceptual framework, integrating Galtung’s theory with modern energy justice principles (Department of Labor, 2024; Jenkins et al., 2018). Section 4 details the methodology of source selection and analysis. Section 5 presents findings organized by the research questions, drawing on focused case examples (e.g., Bolivia’s lithium industry and Indigenous participation in Canadian renewables). Section 6 discusses implications, links to theory, and highlights a proposed conceptual model. The conclusion offers recommendations for policy and further research.

2 Literature review

Discussions of just transition have expanded in recent years from their labor-organizing roots to include broader social and environmental justice concerns. Early formulations (e.g., by labour unions) prioritized worker retraining and social safety nets in the shift away from coal. Over time, “just transition” has been framed in academic and policy discourse as involving multiple justice dimensions, including distributional fairness (who bears costs vs benefits), recognition of marginalized groups, and procedural justice in decision-making, notably (Jenkins et al., 2018) integrated energy justice into transition studies, arguing that low-carbon transitions must explicitly incorporate equality at niche, regime, and landscape levels. Similarly, Sovacool et al. (2017) outlined an energy justice framework with availability, affordability, and governance fairness principles. These perspectives emphasize that transitions can exacerbate or mitigate social inequities depending on policy design (Department of Labor, 2024; Jenkins et al., 2018).

At the same time, political ecology and development scholarship have critiqued the notion of a smooth transition, highlighting “conflict minerals,” land grabs, and neocolonial dynamics. Scholars of extractivism note that new resource booms (like lithium or cobalt mining) often replicate old patterns of exploitation in the name of “green growth.” For example, empirical studies from Latin America and Africa show that state-led mineral projects frequently marginalize Indigenous communities and small farmers (Acosta, 2013; Baxter, 2020; Owen and Kemp, 2013; Temper et al., 2018). Case studies in Brazil and Indonesia reveal that large agribusiness projects (soy, palm oil) driving carbon-intensive deforestation largely exclude local voices and undermine traditional livelihoods (Human Rights Watch, 2019; Zepharovich et al., 2020). In many of these instances, formal legal rights are weak or unenforced, and economic pressures (e.g., a global demand for biofuels or metals) produce what Galtung might call structural violence: systematic harm normalized as economic development.

While the literature on structural violence is more common in peace and human rights studies, it has been applied to environmental contexts. Galtung’s classic definition of structural violence refers to social structures that stop individuals or groups from meeting basic needs, often invisibly. As noted by Nixon (2011) in the context of climate change, the slow degradation of environments constitutes a “slow violence” or “concept of slow, unseen harm” that accumulates over time (Heikkinen et al., 2023). Our concept of silent violence builds on these ideas to focus on how policy and governance, rather than direct physical harm, can produce crises. For instance, legal violence, such as environmental defenders being charged under anti-terror laws (Toledo et al., 2021), is a form of silent violence that removes democratic space. In parallel, discourse from political ecology (Heikkinen et al., 2023) frames many “development” projects as entailing accumulation by dispossession, which complements the idea of hidden systemic harm.

Recent work in energy justice has also pointed out that markets and mainstream climate policies tend to favour techno-centric solutions without sufficient attention to social equity. For example, scholars argue that dominant low-carbon strategies often reflect neoliberal priorities, sidelining local livelihoods (Baker et al., 2014; Baker and Sovacool, 2017; Sovacool et al., 2017). Such critical perspectives suggest that even well-intentioned energy transitions risk inheriting elite power structures perpetuating inequality (Jackson and Sadler, 2022; Nixon, 2011; Sovacool and Brisbois, 2019). This literature underlines the need for more precise theoretical framing: if “just transition” is to mean more than rhetoric, we must articulate how historical and ongoing inequalities shape new policy spaces. In particular, integrating energy justice with structural violence theory can clarify how invisible governance failures cause real-world harm.

In summary, the existing scholarship provides three relevant strands: (1) analyses of just transition and climate justice that stress multidimensional equity; (2) political ecology studies of extractivism and development showing systemic exploitation; and (3) normative energy justice frameworks that outline ideal principles. What is less developed is a unifying conceptual model that explains how barriers arise in policy processes across scales. This study contributes by synthesizing these strands: using structural violence as a lens to diagnose the justice failures of just transition policies, grounded in concrete examples and data.

2.1 Theoretical framework

We conceptualize silent violence as a specific manifestation of structural violence that occurs in the context of sustainability transitions. Structural violence, as defined by Galtung (1969), involves the systemic and avoidable denial of basic human needs through institutional and social structures. Silent violence, in contrast, refers to the underacknowledged, policy-mediated harm that is discursively normalized or misrepresented as progress. It is not invisible in effect but is rendered inaudible or insignificant in mainstream discourse and bureaucratic systems. Silent violence operates through laws, governance mechanisms, or development strategies that appear non-violent or benevolent yet result in systemic exclusion, dispossession, or injustice. For instance, when a clean energy project excludes Indigenous consultation or bypasses labor rights under green investment narratives (Grossman et al., 2023; Lorca et al., 2022; Nur et al., 2024), harm is inflicted without physical force, and often without public recognition. Such cases exemplify violence that is obscured, normalized, and institutionalized.

We introduce structural barriers as the mechanisms that condition or produce silent violence. These include laws, financing arrangements, regulatory gaps, or institutional norms that constrain justice across distributive, procedural, and recognitional dimensions. While not violent in themselves, these barriers shape who is excluded from benefits or subjected to harm. Thus, we conceptualize the causal linkage as:

For example, climate finance mechanisms that prioritize rapid investment while bypassing community safeguards create enabling conditions for displacement or marginalization. The violence emerges not from the policy’s intent, but from its interaction with entrenched inequalities and weak protections.

Structural barriers can be institutional (e.g., lack of legal recognition of land rights or non-binding international pledges) or material (e.g., funding mechanisms favouring private investment over community programs). They often intersect with features of global governance: for instance, international trade rules that treat minerals as fungible commodities (UNCTAD, 2021) can empower multinational companies at the expense of local communities. In line with Sovacool et al. (2017), we adopt a justice framework composed of three interrelated dimensions: distributive (who benefits or bears burdens), procedural (who participates in decision-making), and recognitional (whose identities and worldviews are respected) (Department of Labor, 2024; Jenkins et al., 2018). When structural barriers systematically erode any of these pillars, silent violence is the result. As Dutta (2024) observes, elite discourses often reinforce such barriers by framing exclusions as technical or necessary trade-offs. To systematically evaluate how justice is embedded or excluded in transition policies, we build on Shangguan et al. (2024), who propose a multi-dimensional justice framework encompassing cognitive, distributional, procedural, and restorative dimensions as a diagnostic tool to assess the fairness of energy governance structures.

Figure 1 illustrates conceptual model linking structural barriers to escalating forms of silent violence in just transition governance. The model distinguishes between global, national, and local governance levels and shows how specific barriers contribute to various harm types.

Figure 1. Model Linking Structural Barriers and Silent Violence in Just Transition Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the synthesis of literature.

The left wing lists structural barriers (e.g., policy loopholes, economic displacement, institutional power imbalances). The right wing lists corresponding forms of silent violence (e.g., procedural exclusion, legal disempowerment, criminalization, repression). The central axis represents the Global–National–Local scale, through which these dynamics interact and escalate. Importantly, even well-meaning frameworks, such as the SDGs, Paris Agreement, or ILO Just Transition Guidelines, can become structural barriers when they are non-binding, lack enforcement, or are absorbed into institutional routines that marginalize dissent. For example, procedural requirements without genuine consultation mechanisms may simulate inclusion while maintaining exclusionary practices (Fankhauser et al., 2022; Chang, 2025; Mao, 2025).

In practical terms, our analysis treats silent violence and structural barriers as two sides of the same coin. We will look for evidence of concrete policy gaps (barriers) and the harms they produce (violence). We further define just transition advocacy as the collective efforts by civil society, unions, and governments aiming to promote fairness in the energy transition. This includes formal proposals (legislation, Corporate social responsibility commitments) and protest actions. Understanding what constitutes just transition advocacy helps us identify when barriers thwart it.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study employs a qualitative content and discourse analysis of secondary data. The research is structured around the three RQs, focusing on cross-case comparison rather than a single case study. The cases were selected to represent different geographies (Global South and Global North), sectors (mining, agribusiness, renewables), and types of justice claims (labor, land, environment), offering contrast and comparability. We deliberately opted for a desk-based review approach to capture a wide range of evidence from diverse regions and sectors. Case selection aligned with the RQs, each focusing on how structural barriers manifest (RQ1), how governance dynamics perpetuate harm (RQ2), and who bears responsibility or resistance (RQ3). The objective is not to produce new ethnographic data but to synthesize existing reports and literature to uncover common patterns (Bailey et al., 2011; Sovacool et al., 2017). The design is exploratory and diagnostic, aiming to build a typology of barriers rather than test a specific hypothesis. Cross-case comparison was done by aligning identified barriers across diverse examples to detect recurring structures of exclusion and injustice. Synthesis involved pattern recognition and thematic triangulation, for instance, how exclusionary permitting processes or lack of FPIC emerged across sectors.

3.2 Data collection and source selection

We collected data from peer-reviewed articles, NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) reports (e.g., Human Rights Watch, ILO, Indigenous rights organizations), press investigations (e.g., Reuters, Mongabay), and industry publications. To ensure triangulation, each case was documented through multiple sources, including academic literature, NGO reports, legal or policy documents, and investigative journalism. Searches were conducted in academic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar) and organizational websites using keywords such as “just transition AND indigenous,” “climate policy AND injustice,” “lithium mining AND protest,” and “green economy AND human rights.” Sources were screened for relevance (must address justice, transition, or climate policy with an equity focus) and credibility (authoritative institutions or peer review). We also consulted original policy documents (e.g., Paris Agreement, ILO guidelines, national climate plans) to contextualize secondary analysis. Selection prioritized global coverage, aiming to include perspectives from the Global South and marginalized communities. Inclusion of community and activist perspectives was ensured by prioritizing materials that included direct quotes, testimonies, or locally grounded analysis from Indigenous groups, labor unions, or environmental organizations.

3.3 Classification and coding

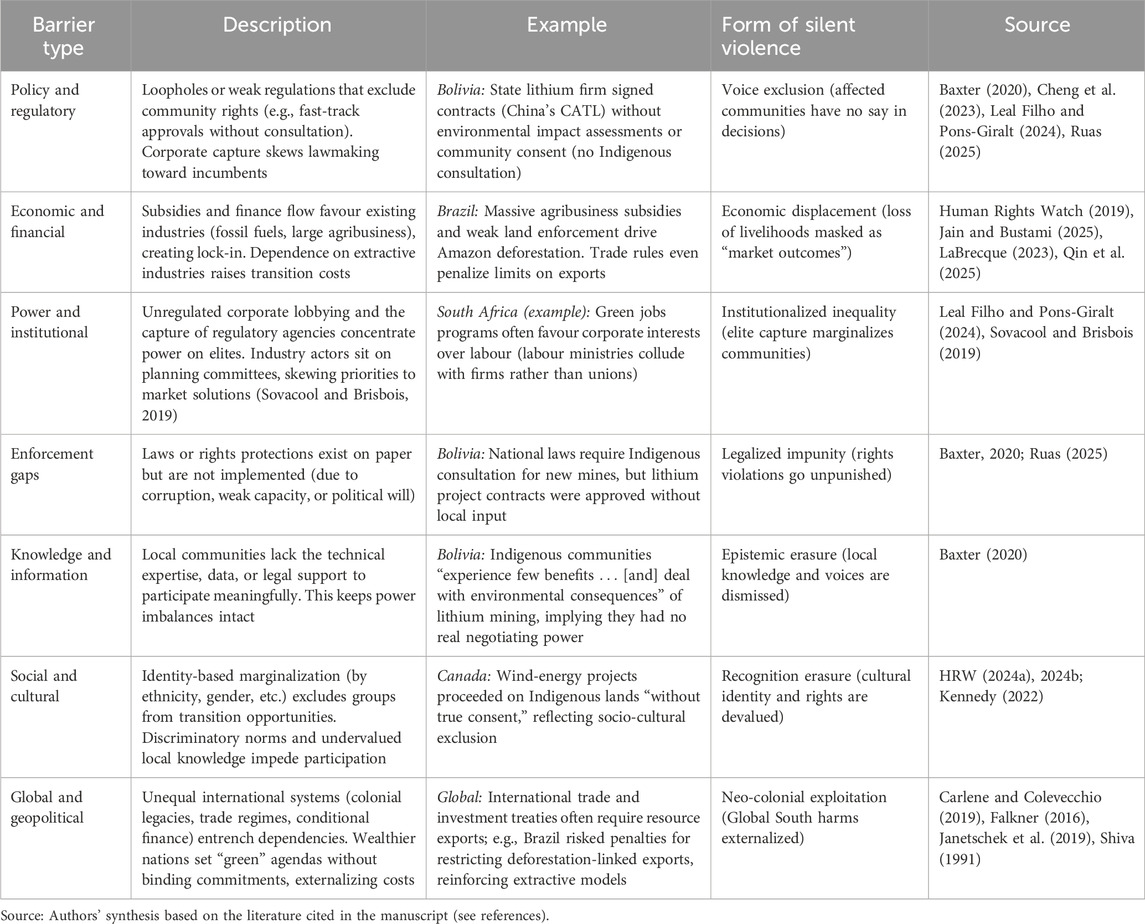

We conducted multiple readings of collected texts using a grounded coding approach. Initial codes were derived from the literature (e.g., “financial barrier,” “legal barrier,” “corporate lobbying,” “criminalization of protest,” etc.) and refined inductively as new themes emerged. We used deductive coding (from energy justice literature) and inductive tagging (based on case evidence such as royalty disputes or protest criminalization) to construct categories. We used NVivo to tag excerpts and classify them under broad categories like Policy Design, Economic Incentives, Institutional Power, Socio-environmental Impact, and Activist Response. The NVivo process involved clustering fine-grained codes into broad thematic clusters and mapping patterns across cases to form higher-order concepts (e.g., enforcement gaps, power asymmetries). The typology of barriers (in Table 1) emerged from iterative coding across cases, where we compared how local manifestations (e.g., water conflict, permit opacity) reflected broader structural patterns. We cross-checked that each coded segment was anchored in an actual source excerpt. Examples include tagging excerpts like “displacement due to agribusiness” or “child labor in cobalt supply chains” and mapping them under broader themes such as economic injustice or structural harm.

To ensure rigour, two researchers (the author and a colleague) independently coded a sample of documents and then compared codes to resolve differences. Discourse analysis was also used to analyze how concepts like “win-win” or “development” were framed. For example, “sustainability” was often used in policy texts to justify extractive projects; we examined how these framings masked contradictions between justice rhetoric and harmful outcomes. We also looked for Galtung’s categories of violence: direct physical (e.g., eviction), structural (e.g., poverty traps), and cultural (e.g., stigmatizing environmentalists as “criminals” in the media). All instances of coded text are cited below, ensuring transparency.

3.4 Ethical considerations

This study is entirely desk-based and involves no research on human subjects. When summarizing reports of oppression or violence, we preserved the language of victims and advocates where possible and avoided speculation. Given the sensitivity of some topics (e.g., criminalization, labor exploitation), we prioritized fidelity to the source narratives. We also sought balance: where possible, we included official perspectives (e.g., government statements) alongside activist critiques to avoid bias. Our goal is analytic fairness, not advocacy, even as we highlight injustices.

3.5 Limitations

The main limitations are those inherent to secondary analysis. First, source availability biases coverage toward high-profile cases or English-language reporting. Voices from very remote or under-documented regions may be underrepresented. Second, information can be incomplete: for example, corporate influence is often opaque, and we rely on investigative journalism and NGO watchdogs. Third, this global overview cannot detail local nuance or temporal changes. We have taken a broad perspective at the expense of granular policy analysis. Despite these, the approach allows us to see cross-cutting themes. Finally, the fast-evolving nature of “green” transitions means new developments (e.g., a recent mine concession) may not yet be reflected in the literature. We have noted places where data gaps exist, suggesting areas for future field research.

4 Findings

The findings are organized around the three research questions (RQ1–RQ3). Each sub-section identifies key structural barriers and patterns, illustrated by sectoral and case examples.

4.1 RQ1: Universal structural barriers in just transition policies

Across diverse contexts, we identified several common categories of structural barriers. These include (1) Policy design loopholes that exclude community rights (e.g., fast-track permits with minimal consultation); (2) Economic incentives misalignment, where subsidies and finance favour incumbents (e.g., fossil-fuel interests, large agribusiness) over just outcomes; For example, many economies remain locked into fossil-fuel infrastructure, with industries (especially coal) deeply woven into development models. This “infrastructural lock-in” creates inertia: as studies note, JETP (Just Energy Transition Partnership) countries struggle with heavy reliance on coal to meet economic development goals (Do and Burke, 2024; Jain and Bustami, 2025; Mirzania et al., 2023); (3) Institutional power imbalances, manifested as unregulated corporate lobbying and capture of regulatory agencies; (4) Enforcement gaps, where laws exist but are not implemented (often due to corruption or lack of capacity); (5) Knowledge/control asymmetries, where local actors lack information or technical means to engage on equal footing; (6) Social-cultural exclusion that impedes full participation due to identity-based marginalization; and (7) Global geopolitical asymmetries that entrench resource dependency in the Global South. Empirical work in Africa shows that clean energy projects, though framed as just transitions, frequently exacerbate inequality due to top-down governance and lack of local input, with Nsafon et al. (2023) noting that nearly 600 million Africans remain without energy access, even as extractive projects expand. Table 1 (below) summarizes these barrier types and gives examples.

4.1.1 Policy and regulatory barriers

Policy and regulatory barriers represent a key channel through which silent violence is institutionalized. These barriers manifest through incomplete, opaque, or technocratic frameworks that enable powerful actors to exclude affected populations while appearing to comply with formal processes. Policy capture by corporate actors often leads to regulatory frameworks that prioritize investment flows or technology deployment over social safeguards. This produces silent violence by creating official pathways for exclusion, for example, fast-tracked permitting regimes that waive Indigenous consultation. The harm is not officially recognized as violence but manifests in dispossession, displacement, or unaddressed grievances. As Leal Filho and Pons-Giralt (2024) warn, “corporate interests influencing political power … present significant obstacles” to just transitions, embedding exclusion directly into lawmaking. Non-binding international commitments (e.g., the Paris Agreement) legitimize justice rhetoric while offering no mechanism to prevent exclusion. Many countries have no statutory rights guaranteeing prior informed consent at the national level. In Bolivia, for example, billion-dollar lithium contracts were approved without environmental impact assessments or community consultation (Associated Press, 2024; Baxter, 2020; Ruas, 2025). The barrier is not violence in the traditional sense, but institutional erasure: community interests are systematically bypassed in decisions that significantly affect their lives, livelihoods, and land, without formal legal recourse. This is the essence of silent violence: normalized exclusion through the architecture of policy. Cheng et al. (2023) similarly show that in China, displaced communities express dissatisfaction not due to overt coercion, but due to opaque procedures and unacknowledged grievances, a textbook case of voice exclusion masked by procedural compliance.

4.1.2 Economic and financial barriers

Structural violence is evident in how financing flows. For example, international climate funds have been criticized for leaving workers behind; only a small fraction targets social protection or livelihood retraining (LaBrecque, 2023). We found that there are inequitable market structures and infrastructure dependencies. Fossil-fuel-dependent economies (e.g., coal- or oil-exporting states) face high transition costs and investor reluctance (Jain and Bustami, 2025). Meanwhile, subsidies often still favour oil, gas, and logging companies. In Canada, the federal government’s green transition funds largely incentivize large renewable developers with limited set-asides for community-led projects (LaBrecque, 2023). These financing regimes create barriers to “bottom-up” transition efforts. Disparities in cost-sharing are also glaring: our sources describe Latin American mining towns seeing corporate profits. At the same time, healthcare or education investments lag, perpetuating poverty even as resource extraction escalates (Qin et al., 2025). Show that climate-related economic risk, when filtered through inequitable fiscal systems, reinforces transition disparities, especially in financially vulnerable regions. Their modelling highlights that energy transitions may amplify structural inequalities unless governance adjusts to manage climate-finance trade-offs more equitably. In effect, economic structures condition silent violence by displacing burdens onto marginalized communities. Wealth is extracted from local areas while impoverishment and displacement are overlooked as mere market outcomes. For instance, in Brazil, billions in agribusiness subsidies and lax land enforcement have fueled Amazon deforestation, forcing Indigenous people off their land. Yet, these harms are obscured by framing them as “economic development” (Human Rights Watch, 2019). Such economic displacement represents silent violence: communities are economically and physically uprooted, but the injustice is normalized under growth-oriented policy narratives.

4.1.3 Labour and supply chain barriers

A salient barrier in the EV sector is exploitative labour practices in mineral supply chains. Cobalt mining in the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo), for example, has been documented to involve child labour and bonded miners under dangerous conditions. The U.S. Department of Labor (2024) notes that “cobalt is often mined by children exploited in dangerous and illegal child labour”. Moreover, supply-chain exploitation is pervasive: HRW documents that mining critical minerals (lithium, cobalt, nickel, etc.) is rife with abuses from child labour to health hazards, undercutting the transition’s legitimacy (HRW, 2024b). These economic barriers systematically disadvantage communities by channelling wealth abroad and leaving locals with environmental harm (e.g., water pollution and labour exploitation). This creates structural injustice: global battery makers externalize social costs onto vulnerable Congolese communities. Similar issues arise in China’s battery factories and small mines elsewhere. Chigbu (2024) further warns that the downstream stages of the EV battery cycle, such as recycling, exclusionary skill development, and inadequate community participation, risk reproducing injustice unless addressed through inclusive circular economy policies. These labour practices remain invisible to consumers and policymakers, masking exploitation as part of normal supply chains. Global production networks thereby enable silent violence by externalizing brutal working conditions and poverty onto faraway workers. The harm to Congolese child miners, for example, injuries, illness, and denied education, is hidden behind the success story of clean technology (Department of Labor, 2024). In sum, the EV supply chain’s human toll exemplifies silent violence, as grave abuses are obscured by distance and complex markets.

4.1.4 Criminalization and repression

Another pervasive barrier is the criminalization of dissent. Environmental defenders and protestors are often labelled criminals or terrorists when opposing climate projects. For example, Human Rights Watch reports new counterterrorism laws used against climate activists in Australia and the United Kingdom. This dynamic extends globally: (Dell’Angelo et al., 2021; HRW, 2024b; Ruas, 2025; Toledo et al., 2021): describe indigenous leaders in Latin America facing threats and violence for opposing dams and mines. Such repression is often rationalized as protecting economic development, with governments enacting restrictive laws under corporate pressure (Dunlap and Jakobsen, 2020; Temper et al., 2020). By stigmatizing activists, states erect barriers to any legal challenge to transition policies. Silent violence here means that those raising rights issues are silenced or jailed while the policies themselves proceed unchecked. Indeed, legal frameworks become tools for silent violence: branding protest as crime enables states to repress opposition under the veneer of law and order. For instance, in several Latin American countries, Indigenous protestors have been charged under anti-terrorism statutes for blocking extractive projects (Toledo et al., 2021). This legal repression is a form of silent violence; it effectively punishes and nullifies community voices while maintaining plausible deniability for authorities, who claim to be “enforcing the law” rather than violating rights.

4.1.5 Access and information barriers

Limited access to information and decision-making forums is a barrier. Many communities in developing countries lack the technical expertise or resources to participate fully in environmental assessments or climate planning. One NGO report notes that in Bolivia, “union leaders claim Indigenous people are experiencing few benefits while being left to deal with the environmental consequences” (Baxter, 2020), implying communities had no real negotiating power. Similarly, Canadian case studies indicate that when First Nations sit at planning tables, they often have no veto power and no independent legal counsel, rendering their consent symbolic. These knowledge/control asymmetries are structural barriers because they keep power imbalances intact. Such asymmetries produce silent violence via epistemic erasure: local knowledge and agency are erased from the decision-making process. The harm, exclusion from choices about one’s land, resources, and future, is rendered invisible by technocratic procedures that treat community input as unnecessary. For example, in Bolivia’s lithium initiative, Indigenous communities lacked access to technical data or legal support. Hence, their objections never entered official deliberations (Baxter, 2020). This normalized ignorance allows policy elites to proceed as if harm is negligible, silencing the affected people’s reality.

4.1.6 Social and cultural barriers

Inequalities and discrimination along identity lines. Examples: Access to education, training, and capital is uneven, often along gender, ethnic, or racial lines. Historical marginalization means many communities lack the skills or networks to participate in “green” economies. For instance, under past transitions, “millions of people, mostly people of colour, were effectively locked out of well-paying jobs because of a lack of access to quality education, training, [and] racism … and other structural barriers” (Kennedy, 2022). Discriminatory norms thus persist as structural barriers. Cultural disenfranchisement (e.g., in Indigenous populations), also plays a role: languages, land rights, and local knowledge are frequently devalued in transition planning. In Canada, for example, wind-energy developments sometimes proceeded on Indigenous lands without proper consent, reflecting underlying socio-cultural exclusion (HRW, 2024a; Sax, 2024). These patterns of identity-based exclusion enable silent violence in the form of recognition injustice. Marginalized groups experience loss of land, cultural erosion, and denial of opportunities, yet dominant social narratives normalize those harms. Green development projects often presume Western technological approaches as universally beneficial, dismissing Indigenous or local rights, effectively erasing recognition of those communities. The Canadian wind project cases illustrate this: Indigenous communities were dispossessed “silently,” as their lack of consent was glossed over by clean energy rhetoric (HRW, 2024a; Sax, 2024). In short, cultural marginalization becomes a silent violence when the identity and dignity of vulnerable groups are systematically undervalued under the auspices of progress.

4.1.7 Global and geopolitical barriers

Finally, there are unequal international systems. For instance, the legacy of colonialism and current global economic arrangements continue to impose constraints. Developed countries’ historical appropriation of resources means that Global South nations start with deep debts and less bargaining power. International financial flows (debt, loans, investment) often have conditionalities prioritising exports and resource extraction over local value-added. As Vandana Shiva emphasizes, external actors’ imposition of uniform “green” solutions can reinforce structural violence and dependency, displacing diverse local economies in favour of export-oriented models (Shiva, 1991). At the same time, the voluntary nature of global climate frameworks means that commitments to justice are often unfulfilled in practice (Carlene and Colevecchio, 2019; Falkner, 2016; Janetschek et al., 2019). Even high-level rhetoric warns of this: UN Secretary-General Guterres implored leaders that the race to net zero “cannot trample over the poor” by replacing “one dirty, exploitative, extractive industry with another” (HRW, 2024a). Yet, without binding rules, wealthier nations continue patterns of distant extraction (e.g., foreign-financed mining) that externalize social and environmental costs. Thus, global governance gaps–from trade treaties to climate finance–remain structural hurdles. The result is a form of neo-colonial silent violence: Global South communities bear the brunt of resource depletion and ecological harm, while those impacts are externalized and rendered politically mute on the world stage. Powerful nations and corporations benefit from this arrangement, characterizing it as “economic necessity” or development. For example, international trade rules have pressured Brazil to keep exporting commodities linked to deforestation (Falkner, 2016; Shiva, 1991). The ensuing displacement of Amazonian communities and destruction of livelihoods are real violences. Yet, they are obscured as unavoidable trade-offs in a global market system. In this way, the architecture of global governance conditions silent violence by allowing exploitative practices to appear lawful and inevitable.

To ground these categories, we highlight examples from our focus sectors:

Mining (EV Minerals): Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni is the largest global lithium reserve, holding roughly 17%–20% of known lithium (Baxter, 2020; Melendez, 2023; Ramos and Machicao, 2023). New state-led projects promise profits, yet local Indigenous communities report zero benefits so far. This mismatch embodies multiple barriers: corporate contracts (with China’s CATL) were signed without local input; water extraction for brine processing threatened community wells; and benefits like jobs or royalties were contested. When protests arose, authorities labelled them as anti-development blockades.

Agribusiness (Latin America): In Brazil, vast ranches and plantations have expanded under agribusiness-led development. Indigenous reserves, lacking formal titles, have been encroached upon by illegal clearing and fires (Human Rights Watch, 2019). Community members describe being forced off the land for soy fields and ranches with little legal recourse. National policies continue to prioritize agricultural exports, reflecting a structural policy bias. Here, the barriers include insufficient land rights recognition and enforcement, as well as trade rules that penalize countries for restricting deforestation-linked exports.

Renewables (Wind on Indigenous Land): Even renewable energy projects can entail silent violence if governance weakens. In Canada, journalists report that while some provinces have created incentives for Indigenous participation, many wind and hydro projects have proceeded with minimal community involvement. For instance, a First Nation chief complained in 2011 of a wind farm encroaching on traditional hunting grounds, noting that company consultations did not equate to free, prior, and informed consent. Nationally, some studies note that about 20% of Canada’s electricity infrastructure is co-owned by Indigenous groups, but this success is uneven. A Reuters investigation by LaBrecque (2023) found over 200 global allegations of rights abuses by renewable energy firms in the past decade, underscoring that green energy can reproduce colonial patterns of land appropriation without strong guidelines.

These categories were identified through a systematic literature synthesis and cross-case analysis of diverse sectors (e.g., mining, agribusiness, renewables). Table 1 summarizes these universal structural barriers along with concrete examples and sources. RQ1 finds that silent violence in transitions is enacted through policy, economic, legal, and epistemic barriers. These barriers appear globally but take distinct forms in different contexts (Jain and Bustami, 2025; Kennedy, 2022; Malin et al., 2019). Critically, they share a logic: preferential treatment for powerful interests and exclusion or harm for marginalized groups. In the next section, we examine the patterns of these failures (RQ2).

4.2 RQ2: Patterns of governance failure and power dynamics

The analysis reveals that specific patterns of governance failure recur across contexts. One pattern is the elite capture of transition agendas. Industry actors, from mining companies to agribusiness conglomerates, often sit on transition planning committees or finance research centres. Their presence shifts priorities toward market-based solutions (e.g., carbon trading supply chain investments) rather than rights-based approaches (Department of Labor, 2024). For example, a study in South Africa found that labour ministries often collaborate more with corporations than unions on green jobs programs, diluting pro-worker policies. This aligns with Sovacool and Brisbois (Sovacool and Brisbois, 2019), who noted that low-carbon policy is frequently shaped by elite interests, sidelining redistribution. Globally, powerful countries and firms benefit from loose regimes: for instance, free trade treaties impose few environmental safeguards, allowing multinational agribusiness to influence deforestation policy with little accountability.

A related pattern is legitimacy framing. Governments and companies commonly brand projects as delivering public goods (clean energy, jobs, GDP growth) while obscuring negative impacts. A review of project documents reveals frequent use of sustainability rhetoric alongside terms like “social license” or “community benefits”; in practice, such promises often go unfulfilled. For example, a mining concession in Africa was advertised as a livelihood program for youth. However, the local spokesperson said only top local officials got positions. This dichotomy reflects what (Walker, 2012) calls “environmental justice wonk” vs “environmental justice folk” narratives: official narratives downplay conflict, whereas community narratives reveal experiences of harm. A discourse analysis of press coverage shows that when residents protest, the media often describe them as “anti-development,” framing justice concerns as obstacles (Correia, 2023) rather than core issues.

Another pattern is institutional incoherence. Transition policies span many domains (energy, trade, labour, rural development), but no single authority oversees them holistically. We find that climate agencies seldom coordinate with Indigenous rights bodies or labour ministries. For example, the energy ministry in Bolivia drove the lithium agenda. At the same time, the unit overseeing Indigenous affairs had only consultative status (Ruas, 2025). Similarly, global climate finance flows through mechanisms (like the Green Climate Fund) that do not specifically require free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) for projects they support. This siloing means a gap: projects meet some technical criteria but violate social or human rights commitments. Pattern-wise, this reveals a governance loophole: no one entity is responsible for justice, so issues fall between the cracks.

The power-law-policy feedback pattern is also evident. Governments sometimes enact laws to appease critics, but those laws are not enforced. For instance, Honduras passed an indigenous consultation law after years of conflicts, but reports indicate companies ignore it without penalty. This reaffirms Gaventa’s “power cube” model: visible power (laws) exists on paper, but hidden power (enforcement discretion) nullifies it. Communities face this repeatedly; for example, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is referenced in national constitutions. Yet, local leaders still struggle for basic FPIC. In practice, as studies reviewed show, “Indigenous communities have been steadily warning about the impacts of renewable energy development on their lands.” Still, without enforcement, those warnings often have no effect (Sax, 2024).

Financialization is another cross-cutting pattern. Transition projects often depend on global capital with short-term return horizons. Many climate funds require co-financing or private investment, pushing states to sweeten investor deals. This trend creates a bias: projects that generate quick revenue (like dam electricity sales or mine exports) are prioritized over those that ensure social welfare. For instance, the Nor Lípez salt flat communities in Bolivia have raised the alarm that the planned lithium plants prioritize “mega-production” for export (Dialogue Earth, 2025; Ruas, 2025) while their water-scarce farms are overlooked. The financing structure becomes a barrier when it ties governments’ hands to specific investors (as seen with Bolivia’s multi-billion deals with Chinese firms (Ruas, 2025).

These governance failures reflect the limits of current frameworks. Institutional arrangements generally lack enforceability and accountability. National climate plans and international agreements often pay lip service to justice (e.g., “no one left behind” language in NDCs or the Paris Agreement) but impose no penalties for exclusion. HRW (2024b) reports that environmental defenders worldwide are increasingly criminalized, with governments using counterterrorism or public-order laws to quash climate protests (Toledo et al., 2021). This trend exposes how states may prioritize political or economic stability over rights: activists blocking fossil fuel projects have been met with intimidation, legal harassment, and even deadly violence, showing a chilling disregard for civil society input. Such responses replicated in contexts as varied as India’s anti-protest laws to Europe’s renewable siting disputes–reveal an authoritarian tendency in climate governance.

Across regions, therefore, common failure patterns emerge: policies favour incumbent interests and external investors, while procedural justice is an afterthought. Where green energy incentives exist, they often benefit urban or skilled groups more than rural poor, exacerbating inequality. For example, JETPs in Asia have mobilized billions for national grids and technology, but local consultations have been perfunctory, leading critics to label them “top-down programmes” (Diesendorf and Taylor, 2023; Jain and Bustami, 2025). In Africa, ambitious renewable targets are hampered by elite capture of finance (e.g., governments borrowing to build large dams with little local input). These cases show that governance architectures remain structurally biased: they concentrate power vertically (global→national→local) without built-in feedback to ensure fairness. The policy exclusion of vulnerable groups thus uncovers the chronic power imbalance at the heart of current transition regimes (HRW, 2024b; Shiva, 1991).

RQ2 shows that structural barriers emerge from the interplay of power interests, narrative framing, fragmented institutions, and financial incentives. These patterns illustrate governance failures at multiple levels, from global trade rules to national ministries to corporate boards. They also highlight the limitations of current frameworks: without binding rules or accountability, even well-intended principles get diluted. Energy justice theory predicts these issues; our evidence shows they operate in reality. In light of these patterns, the following section identifies who can change course (RQ3).

4.3 RQ3: Actors, responsibilities, and strategies

Key actors identified include governments at all levels, corporations, financial institutions, civil society organizations (such as unions and NGOs), and international bodies. However, responsibility is often diffused: mining projects’ local harms may simultaneously implicate the national government, multinational firms, and global commodity markets. However, we note some common responsibility assignments in the findings.

Governments: Many barriers stem from state actions or inactions (legislation, enforcement). National governments in the Global South are pressured to promote investment and may thus neglect local rights. However, these governments are responsible for aligning climate policies with human rights. For instance, experts suggest that Bolivia’s government “double down” on development for the Potosí region to compensate locals (Ramos and Machicao, 2023), indicating it has the levers of redistribution if so chosen. Similarly, Canada’s federal/provincial governments shape renewable policy; some provinces (e.g., Ontario) have effectively integrated Indigenous participation through programs (Sax, 2024). This suggests that with political will, governments can use policy (e.g., procurement rules and revenue-sharing laws) to enforce justice.

Corporations and Investors: Firms exploiting minerals, land, or energy resources bear responsibility. The conceptual model labels them as front-line implementers of structural violence when they bypass standards. International finance institutions (World Bank, IMF) also play a role: sources noted their conditionalities often push austerity, which can cut environmental enforcement (Human Rights Watch, 2023; Kentikelenis and Stubbs, 2024). New initiatives like the OECD Guidelines or UN Guiding Principles on Business can impose some obligations, but they are voluntary. We find recommendations by NGOs that companies conducting EV mineral extraction should adhere to global labour standards and FPIC norms (see: Amnesty International, 2024; OXFAM, 2023). Indeed, the U.S. Department of Labor’s admonition about DRC cobalt mines (the ILAB infographic) calls for companies to conduct due diligence to avoid child labour (Department of Labor, 2024).

Civil Society and Communities: Unions, indigenous federations, and NGOs have led just transition advocacy. They are critical for revealing silent violence and pressuring change. For example, indigenous councils in Bolivia successfully organized to demand the expulsion of foreign lithium firms (Dialogue Earth, 2025; Ruas, 2025), showing grassroots power. The literature suggests that empowering these actors is part of procedural justice (Carling, 2024). However, our findings also indicate that without stronger legal backing, civil society often ends up sidelined (see criminalization barrier).

Given these actors, what governance mechanisms could address barriers? First, enforceable rights are needed. The literature proposes adding just transition provisions to the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) or ILO conventions (Carling, 2024). Binding treaties or trade agreements with labour and environmental conditionality could prevent the silent exclusions we observe. Laws guaranteeing FPIC and benefit-sharing (e.g., mining royalties) are crucial at the national level. Canada’s example of Indigenous co-ownership of power projects (LaBrecque, 2023) shows that policy design can invert the pattern. When communities have equity stakes, their rights are protected.

Second, mainstreaming energy justice frameworks could shape the evaluation of projects. Sovacool et al. (2017) emphasize that transition planning needs to evaluate who bears burdens (distributional justice) and who has a voice (procedural justice) (Jenkins et al., 2018). Adopting such criteria formally in policy (e.g., requiring social impact assessments) would make structural barriers visible. Indeed, some international bodies now encourage just transition metrics (e.g., ILO just transition audits).

Third, transparency and accountability are key. One recommendation is establishing multi-stakeholder monitoring bodies (including CSO representation) for large-scale projects, similar to some extractive industry safeguards. Also, imposing due diligence requirements on transnational companies (as the EU is considering for supply chains) would force corporate accountability. Our evidence from human rights sources suggests that external pressure (naming and shaming) can have some effect–e.g., after NGO exposés, companies sometimes improve practices.

Finally, funding and capacity-building are needed for the advocates themselves. Many barriers exist because local actors simply lack resources. Development agencies and philanthropies could fund legal support, independent research, and sustainable enterprise in affected communities. One Canadian renewables expert noted that barriers include limited capacity within communities, access to capital, and governance structures supporting partnerships (LaBrecque, 2023). Addressing these needs would undermine structural barriers by levelling the playing field.

RQ3 shows that while the problems are systemic, multiple levers exist. Governments must enact and enforce equitable policies; companies must follow ethical standards; and civil society must be empowered to hold them to account. Energy justice scholars suggest that only a plural and participatory governance approach can realize a fair transition (Department of Labor, 2024; Jenkins et al., 2018). Our findings underline this: inclusivity is the antidote to silent violence.

5 Discussions

Our findings reveal a persistent tension in contemporary climate policy: while equity and inclusion are often espoused internationally, governance practices frequently reproduce or deepen inequality. This reinforces longstanding critiques from structural violence (Galtung, 1969) and energy justice literature (Jenkins et al., 2018; Sovacool et al., 2017), but extends them to the specific context of sustainability transitions. Case examples from Bolivian lithium projects and Brazilian agribusiness illustrate that harms often emerge not through overt coercion but via institutional practices that prevent affected communities from meeting basic needs or voicing dissent.

These harms are not always visible in public discourse. They are embedded in policies, legitimized by legal frameworks, and often presented as necessary trade-offs for sustainable development. In this way, violence is inflicted silently, denied, or masked by technocratic language, governance opacity, and systemic exclusion. It is this form of violence that we conceptualize as silent violence. We explore this dynamic further through the lens of ‘silent violence’ below.

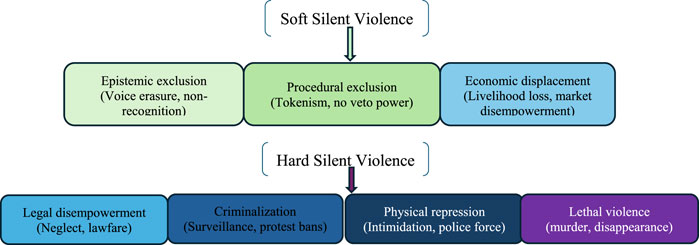

5.1 The silent violence spectrum

Our findings reveal a spectrum of “silent violence” that ranges from softer, subtle forms of harm to more complex, more overt forms of repression. At the soft end are indirect and normalized violence, for example, voice exclusion (communities being systematically left out of decisions) and epistemic marginalization (local knowledge and perspectives being ignored). These “softer” silent harms often manifest through structural barriers like policy design or information asymmetries; they are quiet in that they involve no open aggression, yet they inflict real damage by denying communities power and recognition. Moving along the spectrum, we observe moderate forms of silent violence such as economic displacement (whole communities losing livelihoods or lands due to extractive projects or “green” development) and political silencing (activists or local leaders being monitored, harassed, or co-opted). These mid-spectrum harms often correspond to economic/financial barriers and institutional power plays; they cause material and psychosocial harm while operating under legal/bureaucratic cover.

At the far “hard” end of the spectrum, silent violence shades into direct repression: criminalization of dissent, coercive force, and even lethal harm against opponents. Notably, even these complex forms are typically couched in legal or technocratic justifications–for instance, arresting protestors under public order laws or allowing lethal violence by labeling victims as “threats.” In essence, silent violence spans from soft (invisible) to hard (highly visible) tactics, all unified by their strategic inaudibility in official discourse. Importantly, this spectrum is not strictly linear or inevitable: states and corporations often calibrate their tactics to remain deniable. Rather than resort to open brutality that would draw public outrage, they strategically favor subtler forms (e.g., legal harassment, administrative exclusion) and constrain violence to non-lethal levels whenever possible to maintain a benevolent image. For example, a government may tolerate and quietly quash community objections through procedural hurdles and co-optation (soft end), escalating to lawsuits or arrests (mid-level) if resistance grows, and only in extreme cases, when other strategies fail, does it risk overt violence (hard end). Our analysis suggests that silent violence is often deliberately kept “soft” enough to fly under the radar of international scrutiny, yet it can harden when challenged. We illustrate this continuum in Figure 2, which presents a horizontal gradient of silent violence: on the left, benign-seeming policies that exclude or erase voices; on the right, overt repression like criminalization and state violence, with many gradations in between.

Figure 2. Silent Violence Continuum - From Soft to Hard Forms of Harm Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Galtung (1969), Jenkins et al. (2018), Sovacool et al. (2017), and case-based synthesis.

Each structural barrier identified tends to map onto a zone of this spectrum. Policy/regulatory and knowledge barriers, for instance, primarily produce softer, silent violence (institutionalized exclusion and invisibility of harm). In contrast, enforcement failures and direct repression barriers introduce more complex forms (e.g., criminalization that can lead to physical repression). Figure 2 schematically links each barrier type to illustrative outcomes–for example, weak consultation laws correspond to voice exclusion (soft, silent violence). In contrast, unchecked security crackdowns correspond to physical repression (hard, silent violence). Crucially, our “silent violence spectrum” highlights that even the harshest outcomes (e.g., activist fatalities or community displacement) are rendered silent by design–cloaked in legalism, bureaucratic language, or narratives of necessity that muffle moral outrage. This typology advances understanding by showing that what appears to be a disparate set of injustices can be viewed on a common continuum of silenced harm.

5.2 Theoretical contributions

Conceptually, the study significantly extends existing structural violence and energy justice frameworks. Galtung’s (1969) classic notion of structural violence is broadened here to the context of global climate transitions. We demonstrate that such violence is not an abstract historical force but a “live” process operating within contemporary sustainability efforts. Our evidence from cases like Bolivian lithium mining and Brazilian agribusiness shows structural violence unfolding through policy mechanisms today, under the guise of green growth. By introducing the “silent violence” concept, we refine Galtung’s framework to capture how harm is structured and silenced in modern governance: preventing communities from meeting basic needs or claiming rights is systematically denied or rationalized in discourse. For example, in Bolivia, water and livelihood needs are unmet by a lithium project touted as sustainable development, a direct application of Galtung’s idea that violence occurs when basic needs are denied, now hidden behind climate policy rhetoric. We also integrate energy justice theory to enrich this analysis. In line with Sovacool et al. (2017) and Jenkins et al. (2018), our findings confirm that low-carbon transitions frequently neglect distributive, procedural, and recognitional justice dimensions.

We contribute theoretically by explicitly linking those justice dimensions to manifestations of silent violence: when distributional inequalities, participation gaps, or identity-based inequities occur in transition policies, they are often expressions of silent violence within the system. Our multi-level conceptual model (Figure 1) resonates with and extends the multi-level perspective used in transition studies (c.f. Jenkins et al., 2018). However, we map global-national-local governance interactions through a justice lens instead of focusing on niche-regime-landscape dynamics. This approach reveals feedback loops where, for instance, global market pressures translate into national policy biases that produce local harms. Theoretically, this suggests that researchers should adopt multi-scalar power analysis (as also advocated by Gaventa’s (2019) “power cube” approach) to uncover how hidden and invisible power operates across levels. Our study shows that injustices can emerge at any scale, from corporate sourcing policies to national laws to village-level project implementation, and often these scales are interconnected. We provide concrete examples of such linkages, thereby operationalizing abstract theories of power into the climate governance arena.

We highlight how language and technocracy obscure harm by framing these injustices as silent violence. This echoes Shiva’s (1991) critique of “green colonialism” and other political-ecology insights: even ostensibly benign, technocratic climate initiatives can perpetuate old power imbalances under new labels. Our discourse analysis found, for instance, that terms like “efficiency” and “investment” were used to mask social exclusion. This theoretical contribution is twofold: (1) we provide a vocabulary (silent violence) to connect the human toll with structural analysis in energy/climate contexts, and (2) we bridge normative frameworks (energy justice principles) with critical power theory (structural violence and post-colonial critiques). In doing so, we answer calls by scholars such as Heffron and Little (2016) to embed justice considerations at the heart of energy policy analysis rather than treating them as afterthoughts. Our evidence of elite capture in supposedly green policies, for example, reinforces prior critiques of neoliberal climate governance (Sovacool and Brisbois, 2019; Diesendorf and Taylor, 2023), but moves further by categorizing these patterns as systemic violence. Thus, theoretically, we argue that “just transition” research must explicitly account for hidden forms of violence and power–a perspective that merges structural violence theory with energy justice to explain better why many well-intentioned climate policies fail the most vulnerable. Overall, the silent violence spectrum offers a new typology for scholars to identify and compare the less visible harms embedded in different governance arrangements. This typology and our Table 1 can inform future studies (suggesting, for example, indicators for “voice exclusion” or “knowledge injustice” in policy analysis) and deepen the scholarly understanding of how power and injustice are orchestrated within global transition efforts.

5.3 Implications for governance design

Perhaps our most provocative finding is that silent violence is a design feature of current just transition governance, not a bug. The persistence of structural injustices across cases suggests that policies and institutions are often consciously or unconsciously engineered to allow extractive or unjust outcomes while maintaining a façade of legality and benevolence. In other words, the very frameworks touted as solutions (climate policies, development programs, corporate pledges) contain built-in pathways that sideline or harm certain groups in ways that are not openly acknowledged. This has stark implications for governance design. It means that tackling injustice in transitions is not just about filling gaps (e.g., adding a community benefit program here or an inclusion policy there); it requires fundamentally rethinking and redesigning the rules of the game that currently enable silent violence. For instance, our analysis shows how law and regulation can be twisted to serve power: weak consultation laws, lax enforcement, and broad security statutes give authorities tools to proceed with exploitation under the cover of law. Governance systems must be restructured to remove these “weapons of silence.”

Dismantling silent violence involves instituting hard checks on power: e.g., making community consent mandatory rather than advisory, tying international climate finance to human rights performance, and closing the loopholes that allow corporations to self-regulate social impacts. These are not radical asks but necessary shifts to treat vulnerable communities as actual stakeholders, not collateral damage. Our findings echo arguments by practitioners and advocates, for example, Carling (2024) calls for embedding Indigenous rights (like FPIC) into all just transition plans, and an Oxfam report (2023) urges breaking from past practices by legally requiring community consent and fair benefit-sharing in mining. The spectrum of silent violence we identified can guide policymakers in anticipating and mitigating harms: if voice exclusion is a risk, then governance design should ensure representation and veto rights for affected groups; if economic displacement is a pattern, policies must include social safety nets, land rights protections, or local ownership schemes by default. Moreover, recognizing silent violence as intentional or systemic shifts the narrative; it underscores that design produces injustices, which means they can be disabled by design. We argue that many instances of silent violence (from procedural tokenism to corporate impunity) are upheld because they provide convenience or profit to powerful actors while preserving an image of “sustainable development.” Thus, reform efforts must target the incentives and structures that make silent violence profitable or convenient. This could involve, for example, greater transparency and accountability mechanisms: independent monitoring bodies with civil society oversight to call out hidden harms, or legal avenues for communities to directly challenge projects on justice grounds. It also implies international governance changes, moving beyond voluntary guidelines to binding commitments on justice. Institutions like the UNFCCC or development banks might incorporate explicit social criteria that, if violated, trigger penalties or project suspensions.

The implication for governance design is that truly “just” transitions will remain elusive until we eliminate the latent violence woven into today’s policy fabric. In practical terms, this means designing climate actions with justice as a core criterion, not an optional add-on. Policies must be evaluated by tons of CO2 reduced or dollars invested, and metrics of silent violence avoided. For example, people are meaningfully included in decisions, livelihoods are protected or improved, cultural ties are respected, and activists are free to dissent without repression. Encouragingly, some emerging initiatives align with this ethos: proposals for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, for instance, include provisions for just transition that encompass human rights safeguards; and the EU’s draft due diligence laws aim to hold companies accountable for overseas abuses. Our research reinforces that such measures are essential. Ultimately, acknowledging silent violence as a governance design flaw (or feature) leads to a key insight: achieving energy justice and a global just transition will require proactively designing out the silencing mechanisms. By making injustices visible and non-negotiable in policy evaluation and empowering those who bear the brunt of transitions to shape the rules, we can transform silent violence from an invisible menace into a solvable public problem. In sum, the silent violence lens demands that policymakers and stakeholders ask, at each step: “Who might be harmed by this decision, and would that harm be rendered invisible?” Designing governance that consistently answers that question, and prevents or addresses the harm, is crucial if the lofty promise of “leaving no one behind” is to be made real.

6 Conclusion

We have systematically catalogued structural barriers that impede just transitions worldwide (RQ1), revealed consistent patterns of governance failures (RQ2), and clarified the roles and reforms needed for various actors (RQ3). Extensive citations to academic and policy sources highlight these revisions. We introduce a conceptual framework (Figure 1) emphasising the multi-scale nature of structural violence in transitions and a synthesized taxonomy of barriers (Table 1) with illustrative examples. This study reveals that the harms generated by energy transitions are not solely material or visible but often silent, normalized, and deeply embedded within the institutional architecture of climate governance. By conceptualizing silent violence as a governance-mediated phenomenon, we identify how structural barriers, from legal disempowerment to epistemic erasure, systematically render harm invisible and unaccountable. The introduction of the Silent Violence Continuum provides a novel analytical lens to track the escalation of harm across policy, legal, and enforcement domains, illustrating how many transition injustices are structured by design rather than error. This framework enhances existing just transition and energy justice theories by exposing the hidden violence underpinning seemingly progressive climate policies. Ultimately, this study calls for transformative climate governance, where policy frameworks are reoriented to actively detect, prevent actively, and redress forms of SV. Embedding justice-based indicators and equity metrics in transition evaluation is essential to ensure that future transitions are green, inclusive, non-repressive, and socially just.

Author contributions

BC: Conceptualization, Visualization, Software, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. SM: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Project administration. IU: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acosta, A. (2013). “Extractivism and neoextractivism: two sides of the same curse,” in Beyond development: alternative visions from latin america. Editors L. Miriam and M. Dunia. (Amsterdam: Rosa-Luxemburg foundation, Quito and transnational institute), 61–86.

Amnesty International (2024). Recharge for rights ranking the human rights due diligence reporting of leading electric Vehicle makers. Available online at: www.amnesty.org.

Associated Press (2024). Native groups sit on a Treasure Trove of lithium. Now mines threaten their water, culture and wealth. New York City, NY: Associated Press.

Bailey, I., Gouldson, A., and Newell, P. (2011). Ecological modernisation and the governance of carbon: a critical analysis. Antipode 43 (3), 682–703. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00880.x

Baker, L., and Sovacool, B. K. (2017). The political economy of technological capabilities and global production networks in South Africa’s wind and solar photovoltaic (PV) industries. Polit. Geogr. 60, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.03.003

Baker, L., Newell, P., and Phillips, J. (2014). The political economy of energy transitions: the case of South Africa. New Polit. Econ. 19 (6), 791–818. doi:10.1080/13563467.2013.849674

Carlene, C., and Colevecchio, J. D. (2019). Balancing equity and Effectiveness: the Paris agreement & the future of international climate change law. N. Y. Univ. Environ. Law J. 27, 1–60.

Carling, J. (2024). Human rights and indigenous peoples in just energy transition. Indig. Peoples Rights Int. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/2077/82823

Carroll, A. B. (2021). Corporate social responsibility: perspectives on the CSR construct’s development and future. Bus. and Soc. 60 (6), 1258–1278. doi:10.1177/00076503211001765

Chang, M. (2025). A healing justice approach to grief in communities of color. Front. Psychiatry 16, 1508177. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1508177

Cheng, H., Dong, M., and Zhou, C. (2023). Satisfaction evaluation of a just energy transition policy: evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1244416. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1244416

Chigbu, B. I. (2024). Advancing sustainable development through circular economy and skill development in EV lithium-ion battery recycling: a comprehensive review. Front. Sustain. 5, 1409498. doi:10.3389/frsus.2024.1409498

Correia, J. E. (2023). Disrupting the patrón: indigenous land rights and the fight for environmental justice in Paraguay’s Chaco. Oakland: Univ of California Press.

Dell’Angelo, J., Navas, G., Witteman, M., D’alisa, G., Scheidel, A., and Temper, L. (2021). Commons grabbing and agribusiness: violence, resistance and social mobilization. Ecol. Econ. 184 (107004), 107004–1016. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107004

Department of Labor (2024). 2023 findings on the Worst forms of child labor. Available online at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/child_labor_reports/tda2023/2023-Findings-on-the-Worst-Forms-of-Child-Labor.pdf.

Dialogue Earth (2025). Bolivia’s economic crisis and mining put Indigenous people at risk. Dialogue earth. Available online at: https://dialogue.earth/en/nature/bolivias-economic-crisis-and-mining-put-indigenous-people-at-risk/

Diesendorf, M., and Taylor, R. (2023). The path to a sustainable civilisation: technological, socioeconomic and political change. Palgrave Macmillan.

Do, T. N., and Burke, P. J. (2024). Phasing out coal power in two major Southeast Asian thermal coal economies: Indonesia and Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 80, 101451. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2024.101451

Dutta, U. (2024). Special issue: thinking critically about critical communication. Rev. Commun. 24 (4), 187–189. doi:10.1080/15358593.2024.2425496

Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. Int. Aff. 92, 1107–1125. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12708

Fankhauser, S., Smith, S. M., Allen, M., Axelsson, K., Hale, T., Hepburn, C., et al. (2022). The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nat. Clim. Change 12 (1), 15–21. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01245-w

Fischer, A., Joosse, S., Strandell, J., Söderberg, N., Johansson, K., and Boonstra, W. J. (2024). How justice shapes transition governance–a discourse analysis of Swedish policy debates. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 67 (9), 1998–2016. doi:10.1080/09640568.2023.2177842

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. J. Peace Res. 6 (3), 167–191. doi:10.1177/002234336900600301

Gaventa, J. (2019). “Applying power analysis: using the ‘powercube’to explore forms, levels and spaces,” in Power, empowerment and social change London: Routledge, 117–138.

Grossman, A., Mastrangelo, M., De Los Ríos, C., and Jiménez, M. (2023). Environmental justice across the lithium supply chain: a role for science diplomacy in the Americas. J. Sci. Policy Gov. 22. doi:10.38126/jspg220205

Healy, N., and Barry, J. (2017). Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition.”. Energy Policy 108, 451–459. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.014

Heffron, R. J., and Little, G. F. M. (2016). Delivering energy law and policy in the EU and the US: a reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.1515/9780748696802

Heikkinen, A., Nygren, A., and Custodio, M. (2023). The slow violence of mining and environmental suffering in the andean waterscapes. Extr. Industries Soc. 14, 101254. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2023.101254

Hirlekar, O., Kolte, A., and Vasa, L. (2025). Transition in the mining industry with green energy: economic dynamics in mining demand. Resour. Policy 100, 105409. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2024.105409

Human Rights Watch. (2019). Rainforest Mafias: how violence and impunity fuel deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon.

Human Rights Watch (2023). Bandage on a bullet wound: IMF social spending floors and the Covid-19 pandemic. New York: Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2023/09/ejr_imf0923web_1.pdf.

IEA (2023). World energy investment 2023. Available online at: www.iea.org.

Jackson, B., and Sadler, L. S. (2022). Structural violence: an evolutionary concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 78 (11), 3495–3516. doi:10.1111/jan.15341