- School of Economics and Management, Northwest University, Xi’an, China

Introduction: Integrating debt risk mitigation and carbon reduction is essential for superior economic development.

Methods: The study has selected panel data from 274 Chinese cities from 2009 to 2020 as the research sample. The 2015 Local Government Debt Governance (LGDG) is employed as an exogenous policy shock to examine the impact of LGDG on carbon emissions through the intensity difference-in-difference method (IDID).

Results: Research findings indicate that after implementing LGDG policies, each city in the treatment group achieved an average reduction in carbon emissions of 1.1851 tonnes per capita compared to the control group. The conclusions remain robust after applying various tests, including stepwise regression, parallel trend tests, placebo tests, substitution of core variables, controlling for contemporaneous policies, changing the estimation method and using instrumental variables. Mechanism analyses show that LGDG achieves carbon reduction by reducing ’land resource mismatches’ and ’economic infrastructure investments.’ Heterogeneity analysis indicates that when marketization is relatively high, economic development pressures are low, environmental regulations are stringent, and geographical location is in the central and western regions, LGDG has a more pronounced effect on reducing carbon emissions.

Discussion: The research findings offer feasible pathways for coordinated governance of implicit debt risks and carbon emissions, providing practical insights for achieving carbon peaking and neutrality goals.

1 Introduction

As of June 2024, the global average temperature has broken the record for 13 consecutive months1. Climate change caused by carbon dioxide emissions severely challenges human survival and development. Countries worldwide are taking action to control carbon emissions in response to global climate change under the constraints of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). As the largest emerging market economy, China’s rapid economic growth has resulted in elevated carbon emissions, necessitating an urgent decoupling of economic growth from carbon emissions (Riti et al., 2017). The Chinese government has set carbon peak and neutrality targets to achieve low-carbon economic development. At the same time, massive fiscal stimulus packages implemented in response to the great recession have led to a surge in local government debt in China (Aizenman et al., 2007). Government debt is a lever for economic development. It determines how much a country allocates financial resources to achieve carbon emission reduction targets (Chien et al., 2021). Therefore, the Chinese government needs to achieve coordinated governance of debt risk and carbon emissions (Boly et al., 2022). The prerequisite for achieving comprehensive governance is clarifying the causal link between debt risk prevention and carbon emissions.

The fiscal decentralization reform in 1994 resulted in a mismatch between local governments” financial and functional powers, creating a significant funding gap and putting them under considerable financial pressure (Yu et al., 2024). Local governments set up financing platform companies to indirectly borrow money to alleviate financial pressure. In 2008, the global financial crisis erupted. To cooperate with the Chinese government’s expansionary fiscal policy, local governments borrowed through financing platforms, and the debt scale rapidly increased, reaching 40.74 trillion yuan by 20232. The adverse effects of debt expansion are becoming apparent. On the one hand, under the political promotion tournament, local governments invested massive debt funds in infrastructure while simultaneously depressing industrial land prices to attract liquid industrial capital (Zhang et al., 2022). Increasing debt-servicing pressures and fierce competition for attracting capital lowers the environmental threshold and results in the concentration of numerous crude enterprises (Zhou et al., 2023). It also increases local governments” productive expenditures, which are invested in transport, energy and urban construction, thus crowding out environmental funds needed for carbon management. On the other hand, continuously rising government debt will intensify the competition between the public and private sectors, and public-sector debt financing with government credit endorsement will have a crowding-out effect on private-sector financing (Huang et al., 2020). This effect will increase the latter’s financing difficulties and reduce its incentive to reduce pollution, which is not conducive to regional and national environmental protection (Zhao et al., 2024).

In August 2014, China amended the New Budget Law and promulgated the Opinions on Strengthening the Management of Local Government Debt in October of the same year. The two policies aim to strengthen Local Government Debt Governance (LGDG) while fundamentally adjusting the main body of debt, its use, and the government’s responsibilities. The former enables local governments to issue bonds within a specified quota and incorporate them into budgetary management. The latter clarifies that local governments are not responsible for debt repayment and removes government financing functions of financing platforms. With the gradual implementation of reform, the growth momentum of government debt has been curbed. The reform weakens the competitive advantage of financing platforms in the credit market and alleviates the financing constraints faced by private enterprises (Asteriou et al., 2021). Still, it also reduces the vicious competition among local governments to attract investment and the crowding out of environmental protection funds through productive expenditures (Huang et al., 2020). Therefore, it provides an essential financial guarantee for carbon emission reduction. Previous studies have concentrated on the influence of government debt on economic development (Aizenman et al., 2007), fiscal expenditure (Barucci et al., 2023), financial risk (Song et al., 2012) and corporate investment and financing (Demirci et al., 2019). Some Studies have also examined the interaction between government debt stocks and carbon emissions (Fodha and Thomas, 2014). Other studies have explored how government debt influences environmental pollution based on the externality theory (Han et al., 2024), environmental Kuznets theory (Mao et al., 2022), as well as the impact of corporate pollution emissions through competition for land investment (Li and Qiu, 2024) and corporate investment and financing constraints (Zhou et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2020). However, more literature needs to analyze the effects of LGDG on reducing carbon emissions.

This study employs LGDG as an exogenous policy shock. It uses panel data from 274 cities to assess the influence of LGDG on carbon emissions, utilizing an IDID. It was found that LGDG can reduce carbon emissions and is robust. Mechanistic analyses show that LGDG leads to lower carbon emissions by reducing economic infrastructure investments and land resource mismatches. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that LGDG has a more pronounced effect on carbon emissions reduction when economic development pressures are relatively low, marketization is relatively high, environmental regulations are relatively strict, and the geographical location is in the central and western regions.

The possible contributions are the following. First, it expands the research perspective. In light of the dual-carbon target, academics is concentrating on the causes of carbon emissions and optimization paths (Han et al., 2024). However, more literature needs to analyze the effects of LGDG on carbon emission reduction. This paper analyses the impact of LGDG on carbon emissions and concludes that LGDG significantly reduces carbon emissions. It corroborates the finding of Mao et al. (2022), who found that financing platform debt increases corporate pollution emissions, and it complements the literature related to the impact of LGDG on carbon emissions. Second, the role of LGDG in influencing carbon emissions is examined through the lens of the government’s debt financing mechanism. When the reform has has significantly changed local governments” financing mode, this study takes the “capital supply - project demand” of government debt financing as the entry point and “land resource allocation” and “infrastructure investment” as the starting points to reveal how LGDG affects carbon emissions. The study provides a feasible path for local governments to collaboratively manage debt risks and carbon emissions. Third, the research results have specific practical value. Preventing local government debt risks and attaining carbon peaking and neutrality are the keys to high-quality economic development. Against this background, this study first confirms that LGDG can reduce carbon emissions and then explores the heterogeneous effects of marketization, economic development pressure, environmental regulation intensity, and geographical location on this relationship. This helps relevant departments formulate differentiated governance policies, successfully achieve carbon peak and neutrality targets, and provide valuable references for other economies with similar governance structures.

The rest of the study is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review and theoretical analysis, which compiles and reviews the relevant literature and analyses the mechanisms through which LGDG affects carbon emissions; Section 3 research design, introducing the data, variables, and models; Section 4 performs baseline regression analyses and robustness tests; Section 5 analyses the mechanism of action and does a heterogeneity test; Section 6 summarizes the full text and makes policy implications.

2 Literature review and theoretical analysis

2.1 Literature review

Under the dual pressure of achieving dual carbon goals and preventing debt risk, the issue of how local government debt influences carbon emissions has begun to receive attention. This article’s related literature primarily studies the connection between government debt and environmental protection, as well as the links between environmental protection and carbon emissions.

Concerning the link between government debt and environmental protection, much foreign literature validates the neoclassical economic theory that excessive government intervention causes the misallocation of market resources and triggers environmental pollution problems (Han et al., 2024). For local governments, growing debt has heightened the burden of debt repayment, which has tightened their financial constraints and reduced their capacity to pursue in environmental governance, thereby exacerbating environmental pollution (Barucci et al., 2023). Concerning private enterprises, Fodha and Thomas (2014) posit that an expansion in government productive debt will increase financing constraints for private enterprises, thereby reducing their environmental performance. Li and Qiu (2024) also believe that LGDG, which involves reducing the scale of financing platform debt to prevent and resolve local debt risks, will increase corporate green and environmental financing, which is beneficial for environmental protection. Zhou et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between municipal bond issuance scale and corporate pollution emissions, utilizing panel data from listed enterprises in China spanning 2007 to 2016. The findings indicate that municipal bonds enhance the intensity of consumption in enterprises” production processes, which is not conducive to environmental protection. Mao et al. (2022) confirm this viewpoint, stating that the expansion of financing platform debt intensifies competition for land investment, increasing in corporate pollution emissions. Some studies, however, take a slightly different view. Baret and Menuet (2024) argue that public debt provides the necessary funding for environmental pollution control. Monasterolo et al. (2024) suggests that issuing EU climate bonds to sell greenhouse gas emission allowances may help mitigate climate change. Boly et al. (2022) constructed an endogenous growth model incorporating government, enterprises and households. The study defined “environmental debt” as the cumulative carbon dioxide emissions and found that public debt and “environmental debt” are substituted in the short term. The expansion of public debt increases the liquidity of financial resources in the short term, thereby facilitating increased investment in pollution control and thus reducing “environmental debt.” Khan et al. (2021) reach a broadly consistent conclusion: highly indebted countries are more incentivized to improve environmental quality to attract international investment. Kantorowicz et al. (2024) conducted a comparative analysis of green investment and financing in Italy, a highly indebted country, and the Netherlands, a fiscally sound country. They found that debt financing is more effective than a large tax base in promoting green investment and reducing environmental pollution. Carratù et al. (2019) studied the connection between debt ratios and pollution emissions from consumption in EU countries, finding that increasing public debt favors reducing pollution emissions provided that the debt size does not exceed a threshold. Li and Huang (2022) agree that a government debt has a U-shaped non-linear impact on environmental pollution.

Existing studies primarily examine the factors affecting carbon emissions through the lens of environmental protection policies. However, the conclusions drawn are not uniform. Some scholars believe environmental policies exert a coercive effect on reducing carbon emissions (Shen et al., 2023). Guan et al. (2022) believe incorporating environmental protection into performance evaluations can significantly improve land utilization and lower carbon emissions. Aziz et al. (2024) used an extended STIRPAT model to study panel data from ten Canadian provinces. Their findings indicated that environmental protection policies within the public and private sectors can significantly promote urban carbon emission reductions. This result confirms the conclusion of Hashmi and Alam (2019) that environmental regulation can promote the reduction of carbon emissions in OECD countries. However, some scholars hold the opposite view, believing that environmental policies have a green paradox effect (Xing et al., 2024). Smulders et al. (2012) argue that the time difference between the announcement and implementation of environmental policies can lead to an “announcement effect,” resulting in an increase in fossil fuel usage and carbon emissions. Wang et al. (2018) also concluded that corporate carbon emissions have not decreased as a result of environmental protection policies. Hassan K. et al. (2022) employed an autoregressive distributed lag model to analyze 24 OECD member countries and found that environmental policies have not effectively restricted carbon emissions generated by consumption. Based on research in China’s metal industry, Zhang and Song (2021) found that environmental policies initially have a rising and declining impact on carbon emission reductions. Environmental protection policies can effectively reduce carbon emission during the early stages of implementation, but too strong environmental protection efforts can be counterproductive. In addition, some scholars have explored the impact of different environmental policies on carbon emissions (Chen and Wang, 2022). Government-led environmental policies influence urban carbon emissions through formal regulation. Hassan et al. (2022) conducted a study sampling more than 200 countries over 40 years and found that countries with weaker environmental regulations had a higher proportion of polluting industries. Private-sector-led informal environmental policies influence government and corporate decisions through public environmental concerns, affecting carbon emissions (Ren et al., 2024).

The literature mentioned above still exhibits the following deficiencies. First, studies regarding the impact of government debt on environmental protection have primarily focused on debt expansion, overlooking the influence of LGDG. Furthermore, many studies rely on theoretical models (Aizenman et al., 2007; Fodha and Thomas, 2014), and several empirical papers have overlooked the endogeneity between government debt and carbon emissions. Second, scholars have primarily examined the effects of environmental regulation policies on carbon emissions; however, few have explored the factors influencing carbon emissions in relation to LGDG. This study selects data from 274 Chinese cities from 2009 to 2020 as a sample, uses the 2015“Opinions” to construct IDID estimation, integrates LGDG and carbon emissions into the same framework, and analyzes their mechanisms and heterogeneity characteristics, providing a path for coordinated governance of debt risks and carbon emissions.

2.2 Theoretical analysis: LGDG and carbon emissions

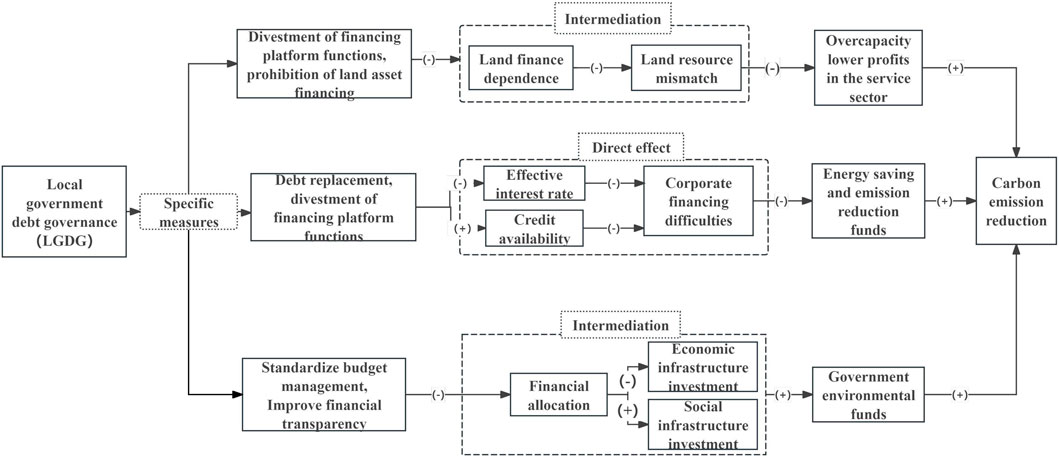

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical mechanisms of LGDG on carbon emissions. LGDG reduces the crowding-out effect of the public sector on the private sector and reduces carbon emissions by lowering the granting of industrial land and investment in economic infrastructure.

2.2.1 Theoretical basis for Hypothesis 1

First, LGDG impacts carbon emissions through divestment of financing platform functions, debt replacement and the standardization of budget management. Local governments have always been at the centre of the economic and social system, and the financing platforms representing them have financing advantages in the traditional credit market, resulting in the continuous expansion of government debt. Demand-side competition theory suggests that expanding lending by finance platforms will crowd out the credit resources of private firms and reduce their access to finance (Asteriou et al., 2021). From the perspective of price competition theory, an increase in the demand for government debt pushes up the demand for funds in the financial market, leading to a rise in the interest rate on government borrowing (Boly et al., 2022). The capital asset pricing model shows that financial institutions will set interest rates on deposits and loans using the interest rate on government debt as an essential reference for their decisions. As a result, increasing the government’s financing costs will increase corporate lending rates (Zhou et al., 2023). Carbon emission reduction requires long-term financial support, and companies are less motivated to reduce emissions when faced with “difficult and expensive financing.” This precisely confirms the law revealed by the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC): Before the inflection point of the EKC, debt-financed economic growth was accompanied by high carbon emissions (Grossman and Krueger, 1995). After LGDG, on the one hand, local governments” financing platforms functions were stripped, reducing their indirect intervention in the credit market and thus increasing corporate credit lines. On the other hand, the replacement bonds issued by local governments to repay the financing platform’s stock debt have lower interest rates and longer terms, which reduces the demand of local governments for bank credit funds and lowers the actual market interest rate level, thereby reducing corporate financing costs. Zhang and Song (2021) point out that alleviating financing difficulties has increased corporate environmental protection investment, such as purchasing energy-saving and emission-reduction equipment, and increasing investment in green technologies. This has lowered the tipping point of the EKC and is conducive to developing a low-carbon economy (Riti et al., 2017). Additionally, the new local debt governance plan strictly regulates the use and repayment of debt funds. It also includes debt funds in budget management, improves the efficiency of budgetary fund allocation, and ensures that funds are allocated to environmental protection governance and supervision. Local governments often promote enterprises” green and low-carbon transformation through non-market tools, such as increased environmental supervision and law enforcement, and market-based tools, such as financial subsidies and tax incentives, thereby reducing carbon emissions. On this basis, the following Hypothesis 1 is formulated.

Hypothesis 1. LGDG reduces carbon emissions.

In China’s evaluation and promotion system for officials, which prioritizes economic growth, local governments have established a competitive model for attracting investment, characterized by low industrial land prices and increased infrastructure investment. The fiscal decentralization system of “centralizing financial power and decentralizing administrative power” has resulted in a continual increase in local government fiscal deficits. Local governments have increasingly turned to borrowing through financing platforms to alleviate fiscal pressure and attract investment, resulting in a continuous rise in debt. In 2014, the central government issued a new Budget Law and Opinions to regulate government debt financing behavior (Asteriou et al., 2021). Reducing “misallocation of land resources” and “economic infrastructure investment” is the main policy tool for LGDG.

2.2.2 Theoretical basis for Hypothesis 2

Reducing “land resource mismatch.” On the one hand, local governments obtain bank loans based on credit or by pledging land assets to financing platforms. Loose borrowing relaxes the budgetary constraints of local governments, giving them more fiscal space for investment promotion. Industrial capital with a substantial tax base has muscular mobility and drives the development of upstream and downstream industries. Thus, it has become the main target of governments competing to attract capita (Mao et al., 2022). The fierce competition for investment promotion has led to expanding industrial land scale, distortion of industrial land prices and even “competition for the bottom line of quality (Bai et al., 2024).” Therefore, many high-carbon industrial enterprises have gathered in industrial parks, resulting in severe overcapacity and the formation of industrial clusters with high energy consumption and carbon emissions. On the other hand, debt expansion has intensified the debt servicing burden, prompting local governments to restrict commercial land use and sell commercial land at elevated prices to obtain land premiums as a guarantee for debt repayment. High commercial land prices raise the production cost in the service sector, leading to a decline in the profitability for high-value-added service industries, further hindering industrial restructuring. The delay in upgrading the industrial structure has resulted in increased energy consumption, reduced overall sector energy efficiency, and, increased urban carbon emissions. Additionally, the long-term low prices of industrial land suggest distortion from administrative intervention in the factor market. This distortion creates rent-seeking opportunities that enable enterprises to acquire production factors at lower costs and gain excess profits, thereby diminishing their incentive to innovate technologically. At the same time, the limited supply of commercial land has driven up housing prices. Profit-seeking enterprises tend to invest their capital in real estate for arbitrage, which crowds out capital investment in technological innovation and hinders regional carbon emission reductions. LGDG has stripped local financing platforms of their functions. It prohibits local governments from providing guarantees by injecting assets, such as land, into financing platforms, effectively reducing local government intervention in the land market. This reduces the problems of overcapacity resulting from the low price of industrial land and the decline in service industry profits caused by the high cost of commercial land. Low-efficiency, high-carbon-intensive enterprises are relocating due to rising industrial land costs, while the service industry is expanding due to increased profit margins, facilitating industrial restructuring and upgrading. At the same time, LGDG has decreased local governments’ reliance on land-related fiscal revenues. Enhanced efficiency in land resource allocation reduces opportunities for rent-seeking arbitrage, boosts corporate investment in technological innovation, and thus encourages carbon emissions reductions in the region. Therefore, the second hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2. LGDG reduces carbon emissions by lowering land resource mismatches.

2.2.3 Theoretical basis for Hypothesis 3

Reducing “economic infrastructure investment.” The World Bank (1994) categorizes infrastructure investment into economic and social infrastructure investments. Local governments allocate substantial debt funds to the production sector to construct infrastructure, achieving economic growth. The allocation of financial funds has two effects on carbon emissions. First, in the case of financial constraints, local governments” preference for “production-heavy” investment squeezes out environmental protection inputs, reducing financial funds available for pollution control and environmental protection supervision, which results in decreased pollution control and emission reduction by enterprises. Second, local officials are often keen to invest debt funds in infrastructure development to highlight political performance and promotion (Zhao et al., 2023). In general, activities related to the transportation and construction sectors are the primary sources of carbon emissions. The impact of infrastructure development on carbon emissions is mainly reflected in the construction and operation periods. During the construction period, the increased demand for transportation infrastructure will drive demand for products in upstream industries such as steel and cement, producing many high-carbon-density building materials and high energy consumption, thus increasing carbon emissions (Santos, 2017). During the operational period, transport infrastructure facilitates the development of the logistics sector and the improvement of population agglomeration patterns. However, the frequent utilization of transport vehicles has increased pollution emissions. As Xie et al. (2017) point out, transport infrastructure promotes regional economic growth but damages regional ecosystems. The construction and operation of buildings also affect carbon emissions. Fossil fuel consumption for maintenance and construction is a direct source of carbon emissions, while electricity and heat are indirect sources of carbon emissions. Moreover, the increase in construction has driven the demand for transportation infrastructure, thereby increasing carbon emissions. The LGDG programme clarifies that the use and repayment of debt financing should be subject to a strict repayment plan and a stable source of debt-servicing funds and should be incorporated into budget management. At the same time, information on the budget and final accounts has been made public, increasing financial transparency. These provisions have prompted local governments to scientifically plan the use and investment of debt funds, optimizing the structure of financial expenditures. It reduces duplicative construction and “performance projects” and reduces energy consumption. Moreover, LGDG can also increase funding for environmental protection governance and supervision, including expanding the area of community green space, increasing forest resources, and subsidizing energy conservation and emission reduction by enterprises. This is conducive to zero carbon emissions (Zhang et al., 2022). Thus, a third hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3. LGDG reduces carbon emissions by lowering economic infrastructure investment.

3 Research design

3.1 Data

This paper excludes the Tibet Autonomous Region and Sanya City due to insufficient economic data coverage, as well as Baishan City and Yangquan City, which have not published data. Second, we removed samples with missing main variables in the remaining regions, ultimately yielding 274 prefecture-level cities, as shown in the Supplementary Appendix. Considering the interference of major public health emergencies on the empirical results, the sample period is selected as 2009–2020, with 3288 valid samples. Control variables are from the CNRDS database, official websites of local statistical bureaus, the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, the China Financial Yearbook, and the China Energy Statistical Yearbook; carbon emissions data were obtained from the China Industrial Statistical Yearbook and the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook for the relevant years; municipal clerk ages are sourced from local municipal government websites; local government debt data from the wind database; and land resource mismatch data from China Land Market Network.

3.2 The econometric model

The Opinions were implemented nationwide in 2015, establishing a LGDG plan for the first time. To alleviate endogenous issues, this paper assesses the impact of LGDG by identifying differences between the treatment group and the control group before and after implementing the Opinions. The rationale is as follows: First, the reform aims to address the debt risks associated with financing platforms, and the policy impact is relatively exogenous to urban carbon emissions. Second, the reform content is consistent, and the implementation time remains unchanged. If traditional difference-in-differences (DID) approach is used, accurate grouping becomes challenging. This paper utilizes continuous variables to measure differences in policy implementation intensity, thereby overcoming the limitation of traditional DID, which can only employ binary treatment variables. Third, the higher a region’s dependence on the interest-bearing debt balance of the financing platform over a long period, the greater the policy impact. After the policy was implemented, local governments recognized the seriousness of the problem and gradually enhanced LGDG. Therefore, the balance of interest-bearing debt can effectively measure the differences in the intensity of policy shocks. This paper draws on Chen’s (2017) research methodology and uses IDID analysis to examine the impact of LGDG on carbon emissions. The model is as follows:

In Equation 1, i and t denote city and year, respectively. per_carbon is the per capita carbon emissions of the city i in year t. Following Hu et al. (2022), the interaction term Debt

3.3 The variables

3.3.1 Dependent variable

The independent variable is carbon emissions per capita (Per_carbon). Following Cong et al. (2014), all direct emissions within the urban area, energy-related indirect emissions outside the metropolitan, and other indirect emissions from the spillover of activities within the city are calculated separately. The total carbon emissions of each prefecture-level city are obtained by summing them and then divided by the total population to get the per capita carbon emissions. In the robustness test, this paper regresses the ratio of all direct emissions in the urban jurisdiction to the total local population (Per_carbon1) and the ratio of energy-related indirect emissions outside the urban jurisdiction to the total local population (Per_carbon2), respectively, as proxies for the independent variable (Per_carbon).

3.3.2 Independent variable

The financing platform’s interest-free debt is non-financial and does not involve debt risk. Accordingly, the interaction term between the balance of interest-bearing debt of financing platforms and the time of reform implementation (Debt

3.3.3 Intermediary variable

First, this paper collects the amount and area of each land market transaction in the country and selects matching prefecture-level city data from each land data set. The average price and average area of commercial land and the average price and average area of industrial land in each prefecture-level city are compiled based on industry classification information. The logarithmic ratio of the average price of industrial to commercial land (Land1), the logarithmic ratio of the average area of industrial to commercial land granted (Land2), and the ratio of commercial land to the total area (Land3) are used to measure the mismatch of land.

Second, the World Bank (1994) states that economic infrastructure consists mainly of public utilities and works, and other transport sector facilities, while social infrastructure includes education, environmental protection and medical care. As local government debt funds are primarily invested in economic infrastructure construction (Huang et al., 2020), according to Fourie (2006), the logarithmic of the ratio of fixed asset investment in municipal public facilities to regional GDP and the ratio of highway mileage to end-of-year population are employed as the proxy variables for public utilities and works (Facilities) and transport infrastructure (Transport), respectively. Social infrastructure is measured regarding library collections per capita (Social) and environmental protection inputs (Environmental) with logarithmic treatment.

3.3.4 Control variable

This paper controls for the following city characteristic variables: 1) Economic development (Per_gdp) is measured by taking the natural logarithm of GDP per capita. The level of economic development reflects the allocation of input factors such as labour, capital, and energy, which determine a city’s carbon emissions (Chai et al., 2023). 2)The proportion of the permanent urban population in the total permanent population of urban and rural areas measures the urbanization rate (Urban). The agglomeration effect of urbanization improves production efficiency and reduces carbon emission intensity. 3) Upgrading industrial structures can reduce a city’s dependence on traditional energy sources, influencing carbon emissions. This is measured by the proportion of the secondary industry (S_gdp) and the tertiary industry (T_gdp) in each city’s GDP. 4) Foreign capital dependency (FDI) is measured by the proportion of foreign capital actually utilized in each municipality to GDP for the year. 5) The fiscal deficit (Fiscal deficit) is the discrepancy between fiscal expenditures and revenues within the general budget. The larger the fiscal deficit in a region, the larger the debt is, and the more difficult it is to implement LGDG. 6) Regional economic development pressure (Pressure) is quantified by the natural logarithm of the age of the municipal party secretary (Mao et al., 2022). Pressure on regional economic development is the main reason for debt expansion. The smaller the pressure of economic development and the lower the productive expenditure, the more minor the crowding out of funds needed for carbon governance is conducive to carbon emission reduction. 7) Fiscal decentralization (Fiscal_dec) is determined by the share of municipal revenue in the sum of municipal, provincial and central revenue. The higher the autonomy of local finance, the stronger its ability to intervene in environmental protection and carbon reduction strategies, thereby affecting regional carbon emissions (Saveyn and Proost, 2008).

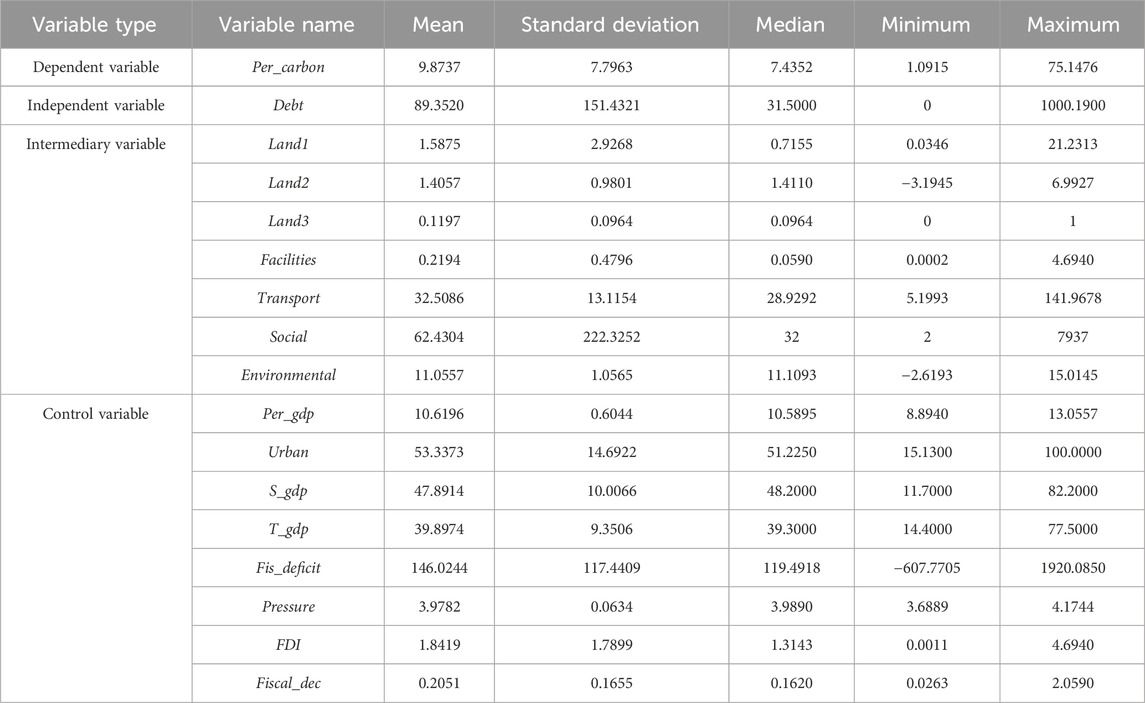

3.3.5 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 demonstrates that the variation in the coefficient of carbon emissions (Per_carbon) in each municipality is about 79%, indicating significant differences in carbon emissions in different regions. The extreme difference of Debt is 1000.1900, indicating significant differences in the interest-bearing debt balance of local financing platforms in different cities, and the effect of reform would also differ. The minimum of Land1 is 0.0346, and the maximum is 21.2313. This indicates differences in the ratio of industrial to commercial land unit prices in different regions. Furthermore, it can be inferred that the lower the ratio, the stronger the motivation of local officials to be promoted. The mean value of Land2 is 1.4057, which is lower than the median of 1.4110. This suggests that, in most areas, the area of industrial land granted is greater than that of commercial land. The mean value of Land3 is 0.1197, indicating that the average ratio of commercial land area to the region’s total area is only 11.97 percent, distorting land resource allocation. Facilities and Transport have significant extreme differences, suggesting substantial variations in economic infrastructure across different regions. The mean and median of Social are close to each other, suggesting less variation of environmental investment in different regions. The standard deviation of the control variable, the fiscal deficit, is significant, indicating that the fiscal gap and the scale of debt borrowing exhibit considerable variation across different regions. The results for the remaining variables were as expected. The above results suggest the existence of notable regional heterogeneity.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Correlation test

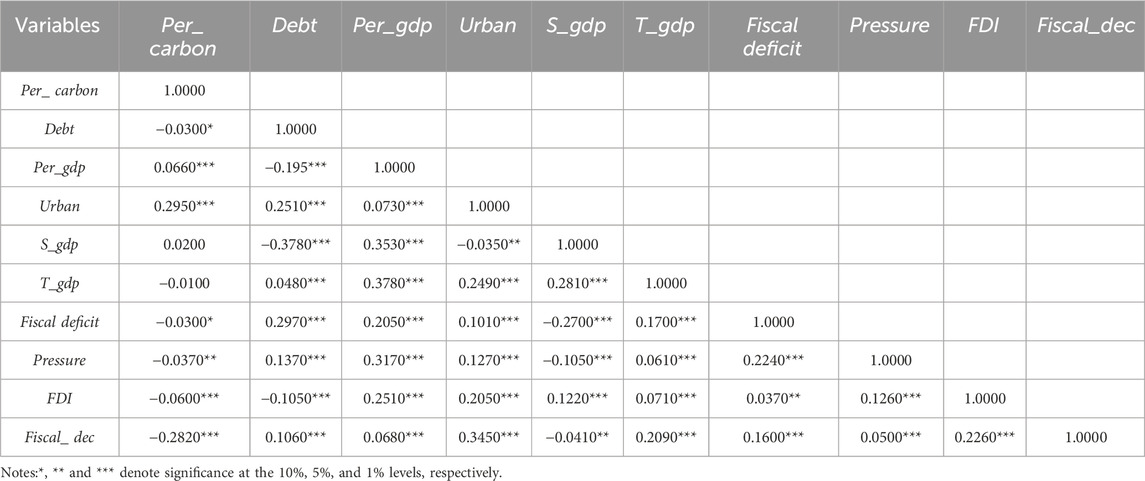

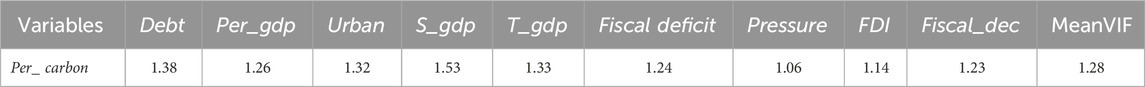

The correlation between variables may cause deviations in empirical findings. Thus, this study uses STATA 18 software to perform a Pearson correlation test on each variable. Table 2 shows a significantly negative between LGDG and carbon emissions is significantly negative, preliminarily verifying the first hypothesis. In addition, all correlation coefficients are less than 0.5, indicating a weak linear relationship between the variables. Table 3 shows that the VIF values are far below 10, indicating no multicollinearity problem.

4.2 Baseline results

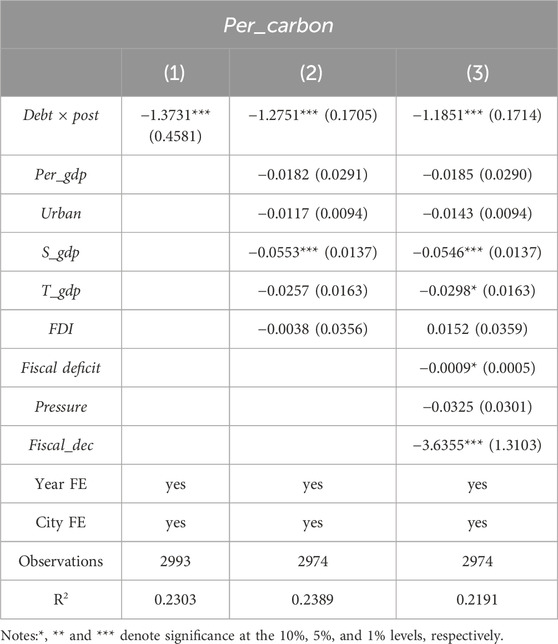

Table 4 (1) controls only for city and year variables, while columns (2) and (3) add, in turn, relevant indicators measuring regional economic development and regional finance-related indicators. Regardless of the variables variable employed, the coefficient on Debt

The coefficients of S_gdp and T_gdp in the control variables are significantly negative, indicating that upgrading the industrial structure is beneficial for reducing urban carbon emissions. The finding corroborates the conclusions of Zheng et al. (2023). The reason is that upgrading industrial structures has eliminated some high-energy-consuming industrial enterprises, diminishing the industrial sector’s output value. Concurrently, it improves energy utilization efficiency, and energy activities are the primary source of carbon emissions. The fiscal deficit coefficient value is −0.0009. This is significant at the 10% level, indicating that a rise in the budgetary deficit will have a substantial negative impact on carbon emissions. After basic public needs are met, local governments may only govern “luxury” public goods such as carbon emissions. Thus, it is more likely in regions with more significant fiscal deficits. The fiscal decentralization coefficient is significantly negative at the 1% level, suggesting that increased local fiscal autonomy reduces carbon emissions, aligning with the observations of Saveyn and Proost (2008). This is because the environmental federalism theory posits that local governments will enhance the supply of public goods in jurisdictions to win votes. Increased financial autonomy will give local governments sufficient funds to manage ecological public goods and reduce carbon emissions, thereby meeting residents” interests. Increases in control variables such as GDP per capita, urbanization rate, and regional economic development pressures favour carbon reduction, while increases in foreign investment dependence are not. However, the coefficients for the above control variables are not statistically significant.

4.3 Robustness check

Benchmark regression may encounter issues such as trend differences, difficult-to-observe factors, variable selection bias, interference from competitive policies during the same period, and endogeneity, all of which can interfere with empirical results. Therefore, to ascertain the robustness of the results, this study conducted parallel trend tests on the samples to exclude the interference of trend differences, placebo tests to exclude the interference of difficult-to-observe factors, core explanatory variables to exclude the influence of variable selection bias, PSM-DID tests to exclude endogeneity problems caused by sample selection bias, interference from contemporaneous policies, and instrumental variable estimation to exclude endogeneity problems caused by reverse causality.

4.3.1 Parallel trend test

Refer to Hu et al. (2022) to verify that the changing trend between the control and treatment groups was the same before the reform. The model is designed as shown in Equation 2.

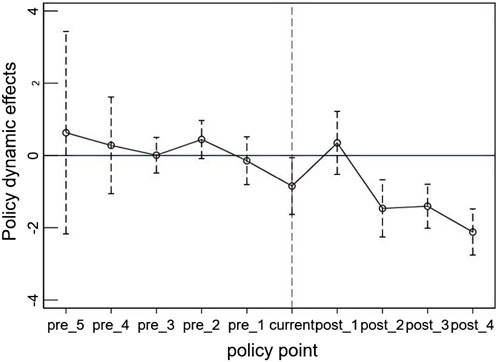

The first period of the sample, 2009, is used as the base period, and the parallel trends are judged based on the significance of the net effect coefficients

4.3.2 Placebo test

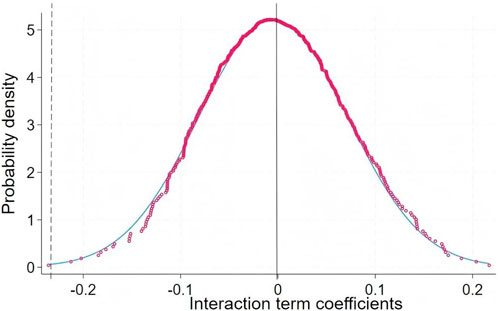

The paper conducts the following placebo test to eliminate the influence of unobserved factors during policy implementation: 1) Local financing platforms” balance of interest-bearing debt was randomly allocated across prefecture-level cities. This simulated reform variable interacted with the previous debt balance to re-perform the IDID regression. The process above was repeated 500 times to obtain the density distribution of the regression coefficients. As illustrated in Figure 3, the estimated coefficient of Debt

4.3.3 Substitution of variables

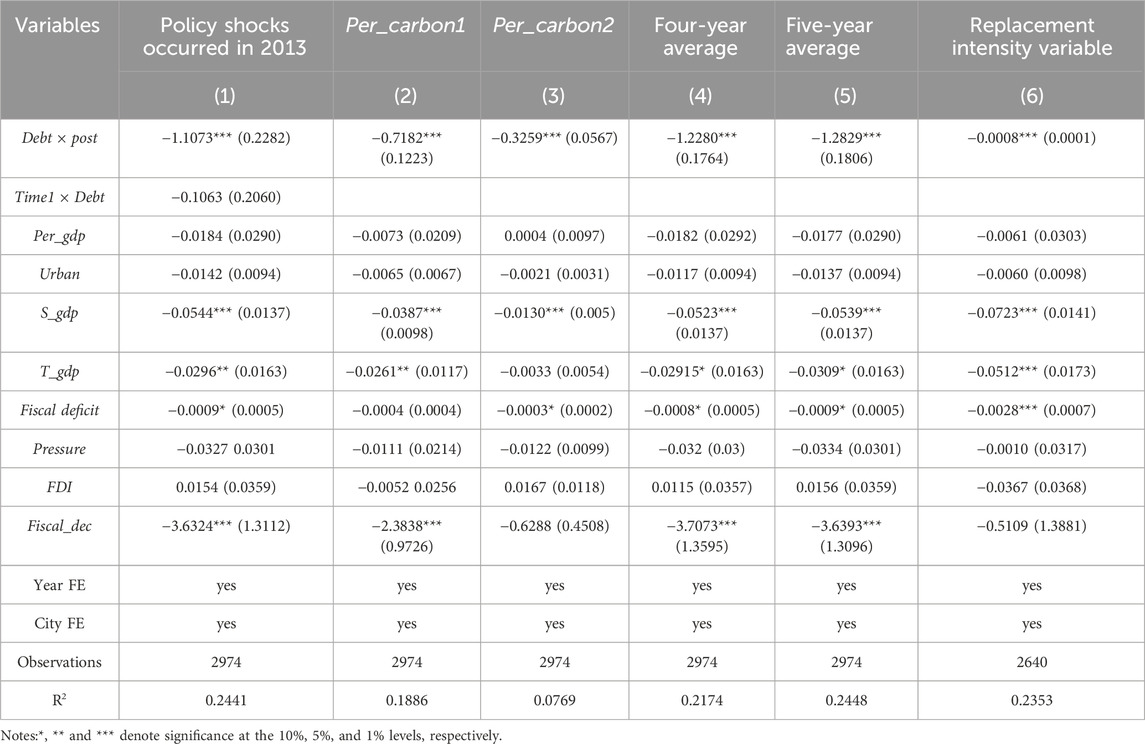

This study conducts substitution tests on the core explanatory variable and the dependent variable to eliminate endogeneity issues caused by variable selection bias. Referring to Cong et al. (2014), this paper uses direct per capita emissions within the urban jurisdiction (Per_carbon1) and indirect energy-related per capita emissions outside the urban jurisdiction (Per_carbon2) as the proxy variables for the explanatory variable per capita carbon emissions (Per_carbon) respectively. The results in Table 5 (2) and (3) demonstrate that the coefficient estimate on LGDG is significantly negative at the 1% level, consistent with the sign of the forecast in Table 5 (3).

The local financing platform debt is implicit debt outside the statutory debt limit, which may underestimate the debt size on local government statistics books. Therefore, referencing Brixi and Schick (2002), explicit and implicit in the local government debt matrix were used to carve out the debt boundaries. Data on explicit debt with legal repayment obligations is published only at the provincial level. Drawing on the research of Mao and Huang (2018), we allocated the explicit debt balance of provincial-level local governments to prefecture-level cities based on each prefecture-level city’s GDP proportion to the provincial GDP, thereby obtaining the explicit debt of prefecture-level cities. The results in Table 5 (6) show that the coefficient of LGDG is significantly negative, which is the same conclusion as in Table 2.

To reduce the impact of period selection on the benchmark regression results, this paper regresses the mean value of interest-bearing debt balances of financing platforms in the four and 5 years before the policy’s implementation as a proxy variable for Debt, respectively. Table 5 (4) and (5) show that the magnitude and significance of the LGDG are consistent with the results in Table 2.

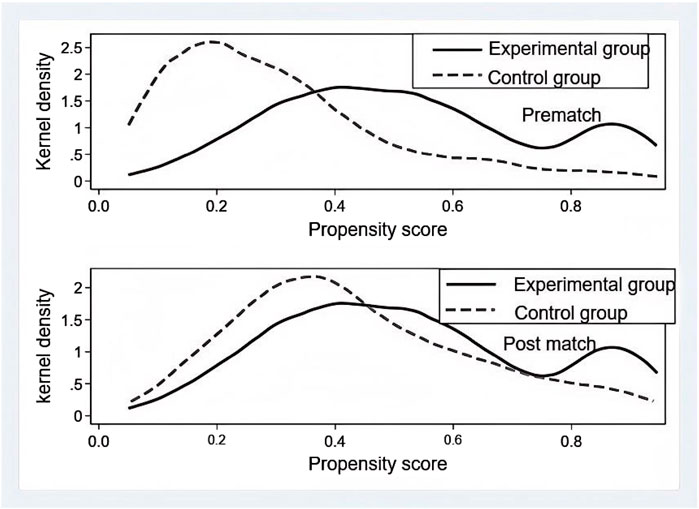

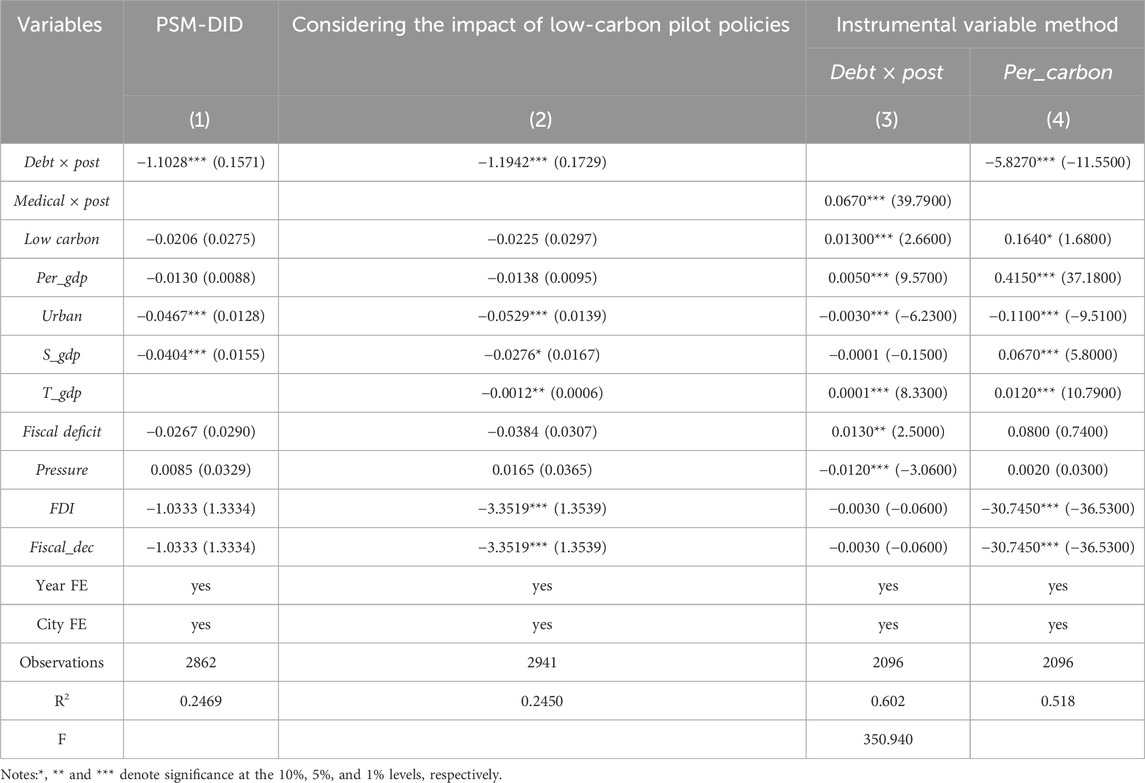

4.3.4 PSM-DID model

To exclude the endogeneity issue stemming from sample selection bias, Debt

4.3.5 Excluding the impact of low-carbon pilot policies

China launched low-carbon pilots in 2013, 2014 and 2016. According to Luo et al. (2024), to eliminate the interference of low-carbon city pilot policies, cities belonging to the pilot region are assigned a value of 1 and vice versa as 0. The existence of duplicate pilot cities is defined as the earliest implementation of a low-carbon pilot. If a region is approved as a low-carbon pilot, all cities are low-carbon city pilots. Table 6 (2) shows that the low-carbon pilot policy has no significant effect on carbon emissions, preventing the policy from interfering with the empirical results.

4.3.6 Instrumental variable estimation

The findings presented above indicate that LGDG can potentially influence carbon emissions. However, from a logical perspective, the implementation of unreasonable carbon reduction policies may also result in a reduction of tax sources, an increase in fiscal pressure, and the emergence of local debt risks. We perform instrumental variable estimation to eliminate the endogeneity resulting from reverse causality. This paper refers to Demirci et al. (2019), which uses healthcare expenditures (Medical) in prefecture-level cities as an instrumental variable for balancing interest-bearing debt of financing platforms. According to econometric principles, instrumental variables need to meet the correlation and exogenous assumptions. On one hand, the debt incurred by financing platforms was primarily used for investment expenditures, such as infrastructure and land development. However, LGDG has curtailed such spending. Under the strict constraints of the fiscal expenditure structure, the proportion of healthcare expenditure has increased, indicating a correlation between the outstanding interest-bearing debt of financing platforms and healthcare expenditure. On the other hand, healthcare expenditures are primarily influenced by demographic characteristics and do not directly involve industrial activities, such as energy consumption. Therefore, the instrumental variable has no direct relationship with carbon emissions and satisfies the exogenous assumption. The regression results in Table 6 (3) show that the interaction term Medical

In conclusion, the sign and significance of the coefficients on Debt

5 Further analysis

5.1 Mechanism testing

This paper has verified that LGDG will significantly reduce carbon emissions. How can the mechanism between the two be quantified? LGDG is an essential means for local governments to mitigate financial risk. By changing the government’s debt financing mechanism, it affects carbon emissions. Therefore, this paper argues that LGDG mainly reduces carbon emissions by reducing land resource mismatch and economic infrastructure investment.

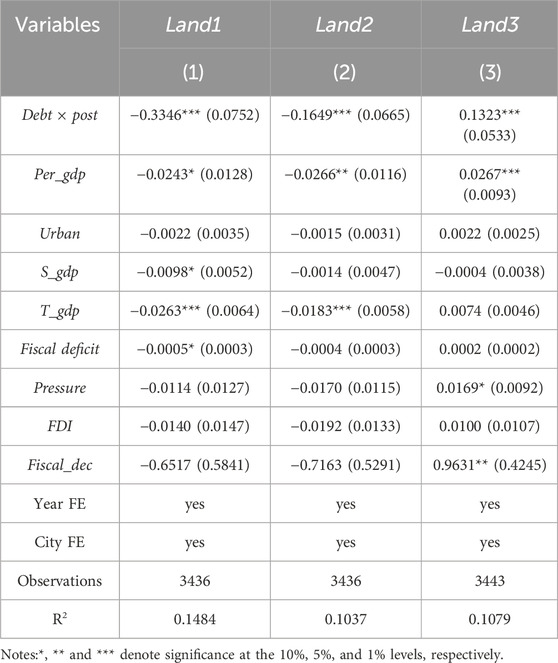

5.1.1 Reducing the mismatch of land resources

The theoretical analyses in Section 2 demonstrate that LGDG is more effective in regions with higher debt dependence. LGDG constrains the government’s land transfer behaviour. It reduces the mismatch of land resources, leading to a reduction in the area, an increase in the price of industrial land, an increase in the area and a decrease in the price of commercial land (Bai et al., 2024). Therefore, LGDG helps reduce excess capacity and improve energy efficiency, reducing carbon emissions. Table 7 (1) and (2) show that the coefficient of Debt

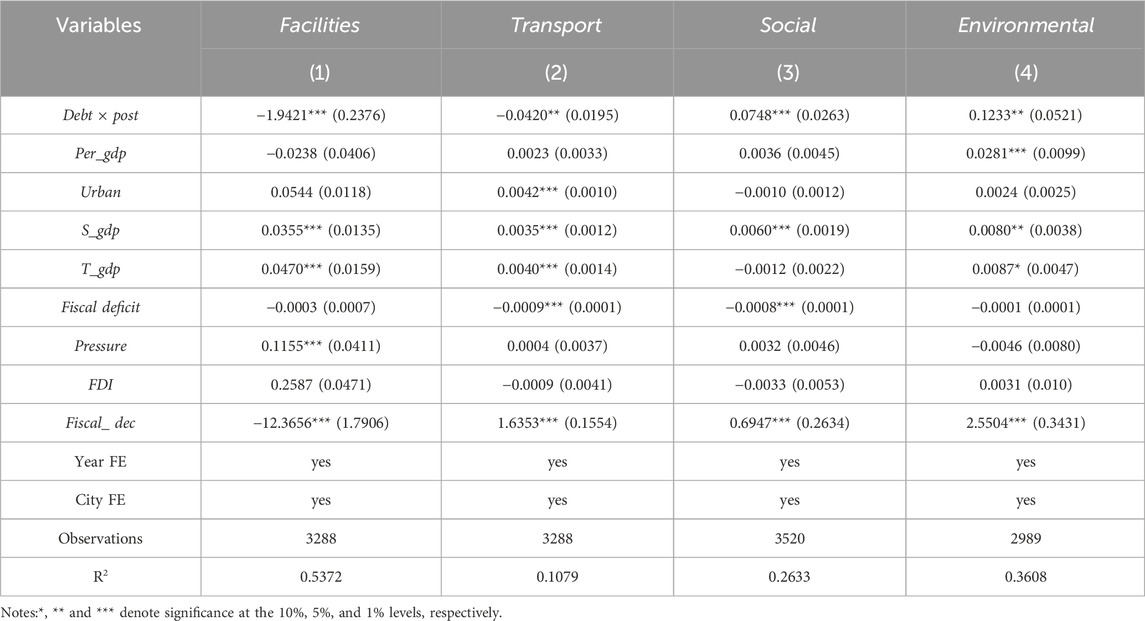

5.1.2 Reducing economic infrastructure investment

The theoretical analysis demonstrated that LGDG has prompted more apparent improvements in areas heavily dependent on local government debt. The reduction in financial funds for economic infrastructure investment and the growth in financial investment in social infrastructure, such as environmental pollution control, have a more pronounced impact on optimizing the fiscal expenditure structure, thereby reducing carbon emissions (Xie et al., 2017). Table 8 (1) and (2) show that the coefficient for Debt

5.2 Heterogeneity test

Differences in resource endowments, development levels, environmental policies, and geographical locations across regions may result in varied impacts of LGDG on carbon emissions. To accurately identify these heterogeneous characteristics, this paper examines how different levels of economic development pressure, marketization, environmental regulation, and geographical location influence LGDG’s carbon emission reduction effects.

5.2.1 Economic development pressures

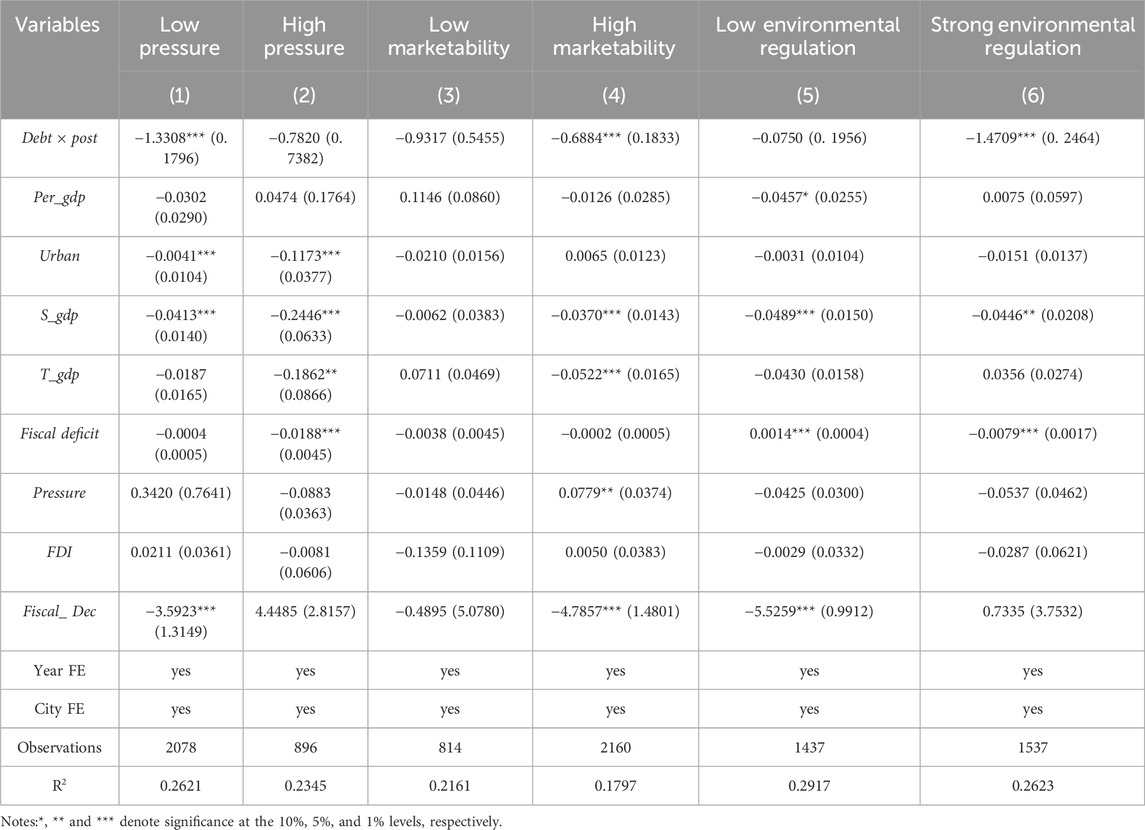

Under an evaluation and promotion system of officials centered on GDP growth, economic development pressures are a crucial factor affecting the relationship between LGDG and carbon emissions. Regions with low economic development pressures demonstrate strong fiscal self-sufficiency and depend less on economic infrastructure investments and industrial land subsidies, resulting in weaker constraints on short-term growth. In light of the dual-carbon target requirement, these regions tend to utilize the funds released from LGDG to address pollution and enhance the environment, thereby attracting more production factors. At the same time, regions with lower pressure are less reliant on debt financing, less impacted by LGDG, and can effectively enhance environmental governance, resulting in more substantial carbon emission reductions. Accordingly, this section employs the age of the municipal party committee secretary as a proxy variable for economic development pressure to divide the groups. Older municipal secretaries with fewer promotion incentives tend to adopt conservative policies as the group with low economic development pressures, and younger municipal secretaries as the group with high pressures (Mao et al., 2022). The results in Table 9 (1) and (2) indicate that the coefficient of Debt

5.2.2 Degree of marketization

The degree of marketization influences the green allocation efficiency of debt funds, thereby impacting the effectiveness of LGDG. A higher degree of marketization means mature product and factor markets, a sound legal and regulatory system, and high resource allocation efficiency. LGDG regulates local governments” debt financing behavior at the legal level, fosters a favourable development environment for economic entities, and facilitates cities” transition to green and low-carbon practices. When the degree of marketization is low, the inefficient allocation of market resources hinders the effectiveness of LGDG. Therefore, the regulatory effect of LGDG is more evident in areas with a high degree of marketization. Based on this, this study uses the marketization index method proposed by Fan et al. (2011) to ascertain each region’s degree of marketization. The pre-policy sample mean was employed as the basis for grouping, with those greater than or equal to the mean being the higher marketization group and those less than the mean being the lower group. Table 9 (3) and (4) demonstrate that the coefficient of Debt

5.2.3 Environmental regulatory intensity

Environmental regulations are direct measures for regulating carbon emissions and influence the green investment preference of debt. Stronger environmental regulations will raise the financing costs of high-carbon projects, prompting local governments to enhance environmental protection investments and green low-carbon subsidies to meet carbon emission reduction targets (Bai et al., 2024). Therefore, environmental regulation increases investments in debt funds for environmental protection. LGDG has limited debt expansion, with regions subject to stricter regulations significantly affected. Drawing on Zhou et al. (2024), this study uses the comprehensive index of various pollutant emissions in a city to represent the strength of environmental regulation. The median value of the index is used as the criterion to divide the sample into two groups: those with stronger ecological regulation and those with weaker environmental regulation. Table 9 (5) and (6) demonstrate that the coefficient of Debt

5.2.4 Geographical location

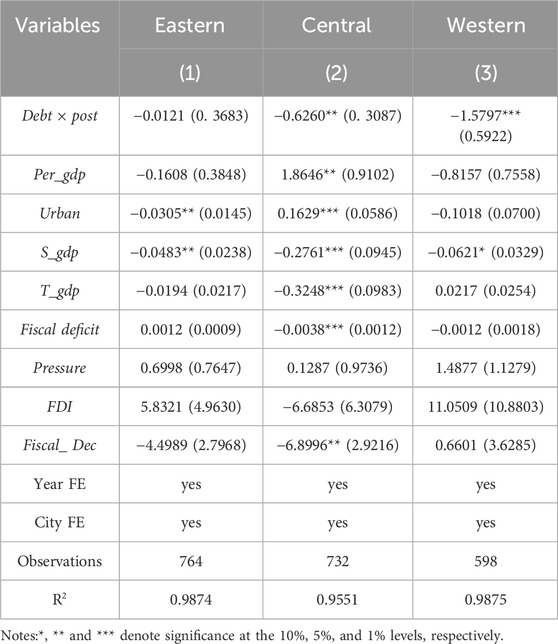

The impact of LGDG on carbon emissions will also exhibit heterogeneity due to the varying resource endowments and industrial structures of cities across different geographical locations. The central and western regions face significant pressures for economic development, and local governments often rely on non-market methods, such as debt financing, to stimulate economic growth. This manifests in suppressing industrial land prices to attract high-tax-base industrial enterprises while increasing investment in economic infrastructure to promote investment attraction. These projects typically have high carbon emission characteristics. The eastern region is economically advanced, with the service sector accounting for a relatively high proportion of the regional economy. Debt funds primarily invest in low-carbon emission sectors, such as high-tech and modern service industries. Therefore, when local governments implement measures to control debt expansion, the central and western regions will be significantly affected. Moreover, under pressure from economic development, central and western regions may ease environmental regulations, and LGDG could be enforced by limiting financing for high-carbon projects, thus compelling enterprises to reduce carbon emissions. Based on this, this paper categorizes the sample cities into eastern, central, and western regions. Table 10 shows that the coefficient of LGDG is significantly negative, at least 5%, in the central and western regions. Meanwhile, it is not significant in the eastern areas. The results indicate that LGDG significantly impacts reducing carbon emissions in the central and western cities, but not in eastern cities.

6 Conclusion and implications

This study uses 274 city panel data from 2009 to 2020 and LGDG as an exogenous policy shock. It uses the IDID to examine the impact of LGDG on carbon emissions. Research has found that after implementing LGDG policies, each city in the treatment group achieved an average reduction in carbon emissions of 1.1851 tonnes per capita compared to the control group. This demonstrates that LGDG can significantly promote carbon emissions reduction. The conclusions remain robust after employing various tests, including stepwise regression, parallel trend tests, and placebo tests, replacing core variables, controlling for contemporaneous policies, changing estimation methods, and using instrumental variables. Mechanism tests show that LGDG can reduce carbon emissions by mitigating “mismatches in land resources.” This is manifested in the fact that LGDG restricts local governments” land sales, resulting in a decrease in the area of industrial land and an escalation in its price while concurrently inducing a decline in the cost of commercial land. At the same time, LGDG mitigates carbon emissions by diminishing “economic infrastructure investment.” This is evidenced by the observation that LGDG reduces local government investment in economic infrastructure, including public facilities and engineering and transportation infrastructure, while increasing investment in social infrastructure, such as environmental protection and per capita library inventory. Heterogeneous analysis shows that LGDG’s effect on carbon emissions is significant in areas with less pressure for economic development and insignificant in areas with more pressure for economic growth. It is substantial in regions with a high degree of marketization but not in regions with a low degree; it is significant in areas with stronger environmental regulations but not in areas with weaker environmental regulations; and it has a significant effect in central and western cities, but not in eastern cities.

Policy implications and recommendations are as follows:

First, All levels of government must persist in advancing fiscal reform. Continue implementing reforms to the local government debt management system, strictly prevent debt risks, and eliminate the crowding-out effect of government debt on enterprises’ environmental protection investments at the source. The central government should establish a debt risk rating system and a debt statistics monitoring system based on the debt stock and the macro environment, thereby achieving standardized, scientific, and systematic government debt management. Local governments should incentivize tax-culminating growth and appropriately alleviate the macro-control responsibility of infrastructure investment to ease fiscal pressures. Concurrently, local governments should establish and improve climate finance and green bond issuance mechanisms, increase investments in new energy industries and those focused on energy conservation and emissions reduction, and utilize green financing to direct the economy toward low-carbon development. This will shift the EKC inflection point to the left, allowing economic growth to decouple from carbon emissions as soon as possible.

Second, promote the marketization of land resource allocation. This study shows that local governments’ discretionary power over land is the key to the mismatch of land resources. Therefore, governments should strengthen the market’s fundamental role in allocating land resources and establish a mechanism for coordinating industrial and commercial land transfer prices to reduce land resource mismatch. The central government should improve the performance appraisal system for officials, place less emphasis on economic growth in evaluations, and enhance the assessment of indicators that reflect the quality of economic development, such as people’s livelihoods and the environment. This will lessen the motivation of local governments to interfere in land allocation in pursuit of short-term performance. Simultaneously, reform the land transfer and expropriation systems, promote the market-based allocation of land resources, revitalize the land market through market mechanisms, and optimize the land structure.

Third, optimize the allocation of debt funds and strengthen environmental performance management. The findings confirm that LGDG reduces carbon emissions by lowering investment in economic infrastructure and increasing social infrastructure investments. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen the management of environmental impact assessments for economic infrastructure investments and actively promote ecological and environmental construction to achieve carbon emission reduction targets. The central government should appropriately allocate the powers and expenditure responsibilities of local governments concerning environmental protection and increase transfer payments for regions engaged in significant ecological construction projects. At the same time, enhance accountability for environmental performance in areas such as local green investment and green technology research and development, and establish a lifetime accountability system for environmental protection. Local governments should offer subsidies and tax incentives to encourage infrastructure companies to implement carbon reduction technologies in their production activities.

Finally, the Opinions allow local governments to issue bonds within certain limits to replace high-cost existing financing platform debt, while promoting the market-oriented transformation of financing platforms to curb the growth of new financing platform debt. These measures are essential for effective LGDG, helping to mitigate debt risks at their source and offering valuable lessons for developing countries and highly indebted nations. In addition, LGDG reduces carbon emissions by minimizing the misallocation of land resources and decreasing investments in economic infrastructure. This is instructive for countries where the government plays a leading role in resource allocation.

The paper quantitatively analyzed the impact of China’s LGDG on carbon emissions, but it still has limitations that can motivate future research. First, this paper uses balanced panel data to construct an IDID model for benchmark regression, and multiple robustness tests are used to rule out endogeneity and other unobservable factors. In the future, other models and robustness testing methods can be explored. Second, this paper focuses on the research of Chinese government departments. Therefore, the role of private sector participation in debt and environmental governance decisions deserves further exploration. Third, the research conclusion based on China’s institutional background holds reference significance for countries or regions with a governance structure similar to China’s. Therefore, future comparative analysis of LGDG policies in China and other countries with different governance structures is a promising research direction.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

YZ: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. JK: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1613947/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Data source: World Meteorological Organization. Address: https://wmo.int/.

2Data source: wind database. Address: https://www.wind.com.cn.

3The calculation formula is 12% = 1.1851/9.8737 * 100%.

References

Aizenman, J., Kletzer, K., and Pinto, B. (2007). Economic growth with constraints on tax revenues and public debt: implications for fiscal policy and cross-country differences. Cambridge, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Asteriou, D., Keith, P., and Cecilia Eny, P. (2021). Public debt and economic growth: panel data evidence for Asian countries. Econ. Finance 45, 270–287. doi:10.1007/s12197-020-09515-7

Aziz, N., Hossain, B., and Lamb, L. (2024). The effectiveness of environmental protection policies on greenhouse gas emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 450, 141868. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141868

Bai, C., Xie, D., and Zhang, Y. (2024). Industrial land transfer and enterprise pollution emissions: evidence from China. Econ. Analysis Policy 81, 181–194. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2023.11.029

Baret, M., and Menuet, M. (2024). Fiscal and environmental sustainability: is public debt environmentally friendly? Environ. Resour. Econ. 87, 1497–1520. doi:10.1007/s10640-024-00847-0

Barucci, E., Brachetta, M., and Marazzina, D. (2023). Debt redemption fund and fiscal incentives. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 119, 107094. doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2023.107094

Boly, M., Combes, J. L., Menuet, M., Minea, A., Motel, P. C., and Villieu, P. (2022). Can public debt mitigate environmental debt? Theory and empirical evidence. Energy Econ. 111, 111105895. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105895

Brixi, H., and Schick, A. (2002). Government at risk: contingent liabilities and fiscal risk. Washington DC: World Bank Publications.

Carratù, M., Chiarini, B., D'Agostino, A., Marzano, E., and Regoli, A. (2019). Air pollution and public finance: evidence for European countries. J. Econ. Stud. 46, 1398–1417. doi:10.1108/JES-03-2019-0116

Chai, J., Tian, L. Y., and Jia, R. N. (2023). New energy demonstration city, spatial spillover and carbon emission efficiency: evidence from China’s quasi-natural experiment. Energy Policy 173, 113389. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113389

Chen, L. F., and Wang, K. F. (2022). The spatial spillover effect of low-carbon city pilot scheme on green efficiency in China’s cities: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Energy Econ. 110, 106018. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106018

Chen, S. X. (2017). The effect of a fiscal squeeze on tax enforcement: evidence from a natural experiment in China. J. Public Econ. 147, 62–76. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.01.001

Chien, F., Sadiq, M., Nawaz, M. A., Hussain, M. S., Tran, T. D., and Thanh, T. L. (2021). A step toward reducing air pollution in top Asian economies: the role of green energy, eco-innovation, and environmental taxes. J. Environ. Manag. 297, 297113420. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113420

Cong, J. H., Liu, X. M., and Zhao, X. R. (2014). Demarcation problems and the corresponding measurement methods of the urban carbon accounting. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 24, 19–26. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-2104.2014.04.004

Demirci, I., Huang, J., and Sialm, C. (2019). Government debt and corporate leverage: international evidence. Econ 133, 337–356. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.03.009

Fan, G., Wang, X., and Ma, G. (2011). Contribution of marketization to China's economic growth. Econ. Res. J. 46, 4–16.

Fodha, M., and Thomas, S. (2014). Environmental quality, public debt and economic development. Environ. Resour. Econ. 57, 487–504. doi:10.1007/s10640-013-9639-x

Fourie, J. (2006). Economic infrastructure: a review of definitions, theory and empirics. South Afr. J. Econ., 09. doi:10.1111/j.1813-6982

Grossman, G. M., and Krueger, A. B. (1995). Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 110, 353–377. doi:10.2307/2118443

Guan, J., He, D., and Zhu, Q. (2022). More incentive, less pollution: the influence of official appraisal system reform on environmental enforcement. Resour. Energy Econ. 67, 101283. doi:10.1016/j.reseneeco.2021.101283

Han, Y., Bao, M., Niu, Y., and Rehman, J. u. (2024). Driving towards net zero emissions: the role of natural resources, government debt and political stability. Resour. Policy 88, 104479. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104479

Hashmi, R., and Alam, K. (2019). Dynamic relationship among environmental regulation, innovation, CO2 emissions, population, and economic growth in OECD countries: a panel investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 231, 1100–1109. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.325

Hassan, T., Khan, Y., He, C., Chen, J., Alsagr, N., Song, H., et al. (2022). Environmental regulations, political risk and consumption-based carbon emissions: evidence from OECD economies. J. Environ. Manag. 320, 115893. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115893

Hassan, T., Song, H., and Kirikkaleli, D. (2022). International trade and consumption-based carbon emissions: evaluating the role of composite risk for RCEP economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 3417–3437. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15617-4

Hu, Y., Zhang, H., and Ma, W. (2022). Reform in local government debt governance and human capital upgrading. Bus. Manag. J. 44, 152–169. doi:10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2022.08.009

Huang, Y., Pagano, M., and Panizza, U. (2020). Local crowding-out in China. J. Finance 75, 2855–2898. doi:10.1111/jofi.12966

Kantorowicz, J., Collewet, M., DiGiuseppe, M., and Vrijburg, H. (2024). How to finance green investments? The role of public debt. Energy Policy 184, 113899. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113899

Khan, S. A., Mubarik, M. S., Kusi-Sarpong, S., Zaman, S. I., and Kazmi, S. H. A. (2021). Social sustainable supply chains in the food industry: a perspective of an emerging economy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28, 404–418. doi:10.1002/csr.2057

Li, A., and Qiu, J. (2024). Does local government debt promote firm green innovation? Evidence from the Chinese local government debt governance reform. Econ. Analysis Policy 84, 1046–1062. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2024.10.010

Li, J., and Huang, M.Du. (2022). Spatial and nonlinear effects of local government debt on environmental pollution: evidence from China. China Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 101031691. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.1031691

Luo, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, D., and Han, W. (2024). Low-carbon city pilot policy and enterprise low-carbon innovation–A quasi-natural experiment from China. Econ. Analysis Policy 83, 204–222. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2024.06.014

Mao, J., Guo, Y. Q., and Cao, J. (2022). Local government financing vehicle debt and environmental pollution control. J. Manag. World 38, 96–118. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2022.0147

Mao, J., and Huang, C. Y. (2018). Local debts, regional disparity and economic growth: an empirical study based on China's prefecture-level data. J. Financial Res. 5, 1–19.

Monasterolo, I., Pacelli, A., Pagano, M., and Russo, C. (2024). A European climate bond. Econ. Policy 40, 307–339. doi:10.1093/epolic/eiae065

Ren, S., Wu, Y., Zhao, L., and Du, L. (2024). Third-party environmental information disclosure and firms' carbon emissions. Energy Econ. 131, 107350. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107350

Riti, S., Song, D., Shu, Y., and Kamah, M. (2017). Decoupling CO2 emission and economic growth in China: is there consistency in estimation results in analyzing environmental kuznets curve? J. Clean. Prod. 166, 1448–1461. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.117

Santos, G. (2017). Road transport and CO2 emissions: what are the challenges? Transp. Policy 59, 71–74. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.06.007

Saveyn, B., and Proost, S. (2008). Energy-tax reform with vertical tax externalities. Public Finance Anal. 64, 63–86. doi:10.1628/001522108x312078

Shen, Q., Pan, X. Y., and Feng, Y. C. (2023). Identifying and assessing the multiple effects of informal environmental regulation on carbon emissions in China. Environ. Res. 237, 116931. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116931

Smulders, S., Tsur, Y., and Zemel, A. (2012). Announcing climate policy: can a green paradox arise without scarcity? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 64, 364–376. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2012.02.007

Song, Z., Kjetil, S., and Fabrizio, Z. (2012). Rotten parents and disciplined children: a politico-economic theory of public expenditure and debt. Econometrica 80, 2785–2803. doi:10.3982/ECTA8910

Wang, S., Li, G., and Fang, C. (2018). Urbanization, economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions: empirical evidence from countries with different income levels. Renew. Sust. Energ Rev. 81, 2144–2159. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.025

Xie, R., Yuan, Y., and Huang, J. (2017). Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on “green” productivity: evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 132, 104–112. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.10.019

Xing, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., and Zhang, L. (2024). From green-washing to innovation-washing: environmental information intangibility and corporate green innovation in China. Int. Rev. Econ. and Finance 93, 204–226. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2024.03.077

Yu, S., Kang, W., Liu, W., Wang, D., Zheng, J., and Dong, B. (2024). The crowding out effect of local government debt expansion: insights from commercial credit financing. Econ. Analysis Policy 83, 858–872. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2024.07.001

Zhang, M., Tan, S., Pan, Z., Hao, D., Zhang, X., and Chen, Z. (2022). The spatial spillover effect and nonlinear relationship analysis between land resource misallocation and environmental pollution: evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 321, 115873. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115873

Zhang, Y., and Song, Y. (2021). Environmental regulations, energy and environment efficiency of China's metal industries: a provincial panel data analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 280, 124437. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124437

Zhao, J., Chen, W., Liu, Z., Liu, W., Li, K., and Zhang, B. (2024). Urban expansion, economic development, and carbon emissions: trends, patterns, and decoupling in mainland China’s provincial capitals (1985–2020). Ecol. Indic. 169, 112777. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112777

Zhao, X., Jia, M., and Zhang, Z. (2023). Promotion vs. pollution: city political status and firm pollution. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 1187, 122209. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122209

Zheng, Y., Tang, J., and Huang, F. (2023). The impact of industrial structure adjustment on the spatial industrial linkage of carbon emission: from the perspective of climate change mitigation. Journalof Environ. Manag. 345, 1118620. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118620

Zhou, J., Chen, H., Liu, J., Shen, Q., and Zang, D. (2024). Does environmental regulation promote urban economic resilience? A case of China's yangtze river economic belt. Sustain. Futur. 8, 100391. doi:10.1016/j.sftr.2024.100391

Keywords: local government debt governance, carbon emissions, land resource mismatches, economic infrastructure investment, intensity difference-in-differences model

Citation: Zhang Y and Kong J (2025) The impact of local government debt governance on carbon emissions: evidence from Chinese cities. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1613947. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1613947

Received: 18 April 2025; Accepted: 18 June 2025;

Published: 10 July 2025.

Edited by:

Lin Zhang, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Ismail Suardi Wekke, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Sorong, IndonesiaLatifa AlFadhel, Bahrain Polytechnic, Bahrain

Copyright © 2025 Zhang and Kong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Kong, a29uZ2p1bkBud3UuZWR1LmNu

Yan Zhang

Yan Zhang Jun Kong

Jun Kong