- Hebi Institute of Engineering and Technology, Henan Polytechnic University, Hebi, China

Introduction: Currently, the issue of greening of law is becoming increasingly important in the context of preserving the environment, biodiversity and ensuring sustainable development. Within the frames of growing commitment to achieving environmental goals, this issue is of particular relevance for China. The response of civil legislation to the protection of the environment and resources is not only tied to the national conditions of the country and corresponds to its environmental aspirations, but also conditioned by the need to protect the health and wellbeing of the population. In this regard, the role of civil society and associations of citizens and non-governmental organizations is becoming a new lever for the formation of environmental policy and legislative regulation. This paper intends to assess the current status and role of NGOs in the legislative initiatives of the PRC on the greening of regulatory mechanisms in general and in the field of environmental policy formation.

Methods: The methodological basis is presented by the methods of political and legal and content analysis.

Results and Discussion: The results of the study indicate the limited role of modern NGOs in matters of legal initiative in general and in matters of greening of legislation in particular. At present, there is no clear evidence that NGOs are a direct influence on the law making. At the same time, one can note the increasing role of NGOs in the formation of environmental policy. The latter trend is noted against the background of a general increase in public involvement in environmental initiatives, as well as the expansion of civil rights in the field of ecology.

1 Introduction

The greening of legislation is a process involving the incorporation of requirements into laws and other regulatory acts aimed at limiting the negative impact on the natural environment and applying them to various types of economic and other activities (Abanina, 2018). Currently, the issue of legislating for environmental considerations, and expanding the toolkit for shaping environmental policies and regulatory mechanisms, is increasingly viewed not only as the prerogative of the state but also as a process in which representatives of civil society should play a more active role (Veresha, 2016). In recent years, the importance of embracing this trend has become increasingly apparent in China (Li et al., 2018).

Over the past decades, China has experienced significant economic growth but concurrently has faced impressive consequences associated with environmental issues. These issues are particularly linked to the impacts of climate change, air and water pollution, as well as the loss of biodiversity (Ahmed et al., 2020). The state still faces with lasting desertification, particularly in the Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang regions, the river systems (especially the Yangtze and Pearl River) suffer from industrial and agricultural discharges (Ma, 2022; Yu et al., 2022). Herewith the full scale of the problem may be designated as rather proportional to China’s increased economic capabilities for recent decades. In response to these challenges, China has taken various environmental protection measures of both technical and regulatory nature, actively participating in international environmental conferences, emphasizing its commitment to sustainable development and environmental protection. The identified problems are recognized at the government level, while the executive branch tries to find accessible solutions, involving both state and non-governmental actors. An important element in the process of finding such solutions is the involvement of civil society organizations (CSOs), represented mainly by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which are a structured, formalized segment of civil society. Environmental NGOs are part of CSOs. Among other organizational and legal forms (such as public associations, trade/labor unions and associations, interest groups and lobbying structures, volunteer and youth associations, etc.), it is NGOs that, as a rule, are given a predominant role in environmental initiatives (Wang and You, 2024). Unlike other forms of CSOs, environmental NGOs often have a narrow environmental mission, such as forest conservation, animal protection, climate issues, etc. There is now growing evidence that China is generally quite open to CSO participation in environmental policy-making, and there is increasing reason to believe that they can make a proportionate contribution to improving both policy and regulation in this area. Chinese CSOs in the field of environmental protection are closer to the non-Western model, but in some respects they partially borrow elements of the Western model. Their activities are strictly institutionally limited and heavily dependent on the state, which distinguishes them from the classical Western paradigm of an independent civil society. At the same time, there are increasingly more reasons to believe that the so-called “non-Western” model used in China can also be effective in solving environmental problems. Its advantages include the ability to quickly mobilize resources and centralized decision-making, the absence of confrontations between actors, allowing for sustainable work within the system, and a focus on pragmatics rather than political criticism. At once, there are also important limitations of such a model associated mainly with dependence on the state agenda.

As part of its conservation efforts, the state is increasingly seeks assistance from international NGOs specializing in environmental protection and leverages the knowledge and expertise of domestic NGOs. The role of these organizations involves providing aid to those affected by pollution, advocating environmental goals to the government, facilitating access to legal recourse, and expanding rights for the protection and management of local resources (Zhai and Chang, 2019).

As of today, China demonstrates substantial willingness and capability to lead in the fight against climate change. The concept of “Ecological Civilization,” incorporated into the national legislation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), has the potential to transcend national boundaries and represent a set of new benchmarks and approaches in the field of environmental protection (Central Committee of CPC & State Council, 2015). Environmental policy in China significantly influences its legislation, a phenomenon particularly relevant during the codification of civil law in the country. This, in turn, necessitates effective regulatory mechanisms required for the proper implementation of environmental policies. Chinese civil law, governing personal and property relations between private subjects, is no exception to this influence. As a political goal, the pursuit of Ecological Civilization serves as a catalyst for revising civil legislation based on sustainable development, a phenomenon Chinese legal scholars refer to as the “greening of China’s civil legislation.” On the other hand, the response of civil law to environmental issues will aid China in addressing a serious environmental and resource crisis (Zhai and Chang, 2019).

China is actively engaged in reforms in the field of ecology and sustainable development. These efforts are reflected in various sectors of the regulatory component of societal functioning, including civil legislation. NGOs play an important and continuously expanding role in these endeavours. Currently, in specialized studies, it is increasingly noted that the emergence of environmental non-governmental organizations (environmental NGOs), driven by both general economic reforms and reforms in nature conservation, has proven beneficial in improving the quality of the environment (Wang et al., 2023; Zhai and Chang, 2019; Zhu and Wu, 2017). Non-governmental organizations and scholars, not affiliated with state governing bodies, are integral components of the system. They perceive themselves as defenders of public interests and act as independent observers, in contrast to officials (who may advocate certain political interests) and other parties directly affected by the issues at hand (McCormick, 2023).

Global experience suggests that NGOs can actively participate in the development and submission of proposals for civil legislation related to environmental issues. This may involve providing expert knowledge, analyzing legislative drafts, and offering suggestions for legislative improvement. NGOs can play a crucial role in monitoring compliance with laws and norms related to the environment. They can oversee the activities of companies, governments, and other actors to ensure adherence to environmental responsibility norms (Ho, 2001). Organizations of this nature can also conduct educational initiatives aimed at increasing environmental awareness among citizens. This may include educating on sustainable consumption practices, environmental impact, and more (Wang et al., 2023). It is important to note that NGOs can provide legal support for citizens and communities facing environmental problems. This includes representing the interests of citizens in court and protecting their rights in the event of violations of environmental standards (Ding and Xiao, 2021).

In addition to all the aforementioned, NGOs can contribute to amending existing legislation to enhance its effectiveness and align it with contemporary environmental challenges, thereby becoming full-fledged participants in legislative initiatives (Chu, 2023). More abstractly speaking, CSOs (both in a form of NGO or another) can perform the functions provided for by international environmental conventions, but their effectiveness depends on the political regime, legal framework and real involvement in the decision-making process. The success of greening China’s civil legislation depends, in part, on collaboration among the government, businesses, and NGOs. The development of partnerships and interactions among these sectors can contribute to more effective management of environmental issues and sustainable development.

For the last years, China’s environmental agenda has dictated the need to expand existing and search for new legal mechanisms in the field of environmental protection. Initiatives such as China’s “Ecological Civilization” concept, incorporated into the national legislation of the PRC, have the potential to transcend national boundaries, presenting a set of new benchmarks and approaches in the field of environmental protection. Under these conditions, the role of non-governmental actors in the formation of environmental policy and legal regulation of the PRC is increasing. These trends underscore the relevance of the examined topic as a subject of research. The purpose of this paper is to provide a comprehensive assessment of the current status and role of non-governmental organizations in legislative initiatives of the PRC related to the greening of regulatory mechanisms, as well as to analyze their actual participation in the formation of environmental policy, taking into account the peculiarities of the Chinese model of civil society organization.

2 Theoretical background

The role of CSOs and NGOs in environmental policy and legal regulation, according to the conventionally Western approach (in the spirit of documents such as Agenda 21, the Aarhus Convention, etc.), is based on the ideas of democracy, transparency and public participation in environmental management (UNECE, 1998). As a general rule, interested citizens (including activists, scientists, journalists and others), legal entities (in particular, professional associations, educational institutions) can join such organizations. As an important condition there commonly considered the openness and inclusiveness, i.e., membership should not be limited by gender, race, political views or other characteristics. According to the Aarhus Convention and in accordance with other international acts and regulations, the key rights of CSOs/NGOs within the scope include access to information on the state of the environment and activities affecting it. Besides these are the participation in decision-making regarding environmental policy, including the opportunity to make proposals, participate in public discussions, and represent the interests of citizens, as well as the right to justice–the ability to appeal government decisions that violate environmental standards or restrict public participation (Aarhus Centres, 2024; Khan and Agrarian, 2024). Based on Western ideas and practices, CSOs/NGOs should have a high degree of independence from the state and business, including financial autonomy, organizational independence (independent choice of goals, methods and forms of activity), as well as freedom of expression and public campaigning.

From the point of view of social purpose (role), the expected actions and functions of CSOs/NGOs (environmental and, often, in general) can be designated as mediation between society and the authorities. It is assumed that such organizations should perform the functions of informing and educating the population on environmental issues, monitoring the activities of the state and business in the field of ecology, promoting environmental reforms, and developing proposals to improve legislation. In addition, their activities can include organizing public campaigns (petitions, rallies), protecting the environment by legal measures (including lawsuits against violators), as well as international cooperation in the field of sustainable development and the protection of human rights in the environmental context. Thus, in the Western model of environmental governance, CSOs/NGOs are considered full-fledged participants in the environmental legal process, possessing rights, obligations and responsibilities, and acting on the basis of transparency, participation and the rule of law (Gutheil, 2021; Megersa, 2022).

Expected achievements with the participation of civil society usually imply increased transparency and accountability, decision-making that best reflects the interests of the population, and the protection of environmental rights and interests. This can also include the mobilization of public resources and knowledge. All this should ultimately create a synergistic effect, expressed in promoting more sustainable development, when a balance is formed between economic growth, social justice, and environmental protection through dialogue and participation. At the same time, the full implementation of all functions, especially control and human rights, requires the presence of an open environment based on transparency, participation, and the rule of law - characteristics that are most fully realized in democratic systems. Herewith, countries committed to other political regimes may also be interested in environmental protection, making an important contribution to environmental education, the local environmental movement, and the formation of public demand for sustainable development. Studies of countries that are not considered Western-style democracies are particularly devoted to such issues as the interpretation of climate change as a security threat in Vietnam (Gverdtsiteli, 2023), manipulation of environmental statistics in the Russian Federation (Masyutina et al., 2023), environmental protection under authoritarian regimes in Chile and Hungary during the Cold War (Pál and Perez, 2021). In particular, the first of the mentioned works discusses how Vietnam builds climate policy through security frames (water, food, energy), strengthening the legitimacy of the ruling party, without public participation. At the same time, climate issues are politicized through the status of a security threat, and not through the environmental agenda. In other words, the environmental agenda is replaced by a “security” one, and any grassroots initiatives can be presented as interfering with “national protection”. In general, different types of regimes demonstrate diverse environmental strategies, while there is no universal “standard of environmental behavior” (Eichhorn and Linhart, 2022).

The growth of environmental social activism and its relevance to contemporary Chinese politics has garnered the attention of scholars and inspired an increasing volume of academic research (Kuhn, 2021). Current studies covering various aspects of the impact of NGOs on environmental policy and legislative regulation in China delve into issues such as the influence of Chinese grassroots environmental NGOs on the adoption of state environmental decisions (illustrated by the construction of hydraulic structures within China’s water bodies) (Wang, 2022), the impact of environmental NGOs on human health in China in the context of existing environmental policies (Wang et al., 2023), cross-sector impact of NGOs’ roles on forest-certification policy (Hsieh and Yen, 2023), the regulatory functions of civil environmental lawsuits associated with public interests under the guidance of NGOs in China (Chu, 2023), the peculiarities of conducting legal proceedings for EPIL (Environmental Public Interest Litigation) in China (Ding and Xiao, 2021), the features of greening civil legislation in China from the perspective of convergence processes between individual norms of civil and environmental law (Zhai and Chang, 2019), the role of non-governmental environmental organizations in building China’s Ecological Civilization (examining the example of the organization “GREEN RIVER”) (Kuhn, 2021), the functions of social associations and private-public partnerships in environmental initiatives, and legal proceedings related to the protection of public interests in accordance with China’s Environmental Protection Law (Zhang and Mayer, 2017). Some of the studies mentioned have an empirical basis and focus on social factors (such as evidence of the beneficial effects of environmental NGOs on human health in China) (Hsieh and Yen, 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Others focus on policy, regulation and law enforcement (Chu, 2023; Ding and Xiao, 2021). Another ones assess the influence of environmental NGOs on the decision-making process, focusing on strategies for interaction between NGOs at different levels (Wang, 2022). Regarding the methodology used, these and most similar works, due to the specific nature of the issue, rely on complex interdisciplinary methods at the intersection of social sciences, politics and law.

3 Methodological framework

The documentary basis of this research consists of political documents (“Central Committee of CPC and State Council Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Ecological Civilization” (Central Committee of CPC & State Council, 2015), “Assessment Measures for Evaluating Objectives of the Ecological Civilization Construction” (CWR, 2017)) and legislative acts of China in the field of environmental protection, as well as the activities of NGOs within the country including:

- the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China dated 01.01.2015 (hereinafter - PRC Environmental Protection Law) (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 2015);

- the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Administration of Foreign NGOs’ Activities within China dated 01.01.2017 (hereinafter - PRC Foreign NGO Law) (Lovells, 2017);

- the Law of People’s Republic of China on Environmental Impact Appraisal dated 01.09.2003 (hereinafter - PRC Environmental Impact Assessment Law) (President of People’s Republic of China, 2003);

- Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China dated 31.12.2020 (in part of the norms covering the regulation of environmental issues) (The State Council, 2020);

- Besides, paper used data from platforms of active Chinese environmental NGOs (including analytical materials from the China Development Brief platform). The fundamentals of legislative regulation of the PRC concerning issues of environmental protection and the activities of environmental NGOs are considered in an inextricable connection with the concept of “Ecological Civilization” formalized in the Constitution of the PRC and political/program documents.

Using the method of political-legal analysis and secondary research methods, including content analysis, the study addresses issues related to the environmental activities of Chinese NGOs, their legal status, and their potential impact on environmental policy and legal regulation. The political and legal component of this study involves consideration of political and legal measures aimed, respectively, at setting political priorities and regulating legal relations in the environmental sphere, the rights and powers of specialized NGOs and related issues. The content analysis method in this research is used to study relevant analytic and scientific sources describing problems in the scopes above.

The first section of the work is devoted, respectively, to such issues as the current state of Chinese environmental policy, NGOs in the context of understanding the term “civil society” in China, as well as directly to the question of the role of NGOs in the formation of environmental policy and legal regulation of the PRC (the role of environmental organizations in issues formation of the environmental agenda, the problems faced by Chinese NGOs in the environmental sector and their role as subjects of law-making and political initiatives on environmental issues, as well as the expansion of their legal tools). Next, a subsection is presented regarding the implementation of the mechanisms of the UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention) in China. The second section (Environmental NGOs of the PRC as a subject of environmental policy formation in the context of scientific discourse) is devoted to the consideration of these issues in the context of the scientific views of Chinese and foreign scientists, as well as the potential for the development of Chinese environmental NGOs in terms of strengthening their political subjectivity and expanding the political and legal tools. The content analysis strategy is based on a systematic review of relevant Chinese and foreign sources, including information and analytical materials of Chinese and international NGOs (in particular, the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, the International Union for Conservation of Nature) as well as scientific papers on this topic. The analyzed theoretical sources refer to the category of publications over the past 4 years (since 2020). Some NGO materials related to the topic of this study that go beyond this period are also analyzed. The analytical strategy includes setting the goal and research questions, defining the data corpus (described above), qualitative analysis (research on political and legal decisions, related events, context), interpretation of existing problems, final assessment and conclusions. The selection of scientific materials and documents was carried out using the scientific databases Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar. The sources included peer-reviewed scientific articles, monographs, reports of international organizations and regulatory documents published between 2015 and 2025. The key selection criteria were relevance, relevance to the research topic, scientific significance and the presence of original data. Unverified sources, materials without scientific expertise, as well as documents that did not correspond to the subject area of the work were excluded from the analysis. To analyze the documents, qualitative content analysis was used (according to the object of analysis - political and legal, as well as media/discursive) with elements of latent analysis, aimed at identifying specific topics, the context of the problematic, concerning the role of NGOs in policy formation. The analysis was carried out manually, without the use of specialized software. The categories were defined a priori, based on the theoretical basis of the study, and included such areas as “environmental policy,” “legal regulation,” “non-governmental organizations,” “legislative initiative,” and “social challenges.” As the analysis progressed, some subcategories were clarified and supplemented, which allowed for flexible adaptation of the analytical scheme to the empirical material.

4 Section 1. Chinese environmental NGOs within the scope of national political and legal landscape

4.1 The current state of Chinese environmental policy in the context of contemporary challenges

In the past decades, China has witnessed an economic miracle, marked by rapid growth in various economic indicators and societal wellbeing. However, despite these outstanding achievements, China, as the world’s second-largest capitalist economy, confronts a serious environmental crisis. Experiencing both the benefits and burdens of capitalism and communism, the country’s contemporary efforts to overcome internal environmental challenges are unequivocally aimed at positioning China as one of the leading global powers within new civilizational frameworks extending beyond traditional socio-economic paradigms (Ahmed et al., 2020). Concurrently, with the deterioration of the environmental situation in China, an increasing number of people are concerned about environmental protection. In a context where the state is the sole legislative initiator for environmental matters, the leadership of the PRC nonetheless allows (and in some cases encourages) non-governmental initiatives to contribute to the enhancement of environmental legislation (Ahmed et al., 2020).

In the process of modernizing market mechanisms and experiencing intensive economic growth, China has inflicted serious damage to the environment, posing a significant constraint to overall socio-economic development. Although China’s modernization policy, conducted within the constraints of limited natural resources, has led to noticeable achievements, it has also resulted in the destabilization of the country’s environmental situation. Currently, the Chinese government is actively working to shape a favorable image of the country on the global stage, emphasizing its concern for the environment. China’s political behavior in this regard appears to be primarily driven by pragmatic goals, aimed at attracting foreign investments and assimilating advanced international scientific and technological expertise. At the same time, while attempting to portray itself as a developing country, China officially takes steps to avoid responsibility for potential negative consequences to global ecology resulting from its economic growth (K. Ahmed and S. Ahmed, 2018).

Environmental pollution and the confidentiality of ecological information by the People’s Republic of China have become one of the key arguments in the West’s confrontation with China amid the political and economic tensions of recent years (Wang, 2017). In the international arena, China has faced increasing diplomatic pressure to reconsider its positioning as a developing country that can still evade commitments to reduce emissions of pollutants into the atmosphere. This has prompted China to initiate a reassessment of its traditional interpretation of the principle of the so-called common but differentiated responsibilities. In doing so, China has become more constructively engaged in international cooperation in the fields of environmental protection and climate change. For instance, China played a significant role in facilitating the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015 (Kuhn, 2019).

In March 2015, the PRC issued a strategic document titled “Central Committee of CPC and State Council Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Ecological Civilization” (Central Committee of CPC & State Council, 2015). The main concept of the reform is the integration of ecological values and objectives into all spheres of societal development and citizen education. Within the proposed measures, the document envisions the implementation of an ecological responsibility system and the establishment of new standards in the field of nature conservation. These measures include the adoption of energy-efficient technologies, the utilization of resource-saving methods, the implementation of waste-minimizing circular production processes, the execution of functional ecological zoning for all territories, the establishment of limits on permissible loads for natural objects, and others. This document outlines specific tasks and is considered a long-term action plan for more detailed state planning within the process of transforming Chinese society into what is termed an “Ecological Civilization”.

In October 2017, during the 19th National Congress of the PRC, President Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of accelerating reforms in the field of ecology and the establishment of an environmental protection system following the concept of Ecological Civilization. He noted that, in addition to creating more material and cultural wealth to meet the constantly growing needs of the country’s citizens, China must also pay more attention to society’s demands for a favourable environment. To achieve this, China should promote “green” development, address significant environmental issues, strengthen ecosystem protection, and reform regulatory mechanisms in the field of ecology (China Daily, 2017). This message, as can be understood, is directed not only to governmental structures but also to Chinese society as a whole.

4.2 NGOs in the context of understanding the term “civil society” in China

The concept of “civil society” (CS) in the PRC has its own peculiarities and differs from the Western understanding of this term. In the countries of so-called “global north” (or “global west”) this term has several similar interdependent meanings. Synthesizing the main “Western” approaches to definition, civil society is a set of citizens who are not close to the levers of state power, a set of social relations outside the framework of government-state and commercial structures. This term also means the sphere of self-expression of citizens and voluntarily formed non-profit directed associations and organizations, protected from direct interference and arbitrary regulation by government authorities, as well as other external differences (Dryzek et al., 2008; Edwards, 2009). In the Chinese context, CS is developing within the framework of a socialist system with Chinese characteristics, which implies certain restrictions and state supervision (He, 2016).

The main features of civil society in the PRC include, first of all, state oversight. In China, all public organizations and NGOs must be registered and approved by government authorities, while the state retains significant control over the activities of such organizations. Another characteristic feature is partnership with the state. Many public organizations in China work closely with the government, performing functions that support government programs and policies. This is especially true for large charities and associations. Also noteworthy are restrictions on political activity and an emphasis in their activities on social services or work in related industries. Thus, most public organizations in China focus on providing social services such as education, healthcare, helping the poor and protecting the environment. These areas of activity usually do not cause conflict with the state and may even receive support from it (Frolic, 2015).

Despite different restrictions, the number of public organizations in China is growing (Pei, 2023). This is due to the increasing need for social services and awareness of the importance of citizen participation in solving social problems (Pei, 2023). Examples of social organizations in China include Yunus Social Business China (an organization that supports social entrepreneurship and sustainable development), China Development Brief (a platform that provides information and resources for NGOs and civic initiatives), or the Hong Kong Council of Social Service (an organization that representing the interests of the social sector in Hong Kong).

Under these conditions, the influence of civil society organizations and NGOs is gradually increasing in matters of policy formation and environmental legislation and the implementation of the concept of “Ecological Civilization” (生态文明). The latter has become an important part of Chinese government policy aimed at sustainable development and improving the environmental situation in the country. In 2015, China adopted a new version of the Environmental Protection Law. The law, in particular, significantly strengthened the requirements for enterprises to reduce pollution and improve environmental reporting. The updated law also provided new opportunities for NGOs to engage in environmental activities, in particular by giving environmental NGOs the right to take legal action against businesses that violate environmental laws. This has increased the ability of NGOs to influence compliance with environmental regulations. The law strengthened the role of public control over the environmental activities of enterprises, giving NGOs and citizens more rights to participate in public hearings and access to environmental information. NGOs, as an element and, at the same time, a tool for realizing the interests of civil society, have expanded their operation plane in the field of advocacy and lobbying. In particular, it has increased opportunities for participation in policy development - engaging with government agencies to make proposals to improve environmental laws and policies, and to advocate for the interests of citizens and local communities affected by environmental violations.

4.3 The issue of the role of NGOs in the formation of environmental policy and legal regulation of the PRC

One of the key components of global civil society is represented by non-governmental organizations, including those engaged in environmental activities. Therefore, it is important to consider the work of environmental organizations not only from an environmental but also from a legal perspective. The number and quality of such organizations reflect the level of development of civil society in a country and are regulated by regulatory acts. To enable the public to effectively influence the formulation and implementation of environmental policy, it is crucial to ensure objective information about the nature of environmental problems. This information should be qualitatively analyzed, and its interpretation and presentation should be accessible to non-professionals. This is especially important for the media. Underestimating or overestimating the degree of environmental hazard can lead to equally negative consequences (McCormick, 2023).

The evolution of Chinese environmental legislation, undergoing a gradual reduction in the role of the command-administrative system in public access to environmental information, has nonetheless not overcome the threshold beyond which the expansion of civic rights in the field of ecology could occur. Nevertheless, incremental shifts in this matter are indeed taking place. In recent years, there has been widespread acceptance of the idea that public involvement in decision-making processes enhances the quality of decisions and builds trust in the process and its outcomes (UNECE Aarhus Convention Secretariat, 2012). This, in turn, aligns with the belief that the accountability of governmental bodies is a key component of environmental conservation efforts. The development of environmental law has moved away from the traditional command-administrative approach regarding public involvement, viewing the public as regulators of the environment. In particular, there is a gradual strengthening of the conviction that changes are inevitable. The disclosure of environmental information contributes to the improvement of environmental policy by reducing information asymmetry between the state and its citizens (Whittaker, 2017).

In China the role of environmental NGOs in shaping these processes, although not so obvious at first glance, had always been irrefutable. NGOs have played and continue to play a key role in collecting data on environmental issues, monitoring compliance with environmental regulations, and publishing results. This helps draw attention to environmental issues and shortcomings in the current management system (Wang, 2022). Since the 1990s, NGOs have been active in public outreach, raising awareness of environmental issues, educating and mobilizing citizens to take an active role in environmental protection, and influencing legislators through petitions, appeals, and grassroots actions (Zeng et al., 2019). In addition, NGOs have worked and are working at the legislative level, advocating for the introduction of new or strengthening of existing environmental laws and standards. They present data and recommendations based on their experience and research (Wang, 2022). This ultimately contributes to the formation of more effective and responsible environmental policies, and at the same time to legislative regulation that details the policy.

Regarding issues of environmental safety, NGOs strive to play a more significant role within the framework of global governance. The UN Charter has historically recognized the importance of NGOs in environmental protection matters. “Our Common Future,” the document of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), called on governments to recognize and expand the right of NGOs to know and have access to information about the environment and natural resources; their right to consultation and participation in decision-making on activities that may have a significant impact on the environment; and their right to legal protection and compensation in cases where their health or the environment may be seriously affected (Federal Office for Spatial Development ARE, 1987). Despite the crucial role that NGOs play in environmental protection, their influence is rarely deeply assessed, unlike the activities and contributions of governmental institutions or government actors. In principle, the term “NGO” can be used to denote various entities related to climate change, from local environmental activist organizations or victims of hazardous environmental incidents (disasters) to large, well-established, highly qualified international corporations that resemble regulatory bodies but do not bear public responsibility (Wang et al., 2023).

NGOs are typically defined as non-profit entities that are fundamentally independent of the government and operate at the local, national, or international levels to address issues related to the public good. In the context of the Chinese language, the term “non-governmental organization” is represented by the term “shehui tuanti,” which translates as “social groups.” However, in China, there are organizations that, although organized and funded by the government, are registered as “shehui tuanti.” Such organizations in China also fulfil the roles and functions of NGOs. In this case, the term “caogen huanbao zuzhi” is used to denote grassroots environmental NGOs. The term “caogen huanbao zuzhi” (草根环保组织) in the Chinese language means “grassroots environmental organizations” or “groups of environmental activism by ordinary people.” This term is used to refer to NGOs in a global sense, engaging in environmental activities at the grassroots level and registered by individuals or private organizations independent of the state and its affiliated structures. These organizations may include activists, enthusiasts, and groups of citizens who share a common goal of protecting the environment and addressing local environmental issues. As for unregistered environmental NGOs, the Chinese government typically adopts a stance based on the principles of “no contact, non-recognition, and prohibition.” Consequently, it becomes challenging to obtain relevant information and data for analyzing the impact of these unregistered NGOs on environmental decision-making in China, unlike the situation with registered mainstream environmental NGOs (Wang, 2022). In these conditions, primary sources of information on the environmental activities and initiatives of NGOs often rely on secondary sources such as analytical materials or scientific studies. However, these sources mostly do not cover the legislative aspect, limiting themselves to the assessment of practical environmental initiatives or mechanisms influencing policy. Various Chinese studies assert that environmental NGOs can play a crucial role in safeguarding human health by advocating policies and practices that support a healthy environment. Environmental NGOs may engage in direct intervention to reduce or prevent environmental damage, for instance, through pollution monitoring, community organization, and advocating for stricter environmental norms (Chen et al., 2020). These measures can help mitigate the impact of harmful pollutants on people, subsequently improving public health.

Environmental NGOs can also play a decisive role in educating the public about the health effects of environmental degradation and pollution (Tu et al., 2019). By raising awareness of these issues, they can contribute to changing the behaviour of individuals and mobilizing communities to take action to protect the environment and public health. Other works highlight that environmental NGOs may collaborate with other organizations and institutions to contribute to creating a healthy environment and protecting human health (Patrick et al., 2022). For example, they may collaborate with public health organizations to develop joint initiatives aimed at addressing environmental hygiene issues or work with community groups to design local projects to enhance the environment (Wang et al., 2023).

Since the establishment of the first nationwide environmental NGO “Friends of Nature” in China in 1994, there has been a growth in the number of such organizations addressing the state’s environmental issues. Recognizing the role and significance of NGO activities, and taking into account the increasing environmental degradation in China, the government cautiously expresses support for environmental NGOs, implicitly encouraging them to play a more substantial role in mitigating the deterioration of the environment (Wang, 2022).

The specificity of Chinese NGOs lies in the fact that a significant portion of these organizations was initiated and supported by the Chinese government, which, however, contradicts foreign notions of NGOs assuming independence from the state and private organizational initiative. For example, the majority of Chinese environmental NGOs now fall under this category. In light of the growing awareness of environmental issues, civil society has become the initiator of creating so-called “local” NGOs, inspired by the success of “Friends of Nature” and similar organizations. In comparison to NGOs created with the involvement of government actors, which maintain close ties with the authorities and have more opportunities for policy engagement, local NGOs typically emerge from the initiatives of individuals and actively operate in rural areas or small towns. They are relatively independent and autonomous, usually not engaging too actively with the government at various levels (Wang, 2022).

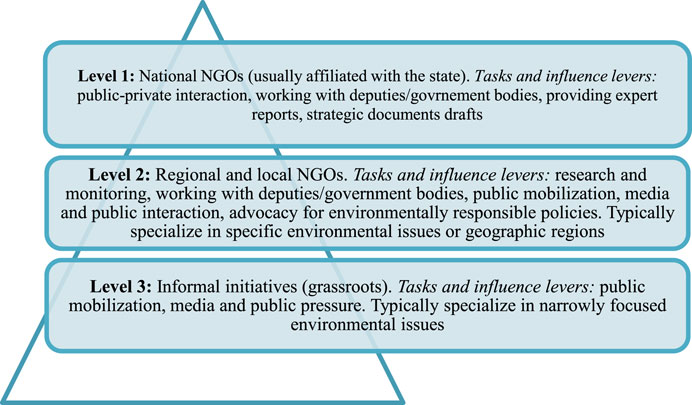

The conditional hierarchy of NGOs in China is organized into levels, ranging from national organizations to local groups and initiatives. Each level has its own characteristics and role in the overall system of environmental protection, and the interaction between these levels provides an integrated approach to solving environmental problems. There are four levels of hierarchy of Chinese environmental NGOs:

- nationwide NGOs are large organizations that often operate throughout the country. Many of them have close ties to government agencies and may receive funding and support from the government (example: China Environmental Protection Foundation (IUCN, 2020));

- provincial and regional NGOs. These organizations operate within one or more provinces. They can coordinate their activities with national NGOs and local government bodies (for example, environmental organizations operating within the same province, such as Green City of Haizhu District of Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province (IUCN, 2016a));

- local NGOs. These NGOs operate at the city, county or individual commune level. They often focus on solving specific local environmental problems (an example is small environmental groups working in specific areas, such as the Wuhu Ecology Center (China Development Brief, 2023));

- groups and local initiatives - these are the smallest and most informal associations of citizens that may not have official NGO status. They are involved in specific projects and initiatives at the community or local level (volunteer groups involved in cleaning rivers or greening local parks. For example, the Shenzhen Mangrove Wetlands Conservation Foundation initiatives (IUCN, 2016b)).

The interaction of environmental NGOs in China is carried out at the vertical and horizontal levels, differing in their structure, goals and methods of work. Vertical interaction involves a hierarchical distribution of roles and responsibilities. “Senior” NGOs, often with government support, manage and coordinate the activities of junior NGOs. Vertical NGOs develop large-scale strategies and programs, which are then implemented locally by “junior” NGOs (Figure 1).

Unlike the vertical interaction model, horizontal interaction involves cooperation between equal partners. This includes sharing information, resources and experiences between different NGOs. Horizontal NGOs are usually independent of government support and operate autonomously. They may focus on narrower or local issues that may receive less attention at the national level. An example of vertical interaction is the China Environmental Protection Foundation, which coordinates efforts with local NGOs to implement national environmental protection programs (IUCN, 2020). An example of horizontal collaboration would be NGOs such as Friends of Nature and Green Earth Volunteers collaborating to conduct campaigns to clean up rivers or protect forests, sharing resources and information (Wilson Center, 2022).

When discussing the rights of environmental NGOs in China as subjects of legislative initiatives, several key aspects need to be highlighted. In China, similar to many other countries, the activities of environmental NGOs are subject to certain restrictions, and their role in legislative initiatives is limited. The key aspects of rights and limitations for NGOs in China include:

• Registration and Legal Status: NGOs must be registered and have legal status in accordance with Chinese legislation. The registration process can be complex, and authorities may impose restrictions on the types of activities they can engage in.

• Restrictions on Political Activities: Strict control exists in China over the political activities of NGOs. They cannot engage in activities perceived as a threat to national security or political stability.

• Lobbying Restrictions: NGOs may face restrictions on lobbying and influencing the legislative process. They typically cannot directly impact legislation.

• Collaboration with Government Agencies: Some NGOs in China may collaborate with government agencies on specific projects and initiatives. However, such collaboration is likely to be under strict control, and organizations must comply with government formal requirements.

• Ecological Pilot Projects: NGOs may be invited by government authorities to participate in ecological pilot projects. In such cases, their recommendations and experiences may be considered in shaping environmental policies.

• Environmental Activism and Education: NGOs can engage in activism and education aimed at increasing environmental awareness in society. This can influence public opinion and exert pressure on authorities to enact specific legislative measures.

It is important to note that the Chinese government seeks to balance societal interests with political stability. Therefore, the influence of NGOs on the legislative process is limited and may depend on specific circumstances and the nature of their activities.

When discussing the aforementioned aspects, it is important to note that the majority of them primarily affect domestically established NGOs in China. Foreign NGOs may face a different situation. Over the past decade, due to various factors, there has been a noticeable decline in the number of foreign NGOs operating in the country (Zhong, 2021). Some organizations, including Handicap International - Humanity and Inclusion, have withdrawn from China, perceiving the country as no longer a developing nation, thus rendering their assistance less relevant. Additionally, the enactment of the Foreign NGO Law in 2016, which required foreign NGOs to secure official Chinese sponsors, created issues prompting the departure of several organizations (The China NGO Project, 2017). This phenomenon, encompassing both voluntary and compelled exits, as well as the reduction in activities of those remaining, underscores the evolving dynamics within China’s non-profit sector (Wang, 2023).

Nevertheless, the government is gradually accommodating private actors in the field of environmental conservation, expanding the general toolkit for protecting rights in the field of environmental protection through private law. An important step in this direction was the adoption of the revised China Environmental Protection Law by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in 2014 (the original law dates back to 1989). The law extended the powers of environmental NGOs representing public interests, allowing them to privately initiate legal actions against individuals and enterprises causing negative environmental impact. However, during the legislative process, the law underwent several amendments at the draft stage. The second set of amendments to the original version was generally considered favorable to the interests of environmental NGOs, particularly regarding contentious issues related to public interest litigation (Hsu and Teets, 2016). In this version, only the All-China Environmental Federation, an “NGO organized by the government,” was initially granted the right to conduct public interest litigation on environmental matters. Following negative feedback from environmentalists and NGOs, the third draft expanded this right to all registered environmental NGOs that had operated for 5 years and had a “good reputation.” However, the criteria for determining a “good reputation” remained unclear, leaving authorities with the discretion to decide which organizations met this criterion in practice (Corsetti, 2019).

Following further negative reactions, the provision regarding the reputation of organizations was removed in the final draft, replaced by a provision stipulating that such organizations should not engage in any unlawful activities. After the law with amendments came into effect, numerous environmental NGOs successfully utilized the new legislative mechanisms to initiate legal proceedings on nature conservation issues (Huang and Corsetti, 2019). Therefore, it can be observed how environmental organizations gained a channel for interaction with the authorities by providing feedback on draft amendments and how they effectively utilized this opportunity to secure broader rights to protect environmental interests in the court system (Corsetti, 2019).

Although China is playing an increasingly prominent role in global climate discussions, it is important to note that the interaction between both internal and external environmental actors with Chinese NGOs in the fight against climate change remains relatively limited. Data from China’s Annual Statistical Report on Civil Affairs for 2022 indicate that only a small fraction of registered NGOs in the country are actively involved in environmental and climate change issues. Furthermore, survey results included in the Chinese NGO Research Report on Climate Action for 2023 highlight the lack of attention to climate change issues among Chinese NGOs. This information deficit underscores the need to expand efforts to raise awareness among Chinese NGOs about their potential contributions to decarbonization initiatives (Wang, 2023).

In this context, it is crucial to note that detailed information about public discussions on specific legislative proposals involving NGOs is not published in Chinese official sources. Therefore, secondary sources such as news outlets and analytical reports become the primary informational resource regarding the contributions of NGOs to legislation or relevant policies. At the same time, NGO activities continue to be a significant tool for influencing the formation of environmental policies at the grassroots level, independent of the legislative process.

However, as has been repeatedly noted, the potential of Chinese NGOs can significantly exceed the existing scope of activities of local organizations and encompass a broader range of directions. Environmental-oriented NGOs can perform various functions, including conducting scientific research, advocating for ecological programs, and engaging in propaganda to protect nature, among others. Nevertheless, when examining specific environmental NGOs, such as “Green River” in China, only three primary functions stand out: protecting vulnerable ecological areas, providing informational education in the field of ecology, and advising governmental authorities (Kuhn, 2021).

Despite a relatively limited legal toolkit concerning legislative initiatives, Chinese NGOs have repeatedly demonstrated their effectiveness in lobbying for various environmental interests.

Thus, grassroots NGOs may have played a pivotal role in several cases related to the construction of hydraulic structures, exerting significant pressure on the government—forcing it to halt the construction of dams on the Nu River and securing the right to stop the hydropower station within the ancient Duzhuan irrigation system. Despite prolonged debates, in 2016, plans for dam construction on the Nu River were excluded from China’s 13th Five-Year Plan. Later, the hydropower station in the Duzhuan irrigation system was dismantled (International Rivers, 2018). Although it is formally asserted that the Nu River project was halted due to a change in governance principles by the central government and that the planning of the Duzhuan Yangluhu project was stopped due to objections from local authorities, one cannot deny that the efforts of grassroots NGOs in these matters had a significant impact on the Chinese government’s nature conservation policies (Wang, 2022).

As can be discerned, in recent years, the Chinese government has cautiously fostered the development of public initiatives in the realm of nature conservation. Notably, in this context, the expansion of rights for Chinese NGOs to protect rights through legal proceedings deserves attention. In the revised China Environmental Protection Law enacted in 2015, it is stipulated that NGOs should have the ability to initiate public interest litigation against violators. The government initiatives during those years, accompanying the revision of the fundamental environmental law, marked the emergence of the Environmental Public Interest Litigation (EPIL) system (Natural Resources Defense Council, 2016). The Civil Environmental Public Interest Litigation process developed in China over the past decade empowers environmental NGOs to challenge any “acts of pollution or damage to the environment that harm public interests” (Chu, 2023).

In July 2015, China’s national legislative body, under the guidance of the prosecutor, initiated a civil litigation process within the framework of EPIL in thirteen distinct provincial regions of the country. Following a 2-year legal experiment, in July 2017, the EPIL civil system under the prosecutor’s leadership was established nationwide (Ding and Xiao, 2021). EPIL in China allows qualified environmental NGOs to file lawsuits to protect public interests in the conservation of the environment and natural resources from pollution and ecological destruction. EPIL serves as a tool to safeguard environmental rights, not only addressing harm already inflicted on the environment but also preventing and mitigating future environmental damage. The objective of EPIL is to assist the broader public in asserting their complaints regarding environmental issues. This innovative environmental approach is employed to enable the public, volunteers, the private sector, and other stakeholders to participate and make decisions regarding the protection of the environment and natural resources from pollution and ecosystem destruction (Chu, 2023).

The expansion of judicial protection mechanisms in these areas is replenished with new examples, one of which is the case related to the construction of the “Blue Bay” - a recreational zone. Describing the situation it worth mentioning that the coastal wetlands at the mouth of the Linhong River near the Yellow Sea in Lianyungang Municipality are an important feeding and stopping place for migratory waterfowl. But in 2021, a construction project has put the mudflats at risk of erosion and destruction. They were to be turned into an artificial beach. In response, the environmental NGO Friends of Nature, previously mentioned in the text, filed a public interest lawsuit at the Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court against both the project developer and the organization responsible for the environmental impact assessment report. As a result of the legal proceedings, the defendant stated that it would reconsider the scheme and cancel the artificial beach plan (Dialogue Earth, 2023).

Concerning the strategies employed by NGOs to influence the government on environmental issues, as evidenced by practical experience, three primary approaches are typically utilized. Analytical arguments on this matter can be found in a range of contemporary studies on grassroots environmental initiatives in the country (Li et al., 2018; Wang, 2022; Zhai and Chang, 2019). Summarizing the conclusions of various researchers, the first strategy can be characterized as an approach in which local NGOs maximally leverage internal media resources, utilizing their social networks and mobilizing strong public support on various environmental conservation issues. The second strategy involves an aspiration to go beyond national jurisdiction, where NGOs actively take advantage of international forums and organizations to draw attention and involvement from the global community. The third strategy can be termed an integrated strategy of private-public interaction, where grassroots environmental NGOs actively engage with representatives of the people—deputies of the National People’s Congress and other actors in the legislative branch—by preparing reports and proposals for them.

In this context, policies played a leading role. The described approaches exerted pressure on the Chinese government from three different directions. The first approach was based on the strong influence of public opinion. The second implied international pressure and criticism from the global community. In the third case, political pressure was envisaged, stemming from objections by authorities and democratic parties that pressured the government from the perspective of democratic governance (Wang, 2022). Each of these strategies, in one form or another, demonstrated its effectiveness, indicating that they can continue to be employed in the future.

Thus, the following can be noted. Although environmental NGOs in China are not directly involved in the legislative process and do not have legislative initiative, their contribution to the formation of the legal framework for environmental regulation is expressed mainly in monitoring and analysis of environmental problems, advocacy and lobbying, as well as public education and clarifications provision in profile scope. It can be noted that the work in the field of lawmaking by Chinese environmental NGOs is also related to issues of expert support. One prominent example of how NGOs are actively engaging with legislators in China, providing expertise and data to develop and implement new environmental laws and regulations, is the work of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE). IPE is China’s leading organization dedicated to monitoring environmental pollution and promoting transparency between businesses and government agencies. An important part of their work was the development and implementation of the Environmental Information Disclosure Rules, a legislative initiative that requires large industrial enterprises to publish data on their emissions into the air and water bodies in real time (IPE Research Brief, 2022; XBRL, 2022).

4.4 Issues of implementation of the mechanisms of the Aarhus Convention in China

The adoption of the Aarhus Convention (UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters) was a giant step towards the development of international environmental law. Although the Aarhus Convention is regional in scope, its significance is nevertheless universal. It represents the most comprehensive development to date of Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration, which emphasizes the need for citizen participation in environmental issues and access to information held by public authorities (Stec et al., 2000). The Convention is essential for establishing the minimum procedural standards necessary to effectively guarantee this right. Negotiated by EU member states and reinforced by the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Directive 90/313/EEC, the Aarhus Convention sets out the scope of rights associated with requesting environmental information and the procedures that should be available to applicants. However, the Convention does not define procedural guarantees for these rights. This is an important feature of the Aarhus Convention: it is open to global accession and therefore must take into account the different political and legal cultures that exist in the UNECE region and beyond (Whittaker, 2017). Unlike the EU, China is not a party to the Aarhus Convention and is not obliged to apply the Convention approach to ensuring rights. However, China has generally accepted the principles of the Aarhus Convention guaranteeing the right of access to environmental information, and discussions are currently underway as to whether China should become a party to the Convention. Thus, whether states have acceded to the Convention or are using its provisions as an example, the overarching framework provided by the Aarhus Convention informs states around the world on how best to guarantee the right of access to environmental information (Whittaker, 2017).

Unlike European countries, China has not directly transposed the text of the Aarhus Convention, but the OGI and MOEI (Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Open Government Information, Measures on Open Environmental Information) regimes have adopted a structure similar to the Convention. The Chinese regime generally protects the same interests as those enumerated in the Convention (although less precisely defined) and includes, among others, the protection of state secrets, trade and commercial secrets, privacy, according to which government departments have the right not to disclose information if it jeopardizes state, public or economic security. Chinese government departments must also conduct a public interest test in certain cases, balancing the public interest in disclosing information with the public interest in withholding information. While not identical to the Aarhus Convention test, China’s public interest test also creates an additional procedural step in a government department’s decision on whether certain types of sensitive information should be disclosed (Dong, 2025). Thus, within the framework of the environmental policy of the PRC, the principles and instruments of the Aarhus Convention were adapted. However, under the conditions of the existing political system, the full potential of the Convention remains undiscovered, since the legislation of the PRC imposes significant restrictions on the legal mechanisms for the implementation of citizens’ rights to environmental information and justice. Existing legislative regulation gives departmental bodies ample opportunities to justify refusal to disclose environmental information, especially in cases where such disclosure could somehow compromise the ruling party. Thus, the CCP retains leverage to control the flow of information and prevent efforts by non-governmental actors to increase governance transparency, which is contrary to the goals of the Aarhus Convention. At the same time, some procedural mechanisms in the relevant legislation of the PRC have advantages over the Convention, for example, in terms of discretionary powers to confirm/refute the requested information (Dong, 2025).

5 Section 2. environmental NGOs of the People's Republic of China as a subject of environmental policy formation in the context of scientific discourse

Turning to the discussion of the role of NGOs in China’s legislative process and their evolution as a full-fledged actor in environmental policy, it is noteworthy that contemporary research generally diverges on the opinion that their role will significantly increase in the foreseeable future (Chen et al., 2020; Kuhn, 2021). Recent studies confirm the view that the activities of environmental NGOs in China play a crucial role not only in environmental issues but also in public health. The endeavours of environmental NGOs contribute to reducing child mortality and overall mortality rates. On the other hand, environmental NGOs have a favourable impact on life expectancy in China, demonstrating the auxiliary role of NGOs in enhancing life expectancy. It is anticipated that in the long term, the activities of environmental NGOs will exert a more significant positive influence on life expectancy. These findings suggest that promoting the activities of NGOs contributes to improving the health status of the Chinese population and advancing healthcare (Robinson et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). However, despite all potential “non-material dividends” from the activities of environmental NGOs, their role as legislative actors remains limited. Moreover, contemporary scholarly sources increasingly express the opinion that, overall, public participation in the development of environmental legislation can enhance the legitimacy of environmental policy, provide access to knowledge and information from various sources, create social consensus on decisions, and contribute to the compliance and enforcement of legislation (Li et al., 2018; Zhai and Chang, 2019; Zhu and Wu, 2017). In the practice of Western countries, there are a number of illustrative examples of how environmental NGOs have actually influenced legislative changes, becoming the initiators of reforms or exerting decisive pressure on the legislative process. In 2015, BUND (Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland) — the German branch of Friends of the Earth—initiated a broad campaign against the use of glyphosate. As part of the advocacy of this initiative, they conducted examinations, participated in parliamentary hearings, and the NGO mobilized public opinion through petitions and rallies. As a result, Germany announced a phased phase-out of glyphosate by 2024, partly due to pressure from NGO (BUND, 2015; Reuters, 2024; Wandel, 2023). Another example is the involvement of the French Générations Futures in advocacy for pesticide restrictions in the country. As part of the initiatives undertaken, the organization published a series of scientifically based investigations on pesticide residues in products, initiated lawsuits against manufacturing companies, and lobbied for bills to restrict the use of hazardous substances. The government considered their recommendations by adopting the EGAlim Law (2018 - La loi du 30 octobre 2018 pour l'équilibre des relations commerciales dans le secteur agricole et alimentaire et une alimentation saine, durable et accessible à tous), which limits the use of pesticides near residential areas and strengthens controls (Örmen, 2024). The third example is the Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act (The Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act) adopted in the United States in 2016. It was developed in close cooperation with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). The document included a number of the organization’s regulatory developments (Varner, 2024). These examples can be supplemented by a number of others (including numerous initiatives by organizations such as Greenpeace, ClientEarth), indicating the growing role of NGOs in the formation of environmental policy and law-making.

In China, public participation in the development of environmental legislation is particularly crucial, as current legislative bodies require more technical assistance for the formalization of environmental policy, representation of environmental interests in the legislative body is relatively weak, and public involvement in the implementation of environmental legislation needs better institutional support. Direct and active public participation can contribute to advancing environmental interests both in the legislative process and during its implementation (Zhu and Wu, 2017).

It should be noted that in recent years, there has been an increasing contribution of civil society to the development of environmental NGOs. Additionally, the status of these organizations in OCS-related issues, such as the implementation of environmental policies, planning, and internal management in the field of OCS, is gradually strengthening. At the same time, in comparison with similar organizations abroad, Chinese NGOs face a range of specific problems: their numbers are relatively small, and the scale of their activities and influence is limited. They encounter financial difficulties, and their interaction with government authorities often proves ineffective. Furthermore, the lack of international connections often hinders their operational scope and reduces opportunities for exchanging experiences (Kuhn, 2019).

In earlier studies, it was noted that despite the legal establishment of the public’s right to participate in environmental supervision, there persists ambiguity and insufficient detail in laws and regulations that would specify specific methods, conditions, and participation requirements, as well as individual procedural nuances. This creates difficulties for citizens when they encounter specific environmental issues, as it is challenging for them to determine the proper, sequential, and lawful course of action) (Ning, 2015; Wang et al., 2013). In this context, it becomes evident that mechanisms for public participation in OCS matters and, specifically, legislative initiatives require further refinement. Guided by the revised OCS Law and the EIA Law (Environmental Impact Assessment) of the People’s Republic of China, as well as other existing environmental protection acts, efforts should continue to expand the regulatory framework concerning nature conservation and environmental safety. The primary environmental protection law in China includes general provisions for involving the public in this process. In legal terms, this law establishes principles, rights, and general norms of public participation, as well as defines legal responsibility for violations in this area. Thus, corresponding legislation is required to specify the details of public participation. Consequently, the formation of a comprehensive public participation system in environmental protection, based on the Environmental Protection Law and the People’s Republic of China Environmental Impact Assessment Law, requires supplementation with other relevant legal acts. Ultimately, these acts should establish an integrated system of public participation in environmental protection. It is crucial that, in the context of developing these regulatory mechanisms, NGOs are assigned a role not only as objects but also as subjects. In other words, NGOs should be more broadly involved in the processes of developing regulatory mechanisms that concern the specifics of their activities.

This perspective finds confirmation in practical examples. Taking into account the aforementioned precedents related to the construction of hydraulic structures within the Dujiangyan irrigation system and the Nu River basin, it should be noted that in these cases, Chinese NGOs played a possibly pivotal role. Without the support of local NGOs, the public would not have paid attention to these issues; therefore, there would not have been strong public objections, and the government would not have considered changing its decision (Matsuzawa, 2020). Although, as noted, the role of governmental actors was also present. In modern research, a well-founded opinion is expressed that without decisive support from within the government, NGOs could not have succeeded in changing governmental decisions on their own. The impact exerted by grassroots NGOs on environmental decisions at the political and legal levels is an external auxiliary factor. In this context, the function of these organizations is to activate and accelerate changes in the decisions made. Their influence is recognized as external, secondary, and dependent. In the context of making environmental decisions in China, the key and defining factor is precisely political will. This internal factor determines the final direction of environmental policy (Wang, 2022).

In the context of addressing these issues, it can be observed that China’s initiatives to combat climate change necessitate the strengthening of public-private partnerships, the enhancement of collaboration potential to achieve common goals, the reinforcement of coordination among NGOs at the horizontal level, public support, and adequate financing. Environmental NGOs can play a crucial role in supporting civil society participation and aiding local communities in preserving their natural heritage. This assistance may involve habitat restoration, wildlife protection, and sustainable resource management. Despite the difficult political environment, NGOs in the PRC have repeatedly achieved success in promoting environmental initiatives. Examples include the cases of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCGDF) to protect the Chinese Tibetan antelope (chiru) or the Blue Ribbon Ocean Conservation Association to combat marine pollution. In 2019, thanks to the efforts of the CBCGDF and other NGOs, the government introduced additional measures to protect the chiru, including the construction of tunnels and bridges for the safe movement of antelope (Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, 2019). In 2021, China adopted new regulations to protect the marine environment, including measures to reduce plastic waste and improve wastewater treatment. The active work of NGOs such as Blue Ribbon played an important role in these changes (Osaka Blue Ocean Vision, 2024).

Chinese civil society encompasses numerous local NGOs dedicated to environmental conservation, and environmental NGOs can provide decisive support to them, including sharing best practices and offering expert technical assistance. By enhancing the potential of local organizations, NGOs enable them to effectively address environmental issues at the grassroots level. Efforts to build capacity, such as training programs, seminars, and technical support, are designed to contribute to this objective (Wang, 2023).

Regarding the implementation of the Aarhus mechanisms, it can indeed be argued that the difference between public (governmental) and private participation in these issues is hardly obvious. Countering this is the incredible scale, complexity and urgency of the pressing environmental challenges facing China, which can no longer be solved solely by a top-down approach. This has led to the idea that a more hybrid approach could be developed through the gradual implementation of an “Ecological Civilization”. This could combine the strengths of the long-term planning possible within the Chinese governance system with the gradual strengthening of Aarhus approaches, which can build on the changes observed in this paper. Some references to the current role and influence of specific international NGOs, such as International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which have used expertise and science to engage inclusively with governments, may be illustrative. Likewise, institutions such as the Research Institute of Environmental Law of Wuhan University can perform functions similar to NGOs in other countries. Future strategies may include increasing the level of education, information and participation of NGOs and communities through long-term engagement through such institutions as well as various levels of government. Community participation in long-term monitoring of water pollution and other types of environmental degradation can be gradually integrated into school and university curricula and improve the dissemination of information and basic environmental data, the collection and analysis of which is beyond the resources of governments. Pace University’s River Keepers program (Chambers, 2009) is an excellent example in the US, although it emphasizes litigation, which in China may not be feasible in the near future. These are small steps, but they could be a way to exploit politically weak NGOs using approaches that limit conflict and have a degree of legitimacy in the Chinese legal and political system.

6 Resume: institutional specifics and the role of NGOs in greening the legislation of the PRC

In conclusion, several key aspects regarding the current role of NGOs in environmental policy matters in China can be highlighted from the perspective of their legal status and authorities. In China, NGOs play a significant yet limited role in shaping environmental policy. The Chinese government exercises considerable control over the activities of NGOs, and they are required to adhere to strict rules and regulations, partially diminishing their potential as legal initiative proponents. Nevertheless, over time and with certain policy changes, NGOs have started to influence the environmental sphere in some aspects. At this stage, their activities encompass directions such as:

- Research and Monitoring: Some environmental NGOs in China conduct research and monitor the state of the environment. The results of these studies may be presented in reports and analytical materials, capturing the attention of the public and officials, and thereby influencing the formulation of environmental policy;